Abstract

We investigated the associations among perceived fidelity to family-centered systems of care, family empowerment, and improvements in children's problem behaviors. Participants included 79 families, interviewed at two time points across a one-year period. Paired samples t-tests indicated that problem behaviors decreased significantly across a one-year period. Hierarchical multiple regressions indicated that both fidelity to family-centered systems of care and family empowerment independently predicted positive change in children's problem behavior over a one-year period. However, when family empowerment is entered first in the regression, the relationship between fidelity to family-centered systems of care and change in children's problem behavior drops out, indicating that family empowerment mediates the relationship between family-centered care and positive changes in problem behaviors. Consistent with other literature on help-giving practices, family empowerment appears to be an important mechanism of change within the system of care philosophy of service delivery. Implications for practice and staff training are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The emerging trend toward positive psychology and resiliency shifts the conceptual focus from a more deficit-based philosophy to a more family-centered, strengths-based philosophy of service delivery for children's mental health (Akos, 2001; Dunst, Boyd, Trivette, & Hamby, 2002). One innovative model of mental health service delivery lies within the system of care philosophy (Stroul & Friedman, 1986, 1996). Based on a family-centered program model, the system of care philosophy views families as fully capable of making informed choices given that professionals provide the additional support and resources needed to empower families and foster the development of new skills to create long-term change (Stroul & Friedman, 1986). However, little is known about the specific elements within family-centered care models that are the “active ingredients” of change among children and their families.

A system of care is a coordinated network of community-based services and supports that are organized to meet the challenges of children and youth with serious mental health needs and their families. Families and youth work in partnership with public and private organizations so that services and supports are, (a) effective, (b) build on the strengths of individuals, and (c) address each person's cultural and linguistic needs. A system of care helps children and families function better at home, in school, and in the community. A system of care typically provides services to a specific population of children, namely those children identified by mental health professionals as having a serious emotional disturbance (SED). Occurring in people between the ages of 1-to-21 years old, SED is defined as having at least one clinical diagnosis, functional impairment, and disturbances across multiple domains within the child's life (e.g., school, home, community) (Pumariega & Winters, 2003). The SED population is estimated to encompass approximately 4.5 to 6.3 million children (6–8%) in the United States (Friedman, Katz-Leavy, Manderscheid, & Sondheimer, 1999).

As a family-centered program model, the system of care philosophy views parents as partners in the treatment process in an effort to facilitate family empowerment (Dunst, Boyd, Trivette, & Hamby, 2002; Stroul & Friedman, 1996). Although there are many elements within family-centered care models in addition to empowerment (e.g., expanding social supports, utilizing family strengths, providing individually-tailored resources, delivering services consistent with cultural values and beliefs), empowerment is viewed by many as being the most important element for treatment success. For example, as Dunst, Trivette, and Deal (1994) explain, “it is not simply a matter of whether or not family needs are met, but rather the manner in which needs are met that is likely to have empowering consequences” (p. 3). By empowering families to develop possible solutions to problems or needs, the professional is not only helping with the current situation, but also helping the family develop skills to solve future problems independently. As family empowerment increases, the family unit becomes more competent and capable rather than dependent on service providers. Thus, it is possible that the construct of family empowerment is a possible mechanism of positive change above and beyond the positive influence of family-centered care.

Conceptually, it is not counter-intuitive that characteristics associated with empowerment such as promoting help-seeker independence and cultural relevance would influence not only treatment efficacy, but also have a positive influence on the family (Dunst & Trivette, 1996). Previous research (e.g., Dunst & Trivette, 1996; Dunst et al., 1994) has documented that the concept of empowerment has three main components. First, there is an underlying assumption that all people have existing strengths and are able to build upon these strengths. Second, a family's difficulty with meeting their needs is not due to their inability to do so, but rather, the unsupporting social systems surrounding the family that do not create opportunities for the family to acquire or display competencies. Third, in order for empowerment to have a positive influence on families, a family member who attempts to apply skills and competencies also must perceive the observed change as due at least in part to their efforts (Dunst et al., 1994). These main components have been more extensively researched and supported in several other studies. Coates, Renzaglia, and Embree (1983) reported that if service providers undermine a family's sense of competence or control over their life, learned helplessness can result. These patterns can not only produce dependence on professionals (Merton, Merton, & Barber, 1983), but also can decrease self-esteem and solicit negative feelings toward other family members (Nader & Mayseless, 1983).

