Abstract

Reactive arthritis, previously known as Reiter’s Syndrome or Disease was a post-dysenteric, asymmetrical acute large joint polyarthritis, with fever, conjunctivitis, iritis, purulent urethral discharge, rash and penile soft tissue swelling. Although the eponym was given to Hans Reiter, various forms of the condition have been recorded in history a few hundred years before Reiter. Two French doctors, Noel Fiessinger (1881–1946) and Edgar Leroy (d. 1965), presented a paper at la Societe des Hopitaux-in Paris on the 8th December 1916 on dysentery in 80 soldiers on the Somme, and four of whom developed a "syndrome conjunctivo-uretro-synovial". Their paper was given 4 days before Reiter’s presentation on 12th December 1916 at the Society of Medicine in Berlin, on a German army officer with an illness similar to those described by Fiessinger and Edgar Leroy. It is documented that Hans Reiter was one of a number of University professors who signed an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler in 1932. For socio-ethical reasons and for clinical utility, Reiter’s syndrome is now known as reactive arthritis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This original article was written by the late Professor WW Buchanan and W F Kean (WFK) in 2004 but was not published. WFK and colleague D MacPherson had previously written on the history, clinical features and management of Reiter’s Syndrome (Kean and MacPherson 1991).

Reactive Arthritis

In 1973, Kimmo Aho and his Finnish colleagues introduced the term "Reactive Arthritis" (Aho et al. 1973) for non-purulent sterile joint inflammation associated with sexually acquired Chlamydia trachomatis urethritis or following dysentery due to a variety of organisms, including Salmonella typhimurium, Shigella flexneri, Yersinia enterocolytica and Campylobacter jejuni. A list of organisms implicated in the causation of reactive arthritis is summarised in Table I. A detailed account of the original descriptions of Reactive Arthritis has been given by Iglesias-Gammara et al. (2005). Arthritis associated with urethritis was described in the sixteenth century by Pieter van Foreest (Forestus) (1522–1597) (van Foreest 2003):and following dysentery by Pierre Martin de la Martiniere (1634–1690) in the seventeenth century (de la Martiniere 1664); and later by others in the eighteenth century (Bazy-Lestrade and Caroit 1986; Iglesias-Gammara et al. 2005). Whether the Urethritis described by van Foreest (van Foreest 2003) was due to gonorrhoea is uncertain, since the organism was only discovered by Albert Ludwig Siegmund Neisser (1855–1916) in 1879 (Neisser 1879). Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie (1783–1862) described patients in 1818 who had the triad of purulent urethral discharge, purulent conjunctivitis and arthritis, particularly involving the knees, ankles and feet (Brodie1818; Buchanan 2003). Some of the patients developed an iritis, and one had a rash which may have been circinate balanitis. Several patients suffered from recurrent relapses which could have been the result of further attacks of gonorrhoea or infection with Chlamydia trachomatis (Csonka 1960). In the absence of laboratory tests for these organisms the diagnosis must however remain uncertain. Markwald in 1904 (Markwald 1904) and Singer in 1916 (Singer 1916) reported patients with the triad of purulent conjunctivitis sicca, purulent urethritis, and arthritis, in whom they were unable to identify the gonococcus or any other pathogen. However, it was later during the first world war in 1916 that the definitive descriptions of Reactive Arthritis were made. The first was by two French doctors, Noel Fiessinger (1881–1946) and Edgar Leroy (d. 1965), who published a 40 page review of dysentery affecting 80 soldiers on the Somme, four of whom developed what the authors described as a "syndrome conjunctivo-uretro-synovial" (Fiessinger and Leroy 1916). They presented their paper at la Societe des Hopitaux-in Paris on the 8th December 1916 (Bazy-Lestrade and Caroit 1986). Four days later on 12th December at the Society of Medicine in Berlin, Hans Conrad Julius Reiter (1881–1968) who was serving with the First Hungarian Army in the Balkans, described a German army officer (Reiter 1916; Benedek 1969; Iglesias-Gammara et al. 2005) with an illness similar to those described in French soldiers by Fiessinger and Leroy (Fiessinger and Leroy 1916). These papers in French and German are of historical importance and were not originally translated into English as indicated in Ralph H. Major's Classic Descriptions of Disease with Biographical Sketches of the Authors (Major 1932). Fiessinger and Leroy's description occupies only three short paragraphs in their 40 page manuscript (Fiessinger and Leroy 1916). Reiter's paper is more frequently cited than that of the French authors, but seems rarely to have been read, since several reviews have cited two patients and attributed the onset to a sexually acquired infection. An English translation of the German is presented in Table II (Reiter 1916; Iglesias-Gammara et al. 2005). Reiter attributed the condition to infection with the Spirochaete forans obtained from a blood culture. A second article by Reiter the following year again gave a description of the spirochaete (Reiter 1917). The finding, however, was never confirmed and now regarded as an artefact. Reiter it should be noted had previously participated in research on the causative agent in Weil's disease, which re-proved to be due to the spirochaete, leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae (Hubener and Reiter 1915). Reiter may have been influenced by his previous discovery of a spirochaetal cause of Weil's disease: a case of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe' s famous dictum: “was man weiss, man sieht” (what one knows, one sees). One of us (W.W.B.) wrote to Reiter in the 1960's and received a prompt reply and list of all publications on "my" disease. Noteworthy was the absence of Fiessinger and Leroy's paper, or any other publication antedating his own. In 1937, Postma in Holland popularized the term "Reiter's Disease" (Postma 1937) which, however, was still referred to in France as the Fiessinger−Leroy syndrome. But why was Reiter's eponym widely accepted and not that of Fiessinger and Leroy? The reason is due to the fact that Reiter continued his interest and to publish reports, whereas Fiessinger and Leroy made no further contributions to the literature. Noel Fiessinger became Professor of Medicine at L'Hotel Dieu in Paris, while Edgar Leroy became a psychiatrist at the asylum of Saint-Remy-de-Provence, where Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) had previously been a patient. During the Second World War a number of authors described post-dysenteric reactive arthritis (Bazy-Lestrade and Caroit 1986). The first extensive study was reported by Ilmari Paronen and his colleagues in Finland (Paronen 1948; Sairanen et al. 1969; Kean and MacPherson D 1991). Amongst 150,000 soldiers fighting the Russians in the Karelian Isthmus who developed dysentery due to Shigella flexneri: 344 soldiers, (0.2%), developed Reiter's Disease. However, despite an extensive European literature the disease was not reported in the United States until 1942, when Bauer and Engleman (Bauer and Engleman 1942) described 6 patients and attributed the cause to pleuro-pneumonia-like organisms (PPLO). Noer (Noer 1966; Kean and MacPherson D 1991) in Little Rock, Arkansas, USA, reported 602 of 1276 US sailors who contracted salmonella dysentery after a picnic: 9 of the sailors developed the syndrome of Reactive Arthritis. The concept of a venereal origin of Reactive Arthritis took much longer to establish, despite the fact that Chlamydial organisms had been identified as far back as 1903 (Coste et al. 1952, 1953). Gradually it became apparent that infection with Chlamydia trachomatis of venereal origin was another cause of Reactive Arthritis (Bazy-Lestrade and Caroit 1986; Coste et al. 1963; Amor et al. 1972; Smith et al. 1973; Ford 1953; Kean and MacPherson D 1991). Chlamydia infections in animals, such as sheep and cows, have also been noted to result in chronic arthritis, conjunctivitis, bowel infection, orchitis and epididymitis (Milon et al. 1983). The clearest evidence that there was a form of Reactive Arthritis quite distinct from gonorrhoea came from a studies in venereal disease clinics in London, England in 1953 and 1958 (Ford 1953; Csonka 1958). In Csonka’s study, 67 of the patients with gonorrhoea, the gonococci disappeared with penicillin therapy, but urethritis and other features of Reiter's syndrome persisted. This suggested that another organism was involved, and led to the conclusion that it was Chlamydia trachomatis (Csonka 1958).

