Abstract

To examine a) the feasibility of delivering a summer treatment program for pre-kindergarteners (STP-PreK) with externalizing behavior problems (EBP) and b) the extent to which the STP-PreK was effective in improving children’s school readiness outcomes. Participants for this study included 30 preschool children (77 % boys; Mean age = 5.33 years; 77 % Hispanic background) with at-risk or clinically elevated levels of EBP. The STP-PreK was held at an early education center and ran for 8-weeks (M-F, 8 a.m.–5 p.m.) during the summer between preschool and kindergarten. In addition to a behavioral modification system and comprehensive school readiness curriculum, a social-emotional curriculum was also embedded within the STP-PreK to target children’s self-regulation skills (SR). Children’s pre- and post-school readiness outcomes included a standardized school readiness assessment as well as parental report of EBP, adaptive functioning, and overall readiness for kindergarten. SR skills were measured via a standardized executive functioning task, two frustration tasks, and parental report of children’s emotion regulation, and executive functioning. The STP-PreK was well received by parents as evidenced by high attendance and satisfaction ratings. Additionally, all school readiness outcomes (both parent and observational tasks) significantly improved after the intervention (Cohen’s d effect sizes ranged from 0.47 to 2.22) with all effects, except parental report of emotion regulation, being maintained at a 6-month follow-up. These findings highlight the feasibility and utility of delivering an early intervention summer program that can successfully target multiple aspects of children’s school readiness, including behavioral, social-emotional/self-regulation, and academics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Recent research has emphasized that children’s early externalizing behavior problems (EBP), including aggression, defiance, inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity, have significant implications for children’s school readiness and their subsequent transitions into the early school years (Webster‐Stratton et al. 2008; McClelland et al. 2006; Denham 2006). Although early conceptualizations of school readiness focused on emergent literacy and academic skills (Snow et al. 1998; Whitehurst and Lonigan 1998), more recent attention has centered on the emergence of children’s self-regulation skills as they relate to the ability to control behavior, attention, and emotions for the purpose of learning (Bierman et al. 2008; Blair 2002; McClelland et al. 2000). Moreover, research has demonstrated that a significant subset of preschoolers do not possess adequate self-regulation skills necessary for a successful transition to kindergarten (West et al. 2001). Deficits in self-regulation skills are even more pronounced in the 18 to 34 % of preschoolers who display at-risk or clinically elevated levels of EBP as reported by preschool teachers (Kupersmidt et al. 2000; Nolan et al. 2001; Upshur et al. 2009). Hence, preschoolers exhibiting significant disruptive behavior problems that reflect, or are the result of, self-regulation difficulties, are an optimal at-risk population for early intervention prior to the start of kindergarten.

Role of Self-regulation Skills in School Readiness and the Transition to Kindergarten

As outlined by Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta’s (2000) Ecological and Dynamic Model of Transition, the kindergarten environment is markedly different from that of preschool, such that in kindergarten, children must adapt to an ecological system that expects them to accomplish numerous academic and social goals under decreased supervision due to increased class size and increased emphasis on autonomy (Bronson et al. 1995). The novel demands of kindergarten, in combination with a decrease in support offered in preschool, require children to use their self-regulation skills to control their attention, behavior, and emotions (Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta 2000). These demands present a challenge for many young children. For example, a large national survey found that up to 46 % of kindergarten teachers indicated that half of their class or more had difficulties with self-regulatory skills (e.g., following directions, staying on task, paying attention) and were not emotionally and socially competent to function productively and learn (West et al. 2001). Consequently, it is not surprising that a significant body of literature has documented the importance of children’s self-regulation skills as it relates to school readiness and subsequent academic success (Bierman et al. 2008; Blair 2002).

Self-regulation is a multi-level construct with control efforts that include the use of physiological, attentional, executive, emotional, and behavioral processes (Vohs and Baumeister 2004; Calkins 2007). Individual differences in self-regulation skills are well documented and have been implicated in children’s adaptive and educational functioning (Graziano et al. 2007; McClelland et al. 2007; Pennington and Ozonoff 1996). A recent review by Ursache et al. (2012) identified two measures of self-regulation as particularly relevant for studying school readiness: executive functioning (EF) and emotion regulation (ER). These cognitive and emotional aspects of self-regulation are interrelated, overlapping at the neuroanatomical level (e.g., prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortices; Bush et al. 2000). Poor ER also physiologically inhibits a child’s use of EF processes that are important for attending to and retaining information presented by the classroom teacher (Blair 2002). Indeed, both EF and ER uniquely predict school readiness outcomes: Individual differences in EF have been shown to be concurrently and longitudinally related to children’s math and literacy scores in preschool, kindergarten, and first grade (Blair and Razza 2007; Clark et al. 2010; Espy et al. 2004; McClelland et al. 2007; Welsh et al. 2010). Kindergarteners’ ER skills have also been found to be associated with performance on both classroom assignments and standardized achievement tests, even after controlling for IQ (Graziano et al. 2007).

In addition to directly affecting cognitive processing, ER deficits may indirectly impact academic success via behavioral difficulties, such that children with EBP are more likely to experience both co-occurring (Al Otaiba and Fuchs 2002; Malecki and Elliot 2002) and later academic difficulties (Masten et al. 2005; Risi et al. 2003). Failure to regulate behavior negatively impacts the student’s ability to attend to information presented by teachers and complete tasks that foster learning (Kuhl and Kraska 1989). Children with ER difficulties and behavioral problems are also more likely to have a negative relationship with their teachers (Graziano et al. 2007; Pianta et al. 1995) as teachers have low tolerance for behavior problems (Arbeau and Coplan 2007; Safran and Safran 1984).

Importance of Intervening Prior to Kindergarten

The strong associations between children’s EF/ER skills and school success underscore the value in improving self-regulation skills. Intervening at the level of preschool, particularly with children identified as being at high-risk for the development of behavioral disorders, is of particular importance given that preschoolers with behavioral difficulties exhibit poorer self-regulation skills across executive/attentional (i.e., executive functioning), behavioral (i.e., impulse control), and emotional (i.e., emotion regulation) domains (Barkley 2010; Calkins 2007; Campbell 2002). In addition to preventing the escalation of these behavioral problems, initiating treatment prior to the start of kindergarten may provide increased benefit by reducing the public costs associated with special education. Specifically, two-thirds of preschoolers with elevated behavior problems go on to receive a mental health diagnosis of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) or another disruptive disorder by age nine, and receive later special education services (Campbell and Ewing 1990; Redden et al. 2003).

The incremental annual cost of providing special education services to children with ADHD in the U.S. has been estimated to be $4,900 per child or between $15 and 22 billion annually (Pelham et al. 2007). Even more significant is that once a child enters special education, they are unlikely to stop receiving such services, despite later interventions, with declassification rates from the OHI and EBD categories ranging from only 5 to 12 % (Halqren and Clarizio 1992; SEELS 2005). These overwhelming figures point to the tremendous cost-saving benefits that may arise from intervening prior to the start of kindergarten to prevent or delay placement in special education. Lastly, an unsuccessful transition to kindergarten may result in increased rates of removal, retention in kindergarten, and below grade level academic performance (Jimerson et al. 1997), thus further increasing costs through acquisition of additional behavioral, emotional, and academic public services.

Early Interventions that Target Socio-emotional and Behavioral Difficulties

A number of existing early intervention programs attempt to improve school readiness and increase academic success by targeting the social-emotional competency of preschool and young children at-risk for developing behavior disorders. Notably, these interventions include The Incredible Years (Webster‐Stratton et al. 2008), Project Star (Kaminski and Stormshak 2007), Promoting Alternative Thinking Skills (PATHS; Greenberg et al. 1995), Early Risers’ “Skills for Success” Program (August et al. 2007), and First Step to Success (Walker et al. 1998). However, none of these programs, despite strong empirical support, have been designed to target multiple aspects of school readiness (e.g., they focus mostly on social-emotional skills) or provide services during the summer transition to kindergarten. Intervening during the summer months is critical not only because children at-risk are already experiencing behavioral problems but also because they typically receive no services during this time. Summer learning losses (e.g., 1 month’s worth) have been well documented in the literature (e.g., Cooper et al. 2000), and further highlight the necessity of providing treatment in this time frame.

