Abstract

In this paper, we analyse social inequalities along the horizontal dimension of education in Italy. More precisely, we focus on the role of family background in completing specific fields of study at both secondary and tertiary levels of education. To mitigate the limitations of the traditional sequential model, we construct a typology of educational paths based on two axes: the prestige of one’s choice of high school track (academic or vocational) and the labour market returns of the university field of study in terms of monthly net income (high or low). We identify four paths: academic-high, academic-low, vocational-high, and vocational-low. We investigate the influence of social inequalities on educational path using data from the Istat “Survey on the transition to work of University graduates” regarding cohorts of university graduates in 1995, 1998, 2001, 2004 and 2007. Results obtained from multinomial logistic regressions confirm predictions based on rational action theory. We find that family background, defined in terms of parental education, is positively and significantly associated with the completion of the most advantageous educational path. Moreover, we find that high-performing students from lower socio-economic backgrounds show a higher probability of completing the vocational-high path. This result suggests that a vocational upper secondary degree could be perceived as a sort of safety option for students from less wealthy families, which allows them to invest in the most lucrative and risky fields at university.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The impact of family background on individual educational careers is a crucial concern for research on social stratification and inequality. Traditionally, the analysis of an individual’s educational career is carried out with sequential models (Mare 1980, 1981; Shavit and Blossfeld 1993) and focuses on successive transitions between the various levels of education in an educational system. This approach has been criticised mainly for two reasons. From a methodological point of view, it has been shown that the application of the Mare model could lead to biased estimates due to dynamic selection (Cameron and Heckman 1998). The bias arises as the students’ population that make each school transition is not a random subset of all observations in an entry cohort of students (Mare 2011). From a theoretical point of view, the sequential model focuses on the vertical dimension of educational inequalities and considers the horizontal dimension (i.e. the choice of field of study) to be of marginal interest only (Breen and Jonsson 2000; Lucas 2001). In contemporary Western countries, however, a large proportion of students reach the tertiary level of education due to educational expansion. As a result, social scientists have increasingly paid attention to the available choices in terms of field of study at various levels in the educational system (Davies and Guppy 1997; Goyette and Mullen 2006; Zarifa 2012; Triventi 2013). As previous studies have noted, educational expansion does not necessarily reduce social inequality because lower-class students may still complete degrees in fields with a lower economic return than upper-class students (Shavit et al. 2007; Lucas 2001). As a result, it is still important to study whether and how social origins play a role in individual educational careers in contemporary societies. In light of these findings, we propose an alternative to the educational transition approach for studies on the relationship between social origins and inequality in degree completion. More precisely, we combine the field of study at upper secondary education with the one at the university level in order to construct a typology of educational paths that reflects the complexity of individual trajectories within the current educational system. Next, we use our typology as the main dependent variable to assess the impact of social origins. We believe that the Italian education system may be particularly suitable to our purposes because it is horizontally differentiated both at the secondary and at the tertiary level, whereas access to university education is granted to every student regardless of the track they completed during their upper secondary education.

The structure of the paper is as follows: in the “The Italian educational system” section, we describe the main features of the Italian educational system. In the “Previous studies and theoretical framework” section, we review the relevant literature on the role of social origins in both vertical and horizontal inequalities in education, and we present our research hypotheses. “Data, variables and empirical strategy” section describes the data used and its main variables, and the empirical analyses are presented in “Empirical results” section. Finally, “Conclusion and discussion” section summarises the main findings and concludes the paper.

The Italian educational system

Education in Italy is compulsory for children between 6 and 16 years of age.Footnote 1 It is divided into four stages: primary school, lower secondary school, upper secondary school and tertiary education. Primary school (Isced 1) is compulsory and lasts for 5 years. It is intended for children from 6 to 11 years of age and offers general education to all students on the basis of the same curricula. Secondary education is divided into two levels. The lower level (Isced 2) is compulsory and lasts for 3 years, usually until students are 14 years old. Education at this stage is still undifferentiated: schools across the country provide students with the same general competencies. Upper secondary school (Isced 3) is the first stage that uses tracks. There are three available tracks: the academic (liceo), the technical (istituto tecnico) and the vocational track (istituto professionale).