Patients were described with a hyperkeratotic skin eruption complicating an arthritis attributed to gonorrhoea. A French dermatologist named the condition keratodermia blenorrhagica (i.e. horny skin with urethral discharge) (Vidal 1893; Chauffard 1897). Blenorrhagia was an early synonym of gonorrhoea. In 1939 Kuske (Kuske 1939) in Switzerland proposed that keratoderma blenorrhagica associated with Reiter's Disease was not due to gonococcal infection. Despite this, a major American textbook on diseases of the skin in 1956 still considered keratoderma blenorrhagica, but not Reiter's Disease, was due to gonococcal infection (Sutton 1956). This complication is now recognised as a complication of Reiter's Syndrome (Maxwell et al. 1966; Kean and MacPherson 1991). The clinical features of post-dysentery and sexually acquired reactive arthritis are identical (Keat and Arnett 1998; Kean and MacPherson 1991). However, the latter is almost exclusive to males, as is keratoderma blenorrhagica (Vidal 1893; Chauffard 1897; Boyle and Buchanan1971; Kean and MacPherson 1991). In most forms of Reactive Arthritis the knee joints are usually and often the first to be involved (Boyle and Buchanan 1971; Kean and MacPherson 1991). The arthritis is often associated with severe pain, the overlying skin becoming red (Boyle and Buchanan 1971; Kean and MacPherson 1991). Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory analgesics are often unable to relieve the pain, which may require corticosteroid therapy Boyle and Buchanan 1971; Kean and MacPherson 1991). Antibiotics are of no value for Reactive Arthritis.

Gounelle and Marche (1941) appear to have been the first to describe sacro-iliitis and ankylosing spondylitis developing in patients with Reactive Arthritis, which Marche confirmed in later papers in 1950 (Marche 1950) and 1954 (Marche 1954). In 1947 Marche and Coste described the association with iridocyclitis (Marche and Coste cited Cited by Bazy-Lestrade and Caroit 1986). Sairanen and his colleagues in 1969 (Sairanen et al. 1969; Kean and MacPherson 1991) reviewed 100 of the 344 patients who had developed post-dysenteric reactive arthritis, reported earlier in 1948 by Paronen (Paronen1948; Kean and MacPherson 1991), and found ankylosing spondylitis had developed in 23 people. In the acute illness of Reactive Arthritis (Keat and Arnett 1998; Kean and MacPherson 1991), patients may develop pericarditis, varying degrees of heart block and aortic incompetence (Boyle and Buchanan 1971; Good 1974; Kean and MacPherson 1991). Central nervous system and other organ involvement has been reported (Boyle and Buchanan 1971; Good 1974; Kean and MacPherson 1991). Prostatitis is almost an invariable accompaniment, but only rarely have prostatic abscesses been reported (Boyle and Buchanan 1971; Kean and MacPherson 1991). A haemorrhagic or mucoid cystitis may develop in severe cases, and acute glomerulonephritis has been described (Boyle and Buchanan 1971; Kean and MacPherson 1991). A urethral stricture may develop in the later stages of the disease (Boyle and Buchanan 1971; Kean and MacPherson 1991). Recurrences are common especially following re-infection with Chlamydia trachomatis (Kean and MacPherson 1991). The use of a condom can help prevent the likelihood of such recurrences.