Although based in the school-year, it is worth mentioning the contribution of three innovative preschool programs that have attempted to measure and/or remediate children’s self-regulation skills: the Research-Based Developmentally Informed (REDI) Head Start innovation (Bierman et al. 2008), the Chicago School Readiness Project (CSRP; Raver et al. 2009); and the Tools of the Mind Curriculum (Bodrova and Leong 2007). The REDI includes a preschool version of the PATHS curriculum emphasizing socio-emotional functioning along with enhanced language/literacy instruction, the CSRP targets teacher training and improving the emotional climate of the classroom, and the Tools of the Mind curriculum promotes EF development via various scaffolding learning and sociodramatic play activities. Improvements in self-regulation skills have been observed in the REDI and CSRP studies and partially mediate the intervention’s effects on emergent literacy skills (Bierman et al. 2008) and math skills (Raver et al. 2011). The Tools of the Mind curriculum increases children’s EF, yet does not appear to predict improvements in academic performance (Diamond et al. 2007). Taken together, these studies indicate the potential for early intervention school-based programs to enhance children’s self-regulation skills and subsequent kindergarten readiness. However, it is important to point out that these three curriculums do not specifically target children with EBP. Hence, it remains unclear a) the feasibility of conducting a large-group socio-emotional/behavioral intervention with preschoolers with EBP during the summer transition to kindergarten and b) whether children with EBP’s self-regulation skills improve within a classroom-wide intervention.

Goals of the Current Study

The first goal of this study was to examine the feasibility and utility of delivering an 8-week intervention during the transition from preschool to kindergarten (i.e., Summer Treatment Program for Pre-Kindergarteners, STP-PreK) for children with EBP. The STP-PreK is a full-day (8:00 am–5:00 pm) program that simulates a kindergarten environment (e.g., periods of independent seatwork, whole- and small-group reading, math, and science activities, and classroom meetings), as well as recreational activities (sports, art, group games). In addition to a behavior modification system adapted from the evidence-based system used in the Children’s Summer Treatment Program Academic Learning Centers (Pelham et al. 2010), the STP-PreK incorporates a comprehensive preschool curriculum focused on literacy (Literacy Express; Lonigan et al. 2005) and social-emotional and self-regulation activities designed to improve children’s social skills, emotional understanding, coping skills, and EF (see “Method” section for details of the intervention). We hypothesized that the STP-PreK would be feasible to implement and acceptable to families as evidenced by high rates of attendance, treatment fidelity, family engagement, and satisfaction. The second goal of this study was to obtain preliminary evidence on whether the STP-PreK was effective in improving preschoolers’ kindergarten readiness outcomes. Using an open trial format, we hypothesized that children who participated in the STP-PreK would significantly improve their school readiness as evidenced by higher academic performance, decreased EBP, higher adaptive functioning skills, and higher overall readiness for kindergarten. Lastly, we hypothesized that children who participated in the STP-PreK would improve their self-regulation skills as indexed by ER and EF.

Method

Participants and Recruitment

The study took place in a large urban southeastern city in the U.S. with a large Hispanic population. Children and their caregivers were recruited from local preschool and mental health agencies via brochures, radio and newspaper ads, and open houses/parent workshops. Interested parents were asked to call or speak with study staff to have the study explained to them and schedule a screening appointment to determine eligibility. Forty-three families scheduled a screening appointment. Once parents arrived at the screening appointment, study staff informed parents of the purpose and requirements of the study and went over the consent form explaining the assessment procedures and intervention protocol as well as answered any questions by the parents. The primary caregiver provided written consent prior to the start of the initial screening assessment. To qualify for the study participants were required to (a) have an externalizing problems composite t-score of 60 or above on the parent (M = 67.8, SD = 12.15) or teacher (M = 65.6, SD = 15.49) BASC-2 (Reynolds and Kamphaus 2004) collected as part of our initial assessment, (b) be enrolled in preschool during the previous year, (c) have an estimated IQ of 65 or higher (M = 94.13), (d) have no confirmed history of Autistic or Psychotic Disorder, and (e) be able to attend a daily 8-week summer program prior to the start of kindergarten (all but three children in our sample transitioned to kindergarten). Thirteen children were excluded from this study due to: not completing the screening process (n = 8), having a significant developmental delay (n = 2), caregiver not being able to drive child to camp for the 8 weeks (n = 2), or not having significant behavior problems as measured via the BASC-2 (n = 1).

The final participating sample consisted of 30 preschool children (77 % boys) with at-risk or clinically elevated levels of EBP whose parents provided consent to participate in the study. Study questionnaires were filled out primarily by mothers (80 %). The mean age of the participating children was 5.19 years (range 4.08 to 5.78 years, SD = 5.76 months) with Hollingshead SES scores in the lower to middle class range (M = 46.00, SD = 10.05). In terms of the ethnicity and racial makeup, 77 % of the children were Hispanic-White, 13 % were Non-Hispanic White, 3 % African-American, and the remaining 7 % biracial. Sixty-seven percent of children were from an intact biological family, 27 % were from a single biological parent household, and 6 % were in an adoptive/foster family placement. Fifty percent of the sample were self-referred, 26.7 % were referred by preschools, while the remaining 23.3 % were referred by a mental health professional or physician. Children came from 26 different preschools with no child sharing the same teacher.

According to the C-DISC (Shaffer et al. 2000), which was conducted by mental health graduate students under the supervision of a licensed psychologist, 50 % percent of children met DSM-IV criteria for both Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) while an additional 33 % met criteria for only ADHD. Of note, while the C-DISC was originally developed for assessing children 6 years of age and older, several studies have documented the reliability and validity of the C-DISC among children as young as four, in particular diagnosing disruptive behavior disorders (Lahey et al. 2005; Luby et al. 2002). In terms of non-DBD diagnoses, three children had a prior diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified. None of the children were on any psychotropic or non-psychotropic medication.

Study Design and Procedure

This study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. An open trial design was used to determine the feasibility of the STP-PreK as well as to obtain preliminary evidence for its efficacy in improving preschoolers with EBP’s school readiness outcomes. All families participated in a pre-treatment assessment scheduled prior to the start of the summer treatment program and a post-treatment assessment scheduled 1 to 2 weeks after the intervention ended. Twenty four out of the 30 families completed a follow-up assessment approximately 6 months after the intervention ended (five of the families could not be contacted despite multiple efforts while one family declined to participate due to transportation difficulties). Other than receiving the intervention at a subsidized cost via a local grant (The Children’s Trust), families did not receive any compensation for completing the assessments. At all three assessments, mothers brought their children to the laboratory and were videotaped during several tasks. The order of the tasks were standardized and children were given small breaks at the end of each task to ensure that there were no carry over effects from one task to another. The first task was an EF task (Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders; Ponitz et al. 2008) followed by two tasks from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (LAB-TAB; Goldsmith and Rothbart 1996) designed to elicit frustration. These frustration tasks described in the measures section are considered appropriate for use with young children and are typically used to assess individual differences in children’s ER skills (Calkins et al. 2007; Majdandžić and Van Den Boom 2007; Graziano et al. 2011; Zimmerman and Stansbury 2003).

While in the laboratory, mothers completed various questionnaires and participated in a structured interview (C-DISC; Shaffer et al. 2000). In a separate clinic visit, clinicians administered the Block Design and Vocabulary subtests from the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence—Third Edition (WPPSI-III; Wechsler 2002) as a screener measure of children’s overall intelligence. These two subtests are useful for rapid screening and have been shown to be reliable in estimating children’s full scale IQ (Sattler and Dumont 2004). Children were also administered the Bracken School Readiness Assessment (Bracken 2002).

