Abstract

Contract cheating is a growing menace that most academic institutions are grappling with globally. With governments now taking steps to help combat the industry and ban such services, it is also important to encourage students to stay away from such services through proactive strategies to raise awareness so that students stop using such services. This paper uses a case study approach to capture a time-series data from three years of a university campus’s efforts to raise awareness by celebrating the International Centre for Academic Integrity (ICAI)‘s International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating. This is in order to explore if such campaigns can be used as tools to increase student understanding of contract cheating as an academic misconduct issue and what roles students can play in raising awareness among other students on contract cheating. Proposing to look at contract cheating as a social issue, the paper positions the misconduct as such and explores how awareness campaigns can help address contract cheating. Over the three years, results show steep increase in awareness of contract cheating, a type of academic misconduct, and that students themselves have a positive influence on other students when raising awareness. An interesting finding of the study is that graduated students have had an impact by showing responsibility to younger students and by actively denouncing contract cheating companies and their approaches on social media; thus providing solid evidence that awareness campaigns can help increase awareness which is the first step towards building a culture of integrity in any campus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Trying to create a culture of integrity can feel like an uphill battle. Building a culture of integrity may be the best weapon against academic misconduct (Khan 2014; Peters 2019). Student cheating is not a new phenomenon and researchers and academics have grappled with this issue for generations. Every generation of teachers feel they are having it worst, with newer, sneakier ways students cheat in and out of classrooms (Bowers 1964; McCabe and Bowers 1994; Anderman et al. 1998; Callahan 2004; Christensen-Hughes and McCabe 2006; Khan and Balasubramanian 2012). With the infiltration of technology in today’s blended classrooms, the challenges are as complex as they are supposed to be varied (Khan and Balasubramanian 2012; Khan 2019). However, the problem remains the same – that of loss of academic integrity inside classrooms and what that means for the greater society.

Academic misconduct has been defined as any action that gives a student an unfair advantage such as cheating in exams, using resources not permitted, collaborating without consent, submitting work not done by themselves, copying and pasting work from another source as their own, fabricating data, impersonating another student, interfering or obstructing other students’ work and so on (UOW 2019). Literature has captured umpteen amount of statistics demonstrating the levels of cheating in schools, universities, entrance exams, and other forms of academic misconduct. Incidences of misconduct as evidenced in literature was captured aptly in an extensive data compiled by Dr. Donald McCabe at the International Centre for Academic Integrity. The dataset compiled showed survey results of studies conducted between 2002 and 2015, and showed “64% of students admitted to cheating on a test, 58% admitted to plagiarism, and 95% said they participated in some form of cheating, whether it was on a test, plagiarism or copying homework” (ICAI 2019) This makes academic integrity a vital part of education system. As academics we strive to instill the Fundamental Values as recognized by International Centre for Academic Integrity, these being honesty, trust, fairness, responsibility, courage and respect (AcademicIntegrity.org 2014). But how do we go about instilling these values in our students?

Literature has highlighted different ways schools and universities have attempted to understand why students cheat (Khan 2014; Simkin and McLeod 2010; Yu 2018) and how to detect and curb misconducts (Cutler 2019; McCabe and Katz 2009; D’Souza and Siegfeldt 2017).

With the onset of technology, Khan (2014) posited the impact of policy and university culture and value of technology to ward off negative impact of technology, recognizing e-cheating as a predominantly prevalent one since the increase in dependency on technology, adding to an exhaustive list of misconduct behaviors recognized previously by Newstead et al. (1996).

Of interest to this research is one type of academic misconduct – that of buying and selling assessments. Due to proliferation of websites, buying and selling of assessments, known commonly as contract cheating (Clarke and Lancaster 2006), is “prevalent and difficult to detect” (Clarke and Lancaster 2014, p 2). It would seem with the rise of the internet, ease of setting up a website and e-commerce, essay mills have transformed into e-mills that are rampant, mushrooming all over the digital space, flooding students’ mailboxes and hounding them on social media (Clarke and Lancaster 2013; Lancaster and Clarke 2016; Wallace and Newton 2014; Rigby et al. 2015; Foltynek and Kralikova 2018), thus creating an availability heuristic of readily available solutions to completing assessments, a method through which the mind recollects and helps make fast decisions, albeit sometimes inaccurately (Fox 2006).

To help deter students from contract cheating, although recent studies have attempted to aid academics through researching areas such as legal approaches (Draper and Newton 2017) detection (Rogerson 2018), analyzing the advertisements (Kaktins 2018), so on, we believe the focus needs to be more proactive, than reactive. This is because reactive response works only after an incident has occurred, thus becoming more “consequences or reactions to” the behavior or issue (Champlin 1991). Champlin also posits that reactive strategies aim to minimize damage rather than prevent. Whereas, proactive strategies are preventive by nature, and help to “reduce the likelihood of occurrence of challenging behavior [or issue]” (Champlin 1991).