In the early 1970's patients with Reactive Arthritis were found to have a high prevalence of HLA-B27 (Brewerton et al. 1973). This is present in 8% of healthy Caucasians but is rare in Africans (Al-Jarallah et al. 1993). Up to 90% of patients with reactive arthritis have been reported to be HLA-B27 positive (Al-Jarallah et al. 1993). Using fluorescent monoclonal antibodies, electron microscopy and/or molecular probes fragments of Chlamydia trachomatis, Yersinia enterocolitica, and Salmonella typhimurium have been identified in synovial tissue which could provoke an inflammatory response (Nanagara et al. 1995; Toivanen 2001). It is of interest that all of the bacteria responsible for reactive arthritis are gram-negative facultative or obligate intracellular organisms, thus, enabling them to enter cells, and survive, and even multiply, so that antibiotic therapy is ineffective Sieper and Braun 1995; Toivanen 2001). The exact molecular role of HLA-B27 in the pathogenesis of reactive arthritis has not been defined, but is clearly complex probably involving molecular mimicry and autoimmunity or both (Bragado et al. 1990; Stieglitz and Lipsky 1993; Tsuchiya et al. 1990; Inman et al. 2000). T Cells play an important role, as shown from studies in transgenic rats (Breban et al. 1996), and on cytotoxic T cells (Geczy et al. 1986). However it is also shown that it is HLA-B27 and not some closely linked gene which is involved (Geczy et al. 1986; Bragado et al. 1990; Tsuchiya et al. 1990; Stieglitz and Lipsky 1993; Inman et al. 2000).

Patients who are severely immunocompromised with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) can develop Reactive Arthritis, suggesting a possible role of CD8 + (cytotoxic or suppressor) T lymphocytes (Winchester et al. 1987; Cush and Lipsky 1993; Kean and MacPherson 1991; Schwartz 1997. It has been identified that patients with AIDS and Reactive Arthritis have increased severity and degree of joint pain not responsive to standard analgesics like non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Winchester et al. 1987; Forster et al. 1988; Kean and MacPherson 1991).

Hans Reiter's Tainted Legacy: Statement by Professor W Watson Buchanan 2004.

Hans Reiter had a distinguished career in medicine, and received many awards including the Robert Koch medal, the Great Medal of Honour of the Red Cross, and affiliate member of the Royal Society of London. As an octogenarian he received a signal mark of honour when he was invited to present a keynote address at the International Congress on Rheumatism in Rome in 1961, in which he said:

"In the field of rheumatology, which overlaps with the so-called Reiter's disease, dermatology and venereology, we have not found the real solution. We must avoid any limitation of our scientific thinking…if we really want to help the sick people" (Gerhard and Heights 1970).

Reiter was one of a number of University professors who signed an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler in 1932 (Keitel 2004; Iglesias-Gammara et al. 2005). He was appointed president of the Reich Health Office and proclaimed that amongst his goals was "to ensure that inferior genetic material will be excluded from further transmission" (Wallace and Weisman 2000). Reiter must have been aware of the Nazi programme during the 1930's of sterilisation and euthanasia of the mentally retarded, and of the experiments carried out on concentration prisoners (Iglesias-Gammara et al. 2005), although he stoutly denied this at the Nuremberg trial 57 (Wallace and Weisman 2003). Although found not guilty by the court it is worth noting that he had been made an honorary member of the SS (Zaller 2003). It remains an ethical dilemma whether Reiter's eponym should be abolished in view of his tainted legacy of support of national socialism (Gottlieb and Altman 2003; Gross 2003; Panush et al. 2003; Iglesias-Gammara et al. 2005).

Comment by KD Rainsford, Colin A Kean and Walter F Kean

This original article was written by the late Professor WW Buchanan and W F Kean (WFK) in 2004 but was not published. WFK and colleague D MacPherson had previously written on the history, clinical features and management of Reiter’s Syndrome (Kean and MacPherson (1991). Readers are encouraged to search the article by Keat (1983) on the clinical features of Reactive Arthritis: and the article by Iglesias-Gammara et al. (2005) to review further detail on the history and clinical issues of Reactive Arthritis and Hans Reiter’s original descriptions.

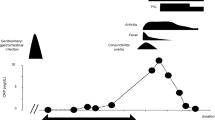

For historical clinical reasons and socio-ethical reasons, Reiter’s Syndrome is now known as Reactive Arthritis. It classically occurs after a genito-urinary or gastrointestinal infection in genetically predisposed individuals (Brewerton et al. 1973; Kean and MacPherson 1991). It is most common in the 20–50 year age group. The acute form is characterised by a large joint asymmetrical polyarthritis and sometimes spinal involvement. The chronic form has a similar pattern (Kean and MacPherson 1991). The treatment of the acute form is with topical and oral NSAIDs, and selected corticosteroid injections: the chronic form is managed by education, exercises, Physiotherapy, NSAIDs, selected corticosteroid injections and Biologic agents (NICE UK 2021).

