Abstract

Using 2005 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data, this study explores problematic mortgage application behaviors including submitting incomplete paperwork when seeking a mortgage, withdrawing a loan application before the lender makes a credit decision, rejecting a lender approved loan offer and accepting a high interest rate loan. Tract-level college completion rates, homeownership rates, and household age, as well as race, ethnicity, and income are all associated with problematic loan application behaviors, although these relationships vary across behaviors. The results of this analysis may prove useful for targeting financial education and counseling efforts to areas with the greater potential needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Because mortgage contracts are complex instruments that vary significantly in structure and cost, few financial transactions are as confusing as applying for and closing on a mortgage. Meanwhile, navigating the mortgage application process has significant consequences on household financial security, as a mortgage is typically a household’s largest credit obligation. As such, mortgages remain a critical tool for households’ financial development. Access to homeownership and the appreciation of home equity accessed through a long-term mortgage have historically been key mechanisms for low- and middle-income households to accumulate financial assets (Joint Center for Housing Studies 2000). However, mortgages involve risks and can infringe upon other necessary expenditures in a household budget. Selecting an appropriate mortgage loan can lower one’s housing costs by tens of thousands of dollars over a 30 year loan, thereby improving the borrower’s financial circumstances.

The mortgage market changed substantially in the past decade. During the early 2000s, the number and range of home loan options available to consumers increased considerably (Quercia et al. 2004). The advent of subprime lending ushered in credit to higher-risk borrowers who were previously unable to obtain mortgage credit (Carswell 2009; Collins 2007; Hogarth and Hilgert 2002b). In the early 2000s, consumers often obtained loans through non-bank institutions, including national commercial lenders that relied on third-party mortgage brokers to solicit borrowers and complete loan transactions (Quercia et al. 2004). During the late 2000s, the mortgage market contracted sharply due to slumping housing values and lax lending policies. The rapid expansion and subsequent collapse of the mortgage and housing markets continues to spur vigorous debate over consumers’ ability to navigate the mortgage market and whether some lending institutions and loan products are in borrowers’ best interests (Government Accountability Office 2004). Of primary concern tend to be borrowers who are more vulnerable due to a lack of knowledge of and experience in the mortgage market.

Despite a large literature on home mortgage markets, few studies have explored mortgage applicants’ behavior during the application process. This study seeks to contribute to this subset of the literature. To this end, this paper examines the relationship between demographic characteristics of applicants and nearby residents and the rates at which refinance mortgage loan applicants submit incomplete applications, withdraw applications before the lender makes a credit decision, reject lender approved loan offers, and receive mortgages with high interest rates. This analysis uses data on refinance mortgage loans as reported under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA) in 2005 aggregated to the Census tract level, combined with education, age, and homeownership rates from the 2000 Census. Mortgage application behavior may serve as an indicator of one’s level of financial capability.

Refinance loans are a particularly important segment of the market to study for several reasons. First, because these borrowers remain in their current home, the mortgage is not tied to a home sale. Second, the refinance market generally has a wide array of lenders, brokers, and credit unions offering products in almost all markets. Third, refinance products vary widely in terms, fees, interest rates, and one’s ability to finance more than the existing loan in order to ‘cash out’ home equity (at least in periods of rising home values as evidenced in 2005). Lee and Hogarth (2000) suggested that most refinance loan applicants shop or search for more than one lender and, at least relative to applicants for home purchase loans, may engage in more deliberate application processes.

Another reason for studying behavior in mortgage markets rests in state and federal policymakers’ long-standing commitment to publically subsidized education and counseling, presumably as a remedy to consumer information failures. Pre- and post-purchase homeownership education and counseling (HEC) includes pre-purchase classes and counseling that seek to prepare mortgage applicants for successful homeownership and post-purchase counseling that helps homeowners deal with setbacks [see Collins and O’Rourke (2011) for a review of this research]. However, few studies have assessed the extent to which consumers make mistakes or experience decision-making problems in the mortgage market. To the extent the behaviors studied in this paper—submitting an incomplete application, withdrawing an application before the lender makes a credit decision, rejecting an approved offer, and settling for a loan with a high interest rate—are considered financial mistakes, the results of this analysis provide additional insight into the potential need for effective consumer education. This analysis can also add to the body of knowledge on targeting HEC services.

Literature Review

In research on family financial security, the concepts of financial literacy and financial capability have become increasingly prevalent. “Financial literacy” is a commonly used term but arguably an imprecise one. It borrows from the reading literacy field in assuming that literacy can be taught, can be measured, and is a cumulative skillset that individuals can be expected to acquire as they move from infancy, through school, and into adulthood. Unlike reading literacy, however, no broadly accepted set of criteria for judging or testing financial literacy exists. The President’s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy (2009) defines financial literacy as, “the ability to use knowledge and skills to manage financial resources effectively for a lifetime of financial well-being.” There is an important debate in the financial literacy field concerning the extent to which financial literacy can and should be judged on the basis of knowledge or behavior. The President’s Advisory Council (2009) observed that financial literacy includes knowledge and actions in response to context. Similar to the case for reading literacy, which is advocated as necessary for participating successfully in society, financial literacy is a set of skills that informs decisions, affects behavior, and ultimately leads to beneficial financial outcomes. Nonetheless, studies on financial literacy generally focus on knowledge or skills, rather than on the outcomes of people’s choices in financial markets (Huston 2010; Remund 2010).

