Abstract

Objectives

Negative interparental conflict is a consistent predictor of children’s functioning. In the current study, we examined conflict stimuli and children’s cognitive appraisals of their parents’ conflicts as predictors of children’s evaluations of simulated conflict.

Methods

A sample of 96 children aged 9–11 years (50 males) viewed brief videotaped depictions of a male and a female actor posing as a married couple enacting conflict scenarios. Children evaluated each actor’s behavior in each video on a continuum from good to bad. Trained coders coded the actors’ positivity and negativity in each video. Children’s cognitive appraisals of their own parents’ conflicts were assessed via questionnaire (e.g., self-blame appraisals). The positivity and negativity codes and children’s cognitive appraisals were tested as predictors of children’s evaluations, and cognitive appraisals were tested as moderators of associations between the codes and children’s evaluations.

Results

Codes reflecting greater negativity of either actor predicted worse child evaluations of both actors’ behavior (evaluations as more “bad”). Codes reflecting greater positivity of the actors generally predicted better evaluations of the actors’ behavior (evaluations of behavior as more “good”). Children’s cognitive appraisals moderated some of these associations. For example, low levels of the mother actor’s positivity (a lack of positivity) predicted worse child evaluations of the father actor for children who blamed themselves more for their parents’ conflict than for other children.

Conclusions

Results are discussed in terms of advancing knowledge of children’s cognitions regarding interparental conflict, and ultimately the implications of the results for children’s development and psychological adjustment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Exposure to destructive interparental conflict consistently predicts higher levels of psychological adjustment problems in children (Cummings and Davies 2010). Previous work has examined links between interparental conflict and several aspects of child functioning, including children’s cognitive appraisals of the frequency, intensity, and degree of resolution of interparental conflict, as well as children’s perceptions of threat and self-blame regarding interparental conflict (Grych et al. 2003). However, important questions remain about one particular aspect of children’s cognitions: How children evaluate parents’ conflict behavior. Extensive work has examined children’s long-term cognitive appraisals of interparental conflict (i.e., appraisals that are developed and maintained over time, reflecting many experiences with parents’ conflicts, such as appraisals of parents’ conflicts as frequent and intense). However, in order to obtain more concrete, specific understanding of children’s evaluations of interparental conflict, we need to advance knowledge of children’s immediate cognitive evaluations of discrete conflict episodes, as well as links between these evaluations and children’s long-term cognitive appraisals. Additional important questions include whether one parent’s positivity and negativity has implications for children’s evaluations of the other parent’s behavior, and whether these processes differ for mothers and fathers.

Providing an excellent foundation for examining children’s conflict evaluations, the cognitive-contextual framework emphasizes the role of children’s cognitions regarding interparental conflict in mediating interparental conflict-child functioning associations (Grych and Fincham 1990). Consistent with this framework, empirical work underscores the importance of children’s cognitions in accounting for interparental conflict’s links with children’s internalizing and externalizing problems (Grych et al. 2003). For example, children’s self-blame for interparental conflict predicts higher levels of internalizing and externalizing problems, and children’s perceptions of threat regarding interparental conflict predict higher levels of internalizing problems (Fosco and Grych 2008). Children’s threat perceptions also predict externalizing problems through a developmental cascade in which interparental conflict predicts higher levels of threat perceptions, which predict diminished self-efficacy, in turn predicting externalizing problems (Fosco and Feinberg 2015). In summary, it is clear that children’s cognitive appraisals of conflict play important roles in links between interparental conflict and child adjustment problems.

More broadly, our work draws on dynamic systems principles, which include an emphasis on developmental processes unfolding over different time scales (Lewis 2002), with shorter time scales nested within increasingly long time scales (Schermerhorn and Cummings 2008). Dynamic systems scholars have called for examination of relations between different time scales (Granic and Patterson 2006; Lewis 2002; Thelen 1995; Van Gelder and Port 1995), recognizing that processes unfolding over different time scales reflect distinct phenomena (Schermerhorn and Cummings 2008). Whereas the tests of the cognitive-contextual framework described above focused on children’s cognitions that are built up over extended periods of time and developed over the long-term, few studies have examined children’s immediate cognitions about interparental conflict. In one of the few studies to do so, Goeke-Morey et al. 2003 presented children with videotaped depictions of simulated interparental conflict and asked children to appraise the likelihood that the simulated interparental problems would be worked out later. Children appraised depictions of physical aggression and verbal negativity as least likely to be resolved. In addition, Goeke-Morey et al. 2007 presented children with videotaped endings of simulated interadult conflict, and asked children to assess the degree to which the conflicts were resolved. Children appraised videos portraying compromise as more resolved than apology endings, and appraised endings depicting apologies as more resolved than endings depicting withdrawal from conflict. Thus, although the evidence base is small, these studies suggest that immediate cognitive processes are relevant to advancing knowledge in this area. Identifying how children evaluate conflict behavior as good or bad is likely to be particularly informative regarding the aspects of conflict that pose the greatest challenges to children’s developing emotional, cognitive, and self-regulatory systems, and ultimately psychological outcomes. Moreover, an understanding of the connections between short- and long-term cognitive processes is needed to advance knowledge of these important developmental processes.