Thus, the research question we posed was “given that contract cheating is a global menace affecting the quality of education in schools and universities, how can we step up our proactive efforts in mitigating contract cheating, and empowering students with a culture of integrity?”

This paper looks at the case of one campus that has used systematic campaigning to test the awareness level of student body on the issue of contract cheating by first looking at contract cheating as a social issue, then making a case for awareness campaigns as proactive strategies and then testing the impact of such campaigns to create a pathway to develop a culture of integrity.

Contract Cheating – More than an Academic Issue

Known commonly now as contract cheating, essay mills are not new. Dating as far back as mid nineteenth century where fraternity houses hosted essay mills in their basements and encouraged recycling of submitted essays, these fraternity essay mills transformed into ghostwriting and the modern-day contract cheating that researchers and academics are vehemently opposing, calling for bans on such practices, promotion of such services and illegalizing such businesses (Singh and Remenyi 2015).

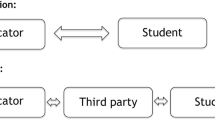

Contract cheating has become prevalent globally, with universities trying to find ways to tackle it. Authors posit that contract cheating, like other misconducts, is not only an academic issue, but also a social one. Social issue is defined as:

“a condition… defined by considerable number of [people] as a deviation from some social norm which they cherish” ( Fuller and Myers 1941 , pp 320–21).

If we apply this definition to contract cheating (or any other misconduct), this is how it would map out:

Social Norm = To be tested on learning outcomes through formative or summative assessments

Cherish = Stakeholders don’t consider buying essays favourable (Lane, 2017; Dawson and Sutherland-Smith 2017; Khomami 2017; Grove 2017; Marsh 2017), rather academics, and community cherish and want to see students display values such as truthfulness, honesty, courage, fairness, trust and responsibility and respect (AcademicIntegrity.org 2014)

Deviation = act of contract cheating.

When applied as above, given the range of direct, long term and surrounding impacts of contract cheating and the definition of social issue, for the purpose of this study, contract cheating may be considered as a social issue.

Looking closely at “social issue”, social issues typically have impact on the person involved (in this case, we will define this person as the victim for reference purpose only), his/her family, friends, dependents, society. This is demonstrated in the Table 1 with some examples and the subsequent Fig. 1:

All identified social problems highlighted above may be further categorized into three areas of impact, that is, impact on self which is direct, impact on self which is long term and impact on surrounding of the victim. As illustrated in the Fig. 1, each of the social issues mentioned in Table 1 have a direct impact on the victim’ self. For instance, literature has posited that bullying leads person bullying to anxiety, aggression, insecurity and loneliness, direct results of bullying behavior (Juvonen, et al. 2006). Similarly, alcoholism directly impacts alcoholic with performance at school, low consciousness (Stewart, et al. 2001), while racism impacts racist with isolation (Lowe, et al. 2012) and drug abuse leads to low self-esteem, sensation seeking (Newcomb, et al. 1986).

Based on a review of the literature, some long-term impacts on the victim includes poor mental health, depression, suicide for all types of social issues (as shown in Table 1 above). These long-term impacts on the victim also result in impact on victim’s surrounding which can include family, friends, workplace, school and the community. For instance, if a drug addict commits suicide, the addict’s family, friends and community are impacted. If the addict was a provider, the family would suffer because they lose not only a loved one but also a source of income (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 2004).

Figure 1 above paves way to a better understanding of why contract cheating can be considered as a social issue. For instance, we know from literature that any kind of academic misconduct including contract cheating has negative impacts on the individual student and the academic community at large as discussed in previous sections and further mapped in Fig. 2 below.

Given what the literature says about social issues and contract cheating, and the mapping exercise carried out above, we believe there are grounds to consider contract cheating as a social issue. This is further supported by Harp and Taints (1966) who likened student cheating to “sociological deviance” where they suggested the “sociological deviance involve[d] a consideration of the norms to which the members of the system [were] oriented and subsequent deviation from the expectations of others” (Harp and Taietz 1966; p 365).

Building a Case for Campaigns

To alleviate contract cheating, Awdry and Newton (2019) provide research, which strongly recommends measures and actions to avoid or eliminate such practice. In the case of contract cheating, there has been strong support for government institutions to eliminate the existence of outsourcing firms who are easily accessible to students to complete their essay /assignments needs at a cost (Khomami 2017; Marsh 2017).

