Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to identify themes associated with role conflicts and moral distress experienced by cardiovascular implantable electronic device (CIED) industry-employed allied professionals (IEAPs) in the clinical setting.

Methods

Focus groups were used to elicit perspectives from IEAPs who had deactivated a CIED.

Results

Seventeen IEAPs (five women) reported increased clinical presence and work-related role conflicts and moral distress along several themes: (1) relationships with patients, (2) relationships with clinicians, (3) role ambiguity, (4) customer service to clinicians, and (5) CIED deactivation. Patients often misperceived IEAPs as physicians or nurses. Many physicians expected IEAPs to perform clinical duties. Customer service obligations exacerbated IEAP role conflicts and moral distress because of dual agency. IEAPs commonly received and carried out requests to deactivate CIEDs; doing so, however, generated considerable distress—particularly deactivations of pacemakers in pacemaker-dependent patients. Several described themselves as “angels of death.” IEAPs had recommendations for mitigating role conflicts and moral distress, including improving the deactivation process.

Conclusions

IEAPs experienced role conflicts and moral distress regarding their activities in the clinical setting and customer service obligations. Health care institutions should develop and enforce clear boundaries between IEAPs and clinicians in the clinical setting. Clinicians and IEAPs should adhere to these boundaries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Industry-employed allied professionals (IEAPs) “include directly employed or contracted [cardiovascular implantable electronic device] manufacturer representatives, field clinical engineers, and industry employed technical specialists” [1]. IEAPs frequently interact with clinic- and hospital-based licensed clinicians (e.g., physicians, nurses, and other clinicians) who care for patients being considered for or already have a cardiovascular implantable electronic device (CIED) such as an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), pacemaker, or cardiac resynchronization therapy device. At the request of physicians, nurses, and other licensed clinicians, IEAPs often provide valuable technical assistance and education regarding their companies’ devices at the time of implantation and during follow-up [2]. The indications for and number of patients with CIEDs are increasing [3]. As a result, IEAPs have assumed more clinically related activities (i.e., activities in which the IEAP interacts with a patient and performs a task requiring technical expertise that directly affects a patient’s care) and have become increasingly valuable to physicians and patients [1]. The conflict inherent in this situation—IEAPs’ roles in selling devices while carrying out clinical activities—and the increasing presence of IEAPs in the clinical setting have raised ethical and legal concerns and have resulted in the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) policy statements that clarify the role of IEAPs in the clinical setting [1, 4].

The involvement of IEAPs in clinical activities extends to deactivation of CIEDs (i.e., reprogramming a device so that it no longer delivers therapy). Seriously ill patients (or their surrogates) may request deactivation if ongoing device therapy is no longer consistent with their health care values, goals, or preferences. These patients request device deactivation to avoid physical harm (e.g., shocks delivered by an ICD) and emotional harm (e.g., perceived prolongation of dying and interference with a natural death). Evidence suggests that most CIEDs are deactivated by IEAPs, not by physicians or nurses [5]. Anecdotal evidence suggests that IEAPs experience moral distress when deactivating CIEDs, but empiric research findings regarding their experiences are scant. In this article, we report the results of a qualitative research study, the purpose of which was to identify common themes associated with role conflicts and moral distress experienced by IEAPs in the clinical setting.

2 Methods

This qualitative research study used focus groups as the mechanism for gathering data about IEAP experiences and perspectives. We used purposive sampling to select focus group participants. All IEAPs in our study were registered attendees of the 30th Annual Scientific Meeting of the Heart Rhythm Society (May 13–16, 2009, in Boston, MA, USA). All worked primarily in the clinical arena and had performed at least one CIED deactivation.

Two focus group sessions were scheduled to accommodate IEAP schedules and limit the number of participants to nine IEAPs per session. Each IEAP participated in only one session. Each focus group session lasted 2 h. Moderators followed a semistructured discussion guide that was developed based on the literature [1, 4–6]. The discussion guide included probe questions that sought to draw out the actual experiences of the participants and allowed open-ended conversations if the participants did not reveal this information spontaneously (Table 1). Discussions were informal, and the participants were encouraged to ask each other questions. All participants contributed to the discussions. Focus groups were facilitated by two investigators (P.S.M. and A.L.O.).

