Abstract

Primate research and conservation may inadvertently reproduce neocolonial dynamics when primatologists from affluent, imperialist nations conduct studies in primate habitat countries. Here, we consider how interrogating the positionality of both foreign researchers and range-country collaborators can strengthen primatology. Such consideration may help us to better understand where each member of the collaboration is coming from, both figuratively and literally, and how those situated perceptions shape the research process. Centering the perspectives of the range-country collaborators, whose perspectives are infrequently voiced within the primatology literature, may illuminate challenges in cross-cultural communication and imbalances of knowledge and power. Here, we explore how positionality shapes collaborative research through the narratives of two foreign/range-country collaborator teams doing primate research and conservation in Africa and South America. Our goal is to provide examples that consider the positionalities of range-country collaborators relative to both foreign researchers and local community members, and that serve as models for primate researchers as they consider their own research teams’ positionalities. These narratives highlight how prioritizing the perspectives of range-country and local collaborators when they differ from those of foreign collaborators can strengthen future research and conservation efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“It matters what passports we carry, the color of our skin, our assigned sex, where we work and study, and the language that we speak, because their perceived status is tied to histories of colonial domination and exploitation.” (Baker et al., 2019)

Like other fields involving international ecological and conservation research, primatology originates from a history steeped in colonialism and neocolonialism (Chaudhury & Colla, 2020; Garland, 2008; Haraway, 1989; Jost Robinson & Remis, 2018). As there is renewed interest in recognizing how colonialist and neocolonial structures shape scientific research (Adams et al., 2015; Baker et al., 2019; Chaudhury & Colla, 2020), here we offer one step toward a decolonial primatology. Our goal here is to recognize how this history shapes patterns of engagement between foreign and range-country collaborators in primatology, and to provide a set of examples for considering the positionality, or the situated perspective, that an individual brings to their worldviews (Berger, 2015; Jacobson & Mustafa, 2019; Moon et al., 2019; Pasquini & Olaniyan, 2004).

Academic primatology, like other academic sciences, grew from a scientific culture that privileged primarily white, European, Judeo-Christian, male perspectives (Haraway, 1989). Such perspectives inform theoretical assumptions and research priorities; for example, Euro-American cultural worldviews emphasize a human–animal divide that shape anthropological primate research, which differs from cultures based around Buddhism, Hinduism, and Shintoism, which have a more interconnected view of humans and nature (Haraway, 1989; Radhakrishna & Jamieson, 2018). Although Japanese primatology traditions grew in parallel with North American and European perspectives, and robust regional primatology traditions emerged, the emphasis on English as the language of global science, and predominance of academic primatologists from white, middle-class, English-speaking backgrounds, have disproportionately shaped the practice of primatology (De Waal, 2003; Fuentes, 2011; Haraway, 1989; Setchell & Gordon, 2018). For example, from 2006–2016 records of the International Journal of Primatology, both first-author institutions for submitted manuscripts and reviewer pools were heavily biased toward primatologists from North America and Europe (Setchell & Gordon, 2018).

These factors point to a disproportionate power imbalance within publications of international primatology, which reflect the power differentials present in research teams (Hobaiter et al., 2021; Seidler et al., 2021; Trisos et al., 2021). Recognizing how positionality shapes our research collaborations is crucial when foreign primatologists work with range-country and local collaborators who may be situated in different cultural, economic, linguistic, racial, and/or religious worldviews. The cultural transmission of conducting primatological research can inadvertently reproduce neocolonial frameworks of field science, including ‘parachute science’ wherein scientists from affluent countries travel to less affluent countries to collect data and/or samples and return to their home countries to publish (Barber et al., 2014; Hart et al., 2020). Reliance on funding priorities of primarily white, North American, and European organizations, and a top-down model of foreign scientists acquiring funding and directing international projects may result in lack of inclusion of local communities as full stakeholders (Baker et al., 2019; Chaudhury & Colla, 2020; de Vos, 2020; Garland, 2008; Hart et al., 2020). The practical knowledge of local community members is often not recognized to be as valuable as published research within the scientific literature, which can result in inadequate crediting of field staff, and in the limiting of opportunities for advancing in-country scientists (Hobaiter et al., 2021; Seidler et al., 2021). For example, despite decades of chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) research in East Africa, it was not until the 2000s that the first African woman, Emily Otali, received her PhD studying chimpanzees (Seidler et al., 2021). Although primatologists made strides in pursuing community-based conservation efforts and in training range-country scientists (Brooks et al., 2012; Horwich & Lyon, 2007; Strier, 2000, 2019; Strier & Mendes, 2012), there is regional variation in the extent of these efforts. For example, Brazil has a highly successful tradition of student and scientist training programs led by both Brazilian and foreign primatologists (Mittermeier et al., 2005; Thiago de Melo, 1995), whereas comparable training of African scientists has lagged (Hobaiter et al., 2021). In this introduction, we review how the history of primatology and patterns of neocolonial dynamics shape considerations of positionality.

Historical Perspective

The neocolonialist roots of primatology originate from the broader fields of evolutionary biology and ecology that grew out of projects of colonial exploration. On these surveys, naturalists were helped by locals who had a secondary role in formal science (Antunes et al., 2018, 2019; Moreira, 2002; Urbani, 2017). Although naturalists such as Humboldt, Darwin, Wallace, and Bates were driven by curiosity, these men carried out projects rooted in European imperialism and facilitated by colonial infrastructure (Chaudhury & Colla, 2020; Fagan, 2007; Fuentes, 2021a; 2021b; Sachs, 2003; van Wyhe & Drawhorn, 2015). The resources to complete these trips were based on their utility to colonial exploration and exploitation; the Beagle’s voyage was sponsored by the British government, and Wallace’s access to ports and Indigenous assistants during expeditions were facilitated by colonial networks. Their research originated within a paradigm of white, European supremacy and is often reflected in their scientific work, such as the racist and sexist descriptions in Darwin’s Descent of Man (Fuentes, 2021a; 2021b). For example, Darwin depicted Indigenous people in the Americas and Australia as cognitively inferior to Europeans, thereby providing ammunition for politicians seeking justification for empire-building, colonization, and genocide. Additionally, he asserted that men were intellectually superior to women, and reified the Victorian cultural norms of passive women and intelligent, courageous men as the work of natural selection (Dunsworth, 2021; Fuentes, 2021a; 2021b). These naturalists relied heavily on exploiting local knowledge and labor to collect specimens and document natural history, which is reflected in attitudes toward local people, such as the dismissive use of the term “boy” to refer to adult men who were field assistants (van Wyhe & Drawhorn, 2015). Such dismissive attitudes and entrenched racial hierarchies shaped research expeditions into the 20th century (Haraway, 1989).

During the early phases of natural history research on primates, colonial networks facilitated access to primate field sites and research. Robert Yerkes is often lauded for his roles in establishing the first North American primate research center and supporting primate field studies, yet he was also a well-known eugenicist (Haraway, 1989; Pickren, 2009; Yakushko, 2019). Clarence Ray Carpenter, the most successful of the early primatologists sponsored by Yerkes, is credited as being the father of contemporary field primatology because of his systematic behavioral studies of wild primates. However, his research in Panama and participation in transporting rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) from colonial India to the US territory of Puerto Rico were facilitated by US and British imperialism (Ahuja, 2013; Haraway, 1989; Montgomery, 2005). Similarly, funding and access to fieldwork by iconic primatologists such as Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and others was facilitated by Louis Leakey, whose family were Anglican missionaries in colonial East Africa, and whose paleoanthropological career relied on colonial infrastructure (Rodrigues, 2020; Sutton, 2012).

