Abstract

Instruments that assess parenting behavior after divorce have largely focused on the domains of general support of and conflict in co-parenting. This paper introduces and validates a measurement tool that provides a more nuanced perspective of the quality of co-parenting behaviors, the Multidimensional Co-Parenting Scale for Dissolved Relationships (MCS-DR). Participants were divorced or currently divorcing parents recruited through a Qualtrics panel (N = 569) to take a university-sponsored, state-approved curriculum, “Successful Co-Parenting After Divorce” and respond to a series of surveys about their experiences in the divorce process. Exploratory factor analysis was used to identify the underlying factor structure of the initial measurement item pool, which consisted of 48 items. From this, a four factor model emerged, consisting of 23 items; one additional item was removed following tests of measurement equivalence as a function of gender suggesting a final measure which consisted of 22 items across the four subscales. Those subscales include: Overt Conflict, Support, Self-Controlled Covert Conflict, and Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict. Confirmatory factor analysis confirmed the four factor structure of the MCS-DR. The dimensions of Support and Overt Conflict demonstrate concurrent validity with an existing measure used in the literature on post-divorce co-parenting. Educators and clinicians may find this newly developed scale useful in helping parents identify their strengths and challenges in post-divorce functioning for the well-being of their children. Implications for the field are also discussed in relation to legislatively and judicially mandated divorce classes in many states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The notion of post-divorce co-parenting can be traced back to the Bohannon’s (1971) stations of divorce. Under this conceptualization, the co-parental divorce refers to divorcing parents’ continued, joint obligation toward raising their child despite the dissolution of their marital/romantic relationship. The nature and quality of co-parenting relationships can impact children after divorce: co-parenting conflict has been tied to children’s economic, emotional, psychological, and social well-being (Grych 2005; Lamb 2010), as well as the long-term quality of their relationship with their parents decades following the divorce (Ahrons 2007). Divorce education programs that are able to decrease co-parenting conflict and increase co-parenting support have been found to facilitate better post-divorce adjustment for children (Bacon and McKenzie 2004), suggesting that the nature and quality of the co-parenting relationship may be a particularly salient point of intervention for divorcing families. Furthermore, research indicates that the co-parenting relationship can serve as a more proximal indicator of adjustment for both parents and children than other frequently assessed aspects of the interpersonal relationship (Feinberg 2003; Margolin et al. 2001).

By its nature, the experience of divorce forces a series of transitions; family transitions centered around the dissolution of a marital relationship introduce substantial ambiguity as “uncoupling is disorganizing, unsettling, and extremely stressful” (Ahrons 1994, p. 75). During this time, familial roles and responsibilities are reconfigured to accommodate the changing structure of the family unit across households (Emery 2012). Family systems theory (Minuchin 1974) suggests that the reconfiguration of roles and responsibilities in this way disrupts established boundaries within the family system and the functioning of individuals within the system. A healthy co-parenting relationship is a critical component to the maintenance of the family system and ultimately the functioning of individuals within the system; conflictual co-parenting relationships that lack cooperation introduce added stress and volatility to the family system (Cox and Paley 1997). The phenomenon of co-parenting is applicable across family contexts, yet research is often divided in assessment and conceptualization. However, regardless of the context, the extant literature suggests co-parenting quality as a complex, multidimensional construct (Feinberg 2003). The review that follows details six primary dimensions of co-parenting that are often theoretically and/or empirically considered: (1) support; (2) cohesion; (3) overt conflict; (4) undermining; (5) disparagement; and (6) triangulation.

Support, or mutual support as it is sometimes referred to as, reflects a parent’s aid, assistance, or otherwise cooperative exchanges as they relate to childrearing (Masheter 1997). Support is frequently considered in the assessment of co-parenting behaviors both within the divorce literature (e.g., Goldsmith 1981) as well as in the broader intact co-parenting literature (e.g., Feinberg et al. 2012). Cohesion conceptually involves the ways in which families demonstrate togetherness, are intertwined, or are engaged in collective behaviors that reflect coordination and consistency in childrearing (Olson 2000). Frequently the conceptualization for co-parenting cohesion is situated within the context of parental alliance (e.g., Morrill et al. 2010) or more broadly considered as positive co-parenting (e.g., McDaniel et al. 2017) within the intact literature. However, applied to the divorce literature, cohesion can reflect behaviors that demonstrate consistency and agreement across households whereas rigidity in the co-parenting relationship often is suggestive of larger dysfunction (Ahrons and Rodgers 1987; Whiteside 1989).

Overt co-parenting conflict, although often noted as simply conflict, considers direct, openly aggressive, or negative exchanges between parents (Buehler et al. 1998). These behaviors are frequently assessed in both the divorce (e.g., Ahrons 1981) and intact (e.g., McHale 1997) literature. Distinguishing from overt behaviors are covert forms of co-parenting conflict, which are conflictual parenting behaviors that present through more indirect methods, including undermining, disparagement, and triangulation. These covert or furtive behaviors among co-parents typically involve “putting the child in the middle of their parenting disagreements or jockeying for the child’s favor” (Murphy et al. 2016, p. 1685). Undermining is a type of covert behavior that often manifests in the form of nonsupport or behaviors that interfere with cooperative childrearing. Although lack of support is sometimes subsumed within other more frequently tapped dimensions of co-parenting (e.g., conflict; Margolin et al. 2001), evidence from the intact and post-divorce literatures suggests undermining is a distinct co-parenting construct with unique predictive ability (e.g., Feinberg et al. 2012; Merrifield and Gamble 2012).

Disparagement manifests in the forms of name calling, making negative remarks, or otherwise creating a negative affect for the child as it relates to their other parent. Similar to undermining, engaging in disparagement reflects a parenting relationship that lacks healthy cooperation (e.g., cohesion; Favez et al. 2015). This form of covert co-parenting conflict is primarily assessed within the intact literature (e.g., McHale 1997) but also demonstrates relevance for divorced families; disparagement is considered an important behavior for programs to target to facilitate better post-divorce adjustment for these families (Gallagher et al. 2014). Triangulation is among the most commonly assessed forms of covert co-parenting conflict. It involves behaviors that circumvent direct interaction among parents utilizing the child as a messenger. It can also involve coalition or alliance formation or other behaviors that blur parent–child and parent–parent boundaries. Triangulation is commonly assessed in both the divorce (e.g., Mullett and Stolberg 1999) and intact (e.g., Margolin et al. 2001) literature. However, in the divorce literature, it has been primarily assessed using child-report measures.