However, as mentioned before, most solutions offered are often reactive, rather than proactive. We wanted to device proactive strategies so that we could tackle contract cheating. Studies have shown that awareness campaigns are a proactive means directed at helping to reduce impacts of a social issue. Campaigns aim to educate victims, family, friends and community on the social issue, what its signs are, its impact and how a community can work to help address and mitigate the issue in a more positive manner.

The advantages of hosting awareness campaigns to combat a social issue have been proven to be highly effective (Seymour 2017). Campaigns are organized to provide greater insights about the social issue in detail, and raise awareness about better identifying and mitigating such issues. The resultant target group is better informed about the impacts of that social issue, benefits from networking with organizations and media, focused on helping people mitigate such issues on an individual, family, community and social level (Dietrich et al. 2009).

An example of an international campaign held in the United States of America (USA) is the “Project on Death in America” that was aimed at addressing discussions surrounding death and bereavement, and end-of-life care in the community. The campaign led to the following advancements (Seymour 2017):

- 1.

research and development program developed surrounding the cause

- 2.

greater communication platforms established in the arts, music, and humanities field to identify and address issues surrounding illness, and death

- 3.

increase and advancement of community and organizational initiatives to tackle grieving.

Another example of an awareness campaign includes educating target groups on the dangers behind alcohol misuse in schools. This campaign was designed in the form of education-based intervention, along with studies undertaken on participants across 10 schools in Sydney, Australia. Results post the implementation depicted positive results where the mean alcohol consumption levels significantly dropped post the intervention (Newton et al. 2009).

Similarly, campaigns targeted at social issues such as HIV and AIDS education, as well as mental health such as anxiety, have consistently depicted greater understanding of the social issues amongst students, and enabled greater discussion of the issues amongst students. Post-intervention results carried out, depicted reductions in negative perceptions surrounding AIDS, and lower levels of anxiety amongst students (Kleppe et al. 1997; Neil and Christensen 2009).

Online communities and social media campaigns further help address issues under the wider umbrella of the social issue, thus enabling expansion of raising awareness across the network of schools and universities (ZN 2013). In turn, this also improves effectiveness to the intervention process. Additionally, such campaigns, when expanded on a larger scale, enable people to change their perceptions about the issue at discussion, and promote suitable responses from the policy makers themselves (Seymour 2017).

It is believed that body of existing literature strongly supports the use of campaigns to tackle social issues. As we have posited contract cheating to be considered as a social issue, then to combat contract cheating, this paper thus proposes and examines the treatment of such behaviour by organizing ‘awareness campaigns’ in universities to develop a culture of integrity on campus.

Therefore, the research objectives for the rest of the paper are to explore awareness campaigns for social issues such as contract cheating and develop understanding of:

whether awareness campaigns can increase student understanding and awareness of contract cheating as a misconduct

roles students can play in raising awareness among other students on contract cheating

Research Methodology

This study has been conducted in a university campus housed in a middle eastern country where sporadic research has been conducted in the last few years on academic integrity and specifically contract cheating. The campus is multidisciplinary and is home to students from more than 100 nations. The university campus has undergraduate and postgraduate studies offered to more than 4000 student population. The study looks at undergraduate (UG) students as a sample population as purposive sampling, however declares a limitation in that participation from students was voluntary. It is also crucial to mention here that the campus is highly active with day-time events organized for students that are driven by the student services department of the university. This precludes postgraduate (PG) students as PG subjects are offered in the evenings to student population that is largely part time students and full-time employers/employees externally.

Unfortunately, this limitation in devising and hosting events also means very targeted activities planned in the evenings and after office hours can involve PG students, but which poses difficulties as other resources then become scarce, for instance UG students and student clubs that run activities during day time. So, the sample population therefore stands to be UG students.

In this study we compared undergraduate student awareness of contract cheating, and student understanding of contract cheating as a misconduct, before and after a series of awareness activities that were carried out on the campus. This study used exploratory case report method (Yin 1984) that has gained reputation over the years as an effective methodology particularly when investigating complex issues in areas such as social sciences, education and even business (Harrison, et al. 2017).

“Case study is a research approach that is used to generate an in-depth, multi-faceted understanding of a complex issue in its real-life context. It is an established research design that is used extensively in a wide variety of disciplines, particularly in the social sciences”

(Crowe et al. 2011)

Case study approach aims in reaching to the grassroot level of the problem and providing effective solutions supported by adequate research (Heale and Twycross 2017). The ease of access of them in the form of digital content as well as published papers makes it a preferred source of knowledge.

Certain case studies have highlighted various social issues existing in this society supported by evidences and needed solutions to overcome such challenges.

The case for this paper was developed based on time series over three years of data collected before and after the celebration of the International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating. We felt this method allowed us to go beyond the “statistical results and really understand the behavioral conditions through the [students’] perspective” (Tellis 1997), at the same time allowing us to include both qualitative and quantitative data from various sources.