Each track lasts 5 years and ends with an examination of competency known as the Esame di Maturità. This consists of three written tests plus an oral examination, which together form a final mark between 0 and 100, with the minimal threshold being 60. Each written test provides a maximum of 15 points, while the oral examination gives a maximum of 30. The remaining 25 points depend on previous scholastic career. The first two written tests are designed by the national Ministry of Education, while the design of the remaining written test is left to each individual school, as well as the conduction of the oral examination. Both written and oral examinations are overseen by a specific committee where only four members out of seven are external examiners. All students who pass this final exam have the possibility to enrol at university independent of which track they completed. Some vocational schools offer 3 years qualifications, although these do not grant access to university. As these schools are managed by local governments, their regulations can vary by region. For example, in some regions, special rules allow students to take the Esame di Maturità after the completion of additional courses, in order to have access to tertiary education. As reported in Fig. 1a, the share of upper secondary school graduates from the academic track increased of about 12 % points in the last decades, contrary to a reduction in the number of graduates from the technical field.

Italian upper secondary school graduates by track (a) and gross enrolment rate at university (b). Source: Italian Ministry of Education. Note: the gross enrolment rate is the ratio of all individuals enrolling for the first time at university in the academic year t/t + 1 to the number of those who passed the final upper secondary school exam in the school year t − 1/t. The vertical line in b indicates the year of implementation of the Bologna Process

Higher Education (Isced 5A) in Italy underwent a big change in 2001 after the implementation of the Bologna Process. The pre-reform system was unitary and undifferentiated, and it was characterised by long courses with a high workload. More precisely, tertiary education was only available in the form of a unitary tier, consisting of 4–6 years long degrees (depending on the field of study). Even though a law in 1990 gave universities the opportunity to provide also 2- or 3- year degrees (called Diplomi Universitari), the majority of the Universities choose not to implement these shorter programs (Ballarino and Perotti 2012). As a result, in 2000 tertiary education was still affected by the previous high dropout rates, low proportion of university graduates on the total population, average length of study above the legal duration, and lower graduation rates of students from disadvantaged families (Argentin and Triventi 2011). The Bologna Process replaced this old system with a sequential 3 + 2, which comprises a 3-year Bachelor’s, resulting in the laurea triennale, and a 2-year Master’s that leads to the laurea magistrale. Only the latter degree grants access to doctoral programs. With the Bologna Process, the students’ workload is better defined both in terms of content and credit. The reform resulted in a less selective system and reduced the time and effort needed to complete university courses. The gross enrolment rate at university increased sharply after 2000, and remained above 70 % in the recent cohorts (Fig. 1b). Finally, as in the pre-reform period, the Italian Higher Education system is mainly public and not stratified, which means that all universities officially provide the same level of qualification.Footnote 2 The differences between universities in terms of prestige and reputation are practically negligible compared to other education systems characterised by the presence of elite institutions, such as those in the USA, UK and France. Consequently, the choice of a specific field becomes particularly relevant in the case of Italian education.

Previous studies and theoretical framework

Italy, just like other Western European countries, has, in the last decades, experienced a period of sustained educational expansion that is connected to an improvement in the general economic conditions of the population. These developments, however, have not led to a complete disappearance of inequality in the educational opportunities (IEOs) of children from different social backgrounds. Despite the detection of a decline of IEOs in a number of countries (Breen et al. 2009, 2010), family background still represents an important predicting factor for individual attainments (Bukodi and Goldthorpe 2013; Marzadro and Schizzerotto 2014). Following rational action theory and the relative risk-aversion specification (Boudon 1974; Breen and Goldthorpe 1997), IEOs can be seen as the result of different perceptions of the cost and the utility of educational choices by students from different social backgrounds. Thus, by taking the high social position of their parents into account, pupils from wealthy families are inclined to invest a lot in education in order to avoid the risk of downward mobility associated with a lower educational degree. Their greater access to economic resources, moreover, allows them to pursue a degree for longer without having to go on the labour market, thus reducing opportunity costs. In contrast, the lower level of resources of children from less advantaged families results in a higher perception of the costs associated with a longer investment in education. In addition, the risk of downward mobility with respect to their parents’ social position can also be avoided with a lower educational degree that carries fewer possibilities of failure. According to Bourdieu (1979) and Bourdieu and Passeron (1990), the choice of a particular field of study is also connected to the educational resources at home. In fact, this choice is influenced by parental knowledge and experience with the higher education system. Hence, students with highly educated parents will have more information not only on the working of the higher education system but also on the economic returns of different fields of study.

