Abstract

Primary care physicians have an important role in identifying, treating, and referring children with psychosocial problems. However, there is a limited literature describing whether and how family physicians address psychosocial problems and why parents may not discuss children’s problems with physicians. The current study examined how family physicians address psychosocial problems and reasons that parents do not discuss children’s psychosocial problems with physicians. Results indicated that there are a variety of reasons involving parents, their perceptions of physicians, and the number of psychosocial problems reported, that may lead to fewer discussions of psychosocial problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In some medical settings, such as academic medical centers, psychologists provide frequent consultations to medical providers regarding patients and their families (e.g., Rodrigue et al., 1995). However, a large majority of children who have psychosocial difficulties are treated by physicians in primary care medical settings, not in tertiary care facilities. Bernal (2003) estimated that approximately 75% of children with psychiatric problems are treated in primary care. The primary care physician’s role in identifying, treating, and referring children with psychosocial problems has long been recognized by both physicians and mental health providers (Costello, 1986; Heneghan et al., 2008; Stancin, Perrin, & Ramirez, 2009). As physicians have been identifying psychosocial problems in children at increasing rates (Kelleher, McInerny, Gardner, Childs, & Wasserman, 2000), the question of how psychosocial problems are addressed in primary care settings has become particularly relevant.

Prior studies of primary care physicians’ practices indicate that, although parents report an interest in discussing concerns about their children’s psychosocial functioning, these conversations do not always occur. For example, among parents who had psychosocial concerns about their children, only 30 to 60% discussed these concerns with their children’s physician (Burklow, Vaughn, Valerius, & Schultz, 2001; Garrison et al., 1992; Horwitz, Leaf, & Leventhal, 1998). Perhaps providing a larger context for these findings is the literature on physician–patient communication. For example, research in this area has focused on the amount of information that physicians provide to patients, physician affect (e.g., tone of voice) when interacting with patients, communication style (e.g., empathy, directiveness), and the relationship between effective communication and health outcomes (Stewart, 1995; Waitzken, 1984; Williams, Wineman, & Dale, 1998). Due to the concern that physicians may not adequately address all of their patients’ needs during office visits (e.g., Joos, Hickam, & Borders, 1993), a variety of interventions to improve physician–patient communication have been implemented, to varying degrees of efficacy (see Kinnersley et al., 2008, for a review).

However, the physician–patient communication literature has generally focused on the discussion of adult patients’ physical health issues. Many unanswered questions remain regarding physician-parent communication around parents’ concerns about their childrens’ psychosocial functioning. For example, no studies could be identified that examine the reasons that parents do not discuss concerns about their children’s psychosocial functioning with physicians. Parents, for instance, may perceive physicians to be uninterested in discussing children’s psychosocial problems or may believe that physicians would not be able to help with children’s psychosocial problems. Parents may also be more likely to discuss concerns with physicians if they have a greater number of concerns about their children. Having a better understanding of the reasons that parents do not discuss their children’s psychosocial problems with primary care providers may inform efforts to increase accessibility to mental health care.

The vast majority of research on how physicians address children’s psychosocial problems has focused on pediatricians (e.g., Burklow et al., 2001) or more generally, “primary care physicians” (e.g., Garrison et al., 1992). Similarly, clinical child and pediatric psychologists’ research and clinical collaborations with primary care practitioners, as well as recent guidelines for physicians on diagnosis of child behavioral problems, have focused primarily on pediatricians (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2001; Stancin et al., 2009).

There has been a comparatively smaller focus on family physicians as a unique group of medical providers. Family physicians, however, are medical providers for approximately one-third of U.S. children (Phillips, Bazemore, Dodoo, Shipman, & Green, 2006). Moreover, it may be important to examine family physicians as a unique group because family physicians are specifically educated to have a biopsychosocial perspective on health and to include health promotion in their treatment paradigms (Phillips & Haynes, 2001).

