Abstract

For a long time, associations between temperamental reactivity, emotion regulation (ER) strategies, and depression in youth were studied with a primary focus on the adverse impact of the negative emotionality (NE) temperament dimension and maladaptive ER strategies. The current study aims to answer the question whether positive emotionality (PE) and adaptive ER strategies also play a role in these associations. In a convenience sample of 176 youth (9–18 years; M = 13.58, SD = .94) data were obtained on NE and PE, the use of both maladaptive and adaptive ER strategies, and depressive symptoms. Results indicate that higher levels of NE and lower levels of PE were both associated with more depressive symptoms. Additionally, we found the interaction of NE and PE to be significantly related to depressive symptoms, with lower levels of PE being a vulnerability factor, facilitating the relationship between higher levels of NE and symptoms. Third, higher levels of NE were associated with the use of more maladaptive ER strategies, but were unrelated to adaptive ER strategies. There was no association between PE, and either maladaptive or adaptive ER strategies. Fourth, higher levels of maladaptive ER strategies, and lower levels of adaptive ER strategies were both associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. Finally, no evidence was found for the mediation of ER strategies in the relationship between temperamental reactivity and depressive symptoms. Current study findings underline the need of identifying resilience factors for depression in youth. Insight into such factors is pivotal for the successful development and implementation of prevention and intervention programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Depression is a debilitating psychiatric disorder that affects many young people. The risk of depression increases considerably in early adolescence, and continues to increase into adulthood (Kessler et al. 2001). Early-onset depression can lead to a number of undesirable outcomes including poor academic results, impaired psychosocial functioning (Fergusson and Woodward 2002), further depressive episodes (Burcusa and Iacono 2007), a sixfold increased risk of attempting suicide (Nock et al. 2013), and an increased risk for anxiety disorders, substance-related disorders, and bipolar disorder (e.g., Copeland et al. 2009; Kim-Cohen et al. 2003).

Adolescence can be considered as a notably critical developmental period for the development of mental health disorders, such as depression. In particular, adolescence is accompanied by many transformations at the physical, psychological, as well as at the social level (e.g., Collins et al. 2009; Steinberg, 2005). For example, youth become more autonomous in exploring the environment, while making a transition from relying on their parents for assistance with regulating their emotions to assuming greater responsibility for their own emotions (Baltes and Silverberg 1994). Consequently, their reactive temperament comes more into direct interplay with new life stressors, leading to new experiences of emotional arousal (Larson and Lampman-Petraitis 1989). Hence, the significant increase in affective reactivity (Nelson et al. 2005), in combination with the many new challenges and stressors that accompany this period, pose a threat to the emotional stability of youth.

Overall, the undesirable outcomes accompanied by early-onset depression, in combination with the fact that adolescence is a critical developmental period, underline the necessity of investigating early depressive symptoms in youth in order to reduce the impact of such symptoms and prevent youth from developing a first depressive episode. From a diathesis-stress perspective, child factors such as temperamental reactivity and emotion regulation strategies have been identified as precursors for the development of depressive symptoms in youth (e.g., Yap et al. 2007). However, further research on these child factors is needed as some questions remain to be explored. Specifically, little is known about the way in which these factors interact, as well as about their underlying mechanisms.

Temperament can be defined as biologically-based individual differences in youth’s response to—and interaction with the environment (Rothbart and Posner 2006). The temperament factor has been of specific interest for clinical developmental research, since affective models of depression have suggested that individual differences in temperamental reactivity, a key component of temperament, may predispose individuals to develop depression (Hyde et al. 2008). Typically, developmental models of temperament distinguish between two main dimensions of temperamental reactivity, labeled as negative emotionality (NE) and positive emotionality (PE) (Rothbart and Bates 2006). Both dimensions are clearly affective in nature, and influence tonic levels of emotion as well as emotional reactivity (Zentner and Bates 2008). NE refers to distress and the susceptibility to be affected by negative emotions. It involves features such as sadness, anger, anxiety, irritability, and negative mood (Rothbart et al. 2000). Furthermore, it is assumed to encompass the constructs of negative affectivity (NA) (Clark and Watson 1991), the behavioral inhibition system (BIS) (Corr 2002; Gray 1970), and neuroticism (N) (Eysenck 1967). In contrast, PE involves features such as reward seeking behavior, sociability, and positive mood (Rothbart et al. 2000). It is argued to comprise the constructs of positive affectivity (PA) (Clark and Watson 1991), the behavioral activation system (BAS) (Corr 2002; Gray 1970), and extraversion (E) (Eysenck 1967). When comparing these temperamental reactivity dimensions with the dimensions as proposed by personality research (i.e., N and E), substantial similarities in terminology arise. Because of this considerable overlap, many authors now argue that the traditional dimensions of temperament are closely related to the Big Five characteristics (i.e., N and E; Rothbart and Bates 2006; Muris et al. 2007) and that, starting from preschool age, and increasingly from then onwards, temperament and personality traits appear to be ‘more alike than different’ (Muris et al. 2007). In the current study we will therefore consistently use the terms NE and PE to refer to these broad dimensions.

Temperamental reactivity provides a promising avenue for understanding the development of depression in youth. It has been theoretically assumed that low levels of PE are exclusively related to depression, while high levels of NE are related to both depression and anxiety (i.e., Tripartite Model, Clark and Watson 1991). This has been empirically affirmed in children, adolescents, and adults alike (for review see Klein et al. 2011). Moreover, research has consistently demonstrated that high levels of NE can considered to be a risk factor for the development of internalizing disorders (Clark et al. 1994) and depressive symptoms in youth (Vasey et al. 2013a, b; Wetter and Hankin 2009). Unfortunately, research on affective vulnerabilities to depression has typically focused on NE, and largely neglects the role of PE. Yet, low levels of PE are as significant as high levels of NE when studied in terms of the risk of depression (Lengua et al. 1999). Indeed, it has been shown that low levels of PE predict the development of depressive symptoms in youth (Harding et al. 2014; Hudson et al. 2015), and that of depressive disorder into adulthood (Caspi et al. 1996). Therefore, future research should further include the PE dimension for understanding youth depression.

Through the years, research on temperamental reactivity has typically focused on the associations of NE and PE with depressive symptoms separately (e.g., Harding et al. 2014; Mezulis et al. 2011b). Interestingly, researchers recently started to address the dynamic interplay between NE and PE for depressive symptoms, assuming that both temperamental reactivity dimensions also moderate one another’s association with depressive symptoms (e.g., Loney et al. 2006; Vasey et al. 2013a, b; Verstraeten et al. 2012). This is in line with affective models of depression, in which depression is characterized by both high levels of NE and low levels of PE (i.e., Tripartite Model; Clark and Watson 1991). Current evidence of research investigating the NE × PE interaction indicates that low PE indeed acts as a vulnerability factor (i.e., moderator) in the association between high levels of NE and depressive symptoms. This has been found in non-clinical youth (Loney et al. 2006; Vasey et al. 2013a, b), as well as in youth psychiatric inpatients (Joiner and Lonigan 2000). Additionally, a handful of studies also found prospective evidence for high PE as a resilience factor, buffering the effect of high levels of NE on depressive symptoms (Vasey et al. 2013a, b; Wetter and Hankin 2009). These findings are consistent with theoretical accounts that positive emotions, which are peculiar to PE, can buffer against the negative effects of high levels of NE (Fredrickson 2004).

