Abstract

Children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) face pervasive challenges in symbolic and social play development. The Integrated Play Groups (IPG) model provides intensive guidance for children with ASD to participate with typical peers in mutually engaging experiences in natural settings. This study examined the effects of a 12-week IPG intervention on the symbolic and social play of 48 children with ASD using a repeated measures design. The findings revealed significant gains in symbolic and social play that generalized to unsupported play with unfamiliar peers. Consistent with prior studies, the outcomes provide robust and compelling evidence that further validate the efficacy of the IPG model. Theoretical and practical implications for maximizing children’s developmental potential and social inclusion in play are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pervasive challenges in the development of symbolic play and social engagement with peers are among the most prominent characteristics of children on the autism spectrum. These challenges are intertwined with the core diagnostic features of autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which include a restricted, repetitive and stereotyped repertoire of interests and activities, and challenges in social communication, social emotional reciprocity and peer relationships appropriate to developmental level (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

It is well established that peer play experiences are significant for children’s development, socialization and cultural participation (Brown 2009; Elkind 2007; Fromberg and Bergen 2015). However, developmental and sociocultural factors place children with ASD at risk for being excluded from these essential experiences (Wolfberg et al. 2012). Without explicit guidance, they are in jeopardy of being neglected and rejected by peers and thus deprived of opportunities to actualize their developmental potential. A growing body of research focused on the symbolic and social play of children with ASD underscores the nature and impact of these challenges (for an overview, see Wolfberg 2009).

Developmental Disparities in Symbolic and Social Play

Children across the autism spectrum exhibit unique variations in the development of spontaneous play that manifest within symbolic and social domains (for a comprehensive review, see Wolfberg 2009). In the context of play with peers, typical development progresses in a relatively consistent fashion as children cycle back and forth along a continuum of increasingly complex symbolic and social play behaviors. As opposed to developing as discrete sets of skills in linear, unambiguous stages, symbolic and social play behaviors co-mingle and emerge as a gradual transition, surfacing and peaking at various points across the age span (Howes and Matheson 1992).

Play behaviors within symbolic and social domains are thus conceptualized as hierarchically arranged in terms of level of sophistication, with each successive level expanding while encompassing the preceding level (akin to Russian nesting dolls). The discrepant patterns of peer play exhibited by children with ASD may be understood within the following framework (adapted from Parten 1932; Leslie 1987; McCune-Nicolich 1981; Westby 2000 as cited in Wolfberg and Schuler 2006). Play behaviors emerging within the symbolic domain include (1) not engaged (unoccupied); (2) manipulation and sensory play (exploring physical and sensory properties of objects); (3) functional—a.k.a. relational, reality oriented play (conventional use and association of objects and simple pretense; (4) symbolic-pretend—a.k.a. make-believe, imaginary play (advanced pretense involving representing objects, events, self and others as if something or someone else). Play behaviors emerging within the social domain include: (1) isolate—a.k.a. solitary (no interaction with peers); (2) onlooker-orientation (watching, following peers from a distance); (3) parallel-proximity (playing beside peers); (4) common focus (reciprocal interaction with peers); (5) common goal—a.k.a. cooperative play (collaborating with peers in a coordinated fashion).

Within the symbolic domain, the spontaneous play of children with ASD is characterized as less varied, flexible and creative as compared to the diverse, complex and imaginative qualities that epitomize typical play development (Hobson et al. 2009, 2013; Jarrold and Conn 2011). In unsupported play situations, children with ASD display higher rates of manipulation or sensory play with objects than either symbolic-pretend or functional play (Dominguez et al. 2006; Libby et al. 1998; Manning and Wainwright 2010; Williams 2003). They especially gravitate to materials that provide intense and explicit sensory feedback, repetitive motions and cause and effect actions (Doody and Mertz 2013). Studies comparing children with ASD to developmentally matched peers indicate delayed onset and atypical patterns of representational play that point to a specific impairment in spontaneous symbolic-pretend that likely extends to functional play (Baron-Cohen 1987; Jarrold 2003; Lewis and Boucher 1988; Williams et al. 2001). The transition from functional (including simple pretense) to symbolic-pretend (advanced pretense) is particularly difficult for children with ASD. Their functional play is less diverse, elaborate and integrated as compared to developmentally matched peers (Williams et al. 2001). In free play situations, they produce symbolic-pretend play that contains less novelty (Charman and Baron-Cohen 1997; Jarrold et al. 1996) and fewer advanced forms, including object-substitutions, treating a doll as an active agent, and inventing imaginary entities (Baron-Cohen 1987; Lewis and Boucher 1988; Ungerer and Sigman 1981).

Within the social domain, children with ASD similarly show discrepancies in their development of spontaneous play with peers (Carter et al. 2005; Dissanayake et al. 1996; Jordan 2003; Sigman and Ruskin 1999). They exhibit unique patterns of social play that are consistent with the social profiles delineated by Wing and Gould (1979) in their seminal work including: aloof—i.e., withdraw or remain at a distance from peers; passive—i.e., watch or follow along with peers, but with little self-initiation; active-odd—i.e., actively approach and initiate with peers, but in an idiosyncratic manner. Studies conducted in free play settings indicate that children with ASD make fewer overt social bids to peers (Corbett et al. 2010; Hauck et al. 1995; Sigman and Ruskin 1999) as well as respond inconsistently when peers initiate with them (Attwood et al. 1988; Corbett et al. 2010; Volkmar 1987). These problems closely interface with children with ASD’s persistent difficulties in social communication, the primary conduit for establishing social reciprocity in play (Dissanayake et al. 1996; Sigman et al. 2006).

It is important to recognize that children with ASD are not altogether devoid of the innate desire or capacity to play and socialize with peers (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Calder et al. 2013; Chamberlain et al. 2007; Hobson et al. 2009, 2013; Jarrold 2003; Kasari et al. 2012). However, they do exhibit differences from typically developing children in that they express their interests and display their abilities in subtle and unexpected ways. Many children with ASD are able to comprehend as well as generate novel pretend play acts when elicited or modeled, but this potential often remains untapped since they are less likely to seek out imaginary play on their own (Charman and Baron-Cohen 1997; Hobson et al. 2009, 2013; Jarrold et al. 1996; Lewis and Boucher 1988). Moreover, children across the spectrum are known to make frequent attempts to initiate play with peers, but due to their unconventional nature these initiations often go unnoticed to merit a response or to be counted as an attempt to socialize (Kasari et al. 2012; Boucher and Wolfberg 2003; Jordan 2003).

Sociocultural Influences on Symbolic and Social Play

Sociocultural factors inexorably influence experiences that impact children’s competence in symbolic and social play. In particular, the peer group or “peer culture” has a prominent role in supporting or hindering opportunities for children with ASD to play and socialize with other children (Kasari et al. 2012; Ochs et al. 2004; Wolfberg et al. 1999, 2012). Peer culture consists of shared understandings, values and beliefs, and associated activity and relationship patterns that children construct out of everyday experiences with one another (Wolfberg et al. 1999). Thus, it is the peer culture that sets the standard for what is or is not acceptable for a child to be included in the “play culture”—i.e., the social and imaginary worlds children create together. Given their disparities, children with ASD are highly vulnerable to be being ignored, rejected and judged as social outcasts by peers who lack a framework for understanding autism and appreciating their individual differences.

