Abstract

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder with increasing prevalence, and a male-to-female ratio of 4:1. Research has been suggesting that discrepancy in prevalence may be due to the fact that females camouflage their symptoms. In this study, we aimed to systematically review evidence on the camouflage effect in females with ASD. Following the PRISMA guidelines, we reviewed empirical research published from January 2009 to September 2019 on PubMed, Web of Science, PsychInfo and Scopus databases. Thirteen empirical articles were included in this review. Overall, evidence supports that camouflaging seems to be an adaptive mechanism for females with ASD, despite the negative implications of these behaviours in their daily life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by the presence of core impairments in neurodevelopmental areas as communication and social interaction, restricted, repetitive and inflexible behaviours, interests and activities and sensory-perceptual alterations (American Psychiatric Association [APA] 2013). ASD has an overall prevalence of 16.8 cases per 1000 (Baio et al. 2018). ASD is diagnosed between 3 to 4 times more in males than in females (Baio et al. 2018), depending on the used estimates (e.g., active and passive case ascertainment studies), suggesting a possible diagnostic gender bias, making girls less prone to be misdiagnosed, diagnosed at later ages or even missing out a clinical ASD diagnosis (Loomes et al. 2017).

Sex-differences have been observed in relation to the prevalence of ASD diagnosis in females (Giarelli et al. 2010; Begeer et al. 2013; Rutherford et al. 2016; Rabbitte et al. 2017; Ratto et al. 2018), which may be associated with distinct autistic traits in females, with some studies referring the existence of a specific “female phenotype of autism” (Kopp and Gillberg, 2011; Lai et al. 2015; Bargiela et al. 2016). Some different lines of evidence have been documented that support different clinical presentation of autistic traits in females. According to the Fifth Edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5; APA 2013) females with an ASD diagnosis often exhibit more severe symptoms and more comorbidities (such as intellectual disability [ID] or epilepsy) in comparison to males (Loomes et al. 2017; Ratto et al. 2018). In accordance, when ID is observed in females with ASD, a more balanced gender ratio is observed, suggesting that normal or borderline IQs makes females less prone to be diagnosed with ASD (Loomes et al. 2017).

Lai et al. (2011) suggested that differences between males and females in regards to the ASD diagnosis seem to be mediated by many biological and cognitive causes, such as: (a) cognitive development differences, as females seem to present better visual skills and higher scores in IQ (Lai et al. 2015); (b) the fact that females can be protected by innate mechanisms, for example, sex-steroid hormones (Werling, 2016); (c) differences in empathizing and systemizing, as females seem to be more empathic because of social compensatory skills and/or (d) the camouflaging of ASD core symptoms. In accordance, Lai et al. (2015) suggested a female phenotype of ASD based on the ability to camouflage their autistic symptoms. It is likely that females are more socially competent as they camouflage autistic symptoms, which can lead to a late diagnosis or even to remain undiagnosed.

Camouflaging consists of complex copying behaviours and/or masking some personality traits with an adaptive function that promotes adjustments into specific environmental demands, which is a very common trait in high functioning females with ASD (Lai et al. 2011, 2015; Mandy et al. 2012; Lai and Baron-Cohen 2015; Baldwin and Costley 2016; Bargiela et al. 2016; Tint and Weiss 2018). Camouflaging occurs more commonly in social situations, but it is not restricted to them.

Although the effect of camouflage is understudied, we can find references to this concept in the literature as copying (Lai and Baron-Cohen 2015), masking (Lai et al. 2015; Baldwin and Costley 2016; Bargiela et al. 2016; Mandy 2019) compensation (Mandy et al. 2012) or imitation (Lai and Baron-Cohen 2015). Of note, camouflage differs from imitation processes observed in typically developing children, who use this to learn social skills from the environment and others (Bandura and Walters 1977). Contrarily, children with ASD use social imitation as camouflage to participate in social interactive situations and to be accepted by their peers (Lai and Baron-Cohen 2015).

