Abstract

Research regarding the support of career decision-making for international Chinese doctoral research students has been scarce and has assumed the homogeneity of international students. Offering insights to career practitioners, this article investigates the support for career decision-making experienced by international Chinese doctoral research students based in Australia from pre-sojourn up to their preparation for graduation. Arising from a thematic analysis of interviews with ten PhD students across three Australian universities, the findings reveal a desire for learning and career advancement that transcends national borders, underpinned by support that reinforces self-reliance and the formation of virtual and real-life social networks.

Résumé

Soutien à la prise de décisions professionnelles auprès de doctorants chinois en Australie Peu d’études ont été menées sur le soutien aux étudiants internationaux dans la prise de décisions de carrière, et aucune ne s’est intéressée spécifiquement aux doctorants chinois. Cet article étudie le soutien à la prise de décision professionnelle de 10 doctorants chinois dans trois universités australiennes, du pré-séjour à la préparation à l’obtention du diplôme. Les résultats d’une analyse thématique révèlent un désir d’apprentissage et de promotion qui transcende les frontières nationales, étayé par un soutien qui renforce l’autonomie et la formation de réseaux sociaux virtuels et réels. Ces résultats permettent des applications pratiques aux professionnels de la carrière.

Zusammenfasung

Unterstützung bei Karriereentscheidungen von in Australien wohnhaften internationalen chinesischen Doktoranden Forschung zu Berufswahlentscheidungen von internationalen chinesischen Doktoranden gibt es nur wenig, auch wurde diese meist aus der Einheit internationaler Studierender übernommen. Der vorliegende Artikel untersucht die Unterstützung von Karriereentscheidungen von der Vorbereitung des Aufenthalts bis zum Abschluss des Studiums wie sie von internationalen chinesischen Doktorierenden, die in Australien wohnhaft sind, erlebt wird und gibt dabei Einblicke in die Karriere von Praktikern. Basierend auf einer thematischen Analyse aus Interviews mit 10 Doktoranden von 3 australischen Universitäten, zeigen die Ergebnisse den Wunsch auf, zu lernen und beruflich über nationale Grenzen hinaus weiterzukommen, gestützt auf einen Support, der Eigenständigkeit sowie virtuelle und reale Netzwerke stärkt.

Resumen

El apoyo a las decisiones de carrera de los estudiantes chinos que cursan doctorados internacionales con sede en Australia La investigación sobre el apoyo a la toma de decisiones de carrera para los estudiantes chinos de doctorados internacionales ha sido escasa y ha asumido la homogeneidad de los estudiantes internacionales. Este artículo, que ofrece información para los profesionales de la orientanción (career practitioners), investiga el apoyo a la toma de decisiones en la carrera del que gozan los estudiantes chinos de doctorados internacionales con sede en Australia, desde la etapa previa a sus estudios hasta la preparación para su graduación. A partir de un análisis temático de entrevistas a 10 estudiantes de doctorado en tres universidades australianas, los hallazgos revelan un deseo de aprendizaje y perfeccionamiento profesional que trasciende las fronteras nacionales, respaldado por un apoyo que refuerza la autosuficiencia y la creación de redes de contactos sociales, tanto virtuales como en la vida real.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Studies on the career decision-making and support of international students have often been conducted by grouping different cohorts such as undergraduate with postgraduate students, or grouping master’s degree, postgraduate diploma, and doctoral students in the postgraduate cohort (e.g., Cheung & Xu, 2015; Lee & Morrish, 2012; Popadiuk & Arthur, 2014). Similarly, while studies exist regarding the decision-making of international students engaged in doctorate by research (or PhD) programs (e.g., Roh, 2015; Zhou, 2015), studies specific to international Chinese doctoral students and their career support appear scant. However, studying international students as an undifferentiated cohort neglects that, in addition to nationality and cultural differences, undergraduate students may have different support needs compared to postgraduate and especially PhD students.

For example, the PhD is a highly specialised qualification that was traditionally the pathway to academic careers but the dearth of tenured positions across many countries and disciplines in recent times has become a cause for concern (e.g., Auriol, Misu, & Freeman, 2013; Cuthbert & Molla, 2015). Unlike master’s coursework and undergraduate programs that disseminate syllabi to students, the PhD is a bespoke apprenticeship program where the student is mentored by a researcher with the ultimate goal of attaining independent scholarship (Baker, Pifer, & Flemion, 2013; Taylor, 2012). PhD students conceivably begin their studies only if they expect an improvement in their career prospects (e.g., Roh, 2015; Zhou, 2015). Hence, while some experiences such as the initial disorientation associated with relocating abroad are common to most international students, the decision-making experiences and support required by undergraduate students may differ from that of postgraduate students (Arthur & Nunes, 2014), and particularly PhD students.

In sum, research about career decision-making and the need for career support of international students with respect to different nationalities, educational levels, and host countries cannot be generalised but requires the investigation of specific cohorts (Arthur & Nunes, 2014). This article focuses on international Chinese (mainland China and the Special Administrative Region of Hong Kong) students enrolled in a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) program in Australia to address the research question: What support did international Chinese PhD students based in Australia experience when making career decisions? The key findings emphasise support from social networks and self-reliant information collection through the Internet. Literature about supporting international students to make career decisions is reviewed before explicating the study’s qualitative methodology. Following a presentation of the findings, the process of making career decisions and the career support experienced are discussed. Stemming from the discussion, implications for university student support services and career practitioners regarding the nature of career support for potential and existing PhD students are suggested.

Support for career decisions

Career decision-making describes the process of deciding between career choices by setting goals and performing actions such as finding educational pathways to achieve these goals (Lent & Brown, 2013). In relation to international students, Arthur (2008) describes a three-phased career planning process: the first phase concerns investigating educational options and subsequent course enrolment, the second is about adapting to the host country, and the third pertains to deliberating between post-graduation options and transitioning to work. This article focuses on the support experiences underlying the career decision-making process, that is, available support for pre-sojourn educational decisions in the first phase and post-graduation occupational decisions in the third phase (Arthur & Nunes, 2014; Lent & Brown, 2013).

