Abstract

This study characterized early language abilities in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders (n = 257) using multiple measures of language development, compared to toddlers with non-spectrum developmental delay (DD, n = 69). Findings indicated moderate to high degrees of agreement among three assessment measures (one parent report and two direct assessment measures). Performance on two of the three measures revealed a significant difference in the profile of receptive–expressive language abilities for toddlers with autism compared to the DD group, such that toddlers with autism had relatively more severe receptive than expressive language delays. Regression analyses examining concurrent predictors of language abilities revealed both similarities in significant predictors (nonverbal cognition) and differences (frequency of vocalization, imitation) across the diagnostic groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Language and communication skills comprise a critical dimension of the autism phenotype. Language abilities are one of the most variable characteristics of individuals with autism (Lord et al. 2004; Thurm et al. 2007). The need for additional investigation of early language development and language processes in this population has been emphasized by several researchers (Beeghly 2006; Gernsbacher et al. 2005). More sophisticated, finer-grained investigations using psycholinguistic methods such as novel word learning tasks or eye tracking are beginning to be undertaken with toddlers on the autism spectrum (McDuffie et al. 2006; Swensen et al. 2007). While these studies provide valuable insights, they typically involve relatively limited sample sizes and focus on a narrow aspect of linguistic ability. It is equally important at this stage of investigation, to establish a clear characterization of global language abilities in toddlers on the autism spectrum based on various indices of language development.

There is limited information in the literature regarding language development in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Much of what is known about early language abilities has been gleaned from parent report data (Charman et al. 2003b; Luyster et al. 2007), with the exception of one recent comprehensive study that employed multiple assessment measures (Luyster et al. 2008). A few smaller-scale studies also provide information about language development in toddlers with ASD (Eaves and Ho 2004; Mitchell et al. 2006; Paul et al. 2008). Findings from these investigations consistently indicate that: (1) as a group, toddlers with ASD exhibit substantial delays in language development relative to age-level expectations and often display early delays in language beyond their nonverbal cognitive level; (2) there is considerable individual variation in language development within the autism spectrum; and (3) significant delays in both receptive and expressive language are common in toddlers with ASD. Although the findings are somewhat mixed, there is evidence to suggest that the typical receptive language advantage over expressive language is not observed in toddlers on the autism spectrum (Charman et al. 2003b; Luyster et al. 2007, 2008). An area of disagreement in the literature pertains to whether diagnostic category (autism vs. PDD or PDD-NOS) is associated with differences in early language levels or profiles (Charman et al. 2003b; Eaves and Ho 2004; Luyster et al. 2007). Prior research has only begun to examine predictors of early language abilities within the autism spectrum; therefore, further research is needed before general conclusions can be drawn. A more detailed account of findings from these previous studies is provided below.

Charman et al. (2003b) examined early language development in a large sample of young children with ASD using the Infant Form (Words and Gestures) of the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (CDI). Performance was analyzed on the basis of CA as well as nonverbal mental age. The ASD group was significantly delayed compared to the CDI normative data (there was no separate control group included in the study). As is the case for typical language development, there was considerable variability in language acquisition in the ASD sample. The ASD children displayed other commonalities with the normative sample. Word comprehension was developmentally ahead of word production in absolute terms (i.e., children understood more words than they used expressively), gesture production served as a bridge between word comprehension and production, and the broad pattern of word category acquisition followed the typical pattern.

Nevertheless, the findings of Charman et al. (2003b) also differed from the typical pattern (CDI normative sample) in a couple of notable ways. The production of early gesture (sharing reference) was delayed relative to later gestures (use of objects). Additionally, the typical language comprehension advantage over production was reduced in the children with ASD (there was less of a gap than usual between what children could understand and what they were able to express). Despite significant delays in comprehension and production for both the CA and nonverbal mental age analyses, language abilities for this sample of ASD children showed clear developmental trends across age levels. It is important to note, however, that this finding was based on cross-sectional rather than longitudinal data. Charman et al. also examined potential differences in early language and communication profiles for autism versus PDD diagnoses. When nonverbal mental age was controlled, the only significant difference reported was that children with autism produced fewer early gestures than children with PDD.

Luyster et al. (2007) conducted an investigation of early communication and language development modeled after the study by Charman et al. (2003b). The CDI was used to examine parental report of vocabulary comprehension and production, nonverbal communication skills, functional object use, and play skills in a large sample of young children, consisting of toddlers with ASD, developmental delay (DD), as well as typically developing toddlers. The overall findings from the Luyster et al. (2007) investigation were generally consistent with those of Charman et al. (2003b). Advances in language and communication skills were observed with increases in CA and nonverbal mental age; however, the majority of children with ASD exhibited significant delays in each of the areas assessed, including receptive and expressive vocabulary. When compared to the DD and typically developing comparison groups, the ASD sample was similar with respect to vocabulary profiles and gesture patterns. However, findings suggested that compared to CDI normative data children with ASD may have a smaller gap between their receptive and expressive vocabulary than is typically observed.

There was one aspect in which the findings of Luyster et al. (2007) did differ from those of Charman et al. (2003b). When performance on the CDI was examined according to diagnostic classification, Luyster et al. found group differences on a number of variables, even after accounting for group differences in nonverbal IQ. In each case the autism group scored significantly lower than the PDD-NOS group. The groups displayed significant differences in the number of words understood, words produced, late appearing gestures, phrases understood, and first signs of understanding/starting to talk. There was no group difference in number of early appearing gestures, which was the only area of difference across diagnostic groups reported by Charman et al. (2003b). Luyster et al. speculated that this discrepancy between their findings and those of Charman et al. may be related to differences in the diagnostic processes employed by the two investigations.

In a recent paper Luyster et al. (2008) reported findings from a comprehensive investigation of language profiles within a large sample of toddlers with ASD who ranged in age from 18 to 33 months. Language abilities were assessed using two parent report measures, the CDI and the Communication subscale of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales, as well as the receptive and expressive language scales from the Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Language scores on these three measures were significantly correlated (p < .001), ranging from .52 for receptive language scores on the Mullen and CDI to .88 for expressive language scores on the Vineland and CDI. As a group, toddlers with ASD exhibited delays in both receptive and expressive language abilities across the various measures, with expressive language scores significantly higher than receptive language scores on two of the three measures. A number of predictors of concurrent language abilities were examined, including chronological age, nonverbal cognition, imitation, play, gestures, initiation of joint attention (IJA), response to joint attention (RJA), and motor skills. For receptive language, significant concurrent predictors were gestures, nonverbal cognition, and RJA. Significant predictors of expressive language included nonverbal cognition, gestures, and imitation.