Although adults are not a part of the collective identity of the peer or play culture, their values and beliefs are inevitably passed down and imbued in children’s play experiences (see for example, Ochs et al. 2004; Wolfberg et al. 1999). Common misconceptions about children with ASD may engender responses from peers that further set them apart from their peer group. For instance, a common erroneous belief is that children with ASD make a conscious choice to isolate themselves because they lack an innate interest and capacity to play and socialize with other children (Bauminger and Kasari 2000; Calder et al. 2013; Chamberlain et al. 2007). Such views convey the idea that these children are too different from other children to join peer activities, and should be left alone to their own devices during periods of play.

In light of these transactional influences, exclusion from the peer culture exacerbates social difficulties by depriving children with ASD the very play experiences that serve to mediate development, socialization and sociocultural participation. To break this cycle, there is a need to maximize the intrinsic motivation and developmental potential of children with ASD by supporting their inclusion in the culture of play with typical peers. Moreover, there is also a need to maximize the extent to which typically developing children make efforts to include children with ASD in their play.

Integrated Play Groups Model

This study focuses on Integrated Play Groups (IPG), a comprehensive intervention designed to address the unique challenges children with ASD experience in symbolic play and social engagement with peers (for detailed descriptions, see Wolfberg 2003, 2009; Wolfberg et al. 2012). The primary objectives for the children with ASD are to promote social communication, reciprocity and relationships with peers, while also expanding their play repertoire to include symbolic play. Another equally important aim is for peers to gain knowledge, empathy and skills to be accepting and responsive to the unique differences of their playmates with ASD. The major intention is for the children to spontaneously play, socialize and form friendships while coordinating their own culturally valued experiences with minimal adult involvement.

The IPG model differs from other peer mediated and play therapy interventions in that its principles and practices are grounded in sociocultural theory (for reviews of related evidence based practices, see National Autism Center 2009; Wong et al. 2013; Reichow and Volkmar 2010). It specifically draws from the social constructivist work of Vygotsky (1967, 1978) who ascribed prime importance to the role of play as both mirroring and leading development. Imaginary play is viewed as a primary collective social activity through which children learn and develop capacities to symbolize, socialize and culturally construct meaning. Learning and development take place during social interactions within the child’s “zone of proximal development” (ZPD) or “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving, and the level of potential development as determined through problem solving under guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers” (Vygotsky 1978, p. 86).

Consistent with Vygotsky’s theory, the IPG intervention embraces Rogoff’s (1990) notion of guided participation whereby children’s learning and development are mediated through active engagement in culturally relevant activity (namely play) with the assistance and challenge of responsive social partners (adults and peers) who vary in skill and status. Thus, there are gains to be made by both the novice players (children with ASD) and expert players (typically developing peers) as they learn from one another in a reciprocal fashion. Novice players come to develop more sophisticated social interactive and play behaviors while expert players learn to adapt their social interactive behaviors to those with more limited social communicative and play repertoires.

The IPG intervention is designed to function as a part of a child’s individualized education/therapy program. Each IPG is composed of three to five players with a higher ratio of expert to novice players and an adult facilitator (IPG guide). The group meets regularly in a selected site that offers a consistent space and selection of motivating play materials and activities that are highly conducive to fostering joint attention, imitation, social reciprocity and imaginary play. IPG sessions provide a structured framework that offers a high level of predictability (using consistent schedules, routines and visual supports), and encourages flexibility through guided participation in co-constructed play activities that consider the unique interests, abilities and needs of each player and the group as a whole.

Based on sensitive assessments, the IPG guide applies the core practices of guided participation, as follows:

-

Nurturing play initiations involves recognizing, interpreting and responding to the subtle and idiosyncratic ways in which novice players express their interests and intentions to play in the company of peers.

-

Scaffolding play involves systematically adjusting the amount and type of support based on the degree to which novice and expert players are able to coordinate their own play interactions.

-

Guiding social communication supports novice and expert players in using verbal and nonverbal social-communication cues to elicit another’s attention, initiate and respond to each other’s initiations, and sustain reciprocal engagement in play.

-

Guiding play within the “ZPD” encompasses a continuum of strategies that support novice players in peer play experiences that are slightly beyond the child’s capacity while fully immersed in the whole play experience at his or her present level, even if participation is minimal.

To date, a series of experimental (single-case design) and qualitative (ethnographic, interview, observation) studies have been conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the IPG model for children across the autism spectrum of diverse ages, abilities and cultural and linguistic backgrounds, as well as to explore the nature of the interaction that occur within play sessions (Lantz et al. 2004; Richard and Goupil 2005; Yang et al. 2003; Wolfberg and Schuler 1992, 1993; Wolfberg 1994, 2009; Zercher et al. 2001). Overall, the accumulated findings indicate that the children with ASD showed advances in the quantity and quality of symbolic and social forms of play after participation in the IPG intervention. Those studies that employed single-case methodologies showed consistent increases in complexity of play (functional and symbolic-pretend), increases in interactive and reciprocal play with peers (parallel-proximity, common focus) and decreases in stereotyped (manipulation-sensory) and isolated play. There was also evidence that the gains observed during the intervention were maintained when adult support was withdrawn (Lantz et al. 2004; Richard and Goupil 2005; Wolfberg and Schuler 1993; Yang et al. 2003; Zercher et al. 2001). In addition, social validation data indicated that the gains made in the intervention were perceived as important and relevant to stakeholders, including parents and practitioners (Lantz et al. 2004; O’Connor 1999; Wolfberg 1994; Wolfberg and Schuler 1992, 1993; Yang et al. 2003; Zercher et al. 2001).

Although the above-mentioned studies have offered promising evidence that supports the efficacy of the IPG model and its recognition as an evidence-based practice (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association 2006; DiSalvo and Oswald 2002; Iovannone et al. 2003; National Autism Center 2009; Wong et al. 2013), there are limitations both in terms of the methodologies and sample sizes. While most of the studies applied formalized controls using single-subject methodologies, by design these included a small number of participants (between one and four). The small sample size limits the generalizability of the reported findings. These studies do not provide the direct evidence afforded by empirical studies involving controlled large group experimental treatment designs. Moreover, the outcomes of these studies raise additional questions regarding the nature of change specifically with respect to the potential relationship between symbolic play and social play development within the context of the IPG intervention.

Research Questions

This current investigation was conducted as a part of a larger research project to further evaluate the efficacy of the therapeutic benefit of the IPG model in children with ASD by instituting a more tightly controlled, quantitative analysis with a larger sample size than previous studies. Specifically, the study employed a within-subjects repeated measures research design to examine the effects of a 12-week IPG intervention (conducted in after-school programs within two public elementary schools) on the symbolic and social play development of children with ASD. We hypothesized that the children with ASD who participated in the IPG intervention would (1) show more advanced symbolic and social play over the course of treatment (the IPG intervention), (2) and compared to a baseline period prior to treatment, and (3) maintain and generalize developmental gains in symbolic and social play observed in the IPG intervention to a non-intervention condition (unsupported play with unfamiliar peers).

