Abstract

Guilt and shame are emotions commonly associated with motherhood. Self-discrepancy theory proposes that guilt and shame result from perceived discrepancies between one’s actual and ideal selves. Fear of negative evaluation by others may enhance the effects of self-discrepancy especially for shame, which involves fear of others’ reproach. The purpose of this study was to examine the relationships between self discrepancy, guilt, shame, and fear of negative evaluation in a cross-sectional, self report study of mothers. Mothers of children five and under (N = 181) completed an on-line survey measuring guilt, shame, fear of negative evaluation, and maternal self-discrepancies. Guilt and shame were related to maternal self-discrepancy and fear of negative evaluation. In addition, fear of negative evaluation moderated the relationship between maternal self-discrepancy and shame such that mothers who greatly feared negative evaluation had a very strong relationship between these variables. Maternal self-discrepancy and shame were not related among mothers who had low fear of negative evaluation. The results are discussed in terms of the detrimental effects of internalizing idealized standards of perfect motherhood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Maternal Guilt and Shame

Guilt is an emotion that has become accepted as an inherent part of motherhood by society (Sutherland 2010). The universality of maternal guilt is apparent in its report by both working and stay-at-home mothers. Women who work report feeling guilty about not being home with their children (Elvin-Nowak 1999; Guendouzi 2006), while stay-at-home mothers report feeling guilty for not earning additional income that would allow more opportunities for their children (Rubin and Wooten 2007). Some argue that maternal guilt may have an evolutionary basis to ensure that mothers provide the requisite care to promote the survival of their offspring (Rotkirch 2009).

Qualitative research on maternal guilt paints a picture of mothers who feel as though they must fully devote themselves to their children and feel completely responsible for how their children develop (Seagram and Daniluk 2002; Sutherland 2010; Wall 2010). This sense of responsibility combined with very high standards for what it means to be a good mother may lead women to report feeling depleted, inadequate, and guilty (Seagram and Daniluk 2002). Rotkirch (2009) identifies the “motherhood myth” as one of the primary sources of maternal guilt. In other words, women reported feeling guilty because of the inability to live up to either their own or societal expectations for high maternal investment in their children.

It has been suggested that while parents in qualitative interviews generally use the term “guilt” to describe their emotional experience, it may be more accurate to describe their emotional experience as shame (Sutherland 2010). While guilt involves a negative evaluation of a specific behavior, shame represents a more global negative self-evaluation (Tangney 2002; Tangney et al. 2007). On the other hand, it has been noted that one can experience domain specific shame (Gilbert 2007), such as shame specifically about one’s role as a mother. Importantly, shame involves a sense of social evaluation and an expectation or fear that one will be socially judged or sanctioned by others (Deonna and Teroni 2008; Gilbert 1998, 2007). Shame has also been distinguished from guilt as being an emotion that involves failing to live up to one’s goals and ideals as opposed to doing an act that is prohibited (Deonna and Teroni 2008). Shame involves the desire to hide and disappear, while guilt involves self-reproach for a specific bad action (Tangney 2002). Given these distinctions, it is likely that mothers who feel as though they are not living up to their ideals of parenting may be experiencing shame rather than maternal guilt. It is important to determine whether mothers are experiencing shame or guilt because shame has more serious psychological repercussions than does guilt and has been more strongly linked to depression (Kim et al. 2011; Tangney and Dearing 2002).

Self-Discrepancy Theory

Self-Discrepancy Theory (Higgins 1987) purports that the degree of the discrepancy between the actual and ideal self is related to a variety of mental health outcomes including guilt and shame. Specifically, it has been suggested that a discrepancy between how one experiences the self and one’s own internalized ideals is related to guilt, while a discrepancy between one’s sense of self and what one perceives that other people hold as standards is related to shame (Higgins 1987). However, research has suggested that it is difficult to disentangle internalized ideals from one’s sense of what other people hold as standards (Ozgul et al. 2003; Phillips and Silvia 2005; Tangney et al. 1998). Self-discrepancies, in general, have been found to be related to shame, but not guilt in some research (Tangney et al. 1998) and to both shame and guilt in other research (Ozgul et al. 2003; Pavot et al. 1997).

