Abstract

New first-year students are vulnerable to dropping out of university because the transition into higher education (HE) is difficult to navigate. Using thematic analysis, we analysed focus groups/interview, exit interviews and qualitative survey data with university students during their first year as criminology undergraduates to explore how they transitioned into HE. Findings show that the transition to a new identity of ‘university student’ was hampered by feelings of awkwardness, which prevented students from fully integrating into student life. However, the subject of criminology was a protective factor because interest in the topic and wanting a degree for betterment, including for future career plans, buffered students against dropping out. We argue that subject-specific interventions may be better in supporting the retention of students and that addressing physical, social and academic awkwardness is key.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The retention of university students is a serious issue for institutions and has received much attention of late amidst concern that increased levels of attrition are costly on global, societal, institutional and individual dimensions (Aljohani, 2016). Poor engagement or low numbers of students who complete their degree programme can lead to poor feedback from students and reputational damage for the institution (Merrill, 2014). This is particularly pertinent in the contemporary market in which students are constructed as customers and institutions compete for them (Maisuria & Cole, 2017). Crucially, new first year students are most at risk of dropping out (Wray et al., 2014), and institutions are increasingly aware that the transition to higher education is an important predictor of continued engagement (Ang et al., 2019). The expectations, perceptions and experience of students in their first year of higher education are thought to be indicative of attrition outcomes, course satisfaction and engagement with learning (Ang et al., 2019; Tinto, 1993). Understanding the student’s background and current circumstances are crucial in shaping the ways a student experiences higher education and their academic outcomes (Mier, 2018); thus, attention has shifted to identifying students who may be at risk of dropping out in order to provide additional support. This is particularly important in universities which have a widening participation agenda, that is, those institutions which specifically aim to increase access to HE for under-represented groups as a way to combat poverty or social exclusion (Christie et al., 2005). This paper explores how new first-year criminology students transition into HE in a post-1992 ‘widening participation’ university in the UK. We begin by reviewing the relevant literature on student retention and student identity.

Understanding why students drop out of HE

Understanding the causes of student attrition is key in order for institutions to implement interventions which either support students to integrate or adapt the university environment to the needs and preferences of the student (Zepke & Leach, 2005). Yet, dropping out of university is rarely attributable to one factor. More frequently it is a complex knot of multiple, interlinked factors that work to ‘push’ students out of higher education (Merrill, 2014; Wray et al., 2014; Wilcox et al., 2005). This is often less visible in quantitative research, particularly if students are asked to choose one reason for withdrawal on a survey (McQueen, 2009). In particular, the catch all term ‘personal circumstances’ offers little qualitative understanding of the reasons for withdrawal and ‘obscures the role institutional factors play in the student’s decision to leave’ (Russell & Jarvis, 2019, p.497). Common factors which have been found to contribute to attrition include financial hardship or a fear of getting into debt, paid employment commitments (Ang et al., 2019), family, relationship or caring responsibilities (Christie et al., 2005), poor health or crucial life events such as a bereavement or pregnancy (Tinto, 1975; McQueen, 2009; Bennett & Kane 2010; Maher & McAllister, 2013; Wray et al., 2014). While financial or wellbeing support may mitigate these difficulties, such circumstances can rarely be entirely prevented or controlled by the institution. Other factors include disappointing academic performance (Chamberlain, 2012), dislike of the chosen subject or poor preparation for university study which are potentially more amenable to institutional intervention. For example, Pennington et al. (2018) found that pre-entry programmes could support transitions to HE and positively impact students’ academic self-confidence (see also Ang et al., 2019; MacFarlane, 2018; Gazeley & Aynsley, 2012). Ensuring that students have good quality information and advice about the course and the institution and strong induction programmes, which introduce students to additional support services, has been found to have positive effects on student retention and satisfaction (Zepke & Leach, 2005).

Many students will encounter at least one factor associated with attrition during their studies, and while some students do drop out, most persevere despite difficult personal circumstances. Aljohani argues that theoretical models of retention are less about specific reasons why students leave early and more about understanding ‘why some students react to these specific factors by withdrawing’ (2016, p.44, emphasis added). Retention strategies aim to understand why students drop out and how to prevent this; more recently the focus has turned to how some students develop resilience and the ability to succeed despite hardship (Cotton et al., 2017; du Plessis & Benecke, 2011). Factors associated with the development of resilience have been identified, such as the creation of support networks (Holdsworth et al., 2017; Wray et al., 2014), strong personal tutoring support (du Plessis & Benecke, 2011) or, simply, high motivation (Cotton et al., 2017), which can enable students to continue to engage in their studies. There is evidence that the development of a strong professional identity can help students overcome adversity. Wray et al., (2014, p.1712) argue that reinforcing the ‘uniqueness and value of nursing’ can help student nurses develop resilience. Similarly, Wong and Kaur (2018) found that the development of a vocational identity positively impacted on students’ engagement and motivation. Yet, in framing retention as dependent on a personal characteristic such as resilience, care should be taken to avoid constructing those students who do drop out as ‘deficient’. While institutional strategies can support the development of resilience, some students are inherently more ‘at risk’.

