Abstract

Core self-evaluations (CSEs) are fundamental traits that represent an individual’s appraisal of his/her self-worth and competency. CSEs have been directly linked to numerous workplace outcomes, yet less is understood about the mediating mechanisms through which CSEs are related to outcomes. In this study, we examine the process through which CSEs promote favorable outcomes by examining the mediating role of both leader-member exchange (LMX) and work engagement in the CSE—organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) relationship. Using an approach-avoidance theoretical framework, we hypothesize that the relationship between CSEs and OCBs is mediated by the quality of the individual’s relationship with their leader (i.e., LMX quality) and his/her level of work engagement. Our results provide broad support for the hypothesized multiple mediation relationships whereby CSEs are indirectly related to OCBs through both LMX quality and work engagement. A discussion of these findings and their implications for both theory and practice is provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Since its introduction over 20 years ago, core self-evaluations (CSEs) have been the focus of considerable research among management scholars (Chang et al., 2012; Judge et al., 1997). This attention has generated empirical support for the positive relationship between CSEs and a considerable number of organizational phenomena, including job performance, job satisfaction, organizational commitment, occupational stressors, and strain (Joo et al., 2012; Judge & Bono, 2001; Kammeyer-Mueller et al., 2009). However, despite the extensive evidence that CSEs play a critical role in the workplace, far less research has been devoted to the examination of CSEs’ indirect relationships and the underlying mechanisms through which CSEs impact workplace outcomes (Chang et al., 2012).

Most commonly conceptualized as a higher order trait, CSEs represent an individual’s natural tendencies to feel and behave in a certain way. Yet, there is considerable need to examine the intervening mechanisms through which CSEs affect relationships and outcomes in the workplace. Failure to do so may result in the exaggeration of CSE’s direct effect on outcomes and overstatement of its explanatory power. In their review of the CSE literature, Chang and colleagues (2012) noted that less than 10% of the articles reviewed examined mediating variables through which CSEs operated and that over half of those that did focused on only two outcomes—job satisfaction and job performance. This limited examination of mediators has left our understanding of how CSEs lead to workplace outcomes in need of further development.

To address this paucity of research that examines the mediating mechanisms through which CSEs are related to workplace outcomes, we root our examination of mediators in the same two categories used in both the original conception (Judge et al., 1997) and most recent review (Chang et al., 2012)—situational appraisals and actions—as well as the dominant theoretical perspective employed in current CSE research, the approach-avoidance theoretical framework (Chang et al., 2012; Chiang et al., 2014; Elliot & Thrash, 2002; Ferris et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2020). By investigating the intervening mechanisms through which CSEs affect the workplace, we can advance our understanding of CSEs beyond vague tendencies and simplistic relationships with a limited set of outcomes to include a more nuanced and complete understanding of CSEs and their considerable effects on organizations. In this study, we examine the situational appraisal of the quality of one’s relationship with their leader (i.e., LMX quality) and the action of workplace engagement as mediators of the CSE-organizational citizenship behaviors (OCBs; Organ, 1988) relationship.

Of the possible situational appraisals, an employee’s relationship with their leader “may be the single most powerful connection an employee can build in an organization” (Hui et al., 2004, p. 233). Because supervisors often serve as an important source of valuable work-related resources (e.g., information, knowledge, experience, opportunities; Janssen & Van Yperen, 2004), the quality of an individual’s relationship with their leader is critical to accessing these resources. As such, leader–follower relationship quality serves as a natural conduit through which individuals can attain resources that allow them to realize their full potential in the workplace (Dulebohn et al., 2012). In addition to the appraisal and access to critical resources, we consider the individual’s actions and investment of these resources in the form of workplace engagement. Characterized by higher levels of energy, involvement, and immersion in one’s work (Schaufeli et al., 2002), it is through engagement that CSEs and LMX quality result in higher levels of OCBs.

This study makes several contributions to the literatures on CSEs and OCBs. First, we develop and test a multiple mediation model which examines the mechanisms through which an individual’s CSE operates in the workplace. This offers a more nuanced understanding of how one’s traits shape and influence the workplace environment. Second, we accomplish this by examining LMX as a situational appraisal mediator (extending prior research) and work engagement (replicating prior research) as an action mediator. By utilizing the situational appraisal-action mediator categorization and grounding our examination in the approach-avoidance theoretical framework (Elliot & Thrash, 2002; Ferris et al., 2011), we are provided with the opportunity to build on prior work and not just understand if CSEs are related to workplace outcomes, but also how CSEs are related to workplace outcomes. More specifically, we garner insights regarding an individual’s assessment of themselves, their relationships, the resultant actions they decide to take, and how these affect critical outcomes in the workplace. Finally, the study provides preliminary evidence that individuals may engage in OCBs because of personality characteristics and not simply a motivation to reciprocate what they perceive as positive treatment by their organization or co-workers (Spanouli & Hofmans, 2021). In doing so, we provide a theoretical explanation for why CSEs are related to OCBs, affording more unique insights regarding CSEs and how they impact the workplace.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

Core Self-Evaluations (CSEs)

Core self-evaluations (CSEs) refer to an individual’s overall assessment of their own self-worth, competences, and capabilities and are composed of four personality traits: self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, emotional stability (or conversely, neuroticism), and locus of control (Chang et al., 2012; Judge et al., 1997). Self-esteem refers to an individual’s assessment of their own self-worth (Rosenberg, 1965). Generalized self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their ability to perform in various situations (Bandura, 1997; Chen et al., 2001). Emotional stability refers to an individual’s ability to remain calm and feel secure in a variety of circumstances (Eysenck, 1990). Finally, locus of control refers to an individual’s judgment of the degree to which they (i.e., internal) or some other (i.e., external) can impact one’s environment (Rotter, 1966). According to Judge and colleagues (2003, p. 304), an individual with a high CSE is “someone who is well adjusted, positive, self-confident, efficacious, and believes in his or her own agency.”

Extensive empirical research provides evidence of the positive relationship of CSE with favorable outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction, job performance, motivation and organizational commitment; Bono & Judge, 2003; Chang et al., 2012; Joo et al., 2012), as well as its negative relationship with adverse outcomes (e.g., stress, negative affectivity; Chang et al., 2012; Gagne & Deci, 2005; Judge & Bono, 2001). CSEs play a critical role in the way individuals engage in the workplace. Indeed, high-CSE individuals are more likely to take ownership of their careers by appraising their surroundings and taking more constructive actions in the workplace. As noted previously, CSE research is limited in two ways, the limited consideration of outcomes (i.e., job performance and job satisfaction) and inadequate examination of intervening mechanisms. To advance the understanding of CSEs, both limitations must be addressed.

First, it is critical to expand the examination of outcome variables to include behaviors that extend beyond task performance expectations and include behaviors which may be beneficial, but are not explicitly expected (i.e., OCBs). This will promote a more complete understanding of how influential CSEs are in the workplace. The approach-avoidance theoretical framework provides a particularly insightful lens to understanding the CSE-OCB relationship. This framework suggests that individuals have “biological sensitivities that are responsible for immediate affective, cognitive, and behavioral” responses (Elliot & Thrash, 2002, p. 806). Individuals with an approach temperament are predisposed to pursue positive and desirable stimuli/outcomes, whereas individuals with an avoidance temperament attempt to evade or prevent negative and undesirable stimuli/outcomes.