A few smaller-scale investigations have also provided insight into early language skills in ASD (Eaves and Ho 2004; Mitchell et al. 2006; Paul et al. 2008). Eaves and Ho (2004) conducted a study designed to examine outcomes of early identification of autism. Although the focus of their investigation was not on language development, information was presented regarding early language abilities. At the first clinic visit (mean age of 33 months) approximately 70% of the toddlers in this sample reportedly performed below 12 months in receptive and expressive language and nearly half of the sample did not use real words. Children diagnosed with autistic disorder scored significantly lower than those with PDD-NOS on all developmental measures, including measures of receptive and expressive language.

A follow-up study was also conducted by Paul et al. (2008) that yielded information about language abilities in toddlers with ASD. Receptive and expressive language abilities were assessed using multiple parent report measures and direct observation instruments. Findings from the initial assessment (15–25 months) indicated that toddlers with ASD displayed significant deficits in both receptive and expressive language relative to chronological age norms and compared to their own nonverbal abilities. Comparable results were obtained through parent report measures (CDI and Vineland) and direct assessment (Mullen).

Mitchell et al. (2006) collected parent report data on communication and language development at 12 and 18 months for siblings of children with ASD and low-risk controls, using the Infant Form of the CDI. Language abilities were also directly assessed at 12 and 24 months with the Preschool Language Scale—Third Edition (PLS-3) or the Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Findings from the CDI revealed significant delays for the ASD sibling group compared to the non-ASD siblings and the controls. At 12 months the ASD siblings comprehended fewer phrases and produced fewer early and late gestures than the comparison groups. Delays in receptive and expressive vocabulary, comprehension of phrases, and use of gestures were found at 18 months for the ASD group. Significant delays in the ASD group’s language comprehension and production relative to the comparison groups were observed at both 12 and 24 months based on performance on the Mullen/PLS-3. Mitchell et al. concluded that very early delays in communication and language abilities should be monitored in surveillance for ASD, particularly difficulties in gesture use.

The studies reviewed above have begun to provide a picture of early language and communication development in ASD. However, there are certain limitations in the research to date. With the exception of the recent study by Luyster et al. (2008), the larger-scale investigations of language abilities in young children on the autism spectrum consist of fairly wide age ranges (Charman et al. 2003b; Luyster et al. 2007). This means that there was a relatively small sample size at any given age level. Further, overall group patterns may be distorted by including a broad range of development (e.g., 18 months to 7 years) in the characterization of early language abilities. Additionally, two of the comprehensive reports are based solely on a single parent report measure. While the CDI is a well-regarded measure that has been shown to be a valid assessment tool for various special populations (e.g., Heilmann et al. 2005; Thal et al. 2007), its use with infants and toddlers on the autism spectrum is relatively new and has not received much scrutiny. A few investigators have started to examine the validity of specific measures for assessing young children with ASD (Akshoomoff 2006) and the inter-correlation between language assessment measures (Hudry et al. 2008; Luyster et al. 2008); however, more investigation of these issues is warranted. Many of the prior studies of early language abilities in young children on the autism spectrum have not included comparison groups, but have instead relied on published test norms for interpretation. The benefits and need for cross-population comparisons in the area of language development have been emphasized by several investigators (Beeghly 2006; Rice and Warren 2004). Most of the investigations that have compared language abilities across populations have involved preschool or school age children with ASD (Bishop and Norbury 2002; Kjelgaard and Tager-Flusberg 2001; Rice et al. 2005; Shulman and Guberman 2007); cross-population examinations of language acquisition involving infants and toddlers with ASD are scarce. The current study is designed to address these limitations and to help resolve areas of disagreement in the literature in order to further our understanding of early language profiles in a carefully identified sample of toddlers, within a narrowly defined developmental range.

Purpose

The primary purpose of this study was to characterize early language skills in a large sample of toddlers on the autism spectrum (i.e., diagnosed with Autism or Pervasive Developmental Disorders-Not Otherwise Specified, PDD-NOS) using multiple measures of language development and to compare language performance to a group of toddlers with non-spectrum DD. Specific research questions that were addressed were as follows: (1) What are the profiles of overall language abilities relative to chronological age and nonverbal cognitive level for toddlers with Autism, PDD-NOS, and DD?; (2) What are the associations between language scores obtained from three different standardized language measures—one parent report and two direct assessment measures—in the evaluation of language abilities of toddlers on the autism spectrum?; (3) Are there significant group differences in receptive and/or expressive language skills, when controlling for possible differences in nonverbal cognition?; (4) What are concurrent predictors of language abilities for toddlers with Autism, PDD-NOS, and DD?; and (5) What is the nature of individual variation in language abilities for these groups?

Methods

Participants

This sample is comprised of participants in clinical research conducted by Lord and colleagues over a number of years at the University of Chicago and the University of Michigan. About one-third of the sample overlaps with the sample reported by Luyster et al. (2007). The majority of toddlers in the sample were seen for an initial evaluation for suspected autism. The sample also was comprised of a group of toddlers with DD who did not have autism. Assessment findings for a total of 326 toddlers were examined in the current report, including 257 toddlers with ASD (179 with Autism, 78 with PDD-NOS) and 69 toddlers with DD. Participants ranged in age from 24 to 36 months, with a mean age of 30.6 months (SD = 3.6) at the time of testing. Males comprised 78% of the sample whereas females comprised 22% of the sample (254 males, 71 females, 1 missing data point). The racial and ethnic breakdown of the sample was: 75% white, 22% African American, 2% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 1% biracial. A summary of participant characteristics is provided in Table 1, broken down by the diagnostic categories described below.

The data presented in this paper come from two longitudinal studies of early diagnosis of ASD. The first longitudinal study involved a sample of children referred for possible autism at the age of 2. Children in the ASD and DD groups were assessed when they were approximately 2, 3, 5, and 9 years old. The second longitudinal study involved a sample of children ages 12 to 36 months of age who were at-risk for ASD based on family history (i.e., having an older sibling with ASD) or clinic referral. Children in this study were assessed monthly using the ADOS and experimental language and imitation tasks. Every 6 months, participants in Study 2 were seen by a clinician researcher unfamiliar with the child’s history, diagnosis, and previous assessment results and they underwent more detailed assessment. This assessment included developmental testing and the ADOS, and the clinician researcher assigned a best estimate diagnosis based on this information.

