Abstract

This study tested the theoretical assertion that anger and sympathy would be differentially associated with “hot-blooded” reactive and “cold-blooded” proactive aggression in an ethnically diverse community sample of 4- and 8-year-olds from Canada (N = 300; n = 150 in each age group; 50% female). We conducted structured interviews with children to elicit their self-reported anger in response to social conflicts (anger reactivity), ability to effectively manage feelings of frustration (anger regulation), and the degree to which they felt concern for others in need (sympathy). Caregivers completed questionnaires assessing the degree to which children engaged in reactive and proactive overt aggression. Across ages, dysregulated anger was more strongly associated with reactive aggression, whereas lower sympathy was more strongly linked to proactive aggression. Anger reactivity did not predict children’s aggressive behavior, with one exception: lower anger reactivity in 8-year-old males was associated with higher levels of proactive aggression. These findings support the hypotheses that anger and sympathy are differentially involved in reactive and proactive aggression, and that these distinct affective correlates are evident by the preschool years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Children’s capacities to appropriately experience and regulate their emotions in social interactions are essential for healthy behavioral development (Eisenberg 2000; Malti and Noam 2016). Emotion processes involving anger and sympathy, in particular, have long played important roles in developmental theories of aggression (Hay 2017; Lochman et al. 2010; Malti et al. 2018; Miller and Eisenberg 1988). Contemporary researchers have posited that anger and sympathy may uniquely contribute to distinct types of aggressive behavior. Specifically, dysregulated anger may be more strongly linked to the development of reactive or “hot-blooded” aggression in response to threat/provocation, whereas a dearth of other-oriented concern may be more indicative of proactive or “cold-blooded” aggression in the pursuit of goals or resources (Arsenio and Lemerise 2001, 2004; Hubbard et al. 2010b).

To date, however, few studies have incorporated assessments of both anger and sympathy to compare the relative strength of their associations with different types of aggressive behavior. Moreover, relatively little is known about the distinct affective correlates of reactive and proactive aggression prior to middle childhood. Examining these processes in early childhood is necessary to develop effective interventions targeting the unique emotional factors associated with different aggressive subtypes before long-term problematic behavioral trajectories become canalized (Malti et al. 2016; Shaw and Taraban 2017; Vitaro et al. 2006). To address these gaps in the literature, we examined whether 4- and 8-year-olds’ self-reported intensity of anger arousal in response to social conflict, ability to regulate anger, and sympathy for others in need were differentially associated with caregiver ratings of reactive and proactive overt aggression.

Anger and Aggression

Anger is a negatively valenced emotional state in response to perceived environmental threats and goal blocking that functions as a signal to warn or intimidate others (Lochman et al. 2010). Although anger can be adaptive when appropriately matched to the immediate social context (e.g., when directly threatened), children who have difficulty regulating and controlling the subjective experience and outward expression of anger show heightened levels of aggression from early childhood onward (Lemerise and Harper 2010; Lochman et al. 2010). Infants as young as 6 months of age display verbal and facial signs of anger while engaging in overtly aggressive acts such as hitting and forcefully taking toys from others (Hay 2017). Beyond infancy, children who frequently engage in aggressive interactions with peers are more prone to intense anger and frustration, and possess less adaptive strategies for coping with these emotions than less aggressive youth (Arsenio et al. 2000; Musher-Eizenman et al. 2004; Schultz et al. 2004; Zeman et al. 2002). As such, intense and dysregulated anger is conceptualized as a motivating force underlying many (but not all) aggressive interactions.

Sympathy and Aggression

Sympathy (i.e., empathic concern) is an affective response to another’s emotional state or condition. Whereas empathy entails feeling the same or a similar emotion to what others are feeling (e.g., sadness when others are sad), sympathy specifically refers to the experience of concern or sorrow for others in need (Eisenberg et al. 2014; Malti et al. 2018). Although sympathy can arise from empathy, it may also stem from a cognitive awareness of another’s state or condition (Eisenberg et al. 2014). Distinguishing sympathy from empathy is critical because unregulated empathy can lead to an aversive, self-focused emotional state of personal distress (Eisenberg et al. 2014). In contrast, sympathy directs children’s attention outward to the consequences of actions for others’ rights and wellbeing. As such, experiencing sympathy—but not empathy or personal distress—in anticipation of or in response to another’s suffering is thought to inhibit children’s tendency to engage in aggressive actions that harm others (Eisner and Malti 2015; Zuffianò et al. 2018).

Despite this conceptualization of sympathy as a protective factor, researchers have frequently utilized measures of empathy-related responding that do not differentiate sympathy from empathy and personal distress (Eisenberg et al. 2014; Miller and Eisenberg 1988). As such, empirical support for the inhibiting role of sympathy on aggression is mixed. Whereas past studies have documented negative associations with antisocial behavior in clinical (e.g., conduct-disordered youth; Cohen and Strayer 1996) and community samples of children and adolescents (Strayer and Roberts 2004; van Norden et al. 2015; Zuffianò et al. 2018), others have failed to find an association (see Lovett and Sheffield 2007) and there is some evidence that empathy-related responding may be positively linked to aggression in early childhood (Gill and Calkins 2003).

An additional reason for these conflicting findings may be that past research has often focused on general antisocial or conduct problems (e.g., externalizing symptoms, delinquency) rather than aggression involving intentional harm towards others (Tremblay 2010). Children bereft of sympathy may be more likely to harm others in certain situations (e.g., when doing so leads to rewards) while nevertheless demonstrating the ability to act in accordance with social norms in other contexts. As discussed below, the association between other-oriented concern and aggression likely varies depending on the type of aggressive behavior in question.

Reactive and Proactive Aggression

Whereas prior research has focused on the roles of anger and sympathy in the development of children’s overt aggression, less attention has centered on whether these affective processes are differentially associated with reactive and proactive aggression. Reactive or hostile aggression reflects a “hot-blooded” response to perceived threat or goal blocking in the environment. It is frequently conceptualized as involving intense feelings of anger and frustration, and functions as an impulsive act of defense or retaliation against provocation. Proactive or instrumental aggression, on the other hand, entails the “cold-blooded” use of coercion or harm in the pursuit of goals, rewards, or power (Hubbard et al. 2010a; Little et al. 2003b; Vitaro et al. 2006).