Prior research has demonstrated that high-CSE individuals have a strong approach temperament and a low avoidance temperament (Ferris et al., 2011). Thus, high-CSE individuals are more sensitive to positive stimuli and less sensitive to negative stimuli. Conversely, low-CSE individuals are more sensitive to negative stimuli and less sensitive to positive information. Chang and colleagues (2012) describe how the approach-avoidance perspective and these differences in sensitivities are uniquely efficacious in explaining the relationship between CSEs and various workplace outcomes. High-CSE individuals also believe they can perform well; that they can affect outcomes positively; and that they have a role in maintaining favorable workplace social interactions (Judge et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2000). Moreover, they exert more effort in the workplace (Colbert et al., 2004), and they view their work as intrinsically valuable and important (Judge et al., 1998). As such, they are motivated to engage in OCBs that “contribute to the creation of structural, relational, and cognitive aspects of social capital” (Joo & Jo, 2017, p. 467) and/or that provide opportunities for proximal positive feedback or responses to their actions. This could include a range of OCB activities including helping coworkers, assisting one’s supervisor, sharing information with colleagues, and/or assisting with onboarding of new employees, among others.

Second, both the amount and variety of mediating mechanisms must be expanded, as theory cannot advance without a coherent theoretical rationale for selecting relevant mediators to understand the effects of CSE. Chang et al. (2012) offered that “while it is possible that CSE operates through multiple, distinct mechanisms, this contention seems presumptuous … and lacks parsimony” (p. 105). Therefore, we root our examination of mediators of CSEs in two theoretical categories—situational appraisals and actions (Chang et al., 2012; Judge et al., 1997). As research on mediating mechanisms in the OCB-performance relationship is limited, we extend CSE research by examining LMX as a situational appraisal, and we replicate research that has examined work engagement as an action mediator, thereby addressing calls to build on and extend prior work in mediation studies (Chang et al., 2012).

Situational appraisal mediators include an individual’s “cognitions and perceptions regarding the job (e.g., job characteristics) and judgments or estimations of how other things relate to the self (e.g., social comparisons)” (Chang et al., 2012, p. 102). Action mediators refer to the behaviors “people take as a result of their core evaluations (e.g., job selection, persistence in the face of setbacks, attaining practical success)” (Judge et al., 1997, p. 176). Among the few studies to have considered the intervening role of situational appraisals, Brown and colleagues (2007) found that CSEs were directly and negatively related to both upward and downward social comparisons, and it was through this reduction in social comparisons that CSEs led to higher levels of both job satisfaction and affective organizational commitment as well as lower levels of job search behaviors.

Though still in its infancy, the examinations of action-based intervening mechanisms of CSEs are more commonly conducted. For instance, Srivastava and colleagues (2010) conducted a study which found that high-CSE individuals actively seek and choose jobs with higher levels of task complexity. It is through this action that CSEs are indirectly related to heightened levels of work satisfaction. Further extending Srivastava and colleagues’ (2010) work identifying the decision to select and opt into more complex jobs, Kim and Beehr (2020) found that high-CSE individuals were more likely to actively engage in job crafting. They found that CSEs were indirectly related to well-being, including work-family enrichment, flourishing, and life satisfaction, through the actions of job crafting which were designed to advantageously modify the structures and demands of their job. These preliminary studies generated useful insights regarding the situational appraisal- and action-based mechanisms through which CSEs ultimately prompt workplace outcomes. In this article, we extend this stream of research by examining the situational appraisal of one’s evaluation of the quality of their relationship with their leader (i.e., LMX quality) and the action of workplace engagement as mediators of the CSE – OCB relationship.

Leader-Member Exchange (LMX)

The relationship an individual has with their leader is likely to be the most important and consequential influence on an individual and their behavior in the workplace (Hui et al., 2004; Laschinger et al., 2007). Indeed, in their recent review of the relational dynamics of leadership, Scandura and Meuser (2021) note “[t]he leader–follower relationship might be the most critical of all at work” and that “one cannot sanely argue that they are unimportant” (p. 1–2). As such, the quality of that relationship is among the most important situational appraisals which may serve as an intervening mechanism between CSEs and outcomes in the workplace, specifically OCBs. To do so, we ground our consideration of an individual’s relationship with their leader in leader-member exchange (LMX) theory. Leader-member exchange (LMX) theory posits that leaders develop unique, differential relationships with each of their followers such that these relationships range from low-quality to high-quality, where higher-quality relationships are characterized by higher levels of trust, affect, loyalty, contribution, and professional respect (Gerstner & Day, 1997; Graen & Scandura, 1987; Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Liden & Maslyn, 1998).

LMX theory draws from social exchange theory (Blau, 1964) to explain the dyadic relationship between leaders and followers. Social exchange theory suggests that the LMX relationship is characterized by the exchange of resources (e.g., rewards, opportunities, support) which extend beyond that which is contractually provided. As each party engages in the social exchange by performing a beneficial act, there is an understanding and expectation that the other party will reciprocate with some beneficial act in the future (Gouldner, 1960). As these acts are iteratively reciprocated, they mold the quality of the relationship and create “enduring social patterns” (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005, p. 882). As such, “social exchange tends to engender feelings of personal obligations, gratitude, and trust; purely economic exchange as such do not” (Blau, p. 94). Indeed, appraising the social exchange as equitable and beneficial (i.e., higher LMX) can create a positive relationship where one feels motivated to act and pursue continued engagement. However, appraising the social exchange as inequitable and nonbeneficial (i.e., lower LMX) can create a less positive relationship where one feels decreased motivation and avoids continued engagement. Indeed, high-CSE individuals and their higher approach temperament are likely to appraise their social exchange with their leader as equitable, while low-CSE individuals and their higher avoid temperament are likely to appraise their social exchange as inequitable. Ultimately, higher quality LMX relationships are likely to produce mutually beneficial exchanges for both the leader and the follower which go beyond the formal job description, whereas lower quality exchange relationships are likely to generate less beneficial exchanges which do not go beyond the core job requirements.

As mentioned previously, Judge and colleagues (2003, p. 304) noted that an individual with a high CSE is “someone who is well adjusted, positive, self-confident, efficacious, and believes in his or her own agency.” This kind of person is likely to appraise their relationship with their leader as both important and worthy of investment, and as both the individual and their leader invest in the relationship, they begin to form more positive perceptions of this relationship, ultimately allowing both parties to access benefits in the form of more positive workplace outcomes (Cogliser et al., 2009). Driven by their strong approach temperaments, high-CSE individuals are more likely to note the benefits of their LMX relationship to both form a more positive assessment of their relationship with their leader and take steps towards further enhancing its quality.

