Abstract

This paper examines the prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among older persons of Punjab, the largest Province of Pakistan. Data were gathered from 4191 older persons aged 60+ using Probability Proportional to Size (PPS) of population. A version of the CES-D Scale adapted for low-literate populations was used to measure self reported depressive symptoms. Various independent factors, including socioeconomic factors, self-reported health conditions, and functional impairments were examined to see their net effect on depressive symptoms among older persons. Results of logistic regression analysis showed that region, area, living index, independent source of income, self-reported health conditions, and functional impairment were significant factors affecting self-reported depressive symptoms among older persons in Punjab. An important cross-cultural difference was a lower risk of depressive symptoms among older women, which may reflect the buffering effects of family co-residence and the position of seniors in extended families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pakistan is undergoing the demographic transition. Currently, elderly aged 60+ constitute 6 % of the total population. According to UN estimates this percentage will increase to 16 % by 2050 (UNDESA 2009). As a result of population aging, it is critical to address the health status of the elderly and, in particular, mental health. Many studies indicate that depression is a common mental health condition affecting older persons (Boey 1999; Lai and Tong 2009; Roberts et al. 1997). This research examines the prevalence and correlates of depressed mood among older adults in Punjab, the largest province of Pakistan.

Various factors have been identified as correlates or determinants of depression in old age. Among socio-demographic factors, gender is found to be significantly associated with depressive symptoms (Blazer et al. 1991; Barry et al. 2008; Mills and Henretta. 2001). Major depression is more common among women compared to men, particularly in late life (Barry et al. 2008; Krause 1986). The burden of depression is disproportionately higher among older women than men (Beekman et al. 1999; Heikkinen and Kauppinen 2004; Kivela et al. 1988). Women experience depressive symptoms to a greater degree and more frequently than men (Bracken and Reintjes 2009), almost twice as high (Culbertson 1997; Kessler et al. 1994). Many factors have been suggested to explain these differences, such as selective survival. For example, men die earlier and mortality may be affected by genetic factors (Yi et al. 2003).

Socioeconomic status is negatively associated with mental health and people with low socioeconomic status are found to be more depressed (Gresenz et al. 2001; Hay 1988; Muramatsu 2003). People with low socioeconomic status may encounter a greater number of stressful life events and have fewer resources to help them cope successfully with stressors (Aneshensel 1992; Dohrenwend and Dohrenwend 1969; Kessler and Cleary 1980; Kessler 1979; Thoits 1987). Financial strain is associated with psychological distress across the life course (Angel et al. 2003; Armstrong and Schulman 1990; Keith 1993; Krause 1997; Miech and Shanahan 2000; Mills et al. 1992; Mirowsky and Ross 2001; Voydanoff 1990).

Similarly, health is also a major concern of older persons. Poor physical health is significantly associated with higher levels of depression (Abbott et al. 2003; Lai 2000; Lam et al. 1997; Mui 1996; Mui et al. 2003). Health status is consistently associated with depressive symptoms (Blazer et al. 1998; Bruce 2001; Kraaij et al. 2002; Zeiss et al. 1996).

The association between depression and disability is well established by various researchers. People with disabilities are more likely to be depressed (Aneshensel et al. 1984; Bruce et al. 1994; Howell et al. 1981; MacDonald et al. 1987; Turner and Noh 1988; Vahle et al. 2000). Many studies indicate that the linkage between disability and depression is particularly relevant because disability prevents older persons from performing daily activities, and this in turn increases dependence on others and loss of control over activities (Bruce 2001; Johnson and Wolinsky 1999; Zeiss et al. 1996).

Little information is available on the mental health of the older population of Pakistan. For this reasons, we examined the prevalence of depressive symptoms in a population-based sample of older adults in the Punjab and examined determinants of depressive symptoms. We asked if socioeconomic factors and health conditions were each independent correlates of self-reported depressive symptoms. We wished as well to determine if correlates of depression identified in western countries applied as well to a low literate population in south Asia.

Materials and Methods

Sample

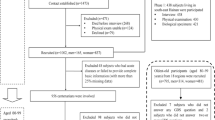

The sampling frame for the Pakistan ‘Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2007–08’ was developed by the Bureau of Statistics, Government of the Punjab. Rural and urban blocks of all the selected tehsils (sub-districts) were available in this frame. Within a tehsil, cities or towns were divided into enumeration blocks (EBs), which consisted on average of 200–250 households. Villages were divided into rural blocks, which consisted of an average of 250–300 households.

