Abstract

Self-harm (suicidal ideation and attempts; non-suicidal self-injuries behavior) peaks in adolescence and early-adulthood, with rates higher for women than men. Young women with childhood psychiatric diagnoses appear to be at particular risk, yet more remains to be learned about the key predictors or mediators of self-harm outcomes. Our aims were to examine, with respect to self-harm-related outcomes in early adulthood, the predictive validity of childhood response inhibition, a cardinal trait of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as the potential mediating effects of social preference and peer victimization, ascertained in early adolescence. Participants were an ethnically and socioeconomically diverse sample of 228 girls with and without ADHD, an enriched sample for deficits in response inhibition. Childhood response inhibition (RI) predicted young-adult suicide ideation (SI), suicide attempts (SA), and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), over and above full-scale IQ, mother’s education, household income, and age. Importantly, teacher-rated social preference in adolescence was a partial mediator of the RI-SI/SA linkages; self-reported peer victimization in adolescence emerged as a significant partial mediator of the RI-NSSI linkage. We discuss implications for conceptual models of self-harm and for needed clinical services designed to detect and reduce self-harm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Self-injurious behaviors are defined as those that are “performed intentionally and with the knowledge that they can or will result in some degree of physical or psychological injury to oneself” (Nock 2010, p. 341). They peak in the adolescent and young-adult years (Nock 2009a, b). Estimates are that 13–45 % (Lloyd-Richardson et al. 2007; Plener et al. 2009; Ross and Heath 2002) of adolescents engage in some form of such actions, ranging from mild to severe, with nearly 18,000 treated each year in U.S. hospitals for self-harm (Hay and Meldrum 2010). Rates are higher for clinical samples of adolescents (40–60 %; DiClemente et al. 1991), and young women with childhood psychiatric diagnoses show particularly increased risk (Hinshaw et al. 2012; Nock et al. 2006; Kessler et al. 2005; Andrews and Lewinsohn 1992). For example, Swanson et al. (2014) found that women with persistent ADHD (i.e., present in both childhood and young adulthood), as well as those with childhood ADHD marked by high levels of impulsivity, were at highest risk for suicide attempts and moderate to severe levels of non-suicidal self-injury. Thus, a candidate variable for further investigation is response inhibition, which is linked to both ADHD and self-injury. Moreover, girls with poor response inhibition have noteworthy problems with peers, such as peer rejection and low social preference (Hinshaw 2002; Miller and Hinshaw 2010). Our aim is therefore to examine the longitudinal association between childhood RI and self-harm in young adulthood, including the potential adolescent mediators of peer social preference and peer victimization.

Self-Harm in Young Women and in Clinical Populations

Definitions and classification of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors have been inconsistent over the years, but clearer distinctions are emerging (Nock 2010). At the broadest level, self-harm includes thoughts and behaviors that are (a) suicidal in nature, in which there is intent to die (i.e., suicidal ideation [SI] and suicide attempt [SA]) or (b) non-suicidal, in which there is no reported intent to die (i.e., non-suicidal self-injury [NSSI]). More specifically, SI refers to having thoughts of killing oneself, whereas SA refers to acts of self-injury (i.e., poisoning) in which there is explicit intent to die. NSSI refers to deliberate bodily harm in the absence of suicidal intent (i.e., picking of the skin; cutting or burning oneself). Despite the conceptual distinctions between these behaviors, they are closely linked. For example, SI almost always precedes SA and actual completed suicide. A previous review of SI and SA showed that 88 % of suicide attempters reported ideation, with the other 12 % making impulsive attempts without premeditation (Lewinsohn et al. 1996). Similarly, SA and NSSI often co-occur within individuals (Brown et al. 2002). Nock and colleagues (2006) reported that 70 % of adolescents who reported engaging in NSSI reported a lifetime suicide attempt and 55 % reported multiple attempts. Therefore, it is important to consider self-injurious thoughts and behaviors as partially distinct yet interrelated phenomena.

Adolescence and young adulthood mark periods of increased risk and vulnerability for self-harm, and a psychiatric diagnosis increases the risk. In one study, 87.6 % of adolescents engaging in self-harm also met criteria for a DSM-IV Axis I disorder (Nock et al. 2006). Many have noted that females with psychiatric diagnoses are at particularly increased risk (Nock et al. 2006; Kessler et al. 2005; Andrews and Lewinsohn 1992). Attempts to understand relevant risk mechanisms and mediator processes have emerged (e.g., Seymour et al. 2012), but much work remains to be done in order to elucidate the developmental pathway(s) from childhood psychiatric risk to later self-harmful behaviors.

Response Inhibition, Peer Processes, and Self-Harm

Impulsivity involves a failure of response inhibition (RI), as well as a predisposition toward rapid, unplanned reactions to stimuli despite possible negative consequences (Moeller et al. 2014). RI, a behavioral example of impulsivity and a cardinal trait of ADHD, is defined as (a) the ability to withhold an ongoing response while (b) maintaining the performance of other behaviors and (c) ignoring interfering information (Barkley 1997). Children with ADHD consistently perform worse on RI tasks when compared to typically developing children (Homack and Roccio 2004). Similarly, performance on RI laboratory tasks has been used to distinguish those with and without ADHD (Aron and Poldrack 2005). Thus, RI is a core deficit in ADHD that might additionally serve as a significant risk factor for both externalizing-spectrum behaviors and self-harm (Mann et al. 2009; Verbruggen and Logan 2008).

In fact, both impulsivity and poor RI are associated with risk for self-harm (Gvion and Apter 2011; Mann et al. 2009; Horn et al. 2003). For example, poor RI, as measured via laboratory tasks, predicted NSSI and SA in adolescents (Dougherty et al. 2009). This finding suggests that adolescents and young adults who have difficulty controlling their own behaviors or who “act without thinking” might be at particular risk for self-harmful behaviors (see Mann et al. 2009).