The quality of the leader-member relationship is developed through a three-stage dyadic process that includes role-taking, role-making, and role-routinization (Graen & Scandura, 1987). In the role-taking phase, individuals attempt to discover the abilities and motivations of the other member of the dyad through the process of offering and completing more work and evaluating whether the follower belongs to the in-group (i.e., those with high-quality exchanges) or the out-group (i.e., those with low-quality exchanges). Next, in the role-making phase, the leader and follower begin to establish mutual expectations through the repetitious completion of tasks. Lastly, in the role-routinization phase, the previously established mutual expectations stabilize and become predictable, forming a higher or lower quality relationship.

We offer that high-CSE individuals are more likely to be motivated to develop high-quality relationships with their leaders by engaging in the role-taking, role-making, and role-routinization processes. High-CSE individuals are likely to have a higher approach temperament, and as such, they are likely to be more proactive in shaping and molding their environment to be more advantageous to them accomplishing their goals. Feeling a stronger sense of ownership and responsibility for their actions, high-CSE individuals are likely to recognize the benefit of greater trust and access to resources that is characteristic of a higher quality LMX relationship. Given their predisposition to pursue more positive outcomes/stimuli, high-CSE individuals are inclined to engage in initiative-based behaviors to develop and maintain a higher quality LMX relationship (Li et al., 2010). Subordinates taking initiative in the form of increased effort, commitment, or performance are valuable and likely appreciated by leaders, likely resulting in reciprocation and the establishment of a high-quality, equitable exchange that is advantageous for both parties.

Indeed, Sears and Hackett (2011) also generated empirical evidence supporting this idea by showing that CSEs not only predict LMX quality, but that this relationship is mediated by both subordinate affect towards the leader and role clarity. They argued that because high-CSE individuals are highly motivated to effectively perform their jobs, they are likely to be proactive in seeking clarification regarding their role responsibilities. This role clarity seeking behavior is a critical component of the LMX relationship development process, often resulting in enhanced performance. This performance then leads to the leader’s granting benefits and resources (e.g., autonomy, opportunities, rewards) to the member.

In addition to role clarity, Sears and Hackett (2011) found support for the mediating role of subordinate affect towards the leader. While role clarity is critical in the earlier stages of LMX relationship development, how an individual feels about their leader is critical to the continued evolution of this relationship. Greater positive affect has been linked to stronger relationship building behaviors (Frederickson & Losada, 2005) and is an important component of LMX (Liden & Maslyn, 1998). Together, the enhanced role clarity and positive affect lead to a higher quality LMX relationship, providing individuals with necessary job resources and the expectation and willingness to more fully commit and engage in one’s work (Gouldner, 1960). Additionally, meta-analytic evidence supports the important associations between follower personality characteristics and OCBs as mediated by LMX (Dulebohn et al., 2012).

Work Engagement

Work engagement is defined as “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption” (Schaufeli et al., 2002, p. 74). Vigor involves a high level of energy and willingness to invest time and effort into one’s work, even in the face of adversity. Dedication is characterized by a high level of involvement in one’s work, resulting in a sense of enthusiasm. Absorption is a high level of concentration and immersion in one’s work, which results in the prompt passage of time (Bakker et al., 2014). Thus, high levels of work engagement are demonstrated by higher levels of energy, involvement, and immersion in one’s work. Given that high-CSE individuals have an approach temperament, they are more likely to be energized to engage in work and pursue and ultimately enjoy the positive experience associated with higher levels of work engagement.

An employee’s relationship with their leader is likely to be influential in determining the employee’s actions, including their level of work engagement. In support of this notion, meta-analytic evidence supports the positive relationship between LMX and work engagement (Christian et al., 2011). This research is primarily rooted in two related sources—resources and motivation. First, those with higher quality LMX relationships have been shown to receive greater resources, such as support and opportunities (Epitropaki & Martin, 2005; Gerstner & Day, 1997), often resulting in higher levels of performance (Dulebohn et al., 2012). Second, individuals in higher quality LMX relationships are more motivated (Martin et al., 2016).

Therefore, as high-CSE individuals are more likely to have an approach temperament and are more likely to be proactively engaged in work relationships, they are more likely to have higher quality LMX relationships. These higher quality relationships are likely to translate into greater work engagement. That is, as high-CSE individuals have higher quality work relationships with their leaders, they are more likely to become immersed and engaged in their roles. Consistent with Dulebohn and colleagues’ (2012) notion that LMX is particularly effective as a mediating mechanism that links individual attributes with workplace outcomes, it is through the enhanced LMX relationship that we expect CSEs to be related to work engagement. As such, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 1: LMX quality mediates the CSE-work engagement relationship.

Organizational Citizenship Behaviors (OCBs)

We also posit that LMX will mediate the CSE-OCB relationship. OCBs are defined as “individual behavior that is discretionary, not directly or explicitly recognized by the formal reward system, and in the aggregate promotes the efficient and effective functioning of the organization” (Organ, 1988, p. 4). This definition underscores three necessary elements of OCBs. First, the behavior must be considered discretionary. That is, the employee must voluntarily decide to act of their own volition. Second, the behavior must be considered outside of the purview of the formal job requirements affiliated with the position. Finally, the behavior must contribute to the overall mission of the organization.

Ferris and colleagues (2011) utilized the approach-avoidance framework to clarify the relationship between CSEs and OCBs. These authors found a positive direct relationship between CSEs and OCBs. However, when examining the indirect effects via approach motivation and avoidance motivation, no significant relationship was found between approach motivation and OCBs, but a significant relationship was found between avoidance motivation and OCBs. So, while CSEs and an individual’s approach-avoidance temperament are likely to be related to OCBs, less is known regarding how an individual's intrapersonal assessment of their own self-worth (i.e., CSE) affects their interpersonal assessment of their relationship with their leader (i.e., LMX quality) and ultimately performing OCBs.

As noted previously, Dulebohn and colleagues (2012) emphasized that LMX quality is based on the continuous and iterative interactions between the leader and the follower. Throughout these interactions, individuals engage in the social exchanges with their leader, exchanging resources which go beyond that which is contractually specified. As the leader offers resources which the subordinate deems beneficial, there is a natural expectation that the subordinate reciprocates. One such means of reciprocity is the performance of OCBs. Because OCBs are both discretionary and beneficial (Organ, 1988), they can be performed, withheld, or modified to a form of reciprocation which is appropriate in various situations. Additionally, followers appraising their relationship as high-quality are more likely to have similar workplace goals as their leaders and are often focused on improving their workplace through OCBs (Walumbwa et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012). Ilies et al. (2007) provided meta-analytic support for this relationship by showing a moderately strong, positive relationship between LMX quality and OCBs.

As discussed previously, we expect higher CSE individuals and their higher approach and lower avoidance temperaments to be more likely to appraise their relationship as important, of higher quality, and to be willing to engage in initiative-based behaviors to establish and maintain higher-quality, advantageous LMX relationships. Through this relationship appraisal and development process, individuals and their leaders are likely to coalesce around similar workplace goals and behave in a manner which helps to realize these goals, even if that means doing things which go above and beyond their contractual obligation (i.e., performing OCBs). Moreover, high-CSE individuals are likely to contribute to the functioning of the workgroup or organization, beyond what is required given that they define their roles more broadly and view their work as important. Thus, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 2: LMX quality mediates the CSE–OCBs relationship.