As described, the conceptualization of co-parenting quality varies across contexts and from study to study. Within the divorce literature, one of the earliest and most widely used measures is the Quality of Coparental Communication Scale (QCCS; Ahrons 1981). The measure captures two dimensions of co-parenting behaviors: (1) support and (2) conflict. Some evidence suggests that the subscales can be aggregated to form a single indicator of co-parenting quality (Ahrons 1983). This scale has been used extensively, with numerous iterations and adaptions that constrain the assessment of co-parenting behaviors to isolated dimensions of general support and/or general conflict (e.g., Toews and McKenry 2001) or conceptualize support and conflict as polar ends of a continuum (e.g., Baum 2004; Bonach 2005). A general assessment of co-parenting conflict may be problematic as it is likely tapping into other forms of interpersonal conflict that operate independently of the co-parenting relationship. For example, the Conflict subscale of the QCCS has consistently been found to correlate highly with the Verbal Aggression subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale (Madden-Derdich et al. 2002; Vareschi and Bursik 2005). This Verbal Aggression subscale is conceptualized to measure, “verbal and nonverbal acts which symbolically hurt the other, or the use of threats to hurt the other” (Straus 1979, p. 77). This could suggest a measure of conflict which operates independent of the scope and responsibilities of parenting, yet a primary premise of co-parenting is that it requires both a child and a partner for whom the target parent will interact in relation to or with (Van Egeren and Hawkins 2004). An assessment of general conflict would not meet this assumption, suggesting it may not capture the full range of behaviors expected to comprise co-parenting conflict. Although these general conflict processes may be intertwined with more overt co-parenting behaviors, these behaviors would fundamental differ from the range of covert behaviors described herein (i.e., disparagement, triangulation, and undermining).

Another consideration is that co-parental interactions may exist across multiple levels in the family. Many co-parenting measures do not make this distinction and only focus on a single actor or only the family as a whole. However, there have been attempts at assessing aspects of relationships that are specific to subsystems of a family or the family unit as a whole within a single measure. For example, McHale’s (1997) Co-Parenting Scale (CS) assessed both dyadic and triadic processes across three subscales in the interest of exploring behaviors that involve all family members (triadic), as well as behaviors constrained to direct actions between a subset of individuals (dyadic). Assessments, such as the CS, featuring dyadic and triadic processes that ask parents to evaluate their own behavior and the behaviors of their former partners, may be particularly informative in understanding motivations for certain behaviors and ideation towards future co-parenting behaviors. Some research indicates that mothers who have more positive assessments of co-parenting in general and more favorable evaluations of their former partners as co-parents are more likely to engage regularly in co-parenting with their former partners (Ganong et al. 2011). However, this nuance is lacking in the literature on post-divorce co-parenting. In addition, attempts to apply existing measures designed for the assessment of intact families have been problematic when applied to other populations. For example, use of the CS in a sample that included parents with intact marriages, as well as parents who had been separated, divorced, remarried, or widowed, demonstrated inconsistent internal reliability across subscales (α ranging from .34 to .81; Bögels et al. 2014). For these reasons, there is concern about the generalizability of some of these more nuanced measures of co-parenting from the intact literature across more complex family structures.

The measurement of co-parenting behaviors across family contexts may be complicated by a number of issues, including changing relationship dynamics, roles, and responsibilities that accompany relationship dissolution. Despite this limitation, there have been numerous studies finding utility in understanding these more nuanced aspects of the co-parenting relationship. For example, the Co-Parenting Questionnaire (CQ; Margolin et al. 2001), a measure developed for use with intact families, parses co-parenting conflict into two separate dimensions of triangulation and conflict. There have been studies which utilized this measure to assess co-parenting behaviors among divorced samples (e.g., Beckmeyer et al. 2014; Russell et al. 2016). However, the utility of this measure also presents some limitations when applied to a divorced sample. The CQ in particular only assesses a parent’s perceptions of the other co-parent’s behaviors and, in turn, there is no assessment of a parents’ perceptions of their own behaviors, unlike measures such as the CS which purposefully assess both dyadic and triadic processes.

Additionally, the content of these measures often lacks generalizability across diverse contexts. For example, the CQ contains items that assess agreement on specific childrearing tasks such as “food, chores, bedtime, and homework” and reflect consistent and regular communication about “what happens during this child’s day” (Margolin et al. 2001, p. 9). Although these behaviors are relevant to many co-parenting relationships, the content currently assessed does not capture the range of interactions and challenges that may be experienced by parents following the dissolution of a relationship (e.g., agreement and consistency in routines or rules across households; asking your child about your former partner’s personal life). As such, questions remain whether the phenomenon of co-parenting after relationship dissolution can be fully measured by scales which have been designed to capture this concept for a fundamentally different group of parents (i.e., those in continuously coupled relationships). Despite these limitations, measures such as the CQ do provide valuable insight into the study of co-parenting conflict. This parsing of co-parenting conflict is reflective of literature which suggests that post-divorce co-parenting conflict includes both overt, direct forms of conflict, and covert, indirect or otherwise passive forms of conflict; the former has been the primary subject of research on post-divorce co-parenting (see Buehler and Trotter 1990). Assessments of covert co-parenting conflict that have been utilized in the post-divorce literature have primarily been child-report measures (e.g., Buchanan et al. 1991; Mullett and Stolberg 1999). The reliance on child-report measures highlights the dilemma of assessing covert co-parenting conflict within this population: parents may not be aware of their former partner’s covert behaviors in a way that children may be. Some conceptualizations of co-parenting processes suggest that self-reported co-parenting behaviors that an individual is able to control or regulate may be conceptually distinct from the observed or perceived co-parenting behaviors of their former partners (Van Egeren 2001; Van Egeren and Hawkins 2004), which may reflect a differentiation between behaviors that fall within the control of oneself and those that are external to their control.