The relation between poor RI and later self-harm may be direct or indirect (i.e., subject to mediational processes). First, RI is associated with social functioning and peer rejection in children and adolescents. Specifically, low RI, as measured via a laboratory task (Continuous Performance Task), predicted low peer social preference (as rated by teachers) over and above ADHD diagnostic status (Miller and Hinshaw 2010). Similarly, in typically developing children, impulsivity has been linked to negative peer ratings of agreeableness (Cumberland-Li et al. 2004). Thus, poor RI in childhood (i.e., not waiting for a turn during recess) might be a precursor to deficits in peer functioning in adolescence. Second, adolescents frequently cite problems with their peers, including peer rejection/low social preference, as a precipitant of suicidal behavior (Berman and Schwartz 1990; Hawton et al. 1996). Similarly, self-reported measures of peer rejection and low friendship support have been associated with increases in suicidal ideation or behavior (Prinstein et al. 2001).

An important distinction needs to be made between peer rejection/social preference and peer victimization. Social preference refers to a combination of low acceptance and high rejection from peers (Gottman 1977), whereas peer victimization refers to openly confrontational attacks (direct forms) and covertly manipulative attacks (Mynard and Joseph 2000) made by peers. It is unclear whether peer preference versus peer victimization may be more specifically linked with suicidal and self-injurious behavior. Both social rejection and peer victimization among adolescents are associated with increased risk for self-harm, especially among girls (Hilt et al. 2008; Klomek et al. 2008; Heilbron and Prinstein 2010). Girls with ADHD, in particular, are at increased risk for both overt and relational peer victimization (Cardoos and Hinshaw 2011; Hinshaw 2002). Previous research suggests that girls have heightened concern about peer evaluations, with greater reactivity to peer evaluations than boys (Rose and Rudolph 2006). Thus, peer rejection may be particularly devastating for girls; self-harm, including self-mutilation and SA (Marr and Field 2001), may be a means of regulating intensely negative affect (Nock 2010). Indeed, adolescents engage in NSSI as a strategy of reducing negative affect (Chapman et al. 2006; Klonsky 2007). A key concern, however, is that much existing research has examined associations between peer processes and self-harm via cross-sectional designs (e.g., Kim and Leventhal 2008). Prospective longitudinal research is a priority.

Utilizing data from the present sample, Swanson et al. (2014) showed that a laboratory-based measure of response inhibition, as well as comorbid externalizing symptoms—both measured during adolescence—emerged as simultaneous, partial mediators of a highly significant childhood ADHD-young adult NSSI linkage in females with ADHD. Adolescent internalizing symptoms also emerged as a partial mediator of the equally strong childhood ADHD-young adult SA linkage. Adolescent mediators, however, were limited to measures of psychiatric comorbidity and neuropsychological functioning and did not include peer-related factors. Our purpose herein, therefore, is to examine (a) childhood RI as a predictor and (b) adolescent peer processes as potential mediators of associations to later self-harm.

Current Study

In an all-female sample followed prospectively from childhood through young adulthood, we first consider RI, assessed during childhood, as a dimensional predictor of young adult self-harm (SI, SA, and NSSI, each considered independently). The continuous nature of the RI construct may provide more power than categorical diagnoses (e.g., ADHD vs. non-ADHD clinical groups) with respect to such predictions. Second, we examine the potential mediating effects of adolescent social preference and peer victimization with regard to linkages between RI and self-harm. Specifically, we hypothesize that childhood RI will predict self-harm in young adulthood and that peer factors (e.g., social preference and peer victimization), ascertained during adolescence, will mediate the association between childhood RI and young-adult self-harm. More specifically, we hypothesize that peer victimization will mediate the association between RI and NSSI, because the direct threats entailed by victimization should be related to the affect-regulatory functions of NSSI (Klonsky 2009; Muehlenkamp et al. 2009; Nock 2009a, b). We also predict that adolescent social preference will mediate the association between RI and SI/SA, because the pervasive isolation incurred by peer rejection should be more explicitly linked to suicidal behavior. Although we also examine ADHD versus comparison group differences with respect to social preference, peer victimization, SI, SA, and NSSI, our primary focus is on RI as a dimensional predictor.

Method

Overview of Procedures

From the San Francisco Bay Area, we recruited girls from schools, mental health centers, pediatric practices, and through direct advertisements, to participate in research summer programs in 1997, 1998, and 1999. These programs were designed as enrichment rather than therapeutic endeavors, with emphasis on ecologically valid measures of behavior, peer status, and cognition. After extensive diagnostic assessments, 140 girls with ADHD and 88 age- and ethnicity-matched comparison girls were selected (W1, M = 9.6, range 6–12; Hinshaw 2002). Five years later, we invited all participants for prospective follow-up (W2, M = 14.2, range 11–18; Hinshaw et al. 2006); the retention rate was 92 %. Subsequently, we invited all participants and parents for a 10-year follow-up (W3, M = 19.6, range 17–24), involving two half-day, clinic-based assessment sessions. Aided by use of social media in some cases, we located, consented, and obtained data from 216 of the 228 original participants (95 % retention), although not every participant completed all measures. When necessary, we performed telephone interviews or home visits. We prioritized multi-domain, multi-source, and multi-informant data collection.

Participants

Participants included 228 ethnically-diverse girls (53 % White, 27 % African-American, 11 % Latina, 9 % Asian-American) with (n = 140) and without (n = 88) childhood ADHD, ascertained via a rigorous, multi-gated screening and assessment process that ultimately relied on the parent-administered Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, 4th ed. (DISC-IV; Shaffer et al. 2000) and SNAP rating scale (Swanson 1992) in order to establish the ADHD diagnosis. Comparison girls, screened to match the ADHD sample on age and ethnicity, could not meet diagnostic criteria for ADHD via either adult ratings or structured interview criteria. Some (3.4 %) met criteria for internalizing disorders (anxiety/depression) or for disruptive behavior disorders (6.8 %); but our goal was not to match comparison participants to those with ADHD on comorbid conditions, which would have yielded a non-representative comparison group. Exclusion criteria for both groups were intellectual disability, pervasive developmental disorders, psychosis or overt neurological disorder, lack of English spoken in the home, and medical problems prohibiting summer camp participation.