International students need support from pre-sojourn preparation for relocation until post-graduation as they prepare to transition to work (Arthur & Nunes, 2014; Zhou & Todman, 2009). When making career decisions, support in the form of career information is required which involves obtaining unbiased data such as labour market trends and occupational information to inform decisions (Gore, Leuwerke, & Kelly, 2013; Sampson & Osborn, 2015). Career information may be obtained from a variety of sources including career services, the Internet, and social networks (Gore et al., 2013).

In China, career services are called career centres and focus on assisting students with finding employment rather than career planning and guidance (Sun & Yuen, 2012). The introduction in China of career education and career counselling has accelerated within the last decade but efforts to date remain concentrated in universities and large cities (Sun & Yuen, 2012; Zhou, Li, & Gao, 2016). In host countries, international undergraduate and postgraduate (and particularly Chinese) students may under-utilise university student support including career services for cultural reasons such as a lack of awareness about these services (e.g., Russell, Thomson, & Rosenthal, 2008).

Consequently, students interested in pursuing further studies abroad are likely to source information from the Internet such as social media and the websites of universities, educational agents, host governments, and international student associations. Such websites list course prospectuses or offer pre-departure booklets with practical location-specific information such as visa information (e.g., Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2014; Insider Guides, 2017). In addition, English and Chinese language websites targeting international Chinese students also offer advice on making international study choices; for example, blogs written by existing and former students or lecturers (e.g., Drake, 2012; Liuxue Web, 2013) and job banks that list openings and provide job hunting advice (e.g., Postgrad.com, 2013). Although career information is plentiful, international students need to consolidate and evaluate the quality (i.e., trustworthiness) of career information to make their decisions. For instance, some sources of career information may be biased towards certain universities or countries such as that of educational agents affiliated to Australian universities who are paid a commission based on the number of students recruited (Productivity Commission, 2015).

Specific to international Chinese students, several studies agree that social networks provide key inputs for pre-sojourn educational decisions as well as post-graduation stay or return decisions (e.g., Dyer & Lu, 2010; Lee & Morrish, 2012; Liu, 2013). Social networks such as family, friends, and professional connections provide social support to international students for decision-making (e.g., Dyer & Lu, 2010; Lee & Morrish, 2012; Popadiuk & Arthur, 2014). Social support involves providing encouragement and affirmation to reduce the stress of making career decisions such as dispensing information or facilitating linkages with sources of aid (Menzies & Baron, 2014; Niles & Harris-Bowlsbey, 2013).

This article focuses on understanding the career support that was utilised in career decision-making to address the research question: What support did international Chinese PhD students based in Australia experience when making career decisions?

Method

The research explored the transition experiences of international Chinese PhD students based in Australia. The research was informed by social constructionism for its emphasis on the co-construction of knowledge through social interactions (Burr, 2015), because international Chinese PhD students make sense of their social interactions and construct their version of reality throughout their transition experiences. Qualitative methodologies are congruent with social constructionism and were utilised to record their experiences, which represent social phenomena that may be captured through rich and deep description (Burr, 2015; Silverman, 2010).

Participants

After ethics approval was obtained, participants were recruited if they were born in China, had not studied in Australia prior to starting their PhD studies, and were enrolled PhD students. Initial recruitment occurred via convenience sampling of the first author’s social networks but subsequently via snowball sampling by asking existing participants to suggest potential participants. All potential participants were emailed the information sheet, consent form, and a short demographic survey to capture details such as age ranges and disciplines. Participation was strictly voluntary upon return of the signed consent forms. Eventually ten PhD students across three universities in Queensland, Australia participated. Participants comprised five males and five females, and all were unmarried and unaccompanied by family. Eight participants were between the ages of 26 and 30, with one aged between 20 and 25 and another aged between 31 and 35. They were almost equally represented among the first three out of four years of full-time study that international PhD students undergo in Australia, as the final year is often busy with submission and corrections. They were also almost equally distributed across the disciplines of science, engineering, arts and humanities, and social sciences. All names have been anonymised to protect the confidentiality of the participants.

Interview

A semi-structured interview protocol was developed and pre-tested with one international Chinese student to ensure adequate coverage and the comprehensibility of questions. The interview protocol contained seven questions of which three enquired about influences on their career decisions and the support utilised before relocation (e.g., decision factors and evaluation criteria related to PhD study, sources or types of advice and information utilised), one asked about experiences in Australia (e.g., expectations of PhD study, reflections about pre-departure advice and information), and a final three questions enquired about intended post-PhD career plans and the use of support (e.g., decision factors and evaluation criteria related to post-PhD plans, difference between PhD and post-PhD factors and evaluation criteria, sources or types of advice and information to evaluate post-graduation decisions).

Interviews lasted between 60 and 90 minutes and were audio-recorded. The first author interviewed all participants in English, which is the language of PhD study in Australia. Although Mandarin (or Putonghua) is the official spoken language in China, the country is vast and linguistically diverse in terms of regional dialects (Wu, 2014). The interviewer speaks Mandarin as a second language but cannot understand and speak all regional variations. However, participants were permitted to use Mandarin if they wanted to provide richer descriptions than they were able to convey in English, and six of them briefly did so.

Data analysis

Consistent with the social constructionist philosophy underpinning the research, data were analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-stage thematic analysis method to classify data through finding themes that describe patterns of data. Thematic analysis has been employed in qualitative studies involving international student decisions (e.g., Choi & Nieminen, 2013; Yang, Volet, & Mansfield, 2017; Zhou, 2015) due to its compatibility with a range of philosophical positions including social constructionism (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Furthermore, thematic analysis provides a clear structure that can easily be operationalised (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Table 1 summarises the six stages of data analysis in relation to the main outcomes.

The first stage involves preparing the data. The first author transcribed all interviews, and similarly transcribed the Mandarin sentences into Chinese characters before translating them into English. Transcripts were returned to the participants to check accuracy and translations, and the first author clarified further, if necessary. The second stage involves coding and becoming familiar with the data. Transcripts were read and labelled with descriptive codes that succinctly describe text extracts. The codes were examined and repetitive codes were merged (King & Horrocks, 2010), yielding 94 codes. Clean transcripts were then recoded approximately two months later to allow new understanding to surface as not all interpretations would be apparent during the first coding (Braun & Clarke, 2006; King & Horrocks, 2010). To resolve differences between old and new codes, duplicate codes were merged or renamed to yield 69 codes.