Methods

Participants

Primary participants included 48 children with ASD (age 5–10 years) who participated in the IPG intervention. The children with ASD were recruited from local schools, clinics and community agencies within an urban area of Northern California where the study was conducted. Consistent with the demographics of the surrounding community, the children represented diverse ethnic, cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds.

To determine eligibility, parents were initially interviewed and completed questionnaires regarding each child’s developmental history, co-morbid diagnoses, and provided a list of current and past behavioral and medical interventions. The Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic—ADOS-G (Lord et al. 1999) was administered by two graduate research assistants (with prior training and experience in the use of this instrument) to 47 of our 48 participants to confirm and differentiate the diagnosis of autism or ASD (i.e., based on DSM-IV criteria; American Psychiatric Association 2000) An exception was made to obtain a copy of the ADOS that had been administered to one participant shortly before the start of the study.

The children were included in the study based on the following conditions: (1) confirmed diagnoses of autism or ASD as reported by parents and corroborated by administration of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic (ADOS-G) (Lord et al. 1999), (2) informed consent was obtained from their parent/guardian to participate in the study, and (3) child does not engage in potentially harmful behaviors that may pose risks to self or others (e.g., self-injury, physically aggressive behaviors). During the study, participants were asked not to participate in another peer play intervention program; however, treatment as usual continued for ethical reasons. Table 1 provides an overview of demographic information by diagnosis for the 48 children with ASD who met the inclusion criteria and participated in the study.

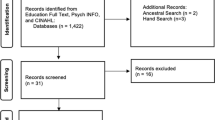

Figure 1 shows the flow of primary participants in the study. A total of 54 children with ASD were initially screened for inclusion in the study. Of these children, one withdrew prior to administration of the ADOS and five did not meet inclusion criteria and were excluded from the study. Therefore, a total of 48 children with ASD completed the study. The study was conducted over a 2 year period involving four waves of observations that included baseline, pre-treatment (i.e., a second baseline measure), intervention and post-treatment. Each observation period was separated by 3-months to correspond to the length of the IPG intervention and enable to test for the effects of maturation. The large majority of participants completed all four waves of observations with the exception of 16 children.Footnote 1 In addition, two participants were unable to complete the post-treatment observation due to an inability to schedule within the alotted time-frame. The available data for these participants were included in the overall analysis.

Secondary participants included 144 typically developing peers (ages 5–10 years), 54 who participated in the IPG intervention and 90 who were unfamiliar to the children with ASD and participated in baseline, pre-treatment and post-treatment observations. The typical peers were included in the study based on the following conditions: (1) child does not have an identifiable disability that would qualify for special education services, (2) informed consent was obtained from their parent/guardian to participate in the study, and (3) child expressed a willingness to participate in the study verbally and/or through written assent for children ages 9–10 years. The typical peers were recruited from their respective school site and similarly represented diverse ethnic, cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds consistent with the demographics of the surrounding community.

Implementation of the IPG Intervention

The IPG intervention was conducted for 12 weeks in after-school programs within two public elementary schools. A total of 24 groups (each comprising two children with ASD and three typical peers) met twice weekly (Monday–Wednesday or Tuesday–Thursday) for 60-min sessions. IPG sessions took place in designated playrooms each of which was consistent in size (approximately 12 × 18 feet), layout, organization and selection of high interest sensory, constructive and socio-dramatic play materials.

Each group was facilitated by a lead IPG guide and an assistant. Across groups, IPG sessions adhered to schedules that included an opening ritual (i.e., greeting, review schedule, prepare for play) and closing ritual (i.e., clean up, debrief, farewell) and a minimum of 40 min of guided participation in play. An orientation, autism demystification and group identity activity were also conducted in initial IPG sessions across groups (Wolfberg et al. 2014).

Fidelity of the Intervention

Several strategies were used to insure the IPG intervention was delivered as intended and that all participants received the essential elements of the intervention. These strategies included (1) the use of a detailed IPG Field Manual comprising a cohesive, competency-based curriculum focused on the principles, tools and techniques for applying the intervention model (Wolfberg 2003), (2) providing extensive training and supervision by the lead investigator to a total of 16 IPG guides (who earned or were working toward a graduate degree in a relevant field and had experience with children with ASD) who demonstrated meeting the competencies of the IPG model curriculum; and (3) monitoring the ongoing IPG sessions using a measure of fidelity comprising a dichotomous scale (pass/no pass) on five indices of competence corresponding to the key intervention practices detailed in the IPG Field Manual: (a) Play session structure; (b) Nurturing play initiations; (c) Scaffolding play; (d) Guiding social communication; and (e) Guiding play within the “ZPD”.

For each of the 16 IPG guides, three video recordings (equivalent to 20 %) of IPG sessions were randomly selected, one within the initial 2 weeks, one within the middle 2 weeks and one within the final 2 weeks of the 12-week IPG program. Two observers with expert knowledge of the IPG model independently rated each IPG guide on three videos. To establish inter-rater reliability, an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) two-way mixed effects model was used to calculate average ratings based on absolute agreement between observers with a 95 % confidence interval (McGraw and Wong 1996). This resulted in an overall rating of .96 (.89–.99). The criteria for IPG guides was to meet 80 % of the competencies or higher within and across the three observations. The mean rating for meeting the competencies was 94 % with a range from 80 to 100 % within and across individual observations.

Measures

The measures used in this study are developmentally-based deriving from our original research (Wolfberg and Schuler 1993). For this study, a continuous sequential coding system (Bakeman 2000) was used to systematically measure the occurence of symbolic and social play behaviors observed in the children with ASD at different time points (baseline, pre-treatment, intervention, post-treatment) within the IPG intervention and a non-intervention condition (unsupported play with unfamiliar peers) (see “Data Collection”). Of interest to this study was the frequency of symbolic and social play behaviors (i.e., states) within streams of coded play episodes. This comprised coding within these streams two sets of mutually exclusive and exhaustive behaviors corresponding to earlier described play behaviors within the symbolic and social domain, respectively. The symbolic domain consisted of four play behaviors: (1) not engaged, (2) manipulation-sensory, (3) functional, and (4) symbolic-pretend play. The social domain consisted of five play behaviors: (1) isolate, (2) onlooker-orientation, (3) parallel-proximity, (4) common focus, and (5) common goal. Table 2 provides definitions and examples of the play behaviors within each respective domain.