To date, the majority of studies have examined the direct links between temperamental reactivity and depression in youth. It is however less clear whether there are certain mechanisms through which one’s temperamental disposition may cause an individual to develop depressive symptoms. In a recent review, Yap et al. (2007) posited emotion regulation (ER) as one of the possible mechanisms through which temperamental reactivity may increase youngster’s vulnerability to depression. This theoretical viewpoint is also reflected in the ABC model of Hyde et al. (2008) in which certain maladaptive ER strategies (i.e., rumination) are considered to be one possible mechanism through which high levels of NE influence the development of depressive symptoms in youth.

In contrast to temperamental reactivity, which influences both tonic levels of emotion and emotional reactivity (Zentner and Bates 2008), ER refers to the set of processes by which such emotions are themselves regulated (Gross and Thompson 2007). Over the past years, the emerging theories of child and adult psychopathology have stated that if emotions are not regulated properly, psychiatric symptoms can arise (Greenberg 2002). As a consequence, a number of models have identified various ER strategies in relation to psychopathology (Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema 2012). Some of these strategies have been shown to be negatively associated with psychopathology, while others have been identified with the onset and maintenance of several mental health disorders. Hence, some strategies may be considered to be adaptive (adaptive ER strategies) as they lead to more overall emotional wellbeing, while some others may be maladaptive (maladaptive ER strategies) because they lead to more overall maladjustment in the long term. Specifically, depression has been related to maladaptive ER strategies such as rumination, avoidance, and suppression (Aldao et al. 2010). In contrast, adaptive ER strategies such as reappraisal, problem solving, and acceptance (Aldao et al. 2010) have been negatively associated with depression. However, notwithstanding the widespread evidence for both adaptive and maladaptive ER strategies in adults, we cannot automatically generalize this evidence to children and adolescents (Eisenberg et al. 2010). According to the meta-analytic review of Aldao et al. (2010) on transdiagnostic ER strategies, further research on ER in youth is of specific need, since only 12 of the 144 studies included children and adolescents. Interestingly, both maladaptive—and to a lesser extent, adaptive ER strategies, have already been linked to depressive symptoms in youth (Garnefski et al. 2001; Silk et al. 2003). For example, one maladaptive ER strategy that has recently gained much attention is rumination, which has repeatedly been shown to act as a vulnerability factor for depressive symptoms among adolescents (Mezulis et al. 2006; Rood et al. 2012). However, the relationship between ER strategies and the emergence of depressive symptoms in younger age groups still needs to be investigated more thoroughly. Notably, clinical developmental research has mainly focused on the role of specific maladaptive ER strategies for depression, whereas the role of adaptive ER strategies remains to be explored. Future research should therefore also consider the role of adaptive ER strategies for understanding youth depression.

Although it has been widely accepted that both temperamental reactivity and ER strategies play a key role in the development of depression, research into the specific relationship between these two child factors is still growing. Beginning research has shown that temperamental reactivity affects the development of ER strategies (Rothbart and Sheese 2007). Hence, over time individual differences in ER capacities seem to develop in accordance with youth’s temperament to the extent that youth manage their feelings in a way that is consistent with their temperamental based tolerances (Thompson 2007). For example, high NE has been linked with the shortage of adaptive ER strategies such as reappraisal, and the use of more maladaptive ER strategies such as suppression in young adolescents (Gross and John 2003), as well as to rumination in youth (Mezulis et al. 2011a). On the contrary, high levels of PE have been linked to the use of more adaptive ER strategies, such as positive rumination, in children (Verstraeten et al. 2012), as well as to reappraisal, and the use of less maladaptive ER strategies, such as suppression, in young–adults (Gross and John 2003). On the other hand, low levels of PE have been related to deficits in overall adaptive ER abilities in young–adults (Harding et al. 2014). This underlines the need of addressing also the role of PE in studying the relationship between temperamental reactivity and maladaptive and adaptive ER strategies in adolescents with depressive symptoms.

Additionally, researchers have attempted to understand why temperamental reactivity affects the development of ER strategies. First, it has been theorized that high levels of NE interfere with the cognitive processes necessary for ER (Marshall et al. 2000). Yet, others postulate that the negative reactivity experienced by individuals high in NE pushes individuals’ ER abilities to the limit, making their ER abilities more likely to break down (Gross, 1998). However, these assumptions focus solely on NE and leave the question unanswered as to whether there is a specific role for PE. In this respect, a useful framework to understand why and how both NE and PE can be important for ER is the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson 2004). We hypothesize that this framework could be applicable for several psychological processes, including ER. According to this theory, positive and negative emotions have distinct but complementary cognitive and physiological effects, as well as adaptive functions. More specifically, positive emotions will broaden one’s attentional focus and behavioral repertoire. These broadened mindsets will, in turn, build an individual’s physical, intellectual, and social resources. Within this view, we hypothesize that high levels of PE will provide youth with ER abilities by broadening their mind-sets and resources (Fredrickson, 2004), as well as more approach motivation (Carver et al. 2008). Subsequently, it is plausible to assume that individuals reporting on high levels of PE will use less maladaptive—and more adaptive ER strategies.

Besides focusing on specific ER strategies, others have called for studying the total range of ER strategies an individual has at his or her disposal (e.g., Yap et al. 2007). More specifically, a wider range of strategies offers individuals greater flexibility to shift between different strategies, if necessary. This means that the total range of adaptive ER strategies provides valuable information, with a lower score implying less available strategies. On the contrary, the total range of maladaptive ER strategies is assumed to reflect one’s general dysregulation, since the use of such strategies leads to more maladjustment in the long term. Interestingly, Yap et al. (2011) found that overall, self-reported adaptive and maladaptive ER strategies partially mediated the relation between NE and depressive symptoms in early adolescents. Notably, these results call for further research concerning this domain.

In conclusion, the objective of the current study was to investigate the relationship between temperamental reactivity, ER strategies, and depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth, given the need of further research within a community sample. Firstly, we hypothesized that (a) NE would be positively—and (b) PE negatively related to high depressive symptoms. Furthermore, we expected that (c) both high and low PE would moderate the relationship between low levels of NE and depressive symptoms. Secondly, we hypothesized that, youth characterized by (a) the use of more maladaptive ER strategies would experience high depressive symptoms, and youth characterized by (b) the use of more adaptive ER strategies would experience low depressive symptoms. Subsequently, we sought to investigate the relationship between temperamental reactivity and ER for which it was hypothesized that (a) low levels of NE would be positively correlated with maladaptive ER strategies and negatively correlated with adaptive ER strategies, while (b) high levels of PE would be negatively correlated with maladaptive ER strategies and positively correlated with adaptive ER strategies. Lastly, we expected that (a) the presence of more maladaptive, as well as the lack of adaptive ER strategies, would mediate the assumed positive relationship between NE and depressive symptoms in youth; (b) both the presence of more maladaptive—and the lack of adaptive ER strategies would mediate the assumed negative relationship between PE and depressive symptoms. The results are expected to yield insights into—and offer suggestions for the improvement of existing treatments and provide avenues for new interventions.