Both studies used similar assessment procedures for the initial and follow-up evaluations. At the initial evaluation, families underwent a two-part standardized assessment involving a number of diagnostic and cognitive measures. These measures included the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (Lord et al. 1994) and the Pre-Linguistic Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (PL-ADOS) (DiLavore et al. 1995), Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord et al. 1999), or Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule—Toddler Module (Luyster et al. 2009). Each child was assigned a clinical diagnosis of autism, PDD-NOS or a non-spectrum disorder when seen at ages 2 (for participants in Study 2, diagnoses were given earlier when appropriate and were re-evaluated by a clinician unfamiliar with the child and blind to diagnosis at age 2). In the present study, only data from the age 2 assessment from Study 1 were used, and data closest to age 30 months were used from Study 2.

Autism Diagnosis

Following each of the age 2 assessments, the two clinicians who had been involved in the assessment met to review the results and decide on a clinical diagnosis (i.e., a child who was referred for possible autism did not necessarily receive a diagnosis on the autism spectrum). Independent best estimate diagnoses of autism, PDD-NOS, and non-spectrum disorders were then generated by an experienced clinical researcher unfamiliar with the child’s history, using the scores and observations made during testing. When this diagnosis did not agree with the diagnosis of the research clinician who had seen the child, the study director and an independent examiner reviewed all the information, watched the video of the child assessment and reached a consensus best estimate diagnosis. In the current study, diagnostic status was based on best estimate diagnoses at age 2.

All clinical and best estimate diagnoses were based on formal assessment scores and observations used during testing, including observations and scores from the ADI-R and ADOS. All of these data were considered as part of the clinical judgment that determined final diagnosis, and formal classifications on the ADOS and ADI-R were considered in the context of other formal testing results and observations. In other words, if the ADOS and/or ADI-R classification did not agree with the clinician’s judgment of diagnosis, the clinician’s diagnosis was considered the gold standard, and best estimate diagnosis was made based on clinician’s diagnosis.

Nonverbal Cognition

In this sample, cognitive abilities were assessed using the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen 1989 and 1995). For the purposes of this study, it is important to take nonverbal cognitive abilities into account when assessing language abilities across the diagnostic groups; therefore, nonverbal cognition was indexed via a composite score on the Mullen Visual Receptive Organization and Fine Motor subtests.

Language Measures

One of the standardized measures used in this study is a parent report instrument (Vineland), whereas the other two measures entail direct assessment of the child (as well as some parent report items). One measure was specifically designed to assess language and communication skills (Sequenced Inventory of Communication Development), while the other two provided evaluations of receptive and expressive language as part of a broader developmental assessment. As noted above, these measures were administered by Lord and colleagues over a number of years; the measures were selected to provide a comprehensive assessment of development in toddlers with ASD, rather than focusing solely on language development. Therefore, two of the measures in the present study are subtests from developmental scales that are commonly used by psychologists to evaluate early DD or disorders across various domains.

The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow et al. 1984) and the Vineland-II Adaptive Behavior Scales (Sparrow et al. 2005) focus on birth through adulthood. Domains assessed include communication of both receptive and expressive language abilities, daily living skills, socialization, and motor skills. The interview edition, survey form and expanded form are administered to a parent or caregiver in a semi-structured interview format. The sequenced inventory of communication development (SICD) (Hendrick et al. 1984) is designed to evaluate communication abilities of young children with and without DD functioning between 4 and 48 months. The SICD is comprised of two major sections—receptive and expressive. The receptive portion of the SICD includes items to tap speech sound discrimination, phonological awareness, and language understanding. The expressive portion consists of items that assess imitating, initiating, and responding and also assesses length of productions and use of grammatical structures. The Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen 1995) focuses on development from birth to 68 months. It is designed to determine the need for special services and assess areas of strengths and weaknesses. Five scales assess motor, cognitive, and language abilities—these scales include: gross motor, fine motor, visual reception, receptive language, and expressive language. The receptive language scale includes items such as identifying body parts and following commands. The expressive language scale consists of items such as answering questions and naming pictures.

The SICD provides age equivalent (AE) scores but does not provide standard scores. Similarly, only AE scores are provided for the receptive and expressive subdomains of the Vineland even though this measure provides standard scores for the communication composite. AE scores are reported in the current study given that these were the only common scores available (other than raw scores) for the three language assessment measures. While the psychometric limitations of AE scores are acknowledged, it is not uncommon for investigations of early language development to report AE scores due to the lack of standard scores on a number of these measures. Further, variability in performance can be more readily captured through the use of AE scores than standard scores for young children with disabilities in cases where they display near basal performance on standardized measures.

Concurrent Predictors of Language Abilities

In addition to the measure of nonverbal cognition described above, select items from the ADOS or PL-ADOS were examined as possible concurrent predictors of receptive and/or expressive language abilities for the three diagnostic groups. The items included: Gestures (Module 1), Imitation during the Birthday Party task, Play total score (combined score from functional and imaginary play), Joint Attention (combined score from Initiating Joint Attention and Responding to Joint Attention) and Frequency of Vocalization. These items were selected as potential predictors because they represent constructs that have been shown to be related to language skills in prior reports in the literature and ongoing investigations (Charman et al. 2003a, b; Luyster et al. 2008; Mitchell et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2007). Preliminary analyses using Pearson correlations confirmed that each of the selected variables was significantly correlated with receptive and expressive language scores on all of the measures for the current sample. It should be noted that correlations for items from the ADOS/PL-ADOS were negative because higher scores on that measure indicate more atypical performance. The predictor variables were correlated with language scores (p < .001) as follows: Gestures r = −.366 to −.589, Imitation r = −.513 to −.594, Play r = −.615 to −.710, Joint Attention r = −.362 to −.655, Frequency of Vocalization r = −.560 to −.642, and Nonverbal Cognition r = .483 to .664. These significant correlates were entered into regression models as described below.

Results

Group Language Abilities Relative to Chronological Age and Nonverbal Cognition

There was considerable consistency in performance across the different measures of language comprehension and production used in this study, both in terms of mean group data and correspondence at the individual level. Descriptive group data (age equivalent scores) for the three language measures for each diagnostic group (Autism, PDD-NOS, DD) are summarized in Table 2, broken down by receptive versus expressive language scales (statistical comparisons are reported in detail in a later section). The two groups of toddlers who received autism spectrum diagnoses (Autism and PPD-NOS groups) exhibited substantial delays on each of the language measures, with the Autism group’s mean language age equivalent scores ranging from 8 to 11 months and the PDD-NOS group’s scores ranging from 11 to 17 months. In contrast, the toddlers with DD who did not meet ASD criteria exhibited somewhat less severe language difficulties such that age equivalent scores ranged from 16 to 21 months.