For sampling purposes, the province was divided into three regions: Central, Northern, and Southern. A four-stage cluster sampling design was used. At the first stage, about one-third of the districts from each of the three regions (10 in all: two from Northern Punjab, five from Central Punjab and three from Southern Punjab) were selected with probability proportional to size (PPS) of their population. At the second stage, about one-half of the tehsils from each selected district were selected with PPS of their population. At the third stage, urban and rural blocks were selected from each of the selected tehsils. In the case of 20 urban blocks or more, two were identified with the PPS of their population; while in case of less than 20 urban blocks, only one was identified based on PPS. For rural areas, almost 5 % of blocks were identified with PPS of their population. In all, 116 blocks were selected, of which 42 were urban and 74 were rural.

For each selected block, a sampling frame for eligible households was prepared. At the fourth and final stage, 40 eligible households (having at least one member aged 60 and above) for all selected urban and rural blocks were selected randomly. The total sample size came to 4,640.

It was decided before the field survey that one cluster would be covered in 1 day; and if the interviewer failed to find the respondent from any selected household, then he/she would consider the immediate next eligible household. Of the 4,640 selected households, 4,476 (96.5 %) were successfully interviewed. Of these, 285 respondents (6.4 %) were found to be aged less than 60. This group was excluded from the final analysis; thus the final sample size came to 4,191.

Measures

The outcome for this study was depressive symptoms measured using an adapted version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff 1977). The CES-D consists of items that assess negative affect (depressed, sad, lonely) positive affect (happy, enjoy, hopeful), somatic symptoms and retarded activity (poor appetite, restless sleep), and interpersonal difficulty (unfriendly, dislike, couldn’t get going, everything an effort). We used a 12-item version of the scale with each item scored never, sometimes, or often over the past 2 weeks. This version was used in the 2007 Philippine Longitudinal Study of Aging conducted by the University of the Philippines Population Institute (www.drdf-uppi.net/plsoa.htm). Consistent with the low literacy of the population, this version of the CES-D uses a 3-level response format, rather than the standard 4-level format. Scale scores range from 0 to 24. Scoring for positively worded items was reversed so that high scores represent higher levels of depressive symptoms. In the absence of clinically-defined cutoff scores for the measure, we developed a distribution-based measure of high depressive symptom burden. A scale score of 16 or greater from was used as the measure of depressive symptoms. The score of 16 corresponds to the top quartile in the distribution of scale scores. Potential correlates of depressive symptoms included demographic factors, economic status, physical health conditions, and Activities of Daily Living (ADL).

Socio-demographic variables consisted of region (north, central and south), residence (urban/rural), age (60–69, 70–79 & 80+), gender (male/female), education (none, primary, middle, secondary and higher), marital status (never married, married, separated/divorced and widowed).

Economic factors included whether respondents had an independent source of income and a computed living index. The Living Index was a count of eight household items: radio/radio cassette, television, landline telephone, cellular phone, washing machine, refrigerator/freezer, CD/VCD/DVD player, and personal computer. This household items index was also taken from the Philippine Longitudinal Study of Aging. We dichotomized the sample based on the median value of the score distribution. Respondents with < = 4 items were considered as having low living index, and respondents with >4 were considered to have a high level.

A composite variable of self-reported ailments was measured by considering five diseases: heart disease, joint pains, fractures, liver problems, and respiratory disease. An overall health condition score was derived by summing the number of conditions. Functional impairment was measured using activities of daily living (ADLs; bathing, dressing, taking meal, standing from bed/chair, going around the house, getting outside the house and toileting). For each task, participants rated difficulty from 0 to 2 (0 = not difficult to 2 = very difficult). An overall functional impairment index score was derived by computing average difficulty across items, with a higher score indicating more impairment.

Results

Descriptive statistics of all variables used in logistic analysis are given in Table 1. Half the respondents were from the central region of the Punjab. The majority of respondents (65.2 %) lived in rural areas, and almost half of the respondents were male. More than half (55.1 %) were in the age group of 60–69 years. About one third (30.7 %) reported ages of 70–79. 14.2 % were aged 80 or above. More than half (55.5 %) were married and 42.7 % widowed. Most respondents (72.1 %) had no education. Only 11.5 % had primary education. More than half (53.1 %) had at least one health condition. Almost one third (30.8 %) had high functional impairment. More than one third (34.1 %) of the respondents had an independent source of income.