The focus group discussion guide was semistructured to include general and specific questions. Discussion began with questions about daily practices and social relationships associated with IEAP roles and concluded with questions about their experiences with CIED deactivation. Responses to questions about their experiences with patients stimulated discussion about moral distress and conflicts between the IEAPs’ company-related activities (e.g., providing technical support) and their roles in patient care. Each IEAP shared a personal story about his or her experience performing a CIED deactivation and described emotional aspects of the experience. The sessions concluded with the IEAPs making suggestions about how their experiences with moral distress and role conflicts could be addressed now and mitigated in the future.

Focus group sessions were taped and fully transcribed; personal identifying information was removed, and transcripts were double-checked for accuracy. Each transcript was reviewed and coded independently by two investigators (P.S.M. and A.L.O.). Standard techniques of qualitative content analysis [7] and principles of grounded theory were used to understand the data [8, 9]. Data were systematically analyzed and instances of discrepancies were discussed before developing a final list of themes [10]. This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board in accordance with federal regulations.

3 Results

Overall, 17 IEAPs (five women, 12 men), representing five CIED manufacturers, participated in the study. Sixteen IEAPs provided demographic information. The median age was 43 years (range, 26–59 years). The median time as an IEAP was 10 years (range, 3–25 years). The median time with the current company was 7.25 years (range, 2–25 years). All participants were college educated (four had some graduate school experience). Most participants (n = 13) were from the Midwestern USA. Several participants reported prior experience in nursing (n = 5), pharmacy (n = 3), engineering (n = 2), business (n = 1), veterinary medicine (n = 1), and administration (n = 1) (four participants did not provide information on this topic).

Analysis of the transcripts generated five common themes associated with moral distress and role conflicts among the IEAPs (Table 2). Here, we expand on a description of these themes and include representative comments made by study participants.

3.1 Relationships with patients

IEAPs in our study described widely varying relationships with patients. The closest relationships were those in which IEAPs interacted with patients regularly and directly (e.g., device interrogation).

There are patients you get to know very well, personally, almost because you see them regularly over the course of years, and there are patients you may see once and never see again. (Focus group [FG] 1, IEAP10)

My experience has been the full spectrum in terms of just an in-and-out “Hi, how are you” sort of thing versus probably the ultimate in which I ended up being a pallbearer for a guy. I found that it wasn’t just the patient, but, of course, the family involved. (FG1, IEAP16)

Despite their varied relationships with patients, all IEAPs believed that their relationships were based on trust and professionalism.

And, you do gain relationships with these patients, and they trust you… (FG2, IEAP13)

3.2 Relationships with clinicians

IEAPs in our study reported varied relationships with physicians, nurses, and other licensed clinicians that depended on the clinicians’ roles and knowledge about CIEDs. In most instances, nurses, family practitioners, general internists, and general cardiologists were viewed as accessible, whereas electrophysiologists were considered insulated. Nevertheless, IEAPs said that clinicians were open to their recommendations most of the time.

[The general internist or general cardiologist] knows you look at [devices] every single day, and [they] are trusting your judgment… (FG1, IEAP12)

The limited knowledge that some physicians, nurses, and other licensed clinicians had about devices was surprising but understandable to the IEAPs.

Their level of understanding—I expected it to be much, much higher! But [a CIED has] a lot of technology. You are trained about anatomy and physiology and cardiology and then to step in to do your nursing work and you get all this technology shoved in front of you. How does it all interact? How do you know? (FG2, IEAP12)

Yes, we are clearly being put into uncomfortable situations where we clearly know more than anyone else. (FG2, IEAP14)

Even so, the IEAPs were explicit when discussing the limits of their roles. They considered themselves simply reporters of information collected by the devices, not individuals who should be making clinical decisions about how devices should be programmed and managed.

That is where the ambiguity comes in because you come in there with a certain level of expertise, and you seem to understand it, and you know a lot, and so on. When it comes down to a decision, that is when you say, “That is you, not me”… (FG1, IEAP14)

3.3 Role ambiguity

Indeed, IEAPs in our study described role ambiguity in settings in which they directly and regularly interacted with patients and engaged in clinically related activities (e.g., device interrogation). Specifically, patients commonly regarded IEAPs as part of the health care team.