Intervention Description

Children participated in the STP-PreK for 8 weeks from mid-June to mid-August 2012, Monday–Friday from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. All parents/caregivers also attended a once weekly parent training session for 8 weeks during the STP-PreK. Fifteen children were assigned to each classroom and each classroom was staffed by one lead teacher/developmental specialist and five developmental aides, yielding a 1:3 ratio of staff to students. The lead teachers were an advanced clinical psychology graduate student and a certified elementary school teacher. The developmental aides were comprised of undergraduate and post-baccalaureate paraprofessionals. All staff underwent an extensive 10-day training in behavior modification for child behavior problems and demonstrated mastery of the STP-PreK manual, scoring at least 80 % on a procedural test. Clinicians were supervised daily by the first author, a doctoral-level licensed clinical psychologist with over 10 years of experience implementing interventions with children with disruptive behavior disorders. Below, we briefly describe the behavioral modification program, academic enrichment curriculum, and social-emotional/self-regulation curriculum of the STP-PreK. The specifics for each component of the STP-PreK are detailed in a manual available from the authors.

Behavioral Modification Program

The behavior modification program used in the classroom was modeled after the evidence-based system used in the STP-Elementary Academic Learning Centers (Fabiano et al. 2007; Pelham et al. 2010). The behavior management system used in the learning centers allows for development of children’s abilities to follow through with instructions, complete tasks accurately, comply with teacher requests, and interact cooperatively and positively with peers—all areas in which children with challenging behaviors typically display difficulty. A visual response cost-system was implemented in which children began each academic period with ten green dots; a dot was removed for violating one of seven posted classroom rules (i.e., Be respectful, follow directions, work quietly, use materials and possessions appropriately, remain seated, raise your hand to speak, and stay on task). More serious violations (e.g., aggression) resulted in an automatic time out from positive reinforcement along with associated dot losses. Group contingencies such as a “no time out race” were also implemented in which children earned extra dots for staying out of time out. Children were able to exchange their dots in the “dot store” for daily classroom rewards and privileges such as twice-daily recess. Parents were also provided daily written feedback about children’s behavior and academic progress in the form of a daily report card (DRC) on their child’s progress and were instructed on how to provide daily, home, DRC-contingent rewards.

Academic Enrichment Curriculum

The academic curriculum developed for the STP-PreK was developed to reinforce state standards for reading, English/language arts, math, and science for entering kindergarteners, as well as reflect a literacy and numeracy rich environment that will help the child develop in the four main areas development—social/emotional, physical, cognitive, and language. Specifically, we implemented portions of the Literacy Express Preschool Curriculum, an evidence-based preschool curriculum (Lonigan et al. 2005), by having every week in our camp follow a Literacy Express theme. During the week of Under the Sea, for example, all of the academic activities, centers, vocabulary of the week, seatwork, as well as homework were related to the Literacy Express theme and suggested activities. Children also participated in daily small-group dialogic reading, print knowledge, and phonological awareness activities to build literacy skills.

Social-emotional/Self-regulation Curriculum

Children engaged in daily social skills and emotional awareness training via the use of puppets, in-vivo training, and reinforcement of the skills throughout the day. Four main social skills were targeted including participation, communication, cooperation, and encouragement. Additionally, eight emotional states were targeted including happy, sad, mad, scared, surprised, disgusted, embarrassed, and guilty. Children also learned how to cope with these various emotional states, most notably the negative emotions, via the Turtle Shell Technique (Schneider 1974). Lastly, children participated in a daily 30-min self-regulation period in which they engaged in various executive functioning games (e.g., Red Light/Green Light, Orchestra) adapted from a series of circle time games shown to improve preschoolers’ self-regulation (Tominey and McClelland 2011).

Parent Training

Parents were also required to attend a School Readiness Parenting Program (SRPP; Graziano et al. 2013) that was conducted weekly lasting between 1.5 and 2 h. The first half of each SRPP session involved traditional aspects of behavioral management strategies (e.g., improving parent–child relationship, discipline strategies such as time out) delivered to the entire group via a Community Parent Education Program (COPE; Cunningham et al. 1998) style modeling problem solving approach in which other parents contributed to the didactic discussion. The behavioral management content was based on Parent–child Interaction Therapy with four sessions focused on child-directed skills (e.g., labeled praise, description, reflection, enthusiasm) during “special time” while another four sessions focused on parent-direct skills (e.g., effective commands, time out). Subgroup activities entailed parents practicing the newly acquired skills with their own children while the other parents in the subgroup observed and provided positive feedback. During the second half of each SRPP session, parents participated in group discussions on several school readiness topics including: how to appropriately manage behavior problems during homework time and in public settings, how to promote early literacy and math skills, how to implement a home-school communication plan with teachers (i.e., DRC), and how to prepare their child for kindergarten.

Measures of Feasibility and Acceptability

Treatment Fidelity

The STP-PreK was videotaped biweekly with research assistants trained to watch and code sessions using a standard treatment fidelity checklist. A doctoral level licensed psychologist completed a treatment fidelity checklist on a weekly basis for each classroom to provide supervision to counselors implementing the STP-PreK.

Attendance

Attendance for each camp session was measured from counselors’ contact notes and sign-in sheets completed by parents during drop-off and pick up.

Treatment Satisfaction

Parents provided ratings of treatment satisfaction for the summer camp portion at post-treatment by answering a standard satisfaction questionnaire developed for behavioral treatments (MTA Cooperative Group 1999) that was adapted for the STP-PreK. Parents indicated their degree of satisfaction across a five-point Likert scale how much they and their child benefited, whether they would recommend the program to other parents, as well as how effective the program was compared to other treatment services they had received. The mean level of satisfaction was calculated across the seven items. Parents also provided ratings of treatment satisfaction for the parent training portion of the STP-PreK by completing the Therapy Attitude Inventory (TAI; Brestan et al. 1999).

Improvement

A pre-kindergarten adaptation of the Improvement Rating Scale (Pelham et al. 2000) was used to measure improvement during the STP-PreK. The parent version consisted of 40 items and the counselor version consisted of 56 items. Both parents and counselors were asked to indicate the target child’s degree of improvement on each item using a 7-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (very much worse) to 4 (unchanged) to 7 (very much improved). Of interest to the current study were four summary items indicating overall a) behavioral improvement, b) attentional improvement, c) social-emotional improvement, and d) academic improvement. Parent and counselor’s ratings were averaged for each domain.

Measures of School Readiness

Academic Functioning

Children were individually administered the Bracken School Readiness Assessment (BSRA; Bracken 2002), a widely used kindergarten readiness test which consists of five subtests assessing children’s receptive knowledge of colors, letters, numbers/counting, size/comparison, and shapes. The BSRA has strong psychometric properties and has been validated as a strong predictor of children’s academic outcomes (Bracken 2002; Panter and Bracken 2009). For the purposes of this study, the overall school readiness composite raw score was used. Parents were also asked to complete the Kindergarten Behavior and Academic Competency Scale (KBACS; Hart and Graziano 2013), a 23-item questionnaire that requires parents and teachers to rate the extent to which their child is ready for kindergarten across various domains (e.g., following classroom rules, completing academic work) along a five-point scale (poor, fair, average, above average, excellent). Of interest to the current study is the overall kindergarten readiness question in which parents rate, on a scale of 1 to 100, how ready they feel their child is in meeting the academic and behavioral demands of kindergarten compared to other same-age children. Higher scores indicate greater level of kindergarten readiness. The KBACS overall score (α’s = 0.74–0.98) was used as a measure of kindergarten readiness.