After examining descriptive statistics for the sample, we developed multivariable logistic regression models to examine the independent association between depressed mood and demographic, economic, health, and disability indicators.

The results for multivariable logistic regression models are presented in Table 2. When only sociodemographic and economic variables were entered into the model, age, region, residence, independent source of income, and living index were significantly associated with self- reported depressive symptoms. Results indicate that respondents in the oldest old age category are 1.5 times more likely to have depressive symptoms when compared to reference group of age 60–69. Respondents living in central region were 21 % less likely to have depressive symptoms compared to older persons in south region, reflecting the greater economic distress of the southern Punjab. Similarly, older persons living in north region were 28 % less likely to have depressive symptoms. Older persons living in urban areas were 1.4 times more likely to have depressive symptoms compared to rural area. Older persons who did not have an independent source of income were 2.25 times more likely to have depressive symptoms compared to elderly who had independent source of income. Living index also showed that elderly with low living index were 2.72 times more likely to report high levels of depressive symptoms.

In a second multivariable logistic regression model (Table 3), functional impairment and self-reported health conditions were added as correlates to the previous socioeconomic indicators. Results showed that age was no longer a significant correlate of depressive symptoms. Region, area, living index and independent source of income remained significant correlates. Older persons with high functional impairment were 2.6 times more likely to have depressive symptoms compared to those with no impairment. Similarly older persons with one ailment and multiple ailments were 1.6 and 2.9 times more likely to have depressive symptoms respectively compared to older persons who had no ailment.

Figure 1 shows the independent contribution of socioeconomic status to risk of depressive symptoms. Within groups defined by chronic disease status, living index remained a significant correlate of depressive symptoms. Respondents with a low living index were 2–4 times more likely to report high levels of depressive symptoms after controlling for number of chronic conditions.

Discussion

In a large probability sample this research examined socioeconomic, health, and disability correlates of depressive symptoms among older adults in Punjab, Pakistan.

Contrary to earlier research showing women to be at higher risk of depression (Falcon and Trucker 2000; Lai 2004; Unutzer et al. 2003; Barry et al. 2008; Mills and Henretta. 2001), gender was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms in our analysis. A possible explanation of this finding could be that in Pakistani culture women live with their children, especially sons, and have high status in these extended households. Their guidance and suggestions are valued by their children. This valued position in the family may reduce the risk of depressive symptoms.

Results also indicate that in South Punjab elderly are more likely to report depressive symptoms relative to the North and Central region. This finding supports assumptions used in sampling methodology. For sampling purposes we divided the Punjab in three regions based on the assumption that socioeconomic conditions are relatively more distressed in the south region.

Elderly in urban areas were also more likely to report depressive symptoms. Various explanations could be put forward for this finding. First, in urban areas elderly might have a greater understanding of psychological symptoms and may have been more comfortable endorsing the presence of depressive symptoms. Secondly, due to urbanization, family members are busier with their own activities and may have less time for the older persons. Being alone or lonely in urban areas may contribute to older persons reporting more depressive symptoms.

This analysis also supports the role of financial status for risk of depressive symptoms. Elderly who did not have an independent source of income were more likely to report depressive symptoms. The reason could be that their dependency on others to meet their basic needs may be a source of distress in their life. Similarly, elderly who reported a lower living index also tended to have more depressive symptoms. This findings support other studies which document that financial stress leads to psychological distress (Gresenz et al. 2001; Miech and Shanahan 2000; Mirowsky and Ross 2001; Muramatsu 2003).

Findings of our study are consistent with other studies showing that health indicators are major risk factors for lower mental well being in later years of life (Abbott et al. 2003; Bruce 2001; Kraaij et al. 2002; Lai 2000). Our analysis shows that older persons with greater functional impairment are more likely to have depressive symptoms. Similarly, health complications were also found to be significantly associated with depressive symptoms. Health complications restrict older person’s independence and make them dependent upon others. Also, older persons with poor health status may not be able to enjoy other daily life activities and this may result in more stressful situations.

Health and financial status were independent correlates of depressive symptoms. In developing country like Pakistan, financial status seems to be important for risk of depressive symptoms apart from health status. Does lower level of financial status leave older persons in isolation? Does it increase their dependency and vulnerability? When is family support unable to buffer the effect of financial strain? These are some areas that need additional research.