High-CSE individuals hold themselves in high regard and believe strongly in their ability to perform and be in control across various situations (Bono & Judge, 2003; Judge et al., 2000). Additionally, their approach temperament predisposes these employees to seek positive stimuli and opportunities for positive feedback. As a result, they are likely to be confident in their ability to meet the demands of the job and are more intrinsically motivated to invest themselves more fully into their job (Erez & Judge, 2001; Judge & Hurst, 2007). This tendency to confidently address job demands would suggest a positive relationship between CSEs and work engagement. Indeed, extant research has provided empirical evidence of this relationship (Haynie et al., 2017; Lee & Ok, 2016; Rich et al., 2010).

Work engagement leads to enhanced effort and focus on specific actions which contribute to task performance; it is also likely to result in behaviors which fall outside of the scope of task performance but meaningfully affect an individual’s overall effectiveness. Rather than discerning between what is required and what is not, individuals who experience higher levels of work engagement are likely to throw themselves more fully into their job and engage in whatever activity may be beneficial. Rich and colleagues (2010) suggested this reduced level of discernment when discussing the implications of work engagement’s mediating role in the CSEs-OCBs relationship. We follow this line of thinking and suggest that high-CSE individuals and their higher approach temperament are more likely to feel engaged. In turn, this engagement displaces the importance of what is considered required and what is considered discretionary, and instead focuses importance on effectiveness. Ultimately, this focus on effectiveness results in the performance of more OCBs. Thus, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 3: Work engagement mediates the CSE–OCBs relationship.

The previous hypotheses and the approach-avoidance theoretical framework presented above are important to our logic because they provide the theoretical linkages through which CSEs promote OCBs. We argue that this relationship can be explained by two things—the situational appraisal of an individual’s relationship with their leader and their action of work engagement. If an individual has a higher CSE, they are more likely to engage in the LMX relationship development process and ultimately experience and appraise a higher quality LMX. This LMX relationship would then serve as a means for facilitating job demands as well as the resources to meet those job demands, related to higher job engagement. Finally, by being more engaged in their work, individuals are likely to engage in any behaviors which might promote their effectiveness in the workplace, even if those behaviors fall outside of the scope of what is contractually obligated. Therefore, we argue that both LMX quality and work engagement will serve as mediating processes through which CSEs will be indirectly related to OCBs. Thus, we hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 4: CSE is indirectly related to OCBs through the mediating processes of both (a) LMX quality and, in turn, (b) work engagement.

Method

Sample and Procedure

We solicited Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) Master Workers to complete three waves of online surveys in exchange for a total of $2.91 as part of a broader study on individual’s experiences in the workplace. To ensure that we obtained an appropriate, representative sample, we made several decisions throughout the design, collection, and analyses that are consistent with Cheung and colleagues’ recommendations to overcome threats to study validity (Cheung et al., 2017). First, we required that all workers must be MTurk Master workers. An MTurk Master worker is a top worker in the MTurk marketplace that has been granted the MTurk Masters Qualification given to the most successful workers across tasks and studies based on their tenure as a worker, their ability to produce high-quality work, and their completion of a diversity of tasks. Second, we also mandated that our MTurk workers meet certain qualifications, including residency in the USA and a HIT (MTurk task) approval rating of 90% or greater. Their approval rating was mandated to facilitate high quality data. To attenuate the threat of participant inattentiveness, we included several attention check items and excluded all responses stemming from those who failed these. Consistent with Meade and Craig (2012), we employed instructed response items. An example item was, “I am currently using a computer. Mark strongly agree for this item.”

A notice was posted on Amazon MTurk for 3 days to recruit participants for surveys to be completed at three points in time, and interested participants were redirected to an online survey hosted by Qualtrics to begin the data collection. Participants were provided with information regarding the estimated duration of survey 1 (10 min), survey 2 (6 min), and survey 3 (6 min) along with the rate of compensation for the studies ($1.01 for the first survey, $0.90 for the second survey, and $1.00 for the third survey). We paid a higher rate of compensation (per time required) to complete surveys 2 and 3 to reduce attrition in our sample.

In the first wave of data collection, we collected employee demographic information as well as CSEs and LMX. Two weeks after respondents completed survey 1, email messages were sent through MTurk inviting respondents from survey 1 to complete the second survey. In the second survey, respondents completed work engagement items. Two additional follow-up emails (over 48 h) were sent before we closed the data collection. Given this design, the independent and dependent variables were separated in time to mitigate concerns regarding common-method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In the third wave of data collection, we asked respondents to complete information regarding tenure with their organization, tenure with their leader, job characteristics, and a measure of OCB. Again, we sent two follow-up emails before we closed the data collection.

Consistent with recommendations (Cheung et al., 2017) and previous MTurk research (e.g., Behrend et al., 2011), we excluded respondents who failed our conscious response items (N = 31) and who did not provide complete data for all three surveys. Our final matched sample included 343 MTurk workers, for a response rate of 72.46% from those who started survey 1 (N = 570) and 83.05% from those who started both surveys 1 and 2 (N = 413).

Our final sample (N = 343) was 49.8% male. The majority of the sample (84.26%) were white/Caucasian, whereas 7.29% identified as Black/African American, 4.66% as Asian, 0.29% as native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and 3.25% as multiracial or other race. The majority of our sample had been to college, with only one person reporting less than a high school degree, 9.91% having a high school degree or equivalent (e.g., GED), 32.94% with some college, 45.19% having earned a bachelor’s degree, and 11.66% with a graduate degree. Most of our respondents worked full-time (83.96%).

Measures

Core Self-Evaluations

We measured CSEs using Judge et al.’s (2003) 12-item scale (α = 0.93). Respondents were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed with statements such as: “Overall, I am satisfied with myself” and “When I try, I generally succeed,” using a seven-point response format (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Leader-Member Exchange

To assess LMX we used the seven-item measure (LMX-7) developed by Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995; α = 0.93). This measure contains items such as “How well does your leader understand your job problems and needs?” We employed the same five-point scale anchors provided in Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995) in our survey.

Work Engagement

We used the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale–9 developed by Schaufeli et al. (2006) to assess employee work engagement. This measure consists of nine items such as “I am enthusiastic about my job” with α = 0.96 and employs seven-point response anchors (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree).

Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Employee OCB was assessed with seven-point response anchors (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) using the scale developed by Williams and Anderson (1991). Respondents rated the extent to which they agreed with statements such as “I help others who have been absent from work” (α = 0.91).