Externalizing Behavior Problems and Adaptive Functioning Skills

To assess children’s behavioral and adaptive functioning, parents completed the Behavior Assessment System for Children, 2nd Edition (BASC-2; Reynolds and Kamphaus 2004). The BASC-2 is a widely used behavior checklist that taps emotional and behavioral domains of children’s functioning. The preschool version (ages 2–5) contains 134 items while the child version (ages 6–11) contains 160 items rated on a four-point scale with respect to the frequency of occurrence (never, sometimes, often, and almost always). The measure yields scores on broad internalizing, externalizing, and behavior symptom domains as well as specific adaptive/social functioning skills scales. The BASC-2 has well-established internal consistency, reliability and validity (Reynolds and Kamphaus 2004). For the purposes of this study and due to the different age versions of the BASC-2, the externalizing and adaptive functioning composite t-scores were used (α’s = 0.65–0.80).

Executive Functioning-Standardized Assessment

Children were administered the Head-Toes-Knees-Shoulders task (HTKS; Ponitz et al. 2008). The HTKS is a widely-used task used with preschoolers to assess multiple aspects of executive functioning. In this task children are initially given two paired behavioral rules (e.g., “touch your head” and “touch your toes”) in which they naturally respond to and habituate. Next, children are instructed to switch and respond in a different or opposite way (e.g., if the administrator said, “Touch your toes,” the correct response would be for the child to touch their head) across ten test trials. The task then switches again back to a habituation of two other verbal commands (e.g., “touch your knees” and “touch your shoulders”) followed by ten more test trials in which the children are required to combine both set of rules with a possibility of four different responses. Children score two points for a correct response, zero points for an incorrect response, and one point if any motion to the incorrect response is made but self-corrected and ended with the correct action. Scores ranged from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicative of better EF.

Executive Functioning-Parent Report

Parents also filled out the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Preschool Version (BRIEF-P; Gioia et al. 2003). The parent preschool version contains 63 items rated on a three point Likert scale (“never,” “sometimes,” and “often”), which yield five nonoverlapping but correlated clinical scales (inhibit, shift, emotional control, working memory, and plan-organize) and two validity scales. Scores in these clinical scales are also summed to create composite indices of inhibitory self-control index (inhibit + emotional control), flexibility index (shift + emotional control), emergent metacognition index (working memory + plan/organize), and an overall global executive composite. Higher scores indicate poorer executive functioning. The BRIEF-P has well-established internal consistency, reliability and validity (Isquith et al. 2005; Mahone and Hoffman 2007). For the purpose of the present study, the emergent metacognition index raw score (α’s = 0.77-0.79) was used as our parent measure of executive functioning.

Emotional Functioning-Standardized Assessment

Children participated in two frustration tasks from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (LAB-TAB; Goldsmith and Rothbart 1996) designed to elicit emotional distress and regulation. In the first frustration task (not sharing; 4 min), an assistant brings a bag of candy and asks the experimenter to share it equally with the child. The experimenter begins equally dividing the candy with the child but then slowly starts to give more to him/herself, eating some of the child’s candy, and slowly taking all the candy away from the child while preventing the child from eating any of it. In the second frustration task (impossibly perfect green circles; 3.5 min), children are asked to draw circles repeatedly. After each drawing attempt, the experimenter points out some minor flaw (e.g., too pointy) and asks the child to draw another circle. The tasks were ended early if the child was highly distressed/cried hard for more than 30 s. Regulation was defined as the overall effectiveness of using various strategies (e.g., distraction). A global measure of regulation was coded on a scale from 0 (dysregulated or no control of distress) to 4 (the child seemed to completely regulate their distress during most of the task). Additionally, the proportion of time in seconds the child displayed distress was also coded. Past research that has used these frustration tasks have shown adequate coder reliability (Calkins et al. 2007; Graziano et al. 2011; Zimmerman and Stansbury 2003). The reliability Kappas for global codes for the present study were all above 0.80 while the correlation for the proportion of distress displayed among coders was also high across both tasks (r’s = 0.94 and 0.99, p < 0.001). To reduce the number of analyses, the global regulation and proportion of distress codes were averaged across tasks to produce a separate mean score for each.

Emotional Functioning-Parent Report

To assess children’s emotion regulation, parents completed the Emotion Regulation Checklist (ER Checklist; Shields and Cicchetti 1997). The ER Checklist is a 23-item questionnaire that uses a 4-point Likert scale (1 = almost always to 4 = never) and yields two subscales: the Negativity/Lability scale (15 items), which represents negative affect/mood lability, and the Emotion Regulation scale (eight items), which assesses processes central to adaptive regulation. For the present study, the Emotion Regulation scale (α’s = 0.77–0.79) of the ER Checklist was used as indicator of children’s emotion regulation skills.

Data Analysis Plan

Descriptive data were provided to establish the feasibility and acceptability of the STP-PreK. To examine the preliminary efficacy of the STP-PreK and given the open trial nature of this study, we conducted multiple repeated measures ANOVAs. Although we did not have a between-subjects factor, within-subjects follow-up contrast tests, with a Bonferroni correction to minimize type 1 error, were conducted to examine any changes from pre- to post-treatment and to the follow-up assessment. Cohen’s d effect size estimates ([pre-treatment − post-treatment/follow-up assessment]/pooled SD) were provided for all treatment and follow-up analyses. A reliable change index (RCI) was also calculated via the widely used method proposed by Jacobson and Truax (1991) which takes into account measurement error. Individual RCI scores exceeding 1.96 (improvement) or −1.96 (worsening) were considered to reflect reliable change, p < 0.05. Multiple imputation with ten iterations was used to handle missing data, which was missing at random, on the six families that did not participate in the follow-up assessment.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for all of the study’s outcome variables are presented in Table 1. An analysis of the demographic variables revealed a significant association between children’s age at the start of the intervention and their kindergarten readiness (parent report) at pre (r = 0.49, p < 0.01) and post-treatment assessments (r = 0.36, p < 0.05) as well as on the school readiness assessment (Bracken; r = 0.38, p < 0.05) and executive functioning performance (HTKS; r = 0.42, p < 0.05) during the post-treatment assessment. Older children obtained higher scores on the HTKS task and on the Bracken assessment and were reported by their parents as being better prepared for kindergarten. Preliminary analyses did not yield any other significant associations between demographic variables (e.g., SES, sex, maternal education) and children’s school readiness outcomes. Of note and as expected, children’s IQ was related to their pre-treatment school readiness assessment (Bracken; r = 0.70, p < 0.001) and post treatment assessment (r = 0.64, p < 0.001) as well as post-treatment assessment of parental report of kindergarten readiness (r = 0.48, p < 0.01). Subsequently, children’s age at the start of intervention was controlled in all analyses while child IQ was controlled in all academic analyses.

Feasibility and Acceptability

Treatment Fidelity

Average treatment fidelity ranged from 97 to 100 % per session (M = 99 %) indicating that the STP-PreK counselors implemented the program with very strong fidelity. The staff level of engagement with children including the use of positive social reinforcement was also high (M = 6.2 out of 7; range of 4 to 7).

Attendance

Children attended, on average, 96 % of the camp days (37.5 days out of a possible 39 days) while parents attended, on average, 92 % of the number of parent training sessions (7.36 out of eight sessions).

Satisfaction

Parents reported high treatment satisfaction in terms of the summer camp benefiting their child (M rating of 4.83 out of 5) as well as the parent training sessions (M rating of 4.73 out of 5). Parents also highly recommended the program to other parents (M rating of 4.97 out of 5) and felt that the STP-PreK was highly effective in changing their child’s problems (M rating of 4.80 out of 5).

Improvement Ratings

Both parents and counselors indicated a high degree of improvement across the four broad domains assessed by the improvement scale. Overall, parents reported greater improvement than counselors, with the highest ratings of functioning occurring for overall behavior (M rating of 6.3 out of 7—“Much improved”; SD = 1.34), followed by attention and social-emotional functioning (M ratings of 6.2 out of 7; SD = 1.32), and academic improvement (M = 6.07, SD = 1.41). Counselors indicated greatest improvement in the social-emotional (M rating of 6.01 out of 7—“Much improved”; SD = 0.52) and behavioral (M = 5.90, SD = 0.57) domains followed by the attentional (M = 5.69, SD =0.45) and academic subscales (M = 5.67, SD = 0.55).