Given the mutually exclusive nature of the specific play behaviors within the symbolic and social play domains, the play behaviors were conceptualized as comprising a type of ordinal scale of play behavior from least developmentally complex or sophisticated (e.g., ‘not engaged’, or ‘isolate’) to most developmentally sophisticated (e.g., ‘symbolic-pretend’ or ‘common goal’). This conceptualization led to a weighting scheme of play behaviors within each domain (i.e., 1–4 in symbolic domain and 1–5 in symbolic domain). As such, two summary domain scores were created that reflected each child’s most frequent play behavior type in terms of this ordinal scale at each time-point. As an example, for play behaviors in the symbolic domain the percent of frequency of isolate codes were weighted by a factor of 1, onlooker-orientation codes by a factor of 2, parallel-proximity by a factor of 3, common focus by a factor of 4, and common goal by a factor of 5. These weighted frequency percentages were then summed and, given that these were percentages, were divided by 100 to yield an average scale score from 1 to 5 representing the child’s average position on the ordinal scale of competence for the given construct. A child with a summary score of, say, four would be a child who tended to exhibit relatively sophisticated social engagement during play (i.e., the equivalent of common focus). The same procedure was used to calculate a similar summary score for play behaviors within the symbolic domain for each child. These summary scores were calculated for each child at each time-point corresponding to data collected within the intervention and non-intervention observation conditions.

Data Collection

IPG Intervention Observations

Video recordings of IPG intervention sessions were collected during the initial two and final 2 weeks of the 12-week intervention period. A random selection of 5-min segments of usable data (i.e., child was in full view of camera; adult was not engaging with or prompting the child; adult was not prompting peers to engage with the child) within the 40 min period of guided play were used to code the symbolic and social play of each child with ASD.

Unfamiliar Peer Play Observations (Baseline, Pre-treatment, Post-treatment)

Each child with ASD participated in a series of 15-min sessions of unsupported play with two unfamiliar peers at three different time-points: baseline (3 months before IPG intervention), pre-treatment (1 week before IPG intervention) and post-treatment (1 week following IPG intervention). Within each session, a trained graduate research assistant presented to the children three sets of play materials for 5 min of free play each: (1) motor play with a beach ball, playground ball, or yoga ball, (2) constructive play with wooden blocks, foam building-blocks or Legos, and (3) thematic play with doctor kit or hairdresser kit. Upon presenting the materials the researcher states: “What can you do with this” and moves out of the play space. All sessions were video recorded. The set-up for the unfamiliar play observation was adapted from the Lowe and Costello Symbolic Play Test (Lowe and Costello 1976) by combining the presentation of the symbolic component of spontaneous object play with a social component of spontaneous social play with peers.

Data Coding

Using the Noldus/Observer XT10 computer software, the coders were presented 300 s video clips for each respective child and asked to identify dominant play behaviors as they occur in a play episode using the definitions provided in Table 2. A play episode was defined as having a beginning and end point demarcated each time a new play behavior occurs. While observing a play episode, the coder records the dominant play behavior exhibited by the child within the respective domain. Each time a dominant play behavior change was observed in symbolic, social or both domains, the occurring play behavior was recorded as a new play behavior marking the end of the previous play episode and the beginning of a new play episode. A play behavior was only coded if the play episode was observed for 3 or more seconds. Consider the example of a child observed to wander and gaze randomly at the environment for 3 or more seconds, look at a peer for 2 s, and return to gazing at the environment for 3 or more seconds. This would represent a single play episode and be coded as one play behavior. In this case, “isolate” is the dominant play behavior within the social domain (as opposed to three separate play behaviors coded as “isolate”, “onlooker”, “isolate”). As another example, a child is observed to brush a doll’s hair beside a peer, give the brush to the peer, watch the peer brush the doll’s hair, and then take the brush from the peer and brush the doll’s hair again. This would be coded as one play episode with “common focus” the dominant play behavior within the social domain and “functional” the dominant play behavior in the symbolic domain. If the child continues brushing the doll’s hair while the peer plays peek-a-boo with a different doll beside her, this would represent a shift to a new play episode in which “parallel” and “functional” are coded as dominant behaviors, respectively.

All video recorded observations were independently coded by a total of eight trained undergraduate and graduate students who were naïve to the study’s specific hypotheses and the time-points of the data observed. The coders were trained by the lead investigator in collaboration with four research assistants to reach a criterion level of 80 % agreement for individual codes (symbolic and social) based on four selected pre-coded video-recorded observations of children with ASD participating in IPG and unfamiliar peer play observations.

Inter-rater Reliability

To establish inter-rater reliability, 20 % of video-recordings of each observation condition were coded by two trained independent observers. ICCs conducted for symbolic and social domains and individual play behaviors within respective domains resulted in high ratings, as follow: symbolic domain .97 (.94–.97); social domain .96 (.95–.97); not engaged 1.0 (.99–1.0); manipulation-sensory .88 (.78–.93); functional .99 (.98–1.0); symbolic-pretend 1.0 (.98–1.0); isolate .97 (.95–.99); onlooker-orientation, .95 (.89–.98); parallel-proximity .99 (.98–.1.0); common focus .98 (.96–.99); common goal .82 (.79–.96).

Data Analysis

The analysis plan involved generalized linear models wherein time-point was treated as a repeated factor (baseline, pre-treatment, and post-treatment). Diagnosis (autism vs. ASD), gender, and age at treatment initiation were also all considered as predictor variables. For all models, gender and age at treatment were non-significant and were therefore dropped from the models presented below. In order to test for significant differences in play behavior change between the baseline phase and the treatment phase, a quadratic effect for time-point was included in the models. Planned comparisons for time-point effects involved a) baseline to pre-treatment as a test of the non-intervention condition, and b) pre-treatment to post-treatment as a test of the intervention condition. Analyses of domain scores (symbolic domain or social domain) were conducted separately, and, when significant, follow-up analyses of frequency percentages of each individual play behavior within the respective overall domain score (e.g., functional play) were conducted in order to elucidate which, if any, play behaviors accounted for change within an overall domain score.

The first set of analyses involved play observations within the IPG intervention during a session within the initial and final weeks; these analyses provided a test of play behaviors within the context of treatment itself. The second set of analyses involved play observations with unfamiliar peers at baseline, pre-treatment, and post-treatment and provided a more direct test of treatment effects as they generalized to a different social context with new peers. Finally, as an ad hoc analysis, we examined the relationship between both domain scores during unfamiliar peer play observations at pre-treatment and post-treatment and whether change in one domain score mediated change in the other domain score using tests of mediation as discussed in MacKinnon and Dwyer (1993) and Sobel (1982). All analyses were conducted in SPSS, version 21.

Results

IPG Intervention Play Observation

Analyses of both the symbolic and the social play domain scores, as measured with peers during the IPG intervention sessions, revealed significant main effects for time-point for both domain scores. Specifically, for the symbolic domain, there was a significant increase between the initial observation and the final observation (t = 6.59, p < .001, d = 0.96), with significant decreases in not engaged and manipulation-sensory play behaviors, and significant increases in functional and symbolic-pretend play behaviors. For the social domain, there was a similar significant increase between the initial and final observations (t = 11.41, p < .001, d = 1.66), with significant decreases in isolate and onlooker-orientation play behaviors, and significant increases in parallel-proximity and common focus play behaviors.