The most common strategy adopted by social scientists to empirically test these theoretical propositions relies on the so-called “sequential model” developed by Mare (1980). The model considers an individual’s educational career as a sequence of successive transitions, each of which take the form of a “yes–no” decision to continue on to the next level of education. This very convincing simplification of an individual’s pathway through the educational system has proven to be extremely useful in the analysis of IEOs (Shavit and Blossfeld 1993). The model’s efficacy, however, is highest for the older cohorts of individuals, who completed their studies when inequalities were mainly distributed along the vertical dimension of education. Current students in Western countries, instead, obtain their tertiary degree in a context where the majority of their peers reach the same educational level. Thus, as a result of this educational expansion, the importance of the qualitative dimension of education has increased. In contrast to the past, specific fields of study have become increasingly linked to the occupational outcomes of a degree (Müller 2005; Reimer et al. 2008; Triventi 2013). With respect to the Italian case, Pisati (2002) found substantial differences in the outcomes of different secondary fields of study chosen by recent cohorts of students: the academic field assures both a higher probability of enrolling in a university and a higher occupational return on the labour market. Ballarino and Checchi (2006) have found similar results, which suggest that secondary school tracks are, at the moment, crucial to both the whole study career and per se. Considering the growing importance of the qualitative dimension of education, more and more scholars have started to interpret it as a new potential source of social inequality in education.

In Italy, Schizzerotto and Barone (2006), Pisati (2002) and Checchi and Flabbi (2007) found that children from wealthy families are more likely to choose the most lucrative fields of study not only at the secondary but also at the tertiary level. The tendency of pupils from lower social origins to choose less remunerative fields of study may be explained by Lucas’s Effectively Maintained Inequality (EMI) hypothesis (Lucas 2001). By using the theoretical framework of rational action, Lucas claims that well-off families make all the necessary decisions to maintain their relative advantage throughout pupils’ education, and they do not limit themselves to the vertical dimension of education if it does not guarantee protection from the risk of downward mobility. More precisely, Lucas (2001) argues that elites will use their higher economic and cultural capital to provide their offspring with the highest level of education if there are significant vertical inequalities. However, if the enrolment rate at an educational level is very high, wealthy parents will use their greater material and immaterial resources to ensure that their children obtain the best positions within the same educational level, namely the most prestigious fields of study. One possible channel is the inter-generational transmission of motivation towards the choice of field of study. As Reay et al. (2001) point out, students’ beliefs on what is suitable for them to study are influenced by social origin. As a result, students from high-income families tend to choose high wage premium subjects more frequently, coherently with the greater importance they assign to the expected earning returns of their choice (Davies et al. 2013). In line with this finding, Delaney et al. (2011) report the presence of a large premium in both the short-run and the long-run earnings expectations for students with high socio-economic status with respect to their less advantaged peers.

Following the outlined theoretical approach, we argue that well-off families that try to maintain their relative advantage may not perceive the educational career of their offspring as a sequence of choices to invest or not invest in a single additional year of education. On the contrary, they may see educational careers as a pre-determined path; such families assume graduation will take place and combine the best available qualitative options at each educational level. Having a higher ability to gather information on the functioning of the educational system and the future economic returns of the degrees (Bourdieu 1979; Davies et al. 2013), well-off families are more capable of selecting the best path to graduation for their children. In addition, they are able to mobilise greater economic resources to help their children remain on that path (Bernardi 2014). Summing up, we hypothesise that:

H1

With respect to their less advantaged peers, students from higher social origins will graduate after following the more prestigious and remunerative path.