Self-discrepancy theory would suggest that one explanation for maternal guilt and shame is that women experience a discrepancy between their actual sense of self and their ideal sense of who they think they should be as a mother. Society sets very high standards for being a perfect, intensive mother that have been internalized by women (Arendell 2000; Hays 1996; Tummala-Narra 2009). Qualitative research has demonstrated that when women feel as though they have not lived up to the standards they have internalized for being an ideal mother they experience guilt and/or shame (Elvin-Nowak 1999; Guendouzi 2006; Mauthner 1999; Sutherland 2010). Some have suggested that while guilt may be related to specific behaviors that do not meet ideal standards, shame is more related to a sense of being holistically “bad” and being close to an undesired self (Gilbert 2007; Lindsay-Hartz et al. 1995; Tangney 2002). Indeed, perceiving oneself as being close to an undesired self has been shown to be more related to life satisfaction than distance between oneself and an ideal self (Ogilvie 1987). However, for mothers, not being an “ideal” mother may be tantamount to perceiving oneself as an inadequate or “bad” mother as qualitative research has suggested (Guendouzi 2005). Thus, actual/ideal discrepancies may be related to a sense of shame among mothers as “not ideal” may be equated with “bad” in their minds.

There has been a relatively small amount of quantitative research examining the self-discrepancies of mothers. Discrepancies between self and both personal ideals and internalized socially sanctioned ideals of motherhood were related to anxiety, depression, role conflict, and poor coping skills (Polasky and Holahan 1998). In a study of new mothers, discrepancies between their actual sense of self and their ideal self predicted emotions of dejection (including depression) over a 6 month period (Alexander and Higgins 1993). However, the relationship between self-discrepancy and maternal guilt and shame, the primary outcomes identified in self-discrepancy theory (Higgins 1987), has not yet been specifically investigated.

Fear of Negative Evaluation

The fear of being evaluated and judged negatively by others may enhance the potential guilt and shame that results from failing to live up to internalized standards of ideal motherhood. Although guilt and shame can both result when transgressions occur in public, shame has been theorized to be more connected to an internalized fear of being evaluated and judged as unattractive or undesirable by others (Gilbert 1998, 2007; Tangney et al. 2007). Some research has shown that fear of being evaluated by others has been linked to both guilt and shame (Gilbert 2000; Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2006). Other research has suggested that both fear of public exposure and a sense of inferiority are specifically connected to shame (Gilbert 2000; Smith et al. 2002). Thus, fear of negative evaluation may be more centrally connected to a sense of shame than a sense of guilt.

Fear of negative evaluation may enhance the negative effects of failing to live up to one’s standards. Research has suggested that women who were more socially self-conscious reported greater self-discrepancies (Calogero and Watson 2009). Furthermore, women who deemed themselves to be inferior to other women (i.e., critical social comparison) reported lowered self-esteem (Franzoi et al. 2012). Higgins (1987) proposed that people who feel there are discrepancies between their actual attributes and their sense of how others think they ought to be also experience increased fear of negative evaluation and punishment, which may result in an unhealthy cycle of self-discrepancy, fear of evaluation, and shame.

Although much of the research on women’s social comparison and fear of evaluation has been in the domain of body image and attractiveness (e.g., Franzoi et al. 2012; Slevec and Tiggemann 2011), fearing the negative evaluation of others in the domain of mothering has been identified as a source of guilt and shame in the qualitative literature (e.g., Rotkirch 2009; Seagram and Daniluk 2002). Women in qualitative interviews express a fear of being viewed as a “bad mother” and being judged by other mothers as being inadequate (Guendouzi 2005).