This conceptualization, that includes a parsing of overt and covert conflict, with consideration to both perceptions of one’s own behaviors and perceptions of others’ behaviors, is supported by emerging research in the study of post-divorce co-parenting and linked with various indicators of adjustment post-divorce. Indications are that overt forms of co-parenting conflict and perceptions of one’s own covert behaviors are linked to the experience of stress (Petren et al. 2017), while satisfaction with the divorce decree has been linked with both perceptions of the former spouse’s covert behaviors, overt conflict and support (Ferraro and Pasley 2014). Consideration of these alternative forms of co-parenting conflict are important as the limited research which has examined multiple forms of co-parenting conflict post-divorce has suggested that covert forms of co-parenting conflict are moderately correlated, yet conceptually distinct to overt forms of co-parenting conflict (Buchanan et al. 1991; Henley and Pasley 2005). These issues in measurement are further compounded by research suggesting that the experience of co-parenting may be gendered. Not only do parents’ perceptions of the rates of co-parenting communication and cooperation vary among men and women (Finzi-Dottan and Cohen 2014), but it is also important to “recognize that men and women will experience the divorce transition differently” (Bonach et al. 2005, p. 21) altogether. These differences have been exhibited in the ways that co-parenting behaviors are perceived, with some research suggesting that men make greater distinction between dyadic and triadic processes than women (McHale 1997) and other research suggesting that women make greater distinction between covert forms of co-parenting conflict (Pasley et al. 2016). Thus, consideration of these potential differences is an important component of measurement.

In the current study, a new measure of co-parenting quality, the Multidimensional Co-Parenting Scale for Dissolved Relationships (MCS-DR), was assessed with a sample of recently divorced parents. Item development was purposeful with attention given to the limitations described in the extant literature on post-divorce co-parenting, to both capture a more complete picture of co-parenting relationships post-divorce and to ensure that each of the hypothesized constructs contained items which captured a range of behaviors inclusive of multiple actors. Items were designed to reflect concepts of support, cohesion, undermining, disparagement, triangulation, and overt conflict. Attention was also given to include behaviors which may be experienced by parents across multiple contexts, include dyadic and triadic processes where applicable, and include both self- and externally-controlled behaviors. Following the development of items, an evaluation of the item pool was conducted, including Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), tests for measurement equivalence across genders, and tests for validity. In addition, this study will extend previous literature which suggests that co-parenting processes may vary as a function of gender (e.g. Bonach et al. 2005; Ferraro and Pasley 2014) by assessing the MCS-DR for measurement equivalence on the basis of gender.

Method

Participants

Study participants (N = 569) were drawn from parents who participated in an online divorce education program (Successful Co-parenting After Divorce; coparenting.fsu.edu) and agreed to participate in a research study attached to the curriculum. Inclusion criteria required that participants (1) were over the age of 18, (2) had been married at least one time, (3) had divorced within the prior 18 months or were in the process of getting a divorce, and (4) had at least one minor child with the former spouse referenced in the previous criterion; if participants had more than one minor child with that partner they were directed to reference their youngest child (target child). Participants were recruited via a Qualtrics panel and included participants from 39 states within the U.S.

Parents electing to begin the training were directed to an online survey with a set of pre-test measures. Post-test measures were administered at the conclusion of the training. Data used in this study were collected from only one member of the co-parenting dyads. To validate the MCS-DR, two sets of participant responses were drawn from the pre-test survey; due to a disproportionate number of men and women the first sample (Group 1) consisted of only mothers, while the second sample (Group 2) consisted of mothers and fathers. The Group 1 sample consisted of 250 mothers and was used to evaluate the initial item pool using EFA. The Group 2 sample consisted of 319 parents (74.0% female) and was used to confirm the emergent factor structure using CFA. Group 1 participants were on average 36.16 (SD = 7.71) years of age, with target children who were on average 6.39 (SD = 4.64) years of age. These parents were predominately White (82.6%), highly educated (70.9% had at least some college), employed (72.5%), and had primary physical custody of the target child (77.9%). Group 2 participants were on average 35.91 (SD = 8.27) years of age, with target children who were on average 6.72 (SD = 4.28) years of age. These parents were predominately White (85.3%), highly educated (68.5% had at least some college), employed (78.1%), and had primary physical custody of the target child (68.0%).

Procedure

Item development for the MCS-DR

Theory and reviews of the literature were used to develop conceptual definitions for the six hypothesized constructs, including support, cohesion, overt conflict, undermining, disparagement, and triangulation. All six dimensions were anticipated to comprise an overall latent trait of the quality of co-parenting behaviors. Item construction first involved a review of existing measures from both the divorce and intact literatures (e.g., Ahrons 1981; Feinberg et al. 2012); items were adapted where appropriate and new items were developed to create an item pool that reflected the six conceptual definitions. Although some items were modified from existing measures, all items were constructed based upon theory and research with EFA utilized to rigorously test the hypothesized constructs. Eight items were derived to represent each construct (48 items total), with items designed to assess both dyadic (between one parent and the child; between parents only) and triadic (involving both parents and the child) processes where applicable (e.g., triangulating behaviors intrinsically do not include triadic processes). The strategy to assess dyadic and triadic processes within a single construct is common (e.g., McHale 1997); however, when considering a divorced sample, as assessed herein, triadic processes may not translate in the same way as with parents from intact two parent households. Consideration was given to the specific content of the behaviors described by each item to ensure that they were relevant to the population being assessed.

Following item construction, 14 subject matter experts, including three experts with experience specifically in the design of co-parenting measures, were identified based upon their experience in scale development and/or co-parenting processes and asked to review the initial item pool. All of the subject matter experts held doctoral degrees in their respective fields, and, at the time of the review, were employed at academic institutions. Suggestions pertaining to item difficulty, response pattern, conceptualization of factors, and content validity were received and implemented prior to the distribution of the scale to the participants. For example, during the initial construction of items, the hypothesized cohesion subscale was originally conceptualized as agreement in co-parenting, a dimension of co-parenting frequently described in the intact family literature as a distinct construct (e.g., Feinberg et al. 2012) or subsumed within another form of co-parenting behavior (e.g., conflict; Margolin et al. 2001). However, through this review process it was suggested that with the target population these items may be reflective of continuity and closeness that is more aptly conceptualized as the construct of cohesion. Other content level alterations included parsing apart items that were originally triadic in nature (e.g., we support each other’s parenting decisions and discipline even if we may not agree) to represent dyadic exchanges (e.g., I respect my former partner’s parenting decisions even if I do not agree with them). Structural alterations included the rephrasing of items to reduce the reading difficulty to an eighth-grade level, consistent with best practices for parent education (Duncan and Goddard 2011). A final set of 48 items was utilized (8 items per scale), with responses on each item ranging from never (1) to always (6). In reference to their target child, participants were asked “how often does each of these statements describe your relationship and/or interactions with your former partner?” Scores of each emergent subscale consist of the mean of all included items with higher scores reflecting higher levels of each co-parenting dimension respectively. Additional information about the subscales is provided in the results section.