Previous theoretical work suggests the importance of both positive and negative interparental conflict behaviors as predictors of child functioning (Cummings and Davies 2002). Although relatively few empirical studies have examined how positive aspects of interparental conflict relate to child functioning, those that have done so have revealed that both positive and negative forms of interparental conflict are related to child functioning (e.g., Goodman et al. 1999; McCoy et al. 2009; McCoy et al. 2013). In one such study using parents’ diary reports of interparental conflict, Cummings et al. 2003 found constructive conflict tactics (calm discussion, support, and affection) predicted more positive emotions in children. Similarly, destructive conflict tactics (e.g., threats, insults, verbal and nonverbal hostility) predicted children’s negative emotions. In addition, a few studies have examined how positive and negative interparental conflict jointly contribute to child functioning (e.g., Zemp et al. 2016). Zemp et al. 2014 found that children whose parents had moderate to high levels of positive interactions and low levels of negative interactions had lower levels of adjustment problems than children whose parents had low levels of positive interactions and moderate levels of negative interactions. Together, these studies suggest that both positive and negative forms of interparental conflict are uniquely important to children.

Based on the existing literature, there may also be differences between mothers and fathers in associations between interparental positivity and negativity and children’s evaluations of conflict. Evidence of this is drawn from Goeke-Morey et al.’s (2003) study using interparental conflict videos. Whereas the behavior of the father actor that elicited the most negative emotional responses from children was physical aggression toward the spouse, the behaviors of the mother actor that elicited the most negative child emotional responses were threatening to leave the relationship and physical aggression toward an object. However, the behavior that elicited the most positive child emotion was the same for both the mother and the father actors, namely affection (Goeke-Morey et al. 2003). Other studies have also found similarities in the associations of mothers’ and fathers’ conflict behavior with child functioning (e.g., El-Sheikh et al. 2008). Another important question is whether one parent’s behavior influences children’s evaluations of the other parent. Such influence may be considerable, and it may differ for mothers and fathers.

The objectives of the current study were to examine children’s evaluations of adults’ conflict behavior to determine whether children’s long-held appraisals of their own parents’ conflicts have implications for children’s evaluations of conflict. We presented children with simulated interparental conflict videos and asked them to evaluate the extent to which the “parent” actors’ behavior during each video was “good” or “bad.” In addition, we coded the actors’ positivity and negativity in each video clip. We then tested for interactions between the coder ratings of positivity and negativity from each video and children’s cognitive appraisals of conflict as predictors of children’s evaluations of the actors’ behavior. Children’s immediate, or short-term, evaluations of conflict may depend on children’s long-standing cognitions about their parents’ conflict, a notion that is consistent with dynamic systems theory’s emphasis on interrelations among processes at different time scales (Schermerhorn and Cummings 2008). We hypothesized that children’s cognitive appraisals of their parents’ conflict (i.e., children’s appraisals of the frequency, intensity, and degree of resolution of their parents’ conflict, and children’s perceptions of threat and self-blame for their parents’ conflict) would predict their evaluations of the actors’ behavior, evidencing connections between long-term and immediate cognitive processes. That is, consistent with the cognitive-contextual framework (Grych and Fincham 1990), and based on findings that children’s cognitive appraisals of interparental conflict are linked with other aspects of children’s functioning (Grych et al. 2003), we hypothesized that more negative child appraisals of interparental conflict would predict worse evaluations of the actors’ behavior. In addition, we hypothesized these appraisals would moderate associations between coder ratings of positivity and negativity and children’s evaluations of the actors’ behavior. Specifically, we hypothesized that, for children with more negative appraisals of their parents’ conflict, higher levels of coder-rated actor negativity would predict worse child evaluations of that actor. Additionally, although we expected that coder ratings of high levels of negativity would predict children’s evaluations of an actor’s behavior as bad, and that coder ratings of high positivity would predict child evaluations of an actor’s behavior as good, it was less clear whether the positivity or negativity of one actor would predict children’s evaluations of the other actor. It is possible that children evaluate each actor independently. Alternatively, children may use one actor’s behavior as an indication of the degree to which the other actor is behaving in a helpful way. For example, if one actor cries, children may take that as an indication that the other actor was being unkind, leading them to evaluate that actor’s behavior as bad. However, the existing literature did not provide a sufficient basis to formulate specific hypotheses regarding such cross-partner associations between an actor’s positivity or negativity and children’s evaluations of the partner. Our analyses, thus, represent an initial step in examining these associations.

Method

Participants

The data were drawn from a larger study of 119 children, ages 9–11 years, and their parents living in the northeastern United States. To be eligible, children had to live with their married, biological parents, and children had to read at a 4th-grade level or higher. The sample was recruited from the community by sending letters to families with a child in the target age range, circulating study information in local schools, placing ads in newspapers and magazines, and posting flyers and holding booths in public places. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB). Informed consent was obtained from the mothers of all children who were included in the study, and 11-year-olds provided assent (per the IRB, younger children could not give assent, but we described the procedures to them and encouraged them to ask questions). Participants were paid for their time. Data were missing for 12 families because they did not complete the lab visit in which this task was completed, and data were missing from ten children due to technical difficulties. In addition, data from one child were omitted because the child had a significant developmental delay. This resulted in a final sample of 96 children.

Participating children (50 males, 45 females, one gender-neutral child) had a mean age of 10.58 years (SD = 0.89). Ninety-two percent of the children were identified as Caucasian, 6% as multiracial, 1% as American Indian or Alaska Native, and 1% as Asian. Two percent of mothers reported annual household incomes of $25,000 or less, 4.2% reported incomes of $25,001–$40,000, 9.4% reported incomes of $40,001–$65,000, 22.9% reported incomes of $65,001–$80,000, 59.4% reported incomes of at least $80,000, and 2.1% did not report income. Two percent of mothers had completed high school or a GED or less, 48.9% had completed at least some trade school and as much as a bachelor’s degree, 38.5% had completed a master’s degree, and 10.4% had completed a doctoral degree. The mean length of marriage was 14.49 years.