In places where we do the [device] checks, they don’t treat us any differently than any doctor or nurse or anything. They don’t really distinguish one from the other. (FG1, IEAP9)

We get a lot of them assuming that you are a physician. (FG1, IEAP7)

This role ambiguity becomes challenging when patients ask IEAPs inappropriate questions (e.g., soliciting medical advice) or request assistance in ways that exceed the IEAP’s duties and blur the role boundaries between clinicians and IEAPs:

I got a call from a patient wanting to know if he could go on his treadmill … Obviously, we don’t provide answers to that, and I kept telling him, “You better call your doc.” So it is amazing sometimes, the questions you do get. (FG1, IEAP6)

[Patients] view us as part of the care team. So, unfortunately, they ask us inappropriate questions …“I don’t really want to ask the doctor about that, but I was just wondering what you thought?” That kind of thing. (FG1, IEAP5)

Sometimes, the role confusion is created by physicians, nurses, and other licensed clinicians, who may also ask IEAPs questions or request assistance in ways that exceed the IEAPs’ expected duties:

Yes, it is a struggle because there are [times in which a clinician] will say, “Well, what do you think I should do?” or “What changes do I need to make in this device?” And you can make a recommendation as to what other places are doing, but it is tricky. It is a very fine line. (FG1, IEAP10)

So, a lot of times we are asked to sort of step outside of the role of just interrogating a device and printing some things out and handing it to someone—where we feel like we need to fill in some spaces here and there to save time for our clinicians and to make sure those patients—that nobody falls through the cracks in certain ways. So, we do sort of overstep sometimes… (FG1, IEAP10)

As mentioned previously, IEAPs sometimes have more knowledge and expertise about cardiac dysrhythmias, CIEDs, and CIED therapies than physicians, nurses, and other licensed clinicians. These situations may create distress for IEAPs.

In the [electrophysiology] clinic, we are kind of grilled to that expectation of well, “Hey, doc, this patient is on no blood thinners but yet has more than 24 hours of atrial fibrillation. Therefore, I’m bringing this up to you.” Therefore, that is a good job. You get a pat on the back. When you get to the cardiologist’s office, it is not necessarily expected to pull everything out of the device because they may not be thinking necessarily of that device as a tool to give them information like atrial fibrillation or anything of that nature….As you kind of get that experience, you are also tasked with that responsibility….It should almost be unethical for us to leave a patient who has [newly discovered atrial fibrillation without asking] “Are you anticoagulated? Has somebody talked to you about rhythm or rate control, etc, etc?” (FG1, IEAP8)

Nevertheless, the IEAPs desired clear role boundaries in the clinical setting.

The physician is the primary caregiver for the patient, first and foremost…[We] in industry are working as their agent on their specific order. (FG2, IEAP15)

3.4 Customer service

IEAPs in our study frequently used the term “service expectation” to describe their work in the clinical setting. Indeed, the expectation and practice of providing on-call customer service (24 h/day and 7 days/week) elicited a strong reaction among IEAPs in our study. The consensus was that their customer service responsibilities had grown tremendously in recent years, and some voiced that it sometimes was used as an unpaid service to remedy staffing shortages in the clinical setting.

Yes, that is part of the unwritten service contract that industry has for health care providers. We are just there 24/7… (FG1, IEAP4)

I find it embarrassing for the United States health care system that, in my mind, so much direct patient care has been turned over to industry… (FG2, IEAP16)

If the rep doesn’t show up, the clinic doesn’t get done. (FG2, IEAP14)

IEAPs in our study believed that location and type of practice affected clinician expectations for IEAP participation in clinical activities.

In our area, I have 3 academic institutions, and they have their own dedicated device clinic nurses, so every implant that is done there [is] going to be followed-up at that device clinic … But in the private practice setting, I have 2 that will have a dedicated day for our company and then there is another one that is just kind of a free-for-all. They don’t have anything scheduled. You have 4 companies in there at one point. It gets ugly sometimes. (FG2, IEAP13)

I think it varies, depending on who you’re working with and which hospital you are at. I mean, some of them it is totally hands-off. Other ones, you are doing just about everything… (FG1, IEAP11)

IEAPs in our study uniformly felt obliged to care for patients, despite sales pressures. They believed, however, that industry competition complicated matters by pushing customer service boundaries. Although IEAPs believed they could decline clinician requests, they worried how such denials would affect their relationships with clinicians and their ability to sell their companies’ products.