Control Variables

Consistent with prior research on work engagement (e.g., Avery et al., 2007; Maslach & Leiter, 2008; Mauno et al., 2007) and OCB (Anand et al., 2010; Chen & Chiu, 2009), we used several demographic control variables in our analyses. These included gender (1 = Male, 2 = Female, 3 = Other); age (1 = 18–20, 2 = 21–29, 3 = 30–39, 4 = 40–49, 5 = 50–59, 6 = 60 or older); educational level (1 = less than high school, 2 = high school or equivalent degree, 3 = some college, 4 = associate’s degree, 5 = bachelor’s degree, 6 = graduate degree); and employment status (1 = full-time, 2 = part-time). Following prior research, we controlled for tenure with the leader as research has shown a positive relationship between dyadic tenure and LMX quality (Wayne et al., 2002). In addition, as tenure with the organization is likely to influence employee OCB (e.g., Anand et al., 2010), we controlled for this variable as well. Finally, as prior research has suggested that job characteristics can provide alternative explanations for employee engagement and OCB (Chen & Chiu, 2009; Shuck et al., 2011), we controlled for job complexity using ten items from the Job Diagnostic Survey (Hackman & Oldham, 1980)—two items for each of the five subscales of task variety (TV), task identity (TI), task significance (TS), autonomy (A), and feedback (F). Following Oldham and Cummings (1996), job complexity was calculated using the following formula: (TV + TI + TS)/3 × A x F.

Data Analysis

Construct Validity

Before testing the hypotheses, we first examined the construct validity of our study measures. Following Anderson and Gerbing (1988), we ran a series of confirmatory factor analyses using a maximum likelihood estimation method in AMOS 24.0. All indicators loaded significantly onto their constructs; standardized loadings ranged from 0.59 to 0.93, with a median loading of 0.80 and p values < 0.001. The average variance extracted for all of the latent factors exceeded 0.5, demonstrating evidence of convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010). Moreover, no significant cross-loadings were observed, and all factor correlations were modest, providing evidence of discriminant validity (Hair et al., 2010). Due to the sensitivity of the chi-square statistic to differences in large-sample data (Bentler & Bonett, 1980), we used model fit indices to assess model fit and misspecification (Bentler, 2007; Hu & Bentler, 1998, 1999). A four-factor model reflecting the study variables of CSEs, LMX, work engagement, and OCB fitted the data well (\({\chi }^{2}\) (554) = 1763.10, CFI = 0.88, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.05, TLI/NNFI = 0.87). Next, the four-factor model was compared against a single-factor model and a three-factor structure in which engagement and OCB were combined into one factor. The four-factor model demonstrated better fit to the data than the one-factor (\({\chi }^{2}\) (560) = 5113.04, \({\Delta \chi }^{2}\) (6) = 3349.94, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.55, RMSEA = 0.15, SRMR = 0.13) and three-factor models (\({\chi }^{2}\) (557) = 3148.41, \({\Delta \chi }^{2}\) (3) = 1385.31, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.74, RMSEA = 0.12, SRMR = 0.10).

To further assess the distinctiveness of our measures, we calculated the average variance extracted for each variable (AVE; Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The AVE for each of the four factors in the model was well above the squared of its maximum correlation with the other three variables. We also assessed discriminant validity of our constructs by conducting the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT) analysis (Henseler et al., 2015). According to the criteria specified by the authors, discriminant validity can be established by either comparing the HTMT calculated for each pair of constructs with a threshold of 0.85 or examining the 90% bootstrap confidence intervals for each HTMT. In the first method, discriminant validity is established if HTMT for each pair of constructs is lower than the 0.85 threshold. In the second method, discriminant validity is established if the confidence intervals do not include one (1). We utilized both methods and found support for the discriminant validity of our measures (Henseler et al., 2015).Footnote 1

Common Method Variance Assessment

Our cross-sectional with temporal lag design allowed us to separate the independent variables, dependent variables, and controls in time to mitigate concerns regarding common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In addition, we adopted a single-method-factor approach using an ideal marker variable to provide a statistical assessment of the possible biasing effects of common method variance. This method is one of the most frequently used statistical remedies for common method bias which estimates method biases at the proper level (i.e., measurement level; Conger et al., 2000; MacKenzie et al., 1999; Podsakoff et al., 2003). In the first wave of our data collection, we collected a latent marker variable, following Williams et al.’s (2010) guidelines on choosing an ideal marker variable. Specifically, following Simmering and colleagues (2015), we selected a three-item measure of “blue attitude” a priori since this variable has no conceptual relationship with our substantive variables and has the same method characteristics as our primary variables. An example item of the marker variable is “I prefer blue to other colors.” We added this latent common-method factor to our four-factor model and re-examined the model with all the indicator variables loading on that factor too. We then compared the two models to see which model offers a better fit. Including the marker variable resulted in model fit indices of χ2 (624) = 2606.13; RMSEA = 0.10; CFI = 0.82; SRMR = 0.07. The results showed that the overall model fit did not improve, and the relationships between indicators and the marker-factor were nonsignificant. This analysis provides support that common method bias did not influence our findings.

Analysis Strategy

To test the hypothesized relationships, we used Preacher and Hayes’ (2008) mediation procedure. This procedure allows for tests of direct and indirect effects and evaluates mediation effects based on the analysis of bootstrap confidence intervals (Hayes, 2009). Bootstrapping uses several resamples of the data to calculate an estimate of the population coefficient and provide confidence intervals around the estimated coefficient. Indirect effects are supported if the confidence interval around the estimated effect does not contain zero. In this study, 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals were calculated based on 5000 bootstrapped samples using PROCESS v3.5 in SPSS (Hayes, 2018).

Results

Table 1 provides the descriptive statistics and correlations among study and control variables. The correlations between CSEs and LMX, LMX and outcomes, and CSEs and outcomes are consistent with our prediction with respect to their direction and significance.

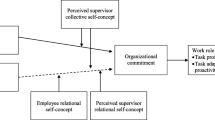

Table 2 depicts the results of Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4. Hypothesis 1 posited that LMX quality would mediate the relationship between CSE and work engagement. Utilizing the bootstrap confidence interval (CI), we found a significant indirect effect of CSE on work engagement through LMX quality indicated by CI [0.05, 0.16]. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Hypothesis 2 predicted that LMX quality would mediate the relationship between CSE and OCB. This hypothesis is supported based on the statistically significant bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effect: CI [0.03, 0.14]. Hypothesis 3 predicted an indirect effect of CSE on OCB through work engagement. This hypothesis is also supported, indicated by CI [0.04, 0.16]. Hypothesis 4 predicted that CSE would have an indirect effect on OCB through LMX quality and work engagement serially. The bootstrap confidence interval indicates support for this hypothesis (CI [0.01, 0.05]). Though not hypothesized, the coefficients for the direct relationships can be found in Fig. 1. We also ran these analyses without any control variables and the mediation effects for all our hypothesized relationships remained significant and did not change our results substantially. As such, we retained the results that included our specified control variables.

Discussion

While much research has been conducted on CSEs, researchers have noted that the understanding of the processes and intervening mechanisms through which CSEs promote workplace outcomes is underdeveloped (Chang et al., 2012). This study addresses this underdevelopment by investigating both situational appraisal and action mediators (i.e., LMX quality and work engagement) in the relationship between CSEs and OCBs. Our results provide evidence that the relationship between CSEs and OCBs is not so straightforward. Rather, it is through the development and appraisal of higher quality relationships with their leaders and being more fully engaged in their work that higher CSE individuals are more likely to be so invested in their work that they will go above and beyond to perform OCBs. These findings make several contributions.