Although often overlapping, reactive and proactive aggression represent distinct behaviors that show different patterns of association with children’s psychosocial functioning (Card and Little 2006; Hubbard et al. 2010a). Compared to proactive aggression, reactive aggression is more closely linked to past experiences of peer rejection and victimization (Dodge et al. 1997), externalizing problems (e.g., hyperactivity; Little et al. 2003b), and the tendency to perceive ambiguous social situations as hostile and threatening (hostile attribution bias; Crick and Dodge 1996). Proactive aggression, by contrast, is not consistently associated with poor psychosocial functioning (see Card and Little 2006) and has been positively linked to some indicators of social competence (e.g., popularity, perspective-taking; Poulin and Boivin 2000; Renouf et al. 2010). These findings suggest that children who proactively aggress do not always fit the “deficit” stereotype associated with antisocial behavior in general (Sutton et al. 1999). Nevertheless, proactive agggression constitutes a core feature of bullying perpetration (i.e., deliberate and repeated use of harm against a less powerful victim) and is more likely than reactive aggression to involve the presence of callous-unemotional (CU) tendencies (Marsee and Frick 2012; Zych et al. 2016). Proactive aggression may also be uniquely predictive of interpersonal violence in adolescence (Brengden et al. 2001). Given the conceptual distinction between the subtypes and their differential associations with children’s functioning, researchers have posited that unique emotion processes may contribute to reactive and proactive aggression (Arsenio and Lemerise 2001, 2004; Hubbard et al. 2010b; Vitaro et al. 2006).

Anger in Reactive and Proactive Aggression

Experiencing intense and dysregulated anger is hypothesized to increase the likelihood that children will reactively aggress in response to perceived provocation or threats in the environment. Consistent with this notion, research conducted in late childhood and adolescence utilizing self-, teacher-, and caregiver-reports of anger have found that reactively aggressive youth are prone to strong feelings of frustration and have difficulty regulating their anger once aroused (Little et al. 2003a; McAuliffe et al. 2007; Orobio de Castro et al. 2005). A longitudinal study by Rohlf et al. (2017) demonstrated that observed anger dysregulation during middle childhood was directly associated with higher levels of reactive (but not proactive) aggression concurrently and indirectly linked to relative increases in reactive aggression 1 year later by eliciting victimization from peers.

The conceptualization of proactive aggression as “cold-blooded” implies that children utilizing aggressive tactics in the pursuit of rewards are less prone to dysregulated anger. Whereas some studies have documented autonomic under-arousal in proactively aggressive youth (Moore et al. 2018; Raine et al. 2014), others have produced mixed support for this hypothesis. For instance, Hubbard and colleagues (Hubbard et al. 2002) engaged 8-year-olds in a lab-based competitive task designed such that children lost a game (and prizes) to a confederate who cheated. Greater physiological arousal—measured via skin conductance reactivity—and observed behavioral expressions of frustration during the task were associated with higher levels of teacher-reported reactive (but not proactive) aggression. Nonetheless, children higher in proactive (but not reactive) aggression showed increases in self-reported anger over the duration of the competitive task. Similar conflicting findings emerged in a longitudinal study by Ostrov et al. (2013), which demonstrated that teacher-reported anger at 3 years of age predicted higher levels of observed reactive and proactive physical aggression 4 months later, whereas greater emotion regulation skills were weakly but positively associated with greater proactive (but not reactive) aggression over time.

One potential explanation for these conflicting results is that experiencing intense anger in response to social conflicts may be indicative of both aggressive subtypes, yet children who engage in proactive aggression may be more adept than reactively aggressive youth at regulating their emotional responses (Hubbard et al. 2010b). Indeed, reactivity (the intensity of affect) and regulation (the capacity to modulate an affective response) constitute related but distinct emotion processes (Cole et al. 2004; Eisenberg 2000). Although aggressively responding to threat has clear adaptive value, the ability to effectively manage the experience and expression of anger allows children to attend to relevant social information (e.g., others’ benign intent) and enact behavioral strategies that are appropriate in a given social context (Lemerise and Harper 2010; Lochman et al. 2010). To date, few studies have examined both anger reactivity and regulation to disentangle their distinct associations with reactive and proactive aggression (but see Hubbard et al. 2002; Moore et al. 2018). We therefore included assessments of both anger reactivity and regulation in the present study.

Sympathy in Reactive and Proactive Aggression

Children who proactively harm others for instrumental gain are more likely than reactively aggressive and non-aggressive children to believe that aggression is an effective means of achieving goals and obtaining positive rewards (Arsenio et al. 2009; Crick and Dodge 1996; Dodge et al. 1997). As Arsenio and Lemerise (2001) note, however, expecting aggression to “get you what you want” does not explain why a child would consider harming others to be an acceptable course of action. To address this disconnect, developmental researchers have posited that a limited capacity to experience sympathy may be an important factor underlying proactive aggression (Arsenio and Lemerise 2001, 2004). Indeed, a dearth of other-oriented concern constitutes a defining characteristic of CU, which has been linked to proactive aggression in community and clinical samples (see Frick et al. 2014; Marsee and Frick 2010). The degree to which sympathy accounts for this relation remains unclear, however, given that CU traits encompass a broad array of characteristics including a general poverty of emotional expression, lack of guilt over misbehavior, low achievement motivation, and an insensitivity to punishment.

Although identifying the affective mechanisms underlying different types of aggression is essential for successful intervention (Vitaro et al. 2006), surprisingly little research has explicitly tested whether children lower in sympathy are more likely to engage in proactive versus reactive aggression. Arsenio and colleagues (Arsenio et al. 2009) interviewed low-income, primarily African American adolescents regarding hypothetical vignettes depicting characters engaged in aggressive conflicts with peers. When asked to imagine themselves as the transgressors, adolescents higher in teacher-reported proactive aggression were more likely than less aggressive youth to expect to feel positive emotions after aggressing and less likely to reference the welfare of the victims when explaining their emotions; reactive aggression was not associated with self-reported emotions or reasoning. In a more direct test of the sympathy–proactive aggression link, Peplak and Malti (2017) found that combined teacher- and peer-reports of proactive (but not reactive) aggression were uniquely associated with lower levels of teacher-reported sympathy in 5- to 10-year-olds. To clarify whether these findings could be replicated using different informants, we examined whether sympathy was more strongly associated with proactive compared to reactive aggression.