Although there is a literature focused on the construct of empowerment, there is a dearth of research that examines empowerment in the context of community mental health service delivery for children with SED and their families. Since the development of the Family Empowerment Scale (FES; Koren, DeChillo, & Friesen, 1992), which assesses family perceptions of empowerment within the context of mental health services for their children, only a few studies have been published that utilize clinical populations, and these studies mostly have examined family empowerment in isolation of child functioning. For example, Curtis and Singh's (1996) cross-sectional study focused on demographic correlates of family empowerment, Singh et al.'s (1997) cross-sectional study focused on whether child diagnosis, demographic correlates, or parent support group membership influenced family empowerment, and Heflinger and Bickman's (1997) study focused on the use of a parent group curriculum to enhance family empowerment. Although all of these studies are important, there is limited information available as to how changes in family empowerment might be linked to changes in child functioning across time. One longitudinal study found that change in family empowerment predicted change in children's externalizing problems only (Taub, Tighe, & Burchard, 2001), but that study did not consider how the influence of family empowerment might be confounded with the positive influence of family-centered care overall. The only other longitudinal study that has been conducted with a clinical sample receiving family-centered, system of care services was correlational in nature (baseline and discharge empowerment correlations were reported in isolation) and did not examine how change in family empowerment influences change in child functioning (Resendez, Quist, & Matshazi, 2000).

To our knowledge, no studies have been conducted that examine the importance of family empowerment independent of the presumed positive influence of providing family-centered care. One previous study began to address this gap by documenting that there is a strong link between perceived fidelity to the system of care philosophy with both positive child outcomes and satisfaction with services (Graves, 2005). However, there continues to be a lack of information regarding the specific mechanisms of change. That is, what is it about delivering services consistent with a family-centered, system of care philosophy that leads to better outcomes?

Our study explores family empowerment as one possible mechanism of change. Based upon previous research and theory (e.g., Dunst et al., 2002; Graves, 2005; Stroul & Friedman, 1996; Taub et al., 2001), we hypothesized that, (1) children's problem behaviors would decrease over a one-year period while levels of family empowerment would increase, (2) greater family perceived fidelity to the family-centered elements of the system of care philosophy would be linked to greater positive change in child functioning, (3) greater levels of family empowerment would be linked to greater positive change in child functioning, and (4) family empowerment would mediate the relationship between family-centered care and positive change in child functioning.

Method

Participants

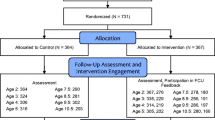

Participants were 117 children with severe emotional disturbance (SED) and their families who were enrolled in a North Carolina system of care program in one Center for Mental Health Services (CMHS)-funded grant site as part of the Comprehensive Mental Services for Children and Their Families Program. Eligibility criteria for enrollment was determined by CMHS for all demonstration grant sites, and included: a) being between the age of 5-and 18-years-old at intake, b) being a local county resident, c) having a clinical diagnosis, d) being separated or at risk of being removed from the home due to extreme behavioral or emotional difficulties, and e) having multiple agency needs. Of those 117 families, 5 families refused to participate in the evaluation and 14 families dropped out of the longitudinal program evaluation within the first year (12% attrition). Data were not available for the variables of interest in 19 families. Thus, the final sample for the present study was 79 families (N = 79). Group difference analyses indicated that there were no significant differences between those that remained in the study and those who dropped out in terms of demographic indicators such as age, t(91) = 1.70, ns, initial levels of children's total behavior problems, t (91) = .30, ns, or initial levels of family empowerment, t(91) = .78, ns.

Demographic information describing the sample (composed of children who have been identified as SED) is depicted in Table 1. All children had at least one clinical diagnosis, with the most common diagnosis being attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (AD/HD; 49%) followed by 38% with oppositional defiant disorder. See Table 1 for percentages of children falling in all diagnostic categories. In terms of psychotropic medication, 77% of children reported taking psychotropic medication when they entered services (Time 1), and 65% reported taking psychotropic medication one year later (Time 2). The specific type of psychotropic medication was not identified in data collection, and thus, could not be reported here.