The limited literature examining family physician identification and management of child psychosocial problems suggests that family physicians identify psychosocial problems in approximately 15% of their pediatric patients. Following identification of a psychosocial problem, physicians most often reported scheduling a follow-up appointment, providing reassurance and support or advice, and monitoring of the reported symptoms (Wildman, Kinsman, Logue, Dickey, & Smucker, 1997). Other investigators have examined how family physicians and pediatricians, as a group, manage psychosocial problems, and the relation between communication techniques and parent satisfaction when children have psychosocial problems (Gardner et al., 2000; Hart, Kelleher, Drotar, & Scholle, 2007). However, there have been few investigations focused on family physicians and few studies have included parental report of children’s psychosocial problems.

Due to the limitations of the existing literature, and given that a large number of children are seen in family practice, it seems important to examine, from the perspective of parents, whether and how family physicians address children’s psychosocial problems. Obtaining a better understanding of the types of psychosocial problems that parents report in the family practice setting, whether parents discuss these problems with family physicians, why parents may not discuss psychosocial problems, and predictors of whether parents discuss psychosocial problems may inform family physicians’ mental health treatment efforts. The current study therefore examined the types of psychosocial problems parents report in a family practice, whether and how family physicians address parents’ concerns about their children’s psychosocial functioning, and reasons that parents do not discuss their concerns with physicians. In addition, the current study examined whether an increased number of psychosocial concerns predicts greater odds of discussing psychosocial problems.

Method

Participants

Participants were 232 parents of children ranging in age from 2 months to 18 years (M = 8.7 years, SD = 5.5 years). Approximately half (51%) of the children were male. Parents reported children’s ethnicity as Caucasian (87%), African-American (3.7%), American Indian or Alaska Native (1.3%), Asian (1.7%), Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (.4%), or “other ethnicity” (6%). Parent’s level of education ranged from “never graduated high school” to “attained a professional degree,” with a median of “completed graduate program” and a mode of “completed college.” Mean annual family income was $65,000 (SD = $9,000).

All children were patients at a large, private family medicine practice in the Midwest, comprised of 22 physicians. On average, children had been patients in the clinic for 50.8 months (SD = 52.9 months) and visited the clinic every 6 months (SD = 5 months). On the day that children and their parents participated in the current study, the reasons for children’s visit to the family medicine clinic included illness (57.8%), annual exam (15.1%), minor physical injury (9.5%), behavioral/emotional problem (5.2%), MRI, CT, or Ultrasound (.4%), and other reasons (12.1%).

Measures

Demographics

Parents completed several demographic questions about their child (e.g., gender, age, ethnicity) and about themselves (e.g., total family income, highest level of education).

Psychosocial Concerns

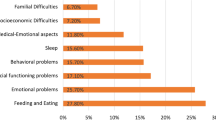

Parents’ concerns about children’s psychosocial functioning were measured using an investigator-designed questionnaire based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Primary Care (DSM-PC), Child and Adolescent Version (American Academy of Pediatrics, 1996). Investigators designed the psychosocial concerns questionnaire to minimize participant burden, and to maximize the practicality of using such an instrument in a busy family practice clinic. Parents were asked to check off, on a list of 25 items, any psychosocial concerns that had been a significant problem within the last year. Psychosocial concerns spanned five primary categories (see Table 1 for categories of concerns and individual items).

Parents were asked whether they discussed any of the reported psychosocial problems with the physician. If parents reported discussing their concerns about their child’s psychosocial functioning with the family physician, they were asked whether the physician prescribed a medication for the problem, and whether the physician referred the child to a counselor, psychologist, or psychiatrist. If parents reported not discussing their concerns with the physician, they used a 4-point likert scale (ranging from “not at all” to “very much”) to endorse to what extent the reasons (provided in a list) explained why they did not discuss the psychosocial problems. The reasons included: time limitations, the physician seemed too rushed, the physician seemed uninterested, parent did not feel comfortable discussing the psychosocial problems, the physician would not be able to help, and the child was already receiving services for the psychosocial problem(s). All parents were asked (yes or no) if they would like to talk to the physician about their child’s behavioral/emotional issues and if they believed it appropriate to discuss these issues with a family physician. In addition, all parents reported (yes or no) whether their child had already received a diagnosis for a behavioral/emotional problem. These questions were based on the existing literature describing physician–patient interactions about psychosocial issues (e.g., Burklow et al., 2001; Hickson, Altemeier, & O’Connor, 1983; Meredith et al., 1999; Rushton, Bruckman, & Kelleher, 2002).