From these roots, primatology flourished as an international field discipline where scientists from Europe, North America, and Japan travelled to primate-habitat countries across Africa, Central/South America, and Asia (Fedigan & Strum, 1999; Strum & Fedigan, 2000). In this natural history phase, only Japanese primatologists originated from a primate habitat country (Asquith, 2000; Matsuzawa & McGrew, 2008; Takasaki, 2000). Despite thriving regional primatology traditions in Brazil, Mexico, China, Vietnam, and India, the development of these traditions frequently began during later stages of the development of primatology, particularly in the 1960s to1980s (Bicca-Marques, 2003; Bicca-Marques, 2016; Estrada et al., 2006; Fan & Ma, 2018; Hoàng, 2016; Singh et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2021; Strier, 2000, 2017; Urbani, 2017; Yamamota & Alencar, 2000).

Neocolonial Dynamics

As a result of this history, primatology carries the baggage of its colonial origins, which echoes across conservation fields (Chaudhury & Colla, 2020; Garland, 2008). At a broader level, it can be reflected in “fortress conservation” approaches, where local people are excluded or removed (Hart et al., 2020). At its worst, it can result in antagonistic relationships between researchers and local people, as was the case for Fossey’s violent interactions with those suspected of poaching (Rodrigues, 2019). The priorities of foreign conservationists, as well as unforeseen consequences of research activities, can cause or exacerbate conflicts about wildlife. For example, when famed Gombe chimpanzee Frodo killed a local toddler, it raised concerns about human safety, including the risks that well-habituated chimpanzees can pose to local communities, and concerns over the prioritization of internationally well-known wildlife over the welfare and safety of local people (Garland, 2008; Kamenya, 2002). In recent years, essays and interviews from conservation researchers in Africa and Asia address the issues encountered in conservation work. Such perspectives include how colonial science excludes local conservationists from access to funding and infrastructure, and devalues their cultural knowledge and priorities (de Vos, 2020; Gokken, 2018; Mecca, 2020; Nkomo, 2020). Even when conservation organizations work with Indigenous collaborators, differing priorities and cultural understandings can result in Indigenous people feeling the need to selectively perform or conceal information, both to manage the expectations of conservation organizations and to protect their land and livelihoods (Rubis & Theriault, 2020). These dynamics are often subtle and unintentional, but may not be recognized due to enculturated biases; furthermore, they can emerge even from those who consider themselves firmly committed to anti-racist ideals (Deliovsky, 2017; Moon, 1999). These changing perceptions can pave the way for greater awareness of underlying power dynamics as well as recognition of unrecognized biases.

The Importance of Positionality

Personal reflections on positionality may help us to perceive what we were unable to recognize before (Berger, 2015; Moon et al., 2019). Addressing imbalances between foreign and range-country collaborators requires changes at structural and interpersonal levels. At the interpersonal level, effective and respectful communication is facilitated by understanding each other’s positionality. Position includes characteristics such as age, gender, ethnic/racial identity, languages, education, and other personal characteristics that shape the perspective from which an individual engages with others and views the world around them (Baker et al., 2019; Moon et al., 2019; Pasquini & Olaniyan, 2004).

Recognizing that every individual comes from a perspective of situated knowledge allows for greater reflexivity, and a consideration for the experiential knowledge of others (Jacobson & Mustafa, 2019; Moon, 1999; Pasquini & Olaniyan, 2004). Explicitly considering differences of perspectives can enrich our understanding when conducting research across national, cultural, and linguistic boundaries. Here, we define “range-country” primatologists as primatologists from countries within primate-habitat distributions, and “local” primatologists as those from within or nearby a field site. Range-country collaborators may include formally qualified scientists, conservation professionals, local field/research assistants, and other project staff or local stakeholders. Primatologists, both range-country and foreign, play a role in being cultural brokers across a wide range of stakeholders (Anderson-Levitt, 2014; Caretta, 2015).

The perspectives of local and range-country colleagues that are central to conservation and research work are often missing from primatological literature. Here, we present narratives from two collaborative teams from Uganda and Brazil to illustrate dynamics that occur in these international collaborations. These collaborative teams are very different: one is between academic and non-academic collaborators, the other is between two academic collaborators, to provide two differently situated perspectives. Rather than directly comparing them, we use them as a starting point for examining how collaborative relationships vary based on cultural dynamics, positionalities, and relationships. Our aims are: 1) to highlight range-country colleagues’ perspectives in conversations about primate research and conservation and how these perspectives may compare with those of foreign collaborators, 2) to consider the positionality of range-country collaborators, relative to foreign researchers and their local communities, and 3) to provide a set of examples that can serve as guides for primate researchers. By drawing from collaborative teams working in different regions of the world, we hope to provide narratives that can be considered “snapshots” of this process in different contexts. Our hope is that these narratives inspire primatologists to reflect on these dynamics in their own research teams, and to adapt these approaches to the local and regional contexts relevant in their own collaborations.

Methodological Approach

The Value of Narrative

Qualitative data collection methods are ideal for exploring the contextual information pertinent to positionality. Story, meaning, and place are all essential components that a qualitative approach can provide to developing effective conservation science (Moon et al., 2019). Furthermore, counter-storytelling, in which stories of marginalized voices are highlighted to counter dominant narratives, can yield valuable perspectives (Solórzano & Yosso, 2002). Narratives are descriptive accounts in which interlocutors can tell their stories while emphasizing their own constructions of meaning (Sandelowski, 1991; Weller, 2014). Narratives provide a means for individuals to explore how their positionality shapes collaborative relationships, allowing the individual collaborators to each participate in constructing meaning, and emphasizing the importance of place in their research collaborations.

Identification of Research Teams

Our approach to this study was to collect shared narratives from foreign/range-country collaborative teams in Africa and South America. Vicent Kiiza and Matt McLennan work together on the Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project in Uganda. Sérgio Mendes and Karen Strier work together on the Muriqui Project of Caratinga in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Each collaborative team considered a set of questions regarding their positionality and how it shaped their research interactions with each other and members of the local community (Table I) and customized these questions to their particular context and relationships.

Author Positionality

I (first-author MAR) am a cisgender, Asian-American woman. My parents immigrated to the United States from Bombay/Mumbai, India, and I was born in Chicago and raised in the Chicago suburbs. My family is from the East Indian Catholic community, an ethno-religious community shaped by waves of Portuguese and British colonization of the western Indian coast. My interest in understanding collaborative relationships in primatology stems from past experiences conducting fieldwork in Central America and western Africa, and my perspective as an Asian-American within primatology and anthropology. We present positionalities for VK and MRM in Table II, and for SLM and KBS in Table III, in order to present them in conjunction with the narrative sets.

Ethical Note and Data Availability

Since this manuscript was based on personal narratives of the authors, no ethical approvals were required and there is no data to share.

Results

Uganda, East Africa: Matt and Vicent Narratives

Background on Research Site and Collaborative History

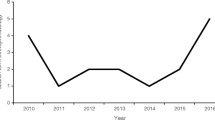

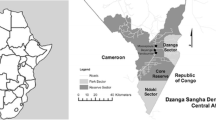

Matt and Vicent work together in the Bulindi Chimpanzee and Community Project (BCCP) in western Uganda. The project studies and conserves eastern chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) living throughout a large (> 1,000 km2), unprotected village landscape, where rapid deforestation has escalated competition between chimpanzees and local residents for space and resources (see McLennan et al., 2020; McLennan et al., 2021; McLennan & Hill, 2012). BCCP combines primatological fieldwork with community-based initiatives including tree planting and livelihood support, which aim to enhance local people’s capacity to accommodate chimpanzees and engage in conservation. While BCCP is directed by Matt and funds are mostly acquired outside Uganda, the 26-strong field team are local to the region and many — including Vicent — are from villages within chimpanzee ranges. Vicent joined BCCP as a paid employee in 2017, tasked initially with gathering information on one group of chimpanzees whose home range includes Vicent’s own village (see McLennan et al., 2021). Besides his role as a ‘Chimpanzee Monitor,’ Vicent is responsible for implementing many of BCCP’s programs in his sub-county. He is normally the first point of contact for community members in his local area in case of concerns or complaints about chimpanzees.