Procedure

Children were referred to their local community mental health program from a variety of sources, including caregivers, child-serving agencies (e.g., Department of Social Services, Department of Juvenile Justice, Department of Public Health), and schools. Consent forms for treatment and for participation in the evaluation process were signed by the primary caregiver (or legal guardian if different from the caregiver) and the child, if age 11 or older. Families were informed that an interviewer would be contacting them within a few days to schedule an interview. Interviews were scheduled as soon as possible, but no later than 30 days after the initiation of services.

At baseline (Time One; T1) and one year later (Time Two; T2), trained evaluators conducted in-home interviews lasting approximately two hours for caregivers and one hour for children. All instruments were read to both children and their caregivers to minimize possible error due to differential reading abilities. Families received $25 for T1 interviews and $30 for T2 interviews; children received gift certificates donated from local fast food restaurants at both T1 and T2.

Service composition varied depending upon the individual needs of the child, resulting in different combinations of services and a different number of service providers for each participant. However, throughout the one year period, all children received case management, 80% received individual therapy, 38% received family therapy, and 33% received group therapy. Smaller percentages of families needed to access more restrictive services, with 15% receiving family preservation services and 15% receiving crisis stabilization services. All services were provided by local community mental health agencies and mental health non-profit organizations. After being trained in the system of care philosophy via pre-service workshops lasting two full days, service providers were encouraged to deliver services using system of care principles (child and family-centered, community-based, and culturally-competent). Supervisors monitored their staff members to ensure that system of care principles were being implemented. Booster workshop sessions were provided to ensure that service providers remembered and utilized the system of care philosophy in treatment planning.

Measures

Descriptive information questionnaire (DIQ; CMHS, 1997).

The DIQ is a 37-item caregiver-reported questionnaire that is completed at T1. The measure describes child and family characteristics such as age, race, ethnicity, risk factors, family structure, physical custody, referral source, presenting problems, family income living arrangements, education, household composition, physical health, and medications.

Fidelity to family-centered care.

Caregivers reported on the degree to which their services were delivered consistent with a family-centered approach at T2 using the Wraparound Fidelity Index 2.0 (WFI; Burchard, 2001). Two subscales from that scale were chosen that are specifically related to family-centered care, including Parent Voice/Choice and Cultural Competence. Each subscale contains four items that assessed the degree to which services were family-centered, with scores ranging from 0 (No), 1 (Sometimes), and 2 (Yes). A total score was created by summing all of the items into a total family-centered care score, with higher scores indicating greater adherence to a family-centered approach. Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) for the composite score was .79.

Child functioning.

Caregiver-reported child functioning was obtained at both T1 and T2 using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991). The earlier version of the CBCL was used at both T1 and T2 for measure consistency across time. The present study utilizes T-scores from the total problem behavior index. Internal reliability (>.82), test-retest reliability (>.87 for all scales), and validity have been demonstrated in previous studies (Achenbach, 1991).

Family empowerment.

Caregiver-reported family empowerment was obtained at both T1 and T2 using the Family Empowerment Scale (FES; Koren et al., 1992). The FES consists of 34 items rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (not true at all) to (very true). The FES has been identified to be a strong tool for evaluating the degree to which families acquired knowledge, skills, services, and resources from the mental health system for their children (Koren et al., 1992; Singh, 1995). A composite score of family empowerment was created by averaging the 34 items separately at T1 and T2. Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha) was .90 at T1 and .95 at T2.

Results

Descriptive analyses for all independent and dependent variables are presented in Table 2. Consistent with hypothesis one, paired samples t-tests indicated that there were significant improvements in child total problem behaviors from T1 to T2, t(78) = 4.79, p < .001, as well as a marginally significant change in levels of family empowerment from T1 to T2, t(78) = 1.51, p < .10. However, in order to examine what variables were associated with change more directly, additional analyses were conducted.