To the best of our knowledge, Kopp and Gillberg (1992) were the first authors that associated these imitation skills (the basis of camouflaging abilities) with the singularity of a female phenotype of autism (more competent in social contexts), observed in a small sample of females diagnosed with high-functioning ASD. Because of their characteristics, females in this study were late diagnosed (around 6 to over 8 years old), as they did not meet all ASD diagnostic criteria.

A recent review (Lai et al. 2015) summarized the ASD sex-differences in relation to social interaction. The authors reported that females were more socially competent and presented more communicative skills than males, referring that the desire to interact with others could be one possible explanation for the camouflaging behaviour (Lai et al. 2015). Additionally, Lai and Baron-Cohen (2015) suggested that females with ASD learn social and communicative skills through the imitation of their peers, predominantly in social environments. This seems to be further supported by the fact that females with ASD tend to present restricted interests related to social stimuli, in comparison to males with ASD (Lai et al. 2015). For example, they seem to prefer people, animals or music instead of trains or traffic lights.

In addition, females with ASD seem to be more prone to experience increased levels of internalizing symptoms (as loss of self-esteem) and exhibit more emotional disorders or alterations, such as depression or anxiety (Mandy et al. 2012; May et al. 2014). Nevertheless, research regarding a possible ASD female phenotype needs to be further addressed (Bargiela et al. 2016).

Empirical evidence suggest that health professionals may be unfamiliar with ASD symptomology in females, especially those without ID (Ratto et al. 2018; Tint and Weiss 2018). Hence, the lack of specialization related to ASD diagnosis in females (Tint and Weiss 2018; Young et al. 2018) associated with the absence of sex-appropriated diagnostic criteria (Ratto et al. 2018; Young et al. 2018), the impartiality of parents and teachers (Young et al. 2018) and the limitations of diagnostic tools (Lai et al. 2011; Kreiser and White 2014; Ratto et al. 2018; Young et al. 2018) seem to be contributing to the observed absence of an ASD diagnosis in females who camouflage their symptoms. This is also hampered by the fact that some diagnostic instruments are oriented towards a typical ASD symptomatology presentation, reflected on the diagnostic criteria for this disorder: a young boy, male, with severe impairments in several areas of development.

These highly restricted criteria may exclude young females and adults (males and females) with high functioning autism, whose characteristics do not meet the criteria for the ASD diagnosis (Lai and Baron-Cohen 2015; Ratto et al. 2018). However, advances in targeting these difficulties have been observed. For instance, the emergence of clinical settings specialized in females with ASD and the development of specific questionnaires aiming at measuring ASD traits in females, such as the Questionnaire for Autism Spectrum Conditions (Q-ASC), which includes more gender-sensitive criteria (Ormond et al. 2018) and the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) (Hull et al. 2019) that measures camouflage behaviours, have been implemented.

Another important limitation is related to mixed evidence in the study of females’ ASD phenotype (Young et al. 2018). Usually, females enrolled in empirical research have an ASD diagnosis based on the diagnostic criteria derived from males’ ASD phenotype. In this sense, current evidence regarding females’ ASD phenotype may not be representative of possible behavioural and symptomatologic differences from typical ASD (Hiller et al. 2014).

Yet, while it remains an understudied process, camouflaging may have several negative implications for females with an ASD diagnosis (or for those who have not yet been diagnosed), which we aim to describe in this work. Therefore, we systematically reviewed studies focused on the social camouflage effect in females with ASD. To clearly understand the specificities of the ASD diagnosis in females we will discuss the evidence regarding the camouflage effect, its causes and consequences, and how it can inform parents, health professionals and the community about the distinct autistic traits that are present in females with the disorder.

Method

Instrument

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist guidelines (Moher et al. 2015) to perform this systematic review. We selected the following electronic databases for searching: PubMed, Web of Science, PsychInfo and Scopus.