Procedure

The simulated interparental interaction videos were created by Dr. Mark Cummings and colleagues (Goeke-Morey et al. 2003). Each video segment depicted two actors (one male, one female) pretending to be a couple, enacting different ways of handling marital conflict situations. Each segment lasted ~5–15 s and was designed to portray one specific conflict tactic (e.g., verbal hostility) enacted by one of the actors (the focal actor) (see Goeke-Morey et al. 2003, for details). The non-focal actor was present in each segment, but exhibited little to no observable behavior or emotion. Two fictional interparental conflict scenarios provided background contexts for the video segments. One of the conflict scenarios involved the purchase of a new television and the other involved the couple’s house being messy.

The Videos Interview Task began with an experimenter giving a detailed verbal description of one of the interparental conflict scenarios, which provided the background story for the videos. Children were asked to pretend the actors in the videos were their parents. Children viewed 26 video segments, plus 2 practice segments. After each segment, children responded to the questions: (a) Did you think the way Dad acted was good or bad? and (b) Did you think the way Mom acted was good or bad? Responses were provided on a 5-point Likert scale with the response options of 0 (Really good), 1 (Good), 2 (In between good and bad), 3 (Bad), and 4 (Really bad).

Each video segment was coded by a team of trained undergraduate students, who were trained and supervised by a doctoral-level researcher. In each segment, positivity and negativity were coded separately for the mother and father actor on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (none; construct not present) to 4 (very high level of construct present). Positivity was operationally defined in terms of how positively the actor was behaving throughout the scene and disregarding negative or neutral behaviors; examples included working toward a healthy relationship, listening, compromising, and taking responsibility. Negativity was defined in terms of how negatively the actor was behaving throughout the scene and disregarding positive or neutral behaviors; examples included being antagonistic or overreacting, making sarcastic remarks, insulting the partner, as well as engaging in verbal hostility and/or physically aggressive behavior. Treating partners’ positivity and negativity as distinct constructs is supported by empirical findings in the literature on marital relationships (Gottman and Levenson 1992; 1999) and has more recently been incorporated into examinations of children’s functioning (Zemp et al. 2014). In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas were: Positivity of mother actor = 0.93; positivity of father actor = 0.94; negativity of mother actor = 0.96; negativity of father actor = 0.95.

Previous studies have made major contributions to knowledge of discrete interparental conflict tactics, mapping associations between many distinct conflict tactics and children’s responses (e.g., Cummings et al. 2003; Goeke-Morey et al. 2003). Rather than focusing on discrete conflict tactics in the current study, we focused on quantifying the degree of negativity and the degree of positivity of interparental behavior. This approach facilitated examination of a fuller range from low to high negativity and low to high positivity and their associations with children’s evaluations. Further, compared with previous studies using simulated conflict videos, a strength of the current approach is that each video was coded for each construct, so rather than having one (categorical) instantiation of each construct, we generated a continuous measure of each construct, which allowed us to determine the extent to which varying levels of the constructs predicted levels of child responses. In addition, approaches using coded observations of interparental conflict typically yield one code per construct per family, whereas we produced a code for each video for each construct, enabling us to use a repeated measures statistical approach, which has greater power.

Measures

Children’s appraisals of interparental conflict

Children provided reports of interparental conflict and their perceptions of threat and self-blame regarding interparental conflict using the Children’s Perceptions of Interparental Conflict Scale (CPIC; Grych et al. 1992). The CPIC consists of 48 items completed on a 3-point scale consisting of 0 (false), 1 (sort of true), and 2 (true), with higher scores reflecting higher levels of conflict, threat, and self-blame. The Conflict Properties subscale is a 16-item measure of conflict frequency, intensity, and resolution, and it includes such items as “My parents get really mad when they argue”. The 12-item Threat subscale assesses perceptions that conflict could escalate into worse problems, and it includes such items as “When my parents argue I worry that they might get divorced”. The 9-item Self-Blame subscale assesses the extent to which children feel they are to blame for their parents’ conflict, and it includes such items as “My parents blame me when they have arguments”. The CPIC has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Grych et al. 1992). Cronbach’s αs in this sample were 0.89 for Conflict Properties, 0.80 for Threat, and 0.74 for Self-Blame. Because the instructions ask children to indicate what they think or feel when their parents argue without specifying a time-frame within which children should report, this measure elicits information about children’s general long-term cognitions about their parents’ conflict. Moreover, many of the items include such wording as “never”, “usually”, and “often”, eliciting answers reflecting children’s long-term cognitions.