Prior research has found that the relationship between self-discrepancies and negative affective outcomes may be moderated by personality variables such as neuroticism (Gonnerman et al. 2000; Wasylkiw et al. 2010) and self-monitoring (Phillips and Silvia 2005). We believe that fear of being evaluated and judged by others may moderate the effects of self-discrepancy on maternal guilt and shame. In other words, feelings of guilt and, especially, shame that may result from discrepancies between actual and ideal maternal sense of self may be exacerbated if women fear negative evaluations from others.

The Current Study

The aims of this study were to examine the relationships between maternal self-discrepancy, fear of negative evaluation, guilt, and shame. There were three major hypotheses. First, we hypothesized that maternal self-discrepancy would be related to guilt and shame. Second, we hypothesized that fear of negative evaluation would be related to both maternal self-discrepancy as well as guilt and shame, but that the relationship between fear of negative evaluation and shame would be stronger than its relationship with guilt. Finally, we hypothesized that the effects of maternal self-discrepancy on shame would be moderated by fear of negative evaluation such that in mothers with low fear of negative evaluation the effects would be minimal, but in mothers with high fear of negative evaluation, the effects of maternal self-discrepancy on shame would be enhanced. Given that fear of reproach of others is more central for shame than for guilt, we did not expect the moderation to occur for guilt.

Method

Participants

The sample included 181 mothers with children who were 5-years-old or younger. The vast majority of mothers were between the ages of 26–41 (88.4 %) years old, with a minority between the ages of 18 and 25 (7.7 %) or 42 and 49 (3.9 %). Participants were primarily married/living with a domestic partner (89.5 %) or in committed relationships (4.4 %), while 6.1 % were either single, separated, or divorced. The vast majority of these relationships were heterosexual (93.9 %) with 6.1 % of participants identifying themselves as either bisexual or lesbian. Approximately 90 % of the participants reported being Caucasian, with 1.1 % reporting their race as Black, 1.1 % as Asian or Pacific Islander, 3.3 % as multiracial, and 4.5 % as some other race. The majority of the mothers reported that they were working full-time (53.9 %), while 15.0 % worked part-time and 31.1 % reported staying-at-home with their children. Participants were predominantly middle to upper-middle class (75.6 %). However, 17.7 % identified themselves as working class and 4.4 % were in poverty, while 2.2 % were wealthy.

Materials

Self-discrepancies

In order to measure self-discrepancies, an adjective checklist was used. Adjective checklists have been found to be valid assessments of self-discrepancies in previous research (e.g., Tangney et al. 1998). As prior research on self-discrepancy has not addressed self-discrepancy about mothering abilities per say, we selected adjectives that have been identified in previous research as qualities associated with being a good mother. Ten adjectives identified in prior qualitative research to describe a “good mother” (Perälä-Littunen 2007) were included (i.e., loving, good listener, in control, gives advice, patient, spends time with child, supportive, role model, just and fair, and responsible). Additionally, five items described in qualitative literature as being associated with being a good mother (Hays 1996) were selected (i.e., available, organized, self-sacrificing, involved in child’s life, and knowledgeable about parenting). Participants were asked to rate how much each of the adjectives described themselves on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much). They were also asked to rate how much each of the adjectives described an ideal mother on a scale of 1 (not at all characteristic) to 5 (very characteristic). An average was calculated across all 15 adjectives for both the participant (i.e., actual) and ideal mother. Discrepancy scores were calculated by subtracting the “actual” average from the “ideal” average. Thus, higher scores indicated a greater level of discrepancy such that they perceived the ideal mother to hold the trait more than they did.

Shame and Guilt

Shame and guilt were measured with 10-items from the guilt and shame subscales of the State Shame and Guilt Scale (SSGS; Marschall et al. 1994). This state measure was chosen because we were interested in the emotions of shame within the context of answering a survey about motherhood rather than a dispositional tendency to respond to events with shame. Participants responded to guilt subscale items (e.g., “I feel remorse, regret”) and shame subscale items (e.g., “I want to sink into the floor and disappear”). These items were rated on a scale ranging from 1 (Not feeling this way at all) to 5 (Feeling this way very strongly). In the original investigations the Cronbach’s alphas were 0.82 for Guilt and 0.89 for Shame. In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas for the SSGS were 0.75 and 0.81, respectively.