As a group, toddlers in each of the diagnostic categories also exhibited nonverbal cognitive delays relative to their mean chronological age based on their performance on the Mullen Visual Receptive Organization and Fine Motor subtests. The mean composite nonverbal age equivalent scores for each group were as follows: Autism group = 20.7 (SD = 5.7); PDD-NOS group = 23.5 (SD = 6.8); and DD group = 22.3 (SD = 7.4). There was a statistically significant, though small, diagnostic group effect for nonverbal cognitive abilities, F(2, 294) = 5.036, p = .007, ŋ 2p = .033, with least significant difference (LSD) comparisons revealing that the PDD-NOS group scored significantly higher than the Autism group (2.839, p = .002).

In terms of average group performances, the Autism group demonstrated language delays ranging from 20 to 23 months relative to their CA and 10 to 13 months relative to their nonverbal cognitive level. The PDD-NOS group’s mean language scores ranged from 14 to 20 months below their mean CA and 7 to 13 months below their mean nonverbal cognitive score. Less of a discrepancy was observed in these profiles for the DD group. Their average language delays ranged from 9 to 14 months compared to their CA and 1 to 6 months compared to nonverbal cognition.

Correlations Between Language Measures

For the sample as a whole, performance was highly correlated for the various language measures when considering either comprehension scores or production scores. Pearson correlations ranged from r = .910, p < .001 for receptive language on the Mullen compared to receptive language scores on the SICD to r = .732, p < .001 for expressive language on the Vineland and SICD. In order to determine the extent to which nonverbal cognition affected associations between the language measures, partial correlations were also computed (controlling for nonverbal age equivalent scores on the Mullen). A similar pattern of significant partial correlations was found for the sample as a whole. Partial correlations ranged from r = .873, p < .001 for Mullen receptive language scores compared to SICD receptive language scores to r = .645, p < .001 for expressive Vineland scores compared to expressive SICD scores. Pearson correlations and partial correlations for receptive–receptive and expressive–expressive language scores on each of the measures are reported for the three diagnostic groups in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Group Differences in Receptive and Expressive Language

General linear model repeated measures analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were used to compare the language performance of toddlers with Autism, PDD-NOS, and DD. Nonverbal age equivalent scores on the Mullen were used as a covariate to control for group differences in nonverbal cognitive abilities when assessing performance on the language measures. Separate ANCOVAs were conducted for each of the language measures. Diagnostic category (Autism, PDD-NOS, DD) was the between-subjects variable and language domain (receptive, expressive) was the within-subjects variable. LSD tests were used to assess pairwise comparisons for significant interaction effects.

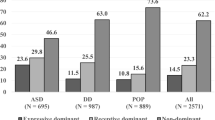

Findings were quite similar across language measures. In each analysis, there was a significant diagnosis effect (the Autism group scored lower than PDD-NOS group who scored lower than the DD group) and a significant diagnosis × language domain interaction effect (see Fig. 1 for an overview of the three language measures and Fig. 2 for a breakdown of each individual measure). The following specific results were obtained. On the Mullen there was a significant diagnosis effect, F = 56.623 (2, 287) p < .001, ŋ 2p = .283 and diagnosis × language domain interaction, F = 33.821 (2,287), p < .001, ŋ 2p = .191. With respect to the diagnostic group main effect, the DD group scored significantly higher than the PDD-NOS group who scored significantly higher than the Autism group on receptive language (p < .001). The same pattern was found for expressive language measures (p < .05). These diagnostic group findings were subsumed by significant interaction effects involving language domain. Pairwise comparisons revealed that the DD group obtained a significantly higher age equivalent score on the Mullen for receptive language than expressive language (p < .05), whereas the Autism group had a significantly higher expressive language score than receptive language (p < .05). There was no significant difference in the PDD-NOS groups’ performance on the receptive and expressive language domains for the Mullen.

Overview of diagnosis × language domain effects on all three assessment measures, plotted as mean age equivalent scores for the developmental delay group (DD), pervasive developmental disorders-not otherwise specified group (PDD), and autism group (AUT) on the Mullen scales of early learning (Mullen), sequenced inventory of communication development (SICD), and Vineland adaptive behavior scales (Vineland)

Diagnosis × language domain interaction effects for each individual assessment measure, plotted as mean age equivalent scores for the developmental delay group (DD), pervasive developmental disorders-not otherwise specified group (PDD), and autism group (AUT) on the Mullen scales of early learning (Mullen), sequenced inventory of communication development (SICD), and Vineland adaptive behavior scales (Vineland)

For the SICD a significant diagnosis effect was observed, F = 49.476 (2, 201), p < .001, ŋ 2p = .330, as well as a significant diagnosis × language domain interaction, F = 15.142 (2, 201), p < .001, ŋ 2p = .131. In terms of the main effect for diagnosis, the DD group scored higher than the PDD-NOS group who outperformed the Autism group in terms of receptive language (p < .001) and expressive language (p < .05). However, this main effect must be interpreted within the context of the higher-level interaction effects. As was the case for the Mullen, the DD group exhibited significantly higher scores on receptive language than expressive language (p < .05), the Autism group scored higher on expressive language than receptive (p < .05), and there was not a significant language domain effect for the PDD-NOS group.

Similar to the other two language measures, performance on the Vineland revealed a significant diagnosis effect, F = 46.377(2, 261), p < .001, ŋ 2p = .262 and a diagnosis × language domain interaction effect, F = 7.043(2, 261), p = .001, ŋ 2p = .051. The relative ordering of performance across groups on the Vineland was the same as for the other language measures, with the DD group > PDD-NOS group > Autism group for receptive language (p < .001) and expressive language (p < .01). However, the specific pattern of receptive–expressive language relationships among the groups on the Vineland was somewhat different than on the two prior language measures. On this measure, both the DD and Autism group displayed significantly better receptive language scores than expressive language (p < .05), with the PDD-NOS group showing no significant difference in performance on the two language domains.