Measures

QCCS support

For comparison to a widely used existing measure, co-parenting support was measured with six items from the QCCS (Ahrons 1981). Sample items included “does your former spouse go out of the way to accommodate any changes you need to make” and “when you need help regarding the child, do you seek it from your former spouse?” Responses ranged from never (1) to always (5). Mean scores were taken with higher scores indicating higher levels of co-parenting support (M = 2.98, SD = 1.02; α = .87).

QCCS conflict

For comparison to a widely used existing measure, co-parenting conflict was measured with four items from the QCCS (Ahrons 1981). Sample items included “when you and your former spouse discuss parenting issues how often does an argument result” and “do you and your former spouse have differences of opinion about issues related to child rearing?” Responses ranged from never (1) to always (5). Mean scores were taken with higher scores indicating higher levels of co-parenting conflict (M = 2.93, SD = 1.10; α = .94).

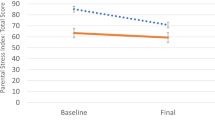

Stress

To assess criterion validity, stress was measured using the seven-item subscale of Perceived Distress from the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen et al. 1983; Hewitt et al. 1992). Sample items included “in the last month, how often have you felt nervous or stressed” and “in the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?” Responses ranged from never (1) to always (5). Higher scores indicated higher levels of stress (M = 2.79, SD = 0.96; α = .89).

Satisfaction with the divorce decree

To assess criterion validity, satisfaction with the divorce decree was measured using five items designed to assess satisfaction with specific aspects of the decree (Sheets and Braver 1996). Sample items included “financial arrangement” and “visitation arrangement.” Responses ranged from not at all satisfied (1) to extremely satisfied (5). Mean scores were taken with higher scores indicating higher levels of satisfaction (M = 3.40, SD = 1.15; α = .87).

Data Analyses

Before evaluating the factor structure of the MCS-DR, dimensionality was assessed to ensure that factor analysis was appropriate. The EFA was then conducted with the initial item pool using the Group 1 sample; analyses were conducted with SPSS 23. Missing data was minimal (0.53% across all items; no more than 2% on any single item). An iterative missing data procedure was preferred given the nature of EFA and thus an estimation maximization procedure was utilized. This procedure allows for estimation of “the peak of the log-likelihood functioning where the maximum likelihood estimates are located” (Enders 2010, p. 104). Next, principal axis factoring using promax rotation with a default kappa value of four was utilized. Principal axis factoring was chosen as the extraction method as it is not constrained by distribution assumptions (Fabrigar et al. 1999). As extracted factors were anticipated to be related, an oblique rotation method was preferred; among oblique rotation methods, promax rotation is suggested (Thompson 2004) and thus was utilized in these analyses. To determine the correct number of factors to extract, eigenvalues, the proportion of the variance explained by each factor, and scree tests were used in combination. Consideration was also given to the overdetermination of factors and the relative factor loadings of items on their respective factors; factor loadings of .50 or higher are recommended when factors contain five or more items (Osborne and Costello 2004).

Next, CFA was conducted using AMOS 21. Full information likelihood estimations were used and four goodness-of-fit statistics were examined: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and χ2/df ratio. CFI and TLI greater than or equal to .90 indicate acceptable model fit (Little 2013). RMSEA values of 0.08 or less and a χ2/df ratio between 3 and 1 indicate reasonable fit (Browne and Cudeck 1993; Carmines and McIver 1981). After confirming the factor structure, a number of post-hoc tests of the emergent factors were conducted. First, tests for measurement equivalence (otherwise referred to as factorial invariance) as a function of gender were conducted. Testing measurement equivalence serves to provide researchers more confidence in the utility of the measure while avoiding, “erroneous conclusions that come from assuming equivalence when there is none” (Dyer 2015, p. 419). Previous literature has suggested that gender differences in the assessment of co-parenting behaviors may exist (e.g., Bonach et al. 2005; Ferraro and Pasley 2014). As such, measurement equivalence was assessed using a series of models, each imposing additional constraints. Models were tested in ascending order, and rated as configural, weak, strong, or strict. When comparing each model to the subsequent model, two indicators of change in model fit were used: (1) change in CFI; and (2) χ2 difference test. A change in CFI of > .01 indicates that the new model fits significantly worse when additional constraints are imposed; a change in CFI of < .01 would suggest that it is appropriate to accept the model with added constraints (Cheung and Rensvold 2002). Nonsignificant χ2 difference tests would also suggest that it is appropriate to accept the subsequent model. RMSEA and the Bentler-Bonett Nonnormed Fit Index (NFI) were also reported, as these can be useful indicators of model fit (Dyer 2015). NFI below .90 indicates inadequate model fit (Bentler and Bonnett 1980). Then, bivariate correlations were used to examine concurrent, discriminant, and criterion validity of the factors with the well-established QCCS (concurrent and discriminant), and measures of perceived distress (criterion) and satisfaction with the divorce decree (criterion).

Results

Initial Factor Structure

Initial testing of sampling adequacy and homoscedasticity suggested that the data were appropriate for factor analysis, given a significant χ2 on Bartlett’s test for sphericity and a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) coefficient of .90. Next, EFA was conducted using the Group 1 sample. The initial 48 items and the associated six factors these items were anticipated to comprise are detailed in Table 1. Items with low factor loadings, high cross-loadings, and/or low communalities were marked as candidates for removal. Problematic items were then removed sequentially until a four-factor model, consisting of 23 items, emerged (see Table 2). Each of the emergent factors had a minimum of 5 items with factor loadings for each item greater than .50, consistent with suggestions by Osborne and Costello (2004). Cross-loadings were minimal with only two of the 23 extracted items having cross-loadings that exceeded .30, and none exceeding .40. The four-factor solution explained 64.70% of the variance in the latent trait of quality of co-parenting behaviors. Item-total correlations indicated that all items were significantly associated with the overall latent trait (magnitude ranging from r = .21, p = .01 to r = .81, p < .001); factor loadings of all items to the first factor ranged in magnitude from .03 to .81.