Procedures

Over the course of 2 weeks, parents of children who were general admissions patients in the family practice (patients scheduled for well-child visits or illness) were asked by the reception staff to participate in the current study. Due to the study design necessitated by the university Institutional Review Board and for purposes of protecting patient privacy, the investigators had access only to the completed forms and could not have access to information about those approached or who declined. However, based on the clinic’s records of the number of appointments on the days of solicitation, the current project enrolled 17% of all eligible patients. Clinic administrators confirmed that participants in this study were representative of the larger clinic population.

Interested parents were presented with a written description of the study that did not explicitly mention that the study was examining how physicians and families handled children’s psychosocial problems. Parents completed the questionnaire after the medical visit. In addition, if parents accompanied more than one child to the clinic, parents were asked to answer the questionnaires for the child whose birthday was closest to the day of their participation in the study. All responses remained anonymous and could not be linked to existing medical records.

Results

On average, parents reported that their children had 1.3 psychosocial problems (SD = 1.9). The minimum number of psychosocial problems endorsed was 0 and the maximum was 19 (see Table 2). The most frequently endorsed psychosocial problems are included in Table 1. Of parents who endorsed at least one psychosocial concern, 8.2% of children already had a diagnosis for a behavioral or emotional problem, 60.6% reported wanting to talk with the physician about the problem(s), and 88.5% reported that it is appropriate to discuss psychosocial problems with physicians. In the entire sample of children, 6.5% of children already had a diagnosis for a behavioral or emotional problem.

Almost half (48%) of all parents reported that they would like to be able to discuss psychosocial concerns about their children with the physician, and 84.1% believed it is appropriate to discuss children’s psychosocial concerns with the physician. However, of those parents who endorsed at least one psychosocial concern for their children, only 27% discussed the concern(s) with the physician (see Table 2 for the rates of discussion for different psychosocial problems and Table 3 for the rates of discussion for parents reporting different numbers of problems). Parents endorsed a range of reasons that they did not discuss their concerns with the physician (see Table 4). Of those parents who discussed the concern(s) about their children’s psychosocial functioning with the physician, 30.0% were prescribed medication, 10.0% were referred to a psychologist or counselor, and 3.3% were referred to a psychiatrist. Finally, 67.7% of all parents reported that they would like the family practice to have a psychologist or counselor on staff.

Logistic regression was used to determine whether number of psychosocial problems endorsed by parents predicted whether parents discussed the psychosocial problem(s) with physicians. Power analyses based on Burklow et al.’s (2001) findings and Hsieh’s (1989) logistic regression sample size tables indicated that the current study required a sample size of between 180 and 536 to detect a 5–10% increase in likelihood of discussing psychosocial problems with a doctor (with 80% power). This suggests the current sample had a reasonable chance of detecting a 5–10% increase in likelihood of discussing psychosocial problems. Results indicated that the odds of discussing psychosocial problems with physicians increased as parents reported more psychosocial problems (χ2 = 119.95, df = 1, p < .001). Specifically, for each additional psychosocial problem reported, the odds of parents discussing the problems with physicians were 1.3 times the odds of parents not discussing the problems with physicians (odds ratio = 1.3, likelihood ratio χ2 = 29.4, df = 1, p < .001). The likelihood ratio test was used to determine whether a model including “number of psychosocial problems reported” as a predictor (a more complex model) accounted for more variance than a model with the intercept alone (a more restricted model). The likelihood ratio indicated that the more complex model accounted for significantly more variance than the restricted model.

Because parents who endorsed at least one psychosocial problem might constitute a different population from those who did not endorse any psychosocial problems, a second logistic regression, including only parents who endorsed one or more psychosocial problems, was completed. Similar to the results of the first logistic regression, the results indicated that the odds of discussing psychosocial problems with physicians increased as parents reported more psychosocial problems (χ2 = 8.08, df = 1, p = .004) and the likelihood ratio test comparing the more complex to the restricted model was significant (likelihood ratio χ2 = 8.09, df = 1, p < .005). Specifically, the results indicated that for each additional psychosocial problem reported, the odds of parents discussing the problems with physicians were 1.2 times the odds of parents not discussing the problems with physicians (odds ratio = 1.2).