Unfamiliar Peer Play Observations

Symbolic Play Domain

Analysis of the symbolic domain score measured during the baseline, pre-treatment and post-treatment unfamiliar peer play observations revealed a significant main effect for time-point (F(1, 37.96) = 14.99, p < .001) and a main effect for diagnosis (F(1, 45.16) = 4.76, p < .05). There was no significant interaction effect between time-point and diagnosis. The quadratic effect for time-point was also significant (F(1, 39.12) = 9.66, p < .01), indicating significantly greater change during the treatment phase versus the baseline phase. Examination of the simple comparisons for time-point revealed no change in symbolic domain scores between baseline and pre-treatment (t = 0.15, p = .88), but did show a significant increase in symbolic domain scores from pre-treatment to post-treatment (t = 5.18, p < .001, d = 0.77). Figure 2 depicts mean symbolic play domain scores across time-points. For the main effect of diagnosis, children with autism had lower overall symbolic domain scores than children with ASD, regardless of time-point (t = 2.18, p < .05, d = 0.33).

Analysis of frequency percentages of each play behavior within the symbolic domain revealed significant main effects for time-point and diagnosis for percentage of not engaged and symbolic-pretend plays behaviors, but not for manipulation-sensory or functional play behaviors. Specifically, there were significant decreases in not-engaged play behavior between pre-treatment and post-treatment (t = 2.98, p < .05, d = 0.45) and significant increases in symbolic-pretend play behavior between pre-treatment and post-treatment (t = 3.11, p < .05, d = 0.49). For diagnosis, children with autism exhibited significantly greater amounts of not-engaged play behavior overall when compared to children with ASD (t = 2.45, p < .05, d = 0.36), and significantly lesser amounts of symbolic-pretend play behavior (t = 2.21, p < .05, d = 0.33). Table 3 provides estimated marginal means for symbolic and social play domain and corresponding play behavior scores for children with ASD and autism diagnoses.

Social Play Domain

Consistent with the findings above for the symbolic play domain, a mixed model analysis of the social play domain score revealed significant main effects for time-point (F(1,39.28) = 7.66, p < .01) and for diagnosis (F(1,44.27) = 4.98, p < .05). There was no significant interaction effect between time-point and diagnosis. The quadratic effect for time-point was also significant (F(1, 40.86) = 4.43, p < .05), again indicating significantly greater change during the treatment phase versus the baseline phase. Examination of simple comparisons for time-point revealed no change between the baseline and pre-treatment time-points (t = 0.22, p = .83), but did show a significant increase in social play domain scores from pre-treatment to post-treatment (t = 3.54, p < .01, d = 0.52). For the main effect of diagnosis, children with autism had lower overall social play domain scores than children with ASD, regardless of time-point (t = 2.23, p < .05, d = 0.34). Figure 3 depicts mean social play domain scores across time-points.

Analysis of frequency percentages of each play behavior within the social domain revealed a significant time-point effect only for isolate play behavior (F(2,39.77) = 4.22, p < .05), with no change between baseline and pre-treatment (t = 0.62, p = .54), but a significant decrease in isolate play behavior from pre-treatment to post-treatment (t = 2.15, p < .05, d = 0.32). There were no significant time-point effects for any of the other social domain play behaviors. There were significant diagnosis main effects for isolate and onlooker-orientation play behaviors, with children with autism exhibiting significantly more of such play behaviors at all time-points compared to children with ASD (t = 2.72, p < .05, d = 0.43; t = 2.14, p < .05, d = 0.36 respectively). In contrast, children with ASD exhibited significantly more common focus play behavior than children with autism at all time-points (t = 2.55, p < .05, d = 0.37) (see Table 3).

Relationship Between Social Play and Symbolic Play Domains

The zero-order correlation between the social play domain score and the symbolic play domain score across time-points was moderately high (r = .71), suggesting the domain scores were moderately related to each other. In order to examine whether change in one domain (e.g., social play domain) mediated change in the other domain (e.g., symbolic play domain), we examined changes in the coefficient for time-point in models with and without the other domain score as a predictor. Evidence was found for a mediational effect for the symbolic play domain on the social play domain. Specifically, when change in the symbolic play domain was entered into the basic model predicting change in the social play domain between pre-treatment and post-treatment, the main effect for time-point was no longer significant (p = .35), and this reduction in the time-point effect, calculated as the mediational effect (MacKinnon and Dwyer 1993; Sobel 1982), was highly significant (z = −5.05, p < .001). In contrast, examination of change in play behaviors within the social play domain as a mediator of change in play behaviors within the symbolic play domain, the effect for time-point remained significant (p < .05), with half as much of a reduction in the time-point coefficient.

Discussion

Building on two decades of research and practice, the positive outcomes of this investigation provide robust and compelling evidence for validating the efficacy of the therapeutic benefit of the IPG model for children with ASD. This study was conducted as a part of a larger research project with the aim to institute a more tightly controlled and rigorous quantitative study with a larger number of participants as compared to our previous studies. Observations of the children participating in the IPG intervention and unsupported play with unfamiliar peers contexts yielded outcomes that supported our hypotheses. The findings demonstrated that after participating in a 3-month IPG intervention, the children with ASD showed significant gains in both symbolic play and social play as compared to a 3-month baseline phase prior to the intervention. Specifically, the respective analyses revealed increases in functional and symbolic-pretend play behaviors that were accompanied by decreases in not engaged and manipulation-sensory play behaviors. A similar pattern occurred in the social domain with increases in parallel-proximity and common focus and collateral decreases in isolate and onlooker-orientation play behaviors. These changes were not observed in these same children, over an equivalent time period, before participation in the IPG intervention (i.e., during the baseline period in which they served as their own controls). The developmental gains observed in the IPG intervention were also maintained and generalized to the non-intervention context involving unsupported play with unfamiliar peers.

Importantly, within the symbolic play domain, the decrease in not-engaged play behavior and the increase in symbolic-pretend play behavior were both significant. This would suggest that the IPG intervention did not simply reduce non-engaged play behavior with a general overall increase in all active play behaviors, but that it specifically increased a specific type of play behavior (namely symbolic-pretend play). In contrast, within the social play domain, the significant decrease in isolate play behavior was not offset by specific significant increases in other play behaviors; instead, there were general non-significant increases in a number of social play behaviors, suggesting a less specific effect on social play behaviors.

Although not a specific focus at the onset of our current study, the findings also revealed significant differences related to severity of the diagnosis and play behaviors within the IPG intervention context. The children diagnosed with autism exhibited less advanced play behavior in the symbolic domain (lower rates of symbolic-pretend) and social domain (higher rates of isolate) as compared to the children diagnosed with ASD. There was a similar trend in the non-intervention context, however, significant differences were not observed. These findings correspond to studies showing a similar relation between symbolic play and cognitive abilities (Baron-Cohen 1987; Leslie 1987), as well as social abilities in children with ASD (Hobson et al. 2013; Stanley and Konstantareas 2006).

In addition, an exploratory ad hoc analysis revealed evidence that suggests the changes observed in the children’s social play were mediated by changes in their symbolic play. This finding may have parallels with Stahmer’s (1995) study that showed spillover effects in which symbolic play training not only resulted in improved symbolic play, but also improved social interaction skills in children with ASD.