Vicent’s narrative was prepared from his answers to questions asked by Matt in English. Although Uganda is a multilingual country, English was maintained as the country’s official language after independence from the United Kingdom in 1962. The official language in the region where BCCP operates is Runyoro; however, English is widely spoken. Matt collated Vicent’s answers into a narrative, which Vicent checked for accuracy.

Vicent's Narrative

I first became interested in chimpanzees when I was 20 years old. Four came to our garden, which we rented next to a small forest. It was the first time in my life to see an animal looking like a human, and their behavior of slapping the ground while calling increased my interest further. I asked my mother, which animals are those? She said they are chimpanzees (ebiteera). I felt happy and whenever I found them at our garden, I would stop digging and just stay watching them.

Not long after, a Ugandan NGO that promotes conservation and welfare of chimpanzees advertised for local staff on the radio. I applied, and by the grace of God I passed the interview and was employed as a chimpanzee and forest monitor for my sub-county. That was from 2010–2016. In 2017, I met Matt and got a job with BCCP. I was assigned to monitor the chimpanzee group in my local area. Sometimes I moved in the field with Matt, a German student, or a British woman volunteering with the project. Finding out about the chimpanzees is so interesting. By following them, taking photos and videos and studying their faces and characters, we differentiated each individual. From there, it was easy to give them names (we even named one Vicent!). At the end of each month, you can easily say which chimps have been around or who is missing. Now I’m also a project coordinator for my sub-county; I still monitor the chimpanzees, but I also supervise project services in the community, such as water boreholes, energy stoves, and our football league, and I represent BCCP at local government meetings.

Working as a chimpanzee researcher and conservationist has affected my relationships with members of my local community. The changes are both good and bad: it has made me more popular and increased my respect from the community, but it has also created some enmity. The most difficult experience comes when chimpanzees damage crops or property, and especially when a chimp grabs a child. This has happened about five times, including an incident when a 1-year-old child was fatally injured by a chimpanzee (for a review of the contexts of chimpanzee attacks on local persons in Africa including Uganda, see McLennan & Hockings, 2016). When a chimp injures someone, some people hold me responsible because they regard me as a bridge between them and UWA [Uganda Wildlife Authority, the government agency responsible for wildlife management]. They can become angry with me if the authorities don’t take quick action to follow up with the family and recover the medical bills. For example, if a child has received injuries from a chimpanzee and I explain that UWA will refund the medical expenses later, very poor families can’t manage to pay the bills first. When I explain the official procedure to such people, they can end up abusing me.

When community members are angry they may not be in the mood to listen. And since I’m also human, I can also feel angry with them. I first give them time to cool down — a few days or a week or two. Then, they may start looking for me, asking me where I’ve been. So, even if community members turn against me, after a short time the situation starts to normalize. Such challenges make me think harder about how to resolve the issues. We can’t stop the chimpanzees moving around people’s homes and gardens, so we advise them how to increase the safety of their children and what they should and should not do when they meet chimps. In case of serious incidents and complaints, we connect them to UWA. Some community members think that those conserving chimpanzees care more about the animals than people. For example, if a person harms a chimpanzee he or she can be punished; conversely, when the chimpanzees do wrong there is no punishment — they can’t be killed or even translocated. Many local people struggle to understand the value of wildlife like chimpanzees because they don’t see a direct benefit. The chimps attract tourists to Uganda; hence they earn money for the government which goes towards services like health, roads, and education. It can be very difficult for local people to understand. The chimpanzees are protected by the law, they’re an endangered species, and they share most of their genes with humans. Also, we humans are in control of all God’s creatures. The chimpanzees were created before humans, meaning we are responsible for conserving them.

Although I love chimpanzees, I feel bad when they do wrong. But this depends on the cause, such as when people seriously disturb the chimps using dogs to chase them, throwing stones, destroying their habitat, not caring about their lives, and not listening to the advice given; hence chimpanzees end up causing problems in the community. Especially when a chimp attacks a child, I can feel angry with them, but mostly these conflicts are a result of how the community treats chimpanzees; some people treat them so badly they end up misbehaving.

I also get misunderstandings from people who think they are missing out on services from the project, be it a borehole, energy stoves, or the chance to participate in our football league. Because I’m usually the one who moves in the villages and organizes the community to participate in the project, people take me as the person in control, deciding whether someone receives services or not. I try to explain as clearly as I can, that the project grows one step at a time, we are limited by funds and resources, and that not all individuals and villages can benefit at once. But sometimes it’s very hard to make local people understand this point. Moreover, there are some members of the community who are just jealous because I have a job with a salary.

Foreigners come to Uganda to do research on chimpanzees because it’s the only animal which looks and behaves like a human, but it’s found only in some African countries like Uganda. Mzungus [meaning white person in common usage] value wildlife so much, but most of my fellow Ugandans don’t. That’s why someone might say the chimps are for the mzungus. Working with Matt and BCCP has made me love conservation and chimpanzees even more. It has improved my skills in research and monitoring, and in community communication. It has also promoted friendships, both locally and with foreigners who come to Uganda because of chimps. Overall, working with whites has made me more valuable, respectable, and popular in my community. But it has also raised some people’s expectations in terms of how they can benefit from chimpanzees. Actually, people think that because I work with mzungus and they have a lot of money, then I too must have a lot of money. That’s why I’m invited to many functions in the community! There’s high demand for my support for weddings and introductions and church events.

Conserving chimpanzees brings different challenges if you are a local person or a foreigner. For a local man like me it’s very hard to get funding for a project, but it’s easier for a mzungu as they have more weight than a local person in terms of obtaining funds. Foreign primatologists who come to study and conserve chimpanzees can help bring services that also improve people’s health and income. They should take time to be social, attend meetings and share views, and play a part in the community. The biggest challenge for them is that local people have higher expectations of them because they think mzungus have a lot of money and can bring many services. I don’t think that conserving chimpanzees should be for either Ugandans or foreigners only, because conservation has no limit. It’s not about category, whether you are an African or a foreigner — conservation is for all. Responsibility for conserving chimpanzees is both for Africans and foreigners, because we all have roles to play in conservation and come with different experiences and reasons for protecting chimpanzees. People should understand we require joint efforts in conservation.

Matt’s Narrative

As project director, I am formally Vicent’s ‘boss’ and as such our collaboration isn’t an equal one. Even so, we are friends who have bonded over a shared passion for chimpanzees and conservation in Vicent’s home district in western Uganda. Over the past several years, we’ve got to know his local chimpanzees together, spending countless hours tracking them in the field, poring over videos and photos, and learning their habits and individual characters. I have a deep fascination for these great apes: the process of finding out about ‘new’ (unstudied) chimpanzees like Vicent’s group still carries much the same excitement for me as when I first arrived in Uganda as a doctoral student to research ‘village chimpanzees,’ 15 years ago; these early encounters were unexpectedly nerve-racking because of the confrontational behavior shown by adult males, which reflected the familiar but competitive relationship between the apes and some villagers (McLennan & Hill, 2010). While most Ugandans are not animal lovers as westerners often are, they are proud of their country’s rich wildlife, and some local residents express empathy for the chimps. Still, Vicent stands out in his affinity and compassion for these great apes. It’s immensely satisfying for me to get to share my love of chimpanzees with someone as local to the landscape as the animals themselves. Our backgrounds and experiences in our shared work differ in important respects, however (Table II).

I trained in social and biological anthropology as an undergraduate at Durham University (and took sociology at college), before concentrating on primatology at postgraduate level at Oxford Brookes University, where I obtained a PhD under the supervision of Kate Hill. From this background, I was comfortable with interdisciplinary perspectives in research and the idea that scientists are not impartial observers. However, field primatologists are not traditionally encouraged to be overly reflexive as part of our training; positionality is something many of us learn on the job, if we dwell on it much at all. During my doctoral fieldwork, I gained two important insights that I hadn’t given due consideration during my research preparation.