In order to successfully transition to university, students need to develop a sense of belonging and an identity as ‘student’ (MacFarlane, 2018); however, particular students may find this more difficult to achieve than others. Some research has focused on students from groups which are traditionally under-represented in HE or those who may face structural barriers to participation (Cotton et al., 2017). These may include students from low income or minority racial/ethnic backgrounds, students with disabilities or those who are the first in their family to attend university (Cotton et al., 2017; Wong, 2018). Students from these groups are likely to have less access to familial support, less understanding of the realities of studying at university, less confidence and more likely to feel out of place (Clayton et al., 2009; du Plessis & Benecke, 2011; Wong, 2018), making them at increased risk of dropping out. Yet, Cotton et al. (2017) note that students can have markedly different experiences at university despite coming from comparable backgrounds, so a deeper understanding of the nuances of student identity is necessary. Thus, institutions which aim to increase participation among ‘non-traditional’ students must take both risk and resilience into account when devising strategies to support retention. The next section explores this further by understanding the construction of a student identity.

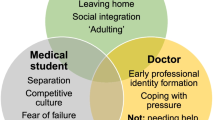

Constructing the student identity

A well-developed student identity is associated with positive effects on retention, engagement, progression and attainment (MacFarlane, 2018). The concept of habitus is useful to frame the experiences of new students at university. Bourdieu understands habitus as a set of ‘internalised structures, schemes of perception, conception and action common to all members of the same group or class’ (1977, p.86 cited in Wong, 2018, p.2). Habitus plays a crucial role in the way the social world is understood, the response to social situations and the available choices for an individual; thus, individual actions more frequently uphold social structures and reproduce power dynamics (Reay et al., 2001). Habitus may, therefore, be conceptualised as an ‘internalised limit’ (Bourdieu, 2010, p.482), which maintains the status quo. For Renninger (2009), identity develops through interactions so social experiences of university support the student to develop a stable student identity (Scanlon et al., 2007). New students may be described as having some ‘knowledge about’ university but little situated ‘knowledge of’ which can be unsettling for identities (Scanlon et al., 2007). Yet the ability to develop a student identity is influenced by social class. The field of university advantages those students from typical middle-class backgrounds (Christie et al., 2005; MacFarlane, 2018; Wong, 2018), despite widening participation efforts; therefore, working-class university students are culturally disempowered. Thus, students from widening participation backgrounds may find that their established habitus conflicts with the new field of HE (MacFarlane, 2018), which may value particular resources or capital and have its own set of social norms which they have little ‘knowledge of’ (Scanlon et al., 2007). In such cases, successful transition is dependent on ‘breaking through’ (Bourdieu, 2010), which may induce discomfort or awkwardness as individuals try to find their place in an unfamiliar field. Kotsko (2010) conceptualises awkwardness as an inherently collaborative state, that is, it is formed in social situations and experienced communally. This may come from an absence of social norms which govern behaviour or from the misinterpretation of such norms leading to a perceived transgression in a given social situation. Being unaware of the social norms in the new field or fear of making a mistake creates an environment in which awkwardness can flourish (Kotsko, 2010). Yet, as Scanlon et al. (2007) argue, students need interactions with others in order to create the context for new identity development, so breaking through the awkwardness is crucial.

There is tension between two competing discourses of retention and thus a lack of consensus on how a student identity is constructed. Tinto’s influential Student Integration Model (1975) focused on a student’s ability to assimilate into university culture. Students need to detach from one’s established social norms and communities and take up the values associated with the new HE environment. Russell and Jarvis (2019) argue that fostering such a ‘sense of belonging’ is key to institutional approaches to retention. While this seems logical, Christie et al. argue that the integration approach risks conceptualising some students, particularly those from widening participation backgrounds, as ‘problematic’, and that they must change themselves in order to fit in at university (2005, p.5). In other words, non-traditional students might be understood as inherently awkward, as they go through a process of adaptation to a new field. While the need to separate from pre-university connections in order to achieve integration has been documented in the literature, the relationship between old and new is more complex. Strong support networks, which are positively associated with engagement in studies, can be provided by family members or old friends as well as peer learners (Holdsworth et al., 2017), particularly for ‘non-traditional’ students (Guiffrida, 2004; Wong, 2018).

In light of these findings, some focus has shifted from student assimilation to institutional accessibility (Tight, 2020; Zepke & Leach, 2005).

Central to the emerging discourse is the idea that students should maintain their identity in their culture of origin, retain their social networks outside the institution, have their cultural capital valued by the institution and experience learning that fits with their preferences. (Zepke & Leach, 2005, p.54)

This may have positive implications for efforts to decolonise the curriculum, diversify cohorts, widen participation and resist efforts to culturally homogenise graduates. However, it could also be argued that the transformative potential of education is lost. This is important to consider when carrying out research on a particular type of university student. For example, while research has focused on the retention of students on particular courses such as nursing (Wray et al., 2014), or the retention of students from particular demographics (Wong, 2018), this paper examines specifically the retention of students on a criminology programme. This is relatively under-researched in the UK context, despite it being a popular choice of course—currently there are 800 programmes in the UK which involve criminology (Levi 2017 cited in Trebilcock & Griffiths, 2021, p.1). Students studying criminology report being motivated to do so by a strong interest in the subject, a desire to help people, to support future career plans or because they have experienced crime (Trebilcock & Griffiths, 2021). For these reasons, it is expected that HE has a long-term transformative effect if students are retained on their programme. To this end, the next section outlines our methods to explore how students, who are studying criminology, transition into HE.