Method

Participants

The institutional review board of Ghent University reviewed and approved the protocol of this study. The study was part of two larger PhD-projects on ER and depression. The study sample included 176 youth, with 82 % being girls (n = 145) and ages ranging from 9 till 18 years old (M = 13.58, SD = .94). Data on the education level of the mother and father is primarily characterized by higher education for both mother (89 %) and father (82 %), which is representative for Flanders. More specifically, seven percent of the mothers didn’t finished high school, one out of four mother (25.6 %) had finished high school, 18.5 % went to college for a small period of time, 25.6 % went to college for a long period of time, and 23.2 % graduated from university. Data of 8 mothers was missing. Further, one of the fathers didn’t finished preliminary school, one father finished preliminary school, 14.3 % of the fathers didn’t finished high school, one out of four (26.2 %) fathers had finished high school, 16.7 % went to college for a short period of time, 16.1 % went to college for a long period of time and finally approximately one fourth (25.6 %) graduated from university. Data of eight fathers was missing. Furthermore, 74 % of the families parents were married and living together, in five percent of the families parents were not married but living together, in 19 % of the families parents were divorced, and finally two children reported that one of their parents had died.

Procedure

Trained students of Ghent University were, within the scope of their education, instructed to recruit two participants from their home area (Flanders). Participation was not remunerated. Note that the students were instructed to not recruit participants they knew personally. Since the study was part of two larger PhD-projects on ER and depression, data was collected by two separate, but comparable, research groups of equally trained third-year psychology students. The first group consisted out of 56 students who obtained data on questionnaires such as the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001; Verhulst et al. 1996) and the Hierarchical Personality Inventory for Children (HiPIC) (Mervielde and De Fruyt 1999), both filled in by the mother and the FEEL-KJ (Grob and Smolenski 2005; Braet et al. 2013) filled in by the child. The second group, consisting out of 32 students, obtained data on the same measures. In order to collect a convenience sample, consisting out of different SES groups based on education level of both father and mother, instructions concerning the required age, gender, and type of education of the participants were communicated as non-committal guidelines, leading to more girls that voluntarily participated in the study. After receiving information about the study, informed consent from parents and children was obtained. Participants filled in the questionnaires separately at home in the presence of a student.

Measures

Emotion Regulation (ER)

ER strategies of the participants were measured using the FEEL-KJ (Grob and Smolenski 2005; Dutch version by Braet et al. 2013). Grob and Smolenski (2005) recently developed this valid and reliable questionnaire (Schmitt et al. 2012) that has proven to be useful in capturing the use of several ER strategies in youth (Braet et al. 2014). The FEEL-KJ is a 90 item self-report measure used to assess children and adolescents’ ER strategies in response to anger, fear, and sadness. For each of the three emotions there are 30 items. Participants rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale from (1) ‘almost never’ to (5) ‘almost always’. An individual score can then be calculated for each of the 15 ER strategies included in the questionnaire, with a higher score reflecting a more frequent use, and a lower score reflecting a shortage in the use of the respective strategy. The 15 strategies can be divided into seven adaptive strategies (AS) and five maladaptive strategies (MS). The AS-scale includes problem-oriented action, distraction, put into good humor, acceptance, trying to forget, cognitive problem-solving, and cognitive reappraisal. The MS-scale includes giving up, aggressive action, withdrawal, self-devaluation, and rumination. There are also 3 strategies that cannot be defined as either adaptive or maladaptive. Total scores on the adaptive (FEEL-KJ-AS) and maladaptive (FEEL-KJ-MS) ER scales comprise all three emotions and reflect general dispositions to cope with negative emotions. Cronbach’s alpha for the FEEL-KJ-AS and FEEL-KJ-MS were α = .94 and α = .88 respectively.

Temperament

The temperament dimensions of negative emotionality (NE) and positive emotionality (PE) were measured using the Hierarchical Personality Inventory for Children (HiPIC) (Mervielde and De Fruyt 1999), that was filled in by the mother. We used this broad personality measure to capture temperamental reactivity. More particularly the Neuroticism scale of the HiPIC was used to measure NE, while the Extraversion scale of the HiPIC was used to measure PE. The HiPIC is a questionnaire assessing the Big Five personality traits in children and adolescents (i.e., Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism, and Openness). The HiPIC includes 144 items which are grouped into 18 aspects organized under the main factors. The current study focused on the Extraversion scale as well as the Neuroticism scale. Mothers are requested to indicate on a five-point Likert scale the degree to which the statement describes the child, from (1) ‘barely characteristic’, to (5) ‘highly characteristic’. Higher scores comprise the temperament factor to be more characteristic to the child. The HiPIC has been found to be a reliable and valid measure of trait differences in children (De Fruyt et al. 2006). Cronbach’s alpha for the Neuroticism (NE) scale was α = .94, and α = .85 for the Extraversion (PE) scale.

Depressive Symptoms

The Child Behavior Checklist for Ages 6–18 (CBCL) (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001; Dutch version by Verhulst et al. 1996) was used for measuring depressive symptoms. The CBCL is a 113-item questionnaire used to assess the severity of both emotional and behavioral problems in youth aged 6–18. The CBCL is filled out by the parent and inquires about the child’s behavior in the past 6 months. Items are scored by the parent on a 3-point Likert scale ranging from (0) absent to (2) occurs often. Scores can then be calculated for six different DSM-IV diagnostic categories (the DSM-oriented scales): the higher the score on the respective DSM-oriented scale, the more pathology-specific symptoms the adolescent shows as reported by the mother. The six DSM-Oriented Scales include Affective Problems (Dysthymic and Major Depressive Disorders), Anxiety Problems (Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Separation Anxiety Disorder, and Specific Phobia), Attention/Deficit/Hyperactivity Problems (Hyperactive-Impulsive and Inattentive subtypes), Conduct Problems (Conduct Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Problems), and Somatic Problems (Somatization and Somatoform Disorders) (Achenbach et al. 2003). For this study the Affective Problems DSM-oriented scale (CBCL-AFF) was of specific interest given the focus on depressive symptoms. The DSM-oriented scales of the CBCL (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001) have shown high reliability, convergent -, and discriminative validity (Nakamura et al. 2009). Furthermore, the concurrence between the Affective Problems DSM-oriented scale and the corresponding DSM diagnosis has shown to be significant (Van Lang et al. 2005). Cronbach’s alpha was α = .76 for mother’s ratings on the Affective Problems DSM-oriented scale (CBCL-AFF-M).

Data Analysis

We used SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) version 22.0 to compute internal consistency, obtain descriptive statistics, and conduct preliminary analyses (one-way ANOVA’s, t tests) to assess the effect of both covariates (i.e., age and gender) on the main variables included in this study. On the questionnaire data, 2.34 % of the responses were missing. Missing data were listwise deleted and no total score was calculated on questionnaires that contained >3 missing responses. The CBCL of 171 mothers was available.

In face of testing our first, second, and third hypothesis hierarchical regressions were carried out with statistical significance set at a 0.05. Given the fact that results in developmental research indicate gender and age differences in adolescents’ temperament, ER, and depressive symptomatology (Garnefski and Kraaij 2006; Hyde et al. 2008; Muris et al. 2003) main effects of these variables were controlled for when testing the hypotheses of this study. When testing the effect of the interaction between NE and PE on the outcome variable (depressive symptoms as reported by the mother), adolescent gender and age were entered together in Step 1, NE and PE together in Step 2, and the NE × PE interaction in Step 3. Consequently, based on the results of these regressions, we were able to conclude which expectations of our fourth hypothesis could further be investigated because the regressions provided us with information about the relation between the variables. If one of the regressions showed to be non-significant then we could not assume that there was a relation between the variables and thus further research was not needed. More specifically a relationship was needed given the fact that, when following the recommendations of Baron and Kenny (1986), the proposed mediation model, that could be used to test the relevant expectations of hypothesis four, requires three relationships. The first being (a) the predictor exerting a significant effect on the mediator variable. Secondly (b) the predictor has to exerts a significant effect on the outcome variable, and thirdly (c) the mediator variable has to exerts a significant effect on the outcome variable. When the required relationships would be found, we would investigate the effect of the predictor on the dependent variable, taking into account the mediator. This effect needed to be partially or fully reduced when controlling for the effect of the mediator. The foregoing implies that, when one of the relationships a, b or c were not significant, mediation effects could not be tested. If we found all relationships to be significant, the significance of mediation effects could be tested using the Sobel test (Preacher and Hayes 2004).

