Abstract

Sexual health concerns are one of the most common late effects facing hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) survivors. The current study tested whether self-reported depression and anxiety symptoms before transplant were associated with embedded items assessing two specific areas of sexual health—sexual interest and sexual satisfaction—one year post-HSCT. Of the 158 study participants, 41% were diagnosed with a plasma cell disorder (n = 60) and most received autologous transplantation (n = 128; 81%). At post-HSCT, 21% of participants reported they were not at all satisfied with their sex life, and 22% were not at all interested in sex. Greater pre-HSCT depressive symptomology was significantly predictive of lower sexual interest (β = −.27, p < .001) and satisfaction (β = −.39, p < .001) at post-HSCT. Similarly, greater pre-HSCT trait anxiety was significantly predictive of lower sexual interest (β = −.19, p = .02) whereas higher levels of state and trait anxiety were both predictive of lower satisfaction (β = −.22, p = .02 and β = −.29, p = .001, respectively). Participant sex significantly moderated the relationship between state anxiety and sexual satisfaction (b = −.05, t = −2.03, p = .04). Additional research examining the factors that contribute to sexual health post-HCST is needed to inform and implement clinical interventions to address these commonly overlooked survivorship concerns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HCST) is a well-established treatment for malignant and non-malignant hematologic conditions, with over 23,000 procedures performed in the United States in 2018 alone (Auner et al., 2015; D'Souza et al., 2020). Unfortunately, psychological distress remains a common experience for many individuals who have had or are preparing to undergo HCST (Amonoo et al., 2019). For example, depressive symptoms are highly prevalent prior to HSCT and remain a common experience for up to two years after transplantation (El‐Jawahri et al., 2017; Loberiza et al., 2002; Mosher et al., 2009). Additionally, patients with depression have reported poorer quality of life and more adverse outcomes following transplant (Costanzo et al., 2013; Kelly et al., 2021; Loberiza et al., 2002). Another common reaction is heightened anxiety in anticipation of HSCT, as well as concerns related to fear of cancer recurrence or relapse (Amonoo et al., 2019; Prieto et al., 2005). In a review by Mosher and colleagues, 5% to 40% of patients experienced elevated levels of anxiety and/or depressive symptoms before, during, and after HSCT (Mosher et al., 2009), further illuminating the high distress rates within HSCT populations.

In addition to mood and anxiety concerns, changes in sexual function are common clinical complaints for patients who have received HSCT. In fact, sexual difficulties are one of the most commonly reported late effects of HSCT (Kelly et al., 2021). A wide range of sexual health changes and concerns are often present and can persist for years following HSCT. These include decreased sexual interest (aka libido) and sexual satisfaction, premature menopause with resulting disruptions in sexual function, vulvovaginal changes, sexual/genital pain, and erectile and orgasmic/ejaculatory difficulties (Li et al., 2015; McKenna et al., 2019; Phelan et al., 2022; Thygesen et al., 2012; Tierney, 2004; Yi & Syrjala, 2009).

Thygesen and colleagues, in 2012, provided a comprehensive review of the literature on sexual health in HSCT patient populations (Thygesen et al., 2012). In assessing a 16-year period, they found only 14 studies that examined sexual health in HSCT to some degree. Among the papers reviewed, sexual concerns were repeatedly identified and a participant sex-by-time interaction observed in which the sexual health problems of female patients increased over time post-HSCT whereas male participants’ concerns tended to remain more stable. This is in line with the known progressive nature of vulvovaginal conditions associated with HSCT (e.g., genitourinary syndrome of menopause and related sexual pain) which tend to worsen when left untreated (Crean-Tate et al., 2020; Sopfe et al., 2021). While some survivors experienced a partial recovery in sexual health within the first 2 years post-transplant, many were likely to experience just-as-bad or worsened sexual health challenges up to 10 years post-transplant (the furthest outcome measured in any of the reviewed studies).