Figure 1 displays the logistic regression results in terms of probabilities. When parents endorsed one psychosocial problem, the probability that they talked to the physician about the problem was .09. When parents endorsed two psychosocial problems (the approximate mean number of problems endorsed), the probability that parents discussed the problems with physicians was .12. In contrast, when parents endorsed 19 psychosocial problems (the maximum number of psychosocial problems endorsed), the probability that parents discussed the problems with physicians was .92. The median effective level for the current sample was 9.8, thus indicating that when the number of psychosocial problems endorsed was 10, parents were approximately equally likely to discuss the problems with the physician or not discuss the problems.

Discussion

Results of the current study suggest that although parents reported wanting to discuss a range of psychosocial problems with family physicians, they often did not, for a variety of reasons. The reasons that parents did not discuss the psychosocial problems with physicians provide several suggestions for how to increase communication between physicians and children’s caregivers about psychosocial issues and ways that psychologists can collaborate with physicians to provide comprehensive clinical care.

Consistent with previous studies of pediatric primary care practices (Burklow et al., 2001; Horwitz et al., 1998), parents endorsed that it is appropriate to discuss children’s psychosocial problems with physicians. However, also consistent with previous studies, of those parents who might be the most interested in discussing their children’s psychosocial problems with physicians (parents who reported that their children had at least one psychosocial problem), only a relatively small number (27%) discussed the psychosocial problems with physicians. As a result, family physicians may not be meeting the mental health needs of some pediatric patients.

Parents reported a variety of reasons that they did not discuss their children’s psychosocial problems with family physicians. Parents may not feel comfortable discussing children’s psychosocial problems with medical physicians and may not perceive these physicians as competent in addressing psychosocial problems. In addition, parents may not raise psychosocial problems in their discussions with physicians if children are already receiving mental health services or if they preferred to focus on physical health problems.

The current findings also suggest that the odds of parents talking with physicians about children’s psychosocial problems decreased if they had fewer psychosocial concerns. This result remained relatively unchanged, even when examining the subsample of parents who endorsed at least one psychosocial problem. The probability that parents discussed the psychosocial concern(s) with physicians ranged widely (from .09 to .92), depending on the number of concerns parents had. This suggests that parents identifying a greater number of psychosocial concerns for their children are more likely to discuss the concerns with physicians, and specifically, that parents endorsing a fairly high number of psychosocial problems (10 or more) were more likely to talk with physicians than not. Perhaps parents with more psychosocial concerns for their children experience more distress and thus may be more likely to mention the concerns to physicians. Conversely, this finding also implies that physicians may need to inquire about psychosocial problems if parents do not volunteer their concerns. Although some parents may have fewer concerns for their children, these concerns may still be severe and warrant further treatment, perhaps by a psychologist or other mental health professional. It may be particularly important for physicians to proactively inquire about psychosocial concerns given the findings described earlier whereby some parents reported not feeling comfortable discussing psychosocial problems with physicians. In summary, both parents and physicians may contribute to the lack of discussion about children’s psychosocial problems during family practice visits.

The percentage of parents reporting at least one psychosocial problem in the current study (45.7%) was higher than rates identified in previous studies (e.g., 18.7%; Kelleher et al., 2000). This may be because of the manner in which the problems were reported. Parents in the current study may have reported more developmentally typical problems (e.g., sleeping issues for younger children) than parents in other studies. In addition, while parents in the current study were asked to report psychosocial problems occurring within the last year, previous studies focused on psychosocial problems at the time of assessment only (e.g., Kelleher et al., 2000) or on children who had higher scores on measures such as the Pediatric Symptoms Checklist (Gardner et al., 2000). In the context of the current study, parents may have also reported on developmentally consistent problems occurring within the last year but which were not occurring at present. Future studies may need to investigate how the prevalence of identified psychosocial problems might be altered when different problems are included or excluded or when different time ranges are assessed (e.g., shorter to longer time spans).