Knowledge Versus Behavior

Several previous studies analyzed either direct measures of financial knowledge or financial behaviors that can be reasonably associated with lower levels of financial capability (Borden et al. 2008; Fry et al. 2008; Gutter and Copur 2011; Hogarth and Hilgert 2002a; Lusardi and Mitchell 2007; Lusardi and Mitchell 2011; Lusardi and Tufano 2009; Mandell and Klein 2009; Peng et al. 2007). The mortgage market offers a unique opportunity to examine financial behavior, especially since HMDA data are widely available and track nearly all loan applications each year. Mortgage application decisions have not been a focus of the literature in the past, although this is a critical area in households’ financial lives. Mortgages represented almost 90 cents of ever $1 of an average household’s total debt obligations in 2004 (Crook and Hochguertel 2007). Thus, this is a domain of financial behavior that has profound implications for consumers. Importantly, past research indicates that calculating and comparing interest rates, core tasks in the refinance decision, are particularly challenging for many consumers (Campbell 2006; Lusardi and Tufano 2009; Moore 2003; Stango and Zinman 2011). Given the potential costs and the long-term nature of mortgage contracts, a consumer’s behavior in the mortgage market is arguably one of the most important contexts in which differences in financial literacy or capability may become observable in terms of actual behavior.

Mortgage Application and Search

Traditional economic theory suggests that consumers search for mortgage loan options by reviewing available information on price and other features. Consumers are generally expected to search for and process information up to the point at which the marginal cost of acquiring and processing further information equals the marginal benefit of that information for making a decision (Stigler 1961). However, much of this theory is based on consumers’ ability to obtain complete information. Information in the mortgage market tends to be heterogeneous across loan types and involves technical terms and calculations of the long-term time value of money. Searching for a mortgage requires consumers to incur the costs of learning about types of loans and loan terms, or paying a specialist for such advice. Even consumers who seek out advice may be misled. All too common is the story of a borrower who signs a mortgage contract that a mortgage broker promoted based on the broker’s own financial incentives rather than on the borrower’s interests. The mortgage market may be an example of a market in which consumers have access to weak forms of information during the search process (Gibler and Nelson 2003). In such markets producers have fewer incentives to compete on the positive attributes of a product. Consumer welfare can be reduced, since these markets may not allocate products efficiently to consumers (Beales et al. 1981). Even in relatively competitive non-concentrated lending markets, the extent to which consumers lack information (or the ability to process available information) affects mortgage lender’ ability to exert market power and earn supra-normal profits (Inderst 2005).

Few studies have examined consumers’ mortgage search behaviors in either the refinance or home purchase markets. Lee and Hogarth (1999, 2000) analyzed mortgage borrowers’ shopping behavior using self-reported survey data. The authors’ found wide variations in consumers’ search behaviors. For instance, 11% of mortgage borrowers reported that they did no shopping for a mortgage, and 26% reported that they compared multiple loan products (Lee and Hogarth 1999, 2000). The authors found that borrowers with more education conducted wider searches, and that borrowers who expected to be denied for a loan engaged in more limited searches (Lee and Hogarth 2000). Campbell (2006) estimated that during the late 1990s and early 2000s, between 36 and 45% of households had mortgages with interest rates at least 1.5 percentage points greater than the available rate. Avery et al. (2005) provided one of the most comprehensive analyses of HMDA data on the denial of loan applications, but the authors did not examine incomplete, withdrawn, or rejected applications. Calem et al. (2004) also focused on mortgage application denial rates using tract-level variables from the 2000 Census, including the percentage of the population over the age of 25 with a college degree. More recently, Ding et al. (2008) examined HMDA data for the Atlanta metropolitan area. They found that Census tracts with lower mean incomes and higher proportions of minority loan applicants tend to have loans with higher interest rates; the authors did not examine incomplete, withdrawn, or rejected loan applications.

Potential Variation in Behavior by Demographic and Socio-Economic Factors

Russo et al. (1986) posited that consumers engage in three activities when searching for a product or service: (1) collection, (2) computation, and (3) comprehension. The last activity is dependent on the consumer’s ability to process information, relative to other information, and use the information to make a decision. The ability to comprehend information varies according to the consumer’s knowledge and cognitive capacity. This comprehension stage is best managed by better educated and higher earning consumers, who tend to be the most aggressive in collecting information and more adept at computation (Crosby and Taylor 1981). Prior studies found strong associations among income, education, race, language, age, and other factors and consumers’ performance on a variety of financial literacy measures (Hilgert et al. 2003; Lusardi and Mitchell 2007).

Consumers from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face a number of informational disadvantages. Financial knowledge measures tend to be lower for lower-income consumers (Agnew and Szykman 2005; Bernheim 1998; Lusardi and Mitchell 2011; Mandell 2004). Understanding how interest is charged tends to be a particular area of weakness (Moore 2003). Bucks and Pence (2008) found that low-income mortgage borrowers with adjustable rate mortgages were the most likely to underestimate how much the interest rate on their loan could change. The authors found that low-income borrowers were 28% more likely to be unaware of their interest rate than higher income borrowers. Furthermore, the authors concluded that a lack of education exacerbates this problem. Low-income consumers with less than a college degree were among the least informed about the terms of their mortgages. Formal education may be an important predictor of how loan applicants search for and obtain mortgages. Higher levels of education may facilitate both greater searching and applicants’ comprehension of loan options.