Limitations of this study include its cross-sectional design and absence of a clinical criterion for depressed mood. Still, the absence of an increased risk of depressive symptoms among women in the Punjab suggests a potentially important cross-cultural difference in mental health. Co-residence with adult children in late life may raise the status of older women and provide key supports, in this way lowering the risk of depression in this otherwise vulnerable population.

References

Abbott, M. W., Wong, M. W., Giles, C., Wong, S., Young, W., & Au, M. (2003). Depression in older Chinese migrants to Auckland. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 37(4), 445–451.

Aneshensel, C. S. (1992). Social stress: theory and research. Annual Review of Sociology, 18, 15–38.

Aneshensel, C. S., Frerichs, R. R., & Huba, G. J. (1984). Depression and physical illness: a multiwave, nonrecursive causal model. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 25, 350–371.

Angel, R. J., Frisco, M., Angel, J. L., & Chiriborga, D. A. (2003). Financial strain and health among elderly Mexican-Origin individuals. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 536–551.

Armstrong, P. S., & Schulman, M. D. (1990). Financial strain and depression among farm operators: the role of perceived economic hardship and personal control. Rural Sociology, 55, 475–493.

Barry, L. C., Allore, H. G., Guo, Z., Bruce, M. L., & Gill, T. M. (2008). Higher burden of depression among older women: the effect of onset, persistence, and mortality over time. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65(2), 172–178.

Beekman, A. T., Copeland, J. R., & Prince, M. J. (1999). Review of community prevalence of depression in later life. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 174, 307–311.

Blazer, D., Burchett, B., Service, C., & George, L. (1991). The association of age and depression among the elderly: an epidemiologic exploration. Journal of Gerontology, 46, 210–215.

Blazer, D., Landerman, L., Hays, J., Simonsick, E., & Saunders, W. (1998). Symptoms of depression among community-dwelling elderly African-American and White older adults. Psychological Medicine, 28, 1311–1320.

Boey, K. M. (1999). Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14, 608–617.

Bracken, B. A., & Reintjes, C. (2009). Age, race, and gender differences in depressive symptoms: a lifespan developmental investigation. Journal of Psycho Educational Assessment, 28(1), 40–53.

Bruce, M. (2001). Depression and disability in late life: direction for future research. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 9, 99–101.

Bruce, M. L., Seeman, T. E., Merrill, S. S., & Blazer, D. G. (1994). The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur studies of successful aging. American Journal of Public Health, 84, 1796–1799.

Culbertson, F. M. (1997). Depression and gender: an international review. American Psychologist, 52, 25–31.

Dohrenwend, B. P., & Dohrenwend, B. S. (1969). Social status and psychological disorder: A causal inquiry. New York: Wiley.

Falcon, L. M., & Trucker, K. L. (2000). Prevalence and correlates of depressive symptoms among Hispanic elders in Massachusetts. Journal of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 55(2), S108–S116.

Gresenz, C. R., Sturm, R., & Tang, L. (2001). Income and mental health: unraveling community and individual level relationships. The Journal of Mental Health Policy and Economics, 4(4), 197–203.

Hay, D. I. (1988). Socioeconomic status and mental health status: a study of males in the Canada, health survey. Social Science & Medicine, 27(12), 1317–1325.

Heikkinen, R. L., & Kauppinen, M. (2004). Depressive symptoms in late life: a 10-year follow-up. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 38(3), 239–250.

Howell, T., Fullerton, D. T., Harvey, R. F., & Klein, M. (1981). Depression in spinal cord injured patients. Paraplegia, 19, 284–288.

Johnson, R., & Wolinsky, F. (1999). Functional status, receipt of help, and perceived health. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology, 5(2), 105–125.

Keith, V. M. (1993). Gender, financial strain, and psychological distress among older adults. Research on Aging, 15, 123–147.

Kessler, R. C. (1979). A strategy for studying differential vulnerability to the psychological consequences of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 20, 100–108.

Kessler, R. C., & Cleary, P. D. (1980). Social class and psychological distress. American Sociological Review, 45, 463–478.

Kessler, R. C., McGonagle, K. A., Zhao, S., Nelson, C. B., Hughes, M., Eshleman, S., Wittchen, H. U., & Kendler, K. S. (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the national comorbidity survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 8–19.