Concurrent Predictors of Receptive and Expressive Language

Step-wise multiple regression analyses were used to assess concurrent predictors of receptive and expressive language abilities. Six predictor variables were entered into the model: nonverbal cognition (age equivalent score from the Mullen), joint attention, play, gestures, imitation, and frequency of vocalization (items from the ADOS or PL-ADOS). The criterion variable was composite receptive language score or composite expressive language score. Regression analyses were based on cases where there were valid scores for at least two of the three language measures. The composite score was the average of the 3(2) measures.

Predictors of composite receptive language abilities were examined for each diagnostic group (see Table 5). A three-step regression model significantly predicted receptive language for the Autism group, F(3,86) = 15.410, p = .000, whereas a two-step model predicted composite receptive language scores for the PDD-NOS group, F(2,43) = 27.721, p = .000. A three-step model significantly predicted composite receptive language abilities for the DD group, F(3,40) = 26.115, p = .000. As seen in Table 5, three predictors—nonverbal cognition, frequency of vocalization, and play—accounted for 36% of the variance in the Autism group’s composite receptive language scores. Nonverbal cognition and joint attention accounted for 58% of composite receptive language scores for the PDD-NOS group. For the DD group, nonverbal cognition, joint attention, and imitation accounted for 68% of the variance in composite receptive language scores.

Another set of step-wise multiple regression analyses were completed to investigate predictors of composite expressive language scores (Table 6). A three-step regression model significantly predicted composite expressive language scores for the Autism group, F(3,86) = 25.474, p = .000, whereas two-step models significantly predicted composite expressive language for the PDD-NOS group, F(3,43) = 25.671, p = .000, and the DD group, F(2,40) = 24.995, p = .000. As seen in Table 6, nonverbal cognition, frequency of vocalization, and play accounted for 48% of the variance in the Autism group’s composite expressive language scores. Nonverbal cognition and joint attention accounted for 56% of the variance for the PDD-NOS group, and nonverbal cognition and imitation accounted for 57% of the variance in composite expressive scores for the DD group.

Individual Variation in Language Abilities

An examination of individual scores on the three language measures was completed to assess patterns of individual variation across the diagnostic groups. Although the majority of toddlers in all three groups obtained scores indicative of delays in language development, consistent with the group findings, it was noted that there were some toddlers within each diagnostic category who displayed normal range language scores. For the purposes of this analysis, normal range language scores were defined as: (a) two scores at or above chronological age (CA) level; or (b) one score at or above CA plus two other scores within 2 months of CA. Using this operational definition there were five toddlers in the Autism group (out of 179 or 3%), six toddlers in the PDD-NOS group (out of 78 or 8%), and eight toddlers in the DD group (out of 69 or 12%) who exhibited typical language scores. The five toddlers with normal range language abilities in the Autism group had nonverbal cognitive age equivalent scores that were above or within 1 month of their CA. For the PDD-NOS group, all of the toddlers with typical language scores exhibited nonverbal cognitive scores that matched or exceeded their CA. Six of the eight toddlers in the DD group with normal range language scores had nonverbal cognitive scores that at least met their CA level, whereas two toddlers had a 5 month discrepancy (CA = 32 months, nonverbal cognition = 27 months).

Discussion

Language Profiles Relative to CA and Nonverbal Cognition

Toddlers on the autism spectrum demonstrated significant delays based on age level expectations in both comprehension and production as a group, but considerable variability was evident. Prior research has similarly noted the extent of variability in language abilities in ASD (Lord et al. 2004; Smith et al. 2007). As might be expected given diagnostic criteria, children in the Autism group demonstrated more severe language deficits than the PDD-NOS group. Eaves and Ho (2004) found that young children with autism performed significantly worse than those with PDD-NOS on all measures (cognitive, language, and adaptive behavior). With respect to nonverbal cognitive level, toddlers with ASD in the present study displayed significant discrepancies for both receptive and expressive language abilities. In other words, there was a substantial gap between their language skills and their nonverbal cognitive level. In contrast, the toddlers with DD had average receptive language levels (ranging from 20 to 21 months) that were roughly commensurate with their mean nonverbal cognitive level (22 months), with somewhat lower expressive language levels. These findings suggest that even when toddlers with ASD have strong nonverbal cognitive abilities they often have delays in receptive and expressive language.

Group Differences in Receptive and Expressive Language

In the current study there was a significant diagnostic group by language domain interaction effect for each of the language measures. Two of the three language measures revealed an atypical profile of receptive–expressive language abilities for toddlers in the Autism group compared to the DD group. As observed in typical development, the DD toddlers displayed higher receptive language than expressive language abilities. On the other hand, the Autism group showed the reverse pattern. Toddlers with autism received higher age equivalent scores for expressive than receptive language on the Mullen and SICD, while the PDD-NOS group exhibited a relatively flat profile across the two language domains. Although the Autism group, like the DD group, displayed a significant receptive language advantage on the Vineland, the performance of the PDD-NOS group on the two language domains was not significantly different.

On the surface, the discrepancy between the findings based on the Vineland and those of the other two measures may seem to relate to the fact that the Vineland is a parent report survey whereas the Mullen and SICD involve direct assessment. It is possible that direct assessment tasks administered by clinicians underestimate comprehension abilities in toddlers with autism. Alternatively, parents may overestimate young children’s receptive language abilities as it is difficult to distinguish (in everyday situations) between understanding of vocabulary words and grammatical sentence structures versus apparent understanding of the linguistic message through the use of world knowledge and contextual information. However, prior findings of atypical receptive–expressive language profiles in toddlers with ASD have been based on the CDI, which is also a parent report measure. Rather than being a function of parent report versus direct assessment measures, the inconsistent findings may relate to item differences across these specific measures—as described below.

The finding of possible atypicalities in the receptive–expressive language profiles in ASD is consistent with results from investigations based solely on parent report data from the CDI (Charman et al. 2003b; Luyster et al. 2007), as well as other recent findings that also included direct assessment measures (Ellis Weismer et al. 2008; Hudry et al. 2008; Luyster et al. 2008; Mitchell et al. 2006). Luyster et al. (2008) found that toddlers with ASD had significantly higher age equivalent scores for expressive language than receptive language on the Mullen and the CDI. However, like the current study, a significant receptive advantage over expressive language was found for the Vineland. They suggested that this finding may be an artifact of the imbalance of receptive (20) and expressive (54) items on the Vineland, such that attaining items on the receptive scale may yield larger gains in age equivalent scores than on the expressive scale. Mitchell et al. (2006) investigated early language abilities in siblings of children with ASD who also were diagnosed with ASD at 24 months; they reported mean standard scores for 14 toddlers tested with the Mullen Scales of Early Learning and two toddlers tested with the Preschool Language Scale-3 (PLS-3). On both language measures mean receptive standard scores were lower than expressive standard scores by approximately nine points. This pattern was not observed for non-ASD siblings or for controls. There is some preliminary indication based on the present findings that this atypical comprehension-production profile may be a distinctive marker of early autistic language development (more so than for PDD-NOS). Eaves and Ho (2004) also reported a lack of receptive advantage for 33 month-old toddlers with autism who had an average age equivalent of 9.1 months for receptive language and 9.8 months for expressive language, whereas toddlers with PDD-NOS at that age exhibited an average receptive language level of 14.4 months and expressive language level of 12.3 months. Further research is needed which employs more implicit measures of language comprehension such as (eye tracking paradigms) in order to clearly establish receptive language abilities and to more definitively characterize the nature of receptive–expressive profiles in toddlers with ASD.