Design

Two filters were selected in all search databases: (1) studies published between January 1st 2009 to September 30th 2019 and (2) English as language of publication. The following search terms/combinations were used: ("autism" OR "asd" OR autis* OR "asperger") AND ("gender" OR "girls" OR "woman" OR "women" OR "female*" OR (sex AND difference*)) AND (camoufla* OR mask* OR copy* OR compensat* OR imitat*).

Studies were screened and discarded based on the following exclusion criteria: (a) not published in scientific journals, (b) different format than empirical paper or short communication (i.e., book chapters, reviews, meta-analysis, congress abstracts, letters to the editor, case reports…), (c) not using human samples, (d) not focused on ASD or Asperger and (e) not focused on the study of camouflaging, masking, compensation, copy or imitation with ASD individuals.

Hence, the following eligibility/selection criteria were applied: (a) studies focusing on camouflaging, masking, compensation, copy or imitation effect of autistic symptoms in females, and (b) studies that included males and/or females with ASD or Asperger’s diagnosis established by the fourth (DSM-IV and DSM-IV-TR) and fifth versions (DSM-5) of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders of the American Psychiatric Association.

Results

A search of the databases resulted in 4536 studies. After the elimination of duplicated results, 3032 studies were selected for title and abstract inspection. After applying exclusion criteria, 47 studies were selected for complete reading. 34 papers were not included because the results did not meet the eligibility criteria, as depicted in the flow diagram (Fig. 1) and Supplementary Table. Thirteen studies were included in this review (Table 1).

Characteristics of the selected studies are reported in Table 1. Sample characteristics were heterogeneous across studies: two included adolescent females with ASD (Tierney et al. 2016; Cook et al. 2018); four included children with ASD with (Head et al. 2014; Dean et al. 2017; Parish-Morris et al. 2017) or without a control group (Rynkiewicz et al. 2016); and seven included adult individuals diagnosed with ASD with (Hull et al. 2019; Lai et al. 2019) or without a control group (Lehnhardt et al. 2016; Hull et al. 2017; Lai et al. 2017; Cage and Troxell-Whitman 2019; Schuck et al. 2019). Three out of the 13 selected studies used a qualitative approach to investigate the camouflaging phenomenon, while the remaining used quantitative analytic methods.

Causes of Camouflaging

Camouflaging is a complex mechanism with possible causes. One of them may be related to social expectations. Indeed, females (with or without ASD) seem to endure more social pressure as they are expected to hide their autistic traits and satisfy the expectations of society based on their gender-role (Head et al. 2014; Cage and Troxell-Whitman 2019; Hull et al. 2019). Camouflaging may, then, arise to face those social expectations and diminished possible feelings of stress or rejection by peers and/or being misunderstood by others (Tierney et al. 2016). Nevertheless, females diagnosed with ASD seem to willingly establish friendships with their peers, despite their limitations in communicating or difficulties in maintaining social relationships (Tierney et al. 2016; Cook et al. 2018).

Females with ASD usually report feelings of loneliness and isolation resulting from bullying or ostracism, among other situations (Cook et al. 2018). In light of this, they seem to develop high-level strategies to fit into social environments, such as imitation of their peers or the masking of their autistic traits (Schuck et al. 2019). Therefore, camouflaging their symptoms, females may more likely resemble to their peers and be able to be involved in social contexts (Head et al. 2014; Hull et al. 2017; Cage and Troxell-Whitman 2019).

How Do They Camouflage Their Symptoms?

Females with ASD seem to display increased self-control skills (Head et al. 2014), possibly as they make efforts that nobody notices their ASD traits (Hull et al. 2017), by, for example, copying famous people or peer’s behaviours (Cook et al. 2018; Dean et al. 2017; Hull et al. 2019). They develop intricate and complex empathy skills (Head et al. 2014; Tierney et al. 2016) and/or feedback abilities (Parish-Morris et al. 2017) to be part of their social environments.