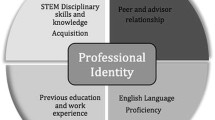

The third stage involves clustering the codes according to patterns called themes, and subsequently depicting relationships between data using mind-mapping (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Firstly, after examining the 69 codes, codes were ranked with some codes becoming subordinate codes if they represented only one aspect of the code. Next, codes with their subordinate codes were clustered into four initial overarching themes generated from the study’s research questions: planning, support sources, personal influences, and environmental influences. Within each initial overarching theme, themes and sub-themes were created to further group codes and their subordinate codes with others that were similar. In the fourth stage, initial overarching themes/themes/sub-themes were reviewed to confirm relationships between them by ensuring that coded text extracts consistently represented similar patterns within each, and distinctiveness between them. After the review, initial overarching themes/themes/sub-themes were moved to more appropriate groups and duplicates were merged. Eventually, three overarching themes (Influences, Experiences, and Support), eight themes and 17 sub-themes emerged. In the fifth stage, each overarching theme/theme/sub-theme was renamed and defined to capture the essence of the contained data. The final stage of reporting produces a coherent account of the analysed data. This article reports on three themes and eight sub-themes related to the overarching theme of Support, as depicted in Figure 1.

Results

The article reports three themes with their constituent sub-themes that address the research question: What support did international Chinese PhD students based in Australia experience when making career decisions? The following themes are reported in turn: the Evolution of Career Directions, Supporting the Preparation for Overseas PhD Studies, and Supporting the Transition to Post-PhD Careers.

Evolution of career directions

Across all participants, this theme illuminates their process of setting career directions and refining goals in light of work and study experiences. The three sub-themes of Forming the Overseas PhD Goal, Evaluating PhD Opportunities, and Reviewing Post-PhD Career Goals are reported below.

Forming the overseas PhD goal

This sub-theme documents the pre-sojourn process of making career decisions across all participants: the inception of ideas, considering future options, and deciding to study for an overseas PhD.

First, all participants started thinking about their potential careers as a result of study or work experiences. For instance, Adam and Mimang thought that their research master’s degree provided a preview of the research process. Pertaining to work experiences, five participants had worked after their undergraduate degrees which shaped their career directions and solidified their resolve to enter a PhD program. For example, Anna remarked that her work experiences confirmed her interest in research: “[The PhD] was always in my mind. … Maybe at the very beginning, it is just a very small thinking, but after you come across many difficulties … it will change you.”

Secondly, considering future options involved finding career directions. Participants had begun their PhD studies due to an interest in research (nine participants), a desire for recognition of their achievements (six participants), or wanting to explore new cultures and learn new knowledge (seven participants). Five participants stressed that potential PhD students should consider their long-term career priorities before starting their studies, such as the desire for high pay or promotions. Other than the time and money invested, more importantly, the PhD was a specialised research qualification. Adam observed that few PhD students had done so and added: “They just have the mentality, ‘We will see, after I got it.’ ”

Thirdly, for nine participants (excluding Anna), studying the overseas PhD was a pathway to furthering their goal of gaining overseas qualifications that were attractive to employers. In contrast, Anna went abroad because she was not qualified for a Chinese PhD program and reflected: “Basically people come out for a better future.”

Evaluating PhD opportunities

This sub-theme documents how most participants formulated evaluation criteria to generate, shortlist, and refine options regarding PhD opportunities. The three criteria that all participants cited were: identifying PhD supervisors or topics that matched their research interests, availability of scholarship funding, and research reputations. The research reputations of supervisors and university research facilities were more important than the university’s worldwide rankings. Several participants explained that reputable professors could access more research funding which would give them more chances to co-publish. Consequently, David shortlisted

the professor and then … the university. … [The PhD decision is] different from the … undergraduate and master’s students who … choose the high reputation universities because after they graduate, they can get very good jobs. … If you can choose both … it’s perfect.

There were also secondary criteria such as the course duration (two participants) or geographical considerations such as studying in English-speaking countries with a mild climate (three participants). In addition, six participants wanted to go to “advanced” (Anna, Timothy), “powerful” (David) and “developed” (Mimang, Jasmine, Susan) countries. Anna explained that she had come to Australia to learn “sophisticated and advanced” research training methods, which Mimang elaborated was a “more systematic training of methodology” not taught in China.

Most participants came to Australia due to the availability of scholarship funding. Several participants noted that their preferred countries—the USA and the UK—had significantly reduced scholarship places in recent times. David had tried to maximise his chances of obtaining a scholarship. He explained that although the USA and UK were his preferred choices: “Only 15 or 20 [Chinese] people can get this [international PhD student] scholarship in one year. It’s highly risky.”

Reviewing post-PhD career goals

Even though most participants had begun the PhD assuming that they would enter a research or academic career, this sub-theme records that as they progressed towards graduation, career directions were refined due to work and study experiences. For example, third year student Susan recollected that she had only one occupational choice after her master’s degree but after working three part-time jobs during her PhD studies, she now had three choices which were “derived from [her] previous experience.” At the time of the interview, participants’ first-choice career options were: conducting research (four participants), consulting (one participant), lecturing (three), or starting a business (two participants). Furthermore, three participants considered returning to China, three thought of remaining in Australia, and another four were intending to move to a third country. Most participants indicated that they would go wherever they could find job opportunities that advanced their careers and furthered their learning.

For six participants across different disciplines, the refinement of career goals involved contributing to society by exploiting a gap, which Adam described as “transfer[ing] academic results or academic outcomes to the industry.” For instance, humanities student Mimang reflected that from his “literature review about the Western way … China really lags behind.” He had found “imperfections” in his industry’s practices and hoped to “share [his] knowledge … [and] help in their professionalisation.” Similarly, engineering student Timothy identified “a gap between the technology in China and the most advanced in the world.” Consequently, four of the six participants thought of starting a business that would concurrently improve their lives.