Of course, formal education is not the only indicator of financial capability and comprehension. Consumers may rely on external sources of information during the mortgage search process, including family and friends. Some consumers may also obtain information from brochures and other sources (Beales et al. 1981). For mortgage applicants, an important external source of information may be neighbors who own homes. Given that neighborhoods tend to be homogenous along housing and household types, nearby homeowners experiences’ with refinancing a mortgage may influence their neighbors’ mortgage shopping behaviors—neighbors may serve as a “check in” to verify loan terms or alternatives. Loan applicants in Census tracts with greater proportions of homeowners are more likely to have access to informal information and advice relative to refinance mortgage loan applicants in areas with lower rates of homeownership. Because homeownership rates are correlated with socioeconomic status, controlling for income, education, and other factors will be important in order to isolate the effects of homeownership as a proxy for the prevalence of informal advice.

One category of loan applicant worthy of particular consideration is the elderly, who are often cited as one population victimized by predatory mortgage loans that they did not understand and that were pushed upon them by an aggressive lender or broker (Government Accountability Office 2004). Past research indicates that older consumers have not been immune from increasing mortgage debt, and that the bankruptcy rate has increased quickly among this group (Lee et al. 2007). One may expect that older homeowners would have an advantage in mortgage markets given their longer tenure as homeowners and the potential for more extensive experience in the home mortgage market. However, the nature of the mortgage market, with its wide array of loan types and lending institutions, provides few opportunities for applied learning over time. In fact, Bucks and Pence (2008) suggested that seniors “are substantially more likely not to know their mortgage terms,” which could be a signal of financial literacy failures (p. 227). The authors show that 60% of borrowers aged 65 or older do not know the details of their mortgage, compared with 30% of younger borrowers. Other studies indicated that older borrowers are more likely to have lessened cognitive abilities (Christelis et al. 2010; Korniotis and Kumar 2007, 2008). Older individuals also appeared more prone to making financial mistakes in credit markets by failing to use and pay off credit optimally (Agarwal et al. 2007).

Lower financial literacy may not impede consumers from refinance mortgages, but it may make the process of shopping for a loan, assimilating information, and understanding alternatives more costly and time consuming. Borrowers who fail to fully process and understand their mortgage terms may take out higher cost mortgages than they otherwise could have qualified for (Lax et al. 2004; Woodward 2003).

Method

Data

Each year the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (www.ffiec.gov) releases the HMDA database, which documents loan applications recorded by regulated mortgage lenders. Previous studies have used HMDA data to examine mortgage origination and denial patterns, trends in lending by type of financial institution, and general trends in loan volumes and borrower characteristics. Included in these data are several measures that are rarely cited in the literature: applicants who submit incomplete applications as determined by lending institutions, applicants who withdraw their applications before receiving a credit decision, and applicants who reject approved loan offers. In 2004, HMDA began reporting the rate spread between each loan’s annual percentage rate (APR) and the 10-year Treasury rate, though only for loans that were approved and originated and only if the spread was at least 300 basis points. This analysis uses HMDA data for refinance loan applications submitted in 2005 from 50 states aggregated at the Census tract level.

The analysis was conducted only on first lien refinance mortgage loans. First lien loans are distinct from second (or third and so on) liens in that the lender for the first lien loan has the first priority in terms of collateral in the event of default. Many borrowers have only one loan (the first). If they hold second or higher lien loans, these loans tend to be much smaller in size than the first lien loan. First lien loans are more likely to be a refinance for term or rate, although many include ‘cash-out’ provisions to convert home equity into current consumption or to consolidate debt. Applicants seeking home purchase loans were excluded because these borrowers are under time pressures that are unobservable and may contribute to differential loan search and application behaviors. Applicants for home improvement mortgages were also excluded because these loans vary significantly, from small loans for home repairs to large loans for extensive rehabilitation. Overall, refinance loans represent a more discretionary segment of the mortgage market. Applicants for refinance loans face less time pressure, have greater opportunities to shop and search, and have at least some previous experience with mortgages.

Aggregating the HMDA data by Census tract accomplished several functions. First, measures of education are not available through the HMDA data, and the closest available proxy was mean Census tract levels of education. By aggregating the data, the dependent and independent variables were measured at the same unit of analysis. Second, the HMDA dataset at the loan-level is quite large, and using a loan-level dataset is computationally intensive. Using data aggregated by Census tract created a more manageable dataset. Finally, examining data aggregated by geographic area reduced the high degree of correlation across mortgage applicant characteristics. The central tendencies of race, income, education, and credit status are less correlated by Census tract than within individuals (for a discussion, see Bell 2007). Clearly, the HMDA-based means for loan applicants are more precise estimates than the Census-based means for all households. This approach seems more likely to find a null effect using more dispersed 2000 Census variables than the more focused 2005 HMDA variables.

HMDA regulations require lenders to report loan applications in Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs). Some lenders also submit loan records for rural, non-metropolitan areas. To eliminate any bias associated with lenders’ reporting decisions, non-metropolitan area tract-loan type combinations were dropped from the analysis, leaving 379 MSAs. In addition, the analysis is first presented for all tracts and then only for tracts with at least 30 loan applications in the HMDA data. The mean number of applications per tract was 173, with only 5% of tracts having fewer than 30. Since the outcome variables depend on loan applications as a denominator, tracts with small numbers of applications could bias the analysis through large proportional values. Also, these low volume tracts are likely located in areas with few owner-occupied homes, and they may therefore be unrepresentative of the context of the typical mortgage transaction.