The thing that nobody wants to talk about [is that] competition between companies, I think, sometimes plays a role in what our actions are….You don’t want to hear from your physician, “Well, Company X does that for me all the time.”…And the physicians will say, “Well, my Brand X representative does this for me all the time.” (FG1, IEAP10)

3.5 Experiences with CIED deactivation

IEAPs in our study unanimously affirmed that, compared with physicians and nurses, they performed most of the CIED deactivations in seriously ill patients. Requests to deactivate a CIED, however, created distress for IEAPs.

That is a really uncomfortable situation to be put in. And, honestly, I have only had to do that a few times, but when somebody calls, we show up. We are expected to show up, that is our job, but, at the same time, it is like where do we draw the line and say, “No, I’m not going to show up for this particular request.” (FG1, IEAP10)

The IEAPs linked this activity to the increasing amount of clinically related responsibilities that they were being asked to assume.

Yes…there is a reliance on industry for it….A lot of it happens off-site and we are the ones with the programmer….I think it comes down to a reliance on industry for maybe everything. (FG2, IEAP14)

Again, we are in such a unique position. [We are not like] respiratory therapists turning off the ventilator. Well, they are just employees of the hospital. We’re not employees of the hospital….I can’t offhand think of any other health care–related industry where you have that dynamic. (FG1, IEAP16)

Nevertheless, IEAPs in our study uniformly viewed ICD deactivations in seriously ill patients as relatively routine and noncontroversial because deactivating an ICD prevents a dying patient from receiving painful shocks.

Turning off ICD therapies is usually just so they know it is going to be a more comfortable way to go. (FG2, IEAP12)

In contrast to ICDs, pacemaker deactivations were considered as uncommon and controversial, especially in pacemaker-dependent patients, because pacemaker deactivation may precipitate symptoms (e.g., congestive symptoms in a patient with heart failure) and death may occur shortly after the deactivation. Indeed, several IEAPs stated they would not deactivate pacemakers.

I think as far as the pacer goes, [the] device rep should have hands off, no involvement whatsoever. Now if a physician decides they want to do it and the family member says, “I really just want to go”….Let them do it if they want to do it, but the device rep shouldn’t have any part of it. (FG1, IEAP1)

I refused twice to turn a pacemaker off. The reason I refused is [that for] most people, when you turn the pacemaker off, they don’t die, but they feel worse and it could exacerbate or hasten their death. Where, turning an ICD off…it is more pleasant to fall asleep than it is to get shocks. (FG1, IEAP2)

Several IEAPs reported that their companies had policies that prohibited employees from deactivating pacemakers.

I’m really grateful to say that we are not allowed to turn off pacemakers. That is just a huge burden that is lifted. It’s like, “Thank you!” (FG2, IEAP11)

Although these IEAPs were not allowed to directly deactivate pacemakers, they were allowed to reprogram a pacemaker to stop functioning and have a clinician initiate the program change. The IEAPs expressed comfort with this approach.

We don’t terminate [pacemaker] therapy on just someone’s say-so. We would have to have the physician or their designee available to actually operate the programmer to do that. (FG2, IEAP15)

I never physically hit the program button….I will set it all up and then I will have someone hit it….If that makes me sleep at night, maybe that is what it is… (FG1, IEAP1)

IEAPs in our study reported that patients and their families and friends often did not understand the process and likely outcomes of CIED deactivation.

I went to this woman that had a stroke. So she was unresponsive and it was a small-town hospital. I went to turn off the device and…it was a pacemaker—we are not allowed to turn off the pacemaker. So, you just set up your programmer and you show the nurse what button to push and they supposedly take care of it….I had driven at least an hour and 45 minutes, and the reality is that it is one of the many obligations you have during the day, but you’re carving out time to do this. And the priest was there and the family was there. [I] had the nurse push the button and packed my stuff and left because I didn’t know what was going to happen after that. They were very angry because the woman lived another 8 hours. They wanted her to die right then! (FG2, IEAP12)

Indeed, the IEAPs reported that the patients’ loved ones commonly believed that death immediately followed CIED deactivation. Clinicians were similarly unaware.