In summary, the Evolution of Career Directions theme records that the decision-making process across all participants involved formulating career directions with implementable goals and then refining the career directions over time after the input of work and study experiences. The next two themes identify the sources of support for decision-making.

Supporting the preparation for overseas PhD studies

This theme documents the sources and strategies of pre-sojourn support for PhD decisions across all participants in the sub-themes of Social Networks and Comprehensive Research Strategies.

Social networks

Across all participants, the data showed a reliance on social networks outside the family, in school and at work. These networks comprised four groups of people who provided directive, facilitative and emotional support for decision-making: mentors, xuezhang [honorific term for seniors or elders from school or work], peers, and acquaintances.

The first group were mentors who were described as “expert[s]” (Adam). For example, Susan described her master’s supervisor as a “mentor … [or] sifu [great master or teacher with] a deep comprehension of things … who guides [her] thinking and spirit.” For four participants, mentors assumed the role of surrogate parents. For example, Mimang described his master’s supervisor as a “fatherly figure.” Mentors nurtured their protégés by prioritising their interests. To illustrate, Jasmine’s master’s supervisor was also her PhD supervisor in China, and he had urged her to enrol in an Australian PhD because a foreign qualification would improve her career prospects. Further, mentors also proactively planned for them, such as the master’s supervisors of Susan and Jasmine who had arranged for them to meet potential PhD supervisors.

The second group were xuezhang, which eight participants described as “senior or elder” (Adam) classmates from school and university or colleagues who had worked for longer in the industry. Unlike mentors who gave directive support and planned on their behalf, xuezhang were knowledgeable friends who provided encouragement and facilitative help. For instance, the xuezhang of David, Inhye, and Jasmine had been studying in their intended PhD universities and facilitated their information collection process or recommended potential PhD supervisors.

Peers were the third group whom six participants described as friends and classmates from school or university. Peers were a reference point to measure their progress against and also provided emotional support. In the first instance, five participants were influenced by peer pressure to apply for overseas studies, such as Inhye who recalled about her classmates: “If people around me didn’t want to [go for] further studies, maybe I wouldn’t have [made] this decision eventually.” Peers also provided emotional support, as illustrated by Susan whose friends disapproved of her studying an overseas PhD yet she “appreciate[d] [their] care.”

The final group, which five participants described as acquaintances, were friends of people in their social networks. As an illustration, Jasmine’s friend was studying in the UK but in a different faculty from her. He approached friends in her specialisation to obtain information about suitable PhD supervisors on her behalf. She concluded: “Sometimes you need … the network.”

Comprehensive research strategies

While the previous sub-theme examined social networks as one information source, this sub-theme contains other information sources that support decision-making. Also, this sub-theme documents the information collection strategies across all participants and their realisation that not all strategies produced quality information.

All participants had obtained information mainly online due to self-reliance, as Anna commented: “You can only rely on yourself.” Robert elaborated that he preferred to solve problems himself instead of seeking help because: “Maybe they are busy today, you need to wait [until] tomorrow.” Further, Anna commented that most people “don’t know where to start. … [Information is] very scattered.” She classified information to be collected into “informational information” and “practical information.” According to the data, informational information was used to identify potential research topics and supervisors, in addition to global university rankings which Jasmine stated helped in discerning “the quality of the institutions, the supervisors and [the] colleagues.” All participants gathered informational information from diverse online and offline sources including university websites, electronic journal articles, and books. Pertaining to practical information, which the data suggests supplemented their decision-making process, eight participants collected information about the PhD application process and the experience of studying abroad from popular (i.e., social and mass) media such as QQ (Chinese online chat forums) and international Chinese student websites and blogs.

However, eight participants lamented the quality of information collected. To illustrate, five participants urged caution regarding information from popular media which seemed opinion-based and “inaccurate” (David) because reality turned out differently from what had been portrayed. Hence, Robert stressed a need to “filter” online information to identify “trustable” information that “you can trust”. He elaborated: “The university website … it’s ok, but some websites … done by individual people [i.e., blogs], some information is … wrong, so you need to think … and filter” out such information.

Summing up the Supporting the Preparation for Overseas PhD Studies theme, all participants were supported during decision-making by social networks and complemented by the self-reliant collection of information from mainly online sources.

Supporting the transition to post-PhD careers

While the previous theme examined support for the PhD decision, this theme turns to the sources and strategies supporting post-PhD decisions. The sub-themes of Post-PhD Planning Strategies, Insider Support Sources, and Institutionalised Support Sources are each elaborated below.

Post-PhD planning strategies

The data revealed that despite nearly all participants declaring it too early to contemplate post-PhD options, all participants were in fact taking a longer-term view. Several participants were concerned with long-term employment, as Jasmine stated: “Post-doc is just temporary. … You still need to … get a permanent job or tenure.” The two longer-term strategies utilised were remaining open to opportunities and staying relevant.

Exemplified by six participants across the years of PhD study, the first strategy of remaining open to opportunities involved adjusting to new information and planning alternative pathways. First year student Mimang had begun monitoring labour market trends since before commencing his PhD studies and continued to do so while studying in order to “adjust [his] strategy” in relation to post-PhD plans. Fellow first year student Adam would “keep multiple pathways open. … Try not to close doors … because … a lot of things [are] … irreversible.” Adam explained that he planned based on “risk assessment: which scenario has high frequency or consequences and … open up more possibilities.” Similarly, third year student Susan had mapped out three alternative pathways since midway through her studies: university tutoring, exploring business ideas in Australia, and maintaining professional contacts in China. She explained: “All the things … are related to the future. … I don’t have very specific ideas about what I want to do … so … I prepare the three choices.”

The second strategy was staying relevant which, according to seven participants, was an act of “self-making” (Mimang) that involved producing tangible outcomes and ongoing learning. Regarding the former, five participants focused on publishing journal articles. For example, David aimed to publish “high quality papers … in … high impact factor journals” that would make it “easier” to find jobs anywhere in the world. Additionally, in preparation for post-PhD work, four participants intended to attend classroom courses, self-learn from websites and books, or obtain work experience through internships.

While this sub-theme has described strategies to support post-PhD decisions, the next two sub-themes detail information sources that support these strategies.