In an earlier longitudinal study exploring sexual function at pre-transplant and up to 3 years post-transplant, Humphreys et al. (2007) found significantly decreased sexual activity at 1- and 3-years post-transplant. For those who were sexually active prior to transplant, both men and womenFootnote 1 reported decreased sexual interest. One-year following transplant, men reported increased difficulty with erections (50%), but less sexual interest concerns (33%). Women reported vulvovaginal dryness (78%), difficulty with orgasm (72%), and sexual pain (61%), as well as decreased sexual interest (72%), body image concerns (72%), and feeling less attractive (78%) (Humphreys et al., 2007). Notably, both men and women reported that their sexual health concerns had either remained constant or improved somewhat 3 years after transplant. Similarly, in a prospective study examining sexual health for 5 years post-HSCT, men’s sexual function demonstrated improvement by year 2, whereas women’s sexual function did not show improvements by year 5 (Syrjala et al., 2008). Notably, all transplant survivors were below controls with regard to sexual activity and function (Syrjala et al., 2008).

Psychological distress, in particular, is known to impact sexual functioning and satisfaction (Humphreys et al., 2007). In addition to outlining common sexual health concerns in the transplant population, the study by Humphreys et al. (2007) provided a critical contribution to the transplant literature regarding sexual health and psychological distress. Specifically, depression was found to be a significant predictor of decreased sexual functioning at 3-years post-transplant. The researchers argue for the treatment of depression as an interventional target for improving sexual health in transplant patients. Anxiety was not assessed in the Humphreys et al. (2007) study, however, the broader sexual health literature links both depression and anxiety symptoms to sexual health, suggesting that each may play a role for transplant survivors. This has yet to be formally tested in the transplant population and, as such, the current study included assessment of both depression and anxiety symptomology.

Improved understanding of the relationship between psychological distress and sexual health is essential given: (1) the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Blood and Marrow Transplant Late Effects Initiative that cited sexual health and dysfunction as a primary concern in need of intervention (Bevans et al., 2017), (2) sexual health being highlighted as 1 of 6 research priorities by HSCT patients, caregivers, and researchers (Burns et al., 2018), and (3) the American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendation to more specifically measure both depression and anxiety (Smith et al., 2018). The current study aimed to leverage existing data with embedded sexual health items to explore the prospective association between pre-HSCT distress and two commonly noted sexual health concerns—interest and satisfaction. We also aimed to determine whether demographic and disease characteristics significantly moderate the relationship between distress and sexual interest or satisfaction. It was hypothesized that greater pre-HSCT distress would be predictive of lower sexual interest and sexual satisfaction at one-year post transplantation.

Method

Eligibility Criteria

Patients who received HSCT at Mayo Clinic, provided informed consent, and completed both pre- and post-transplant surveys were eligible to participate in the current study. Study criteria included: (a) being at least 18 years old, (b) absence of a current psychotic or neurological disorder that may have precluded participation, as determined by pre-transplant medical and psychological evaluation, (c) fluency in English, and (d) provision of written informed consent to participate.

Study Procedures

As part of clinical care, all HSCT candidates underwent a pre-transplant psychological evaluation in accordance with Institutional guidelines. This included a semi-structured interview and questionnaire-based assessment (e.g., BDI, STAI described below). These clinical measures were abstracted to obtain an assessment of pre-transplant psychological distress for the current study. Additionally, all HSCT candidates were invited to participate in a study of health behaviors in association with transplant outcomes 1-year post-HSCT (e.g., sexual interest and satisfaction item scores from the FACT-BMT, described below). The current study is a secondary analysis of this outcome data, focused on embedded sexual health questions.

Measures

Sexual Interest & Sexual Satisfaction

Participants’ satisfaction with sex (“I am satisfied with my sex life”), as well as interest in sex (“I am interested in sex”) were obtained from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—Bone Marrow Transplantation (FACT-BMT) questionnaire post-HSCT (McQuellon et al., 1997). This questionnaire broadly assesses four domains of health-related quality of life in patients undergoing bone marrow transplant, using 5-point Likert scale item scores (0 = not at all, 4 = very much; item score range 0–4) that sum to a total score with established reliability and validity in BMT populations.

Depressed Mood Assessment

Depressed mood was measured via the Beck Depression Inventory-II (Beck et al., 1996) at pre-HSCT (21 items, 0–3 Likert response scale). In a variety of populations, BDI-II has demonstrated excellent internal consistency and good test–retest reliability (Wang & Gorenstein, 2013).

Anxious Mood Assessment

Pre-HSCT anxious mood was measured via the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; 40 items, 0–3 Likert response scale; Spielberger, 1983; Spielberger & Reheiser, 2003). This measure has two subscales: state anxiety, which measures subjective feelings of current anxiety and arousal, and trait anxiety, which measures the likelihood of experiencing anxiety during a stressful event.