Zero-order correlations were computed among family empowerment, perceived fidelity to family-centered care, and children's total problem behaviors (as well as several demographic variables of interest). Those correlations are presented in Table 3. The correlations indicated the existence of some significant relationships between children's total problem behaviors, family empowerment, and perceived fidelity to family-centered care, but only at certain time points. Specifically, only total problem behavior at T2 (not at T1) was associated with perceived fidelity to family-centered care and family empowerment at T2. Family empowerment at T1 was positively correlated with family empowerment at T2. Family-centered care was positively correlated with family empowerment at T2 only, indicating that those families who feel more empowered also perceived greater levels of family-centered care. Children's total problem behavior at T1 was significantly, and positively, related to children's total problem behavior at T2. In terms of demographic variables, both child age and child gender were unrelated to family empowerment, total problem behaviors, or perceived fidelity to family-centered care. Although family income was positively correlated with family empowerment at T1, that relationship did not hold longitudinally, indicating that while income might be related to initial empowerment status, it is not an indicator of levels of empowerment after receiving services. Parental levels of education were unrelated to either family empowerment or perceived levels of family-centered care, but were linked with children's total problem behaviors at T1 only, with lower levels of parental education predicting higher levels of total problem behaviors. As expected, there was a strong positive correlation between family income and parental education.

To test hypotheses two and three, two hierarchical regression analyses were conducted. In the first analysis, perceived level of family-centered care was entered as a predictor of T2 children's problem behavior (controlling for T1 problem behavior). That analysis indicated that higher levels of family-centered care predicted lower levels of T2 problem behavior, t(78) = −2.12, p < .05, β = .27, even after controlling for baseline levels of behavioral challenges. In the second analysis, family empowerment at T2 was entered as a predictor of children's problem behavior at T2 (controlling for both empowerment and problem behavior at T1). That analysis indicated that higher levels of family empowerment at T2 predicted lower levels of problem behavior at T2, t(78) = −3.39, p <.01, β = −.37.

To test hypothesis four, mediational analyses were employed. As described by Baron and Kenny (1986), mediation is present when the following conditions are met: (1) changes in the level of the independent variable (family-centered care) accounts for changes in the proposed mediator variable (family empowerment), (2) changes in the proposed mediator variable (family empowerment) accounts for changes in the dependent variable (children's total problem behaviors), and (3) when the previous two relationships are controlled, a previously significant relationship between the independent variable (family-centered care) and the dependent variable (children's total problem behaviors) is no longer significant. The above-reported correlations and regression coefficients satisfy the first and second requirements of mediation. However, to test the third requirement, one additional hierarchical regression was conducted. In this analysis, T1 indicators were entered in the first step (problem behavior at T1 and family empowerment at T1), family empowerment at T2 was entered in the second step, and perceived fidelity to family-centered care was entered in the third step. The results of that analysis indicated that family empowerment continued to predict lower levels of children's problem behavior, but that the link between perceived fidelity to family-centered care drops out, t(78) = −1.44, ns, indicating that family empowerment is a mediator between family-centered care and changes in child functioning. The series of regressions conducted to address hypotheses two through four are reported in Table 4.

Discussion

We predicted that, (1) children's problem behaviors would decrease over a one-year period while levels of family empowerment would increase, (2) greater perceived fidelity to the family-centered elements of the system of care philosophy would be linked to greater positive change in child functioning, (3) greater levels of family empowerment would be linked to greater positive change in child functioning, and (4) family empowerment would mediate the relationship between family-centered care and positive change in child functioning. The results of the present study show clear support for several of these hypotheses. In regards to the first hypothesis, there were significant improvements in child total problem behaviors over the one year period for children who received system of care services. Thus, independent of the level of family-centered care and the level of family empowerment, children's behaviors improved. However, initial correlational analyses indicated that children's total problem behaviors were inversely related to the level of fidelity to family-centered care as well as to the level of family empowerment one year later.