Agreement Among Language Measures

For the toddlers in the present study with ASD (the Autism and PDD-NOS groups) each of the language assessment measures was significantly correlated for receptive–receptive and expressive–expressive language comparisons (p < .001), even when controlling for the overlap in performance accounted for by nonverbal cognition. These associations were moderate to high (.45 to .83), indicating considerable overlap in the language constructs being assessed across the measures. For the toddlers on the autism spectrum, the comparison of performance on the two direct assessment measures (Mullen and SICD) yielded the highest correlation of any of the measures for receptive language but the lowest correlation across the measures for expressive language. A different pattern was seen for the DD group in which the two direct assessment measures were highly correlated for both receptive and expressive language (.84 and .76, respectively).

Luyster et al. (2008) examined the associations between scores obtained from three assessment measures for toddlers with ASD, the CDI, Mullen, and Vineland. All of the measures were significantly correlated (p < .001); however, somewhat lower correlations were found for receptive language (R = .52 to .77) than for expressive language (R = .82 to .88). Akshoomoff (2006) reported significant correlations between Mullen age equivalent scores and Vineland age equivalent scores for receptive language (r = .53, p < .05) and for expressive language (r = .78, p < .01). The current study and the investigation by Luyster et al. (2008) also compared performance of children with ASD on the Mullen and Vineland. Luyster et al. reported that correlations between the Mullen and Vineland were .53 for receptive language and .85 for expressive language. Similar findings were reported across these two prior studies, with somewhat lower correlations for receptive than expressive language. In the current study, the sample was divided based on Autism and PDD-NOS diagnoses. For the Autism group, the Mullen–Vineland receptive correlation was .72 and expressive language was .67; for the PDD-NOS group the receptive language correlation was .63 and expressive language correlation was .79. The slightly lower correlation for receptive language reported in the other studies was only observed for the PDD-NOS group in the current investigation. In both the Luyster et al. and Akshoomoff studies the sample was identified in terms of ASD, rather than being broken down by diagnostic category. It is possible that those samples included a higher proportion of children with PDD-NOS relative to the sample in the present study, leading to a somewhat different pattern of inter-measure correlations for receptive and expressive language performance.

Concurrent Predictors of Language Abilities

Results from the regression models revealed both similarities and differences across the diagnostic groups in the current investigation in terms of concurrent predictors of language and communication. Nonverbal cognition was the most robust concurrent predictor of composite receptive and composite expressive language across the three groups in this investigation. Findings from Luyster et al. (2008) were consistent with the results from the present investigation in that nonverbal cognition was a significant concurrent predictor of language abilities for toddlers with ASD. There are mixed findings in the literature regarding the association between nonverbal cognitive skills and language abilities in ASD for studies examining variables that predict later language outcomes, with several studies reporting no significant relation between these variables (Charman et al. 2003a; Mundy et al. 1990) but other studies reporting positive findings (Charman et al. 2005; Thurm et al. 2007). As noted by Thurm et al. (2007), there appears to be a complex relation between nonverbal cognition and language across different developmental time points. They reported that nonverbal cognitive abilities at 2 years of age was the strongest predictor of language skills at 5 years, but that language ability (rather than nonverbal cognition) at 3 years was a significant predictor of later language. This finding appeared to be due to the fact that the language scores at 2 years were less stable than nonverbal cognitive scores but by 3 years the language scores were more stable and thus better predicted later language performance.

Current findings revealed that play was a significant predictor of composite receptive language and composite expressive language for the Autism group, but was not a significant predictor of language performance for the PDD-NOS or DD groups. In the present study, this variable was comprised of functional play with objects as well as imaginary play. Several previous studies have reported that play was a significant predictor of language outcomes in ASD during early childhood and adolescence (Sigman and McGovern 2005; Smith et al. 2007; Toth et al. 2006).

In the present study, joint attention (involving a composite measure of IJA and RJA) was a significant predictor of composite receptive and composite expressive language for the PDD-NOS group. Joint attention was also a significant predictor of composite receptive language for the DD group. Contrary to expectations, joint attention was not a significant predictor of composite language scores for the Autism group. Findings from an investigation by Dawson et al. (2004) revealed that joint attention was the best predictor (among predictors of social attention) of concurrent language ability in 3- to 4-year-old children with ASD. Similarly, Toth et al. (2006) reported that IJA, along with immediate imitation, was strongly associated with language ability at this same age level for preschoolers with ASD. Luyster et al. (2008) found that RJA was a significant predictor of concurrent receptive (but not expressive) language ability in toddlers on the autism spectrum, while Paul et al. (2008) reported that RJA was significantly related to expressive language outcomes in preschool children with ASD.

Frequency of vocalization was a significant predictor for the Autism group for both composite receptive and composite expressive language, but was not a significant predictor for the other groups. Preliminary findings in an ongoing investigation by Ellis Weismer and colleagues suggest that frequency of vocalization is predictive of later language and communication outcomes in non-spectrum late talkers, particularly for productive language. The association between frequency of vocalization and later expressive language abilities in late talkers is hypothesized to be related to underlying speech production (articulation) skills. However, in the present case of toddlers with autism, we speculate that frequency of vocalization has less to do with speech production skills (especially in light of its relation to receptive language abilities as well as expressive language) and more to do with social engagement and interaction. That is, it may be the case that those toddlers with ASD who vocalize more frequently are also more likely to have higher levels of social engagement, leading to better language outcomes.