Data Analyses

Mixed models were computed in SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 24), with values of the codes for each of the 26 videos nested within child, children’s appraisals as between-subjects variables, and child evaluations of the actors as the dependent variables (with separate models for evaluations of the mother and father actors). We included all four codes in every model (positivity and negativity of each actor), with both actors’ codes from every video clip (as focal actor or partner) included in every model. Moreover, children’s evaluations of each actor were examined regardless of whether they were the focal actor or the partner in any given video clip. Inclusion of codes and evaluations of both the focal actor and the partner, reflecting greater variability in the data, allowed us to examine a wider slice of interparental relations. That is, this approach reflects typical interparental interactions, in that often one partner is speaking while the other partner is relatively quiet. Each CPIC variable was tested as a moderator in a separate model, while retaining all four codes in each model. Thus, each model included tests of first-order effects of the four codes, first-order effects of one CPIC variable per model, and their four possible interaction terms, for a total of six models: Two models that included CPIC Conflict Properties scores in addition to the four codes (one predicting evaluations of the father actor, one predicting evaluations of the mother actor), two models with CPIC Threat (father actor, mother actor), and two models with CPIC Self-blame (father actor, mother actor). Including tests of all four codes’ first-order effects and interaction effects within each model (as opposed to being computed in separate models) meant these tests were computed controlling for one another, making the tests more conservative and accurate and reducing the number of models computed. Simple slopes were evaluated only if the omnibus tests were significant. Results were not corrected for multiple comparisons. Four covariates were included in every model: Child gender, race, and age, and household socioeconomic status (SES). Independent variables and non-categorical covariates were mean-centered to facilitate interpretation.

We identified the best-fitting model to use in the analyses by comparing preliminary models’ fit using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC; Schwarz 1978), a relative fit index, with smaller BIC values indicating better fit. The best-fitting model had a random intercept and fixed slope, had an identity covariance matrix, and used restricted maximum likelihood (REML) to accommodate missing data.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptives and bivariate correlations among the coder ratings, CPIC scores, and children’s evaluations. The table is separated into two sections, one for coder ratings and one for other variables, to clarify that the intercorrelations among the coder ratings reflect the video stimuli and are not participant data. The coder ratings of the father actor’s positivity were not significantly correlated with the coder ratings of the mother actor’s positivity, and the same held for the coder ratings of negativity; this is not surprising, because in each video segment, the focal actor portrayed much more emotion and behavior than the partner. Each of the coder ratings was correlated with children’s evaluations of the actors’ behavior in the expected direction; children’s evaluations were scaled so that high scores indicated worse evaluations (evaluations of behavior as more “bad”). Thus, coder ratings of each actor’s positivity were negatively associated with children’s evaluations of each actor’s behavior as bad, and negativity codes were positively associated with evaluations of behavior as bad. Notably, the correlations between the coder ratings and children’s evaluations were computed ignoring the nested nature of the data, to provide a general sense of the associations between these variables. CPIC scores were generally positively correlated with one another, but were not significantly correlated with children’s evaluations of the actors’ behavior (aside from a non-significant trend for the correlation between Self-blame and evaluations of the father actor). Evaluations of the mother and father actors were positively correlated with one another.

We tested our hypotheses regarding children’s appraisals of their parents’ conflict as moderators of associations of coder ratings with children’s evaluations beginning with the CPIC Conflict Properties scale. For the model predicting children’s evaluations of the father actor, the Conflict Properties X father actor negativity interaction was significant. To interpret this interaction, we computed the simple slopes for the association between father negativity and child evaluations of the father actor’s behavior at the mean of Conflict Properties and ±1 standard deviation (SD) around the mean (Aiken and West 1991). The simple slopes for the father negativity-father evaluation association were significant one SD below the mean, t(2292) = 18.73, p < .001, at the mean, t(2292) = 28.72, p < .001, and one SD above the mean, t(2292) = 21.78, p < .001. Thus, greater coder ratings of father actor negativity predicted worse child evaluations of the father actor across all levels of Conflict Properties scores. The simple slopes for the Conflict Properties-father evaluation association were non-significant one SD below the father negativity mean, t(183.97) = −1.63, p = .10, at the mean, t(83) = −0.49, p = 0.63, and one SD above the mean, t(183.97) = 0.84, p = 0.40. Thus, we followed procedures recommended by Preacher, Curran, and Bauer (2006) using the utility for multilevel 2-way interactions to identify the region of significance. This analysis revealed that the association between coder-rated father negativity and father evaluations was significant for values of (centered) Conflict Properties <−838.06 (132.11SDs below the mean) and >−44.19 (6.97 SDs below the mean). All participants’ Conflict Properties scores were >−44.19. Thus, as Conflict Properties scores increased, the association between father actor negativity and evaluations of the father actor’s behavior became stronger. Additionally, negativity of both actors predicted worse child evaluations of the father actor, and positivity of the father actor predicted better child evaluations of the father actor (Table 2). All other first-order and interaction effects in this model were non-significant.

For the model predicting children’s evaluations of the mother actor with the CPIC Conflict Properties as a moderator, the tests of the first-order effect of Conflict Properties and of the interaction effects between Conflict Properties and the coder ratings of positivity and negativity were all non-significant. However, coder-rated negativity of both actors predicted worse child evaluations of the mother actor’s behavior [mother negativity: t(2292) = 25.53, p < .001; father negativity: t(2292) = 2.98, p < .01], coder-rated positivity of both actors predicted better child evaluations of the mother actor [mother positivity: t(2292) = −20.02, p < .001; father positivity: t(2292) = −6.61, p < .001], and higher levels of SES predicted worse evaluations [t(83) = 2.45, p < .05]. Tests of the other covariates were all non-significant. Thus, these results indicated that the mother and the father actors’ coder-rated negativity and positivity predicted children’s evaluations.