To evaluate the representativeness of the retained sample, we contrasted W1 measures for the 12 participants lost to the W3 follow-up versus those retained. Of 23 analyses, on measures ranging from demographics, core ADHD symptoms, comorbid symptoms, and functional impairments, five were significant: the non-retained subsample had lower family incomes and Full-Scale IQ scores and higher W1 teacher-rated ADHD, externalizing, and internalizing symptoms. Although the W3 sample appears generally representative of the total sample, the non-retained subgroup was more impaired cognitively and behaviorally.

Measures

Independent Variable: Childhood (W1) Response Inhibition

Continuous Performance Task (CPT; Conners 1995)

The CPT is a 14-minute computerized task of visual attentional processing and RI for which participants are asked to press the spacebar when a target letter appears on the screen (all letters except ‘X’), and not press the spacebar when they see the letter ‘X’. Failing to inhibit the bar-pressing response to the letter “X” is considered an error of commission. The task consists of trials that are presented in six blocks (interstimulus intervals: 1, 2, and 4 s); stimuli are displayed for 250 ms. This task differs from other commonly-used continuous performance tasks by featuring frequent display of target stimuli (requiring response) and relatively infrequent display of non-targets (requiring nonresponse), so that response inhibition rather than detection of rare stimuli is featured.

We utilized the percentage of commission errors, which is a commonly used measure of RI (Janis and Nock 2009; McGee et al. 2000). Our prior research has shown significant differences in both omission and commission errors between ADHD and comparison girls in the present sample (at baseline and W2 and W3), whereby the girls with ADHD reveal higher percentages of both types of errors, with effect sizes in the medium range (e.g., Hinshaw 2002; Hinshaw et al. 2007). Conners (1995) also provided criterion-related validity data for omission and commission errors based on known-groups differentiation.

Criterion Variables: Young Adult (W3) Self-Harm

Barkley Suicide Questionnaire (Barkley 2006)

This is a three-item self-report scale: “have you ever considered suicide?”; “have you ever attempted suicide?”; “have you ever been hospitalized for an attempt?” A positive endorsement to any question is followed up with a lifetime frequency question (“how many times?”). We analyzed the dichotomous items of suicide ideation and suicide attempts.

Self-Injury Questionnaire (SIQ)

At Wave 3 the young women responded to the SIQ, an interviewer-administered measure based on a modification of Claes et al. (2001) SIQ. Vanderlinden and Vandereycken (1997) provide data supporting the validity and reliability of that measure within eating-disordered samples. We assessed variety and frequency of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI). Participants were asked whether, in the past year, they had deliberately injured themselves (e.g., scratched or cut their skin with objects, burned themselves, hit themselves hard, pulled hair out) and, if so, how often (1 = only once; 6 = a couple of times a day). We created a NSSI severity variable that accounted for frequency and variety (type). Higher scores included more severe types of self-harm (i.e., cutting) and higher frequencies (i.e., a couple times a day).

Hypothesized Mediators: Adolescent (W2) Peer Social Preference and Victimization

Dishion Social Acceptance Scale: (DSPS; Dishion 1990)

The DSPS is a 3-item teacher-completed scale that measures the proportion of classmates who accept, reject, and ignore the adolescent in question on a scale of 1–5. We subtracted “rejected” from “accepted” ratings to obtain a widely-used social preference score (see Lahey et al. 2004; Sandstrom and Cillessen 2003). Although the gold standard for appraising peer preference is sociometric appraisals directly from agemates, obtaining school-wide peer nominations from a middle-school and high-school sample was prohibitive. Furthermore, because of concerns regarding the accuracy of self-reports from individuals with ADHD (e.g., Barkley et al. 2008), we wished to avoid self-reported appraisals of peer status. Dishion (1990) provided data on the ability of the DSPS to provide a valid approximation to peer sociometric measures, which included moderate to strong correlations between items of the DSPS and peer-derived sociometric data. The DSPS is frequently used to estimate peer regard in middle-school and high-school samples.

Social Relationships Interview

This project-derived interview includes items related to deviant peers, friendships, and romantic relationships. Relevant questions were based on conceptual models of friendship attainment and social/dating relationships. We created a peer victimization variable by averaging three questions, rated on a likert scale (1=never, 2=less than once per month, 3=once or twice per month, 4=once a week, 5=a few times a week, and 6=every day): (a) “have you ever been hit?”, (b) “have you ever been teased to your face?”, and (c) “have you ever been teased behind your back?” Across these three items, Cronbach’s alpha in our sample = 0.65, revealing adequate internal consistency. Additionally, we computed correlations between our peer victimization variable and other W2 measures related to peer victimization, finding convergent validity. Specifically, peer victimization was positively related to teacher-rated peer rejection (r = 0.35, p < 0.001) and parent-rated conflict with peers (r = 0.30, p < 0.001). Peer victimization was also inversely related to mother’s rating of whether the girl has friends (r = −0.25, p < 0.001) and teacher’s rating of the girl’s social preference (r = −0.36, p < 0.001). Self-report was utilized here because of the covert nature of peer victimization and because self-reported measures are cited as the optimal means of assessing this construct (Gratz 2001; Hawker and Boulton 2000).

Covariates

We included several important background variables as covariates. First, we used girls’ Full Scale IQ at W1 as indexed by the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, third edition (WISC-III; Wechsler 1991). The WISC-III is a psychometrically sound and widely-used test of intelligence. Test-retest reliabilities are high for the Full Scale IQ (0.94–0.96; Kaufman 1994). We also included Wave 1 measures of mother’s education and household income, as well as participant’s age at the W3 follow-up.