First, foreign primatologists conducting primate studies or implementing conservation initiatives in host cultures are unavoidably ‘social actors’ (Hill & McLennan, 2016; McLennan & Hill, 2013): we influence the human social environment in which we work. While a ‘researcher effect’ is well-known in the social sciences, it is rarely acknowledged in primatology. At times, it can have unpredictable, potentially far-reaching, consequences. In my case, my arrival to study chimpanzees in a village environment where no previous primatological research had been done probably precipitated increased rates of tree felling, as some residents and local officials hurried to profit from local forests, apparently believing their access to timber (and possibly land) might be reduced in the future (McLennan & Hill, 2013).

Second, I became aware of the complex position of locally-employed field staff in their communities, which can be influenced by their involvement with foreign primatologists whose objectives and motives are not always well understood (McLennan & Hill, 2013). In his narrative, Vicent discusses the advantages and disadvantages of being a chimpanzee conservationist in his local area, as well as working with westerners (mzungus). Unlike my role as a British primatologist and conservationist in Uganda, Vicent’s role in our project — a local ‘ambassador’ for chimpanzees and a conservationist who helps bring services to local communities — is intimately entangled with his roles as a friend or neighbor; as a clan, village, or church member; as a local council representative; and so on. The chimpanzees that Vicent champions also impose significant costs on some families, via crop losses and risks to personal safety, but are also associated with ‘benefits’ (i.e., services such as livelihood support, water wells, and sponsorship of schoolchildren). Inevitably, these costs and benefits are not experienced evenly by residents over the large area of human–chimpanzee coexistence regionally (for example, in 2020 BCCP’s programs reached over 50 villages in Vicent’s sub-county alone). I can only imagine the complexities of the social and ‘political’ relationships that Vicent has to navigate in his daily work, with their attendant layers of loyalty and expectation, but he hints at the challenges he sometimes faces in his narrative.

Since my earliest experiences in Uganda, I’ve wrestled with the ethics of promoting conservation of wild chimpanzees that share spaces with people who are generally poor and often powerless, aware that this situation would be unacceptable to many in my own country (McLennan & Hill, 2013). I haven’t fully resolved this personal dilemma. Ultimately, while I believe these remarkable and sentient — albeit troublesome and sometimes dangerous — great apes have a right to existence, this can only be achieved if benefits of coexistence outweigh the costs for local people considerably. I find it reassuring that Ugandans — including most village residents and local leaders — generally support conservation of the chimpanzees and welcome projects that seek solutions, such as ours.

People sometimes joke that I’m a Ugandan now by virtue of the long time I’ve lived and worked here. Nevertheless, in most contexts I’m clearly perceived (and perceive myself) as an outsider. Although I’m British, I’ve never observed any specific resentment towards me about Uganda’s colonial past. Most people are welcoming. If I do detect occasional coolness in my interactions with local people, I imagine it’s because I’m considered responsible for problems people experience with chimpanzees. However, Vicent explains that some villagers are uncomfortable interacting and speaking English with a mzungu — perhaps especially a middle-aged man with presumed power or authority — and avoid smiling or greeting for fear it may be taken as an invitation to interact! At times, however, residents complain to me directly about the chimpanzees, possibly hoping I will offer money as compensation. These days, I rarely attend village meetings about chimpanzees. The project staff are well-experienced and, being from the region themselves, they understand people’s perceptions, priorities and constraints far better than I ever could. Also, my presence (or that of other westerners) can confuse the issues by feeding the common misconception that it’s mainly mzungus who are concerned with chimpanzees and conservation, and — as Vicent points out — it can foster unrealistic expectations about potential ‘benefits’ from engaging with the project.

Like many fieldworkers in foreign cultures (e.g., Pasquini & Olaniyan, 2004), I experience occasional feelings of exclusion or invisibility, such as when collaborators interact with villagers in the local Runyoro language and pay little mind to my efforts to be involved in the discussion. Arguably, this is my fault — I should have taken time to learn more of the language! At times I suspect that information relayed to me about a setback or incident in the villages is selective, perhaps because it’s thought unnecessary — or even undesirable — for me to understand the whole story. But these are minor gripes: I’m extraordinarily privileged to spend my career researching and conserving chimpanzees in Uganda, and I’m proud of what Vicent and the rest of the project team have achieved, as well as my part in it. Ultimately, the future for primate conservation in Uganda is in the hands of Ugandans like Vicent; my involvement with BCCP is likely to be increasingly to provide support from behind the scenes. Still, it’s gratifying that Vicent believes there’s a role for foreign primatologists like me in helping to conserve his country’s wild chimpanzees.

Brazil, South America: Karen and Sérgio Narratives

Background on Research Site and Collaborative History

Our collaboration began informally in 1983, when Karen was a 24-year-old graduate student from Harvard University who had come to Brazil to conduct a 14-month field study for her doctoral dissertation on the critically-endangered northern muriqui (Brachyteles hypoxanthus; previously B. archnoides) in a small, privately-owned forest located on Fazenda Montes Claros near the city of Caratinga in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Sérgio was a 23-year old student from the Universidade de Brasilia, who had come to Fazenda Montes Claros to conduct his Masters dissertation research on the brown howler monkey (Alouatta guariba; previously A. fusca).

During that first intensive year, from June 1983-July 1984, it was mostly just the two of us, along with a local housekeeper/cook and a local handyman who worked at the field station during the days and who we also considered to be our friends. Sérgio helped Karen to practice her Portuguese to the point where we could communicate, and what became a long-term friendship was formed. It was not just the language that Sérgio was teaching. Karen learned about different ways of looking at the world. Some of these differences were ones she would consider to be very Brazilian, such as the closeness of extended families that all lived in close proximity for most of their lives (Sérgio being unusual in his family for having gone away for graduate school and the first in his family to go to university at all). By 2002, Sérgio had launched an original study of the meta-population of northern muriquis in the fragmented landscape of Santa Maria de Jetibá, Espírito Santo, which he ran in parallel to his role as the co-coordinator of the Muriqui Project of Caratinga that Karen had launched with her initial field research in 1983.

Sérgio has been recognized in our research permissions as the official person responsible to the Brazilian government for the Muriqui Project of Caratinga for more than 20 years, navigating the complex bureaucratic minefield involved with renewing Karen’s permission to conduct a “scientific expedition” as a foreigner in Brazil every 2 years. But in addition to all of this, Sérgio has been a true scientific collaborator, being an active participant in all major decisions about the research questions, methods, and protocols. Conversely, Karen has collaborated on various aspects of the Muriqui Project of Espírito Santo that Sérgio leads.

We have co-authored many dozens of scientific presentations and articles, and two popular books based on data and knowledge from both of our muriqui projects (e.g., Strier and Mendes, 2009, Strier & Mendes, 2012; Mendes et al., 2010, 2014). We have held various affiliations at one another’s institutions and have sponsored each other’s students in our respective home countries. We have also stayed at each other’s homes in the USA and in Brazil, and we have gotten to know members of each other’s families and colleagues and friends. Our long-term collaboration is built on a solid foundation of mutual respect and mutual trust that has persisted from the start.

Karen’s Narrative

My affinity with Sérgio can be traced to the coincidental timing of our field studies of northern muriquis and brown howler monkeys respectively. These were initiated at the same time, at the same remote field site during a time before cell phones and wi-fi, when there were no expectations that we would be attending to news or messages from home. I have thus also always considered us to be professional and age peers, even though we made the transition from being students to becoming professors to assuming different leadership responsibilities at different times.

Although my involvement with muriquis and this field site has been continuous since my first visit there in 1982, Sérgio went on to work on other species after his howler monkey research. Nonetheless, we kept in touch over the years, and Sérgio agreed to serve as the Brazilian sponsor for one of my graduate students from the USA, Jessica Lynch, during her study of capuchin monkeys at my field site in 1996–1997. Sérgio’s visits to meet with me and Jessica in the field during that time launched a 4-year collaborative study documenting the timing of births in sympatric howler monkeys and muriquis (Strier et al., 2001), and led to his agreeing to take over from Dr. Gustavo Fonseca as my official Brazilian sponsor on government research permits when Gustavo moved to the USA in 2000. This was also around the time that Sérgio launched a comparative study of muriquis in the region near Santa Maria de Jetibá, in his home state of Espírito Santo.