Some of the current findings were not consistent with previous research. Unlike prior studies that have found various types of imitation skills to predict language abilities in children with ASD (Smith et al. 2007; Luyster et al. 2008; Thurm et al. 2007; Toth et al. 2006), imitation—as indexed by the ADOS—was not a concurrent predictor of composite language scores for toddlers on the autism spectrum in the current study. Imitation was a significant predictor, however, of composite receptive and composite expressive language performance by the DD group. Additionally, gesture was not a significant concurrent predictor of composite language scores for any of the groups in the present investigation. This finding conflicts with prior research that has found early gesture use—as measured by the CDI—to be associated with language abilities in ASD (Mitchell et al. 2006; Luyster et al. 2008). It is possible that the lack of significant effect was due to the relatively limited use of gestures as measured by the ADOS at this early developmental level, which resulted in a restricted range of scores.

Individual Variation

In the current study the majority of toddlers displayed the group pattern of significant language delay. However, there were individual toddlers in the ASD group and the PDD-NOS group (as well as the DD group) who exhibited normal range language abilities. Specifically, 3% of toddlers with autism, 8% with PDD-NOS and 12% with DD scored within normal range in terms of early language development. It is noteworthy that each of the toddlers on the autism spectrum who displayed normal range language skills also had nonverbal cognitive abilities that were within or above normal range; however, having nonverbal cognitive skills that were commensurate with age level did not ensure normal range language. Normal or above normal range language skills have been described previously for school age children with ASD (Kjelgaard and Tager-Flusberg 2001; Tager-Flusberg and Joseph 2003), and two independent samples of toddlers on the autism spectrum (Ellis Weismer et al. 2007, 2008). In their study of preschool children with ASD, Charman et al. (2003b) reported that some individual children achieved normal range language scores relative to their CA and nonverbal mental age. However, in that study it was not possible to determine the exact number of children whose scores fell within normal range because the measure that was used, the CDI Infant Form, only has normative data for typically developing children between the ages of 8 and 16 months and the CA of most of the sample exceeded this age range. The finding that some young children with ASD display age level language abilities on the CDI was replicated by Luyster et al. (2007).

On the surface, the claim that some toddlers on the autism spectrum do not have language delays or impairments might appear to be inconsistent with DSM-IV criteria. However, it is important to distinguish between “language” and “communication” development, that is, between core semantic and syntactic linguistic functioning (vocabulary and grammar) and other aspects of language use and nonverbal communication. The fact that a minority of toddlers had productive, non-imitative language use that met age-level expectations, does not imply typical pragmatic language abilities or social communication skills. The measures used in the current study primarily tap vocabulary and grammatical skills but do not provide an indication of how toddlers use their language within social contexts.

Clinical Implications

The findings from the present study have clinical relevance with respect to assessment and intervention of early language abilities of toddlers with ASD. The assessment results are encouraging in that there is consistency across various assessment measures of early language and communication skills. Considerable convergence is seen across a general developmental scale and a specific language test as well as across a parent report measure and direct assessment measures. This means that psychologists or speech-language pathologists who are evaluating language development in this population are likely to obtain a converging picture of a child’s abilities through the use of these measures. A recent report was published by a working group of autism researchers assembled by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (Tager-Flusberg et al. 2009) which recommended replacing the notion of ‘functional speech’ with a developmental framework of language phases between 12 and 48 months. This group recommended that multiple measures be used to establish a child’s language level, including standardized tests, parent report, and natural language samples. The current evidence of significant positive correlations across different language measures (as well as prior evidence from Akshoomoff (2006), and Luyster et al. 2008) suggests that professionals have a number of viable options when selecting measures of early language development for children with ASD and that these measures will likely yield consistent results.

In terms of language intervention, these findings indicate that most toddlers with ASD will have significant delays in vocabulary and grammatical abilities relative to their chronological age and their nonverbal cognitive level. Therefore, treatment focused specifically on stimulating these aspects of language development will likely be needed. According to the current study, there are a small percentage of toddlers on the autism spectrum who exhibit normal range vocabulary and early grammatical abilities. These toddlers may nevertheless benefit from intervention targeting social communication skills or pragmatic aspects of language usage, which are commonly a challenge for toddlers with ASD given their significant social impairments. Another important implication of the results from this investigation of early language development pertains to the profile of language comprehension-production abilities that was observed. As a group, toddlers on the autism spectrum exhibit substantial delays in language comprehension, which can equal or exceed their delays in expressive language performance. This pattern is unlike that of children with Specific Language Impairment or Down syndrome who tend to have more marked deficits in language production than comprehension (Laws and Bishop 2003). Intervention programs for toddlers with ASD should include emphasis on facilitating their ability to understand language as well working on their expressive language and communication skills.

Limitations and Future Directions

As noted in the introduction, the aim of this investigation was to address a number of limitations of prior studies of early language development in children on the autism spectrum and to further our understanding of toddlers’ language abilities. Of course, the current study, as is the case with all investigations, has certain limitations of its own. Although we examined cross-population comparisons involving ASD and DD groups, there are other populations with language delay (such as late talkers without autistic features or general DD) that might be informative to consider relative to similarities or differences in early developmental patterns. Further, because a few of the toddlers diagnosed with DD in the present study had been referred for evaluation for possible autism it may be the case that they are not entirely representative of the larger DD population. Our focus on a narrowly circumscribed developmental range (2- to 3-year-olds) in the current investigation was intentional. However, this aspect of the investigation might alternatively be viewed as a limitation in that further large-scale study is also needed of other age ranges within the early development period. Additional studies are needed that follow infants and toddlers longitudinally in order to gain a comprehensive picture of the developmental trajectory of early language acquisition on the autism spectrum.

References

Akshoomoff, N. (2006). Use of the mullen scales of early learning for the assessment of young children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Neuropsychology, 12, 269–277.

Beeghly, M. (2006). Translational research on early language development: Current challenges and future directions. Development and Psychopathology, 18, 737–757.

Bishop, D. V. M., & Norbury, C. (2002). Exploring the borderlands of autistic disorder and specific language impairment: A study using standardised diagnostic instruments. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43, 917–929.

Charman, T., Baron-Cohen, S., Swettenham, J., Baird, G., Drew, A., & Cox, A. (2003a). Predicting language outcome in infants with autism and pervasive developmental disorder. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 38, 265–285.

Charman, T., Drew, A., Baird, C., & Baird, G. (2003b). Measuring early language development in preschool children with autism spectrum disorder using the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory (infant form). Journal of Child Language, 30, 213–236.