The Case Study

The chosen university is a multinational campus in a middle eastern country, that showcases a 4000 strong student body across undergraduate and postgraduate programs. It offers a multitude of programs at each level, maintaining a high standard of delivery through various government and non-government accreditations nationally and internationally. An institution that has been in the region for decades, the campus attracts faculty from across the globe, teaching an international body of students who come from various schooling systems and cultural backgrounds. The institution is a leading campus researching and promoting academic integrity in the region.

On 17 October 2016, the International Centre for Academic Integrity (ICAI USA) declared the Global Ethics Day (a day marked by Carnegie Mellon) as also the International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating. ICAI decided to run white-board pledges and invited campuses across the world to join hands to run similar campaigns asking students and staff to write down their statements against contract cheating with “I Do Not Contract Cheat because…. #defeatthecheat #excelwithintegrity” as shown in Figs. 3 and 4 below and post them on social media.

The First Year

The chosen university planned and decided to participate in the “white board campaign” in the first year. The primary author was also the convener for the campaign on campus. This first year, only a white board campaign was planned for the campus. Planning including:

acquiring permission from management to conduct the campaign,

acquiring permission to use consent forms that would also allow video/photo release consent from participants. The consent forms explained the campaign to students, asked them for their consent to participate and their permission to take their photo and post them on social media. The institution had a standard Video/Photo/Opinion Release Form that the team used for this purpose adding the following questions:

It is important to note here that the two questions posed used binary survey (BS) style instead of ordinal multi-category answer (MCA) formats (eg. Likert scale). Although MCA formats are more common and rule academic research (Likert, 2010), comparative studies of the two formats have shown that using BS does not impact the validity of the survey instrument making them equally reliable (Grassi et al. 2007; Dolnicar et al. 2011) and interpretations made do not vary (Dolnicar et al. 2011). Furthermore, the motivation to use BS format was that it is perceived to be less complex and quick, reducing cost and fatigue thus increasing data quality and response rates (Dolnicar et al. 2011).

The question card was not included as part of consent form to ensure anonymity of answers. Method followed is described below:

An email was sent to faculty inviting them to participate with their students, sending the board design and release form as attachment.

Flyers of the campaign were posted around the campus and asked to contact third party research assistants who became contact points for students who were interested to participate. Although the posters were put up on common area notice boards, response was from UG students as expected.

The assistants then captured student feedback before the whiteboard pledge campaign based on the above two simple questions provided to participants.

Students were free to choose to participate or not participate at any time of the process as per the institutional release form and policy.

To create an educative experience, students were then given the following details on contract cheating:

- 1.

nature of the misconduct,

- 2.

why it was considered a misconduct, and

- 3.

how the institutional policy viewed and dealt with such misconduct

as part of conversation they had with the research assistants. They were asked to put down their pledge and have their photographs taken if they so wanted to after providing their consent.

A total of 30 students participated in the first year of the campaign.

The Second Year

During the second year, the institution decided to organize the campaign once again, targeting the International Day of Action Against Contract Cheating once again. The team approached student services and library to join hands to reach more students. This time student clubs, the representative council and two students who had participated in the previous year decided to join in the organizing of awareness campaigns on campus with undergraduate students. Under the guidance of the primary author, the team developed a week-long program for the campus. These events included:

- 1.

psychological mind frame workshops hosted by counsellors,

- 2.

painting and design competitions,

- 3.

plenary sessions with registrars and students on the consequences of misconduct and effectiveness of policies and procedures

- 4.

faculty and student colloquium with seven fast-presentations (seven minutes each) of volunteer-faculty and students who shared their experiences with misconducts in general and discussed contract cheating

- 5.

library screen campaign that provided information across 19 slides about contract cheating

- 6.

authors and marketing developed a series of info and campaign flyers to be used during every event

All the events were carried out before the final day of the event which marked the “whiteboard pledge campaign”. Like previous year, the same two questions were posed to the sample population of voluntary respondents. Email was once again sent to all staff and flyers put up on notices inviting students to participate.

This time, more than 40 students volunteered to participate in the campaign.

The Third Year

In its third year, the chosen university staff and students displayed curiosity and interest as students from previous years came forward and once again wanted to join the team to organize the awareness campaigns. It is important to note here that as all activities were conducted by third party and forms collected anonymously, it was not possible to actually track how many students were repeating their participation year on year. This time there were three students who came forward to help organize the campaign. Of students who had taken part in the actual events, one graduated and had a startup company that then offered prizes for various competitions planned.