Methods

Procedure

This study pertains to a ‘post 1992’ institution—that is, a former polytechnic which was granted university status in 1992 and which are often associated with widening participation. Without identifying the university from where the data was gathered and noting that HESA (Higher Education Statistics Agency) measure non-continuation rates of students differently from how the university measures them, the university compares poorly against other benchmarked universities in retaining students over the academic years 2014/2015, 2015/2016 and 2016/2017 in the HESA (2021) statistics. At an institutional level, from 2007 to 2014, the criminology programme at the HEI had consistently failed each year to meet the then faculty’s target of retaining 89% of its student enrolment. Such an unadmirable accolade led to the Criminology Retention Project: a quantitative and qualitative analysis of factors identifying and explaining student attrition using data gathered from three consecutive first year cohorts on an undergraduate criminology programme at a university in the North of England, from 2014 to 2017. The study progressed through the ethics procedure at the university and was approved. Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from participants. The focus of this paper is the qualitative analysis of the data. This data came from the following:

-

Six focus groups/interview recorded with 17 students during their first year of study to explore how students, who are studying criminology, transition into HE. Of these students, 5 were male, 12 were female, 14 defined themselves as working classFootnote 1 all 17 identified as White British, 6 were mature studentsFootnote 2 and 5 had moved to study at the university.

-

Notes from exit interviews, mostly during their first year of study, to explore factors related to dropping out, with 13 other students. Of these students, 1 was male, 12 were female, 11 defined themselves as working class, 11 identified as White British and 2 as White Other; none of these students were mature, and 8 had moved to study at the university.

-

From open questions on periodic surveys completed by the wider cohort of students during their first year, n = 165, which also includes those students in focus groups and interviews. Of these students, 123 (75%) were female, 41 (25%) were male, 124 defined themselves as working class, 138 identified as White British, 13 as White Other, 9 as Black/Asian/Other British, 3 as Black/Asian/Other, 42 (26%) were mature students and 52 had moved to study at the university.Footnote 3 Of the comparable statistics that the university gather on its first-year September entrants, for the years 2014/2015, 2015/2016 and 2016/2017, 60% were female, 40% were male and 26% were mature students. Thus, there were a higher rate of females overall in this study compared to the wider university cohort.

The surveys were completed by the students at the start of the programme (survey 1), mid-way through semester 1 (survey 2), start of semester 2 (survey 3) and towards the end of semester 2, i.e. almost at the end of their first year of study (survey 4). At the start of the programme, students were asked why they had chosen to study the subject of criminology and what they hoped to do after graduation. Throughout the first year, on surveys 2, 3 and 4, students were asked if they had thought about dropping out of the university and why and what prevented them from dropping out. In survey 4, students were asked again what they hoped to do after graduation.

Data analysis

It is important to define what we mean by student retention and student drop-out due to the implications of tailoring institutional support measures (see Tinto, 1975). We use a narrow definition of student drop-out because it counts those who have gained a Certificate of HE award at the end of their first year and those who have transferred internally in the drop-out rate. Thus, the definition of student drop-out is a student who does not ‘pass and proceed’ onto their second year of the undergraduate criminology programme at the HEI. Consequently, comparing HEI’s rates of student drop-out with our research is problematic because institutions often do not include internal transfers because the student is still retained in the institution, albeit they are on a different programme. Similarly, comparing our data with HESA, non-continuation data is also problematic because of the different measures used to compile the statistics. With this in mind, twenty-five per cent (n = 42) of the wider cohort of students (n = 165) did not progress beyond their first year on the programme. Thirty-eight per cent (n = 63) of this wider cohort did not graduate from the programme. Of the 17 students who took part in the focus groups, 5 of these were students who did not graduate from the programme: neither did the 13 students in exit interviews (clearly). Understanding how these criminology students transition into HE is important, if education is to have a transformative effect, therefore, we were interested in exploring the ways in which students represented their experiences of HE and their understandings of the transitional period.

Transcripts were subject to close, interpretive reading to identify recurring themes. In understanding epistemology as socially constructed, we used the data to identify the shared opinions and experiences of students which form an underlying discourse of HE transition—to dig deeper into how student identity is constructed by students. The analysis presented here constitutes a nuanced account of one unanticipated theme which occurred frequently—that of awkwardness. While coding identified participants feeling self-consciousness, anxious, embarrassed, weird or uncomfortable, these were grouped under the broader heading of awkwardness as this term was used most frequently, including seventeen times in one focus group. Further analysis into the manifestations of awkwardness allowed us to identify three distinct dimensions, which the following section presents.

Findings

The participants in this study often referenced or alluded to awkwardness in relation to their experiences as new students. This suggests a shared understanding of this transitional period as one which is inherently discomforting or unsettling. We identified three different types of awkwardness which were reported by multiple participants—physical or geographical, academic and social—thus the quotes presented are representative of a significant number of participants’ views. The quotes presented are from students who identified as predominantly working class and White British. One student identified as White Other, and one student identified as middle class, as indicated. Some quotes are from mature students, also indicated. While all three types of awkwardness are presented and evidenced here as distinct entities for clarity, in reality, this is an interlinked system of discomfort in which different kinds of awkwardness affect each other and create a cumulative and tangled net.