Negative Consequences of Camouflaging

A maintained camouflaging behaviour may imply several long-term implications. An important one may be the late diagnosis (Head et al. 2014; Tierney et al. 2016; Hull et al. 2017, 2019; Lai et al. 2017; Cage and Troxell-Whitman, 2019). Females without an appropriated diagnosis are unable to benefit from proper medical attention that responds to their specific needs.

Camouflaging is also a highly demanding process that can prompt females with ASD to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, depressive symptoms, loss of identity and self-steem, self-injuries and/or suicidal thoughts (Tierney et al. 2016; Cook et al. 2018; Hull et al. 2017,2019; Lai et al. 2017). Because they can also camouflage these emotional symptoms, females often internalize and report less symptomatology than males, although they frequently tend to feel more negative symptoms than males with ASD (Cook et al. 2018; Schuck et al. 2019).

Discussion

In this study, we aimed to systematically review empirical studies that addressed the camouflage effect in females with ASD.

Over the last decade, some attempts to measure the camouflaging effect were achieved, including the development of an index of camouflaging derived from calculating the difference between the standardized scoring of ADOS (Lord et al. 2015) and the standardized scoring of AQ (Baron-Cohen et al. 2006). More recently, we verified an increase in the number of studies addressing the camouflaging effect, including the development of questionnaires focused on the camouflaging effect: the Camouflaging Autistic Traits Questionnaire (CAT-Q) (Hull et al. 2019) and the Q-ASC with gender-sensitive criteria (Ormond et al. 2018).

Literature refer to the camouflage effect as masking, compensation, copying or imitation, although it can be misunderstood as a single process, instead of a set of these subprocesses that encloses this phenomenon (Hull et al. 2017; Lai et al. 2017). For instance, Hull et al. (2017) suggested a camouflage model that is sustained by internal and/or external causes: females diagnosed with ASD tend to mask their symptoms and compensate their social difficulties by imitating peers. In this sense, camouflaging may emerge, according to Cage and Troxell-Whitman (2019), for two main reasons: (a) ‘conventional’ reasons—to fit into formal environments, such as school, work and/or service care and (b) ‘relational’ reasons—to fit into social contexts.

Overall, studies showed that females with ASD appear to be more capable than males to understand the necessity of friendship and intimacy, expressing the necessity of having friends (Tierney et al. 2016), although social environments, friendship and interacting with peers can be challenging for them. In fact, some studies report that females with ASD present difficulties in understanding covert rules of social relationships (friends, partner or family), adhering to rigid gender-social expectations and displaying severe difficulties in socio-communication abilities; these impairments hamper their ability to interpret and experience social life (Tierney et al. 2016; Lai et al. 2017; Schuck et al. 2019). Due to their gender-role expectations, as they camouflage their symptoms, these females are expected to be more social and establish closer relationships with others (Hull et al. 2019; Schuck et al. 2019). This contrasts with a lack of understanding regarding social expectations, which, often, leads to negative consequences such as loneliness and rejection (Tierney et al. 2016; Cook et al. 2018; Dean et al. 2017; Lai et al. 2017; Parish-Morris et al. 2017; Hull et al. 2019; Cage and Troxell-Whitman, 2019; Schuck et al. 2019).

Negative Consequences of Camouflaging

As Hull et al. (2017) suggested on their camouflaging model, a maintained behaviour of camouflaging can present several negative consequences, such as continuous distress and loss of wellbeing and self-esteem (Tierney et al. 2016; Hull et al. 2017), emotional problems (Tierney et al. 2016; Cook et al. 2018; Hull et al. 2017; Lai et al. 2017; Cage and Troxell-Whitman 2019; Schuck et al. 2019) and, importantly, the late ASD diagnosis (Head et al. 2014; Tierney et al. 2016; Cook et al. 2018; Hull et al. 2019).