Charman, T., Taylor, E., Drew, A., Cockerill, H., Brown, J., & Baird, G. (2005). Outcome at 7 years of children diagnosed with autism at age 2: Predictive validity of assessments conducted at 2 and 3 years of age and pattern of symptom change over time. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 500–513.

Dawson, G., Toth, K., Abbott, R., Osterling, J., Munson, J., Estes, A., et al. (2004). Early social attention impairments in autism: Social orienting, joint attention, and attention to distress. Developmental Psychology, 40, 271–283.

DiLavore, P., Lord, C., & Rutter, M. (1995). Pre-linguistic autism diagnostic observation schedule (PLADOS). Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25, 355–379.

Eaves, L., & Ho, H. (2004). The very early identification of autism: Outcome to age 4½ -5. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34, 367–378.

Ellis Weismer, S., Gernsbacher, M. A., Roos, E., Karasinski, C., & Hollar, C. (2008). Understanding comprehension in toddlers on the autism spectrum. Poster presented at the symposium for research on child language disorders. Madison, WI.

Ellis Weismer, S., Roos, E., Gernsbacher, M. A., Geye, H., O'Shea, M., Eisenband, L., et al. (2007). Early language abilities of toddlers on the autism spectrum. Poster presented at the symposium for research on child language disorders. Madison, WI.

Gernsbacher, M., Geye, H., & Ellis Weismer, S. (2005). The role of language and communication impairments within autism. In P. Fletcher & J. Miller (Eds.), Developmental theory and language development (pp. 73–199). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Heilmann, J., Ellis Weismer, S., Evans, J., & Hollar, C. (2005). Utility of the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory in identifying language abilities of late-talking and typically developing toddlers. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14, 40–51.

Hendrick, D., Prather, E., & Tobin, A. (1984). Sequenced inventory of communication development (Revised ed.). Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press.

Hudry, K., Leadbitter, K., Temple, K., Slonims, V., McConachie, H., Aldred, et al. (2008). Agreement across measures of language and communication in preschoolers with core autism. Poster presented at the 7th annual international meeting for autism research (IMFAR). London, UK.

Kjelgaard, M., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (2001). An investigation of language impairment in autism: Implications for genetic sub-groups. Language and Cognitive Processes, 16, 287–308.

Laws, G., & Bishop, D. V. M. (2003). A comparison of language abilities in adolescents with down syndrome and children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 46, 1324–1339.

Lord, C., Risi, S., & Pickles, A. (2004). Trajectory of language development in autistic spectrum disorders. In M. Rice & S. Warren (Eds.), Developmental language disorders: From phenotypes to etiologies (pp. 1–38). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., DiLavore, P., & Risi, S. (1999). Autism diagnostic observation schedule. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services.

Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism diagnostic interview-revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 659–685.

Luyster, R., Gotham, K., Guthrie, W., Coffing, M., Petrak, R., DiLavore, P., et al. (2009). The autism diagnostic observation schedule–toddler module: A new module of a standardized diagnostic measure for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 1305–1320.

Luyster, R., Kadlec, M., Carter, A., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (2008). Language assessment and development in toddlers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1426–1438.

Luyster, R., Lopez, K., & Lord, C. (2007). Characterizing communicative development in children referred for autism spectrum disorders using the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (CDI). Journal of Child Language, 34, 623–654.

McDuffie, A., Yoder, P., & Stone, W. (2006). Fast-mapping in young children with autism spectrum disorders. First Language, 26, 421–438.

Mitchell, S., Brian, J., Zwaigenbaum, L., Roberts, W., Szatmari, P., Smith, I., et al. (2006). Early language and communication development of infants later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 27, S69–S78.

Mullen, E. M. (1989/1995). Mullen scales of early learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Mundy, P., Sigman, M., & Kasari, C. (1990). A longitudinal study of joint attention and language development in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20, 115–128.

Paul, R., Chawarska, K., Chicchetti, D., & Volkmar, F. (2008). Language outcomes of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: A two year follow-up. Autism, 1, 99–107.

Rice, M., & Warren, S. (2004). Developmental language disorders: From phenotypes to etiologies. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Rice, M., Warren, S., & Betz, S. (2005). Language symptoms of developmental language disorders: An overview of autism, down syndrome, fragile X, specific language impairment, and Williams syndrome. Applied Psycholinguistics, 26, 7–27.

Shulman, C., & Guberman, A. (2007). Acquisition of verb meaning through syntactic cues: A comparison of children with autism, children with specific language impairment (SLI) and children with typical language development (TLD). Journal of Child Language, 34, 411–423.

Sigman, M., & McGovern, C. (2005). Improvement in cognitive and language skills from preschool to adolescence in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 15–23.

Smith, V., Mirenda, P., & Zaidman-Zait, A. (2007). Predictors of expressive vocabulary growth in children with autism. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 149–160.

Sparrow, S., Balla, D., & Cicchetti, D. V. (1984). Vineland adaptive behavior scales. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Sparrow, S., Chicchetti, D. V., & Balla, D. (2005). Vineland-II adaptive behavior scales. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service.

Swensen, L., Kelley, E., Fein, D., & Naigles, L. (2007). Processes of language acquisition in children with autism: Evidence from preferential looking. Child Development, 78, 542–557.

Tager-Flusberg, H., & Joseph, R. (2003). Identifying neurocognitive phenotypes in autism. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences, 358, 303–314.

Tager-Flusberg, H., Rogers, S., Cooper, J., Landa, R., Lord, C., Paul, R., et al. (2009). Defining spoken language benchmarks and selecting measures of expressive language development for young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 52, 643–652.

Thal, D., DesJardin, J., & Eisenberg, L. (2007). Validity of the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories for measuring language abilities in children with cochlear implants. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16, 54–64.

Thurm, A., Lord, C., Lee, L., & Newschaffer, C. (2007). Predictors of language acquisition in preschool children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1721–1734.

Toth, K., Munson, J., Meltzoff, A., & Dawson, G. (2006). Early predictors of communication development in young children with autism spectrum disorder: Joint attention, imitation, and toy play. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 993–1005.

Acknowledgments

These data were collected with support from NIMH R01 MH81873 and Autism Speaks. Additionally, partial support for preparation of this article was provided by NIDCD R01DC007223 and the NICHD P30 HD03352. We also wish to express our sincere thanks to the children and parents who participated in this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ellis Weismer, S., Lord, C. & Esler, A. Early Language Patterns of Toddlers on the Autism Spectrum Compared to Toddlers with Developmental Delay. J Autism Dev Disord 40, 1259–1273 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0983-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0983-1