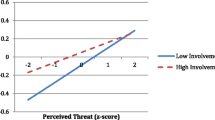

We then tested CPIC Threat scores as moderators of associations of the coder ratings of negativity and positivity with children’s evaluations. For the model predicting children’s evaluations of the father actor (Table 3), the Threat X mother actor positivity interaction was significant (see Fig. 1a). To interpret this interaction, we computed the simple slopes for the association between coder-rated mother positivity and child evaluations of the father actor’s behavior at the means and +/−1SD around the means of Threat and of mother actor positivity (Aiken and West 1991). The simple slope for the mother positivity-father evaluation association was significant at values of Threat one SD below the mean, t(2292) = −2.44, p < .05, non-significant at the mean, t(2292) = −0.48, p = 0.63, and a non-significant trend one SD above the mean, t(2292) = 1.75, p = .08. The simple slope for the Threat-father evaluation association was significant for codes of mother positivity one SD below the mean, t(172.83) = −3.08, p < .01, a non-significant trend at the mean, t(83) = −1.73, p = 0.09, and non-significant one SD above the mean, t(172.83) = 0.20, p = .84. Thus, the mother actor’s positivity was unrelated to child evaluations of the father actor for children who had average or high perceptions of threat regarding their parents’ conflicts. However, for children who had low perceptions of threat, the mother actor’s positivity was negatively related to child evaluations of the father actor’s behavior.

a Association between mother actor positivity and child evaluations of father actor behavior moderated by CPIC Threat. Asterisks denote simple slopes that differ significantly from zero. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. b Association between father actor negativity and child evaluations of father actor behavior moderated by CPIC Threat. Asterisks denote simple slopes that differ significantly from zero. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

In addition, the Threat X coder-rated father actor negativity interaction was significant (Fig. 1b). Computing the simple slopes at the mean of Threat and +/−1SD, the simple slope for the father negativity-father evaluation association was significant at all levels of Threat: one SD below the mean, t(2292) = 18.44, p < .001, at the mean, t(2292) = 28.73, p < .001, and one SD above the mean, t(2292) = 22.09, p < .001. Computing the simple slopes for the Threat-father evaluation association at the mean of father actor negativity and ±1SD, the simple slope was significant and negative one SD below the mean, t(205.57) = −2.94, p < .01, marginal and negative at the mean, t(83) = −1.73, p = .09, and non-significant one SD above the mean, t(205.57) = 0.19, p = .85. Thus, at low levels of coder-rated father actor negativity, threat perceptions were negatively related to evaluations of the father actor’s behavior. However, at high levels of coder ratings of the father actor’s negativity, threat appraisals did not predict children’s evaluations of the father actor’s behavior. In addition, coder-rated negativity of both actors predicted worse child evaluations of the father actor, and coder-rated positivity of the father actor predicted better child evaluations of the father actor, but the other first-order and interaction effects in this model were non-significant.

For the model predicting children’s evaluations of the mother actor with the CPIC Threat scale included as a moderator, results were very similar to those without the Threat scale. The tests of the first-order effect of Threat and the tests of the interaction effects between Threat and the coder ratings of positivity and negativity were all non-significant. However, coder ratings of both actors’ negativity predicted worse child evaluations of the mother actor [mother negativity code: t(2292) = 25.50, p < .001; father negativity code: t(2292) = 2.97, p < .01], coder ratings of both actors’ positivity predicted better child evaluations of the mother actor [mother positivity: t(2292) = −20.00, p < .001; father positivity: t(2292) = −6.61, p < .001], and higher levels of SES predicted worse evaluations [t(83) = 2.47, p < .05]. Tests of the other covariates were all non-significant.

We then tested CPIC Self-blame as a moderator. For the model predicting children’s evaluations of the father actor, the Self-blame X mother actor positivity interaction was significant, t(2292) = −3.15, p < .01 (see Fig. 2a). The simple slope for the mother positivity-father evaluation association was a non-significant trend one SD below the mean of Self-blame, t(2292) = 1.89, p = .06, and non-significant at the mean of Self-blame, t(2292) = −0.49, p = 0.63, but significant one SD above the mean of Self-blame, t(2292) = −2.58, p < .01. The simple slope for the association between Self-blame and father evaluation was significant one SD below the mean of mother positivity, t(171.77) = 3.06, p < .01, non-significant at the mean of mother positivity, t(83) = 1.58, p = 0.12, and one SD above the mean of mother positivity, t(171.77) = −0.44, p = .66. Thus, mother positivity was unrelated to child evaluations of the father actor when children had average or low perceptions of self-blame. However, for children who had high levels of self-blame, mother actor positivity was negatively related to child evaluations of the father actor. In addition, both actors’ coder-rated negativity predicted worse child evaluations of the father actor [mother negativity: t(2292) = 4.77, p < .001; father negativity: t(2292) = 28.86, p < .001], and coder-rated father (but not mother) positivity predicted better child evaluations [t(2292) = −18.48, p < .001].

a Association between mother actor positivity and child evaluations of father actor behavior moderated by CPIC Self-blame. Asterisks denote simple slopes that differ significantly from zero. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001. b Association between father actor negativity and child evaluations of mother actor behavior moderated by CPIC Self-blame. Asterisks denote simple slopes that differ significantly from zero. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

For the model predicting children’s evaluations of the mother actor, the Self-blame X father actor negativity interaction was significant, t(2292) = 2.00, p < .05 (see Fig. 2b). The simple slope for the father negativity-mother evaluation association was non-significant one SD below the mean of Self-blame, t(2292) = 0.69, p = .49, but it was significant at the mean of Self-blame, t(2292) = 2.99, p < .01, and one SD above the mean, t(2292) = 3.52, p < .001. The simple slope for the Self-blame-mother evaluation association was non-significant one SD below the mean of father negativity, t(201.57) = 0.05, p = .96, and at the mean of father negativity, t(83) = 1.57, p = .12, but it was significant one SD above the mean, t(201.57) = 2.45, p < .05. Thus, at average and high levels of self-blame, father actor negativity positively predicted children’s evaluations of the mother actor. In addition, coder ratings of both actors’ negativity predicted worse child evaluations of the mother actor [mother negativity: t(2292) = 25.62, p < .001; father negativity: t(2292) = 2.99, p < .01], coder ratings of both actors’ positivity predicted better child evaluations of the mother actor [mother positivity: t(2292) = −20.10, p < .001; father positivity: t(2292) = −6.64, p < .001], and higher levels of SES predicted worse evaluations, t(83) = 2.55, p < .05.