To the best of our knowledge, there are very few studies on the social stratification in education that apply an approach based on educational paths instead of the more common sequential model of educational transitions. In a recent study, Reisel (2011) focuses on college degree attainment in the United States and in Norway, with a specific interest in the vertical dimension of education. She finds a positive influence of social origins on completing the path leading to college graduation with respect to other less prestigious paths in both countries. Another relevant study is Breen and Jonsson’s research on education in Sweden (Breen and Jonsson 2000). Contrary to Reisel, the authors stress the importance of the qualitative dimension in the educational system; the university graduation varies greatly according to the previous path followed by a student, which, in turn, is positively influenced by social class.

In this paper, we contribute to the existing debate testing the influence of social origins on the educational paths of students in Italy, a country where the educational system can be seen as a mixture of the comprehensive system, presented in studies of Nordic and Anglo-Saxon countries, and the continental system. In addition, we exploit the specificity of the Italian educational system to directly test an additional hypothesis. As mentioned above, in Italy, social origin is positively associated with the upper secondary field of study, meaning that children from a lower social background have a higher probability of choosing a technical or vocational education (Ballarino and Checchi 2006). Because access to an Italian university is granted to all students with a 5-year secondary education Diploma, regardless of the field of study, the technical track represents a less risky option (Panichella and Triventi 2014). Not only can it provide access to tertiary education, but it also enables direct entry into the labour market without any additional qualification. Applying our path approach with these considerations in mind, we argue that worthy students from families that are risk-averse and who are over-represented in the lower social strata may see the technical upper secondary degree as a safety net to the risk of dropping out from a prestigious and demanding university course. This argument leads us to formulate our second hypothesis:

H2

High-performing students from a disadvantaged social background will more frequently follow the path that combines a vocational secondary education with a high-profile university degree than any other path available.

Data, variables and empirical strategy

The data used in this study are provided by the last five editions of the “Survey on the Transition to work of University Graduates” (STUG henceforth). STUG is a repeated cross-sectional study of wide samples of Italian college graduates conducted by the National Statistical Office (Istat). The first survey we use was carried out in 1998 and was repeated every 3 years since then. By means of CATI, each STUG collects information on the school and work careers of university graduates, 3 years after they graduated in 1995, 1998, 2001, 2004, and 2007. Thus, the first three STUG surveys only include graduates from the pre-reform system. Students graduated in 2004 could have, instead, obtained either the traditional pre-reform degree or a bachelor’s degree. Finally, the last wave comprises students with either: a bachelor’s degree, a master’s degree, or a so-called single-cycle degree. In order to have comparable results, we decided to run the analysis only on graduates with either a master’s, a traditional or a single-cycle degree. Not only are master’s and single-cycle degrees equivalent by law to the pre-reform degrees, but they have also graduates with very similar parental education and upper secondary school track.Footnote 3 Changes in opportunity costs in investing in education after the Bologna process in Italy seems, after all, to have modified the composition of bachelor’s graduates to the greater extent.Footnote 4