Fear of Negative Evaluation

The 12-item Brief Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale (BFNES) was used to measure the degree to which participants experience fear of negative judgment (Leary 1983). Participants answered items (e.g., “I worry about the kind of impression I am making on someone”) on a scale ranging from 1 (Not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (Extremely characteristic of me). In the original investigation the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.90. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the BFNES was 0.94.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through an online social networking site (i.e., Facebook), mothering blogs, mothering discussion boards, a school e-newsletter, and emails sent out to parents whose children attended a local day care. Participants were invited to complete a 15-min survey about the effects of endorsing particular beliefs about parenting. The survey was introduced as one investigating the relationship between beliefs about parenting and well-being. Participants completed the online survey at their own convenience.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

Means and standard deviations, including both actual and possible ranges for all variables, are presented in Table 1. Participants reported a moderate amount of fear of negative evaluation with the average being slightly above the midpoint on the scale. Overall, there were relatively low levels of maternal self-discrepancy, guilt, and shame reported by the participants. Analyses were also conducted to examine the bivariate correlations among the variables. In support of Hypothesis 1, there were small to moderate positive correlations between maternal self-discrepancy, guilt, and shame. In support of Hypothesis 2, there were small correlations between guilt and fear of negative evaluation and moderate correlations between shame and fear of negative evaluation (see Table 2).

Moderation

To test the third hypothesis two regression interaction analyses were conducted to determine whether fear of negative evaluation moderated the relationships between maternal self-discrepancy and the outcomes of guilt and shame. Maternal self-discrepancy, fear of negative evaluation, and their interaction were entered into two regression equations predicting both guilt and shame. The predictor variables were centered prior to calculating interaction terms (Aiken and West 1991).

The first analysis examined the interaction between maternal self-discrepancy and fear of negative evaluation in predicting guilt, R 2 = 0.10, F(3, 177) = 6.41, p < 0.001. Only the main effect of maternal self-discrepancy was a significant predictor of guilt, β = 0.22, p < 0.01. The main effect of fear of negative evaluation (β = 0.13, p = 0.09) and the interaction term (β = 0.09, p = 0.23) were not significant.

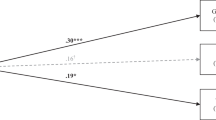

The second regression equation was conducted to predict shame, R 2 = 0.29, F(3, 177) = 23.87, p < 0.001. Both the main effects of maternal self-discrepancy (β = 0.28, p < 0.001) and fear of negative evaluation (β = 0.29, p < 0.001) as well as their interaction (β = 0.23, p < 0.001) were significant. The significant interaction was followed up using simple regression equations of shame scores on the centered maternal self-discrepancy variable at three levels of fear of negative evaluation (see Fig. 1). At two standard deviations above the mean on fear of negative evaluation, maternal self-discrepancy was a significant predictor of shame, β = 0.74, p < 0.001. At two standard deviations below the mean on fear of negative evaluation, maternal self-discrepancy was not a significant predictor of shame, β = −0.20, p = 0.20. Thus, women who had a high fear of negative evaluation had a strong relationship between maternal self-discrepancy and shame; for women who had low fear of negative evaluation, feeling a discrepancy between their actual and ideal self as a mother was not related to shame. These analyses provided support for hypothesis 3.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to extend Higgins (1987) self-discrepancy theory to maternal guilt and shame. The first hypothesis that there would be positive relationships between self-discrepancy and both guilt and shame was supported. Women who reported that they failed to live up to their sense of the ideal mother experienced higher levels of both emotions. This finding is consistent with previous research that has linked self-discrepancy to shame (Tangney et al. 1998). We also found a significant relationship between self-discrepancies and guilt in both the bivariate and regression analyses, which is consistent with some research (Ozgul et al. 2003; Pavot et al. 1997), but is in contrast to Tangney and colleagues’ findings. It may be that discrepancies that are linked specifically to parenting are more related to both shame and guilt than generalized self-discrepancies that are more consistently related to shame.