Disease and Treatment Data

Disease and transplant-related treatment data, including transplant type (i.e., allogeneic, autologous) and performance status (measured via ECOG) (Oken et al., 1982) were obtained from the institution’s Transplant Center.

Statistical Plan

Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS for Windows, Version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). All participant answers were included for analyses; no listwise deletion was conducted for missing data. Primary analyses included linear regressions of pre-HCST distress (BDI, STAI) predicting FACT-BMT sexual interest and satisfaction item scores 1 year post-HCST. Secondary analyses tested for moderation effects by sociodemographic and disease variables known to impact sexual health (e.g., performance status) (Syrjala et al., 2021) utilizing PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2017).

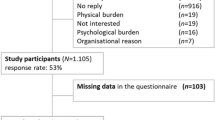

Results

Individuals who completed at least one baseline psychological distress measure (i.e., BDI-II, STAI) and at least one sexual health question at post-HSCT (i.e., sexual satisfaction, sexual interest) were included in analyses (n = 158). Full demographic and disease characteristic data are included in Table 1. Of the 158 participants, 41% were diagnosed with a plasma cell disorder and most received autologous transplantation. Participants primarily were male and identified as non-Hispanic White, married or partnered, and between 41 and 64 years of age. Approximately half of the participants were employed.

Pre- and post-transplant questionnaire responses including sexual interest and satisfaction data are included in Table 2. Overall, 21% of participants indicated they were not at all satisfied with their sex life post-HSCT and 22% were not at all interested in sex.

Primary Analyses

Depressive Symptoms

Pre-HSCT depressive symptomology was significantly associated with sexual interest and sexual satisfaction over time. Specifically, higher depression scores at pre-HSCT, as measured by the BDI-II, predicted lower rates of sexual interest (n = 154, β = −0.27, p < 0.001) and sexual satisfaction (n = 119, β = −0.39, p < 0.001) one-year post-HSCT.

Anxious Symptoms

Pre-transplant STAI scores were associated with sexual interest and satisfaction such that greater levels of both trait and state anxiety predicted poorer sexual health. That is, higher levels of trait anxiety significantly predicted lower interest in sex (n = 154, β = −0.19, p = 0.02) and lower sexual satisfaction (n = 119, β = −0.29, p = 0.001). State anxiety did not significantly predict sexual interest (n = 156, β = −0.11, p = 0.18), but did significantly predict sexual satisfaction (n = 121, β = −0.22, p = 0.02) such that higher levels of state anxiety indicated lower levels of satisfaction with one’s sex life.

Secondary Analyses

Additional analysis demonstrated a significant negative moderating effect of participant sex on the relationship between state anxiety and sexual satisfaction (b = −0.05, t = −2.03, p = 0.04), such that male transplant patients with greater state anxiety reported the lowest levels of sexual satisfaction (see Fig. 1). No additional moderating effects were found (i.e., age, relationship status, change in relationship status within the past 12 months, transplant type, and performance status) between state anxiety and sexual satisfaction or sexual interest. Similarly, there were no significant moderating effects of any of the demographic and disease variables on trait anxiety nor depressive symptoms.

Discussion

Results confirm that psychological distress is a key predictor of sexual interest and sexual satisfaction for transplant patients. Notably, while the associated literature to date focuses on depression, we found that anxiety was also predictive of sexual interest and satisfaction up to 1-year post-HSCT. Demographic, disease, and performance status variables did not moderate most of these distress-sexual health associations. The association of distress to sexual interest and sexual satisfaction persists for HSCT patients above and beyond sociodemographic factors traditionally related to these sexual health variables in the initial year post-transplantation. One exception was identified in which participant sex significantly moderated the association between state (but not trait) anxiety and sexual satisfaction such that male transplant patients with greater state anxiety reported the lowest levels of sexual satisfaction in the current sample.

The association between general psychological distress and sexual health has been extensively documented across numerous populations (e.g., Carcedo et al., 2020; Coyle et al., 2019; Field et al., 2016; Hartmann, 2007; Kalmbach et al., 2015), is replicated by the current study, and uniquely links anxiety to both sexual interest and satisfaction in a post-HSCT sample. Given the known bidirectional relationship between mental health and sexual health variables, interventions focused on reducing depression and anxiety symptoms may very well be positively impactful for the sexual health of some HSCT patients. There is strong evidence of the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions, in particular, for reducing both mental and sexual health concerns. This suggests common underlying targets with regard to improving attention and emotion regulation, interoceptive awareness, cognitive flexibility, and perception of self that require further investigation—especially in HSCT populations (Bossio et al., 2019; Gorman et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2020).