Dependent variable: educational path

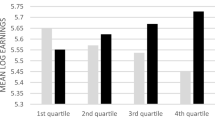

As mentioned above, we conceptualise the educational path (our dependent variable) as a combination of the specific degrees obtained at both the secondary and tertiary level. It jointly considers two different phases that we, for simplicity, consider as dichotomous. The student, in the first step, completes an academic or a vocational track at a high school, and in the second step he/she earns a degree in a particular field of study at the university level. We differentiate university fields of study according to their occupational returns in terms of expected earnings, as suggested by Davies and Guppy (1997) and Zarifa (2012). Hence, our dependent variable is a typology that identifies four different pathsFootnote 5: (a) academic-high occupational returns, (b) academic-low occupational returns, (c) vocational-high occupational returns and (d) vocational-low occupational returns. The occupational returns are computed using data from the Survey on Household Income and Wealth (SHIW) carried out by the Bank of Italy starting from the 1970s to today. We use information on the real annual net income of Italian university students after graduation to rank the different degrees. The measure of annual net income allows us to jointly consider employees’ wages as well as self-employed and professionals’ earnings. As a result, we are able to include in the analysis of occupational returns any possible graduates’ occupational position. In addition, income has been adjusted for the prices index supplied by Istat, allowing us to draw comparisons between the various waves. Calculations were performed on data from 1995 to 2012, on 2,594 individuals aged between 35 and 45 years in order to consider the long-run potential returns. We choose this observation window for its overlap with the STUG surveys. Moreover, information on the field of study is available in the SHIW only from the 1995 survey onwards. We consider the long-run occupational returns of the fields of study in order to avoid biased estimates caused by periods of apprenticeship, which decrease the short-term average remuneration in some fields, such as law and medicine. We employ the annual net income as the dependent variable of an OLS regression model having the field of study as main explanatory variable, and sex, geographic area of residence, age, social class and wave as controls. Thus, it becomes possible to obtain the net average economic return for each academic field. In Fig. 2, we report the main results of this analysis. We present the economic returns of the various fields of study along three different periods to take into account their possible variations over time. Due to the SHIW sample size, we have to group adjacent waves to have reliable estimates. Generally speaking, it is clear that the more lucrative fields of study are those connected to STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), and the ones that lead to liberal professions. Conversely, the less remunerative fields are connected to the humanities and social sciences. In Fig. 2, we see some exceptions to these general results. First, the Scientific and the Agricultural fields, in one case, show returns that are below average. Other exceptions are the fields of Architecture and Economics & Statistics. Architecture, even if it provides access to a liberal profession, yields economic returns that are always below the average income. On the other side, Economics & Statistics yield economic returns that are above the average. Hence, we consider as “high remunerative” the following fields: scientific, agriculture, medicine, engineering, economics and statistics and law. The other fields (architecture, social sciences, humanities and other) are labelled as “low remunerative”. The general objective is to consider those fields of study that always fall below the average income as not lucrative.Footnote 6

Independent variables

Our main independent variable is parental education, which consists of four categories: (a) primary degree, (b) lower secondary degree, (c) upper secondary degree, and (d) university degree. This is considered as a proxy for the educational resources of the family, namely the parents’ ability to foster the educational career of their children, to provide a stimulating learning environment, and to provide information on the functioning of the educational system in order to facilitate educational choices (Bukodi and Goldthorpe 2013). In order to measure parental education, we consider the educational degree of both the father and the mother. In particular, according to the dominance criterion, parental education is determined by the higher educational degree between the two parents (Erikson 1984).Footnote 7 As control variables, we also looked at sex, geographic area of residence (North–West; North–East; Centre and South and Islands), and parental social class (service class; white collar; self-employed; and working class).Footnote 8

Empirical strategy

As two distinct research hypotheses are tested, the section on empirical results is divided in two. In the first part, we look at the influence of social origins on the educational paths. Differently from Breen and Jonsson (2000) who employ a multinomial transition model to estimate the available choices at each transition controlling for previous paths, we follow the analytical strategy suggested by Reisel (2011). Hence, we estimate a multinomial logistic regression in order to simplify our analysis and to highlight the comparison between the different paths and cohorts considered. This approach also allows us to better measure the association between social origins and educational path considered as a whole. The models have been run separately for each cohort of graduates.

In order to facilitate the interpretation of the results, we present the main parameters graphically and we compute average marginal effects (AME henceforth) to overcome problems that arise in comparing logit coefficients and odds ratios across different groups and cohorts (Allison 1999). Moreover, AMEs are easy to interpret because they represent the average differences in the probability to complete a particular path between social categories calculated in percentage points.

In the second part, we test the hypothesis about the choice of the technical track at upper secondary school as a safety option. In order to test this idea, we use a linear probability model (OLS) that considers as dependent variable the likelihood to complete a high-remunerative field of study and as main predictor the three-way interaction between the upper secondary school track, parental education, and the final mark at the Esame di maturità. We are particularly interested in the three-way interaction between these variables, as it can shed light on the completion of a specific tertiary field of study for students from lower social background with a technical high school diploma, as their final grade increases. As we employ a linear probability model (OLS) with robust standard errors, even in this case the parameters can be interpreted in terms of probability differences.