Similar events as of second year were organized and the week of activities ended with the white-board pledge day as before. This time, the campaign also saw participation of another university campus that was invited to join and four PG students due to collaboration with a PG faculty. However, the external university faculty and PG students participated in the panel discussion only.

More than 60 students participated in the consent and white board campaign.

Results

Using the whiteboard messages, consent forms, social media messages and posts and follow up conversations that took place between the research assistants and the participants, it was observed during the first year from their responses, that of the 30 students who voluntarily participated in the pledge campaign, none of the students were aware of the term “contract cheating” nor were they aware that such action could be “deemed” as a misconduct or cheating, let alone that it was “in the policies”, as they discussed with the research assistants. In fact, students who volunteered to participate in the campaign were hesitant and not sure if it was a “safe event” to participate in. Students expressed they had reservations the first time they participated as it was first such event on campus but once they did participate, they realized it carried no risks.

During the second year of the celebrations, of the 40 students who volunteered to participate, more than 70% of them knew what contract cheating was and knew it was a misconduct. This was a marked increase from the previous year.

By the third year, more than 80% of the students taking the pledge showed awareness and understanding this time.

Table 2 below provides descriptive statistics of the campaign questions to gain understanding of whether students knew what contract cheating was and whether they knew that using online essay writing services was considered cheating. Descriptive statistics have been used successfully by Orr (2018) when understanding student perception of an academic integrity educational seminar disseminated on campus, and hence have been adopted here.

Figure 5 below illustrates the comparison of the results across the three years.

Qualitative feedback from students were also very positive such as “participating in this event was so much fun, I didn’t realis such services could be considered as cheating”, “we get approached all the time by such services but I never knew they were actually promoting cheating”, “I will definitely read the policy and find out about the other actions that are considered cheating”, “I loved participating and writing a pledge”, “Writing a pledge and taking my photo was fun”.

The above feedback from students show how the campaigns impacted student’s awareness and understanding of contract cheating.

It is also important to note here that undergraduate students who had participated in the first two years of campaign either as respondents and pledge takers or as organizers, had graduated by the third year (three of them in total who willingly identified themselves). They then shared their stories and experiences of how they had begun to track companies that targeted students on social media and started reporting them to the campus authorities and raised voice against such ads, pop ups and messages on social media to help raise awareness of current students (see Fig. 6.

Lessons Learnt and Future Scope

This study highlighted the extensive process authors went to develop a campaign against contract cheating on campus. Several lessons were learnt that are shared below.

Identifying contract cheating as a social issue has its merits. Laura Hudgens, a teacher and a parent voiced frustration over the fact that parents talk about and worry about students’ drinking, substance abuse, safety and health, but not about cheating because they don’t see the threat as they would any other social issue (Hudgens 2019). Then, it becomes imperative that we change people’s perception of misconducts by referring to them as social issues. This study represents a step in that direction.

Furthermore, student cheating is often not viewed as a serious enough issue, viewing education as a means to gain some temporary facts, thereby not really hurting anyone, as has been posited in literature (Bishop 1993). So, it is in all stakeholders’ best interests to consider academic misconduct such as contract cheating as a social issue so that the behavior that is often considered as victim-less can be highlighted with clear understanding of the direct, long term and surrounding impacts.

Another valuable lesson learned pertains to student willingness to participate or not participate. For such a small-scale campaign, garnering a steady increase in participation is definitely positive. However, it is important to observe that the systematic increase was still not an overwhelming increase in sample size, given the population of UG students on campus. The phenomenon of students being reluctant to participate in studies related to misconducts is not a new one. Zauzmer (2011) also reported similar frustrations voiced by administrators at a university trying to study student cheating, as reported in Harvard Crimson.

For this study, students who participated the second-year voiced concerns they felt the previous year when they saw the campaign flyers the previous year and were not sure of what it all really meant to participate. However, as students participated, the word of mouth spread regarding the activities and purpose of the campaign. It is believed that the response rate increased in subsequent years to double that of the first year was mainly due to “popularity” of the campaigns, “reach” of the campaign, and “attraction to be photographed” as mentioned by students. Whatever their motivation, it helped spread the reach of the campaign itself, establishing importance of getting the campus to buy into the campaign so that students see the messages from different sources.

Literature has posited that students act as pressure groups for peers (Khan 2014). Literature has also shown that allowing the students to become “co-creators in the learning process, as individuals with ideas and issues that deserve attention and consideration” (McCombs and Whistler 1997) has tremendous impact on student awareness and learning. In this paper, it was highlighted that students joined in the organizing and were able to decide on the type of new events that would be introduced. This worked to increase “active engagement and contribution” (Lee et al. 2006) from the students who organized and students who participated. As seen from the results in the previous section, students joining in fact increased the reach of the project and made those students who graduated advocates of the message of the campaign, thus further increasing effectiveness of the campaign. This is a valuable learning lesson from this study as we shed importance on the stakeholder – peers- to join forces for future campaigns.