Data Analytic Plan

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Mac (Version 22; SPSS, 2013). First, we computed associations among the predictor (W1 commissions), proposed mediators (W2 social preference and peer victimization), and the criterion measures of self-harm (W3 SI, SA, and NSSI). To assess differences between ADHD and comparison groups we used chi-square tests for dichotomous variables (SI and SA), and independent sample t-tests for continuous variables (commissions, social preference, peer victimization, and NSSI). Effect sizes (odds ratios for SI and SA; Cohen’s d for commissions, social preference, peer victimization, and NSSI) were also calculated. We also conducted separate analyses using linear regressions to ensure that the relevant pathways were significant and in the hypothesized directions. To test multiple mediators, we used the bootstrapping procedure described by Shrout and Bolger (2002) and Preacher and Hayes (2008). Testing simultaneous mediators distinguishes the effect of each mediator in the model, without the biases of parameter estimates (Preacher and Hayes 2008). The bootstrapping procedure is a statistical simulation that is used to generate an empirically derived representation of the sampling distribution of the indirect effect (Hayes 2013, pg. 106). After sampling those cases with replacement, a point estimate of the indirect effect (a-prime x b-prime) is determined for the sample and repeated 10,000 times. We formed 95 % bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals based upon the distribution of these effects and inferred statistical significance if this interval did not contain 0 (see Preacher and Hayes 2008; Shrout and Bolger 2002). All mediation models were tested covarying child IQ and the sociodemographic covariates, which functioned as statistical controls of the relation between the mediator and criterion variables.

Results

Intercorrelations and Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 presents the correlations among study variables. As expected, W1 commission errors, W2 social preference and peer victimization, and W3 self-harm were significantly associated with one another. W1 commission errors were negatively associated with social preference (r = −0.17, p < 0.05), and positively associated with peer victimization (r = 0.22, p < 0.01). Similarly, W1 commission errors were positively associated with all three self-harm-related outcomes: SI (r = 0.15, p < 0.05), SA (r = 0.18, p < 0.05) and NSSI (r = 0.18, p < 0.05). Peer victimization and social preference were significantly related to self-harm in the expected direction. Social preference was negatively associated with peer victimization (r = −0.36, p < 0.001) as well as SI (r = −0.26, p < 0.01), SA (r = −0.20, p < 0.05), and NSSI (r = −0.11, p < 0.05). Similarly, peer victimization was positively associated with SI (r = 0.25, p < 0.001), SA (r = 0.18, p < 0.01), and NSSI (r = 0.30, p < 0.001). W3 criterion variables of self-harm were also positively associated with each other: as expected, SI was positively and strongly associated with SA (r = 0.69, p < 0.001) and moderately so with NSSI (r = 0.38, p < 0.001); SA was positively but modestly associated with NSSI (r = 0.26, p < 0.001).

Table 2 presents mean values and standard deviations for each variable, across the entire sample and within the two diagnostic groups. Mean comparison tests were conducted for girls with ADHD versus the comparison girls; these are also presented in Table 2. The ADHD sample had significantly lower mean social preference scores and higher peer victimization mean scores at Wave 2 than did the comparison sample. A parallel pattern emerged for W3 NSSI, which was also higher for the ADHD group. Among the girls with ADHD, 35.5 % endorsed having suicidal thoughts and 17.7 % endorsed a previous suicide attempt. Of the comparison sample, 22.4 % endorsed having suicidal thoughts and 6 % reported a previous suicide attempt.

Regression Analyses: Predicting Self-Harm from W1 Response Inhibition

We predicted that W1 commission errors, our indicator of RI, would predict W3 self-harm (SI, SA and NSSI), using linear regressions after mean-centering the predictor (W1 commissions). For these, we entered our sociodemographic and cognitive covariates (child IQ, mother’s education, household income, and age at W3) on the first step and W1 commission errors on the second step. Results revealed that W1 commission errors predicted W3 SI, although after controlling for covariates the significance was marginal (β = 0.133, p = 0.064, ΔR 2 = 0.02). As hypothesized, W1 commission errors also significantly predicted W3 SA (β = 0.170, p < 0.05, ΔR 2 = 0.03) and NSSI severity (β = 0.163, p < 0.05, ΔR 2 = 0.03), over and above child IQ, mother’s education, household income, and age at W3.

Mediational Analyses Footnote 1

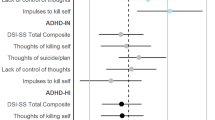

RI-suicide Ideation Link

Despite the marginally significant relation between W1 commission errors and W3 SI, mediation tests can still be conducted (Hayes 2013). Via bootstrapping analyses we examined whether W2 social preference and peer victimization mediated the relation between W1 commission errors and W3 SI. Social preference was a significant partial mediator, indirect effect [IE] = 0.0042, SE = 0.0030, CI95 = 0.0002 – 0.0122 (see Fig. 1). Social preference remained a significant partial mediator when peer victimization was entered into the model.

The relation between W1 Commissions and W3 Suicide Ideation (y/n) was partially mediated by W2 social preference scores over and above WISC Full-Scale IQ, mother’s education, and household income at W1 and age at W3. Data represent indirect effects and standard errors using 10,000 bootstrap samples to obtain bias-corrected and accelerated 95 % confidence intervals

RI-suicide Attempt Link

In parallel, we examined whether the W2 candidate mediators of social preference and peer victimization mediated the relation between W1 commissions and W3 SA. Social preference was a significant partial mediator, indirect effect [IE] = 0.0775, SE = 0.0537, CI95 = 0.0049 – 0.2257 (see Fig. 2), but peer victimization was not a significant mediator. Social preference remained a significant partial mediator when peer victimization was entered into the model.