Data availability

The reference NICE 2021 provides all the advice on treatments stated.

References

Aho K, Ahvonen P, Lassus A et al (1973) HL-A27 in reactive arthritis. Lancet 2:157

Al-Jarallah K, Singal DP, Buchanan WW (1993) Human leucocyte antigens (HLA) and rheumatic disease: HLA Class I antigen-associated diseases. Inflammopharmacology 2:37–45

Amor B, Kahan A, Lecocq F, Delbarre F (1972) Le test de transformation lymphoblastique par les antigens bedsoniens (TTL bedsonien). Son inter& nosologique et diagnostique dans le syndrome de Fiessinger-Leroy-Reiter. Rev Rhum 39:671–676

Bauer WE, E.P. (1942) A syndrome of unknown etiology characterized by urethritis, conjunctivitis, and arthritis (so-called Reiter’s disease) Trans. Assoc Am Phys 57:307–313

Bazy-Lestrade M, Caroit M (1986) History of the Fiessinger–Leroy–Reiter syndrome. Rev Rheum Mal Osteoartic 53(7–9):493–499

Benedek TG (1969) The first reports of Dr. Hans Reiter on Reiter’s disease. J Alb Einstein Med Cent 17:100–105

Boyle JA, Buchanan WW (1971) Clinical rheumatology. Oxford Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford

Bragado R, Lauzurica P, Lopez D, Lopez de Castro JA (1990) T cell receptor VB-gene usage in a human alloreactive response. Shared structural features among HLA-B27 specific T cell clones. J Exp Med 171:1189–1204

Breban M, Fernandez-Sueiro JL, Richardson JA et al (1996) T cells but not thymic exposure to HLA-B27 are required for the inflammatory disease of HLA-B27 transgenic rats. Immunology 256:794–803

Brewerton DA, Caffrey M, Nicholls A et al (1973) Reiter’s disease and HL-A27. Lancet 2:996–998

Brodie BC Sir (1818) Pathological and surgical observations on diseases of the joints. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, London, pp 54–63 (Reprinted by The Classics of Medicine Library. Division of Gryphon Editions Inc. Birmingham, Alabama, USA, 1989)

Buchanan WW (2003) Sir Benjamin Collins Brodie (1783–1862). Heberden historical series. Rheumatology 42:689–691

Chauffard MA (1897) Infection blennorhagique grave, avec production cornees de la peau. Soc Med Hop De Paris 14:569–579

Coste F, Bourel M, Siboulet A (1953) Role of certain microorganisms in rheumatology. Sem Hop 29(69):3546–3554

Coste F, Delbarre F, Amor B (1963) Que reste-t-il des arthritis gonococciques. Rev Prac Paris 13:3715–3730

Coste F, Bourel M, Siboulet A (1952) Role de certains ultragermes dans les affections rheumatismales. Spondylarthrite ankylosante et chlamydozoacees. Rev Rhum 19:765–788

Csonka GW (1958) The course of Reiter’s syndrome. Br Med J 1(5079):1088–1090

Csonka CW (1960) Recurrent attacks of Reiter’s syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 4:164–169

Cush JJ, Lipsky PE (1993) Reiter’s syndrome and reactive arthritis. In: McCarty DJ, Koopman WJ (eds) Arthritis and allied conditions, vol 1, 12th edn. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia, pp 1061–1072

Fiessinger N, Leroy E (1916) Contribution `a. l’etude d’une epidemie de dysenterie dans la Somme (juillet-octobre1916). Bull Soc Med Hop Paris 40:2030–2069

Ford DK (1953) Natural history of arthritis following venereal urethritis. Ann Rheum Dis 12(3):177–197

Forster SM, Seifert MH, Keat AC, Rowe IF, Thomas BJ, Taylor-Robinson D, Pinching AJ, Harris JRW (1988) Inflammatory joint disease and human immune deficiency syndrome. Br Med J 296:1625–1627