That is usually what the family thinks. (FG1, IEAP10).

There are a lot of nursing staff that thinks the same thing. It is misunderstood. (FG1, IEAP5)

IEAPs were asked about training and preparation for carrying out CIED deactivation. Most reported little or no training and felt unprepared for their first deactivation. For example, IEAPs in one focus group unanimously answered “no” in response to the question, “Did you receive any training that prepared you for deactivating devices?”

You tend to turn to a colleague. For me, it was my [electrophysiologist]. “So, exactly what do you want me to do when I go out to the hospice organization and turn off this defibrillator? Specifically, what do I need to do?” [He said,] “Just make sure it doesn’t shock—okay? You will be all right.” (FG1, IEAP8)

Notably, the lack of training and preparation did not pertain to the technical and programming aspects of device deactivation—the IEAPs had expertise in these areas. Rather, the IEAPs felt unprepared for the emotional impact of CIED deactivation.

You know, [device deactivation] is part of the service expectation of what we are supposed to do. But you end up being like a robot so that you don’t get too emotional or something….It’s just not ever something we were ever really emotionally prepared for. (FG1, IEAP10)

Yes, it is like putting your hand on the plug and pulling it….It is just very intense, and just—everyone is grieving because their loved one is dying. You are like, “Ooh, I can’t cry with you right now.” (FG2, IEAP11)

IEAPs also described situations in which they received little support from clinicians and were given the responsibility of informing patients and their loved ones about the process and outcomes of CIED deactivation.

I showed up at a hospital once and the physician asked me to turn off the pacemaker. I got there, called him and said, “I’m here.” And he goes, “Well, I’m still seeing patients in the clinic. Would you mind going up and tell the family exactly what you are going to do and what is going to happen?” [Other IEAPs in the group gasped.] So, they are all sitting in the family lounge and I get up there, and the nurse goes, “Yes, I hear you are going to talk to the family.” So I was just stuck not knowing that he wasn’t going to be there and having to go and talk to the family. (FG1, IEAP7)

Many IEAPs referred to their experiences with CIED deactivations as “war stories.” The emotional impact of these experiences was apparent.

I [felt] like the angel of death. (FG2, IEAP11)

The first time I ever had to do it, I was fine until I walked to my car and thought, “Oh my God.” I just lost it when it was over with. And everyone has got their war story—every rep that you speak to. (FG1, IEAP10)

We basically become the angel of death when we walk in the room. (FG1, IEAP10)

IEAPs in our study had specific recommendations for improving the process of CIED deactivation (Table 3). Recommendations included clarification of roles and responsibilities, as well as improved documentation of the procedure. Along these lines, one IEAP described a positive experience during a CIED deactivation in a dying patient.

My most pleasant experience with that was actually in an oncology ward….And in that [ward], I had a nice discussion. [The nurse] showed me the chart, I asked for the order. “Here it is right here, spelled out, we talked to the [electrophysiologist] already, he is perfectly fine with this.”…The family had been well prepared. They were all here and all here meant a room like this that was packed with over a dozen people that were shoulder to shoulder and whatever else. And this was the matriarch of the family; this was the oldest living member—80 years old….The nurse, when I walked into the room, basically said, “Here is the gentleman who is going to turn off Ms. So-and-So’s defibrillator”….So, she knew the family very intimately….We had a little discussion about exactly what would happen in a little more technical detail. They had a few more questions. They didn’t want to talk about it in front of the family. Had been fully versed on what a defibrillator was. We had that discussion and…the nurse said, “Thank you for doing that. That went really well.” (FG1, IEAP8)

4 Discussion

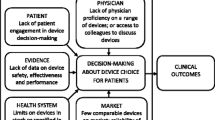

The presence of IEAPs in the clinical setting has grown in recent years because of increases in CIED complexity, indications for CIED, and prevalence of patients with CIEDs. IEAPs are estimated to spend more than 1 million hours per year providing implant support and follow-up services, including CIED deactivation, for patients with CIEDs and their clinicians [6]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore role conflicts and moral distress experienced by IEAPs in the clinical setting. We identified five themes: (1) relationships with patients, (2) relationships with clinicians, (3) role ambiguity, (4) customer service, and (5) experiences with CIED deactivation.