Preliminary Efficacy

School Readiness Outcomes: Academic Functioning

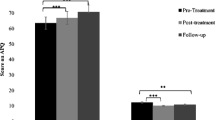

As seen in Table 2, significant changes were observed from pre-treatment to post-treatment on the Bracken School Readiness Assessment and on the parent report KBACS, even after controlling for children’s age and IQ, Cohen’s d = 0.58 and 2.22, respectively. Specifically, children improved their academic skills while parents reported their children as being significantly better prepared for kindergarten. According to parent report KBACS, such improvements were significantly maintained during the follow-up assessment (d = 1.08), although there was a significant decrease from the post-treatment to follow-up assessment (d = 0.81).

School Readiness Outcomes: Behavioral and Adaptive Functioning

Significant changes were also observed from pre-treatment to post-treatment on the externalizing behavior problem and adaptive skills composites on the BASC-2, d = 1.92 and 0.91, respectively. According to parents, children decreased the severity of their externalizing behavior problems while increasing their adaptive skills. In fact, prior to the intervention, 75 % of children had scores on the externalizing behavior problems composite in the at-risk range or higher (t-score of 60 or above). After the intervention, only 7 % of the sample scored in the at-risk range or higher. Such improvements were significantly maintained during the follow-up assessment (d = 1.26 for externalizing behavior problems and d = 0.37 for adaptive skills). Of note, there was a significant increase in externalizing behavior problems (d = 0.74) and a decrease in adaptive skills (d = 0.47) from the post-treatment to follow-up assessment, although the mean t-scores remained in the non-clinical range. Only 28 % of children scored in the at-risk range or higher on the externalizing behavior problem composite 6 months after the intervention ended.

School Readiness Outcomes: Self-regulation Skills

Both a parent report measure (BRIEF) and a standardized assessment (HTKS) of executive functioning also significantly changed from the pre-treatment to post-treatment assessment, d = 0.90 and 1.02, respectively. According to parents, children decreased the severity of their executive functioning difficulties while children’s performance on a standardized executive functioning task showed large increases. Such improvements were significantly maintained during the follow-up assessment (d = 1.14 for BRIEF and d = 1.03 for HTKS) with no significant differences between post-treatment and follow-up assessment scores noted (d = 0.14 for BRIEF and d = 0.09 for HTKS).

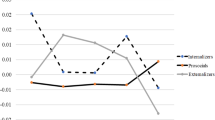

Lastly, children’s emotion regulation skills also significantly improved from pre-treatment to post-treatment as evident by both a parent report measure (ER checklist) and the coding of children’s global regulation and proportion of distress during the two frustration tasks (LAB-TAB), d = 0.47, 0.55, and 0.89, respectively. While the improvement of children’s emotion regulation skills according to parent report (ER checklist) was not maintained during the follow-up assessment (d = 0.28), they were maintained when examined via the frustrations tasks (d = 0.91 for global regulation and d = 0.76 for proportion of distress, respectively).

Reliability of Intervention Effects

While the STP-Prek had statistically significant and sizable effect sizes on most outcomes, it is important to determine the reliability of such improvements. Table 3 shows the RCI results, specifically the number of individuals who showed significant increases, decreases, or no significant change across the school readiness outcomes. For example, across academic outcomes, between 97 and 47 % of children showed positive reliable changes (mean RCI = 11.71, SD = 6.01 for KBACS and mean RCI = 2.20, SD = 2.56 for Bracken). Within the behavioral and adaptive functioning domains, between 60 and 47 % of children showed positive reliable changes (mean RCI = 2.38 SD = 1.60 for externalizing behavior problems and mean RCI = 1.56, SD = 1.33 for adaptive skills). Lastly, within the self-regulation domain, more positive reliable changes were observed within the executive functioning domain (67 % for BRIEF and 60 % for HTKS, respectively) compared to emotion regulation measures (40–13 % across parent report and observational coding).

Discussion

This study supports the promise of a summer treatment program for pre-kindergarteners (STP-PreK), adapted from the evidence-based system used in the Children’s Summer Treatment Program Academic Learning Centers (Pelham et al. 2010), to improve preschoolers with externalizing behavior problems’ (EBP) school readiness skills. The STP-PreK was: (1) implemented by clinicians with high fidelity, (2) was very well received by families as evidenced by high levels of treatment attendance and satisfaction, and (3) led to large and reliable improvements across multiple domains of school readiness, including behavioral, academic, and self-regulation (emotion regulation and executive functioning), as reported by parents and documented through observational/standardized assessments. Each area of improvement is discussed in further detail below.

Behavioral parent training (PT) is often the preferred treatment choice for young children with EBP given its well-established efficacy (Eyberg et al. 2008; Pelham and Fabiano 2008). However, attrition tends to be a significant problem among these parenting interventions, with as many as one-third to 60 % of families terminating treatment early (Eyberg et al. 2001; Werba et al. 2006; Kazdin and Wassell 1998). Families of the STP-PreK attended 92 % of PT sessions with zero families dropping out of treatment. Such high attendance rates are similar to STP studies with older children (Pelham et al. 2010) and are significantly higher compared to other PT studies (Chronis et al. 2004). Given that families that terminate PT prematurely have poorer long-term outcomes than treatment completers (Boggs et al. 2005), it appears that the addition of an intensive child-based treatment component (i.e., summer camp) coupled with daily interactions and feedback from staff on child performance maximizes parental engagement in treatment, and results in similar or better behavioral improvements as compared to PT-alone interventions.

It is also possible that the addition of an intensive child-focused behavioral management system resulted in more rapid behavioral, attentional, and social-emotional improvement than PT-alone treatment, thus maintaining and enhancing parental motivation over the course of the 8-week program. Indeed, the high degree of reported treatment acceptability and satisfaction with the child-focused aspects of the STP-PreK indicates that this component was essential in maintaining engagement and increasing intervention success. While half of our families were self-referred, which may reflect their high degree of motivation to attend the intervention, the other half were referred from school personnel and mental health professionals/physicians. Hence, the extremely high attendance and satisfaction rates of the STP-PreK intervention does not appear to be primarily due to only having highly motivated parents seeking out treatment. Nevertheless, it will be important to examine the efficacy of the STP-PreK within a higher risk sample that may not be actively pursuing treatment.

Consistent with our hypotheses, we found significant improvements in children’s kindergarten readiness outcomes across domains. First, children’s EBP significantly reduced across the treatment period and was largely maintained 6 months after treatment ended. The strict behavioral management system employed in STP-PreK focuses on children’s behavioral functioning in the classroom in terms of attending to the seven classroom rules along with the implementation of a time out system for more severe behavior problems. Preschoolers quickly learned the classroom rules and how to “keep their dots” as well as how to exchange earned “dots” for daily rewards. The engaging, high-praise atmosphere of the program made contingency management procedures, such as time outs and earning twice-daily recess, highly effective as children did not want to miss out on fun activities as a result of their misbehavior. Finally, the DRC and daily communication between the teacher and parents contributed to children making the connection between their school behavior and contingent home rewards and privileges.

Children’s academic outcomes also significantly improved across the treatment period, even after accounting for their intelligence levels. Parents’ perception of their children school readiness also improved across the summer months and was maintained during the 6 month follow-up assessment. Although studies have documented the efficacy of the Literacy Express curriculum in improving pre-literacy skills among typically developing preschool children as well as children underachieving (e.g., Lonigan et al. 2011), our study marks the first to show how an adaptation of Literacy Express can provide academic benefits among preschool children with EBP within a relatively short period (i.e., 8 weeks compared to 30–40 weeks required by the curriculum). The fact that these academic gains occurred during the summer months is even more impressive given well established research showing that children experience significant academic losses during the summer break (Cooper et al. 1996).