Insider support sources

Emerging from the data across all participants was that they desired information and advice from “insiders” in intended post-PhD destinations to shape their pathways. Mimang elucidated regarding insiders’ intimate knowledge: “The opinions from the insiders would be way more accurate and to the point than from outsiders.” Insiders comprised three main groups: friends and acquaintances, university supervisors, and employees of intended workplaces.

The first group that six participants would consult were friends and acquaintances to obtain industry or profession-specific information. For instance, Adam thought that his “network … [would] shape [his] way.” He elaborated that PhD graduates in his specialisation were a “minority group … in the university or … society, so the people you can talk with [and] that go through the similar [PhD] process … [are] very limited.” Likewise, Pamela would consult ex-colleagues in industry in different countries and explained: “This … network … gives me the opportunity to see what … people [are] doing in the area.”

The second group that six participants would consult for advice and recommendations were university supervisors from their master’s degree and PhD programs. Four participants stayed in contact with their master’s supervisors, such as Mimang whose former supervisor invited him to collaborate on research projects. Pertaining to PhD supervisors, six participants hoped for advice from and referrals to their PhD supervisors’ professional networks. Susan would also seek out academics in her “academic home” which she described as her “audience … [who were] looking forward to reading [her] papers” for potential collaborations.

The third group that six participants would approach were employees in intended workplaces for workplace insights. For example, Mimang would enquire about “the specifics of their work” and would ask: “How [do] they lead their everyday life? … What did they achieve? What difficulties do they have?” Also, gathering insights such as about collegial rapport were crucial as Inhye explained: “I wouldn’t want to go to a very mean and competitive lab, you feel stressful everyday.”

Institutionalised support sources

While the previous sub-theme considered insider information, this sub-theme examines “outsider” information obtainable from publically accessible support that job-seekers would traditionally utilise. The data on post-PhD decision-making across all participants highlighted two main information sources for facilitative help: career services and mass media.

The first source was career services which consisted of university career services and private-sector employment consultants. Nine participants associated university career services with job advertisements and career workshops. Of the three participants who had utilised the services, Anna and Timothy did not think that the services catered to PhD students. For example, Anna had expected the university to hold “career fair[s] and create job opportunities for their graduates” but was disappointed that the workshops were “too general, no company and no opportunity there, they just talk about … prepar[ing] for your career, how to plan your career.” In contrast, Mimang sought specific help after the workshops: “Most [sessions] don’t focus on PhD students. You have to ask them afterwards specifically about your own situation.” Related to private-sector employment consultants, five participants would obtain information from job banks such as “CareerOne” (Anna) in Australia, an international website called “UniJobs” (Adam), and Chinese-based websites such as “Find-a-Job” (Inhye). They would also visit job markets or fairs.

The second source that seven participants cited was mass media which consisted of news and employer websites. Two participants who were thinking of entering industry would follow news websites to understand broad industry trends and “hot topic[s]” (Adam). All seven would visit employer websites to investigate the workplace.

In sum, the Supporting the Transition to Post-PhD Careers theme revealed that while most participants had yet to start job hunting, they held long-term views of career planning. Also, they wanted to be self-reliant and sought insider information about post-PhD destinations, which was derived primarily from social networks and the Internet.

Discussion

The process of career decision-making is first discussed followed by support for PhD and post-PhD decisions.

Making career decisions

Unlike previous research on international Chinese undergraduate and postgraduate (including doctoral) students that studied pre-sojourn and post-graduation decisions in isolation (e.g., Cheung & Xu, 2015; Dyer & Lu, 2010; Lee & Morrish, 2012; Wu, 2014), this research established that by studying both decisions together, all participants’ educational and occupational decisions showed interrelatedness as the career literature argues (e.g., Lent & Brown, 2013). Most participants’ educational decision to study abroad was a pathway to the occupational decision of obtaining an overseas qualification which they thought would improve their career prospects. Decision-making was an ongoing and iterative process during transitions as most participants developed and refined their career directions. Their transition experiences also produced learning as most participants updated their post-PhD support sources and strategies, such as becoming more discerning about information sourced from popular media.

Compared with Arthur’s (2008) first phase of career planning for international students that relates to the pre-sojourn PhD decision and eventual relocation, this article explicates setting career directions as an additional aspect of career planning that resulted in the decision to study overseas for a PhD. Although most present participants shortlisted countries and universities based on factors similar to international Chinese master’s students such as language of instruction, weather, and university rankings (Wu, 2014), many present participants also considered occupational factors that were aligned with a research-oriented career direction. Consistent with previous research on international doctoral students including Chinese students (Yang et al., 2017; Zhou, 2015), several present participants clarified that an interest in research, their PhD supervisor’s academic reputation, and the availability of scholarship funding were more important than university rankings. A recent Australian study of international Chinese doctoral students explained that in addition to improving career prospects, a Western education might promote self-cultivation through learning from the world’s best researchers and academics (Yang et al., 2017).

Compared with Arthur’s (2008) third phase of career planning regarding the post-graduation decision to remain in the host country or return home, some participants considered a third option of relocating to another country for work, which has not previously been identified in studies examining the post-graduation decisions of international Chinese undergraduate and postgraduate (including doctoral) students (e.g., Cheung & Xu, 2015; Dyer & Lu, 2010) or international students more generally (e.g., Arthur & Nunes, 2014; McGill, 2013; Roh, 2015). However, the present findings agree with several studies in the USA involving international Chinese students from undergraduate to doctoral levels (Cheung & Xu, 2015; Liu, 2013; Roh, 2015) which indicated that stay or return decisions were based on the availability of career advancement opportunities and a chance to practise learnt skills. The present participants might need to move across borders due to the nature of post-doctoral research opportunities which are scattered across the globe (Auriol et al., 2013; She & Wotherspoon, 2013).

Thus, owing to the specialist nature of the PhD qualification, most present participants’ career decisions appear to involve practical motives rather than ideological considerations. Based on Cheung and Xu’s (2015) classification, most participants would either be opportunists who followed the best career advancement opportunities or intellectuals who pursued the highest academic achievements, rather than loyalists who choose to return home merely for the sake of patriotism. Pragmatism led them to situate themselves wherever they could optimise career advancement or learning opportunities, and is similarly visible from their support requirements.