Research has repeatedly demonstrated that sexual problems often do not improve over time without intervention; indeed, they are very likely to worsen, or at least remain consistently poor (Gilbert et al., 2016; Humphreys et al., 2007; Li et al., 2015; Molassiotis, 1997; Nørskov et al., 2015; Perz et al., 2014; Schover et al., 2014; Smith et al., 2022; Thygesen et al., 2012; Ussher et al., 2015; Utz & Jagasia, 2013; Varela et al., 2013). Distress screening measures (e.g., BDI and STAI) are required elements of comprehensive cancer care (American College of Surgeons, 2020; Lazenby et al., 2015) and thus have clinical utility in identifying patients at risk for lower sexual satisfaction and interest, up to 1-year post-HSCT in the current study. Additionally, sexual health concerns are consistently linked to lower overall quality of life ratings, circumventing optimal survivorship outcomes. As early as 1997, Molassiotis noted that HSCT patients' sexual health concerns persisted for as long as was measured—in this case, ≥ 6 years post-transplant. In contrast, other significant psychosocial concerns (e.g., social adjustment, grieving, life re-evaluation, feelings of despair and loss of control, occupational adjustments) presented and largely resolved within the same measurement period (Molassiotis, 1997). A decade later, Humphreys and colleagues published similar findings (Humphreys et al., 2007). At their farthest post-transplant measurement point (3 years), both men and women reported significant and persistent sexual problems that had continuously impacted their overall quality of life. Concerns ranged from physical functioning difficulties (e.g., erection, orgasm, and ejaculation problems) to those more psychosocial or relational in nature (e.g., perceived attractiveness/body image, sexual interest/libido). As in the current study, such sexual health concerns were positively associated with baseline levels of depression. Critically, Humphreys and colleagues highlighted that half of patients at all time points in their study reported no discussions with any provider regarding their sexual health (Humphreys et al., 2007).

Application and Future Directions

Ensuring patients’ sexual and psychological health needs are addressed is critically important and this appears to be especially true for HSCT populations. Results of the current study highlight both depression and anxiety as predictive of sexual health concerns up to 1-year post-HSCT, emphasizing the importance of not only treating distress, but assessing possible sexual health concerns. Clinicians with limited comfort or knowledge around the topic of sexual health are strongly encouraged to consider additional training opportunitiesFootnote 2 in this area to best serve the needs of transplant patients.

More intentional measurement of sexual problems in HSCT patients is recommended to better understand the reasons for subjective reports of poor sexual health. This includes, for example, parsing out the various components of sexual health-related concerns (e.g., physiological, psychological, relational, spiritual) and measuring each individually to establish where, exactly, the problems lie. Researchers and clinical scientists should also consider longitudinal measurement of sexual health concerns, particularly in relation to symptom onset of illnesses most typically treated via HSCT as well as treatment milestones. Collecting such data with a matched control group would be of particular utility in furthering scientific understanding.

Limitations

While use of secondary data allows for the study of sexual health variables embedded within a larger study (i.e., minimizing stigma and optimizing participation), it also limits the complexity of available sexual health data. Though self-assessment of sexual interest and satisfaction represent important outcomes, sexual health can be measured in myriad ways beyond these two factors (e.g., clinical diagnostics, sexual distress levels, physical sexual function). Such forms of data collection, as well as some potentially relevant clinical factors (e.g., menopause status), were unavailable for this study, precluding a more robust and nuanced view of HSCT patients’ experiences with sexual health. Future studies should include pre- and post-HSCT measures of depression, anxiety, and sexual health constructs. Finally, while disease and overall performance status were not associated with sexual interest and satisfaction,

several important treatment-related variables could not be examined in the present study given the absence of resources required to access extensive clinical data, including medications, more detailed treatment regimens, and complications (e.g., GVHD), which can have direct effects on sexual functioning and sexual health-related variables. Unfortunately, the impact of such factors could not be measured within the current study, limiting our overall view of participants’ sexual health.