Part of children’s academic improvements may also have been a function of the STP-PreK promoting parents’ academic involvement. Typical behavioral PT programs do not directly address children’s academic difficulties and not surprisingly, fail to find large or even moderate improvements within the academic domain despite improvements in children’s behavioral functioning (Chronis et al. 2004; Kaminski et al. 2008). In the STP-PreK, however, parents a) were provided daily feedback on children’s academic productivity/accuracy in the classroom, b) had to help children with their daily homework assignments, and c) were encouraged to prepare children for a weekly test. The School Readiness Parenting Program that accompanied the STP-PreK also addressed how to handle behavior problems during homework time and how to maximize positive interactions during reading and other academic activities. Given that children’s academic functioning was addressed both during the camp and PT, it will be important for future studies to determine which implementation (camp vs. PT vs. both) is more cost-effective while still yielding the best school readiness outcomes.

Lastly, children’s social-emotional and self-regulation functioning also significantly improved across the treatment period with EF, observed emotion regulation, and adaptive skills improvements maintained during the follow-up period. The importance of children’s ER and EF as contributing to school readiness has been highlighted over the last decade across various studies (Blair and Diamond 2008; Eisenberg et al. 2010; Ursache et al. 2012). Recent intervention efforts have focused on determining how to target such self-regulation deficits and/or maximize these skills (Bierman et al. 2008; Raver et al. 2009; Bodrova and Leong 2007), particularly among children with EBP, such as those diagnosed with ADHD, who display significant impairment in these domains as compared to typically-developing children (Barkley 2010; Walcott and Landau 2004). While there has been mixed evidence on the effectiveness of the Tools of the Mind curriculum on children’s self-regulation skills and subsequent academic functioning (Barnett et al. 2008; Diamond et al. 2007), the REDI and CSRP programs appear to improve children’s self-regulation skills and emergent literacy skills (Bierman et al. 2008) and math skills (Raver et al. 2011). As mentioned in the introduction, however, the above programs have primarily focused on typically developing children. The findings from our STP-PreK program further contributes to this literature by showing that preschool children with EBP’s social-emotional and self-regulation functioning can be effectively targeted with a comprehensive intervention that includes both classroom and parent components. Our study is also the first to document specific ER improvements as measured via laboratory frustration tasks. Of note, improvements in emotion regulation skills, as reported by parents, were not as reliable nor were they maintained during the follow-up period. It is possible that the lower rates of reliable and maintained improvement across the parent rated report of emotion regulation was due to a ceiling effect of the measurement used as most parents did not endorse a significant amount of emotion dysregulation. While more research is needed, it does appear that observational tasks are more sensitive in detecting young children’s emotion dysregulation compared to parent report and should be considered when examining intervention effects.

From the present study, it is not possible to determine the specific intervention components that were actually responsible for improving children’s self-regulation skills. It is possible that that strict behavioral management system employed by the STP-PreK was responsible for intervention success. For example, it may be argued that the reinforcement of certain classroom rules (e.g., following teacher’s directions, staying on task) may naturally enhance children’s self-regulation skills. In contrast, the intensive social-emotional/self-regulation curriculum more specifically targeted children’s social skills, emotional awareness, and EF skills. In fact, research suggests that a less-rigorous EF intervention—the implementation of circle time games alone, which were adapted for the STP-PreK—can have an effect on children’s self-regulation and subsequent academic functioning (Tominey and McClelland 2011). Moving forward, computerized working memory training has also emerged as a potential way to improve children’s behavioral self-regulation skills (Beck et al. 2010; Green et al. 2012), although the effects have not typically generalized to non-executive tasks (for review, see Shipstead et al. 2012). Hence, it will be important for future studies across intervention programs to examine, via randomized control trials, which curriculum components are essential to improving children’s school readiness outcomes. The behavioral management system, for instance, is a critical component in reducing EBP among clinical populations, yet may not be sufficient to address social-emotional/self-regulation and school readiness functioning. On the other hand, a classroom-based social-emotional/self-regulation curriculum may be equally or more beneficial than a more expensive and less generalizable computerized working memory training program.

There were some limitations to the current study that need to be addressed. First, although findings were statistically significant with large effect sizes, the small sample size that accompanies an open trial is a significant limitation. Second, with no control group, threats to validity, such as regression to the mean, cannot be completely ruled out although the inclusion of a reliable change index (RCI) in this study aids in determining the reliability of our improvement findings. A randomized trial would provide further confidence in these findings as it relates to the overall efficacy of the STP-PreK as well as lend itself to an examination of the various components of the STP-PreK. It would be essential to determine whether providing PT-alone, for example, yields similar benefits compared to the more costly intensive summer camp approach. At a programmatic level, it will also be necessary to examine whether the inclusion of the social-emotional/self-regulation curriculum yields further benefits compared to just the behavioral management curriculum which may be easier to transport to kindergarten classrooms. A third limitation was the homogeneity of the sample, which was largely Hispanic (77 %) due to the study’s geographical location. However, this limitation may also be viewed as a strength as Hispanic children represent the fastest growing group in the U.S. but are understudied in child intervention research (La Greca et al. 2009). Nevertheless, future research should investigate the efficacy of the STP-PreK among other groups. A final limitation was the inability to collect data on children’s behavior at school to measure generalization of treatment effects. Anecdotally, most parents who completed the STP-PreK commented that their children were doing well in kindergarten, although it will be critical for future studies to examine the extent to which improvements seen within the STP-PreK generalizes to the school environment.

In sum, our findings highlight the promise of the STP-PreK as a treatment package for preschoolers with EBP who are at high risk for having difficulties transitioning to kindergarten. All families completed the intervention with very high attendance and reported excellent satisfaction with treatment. Large effect sizes across mother report, observations, and standardized assessments showed that the STP-PreK was very effective in reducing EBP and improving multiple school readiness outcomes, including children’s emotion regulation and executive functioning skills. Children’s gains across all school readiness outcomes were also maintained 6 months after the intervention ended providing some evidence to the long lasting impact of our summer intervention. It is our hope that future, larger studies will support the efficacy of the STP-PreK in improving school readiness outcomes among preschoolers with EBP. Given the intensive labor and resources required to operate the STP-PreK, it will be important for future work to examine how to best transport the STP-PreK or targeted components to community sites as previously done successfully with the older children’s STP (see Pelham et al. 2010). Future investigations should extend the follow-up assessment period to detect treatment maintenance during the next academic year. Finally, it will be important to determine whether certain children may need further services during the kindergarten year.

References

Al Otaiba, S., & Fuchs, D. (2002). Characteristics of children who are unresponsive to early literacy intervention: a review of the literature. Remedial and Special Education, 23, 300–316.

Arbeau, K. A., & Coplan, R. J. (2007). Kindergarten teachers’ beliefs and responses to hypothetical prosocial, asocial, and antisocial children. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 53(2), 291–318.

August, G. J., Bloomquist, M. L., Realmuto, G. M., & Hektner, J. M. (2007). The early risers “skills for success” program: A targeted intervention for preventing conduct problems and substance abuse in aggressive elementary school children. In P. H. Tolan, J. Szapocznick, & S. Sambrano (Eds.), Preventing youth substance abuse: Science-based programs for children and adolescents (pp. 137–158). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Barkley, R. A. (2010). Deficient emotional self-regulation: a core component of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of ADHD & Related Disorders, 1(2), 5–37.

Barnett, W. S., Jung, K., Yarosz, D. J., Thomas, J., Hornbeck, A., Stechuk, R., et al. (2008). Educational effects of the tools of the mind curriculum: a randomized trial. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 299–313.

Beck, S. J., Hanson, C. A., Puffenberger, S. S., Benninger, K. L., & Benniger, W. B. (2010). A controlled trial of working memory training for children and adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39, 825–836.

Bierman, K. L., Nix, R. L., Greenberg, M. T., Blair, C., & Domitrovich, C. E. (2008). Executive functions and school readiness intervention: Impact, moderation, and mediation in the head start REDI program. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 821–843.

Blair, C. (2002). School readiness: integrating cognition and emotion in a neurobiological conceptualization of children’s functioning at school entry. American Psychologist, 57, 111–127.