Our data quantitatively demonstrate that when women believe they do not live up to their internalized standards of what it means to be a good mother, it contributes to their sense of guilt and shame. This sentiment has been expressed in qualitative research (e.g., Seagram and Daniluk 2002); however, this is the first study that has explicitly linked mothering-focused self-discrepancies to feelings of guilt and shame. While women tend to use the word guilt rather than shame in interviews (Sutherland 2010), our data suggest that mothers experience guilt and shame in similar amounts. Although the levels of each reported was relatively low, they both increased not only with the amount of maternal self-discrepancy reported, but also as fear of negative evaluation increased, which is consistent with previous research (Gilbert 2000; Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2006).

Our hypothesis that shame would be more closely linked than guilt to fear of negative evaluation was also supported. This finding is consistent with the theoretical understanding of shame as more closely linked to fear of public disapproval than guilt (Gilbert 2007; Tangney 2002; Tangney et al. 2007) as well as research that has linked shame to a fear of public exposure (Smith et al. 2002). Furthermore, external shame, which is shame that is focused on fear of other’s disapproval is more strongly linked to depression than internal shame (Kim et al. 2011). Thus, shame combined with fear of negative evaluations by others may have particularly negative outcomes for mothers.

Our hypothesis that fear of negative evaluation would moderate the impact of self-discrepancies on shame, but not on guilt, was confirmed. Individuals with high fear of negative evaluation had a very strong relationship between maternal self-discrepancies and shame, while discrepancy and shame were not related among people who had low fear of being judged by others. The fact that this moderation was only significant for the emotion of shame is consistent with the idea that shame is considered a social emotion that involves fearing the social sanction of others (Deonna and Teroni 2008; Tangney 2002; Tangney et al. 2007). Thus, people who fear social evaluation from others may be particularly prone to shame, especially when they feel as though they have not lived up to their internalizations of society’s standards. As hypothesized, guilt, an emotion that has more to do with personal regret over certain specific actions, was less influenced by fear of negative evaluation.

Investigating the experience of guilt and shame in mothers is important because shame, and to a lesser degree guilt, have negative consequences and are particularly linked to depression (Kim et al. 2011). Mothers who internalize the cultural standards of motherhood (Rizzo et al. 2012), as well as experience shame about their inability to meet those standards (Lee 1997), may be particularly prone to depression. Research has suggested that pregnant women who have a realistic orientation and anticipate both positive and negative outcomes of childrearing have lower rates of post-partum depression than women who only anticipate positive outcomes (Churchill and Davis 2010). Thus, women who may have overly idealized visions of what motherhood should be like and what they should be like as mothers may be at risk for guilt about specific behavioral transgressions, shame about being a “bad mother,” and, ultimately, depression. Our data suggest that these risks are particularly enhanced in women who fear the social sanction and judgment of others. Future research should investigate how the emotions of shame and guilt are linked to depression in mothers.

Research has suggested that shame has considerably more negative outcomes than guilt (Tangney 2002; Tangney et al. 2007). Shame-proneness in particular has been linked to higher levels of anger and lower levels of empathy as well as to parenting techniques that emphasize a child’s essential badness rather than a child’s behavior (Tangney 2002). Future research may wish to examine how maternal experiences of shame are related to parenting styles that can induce shame in children (Tangney 2002). Whether the shame experienced by mothers who fail to meet their standards of parenting and see themselves as “bad mothers” is related to labeling misbehaving children as “bad children” is worthy of investigation.