Factor 1, termed Overt Conflict, consisted of seven items with factor loadings ranging from .55 to .86 (α = .92). These behaviors consisted of openly conflictual or directly confrontational actions originally anticipated to comprise dimensions of disparagement and overt conflict. Items reflect assessments of the reporter’s behavior, their former partner’s behavior, and the interactional conflict between the co-parents. Factor 2, Support, consisted of six items with factor loadings ranging from .72 to .89 (α = .91). These indicators include acts of assistance, consistency, or cooperation and reflect shared meaning regarding parenting and child-rearing expectations. Items were originally anticipated to comprise dimensions of cohesion and support, and they reflect assessments of the co-parenting partnership. Factor 3, Self-Controlled Covert Conflict, consisted of five items with factor loadings ranging from .52 to .70 (α = .77). Factor 4, Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict, consisted of five items with factor loadings ranging from .53 to .70 (α = .83). Factors 3 and 4 included behaviors that were conflictual by nature but either communicated passively or through non-direct methods (including through the target child), and were originally anticipated to comprise dimensions of disparagement, triangulation, and undermining. The defining characteristic which differentiates Factor 3 and Factor 4 is whether participants are engaging in the behaviors themselves (self-controlled) or whether they perceive the behaviors to fall outside of their own control (externally-controlled).

Confirmed Factor Structure

Next, a CFA was conducted using the Group 2 sample (n = 319). The CFA tested the emergent 23-item, four factor structure determined from the EFA, with a second-order factor of global co-parenting quality. Model fit was adequate (CFI = .91; TLI = .89; RMSEA = .08, p < .001; χ2/df ratio = 2.85), with factor loadings between .47 and .87 (see Fig. 1). However, given the TLI fit statistic below .90 and the p-value associated with RMSEA falling below .05, the second-order factor of co-parenting was removed from the CFA model and each of the four factors were examined separately. Each of the subscales independently demonstrated acceptable model fit (Overt Conflict: CFI = .99; TLI = .97; RMSEA = .08, p = .13; χ2/df ratio = 2.96; Support: CFI = .99; TLI = .98; RMSEA = .07, p = .16; χ2/df ratio = 2.70; Self-Controlled Covert Conflict: CFI = .98; TLI = .95; RMSEA = .07, p = .24; χ2/df ratio = 2.47; Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict: CFI = .99; TLI = .98; RMSEA = .07, p = .22; χ2/df ratio = 2.48) with factor loadings between .51 and .84.

Equivalence Across Genders

Each of the four subscales were then assessed for measurement equivalence to determine which, if any, dimensions of co-parenting were equivalent across genders (see Table 3). All subscales demonstrated configural equivalence. Factors loadings were then constrained, with Overt Conflict, Support, and Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict exhibiting weak equivalence due to nonsignificant χ2 difference tests and changes in CFI of less than .01 (.000; .000; .003, respectively). Self-Controlled Covert Conflict had a significant χ2 difference test and a change in CFI of .029. However, tests of partial equivalence suggested that the majority of items exhibited minimal change (Δχ2 = .011 to .085); thus, the weak equivalence model was accepted. Next, intercepts were constrained, with Support and Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict both demonstrating strong equivalence due to nonsignificant χ2 difference tests and changes in CFI of less than .01 (.003; .001, respectively). Overt Conflict had a significant χ2 difference test and a change in CFI of .011 providing support for weak equivalence. Finally, variances were constrained, with both Support and Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict demonstrating strict equivalence due to nonsignificant χ2 difference tests and changes in CFI of less than .01 (.003; .000, respectively). To further examine the emergent constructs given the inequivalence exhibited, independent samples t-tests using 5000 bias-corrected bootstrapped samples and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were tested to compare items as a function of gender. One item from the Overt Conflict subscale demonstrated significant variation across genders (CI .09–.81). As the interpretation of the subscale would not be altered by it, the item was dropped and the subscale was refit using the remaining six items (CFI = .93; TLI = .99; RMSEA = .07, p = .43; χ2/df ratio = 2.54; factor loadings ranging from .66 to .75). The revised 6-item version of the Overt Conflict subscale was then examined for measurement equivalence as a function of gender using the same process described previously, ultimately demonstrating strict equivalence across genders. The final 22-item, 4-factor, version of the MCS-DR is presented in Fig. 2.

The Association between the MCS-DR and Other Divorce Indicators

Following tests of measurement equivalence, a series of bivariate correlations were used to assess the relationship between each of the emergent factors with subscales from the well-established QCCS, as well as indicators of stress and satisfaction with the divorce decree (see Table 4). As expected, the QCCS subscale of Conflict exhibited a large correlation coefficient with the emergent factor of Overt Conflict (r = .79, p < .001). Similarly, the QCCS subscale of Support exhibited a large correlation coefficient with the emergent factor of Support (r = .77, p < .001). The relationship between both QCCS subscales and each of the emergent indicators of covert conflict demonstrated low to moderate correlation coefficients (r = −.11 to .45) suggesting related yet distinct constructs. In addition, the emergent factor of Overt Conflict was significantly related to indicators of both Stress (r = .25, p < .001) and Satisfaction with the Divorce Decree (r = −.51, p < .001). Support was significantly related to Satisfaction with the Divorce Decree (r = .39, p < .001) but not Stress (r = −.10, p = .13). Both Self-Controlled Covert Conflict and Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict were significantly related to Satisfaction with the Divorce Decree (r = −.22, p < .001; r = −.37, p < .001) but only Self-Controlled Covert Conflict was significantly related to Stress (r = .12, p = .05). These findings were consistent with expectations given previous literature and support the concurrent, discriminant, and criterion validity of the MCS-DR.

Discussion

The findings of this study support a four-factor structure for the MCS-DR with constructs of Support, Overt Conflict, Self-Controlled Covert Conflict, and Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict. The dimensions of Support and Overt Conflict demonstrate concurrent validity with existing subscales of the QCCS, which has been used extensively in the literature on post-divorce co-parenting (e.g., Baum 2004; Toews and McKenry 2001), providing support for the construct validity of the subscales. The other emergent subscales, Self-Controlled Covert Conflict and Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict reflect the passive-aggressive, circumlocutory, or otherwise indirect forms of co-parenting conflict distinguished by the actor perpetrating the behavior. Self-Controlled Covert Conflict involves behaviors that fall within the control of the respondent whereas Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict involves the respondents’ perceptions of their former partners’ behaviors and behaviors that manifest through the actions of the target child. The factor structure that emerged was somewhat unexpected considering the hypothesized six subscale factor structure. Self-Controlled Covert Conflict and Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict contained items that were originally anticipated to represent subscales of undermining, disparagement, and triangulation. It may be that in assessment of covert behaviors grouping occurs based upon the actor from whom the behavior is perceived to originate, rather than distinguishing based upon differences in the nature of the behavior. Hypothesized dimensions of cohesion and support factored together (the subscale of Support) which was somewhat unexpected. It may be that consistency, agreement, and similarity in actions across households are viewed as a form of support for parents experiencing a divorce. Although the four-factor solution was not anticipated, each of the emergent dimensions represents an important component to the experience of co-parenting for these parents.