The relation between W1 Commissions and W3 Suicide Attempts (y/n) was partially mediated by W2 social preference scores over and above WISC Full-Scale IQ, mother’s education, and household income at W1 and age at W3. Data represent indirect effects and standard errors using 10,000 bootstrap samples to obtain bias-corrected and accelerated 95 % confidence intervals

RI-NSSI Link

In the final mediation model, W2 peer victimization was a significant partial mediator of the relation between W1 commissions and W3 NSSI severity, indirect effect [IE] = 0.0022, SE = 0.0012, CI95 = 0.0004 = 0.0054 (see Fig. 3), but social preference was not a significant mediator. Peer victimization maintained significance when social preference was entered into the model.

The relation between W1 Commissions and W3 NSSI was partially mediated by W2 Peer Victimization over and above WISC Full-Scale IQ, mother’s education, and household income at W1 and age at W3. Data represent indirect effects and standard errors using 10,000 bootstrap samples to obtain bias-corrected and accelerated 95 % confidence intervals

Discussion

In this examination of predictors and mediators of self-harm, we expanded findings reported by Hinshaw et al. (2012) and Swanson et al. (2014) regarding elevated self-harm among young women with childhood ADHD. We used dimensional scores of RI as the childhood (W1) predictor and young adult (W3) SI, SA, and NSSI severity as the criterion measures; we also featured adolescent (W2) mediators related to peer preference and peer victimization. First, our dimensional analyses revealed that W1 commission errors, indexing RI, significantly predicted W3 SA and NSSI severity, although the relation between W1 commissions and W3 SI was only marginally significant after inclusion of our cognitive and demographic covariates. Second, teacher-rated social preference in adolescence emerged as a significant partial mediator of the RI-SI and RI-SA links, whereas self-reported peer victimization in adolescence served as a significant partial mediator of the RI-NSSI link.

Our patterns of findings are consistent with those of Mann and colleagues (2009), who found that impulsivity is an important component of suicidal behaviors. Indeed, measures of impulsivity have been associated with suicidal behavior in prospective and retrospective studies (for review see, McGirr et al. 2008). For example, Swanson et al. (2014) found that young women with childhood-diagnosed ADHD engaged in the most severe forms of NSSI. In particular, the Combined type was at elevated risk, revealing the potential role of childhood impulsivity, and this link was mediated by poor RI (as indexed by the Cancel Underline test) during adolescence. This pattern suggests that poor RI may explain the predictive relation between ADHD diagnosis and NSSI outcomes. Therefore, risk assessments for adolescents with suicidal ideation or previous suicide attempts should consider not only diagnostic status or clinical symptoms but also behavioral indices of impulsivity.

The mediator findings suggest an important pathway from poor RI to later self-harm through adolescent interpersonal difficulties. Although the link between impulsivity and self-harm has been investigated, few studies have examined adolescent pathways to self-harm. Social preference and peer victimization were chosen as candidate mediators, as each has been linked to both poor RI/impulsivity (Miller and Hinshaw 2010) and self-harm (Prinstein et al. 2001). Moreover, peer relationships become extremely salient during adolescent years, as teens shift from parental figures to peers as primary attachment figures (Fuligni and Eccles 1993). The impact of social preference and peer victimization is particularly heightened for girls and women, because females tend to have a strong concern about peer evaluations, with greater reactivity to peer evaluations than males (Rose and Rudolph 2006).

Our findings suggest that different peer processes help to explain the association between childhood RI and varied forms of self-harm in young adulthood. Social preference scores, as rated by teachers, mediated the RI-SI and RI-SA links, suggesting that intentional and deliberate forms of self-harm with intent to end one’s life are specifically associated with being isolated and rejected from peers (see Perkins and Hartless 2002; Prinstein et al. 2000). Prinstein et al. (2010) also found that greater levels of peer rejection were associated with more severe suicidal ideation. However, forms of self-harm with no intent to die (i.e., NSSI) were associated with a more direct and overt form of interpersonal problems: peer victimization.

Taken together, these results suggest that different types of peer relationships (i.e., peer rejection vs. peer victimization) are differentially associated with later maladjustment (i.e., different forms of self-harm). For example, pervasive social isolation/rejection might have more severe repercussions than peer victimization, because the former is associated with intentional forms of self-harm, both SI and SA (Bearman and Moody 2004; Berkman et al. 2000; Bearman 1991). Peer victimization, on the other hand, has been linked to NSSI (Hilt et al. 2008). Previous research supports that children who are victimized by peers may be protected from later maladjustment if they have at least one quality friendship (Bollmer et al. 2005). Similarly, previous research has found that a sizeable proportion of victimized children are not rejected by peers (Kochenderfer and Ladd 1997). This set of findings suggests that some relationships may pose a greater risk for maladjustment than others. For instance, compared to peer victimization, peer isolation was associated with more negative outcomes and was uniquely associated with both dissatisfaction in relationships and maladjustment (Ladd et al. 1997). Theorizing with respect to causal mechanisms requires additional research on such cognitive mediational processes.

Our investigation should be viewed in the context of several limitations. First, it is unclear whether these findings will generalize to male samples and to other diagnostic groups. It is particularly important to extend these findings to male samples because of the higher completed suicide among men than women—and because men are less likely than women to seek services (Lyons et al. 2000). Similarly, examining whether these findings extend to additional clinical samples will help clarify the elevated risk for self-harm in populations with psychopathology, given that more than 90 % of those who commit suicide have experienced a mental illness before their death (Lyons et al. 2000).