The resulting dataset of 52,532 Census tracts from 50 states was matched with Census tract variables for the education level of residents aged 25 or older, the share of owner-occupied homes, and the share of households headed by individuals aged 65 or older. The final dataset represents more than 11.6 million loan applications that were submitted in 2005. Table 1 displays the number of loan applications by state, including each state’s mean rate of loan applications that were incomplete, withdrawn, or rejected. The significant variations across states highlight the need to control for unobserved differences across states in the analysis.

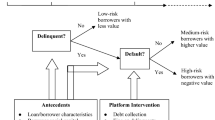

The Mortgage Application Process

Figure 1 displays an idealized flow of mortgage applications through the application process. This figure was created using Appendix A of the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council’s (2010) A Guide To HMDA Reporting: Getting It Right!, which specifies how lenders should code loan application actions in the HMDA database. The timing of other decision points in Fig. 1 could deviate slightly from what is depicted in a small number of cases, as only the codes lenders enter into the database are observed. However, the reporting requirements under HMDA are highly prescriptive, resulting in standardized information.

When a loan applicant submits a mortgage application, the lender first reviews the application package to see whether the application is complete and a credit decision can be made. The application package may include information on the property to be refinanced, such as land titles, deeds, liens and appraisals, as well as information on the borrower’s ability to pay, such as account statements, paystubs, and credit reports. If the application is incomplete, the lender has two options. The lender can send a notice of incompleteness to the applicant under section 202.9(c)(2) of Regulation B—Equal Credit Opportunity that specifies the information needed, designates a reasonable time period for the applicant to provide the information, and informs the applicant that the failure to provide the information will result in no further consideration being given to the application. Should the applicant fail to supply the necessary information within the specified timeframe, the lender codes the application as closed for incompleteness. Six percent of applications in the dataset were closed for incompleteness as shown in Fig. 1. Alternatively, the lender can outright deny an incomplete application, in which case the application is coded as denied. Because regulators focus so intently on differentials in loan denials by race and income, lenders have a strong incentive to send out the letter of incompleteness and wait for a response rather than denying an incomplete application outright. It is possible that lenders may differentially pursue denial versus incomplete designations by loan applicant income or race; however, due to regulatory oversight such behavior would be closely scrutinized by regulators.

The mean rate of applicants submitting incomplete mortgage applications in the tract is expected to be positively associated with higher tract-level means of non-white and Hispanic/Latino applicants, and negatively associated with higher tract mean rates of college completion, homeownership, applicant income, and households headed by individuals aged 65 or older. Submitting partial applications incurs the time costs of completing paperwork and gathering documents, as well as non-refundable application fees. The rate of applicants in a tract submitting incomplete applications should provide an indication of the prevalence of people failing to navigate the mortgage application process and one potential ‘mistake’ that signals a failure of financial capability. The potential for lenders to differentially code a loan application as incomplete or withdrawn complicates this measure, however.

Among complete loan applications, applications that applicants withdrew before the lender made a credit decision were coded as withdrawn in the HMDA database. Nineteen percent of complete applications were withdrawn by applicants’ express withdrawal in the form of a formal notification before the lender made a credit decision. Whereas incomplete applications are defined by the lender, withdrawn applications result from applicants’ actions. This outcome therefore seems to be a more precise indicator of behavior than the incomplete variable. Consumers may shop multiple lenders and submit several applications in order to explore terms and pricing. Given the costs of this process, formally withdrawing an application—which requires the applicant to send a written letter to the lender—is an inefficient application strategy.

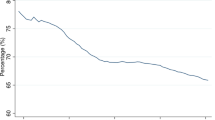

Applicants may withdraw because they cannot find or are unwilling to provide information needed by the lender, or if they decide to no longer pursue a loan. Withdrawing an application ends the application process and may help the applicant avoid additional fees such as those incurred for a credit report or an appraisal, but the time and money spent on submitting the application are lost. Again, the decision to withdraw an application could be due to a change in circumstances, but given the upfront costs of completing the application, it would be reasonable to wait for the lender’s decision. An alternative interpretation of the decision to withdraw an application rests in the possibility that some borrowers may discover they will not be approved, and then decide to pull an application rather than be subjected to the emotional toll of being denied. However, federal regulations require lenders to code an application as denied if such a decision was made. Another possibility is that mortgage borrowers who did not pay fees to lock in a specific interest rate feared that interest rates were rising and were no longer in the market to refinance. During 2005, interest rates stayed within a range of 5.5–6.5 for a 30-year fixed rate mortgage. Given this minimal variation (see Fig. 2), this is an unlikely explanation for the period analyzed. The mean rate of applicants withdrawing mortgage applications in the tract is expected to be positively associated with higher tract-level means of non-white and Hispanic/Latino applicants, and negatively associated with higher tract mean rates of college completion, homeownership, applicant income, and households headed by individuals aged 65 or older.