In 2001, we watched the forest at Fazenda Montes Claros being converted to a private natural heritage reserve, known as the Reserva Particular do Patrimônio Natural Feliciano Miguel Abdala. A few years later, we served together as founding members of the advisory group to the Instituto Chico Mendes de Biodiversidade (ICMBio) for the National Action Plan for the Conservation of Muriquis. Sérgio agreed, and worked with me and by example to encourage former students, post-docs, and colleagues to develop comparative and complementary research programs involving muriquis, and to embrace our mutual commitment to prioritize collaboration instead of competition. I am very proud of the success in these efforts to date, especially because there are now multiple studies of other populations of northern muriquis and sympatric primates being led by former students/now colleagues, who gained their initial training through the opportunities they had gotten on the Muriqui Project of Caratinga. As of this writing, I have worked with about 80 Brazilian students on the Caratinga and other muriqui projects, and many of these former students are now leading projects of their own. Sérgio’s encouragement in these efforts has extended to his help in formalizing my participation as a member of the graduate faculty in his department at the Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo so that I can advise students using data they collected on the field project to pursue their Masters and PhD degrees.

Despite all of this, not all aspects of our collaboration have always been equal. For example, by Brazilian law, as a foreigner I cannot conduct research legally in Brazil without a Brazilian sponsor. Thus, although I have secured nearly all of the funding for the continuity of the Muriqui Project of Caratinga, I could not have sustained the research without Sérgio’s commitment and support. This creates an awkward dependency, of me on Sérgio, but it has also been to my — and the Project’s — great benefit, however, for it has provided a stimulus for Sérgio’s ongoing involvement.

The financial disparities extend back to our days as student field researchers, when I had access to extramural funds for equipment and supplies whereas Sérgio did not. Since then, these disparities in terms of our personal equipment have narrowed, and in some instances, even reversed. Similarly, in the pre-internet days, before widespread access to electronic journals, I had much easier access to the scientific literature. This disparity was further exaggerated by the differences associated with being a native versus non-native English reader.

Nonetheless, there have been many instances in Brazil, particularly in the context of public and governmental meetings, where my not being a native Portuguese speaker impacted my ability to participate and contribute to discussions, much as is the reciprocal case when Sérgio participates in meetings in the USA or in other countries where the currency is English fluency. In Brazil, being a native English speaker is not always advantageous, and I often had to rely on others to be patient with my fluent (but often flawed) spoken Portuguese and even now, to correct my written Portuguese.

As both Sérgio and I have aged and become the principal investigators responsible for others instead of only ourselves, the extent of our interactions has shifted from being primarily restricted to the local residents in the farming community surrounding the Reserve, to our students and colleagues with whom we interact over the research and conservation initiatives. Nonetheless, because we have worked in this area for so long, we have known many of these people for many years. We have all watched one another — and the local community and economy — grow and change over the years. In my case, this led from me being the first North American to live for an extended period of time in the community to being a familiar and long-term presence.

The context of my collaboration with Sérgio is important to emphasize because it was forged in Brazil, a country where there has long been a strong university system with outstanding scientists, primatologists, and conservationists. Sérgio and I have noted differences in our respective training: the US academic system to which I was exposed emphasized critical thinking and the questioning of existing perspectives and models, whereas that to which Sérgio was exposed was much more rigorous about learning detailed systematics, biology, and natural history. Indeed, the importance of field studies to inform the conservation of primates and their habitats was much more at the forefront of primatology decades ago in Brazil and other regions of South America (Strier, 2017) than it was in the USA, where the primary driver in the early 1980s when I first went to Brazil had been to test predictions of socioecological models. Perhaps the most important thing I have learned from my collaboration with Sérgio and other important friends and colleagues in Brazil was the relevance of our discoveries about muriquis to their conservation and management (Strier, 2000).

I think that one of the key features of our collaboration that has transcended differences in our academic training and native languages has been the positionalities we share. These range from our similarly high scientific standards and ethics to our mutual commitments to local capacity-building, to our loyalty to those who have worked decades with us, to our conservation priorities. I also feel that our mutual respect for one another and our complementary skills have contributed to our successful collaboration.

Sergio’s Narrative

During my master's degree in the 1980s I became a primatologist by chance. My advisor called me to work on a project of Dr. Scott Lindbergh, an American who had the objective of reintroducing black howler monkeys raised in France to Brasília National Park. It was a pioneering initiative that really attracted me, so I started to read everything I could about howlers’ ecology and behavior.

While the monkeys that came from France did not arrive, after the 1983 Brazilian Congress of Primatology in Belo Horizonte I met Prof. Célio Vale, who was in charge of the installation of the Caratinga Biological Station, on the Fazenda of Mr. Feliciano Abdala, with support from Dr. Russell Mittermeier. At the time, a North American researcher, Karen Strier, was expected to come to collect data for her doctorate on the ecology and behavior of the muriquis.

When Prof. Célio learned of my interest in howlers, he invited me to study them in Caratinga, where they were very common. Two things attracted me to research in Caratinga: the first was being able to study a primate from the Atlantic Forest, the type of forest for which I had a predilection, and the second is that Caratinga was becoming a “hot spot” for primatology, especially by the rediscovery of the muriquis.

The work in Caratinga was a unique experience for me, first because I got to know some of the most important Brazilian conservationists, such as Adelmar Coimbra Filho, Ibsen Câmara and Célio Vale; and second, for the international relations that began with Russell Mittermeier and foreigners who accompanied him, and finally, for the coexistence with Karen Strier. She was about my age, but had more experience with primates, having already done an internship with baboons in Africa. Furthermore, as a doctoral student at Harvard, mentored by one of the most iconic primatologists of the time, Dr. Irven DeVore, Karen certainly had a superior theoretical background in primatology.

At that time we were living through the last years of the military dictatorship in Brazil, and I was very critical of the supposed collaboration of the US government with the Brazilian dictatorship, attributing it to its imperialist behavior in South America. Certainly, Karen and I, coming from different cultures and countries, thought differently about these matters and this gave us good conversations. I was more politicized and Karen more academic, so we ended up learning a lot from each other.

During the period when Karen was collecting data for her doctorate and I was collecting data for my master's, there were other asymmetries. For example, the house that sheltered us was rebuilt, mainly, to welcome Karen who would come from the USA. I was a secondary occupant. In addition, Karen studied “the biggest primate in the Americas”, critically in danger of extinction, the target of the attention of scientists and people who passed by. In contrast, I studied the brown howler monkey, considered a common animal in the region, which did not arouse great local, national, or international interest.

Added to these asymmetries is the fact that Karen arrived with the project financed, with resources to buy equipment and hire field assistants, while I only had my scholarship. In other words, she had greater institutional support than I did.

Although not very relevant for fieldwork, the language difference also led to some asymmetries. Karen has English as her native language, and I speak Portuguese. Karen studied Portuguese to work in Brazil and was able to communicate reasonably with Brazilians when she arrived, but she certainly couldn't capture certain nuances of the language, local expressions, especially certain jokes, while I was much more comfortable with the local people. In contrast, I didn't speak English and during the visit of some foreigners, I ended up being left out of the conversation, just like Karen was when other Brazilians were there and talking in Portuguese. Over time, this asymmetry was reduced, as Karen started to understand Portuguese very well and I learned English. But I cannot deny that this difference continued to keep us in different positions, as English is an international language and science is communicated in English, so native speakers certainly find it easier to read and understand scientific literature and to communicate on the international stage.

Despite the asymmetries listed above, it is worth noting that Karen has always behaved in a very egalitarian manner towards me, which certainly favored the construction of a scientific partnership and friendship. Over time, that academic asymmetry was reduced, thanks to our exchange of ideas, and Karen's cultural isolation was also reduced, due to her interest in local people and simplicity. I believe that I also helped her to reduce linguistic limitations and contributed for her understanding of Brazil and its people.