One interpretation of these findings is that the IPG intervention afforded opportunities for children with ASD to practice and refine their ability to attribute symbolic meaning to objects, roles and events in play, which in turn supported their social understanding and ability to engage in increasingly coordinated and socially sophisticated play with peers. With improved play skills, novice players were able to find common ground with expert players in play. This, in turn, encouraged novice and expert players to continue seeking each other out and engaging together in play, which allowed for further practice and refinement of symbolic and social play abilities.

Implications of the Study

The implications of this study’s findings are discussed in terms of their importance for furthering knowledge and practice in the field. In particular, our research complements and extends a growing body of work demonstrating the therapeutic potential of play for maximizing the development and social inclusion of children with ASD. Consistent with research in this area, our study shows that with the benefit of sufficiently explicit and intensive support children with ASD are indeed capable of making considerable progress (Charman and Baron-Cohen 1997; Hobson et al. 2009, 2013; Jarrold et al. 1996; Kasari et al. 2012; Lewis and Boucher 1988). Moreover, this progress was observed in only 3 months’ time, which is the minimum duration for IPG intervention program delivery. We can speculate that it is possible that more significant gains in development may have occurred had the IPG programs been implemented for its usual duration of 6- to 9-months. This may be of particular relevance for the children more impacted with autism. As our results demonstrated, and consistent with past research, children with autism overall scored at lower levels in both the symbolic and social play domains when compared to children with ASD. However they still did progress significantly.

While adding to existing empirically validated practices, the IPG model may help to fill a gap with respect to offering more evidence-based therapeutic service options for children and their families and the professionals who serve them. Although there are noteworthy play related interventions designated as evidence based practices for children with ASD (National Autism Center 2009; Wong et al. 2013; Reichow and Volkmar 2010), few are specifically geared to addressing both the symbolic and social dimensions of play in inclusive settings beyond the preschool years, and fewer still apply practices that deviate from the principles of applied behavior analysis (for an overview, see Wolfberg and Buron 2014).

The IPG model stands out in offering a comprehensive, manualized peer play intervention that serves children of diverse ages (preschool through elementary) and applies child-centered practices following developmental principles within a sociocultural framework. To provide children with ASD sufficient and contextually relevant support, all of the factors known to affect play (both from a developmental and sociocultural perspective) have been carefully weighed and considered in the IPG model design (Wolfberg and Schuler 2006). It is our contention that the IPG model not only elicited opportunities for play development, but also created a milieu that enabled the children to thrive and generalize their newly acquired skills beyond the context of intervention. The methodical and skillful application of guided participation served to promote significant symbolic and social development within a jointly constructed play culture that accepted and normalized children’s differences (Wolfberg et al. 2012).

Another implication of this study is its potential to raise greater awareness to the critical importance of play, especially with peers, in the design and delivery of effective and meaningful interventions for children with ASD of diverse ages. This is keeping with the earlier recommendations of the National Research Council (2001) in which the teaching of play skills with peers was ranked among the top six types of interventions that should have priority in educational programs for children with ASD. One of the most compelling aspects of play as a context and target of intervention is that in addition to contributing to developmental gains, it provides for concurrent improvements in quality of life through access to enjoyable play experiences. The significance of play in childhood is so ubiquitous it is difficult to reconcile the consequence for any child who is deprived of these essential experiences. The magnitude of play deprivation is far reaching, with cascading effects that not only impact on developmental growth, but also socialization and psychological well-being throughout life (Brown 2012). This is a cost that we as society share as we seek to nurture and maximize the potential of all children to grow up to become fully functioning and contributing members.

The findings of our ad hoc analysis involving mediational effects, while fascinating, are preliminary and need to be interpreted with caution. One interpretation is that changes in symbolic play may be the mechanism driving developmental changes in social play. This is a most intriguing outcome when one considers that the children with ASD in the IPG intervention made advances in symbolic play as a part of their collective learning experience in social play with peers. According to Vygotsky (1967, 1978), pretend play by its very nature is social activity since it involves the symbolic representation of actions, themes and roles that are reflected in the larger social realm of society and culture. He further states that “learning awakens a variety of internal developmental processes that are able to operate only when the child is interacting with people in his environment and in cooperation with his peers” (Vygotsky 1978, p. 90). This leaves open questions regarding the process, relationships and paths of development for the appropriation of symbolic and social capacities in children with ASD, which would be of interest to explore for future research.

Limitations

This study has limitations and unanswered questions that deserve consideration while pointing to directions for future research. One limitation is that due to restrictions with timing it was not possible for each child with ASD to participate in all of the conditions. While a strength of using repeated measures is that it allowed us to exclude the effects of individual differences with this population that may occur in independent groups, possible threats to internal validity remain, such as practice effects and maturation. A second limitation has to do with the fact that we only considered change in frequencies (and proportions of frequencies) of play behaviors instead of duration of play behaviors. Although we expect that our coding system of play behavior events (i.e., frequencies) would be highly correlated with the duration of such behaviors, it is possible that measurement and analysis of changes in time spent engaging in various play behaviors would reveal more nuanced findings about treatment effects. Another limitation is that we were not able to control for additional treatment(s) that participants were receiving and thus cannot be certain that all treatment gains were due solely to IPG. Additionally, long-term maintenance and generalization of treatment effects were not assessed. Despite these potential drawbacks, future studies designed to mitigate these issues are warranted given this study’s strengths and positive outcomes.

Directions for Future Research

For future research, it would be relevant to examine the effects of IPG programs that are carried out for longer durations than 12 weeks as in the current study (e.g., 6 months or longer). This interest has been sparked by feedback from parents, teachers, therapists and the children themselves. Following completion of their child’s participation in this study, the vast majority of parents conveyed that they would like their children to continue participating in IPG programs not only for purposes of intervention, but also as a natural social activity that is not readily available in schools or after-school and community programs. This latter sentiment was similarly voiced by the children (both with ASD and typical peers), many of whom requested to participate again in the IPG program largely because they found it to be “fun to play with the other kids and the toys”. Apart from this study, parents, teachers and therapists whose children participated in IPG programs of longer durations (i.e., up to an entire school year) conveyed that they not only noticed a steady progression of developmental gains, but also a shift in the overall school culture to be more accepting and inclusive of these children in everyday activities, throughout the school day and after school. This is especially important for children who are significantly impacted with autism and are at a higher risk of being isolated and alientated.

There are a number of unexplored areas in this study (some touched upon in earlier IPG studies) that may be relevant to explore in future research. Given the unique relationships between play and other domains of development (see for example, Stanley and Konstantareas 2006; Toth et al. 2006), it would be pertinent to examine these areas in the context of future IPG intervention studies. For example, as there were gains in symbolic and social play, it would follow that we would observe gains in language and social communication (see for example, Zercher et al. 2001). Social communication, as the foundation that allows for peer interaction and building relationships, especially warrants close examination. It would also be pertinent to replicate and extend this study with different children who are younger (preschool age), in different settings (e.g., home) and other countries where the IPG model is being or will be implemented (e.g., Asia, Europe, Middle East, Latin America). Future investigations might also adopt alternative outcome measures and methodologies that allow for broader investigations, including those that link to the neuroscientific literature (see for example, Corbett et al. 2010; Dawson et al. 2012).