Further analyzing the results from year on year, it is very interesting to note that although the mean percentage of student awareness was 70% in year two and 80% in year three, if individual items were analyzed, we can then see the impact of the awareness campaigns. In the second year, though the mean was approximately 70%, the students who said “yes” to “Do you know what contract cheating is?” was already high at about 80% of participants saying they knew. Whereas, percentage of students who said “yes” to knowing that “…using essay writing services from online sources is a form of cheating” was shockingly only 60%! In comparison, during the third year’s campaign the percentage was around 80% for both questions. This could be because the second year was the first time, we had run the campaign after we introduced it the previous year. Participation had increased by only n = 10 more than previous year, and notably in the previous year, none of the participants knew what contract cheating was, or that using essay writing services from online sources was considered cheating. So, it could be that by the second year of the campaign, students had now heard about contract cheating and possibly associated the terminology with buying essays; but the second question did not mention “buying”, it merely said “using”. This is an important lesson for the future iteration of the campaign because contract cheating isn’t just about essay mills writing essays and students paying. Draper and Newton (2017) posit that in fact family and friends could just as easily be rendering writing services either for a fee or other benefits shared.

Overall, it does seem like the campaigns are indeed working as proactive efforts in engaging students to raise their awareness of a social issue, that is, contract cheating. As the campaigns become more wide-spread across the campus, it is hoped that the next years will entice more students to participate and become active campaigners themselves. Primary author aims to continue the campaigns and target a larger sample. Future scope of this project is to conduct subsequent study to see if such campaigns are actually deterring students from engaging in contract cheating.

Conclusion

This paper makes a strong case for first considering academic misconducts such as contract cheating as a social issue and then using campaigns to increase student engagement and awareness of contract cheating. It is crucial to note here that of the respondents that voluntarily participated in the campaigns, their feedback helps shed some light on why the essay mills are able to convince students to use their services: if students are not aware of such an act to be considered as a misconduct (as was the case in the first year where 0% students showed any awareness of the term contract cheating or that using online services to get essays written was even a misconduct), they are open to using such services.

It is also observed and therefore recommended that students be included in organizing and advocating for such campaigns, as students speaking out against contract cheating to other students year on year had a tremendous positive impact on student attitude against contract cheating. This is because students became advocates for integrity, posting messages against essay mills, and confronting the service providers as unethical and irresponsible businesses on open, public platforms and at events where the service providers showed up to promote their questionable services, with messages quoted by participants as “good advice”, “fantastic role model” and “highlighting the services”.

Therefore, this case report suggests that regular, consistent awareness campaigns involving students as co-developers in the integrity-culture building process has a significantly high impact on student contribution, participation, engagement and knowledge, probably becoming the means to stop students from using their services in the future.

The next step of the project is to map how and if this attitude and awareness has any real impact on student behavior and curbing students’ likelihood to contract cheat in the future.

References

Academicintegrity.org (2014). The Fundamental Values. [online] Available at: https://academicintegrity.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Fundamental-Values-2014.pdf. Accessed 23 Mar. 2019.

Anderman, E. M., Friesinger, T., & Westerfield, G. (1998). Motivation and cheating during early adolescence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 84–93 American Psychology Association, Inc.

Awdry, R., & Newton, P. (2019). Staff views on commercial contract cheating in higher education: a survey study in Australia and the UK. Higher Education.

Baggish, R., & Wells, p. (2019, July 20). Academic honesty and the independent school. Retrieved from Independent School Health Check: https://independentschoolhealth.com/research/academic-honesty-independent-school/

Bishop, Michael. “What’s wrong with cheating?” in synthesis: Law and policy in higher education, 1993.

Blachnio, A., & Weremko, M. (2011). Academic cheating is contagious: The influence of the presence of others on honesty. A study report. International Journal of Applied Psychology, 1(1), 14–19.

Bowers, W. J. (1964). Student dishonesty and its control in college. New York: Bureau of Applied Social Research, Columbia University.

Callahan, D. (2004). The cheating culture: Why more Americans are doing wrong to get ahead. Harcourt, Inc.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2004). Substance Abuse Treatment and Family Therapy. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 39.) Chapter 2 Impact of Substance Abuse on Families. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64258/

Champlin, G. (1991). Proactive and reactive strategies. The arc of Berks County newsletter. USA: Wyomissing Behaviour Abalysts, Ltd. Retrieved from http://www.wba2032.com/Topics7.pdf.

Christensen-Hughes, J. M., & McCabe, D. L. (2006). Academic misconduct within higher education in Canada. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 36(2), 1–21.