Geczy AF, McGuigan LE, Sullivan JS, Edmonds JP (1986) Cytotoxic T lymphocytes against disease-associated determinant(s) in ankylosing spondylitis. J Exp Med 164:932–937

Gerhard B, Heights S (1970) Hans Reiter Letter. J Am Med Assoc 212:522

Good AE (1974) Reiter’s disease: a review with special attention to cardiovascular and neurologic sequellae. Semin Arthr Rheum 3:253–286

Gottlieb NL, Altman RD (2003) An ethical dilemma in rheumatology: should the eponym Reiter’s syndrome be discarded? Semin Arthritis Rheum 32:207

Gounelle H, Marche J (1941) La maladie rhumatismale post-dysenterique. Rev Rhum 8:355–401, 415–465

Gross HS (2003) Changing the name of Reiter’s syndrome: a psychiatric perspective. Semin Arthritis Rheum 32:242–243

Hubener EA, Reiter HS (1915) Beitrage zur Actiologie der Weilschen Krankheit. Deutsche Med Wochenschr 41:1275–1277

Iglesias-Gammara A, Restrepo JF, Valle R, Matteson EL (2005) A Brief History of Stoll–Brodie–Fiessinger–Leroy Syndrome (Reiter’s Syndrome) and reactive arthritis with a translation of Reiter’s Original 1916 Article into English Current Rheumatology. Reviews 1:71–79

Inman RD, Whittum-Hudson JA, Schumacher HR, Hudson AP (2000) Chlamydia and associated arthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 12(4):254–262

Kean WF, MacPherson DW (1991) Reiter’s syndrome. In: Bellamy N (ed) Prognosis in the rheumatic diseases. Kluwer Academic Publishers, London

Kean WF, MacPherson LW (1991) Reiter’s syndrome. In: Bellamy N (ed) Prognosis in the rheumatic diseases, Chap 8. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, pp 167–192

Keat A (1983) Reiter’s syndrome and reactive arthritis in perspective. N Engl J Med 309(26):1606–1615

Keat ACS, Arnett FC (1998) Spondyloarthropathies. In: Klippel JH, Dieppe PA (eds) Rheumatology, Sect 6, Chapt 10, vol 2, 2nd edn. Mosby International, London, pp 1–2

Keitel W (2004) Hans Reiter and the oculo-urethro-synovical syndrome 3. The unknown Hans Reiter, scientist and national socialism propagandist. Z Rheumatol 63:244–249

Kuske H (1939) Ober die Hauterscheinungen bei Morbus Reiter. Arch Derm Syph 179:58–73

Major RH (1932) Classic descriptions of disease with biographical sketches of the authors. Bailliere, Tindall and Cox, London

Marche J (1950) L’atteinte des articulations sacroiliaques dans le syndrome dit de Reiter. Rev Rhum 17(8):449–451

Marche J (1954) Syndrome de Fiessinger–Leroy–Reiter et spondylarthrite ankylosante. Parentes et place nosologique. Rev Rhum 21:320–328

Marche J, Coste F. Cited by Bazy-Lestrade M, Caroit M (1986) History of the Fiessinger–Leroy–Reiter syndrome. Rev Rheum Mal Osteoartic 53 (7-9):493-499

Markwald A (1904) Ueber seltene Complicationen der Ruhr Z. Klin Med 53:321–325

Martin de la Martiniere P. (1664) Traite de la Maladie Venerienne de ses Cavses et des accidens prouenans du Mercure ou Vif-argent. Paris

Maxwell JD, Greig WR, Boyle JA et al (1966) Reiter’s syndrome and psoriasis. Scott Med J 11:14–18

Milon A, Geral MF, Pellerin JL, Lautier R (1983) les chlamydioses animales. Rev Rhum 50:127–134

Nanagara R, Li F, Beutler A et al (1995) (1995) Alteration of Chlamydia trachomatis biologic behaviour in synovial membranes. Arthritis Rheum 38:1410–1417

Neisser ALS (1879) Ueber eine der Gonorrhoe eigentumliche Micrococcusform. Zbl Med Wiss 17:497–500