Support

Across all participants’ stated support for PhD and post-PhD decisions, their strategies emphasised self-reliance as they sought help from mostly Internet-based sources and social networks, and only utilised career services as complementary support. Most participants also claimed to avoid thinking about the post-PhD decision till nearer graduation in spite of enacting longer-term strategies. Revealing a lack of systematic support from PhD to post-PhD decisions, the preference for self-reliance is first discussed followed by the apparent delay in preparing for the post-graduation transition.

First, pertaining to self-reliance, several participants may have chosen self-help for practical reasons such as saving time, which explains the appeal of the Internet in providing instant, real-time career information (Bimrose, Kettunen, & Goddard, 2015; Hooley, Hutchinson, & Watts, 2010). The present research is also consistent with previous studies of international undergraduate and postgraduate Chinese students regarding the Internet as an influential source of decision-making information (Wu, 2014; Zhou & Todman, 2009). The research highlights the ubiquity of the Internet in mitigating space and time by connecting them to virtual and real-life networks for career information and social support.

Further, most present participants approached and extended their social networks due to a respect for authority and a distrust of out-group members. In the first instance, Chinese people deeply respect people in authority who hold higher social status such as elders because they have greater access to societal resources compared to those with lower social statuses (Hwang, 2012). As was evident from the participants who consulted their mentors and xuezhang for social support, these elders were perceived to have more life experience and had insider access to professional networks. Although many participants also sought help from strangers with insider knowledge of their disciplines or peers and acquaintances with transition experiences, they seemed less keen to approach university student support. This is aligned with Chinese migrants who are less likely to approach formal support services but prefer to seek help from people whom they trust and consider to be their in-group (Thomas & Yuan, 2010; Ward & Lin, 2010). However, unlike other international undergraduate and postgraduate students from Asia (including China) who under-utilise university student support including career services in home and host countries despite an expressed need for them and awareness of their existence (e.g., Busiol, 2015; Russell et al., 2008), the few present participants who accessed the career services in their Australian universities thought that their needs were not met and implied that the services seemed more catered to undergraduate students who constitute the majority of students in any university (e.g., Lehker & Furlong, 2006; Palmer, 2010).

Secondly, regarding the delay in planning for post-PhD decisions, as mentioned, most participants adjusted their support sources and strategies after learning from their experiences of PhD decision-making. Despite the increasing introduction of career counselling in China over the past decade in educational institutions including universities, the present participants would have studied at a time when career centres primarily focused on job hunting, and also when career decisions were made with the help of respected but non-career trained teachers and based on pragmatic reasons such as the availability of good job opportunities (e.g., Needham, Cao, & Cao, 2008; Sun & Yuen, 2012; Zhou et al., 2016). Consequently, most present participants considered it too early to start investigating post-PhD options because they seemed to equate career planning with job hunting, such as finding job opportunities, reading job listings, attending job markets, or consulting employment agents. The conflation with job hunting is indicative of the unfamiliarity of many Chinese students with concepts such as career planning and career counselling which have been adopted from mostly Western career guidance (Sun & Yuen, 2012; Zhou et al., 2016). As Arthur and Nunes (2014) assert, career services and their work are culturally constructed and may hold little meaning for students such as the present participants who perhaps have had little exposure to them. In fact, the present participants’ delay in planning might explain their under-utilisation of career services in Australia. Another study similarly found that doctoral (including domestic) students delayed their career exploration until nearer graduation and consequently were unclear about the purpose of career services, but realised their value after they had begun to consider post-PhD options (Thiry, Laursen, & Loshbaugh, 2015).

Summing up the discussion, aside from suggestions that international Chinese students may under-utilise student support including career services to make career decisions due to reasons such as the lack of cultural sensitivity, lack of awareness about their purpose, or discomfort with formal support services (e.g., Arthur & Nunes, 2014; Bertram, Poulakis, Elsasser, & Kumar, 2014; Russell et al., 2008), this article argues that most participants were pragmatists who wanted instant career information and were accustomed to obtaining practical support tailored to their needs from trusted social networks. The implications for university student support services and career practitioners are first, in helping this cohort, and international PhD students more generally, to build networks. Peer doctoral and professional networks provide crucial information for exploring post-PhD options (Thiry et al., 2015). University student support including career services already run doctoral seminars and career skills workshops (e.g., Lehker & Furlong, 2006; Thiry et al., 2015), thus promoting such events as networking opportunities might help PhD students to see the value of attending. Furthermore, since most present participants wanted to develop their professional networks while staying open to post-PhD opportunities, international Chinese PhD students may benefit from work experience that provides them with a realistic preview of post-PhD options and builds professional networks. For example, aside from teaching and research assistant work, several Australian universities have begun career initiatives for PhD students that include participation in industry collaborations and internships (Cuthbert & Molla, 2015).

Secondly, to support the cohort’s preference for self-reliance, technological support could be further investigated. Aside from online career guidance programs that are now available in many Chinese and Australian universities (e.g., Cuthbert & Molla, 2015; Sun & Yuen, 2012), the potential of technology including social media and electronic applications to transform career practice has been acknowledged but insufficiently explored with respect to implementation (Bimrose et al., 2015; Bright, 2014). As most present participants continued to consult their social networks in China, Australia, and overseas throughout their transitions, they might benefit from online mentoring by alumni or academics in their host and host countries during pre-sojourn preparation, and as they progress through their PhD studies and contemplate post-PhD options (e.g., Hooley, Hutchinson, & Neary, 2015).