Strong support was found for the second hypothesis that greater perceived fidelity to the family-centered elements of the system of care philosophy would be linked to greater positive change in child functioning. Thus, when children and families received services where they were included in the decision-making process and provided with services that were sensitive to their unique needs, values, and strengths, children's behaviors were more likely to improve over a one year period. Additionally, support was found for the third hypothesis that greater levels of family empowerment would be linked to greater positive change in child functioning. The results of the present study indicated that the more families were empowered to develop possible solutions to problems or needs, the greater improvement in terms of children's problem behaviors. Thus, empowering families appears to have a significant impact not only on the management of current problem behaviors, but also makes the family feel confident that they can successfully develop solutions to future problems.

Thus, findings indicated that when examined separately, both family-centered care and family empowerment predicted decreases in children's problem behavior over a one-year period. To follow-up on these findings, the fourth hypothesis, that family empowerment would mediate the relationship between family-centered care and positive change in child functioning, was tested next. The results of this mediational test indicated that once the variance accounted for by change in family empowerment was parceled out, family-centered care no longer directly predicted decreases in children's problem behaviors. Thus, family empowerment acts as a mediator between family-centered care and changes in child functioning and appears to be one important mechanism of change.

There are several strengths of this study, with perhaps the strongest being a closer empirical examination of the specific elements within family-centered care models that are the “active ingredients” of change among children receiving mental health services. Furthermore, the use of a clinical sample of children identified with a serious emotional and/or behavioral disturbance. The use of a clinical sample allows for the examination of theoretically-based analyses within the context of a clinically-referred population, and when combined with randomized samples, compliments the research base. However, it also is possible that the use of a clinical sample created a restricted range, which might have dampened the magnitude of the correlations among some of the variables. Based on this possibility, one might suspect that the current findings would have a stronger fit among a non-clinical sample. In a non-clinical sample, it is likely that there would be a wider range, allowing for more variation in the responses and identification of different relationships among the variables.

One limitation of the study is that information about perceived fidelity to the family-centered care element of the system of care philosophy was collected only from the caregiver. In future work, it would be informative to examine how consumer perceived fidelity compares to service provider perceived fidelity, and whether the same links hold for service provider reported fidelity to the system of care philosophy. Additionally, not all children with SED have been removed, or are at risk of being removed, from their homes (which was an eligibility criterion in the present study). Thus, the findings from the current study should be generalized only to those children who have SED and are at risk of being removed from their homes because of their emotional or behavioral difficulties. Although it was known how many children were taking psychotropic medications to help manage their emotional and behavioral difficulties, the specific type of medication was not known. Therefore, changes in functioning based on medication regimens could not be determined.

These findings indicate the family empowerment is an important factor in children's outcomes, suggesting that additional resources and services should be directed toward enhancing the empowerment of parents. Because the system of care philosophy appears to have some of its positive impact through family empowerment, there is a need to focus on those professional activities that lead specifically to increases in family empowerment such as involving families more in treatment planning. Some state that family empowerment should be the explicit and most important outcome for families and children who receive services for mental health challenges (Dunst et al., 1994), particularly among case management practices. Whether or not it is the most important outcome, the current findings advocate for the continued movement toward including parents as partners in the coordination, planning, and implementing of services for children, and for viewing parents not as part of the problem, but as the central resource for the child (Lourie & Katz-Leavy, 1986). Clearly, it is important to provide services that “not only sustain a person but also eventually make the person self-sustaining” (Brickman et al., 1983, p. 20).

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Child behavior checklist for ages 4–18. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychology.

Akos, P. (2001). Creating developmental opportunity: Systemic and proactive intervention for elementary school counselors. In D. S. Sandhu (Ed.), Elementary school counseling in the new millennium(pp. 91–102). Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Brickman, P., Kiddler, L. H., Coates, D., Rabinowitz, V., Cohn, E., & Karuza, J. (1983). The dilemmas of helping: Making aid fair and effective. In J. D. Fisher, A. Nadler, & B. M. DePaulo (Eds.), New directions in helping: Vol. 1, Recipient reactions to aid (pp. 17–49). New York: Academic Press.

Burchard, J. D. (2001). Wraparound fidelity index 2.1. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychology.

Center for Mental Health Services. (1997). The Descriptive Information Questionnaire. Unpublished measure.