Developmental Considerations

Physical aggression peaks in frequency between 2 and 4 years of age before normatively declining across the preschool and school years (Eisner and Malti 2015); by adolescence, only a minority of chronically problematic youth continue to exhibit high levels of this behavior (Tremblay 2010). Correspondingly, children’s abilities to adaptively regulate their anger and experience sympathy for others increase from early to middle childhood (Eisenberg et al. 2014; Lemerise and Harper 2010). Moreover, programs are more effective at reducing problem behaviors and promoting empathy-related and prosocial tendencies when implemented in early childhood rather than at later ages (Ellis et al. 2016; Malti et al. 2016; Shaw and Taraban 2017). Understanding whether the distinct affective correlates of reactive and proactive aggression observed in middle childhood are also evident in early childhood is necessary to inform efforts targeting the specific emotion processes associated with each subtype. Teaching children how to adaptively cope with their anger has been effective at reducing reactive aggression (Lochman et al. 2010). In contrast, interventions specifically designed to foster children’s concern for others’ rights and wellbeing (e.g., providing opportunities for affective perspective-taking; Hubbard et al. 2010a) may be especially important for reducing proactive aggression (but see Ellis et al. 2016).

Current Study

Our central aim was to test the hypothesis that intense and dysregulated anger would be more strongly associated with reactive aggression, whereas a lack of sympathy would be more strongly linked to proactive aggression. We focused on 4- and 8-year-olds in order to clarify whether the differential affective correlates of reactive and proactive aggression evidenced stability or age-related differences. We limited our investigation to overt aggression (e.g., direct physical harm and verbal attacks) because it represents the most common form of childhood aggression and is a robust predictor of later maladjustment (Eisner and Malti 2015).

In line with contemporary theorizing and findings from past research, we expected that children reporting more intense anger in response to hypothetical acts of victimization and less effective anger regulation strategies would evidence higher levels of reactive aggression. In contrast, we hypothesized that children who expressed less sympathy for others would evidence higher levels of proactive aggression. Given the mixed pattern of findings regarding anger and proactive aggression (Hubbard et al. 2002; Ostrov et al. 2013), it was unclear whether anger reactivity and regulation would be associated with this subtype of aggression.

Although overt aggression normatively declines from early to middle childhood (Eisner and Malti 2015), little research has examined whether the emotional correlates of reactive and proactive aggression differ in younger and older children. Similarly, whereas males are more likely to engage in overt aggression than females, the extent to which anger and sympathy show different patterns of association with each subtype as a function of gender is unknown. We therefore compared the strength of these effects across age and gender but did not have specific hypotheses. We controlled for children’s verbal ability in all analyses given its demonstrated associations with aggression (Eisner and Malti 2015), anger (Giesbrechta et al. 2010), and sympathy (Malti et al. 2012).

Method

Sample

The present sample consisted of 300 four- and 8-year-olds (n = 150 in each age group; 50% female) and their primary caregivers (84% mothers; 98% biological parents) drawn from the first wave of an ongoing longitudinal study of children’s social-emotional development and aggression. Participants were recruited from a pre-existing database of families from Mississauga, Canada. Over 93% of caregivers reported being married or in a domestic partnership. Caregivers’ self-reported highest level of education included 1% less than high school, 4% high school, 1% apprenticeship or trade school, 17% college degree, 49% bachelor’s degree, 21% master’s degree, and 3% Ph.D.; 4% chose not to answer. Reflecting Mississauga’s population (Statistics Canada 2013), the sample was ethnically diverse: 15% American, 15% South/Southeast Asian, 13% Western European, 9% East Asian, 5% Eastern European, 4% Central/South American, 3% West/Central Asian, 3% African, 1% Middle Eastern, 19% multi-ethnic, and 1% other; 11% refused/chose not to answer. Four and 8-year-olds did not differ along any demographic characteristics (ps = 0.20–0.80).

Procedure

The University of Toronto's ethics review board granted approval for the study prior to the start of data collection. Children and their caregivers attended the laboratory for a single 60- to 90-min session. Verbal assent was obtained from children and written informed consent was obtained from caregivers. Child assessments were conducted in a designated room while caregivers remained in a waiting area and completed questionnaires on a touchscreen tablet. Children were instructed on the use of all scales prior to task completion and trained undergraduate psychology research assistants conducted the sessions. At study end, caregivers were debriefed and children were gifted an age-appropriate book for their participation.

Measures

Reactive and Proactive Aggression

Caregivers rated children’s reactive and proactive aggression using 12 items (six items each) adapted from a self-report measure developed by Little et al. (2003b). The items described overt acts of verbal and physical aggression indicative of reactive (e.g., “…puts others down if upset or hurt by them/fights back when hurt by someone”) and proactive aggression (e.g., “…says mean things to others/starts fights…to get what (s)he wants”). Responses were scored on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (always). Separate principal components analyses (PCAs) with varimax rotation conducted on items within each aggression subscale revealed single factor solutions accounting for 66% of the variance in reactive (standardized loadings = 0.77–0.86) and proactive scores (standardized loadings = 0.76–0.87) for 4-year-olds, and 59% (standardized loadings = 0.69–0.81) and 60% (standardized loadings = 0.74–0.83) of the variance in reactive and proactive scores, respectively, for 8-year-olds. Items were averaged within each subscale to create composite scores representing reactive (αs = 0.89 and 0.85 for 4- and 8-year-olds, respectively) and proactive aggression (αs = 0.89 and 0.86 for 4- and 8-year-olds, respectively), with higher scores reflecting higher levels of aggression.

Anger Regulation

Children’s self-reported ability to manage their feelings of anger and frustration was assessed using the four-item Emotion Regulation Coping subscale of the Children’s Anger Management Scale (CAMS; Zeman et al. 2002). Item wording slightly differed between the 4- and 8-year-old versions: “When I’m feeling mad, I can control my anger/ When I’m feeling mad, I can control my temper”, “I stay calm when I’m mad/I stay calm and keep my cool when I’m feeling mad”, “I can stop myself from getting angry/I can stop myself from losing my temper when I’m mad”, “I calmly deal with what makes me mad/I try to calmly deal with what is making me mad”. The experimenter read each item and asked children, “Does this sound like you? Or not?” They were given the forced choice of responding “No, this does not sound like me” or “Yes, this sounds like me”. Affirmative responses were followed up by asking, “Does it really sound like you? Or sort of sound like you?” Responses for each item were coded on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not like me) to 2 (really sounds like me). A PCA revealed a single factor solution accounting for 61% (standardized loadings = 0.63–0.84) and 58% (standardized loadings = 0.71–0.80) of the variance in scores for 4- and 8-year-olds, respectively. Items were averaged to create a single composite of anger regulation (αs = 0.78 and 0.76 for 4- and 8-year-olds, respectively), with higher scores reflecting better anger regulation ability.