Conclusion

The current study highlights the association between pre-HSCT patient psychological distress and sexual concerns up to 1-year post-HSCT, including anxiety as a risk factor for lower sexual interest and satisfaction. To positively impact transplant care and survivorship, healthcare providers are duty-bound to discuss and normalize the potential sexual health impacts of HSCT as a common and treatable problem in the context of depression and anxiety. Existing protocols for addressing depression and anxiety within HSCT patient care should be updated to include assessment of sexual health concerns.

Data Availability

Data may be available upon request to the corresponding author.

Notes

Of note, these are presumed to be cisgender samples. Cisgender men are individuals who were assigned male sex at birth and identify as men, whereas cisgender women were assigned female sex at birth and identify their gender as women. We have elected to retain language used by the original publications being cited, while recognizing that many such studies do not actually assess gender, rather infer gender based on sex assigned at birth. The inappropriate conflation of anatomical sex and gender is a major limitation of the existing literature and state of the science. Johnson and colleagues provide an excellent discussion of this longstanding barrier in health-focused research.17 (Johnson, Greaves, & Repta, 2009).

Relevant professional organizations include: the American Association of Sexuality Educators, Counselors and Therapists (AASECT), The International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM), The International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health (ISSWSH), and The Scientific Network on Female Sexual Health and Cancer.

References

American College of Surgeons. (2020). Optimal Resources for Cancer Care: 2020 Standards. In. Chicago, IL.

Amonoo, H. L., Massey, C. N., Freedman, M. E., El-Jawahri, A., Vitagliano, H. L., Pirl, W. F., & Huffman, J. C. (2019). Psychological considerations in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychosomatics, 60(4), 331–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2019.02.004

Auner, H., Szydlo, R., Hoek, J., Goldschmidt, H., Stoppa, A., Morgan, G., & Russell, N. (2015). Trends in autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple myeloma in Europe: Increased use and improved outcomes in elderly patients in recent years. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 50(2), 209–215.

Beck, A., Steer, R., & Brown, G. (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory, (BDI-II) San Antonio. The Psychological Association.

Bevans, M., El-Jawahri, A., Tierney, D. K., Wiener, L., Wood, W. A., Hoodin, F., & Syrjala, K. L. (2017). National Institutes of health hematopoietic cell transplantation late effects initiative: The patient-centered outcomes working group report. Biology of Blood Marrow Transplantation, 23(4), 538–551. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.09.011

Bossio, J. A., Miller, F., O’Loughlin, J. I., & Brotto, L. A. (2019). Sexual health recovery for prostate cancer survivors: The proposed role of acceptance and mindfulness-based interventions. Sexual Medicine Reviews, 7(4), 627–635.

Burns, L. J., Abbetti, B., Arnold, S. D., Bender, J., Doughtie, S., El-Jawahiri, A., & Denzen, E. M. (2018). Engaging patients in setting a patient-centered outcomes research agenda in hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biology of Blood Marrow Transplantation, 24(6), 1111–1118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.01.029

Carcedo, R. J., Fernández-Rouco, N., Fernández-Fuertes, A. A., & Martínez-Álvarez, J. L. (2020). Association between sexual satisfaction and depression and anxiety in adolescents and young adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 841.

Costanzo, E. S., Juckett, M. B., & Coe, C. L. (2013). Biobehavioral influences on recovery following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Brain, Behavior and Immunity, 30(Suppl), S68-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2012.07.005

Coyle, R. M., Lampe, F. C., Miltz, A. R., Sewell, J., Anderson, J., Apea, V., & Lascar, M. (2019). Associations of depression and anxiety symptoms with sexual behaviour in women and heterosexual men attending sexual health clinics: A cross-sectional study. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 95(4), 254–261.

Crean-Tate, K. K., Faubion, S. S., Pederson, H. J., Vencill, J. A., & Batur, P. (2020). Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in female cancer patients: A focus on vaginal hormonal therapy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 222(2), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.08.043

D’Souza, A., Fretham, C., Lee, S. J., Arora, M., Brunner, J., Chhabra, S., & Hari, P. (2020). Current use of and trends in hematopoietic cell transplantation in the United States. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 26(8), e177–e182.

El-Jawahri, A., Chen, Y. B., Brazauskas, R., He, N., Lee, S. J., Knight, J. M., & Wirk, B. M. (2017). Impact of pre-transplant depression on outcomes of allogeneic and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer, 123(10), 1828–1838.