Future research may also wish to expand on the measures of shame and guilt that were used in this study. This study measured a state sense of guilt and shame—in other words how much guilt and shame were felt at the time of completing the questionnaire—a questionnaire about their attitudes and perceptions on parenting. The fact that state shame and guilt were related to actual/ideal parenting discrepancies and fear of negative evaluations is intriguing, but the effect may be stronger with a measure that taps more general feelings of shame and guilt. It may be particularly useful to examine the tendency to feel shame and guilt in the context of particular parenting situations. The most commonly used dispositional measure, the Test of Self Conscious Affect (TOSCA–3; Tangney et al. 2000), examines shame and guilt within specific contexts. However, this measure is based on scenarios that are not specific to mothering. A measurement of the tendency to feel guilt and shame in response to specific scenarios relevant to mothering would be particularly useful in understanding shame and guilt among mothers. Other dispositional measures of shame differentiate shame that stems from an internalized sense of badness (e.g., the internalized shame scale; Cook 1994) and shame that stems from a fear that others are judging one poorly (Goss et al. 1994). Examining how self-discrepanies and fear of negative evaluation differentially relate to these dispositional measures of both internalized and externalized shame may shed light on their relationships to maternal outcomes.

The generalizability of these results is limited by the relative homogeneity of the sample. The sample was largely Caucasian, married, and middle to upper-middle class. This socio-demographic group, however, is the group that is more susceptible to the pressures of the motherhood ideal and may be a group that is more likely to internalize high standards of ideal motherhood (Hays 1996). The ways in which self-discrepancies function to predict guilt and shame among women from different socio-demographic backgrounds merits further investigation. For example, it has been suggested that working class women are less likely to engage in intensive mothering behaviors (Lareau 2002), which may shield them from the internalized pressures of meeting the demands of this cultural ideal. On the other hand, not having the resources to meet the basic needs of their children may compound the guilt and shame experienced by working class mothers.

Although our research measured discrepancies between mothers’ sense of their selves and their vision of the “ideal” mother, future research may wish to distinguish between a mother’s internalized view of ideal motherhood and the view that she believes that society, or particular members of society such as her husband, holds. Although previous research that has differentiated these among mothers have found them to be highly correlated with one another (Polasky and Holahan 1998), they may be differentially related to guilt and shame. Other personality variables such as perfectionism, especially parenting perfectionism (Snell et al. 2005) should also be investigated within this context. If the desire to be a perfect mother increases the magnitude of the self-discrepancy experienced, it could exacerbate the experience of negative emotional outcomes (Higgins 1999). Women high in perfectionism may be more likely to view themselves as a bad mother and close to an undesired sense of self (Ogilvie 1987) when they do not meet their internalized ideals of motherhood.

Theorists and researchers have expressed concerns over the high standards for being a perfect mother that have become the dominant discourse for motherhood (Arendell 2000; Warner 2006). Our data suggest that the internalization of these high standards for ideal motherhood and the perception that one does not meet these standards is detrimental to mothers of young children. Internalization of the motherhood myth has been implicated as a source of guilt for mothers (Rotkirch 2009), and our data confirm this idea and expand it to the feeling of shame. Furthermore, fear of being judged by others exacerbates the impact of feeling that one is not living up to the internalized societal standards of motherhood. Women who have more realistic expectations for what it means to be a good mother may be protected from the potential detrimental effects of guilt and shame. Therefore, adjusting both societal and individual expectations for the standards of motherhood might benefit women’s mental health.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Alexander, M. J., & Higgins, E. T. (1993). Emotional tradeoffs of becoming a parent: How social roles influence self-discrepancy effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1259–1269. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.6.1259.

Arendell, T. (2000). Conceiving and investigating motherhood: The decade’s scholarship. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1192–1207. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01192.x.

Calogero, R. M., & Watson, N. (2009). Self-discrepancy and chronic social self-conciousness: Unique and interactive effects of gender and real-ought discrepancy. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 642–647. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.008.

Churchill, A. C., & Davis, C. G. (2010). Realistic orientation and the transition to motherhood. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 29, 39–67. doi:10.1521/jscp.2010.29.1.39.

Cook, D. R. (1994). Internalized shame scale: Professional manual. Menomonie, WI: Channel Press.