Market trends in 30-year fixed-rate mortgage interest rates. Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation’s (Freddie Mac) Weekly Primary Mortgage Market Survey (PMMS), Average Values. Data: http://www.freddiemac.com/dlink/html/PMMS/display/PMMSOutputYr.jsp

Among loans for which the lender accepted the application, 16% of loans were rejected by the applicant. Rejecting an approved loan offer is an applicant-driven decision in which a complete application is submitted and fully approved by the lender. The applicant then rejects the lender’s approval and does not close on the loan. Some refinance applicants who rejected a specific approved offer initially submitted multiple applications and then selected the best approved offer, thereby rejecting the other offers, or decided not to take out any loan at all. There are costs for loan applicants to reach this stage in the process; searching among terms and rates before submitting an application appears to be more efficient. The mean rate of applicants rejecting mortgage applications in the tract is expected to positively associated with higher tract-level means of non-white and Hispanic/Latino applicants, and negatively associated with higher tract mean rates of college completion, homeownership, applicant income, and households headed by individuals aged 65 or older.

In the HMDA database, lenders do not report actual mortgage interest rates, but rather the difference (or spread) between a mortgage’s APR and the benchmark rate. Interest rate spreads are only provided for those loan applications that were approved, originated, and had a rate spread relative to the Treasury 10-year benchmark rate of at least 300 basis points (the same as 3 percentage points). Thus, approved loans with a rate spread reported in HMDA can all be considered high rate loans. Among the loans that were originated, 28% of loans were coded as having a high rate spread. As financial capability increases, borrowers who are in the high cost mortgage market may become savvier in searching among high cost loans and engage in more searching and shopping. Thus, the mean interest rate spread among loans where interest rates are reported is hypothesized to be negatively associated with indicators of financial capability. The mean interest rate spread for borrowers of mortgage applications in the tract is expected to be positively associated with higher tract-level rates of non-white and Hispanic/Latino applicants, and negatively associated with higher tract mean rates of college completion, homeownership, applicant income, and households headed by individuals aged 65 or older.

Statistical Methods

Each outcome variable had the same basic specification with variations in fixed effects and standard errors:

where Y t took the form or four distinct dependent variables summarized as the mean of tract, t. First, Y t was defined as the mean rate of first lien refinance applications in the HMDA database that the lender labeled as closed for incompleteness (after sending the notice of incompleteness and receiving no response from the borrower within the given timeframe). Second, Y t was defined as the tract mean rate of all first lien refinance applications that were coded as withdrawn because the applicant formally withdrew the application before the lender made a credit decision. Third, Y t was defined as the tract mean rate of all first lien refinance applications that were approved by the lender but then rejected by the borrower. Finally, Y t was defined as the tract mean interest rate spread to the benchmark Treasury rate for originated high-cost first lien refinance loans (recall the rate is only reported for loans with high rates, so this is a mean conditional on having an interest rate at least 300 basis points above the Treasury benchmark).

Independent variables used in the analysis include β1, which is the tract mean loan applicant income for all first lien refinance applications reported in the HMDA data. Next, β2 is the tract mean rate of all first lien refinance loan applications in the HMDA data submitted by a loan applicant in which the lender reported a race but that race was not White or Caucasian. β3 is the tract mean rate of all first lien refinance loan applications in the HMDA data submitted by a loan applicant where the lender reported race/ethnicity and the applicant was labeled as Hispanic/Latino. β4 is the tract mean rate of population over age 25 reported to have completed a four-year college degree in the 2000 decennial Census. β5 is the tract mean rate of the population reporting to be at least age 65 in the 2000 decennial Census. β6 is the tract mean rate of households reporting owning their own home in the 2000 decennial Census. β7 is used only for the specification of the final model where Y t is defined as the tract mean interest rate spread to the benchmark Treasury rate for high-cost loans. Based on prior research (Calem et al. 2004) this provides a reasonable proxy for tract level credit quality. The indicator γ was used for one set of estimations per model to control for the potential for unobserved state differences in economic conditions or policies regulating mortgage applications as an additional robustness check. Likewise, standard errors, εmsa, were alternately estimated clustering at the MSA level anticipating correlated variations within related housing markets. These estimations were included as a robustness check in one set of models. All standard errors were corrected for heterogeneity using Huber-White ‘robust’ estimates.

All models were estimated using ordinary least squares (OLS) specifications. State fixed effects were included in selected models as noted, but the coefficients for each state were not included in the tables for clarity of presentation. Additional specifications using Tobit, Logit, and an OLS with log–log transformations generated similar results. Similar specifications using MSA or county fixed effects did not alter the results. Clustering standard errors at either the state or MSA levels produced similar results, but MSA clustering was retained as a better approximation of local housing markets. Checks for multicollinearity using variance inflation factors also yielded results within acceptable bounds.

Table 2 displays summary statistics, and Table 3 shows correlations across variables. The means for larger applicant volume tracts and all tracts, including approximately 3,000 tracts with fewer than 30 loan applicants in 2005, are quite different for some variables, especially for homeownership and race. The correlation table suggests some caution regarding collinear relationships between education and income, as should be expected.

Results

The results of each series of regressions are displayed in Tables 4, 5, 6, and 7. The results suggest that tract characteristics are related to the dependent variables as might be expected in most cases and that with some caveats mortgage application behavior may be a weak indicator of financial capability yet potentially useful for financial education and counseling initiatives.