Empirical results

Hypothesis 1: The association between parental education and educational path

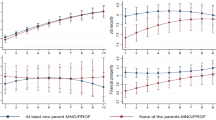

In Fig. 3 we look at the association between social origins, measured by parental education, and the completion of a given educational path.Footnote 9 The findings for the academic-high path provide confirmation of our first hypothesis: children of parents with a higher education degree are significantly over represented in this path with respect to any other path available. The positive relationship between social origins and the most remunerative path is consistent during the years considered. Is remarkable to note that having parents with at least an upper secondary school degree lowers the chance of completing the academic-high path by approximately 20 % points in comparison with students whose parents have a tertiary degree. Symmetrical results can be drawn looking at the completion of the vocational-low path. Students from lower social backgrounds tend to graduate through this path significantly more frequently than their better-off peers. These results are in line with our predictions based on rational action theory and the EMI hypothesis: people from well-educated families tend to complete the best path available by choosing the more remunerative options at each educational level and thus avoiding the less prestigious ones.

By comparing the estimates for the conclusion of the academic-low path with all the other possibilities, as the AME let us do, we find no significant differences between highly educated families and the ones in which parents have a high school degree. Only students from the lowest social background are significantly under-represented here, which is consistent with their higher tendency to complete either a vocational-low or a vocational-high-remunerative path, as Fig. 3 shows. The influence of less-educated parents on the less prestigious and demanding educational choices (and thus on the competition in the vocational-low path) is in alignment with the predictions of rational action theory and with previous studies of the Italian case (Ballarino and Checchi 2006; Panichella and Triventi 2014). However, the evidence provided by our analysis of the vocational-high path tell us that students from lower social backgrounds in particular have a higher chance of completing this path than their peers from higher social origins.

Hypothesis 2: Vocational upper secondary degree as a safety option

With our second research hypothesis, we argued that high-performing students from risk-averse families may see a vocational secondary degree as a safety net for the risk of dropping out from the prestigious but demanding university courses their children would like to take. In other words, we suggest that even when families from lower social strata are inclined to prefigure an educational path that combines the less costly and risky available options for their children, if at the end of upper secondary school the child performs particularly well, the child and the family may perceive it as a signal of possible future academic success—even in academic fields that are highly remunerative and risky—and may adjust their original plans. In this respect, the possibility of relying, maybe even exclusively, on a technical qualification to find a job in case of failure at university will reduce the chance of being risk averse.

The results of the linear probability model show that high-performing children with both an upper secondary school degree in a technical track and less-educated parents are more likely to complete a prestigious university course than their peers from a more advantageous social background who completed an academic-high school track (Table 1). That similar interaction parameters are not statistically significant for the vocational track might be because some technical competencies strongly connected to some of the most lucrative fields of study (such as economics or engineering) are only offered by upper secondary technical schools, and not by vocational schools.

Conclusion and discussion

Our aim in this paper was two-fold: first, to conceptualise the upper secondary and tertiary educational choices as a unique entity and to construct a typology that comprises four possible educational paths: academic-high, academic-low, vocational-high and vocational-low, and second, to analyse the role of family background, in terms of parental education, on the completion of these paths. Our empirical evidence supports our research hypotheses, which were derived from the theoretical framework of rational action. At least with respect to the Italian case, social origins play a pivotal role in guiding students towards different paths. Children of upper strata have a higher probability of choosing the path that combines the best qualitative options available at each educational level (the academic-high path) while avoiding other less remunerative combinations. In general, parental education has a direct influence on the paths decision that is constant across the considered cohorts of students. After analysing graduates from 1995 to 2007, we did not find any substantial decrease in the importance of family educational resources on the educational path followed by students. The only exception to this general pattern of stability is a slight worsening of the situation of children with the least educated parents with respect to the completion of the most prestigious path, together with their higher chance to complete the worst possible path. In accordance with our second research hypothesis, it deserves to be highlighted that worthy students from a lower socio-economic background seem to consider the vocational track at upper secondary school as a chance to improve their condition and as a security net that gives them the possibility to invest in a lucrative and demanding field of study at university. In addition, because the vocational secondary degree provides direct access to the labour market without the necessity of any additional qualification, students might use it as a means to find a temporary job to support their education in case of lacking economic resources within their own family. Thus, the perception of the risk of failure connected to a high-remunerative faculty may be less extreme.