Long term camouflaging symptoms can have important consequences in self-esteem, as the majority of females with ASD who camouflage their symptoms tend to see themselves as impostors instead of someone who is using adaptive mechanisms to respond to social contexts (Hull et al. 2017). Consequently, camouflaging seems to be more related to high anxiety and depressive symptoms (Tierney et al. 2016; Cook et al. 2018; Hull et al. 2017; Lai et al. 2017; Cage and Troxell-Whitman 2019; Schuck et al. 2019). Although the presence of negative symptoms occurs in both sexes, evidence shows that males with ASD report more often the presence of depressive symptoms, contrasting with females (Lai et al. 2019). This may be due to the fact that, although females with ASD tend to feel more negative emotions than males, they also camouflage their negative mood and, therefore, do not report the presence of depressive symptoms (Schuck et al. 2019). In relation to anxiety, the majority of studies showed a positive correlation between anxiety and camouflaging (Tierney et al. 2016; Cook et al. 2018; Hull et al. 2017; Lai et al. 2017; Cage and Troxell-Whitman 2019), whereas one did not find any relation (Schuck et al. 2019). Overall, camouflage seems to be associated with more negative internal consequences in high camouflagers (individuals who camouflage their symptoms in several situations) and in switchers (individuals with greater camouflaging behaviours in specific situations compared to others), than in low camouflagers (individuals who camouflage their symptoms only in a few situations) (Cage and Troxell-Whitman 2019).

In daily life, females with ASD but without the typical symptoms’ manifestation are confronted with more difficulties, compared to males with ASD (Baldwin and Costley 2016). Distinct studies reported that camouflaging behaviours entail significant problems related to care and health services (Baldwin and Costley 2016; Tint and Weiss 2018), education (Moyse and Porter 2015) or employment (Baldwin and Costley 2016), given that the required attention is not provided because females do not manifest the typical phenotype of ASD.

Phenotype of Females Diagnosed with ASD

Globally, the studies included in this review reported that females with ASD display more camouflaging behaviours than males diagnosed with ASD (Head et al. 2014; Lai et al. 2017, 2019; Hull et al. 2019; Schuck et al. 2019). Similarly, the majority of studies support the necessity of developing sex-sensitive diagnostic criteria for ASD (Head et al. 2014; Tierney et al. 2016; Cook et al. 2018; Dean et al. 2017; Lai et al. 2017; Schuck et al. 2019). It seems that females with ASD are in a disadvantageous position in comparison to males since the criteria for ASD diagnosis is based on a male phenotype. As referred previously, ASD is diagnosed 3 to 4 times more in males than in females (Baio et al. 2018). Females with ASD tend to camouflage their symptoms in social environments, with their parents and with their teachers (Cook et al. 2018), in different ways males do. Adding to the fact that they have more social restricted interests, it is possible that a female phenotype versus the typical male phenotype of ASD exists (Head et al. 2014; Lai et al. 2015).

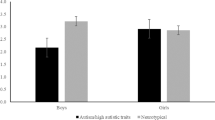

In a study conducted by Dean et al. (2017), the authors investigated how children with ASD, in comparison to typically developing children, spend their time in three playground situations: Game (playing actively with others), Joint Engage (active socialization) and Solitary (when children are alone, not playing or socializing with peers). Results indicated that males (typically developing and ASD) spend more time in the game situation than females (typically developing and ASD). But, between-group comparisons revealed that males with ASD spend more time alone than the other groups, whereas females with ASD spend more time socializing with peers than playing or alone. Overall, it seems that females spend more time in this type of interactions, supporting the hypothesis that they display camouflaging behaviours to engage and resemble to their peers.