Given that play has many variations enjoyed by people young and old, it may be pertinent to further explore current adaptations of the IPG model which focus on guided participation in drama, visual arts, filmmaking, physical movement and other culturally valued activities that are of high interest for various age groups (Bottema-Beutel 2011; Julius et al. 2012; Wolfberg et al. 2012). Finally, to gain a deeper understanding of the nature and meaning of play in the lives of children with ASD, studies should endeavor to explore the experiences, relationships and play culture of children (representing diverse ages, abilities and backgrounds) within the context of IPG and other social contexts that afford children opportunities for social inclusion in play.

Notes

Due to the timing of the study with onset at the beginning of the academic school year, the first group of participants was unable to participate in the baseline assessment phase 3-months prior to treatment.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2006). Knowledge and skills needed by Speech-Language Pathologists for diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorders across the life span. http://www.asha.org/policy/KS2006-00075.htm. doi:10.1044/policy.KS2006-00075.

Attwood, A., Frith, U., & Hermelin, B. (1988). The understanding and use of interpersonal gestures by autistic and Downs syndrome children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 18, 241–257.

Bakeman, R. (2000). Behavioral observations and coding. In H. T. Reis & C. K. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Baron-Cohen, S. (1987). Autism and symbolic play. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 5(2), 139–148.

Bauminger, N., & Kasari, C. (2000). Loneliness and friendship in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development, 71(2), 447–456.

Bottema-Beutel, K. (2011). The negotiation of footing and participation structure in a social group of teens with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Interactional Research in Communication Disorders., 2, 61–83.

Boucher, J., & Wolfberg, P. J. (2003). Editorial special issue on play. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 7(4), 339–346.

Brown, S. (2009). Play: How it shapes the brain, opens the imagination, and invigorates the soul. New York: Avery-Penguin.

Brown, F. (2012). Playwork, play deprivation and play: An interview with Fraser Brown. American Journal of Play, 4(3), 267–283.

Calder, L., Hill, V., & Pellicano, E. (2013). Sometimes I want to play by myself: Understanding what friendship means to children with autism in mainstream primary schools. Autism, 17(3), 296–316.

Carter, A., Davis, N. O., Klin, A., & Volkmar, F. R. (2005). Social development in autism. In F. Volkmar, R. Paul, A. Klin, & D. Cohen (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders (3rd ed., pp. 312–334). NJ: Wiley.

Chamberlain, B., Kasari, C., & Rotheram-Fuller, E. (2007). Involvement or isolation? The social networks of children with autism in regular classroom. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 230–242.

Charman, T., & Baron-Cohen, S. (1997). Brief report: Prompting pretend play in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 27, 325–332.

Corbett, B. A., Schupp, C. W., Simon, D., Ryan, N., & Mendoza, S. (2010). Elevated cortisol during play is associated with age and social engagement in children with autism. Molecular Autism, 1(13), 1–12.

Dawson, G., Jones, E. J., Merkle, K., Venema, K., Lowy, R., Faja, S., et al. (2012). Early behavioral intervention is associated with normalized brain activity in young children with autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(11), 50–1159.

DiSalvo, C., & Oswald, D. (2002). Peer-mediated socialization interventions for children with autism: A consideration of peer expectancies. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17, 198–207.

Dissanayake, C., Signman, M., & Kasari, C. (1996). Long-term stability of individual differences in the emotional responsiveness of children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37(4), 462–467.

Dominguez, A., Ziviani, J., & Rodger, S. (2006). Play behaviours and play objects preferences of young children with autistic disorder in a clinical play environment. Autism, 10(1), 53–69.

Doody, K. R., & Mertz, J. (2013). Preferred play activities of children with autism spectrum disorder in naturalistic settings. North American Journal of Medicine and Science., 6(3), 128–133.

Elkind, D. (2007). The power of play: How spontaneous, imaginative activities lead to happier, healthier children. Cambridge, MA: De Capo Press.

Fromberg, D. P., & Bergen, D. (Eds.). (2015). Play from birth to twelve: Contexts perspectives, and meanings (3rd Ed.), New York: Routledge.

Gotham, K., Pickles, A., & Lord, C. (2009). Standardizing ADOS scores for a measure of severity in autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 693–705.

Hauck, M., Fein, D., Waterhouse, L., & Feinstein, C. (1995). Social initiations by autistic children to adults and other children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25(6), 579–595.

Hobson, J. A., Hobson, P., Malik, S., Kyratso, B., & Calo, S. (2013). The relation between social engagement and pretend play in autism. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 31, 114–127.

Hobson, R. P., Lee, A., & Hobson, J. A. (2009). Qualities of symbolic play among children with autism: A social-developmental perspective. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(1), 12–22.

Howes, C., & Matheson, C. (1992). Sequences in the development of competent play with peers: Social and social pretend play. Developmental Psychology, 28, 961–974.

Iovannone, R., Dunlop, G., Huber, H., & Kincaid, D. (2003). Effective educational practices for students with ASD. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 18(3), 150–165.

Jarrold, C. (2003). A review of research into pretend play in autism. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 7(4), 379–390.

Jarrold, C., Boucher, J., & Smith, P. (1996). Generativity deficits in pretend play in autism. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14, 275–300.

Jarrold, C., & Conn, C. (2011). The development of pretend play in autism. In A. Pellegrini (Ed.), Oxford handbook of the development of play (pp. 308–321). New York: Oxford University Press.

Jordan, R. (2003). Social play and autistic spectrum disorders. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 7(4), 347–360.

Julius, H., Wolfberg, P. J. Jahnke, I., & Neufeld, D. (2012). Integrated play and drama groups for children and adolescents on the autism spectrum: Final report. Alexander von Humboldt TransCoop Research Project, University of Rostock, Germany with San Francisco State University, USA.

Kasari, C., Roheram-Fuller, E., Locke, J., & Gulsrud, A. (2012). Making the connection: Randomized controlled trial of social skills at school for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(4), 431–439.

Lantz, J. F., Nelson, J. M., & Loftin, R. L. (2004). Guiding children with autism in play: Applying the integrated play group model in school settings. Exceptional Children, 37(2), 8–14.

Leslie, A. M. (1987). Pretence and representation: The origins of “theory of mind”. Psychological Review, 94, 412–426.

Lewis, V., & Boucher, J. (1988). Spontaneous instructed and elicited play in relatively able autistic children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 6(4), 325–339.

Libby, S., Powell, S., Messer, D., & Jordan, R. (1998). Spontaneous play in children with autism: A reappraisal. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 28, 487–497.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., Dilavore, P., & Risi, S. (1999). Manual: Autism diagnostic observation schedule. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Lowe, M., & Costello, A. J. (1976). Manual for the symbolic play test. Windsor: National Foundation for Educational Research.

MacKinnon, D. P., & Dwyer, J. H. (1993). Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Evaluation Review, 17, 144–158.

Manning, M. M., & Wainwright, L. D. (2010). The role of high level play as a predictor of social functioning in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(5), 523–533.

McCune-Nicolich, L. A. (1981). Toward symbolic functioning: Structure of early pretend games and potential parallels with language. Child Development, 52, 785–797.