Another important consideration in the structure of the MCS-DR was the fit (or lack thereof) of the second order factor. Support for measures of global co-parenting quality have been found for some measures of post-divorce co-parenting (e.g., QCCS; Ahrons 1981, 1983). However, for the MCS-DR, model fit statistics did not uniformly meet standards of fit; thus, the second order factor model (i.e., a global rating of the quality of co-parenting behaviors) was not supported. There may be utility in its use as a global indicator, but the improved fit at a subscale level would indicate that subscales of the MCS-DR may be better applied as distinct constructs, which when considered in relation to each other reflect the phenomenon of the quality of co-parenting behaviors. This is consistent theoretically as researchers suggest applying a contextual lens to understand the multi-faceted nature of the co-parenting relationship following the dissolution of a romantic relationship (Adamsons and Pasley 2006). In considering the MCS-DR across genders, the Overt Conflict, Support, and Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict subscales demonstrated strict equivalence. The omnibus test of the Self-Controlled Covert Conflict subscale demonstrated configural equivalence; in addition, in examining partial equivalence the majority of items demonstrated weak equivalence and thus this model was deemed acceptable (see Little 2013). With some suggestion of inequivalence, researchers should be cautious of the impact of gender in assessing the covert conflictual behaviors parents engage in; this finding does present an opportunity for future research to explore.

Understanding of the emergent factors from a cognitive perspective is important given the self-report nature of the scale, particularly in discerning the meaning that is attributed to each of the conflict-related subscales. Self-Controlled Covert Conflict includes behaviors that fall within the control of the reporter, including indirect communication methods (e.g., through the child) or more passive-aggressive forms of conflict that can occur in the presence of the other parent (e.g., trying to show up the other parent). Externally-Controlled Covert Conflict distinguishes itself in that these behaviors are perceived by the reporter to originate from sources outside of their own control, both from the former partner specifically (e.g., “my former partner asks our child about my personal life”) or as manifesting through the behaviors of the child (e.g., “when we argue, our child takes sides”). Perception is also a key factor in discerning differences between overt and covert forms of conflict. Specifically, the meaning associated to certain actions that the reporter engages in themselves may be viewed differently from similar behaviors engaged in by the former partner. For example, in considering the set of mirror items “I am sarcastic or make jokes about my former partner’s parenting” and “my former partner is sarcastic or makes jokes about my parenting” the way that parents view their own behaviors may be reflective of more passive-aggressive behaviors, whereas when parents view or hear indirectly about their former partner engaging in these behaviors it may be seen as outwardly conflictual in a substantively different way. This dynamic is evident as the former item loads strongly on the Self-Controlled Covert Conflict subscale whereas the latter loads strongly on the Overt Conflict subscale (both with minimally cross-loadings). Future research should explore how these subscales reflect the perceptions of parents and the implications of these constructs for communication patterns among parents following divorce.

Implications

Compared with existing measures, the MCS-DR offers researchers a tool to explore more nuanced forms of co-parenting conflict among parents that have experienced a divorce. This represents an important advancement in the study of post-divorce co-parenting as covert forms of co-parenting conflict are often understudied, and when studied, are consistently found to be salient predictors of the emotional and psychological well-being of parents and children (Buchanan et al. 1991; Buehler et al. 1998; Henley and Pasley 2005). The scale assesses four integral aspects of the co-parenting relationship, and has been designed to capture a range of behaviors that are relevant and applicable to the complexities of a post-divorce relationship. Although the scale does not specifically include assessments of satisfaction with the co-parenting relationship (e.g., Experiences with Co-Parenting Scale; Beckmeyer et al. 2017) or the content of co-parental communication (e.g., Coparental Interaction Scale; Ahrons 1981), it is suggested that future research could use the MCS-DR in combination with these measures to assess such aspects of the post-divorce relationship.

Practical applications for a measure that is able to capture the nuance of post-divorce co-parenting relationships may be particularly relevant in divorce education programming. There has been an effort for such programs to target specific dimensions of the co-parenting relationship. For example, Bacon and McKenzie (2004) reported varying degrees of divorce education program effectiveness across dimensions of co-parenting including support, cooperation (which functionally operated similarly to our hypothesized construct of cohesion), and both overt and covert forms of co-parenting conflict. As such, a measure that is purposefully designed for parents experiencing the phenomenon of divorce can be invaluable to the assessment and evaluation of divorce education programming. Many states require completion of an approved divorce education course by either all divorcing parents or certain groups of divorcing parents (for a comprehensive review see Pollet and Lombreglia 2008). Despite these mandates which acknowledge that divorcing parents need guidance and support, there are few tools available to determine what targeted help parents need. Instead, many programs utilize a one-size-fits-all approach, focusing on the child’s emotional development and the local legal process. This approach stands in contrast to research on engagement in parent education (Mytton et al. 2014) and the content of many courses may be inappropriate for some parents (e.g., families with domestic violence). Furthermore, these classes typically are not required to accommodate parents’ individual differences, which is one issue the MCS-DR was specifically created to address. Using a nuanced assessment of co-parenting quality, such as the MCS-DR, in conjunction with divorce education has the potential to enhance the experience of divorce education by further identifying sources of familial and relational strength as well as areas for targeted improvement.

There are a variety of potential options for administering the scale in a divorce education setting. It could be incorporated into in-person or online divorce education classes as a self-test that parents would take before receiving standardized content (Anonymous Information Model). Specifically, when included as part of an online course, a parent could complete the instrument online and immediately receive an automated response that offers targeted assistance. Use of the scale could also be tailored to local resources. Some areas may have a full range of divorce education options available locally: short term classes and longer-term interventions that are geared to families that are considered “high conflict.” Local mental health professionals may find the scale useful for making recommendations about matching individual family needs to existing resources. In addition, online divorce education programs could be expanded to provide new modules to which parents are directed, based upon their responses to the MCS-DR. Using an online system with an Anonymous Information Model could help parents gain insight into their own behavior without adding to the documentation often used in litigation in contested divorces. As long as parents take the surveys online anonymously, there will not be a paper trail that could be discoverable in litigation, a notoriously negative, protracted, and damaging process. Although this model does have utility, particularly given concerns with litigation, a more directed approach (Open Information Model) could allow for even greater benefits to parents and educators by providing statutory protection from discovery and protecting parents’ responses. In doing so, parents would have greater freedom to ask trained instructors directly about specific resources and information to help them cope with the challenges of co-parenting. This model is not clinical but educational, and could help parents receive referrals to community agencies to help address problems and heal from a divorce.