Anger Reactivity

Children’s anger reactivity in response to conflict was assessed via semi-structured interviews regarding six hypothetical vignettes involving social transgressions. Similar measures have been extensively used and validated to assess self-reported emotions in response to social conflicts in children as young as 4 years of age (Malti et al. 2009; Smetana et al. 1999). Children were trained to use a 3-point rating scale (see below) prior to the start of the interviews. Stories were presented to children on a computer screen, accompanied by illustrations and an audio-recorded narration of the events. The six vignettes depicted a range of everyday events experienced by young children that have negative implications for others’ physical and/or psychological wellbeing: not sharing (eating an ice cream cone that was intended for a friend and not telling them about it), stealing (taking and eating a peer’s chocolate bar without them knowing), failure to act prosocially (refusing to help a peer who asked for help learning to play an instrument), shoving (pushing someone and cutting in line to get the last lollipop from the teacher), exclusion based on school membership (excluding someone from a different school from a group painting exercise), and exclusion based on social class (refusing to let a peer share a seat on a bus because they live in a run-down house).

In line with past research (Malti et al. 2009), children were first instructed to imagine themselves as the transgressor and were asked how they would feel if they had engaged in the actions and why. As these assessments are not the focus of the present study they are not considered further. Next, using a 3-point scale depicting squares of increasing size corresponding to different levels of intensity, children were asked to rate how angry they would feel if the acts had been done to them (i.e., as the victims). Responses were coded as 1 (not strong), 2 (somewhat strong), and 3 (very strong). Although the vignettes depict different types of morally relevant situations, a PCA revealed a single factor solution in both age groups accounting for 67% (standardized loadings = 0.78–0.85) and 50% (standardized loadings = 0.66–0.79) of the variance in scores for 4- and 8-year-olds, respectively. Scores across the six stories were averaged to create a single measure of anger reactivity (αs = 0.90 and 0.80 for 4- and 8-year-olds, respectively), with higher scores reflecting more intense feelings of anger in response to the events.

Sympathy

Children’s self-reported sympathy was assessed using a five-item scale from Eisenberg et al. (1996; e.g., “I feel sorry for other children who are being teased”), which has been successfully employed in studies with children as young as 4 years of age (Ongley and Malti 2014). The experimenter read each item and asked children, “Does this sound like you? Or not?” Children were given the forced choice of responding “No, this does not sound like me” or “Yes, this sounds like me.” Affirmative responses were followed up by asking, “Does it really sound like you? Or sort of sound like you?” Responses for each item were coded on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not like me) to 2 (really sounds like me). PCAs conducted separately for each age group revealed that one item (“I feel sorry for kids who don’t have toys and clothes”) loaded onto a separate factor for 4-year-olds. One factor emerged for 8-year-olds, but the same item loaded less strongly (0.56) compared to other items (0.71–0.85). After removing this item, a revised PCA revealed a single-factor solution accounting for approximately 60% of the variance in scores for both age groups, with high standardized loadings for 4- (0.72–0.80) and 8-year-olds (0.72–0.85). Items were averaged across the four items to create a sympathy scale (αs = 0.77), with higher scores reflecting greater levels of sympathy.

Verbal Ability (Control Variable)

Children’s verbal ability was measured using the verbal subtest of the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test 2nd edition (KBIT-2; Kaufman and Kaufman 2004). Scores were calculated by subtracting each participant’s number of errors from their total correct responses (Ms = 13.89, 29.23, SDs = 4.23, 5.15, Ranges = 1–26, 16–44, for 4- and 8-year-olds, respectively). As older children demonstrated greater verbal ability than younger children (Cohen’s d = 3.66), this variable was mean-centered within each age group prior to analyses.

Missing Data

A preliminary inspection revealed a relatively small amount of missing data (range = 0%–5.70%). Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test conducted on all study variables was significant, χ2 (41, N = 300) = 62.067, p = 0.018, indicating that the pattern of missing data was associated with observed scores across the study variables. Follow-up analyses revealed that 4-year-olds were more likely than 8-year-olds to have missing data on all three emotion variables, males were more likely than females to have missing anger regulation scores, children with lower verbal ability were more likely to have missing sympathy scores, and more proactively aggressive children were more likely to have missing sympathy and anger regulation data. We therefore estimated missing data under the missing-at-random (MAR) assumption using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) with robust standard errors. The Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test was used to compare nested models when appropriate.

Data Analysis Plan

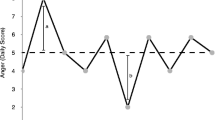

All data analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.3. We first screened for multivariate outliers using multiple indices available in the Mplus program, including the Mahalanobis distance, Cook’s D parameter estimate influence measure, loglikelihood contribution from each individual, and loglikelihood distance influence measure. We next examined mean-level differences by age group and gender across all study variables. To test our main study hypotheses, we estimated an initial path model simultaneously regressing reactive and proactive aggression onto the three emotion variables and verbal ability (see Fig. 1). This approach differs from the common practice of estimating separate models that control for the non-focal form of aggression (e.g., regressing proactive aggression onto reactive aggression and predictors; Arsenio et al. 2009). This latter method has been critiqued on the grounds that removing all of the shared variance between the two behaviors produces an artificial estimate that is difficult to interpret (Miller and Lynam 2006). A simultaneous path model also allowed us to explicitly test the proposition that different emotion processes would be more strongly associated with one form of aggression compared to the other, rather than relying exclusively on whether an effect was significantly different from zero or not. After the initial model, we employed multi-group modeling to test whether the strength of the effects varied across age group and gender (categorical variables). This was accomplished by comparing the χ2 values of models with the standardized regression parameters across the four groups (4-year-old females, 4-year-old males, 8-year-old females, 8-year-old males) constrained to equality to models with the parameters freely estimated. Separate comparisons were conducted for each path between the three emotion variables and the two aggression outcomes (six total comparisons). In the final step, we examined whether the different emotion processes were more strongly associated with reactive or proactive aggression by comparing the χ2 values of models freely estimating paths between predictors and aggression outcomes to models with each path constrained to equality. All variables were z-standardized prior to entry into the models.