Second, we measured social preference via teacher reports, which may have underestimated the actual frequency of peer rejection. Although the gold standard for appraising peer preference is sociometric appraisals directly from age-mates, obtaining school-wide peer nominations from a middle-school and high-school sample was prohibitive. Furthermore, given limitations of the accuracy of self-reports from individuals with ADHD (e.g., Barkley et al. 2008), we did not wish to use self-reported appraisals of peer status. Although teacher reports were a helpful measure of social preference, we were able to obtain teacher reports from only a restricted subsample (n = 152). On the other hand, our measure of peer victimization was self-reported; it is plausible that our sample underreported instances of victimization because they did not feel comfortable disclosing their victimization history or because of recall bias. In addition, although the proportions of variance contributed by RI to our criterion variables were generally small, small to medium effects may have real relevance; they require careful research and statistical analyses (e.g., Keppel and Wickens 2004, p.162).

Third, our data also did not permit an exhaustive evaluation of our criterion variables. For example, suicide ideation and suicide attempts were assessed via a single self-report question. In addition, we assessed only ideation and not intended plans. Measuring the latter is important because SI in the continued absence of a plan or attempt is associated with decreasing risk of suicide plans and attempts over time (Nock et al. 2008). We did not assess self-harm behaviors at Wave 2 and are therefore unable to provide crucial temporal information about the rates and frequency of these behaviors. We assume that our mediators of social functioning preceded the occurrences of self-harm, although in some cases this may not be the case.

Last, our non-retained sample differed from the retained sample with respect to five key baseline measures, including lower family income and Full-Scale IQ scores, and higher W1 teacher-rated ADHD, externalizing, and internalizing symptoms. The exclusion of these 12 participants, who were initially impaired both clinically and socio-economically, may actually underestimate the strength of our findings.

Nonetheless, the limitations here provide important launching points for future research agendas to address unanswered questions. For example, examination of other risk factors associated with self-harming behaviors could elucidate the linkage between RI and self-harm. In particular, academic achievement may a salient risk factor associated with self-harm in adolescence and adulthood. The association between academic outcomes and suicidal ideation has been well documented (Ayyash-Abdo 2002; Lewinsohn et al. 1993; Nelson and Crawford 1990), with poor academic achievement associated with SA (Ang and Huan 2006). Similarly, it will also be useful to explore protective factors that buffer the risk of self-harm in women. Some theoretically driven protective factors associated with reduced risk of self-harm could include perceived support, emotion regulation, and self-esteem (Nock et al. 2008).

Overall, our findings provide illumination of pathways to self-harm in young adolescent women with ADHD, including the role of early impulsivity and adolescent peer difficulties. These findings also have several clinical and public health implications. Indeed, self-harm, whether suicidal or non-suicidal in intent, has increased in prevalence and has become a concerning public health issue among adolescents and young adults (e.g., Storey et al. 2005). Crucially, it is important to identify adolescents at risk because it is rare for teens who self-injure to seek psychological services (Whitlock et al. 2006). Surprisingly, up to 83 % of people committing suicide have had contact with a primary care physician within a year of their death (Mann et al. 2005), suggesting a crucial gap between risk assessment strategies between primary care and mental health providers. Assessment of peer difficulties might inform providers and family members regarding the likelihood of self-harm. Other suicide prevention strategies include public education campaigns aimed at improving recognition of suicide risk and reducing the stigmatization of suicide and screening aims for high risk individuals (i.e., high school students, juvenile offenders, and youth in general; see Shaffer et al. 2004; Cauffman 2004; Joiner et al. 2002).

Taken together, these findings highlight the need for more holistic assessments of suicide risk. A shift from focusing solely on individual mental health variables (such as ADHD) to models that examine the interactions between intrapsychic and interpersonal factors should provide a more comprehensive means of understanding and preventing self-harm.

Notes

We conducted three different mediation models, one per criterion measure, and included the mediators that survived significance.

References

Andrews, J. A., & Lewinsohn, P. M. (1992). Suicidal attempts among older adolescents: prevalence and co-occurrence with psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 655–662.

Ang, R. P., & Huan, V. S. (2006). Relationship between academic stress and suicidal ideation: testing for depression as a mediator using multiple regression. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 37, 133–143.

Aron, A. R., & Poldrack, R. A. (2005). The cognitive neuroscience of response inhibition: relevance for genetic research in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 57, 1285–1292.

Ayyash-Abdo, H. (2002). Adolescent suicide: an ecological approach. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 459–475.

Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 65–94.

Barkley, R. A. (2006). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and Treatment (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford.

Barkley, R. A., Murphy, K. R., & Fischer, M. (2008). ADHD in adults: What the science says. New York: Guilford.

Bearman, P. (1991). The social structure of suicide. Sociological Forum, 6, 501–524.

Bearman, P., & Moody, J. (2004). Suicide and friendships among American adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 94, 89–95.

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., & Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine, 51, 843–857.

Berman, A. L., & Schwartz, R. H. (1990). Suicide attempts among adolescent drug users. American Journal of Diseases of Children, 144, 310–314.

Bollmer, J. M., Milich, R., Harris, M. J., & Maras, M. A. (2005). A friend in need: the role of friendship quality as a protective factor in peer victimization and bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(6), 701–1712.

Brown, M. Z., Comtois, K. A., & Linehan, M. M. (2002). Reasons for suicide attempts and nonsuicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111(1), 198–202.

Cardoos, S. L., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2011). Friendship as protection from peer victimization for girls with and without ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(7), 1035–1045.

Cauffman, E. (2004). A statewide screening of mental health symptoms among juvenile offenders in detention. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(4), 430–439.

Chapman, A. L., Gratz, K. L., & Brown, M. Z. (2006). Solving the puzzle of deliberate self- harm: the experiential avoidance model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 371–394.

Claes, L., Vandereycken, W., & Vertommen, H. (2001). Self-injurious behavior in eating-disordered patients. Eating Behaviors, 2, 263–272.

Conners, C. K. (1995). Conners’ Continuous Performance Test computer program: User’s manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems.

Cumberland-Li, A., Eisenberg, N., & Reiser, M. (2004). Relations of young children’s agreeableness and resiliency to effortful control and impulsivity. Social Development, 13(2), 193–212.