Given the increasing presence of IEAPs in the clinical setting, it was unsurprising that relationships with patients and relationships with clinicians emerged as themes. IEAPs in our study described a wide range of relationships with patients (i.e., from single visits to friendships), although the relationships remained professional. Nevertheless, patients often confused IEAPs with licensed clinicians (e.g., physicians, nurses) and asked IEAPs questions that should have been addressed to clinicians. This confusion, however, is not surprising. It is reasonable for patients to assume that everyone in the clinical environment (including IEAPs) are part of the clinical team, especially when they are engaged in clinically oriented activities such as reprogramming CIEDs. These circumstances, as a result, blur boundaries between IEAPs and clinicians. It is not reasonable, however, for patients who have CIEDs to have to determine who in the clinical environment is an IEAP and who is a licensed clinician. This responsibility falls squarely on clinicians and, in particular, physicians attending to the patients. Furthermore, when IEAPs interact with patients, they should identify themselves as company employees, not clinicians, and they should unambiguously defer CIED management and other clinically oriented questions to clinicians.

IEAPs also described a wide range of relationships with clinicians (i.e., from technician and reporter of data to colleague offering advice). IEAPs sometimes possessed more knowledge about CIEDs than clinicians, especially non-electrophysiologists, and often were more familiar with their companies’ devices. In some clinical scenarios, IEAPs believed they knew the best course of action but lacked the authority to execute that action. These scenarios, which also blur boundaries between IEAPs and clinicians, may precipitate moral distress for IEAPs because they must trust that the involved and responsible clinician will acknowledge and respond to their observations. However, one can also imagine these scenarios being used to enhance CIED sales, particularly as licensed clinicians become more dependent on IEAPs for clinical decision making. The IEAPs in our study did not specifically mention this possibility, but they did believe industry competition pushed customer service boundaries. Thus, the potential for IEAP involvement in the clinical setting to promote CIED sales becomes very real.

In fact, the IEAPs in our study unanimously expressed a desire for clear professional boundaries (i.e., to report CIED data and provide technical assistance, but defer decision making to clinicians). This desire is consistent with HRS policy, which also stipulates that clinicians should not view IEAPs as unpaid employees. In addition, HRS policy stipulates that licensed clinicians are responsible for supervising IEAPs in the clinical setting and that IEAPs should perform their tasks only under the direction of physicians and other clinicians, unless warranted by the clinical situation (e.g., an emergency) [4]. Based on the results of our study, we believe health care institutions should develop and enforce policies regarding the presence of IEAPs in the health care setting [7]. Clinicians and IEAPs should strictly adhere to these policies.

Nevertheless, IEAPs in our study voiced that clinicians who implant devices and manage patients with CIEDs increasingly expect IEAPs to participate in clinically related activities such as device interrogation and CIED deactivation. The IEAPs characterized this work as a customer service obligation and expressed concern that declining participation in such activities likely would negatively affect their relationships with clinicians and hamper their ability to sell products. These concerns reflect IEAPs’ dual agency—they serve their companies (e.g., as sales representatives) and serve clinicians by participating in clinically related activities (e.g., device interrogation, device deactivation) [5]. This dual agency may create role conflict and moral distress when IEAPs attempt to act simultaneously on behalf of their employers, the patients, and clinicians.

CIED deactivation was the clinically related activity that created the most moral distress for IEAPs. Echoing the results of a prior study [5], IEAPs in our study reported that they commonly performed CIED deactivations. They also indicated that ICD deactivation to avoid uncomfortable shocks in a seriously ill patient was morally acceptable, whereas most considered pacemaker deactivation unacceptable (especially in pacemaker-dependent patients). Furthermore, several IEAPs in our study expressed relief that their companies prohibited them from deactivating pacemakers. Even so, these IEAPs reported participating in pacemaker deactivations by entering settings for deactivation into the CIED reprogramming instrument and having clinicians “push the button” to execute the deactivation commands.