Results

All means and standard deviations for the subscales of the HiPIC (Mervielde and De Fruyt 1999) the FEEL-KJ (maladaptive and adaptive ER scales) (Grob and Smolenski 2005; Braet et al. 2013) and the CBCL-AFF-M (Achenbach et al. 2003; Verhulst et al. 1996) as well as the intercorrelations among all variables are presented in Table 1. Given the evidence in literature for gender differences in temperament, ER, and depressive symptoms (Block et al. 1991; Garnefski et al. 2004; Hyde et al. 2008), we investigated whether the gender of the adolescent affected the questionnaire scores. Furthermore, we also controlled for age. Through preliminary regression analysis, we concluded that there was a significant positive effect of age, F(1,171) = 9.94, p < 0.01, on the FEEL-KJ-MS, suggesting that older children reported more maladaptive ER strategies than younger children. Additionally, we found that there was a significant difference in PE between boys (M = 3.75, SD = .35) and girls (M = 3.53, SD = .47) with Levene’s Test for Equality of variance F(1, 172) = 4.20, p < 0.05. In this study boys scored significantly higher than girls on the Extraversion subscale of the HiPIC, filled in by the mother. No other effects of gender and age were found, with all F’s < 1.29.

Temperamental Reactivity and Depressive Symptoms

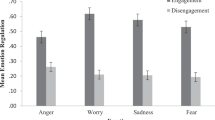

The regression models for the relation between temperament and CBCL-AFF-M are presented in Table 2. Firstly, youth high in NE, β = .52, t(167) = 7.85, p < 0.001, reported more depressive symptoms with NE explaining 27 % of the variance in CBCL-AFF-M. Secondly, youth low in PE, β = −.40, t(167) = −5.48, p < 0.001, reported more depressive symptoms with PE explaining 15 % of the variance in CBCL-AFF-M. Moreover, after adding NE, PE and NE × PE together in one model, the NE × PE interaction explained additional variance over and above the main effects in youth depressive symptomatology, β = −.22, t(167) = −3.26, p < .01. However, the effect of PE on depressive symptoms became non-significant when all three variables were included in one model.

As shown in Fig. 1 the significant interaction was interpreted by plotting the simple regression lines for the high (+1SD) and low (−1SD) values. Equations were then used to plot values of the dependent variable (CBCL-AFF-M) at high and low values of both NE and PE. Consistent with expectation, differences were not observable for low NE but only for high NE: among youth with high NE, only those with low PE had higher levels of depressive symptomatology, as reported by the mother. These results show that it is plausible to assume that, in youth, NE and PE interact, with low levels of PE being a vulnerability factor, placing individuals high in NE more at risk for developing depressive symptoms.

ER Strategies and Depressive Symptoms

As presented in Table 3, analyses revealed that FEEL-KJ-MS did sort a significant positive effect on depressive symptoms, β = .18, t(166) = 2.20, p < 0.05. Additionally, we found that also FEEL-KJ-AS did sort an independent negative effect on depressive symptoms as measured by the CBCL-AFF-M, β = −.17, t(166) = −2.21, p < 0.05. However, when controlling for NE and PE the significant relationship between FEEL-KJ-MS and depressive symptoms disappeared. The found relationships between FEEL-KJ-AS and depressive symptoms became marginally significant after controlling for NE and PE.

Temperamental Reactivity and ER Strategies

In Table 4, the regression models were presented for the relation between both the FEEL-KJ-MS and FEEL-KJ-AS with both NE and PE. Firstly the regression model for the relation between NE and the FEEL-KJ subscales (FEEL-KJ-MS and FEEL-KJ-AS) revealed that youth who are high in NE report on using significantly more maladaptive ER strategies (FEEL-KJ-MS), β = .19, t(168) = 2.68, p < 0.01. On the contrary, we found no evidence for the relation between NE and adaptive ER strategies (FEEL-KJ-AS), β = −.06, t(168) = −.77, ns.

Secondly the regression model for the relation between both FEEL-KJ subscales and PE revealed that there was no significant independent effect of PE on FEEL KJ-MS, β = −.13, t(168) = −1.65, ns, nor a significant independent effect on FEEL-KJ-AS, β = .09, t(168) = 1.19, ns. Moreover, when including NE, PE and NE × PE in one model, the NE × PE interaction didn’t explained any additional variance over and above these main effects in scores on FEEL-KJ-MS, β = −.10, t(168) = −1.37, ns, neither on FEEL-KJ-AS scores β = .04, t(168) = .49, ns.

Temperamental Reactivity, ER Strategies, and Depressive Symptoms

In compliance with abovementioned recommendations of Baron and Kenny (1986), we explored if the required relationships, needed for mediation analyses were found. Firstly, when regarding the negative temperamental reactivity dimension. We were not able to test the hypothesis that maladaptive ER mediates the relationship between NE and depressive symptoms as not all of the conditions were fulfilled. Furthermore, neither the relationships that were needed to test the hypothesis that adaptive ER mediates the relationship between NE and depressive symptoms, were significant. So mediation analyses were not conducted. Secondly, when regarding the positive temperamental reactivity dimension, conditions were not fulfilled to test the hypothesis that maladaptive ER mediates the relationship between PE and depressive symptoms. Furthermore, neither the relationships that were needed to test the hypothesis that adaptive ER mediates the relationship between PE and depressive symptoms, were significant. So mediation analyses were not conducted.

Discussion

The current study investigated the role of temperamental reactivity, and both maladaptive and adaptive ER strategies for depressive symptoms cross-sectionally in a convenience sample of youth. It has extended previous research with the findings that both higher levels of NE and lower levels of PE were associated with more depressive symptoms. Evidence was found for low PE as a moderator in the relationship between high levels of NE and depressive symptoms. Furthermore, higher levels of NE were associated with the use of maladaptive ER strategies, whereas PE was not related to ER. Next, the use of more maladaptive ER strategies, and the shortage of adaptive ER strategies were both associated with more symptoms. No evidence was found for the mediation of ER strategies in the relationship between temperamental reactivity and depressive symptoms. In the section below, we discuss the results in relation to their clinical implications, and outline future research directions and the research limitations.