Physical or geographical awkwardness

It is perhaps unsurprising that students transitioning into HE felt uncomfortable in these new spaces. The majority of respondents identified themselves as working class and, thus, would be classed as non-traditional. Previous research has found that such students can feel anxious as they move into unfamiliar places and are sometimes unaware of the rules and expectations associated with the environment (Clayton et al., 2009). In this study, this often manifested itself in students feeling out of place in the physical surroundings—not knowing one’s way around or being unable to find what they needed—all commonly discussed.

…I was just thinking well how will I know who anyone is, how do I know if I’m in the right place and that…. (female, working class [w/c], 2014/15, Focus Group [FG] 3)

Students frequently reported having little connection to the university or the city, even when they had moved to study at the university. Feelings of homesickness or missing friends and family were cited by the majority of students who had moved to attend university, and many students returned to their family home often which furthered their lack of connection to the university location.

…You miss home a lot. I thought I wouldn’t miss home as much as I do and that’s why I go back all the time…. (male, w/c, mature, 2014/15, FG 3)

…I’m living at home extra instead of staying in [university city], yeah. …I prefer it like I was homesick and stuff…. (female,Footnote 4 2014/15, FG2)

This was noticed by other students.

What they tend to do on a Thursday is they go home for the full weekend, they don’t stay in [City], a lot of them go home to their parent’s houses. (female, w/c, mature, 2015/2016, FG 4)

Homesickness or wanting to be closer to family was cited by the majority of withdrawing students in exit interviews as part of their reason for dropping out but rarely the sole factor. This echoes previous research by Guiffrida in which Black students attending predominantly White institutions described ‘the fear of losing their connection to their friends from home as a reason for their attrition’ (2004, p. 697). A number of the students in our study described their dislike of university accommodation, but it is difficult to ascertain whether this was a reason for, or a consequence of, homesickness. Frequent visits home worked to facilitate a gradual withdrawal from university for some students. Missing home was also cited in survey data as a reason why some students had thought about dropping out of university, for example ‘live too far away from home’ (female, w/c, survey 2, mid-semester 1).

One student maintained employment in her hometown—this made more sense to her than transferring to a branch of the same company in the university city as she could continue to work during the holidays when she would be living at home.

…I applied and got rejected [for a transfer]… cause I won’t work holidays because I’ll be going back home. (female, w/c, 2015/2016, FG/I [interview] 5)

For other students, there was little motivation to make friends at university as they took every opportunity to return home to more established friendship groups. While this seemed logical to the student, who reported feeling isolated and lonely, it meant that their opportunity to create support networks and social groups at university in order to feel more included was limited further (see, for example Christie et al., 2005).

…because I go home every weekend, so I’m off on Friday, Saturday and Sundays, I go back to [Hometown], so I tend to not mix around a lot with people from here, …which is probably bad, but like I just tend to stick with people I know back in [Hometown] (male, w/c, mature, 2014/15, FG 3)

Awkwardness in the university space could impact attendance and academic achievement. The following quote is from a focus group which took place in November.

I haven’t been to the library once like, believe it or not….It’s weird, I just don’t want to go because I just think I’ll look out of place because I’d just not know what I’m looking for and I’d just look like a lost sheep. (male, w/c, 2014/15, FG 1)

Thus, the physical or geographical discomfort impacted both academic and social integration.

However, one student, who moved to study at the university, described how they were guided through Fresher’s week by activities organised by the institution and supported by the use of social media.

…The first couple of nights before moving away I was just thinking… how am I going to find everything, how am I going to meet people who I know nothing about, how am I going to settle into this course, and it just came completely naturally as we were just told right ok we’ll all meet at the thing, we can get this bus in, just come for this time, we’ll all sit together and we’ll make it quite casual and then we were all going from one event to the next….We were taken from one to the next all as a group, it wasn’t a case of finding your own way there and it was really good…I didn’t feel at any point like I was going to get lost or… that I wouldn’t have anyone with me, sort of thing. (female, w/c, 2014/15, FG 3)

Despite being worried about the transition to university, she describes the feeling of community during induction and how this ameliorated some of the awkwardness, ‘it just came completely naturally’. Being part of a course Facebook group from the first day helped this student to make friends and provided a support network, even when she did not know the other students. Despite this positive experience the student had had during induction, she did not graduate from the criminology programme. Thus, we need to also consider the interplay of academic awkwardness when exploring how students, who are studying criminology, transition into HE.

Academic awkwardness

Many students described being worried about their academic performance, comparing themselves to others or struggling to participate in class activities due to feelings of discomfort. Sometimes this was due to returning to education after a break or a lack of confidence in one’s own academic abilities, as the following quotes illustrate.

It’s all new to me…I find it harder than what I thought it was going to be….other people in the class have got a better knowledge already than what I’ve got so I feel as if I’m already behind them.... (male, w/c, 2014/15, FG 1)

…Well I was a bit apprehensive being a mature student… I think initially I thought I wouldn’t settle in here…studying at this level, I had worries about that…. (female, middle class [m/c], mature, 2016/17, FG 6)

Even students who ordinarily were confident and outgoing found the transitional period of student life difficult. Not knowing other students meant that participants avoided making connections, introducing themselves or participating in group discussions.

…even I’m like really confident and I don’t like talking to people I don’t know. (female, w/c, 2014/15, FG 1)

This can affect academic performance because social isolation in the classroom can hamper students in meeting the module/course learning outcomes, particularly if it entails group work as the next section of the findings illustrates. Students who unfavourably compared themselves to others did not have the chance to understand that actually everyone was in the same boat because they felt awkward striking up a conversation or speaking out, meaning that these feelings continued unchallenged.