To our knowledge, this is the first study of how family physicians, as a unique group of health care providers, address parent-reported child psychosocial problems. Moreover, the findings and implications of the current study may apply equally to other pediatric primary care providers (e.g., pediatricians), particularly in light of evidence that family physicians and pediatricians do not differ significantly on the identification and treatment of children’s psychosocial problems (Gardner et al., 2000). However, due to the dearth of research on how children’s psychosocial problems are addressed in family practice, future studies describing physicians’ practices and parents’ perspectives are needed. In particular, future research may address limitations of the current study by including physicians’ assessments of psychosocial problems in children, physicians’ perspectives on whether and how they addressed parent-reported psychosocial concerns, and ratings of the severity of psychosocial problems. Future studies should also extend the current methodology and findings by conducting reliability and validity studies of the measure used in this study, examining other family practices, including those serving families of a lower socioeconomic status, and using other measures of psychosocial problems such as the Pediatric Symptom Checklist (e.g., Jellinek et al., 1999). Future studies may also assess for other ways that physicians might manage or address psychosocial problems (e.g., scheduling another appointment to discuss psychosocial issues in greater depth). Although the sample obtained in the current study was representative of the clinic, it would be informative, using larger sample sizes accrued through a higher participation rate, to test other potentially important predictors of conversations about children’s psychosocial problems (e.g., developmental level or age, whether a child is already receiving mental health services, extent of prior relationship with physician, primary reasons for the medical visit), and whether certain psychosocial problems (e.g., ones that are viewed as “physical” such as sleeping or eating difficulties) are discussed more often than other problems.

In order to better meet the needs of children with psychosocial problems frequently seen in family practice, a range of approaches or interventions might be considered. Children’s caregivers and family medicine physicians, for instance, may benefit from information about the importance of discussing children’s psychosocial problems and physicians’ qualifications to discuss these problems with families. In addition, as mentioned earlier, physicians may need to proactively assess parent’s psychosocial concerns when parents perceive children to be anxious or when parents have fewer concerns. Even though parents may have fewer concerns, the psychosocial problems may still greatly impact the child and family.

The literature on physician–patient communication reviewed earlier may provide ideas for how family physicians can foster discussions with parents about children’s psychosocial issues. While billing for appointments focused on psychosocial issues can be challenging (e.g., Wells, Kataoka, & Asarnow, 2001), it is likely that family physicians will be motivated to address psychosocial issues due to their training in identifying, treating, and referring patients with psychosocial problems (Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors, 2008) and the substantial numbers of children presenting with psychosocial problems (Kelleher et al., 2000; Wildman et al., 1997).

The development and testing of educational interventions (e.g., for physicians) will be particularly important given the mixed results of studies examining physician management of psychosocial problems (see Bower, Garralda, Kramer, Harrington, & Sibbald, 2001, for a review). Due to their clinical and research training, psychologists could be instrumental in designing, implementing, and evaluating educational and other interventions. For example, clinical psychologists could educate family physicians on how to briefly assess for psychosocial problems (especially given time limitations) and how to make appropriate referrals to mental health professionals if needed. Psychologists might also provide physicians with specific referrals in their geographic area or provide clinical services within family practice. If psychologists were to provide services within a family practice, they might provide a combination of anticipatory guidance related to common developmental concerns (e.g., toileting) and targeted intervention and/or referral for problems that are more severe. Furthermore, psychologists could provide early detection of and intervention for developmental or psychosocial concerns.