Associations Between Camouflage and Cognitive Functions

Females with ASD are also distinctive in other core areas—language or executive functions—and present distinct patterns of brain activation—prefrontal cortex—and brain morphology (Lehnhardt et al. 2016; Rynkiewicz et al. 2016; Lai et al, 2017, 2019; Parish-Morris et al. 2017). Regarding the cognitive phenotype, Lehnhardt et al. (2016) verified that males with ASD scored higher in tasks assessing verbal expression, while females outperformed males in executive tasks that required speed processing, visuo-constructive, verbal fluency and cognitive flexibility abilities. No sex-differences were observed in tasks that did not require time to answer, neither in those involving motor abilities (i.e., WCST). The authors reported that females’ advantage in executive functioning could be related to their camouflaging skills, since they seem to recruit these competencies for copying and imitating their peers.

In addition, females seem to incorporate more non-verbal communication signals, using more vivid and evident gestures, than males (Rynkiewicz et al. 2016). Also, a study ascertaining how individuals with ASD used the interjections ‘UM’ and ‘UH’ to fill empty moments during a conversation, observed that the ‘UM’ interjection, which was more commonly used by females with ASD and younger people, was related to more sophisticated language skills than the interjection ‘UH’ (Parish-Morris et al. 2017). This was interpreted as favorable linguistic camouflage ability used by females with ASD in social contexts.

In a recent neuroimaging study, Lai et al. (2017) investigated the camouflage effect comparing 30 males and 30 females with ASD. Whereas males did not show any significant correlation between camouflaging behaviours and brain activation or morphology, females did. Camouflaging behaviours appeared to be associated with decreased cerebellar, para/hippocampus and amygdala volumes, the later important structures related to memory and emotional processes. In the same line, Lai et al. (2019), comparing 29 males and 28 females with ASD, reported that brain activation patterns differed while performing a task assessing “self-representation responses” and “mentalizing” states. While females with ASD showed an increase in ventral-medial prefrontal cortex (vMPFC) during self-representation, males showed a hypoactivation in vMPFC and in the right temporo-parietal junction during mentalizing state. Also, when comparing brain activation patterns of ASD and typically developing males, an hypoactivation in the vMPFC during self-responses was observed in males with ASD, which was not observed when comparing ASD and typically developing females. This seems to support that camouflage behaviour in females with ASD is prominently based on self-representation responses.

Overall, findings in this systematic review support the existence of a camouflaging effect in females with ASD, focused on the compensation of their symptomatology based on the imitation of peers’ behaviours and masking their own symptoms. Despite the negative consequences of these behaviours, camouflaging seems a highly consolidated process that females with ASD maintain.

Conclusions and Future Implications

Camouflaging is a complex mechanism used to compensate deficits by individuals, particularly females, with ASD. Although camouflaging is an adaptive mechanism, it may enclose several negative implications, such as misdiagnosis, late diagnosis or underdiagnosis that can prevent from adequate or timely intervention.

Because ASD is a spectrum, it would be desirable not only to study the presentation of its associated symptomatology, but also to consider its diversity. Elucidating about a possible female phenotype of autism without comorbidities and understanding the symptomatology associated with it can be important for establishing an early diagnose and, hence, implementing early interventional programs, thereby contributing to better prognostic outcomes. Therefore, seems important to consider the role of camouflage behaviours of females with ASD, its causes, complexity and consequences.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Baio, J., Wiggins, L., Christensen, D. L., Maenner, M. J., Daniels, J., Warren, Z., et al. (2018). Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(6), 1. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6706a1.

Baldwin, S., & Costley, D. (2016). The experiences and needs of female adults with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(4), 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315590805.

Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-hall.

Bargiela, S., Steward, R., & Mandy, W. (2016). The experiences of late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions: An investigation of the female autism phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2872-8.

Baron-Cohen, S., Hoekstra, R. A., Knickmeyer, R., & Wheelwright, S. (2006). The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ)—Adolescent version. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 36(3), 343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0073-6.