Although we have been involved in different research projects for several years, we have maintained a friendship and exchange of ideas ever since. When we returned to an effective scientific collaboration, in the Muriqui's Caratinga project, our relationship became closer. We were both already established researchers, known and respected by our peers, so that we reached the maturity of a collaboration of the same level, respectful and fruitful.

With regard to the Muriqui Project in Caratinga, some asymmetries still exist, mainly because it is Karen's main research project, in which she has been involved for almost 40 years. This certainly explains, in part, why in collaborative articles Karen is usually the first author. Added to this is the fact that Karen is a highly productive scientist, who publishes far more than I do, and she obviously writes in English much more fluently.

In contrast, I'm involved in other research projects and, since 2001, I've been leading a project on muriquis in Espírito Santo, another Brazilian state. Karen is my collaborator on this project and, in a way, the roles here are reversed, as I have a much greater involvement in this project.

Finally, it is worth emphasizing that the egalitarian collaboration that occurs between us is due, mostly, to Karen's attitude towards Brazilians. Unlike some foreign researchers, she did not come to Brazil simply to collect data for her research, but she has effectively participated in the training of dozens of young Brazilian researchers, publishing with them, in addition to contributing to public policies for the conservation of Brazilian primates. Not least, Karen has a very friendly relationship with the local people, making real friendships, including with very simple people.

Discussion

These two sets of narratives share common themes, notably mutual respect and friendship, as well as imbalances in language and funding, but also many differences related to positionalities and cultural context. One common theme that emerged was the crucial role that friendships play in solidifying long-term collaborative relationships. The common ground achieved through friendships facilitates communication (Rodrigues et al., 2021), and mutual trust and respect is an essential part of collaborative success. However, in approaching collaborative relationships across potential power imbalances, foreign and local researchers should remain aware of potential power differentials. In Andean archaeology, Leighton (2020) notes how North American archaeologists’ culture of casual friendliness or “performative informality” obscures power differences and may make foreign archaeologists less aware of the tensions they create for local archaeologists. Such dynamics are likely to be present in primatological fieldwork as well, particularly in contexts where researchers want to facilitate a friendly working environment to appease their discomfort with acknowledging power hierarchies. Primatologists should recognize how performative informality may not translate across cultures and consider how such “friendly” behaviors may be perceived within local cultural contexts. When in positions of power, primatologists must be sensitive to how those in subordinate positions may not feel free to express their discomfort despite such performative informality.

Another common theme is the role in which first/fluent languages create both advantages and disadvantages. English is advantageous for publishing and for accessing international science networks; however, fluency in locally spoken languages is advantageous for full engagement with local communities, and may also be needed for engagement in public and governmental policy meetings. Additionally, a common theme that emerged was differences in the social/cultural capital in accessibility of obtaining funding. Both the prioritization of English as the language of international science, and funding disparities probably contribute to publication biases (Setchell & Gordon, 2018). Thus, increasing access to funding and scientific literature are two dynamics that may help redress power imbalances (Trisos et al., 2021). The problem of publication bias may be more relevant to formally trained range-country scientists, for whom publication is a crucial means of social capital and professional standing, relative to locally employed collaborators such as field assistants who may lack higher education and/or academic training. However, for field assistants, publication may still be a point of pride and an opportunity to see the outcome of fieldwork. Both foreign and range-country collaborators with formal training should provide explicit mentorship for local field assistants in the preparation of publications, explaining the analytical process and results, and in understanding the publication process. Such mentorship is essential to local capacity-building, and should be part of a broader goal of providing pathways to career and educational advancement (Hobaiter et al., 2021; Seidler et al., 2021).

As expected, there were many differences in these narratives that highlight the importance of understanding regional, local, and contextual factors in shaping collaborative relationships. One difference we chose to intentionally highlight was how collaborative dynamics may differ depending on the educational histories of collaborators. Collaborator relationships between PhD-level scientists trained in their respective countries have different power dynamics than such relationships between trained foreign scientists and local project staff with less formal education. On a broader level, there may be different dynamics in countries such as Brazil that require foreign scientists to have in-country collaborators to sponsor them, and countries where there are no such requirements. Another difference that emerged is how disciplinary training may impact both how primatologists approach engagement with colleagues from other cultures and the scientific questions of interest. Primatologists with training in social sciences, including anthropology and sociology, may be more aware of how culture and potential power imbalances shape their collaborative engagement. However, differences in the regional and national disciplinary training of primatologists may lead to different emphases and theoretical approaches to research questions.

In our narratives, Sérgio and Karen are both professional scientists formally trained in their respective countries, one range-country and one foreign, whereas Vicent is an experienced local colleague without a higher education background who works alongside Matt, a trained foreign primatologist who is also Vicent’s employer. Not surprisingly, the collaborative dynamics and some positionality issues are inevitably different. Further considerations of interrogating positionality should also interrogate within-country power dynamics. For example, class or caste differences may shape access to formal education, including English language learning, which in turn may shape interactions between range-country scientists and local project staff.

These examples point to the importance of recognizing the bi-directional transfer of knowledge and mentorship that occurs in foreign/range-country collaborative relationships. The contributions of local project staff in mentoring foreign scientists, and their contributions to project successes, should be formally acknowledged (Bezanson & McNamara, 2019; Haelewaters et al., 2021; Seidler et al., 2021; Trisos et al., 2021). Often, primatology and conservation collaborations prioritize hiring range-country or foreign researchers with university education in supervisory positions, and personnel local to the community as field assistants or guides (Rubis & Theriault, 2020). Such prioritization reflects a de-valuing of experiential and cultural knowledge. Interrogation of positionality may lead to an approach that recognizes both the wealth of knowledge that local and range-country collaborators bring to their work, as well as the educational limitations of foreign scientists.

Several recent papers highlight important steps to decolonial and anti-racist practices in conservation and ecology (Chaudhury & Colla, 2020; Cronin et al., 2021; Haelewaters et al., 2021; Hobaiter et al., 2021; Seidler et al., 2021; Trisos et al., 2021). Such steps include acknowledging the colonial and racist histories of our disciplines, demystifying “hidden curriculums,” or unspoken rules and customs that are often transmitted selectively through mentoring relationships, and fostering equitable collaborative relationships. Equitable collaborative relationships should explicitly value the expertise of local cultural and ecological knowledge, and recognize the expertise of local and range-country collaborators (Haelewaters et al., 2021; Trisos et al., 2021). These efforts require the support of institutions that fund and employ foreign researchers, including governmental funding agencies, conservation organizations, universities, museums, and zoological societies, as institutional structures can often constrain implementation of these goals. However, it’s crucial to listen to, engage with, and adequately credit the range-country researchers leading decolonial work focused on redressing power imbalances (Mabele et al., 2021). We should further be cautious of using the terms “decolonize” and “decolonial” without fully engaging the rich scholarship on this subject (Bhambra, 2014; Mabele et al., 2021; Mignolo, 2007; Quijano, 2000, 2007; Tuck & Yang, 2012).

Finally, it’s important to recognize that decolonial approaches should be localized, rather than attempting broad global generalizations (Sundberg, 2014), and should be guided by range-country and local expertise (see examples from Ashegbofe Ikemeh, 2017; Chua et al., 2020; Hobaiter et al., 2021; Radhakrishna & Jamieson, 2018; Rubis, 2020; Rubis & Theriault, 2020; Seidler et al., 2021). Each region and field site has local cultural dynamics that shape people’s relationships with its ecosystems (Malone et al., 2010; Radhakrishna & Jamieson, 2018). Geographical regions and countries vary in their colonial histories, educational infrastructure, and engagement with foreign scientists, and this shapes the context of potential collaborative work. Thus, our two narrative sets should be considered as guides for how collaborative teams might approach these conversations with regard to positionality. Narratives within a single country or even field site may potentially differ as much as those drawn from different regions across the globe, especially when shaped by different cultural worldviews or positionalities. Nonetheless, we hope that these examples can lead to more reflective approaches in addressing collaborative dynamics in primate field research and conservation.