Linking Temperamental Reactivity to Depressive Symptoms in Youth

A great number of studies have already examined the role of temperamental reactivity for understanding vulnerability for depression. Our first aim was to further contribute to the existing body of knowledge by investigating the specific roles of both NE and PE for depressive symptoms in younger age groups. Our findings indicate that not only high levels of NE but also low levels of PE are strongly related to more depressive symptoms in youth. These findings confirm our first hypothesis, and are consistent with previous research in the light of the view that temperamental reactivity is a significant construct when risk factors for depression are considered (Rothbart and Bates 2006). Although it has been broadly recognized that high levels of NE indeed go hand in hand with depression (see Hyde et al. 2008), we have now found further evidence suggesting that PE is also of great importance when we study depression in youth. More specifically, the finding that PE and depressive symptoms are negatively related is in agreement with a number of longitudinal studies on PE, showing that low PE is a risk factor for the development of depressive symptoms in youth (Verstraeten et al. 2008; Harding et al. 2014; Hudson et al. 2015). Moreover, our data offer evidence supporting the assumption that NE and PE interact as this joint effect is significantly related to depressive symptoms in youth. Indeed, we found an effect of NE × PE along with the separate effects of both NE and PE: low PE seems to be a vulnerability factor in the negative relationship between NE and depressive symptoms. This is consistent with previous findings (e.g., Joiner and Lonigan 2000; Loney et al. 2006; Vasey et al. 2013a, b; Verstraeten et al. 2012; Wetter and Hankin 2009) showing that low levels of PE moderate the relationship between high levels of NE and depressive symptoms in youth.

Overall, these findings underscore the importance of including also PE when considering risk and vulnerability factors for depression (Jylhä and Isometsä 2006). No further evidence was found for the theoretical proposition that high levels of PE may act as a buffer against the undesirable effects of NE, and thus can considered to be an important element of resilience, as suggested by the broaden and built theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson 2004). A possible explanation for this finding could be that high PE sorts its effect on depressive symptoms indirectly by moderating the relationship between high levels of NE and ER strategies, thereby facilitating adaptive ER strategies, while preventing the youngster from using maladaptive ER strategies. However, further research is needed on the specific role of PE as a resilience factor for the development of depression in order to clarify the pathways through which temperamental reactivity may sort its beneficial effects on mental health.

Linking ER Strategies to Depressive Symptoms in Youth

According to some theoretical accounts, individual skills to regulate emotions can differentiate those youth, developing depressive symptoms in response to adverse or stressful life events, from those who are less affected by such events (Hyde et al. 2008; Yap et al. 2007). Despite a great interest in these models, the relationship between general ER abilities and depressive symptoms in youth remains underexplored. Upon investigating the link between ER strategies and depressive symptoms in non-clinical youth, the current study reveals that depressive symptoms are linked to the increased use of maladaptive ER strategies. This finding is in consonance with the existing literature that acknowledges the role of maladaptive ER strategies in adolescent depression (Silk et al. 2003). It might be that, especially the total range of maladaptive ER strategies one has at his or her disposal, reflects a general dysregulation, which could eventually lead to the development of depressive symptoms in the long term. However, future research should further investigate this assumption more thoroughly in order to clarify the role of maladaptive ER abilities for depression in youth.

Interestingly, this study also lends support to Braet et al. (2014) by addressing the role of adaptive ER strategies, which were found to be negatively correlated with depressive symptoms in our study. Furthermore, this study finding is in accordance with the results of Garnefski et al. (2001) who found that the use of more adaptive ER strategies yielded negative relationships with depression in youth. The found relationship with adaptive ER strategies in our study remained notably significant even after we controlled for temperamental reactivity. Hence, our study now provides further evidence showing that the consideration of adaptive ER strategies, as a critical and distinct child factor, is crucial when we consider the risk factors for depression. From a diathesis-stress perspective, it is hypothesized that, while the absence of adaptive ER strategies increases the vulnerability to depression, the presence of adaptive ER strategies, on the other hand, can act as a resilience factor, protecting the youngster from developing early depressive symptoms (Masten 2011). The presence of such adaptive ER strategies could eventually help adolescents in regulating their intense negative emotions properly, thereby avoiding the detrimental effects of such emotions. Therefore, future research should further investigate adaptive ER strategies as potential resilience factors for depression. In conclusion, our study adds to the literature by showing that both maladaptive and adaptive ER strategies are of importance when studying depression in youth.

Interestingly, the found positive relationship between age and maladaptive ER strategies suggests that older children in our study use more maladaptive ER strategies. This is partially in line with the results of Blanchard-Fields and Coats (2008) who found an increase with age in the use of passive, maladaptive ER strategies specifically during adolescence. Furthermore, this finding is in consonance with developmental research which contends that late childhood and adolescence are critical periods for the development of cognitive capacities through which the arsenal of ER strategies expands and becomes more cultivated, in concordance with cognitive development and psychosocial changes (Eisenberg and Morris 2002). Consequently, because of the vast amount of changes that occur during this developmental period, some youth are also more at risk regarding their ER development (Steinberg 2005), which may also explain the increasing rate of psychopathology during this developmental period (Silk et al. 2003).

Temperamental Reactivity and ER Strategies

In the past years, it has been proposed that ER processes are partially shaped by temperamental dispositions (Gross and John 2003). Until now, few studies have considered how early differences in both NE and PE affect ER strategies in youth differently, as the majority of studies focus solely on the direct role of NE for specific ER strategies. With the aim of investigating the role of both NE and PE for overall ER abilities in youth, our study results showed that regarding maladaptive ER strategies, youth who are characterized as being high in NE displayed more maladaptive ER strategies. This is partially consistent with the research of Yap et al. (2011), who found that adolescents, who characterized themselves as being high in NE, reported using maladaptive ER strategies more frequently in response to negative emotions. In conclusion, these findings have extended previous studies (e.g., Mezulis et al. 2011b) on the important role of high levels of NE for maladaptive ER strategies.

However, we did not find evidence for the relationship between NE and adaptive ER strategies. Based on these findings, we assume that especially youth who are high in NE will be more likely to use maladaptive ER strategies as a relief from the overwhelming levels of negative affective arousal, instead of coping with their affect in a more adaptive way. One possible explanation might be that individuals, who are high in NE, start using maladaptive strategies more frequently in adolescence (Nelson et al. 2005). These maladaptive ER strategies may then quickly become a habitual way of managing emotions. Consequently, adaptive ER strategies are used rather rarely, which could result in more noise, and may explain the non-significant relationship between NE and adaptive ER found in our study. Since the results remain inconclusive and given that there is a scarcity of research on adaptive ER strategies, further research concerning adaptive ER strategies is thus recommended in order to gain a profound understanding of how NE is associated differently with both adaptive and maladaptive ER strategies.

In literature, another topic about which there is a dearth of information concerns the link between PE and ER. The current study has addressed this gap by examining more closely the relationship between PE and maladaptive -, as well as adaptive ER strategies. Yet, in conforming with the results of Verstraeten et al. (2012), no significant relationships were found in our study. This is in contrast with the findings of other studies that found that low PE was associated with maladaptive ruminative ER strategies (Verstraeten et al. 2012) and less positive rumination (an adaptive ER strategy) (Harding et al. 2014). There are several explanations for these null findings. First, method variance may play an obstructing role, making it more difficult to find significant results. Second, we used a non-clinical sample which did not allow us to capture those youth who are significantly low in PE, resulting in less clear-cut findings. Third, it is plausible to presume that PE plays a more prominent role in maintaining the flexibility of using various ER strategies in different contexts. In fact, this presumption has been evidenced by the models of ER which emphasize flexibility in the use of various ER strategies as a sign of adaptive regulation (e.g., Bonanno et al. 2004). Nonetheless, due to considerably limited findings in this area of research, future studies should investigate more closely how and when PE does provide youth with more ER possibilities by broadening their mind-sets (Fredrickson 2004). Besides, future work can simultaneously focus on quantifying the ability to switch flexibly between ER strategies, as the contingencies in the environment change. In conclusion, our findings suggest that temperamental reactivity appears to have a stronger relationship with maladaptive ER strategies than with adaptive ER strategies. Overall, we can conclude that NE plays a more prominent role in maladaptive ER strategies than adaptive ER strategies in non-clinical youth. However, our research adopted a correlational approach, hence causation cannot be inferred.