There has been some suggestion that the effectiveness of certain interventions post-divorce or during the divorce process may be tied to the quality of co-parenting relationships that exist prior to the dissolution of a relationship (Geasler and Blaisure 1998). As such, evaluation of the MCS-DR in alternative samples, including a currently married sample, could provide valuable next steps in advancing understanding of co-parenting processes and changes in co-parenting processes during periods of systemic change within the family. Further, dyadic assessment of co-parenting relationships, with attention to the congruence of parents’ responses, has been previously recommended (e.g., Ganong et al. 2011) and would be a worthwhile next step.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study does have some limitations that are worth acknowledging and should be considered in the interpretation of results. First, the sample was predominately female; as such our Group 1 analyses utilized an entirely female sample. However, this strategy did allow for Group 2 analyses, where the four-factor structure was confirmed, to utilize a sample of both mothers and fathers. Other limitations related to the sample included minimal diversity in the sample characteristics with respect to education level, race/ethnicity, employment level and resident status. This homogamy limits the generalizability of results and warrants consideration in the design of future studies, which may capture a sample more representative of the divorcing population. In addition, the cross-sectional nature of this study did not allow for the testing of stability in reliability over time; furthermore, it is currently unknown if the MCS-DR acts as a dynamic or enduring assessment of the behaviors. Future research may consider how co-parenting behaviors may transform over time or as a function of divorce education programming.

Also noteworthy is that the sample includes both parents who are currently divorcing and those who have divorced within the prior 18 months. Although this represents an empirically determined and meaningful segment of the population, it is possible that there may be subsamples worth exploring. Additional research could consider tests of measurement equivalence across other demographic indicators that prior literature has suggested can impact the co-parenting relationship (e.g., resident status, legal custody status, target child’s age, initiator status, time since divorce/separation). Researchers consistently note the importance of considering these tests, yet the extant literature on measurement development largely neglects this level of analysis (Parent and Forehand 2017). This study provides a first step in examining demographic indicators by considering parent gender but further exploration is warranted.

Finally, the nature of self-report data and the content of the behaviors inquired about with the MCS-DR introduces the potential for reporter bias. There is the potential for social desirability bias, as many of the items included in the MCS-DR ask participants to consider their own conflictual behaviors. There exists the possibility that when responding to these items parents will make greater generalizations to their relationships and post-divorce interactions that extend beyond the scope of the prompt. Parents may respond in reference to interactions involving all children (not just the youngest child from relationship that has been dissolved), to general conflict independent of childrearing issues and co-parenting altogether, or may respond based upon the intensity of the behavior rather than the frequency of the behavior. Future research may consider further testing of the measure through comparative analyses with slight modifications to the methodology and administration of the measure. In addition, qualitative research could be used to complement administration of the scale to better understand the meaning that parents assign to particular behaviors and how exhaustive these items are in tapping the desired constructs.

References

Adamsons, K., & Pasley, K. (2006). Coparenting following divorce and relationship dissolution. In M. A. Fine & J. H. Harvey (Eds.), The handbook of divorce and relationship dissolution (pp. 241–261). New York, NY: Routledge.

Ahrons, C. R. (1981). The continuing coparental relationship between divorced spouses. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 51, 415–428.

Ahrons, C. R. (1983). Predictors of paternal involvement postdivorce: mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions. Journal of Divorce, 6(3), 55–69.

Ahrons, C. R. (1994). The good divorce: keeping your family together when your marriage comes apart. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

Ahrons, C. R. (2007). Family ties after divorce: long-term implications for children. Family Process, 46, 53–65.

Ahrons, C. R., & Rodgers, R. H. (1987). Divorced families: meeting the challenges of divorce and remarriage. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Co.

Bacon, B. L., & McKenzie, B. (2004). Parent education after separation/divorce: impact of the level of parental conflict on outcomes. Family Court Review, 42, 85–98.

Baum, N. (2004). Typology of post-divorce parental relationships and behaviors. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 41, 53–79.

Beckmeyer, J. J., Coleman, M., & Ganong, L. H. (2014). Postdivorce coparenting typologies and children’s adjustment. Family Relations, 63, 526–537.

Beckmeyer, J. J., Ganong, L. H., Coleman, M., & Markham, M. (2017). Experiences with coparenting scale: a semantic differential measure of postdivorce coparenting satisfaction. Journal of Family Issues, 38, 1471–1490.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606.

Bögels, S. M., Hellemans, J., van Deursen, S., Römer, M., & van der Meulen, R. (2014). Mindful parenting in mental health care: effects on parental and child psychopathology, parental stress, parenting, coparenting, and marital functioning. Mindfulness, 5, 536–551.

Bohannan, P. (1971). Divorce and after: an analysis of the emotional and social problems of divorce.Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

Bonach, K. (2005). Factors contributing to quality coparenting. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 43, 79–103.

Bonach, K., Sales, E., & Koeske, G. (2005). Gender differences in perceptions of coparenting quality among expartners. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 43, 1–28.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Buchanan, C. M., Maccoby, E. E., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Caught between parents: adolescents’ experience in divorced homes. Child Development, 62, 1008–1029.

Buehler, C., Krishnakumar, A., Stone, G., Anthony, C., Pemberton, S., Gerard, J., & Barber, B. K. (1998). Interparental conflict styles and youth problem behaviors: a two-sample replication study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 60, 119–132.

Buehler, C., & Trotter, B. B. (1990). Nonresidential and residential parents’ perceptions of the former spouse relationship and children’s social competence following marital separation: theory and programmed intervention. Family Relations, 39, 395–404.

Carmines, E., & McIver, J. (1981). Analyzing models with unobserved variables: analysis of covariance structures. In G. W. Bohrnstedt & E. F. Borgatta (Eds.), Social measurement: current issues (pp. 65–115). Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as systems. Annual Review of Psychology, 48, 243–267.