Results

Outlier Screening

Two 4-year-olds (one male and one female) were identified as multivariate outliers: Mahalanobis distance = 43.54 and 28.80 (M = 7.80), Cook’s D = 0.90 and 0.77 (M = 0.14), loglikelihood contribution from each individual = −25.87 and − 21.49 (M = −10.37), and loglikelihood distance influence measure = 4 and 2 (M = 0.17), respectively. Follow-up sensitivity analyses revealed that including these two cases did not substantially influence the magnitude or direction of the regression parameters, but their inclusion did lead to increased standard error estimates and, in some instances, impacted the interpretation of statistical significance tests. The results we report below are based on analyses with these two outliers removed. Results based on the full sample are provided in the Online Supplemental Material.

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among all study variables are provided in Table 1. Detailed descriptive statistics broken down by age and gender are included in the Online Supplemental Material. We first tested multi-group models to examine age and gender differences in means across the study variables. Consistent with past findings (Eisner and Malti 2015; Lemerise and Harper 2010), compared to 4-year-olds, 8-year-olds scored higher in anger regulation, χ2 (1) = 14.58, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.32, and sympathy, χ2 (1) = 120.70, p < 0.001, d = 1.32, reported less anger in response to social conflicts, χ2 (1) = 10.06, p = 0.002, d = 0.38, and engaged in less reactive and proactive aggression, χ2s (1) = 3.78, 6.90, ps = 0.05, 0.008, ds = 0.23, 0.30, respectively. In contrast to these consistent age differences, males and females did not significantly differ along most study variables, χ2s (1) = 0.02–1.30, ps = 0.25–0.90, ds = 0.02–0.18, with the exception that caregivers rated males as more reactively aggressive than females, χ2 (1) = 8.17, p = 0.004, d = 0.33.

Direct Effects of Anger and Sympathy on Reactive and Proactive Aggression

We tested an initial path model examining the overall direct effects of anger (reactivity and regulation) and sympathy on each aggression subtype. As hypothesized, children better at regulating their anger were less reactively aggressive, β = −0.148 [95% CI: −0.278, −0.018], p = 0.026, whereas anger regulation was not significantly associated with proactive aggression, β = −0.038 [−0.158, 0.082], p = 0.54. Also consistent with theoretical expectations, lower sympathy was significantly associated with greater proactive, β = −0.143 [−0.284, −0.001], p = 0.05, but not reactive aggression, β = −0.003 [−0.159, 0.154], p = 0.97. Unexpectedly, anger reactivity was not associated with reactive, β = 0.005 [−0.127, 0.136], p = 0.94, or proactive aggression, β = −0.011 [−0.145, 0.124], p = 0.87.

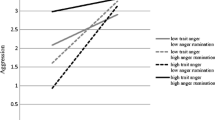

Moderation by Age and Gender

We next tested a series of models to examine whether the effects of anger and sympathy on reactive and proactive aggression were moderated by age and/or gender. Detailed statistics for each model comparison are provided in the Online Supplemental Material. The effects of anger regulation and sympathy on reactive (ps = 0.22–0.38) and proactive aggression (ps = 0.41–0.75) did not significantly differ across groups. The effect of anger reactivity on reactive aggression also did not differ (p = 0.29). Significant group differences did emerge for the association between anger reactivity and proactive aggression (p = 0.006). Follow-up analyses revealed that the effect for 8-year-old males differed from the three remaining groups (ps = 0.002–0.035). Eight-year-old males who reported less anger in response to social conflicts were rated by caregivers as higher in proactive aggression. The effect of anger reactivity on proactive aggression did not differ between 4-year-olds and 8-year-old females (ps = 0.30–0.70); anger reactivity was not associated with proactive aggression for these children. Complete parameter estimates for the final revised model allowing a unique path between anger reactivity and proactive aggression for 8-year-old males are provided in Table 2.

Comparing the Relative Strength of Anger and Sympathy on Aggression Subtypes

As a final step, we tested models examining whether the magnitude of the effects of anger and sympathy differed for reactive and proactive subtypes. As hypothesized, anger regulation was more strongly associated with reactive compared to proactive aggression, Δ χ2 (1) = 5.25, p = 0.022, whereas sympathy was a significantly stronger predictor of proactive compared to reactive aggression, Δ χ2 (1) = 31.55, p < 0.001. For 4-year-olds and 8-year-old females, the (null) effects of anger reactivity on the two subtypes of aggression did not differ in strength, Δ χ2 (1) = 1.41, p = 0.24. For 8-year-old males, however, the negative effect of anger reactivity on proactive aggression was significantly stronger than the corresponding path to reactive aggression, Δ χ2 (1) = 7.00, p = 0.008.

Discussion

Anger and sympathy have long played central roles in developmental theories of aggression (Hay 2017; Miller and Eisenberg 1988). The present study contributed new knowledge to this theorizing by simultaneously examining whether anger reactivity, anger regulation, and sympathy demonstrated distinct patterns of association with two subtypes of overt aggression—“hot-blooded” reactive and “cold-blooded” proactive aggression—in a large, ethnically diverse community sample of Canadian 4- and 8-year-old children. In support of a differential correlate hypothesis, we found that reactive aggression was more strongly associated with dysregulated anger, whereas lower sympathy was more strongly linked to proactive aggression. These results illustrate the utility of distinguishing between different types of emotion processes to generate novel, in-depth information on the heterogeneous motives underlying aggression in early and middle childhood.

Anger over-arousal constitutes a defining feature of reactive aggression, whereas proactive aggression is conceptualized as a more deliberate and controlled behavioral expression (Crick and Dodge 1996; Hubbard et al. 2010a). Consonant with this view, anger dysregulation was more strongly associated with caregiver-reported reactive than proactive aggression. Interestingly, reactively aggressive children did not report feeling more intense anger as victims of social conflict than other youth. Anger is commonly linked to poor mental health outcomes, but it is also adaptive in certain social contexts (e.g., when threatened; Lochman et al. 2010) and motivates prosocial behaviors aimed at rectifying perceived injustices (Malti et al. 2018). Problems arise, however, when children have difficulty controlling their frustration once the immediate threat has subsided or during social encounters where threat cues are ambiguous or imagined. Although past studies have also found null associations between anger regulation and proactive aggression (Little et al. 2003a, b; Rohlf et al. 2017), demonstrating that this effect was significantly weaker than for reactive aggression provides confirmatory evidence that proactive aggression is not primarily driven by emotion regulation difficulties (for experimental evidence, see Phillips and Lochman 2003).