Begeer, S., Mandell, D., Wijnker-Holmes, B., Venderbosch, S., Rem, D., Stekelenburg, F., et al. (2013). Sex differences in the timing of identification among children and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(5), 1151–1156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1656-z.

Cage, E., & Troxell-Whitman, Z. (2019). Understanding the reasons, contexts and costs of camouflaging for autistic adults. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(5), 1899–1911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-018-03878-x.

Cook, A., Ogden, J., & Winstone, N. (2018). Friendship motivations, challenges and the role of masking for girls with autism in contrasting school settings. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(3), 302–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2017.1312797.

Dean, M., Harwood, R., & Kasari, C. (2017). The art of camouflage: Gender differences in the social behaviors of girls and boys with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(6), 678–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316671845.

Giarelli, E., Wiggins, L. D., Rice, C. E., Levy, S. E., Kirby, R. S., Pinto-Martin, J., et al. (2010). Sex differences in the evaluation and diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders among children. Disability and Health Journal, 3(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2009.07.001.

Head, A. M., McGillivray, J. A., & Stokes, M. A. (2014). Gender differences in emotionality and sociability in children with autism spectrum disorders. Molecular Autism, 5(1), 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/2040-2392-5-19.

Hiller, R. M., Young, R. L., & Weber, N. (2014). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder based on DSM-5 criteria: Evidence from clinician and teacher reporting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(8), 1381–1393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9881-x.

Hull, L., Lai, M. C., Baron-Cohen, S., Allison, C., Smith, P., Petrides, K. V., et al. (2019). Gender differences in self-reported camouflaging in autistic and non-autistic adults. Autism. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319864804.

Hull, L., Petrides, K. V., Allison, C., Smith, P., Baron-Cohen, S., Lai, M. C., et al. (2017). Putting on my best normal: Social camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2519–2534. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5.

Kopp, S., & Gillberg, C. (1992). Girls with social deficits and learning problems: Autism, atypical Asperger syndrome or a variant of these conditions. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1(2), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02091791.

Kopp, S., & Gillberg, C. (2011). The Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ)–Revised Extended Version (ASSQ-REV): An instrument forbetter capturing the autism phenotype in girls? A preliminary study involving 191 clinical cases and community controls. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 32(6), 2875–2888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.05.017.

Kreiser, N. L., & White, S. W. (2014). ASD in females: Are we overstating the gender difference in diagnosis? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17(1), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-013-0148-9.

Lai, M. C., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Identifying the lost generation of adults with autism spectrum conditions. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(11), 1013–1027. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00277-1.

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., Auyeung, B., Chakrabarti, B., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2015). Sex/gender differences and autism: Setting the scene for future research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.003.

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., Chakrabarti, B., Ruigrok, A. N., Bullmore, E. T., Suckling, J., et al. (2019). Neural self-representation in autistic women and association with ‘compensatory camouflaging’. Autism, 23(5), 1210–1223. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361318807159.

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., Pasco, G., Ruigrok, A. N., Wheelwright, S. J., Sadek, S. A., et al. (2011). A behavioral comparison of male and female adults with high functioning autism spectrum conditions. PLoS ONE, 6(6), e20835. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020835.

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., Ruigrok, A. N., Chakrabarti, B., Auyeung, B., Szatmari, P., et al. (2017). Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in men and women with autism. Autism, 21(6), 690–702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316671012.

Lehnhardt, F. G., Falter, C. M., Gawronski, A., Pfeiffer, K., Tepest, R., Franklin, J., et al. (2016). Sex-related cognitive profile in autism spectrum disorders diagnosed late in life: Implications for the female autistic phenotype. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2558-7.

Loomes, R., Hull, L., & Mandy, W. P. L. (2017). What is the male-to-female ratio in autism spectrum disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(6), 466–474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.013.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P. C., Risi, S., Gotham, K., & Bishop, S. L. (2015). ADOS-2. Manual (Part I): Modules, 1–4. Torrance, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Mandy, W. (2019). Social camouflaging in autism: Is it time to lose the mask? Autism, 23(8), 1879–1881. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361319878559.