References

Adams, G., Dobles, I., Gómez, L. H., Kurtiş, T., & Molina, L. E. (2015). Decolonizing psychological science: Introduction to the special thematic section. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 3(1), 213–238. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v3i1.564.

Ahuja, N. (2013). Macaques and biomedicine: Notes on decolonization, polio, and changing representation of Indian rhesus in the United States, 1930–1960. In S. Radhakrishna, M. A. Huffman, & A. Sinha (Eds.), The macaque connection: Cooperation and conflict between humans and macaques (pp. 71–91). Springer Science & Business Media LLC.. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3967-7.

Anderson-Levitt, K. M. (2014). Significance: Recognizing the value of research across national and linguistic boundaries. Asia Pacific Education Review, 15(3), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-014-9322-0.

Antunes, A. P., Massarani, L. M., & de Castro Moreira, I. (2019). Practical botanists and zoologists: Contributions of Amazonian natives to natural history expeditions (1846–1865). Historia Critica, 73, 137–160.

Antunes, A. P., Massarani, L. M., & de Castro Moreira, I. (2018). Local collaborators in Henry Walter Bates’s Amazonian expedition (1848-1859). In F. D’Angelo (Ed.), the scientific dialogue linking America, Asia, and Europe between the 12th and the 20th century. Theories and techniques travelling in space and time (pp. 382–400). Associazione culturale Viaggiatori: Nápoles.

Ashegbofe Ikemeh, R. (2017). Home advantage: How Africans are taking on the reins of leadership in primatology on the continent. In biodiversity (Vol. 18, issue 4, pp. 210–211). Taylor and Francis ltd. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2017.1407672.

Asquith, P. J. (2000). Negotiating science: Internationalization and Japanese primatology. In S. C. Strum & L. M. Fedigan (Eds.), Primate encounters: Models of gender, science, and society (pp. 165–183). University of Chicago Press.

Baker, K., Eichhorn, M. P., & Griffiths, M. (2019). Decolonizing field ecology. Biotropica, 51(3), 288–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/btp.12663.

Barber, P. H., Ablan-Lagman, M. C. A., Ambariyanto, A., Berlinck, R. G. S., Cahyani, D., Crandall, E. D., Ravago-Gotanco, R., Juinio-Meñez, M. A., Mahardika, I. G. N., Shanker, K., Starger, C. J., Toha, A. H. A., Anggoro, A. W., & Willette, D. A. (2014). Advancing biodiversity research in developing countries: The need for changing paradigms. Bulletin of Marine Science, 90(1), 187–210. https://doi.org/10.5343/bms.2012.1108.

Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475.

Bezanson, M., & McNamara, A. (2019). The what and where of primate field research may be failing primate conservation. Evolutionary anthropology: Issues, news, and reviews, November 2018, Evan.21790. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.21790.

Bicca-Marques, J. C. (2003). How do howler monkeys cope with habitat fragmentation? In L. K. Marsh (Ed.), Primates in fragments (pp. 282–303). Springer.

Bicca-Marques, J. C. (2016). Development of primatology in habitat countries: A view from Brazil. American Anthropology, 118, 140–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.12503.This.

Bhambra, G. K. (2014). Postcolonial and decolonial dialogues. Postcolonial Studies, 17(2), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2014.966414.

Brooks, J. S., Waylen, K. A., & Mulder, M. B. (2012). How national context, project design, and local community characteristics influence success in community-based conservation projects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(52), 21265–21270. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1207141110.

Caretta, M. A. (2015). Situated knowledge in cross-cultural, cross-language research: A collaborative reflexive analysis of researcher, assistant and participant subjectivities. Qualitative Research, 15(4), 489–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794114543404.

Chaudhury, A., & Colla, S. (2020). Next steps in dismantling discrimination: Lessons from ecology and conservation science. Conservation Letters, 14(2), e12774. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12774.

Chua, L., Harrison, M. E., Fair, H., Milne, S., Palmer, A., Rubis, J., Thung, P., Wich, S., Büscher, B., Cheyne, S. M., Puri, R. K., Schreer, V., Stępień, A., & Meijaard, E. (2020). Conservation and the social sciences: Beyond critique and co-optation. A case study from orangutan conservation. People and Nature, 2(1), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10072.

Cronin, M. R., Alonzo, S. H., Adamczak, S. K., Baker, D. N., Beltran, R. S., Borker, A. L., Favilla, A. B., Gatins, R., Goetz, L. C., Hack, N., Harenčár, J. G., Howard, E. A., Kustra, M. C., Maguiña, R., Martinez-Estevez, L., Mehta, R. S., Parker, I. M., Reid, K., Roberts, M. B., & Zavaleta, E. S. (2021). Anti-racist interventions to transform ecology, evolution and conservation biology departments. Nature Ecology and Evolution, 5(9), 1213–1223. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-021-01522-z.

de Vos, A. (2020). The Problem of “Colonial Science.” Scientific American, , 1–10.

De Waal, F. B. M. (2003). Silent invasion: Imanishi’s primatology and cultural bias in science. Animal Cognition, 6(4), 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-003-0197-4.

Deliovsky, K. (2017). Whiteness in the qualitative research setting: Critical skepticism, radical reflexivity and anti-racist feminism. Journal of Critical Race Inquiry, 4(1), 1–24.

Dunsworth, H. (2021). This view of wife. In J. DaSilva (Ed.), A Most interesting problem: What Darwin’s descent of man got right and wrong about human evolution (pp. 144–161). Princeton University Press.

Estrada, A., Garber, P. A., Pavelka, M. S. M., & Luecke, L. (2006). Overview of the Mesoamerican primate fauna, primate studies, and conservation concerns. In A. Estrada, P. A. Garber, M. S. M. Pavelka, & L. Luecke (Eds.), New perspectives in the study of Mesoamerican primates: Distribution, ecology, behavior, and conservation (pp. 1–22). Springer Science & Business Media LLC.

Fagan, M. B. (2007). Wallace, Darwin, and the practice of natural history. Journal of the History of Biology, 40(4), 601–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-007-9126-8.

Fan, P. F., & Ma, C. (2018). Extant primates and development of primatology in China: Publications, student training, and funding. Zoological Research, 39(4), 249–254. https://doi.org/10.24272/j.issn.2095-8137.2018.033

Fedigan, L. M., & Strum, S. C. (1999). A brief history of primate studies: National traditions, disciplinary origins, and stages in north American field research. In P. Dolhinhow & A. Fuentes (Eds.), The nonhuman primates (pp. 258–269). Mayfield Publishing Company.

Fuentes, A. (2011). Being human and doing primatology: National, socioeconomic, and ethnic influences on primatological practice. American Journal of Primatology, 73(3), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20849.

Fuentes, A. (2021a). “On the races of man”: Race, racism, science, and hope. In J. DaSilva (Ed.), A most interesting problem: what Darwin’s descent of man got right and wrong about human evolution (pp. 144-161). Princeton University Press

Fuentes, A. (2021b). “The Descent of Man,” 150 years on. Science, 372(6544), 769–769. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abj4606

Garland, E. (2008). The elephant in the room: Confronting the colonial character of wildlife conservation in Africa. African Studies Review, 51(3), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.1353/arw.0.0095.

Gokken, B. (2018). Recovering conservationist: Q & A with orangutan ecologist June Mary Rubis. Mongabay. http://news.mongabay.com/2018/08/recovering-conservationist-qa-with-orangutan-ecologist-june-mary-rubis/

Haelewaters, D., Hofmann, T. A., & Romero-Olivares, A. L. (2021). Ten simple rules for global north researchers to stop perpetuating helicopter research in the global south. PLoS Computational Biology, 17(8), e1009277. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009277.

Haraway, D. J. (1989). Primate visions: Gender, race, and nature in the world of modern science. Routledge, Chapman & Hall, Inc.