DiClemente, R. J., Ponton, L. E., & Hartley, D. (1991). Prevalence and correlates of cutting behavior: risk for HIV transmission. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 30, 735–739.

Dishion, T. (1990). The peer context of troublesome child and adolescent behavior. In P. E. Leone (Ed.), Understanding troubled and troubling youth (pp. 128–153). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Dougherty, D. M., Mathias, C. W., Marsh-Richard, D. M., Prevette, K. N., Dawes, M. A., Hatzis, E. S., & Nouvion, S. O. (2009). Impulsivity and clinical symptoms among adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury with or without attempted suicides. Psychiatry Research, 169(1), 22–27.

Fuligni, A. J., & Eccles, J. S. (1993). Perceived parent–child relationships and early adolescents’ orientation toward peers. Developmental Psychology, 29, 622–632.

Gottman, J. (1977). The effects of a modeling film on social isolation in preschool children a methodological investigation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 5, 69–78.

Gratz, K. L. (2001). Measurement of deliberate self-harm: preliminary data on the deliberate self-harm inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23(4), 253–263.

Gvion, Y., & Apter, A. (2011). Aggression, impulsivity, and suicide behavior: a review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Research, 15(2), 93–112.

Hawker, D. S., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: a meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(4), 441–455.

Hawton, K., Fagg, J., & Simkin, S. (1996). Deliberate self-poisoning and self-injury in children and adolescents under 16 years of age in Oxford, 1976–1993. British Journal of Psychiatry, 169, 202–208.

Hay, C., & Meldrum, R. (2010). Bullying victimization and adolescent self-harm: testing hypotheses from general strain theory. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(5), 446–459.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford.

Heilbron, N., & Prinstein, M. J. (2010). Adolescent peer victimization, peer status, suicidal ideation, and non-suicidal self-injury: examining concurrent and longitudinal associations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56(3), 388–419.

Hilt, L. M., Cha, C. B., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2008). Nonsuicidal self-injury in young adolescent girls: moderators of the distress-function relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 63–71.

Hinshaw, S. P. (2002). Preadolescent girls with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: background characteristics, comorbidity, cognitive and social functioning, and parenting practices. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1086–1098.

Hinshaw, S. P., Owens, E. B., Sami, N., & Fargeon, S. (2006). Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adolescence: evidence for continuing cross-domain impairment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 489–499.

Hinshaw, S. P., Carte, E. T., Fan, C., Jassy, J. S., & Owens, E. B. (2007). Neuropsychological functioning of girls with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder followed prospectively into adolescence: evidence for continuing deficits? Neuropsychology, 21, 263–273.

Hinshaw, S. P., Owens, E. B., Zalecki, C., Huggins, S. P., Montenegro-Nevado, A. J., Schrodek, E., & Swanson, E. N. (2012). Prospective follow-up of girls with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder into early adulthood: continuing impairment includes elevated risk for suicide attempts and self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 1041–1051.

Homack, S., & Roccio, C. A. (2004). A meta-analysis of the sensitivity and specificity of the stroop color and word test with children. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 19(6), 725–743.

Horn, N. R., Dolan, M., Elliott, R., Deakin, J. F. W., & Woodruff, P. W. R. (2003). Response inhibition and impulsivity: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia, 41(14), 1959–1966.

Janis, I. B., & Nock, M. K. (2009). Are self-injurers impulsive? Results from two behavioral laboratory studies. Psychiatry Research, 169, 261–267.

Joiner, T. E., Jr., Pfaff, J. J., & Acres, J. G. (2002). A brief screening tool for suicidal symptoms in adolescents and young adults in general health settings: reliability and validity data from the Australian national general practice youth suicide prevention project. Behavior Research and Therapy, 40(4), 471–481.

Kaufman, A. S. (1994). Intelligent testing with the WISC-III. New York: Wiley.

Keppel, G., & Wickens, T. D. (2004). Design and analysis: A researcher’s handbook (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Borges, G., Nock, M., & Wang, P. S. (2005). Trends in suicide ideation, plans, gestures, and attempts in the United States, 1990–1992 to 2001–2003. Journal of the American Medical Association, 293(20), 2487–2495.

Kim, Y. S., & Leventhal, B. (2008). Bullying and suicide. A review. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20(2), 133–154.

Klomek, A. B., Marrocco, F., Kleinman, M., Schonfeld, I. S., & Gould, M. S. (2008). Peer victimization, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 38(2), 166–180.

Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: a review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 226–239.

Klonsky, E. D. (2009). The functions of self-injury in young adults who cut themselves: clarifying the evidence for affect-regulation. Psychiatry Research, 166, 260–268.

Kochenderfer, B. J., & Ladd, G. W. (1997). Victimized children’s responses to peers’ aggression: behaviors associated with reduced versus continued victimization. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 59–73.

Ladd, G. W., Kochenderfer, B. J., & Coleman, C. C. (1997). Classroom peer acceptance, friendship, and victimization: distinct relational systems that contribute uniquely to children’s school adjustment. Child Development, 68(6), 1181–1197.

Lahey, B. B., Pelham, W. E., Loney, J., Kipp, H., Ehrhardt, A., Lee, S. S., et al. (2004). Three- year predictive validity of DSM-IV attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children diagnosed at 4–6 years of age. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 2014–2020.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Rohde, P., & Seeley, J. R. (1993). Psychosocial characteristics of adolescents with a history of suicide attempt. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 32, 60–68.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Rohde, P., & Seeley, J. R. (1996). Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 3(1), 25–46.

Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., Perrine, N., Dierker, L., & Kelley, M. L. (2007). Characteristics and functions of nonsuicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 37, 1183–1192.

Lyons, C., Price, P., Embling, S., & Smith, C. (2000). Suicide risk assessment: a review of procedures. Accident and Emergency Nursing, 8(3), 178–186.