Deonna, J. A., & Teroni, F. (2008). Distinguishing Shame from Guilt. Consciousness and Cognition, 17, 725–740. doi:10.1016/j.concog.2008.02.002.

Elvin-Nowak, Y. (1999). The meaning of guilt: A phenomenological description of employed mothers’ experiences of guilt. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 40, 73–83. doi:10.1111/1467-9450.00100.

Franzoi, S. L., Vasquez, K., Sparapani, E., Frost, K., Martin, J., & Aebly, M. (2012). Exploring body comparison tendencies: Women are self-critical whereas men are self-hopeful. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36, 99–109. doi:10.1177/0361684311427028.

Gilbert, P. (1998). What is shame? Some core issues and controversies. In P. Gilbert & B. Andrews (Eds.), Shame: Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and culture (pp. 3–38). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gilbert, P. (2000). The relationship of shame, social anxiety and depression: The role of the evaluation of social rank. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 7, 174–189. doi:10.1002/1099-0879(200007)7:3<174:AID-CPP236>3.0.CO;2-U.

Gilbert, P. (2007). The evolution of shame as a marker for relationship security: A biopsychosocial approach. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robbins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 283–309). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Gonnerman, M. E., Jr, Parker, C. P., Lavine, H., & Huff, J. (2000). The relationship between self-discrepancies and affective states: The moderating roles of self-monitoring and standpoints on the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 810–819. doi:10.1177/0146167200269006.

Goss, K., Gilbert, P., & Allan, S. (1994). An exploration of shame measures. I: The ‘other as shamer scale’. Personality and Individual Differences, 17, 713–717. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(94)90149-X.

Guendouzi, J. (2005). “I feel quite organized this morning”: How mothering is achieved through talk. Sexualities, Evolution, & Gender, 7, 17–35. doi:10.1080/14616660500111107.

Guendouzi, J. (2006). “The guilt thing”: Balancing domestic and professional roles. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68, 901–909. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00303.x.

Hays, S. (1996). The cultural contradictions of motherhood. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Higgins, E. T. (1987). Self-discrepancy: A theory relating self and affect. Psychological Review, 94, 319–340. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.319.

Higgins, E. T. (1999). When do self-discrepancies have specific relations to emotions? The second-generation question of Tangney, Niedenthal, Covert, and Barlow (1998). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 1313–1317. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1313.

Kim, S., Thibodeau, R., & Jorgensen, R. S. (2011). Shame, guilt, and depressive symptoms: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 68–96. doi:10.1037/a0021466.

Lareau, A. (2002). Invisible inequality: Social class and childrearing in black families and white families. American Sociological Review, 67, 747–776. doi:10.2307/3088916.

Leary, M. R. (1983). A brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9, 371–376. doi:10.1177/0146167283093007.

Lee, C. (1997). Social context, depression, and the transition to motherhood. British Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 93–108. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8287.1997.tb00527.x.

Lindsay-Hartz, J., de Rivera, J., & Mascolo, M. F. (1995). Differentiating guilt and shame and their effects on motivation. In J. P. Tangney & K. W. Fischer (Eds.), Self-conscious emotions: The psychology of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride (pp. 274–300). New York: Guilford Press.

Marschall, D. E., Sanftner, J., & Tangney, J. P. (1994). The state shame and guilt scale. Fairfax, VA: George Mason University.

Mauthner, N. S. (1999). Feeling low and feeling really bad about feeling low”: Women’s experiences of motherhood and postpartum depression. Canadian Psychology, 40, 143–161. doi:10.1037/h0086833.

Ogilvie, D. M. (1987). The undesired self: A neglected variable in personality research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 379–385. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.52.2.379.

Ozgul, S., Heubeck, B., Ward, J., & Wilkinson, R. (2003). Self-discrepancies: Measurement and relation to various affective states. Australian Journal of Psychology, 55, 56–62. doi:10.1080/00049530412331312884.