NICE UK (2021). https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/reactive-arthritis/. Overview, Symptoms, Treatment. Accessed 1 Aug 2023

Noer HR (1966) An “experimental” epidemic of Reiter’s syndrome. J Am Med Assoc 197:693–698

Panush RS, Paraschiv D, Dorff RE (2003) The tainted legacy of Hans Reiter. Semin Arthritis Rheum 32:231–236

Paronen I (1948) Reiter’s disease—a study of 344 cases observed in Finland. Acta Med Scand 212(Suppl 212):1–112

Postma CA (1937) Case of Reiter’s disease. Acta Dermato Venereol 18:691–695

Reiter H (1916) 1916) Ueber eine bisher unbekannte spirochaeten Infecktion (spirochaetosis arthritica). Dtsche Med Wochenschr 42:1535–1536

Reiter H (1917) Ueber die Spirochaete forans. Zbl Bakteriol 19:176–180

Sairanen E, Paronen I, Mahonen A (1969) Reiter’s syndrome: a follow-up study. Acta Med Scand 185:57–63

Schwartz BD (1997) Structure, function, and genetics of the HLA complex in rheumatic disease. In: Koopman WJ (ed) Arthritis and allied conditions. A textbook of rheumatology 2 Vols, Chap 28, vol 1, 13th edn. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, pp 545–564

Sieper J, Braun J (1995) Pathogenesis of spondyloarthropathies. Persistent bacterial antigen, autoimmunity, or both? Arthritis Rheum 38:1547–1555

Singer cited by Rose CW (1916) Ruhrnachkrankheiten and deren Behandlung mit Anti-dysenterie-serum. Berl Klin Wschr 1916. 646–648

Smith DF, James PG, Schachter J et al (1973) Experimental bedsonial arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 16:21–29

Stieglitz H, Lipsky P (1993) Association between reactive arthritis and antecedent infection with Shigella flexneri carrying a 2-md plasmid and encoding an HLA-B27 mimetic epitope. Arthritis Rheum 36:1387–1391

Sutton RL Jr (1956) Diseases of the skin, 11th edn. CV Mosby Co., St. Louis, pp 301–304

Toivanen A (2001) Bacteria-triggered reactive arthritis, implications for antibacterial treatment. Drugs 61:343–351

Tsuchiya M, Husby G, Williams RC et al (1990) Autoantibodies to HLA-B27 sequence cross react with the hypothetical peptide from the arthritis-associated Shigella plasmid. J Clin Invest 85:1193–1203

van Foreest P (cited by Toivanen A) (2003) Reactive arthritis: clinical features and treatment. In: Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, Weinblatt ME, Weisman MH (eds) Rheumatology, Section 9, 3rd ed, vol 2. Spondyloarthropathies. Mosby, Edinburgh, pp 1233–1240

Vidal E (1893) Eruption generalisee et symetrique de croutes cornees avec des ongles D'origine blennorhagique coincidant avec une polyarthrite de meme nature. Ann Derm et Syph. 3ds. 4:3–11

Wallace DJ, Weisman M (2000) Should a war criminal be rewarded with eponymous distinction? J Rheumatol 6:49–54

Wallace DJ, Weisman MH (2003) The physician Hans Reiter as prisoner of war in Nuremberg: a contextual review of his interrogations (1945–1947). Semin Arthritis Rheum 32:208–230

Winchester R, Bernstein DH, Fischer HD, Enlow R, Soloman G (1987) The co-occurrence of Reiter’s syndrome and acquired immunodeficiency. Ann Intern Med 106:19–26

Zaller R (2003) Hans Reiter and the politics of remembrance. Semin Arthritis Rheum 32:237–241

Funding

The authors received no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

W. Watson Buchanan: Deceased, 28th January 2006.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Buchanan, W.W., Kean, W.F., Rainsford, K.D. et al. Reactive arthritis: the convoluted history of Reiter's disease. Inflammopharmacol 32, 93–99 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-023-01336-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10787-023-01336-4