Temperamental Reactivity, ER Strategies, and Depressive Symptoms in Youth

Our last aim was to investigate the role of ER strategies in the relationship between temperamental reactivity and depressive symptoms in youth. In taking into account the recommendations of Baron and Kenny (1986), the precursors of testing this mediation were not met. As a result, we were not able to investigate the effect of temperamental reactivity (i.e., predictor) on depressive symptoms (i.e., outcome), while taking into account ER strategies (i.e., mediator). Hence, no evidence was found for maladaptive, nor for adaptive ER strategies as a mediator in the relationship between temperamental reactivity and such symptoms. This is in contrast with the previous results of Yap et al. (2011) who did find that self-reported ER significantly mediated the relationship between temperament and depressive symptoms. This is also in disagreement with research investigating the mediating role of specific ER strategies such as rumination in this relation (e.g., Hudson et al. 2015; Verstraeten et al. 2008, 2012). Unfortunately, the study of Yap et al. (2011) did not include PE and relied on other measures, which made it difficult to compare with our study. Furthermore, most of the studies investigated the mediating role of rumination in particular (e.g., Hudson et al. 2015; Mezulis et al. 2011a, b; Verstraeten et al. 2011), and did not take into account the adaptive and maladaptive ER strategies in general, making it more difficult to match these findings with ours.

A possible explanation for the findings of our study might be that the method variance played an obstructing role, making it more difficult to find significant results. More specifically, adaptive and maladaptive ER strategies were measured in our study on the basis of child’s self-report, while temperamental reactivity and depressive symptoms were measured by using mother’s report. An alternative possible explanation is that the social desirability or ignorance prevented the mothers from reporting accurately on their children’s depressive symptoms, leading to underreporting (Salbach-Andrae et al. 2009). Nevertheless, we can conclude that the results of our study, in combination with previous findings, underline the need of further longitudinal research with multi-method and multi-informant designs to provide a clear understanding of ER and its role in the relationship between temperamental reactivity and depressive symptoms in adolescents.

Clinical Implications

Adolescence is a critical developmental period, characterized by a higher risk of the onset of depression (Kessler et al. 2001). According to the diathesis-stress model, a better insight into the role of temperamental reactivity, ER, and their relations with depressive symptoms will contribute to a greater understanding of the onset of depression in adolescence (Hyde et al. 2008). Initiatives for both the prevention of a first depressive episode and that of further depressive episodes are highly encouraged, and will be of great value. Furthermore, more profound insights into the specific role of temperamental reactivity and ER for depression should further steer and lead to both psycho-educational and specific interventions targeting emotional reactivity and ER strategies in youth.

Specifically, in drawing on relevant literature, the results from our study can have a number of clinical implications. First, the finding that the relationship between high levels of NE and depressive symptoms was moderated by low levels of PE provides an interesting avenue for future prevention programs. Since it was indicated that the temperamental profile of these youth high in NE and low in PE may place them at greater risk of developing a first depressive episode, prevention programs should aim at identifying this specific youngster group and make them more acutely aware of their vulnerability.

Second, our findings that maladaptive and adaptive ER strategies were related to depressive symptoms, suggest that traditional treatment programs, targeting maladaptive ER strategies such as rumination, should further focus on teaching youth more adaptive ER strategies in order to reduce depressive symptoms and improve treatment outcomes, thus making these youth more resilient. One adaptive ER strategy that has already proven to be well validated is cognitive reappraisal (Gross 1998). This strategy can alter negative emotional responses by changing one’s interpretation of a situation’s meaning (Gross 1998). This approach is consistent with the theories of Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) whose aim is also to teach those suffering from depression adaptive ER skills such as cognitive reappraisal (Beck et al. 1979). Similarly, the Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) also promotes adaptive ER strategies, such as acceptance (Chambers et al. 2009). However, when combining our findings with the surprising results from the meta-analysis of Aldao et al. (2010), who found medium to small effect sizes for both cognitive reappraisal and acceptance, we propose that treatments for depression should further explore the beneficial effects of teaching depressed individuals other adaptive ER strategies such as problem-oriented action, distraction, put into good humor, trying to forget, and cognitive problem-solving (Braet et al. 2013).

Third and most important of all, taking into account the findings that high NE, as well as low PE, were positively related to depressive symptoms and that high NE was positively related to maladaptive, but not adaptive ER strategies, we should ask ourselves, in the face of treatments for depression, how temperamental reactivity can be influenced. Can we make vulnerable individuals (i.e., those who report high levels of NE and low levels of PE) more resilient and protect them from developing depressive episodes in the future? Ideally, treatments programs should address both the downregulation of NE and the upregulation of PE. Our results clearly suggest that traditional treatment programs should also target how to cope with intense negative emotions and low levels of positive emotions and how to prevent the use of maladaptive ER strategies. Researchers have already proposed some techniques to facilitate positive emotions, such as positive events scheduling. However, our findings show that the use of more maladaptive ER strategies and more importantly, the lack of adaptive ER strategies are related to depressive symptoms. These findings, combined with those of previous research that individuals reporting depressive symptoms engage in maladaptive ER strategies that down-regulate positive emotions (Werner-Seidler et al. 2013), suggest that youth will only benefit from positive emotions when they have adaptive ER strategies at their disposal. Consequently, one possible way could be to teach youth to engage in adaptive ER strategies that facilitate positive emotions, such as positive rumination, instead of maladaptive ER strategies that have an adverse effect on positive emotions (Quoidbach et al. 2010).

Limitations and Future Research

Despite the number of notable strengths, the current study has some limitations. As already mentioned, method variance may have hindered the interpretation of the findings. For instance, we only collected data on depressive symptoms as reported by the mother. Because youth tend to report more depressive symptoms than their parents think they have, the present findings could be an underestimate of the associations that were studied (Salbach-Andrae et al. 2009). Therefore, future research should continue to investigate the proposed relationships using multiple informants.

Furthermore, the used sample included more girls than boys. Although we controlled for gender in our study, we propose that further research should study the proposed hypotheses in a sample consisting out of an equal number of boys and girls. Another possible limitation of our study is related to the fact that a possible overlap between the constructs of NE and depressive symptoms may have increased the explained variance we found in our analyses. Because NE has repeatedly been observed to a greater extent in individuals with depressive symptoms, we calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF), which quantifies the severity of multicollinearity in our analysis for NE and depressive symptoms. With VIF = 1.00 it was concluded that multicollinearity was not a problem in our study, and that the constructs did not overlap considerably.

A third limitation of the present study is the exclusive focus on temperamental reactivity. Vulnerabilities for depression involve not only the reactive aspects, but also the regulative aspect of temperament. One regulative factor, which is currently receiving much attention, is Effortful Control (EC). A number of studies have already explored the relationship between EC and depression and found promising results (e.g., Loukas and Roalson 2006). Future research should thus include measures of EC when investigating the relationship between temperament, ER strategies, and depressive symptoms.