Clarke, R. and Lancaster, T. (2013), Commercial aspects of contract cheating. In Proceedings of 8th Annual Conference on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education (ITiCSE 2013), Canterbury, UK.

Clarke, R., & Lancaster, T. (2006). Eliminating the successor to plagiarism? Identifying the usage of contract cheating sites. Second Plagiarism: Prevention, Practice and Policy Conference. Newcastle UK.

Crowe, S., Cresswell, K., Robertson, A., Huby, G., Avery, A. and Sheikh, A., 2011. The case study approach. [online] Available at: <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3141799/> [Accessed 20 Mar. 2019].

Cutler, D. (2019, July 20). How to curb student cheating. Retrieved from Medium Education: https://medium.com/@spincutler/how-to-curb-student-cheating-9cf3bf2f436f

Dawson, P., & Sutherland-Smith, W. (2017). Can markers detect contract cheating? Results from a pilot study. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education., 43(2), 286–293.

Dietrich, S., Mergl, R., Freudenberg, P., Althaus, D., & Hegerl, U. (2009). Impact of a campaign on the public's attitudes towards depression. Health Education Research, 25(1), 135–150.

Dolnicar, S., Grün, B., & Leisch, F. (2011). Quick, simple and reliable : Forced binary survey questions. International Journal of Market Research, 53(2), 231–252.

D'souza, K. A., & Siegfeldt, D. V. (2017). A conceptual framework for detecting cheating in online and take-home exams. Journal of Innovative Education.

Foltynek, T., & Kralikova, V. (2018). Analysis of the contract cheating market in Czechia. International Journal for Educational Integrity.

Fox, C. R. (2006). The availability heuristic in the classroom: How soliciting more criticism can boost your course ratings. Judgement and Decision making, 1(1), 86–90.

Fuller, R., & Myers, R. (1941). The natural history of a social problem. American Sociological Review, 320–328.

Grassi, M., Nucera, A., Zanolin, E., Omenaas, E., Anto, J. M., & Leynaert, B. (2007). Performance comparison of Likert and binary formats of SF-36 version 1.6 across ECRHS II adult populations. Value in Health, 10(6), 478–488.

Harp, J., & Taietz, P. (1966). Academic Integrity and Social Structure: a study of cheating among college students. JSTOR, 13(4), 365–373 URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/798585?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

Harrison, H., Birks, M., Franklin, R., & Mills, J. (2017). Case study research: Foundations and methodological orientations. Forum qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 18(1) ISSN 1438-5627.

Heale, R. and Twycross, A., 2017. What is a case study?. Evidence-Based Nursing, [online] 20(1), 7. Available at: doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2017-102845.

Hossain, S. (2018) Shame, guilt, anger—And lives lost. Retrieved from The Daily Star: https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/little-matters/news/shame-guilt-anger-and-lives-lost-1670914

Hudgens, L. H. (2019). Why cheating hurts students now and in the their future. Grown and Flown. URL https://grownandflown.com/cheating-hurts-students-now-and-future/

ICAI. (2019). Statistics. Retrieved from International Centre for Academic Integrity: https://academicintegrity.org/statistics/

Juvonen, J., Graham, S., & Schuster, M. (2006). Bullying among young adolescents: The strong, the weak, and the troubled. Pediatrics, 112(6), 1231–1237.

Khan, Z. R. (2014). Developing a factor-model to understand the impact of factors on higher education students’ likelihood to e-cheat (pp. 1954–2016). Wollongong: UOW Thesis Collection Retrieved from https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4545/.

Khan, Z. R. (2019). What category are they anyway? Proposing a new taxonomy for factors that influence students’ likelihood to e-cheat. In Scholarly ethics and publishing breakthroughs in research and practice. Ch 7. Pp 148–175.

Khan, Z. R. and Balasubramanian, S. (2012). Students go click, flick and cheat… e-cheating, technologies and more. Journal of Academic and Business Ethics. AABRI.

Khan, Z. R., Al Qaimari, G., & Samuel, S. D. (2007). Professionalism and Ethics: Is Education the bridge? In G. L. Turner (Ed.), Information systems and technology Education. Hershey: IMRA International.

Khomami, N (2017). Plan to crack down on websites selling essays to students announced. Higher Education. The Guardian. URL. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/feb/21/plan-to-crack-down-on-websites-selling-essays-to-students-announced

Klepp, K. I., Ndeki, S. S., Leshabari, M. T., Hannan, P. J., & Lyimo, B. A. (1997). AIDS education in Tanzania: Promoting risk reduction among primary school children. American Journal of Public Health, 87(12), 1931–1936.