Not enjoying the course was often cited as a reason for withdrawal in exit interviews with students, but, again, rarely as the sole factor. To some extent, it was also cited in survey data, when students were asked why they had thought about dropping out of university—for example ‘just not enjoying uni life. The course is different to what I expected’ (female, w/c, survey 3, start of semester 2). It is, therefore, difficult to tease out whether the programme itself was the problem or if dislike of the course was a result of isolation or homesickness. When participants did not make friends, they were less likely to attend classes, less likely to ask for help and less likely to engage in learning activities, all of which had a potentially negative impact on their academic performance and their perceptions of the course. In one case, a student’s academic discomfort manifested in feelings of not being clever enough and that he could not grasp what was being taught which caused him some distress because he was highly motivated to study. In the exit interview, he reflected that he needed more contact time with tutors and smaller classes, and he subsequently received this by undertaking levels 4 and 5 as part of a HND at a local college. He returned to study level 6 at the university and graduated, saying it was the right thing for him to do. This academic awkwardness is inextricably linked to social awkwardness as the next section shows.

Social awkwardness

The majority of participants described some awkwardness when making friends and talking to new people for the first time, yet they also understood the value and importance of friends.

I think it’s really important because it motivates you, like if you had no friends and you were struggling it would be easier to just drop out but if you had friends doing what you were doing….keep you from wanting to leave. (male, w/c, 2014/15, FG 1)

… I love coming to university and I think it’s basically because of the friends that I’ve met, erm, it’s hard work yes but I think you all get through it together. …. (male, w/c, mature, 2016/17, FG 6)

Other participants described how not knowing others in a seminar group impacted participation in class.

…for my social theory seminar I’m by myself so normally I’m quite vocal but because I don’t really know many people yet, I’m quite quiet but I listen to everything. (female, w/c, 2015/2016, FG/I 5)

…If you’ve got friends you’re more likely to speak up, ask, where if you’re sitting on your own you don’t want to be the only one like oh, I don’t understand…. (female, w/c, 2014/15, FG 1)

Participants recognised the difficulties in encouraging student interaction, and while they understood the importance of university societies and social activities, they realised that this required some effort on the part of the student.

I definitely think if there was a way of getting people to chat more with each other either socially or not socially you know if there was any kind of way. (female, w/c, mature, 2015/2016, FG 4)

I don’t know cause like you said there’s already societies and things like that and pub quizzes but it depends on like are people open to the idea of actually going to the pub quizzes and are they wanting to take part cause people if they don’t want to take part they’re not going to take part and they’re not going to contribute anything if they don’t want to, you can’t make them so. (female, w/c, mature, 2015/2016, FG 4)

The need to ‘make the effort’ with people occurred in other groups, and while participants recognised that friends were important, in truth, some were very reluctant to make any attempt to form social groups. Feeling awkward was used as a justification for this.

…we’re students. We say we want to know each other but we’re not really going to make the effort. Like we don’t like making an effort with other people. Or at least I don’t try. (female, w/c, 2014/15, FG 1)

…My accommodation like is mainly foreign students so I don’t really speak to many of them…. (female, w/c, 2015/16, FG/I 5)

Some participants described difficulties making friends and named factors which impacted upon their ability to socialise. Some of these were individual, such as being a mature student, while others centred on the lack of effort among the cohort in general.

I find it difficult, because of the age gap, I find it really hard to sort of make friends…. (female, m/c, mature, 2016/17, FG 6)

…no-one really talks to each other in the seminars and stuff to get to know each other. (female,Footnote 5 2014/2015, FG 2)

While tutors could, and did, use group work and shared activities to promote discussion in groups, this was not always successful. A perceived lack of effort by others made students reluctant to initiate conversations, and feelings of awkwardness were used to support this approach. While this impacts social integration, it can also have a knock-on effect in terms of academic achievement, ultimately impacting upon academic integration. Without participation in classwork, interactive discussion or shared resources, all important elements in successful engagement in learning (Ike, 2020), students miss out on valuable opportunities to consolidate new knowledge. When the element of assessment included a group presentation, students recognised that this was a chance to make friends, but an inability to get over the initial awkwardness sometimes meant poor co-working and, in some cases, affected performance.

I think it’s cause it’s going to be awkward like sort of interacting with each other to try and like work together when you don’t know someone that well.... (male, w/c, 2014/2015, FG 1)

Every week she sits beside us but she hardly talks. I’m like well it makes it like really, really awkward that I don’t know her name…. (female, w/c, 2014/2015, FG 1)

In the above quotes, the participants disconnect their own effort from feelings of awkwardness—the latter participant could easily ask the girl her name, but does not, despite acknowledging that this makes her (and most likely the other student) feel awkward. The participant uses this awkwardness as a reason to ignore the other girl, later describing how she turns her back to her when another student arrives. In the former quote, the student suggests that you must know each other in order to interact and work together, rather than getting to know someone through the process of shared working.

Participants were divided on the best way to encourage students to form social bonds. While some stressed that having different classmates on different modules prohibited friendship-making, others recognised the exclusionary nature of cliques for those who were not part of an established group.