First, in heeding Chang and colleagues’ (2012) call for more research into the indirect mechanisms by which CSE is related to work outcomes, our study examines both the subordinate’s perceptions of the quality of their relationship with their boss, as well as their level of work engagement. By grounding our investigation of the role of both LMX quality and work engagement in the approach-avoidance theoretical framework, we attain a more detailed understanding of how an individual’s traits influence their situational appraisals and their actions, which have critical consequences for the workplace. The results of our research and inclusion of these mediators replicate prior research which has examined work engagement as a mechanism in the CSE-performance relationship (Rich et al., 2010) and extend research by including LMX as a situational appraisal. A promising area for future research is the continued integration of situational appraisal and action mediators in examining the CSE—performance relationship.

Second, to explicate how individuals’ CSEs ultimately affect the workplace, we opted to examine two categories of mediators (situational appraisals and actions) in the form of LMX quality and workplace engagement. Given that higher CSE individuals (a) are more sensitive to positive stimuli and likely to form positive appraisals of their situation, and (b) believe they have greater control over their lives and can be more proactive in shaping their work environment (by seeking out social support at work to achieve their goals), it is no surprise that our results supported the positive relationship between CSEs and both LMX relationship quality and work engagement. Our findings suggest that it is through the appraisal and development of more advantageous relationships that high-CSE individuals can better facilitate both the job demands and job resources necessary to be effective in the workplace.

Recent research on CSEs has integrated the approach-avoidance theoretical lens to explain the link between personality and behavior (e.g., Debusscher et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2020). The results of this study contribute to that growing body of literature, suggesting that individuals may engage in OCBs because of dispositional characteristics, rather than the expectation of future reciprocity.

Finally, rather than focusing on outcome variables of CSEs which have received a disproportionate amount of attention such as job performance and job satisfaction (Chang et al., 2012), our study examines both work engagement and OCBs. The examination of CSEs’ relationship with both work engagement and OCBs extends our understanding of how individuals’ CSEs prompt more complete investment in their work and behaviors which extend beyond that which they are required to do. Notably, despite initial evidence of a direct positive relationship between CSEs and OCBs (Ferris et al., 2011), our findings suggest simply having higher CSEs is not enough to result in OCBs. Rather, it is through a higher quality relationship with one’s leader and enhanced work engagement that CSEs are more likely to result in the performance of OCBs in the workplace.

Though one’s CSE is likely to remain stable and consistent over time (i.e., trait-like), one’s LMX relationship quality, level of work engagement, and performance of OCBs are likely to vary over time. As such, it is likely that these constructs, and their relationship to one another, will vary in dynamic ways over time. To further bolster the contributions our study makes, we considered and tested two alternative models to examine other possible construct ordering and relationships. The first alternative model specified the following: CSEs→Work engagement→LMX→ OCBs. The second alternative model specified the following: CSEs→LMX→OCBs→Work engagement. We tested each of these model’s four indirect relationships with the same data and used the same techniques as we did for our study’s main model.

In the first alternative model, we found a significant indirect effect of CSE on LMX quality through work engagement indicated by CI [0.05,0.16], a significant indirect effect of CSEs on OCBs through LMX quality indicated by CI [0.01, 0.09], a significant indirect effect of CSEs on OCBs through work engagement indicated by CI [0.05, 0.20], and a significant indirect effect of CSEs on OCBs through work engagement and LMX quality serially indicated by CI [0.01, 0.06]. In the second alternative model, we found a significant indirect effect of CSEs on OCBs through LMX quality indicated by CI [0.05, 0.17], a significant indirect effect of CSEs on work engagement through LMX quality indicated by CI [0.04, 0.14], and a significant indirect relationship between CSEs and work engagement though LMX and OCBs serially indicated by CI [0.00, 0.03]. However, the results for the indirect relationship of CSE on work engagement through OCBs were non-significant indicated by CI [-0.01, 0.03].

These results show that it is possible that these constructs are likely to relate to one another in various dynamic ways over time. For instance, while our main study hypothesizes and finds support for LMX quality being positively related to work engagement, the results of our testing of alternative model one suggests it is possible that work engagement may also lead to higher LMX quality. Between the theorizing and analysis conducted in our main study, we are confident that our main model delivers the soundest results that most fully captures reality. These alterative models, however, provide a helpful point of reference that offer a more nuanced understanding of these constructs and their relation to one another, buttressing the theoretical contributions of this study. In addition to these theoretical contributions, our study’s findings have meaningful implications for managers.

Practical Implications

This study provides additional support for the notion that managers should continue to hire individuals with higher, rather than lower CSEs. However, this study also provides support for the idea that it is not enough to simply bring high-CSE individuals into the organization. In addition to hiring individuals with higher CSEs, managers need to engage with their subordinates to foster higher quality relationships with them. These higher quality relationships promote a more beneficial exchange of resources and need for reciprocity (Gouldner, 1960), resulting in a subordinate’s willingness to engage in both their work and ultimately OCBs. It is not enough to hire individuals with more positive beliefs in themselves and expect them to produce for the organization. These individuals must be given both the opportunities and resources necessary to prompt these beneficial behaviors.

To help employees achieve higher quality LMX relationships, managers might consider developing a more structured and intentional mentoring program. LMX has a demonstrated relationship with mentoring (Scandura & Schriesheim, 1994), and given its intervening role between employee CSEs and favorable work outcomes, it would be worthwhile for managers to dedicate resources to develop formalized mentoring programs. While we suspect high-CSE individuals would take the initiative to engage in, and ultimately benefit from, such a program, we suspect a more formalized program that assigns a mentor, dedicates time, sets clear expectations, etc. might be more advantageous to those with lower CSEs. The structure and support of such a program might help individuals who might be reticent to appraise or engage in relationship building with a leader, ultimately leading to positive outcomes for the individual and the organization.

While this responsibility to develop higher quality relationships with subordinates often falls on the leaders, it is also critical for the organization to support this process. Just the way leaders support subordinates in their work endeavors, so does the organization demonstrate support for its leaders. Erdogan and Enders (2007) found that supervisor’s perceived organizational support plays a critical role in the development of LMX relationships. More specifically, they found that higher levels of support from the organization afforded them more resources (favorable job conditions, Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002; performance rewards, Rhoades et al., 2001) which could be deployed in their exchanges with subordinates. It also promoted a greater sense of efficacy that their decisions and behaviors would be supported in their pursuit of higher quality relationships, ultimately motivating leaders to further develop these relationships. As such, organizations should support and empower managers as they pursue higher quality relationships with their subordinates.

Limitations and Future Research

This research has provided encouraging results that provide insight regarding the interplay of CSE, LMX, and outcomes at work. However, we do recognize several limitations of this study. First, our method of measurement of the variables of interest presents several challenges and opportunities for future research, including the sole reliance on surveys and their self-report nature. All our variables were measured from the same respondents, which raises concerns regarding their potential to introduce biases (Podsakoff et al., 2003) into our analysis. Consistent with Conway and Lance’s (2010) expectations regarding potential common method bias, we took steps to mitigate potentially biased results. Specifically, we selected previously validated scales and separated our collection temporally over three waves with 2-week intervals to minimize the possibility of compromising the validity of our results. We also conducted a common method variance assessment by employing a single-method-factor approach using a marker variable (MacKenzie et al., 1999) and found no evidence of common method bias affecting our results. Despite the efforts made to combat these potential issues, future research should employ leader-report and non-survey-based measures to provide further support to this study’s findings. Additionally, given that CSE is a trait and can be difficult to detect in an employment interview, our practical implications are limited.