Blair, C., & Diamond, A. (2008). Biological processes in prevention and intervention: the promotion of self-regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Development and Psychopathology, 20, 899–911.

Blair, C., & Razza, R. P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78, 647–663.

Bodrova, E., & Leong, D. J. (2007). Tools of the mind: The Vygotskian approach to early childhood education (2nd ed.). New York: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Boggs, S. R., Eyberg, S. M., Edwards, D. L., Rayfield, A., Jacobs, J., Bagner, D., & Hood, K. K. (2005). Outcomes of parent-child interaction therapy: A comparison of treatment completers and study dropouts one to three years later. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 26(4), 1–22.

Bracken, B. A. (2002). Bracken school readiness assessment, second. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation.

Brestan, E., Jacobs, J., Rayfield, A., & Eyberg, S. M. (1999). A consumer satisfaction measure for parent–child treatments and its relationship to measures of child behavior change. Behavior Therapy, 30, 17–30.

Bronson, M. B., Tivnan, T., & Seppanen, P. S. (1995). Relations between teacher and classroom activity variables and the classroom behaviors of prekindergarten children in Chapter 1 funded programs. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16, 253–282.

Bush, G., Luu, P., & Posner, M. I. (2000). Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4, 215–222.

Calkins, S. D. (2007). The emergence of self-regulation: Biological and behavioral control mechanisms supporting toddler competencies. In C. Brownell & C. Kopp (Eds.), Socioemotional development in the toddler years: Transitions and transformations (pp. 261–284). New York: Guilford Press.

Calkins, S. D., Graziano, P. A., & Keane, S. P. (2007). Cardiac vagal regulation differentiates among children at risk for behavior problems. Biological Psychology, 74, 144–153.

Campbell, S. (2002). Behavior problems in preschool children: Clinical and developmental issues (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

Campbell, S. B., & Ewing, L. J. (1990). Follow‐up of hard‐to‐manage preschoolers: adjustment at age 9 and predictors of continuing symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 31, 871–889.

Chronis, A. M., Chacko, A., Fabiano, G. A., Wymbs, B. T., & Pelham, W. E., Jr. (2004). Enhancements to the behavioral parent training paradigm for families of children with ADHD: review and future directions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7, 1–27.

Clark, C. A., Pritchard, V. E., & Woodward, L. J. (2010). Preschool executive functioning abilities predict early mathematics achievement. Developmental Psychology, 46, 1176–1191.

Cooper, H., Charlton, K., Valentine, J. C., & Muhlenbruck, L. (2000). Making the most of summer school: A meta-analytic and narrative review. Monographs of the Society for Research Development, 65(1), 1–118.

Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J., & Greathouse, S. (1996). The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: a narrative and meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 66, 227–268.

Cunningham, C. E., Bremmer, R.B., & Secord-Gilbert, M. (1998). COPE, the Community Parent Education Program: A school based family system oriented workshop for parents of children with disruptive behavior disorders (Leader’s manual). Hamilton, ON: COPE Works.

Denham, S. A. (2006). Social-emotional competence as support for school readiness: what is it and how do we assess it? Early Education and Development, 17, 57–89.

Diamond, A., Barnett, W. S., Thomas, J., & Munro, S. (2007). Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science, 318, 1387–1388.

Eisenberg, N., Valiente, C., & Eggum, N. D. (2010). Self-regulation and school readiness. Early Education and Development, 21, 681–698.

Espy, K. A., McDiarmid, M. M., Cwik, M. F., Stalets, M. M., Hamby, A., & Senn, T. E. (2004). The contribution of executive functions to emergent mathematic skills in preschool children. Developmental Neuropsychology, 26, 465–486.

Eyberg, S. M., Funderburk, B. W., Hembree-Kigin, T. L., McNeil, C. B., Querido, J. G., & Hood, K. K. (2001). Parent–child interaction therapy with behavior problem children: one and two year maintenance of treatment effects in the family. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 23(4), 1–20.

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., & Boggs, S. R. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37, 215–237.

Fabiano, G. A., Pelham, W. E., Gnagy, E. M., Burrows-MacLean, L., Coles, E. K., Chacko, A., et al. (2007). The single and combined effects of multiple intensities of behavior modification and multiple intensities of methylphenidate in a classroom setting. School Psychology Review, 36, 195–216.

Gioia, G. A., Espy, K. A., & Isquith, P. K. (2003). The behavior rating inventory of executive function—preschool version. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Goldsmith, H. H., & Rothbart, M. K. (1996). The Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (LAB-TAB): Locomotor Version 3.0. Technical manual. Madison: Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin.

Graziano, P., Hart, K., & Slavec, J. (2013). School Readiness Parenting Program. Unpublished Leader's Manual.

Graziano, P., Keane, S. P., & Calkins, S. D. (2011). Sustained attention development during the toddlerhood to preschool period: associations with toddlers’ emotion regulation strategies and maternal behavior. Infant and Child Development, 20, 389–408.

Graziano, P., Reavis, R., Keane, S. P., & Calkins, S. D. (2007). The role of emotion regulation in children’s early academic success. Journal of School Psychology, 45, 3–19.

Green, C. T., Long, D. L., Green, D., Iosif, A. M., Dixon, J. F., Miller, M. R., et al. (2012). Will working memory training generalize to improve off-task behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Neurotherapeutics, 9, 639–648.

Greenberg, M. T., Kusche, C. A., Cook, E. T., & Quamma, J. P. (1995). Promoting emotional competence in school-aged children: the effects of the PATHS curriculum. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 117–136.

Halqren, D. W., & Clarizio, H. F. (1992). Rural special education placements: stability and change. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 8, 89–96.

Hart, K., & Graziano, P. (2013). Assessing kindergarten readiness: The development of a new tool to assess preschoolers' behavioral, social-emotional, and academic functioning in the transition to kindergarten. Nashville, TN: Paper presented at the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.

Isquith, P. K., Crawford, J. S., Espy, K. A., & Gioia, G. A. (2005). Assessment of executive function in preschool‐aged children. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 11(3), 209–215.

Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 12–19.

Jimerson, S., Carlson, E., Rotert, M., Egeland, B., & Sroufe, L. A. (1997). A prospective, longitudinal study of the correlates and consequences of early grade retention. Journal of School Psychology, 35, 3–25.

Kaminski, R. A., & Stormshak, E. A. (2007). Project STAR: Early intervention with preschool children and families for the prevention of substance abuse. In P. Tolan, J. Szcopoznik, & S. Sambrano (Eds.), Preventing youth substance abuse: Science-based programs for children and adolescents (pp. 89–109). Washington: American Psychological Association.

Kaminski, J. W., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., & Boyle, C. L. (2008). A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 567–589.

Kazdin, A. E., & Wassell, G. (1998). Treatment completion and therapeutic change among children referred for outpatient therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 29, 332–340.

Kuhl, J., & Kraska, K. (1989). Self-regulation and metamotivation: Computational mechanisms, development, and assessment. In R. Kanfer, P. I. Acherman, & R. Cudeck (Eds.), Abilities, motivation, and methodology: Minnesota symposium on individual differences (pp. 343–368). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Kupersmidt, J. B., Bryant, D., & Willoughby, M. T. (2000). Prevalence of aggressive behaviors among preschoolers in Head Start and community child care programs. Behavioral Disorders, 26, 42–52.

La Greca, A. M., Silverman, W. K., & Lochman, J. E. (2009). Moving beyond efficacy and effectiveness in child and adolescent intervention research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 373–382.

Lahey, B. B., Pelham, W. E., Loney, J., Lee, S. S., & Willcutt, E. (2005). Instability of the DSM-IV subtypes of ADHD from preschool through elementary school. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(8), 896–902.

Lonigan, C. J., Clancy-Menchetti, J., Phillips, B. M., McDowell, K., & Farver, J. M. (2005). Literacy Express: A preschool curriculum. Tallahassee: Literacy Express.