I think it’s difficult making friends because you’re in different seminar groups every time. Like I thought we were going to be in the same class but you’re not. You’re like I’m in different classes with different people every time so there’s not like one consistent person…. (female, w/c, 2014/2015, FG 1)

…you can see when they walk into lectures and stuff that they’ll have their own little groups or whatever, you can see the people that feel kind of isolated and such like, I still think there is still some people that will feel a bit alone in uni…and I’d say it’s kind of dangerous in a way…. (male, w/c, mature, 2016/2017, FG 6)

Despite students’ feelings of social awkwardness, the subject of criminology was a protective factor in motivating students to study.

Criminology as a protective factor

Despite students’ feelings of awkwardness raising a number of red flags for attrition, survey data showed that students were highly motivated to get a degree. This is evidenced in the responses to the question about what prevented students from dropping out of university, for example ‘want to expand my knowledge, get somewhere’ (female, w/c, survey 2, mid-semester 1). When students were asked on surveys why they chose criminology and why they did not drop out, three main reasons were found, which were also supported by data from the focus groups: (i) betterment, (ii) interest in the subject and (iii) for career opportunities. One of the reasons was to better themselves and their family’s life chances.

…I knew I wanted to get a degree to better my chances…. (female, w/c, 2014/15, FG 3)

Relatedly, students sometimes cited personal experience of the criminal justice system and a desire to make things better or help people as a motivation for studying criminology (see also Trebilcock & Griffiths, 2021).

…I’m talking quite a few years ago my son was a young offender and the things that we went through, I thought if I can go in there and change something or help a service somewhere, then I want to do that because it wasn’t very good at the time. (female, m/c, mature, 2016/17, FG 6)

I want to make society better even a little bit. (female, w/c, White Other, mature, survey 1, start of programme)

Participants often cited ‘interest’ as a reason for studying criminology; thus, if students maintain interest in the topic, criminology might be understood as a protective factor against attrition (see also Trebilcock & Griffiths, 2021). Students were keen to build on their existing interests.

I was really interested in crime. (female, w/c, 2014/15, FG 1)

…criminology had more open doors and I was more interested because if I wanted to go into something else later on in life I could so. (female, w/c, 2015/16, FG/I 5)

As the last quote above alludes, participants were also concerned with future career opportunities and recognised that criminology paved the way to a number of different roles.

I either want to work with young offenders or go into probation but now I’m thinking about maybe with young children and like safeguarding or something like that. (female, w/c, mature, 2015/16, FG 4)

…I’ve always liked a career like working with criminals or the police force or things like that, so it seemed like a suitable subject. (male, w/c, mature, 2016/17, FG 6)

Thus, students described strong rationale for choosing criminology based on current interests or future aspirations. The following section discusses the implications of the findings of physical or geographic, academic and social awkwardness, and criminology as a protective factor, for student retention.

Discussion

To view the findings presented here through Tinto’s lens (1975, 1993), many of the students interviewed for this study appeared to perceive awkwardness: physical or geographic, academic and social, as an insurmountable barrier to full integration into university life. While they were motivated to be students, many were unwilling to adjust their familiar habitus in the new field of university, preferring to maintain employment, family or friendship connections related to their pre-university life (Christie et al., 2005). This unwillingness to detach from the old in order to fully embrace the new meant that students were ‘caught between two worlds’ (Guiffrida, 2004 p.6), which hindered their transition and left them inhabiting the liminal space between competing identities. Frequent trips to the family home and a reliance on old friends meant that students were not around to engage in social or extra-curricular activities that would have helped them to make friends and create a support network – a crucial factor in continued engagement (Holdsworth et al., 2017; Scanlon et al., 2007; Tinto, 1975, 1993; Wray et al., 2014). An avoidance of talking to new people in the first few weeks due to awkwardness, meant that the discomfort was never fully resolved. It might then be concluded that this created a self-perpetuating cycle in which students went home because they felt isolated, but their isolation at university increased as a direct result of their frequent trips home. It is beyond the scope of this paper to ascertain whether this is attributable to a lack of confidence, personal characteristics of the student, family dynamics or issues with the institution although it may be speculated that, as with other retention studies, these factors interlink and combine. The types of awkwardness described here are produced and reproduced in a cycle, one leading to another, making it impossible to identify the origin and thus, difficult to find a resolution. Whatever the starting point, awkwardness affected social life, academic achievement, engagement in studies, inclusion, isolation and satisfaction with the course, and it was a qualitatively overarching factor in leaving university early.

It seems significant that the majority of the participants in this study self-identified as working class and would thus be considered widening participation students. As described in the literature review, such students are often at the forefront of calls for assimilation and are constructed as ‘outsiders’ by both themselves and the institution (Christie et al., 2005; Reay et al., 2001) . It is, therefore, unsurprising that they would experience the transition to HE as awkward. As Clayton et al. (2009) describe below, this awkwardness can be mitigated by maintaining familiar connections.

working-class students invest in the familiar as a form of social capital in order to alleviate the dangers associated with what has been recognised as a financially, socially and culturally ‘risky’ transition. (Clayton et al., 2009, p.157)

More recently, the onus has been on institutions to adapt to the needs of students, and in some ways, this has been successful. Additional support, social media and comprehensive induction activities were cited by participants as positive ways to help students feel at home. Yet, as students value the familiar, there is more that could be done. Students complained that changing classmates across modules meant there was little opportunity to make friends, or in other words, to familiarise. As one participant suggested, ‘there’s not like one consistent person’ across modules, meaning that students are unable to anchor themselves to familiar faces and therefore feel less awkward. Students need time to make friends, and studying different modules, each with around 3 hours of classwork per week, in semesters of 12 weeks, is maybe not enough time to establish real connections. It could be argued that more attention to seminar provision, and allocation of students therein, would support students to create bonds with classmates and decrease the feelings of starting over with each module. Similarly, social media can be utilised by institutions to foster a sense of ‘cohortness’ among new students and create an online community, which may then facilitate real-life interactions. While not knowing one’s way around can generate awkwardness, the data shows that taking steps to familiarise students with the campus and the wider city via organised induction activities and tours can help students to feel at home from their first few days.