Kivela, S. L., Pahkala, K., & Laippala, P. (1988). Prevalence of depression in an elderly population in Finland. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 78(4), 401–413.

Kraaij, V., Arensman, E., & Spinhoven, P. (2002). Negative life events and depression in elderly persons: a meta-analysis. Journal of Gerontology B: Psychological and Social Sciences, 57, 87–94.

Krause, N. (1986). Stress and sex differences in depressive symptoms among older adults. Journal of Gerontology, 41, 727–731.

Krause, N. (1997). Anticipated support, received support and economic stress among older adults. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 52, 284–293.

Lai, D. W. L. (2000). Prevalence of depression among the elderly Chinese in Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 91(1), 64–66.

Lai, D. W. L. (2004). Impact of culture on depressive symptoms of elderly Chinese immigrants. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 49(12), 820–827.

Lai, D. W. L., & Tong, H. M. (2009). Comparison of social determinants of depressive symptoms among elderly Chinese in Guangzhou, Hong Kong, and Taipei. Asian Journal of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 4, 58–65.

Lam, R. E., Pacala, J. T., & Smith, S. L. (1997). Factors related to depressive symptoms in an elderly Chinese American sample. Clinical Gerontologist, 17(4), 57–70.

MacDonald, M. R., Nielson, W. R., & Cameron, M. G. (1987). Depression and activity patterns of spinal cord injured persons living in the community. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 68, 339–343.

Miech, R. A., & Shanahan, M. J. (2000). Socioeconomic status and depression over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 162–176.

Mills, T. L., & Henretta, J. C. (2001). Racial, ethnic, and sociodemographic differences in the level of psychosocial distress among older Americans. Research on Aging, 23(2), 131–152.

Mills, R., Grasmick, H. G., Morgan, C. S., & Wenk, D. (1992). The effects of gender, family satisfaction, and economic strain on psychological well-being. Family Relations, 41, 440–445.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (2001). Age and the effect of economic hardship on depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(2), 132–150.

Mui, A. (1996). Depression among Chinese immigrants: an exploratory study. Social Work, 41(6), 633–645.

Mui, A. C., Kang, S. Y., Chen, L. M., & Domanski, M. D. (2003). Reliability of the geriatric depression scale for use among elderly Asian immigrants in the USA. International Psychogeriatrics, 15(3), 253–271.

Muramatsu, N. (2003). County- level income inequality and depression among older Americans. Health Service Research, 38, 1863–1884.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Roberts, R. E., Kaplan, G. A., Shema, S. J., & Strawbridge, W. J. (1997). Does growing old increase the risk for depression? The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(10), 1384–1390.

Thoits, P. A. (1987). Gender and marital status differences in control and distress: common stress versus unique stress explanations. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 28(1), 7–22.

Turner, R. J., & Noh, S. (1988). Physical disability and depression: a longitudinal analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 29, 23–37.

UNDESA (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs). (2009). World population prospects: The 2008 revision. New York: United Nations.

Unutzer, J., Katon, W., Callahan, C. M., Williams, J. W., Jr., Hunkeler, E., Harpole, L., Hoffing, M., Della Penna, R. D., Noel, P. H., Lin, E. H., Tang, L., & Oishi, S. (2003). Depression treatment in a sample of 1,801 depressed older adults in primary care. Journal of American Geriatric Society, 51(4), 505–514.

Vahle, V. J., Andresen, E. M., & Hagglund, K. J. (2000). Depression measures in outcomes research. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 8, 53–62.

Voydanoff, P. (1990). Economic distress and family relations: a review of the eighties. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 1099–1115.

Yi, Z., Yuzhi, L., & George, L. K. (2003). Gender differentials of the oldest old in China. Research on Aging, 25, 65–80.

Zeiss, A. M., Lewinsohn, P. M., Rohde, P., & Seeley, J. R. (1996). Relationship of physical disease and functional impairment to depression in older people. Psychology and Aging, 11(4), 572–581.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Islamabad, Pakistan and by NIH P30 MH090333.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maqsood, F., Flatt, J.D., Albert, S.M. et al. Correlates of Self-Reported Depressive Symptoms: A Study of Older Persons of Punjab, Pakistan. J Cross Cult Gerontol 28, 65–74 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-012-9183-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-012-9183-0