Mann, J. J., Apter, A., Bertolote, J., Beautrais, A., Currier, D., Haas, A., & Hendin, H. (2005). Suicide prevention strategies. Journal of the American Medical Association, 294(16), 2064–2074.

Mann, J. J., Arango, V. A., Avenevoli, S., Brent, D. A., Champagne, F. A., Clayton, P., & Wenzel, A. (2009). Candidate endophenotypes for genetic studies of suicidal behavior. Biological Psychiatry, 65(7), 556–563.

Marr, N., & Field, T. (2001). Bullycide: Death at playtime. Success Unlimited.

McGee, R. A., Clark, S. E., & Symons, D. K. (2000). Does the Conners’ continuous performance test aid in ADHD diagnosis? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 28, 415–424.

McGirr, A., Renaud, J., Bureau, A., Seguin, M., Lesage, A., & Turecki, G. (2008). Impulsive-aggressive behaviors and completed suicide across the life cycle: a predisposition for younger age of suicide. Psychological Medicine, 38, 407–417.

Miller, M., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2010). Does childhood executive function predict adolescent functional outcomes in girls with ADHD? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 315–326.

Moeller, F. G., Barratt, E. S., Dougherty, D. M., Schmitz, J. M., & Swann, A. C. (2014). Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(11), 1783–1793.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., Engel, S. G., Wadeson, A., Crosby, R. D., Wonderlich, S. A., et al. (2009). Emotional states preceding and following acts of nonsuicidal self-injury in bulimia nervosa patients. Behavior Research and Therapy, 47(1), 83–87.

Mynard, H., & Joseph, S. (2000). Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior, 26, 169–178.

Nelson, R. E., & Crawford, B. (1990). Suicide among elementary school-aged children. Elementary School Guidance Counsel, 25, 123–128.

Nock, M. K. (Ed.). (2009a). Understanding nonsuicidal self-injury: Origins, assessment and treatment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Nock, M. K. (2009b). Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and function of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 78–83.

Nock, M. K. (2010). Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 339–363.

Nock, M. K., Joiner, T. E., Gordon, K. H., Lloyd-Richardson, E., & Prinstein, M. J. (2006). Non- suicidal self-injury among adolescents: diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research, 144, 65–72.

Nock, M. K., Guilherme, B., Bromet, E. J., Cha, C. B., Kessler, R. C., & Lee, S. (2008). Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews, 30, 133–154.

Perkins, D. F., & Hartless, G. (2002). An ecological risk-factor examination of suicidal ideation and behavior of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 17, 3–26.

Plener, P. L., Libal, G., Keller, F., Fegert, J. M., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2009). An international comparison of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) and suicide attempts: Germany and the USA. Psychological Medicine, 39, 1549–1558.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Prinstein, M. J., Boergers, J., Spirito, A., Todd, L., & Grapentine, W. L. (2000). Peer functioning, family dysfunction, and psychological symptoms in a risk factor model for adolescent inpatients’ suicidal ideation severity. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29(3), 392–405.

Prinstein, M. J., Boergers, J., & Spirito, A. (2001). Adolescents’ and their friends’ health-risk behavior: factors that alter or add to peer influence. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 26, 287–298.

Prinstein, M. J., Heilbron, N., Guerry, J. D., Franklin, J. C., Rancourt, D., Simon, V., & Spirito, A. (2010). Peer influence and nonsuicidal self-injury: longitudinal results in community and clinically referred adolescent samples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 38(5), 669–682.

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 98–131.

Ross, S., & Heath, N. (2002). A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 67–77.

Sandstrom, M. J., & Cillessen, A. H. N. (2003). Sociometric status and children’s peer experiences: use of the daily diary method. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 49, 427–452.

Seymour, K. E., Chronis-Tuscano, A., Halldorsdottir, T., Stupica, B., Owens, K., & Sacks, T. (2012). Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between ADHD and depressive symptoms in youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(4), 595–606.

Shaffer, D., Fisher, P., Lucas, C. P., Dulcan, M. K., & Schwab-Stone, M. E. (2000). NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children, version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 28–38.

Shaffer, D., Scott, M., Wilcox, H., Maslow, C., Hicks, R., Lucas, C. P., & Greewald, S. (2004). The Columbia suicide screen: validity and reliability of a screen for youth suicide and depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(1), 71–79.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445.

Storey, P., Hurry, J., Jowitt, S., Owens, D., & House, A. (2005). Supporting young people who repeatedly self-harm. Perspectives in Public Health, 125(2), 71–75.

Swanson, J.M. (1992). Assessment and treatment of ADD students. Irvine, CA: K.C. Press.

Swanson, E. N., Owens, E. B., & Hinshaw, S. P. (2014). Pathways to self-harmful behaviors in young women with and without ADHD: a longitudinal examination of mediating factors. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 505–515.

Vanderlinden, J., & Vandereycken, W. (1997). Trauma, dissociation, and impulse decontrol in eating disorders. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel.

Verbruggen, F., & Logan, G. D. (2008). Response inhibition in the stop-signal paradigm. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12(11), 418–424.

Wechsler, D. (1991). Manual for the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (3rd ed.). New York: Psychological Corporation/Harcourt Brace.

Whitlock, J. L., Eckenrode, J., & Silverman, D. (2006). Self-injurious behaviors in a college population. Pediatrics, 117(6), 1939–1948.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship 2013172086, awarded to Jocelyn I. Meza, and by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01 MH45064, awarded to Stephen P. Hinshaw. We would also like to thank the young women who have participated in our ongoing investigation, and our graduate students, staff, and research assistants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meza, J.I., Owens, E.B. & Hinshaw, S.P. Response Inhibition, Peer Preference and Victimization, and Self-Harm: Longitudinal Associations in Young Adult Women with and without ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol 44, 323–334 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0036-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0036-5