McGraw, K. O., & Wong, S. P. (1996). Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 30–46.

National Autism Center. (2009). Addressing the need for evidence-based practice guidelines for autism spectrum disorders. National Autism Center’s National Standards Project: Findings and Conclusions.

National Research Council. (2001). Committee on educational interventions for children with autism, Division of behavioral and social sciences and education. Educating children with autism. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

O’Connor, T. (1999). Teacher perspectives of facilitated play in Integrated Play Groups. Unpublished Master Thesis, San Francisco State University, CA.

Ochs, E., Kremer-Sadlik, T., Sirota, K. G., & Solomon, O. (2004). Autism and the social world: an anthropological perspective. Discourse Studies, 6(2), 147–183.

Parten, M. B. (1932). Social participation among preschool children. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 27, 243–269.

Reichow, B., & Volkmar, F. R. (2010). Social skills interventions for individuals with autism: Evaluation for evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis framework. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 149–166.

Richard, V., & Goupil, G. (2005). Application des groups de jeux integers aupres d’eleves ayant un trouble envahissant du development (Implementation of integrated play groups with PDD students). Revue Quebecoise de Psychologie, 26(3), 79–103.

Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sigman, M., & Ruskin, E. (1999). Continuity and change in the social competence of children with autism, Down syndrome, and developmental delays. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64, 1–114.

Sigman, M., Spence, S. J., & Wang, A. T. (2006). Autism from developmental and neuropsychological perspectives. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 2, 327–355.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312.

Stanley, G. C., & Konstantareas, M. M. (2006). Symbolic play in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(7), 1215–1223.

Toth, K., Munson, J., Meltzoff, A. N., & Dawson, G. (2006). Early predictors of communication development in young children with autism spectrum disorder: Joint attention, imitation and toy play. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 993–1005.

Ungerer, J. A., & Sigman, M. (1981). Symbolic play and language comprehension in autistic children. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 20, 318–337.

Volkmar, F. R. (1987). Social development. In D. J. Cohen, A. M. Donnellan, & R. Paul (Eds.), Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. New York: Wiley.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1967). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 5(3), 6–18.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Westby, C. E. (2000). A scale for assessing development of children’s play. In K. Gitlin-Weiner, A. Sandgrund, & C. E. Schaefer (Eds.), Play diagnosis and assessment (2nd ed., pp. 131–161). New York: Wiley.

Williams, E. (2003). A comparative review of early forms of object-directed play and parent-infants play in typical infants and young children with autism. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 7(4), 361–377.

Williams, E., Reddy, V., & Costall, A. (2001). Taking a closer look at functional play in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 67–77.

Wing, L., & Gould, J. (1979). Severe impairments of social interaction and associated abnormalities in children: Epidemiology and classification. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 9(1), 11–29.

Wolfberg, P. J. (1994). Case illustrations of emerging social relations and symbolic activity in children with autism through supported peer play. Doctoral dissertation, University of California at Berkley with San Francisco State University. Dissertation Abstracts International, 9505068.

Wolfberg, P. J. (2003). Peer play and the autism spectrum: The art of guiding children’s socialization and imagination (integrated play groups field manual). Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Asperger Publishing Company.

Wolfberg, P. J. (2009). Play and imagination in children with autism (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Wolfberg, P. J., Bottema-Beutel, K., & DeWitt, M. (2012). Integrated play groups: Including children with autism in social and imaginary play with typical peers. American Journal of Play, 5(1), 55–80.

Wolfberg, P. J., & Buron, K. (2014). Perspectives on evidence based practice and autism spectrum disorder: Tenets of competent, humanistic and meaningful support. In K. D. Buron & P. J. Wolfberg (Eds.), Learners on the autism spectrum: Preparing highly qualified educators (2nd ed.). Shawnee Mission, KS: AAPC.

Wolfberg, P. J., McCracken, H., & Tuchel, T. (2014). Fostering play, imagination and friendships with peers: Creating a culture of social inclusion. In K. D. Buron & P. J. Wolfberg (Eds.), Learners on the autism spectrum: Preparing highly qualified educators and related practitioners (2nd ed.). Shawnee Mission KS: Autism Asperger Publishing Company.

Wolfberg, P. J., & Schuler, A. L. (1992). Integrated play groups project: Final evaluation report (Contract#HO86D90016). Washington, DC: Department of Education, OSERS.

Wolfberg, P. J., & Schuler, A. L. (1993). Integrated play groups: A model for promoting the social and cognitive dimensions of play. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 23(3), 1–23.

Wolfberg, P. J., & Schuler, A. L. (2006). Promoting social reciprocity and symbolic representation in children with autism spectrum disorders: Designing quality peer play interventions. In: T. Charman, & W. Stone (Eds.), Social and communication development in autism spectrum disorders: Early identification, diagnosis, and intervention (pp. 180–218). New York: Guilford Publications.

Wolfberg, P. J., Zercher, C., Lieber, J., Capell, K., Matiaas, S. G., Hanson, M., et al. (1999). Can I play with you? Peer culture in inclusive preschool programs. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 24, 69–84.

Wong, C., Odom, S. L., Hume, K. Cox, A. W., Fettig, A., Kucharczyk, S., & Schultz, T. R. (2013). Evidence-based practices for children, youth, and young adults with autism spectrum disorder. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina, Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute, Autism Evidence-Based Practice Review Group.

Yang, T., Wolfberg, P. J., Wu, S., & Hwu, P. (2003). Supporting children on the autism spectrum in peer play at home and school: Piloting the integrated play groups model in Taiwan. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practice, 7(4), 437–453.

Zercher, C., Hunt, P., Schuler, A. L., & Webster, J. (2001). Increasing joint attention, play and language through peer supported play. Autism: The International Journal of Research and Practices, 5, 374–398.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our deep appreciation to Autism Speaks for the funding of our grant and the many people involved in our research project. We are especially indebted to the children and families, IPG guides, IPG assistants and partner school sites for their generosity and support. We extend special thanks to Kristen Bottema-Beutel for her research support and thoughtful critique of this study. We also thank our research assistants Cristina Blanco, Cornelia Bruckner, Jessica Dow, Jenny Hernandez, Elizabeth Hooper, Sophia Lo, Katrina Martin, Sarah Mast, Heather McCracken, Sunaina Nedungadi, Luke Remy, Nevin Smith and the UC, Berkeley student URAP teams. We are grateful to members of our steering committee, including the late Adriana Loes Schuler whose enduring spirit lives on in the IPG model.

Ethical standard

This study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects, Internal Review Board of the lead university, and therefore has been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. Informed written consent was obtained from a parent/legal guardian for all participants, and verbal assent was obtained for participants 9–10 years of age prior to inclusion in the study. Details that might disclose the identity of the subjects under study have been omitted.

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have a financial relationship with Autism Speaks, the organization that sponsored the research. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wolfberg, P., DeWitt, M., Young, G.S. et al. Integrated Play Groups: Promoting Symbolic Play and Social Engagement with Typical Peers in Children with ASD Across Settings. J Autism Dev Disord 45, 830–845 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2245-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2245-0