Fourth, as we used correlational analyses, we were unable to draw causal inferences, which can be considered as another limitation. Although the present study is helpful in providing information about the nature of the correlations between variables, it does not explain the reasons in which these variables are related. Moreover, there may exist additional variables which account for the found relationships.

Fifth, we relied on self-report questionnaires to assess the individual’s ER abilities, and therefore, response biases may have affected the results. For example, self-report ratings may have been influenced by the participants’ current mood. Also, youth may be less able to report which ER strategies they use because such reporting requires introspection, which may not be fully developed in a part of our sample (Eisenberg et al. 2010). Although the ER measure used in this study demonstrated good psychometric qualities, future research may benefit from using multi-informant measures of ER strategies in youth. Finally, we used a range-wide sample with ages varying from 9 to 18 years old. Given the developmental differences in the cognitive development in this group (Steinberg 2005) and age-effects, further research should replicate our findings in separate age groups so that possible developmental differences can be identified. In our analyses, as we controlled for age, the age variable was ruled out.

Having acknowledged these limitations, we strongly believe the current study has contributed to giving temperamental reactivity and ER strategies the growing research recognition they deserve as important child factors for a better understanding of depressive symptoms in youth. Our study has thus broadened the existing body of literature on the relationship between temperamental reactivity, ER strategies, and youth depressive symptoms. Furthermore, it has extended previous research by highlighting the importance of continued research into the role of the potential resilience factors concerning temperamental reactivity and ER in depression, that is, PE and adaptive ER strategies. Lastly, this study has alerted to the need to understand the interplay between temperamental reactivity and ER strategies in the prediction of depressive symptoms. In general, the study has offered important implications for risk assessment, prevention, and treatment of depression.

References

Achenbach, T. M., Dumenci, L., & Rescorla, L. A. (2003). DSM-oriented and empirically based approaches to constructing scales from the same item pools. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 32, 328–340.

Achenbach, T., & Rescorla, L. (2001). The manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

Aldao, A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). When are adaptive strategies most predictive of psychopathology? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 121, 276–281.

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 217–237.

Baltes, M. M., & Silverberg, S. B. (1994). The dynamics between dependency and autonomy: Illustrations across the life span. In D. L. Featherman, R. M. Lerner, & M. Perlmutter (Eds.), Life-span development and behavior (Vol. 12, pp. 41–90). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford.

Blanchard-Fields, F., & Coats, A. (2008). The experience of anger and sadness in everyday problems impacts age differences in emotion regulation. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1547–1556.

Block, J. H., Gjerde, P. E., & Block, J. H. (1991). Personality antecedents of depressive tendencies in 18-year olds: A prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 726–738.

Bonanno, G. A., Papa, A., O’Neill, K., Westphal, M., & Coifman, K. G. (2004). The importance of being flexible: The ability to both enhance and suppress emotional expression predicts long-term adjustment. Psychological Science, 15, 482–487.

Braet, C., Cracco, E., & Theuwis, L. (2013). Vragenlijst over Emotie Regulatie bij kinderen en jongeren. Amsterdam: Hogrefe.

Braet, C., Theuwis, L., Van Durme, K., Vandewalle, J., Vandevivere, E., Wante, L., et al. (2014). Emotion regulation in children with emotional problems. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 38, 493–504.

Burcusa, S. L., & Iacono, W. G. (2007). Risk for recurrence in depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 959–985.

Carver, C. S., Johnson, S. L., & Joorman, J. (2008). Serotonergic function, two-mode models of self-regulation, and vulnerability to depression: What depression has in common with impulsive aggression. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 921–943.

Caspi, A., Moffitt, T., Newman, D., & Silva, P. (1996). Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 53, 1033–1039.

Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 572–590.

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1991). Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Special Issue: Diagnoses, Dimensions, and DSM-IV: The Science of Classification, 100, 316–336.

Clark, L. A., Watson, D., & Mineka, S. (1994). Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 103–116.

Collins, W. A., Welsh, D. P., & Furman, W. (2009). Adolescents romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 631–652.

Copeland, W. E., Shanahan, L., Costello, J., & Angold, A. (2009). Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 764–772.

Corr, P. J. (2002). J.A. Gray’s reinforcement sensitivity theory and frustrative nonreward: A theoretical note on expectancies in reactions to rewarding stimuli. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 1247–1253.

De Fruyt, F., Bartels, M., Van Leeuwen, K., De Clercq, B., Decuyper, M., & Mervielde, I. (2006). Five types of personality continuity in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 538–552.

Eisenberg, N., & Morris, A. S. (2002). Children’s emotion-related regulation. In R. V. Kail (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 30, pp. 189–229). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., & Eggnum, N. D. (2010). Emotion-related self-regulation and its relation to children’s maladjustment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 495–525.

Eysenck, H. J. (1967). The biological basis of personality. Spingfield: Thomas.

Fergusson, D. M., & Woodward, L. J. (2002). Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 225–231.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 359, 1367–1378.

Garnefski, N., & Kraaij, V. (2006). Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Personality Individual Differences, 40, 1659–1669.

Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., & Spinhoven, P. (2001). Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and depression. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 1311–1327.

Garnefski, N., Teerds, J., Kraaij, V., Legerstee, J., & van den Kommer, T. (2004). Cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: Differences between males and females. Personality and Individual Differences, 36, 267–276.

Gray, J. A. (1970). The psychophysiological basis of introversion-extraversion. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 8, 249–266.

Greenberg, L. (2002). Emotion-focused therapy: Coaching clients to work through their feelings. Washington DC: APA.

Grob, A., & Smolenski, C. (2005). Fragebogen zur Erhebung der Emotionsregulation bei Kindern und Jugendlichen (FEEL-KJ). Bern: Huber.

Gross, J. J. (1998). The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of General Psychology, 2, 271–299.

Gross, J., & John, O. P. (2003). Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 348–362.

Gross, J., & Thompson, R. A. (2007). Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 3–24). New York: Guilford Press.

Harding, K. A., Hudson, M. R., & Mezulis, A. (2014). Cognitive mechanisms linking low trait positive affect to depressive symptoms: Prospective diary study. Cognition and Emotion, 28, 1501–1511.

Hudson, M. E., Harding, K. A., & Mezulis, A. (2015). Dampening and brooding jointly link temperament with depressive symptoms: A prospective study. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 249–254.

Hyde, J. S., Mezulis, A., & Abramson, L. Y. (2008). The ABCs of depression: Integrating affective, biological, and cognitive models to explain the emergence of the gender difference in depression. Psychological Review, 115, 291–313.

Joiner, T. E., & Lonigan, C. J. (2000). Tripartite model of depression and anxiety in youth psychiatric inpatients: Relations with diagnostic status and future symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29, 372–382.

Jylhä, P., & Isometsä, E. (2006). The relationship of neuroticism and extraversion to symptoms of anxiety and depression in the general population. Depression and Anxiety, 23, 281–289.

Kessler, R. C., Avenevoli, S., & Merikangas, K. (2001). Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry, 49, 1002–1014.

Kim-Cohen, J., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Harrington, H., Milne, B. J., & Poulton, R. (2003). Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: Developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 709–717.

Klein, N., Kotov, R., & Buffers, S. J. (2011). Personality and depression: Explanatory and review of the evidence. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 269–295.