Mandy, W., Chilvers, R., Chowdhury, U., Salter, G., Seigal, A., & Skuse, D. (2012). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from a large sample of children and adolescents. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(7), 1304–1313. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1356-0.

May, T., Cornish, K., & Rinehart, N. (2014). Does gender matter? A one year follow-up of autistic, attention and anxiety symptoms in high-functioning children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(5), 1077–1086. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1964-y.

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., et al. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1.

Moyse, R., & Porter, J. (2015). The experience of the hidden curriculum for autistic girls at mainstream primary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 30(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2014.986915.

Ormond, S., Brownlow, C., Garnett, M. S., Rynkiewicz, A., & Attwood, T. (2018). Profiling autism symptomatology: An exploration of the Q-ASC parental report scale in capturing sex differences in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(2), 389–403. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3324-9.

Parish-Morris, J., Liberman, M. Y., Cieri, C., Herrington, J. D., Yerys, B. E., Bateman, L., et al. (2017). Linguistic camouflage in girls with autism spectrum disorder. Molecular Autism, 8(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-017-0164-6.

Rabbitte, K., Prendeville, P., & Kinsella, W. (2017). Parents’ experiences of the diagnostic process for girls with autism spectrum disorder in Ireland: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Educational and Child Psychology, 34(2), 54–66.

Ratto, A. B., Kenworthy, L., Yerys, B. E., Bascom, J., Wieckowski, A. T., White, S. W., et al. (2018). What about the girls? Sex-based differences in autistic traits and adaptive skills. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(5), 1698–1711. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3413-9.

Rutherford, M., McKenzie, K., Johnson, T., Catchpole, C., O’Hare, A., McClure, I., et al. (2016). Gender ratio in a clinical population sample, age of diagnosis and duration of assessment in children and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(5), 628–634. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315617879.

Rynkiewicz, A., Schuller, B., Marchi, E., Piana, S., Camurri, A., Lassalle, A., et al. (2016). An investigation of the ‘female camouflage effect’ in autism using a computerized ADOS-2 and a test of sex/gender differences. Molecular Autism, 7(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13229-016-0073-0.

Schuck, R. K., Flores, R. E., & Fung, L. K. (2019). Brief report: Sex/gender differences in symptomology and camouflaging in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(6), 2597–2604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-03998-y.

Tierney, S., Burns, J., & Kilbey, E. (2016). Looking behind the mask: Social coping strategies of girls on the autistic spectrum. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 23, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.013.

Tint, A., & Weiss, J. A. (2018). A qualitative study of the service experiences of women with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 22(8), 928–937. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361317702561.

Werling, D. M. (2016). The role of sex-differential biology in risk for autism spectrum disorder. Biology of Sex Differences, 7(1), 58.

Young, H., Oreve, M. J., & Speranza, M. (2018). Clinical characteristics and problems diagnosing autism spectrum disorder in girls. Archives de Pédiatrie, 25(6), 399–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcped.2018.06.008.

Acknowledgments

M.T.F. acknowledges Xunta de Galicia-GAIN for the Principia research grant. This work was supported by Fundación María José Jove. S.C. acknowledges Psychology for Positive Development Research Center (Grant No. PSI/04375), Universidade Lusíada – Norte, Porto, supported by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology through national funds (Grant No. UID/PSI/04375/2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MTF and SC were responsible for the article search, data analysis, manuscript preparation, edited and reviewed the manuscript. AS was responsible for the manuscript preparation, edited and reviewed the manuscript. AC was responsible for funding acquisition and edited and reviewed the manuscript. MFP conceptualized the study, edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tubío-Fungueiriño, M., Cruz, S., Sampaio, A. et al. Social Camouflaging in Females with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. J Autism Dev Disord 51, 2190–2199 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04695-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04695-x