In support of Arsenio and Lemerise’s (2001, 2004) claim, and extending Peplak and Malti’s (2017) recent findings using different informants, lower child-reported sympathy was uniquely—and more strongly—associated with caregiver ratings of proactive compared to reactive aggression. Disruptive, delinquent, and impulsive behaviors are distinct from self-serving harm and coercion enacted against others (Hawley 2014; Little et al. 2003a, b; Tremblay 2010). Theorists have postulated that the inconsistent link between empathy-related responding and conduct problems found in past research stems in part from a failure to adequately differentiate regard for others’ wellbeing (sympathy or empathic concern) from the general capacity to share the affective experience of others (empathy; Eisenberg et al. 2014; Lovett and Sheffield 2007; Miller and Eisenberg 1988). Our results illustrate the utility of attending to the type and nature of antisocial behavior under investigation as well. Knowing that a child acts aggressively towards others provides little insight into the motivations driving their behavior. Although children who harm others to accomplish instrumental goals often do not fit the “deficit” profile commonly observed in youth exhibiting severe conduct problems (Card and Little 2006; Hawley 2014; Sutton et al. 1999), our findings align with recent studies indicating that proactive aggression is uniquely characterized by reduced sympathy for others (Arsenio et al. 2009; Peplak and Malti 2017).

Our final aim was to examine whether the relations between anger and sympathy with aggression differed between early and middle childhood. Consistent with past studies (Eisner and Malti 2015; Lemerise and Harper 2010), we found mean level differences between younger and older children across all of the study variables. Interestingly, the unique associations between anger regulation and reactive aggression, and sympathy and proactive aggression, did not differ by age. This suggests that the distinct affective correlates of each aggressive subtype may already be evident by the preschool years. As overall levels of overt aggression peak between 2 to 4 years of age (Tremblay 2010), studies conducted at earlier ages are needed to determine precisely when these associations emerge in development.

Anger reactivity was the one exception to this age-related pattern: higher proactive aggression was associated with lower levels of self-reported anger in 8-year-old males only. Although this finding was unexpected, it is consistent with past research linking proactive aggression to the presence of CU tendencies involving a dearth of emotional reactivity (Marsee and Frick 2012). We drew from a community sample of 4- and 8-year-olds, whereas much of the CU literature has focused on samples of older children and adolescents (Frick et al. 2014). As such, one explanation for this finding is that, as overt aggression declines in frequency with age, children who continue to engage in overt proactive aggression beyond the preschool years may represent a subset of youth with severe conduct problems and high CU tendencies. Children who possess little regard for others, but who do not exhibit broad impairments in their general levels of affective arousal (particularly anger), may desist in the use of physical harm in favor of more subtle and indirect aggressive tactics at later ages. That this effect only emerged for males could reflect the finding that physical aggression is less socially acceptable and gender-typical for females compared to males during middle childhood (Ostrov and Godleski 2010). Even among girls who are high in CU traits, an awareness of gender-specific social roles and expectations may lead females to develop non-physically aggressive strategies at earlier ages than males (also see Tremblay 2010).

The differential effects observed in the present study call attention to the need for tailored intervention strategies targeting the unique affective correlates of reactive and proactive aggression (Malti et al. 2016; Vitaro et al. 2006). Given that aggressive children often engage in both types of behavior (Hubbard et al. 2010a), multi-faceted treatment packages that simultaneously address the distinct emotion processes underlying reactive and proactive aggression are likely to prove most beneficial. Anger regulation training successfully lowers the frequency and severity of reactive aggression (Lochman et al. 2010), whereas promoting children’s concern for the consequences of their actions for others (e.g., through inductive discipline or perspective-taking training) may be more effective at curbing proactive aggression (Hubbard et al. 2010a). Although school-based programs aimed at fostering prosocial skills have been shown to reduce conduct problems in early and middle childhood (Malti et al. 2016), the degree to which these effects are specific to proactive aggression remains unknown. Identifying strategies to prevent or reduce proactive aggression during the childhood years is particularly important in light of research indicating that similar school-based programs have little impact on bullying perpetration when implemented in adolescence (Ellis et al. 2016).

Limitations and Future Directions

This study provided novel insights into the emotion processes implicated in reactive and proactive aggression, but several limitations need to be noted. First, the cross-sectional design precludes us from drawing causal conclusions regarding the influence of emotions on aggression. Indeed, it is likely that children’s aggressive peer interactions also contribute to their emotional development. For instance, repeatedly experiencing positive outcomes (e.g., resources, social influence) through the use of harm and coercion with peers may serve to dampen children’s affective concern for others’ wellbeing over time. Relatedly, as we focused on overt aggression, it is unclear whether similar findings would emerge for relational forms of aggression (Ostrov and Godleski 2010). Examining changes in the links between emotion processes and distinct forms and functions of aggression from early to middle childhood represents a direction for future study.

In line with past studies (Card and Little 2006), ratings of reactive and proactive aggression were highly correlated. Path analyses allowed us to examine the unique effects of anger and sympathy on both types of aggression simultaneously. In addition, using different informants to assess emotions and aggression reduced the potential for shared method effects. Nevertheless, researchers have long noted the limitations associated with adult-report questionnaires differentiating between reactive and proactive functions (Hubbard et al. 2010b; Little et al. 2003a, b). Additional research utilizing other informants (e.g., peers) and methods (e.g., observational, experimental) will strengthen the validity of our findings. Similarly, observational measures of children’s anger and sympathy (Eisenberg et al. 2014; Rohlf et al. 2017) are necessary to examine these constructs at earlier ages than studied here.

As this study was conducted with a community sample, caution should be employed when generalizing these findings to populations with clinically elevated conduct problems. By definition, children and adolescents exhibiting severe behavioral issues have difficulty interacting with peers and successfully navigating social interactions. For these youth, proactive aggression may be less skillful and adaptive and more impulsive and disruptive to their social functioning compared to typically developing youth (also see Hawley 2014). As such, anger dysregulation and dampened other-oriented concern may not differentially predict reactive and proactive functions in these populations.

One final issue we did not address in the present study concerns the potential influence of parents. Numerous studies have documented how responsive and harsh parenting contribute to children’s anger regulation abilities, sympathy, and aggression (Eisenberg et al. 2014; Eisner and Malti 2015; Lemerise and Harper 2010). Theorists have also speculated that reactive and proactive aggression may stem from distinct types of family experiences (Brengden et al. 2001; Vitaro et al. 2006). The pathways by which distinct parenting practices may contribute to different types of aggression through their effects on children’s affective functioning have thus far received scant attention (Hubbard et al. 2010a). As parent-training programs are a key component of successful childhood interventions for reducing antisocial behavior (Shaw and Taraban 2017), identifying the unique family factors associated with reactive and proactive aggression is a critical next step for future research.