While further research on the effectiveness of collaborations between psychologists and physicians is certainly needed (Bower et al., 2001), existing models of collaborations between psychologists and physicians indicate that parents are highly satisfied with mental health services in the context of primary care. Furthermore, these collaborations can have a significant impact on the treatment of children’s psychosocial problems and can lead to increased rates of referral for mental health services (Bray & Rogers, 1995; Kanoy & Schroeder, 1985; Riekert, Stancin, Palermo, & Drotar, 1999). The family medicine setting, however, seems particularly under-utilized as a venue for clinical psychologists’ practice and might be a fruitful context for future research on psychologist-physician collaboration. Encouragingly, results of the current study indicate that a majority of parents would like a psychologist or counselor on staff at the family practice clinic. Existing models of collaboration and the developing literature may provide ideas for how clinical psychologists can initiate and maintain collaborations with family physicians (Kelleher, Campo, & Gardner, 2006; McDaniel, Belar, Schroeder, Hargrove, & Freeman, 2002; Schroeder, 2004; Stancin et al., 2009). The reality of financial reimbursement for psychological services in medical settings will restrict some expansion and types of activities. Medical practices may determine the value-added benefit of psychological services and whether they will subsidize them (e.g., early detection of psychosocial problems, provision of anticipatory guidance). Funding for direct patient care would be limited by health plans wherein referral and diagnoses will dictate reimbursement.

In summary, the results of the current study suggest that discussions between parents and family physicians about children’s psychosocial problems may not occur for a variety of reasons. The reasons identified support the notion that interventions to increase discussions of psychosocial concerns could target caregivers and physicians themselves. Implementing such interventions will help to ensure that as many children as possible receive adequate services for psychosocial problems.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (1996). The classification of child and adolescent mental diagnoses in primary care: Diagnostic and statistical manual for primary care. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics.

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2001). The new morbidity revisited: A renewed commitment to the psychosocial aspects of pediatric care. Pediatrics, 108, 1227–1230.

Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. (2008). Recommended curriculum guidelines for family medicine residents: Human behavior and mental health. Retrieved October 19, 2009, from http://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/aboutus/specialty/rpsolutions/eduguide.html.

Bernal, P. (2003). Hidden morbidity in pediatric primary care. Pediatric Annals, 32, 413–418.

Bower, P., Garralda, E., Kramer, T., Harrington, R., & Sibbald, B. (2001). The treatment of child and adolescent mental health problems in primary care: A systematic review. Family Practice, 18, 373–382.

Bray, J. H., & Rogers, J. C. (1995). Linking psychologists and family physicians for collaborative practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 26, 132–138.

Burklow, K. A., Vaughn, L. M., Valerius, K. S., & Schultz, J. R. (2001). Parental expectations regarding discussions on psychosocial topics during pediatric office visits. Clinical Pediatrics, 40, 555–562.

Costello, E. J. (1986). Primary care pediatrics and child psychopathology: A review of diagnostic, treatment, and referral practices. Pediatrics, 78, 1044–1051.

Gardner, W., Kelleher, K. J., Wasserman, R., Childs, G., Nutting, P., Lillienfeld, H., et al. (2000). Primary care treatment of pediatric psychosocial problems: A study from pediatric research in office settings and ambulatory sentinel practice network. Pediatrics, 106, e44–e53.

Garrison, W. T., Bailey, E. N., Garb, J., Ecker, B., Spencer, P., & Sigelman, D. (1992). Interactions between parents and pediatric primary care physicians about children’s mental health. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 43, 489–493.

Hart, C. N., Kelleher, K. J., Drotar, D., & Scholle, S. H. (2007). Parent-provider communication and parental satisfaction with care of children with psychosocial problems. Patient Education and Counseling, 68, 179–185.

Heneghan, A., Garnger, A. S., Storfer-Isser, A., Kortepeter, K., Stein, R. E. K., & Horwitz, S. M. (2008). Pediatricians’ role in providing mental health care for children and adolescents: Do pediatricians and child and adolescent psychiatrists agree? Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 29, 262–269.

Hickson, G. B., Altemeier, W. A., & O’Connor, S. (1983). Concerns of mothers seeking care in private pediatric offices: Opportunities for expanding services. Pediatrics, 72, 619–624.

Horwitz, S. M., Leaf, P. J., & Leventhal, J. M. (1998). Identification of psychosocial problems in pediatric primary care: Do family attitudes make a difference? Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 152, 367–371.

Hsieh, F. Y. (1989). Sample size tables for logistic regression. Statistics in Medicine, 8, 795–802.