Field, N., Prah, P., Mercer, C. H., Rait, G., King, M., Cassell, J. A., & Clifton, S. (2016). Are depression and poor sexual health neglected comorbidities? Evidence from a population sample. BMJ Open, 6(3), e010521.

Gilbert, E., Perz, J., & Ussher, J. M. (2016). Talking about sex with health professionals: The experience of people with cancer and their partners. European Journal of Cancer Care, 25(2), 280–293.

Gorman, J. R., Drizin, J. H., Al-Ghadban, F. A., & Rendle, K. A. (2021). Adaptation and feasibility of a multimodal mindfulness-based intervention to promote sexual health in cancer survivorship. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 11(10), 1885–1895.

Hartmann, U. (2007). Depression and sexual dysfunction. Journal of Men’s Health and Gender, 4(1), 18–25.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

Humphreys, C., Tallman, B., Altmaier, E., & Barnette, V. (2007). Sexual functioning in patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation: A longitudinal study. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 39(8), 491–496.

Johnson, J. L., Greaves, L., & Repta, R. (2009). Better science with sex and gender: Facilitating the use of a sex and gender-based analysis in health research. International Journal for Equity in Health, 8, 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-8-14

Kalmbach, D. A., Pillai, V., Kingsberg, S. A., & Ciesla, J. A. (2015). The transaction between depression and anxiety symptoms and sexual functioning: A prospective study of premenopausal, healthy women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1635–1649.

Kelly, D. L., Syrjala, K., Taylor, M., Rentscher, K. E., Hashmi, S., Wood, W. A., & Burns, L. J. (2021). Biobehavioral research and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: Expert review from the biobehavioral research special interest group of the American society for transplantation and cellular therapy. Transplantation and cellular therapy, 27(9), 747–757.

Lazenby, M., Ercolano, E., Grant, M., Holland, J. C., Jacobsen, P. B., & McCorkle, R. (2015). Supporting commission on cancer-mandated psychosocial distress screening with implementation strategies. Journal of Oncology Practice/ American Society of Clinical Oncology, 11(3), e413-420. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2014.002816

Li, Z., Mewawalla, P., Stratton, P., Yong, A. S., Shaw, B. E., Hashmi, S., & Savani, B. N. (2015). Sexual health in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Cancer, 121(23), 4124–4131.

Loberiza, F. R., Jr., Rizzo, J. D., Bredeson, C. N., Antin, J. H., Horowitz, M. M., Weeks, J. C., & Lee, S. J. (2002). Association of depressive syndrome and early deaths among patients after stem-cell transplantation for malignant diseases. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 20(8), 2118–2126. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2002.08.757

McQuellon, R. P., Russell, G. B., Cella, D. F., Craven, B. L., Brady, M., Bonomi, A., & Hurd, D. D. (1997). Quality of life measurement in bone marrow transplantation: Development of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-bone marrow transplant (FACT-BMT) scale. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 19(4), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1700672

Molassiotis, A. (1997). Psychosocial transitions in the long-term survivors of bone marrow transplantation. European Journal of Cancer Care, 6(2), 100–107.

Mosher, C. E., Redd, W. H., Rini, C. M., Burkhalter, J. E., & DuHamel, K. N. (2009). Physical, psychological, and social sequelae following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: A review of the literature. Psycho-Oncology, 18(2), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1399

Nørskov, K. H., Schmidt, M., & Jarden, M. (2015). Patients’ experience of sexuality 1-year after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 19(4), 419–426.

Oken, M. M., Creech, R. H., Tormey, D. C., Horton, J., Davis, T. E., McFadden, E. T., & Carbone, P. P. (1982). Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern cooperative oncology group. American Journal of Clinical Oncology, 5(6), 649–655.

Perz, J., Ussher, J. M., & Gilbert, E. (2014). Feeling well and talking about sex: Psycho-social predictors of sexual functioning after cancer. BMC Cancer, 14(1), 1–19.

Phelan, R., Im, A., Hunter, R. L., Inamoto, Y., Lupo-Stanghellini, M. T., Rovo, A., & Murthy, H. S. (2022). Male-specific late effects in adult hematopoietic cell transplantation recipients: A systematic review from the late effects and quality of life working committee of the center for international blood and marrow transplant research and transplant complications working party of the European society of blood and marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 57, 1150–1163.