Pavot, W., Fujita, F., & Diener, E. (1997). The relation between self-aspect congruence, personality, and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 22, 183–191. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00196-1.

Perälä-Littunen, S. (2007). Gender equality or primacy of the mother? Ambivalent descriptions of good parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 341–351. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00369.x.

Phillips, A. G., & Silvia, P. J. (2005). Self-awareness and the emotional consequences of self-discrepancies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 703–713. doi:10.1177/0146167204271559.

Pinto-Gouveia, J., Castilho, P., Galhardo, A., & Cunha, M. (2006). Early maladaptive schemas and social phobia. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30, 571–584. doi:10.1007/s10608-006-9027-8.

Polasky, L. J., & Holahan, C. K. (1998). Maternal self-discrepancies, interrole conflict, and negative self affect among married professional women with children. Journal of Family Psychology, 12, 388–401. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.12.3.388.

Rizzo, K. M., Schiffrin, H. H., & Liss, M. (2012). Insight into the parenthood paradox: Mental health outcomes of intensive mothering. Journal of Child and Family Studies,. doi:10.1007/s10826-012-9615-z.

Rotkirch, A. (2009). Maternal guilt. Evolutionary Psychology, 8, 90–106. Retrieved from http://www.epjournal.net/filestore/EP0890106.pdf.

Rubin, S. E., & Wooten, H. R. (2007). Highly educated stay-at-home mothers: A study of commitment and conflict. The Family Journal, 15, 336–345. doi:10.1177/1066480707304945.

Seagram, S., & Daniluk, J. C. (2002). “It goes with the territory”: The meaning and experience of maternal guilt for mothers of preadolescent children. Women & Therapy, 25, 61–88. doi:10.1300/J015v25n01_04.

Slevec, J. H., & Tiggemann, M. (2011). Predictors of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in middle-aged women. Clinical Psychology Review, 31, 515–524. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.12.002.

Smith, R. H., Webster, J. M., Parrott, W. G., & Eyre, H. L. (2002). The role of public exposure in moral and nonmoral shame and guilt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 138–159. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.138.

Snell, W. E., Overbey, G. A., & Brewer, A. L. (2005). Parenting perfectionism and the parenting role. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 613–624. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.02.006.

Sutherland, J. (2010). Mothering, guilt and shame. Sociology Compass, 45, 310–321. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2010.00283.x.

Tangney, J. P. (2002). Self-conscious emotions: The self as a moral guide. In A. Tesser, D. A. Stapel, & J. V. Wood (Eds.), Self and motivation: Emerging psychological perspectives (pp. 97–117). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10448-004.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002). Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford Press.

Tangney, J. P., Dearing, R. L., Wagner, P. E., & Gramzow, R. (2000). The test of self-conscious affect-3 (TOSCA-3). Fairfax, VA: George Mason University.

Tangney, J. P., Niedenthal, P. M., Covert, M. V., & Barlow, D. H. (1998). Are shame and guilt related to distinct self-discrepancies? A test of Higgins’s (1987) hypotheses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 256–268. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.256.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 345–372.

Tummala-Narra, P. (2009). Contemporary impingements on mothering. The American Journal of Psychoanalysis, 69, 4–21. doi:10.1057/ajp.2008.37.

Wall, G. (2010). Mothers’ experiences with intensive parenting and brain development discourse. Women’s Studies International Forum, 33, 253–263. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2010.02.019.

Warner, J. (2006). Perfect madness: Motherhood in the age of anxiety. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

Wasylkiw, L., Fabrigar, L. R., Rainboth, S., Reid, A., & Steen, C. (2010). Neuroticism and the architecture of the self: Exploring neuroticism as a moderator of the impact of ideal self-discrepancies on emotion. Journal of Personality, 78, 471–492. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00623.x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liss, M., Schiffrin, H.H. & Rizzo, K.M. Maternal Guilt and Shame: The Role of Self-discrepancy and Fear of Negative Evaluation. J Child Fam Stud 22, 1112–1119 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9673-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9673-2