Discussion

Children’s cognitive appraisals moderated several of the associations between the coder ratings of positivity and negativity and children’s evaluations. One common pattern was for more negative child appraisals to strengthen associations between high levels of an actor’s negativity, or low levels of an actor’s positivity, and worse evaluations. A related finding was that negative child appraisals strengthened associations between low levels of an actor’s negativity and better evaluations. However, contrary to hypotheses, appraisals did not significantly predict children’s evaluations of the mother or father actor.

The results revealed no significant first-order effects of children’s appraisals on their evaluations of the actors. Thus, children’s appraisals did not directly predict worse (or better) evaluations of interparental behavior. Rather, children’s long-term cognitive appraisals of their parents’ conflict appear to influence children’s immediate cognitive evaluations of conflict behavior only by altering the strength of links between parents’ negativity and positivity and children’s evaluations. Alternatively, since we examined children’s evaluations of actors’ behavior, rather than evaluations of their own parents’ behavior, children’s appraisals of their parents’ conflict may merely not predict their evaluations of other adults during interpersonal interactions. That is, our methodology leaves open the possibility that children’s appraisals of their parents’ conflict may in fact directly predict their evaluations of their own parents’ behavior.

Children’s appraisals of their own parents’ conflict did moderate associations between the actors’ positivity and negativity and children’s evaluations of the actors. Thus, children’s long-term cognitions about their parents’ conflict have implications for associations between conflict behavior and children’s immediate evaluations of conflict behavior. One common interaction pattern was for more negative child appraisals to strengthen associations between high levels of an actor’s negativity, or low levels of an actor’s positivity, and worse evaluations of behavior (or evaluations of behavior as less good). Specifically, the father actor’s negativity predicted less good, more neutral evaluations of the mother actor’s behavior for children who had high levels of self-blame for their own parents’ conflict. In addition, for children who have high levels of self-blame for their parents’ conflicts, low levels of coder-rated mother actor positivity predicted worse child evaluations of the father actor’s behavior, whereas this was not the case for other children (children with low or moderate self-blame levels). The results also indicated that high levels of coder-rated mother actor positivity predicted better child evaluations of the father actor’s behavior for children who had high self-blame scores. This pattern indicates that children’s negative appraisals of their parents’ conflict strengthen associations between more negative, less positive interparental behavior and children’s immediate evaluations of interparental behavior as bad.

Another finding was for children’s negative appraisals to strengthen associations between low levels of the father actor’s negativity and children’s immediate evaluations of the father actor’s behavior as good. This pattern was observed for children who perceived high levels of threat from their parents’ conflict. At low levels of coder-rated father actor negativity, children who perceived high levels of threat from their parents’ conflicts evaluated the father actor’s behavior as less bad (more good), whereas children who perceived little threat evaluated the father actor’s behavior as more bad. However, at high levels of coder ratings of the father actor’s negativity, threat appraisals did not influence children’s evaluations of the father actor’s behavior; coder ratings of greater father actor negativity predicted worse evaluations of the father actor regardless of perceived threat. That is, it appears that when the father is not showing negative behavior, children who perceive high levels of threat are likely to evaluate the father’s behavior as good. These children may have become sufficiently accustomed to their own fathers behaving negatively, that when the father is not behaving negatively they interpret his behavior as positive.

In addition, low levels of threat perceptions also contributed to worse evaluations of the actors in the context of low levels of negativity or positivity. Specifically, low threat strengthened the association between low levels of the mother actor’s positivity and evaluations of the father actor’s behavior as more bad (and high mother positivity predicted more neutral, less bad evaluations of behavior). In addition, low threat strengthened the association between low father actor negativity and evaluations of the father actor’s behavior as bad. It is possible that this pattern of results could involve greater responsiveness of children who have perceive little threat. That is, children whose parents’ conflict poses little threat may be more responsive (or sensitive) to behavior that other children would not consider to be bad. Thus, children who perceive their parents’ conflict as low in threat may have a lower threshold for evaluating conflict behavior as “really bad”, compared with other children. The non-significant trend for a first-order effect of threat on evaluations of the father actor (see Table 3) is somewhat consistent with this interpretation. Low levels of threat predicted marginally worse father evaluations, controlling for the coder ratings of negativity and positivity. Notably, however, this idea is inconsistent with research in other areas. For example, children exposed to severe adversity have been found to more readily detect signs of anger than other children (Pollak and Sinha 2002).

The interaction results may have implications for how children evaluate interpersonal interactions between other individuals, given that their evaluations were of adults other than their own parents. That is, the results suggest that children’s experiences with their parents’ relationship may influence how children evaluate other individuals’ interactions with one another. If so, the interparental relationship may have rather far-reaching consequences for children’s processing of others’ interpersonal interactions. This could help account for findings in previous studies of associations between interparental conflict and children’s social functioning (e.g., McCoy et al. 2013).