Coates, D., Renzaglia, G. J., & Embree, M. C. (1983). When helping backfires: Help and helplessness. In J. D. Fisher, A. Nadler, & B. M. DePaulo (Eds.), New directions in helping: Vol. 1, Recipient reactions to aid (pp. 251–279). New York: Academic Press.

Curtis, W. J., & Singh, N. N. (1996). Family involvement and empowerment in mental health service provision for children with emotional and behavioral disorders. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 5, 503–517.

Dunst, C. J., Boyd, K., Trivette, C. M., & Hamby, D. W. (2002). Family-oriented program models and professional helpgiving practices. Family Relations, 51, 221–239.

Dunst, C. J., & Trivette, C. M. (1996). Empowerment, effective help-giving practices, and family-centered care. Pediatric Nursing, 22, 334–337.

Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Deal, A. G. (Eds.) (1994). Supporting and strengthening families. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books.

Friedman, R. M., Katz-Leavy, J. W., Manderscheid, R. W., & Sondheimer, D. L. (1999). Prevalence of serious emotional disturbance: An update. In R. W. Manderscheid & M. J. Henderson (Eds.), Mental health, United States, 1998 (pp. 110–112). Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Graves, K. N. (2005). The links among perceived adherence to the system of care philosophy, consumer satisfaction, and improvements in child functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14, 403–415.

Heflinger, C. A., & Bickman, L. (1997). A theory-driven intervention and evaluation to explore family caregiver empowerment. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 5, 184–196.

Koren, P. E., DeChillo, N., & Friesen, B. J. (1992). Measuring empowerment in families whose children have emotional disabilities: A brief questionnaire. Rehabilitation Psychology, 37, 305–321.

Lourie, I., & Katz-Leavy, J. (1986). Severely emotionally disturbed children and adolescents. In W. Menninger (Ed.), The chronically mentally ill (pp. 159–186). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Merton, V., Merton, R. K., & Barber, E. (1983). Client ambivalence in professional relationships: The problem of seeking help from strangers. In J. D. Fisher, A. Nadler, & B. M. DePaulo (Eds.), New directions in helping: Vol. 2, Helpseeking (pp. 13–44). New York: Academic Press.

Nadler, A., & Mayseless, O. (1983). Recipient self-esteem and reactions to help. In J. D. Fisher, A. Nadler, & B. M. DePaulo (Eds.), New directions in helping: Vol. 1, Recipient reactions to aid (pp. 167–188). New York: Academic Press.

Pumariega, A. J., & Winters, N. C. (Eds.) (2003). The handbook of child and adolescent systems of care: The new community psychiatry. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Resendez, M. G., Quist, R. M., & Matshazi, D. G. M. (2000). A longitudinal analysis of family empowerment and client outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 9, 449–460.

Singh, N. N. (1995). In search of unity: Some thoughts on family-professional relationships in service delivery systems. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 4, 3–8.

Singh, N. N., Curtis, W. J., Ellis, C. R., Wechsler, H. A., Best, A. M., & Cohen, R. (1997). Empowerment status of families whose children have serious emotional disturbance and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 5, 223–229.

Stroul, B. A., & Friedman, R. (1986). A system of care for children and youth with severe emotional disturbances (Rev. ed.). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Child Development Center, CASSP Technical Assistance Center.

Stroul, B. A., & Friedman, R. (1996). The system of care concept and philosophy. In B. Stroul (Ed.), Children's mental health: Creating systems of care in a changing society. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Taub, J., Tighe, T. A., & Burchard, J. (2001). The effects of parent empowerment on adjustment for children receiving comprehensive mental health services. Children's Services: Social Policy, Research, and Practice, 4, 103–112.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Child, Adolescent, and Family Branch of the Center for Mental Health Services within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (#SM52085-06). We are grateful to the entire staff of the System of Care Demonstration Sites for their help in data collection, entry, and checking. We also would like to thank the children and families who participated and dedicated their time to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Graves, K.N., Shelton, T.L. Family Empowerment as a Mediator between Family-Centered Systems of Care and Changes in Child Functioning: Identifying an Important Mechanism of Change. J Child Fam Stud 16, 556–566 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9106-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-006-9106-1