Lonigan, C. J., Farver, J. M., Phillips, B. M., & Clancy-Menchetti, J. (2011). Promoting the development of preschool children’s emergent literacy skills: a randomized evaluation of a literacy-focused curriculum and two professional development models. Reading and Writing, 24, 305–337.

Luby, J. L., Heffelfinger, A., Measelle, J. R., Ablow, J. C., Essex, M. J., Dierker, L., et al. (2002). Differential performance of the MacArthur HBQ and DISC-IV in identifying DSM-IV internalizing psychopathology in young children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(4), 458–466.

Mahone, E. M., & Hoffman, J. (2007). Behavior ratings of executive function among preschoolers with ADHD. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 21, 569–586.

Majdandžić, M., & Van Den Boom, D. C. (2007). Multimethod longitudinal assessment of temperament in early childhood. Journal of Personality, 75, 121–168.

Malecki, C. K., & Elliot, S. N. (2002). Children’s social behaviors as predictors of academic achievement: a longitudinal analysis. School Psychology Quarterly, 17, 1–23.

Masten, A. S., Roisman, G. I., Long, J. D., Burt, K. B., Obradović, J., Riley, J. R., et al. (2005). Developmental cascades: linking academic achievement and externalizing and internalizing symptoms over 20 years. Developmental Psychology, 41, 733–746.

McClelland, M. M., Cameron, C. E., Connor, C. M., Farris, C. L., Jewkes, A. M., & Morrison, F. J. (2007). Links between behavioral regulation and preschoolers’ literacy, vocabulary, and math skills. Developmental Psychology, 43, 947–959.

McClelland, M. M., Acock, A. C., & Morrison, F. J. (2006). The impact of kindergarten learning-related skills on academic trajectories at the end of elementary school. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21, 471–490.

McClelland, M. M., Morrison, F. J., & Holmes, D. L. (2000). Children at risk for early academic problems: the role of learning-related social skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15, 307–329.

MTA Cooperative Group. (1999). A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 56, 1073–1086.

Nolan, E. E., Gadow, K. D., & Sprafkin, J. (2001). Teacher reports of DSM-IV ADHD, ODD, and CD symptoms in schoolchildren. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 241–249.

Panter, J. E., & Bracken, B. A. (2009). Validity of the Bracken School Readiness Assessment for predicting first grade readiness. Psychology in the Schools, 46(5), 397–409.

Pelham, W. E., Jr., & Fabiano, G. A. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37, 184–214.

Pelham, W. E., Foster, E. M., & Robb, J. A. (2007). The economic impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Ambulatory Pediatrics, 7(1), 121–131.

Pelham, W. E., Gnagy, E. M., Greiner, A. R., Waschbush, D. A., Fabiano, G., & Burrows-MacLean, L. (2010). Summer treatment programs for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. In J. Weisz & A. Kazdin (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (pp. 277–294). New York: The Guilford Press.

Pelham, W. E., Gnagy, E. M., Greiner, A., Hoza, B., Hinshaw, S. P., Swanson, J. M., et al. (2000). Behavioral versus behavioral & pharmacological treatment in ADHD children attending a summer treatment program. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 507–526.

Pennington, B. F., & Ozonoff, S. (1996). Executive functions and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37, 51–87.

Pianta, R. C., Steinberg, M. S., & Rollins, K. B. (1995). The first two years of school: teacher-child relationships and deflections in children’s classroom adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 295–312.

Ponitz, C. E., McClelland, M. M., Jewkes, A. M., Connor, C. M., Farris, C. L., & Morrison, F. J. (2008). Touch your toes! Developing a direct measure of behavioral regulation in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23, 141–158.

Raver, C. C., Jones, S. M., Li‐Grining, C., Zhai, F., Bub, K., & Pressler, E. (2011). CSRP’s impact on low‐income preschoolers’ preacademic skills: self‐regulation as a mediating mechanism. Child Development, 82, 362–378. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01561.x.

Raver, C. C., Jones, S. M., Li-Grining, C., Zhai, F., Metzger, M. W., & Solomon, B. (2009). Targeting children’s behavior problems in preschool classrooms: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77, 302–316.

Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2004). Behavior Assessment System for Children – second edition (BASC-2). Bloomington: Pearson.

Redden, S. C., Forness, S. R., Ramey, S. L., Ramey, C. T., & Brezausek, C. M. (2003). Mental health and special education outcomes of Head Start children followed into elementary school. NHSA Dialog: A Research-to-Practice Journal for the Early Intervention Field, 6, 87–110.

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Pianta, R. C. (2000). An ecological perspective on the transition to kindergarten: a theoretical framework to guide empirical research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 21, 491–511.

Risi, S., Gerhardstein, R., & Kistner, J. (2003). Children’s classroom peer relationships and subsequent educational outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 351–361.

Safran, S., & Safran, J. (1984). Elementary teacher’s tolerance of problem behaviors. The Elementary School Journal, 85, 236–243.

Sattler, J. M., & Dumont, R. (2004). Assessment of children: WISC-IV and WPPSI-III supplement. San Diego: Jerome M. Sattler, Publisher.

Schneider, M. R. (1974). Turtle technique in the classroom. Teaching Exceptional Children, 7, 22–24.

Special Education Elementary Longitudinal Study (SEELS). (2005). SEELS data documentation. Washington: Office of Special Education Programs.

Shields, A., & Cicchetti, D. (1997). Emotion regulation among school-age children: the development and validation of a new criterion Q-sort scale. Developmental Psychology, 33, 906–916.

Shaffer, D., Fisher, P., Lucas, C. P., Dulcan, M. K., & Schwab-Stone, M. E. (2000). NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 28–38.

Shipstead, Z., Redick, T. S., & Engle, R. W. (2012). Is working memory training effective? Psychological Bulletin, 138, 628–654.

Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (1998). Preventing reading difficulties in young children. Washington: National Academy Press.

Tominey, S. L., & McClelland, M. M. (2011). Red light, purple light: findings from a randomized trial using circle time games to improve behavioral self-regulation in preschool. Early Education & Development, 22, 489–519.

Upshur, C., Wenz-Gross, M., & Reed, G. (2009). A pilot study of early childhood mental health consultation for children with behavioral problems in preschool. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24, 29–45.

Ursache, A., Blair, C., & Raver, C. C. (2012). The promotion of self‐regulation as a means of enhancing school readiness and early achievement in children at risk for school failure. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 122–128.

Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2004). Understanding self-regulation: An introduction. In R. F. Baumeister & K. D. Vohs (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 1–9). New York: Guilford Press.

Walcott, C. M., & Landau, S. (2004). The relation between disinhibition and emotion regulation in boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 772–782.

Walker, H. M., Kavanagh, K., Stiller, B., Golly, A., Severson, H. H., & Feil, E. G. (1998). First step to success: an early intervention approach for preventing school antisocial behavior. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 6, 66–80.

Webster‐Stratton, C., Reid, M. J., & Stoolmiller, M. (2008). Preventing conduct problems and improving school readiness: evaluation of the incredible years teacher and child training programs in high‐risk schools. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 49, 471–488.

Wechsler, D. (2002). Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, third edition (WPPSI- -III). Sydney: Pearson.

Welsh, J. A., Nix, R. L., Blair, C., Bierman, K. L., & Nelson, K. E. (2010). The development of cognitive skills and gains in academic school readiness for children from low-income families. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 43–53.

Werba, B. E., Eyberg, S. M., Boggs, S. R., & Algina, J. (2006). Predicting outcome in parent–child interaction therapy success and attrition. Behavior Modification, 30, 618–646.

West, J., Denton, J., & Reaney, L. M. (2001). The kindergarten year: Findings from the early childhood longitudinal study kindergarten class of 1999–1999. Washington: US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics.

Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and emergent literacy. Child Development, 69, 848–872.

Zimmerman, L. K., & Stansbury, K. (2003). The influence of temperamental reactivity and situational context on the emotion-regulatory abilities of three-year-old children. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 164, 389–409.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Experiment Participants