Incomplete Applications

Table 4 presents the results for the rate of incomplete mortgage applications by tract. As the share of the tract population aged 25 or older with a bachelor’s degree increased, the proportion of incomplete applications declined, although these results dissipated when including state fixed effects. Tracts with higher mean incomes and more Hispanic applicants were associated with more incomplete applications, although these results again were not robust to both fixed effects and clustering errors at the MSA level, which suggests that other unobservable factors such as market trends or regulatory environments play a role in this behavior. A greater share of homeowners was associated with a lower rate of incomplete loan applications but again the effect did not withstand fixed effects and MSA clustered errors. Only the share of households aged 65 or older was a strong predictor, suggesting fewer incomplete applications in tracts with more elderly householders. Perhaps applicants in these ‘older’ tracts may learn from their neighbors to be more responsive to the lender’s notice of incompleteness. More likely, because this variable is a crude measure of applicants’ age, it likely captures other unobserved dynamics in tracts with older and more established residents.

Withdrawn Applications

Table 5 presents the results for the rate of mortgage applications by tract that are formally withdrawn by the applicant. The relationship between college education rates and the rate of withdrawn applications was strong and negative, including in the models with fixed effects. As the proportion of the tract population with a college education increases, the occurrence of withdrawn applications declined. This may suggest that withdrawn loans signal costly or inefficient application strategies. The share of applicants of a non-white race was not a statistically significant predictor of withdrawn applications. As the mean tract-level loan applicant income decreases, the rate of withdrawn applications increased. The variable for the tract rate of Hispanic loan applicants was also negatively associated with the rate of withdrawn applications, although it was small in magnitude. This was the opposite of what might be expected since Hispanics are less experienced in the U.S. mortgage market. In addition, given that language and cultural barriers are more likely for Hispanic populations, the submission of a written withdrawal letter to a lender might be expected to be less likely. However, a greater share of Hispanic applicants may also signal that having more neighbors of a similar ethnic background might facilitate certain information sharing about mortgage application strategies. The share of owner-occupied homes was negatively related to withdrawn loan applications, perhaps suggesting another form of some intra-neighborhood knowledge sharing among experienced homeowners. A greater share of older residents in the tract was also associated with a lower rate of withdrawn loan applications, which could be associated with relatively more experience with mortgage markets. These results are generally as hypothesized and support the notion that withdrawn applications are a signal for loan applicants struggling with application processes.

Approved Applications Rejected by the Borrower

Table 6 presents the results for the rate of approved mortgage applications rejected by the loan applicant. If the most financially literate borrowers were more selective prior to submitting applications and only apply for the most attractive loan products that they know they will agree to in advance, rejecting a loan offer could signal an inefficient loan search strategy. Since completing a mortgage application incurs time costs and application fees, shopping prior to applying for a mortgage loan may be a more time and cost effective approach for a first lien refinance loan applicant. Table 6 shows that as the share of college graduates in the tract increased, the share of rejected loan offers declined, consistent with financial capability being associated with lower rates of rejecting loan offers. Tract rate of non-white loan applicants was positively related to more rejections of loan offers, a result that was robust across models. Tract mean applicant income had a small and negative relationship with rejecting approved loan offers, although the effect dissipated with fixed effects. The tract mean rate of Hispanic applicants had a negative relationship to rejections, although this effect did not withstand fixed effects and clustering. The share of owner-occupied homes in the tract was negatively associated with rejected loan offers; higher tract homeownership rates were associated with lower rates of borrowers rejecting lender offers. To the extent more homeowners in a tract represents more neighbors with experiences in the mortgage market, this may indicate that applicants have the advantage of checking with neighbors and only applying for suitable loans. An increase in the share of the population aged 65 or older was associated with an increase in loan offer rejections. These results suggest there are differences in application strategies related to education, race, ownership rates and age. Rejecting an approved loan offer may serve as another mortgage market behavior that is related to lower levels of financial capability and a signal of problems in the mortgage market.

Interest Rate Spreads for High-Cost Originated Loans

Interest rates for high cost loans, defined as loans with annual interest rates at least 3 percentage points greater than a 10-year Treasury note (the only rates reported in the HMDA data and a fair approximation for subprime loans) are another potential indicator of financial behavior among a subset of borrowers shopping for higher-cost mortgages. Table 7 presents the results of the models for the mean interest rate spread by tract outcome variable, adding a control for tract mean denial rate as a proxy for credit quality. As the share of college graduates in the tract increased by 10 percentage points, the mean interest rate spread decreased by about 4 basis points (where 100 basis points = 1 percentage point). This small effect was approximately one-tenth of a standard deviation, but it remained statistically significant after controlling for other factors and larger than the coefficients for other variables in the model. By comparison, a 10 percentage point greater share of non-white loan applicants in the tract was associated with about a 1 basis points greater mean interest rate spread. The tract share of loan applicants of Hispanic ethnicity had similarly small effects. As the share of the population aged 65 or older in the tract increased mean interest rate spread also increased. Because interest rates are determined by unobserved risk-based factors that may be correlated with race, income, and Census tract location, the interpretation of this model should be subject to caution. Controlling for denial rates in the tract provides a significant and relatively large estimate in the expected direction, but this is unlikely to fully capture differences in borrower and collateral risks in the tract.

Discussion

Based on a tract-level analysis of 2005 HMDA data for first lien refinance mortgage applications paired with 2000 Census data there is some evidence that several demographic factors are associated with problematic mortgage application behaviors. Withdrawn and rejected applications offer perhaps more useful measures of behaviors related to financial capability among mortgage loan consumers than incomplete loans. Applicants in tracts with particular demographic characteristics, including higher incomes and greater educational attainment, appear better able to engage in more efficient mortgage searches.