In addition to the results of the hypothesis tests, coder-rated actor negativity and positivity predicted children’s evaluations of the actors. That is, coder ratings of each actor’s negativity predicted higher levels of child evaluations of that actor’s behavior as bad, and coder ratings of each actor’s positivity predicted higher levels of child evaluations of that actor’s behavior as good, consistent with findings of previous studies in showing that both negative and positive aspects of conflict are important for understanding links with child functioning (McCoy et al. 2009). In addition, coder ratings of both actors’ negativity predicted worse evaluations of the partner, and coder ratings of the father actor’s positivity predicted better evaluations of the mother actor, suggesting that children utilized information about each actor’s behavior to evaluate the behavior of their partner. Thus, children may interpret negativity on the part of either parent as an indication that both parents are behaving badly, and interpret positivity on the part of the father as an indication that both parents are behaving well. Moreover, it is particularly interesting that the coder ratings of the two actors’ were uncorrelated with one another, but children’s evaluations of the two actors had a very large correlation coefficient (r = .86; see Table 1), a point we thank an anonymous reviewer for noting. Thus, even though the non-focal actor in each segment was relatively inactive, children seemed to use the behavior of the focal parent to evaluate the behavior of the partner. This would be analogous to a situation in which one parent is talking and the other is present but responding little if at all—children may form an evaluation of each parent even in this case.

Whereas previous work has found some differences in associations of mothers’ versus fathers’ behavior and children’s responses, in the current study, associations were very similar for mothers and fathers. For the most part, where differences between mothers and fathers did emerge was in interactions with children’s cognitive appraisals. Specifically, there was only one significant interaction effect for evaluations of the mother actor, compared with four significant interaction effects on evaluations of the father actor. This might suggest that connections of coder ratings of parents’ positivity and negativity with children’s evaluations are more dependent on children’s cognitive appraisals of their parents’ conflict for evaluations of fathers than for evaluations of mothers. Moreover, all of the moderation effects involved negativity on the part of the father actor or positivity on the part of the mother actor (i.e., not the father actor’s positivity nor the mother actor’s negativity). Thus, the father actor’s negativity and the mother actor’s positivity both had influences that were dependent upon children’s long-term cognitive appraisals of the interparental relationship. This result is consistent with the idea that children use their long-term cognitive appraisals of their parents’ conflict to help them evaluate fathers’ negativity and mothers’ positivity in the short-term, consistent with dynamic systems notions of interconnected time scales.

Although most of the covariates were not significantly associated with children’s evaluations, there were some significant associations involving household SES. Higher SES was associated with worse evaluations of the mother (but not the father) actor in several models. It may be that higher SES mothers generally handle conflict in a more positive way than the mother actor in the videos, which may have led their children to evaluate the mother actor’s behavior as more bad. However, the data do not support that interpretation, as SES was not significantly correlated with children’s appraisals of conflict (all rs < 0.09, all ps >.44). Therefore, it is unclear why children in higher SES families evaluated the mother actor’s behavior as more bad. Notably, SES was not associated with evaluations of the father actor, suggesting that this evaluation tendency does not carry over to fathers.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include the sample’s homogeneity in terms of race and SES. Future work should include more heterogeneous samples. Further, there were only two actors in the videos, and both were Caucasian. Although presenting the same couple in all stimuli is common (e.g., Goeke-Morey et al. 2003; Grych 1998), it is important to consider the potential impact of this factor. This factor could have affected our results if idiosyncratic aspects of the actors’ portrayals systematically elicited different responses from children. Although such effects are likely to be small, they should be addressed in future work using stimuli depicting multiple couples of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. Moreover, our sample consisted of families in which the child’s biological parents were married to each other, and the videos depicted a male and a female actor posing as a married couple. Thus, our findings might not generalize to other families, such as single-parent, step-parent, and same-gender-parent families. Conducting related studies with greater generalizability is an important direction for future work.

Although it is possible that demographic variables could moderate some of the associations we examined, we did not test for moderation. Interesting child age and gender differences have emerged in some studies of family relationships (e.g., Malone et al. 2004), but given the dearth of previous studies on children’s evaluations of interparental conflict, the prior literature did not provide a basis for forming hypotheses regarding the potential moderating role of such variables for children’s evaluations. Instead, we included statistical controls for child gender, race, and age, and household SES, providing an initial investigation on which to build in future work.

The figures displaying the moderation results show that child evaluations mostly fell between the values of 1.8 and 2.2, corresponding to evaluations of behavior as “in between good and bad”, rather than evaluations of behavior as clearly good or bad. This limited range might be the result of other methodological decisions, such as our inclusion of evaluations of both focal and partner actors in the statistical analyses, and our focus on interparental negativity and positivity as opposed to specific conflict tactics.

The possible behavioral sequelae of children’s evaluations of conflict behavior are important to consider. For example, children’s evaluations may lead them to engage in efforts to intervene in parents’ conflict or to avoid exposure to the conflict, or their evaluations may result in dysregulated and potentially aggressive behavior, each of which may have implications for children’s subsequent psychological well-being and the development of adjustment problems. Thus, many questions remain for future research. This study represents a first step, however, toward understanding factors that inform children’s evaluations of conflict behavior. Identifying how children evaluate interparental conflict brings us a step closer to understanding how children think about conflict, and to understanding children’s responses to conflict. Ultimately, this work can advance knowledge of the processes that give rise to children’s development and adaptation in the context of their parents’ conflict.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (2002). Effects of marital conflict on children: recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43(1), 31–63.

Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (2010). Marital conflict and children: an emotional security perspective. New York: Guilford Press.

Cummings, E. M., Goeke-Morey, M. C., & Papp, L. M. (2003). Children’s responses to everyday marital conflict tactics in the home. Child Development, 74(6), 1918–1929.

El-Sheikh, M., Cummings, E. M., Kouros, C. D., Elmore-Staton, L., & Buckhalt, J. (2008). Marital psychological and physical aggression and children’s mental and physical health: direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 138–148.

Fosco, G. M., & Feinberg, M. (2015). Cascading effects of interparental conflict in adolescence: linking threat appraisals, self-efficacy, and adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 27, 239–252.

Fosco, G. M., & Grych, J. H. (2008). Emotional, cognitive, and family systems mediators of children’s adjustment to interparental conflict. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(6), 843–854.

Goeke-Morey, M. C., Cummings, E. M., Harold, G. T., & Shelton, K. H. (2003). Categories and continua of destructive and constructive marital conflict tactics from the perspective of U.S. and Welsh children. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(3), 327–338.

Goeke-Morey, M. C., Cummings, E. M., & Papp, L. M. (2007). Children and marital conflict resolution: implications for emotional security and adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(4), 744–753.

Goodman, S. H., Barfoot, B., Frye, A. A., & Belli, A. M. (1999). Dimensions of marital conflict and children’s social problem-solving skills. Journal of Family Psychology, 13(1), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.13.1.33.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1992). Marital processes predictive of later dissolution: behavior, physiology, and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(2), 221–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.2.221.

Gottman, J. M., & Levenson, R. W. (1999). What predicts change in marital interaction over time? A study of alternative models. Family Process, 38(2), 143–158.

Granic, I., & Patterson, G. R. (2006). Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: a dynamic systems approach. Psychological Review, 113(1), 101–131.

Grych, J. H. (1998). Children’s appraisals of interparental conflict: Situational and contextual influences. Journal of Family Psychology, 12(3), 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.12.3.437.

Grych, J. H., & Fincham, F. D. (1990). Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: a cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin, 108(2), 267–290.

Grych, J. H., Harold, G. T., & Miles, C. J. (2003). A prospective investigation of appraisals as mediators of the link between interparental conflict and child adjustment. Child Development, 74(4), 1176–1193.

Grych, J. H., Seid, M., & Fincham, F. D. (1992). Assessing marital conflict from the child’s perspective: the children’s Perception of Interparental Conflict Scale. Child Development, 63(3), 558–572.

Lewis, M. D. (2002). Interacting time scales in personality (and cognitive) development: intentions, emotions, and emergent forms. In N. Granott & J. Parziale (Eds.), Microdevelopment: transition processes in development and learning (pp. 183–212). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Malone, P. S., Lansford, J. E., Castellino, D. R., Berlin, L. J., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (2004). Divorce and child behavior problems: applying latent change score models to life event data. Structural Equation Modeling, 11(3), 401–423.

McCoy, K., Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (2009). Constructive and destructive marital conflict, emotional security and children’s prosocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(3), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01945.x.

McCoy, K., George, M. R. W., Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (2013). Constructive and destructive marital conflict, parenting, and children’s school and social adjustment. Social Development, 22(4), 641–662.

Pollak, S. D., & Sinha, P. (2002). Effects of early experience on children’s recognition of facial displays of emotion. Developmental Psychology, 38(5), 784–791.

Preacher, K. J., Curran, P. J., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31(4), 437–448.

Schermerhorn, A. C., & Cummings, E. M. (2008). Transactional family dynamics: A new framework for conceptualizing family influence processes. In RobertV. Kail (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior 36, (pp. 187–250). San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press.

Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. The Annals of Statistics, 6, 461–464. https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176344136.

Thelen, E. (1995). Time-scale dynamics and the development of an embodied cognition. In R. F. Port & T. van Gelder (Eds.), Mind as motion: explorations in the dynamics of cognition (pp. 69–100). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Van Gelder, T., & Port, R. F. (1995). It’s about time: An overview of the dynamical approach to cognition. In R. F. Port & T. van Gelder (Eds.), Mind as motion: explorations in the dynamics of cognition (pp. 1–44). Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Zemp, M., Bodenmann, G., Backes, S., Sutter-Stickel, D., & Bradbury, T. N. (2016). Positivity and negativity in interparental conflict. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 75(4), 167–173. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000182.

Zemp, M., Merrilees, C. E., & Bodenmann, G. (2014). How much positivity is needed to buffer the impact of parental negativity on children? Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies, 63(5), 602–615. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12091.

Acknowledgements

We thank the families whose participation made this study possible, and to the research assistants who assisted with data collection.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Services (grant number R00 HD064795).

Author contributions

A.C.S.: designed and executed the study, completed the data analyses, and wrote the paper. K.H.: completed preliminary data analyses, assisted with data collection, and collaborated on the writing of the paper. H.W.: assisted with data collection and data management and collaborated on the writing of the paper. H.C.W.: assisted with data collection and data management and collaborated on the writing of the paper. T.R.S.: provided advice regarding the data analyses and collaborated on the writing of the paper. Positivity and Negativity in Interparental Conflict: Links with Children’s Evaluations and Appraisals.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schermerhorn, A.C., Hudson, K., Weldon, H. et al. Positivity and Negativity in Interparental Conflict: Links with Children’s Evaluations and Appraisals. J Child Fam Stud 28, 1914–1925 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01416-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01416-6