When considering the retention of criminology students, it appears that the subject of study is an important factor, suggesting that subject-specific interventions to promote retention and engagement are needed—that in this instance, we support not just transition to student identity, but to criminology student identity specifically. The criminology curriculum can be developed to guide and support this identity transition by cultivating their interest and encouraging their career aspirations from the beginning. This can serve the dual purpose of embedding engagement (Wong & Kaur, 2018) but also providing opportunities for students to meet and socialise in both formal and informal contexts. This could take the form of implementing extra-curricular criminology activities to support social integration, forging friendships and maintaining a non-academic interest outside the classroom (see Tinto, 1993). It seems important that early induction activities support students to meet the wider cohort and to break the ice in the first few sessions—such interactions could support identity transition (Renninger, 2009; Scanlon et al., 2007). This would increase the likelihood that in later modules, they would recognise a familiar face, which would ease the discomfort as they move between classes and facilitate group working.

Data also suggests that an explicitly profession-facing curriculum throughout the degree could serve to remind students of their motivations and promote continued engagement, and thus commitment to the institution, which is important for retention (Tinto, 1975). A strong vocational identity is associated with increased motivation, engagement and, concomitantly, attainment (Wong & Kaur, 2018; Wray et al., 2014) and thus serves as a protective factor. Pedagogical strategies which foster and expand existing interests from the start could encourage student integration both academically and socially and, therefore, increase retention. This could take the form of guest speakers from professional organisations such as the police, probation and prison services and/or third sector organisations. It may involve off-site visits or the promotion of placements or volunteering opportunities so that students can see criminology ‘in real life’. The course could utilise case studies as assessments, virtual teaching materials which replicate real careers and reading materials which foreground the application of knowledge. As future aspirations were a key motivation for studying criminology, reminding students how the criminology degree fits with their career goals might encourage students to persist, despite sometimes challenging personal circumstances.

Conclusion

A discourse of awkwardness is powerful in preventing students from transitioning fully into higher education. This paper has identified three types of awkwardness which affect each other, physical or geographic, academic and social, creating a knot of discomfort. Institutions can ameliorate the effects of awkwardness, but given the tangled nature, it becomes difficult to identify a single underlying cause. We argue that subject-specific strategies might be more useful in supporting student transition and aiding retention than generic institutional interventions. In programmes where motivation and interest are high, such as criminology, this could foreground the adoption of the ‘criminology student’ identity and encourage students to form a cohort identity. The implications of this paper are pertinent in the climate of the pandemic given the move to online teaching and/or hybrid models of face-to-face/online teaching as students are limited in their ability to socialise, access university amenities and get to know the city/campus. More research is needed of the impact of such a learning context upon social and academic integration of widening participation students and ultimately their retention in HEIs.

Data availability

Our data supports the claims we make. It is not appropriate to share the data as it contains non-anonymised data—participants and the location of the study are to remain anonymous.

Code availability

Not applicable.

As the research involves human participants, the study progressed through the ethics procedure at the university and was approved. Informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from participants.

Notes

There are 2 non-responses.

Mature students are defined as aged 21 or over at the start of their programme of study (UCAS, 2022).

There is 1 non-response for gender and 2 non-responses for the variables ethnicity, age and ‘moved to study’.

Social class is missing because of non-response.

Social class is missing because of non-response.

References

Aljohani, O. (2016). A review of the contemporary international literature on student retention in higher education. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 4(1), 40–52.

Ang, C., Lee, K., & Dipolog-Ubanan, G. F. (2019). Determinants of first-year student identity and satisfaction in higher education: A quantitative case study. Sage open, 9(2) https://doi.org/10.1177/2F2158244019846689

Bennett, R., & Kane, S. (2010). Factors associated with high first year undergraduate retention rates in business departments with non-traditional student intakes. The International Journal of Management Education 8(2), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.3794/ijme.82.276

Bourdieu, P. (2010). Distinction. Routledge.

Chamberlain, J. M. (2012). Grades and attendance: Is there a link between them with respect to first year undergraduate criminology students? Educational Research and Reviews, 7(1), 5–9. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR10.165

Christie, H., Munro, M., & Wager, F. (2005). ‘Day students’ in Higher Education: Widening access students and successful transitions to university life. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 15(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620210500200129

Clayton, J., Crozier, G., & Reay, D. (2009). Home and away: Risk, familiarity and the multiple geographies of the higher education experience. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 19(3–4), 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09620210903424469

Cotton, D. R. E., Nash, T., & Kneale, P. (2017). Supporting the retention of non-traditional students in Higher Education using a resilience framework. European Educational Research Journal, 16(1), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116652629

Du Plessis, M. & Benecke, R. (2011) Risk, resilience and retention: A multi-pronged student development model. The Journal of Independent Teaching and Learning, 6.