Larson, R. W., & Lampman-Petraitis, C. (1989). Daily emotional states as reported by children and adolescents. Child Development, 60, 1250–1260.

Lengua, L. J., Sandler, I. N., West, S. G., Wolchik, S. A., & Curran, P. J. (1999). Emotionality and self-regulation, threat appraisal and coping in children of divorce. Development and Psychopathology, 11, 15–37.

Loney, B. R., Lima, E. N., & Butler, M. A. (2006). Trait affectivity and nonreferred adolescent conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 35, 329–336.

Loukas, A., & Roalson, L. A. (2006). Family environment, effortful control, and adjustment among European American and Latino Early Adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 26, 432–455.

Marshall, P., Fox, N., & Henderson, H. (2000). Temperament as an organizer of development. Infancy, 1, 239–244.

Masten, A. S. (2011). Resilience in children threatened by extreme adversity: Frameworks for research practice, and translational synergy. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 493–506.

Mervielde, I., & De Fruyt, F. (1999). Construction of the Hierarchical Personality Inventory for Children (HiPIC). In I. Mervielde, I. Deary, F. De Fruyt, & F. Ostendorf (Eds.), Personality psychology in Europe. Proceedings of the eight European conference on personality psychology (pp. 107–127). Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

Mezulis, A., Hyde, J. S., & Abramson, L. Y. (2006). The developmental origins of cognitive vulnerability to depression: Temperament, parenting, and negative life events in childhood as contributors to negative cognitive style. Developmental Psychology, 42, 1012–1025.

Mezulis, A. H., Priess, H. A., & Hyde, J. S. (2011a). Rumination mediates the relationship between infant temperament and adolescent depressive symptoms. Depression Research and Treatment, 2011, 487873. doi:10.1155/2011/487873.

Mezulis, A., Simonson, J., McCauley, E., & Vander Stoep, A. (2011b). The association between temperament and depression in adolescence: Brooding and reflection as potential mediators. Cognition and Emotion, 25, 1460–1470.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Blijlevens, P. (2007). Self-reported reactive and regulative temperament in early adolescence: Relations to internalizing and externalizing problem behavior and “Big Three” personality factors. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 1035–1049.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., & Spinder, M. (2003). Relationships between child- and parent-reported behavioral inhibition and symptoms of anxiety and depression in normal adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 34, 759–771.

Nakamura, B. J., Ebesutani, C., Bernstein, A., & Chorpita, B. F. (2009). A psychometric analysis of the CBCL DSM-oriented scales. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31, 178–189.

Nelson, E., Leibenluft, E., McClure, E., & Pine, D. S. (2005). The social re-orientation of adolescence: A neuroscience perspective on the process and its relation to psychopathology. Psychological Medicine, 35, 163–174.

Nock, M. K., et al. (2013). Prevalence, correlates, treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: Results from the NCS-R Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 300–310.

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 717–731.

Quoidbach, J., Berry, E., Hansenne, M., & Mikolajczak, M. (2010). Positive emotion regulation and well-being: Comparing the impact of eight savoring and dampening strategies. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 368–373.

Rood, L., Roelofs, J., Bögels, S. M., & Arntz, A. (2012). The effects of experimentally induced rumination, positive reappraisal, acceptance, and distancing when thinking about a stressful event on affect states in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 73–84.

Rothbart, M. K., Ahadi, S. A., & Evans, D. E. (2000). Temperament and personality: Origins and outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 122–135.

Rothbart, M. K, & Bates, J. E. (2006). Temperament. In R.M. Lerner, N. Eisenberg, & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 99–166). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Rothbart, M. K., & Posner, M. I. (2006). Temperament, attention, and developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 2. Developmental neuroscience (2nd ed., pp. 465–501). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Rothbart, M. K., & Sheese, B. E. (2007). Temperament and emotion regulation. In J. J. Gross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 331–350). New York: The Guilford Press.

Salbach-Andrae, H., Kinkowski, N., Lenz, K., & Lehmkuhl, U. (2009). Agreement between youth-reported and parent-reported psychopathology in a referred sample. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 18, 136–143.

Schmitt, K., Gold, A., & Rauch, U. A. (2012). Deficient adaptive regulation of emotion in children with ADHD. Zeitschrift fur Kinder-und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie, 40, 95–103.

Silk, J. S., Steinberg, L., & Morris, A. S. (2003). Adolescents’ emotion regulation in daily life: Links to depressive symptoms and problem behavior. Child Development, 74, 1869–1880.

Steinberg, L. (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 69–74.

Thompson, R. A. (2007). The development of the person: Social understanding, relationships, conscience, self. In W. Damon, R. Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 24–98). New York: Wiley.

Van Lang, N. D., Ferdinand, R. F., Oldehinkel, A. J., Ormel, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2005). Concurrent validity of the DSM-IV scales affective problems and anxiety problems of the youth self-report. Behavior Research and Therapy, 43, 1485–1494.

Vasey, M. W., Harbaugh, C. N., Lonigan, C. J., Phillips, B. M., Hankin, B. L., Willem, L., & Bijttebier, P. (2013a). Dimensions of temperament and depressive symptoms: Replicating a three-way interaction. Journal of Research in Personality, 47, 908–921.

Vasey, M. W., Harbaugh, C. N., Mikolich, M., Firestone, A., & Bijttebier, P. (2013b). Positive affectivity and attentional control moderate the link between negative affectivity and depressed mood. Personality and Individual Differences, 54, 802–807.

Verhulst, F. C., van der Ende, J., & Koot, H. M. (1996). Handleiding voor de CBCL/4-18. Rotterdam: Sophia Kinderziekenhuis, Erasmus MC.

Verstraeten, K., Bijttebier, P., Vasey, M. W., & Raes, F. (2011). Specificity of worry and rumination in the development of anxiety and depressive symptoms in children. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 50, 364–378.

Verstraeten, K., Vasey, M. W., Raes, F., & Bijttebier, P. (2008). Temperament and risk for depressive symptoms in adolescence: Mediation by rumination and moderation by effortful control. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 349–361.

Verstraeten, K., Vasey, M. W., Raes, F., & Bijttebier, P. (2012). The mediational role of responses to positive affect in the association between temperament and (Hypo)manic symptoms in children. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 36, 768–775.

Werner-Seidler, A., Banks, R., Dunn, B. D., & Moulds, M. L. (2013). An investigation of the relationship between positive affect regulation and depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51, 46–56.

Wetter, E. K., & Hankin, B. L. (2009). Mediational Pathways through which positive and negative emotionality contribute to anhedonic symptoms of depression: A prospective study of adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 507–520.

Yap, M. B. H., Allen, N. B., O’Shea, M., di Parsia, P., Simmons, J. G., & Sheeber, L. (2011). Early adolescents’ temperament, emotion regulation during mother–child interactions, and depressive symptomatology. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 267–282.

Yap, M. B. H., Allen, N. B., & Scheeber, L. (2007). Using an emotion regulation framework to understand the role of temperament and family processes in risk for adolescent depressions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology, 10, 180–196.

Zentner, M., & Bates, J. E. (2008). Child temperament: An integrative review of concepts, research programs, and measures. European Journal of Developmental Science, 2, 7–37.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Van Beveren, ML., McIntosh, K., Vandevivere, E. et al. Associations Between Temperament, Emotion Regulation, and Depression in Youth: The Role of Positive Temperament. J Child Fam Stud 25, 1954–1968 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0368-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0368-y