Duncan, S. F., Goddard, H. W. (2011). Family life education: principles and practices for effective outreach. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dyer, W. J. (2015). The vital role of measurement equivalence in family research. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 7, 415–431.

Emery, R. E. (2012). Renegotiating family relationships: divorce, child custody, and mediationNew York, NY: Guilford Press.

Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: Guildford Press.

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCaullum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4, 272–299.

Favez, N., Widmer, E. D., Doan, M., & Tissot, H. (2015). Coparenting in stepfamilies: maternal promotion of family cohesiveness with partner and with father. Journal of Child and family Studies, 24, 3268–3278.

Feinberg, M. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: a framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice, 3, 95–131.

Feinberg, M. E., Brown, L. D., & Kan, M. L. (2012). A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting: Science and Practice, 12, 1–21.

Finzi-Dottan, R., & Cohen, O. (2014). Predictors of parental communication and cooperation among divorcing spouses. Journal of Child and family Studies, 23, 39–51.

Gallagher, J. R., Rycraft, J. R., & Jordan, T. (2014). An innovative approach to improving father-child relationships for fathers who are noncompliant with child support payments: a mixed methods evaluation. Journal of Adolescent and Family Health, 6(2), 1–23.

Ganong, L. H., Coleman, M., Markham, M., & Rothrauff, T. (2011). Predicting postdivorce coparental communication. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 52, 1–18.

Geasler, M. J., & Blaisure, K. R. (1998). A review of divorce education program materials. Family Relations, 47, 167–175.

Goldsmith, J. (1981). Relationships between former spouses: descriptive findings. Journal of Divorce, 4(2), 1–20.

Grych, J. H. (2005). Interparental conflict as a risk factor for child maladjustment: implications for the development of preventions programs. Family Court Review, 43, 97–108.

Henley, K., & Pasley, K. (2005). Conditions affecting the association between father identity and father involvement. Fathering, 3, 59–80.

Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Mosher, S. W. (1992). The perceived stress scale: factor structure and relation to depression symptoms in a psychiatric sample. Journal of psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 14, 247–257.

Lamb, M. E. (2010). How do fathers influence children’s development? Let me count the ways. In M. E. Lamb (Ed.), The role of the father in child development. 5th ed (pp. 1–26). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. New York: NY: The Guilford Press.

Madden-Derdich, D. A., Estrada, A. U., Updegraff, K. A., & Leonard, S. A. (2002). The boundary violations scale: an empirical measure of intergenerational boundary violations in families. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 28, 241–254.

Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., & John, R. S. (2001). Coparenting: a link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology, 15, 3–21.

Masheter, C. (1997). Healthy and unhealthy friendship and hostility between ex-spouses. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59, 463–475.

McDaniel, B. T., Teti, D. M., & Feinberg, M. E. (2017). Assessing coparenting relationships in daily life: the daily coparenting scale (D-Cop). Journal of Child and family Studies, 26, 2396–2411.

McHale, J. P. (1997). Overt and covert coparenting processes in the family. Family Process, 36, 183–201.

Merrifield, K. A., & Gamble, W. C. (2012). Associations among marital qualities, supportive and undermining coparenting, and parenting self-efficacy: testing spillover and stress-buffering processes. Journal of Family Issues, 34, 510–533.

Minuchin, S. (1974). Families and family therapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Morrill, M. I., Hines, D. A., Mahmood, S., & Córdova, J. V. (2010). Pathways between marriage and parenting for wives and husbands: the role of coparenting. Family Process, 49, 59–73.

Mullett, E. K., & Stolberg, A. (1999). The development of the co-parenting behaviors questionnaire: an instrument for children of divorce. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 31, 115–137.

Murphy, S. E., Jacobvitz, D. B., & Hazen, N. L. (2016). What’s so bad about competitive coparenting? Family-level predictors of children’s externalizing symptoms. Journal of Child and family Studies, 25, 1684–1690.

Mytton, J., Ingram, J., Manns, S., & Thomas, J. (2014). Facilitators and barriers to engagement in parenting programs: a qualitative systematic review. Health Education & Behavior, 41(2), 127–137.

Olson, D. H. (2000). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22, 144–167.

Osborne, J. W., & Costello, A. B. (2004). Sample size and subject to item ratio in principal components analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 9 (11). http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=9&n=11

Parent, J., & Forehand, R. (2017). The multidimensional assessment of parenting scale (MAPS): development and psychometric properties. Journal of Child and family Studies, 26, 2136–2151.

Pollet, S. L., & Lombreglia, M. (2008). A nationwide survey of mandatory parent education. Family Court Review, 46, 375–394.

Russell, L. T., Beckmeyer, J. J., Coleman, M., & Ganong, L. (2015). Perceived barriers to postdivorce coparenting: differences between men and women and associations with coparenting behaviors. Family Relations, 65, 450–461.

Sheets, V. L., & Braver, S. L. (1996). Gender differences in satisfaction with divorce settlements. Family Relations, 15, 336–342.

Straus, M. A. (1979). Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the conflict tactics (CT) scales. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 41, 75–88.

Thompson, B. (2004). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis: understanding concepts and applications. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Toews, M. L., & McKenry, P. C. (2001). Court-related predictors of parental cooperation and conflict after divorce. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 35, 57–73.

Van Egeren, L. A. (2001). Le rôle du père au sein du partenariat parental (The father’s role in the coparenting relationship). Santé mentale au Québec, 26, 134–159.

Van Egeren, L. A., & Hawkins, D. P. (2004). Coming to terms with coparenting: implications of definition and measurement. Journal of Adult Development, 11, 165–178.

Vareschi, C. G., & Bursik, K. (2005). Attachment style differences in the parental interactions and adaption patterns of divorcing parents. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 42, 15–32.

Whiteside, M. F. (1989). Family rituals as a key to kinship connections in remarried families. Family Relations, 38, 34–39.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Vandermark Foundation (Grant #F08067).

Author Contributions

AJF assisted in the development of the measure, assisted in the collection of data, conducted analyses, and contributed in writing all parts of the manuscript. MLG assisted in the development of the measure, contributed in writing all parts of the manuscript, and edited the manuscript. KOassisted in the collection of data, contributed in writing the literature review and discussion, and edited the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Florida State University Institutional Review Board provided approval for the study.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ferraro, A.J., Lucier-Greer, M. & Oehme, K. Psychometric Evaluation of the Multidimensional Co-Parenting Scale for Dissolved Relationships. J Child Fam Stud 27, 2780–2796 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1124-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1124-2