Conclusion

The article identified the importance of career support commencing before the initial overseas educational decision is made, to the assessment of post-graduation options, and perhaps beyond. This research has two limitations which may represent areas of future research. The first is the use of English as the interview language, which was premised on the ability of participants to write English language theses, since most Australian universities have strict English language entry requirements for doctoral programs (e.g., The University of Queensland, 2017; University of Melbourne, 2016). If translation-related issues are accounted for (e.g., Welch & Piekkari, 2006), interviewing participants in their first language might have produced richer findings. The second limitation concerns researcher positionality. The first author as interviewer had a “fluid insider-outsider positionality” (Katyal & King, 2011, p. 338) as the participants would probably have considered her to be an outsider due to her different nationality, yet also an insider arising from a shared Chinese ancestry and language. Although a common cultural frame of reference may be advantageous in terms of gaining access to participants, the assumed familiarity could also impose interpretive bias (e.g., Katyal & King, 2011; Yang et al., 2017). To mitigate bias, the first author was cognisant of cycling through insider–outsider positions and conducted interviews in a culturally respectful manner through constant reflexivity (Drake, 2010; Lee, 2016). She also consulted with the co-authors during the data collection and analytical process. Thus, further research may involve interviewing in the native language, in addition to extending the study to similar cohorts in other host countries for comparison with the present study.

Other future research opportunities also exist. First, while the present participants were single and unaccompanied by family, studies on international (including Chinese) students have shown that accompanying partners impact the students’ career decisions (e.g., Chen, 2009; Zhang, Smith, Swisher, Fu, & Fogarty, 2011). Future research could investigate how support for international Chinese students accompanied by family might differ from that needed by unmarried or unaccompanied students. Secondly, several studies have implied the inadequacies of university student support including career services for doctoral (including domestic) students as such services have primarily been designed for undergraduate and non-research postgraduate students (e.g., Greene, 2015; Lehker & Furlong, 2006). However, research examining the efficacy and usage of university student support by doctoral students is scarce. To arrest the trend towards the “mainstreaming” (Palmer, 2010, p. 24) of student support services, deeper investigation to identify the specific support needs of PhD domestic students, which may differ from domestic undergraduate and postgraduate students as well as international research students, is similarly needed.

The present findings have shown that career services might need to leverage on technology to provide tailored solutions and help clients to utilise their networking skills (Arthur & Nunes, 2014; Bright, 2014). This involves guiding international Chinese PhD students by appreciating their preference for self-reliance while helping them to identify quality career information and connecting them to virtual and real-life social networks. In sum, supporting the career decision-making of international Chinese PhD students based in Australia should involve supporting their quest for learning and career advancement opportunities that may cross national borders, by engendering self-reliant career planning that will put them in good stead throughout their lives.

References

Arthur, N. (2008). Counseling international students. In P. B. Pedersen, J. G. Draguns, W. J. Lonner, & J. E. Trimble (Eds.), Counseling across cultures (6th ed., pp. 275–290). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Arthur, N., & Nunes, S. (2014). Should I stay or go home? In G. Arulmani, A. J. Bakshi, F. T. Leong & A. G. Watts (Eds.), Handbook of career development: International perspectives (pp. 587–606). New York, NY: Springer.

Auriol, L., Misu, M., & Freeman, R. A. (2013). Careers of doctorate holders: Analysis of labour market and mobility indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Baker, V. L., Pifer, M. J., & Flemion, B. (2013). Process challenges and learning-based interactions in Stage 2 of doctoral education: Implications from two applied social science fields. The Journal of Higher Education, 84(4), 449–476. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.2013.0024.

Bertram, D. M., Poulakis, M., Elsasser, B. S., & Kumar, E. (2014). Social support and acculturation in Chinese international students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 42(2), 107–124. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2014.00048.x.

Bimrose, J., Kettunen, J., & Goddard, T. (2015). ICT—The new frontier? Pushing the boundaries of careers practice. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 43(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2014.975677.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Bright, J. E. H. (2014). If you go down to the woods today you are in for a big surprise: Seeing the wood for the trees in online delivery of career guidance. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 43(1), 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2014.979760.

Burr, V. (2015). Social constructionism (3rd ed.). East Sussex: Routledge.

Busiol, D. (2015). Help-seeking behaviour and attitudes towards counselling: A qualitative study among Hong Kong Chinese University students. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 44(4), 382–401. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2015.1057475.

Chen, L. (2009). Negotiating identity between career and family roles: A study of international graduate students’ wives in the US. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 28(2), 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370902757075.

Cheung, A. C. K., & Xu, L. (2015). To return or not to return: Examining the return intentions of Mainland Chinese students studying at elite universities in the United States. Studies in Higher Education, 40(9), 1605–1624. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.899337.

Choi, S. H.-J., & Nieminen, T. A. (2013). Factors influencing the higher education of international students from Confucian East Asia. Higher Education Research and Development, 32(2), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.673165.

Cuthbert, D., & Molla, T. (2015). PhD crisis discourse: A critical approach to the framing of the problem and some Australian ‘solutions’. Higher Education, 69(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9760-y.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. (2014). On track for Australia pre-departure guidebook: Australia Awards Scholarships. In Australia Awards. https://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Documents/on-track-pre-departure-guidebook.pdf.

Drake, P. (2010). Grasping at methodological understanding: A cautionary tale from insider research. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 33(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437271003597592.

Drake, J. (2012). How to get into a PhD program. Thesis Whisperer. https://thesiswhisperer.com/2012/03/01/how-to-get-into-a-phd-program/.

Dyer, S., & Lu, F. (2010). Chinese-born international students’ transition experiences from study to work in New Zealand. Australian Journal of Career Development, 19(2), 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/103841621001900204.

Gore, P. A. J., Leuwerke, W. C., & Kelly, A. R. (2013). The structure, sources, and uses of occupational information. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 507–535). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Greene, M. (2015). Come hell or high water: Doctoral students’ perceptions on support services and persistence. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 10(1), 501–518. https://doi.org/10.28945/2327.

Hooley, T., Hutchinson, J., & Neary, S. (2015). Ensuring quality in online career mentoring. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 44(1), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2014.1002385.

Hooley, T., Hutchinson, J., & Watts, A. G. (2010). Careering through the Web: The potential of Web 2.0 and 3.0 technologies for career development and career support services. http://derby.openrepository.com/derby/bitstream/10545/198269/1/careering-through-the-web.pdf.

Hwang, K. K. (2012). Foundations of Chinese psychology: Confucian social relations. New York, NY: Springer.

Insider Guides. (2017). Insider Guides: Australia—Chinese edition 2017. Resources. http://insiderguides.com.au/international-student-guides/.