Prieto, J. M., Atala, J., Blanch, J., Carreras, E., Rovira, M., Cirera, E., & Gastó, C. (2005). Patient-rated emotional and physical functioning among hematologic cancer patients during hospitalization for stem-cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 35(3), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1704788

Schover, L. R., van der Kaaij, M., van Dorst, E., Creutzberg, C., Huyghe, E., & Kiserud, C. E. (2014). Sexual dysfunction and infertility as late effects of cancer treatment. European Journal of Cancer Supplements, 12(1), 41–53.

Shen, H., Chen, M., & Cui, D. (2020). Biological mechanism study of meditation and its application in mental disorders. General Psychiatry, 33(4), e100214.

Smith, S. K., Loscalzo, M., Mayer, C., & Rosenstein, D. L. (2018). Best practices in oncology distress management: Beyond the screen. American Society of Clinical Oncology Educational Book, 38, 813–821. https://doi.org/10.1200/edbk_201307

Smith, T., Kingsberg, S. A., & Faubion, S. (2022). Sexual dysfunction in female cancer survivors: Addressing the problems and the remedies. Maturitas, 165, 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2022.07.010

Sopfe, J., Pettigrew, J., Afghahi, A., Appiah, L. C., & Coons, H. L. (2021). Interventions to improve sexual health in women living with and surviving cancer: Review and recommendations. Cancers, 13(13), 3153.

Spielberger, C. D. (1983). State-trait anxiety inventory for adults.

Spielberger, C. D., & Reheiser, E. C. (2003). Measuring anxiety, anger, depression, and curiosity as emotional states and personality traits with the STAI. Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, 2, 70.

Syrjala, K. L., Kurland, B. F., Abrams, J. R., Sanders, J. E., & Heiman, J. R. (2008). Sexual function changes during the 5 years after high-dose treatment and hematopoietic cell transplantation for malignancy, with case-matched controls at 5 years. Blood, the Journal of the American Society of Hematology, 111(3), 989–996.

Syrjala, K. L., Schoemans, H., Yi, J. C., Langer, S. L., Mukherjee, A., Onstad, L., & Lee, S. J. (2021). Sexual functioning in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, 27(1), 80.e81-80.e12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2020.09.027

Thygesen, K., Schjødt, I., & Jarden, M. (2012). The impact of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on sexuality: A systematic review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplantation, 47(5), 716–724.

Tierney, D. K. (2004). Sexuality following hematopoietic cell transplantation. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 8(1), 43–47.

Ussher, J. M., Perz, J., & Gilbert, E. (2015). Perceived causes and consequences of sexual changes after cancer for women and men: A mixed method study. BMC Cancer, 15(1), 1–18.

Utz, A. L., & Jagasia, S. (2013). Sexual dysfunction in long-term survivors: Monitoring and management. Blood and marrow transplantation long-term management: Prevention and complications (pp. 183–192). Wiley.

Varela, V. S., Zhou, E. S., & Bober, S. L. (2013). Management of sexual problems in cancer patients and survivors. Current Problems in Cancer, 37(6), 319–352.

Wang, Y. P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the beck depression inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 35(4), 416–431. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048

Yi, J. C., & Syrjala, K. L. (2009). Sexuality after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer Journal, 15(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1097/PPO.0b013e318198c758

Funding

This work was made possible by Grant KL2 RR 02415 (PI: Ehlers), CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SE, CP, and DG designed the study. SE, TB, and CH contributed to the acquisition of data. JK and KM analyzed the data. JV, JK, SE, KM, CP, ES, and KC interpreted the data. JV, JK, SE, and KM drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read the manuscript and have agreed with its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

Jennifer A. Vencill, Janae L. Kirsch, Keagan McPherson, Eric Sprankle, Christi A. Patten, Kristie Campana, Tabetha Brockman, Carrie Bronars, Christine Hughes, Dennis Gastineau, and Shawna L. Ehlers have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted in accordance with institutional review board policies and all participants provided informed consent (IRB: 08-006915).

Consent to Participate

Participants provided written, informed consent.

Consent to Publish

Participants signed informed consent and data is presented in aggregate.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Vencill, J.A., Kirsch, J.L., McPherson, K. et al. Prospective Association of Psychological Distress and Sexual Quality of Life Among Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Survivors. J Clin Psychol Med Settings (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-024-10013-9

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-024-10013-9