Second, we did not measure study variables at all three time points and cannot make claims of causality between CSEs and OCBs. We join the calls of other scholars to incorporate longitudinal study designs to assess causality in these relationships. Third, our study did not include or test any potential contextual moderators which might impact the relationships under examination. Understanding the organizational context is critical because it can impact the range, base rates, or even direction of relationships in organizational studies (Johns, 2006). For instance, in their study of LMX quality comparisons, Tse and colleagues (2018) examined how a more procedurally just climate would impact the affective responses of employees making LMX comparisons. In a climate where justice was lacking, they found that when employees perceived their coworkers as having higher-quality LMX relationships than they had, they would experience higher levels of hostile emotions and even direct harmful behavior to the coworker who is perceived to have a better relationship. However, in a more procedurally just climate, the individual would experience fewer hostile emotions and was less likely to direct harmful behavior towards their coworker. As such, future research should consider the contextual influences which might affect the relationships examined in this study.

Finally, while we are confident in the effectiveness of our employment of the approach-avoidance framework, and other studies have done so in a similar manner (Chiang et al., 2014; Ding & Lin, 2020; Wang et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020), we did not directly measure it. Though we do not believe this limits its efficacy or explanatory power, future research should directly measure individual’s approach-avoidance orientation when utilizing it as the primary theoretical framework.

Conclusion

Because high-CSE individuals are more likely to engage in initiative-based behaviors designed to shape their environment to their advantage, it is crucial to garner a better understanding of how it is that they do so and how this relates to workplace outcomes. Throughout this paper, we examined specific processes and mechanisms through which CSEs operate. Specifically, we explicated how both the situational appraisal of the relationship an individual forms with their leader (i.e., LMX quality) and the action of workplace engagement serve as intervening mechanisms through which CSEs are related to OCBs. By providing enhanced clarity of the role LMX quality and work engagement play in that process, it is our hope that this study spurs continued empirical as well as theoretical examinations of CSEs in the workplace.

Notes

This data is available upon request from the first author.

References

Anand, S., Vidyarthi, P. R., Liden, R. C., & Rousseau, D. M. (2010). Good citizens in poor-quality relationships: Idiosyncratic deals as a substitute for relationship quality. Academy of Management Journal, 53, 970–988. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.54533176

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Avery, D. R., McKay, P. F., & Wilson, D. C. (2007). Engaging the aging workforce: The relationship between perceived age similarity, satisfaction with coworkers, and employee engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1542–1556. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1542

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Sanz-Vergel, A. I. (2014). Burnout and work engagement: The JD–R approach. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1, 389–411. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

Behrend, T. S., Sharek, D. J., Meade, A. W., & Wiebe, E. N. (2011). The viability of crowdsourcing for survey research. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 800–813. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0081-0

Bentler, P. M. (2007). On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Personality and Individual Differences, 42, 825–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.024

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Blau, P. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. Wiley.

Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2003). Core self-evaluations: A review of the trait and its role in job satisfaction and job performance. European Journal of Personality, 17, 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.481

Brown, D. J., Ferris, D. L., Heller, D., & Keeping, L. M. (2007). Antecedents and consequences of the frequency of upward and downward social comparisons at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 102, 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.10.003

Chang, C. H., Ferris, D. L., Johnson, R. E., Rosen, C. C., & Tan, J. A. (2012). Core self-evaluations: A review and evaluation of the literature. Journal of Management, 38, 81–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311419661

Cheung, J. H., Burns, D. K., Sinclair, R. R., & Sliter, M. (2017). Amazon Mechanical Turk in organizational psychology: An evaluation and practical recommendations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32, 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9458-5

Chen, C. C., & Chiu, S. F. (2009). The mediating role of job involvement in the relationship between job characteristics and organizational citizenship behavior. The Journal of Social Psychology, 149, 474–494. https://doi.org/10.3200/socp.149.4.474-494

Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2001). Validation of a new general self-efficacy scale. Organizational Research Methods, 4, 62–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/109442810141004

Chiang, Y. H., Hsu, C. C., & Hung, K. P. (2014). Core self-evaluation and workplace creativity. Journal of Business Research, 67, 1405–1413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.08.012

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64, 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x

Cogliser, C. C., Schriesheim, C. A., Scandura, T. A., & Gardner, W. L. (2009). Balance in leader and follower perceptions of leader–member exchange: Relationships with performance and work attitudes. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 452–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2009.03.010

Colbert, A. E., Mount, M. K., Harter, J. K., Witt, L. A., & Barrick, M. R. (2004). Interactive effects of personality and perceptions of the work situation on workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 599–609. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.4.599

Conger, J. A., Kanungo, R. N., & Menon, S. T. (2000). Charismatic leadership and follower effects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21, 747–767. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200011)21:7%3C747::aid-job46%3E3.0.co;2-j

Conway, J. M., & Lance, C. E. (2010). What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25, 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010-9181-6

Cropanzano, R., & Mitchell, M. S. (2005). Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. Journal of Management, 31, 874–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206305279602

Debusscher, J., Hofmans, J., & De Fruyt, F. (2016). The effect of state core self-evaluations on task performance, organizational citizenship behaviour, and counterproductive work behaviour. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25, 301–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2015.1063486

Ding, H., & Lin, X. (2020). Exploring the relationship between core self-evaluation and strengths use: The perspective of emotion. Personality and Individual Differences, 157, 109804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109804

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38, 1715–1759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311415280

Elliot, A. J., & Thrash, T. M. (2002). Approach-avoidance motivation in personality: Approach and avoidance temperaments and goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 804–818. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.5.804

Epitropaki, O., & Martin, R. (2005). From ideal to real: A longitudinal study of the role of implicit leadership theories on leader-member exchanges and employee outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 659–676. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.659

Erdogan, B., & Enders, J. (2007). Support from the top: Supervisors’ perceived organizational support as a moderator of leader-member exchange to satisfaction and performance relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.321

Erez, A., & Judge, T. A. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations to goal setting, motivation, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 1270–1279. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1270

Eysenck, H. J. (1990). Genetic and environmental contributions to individual differences: The three major dimensions of personality. Journal of Personality, 58, 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00915.x

Ferris, D. L., Rosen, C. R., Johnson, R. E., Brown, D. J., Risavy, S. D., & Heller, D. (2011). Approach or avoidance (or both?): Integrating core self-evaluations within an approach/avoidance framework. Personnel Psychology, 64, 137–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01204.x

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18, 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Fredrickson, B. L., & Losada, M. F. (2005). Positive affect and the complex dynamics of human flourishing. American Psychologist, 60, 678–686. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.60.7.678

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26, 331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322

Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1997). Meta-Analytic review of leader–member exchange theory: Correlates and construct issues. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 827–844. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.82.6.827

Gouldner, A. W. (1960). The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2092623

Graen, G. B., & Scandura, T. A. (1987). Toward a psychology of dyadic organizing. Research in Organizational Behavior, 9, 175–208.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Relationship-based approach to leadership: Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6, 219–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(95)90036-5

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. Addison-Wesley.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Babin, B. J., & Black, W. C. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. Prentice Hall.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76, 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360

Hayes, A. F. (2018). The PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS (version 3.0).