The present investigation provided novel insights regarding the affective correlates of aggression in young children. Simultaneously assessing distinct emotion processes and behaviors from multiple informants allowed us to explicitly test the theoretical assertion that anger and sympathy are differentially implicated in reactive and proactive aggression. We also demonstrated, for the first time, that these links are evident as early as the preschool years. Taking into account how different emotions contribute to diverse forms of social behavior and whether these processes show stability or change from early to middle childhood will foster a greater understanding of the emergence and perpetuation of aggression.

References

Arsenio, W., & Lemerise, E. (2001). Varieties of childhood bullying: Values, emotion processes, and social competence. Social Development, 10, 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00148.

Arsenio, W., & Lemerise, E. (2004). Aggression and moral development: Integrating social information processing and moral domain models. Child Development, 75, 987–1002. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00720.

Arsenio, W., Cooper, S., & Lover, A. (2000). Affective predictors of preschoolers’ aggression and peer acceptance: Direct and indirect effects. Developmental Psychology, 36, 438–448. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.36.4.438.

Arsenio, W., Adams, E., & Gold, J. (2009). Social information processing, moral reasoning, and emotion attributions: Relations with adolescents’ reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development, 80, 1739–1755. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01365.x.

Brengden, M., Vitaro, F., Tremblay, R., & Lavoie, F. (2001). Reactive and proactive aggression: Predictions to physical violence in different contexts and moderating effects of parental monitoring and caregiving behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 29, 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010305828208.

Card, N., & Little, T. (2006). Proactive and reactive aggression in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis of differential relations with psychosocial adjustment. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 466–480. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025406071904.

Cohen, D., & Strayer, J. (1996). Empathy in conduct-disordered and comparison youth. Developmental Psychology, 32, 988–998. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.32.6.988.

Cole, P., Martin, S., & Dennis, T. (2004). Emotion regulation as a scientific construct. Methodological challenges and directions for child development research. Child Development, 75, 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00673.x.

Crick, N., & Dodge, K. (1996). Social-information processing mechanisms in reactive and proactive aggression. Child Development, 67, 993–1002. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74.

Dodge, K., Lochman, J., Harnish, J., Bates, J., & Petit, G. (1997). Reactive and proactive aggression in school children and psychiatrically impaired chronically assaultive youth. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 106, 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.106.1.37.

Eisenberg, N. (2000). Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 665–697. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.665.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R., Murphy, B., Karbon, M., Smith, M., & Maszk, P. (1996). The relations of children's dispositional empathy-related responding to their emotionality, regulation, and social functioning. Developmental Psychology, 32, 195–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.32.2.195.

Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T., & Morris, A. (2014). Empathy-related responding in children. In M. Killen & J. Smetana (Eds.), Handbook of moral development (2nd ed., pp. 23–45). New York: Psychology Press.

Eisner, M., & Malti, T. (2015). Aggressive and violent behavior. In R. Lerner (Editor-in-Chief) & M. Lamb (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Vol. 3. Socioemotional processes (7th ed., pp. 794–841). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

Ellis, B. J., Volk, A. A., Gonzalez, J.-M., & Embry, D. D. (2016). The Meaningful Roles Intervention: An Evolutionary Approach to Reducing Bullying and Increasing Prosocial Behavior. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(4), 622–637.

Frick, P. J., Ray, J. V., Thornton, L. C., & Kahn, R. E. (2014). Annual Research Review: A developmental psychopathology approach to understanding callous-unemotional traits in children and adolescents with serious conduct problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(6), 532–548.

Giesbrechta, G., Miller, M., & Müller, U. (2010). The anger-distress model of temper tantrums: Associations with emotional reactivity and emotional competence. Infant and Child Development, 19, 478–497. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.677.

Gill, K., & Calkins, S. (2003). Do aggressive/destructive toddlers lack concern for others? Behavioral and physiological indicators of empathic responding in 2-year-olds. Development and Psychopathology, 15, 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457940300004X.

Hawley, P. (2014). The duality of human nature: Coercion and prosociality in youths’ hierarchy Ascension and social success. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 433–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414548417.

Hay, D. (2017). The early development of human aggression. Child Development Perspectives, 11, 102–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12220.

Hubbard, J., Smithmyer, C., Ramsden, S., Parker, E., Flanagan, K., Dearing, K., Relyea, N., & Simons, R. (2002). Observational, physiological, and self-report measures of children’s anger: Relations to reactive versus proactive aggression. Child Development, 73, 1101–1118. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00460.

Hubbard, J., McAuliffe, M., Morrow, M., & Romano, L. (2010a). Reactive and proactive aggression in childhood and adolescence: Precursors, outcomes, processes, experiences, and measurement. Journal of Personality, 78, 95–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00610.x.

Hubbard, J., Morrow, M., Romano, L., & McAuliffe, M. (2010b). The role of anger in children’s reactive versus proactive aggression: A review of findings, issues of measurement, and implications for intervention. In W. Arsenio & E. A. Lemerise (Eds.), Emotions, aggression, and morality in children: Bridging development and psychopathology (pp. 201–218). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.

Kaufman, A., & Kaufman, N. (2004). Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test-Second Edition (KBIT-2). American Guidance Services; Circle Pines, MN.

Lemerise, E., & Harper, B. (2010). The development of anger from preschool to middle childhood: Expressing, understanding, and regulating anger. In M. Potegal, G. Stemmler, & C. Spielberger’s (Eds.), International handbook of anger: Constituent and concomitant biological, psychological, and social processes (pp. 219–229). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-89676-2.

Little, T., Brauner, J., Jones, S., Nock, M., & Hawley, P. (2003a). Rethinking aggression: A typological examination of the functions of aggression. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 343–369. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2003.0014.

Little, T., Henrich, C., Jones, S., & Hawley, P. (2003b). Disentangling the “whys” from the “whats” of aggressive behaviour. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250244000128.

Lochman, J., Barry, T., Powell, N., & Young, L. (2010). Anger and aggression. In D. W. Nangle, D. J. Hansen, C. A. Erdley, & P. J. Norton (Eds.), Practitioner’s guide to empirically based measures of social skills (pp. 155–166). New York: Springer.

Lovett, B., & Sheffield, R. (2007). Affective empathy deficits in aggressive children and adolescents: A critical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.03.003.

Malti, T., & Noam, G. (2016). Social-emotional development: From theory to practice. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(6), 652–665. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1196178.