This study makes several contributions. First, the use of incomplete, withdrawn, and rejected loan applications in the HMDA data is a potentially useful way to measure household financial behavior in future studies. This analysis offers researchers an illustration of how mortgage application data might be better used in the study of household finance. HMDA data are typically used only to monitor loan approvals and denials. The incomplete, withdrawn, and approved but rejected variables have not been widely employed in the literature. This analysis is a preliminary attempt to derive informational value from these variables. Second, this study explicitly tests proxies for financial capability on loan application outcomes, finding small but statistically significant effects, generally in predicted directions consistent with prior studies. Third, it appears that some groups of loan applicants are shopping for refinance mortgages before the loan application stage, while others are ‘sampling’ loan applications. Applicants may be engaging in inefficient application strategies by withdrawing mortgage applications and rejecting approved refinance offers from lenders after investing resources into an application that does not result in a new loan. Future research using these data at the loan application level, or aggregated to alternative levels of geography, may yield useful findings. These analyses could also be repeated for other classes of loans or explore these trends in the data after activity in the mortgage market peaked in 2007.

Several caveats are in order. First, these data are analyzed at the Census tract level. This offers certain advantages in analysis and perhaps is useful for considering geographically targeted interventions, but this strategy may not provide insights about individual borrower behavior. Second, HMDA data only capture loan applicants. Prior studies (for example, Campbell 2006) suggest that low-income, minority, and lower educated mortgage borrowers are less likely to know their loan terms and to refinance when they might benefit from doing so. This study only captures those applicants who are sophisticated enough to apply for a mortgage. The bias introduced by this fact does not seem likely to result in an overestimation of effects on the outcomes measures among each tract level characteristic, however, and the results remain instructive a least as a lower bound.

Conclusion

Searching for and processing information about mortgage options requires effort. Clearly, a lack of financial capability can harm consumers when they apply for and take out home mortgages that they do not understand or cannot sustain. Understanding the extent of consumer financial capability challenges in the mortgage market is important to the policy debate about regulating lending and other forms of credit, as well as to discussion about how and when to support consumer education and counseling efforts. To the extent problems with loan applications among vulnerable populations present a public policy problem, education, counseling, and disclosures are potential responses. Pre-application education and counseling, clearer pre-application and pending application disclosures, and the availability of advice may all be remedies that could aid less financially capable applicants during the mortgage search process. Greater attention to education and counseling earlier in the loan application process may be warranted, especially for applicants in the mortgage refinance market, rather than focusing exclusively on first-time home purchase loan applicants. The results suggest that educators and counselors might incorporate information from HMDA on rejected and withdrawn applications from the prior year as they design and target services.

References

Agarwal, S., Driscoll, J. C., Gabaix, X., & Laibson, D. (2007). The age of reason: Financial decisions over the lifecycle (NBER working paper series no. 13191). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Agnew, J., & Szykman, L. R. (2005). Asset allocation and information overload: The influence of information display, asset choice and investor experience. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 6(2), 57–70.

Avery, R. B., Canner, G. B., & Cook, R. E. (2005). New information reported under HMDA and its application in fair lending enforcement. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 91(3), 344–394.

Beales, H., Craswell, R., & Salop, S. C. (1981). The efficient regulation of consumer information. Journal of Law and Economics, 24(3), 491–539.

Bell, J. (2007). Using census tract demographics as proxies for individual demographics in analysis using the knowledge networks internet panel: Draft report. National Center for Environmental Economics. Retrieved from http://yosemite.epa.gov/ee/epa/eerm.nsf/vwAN/EE-0536-01.pdf/$file/EE-0536-01.pdf.

Bernheim, B. D. (1998). Financial illiteracy, education, and retirement saving (Pension Wharton School Pension Research Council working paper no. 96-7). Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania.

Borden, L. M., Lee, S., Serido, J., & Collins, D. (2008). Changing college students’ financial knowledge, attitudes, and behavior through seminar participation. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29(1), 23–40.

Bucks, B., & Pence, K. (2008). Do borrowers know their mortgage terms? Journal of Urban Economics, 64(2), 218–233.

Calem, P. S., Gillen, K., & Wachter, S. (2004). The neighborhood distribution of subprime mortgage lending. The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 29(4), 393–410.

Campbell, J. Y. (2006). Household finance. The Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1553–1604.

Carswell, A. (2009). Does housing counseling change consumer financial behaviors? Evidence from Philadelphia. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 30(4), 339–356.

Christelis, D., Jappelli, T., & Padula, M. (2010). Cognitive abilities and portfolio choice. European Economic Review, 54(1), 18–38.

Collins, J. M. (2007). Exploring the design of financial counseling for mortgage borrowers in default. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28(2), 207–226.

Collins, J. M., & O’Rourke, C. (2011). Homeownership education and counseling: Do we know what works? (Research Institute for Housing America research paper no. 1102). Retrieved from http://www.housingamerica.org/RIHA/RIHA/Publications/76378_10554_Research_RIHA_Collins_Report.pdf.

Crook, J., & Hochguertel, S. (2007). US and European household debt and credit constraints: Comparative micro evidence from the last 15 years (Tinbergen Institute, discussion paper no. 07/3). The Netherlands.