Based on their experiences, the IEAPs in our study had specific, patient-centered recommendations for improving the CIED deactivation process that maintain clear professional boundaries between IEAPs and licensed clinicians (Table 3). These recommendations mirror those of the recent HRS expert consensus statement regarding CIED deactivations [11], which includes detailed ethical and legal analyses of the permissibility of CIED deactivations (including pacemaker deactivations), addressing the care needs of patients undergoing CIED deactivations, and the roles of clinicians and IEAPs.

Although physicians were not included in the focus groups, the role some physicians have in creating and/or sustaining IEAP role conflicts and moral distress must be addressed. The focus groups clearly reflected that some—but not all—physicians may account for most of the problems. If the responsible physicians routinely provided appropriate oversight, were readily available (as they should be under current reimbursement guidelines), and were willing to discuss directly anything being asked of the IEAP, the problems may be largely obviated.

The ultimate issue is defining the border between appropriate and inappropriate roles of the IEAP in the clinical environment. The influence of income and their employers’ expectations regarding sales and service delivery (i.e., IEAPs may feel pressured for results from immediate supervisors, even if company policy officially states otherwise), must be considered for the role conflicts and moral distress to reflect the environment as we know it.

5 Conclusion

IEAPs experience role conflicts and moral distress from their activities in the clinical setting and their customer service obligations. Hospital- and clinic-based clinicians should recognize these concerns. Health care institutions should establish and enforce policies that maintain clear boundaries between IEAP and clinician activities in the clinical setting. Clinicians and IEAPs should adhere to these policies.

Abbreviations

- CIED:

-

Cardiovascular implantable electronic device

- FG:

-

Focus group

- HRS:

-

Heart Rhythm Society

- ICD:

-

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- IEAP:

-

Industry-employed allied professional

References

Hayes, J. J., Juknavorian, R., & Maloney, J. D. (2001). The role(s) of the industry employed allied professional. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 24(3), 398–399.

Wilkoff, B. L., Auricchio, A., Brugada, J., Cowie, M., Ellenbogen, K. A., Gillis, A. M., et al. (2008). HRS/EHRA expert consensus on the monitoring of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs): Description of techniques, indications, personnel, frequency and ethical considerations. Heart Rhythm, 5(6), 907–925.

Mond, H. G., Irwin, M., Ector, H., & Proclemer, A. (2008). The world survey of cardiac pacing and cardioverter-defibrillators: calendar year 2005: An International Cardiac Pacing and Electrophysiology (ICPES) project. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 31(9), 1202–1212.

Lindsay, B. D., Estes, N. A., III, Maloney, J. D., & Reynolds, D. W. (2008). Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm Society policy statement update: recommendations on the role of industry employed allied professionals (IEAPs). Heart Rhythm, 5(11), e8–e10. Epub 2008 Sep 24.

Mueller, P. S., Jenkins, S. M., Bramstedt, K. A., & Hayes, D. L. (2008). Deactivating implanted cardiac devices in terminally ill patients: practices and attitudes. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 31(5), 560–568.

McCoy, F. (2003). More than a device: Today’s medical technology companies provide value through service. Cardiac Electrophysiology Review, 7(1), 54–57.

Krueger, R. A. & Casey, M. A. (2009). Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research (4th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

Clarke, A. (2005). Situational analysis: grounded theory after the postmodern turn. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Pope, C., Ziebland, S., & Mays, N. (2000). Qualitative research in health care: Analyzing qualitative data. BMJ, 320(7227), 114–116.

Lampert, R., Hayes, D. L., Annas, G. J., Farley, M. A., Goldstein, N. E., Hamilton, R. M., et al. (2010). HRS expert consensus statement on the management of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs) in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. Heart Rhythm, 7(7), 1008–1026.

The study was funded by a grant received by Dr Mueller, the Mayo Clinic Scholarly Opportunity Award.

Conflict of interest

Dr Mueller is a member of the Boston Scientific Patient Safety Advisory Board. He lectures for the Boston Scientific Education Services, and he is an Associate Editor for Journal Watch General Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mueller, P.S., Ottenberg, A.L., Hayes, D.L. et al. “I felt like the angel of death”: role conflicts and moral distress among allied professionals employed by the US cardiovascular implantable electronic device industry. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 32, 253–261 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-011-9607-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10840-011-9607-8