Malti, T., Gummerum, M., Keller, M., & Buchmann, M. (2009). Children’s moral motivation, sympathy, and prosocial behavior. Child Development, 80, 442–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01271.x.

Malti, T., Gummerum, M., Keller, M., Chaparro, M., & Buchmann, M. (2012). Early sympathy and social acceptance predict the development of sharing in children. PLoS One, 7(12), e52017. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052017.

Malti, T., Chaparro, M. P., Zuffianò, A., & Colasante, T. (2016). School-based interventions to promote empathy-related responding in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 45, 718–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2015.1121822.

Malti, T., Dys, S., Colasante, T., & Peplak, J. (2018). Emotions and morality: New developmental perspectives. In C. Helwig’s (Ed.), New perspectives on moral development (pp. 55–72). New York: Routledge.

Marsee, M., & Frick, P. (2010). Callous-unemotional traits and aggression in youth. In W. Arsenio & E. Lemerise (Eds.), Emotions, aggression, and morality in children: Bridging development and psychopathology (pp. 137–156). Washington D.C: American Psychological Association.

McAuliffe, M., Hubbard, J., Rubin, R., Morrow, M., & Dearing, K. (2007). Reactive and proactive aggression: Stability of constructs and relations to correlates. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 167, 365–382. https://doi.org/10.3200/GNTP.167.4.365-382.

Miller, P., & Eisenberg, N. (1988). The relation of empathy to aggressive and externalizing/antisocial behavior. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 324–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.324.

Miller, J., & Lynam, D. (2006). Reactive and proactive aggression: Similarities and differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 1469–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.06.004.

Moore, C., Hubbard, J., Morrow, M., Barhight, L., Lines, M., Sallee, M., & Hyde, C. (2018). The simultaneous assessment of and relations between children's sympathetic and parasympathetic psychophysiology and their reactive and proactive aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 44, 614–623. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21786.

Musher-Eizenman, D., Boxer, P., Danner, S., Dubow, E., Goldstein, S., & Heretick, D. (2004). Social-cognitive mediators of the relation of environmental and emotion regulation factors to children’s aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 30, 289–408. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20078.

Ongley, S., & Malti, T. (2014). The role of moral emotions in the development of children's sharing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 50, 1148–1159. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035191.

Orobio de Castro, B., Merk, W., Koops, W., Veerman, J., & Bosch, J. (2005). Emotions in social information processing and their relations with reactive and proactive aggression in referred aggressive boys. Journal of Clinical and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_10.

Ostrov, J., & Godleski, S. (2010). Toward an integrated gender-linked model of aggression subtypes in early and middle childhood. Psychological Review, 117, 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018070.

Ostrov, J., Murray-Close, D., Godleski, S., & Hart, E. (2013). Prospective associations between forms and functions of aggression and social and affective processes during child early childhood. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 116, 19–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2012.12.009.

Peplak, J., & Malti, T. (2017). “That really hurt, Charlie!” Investigating the role of sympathy and moral respect in children’s aggressive behavior. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 178, 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2016.1245178.

Phillips, N., & Lochman, J. (2003). Experimentally manipulated change in children’s proactive and reactive aggressive behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10028.

Poulin, F., & Boivin, M. (2000). Reactive and instrumental aggression: Evidence of a two-factor model. Psychological Assessment, 12, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.115.

Raine, A., Fung, A., Portnoy, J., Choy, O., & Spring, V. (2014). Low heart rate as a risk factor for child and adolescent proactive aggressive and impulsive psychopathic behavior. Aggressive Behavior, 40, 290–299. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21523.

Renouf, A., Brendgen, M., Seguin, J., Vitaro, F., Boivin, M., Tremblay, R., & Perusse, D. (2010). Interactive links between theory of mind, peer victimization, and reactive and proactive aggression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 1109–1123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9432-z.

Rohlf, H., Busching, R., & Krahé, B. (2017). Longitudinal links between maladaptive anger regulation, peer problems, and aggression in middle childhood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 63, 282–309. https://doi.org/10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.63.2.0282.

Schultz, D., Izard, C., & Bear, G. (2004). Children’s emotion processing: Relations to emotionality and aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 371–387. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579404044566.

Shaw, D., & Taraban, L. (2017). New directions and challenges in preventing conduct problems in early childhood. Child Development Perspectives, 11, 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12212.

Smetana, J., Toth, S., Cicchetti, D., Bruce, J., Kane, P., & Daddis, C. (1999). Maltreated and nonmaltreated preschoolers’ conceptions of hypothetical and actual moral transgressions. Developmental Psychology, 35, 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.269.

Statistics Canada. (2013). NHS profile, Mississauga, CY, Ontario, 2011 (Catalogue number 99–004-XWE). Retrieved March 25, 2018, from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang5E

Strayer, J., & Roberts, W. (2004). Empathy and observed anger and aggression in five-year-olds. Social Development, 13(1), –13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2004.00254.x.

Sutton, J., Smith, P., & Swettenham, J. (1999). Bullying and “theory of mind”: A critique of the “social skills deficit” view of antisocial behavior. Social Development, 8, 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00083.

Tremblay, R. (2010). Developmental origins of disruptive behaviour problems: The 'original sin' hypothesis, epigenetics and their consequences for prevention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51, 341–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02211.x.

van Norden, T., Haselager, G., Cillessen, A., & Bukowski, W. (2015). Empathy and involvement in bullying in children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0135-6.

Vitaro, F., Brendgen, M., & Barker, E. (2006). Subtypes of aggressive behaviors: A developmental perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025406059968.

Zeman, J., Shipman, K., & Suveg, C. (2002). Anger and sadness regulation: Predictions to internalizing and externalizing symptoms in children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 31, 393–398. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_11.

Zuffianò, A., Colasante, T., Buchmann, M., & Malti, T. (2018). The codevelopment of sympathy and overt aggression from middle childhood to early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 54, 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000417.

Zych, I., Ttofi, M., & Farrington, D. (2016). Empathy and callous-unemotional traits in different bullying roles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016683456.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Foundation Grant awarded to Tina Malti (FDN-148389). We would like to offer our sincere thanks to the children and caregivers who participated, and the members of the Laboratory for Social-Emotional Development and Intervention who assisted in the collection and processing of the data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 20 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jambon, M., Colasante, T., Peplak, J. et al. Anger, Sympathy, and Children’s Reactive and Proactive Aggression: Testing a Differential Correlate Hypothesis. J Abnorm Child Psychol 47, 1013–1024 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0498-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-018-0498-3