Hart, A. G., Leather, S. R., & Sharma, M. V. (2020). Overseas conservation education and research: The new colonialism? Journal of Biological Education, 55(5), 569–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/00219266.2020.1739117

Hill, C. M., & McLennan, M. R. (2016). The primatologist as social actor. Etnografica, 20(3), 668–671. https://doi.org/10.4000/etnografica.4771Etnográfica

Hoàng, T. M. (2016). Development of primatology and primate conservation in Vietnam: Challenges and prospects. American Anthropologist, 118, 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.12515.This.

Hobaiter, C., Akankwasa, J. W., Muhumuza, G., Uwimbabazi, M., & Koné, I. (2021). The importance of local specialists in science: Where are the local researchers in primatology? Current Biology, 31(20), R1367–R1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.09.034

Horwich, R. H., & Lyon, J. (2007). Community conservation: Practitioners’ answer to critics. Oryx, 41(3), 376–385. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605307001010.

Jacobson, D., & Mustafa, N. (2019). Social identity map: A reflexivity tool for practicing explicit positionality in critical qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919870075.

Jost Robinson, C. A., & Remis, M. J. (2018). Engaging holism: Exploring multispecies approaches in ethnoprimatology. International Journal of Primatology, 39(5), 776–796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10764-018-0036-8.

Kamenya, S. (2002). Human baby killed by Gombe chimpanzee. Pan Africa News, 9(2), 26–26. https://doi.org/10.5134/143412.

Leighton, M. (2020). Myths of meritocracy, friendship, and fun work: Class and gender in north American academic communities. American Anthropologist, 122(3), 444–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/aman.13455.

Mabele, M. B., Sandroni, L. T., Collis, Y. A., & Rubis, J. (2021). What do we mean by decolonizing conservation? A response to Lanjouw (2021). Conviva. https://conviva-research.com/what-do-we-mean-by-decolonizing-conservation-a-response-to-lanjouw-2021/.

Malone, N. M., Fuentes, A., & White, F. J. (2010). Ethics commentary: Subjects of knowledge and control in field primatology. American Journal of Primatology, 72(9), 779–784. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20840.

Matsuzawa, T., & McGrew, W. C. (2008). Kinji Imanishi and 60 years of Japanese primatology. Current Biology, 18(14), R587–R4591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.040.

McLennan, M. R., & Hill, C. M. (2013). Ethical issues in the study and conservation of an African great ape in an unprotected, human-dominated landscape in western Uganda. In J. MacClancy & A. Fuentes (Eds.), Ethics in the field: Contemporary challenges (pp. 42–66). Berghahn.

McLennan, M. R., & Hill, C. M. (2010). Chimpanzee responses to researchers in a disturbed forest–farm mosaic at Bulindi, western Uganda. American Journal of Primatology, 72(10), 907–918. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.20839

McLennan, M. R., & Hill, C. M. (2012). Troublesome neighbours: Changing attitudes towards chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in a human-dominated landscape in Uganda. Journal for Nature Conservation, 20(4), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2012.03.002

McLennan, M. R., Hintz, B., Kiiza, V., Rohen, J., Lorenti, G. A., & Hockings, K. J. (2021). Surviving at the extreme: Chimpanzee ranging is not restricted in a deforested human-dominated landscape in Uganda. African Journal of Ecology, 59(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/aje.12803.

McLennan, M. R., & Hockings, K. J. (2016). The aggressive apes? Causes and contexts of great ape attacks on local persons. In F. M. Angelici (Ed.), Problematic wildlife: A cross-disciplinary approach (pp. 373–394). Springer.

McLennan, M. R., Lorenti, G. A., Sabiiti, T., & Bardi, M. (2020). Forest fragments become farmland: Dietary response of wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) to fast-changing anthropogenic landscapes. American Journal of Primatology, 82(4), e23090. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23090

Mecca, B. (2020). When your country is a case study: Being an Indonesian environmentalist at Yale. Correspondents of the World, (August 24).

Mendes, S. L., da Silva, M. P., & Strier, K. B. (2010). O Muriqui. IPEMA—Instituto de Pesquisas da Mata Atlantica, Publicação do Programa Difusão da Biodiversidade, Vitória, Espirito Santo, Brasil.

Mendes, S. L., Silva, M. P., Oliveira, M. Z. T., & Strier, K. B. (2014). O Muriqui: Símbolo da Mata Atlântica, 2o edição. IPEMA—Instituto de Pesquisas da Mata Atlantica, Publicação do Programa Difusão da Biodiversidade, Projeto Muriqui, Espirito Santo, Brasil.

Mignolo, W. D. (2007). Introduction: Coloniality of power and de-colonial thinking. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162498.

Mittermeier, R., Fonseca, G., Rylands, A., & Brandon, K. (2005). A brief history of biodiversity conservation in Brazil. Conservation Biology, 19(3), 601–607.

Montgomery, G. M. (2005). Place, practice and primatology: Clarence Ray Carpenter, primate communication and the development of field methodology, 1931–1945. Journal of the History of Biology, 38(3), 495-533. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-005-0553-0

Moon, D. (1999). White enculturation and bourgeois ideology. In T. K. Nakayama & J. N. Martin (Eds.), Whiteness: The communication of social identity (pp. 177–197). SAGE Publications.

Moon, K., Adams, V. M., & Cooke, B. (2019). Shared personal reflections on the need to broaden the scope of conservation social science. People and Nature, 1(4), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10043.

Moreira, I. C. (2002). O escravo do naturalista — O papel do conhecimento nativo nas viagens científicas do século. Ciência Hoje, 31(184), 40–48.

Nkomo, M. N. (2020). The Achilles heel of conservation. iLizwe, 1–11.

Pasquini, M. W., & Olaniyan, O. (2004). The researcher and the field assistant: Across-disciplinary, cross-cultural viewing of positionality. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 29(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1179/030801804225012446.

Pickren, W. E. (2009). Liberating history: The context of the challenge of psychologists of color to American psychology. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15(4), 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017561.

Quijano, A. (2000). Coloniality of power and eurocentrism in Latin America. International Sociology, 15(2), 215–232.

Quijano, A. (2007). Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353.

Radhakrishna, S., & Jamieson, D. (2018). Liberating primatology. Journal of Biosciences, 43(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12038-017-9724-3.

Rodrigues, M. A. (2019). It’s time to stop lionizing Dian Fossey as a conservation hero. LadyScience. https://www.ladyscience.com/ideas/time-to-stop-lionizing-dian-fossey-conservation.

Rodrigues, M. A. (2020). Neocolonial narratives of primate conservation. IUCN Primate Specialist Group for Primate Interactions Webblog. https://human-primate-interactions.org/blog/.

Rodrigues, M. A., Yoon, S. O., Clancy, K. B. H., & Stine-Morrow, E. A. L. (2021). What are friends for? The impact of friendship on communicative efficiency and cortisol response during collaborative problem solving among younger and older women. Journal of Women & Aging, 33(4), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2021.1915686

Rubis, J. M. (2020). The orang utan is not an indigenous name: Knowing and naming the maias as a decolonizing epistemology. Cultural Studies, 34(5), 811–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2020.1780281.

Rubis, J. M., & Theriault, N. (2020). Concealing protocols: Conservation, indigenous survivance, and the dilemmas of visibility. Social and Cultural Geography, 21(7), 962–984. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2019.1574882.

Sachs, A. (2003). The ultimate “other”: Post-colonialism and Alexander Von Humboldt’s ecological relationship with nature. History and Theory, 42(42), 111–135.

Sandelowski, M. (1991). Telling stories: Narrative approaches in qualitative research. The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 23(3), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1991.tb00662.x.

Seidler, R., Primack, R. B., Goswami, V. R., Khaling, S., Devy, M. S., Corlett, R. T., Knott, C. D., Kane, E. E., Susanto, T. W., Otali, E., Roth, R. J., Phillips, O. L., Baker, T. R., Ewango, C., Coronado, E. H., Levesley, A., Lewis, S. L., Marimon, B. S., Qie, L., & Wrangham, R. (2021). Confronting ethical challenges in long-term research programs in the tropics. Biological Conservation, 255, 108933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108933.