Katyal, K. R., & King, M. E. (2011). ‘Outsiderness’ and ‘insiderness’ in a Confucian society: Complexity of contexts. Comparative Education, 47(3), 327–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2011.586765.

King, N., & Horrocks, C. (2010). Interviews in qualitative research. London: Sage Publications.

Lee, M. (2016). Finding cultural harmony in interviewing: The wisdom of the middle way. International Journal of Research and Method in Education, 39(1), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727x.2015.1019455.

Lee, C., & Morrish, S. C. (2012). Cultural values and higher education choices: Chinese families. Australasian Marketing Journal, 20(1), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ausmj.2011.10.015.

Lehker, T., & Furlong, J. S. (2006). Career services for graduate and professional students. New Directions for Student Services, 115(Fall), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.217.

Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2013). Understanding and facilitating career development in the 21st century. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (2nd ed., pp. 1–26). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Liu, X. (2013). Career concerns of Chinese business students in the United States: A qualitative study. Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 17(3), 61–71. http://www.abacademies.org/articles/aeljvol17no32013.pdf.

Liuxue Web. (2013). Qu auzhou du boshixuewei yao zhuyi de liuxue wenti [Important points to consider regarding PhD studies in Australia]. Studying in Australia. http://aus.liuxue.com/apply/16008.html.

McGill, J. (2013). International student migration: Outcomes and implications. Journal of International Students, 3(2), 167–181. https://jistudents.org/fall-2013-volume-32/.

Menzies, J. L., & Baron, R. (2014). International postgraduate student transition experiences: The importance of student societies and friends. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 51(1), 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.771972.

Needham, T., Cao, Y., & Cao, J. (2008). Career selection and development in the People’s Republic of China: Contemporary challenges. Career Planning and Adult Development Journal, 24(4), 19–34.

Niles, S. G., & Harris-Bowlsbey, J. (2013). Career development interventions in the 21st century (4th ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Palmer, N. (2010). Meeting Australia’s research workforce needs—Consultation paper response. http://www.innovation.gov.au/Research/ResearchWorkforceIssues/Documents/RWSsubmissions/Submission75.pdf.

Popadiuk, N., & Arthur, N. (2014). Key relationships for international student university-to-work transitions. Journal of Career Development, 41(2), 122–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845313481851.

Postgrad.com. (2013). Studying for a PhD: The basics. Postgraduate Advice. http://www.postgrad.com/editorial/advice/phd/the_basics/.

Productivity Commission. (2015). International education services: Research paper. http://www.pc.gov.au/research/completed/international-education/international-education.pdf.

Roh, J.-Y. (2015). What predicts whether foreign doctorate recipients from U.S. institutions stay in the United States: Foreign doctorate recipients in science and engineering fields from 2000 to 2010. Higher Education, 70(1), 105–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9828-8.

Russell, J., Thomson, G., & Rosenthal, D. (2008). International student use of university health and counselling services. Higher Education, 56(1), 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9089-x.

Sampson, J. P., & Osborn, D. S. (2015). Using information and communication technology in delivering career interventions. In P. J. Hartung, M. L. Savickas, & W. B. Walsh (Eds.), APA handbook of career intervention (Vol. 2. Applications, pp. 57–70). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

She, Q., & Wotherspoon, T. (2013). International student mobility and highly skilled migration: A comparative study of Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom. SpringerPlus, 2(132), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-1801-2-132.

Silverman, D. (2010). Doing qualitative research (3rd ed.). London: Safe Publications.

Sun, V. J., & Yuen, M. (2012). Career guidance and counseling for university students in China. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 34(3), 202–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-012-9151-y.

Taylor, S. E. (2012). Changes in doctoral education. International Journal for Researcher Development, 3(2), 118–138. https://doi.org/10.1108/17597511311316973.

The University of Queensland. (2017). UQ research degrees. Graduate School. https://graduate-school.uq.edu.au/uq-research-degrees.

Thiry, H., Laursen, S. L., & Loshbaugh, H. G. (2015). How do I get from here to there? An examination of Ph.D. science students’ career preparation and decision making. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 10(1), 237–256. https://doi.org/10.28945/2280.

Thomas, D. C., & Yuan, L. (2010). Inter-cultural interactions: The Chinese context. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 679–697). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

University of Melbourne. (2016). Information for you. Future Students. http://futurestudents.unimelb.edu.au/info?a=591000.

Ward, C. A., & Lin, E. Y. (2010). 四海為家 There are homes at the four corners of the seas: Acculturation and adaptation of overseas Chinese. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 657–677). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Welch, C., & Piekkari, R. (2006). Crossing language boundaries: Qualitative interviewing in International Business. Management International Review, 46(4), 417–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-006-0099-1.

Wu, Q. (2014). Motivations and decision-making processes of Mainland Chinese students for undertaking master’s programs abroad. Journal of Studies in International Education, 18(5), 426–444. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315313519823.

Yang, Y., Volet, S. E., & Mansfield, C. (2017). Motivations and influences in Chinese international doctoral students’ decision for STEM study abroad. Educational Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2017.1347498.

Zhang, J., Smith, S., Swisher, M., Fu, D., & Fogarty, K. (2011). Gender role disruption and marital satisfaction among wives of Chinese international students in the United States. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41604466.

Zhou, J. (2015). International students’ motivation to pursue and complete a Ph.D. in the U.S. Higher Education, 69(5), 719–733. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9802-5.

Zhou, X., Li, X., & Gao, Y. (2016). Career guidance and counseling in Shanghai, China: 1977 to 2015. The Career Development Quarterly, 64(3), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/cdq.12055.

Zhou, Y., & Todman, J. (2009). Patterns of adaptation of Chinese postgraduate students in the United Kingdom. Journal of Studies in International Education, 13(4), 467–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315308317937.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to recognise and thank Professor Martin Mills at The University of Queensland for his invaluable insights and contribution to advising the doctoral thesis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, M.C.Y., McMahon, M. & Watson, M. Supporting the career decisions of Australian-based international Chinese doctoral students. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance 18, 257–277 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-018-9360-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-018-9360-y