Jellinek, M. S., Murphy, M., Little, M., Pagano, M. E., Comer, D. M., & Kelleher, K. J. (1999). Use of the Pediatric Symptom Checklist to screen for psychosocial problems in pediatric primary care: A national feasibility study. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 153, 254–260.

Joos, S. K., Hickam, D. H., & Borders, L. M. (1993). Patients’ desires and satisfaction in general medicine clinics. Public Health Report, 108, 751–759.

Kanoy, K. W., & Schroeder, C. S. (1985). Suggestions to parents about common behavior problems in a pediatric primary care office: Five years of follow-up. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 10, 15–30.

Kelleher, K. J., Campo, J. V., & Gardner, W. P. (2006). Management of pediatric mental disorders in primary care: Where are we now and where are we going? Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 18, 649–653.

Kelleher, K. J., McInerny, T. K., Gardner, W. P., Childs, G. E., & Wasserman, R. C. (2000). Increasing identification of psychosocial problems: 1979–1996. Pediatrics, 105, 1313–1321.

Kinnersley, P., Edwards, A., Hood, K., Ryan, R., Prout, H., Cadbury, N., et al. (2008). Interventions before consultations to help patients address their information needs by encouraging question asking: Systematic review. BMJ, 337, a485–a495.

McDaniel, S. H., Belar, C. D., Schroeder, C., Hargrove, D. S., & Freeman, E. L. (2002). A training curriculum for professional psychologists in primary care. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 33, 65–72.

Meredith, L. S., Rubenstein, L. V., Rost, K., Ford, D. E., Gordon, N., Nutting, P., et al. (1999). Treating depression in staff-model versus network-model managed care organizations. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 14, 39–48.

Phillips, R. L., Bazemore, A. W., Dodoo, M. S., Shipman, S. A., & Green, L. A. (2006). Family physicians in the child health care workforce: Opportunities for collaborations in improving the health of children. Pediatrics, 118, 1200–1206.

Phillips, W. R., & Haynes, D. G. (2001). The domain of family practice: Scope, role and function. Family Medicine, 33, 273–277.

Riekert, K. A., Stancin, T., Palermo, T. M., & Drotar, D. (1999). A psychological behavioral screening service: Use, feasibility, and impact in a primary care setting. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 24, 405–414.

Rodrigue, J. R., Hoffmann, R. G., Rayfield, A., Lescano, C., Kubar, W., Streisand, R., et al. (1995). Evaluating pediatric psychology consultation services in a medical setting: An example. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 2, 89–107.

Rushton, J., Bruckman, D., & Kelleher, K. (2002). Primary care referral of children with psychosocial problems. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescents Medicine, 156, 592–598.

Schroeder, C. (2004). A collaborative practice in primary care: Lessons learned. In B. G. Wildman & T. Stancin (Eds.), Treating children’s psychosocial problems in primary care. Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

Stancin, T., Perrin, E. C., & Ramirez, L. Y. (2009). Pediatric psychology and primary care. In M. C. Roberts & R. G. Steele (Eds.), Handbook of pediatric psychology (4th ed., pp. 630–648). New York: Guilford Press.

Stewart, M. A. (1995). Effective physician–patient communication and health outcomes: A review. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 152, 1423–1433.

Waitzken, H. (1984). Doctor–patient communication: Clinical implications of social scientific research. JAMA, 252, 2441–2446.

Wells, K. B., Kataoka, S. H., & Asarnow, J. R. (2001). Affective disorders in children and adolescents: Addressing unmet needs in primary care settings. Biological Psychiatry, 49, 1111–1120.

Wildman, B. G., Kinsman, A. M., Logue, E., Dickey, D. J., & Smucker, W. D. (1997). Presentation and management of childhood psychosocial problems. Journal of Family Practice, 44, 77–84.

Williams, S., Wineman, J., & Dale, J. (1998). Doctor–patient communication and patient satisfaction: A review. Family Practice, 15, 480–492.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Dr. Pascal DeBoeck for his assistance with the statistical analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, Y.P., Messner, B.M. & Roberts, M.C. Children’s Psychosocial Problems Presenting in a Family Medicine Practice. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 17, 203–210 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-010-9195-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-010-9195-2