Crosby, L. A., & Taylor, J. R. (1981). Effects of consumer information and education on cognition and choice. Journal of Consumer Research, 8(1), 43–56.

Ding, L., Ratcliffe, J., Stegman, M. A., & Quercia, R. G. (2008). Neighborhood patterns of high-cost lending: The case of Atlanta. Journal of Affordable Housing, 17(3), 193–217.

Federal Financial Institutions Examination Counsel. (2010). A guide to HMDA reporting: Getting it right! Retrieved from http://www.ffiec.gov/hmda/pdf/2010guide.pdf.

Fry, T. R. L., Mihajilo, S., Russell, R., & Brooks, R. (2008). The factors influencing saving in a matched savings program: Goals, knowledge of payment instruments, and other behavior. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 29(2), 234–250.

Gibler, K. M., & Nelson, S. L. (2003). Consumer behavior applications to real estate education. Journal of Real Estate Practice and Education, 6(1), 63–83.

Government Accountability Office. (2004). Consumer protection: Federal and state agencies face challenges in combating predatory lending (GAO-04-280). Washington DC: Government Accountability Office.

Gutter, M., & Copur, Z. (2011). Financial behaviors and financial well-being of college students: Evidence from a national survey. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. doi:10.1007/s10834-011-9255-2.

Hilgert, M. A., Hogarth, J. M., & Beverly, S. G. (2003). Household financial management: The connection between knowledge and behavior. Federal Reserve Bulletin, 89(7), 309–322.

Hogarth, J. M., & Hilgert, M. A. (2002a). Financial knowledge, experience and learning preferences: Preliminary results from a new survey on financial literacy. Consumer Interest Annual, 48(1), 1–7.

Hogarth, J. M., & Hilgert, M. A. (2002b). A profile of consumers with high-rate home loans. Financial Counseling and Planning, 13(1), 15–34.

Huston, S. (2010). Measuring financial literacy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 296–316.

Inderst, R. (2005). Consumer lending when lenders are more sophisticated than households (CEPR discussion paper no. 5410). Retrieved from SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=893069.

Joint Center for Housing Studies. (2000). The state of the nation’s housing 2000. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Korniotis, G., & Kumar, A. (2007). Do older investors make better investment decisions? (McCombs School of Business working paper September). University of Texas at Austin.

Korniotis, G., & Kumar, A. (2008). Superior information or a psychological bias? A unified framework with cognitive abilities resolving three puzzles (working paper). Federal Reserve Board and University of Texas at Austin.

Lax, H., Manti, M., Raca, P., & Zorn, P. (2004). Subprime lending: An investigation of economic efficiency. Housing Policy Debate, 15, 533–572.

Lee, J., & Hogarth, J. M. (1999). Returns to information search: Consumer mortgage shopping decisions. Financial Counseling and Planning, 10(1), 49–66.

Lee, J., & Hogarth, J. M. (2000). Consumer information search for home mortgages: Who, what, how much and what else. Financial Services Review, 9(3), 277–293.

Lee, Y. G., Lown, J. M., & Sharpe, D. L. (2007). Predictors of holding consumer and mortgage debt among older Americans. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28, 305–320.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2007). Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implications for financial education. Business Economics, 42(1), 35–44.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011). Financial literacy and planning: Implications for retirement wellbeing (NBER working paper series no. 17078). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2009). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness (NBER working paper series no. 14808). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Mandell, L. (2004). Financial literacy: Are we improving?. Washington, DC: Jump$tart Coalition for Personal Financial Literacy.

Mandell, L., & Klein, L. S. (2009). The impact of financial literacy education on subsequent financial behavior. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 20(1), 16–24.

Moore, D. (2003). Survey of financial literacy in Washington State: Knowledge, behavior, attitudes, and experiences (technical report no. 03-39). Social and Economic Sciences Research Center, Washington State University.

Peng, T. M., Bartholomae, S., Fox, J. J., & Cravener, G. (2007). The impact of personal finance education delivered in high school and college courses. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28, 265–284.

President’s Advisory Council on Financial Literacy. (2009). 2008 Annual report to the president. Washington, DC: The Department of the Treasury.

Quercia, R. G., Stegman, M. A., & Davis, W. R. (2004). Assessing the impact of North Carolina’s predatory lending law. Housing Policy Debate, 15(3), 573–601.

Remund, D. (2010). Financial literacy explicated: The case for a clearer definition in an increasingly complex economy. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 276–295.

Russo, J. E., Staelin, R., Nolan, C. A., Russell, G. J., & Metcalf, B. L. (1986). Nutrition information in the supermarket. The Journal of Consumer Research, 13(1), 48–70.

Stango, V., & Zinman, J. (2011). Fuzzy math, disclosure regulation, and market outcomes: Evidence from Truth-in-Lending reform. Review of Financial Studies, 24(2), 506–534.

Stigler, G. J. (1961). The economics of information. Journal of Political Economy, 69(3), 213–225.

Woodward, S. (2003). Consumer confusion in the mortgage market. Sand Hill Econometrics research paper. Retrieved from http://www.sandhillecon.com/pdf/consumer_confusion.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Collins, J.M. Mortgage Mistakes? Demographic Factors Associated with Problematic Loan Application Behaviors. J Fam Econ Iss 32, 586–599 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9276-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9276-x