Gazeley, L. & Aynsley, S. (2012). The contribution of pre-entry interventions to student retention and success. A literature synthesis of the Widening Access Student Retention and Success National Programmes Archive. https://www.heacademy.ac.uk/system/files/WASRS_Gazeley_0.pdf Accessed 09.09.21

Guiffrida, D. A. (2004). Friends from home: Asset and liability to African American students attending a predominantly White institution. NASPA Journal, 24(3), 693–708.

HESA (2021) Non-continuation: UK performance indicators https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/performance-indicators/non-continuation. Accessed 22.02.22

Holdsworth, S., Turner, M., & Scott-Young, C. M. (2017). Not drowning, waving. Resilience and University: A Student Perspective, Studies in Higher Education, 43(11), 1837–1853. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1284193

Ike, T. J. (2020). ‘An online survey is less personal whereas I actually sat with the lecturer and it felt like you actually cared about what I am saying’: A pedagogy-oriented action research to improve student engagement in Criminology. Educational Action Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2020.1850498

Kehm, B. M., Larsen, M. R., & Sommerset, H. B. (2019). Student drop out from universities in Europe: A review of empirical literature. Hungarian Educational Research Journal, 9(2), 147–164.

Kotsko, A. (2010). Awkwardness: An Essay. Zero Books.

MacFarlane, K. (2018). Higher education learner identity for successful student transitions. Higher Education Research and Development, 37(6), 1201–1215.

Maher, M., & McAllister, H. (2013). Retention and attrition of students in higher education: Challenges in modern times to what works. Higher Education Studies, 3(2), 62–73. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v3n2p62

Maisuria, A., & Cole, M. (2017). The neoliberalization of higher education in England An alternative is possible. Policy Futures in Education, 15(5), 602–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1478210317719792

McQueen, H. (2009). Integration and regulation matters in educational transition: A theoretical critique of retention and attrition models. British Journal of Education Studies, 57(1), 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2008.00423.x

Merrill, B. (2014). Determined to stay or determined to leave? A tale of learner identities, biographies and adult students in Higher Education. Studies in Higher Education, 40(10), 1859–1871. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.914918

Mier, C. (2018). Adventures in Advising: Strategies, solutions and situations to student problems in the criminology and criminal justice field. International Journal of Progressive Education, 14(1), 21–31.

Pennington, C. R., Bates, E. A., Kaye, L. K., & Bolam, L. T. (2018). Transitioning in higher education: An exploration of psychological and contextual factors affecting student satisfaction. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(5), 596–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1302563

Reay, D., David, M., & Ball, S. (2001). ‘Making a difference?’ Institutional habituses and higher education choice. Sociological Research Online, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.5153/2Fsro.548

Renninger, K. A. (2009). Interest and identity development in instruction: An inductive model. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520902832392

Russell, L., & Jarvis, C. (2019). Student withdrawal, retention and their sense of belonging; their experience in their words. Research in Educational Administration and Leadership, 4(3), 494–525.

Scanlon, L., Rowling, L., & Weber, Z. (2007). ‘You don’t have like an identity … you are just lost in a crowd’: Forming a student identity in the first-year transition to university. Journal of Youth Studies, 10(2), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676260600983684

Tight, M. (2020). Student retention and engagement in higher education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 44(5), 689–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2019.1576860

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. Second Edition. University of Chicago Press.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89–125. https://doi.org/10.3102/2F00346543045001089

Trebilcock, J. & Griffiths, C. (2021). Student motivations for studying Criminology: A narrative inquiry. Criminology and Criminal Justice. OnlineFirst. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895821993843

UCAS (2022) Mature Students’ Guide. https://www.ucas.com/file/35436/download?token=2Q6wiw-L#:~:text=Mature%20students%20are%20defined%20as,when%20they%20commence%20their%20courses. Accessed 09.02.22

Webb, O., Wyness, L. & Cotton, D. (2017). Enhancing access, retention, attainment and progression in Higher Education: A review of the literature showing demonstrable impact. York: Higher Education Academy.

Wilcox, P., Winn, S., & Fyvie-Gauld, M. (2005). ‘It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people’: The role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(6), 707–722. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070500340036

Wong, B. (2018). By Chance or by Plan?: The academic success of nontraditional students in higher education. AERA Open, 4(2) https://doi.org/10.1177/2F2332858418782195

Wong, Z. Y., & Kaur, D. (2018). The role of vocational identity development and motivational beliefs in undergraduates’ student engagement. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 31(3), 294–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2017.1314249

Wray, J., Aspland, J., & Barrett, D. (2014). Choosing to stay: Looking at retention from a different perspective. Studies in Higher Education, 39(9), 1700–1714. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2013.806461

Zepke, N., & Leach, L. (2005). Integration and adaptation: Approaches to the student retention and achievement puzzle. Active Learning in Higher Education, 6(1), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1469787405049946

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Matthew Durey for conducting the initial focus groups.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

While the second author has designed the study and gathered the data, the lead author has led the qualitative data analysis and writing of the manuscript, with the second author also contributing to these processes.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable—the authors have no conflicts of interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. The site of research and participants therein are anonymised.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, H., Roberts, N. ‘I just think it’s really awkward’: transitioning to higher education and the implications for student retention. High Educ 85, 1125–1141 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00881-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00881-1