Lancaster, T., & Clarke, R. (2016). Contract cheating: The outsourcing of assessed student work. In T. Bretag (Ed.), Handbook of Academic Integrity. Netherlands: Springer.

Lane, B. (2017). TEQSA to crack down on outsourcing of assignments. Sydney: The Australian.

Lee, M. J. W., Chan, A., & McLoughlin, C. (2006). Students as producers: Second year students’ experiences as podcasters of content for first year undergraduates. In Proceedings of the 7th Conference on Information Technology Based Higher Education and Training (pp. 832–848). Sydney, NSW: University of Technology.

Lowe, S. M., Okubo, Y., & Reilly, M. F. (2012). A qualitative inquiry into racism, trauma, and coping: Implications for supporting victims of racism. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(3), 190–198.

Marsh, S. (2017). Universities urged to blobk essay-mill sites in plagairism crackdown. The Guardian: Higher Education https://www.theguardian.com/education/2017/oct/09/universities-urged-to-block-essay-mill-sites-in-plagiarism-crackdown.

McCabe, D. L., & Bowers, W. J. (1994). Academic dishonesty among male college students: a thirty year perspective. Journal of College Student Development, 35(1), 3–10.

McCabe, D., & Katz, D. (2009). Curbing cheating. Education Digest: Essential Readings Condensed for Quick Review, 75(1), 16–19.

McCombs, B., & Whistler, J. S. (1997). The Learner-Centered Classroom and School: strategies for increasing student motivation and achievement. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Neil, A. L., & Christensen, H. (2009). Efficacy and effectiveness of school-based prevention and early intervention programs for anxiety. Clinical psychology review, 29(3), 208–215.

Newcomb, M., Maddahian, E., & Bentler, P. (1986). Risk factors for drug use among adolescents: concurrent and longitudinal analyses. American Journal of Public Health, 76(5), 525–531.

Newstead, S. E., Franklyn-Stokes, A., & Arrmnstead, P. (1996). Individual differences in student cheating. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 229–241.

Newton, N. C., Vogl, L. E., Teesson, M., & Andrews, G. (2009). CLIMATE Schools: Alcohol. module: Cross-validation of a school-based prevention programme for alcohol misuse. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(3), 201–207.

Orr Jr., J. (2018). Developing a campus academic integrity education seminar. Journal of Academic Ethics, 16(3), 195–209.

Peters, M. (2019). Academic integrity: An interview with Tracey Bretag. Educational Philosophy and Theory., 51(8), 751–756.

Rigby, D., Burton, M., Balcombe, K., Bateman, I., & Mulatu, A. (2015). Contract cheating and the market in essays. Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organization, 23–37.

Rogerson, A. (2018). Detecting contract cheating in essay and report submissions: process, patterns, clues and conversations. In International Journal for Educational Integrity 13(10). Open: Springer.

Seymour, J. (2017). The impact of public health awareness campaigns on the awareness and quality of palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine. [online] Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5733664/ .

Simkin, M. G., & McLeod, A. (2010). Why do college students cheat? Journal of Business Ethics, 94, 441–453.

Singh, S. and Remenyi, D. (2015). Plagiarism and ghostwriting: The rise in academic misconduct. South African Journal of Science. 112 (5/6) Art. #2015-0300. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2016/20150300

Stewart, S., Loughlin, H., & Rhyno, E. (2001). Internal drinking motives mediate personality domain — drinking relations in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 30(2), 271–286.

Tellis, W. (1997). Introduction to case study. The Qualitative Report, 3(2).

UOW. (2019). What is academic misconduct. Retrieved from UOW: https://www.uow.edu.au/about/governance/academic-integrity/students/misconduct/

Wallace, M. J., & Newton, P. M. (2014). Turnaround time and market capacity in contract cheating. Educ. Stud., 40, 233–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2014.889597.

Wowra, S. A. (2007). Moral identities, social anxiety, and academic dishonesty among American college students. Ethics & Behavior, 303–321.

Yin, R. K. (1984). Case study research: Design and methods. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications.

Yu, H. (2018). Why college students cheat: A conceptual model of five factors. Review of Higher Education, 41(4), 549–576.

Zauzmer, J. M (2011). Low response to cheating survey. Harvard Crimson. URL https://www.thecrimson.com/article/2011/10/20/cheating-survey-low-response/

ZN. (2013). Changing the world with a click? Online activism and social marketing. Sigital Development. ZN Consulting. URL: https://znconsulting.com/articles/changing-the-world-with-a-click-online-activism-social-marketing/

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, Z.R., Hemnani, P., Raheja, S. et al. Raising Awareness on Contract Cheating –Lessons Learned from Running Campus-Wide Campaigns. J Acad Ethics 18, 17–33 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-019-09353-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10805-019-09353-1