Haynie, J. J., Flynn, C. B., & Mauldin, S. (2017). Proactive personality, core self-evaluations, and engagement: The role of negative emotions. Management Decision, 55, 450–463. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-07-2016-0464

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.3.4.424

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hui, C., Lee, C., & Rousseau, D. M. (2004). Employment relationships in China: Do workers relate to the organization or to people? Organization Science, 15, 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1030.0050

Ilies, R., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Leader-member exchange and citizenship behaviors: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 269–277. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.269

Janssen, O., & Van Yperen, N. W. (2004). Employees’ goal orientations, the quality of leader-member exchange, and the outcomes of job performance and job satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 47, 368–384. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159587

Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31, 386–408. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.20208687

Joo, B. K., & Jo, S. J. (2017). The effects of perceived authentic leadership and core self-evaluations on organizational citizenship behavior: The role of psychological empowerment as a partial mediator. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 38, 563–481. https://doi.org/10.1108/lodj-11-2015-0254

Joo, B. K. B., Yoon, H. J., & Jeung, C. W. (2012). The effects of core self-evaluations and transformational leadership on organizational commitment. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 33, 564–582. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437731211253028

Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.80

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., & Locke, E. A. (2000). Personality and job satisfaction: The mediating role of job characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.2.237

Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2003). The core self-evaluations scale: Development of a measure. Personnel Psychology, 56, 303–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2003.tb00152.x

Judge, T. A., & Hurst, C. (2007). The benefits and possible costs of positive core self-evaluations: A review and agenda for future research. In D. L. Nelson & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Positive organizational behavior, 159–174. London, UK: Sage10.4135/9781446212752.n12

Judge, T. A., Locke, E. A., & Durham, C. C. (1997). The dispositional causes of job satisfaction: A core evaluations approach. Research in Organizational Behavior, 19, 151–188.

Judge, T. A., Locke, E. A., Durham, C. C., & Kluger, A. N. (1998). Dispositional effects on job and life satisfaction: The role of core evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.1.17

Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., Judge, T. A., & Scott, B. A. (2009). The role of core self-evaluations in the coping process. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013214

Kim, M., & Beehr, T. A. (2020). Job crafting mediates how empowering leadership and employees’ core self-evaluations predict favourable and unfavourable outcomes. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29, 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432x.2019.1697237

Laschinger, H. K. S., Purdy, N., & Almost, J. (2007). The impact of leader-member exchange quality, empowerment, and core self-evaluation on nurse manager’s job satisfaction. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 37, 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.nna.0000269746.63007.08

Lee, F. K., Dougherty, T. W., & Turban, D. B. (2000). The role of personality and work values in mentoring programs. Review of Business, 21, 33–37. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976619.n2

Lee, J., & Ok, C. M. (2016). Hotel employee work engagement and its consequences. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 25, 133–16610. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2014.994154

Li, N., Liang, J., & Crant, J. M. (2010). The role of proactive personality in job satisfaction and organizational citizenship behavior: A relational perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 395–404. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018079

Liden, R. C., & Maslyn, J. M. (1998). Multidimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. Journal of Management, 24, 43–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0149-2063(99)80053-1

MacKenzie, S. B., Podsakoff, P. M., & Paine, J. B. (1999). Do citizenship behaviors matter more for managers than for salespeople? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27, 396–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070399274001

Martin, R., Guillaume, Y., Thomas, G., Lee, A., & Epitropaki, O. (2016). Leader–member exchange (LMX) and performance: A meta-analytic review. Personnel Psychology, 69, 67–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12100

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (2008). Early predictors of job burnout and engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.3.498

Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., & Ruokolainen, M. (2007). Job demands and resources as antecedents of work engagement: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70, 149–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.09.002

Meade, A. W., & Craig, S. B. (2012). Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychological Methods, 17, 437–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028085

Organ, D. W. (1988). Organizational citizenship behavior: The good soldier syndrome. Lexington Books.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 698–714. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

Rhoades, L., Eisenberger, R., & Armeli, S. (2001). Affective commitment to the organization: The contribution of perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.825

Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53, 617–635. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.51468988

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976

Scandura, T. A., & Meuser, J. D. (2021). Relational Dynamics of Leadership: Problems and Prospects. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012420-091249

Scandura, T. A., & Schriesheim, C. A. (1994). Leader-member exchange and supervisor career mentoring as complementary constructs in leadership research. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1588–1602. https://doi.org/10.5465/256800

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66, 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015630930326

Sears, G. J., & Hackett, R. D. (2011). The influence of role definition and affect in LMX: A process perspective on the personality–LMX relationship. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84, 544–564. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317910x492081

Shuck, B., Reio, T. G., Jr., & Rocco, T. S. (2011). Employee engagement: An examination of antecedent and outcome variables. Human Resource Development International, 14, 427–44510. https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2011.601587

Simmering, M. J., Fuller, C. M., Richardson, H. A., Ocal, Y., & Atinc, G. M. (2015). Marker variable choice, reporting, and interpretation in the detection of common method variance: A review and demonstration. Organizational Research Methods, 18, 473–511. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428114560023

Spanouli, A., & Hofmans, J. (2021). A resource-based perspective on organizational citizenship and counterproductive work behavior: The role of vitality and core self-evaluations. Applied Psychology, 70, 1435–1462. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12281

Srivastava, A., Locke, E. A., Judge, T. A., & Adams, J. W. (2010). Core self-evaluations as causes of satisfaction: The mediating role of seeking task complexity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77, 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2010.04.008

Tse, H. H., Lam, C. K., Gu, J., & Lin, X. S. (2018). Examining the interpersonal process and consequence of leader–member exchange comparison: The role of procedural justice climate. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39, 922–940. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2268

Walumbwa, F. O., Cropanzano, R., & Goldman, B. M. (2011). How leader-member exchange influences effective work behaviors: Social exchange and internal-external efficacy perspectives. Personnel Psychology, 64, 739–770. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2011.01224.x

Wang, Z., Bu, X., & Cai, S. (2021). Core self-evaluation, individual intellectual capital and employee creativity. Current Psychology, 40, 1203–1217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0046-x

Wayne, S. J., Shore, L. M., Bommer, W. H., & Tetrick, L. E. (2002). The role of fair treatment and rewards in perceptions of organizational support and leader-member exchange. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 590–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.590

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17, 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700305

Williams, L. J., Hartman, N., & Cavazotte, F. (2010). Method variance and marker variables: A review and comprehensive CFA marker technique. Organizational Research Methods, 13, 477–514. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110366036

Zhang, Y., Sun, J. M. J., Lin, C. H. V., & Ren, H. (2020). Linking core self-evaluation to creativity: The roles of knowledge sharing and work meaningfulness. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35, 257–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9609-y