To conclude, we find remarkable inequalities in the various choices between educational paths. According to previous analyses of the Italian case, one possible concrete action by policy makers could be to implement the orientation process during the last year of the lower secondary school to weaken the association between social origins and educational path choices. Such actions may spread information on the profitability and workload of the various fields of study (Azzolini and Vergolini 2014; Barone et al. 2015). These informational issues may turn out to be crucial if we keep in mind the strong influence of family educational resources. Consequently, such actions should be extended also to the parents because it has been proven that educational decisions occur within the family. In this way, people from lower strata will also have reliable information on the functioning of the educational system and on the actual difficulties of the more lucrative fields of education.

Notes

Take note that the Italian law states that compulsory schooling lasts until the age of 15, but there is also a compulsory training that includes the first 2 years of upper secondary school. In other words, a student can leave the upper secondary school at age 15, but he/she is obliged to enrol in a training course for at least another year.

There are a few notable exceptions in certain fields; private universities, such as Bocconi for economics and the Scuola Normale for maths, are perceived to be more prestigious than the other universities.

As a robustness check, we have run our analysis on all the different subpopulations separately, finding similar results for both master’s and single-cycle graduates, and between these and the pre-reform graduates. Even if the results for bachelor’s graduates are different, the results show that they do not move away from the general pattern. The robustness checks are available in the supplementary materials.

A complete set of descriptive statistics is reported in the Supplementary Materials.

Another option is to consider the occupational returns in a dynamic way by letting it vary over time. As seen in the supplementary materials, however, even in this case the main results of the paper are confirmed.

E.g., where the highest educational degree of the father is a high-school diploma and the highest educational degree of the mother is a university degree, parental education will be the mother’s education qualification.

We do not consider social class as the main explanatory variable in our analysis, as the information about parental occupation is supplied in a way that does not permit the construction of a detailed class scheme. To avoid possible problems of miss-classification, we code occupation in a few categories and use it only as a control variable.

The complete models are reported in the supplementary materials.

References

Allison, P. D. (1999). Comparing logit and probit coefficients across groups. Social Methods & Research, 28(2), 186–208.

Argentin, G., & Triventi, M. (2011). Social inequality in higher education and labour market in a period of institutional reforms: Italy, 1992–2007. Higher Education, 61(3), 309–323.

Azzolini, D., & Vergolini, L. (2014). Tracking, inequality and education policy. Looking for a recipe for the Italian case. Scuola Democratica, 2. doi:10.12828/77685.

Ballarino, G., & Checchi, D. (Eds.). (2006). Sistema scolastico e disuguaglianza sociale: Scelte individuali e vincoli strutturali. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Ballarino, G., & Perotti, L. (2012). The Bologna process in Italy. European Journal of Education, 47(3), 348–363.

Barone, C., Schizzerotto, A., Abbiati G., & Argentin, G. (2015). Does information matter? Experimental evidence on the role of beliefs on the value of higher education and the choice of the field of study. Paper presented at the RC28 meeting, Tilburg. 28–30 May.

Bernardi, F. (2014). Compensatory advantage as a mechanism of educational inequality. A regression discontinuity on month of birth. Sociology of Education, 87(2), 74–88.

Boudon, R. (1974). Education, opportunity, and social inequality. New York: Wiley.

Bourdieu, P. (1979). La distinction: Critique sociale du jugement. Paris: Edition de Minuit.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture. London: Sage.

Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials: Toward a formal rational action theory. Rationality and Society, 9(3), 275–305.

Breen, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (2000). A multinomial transition model for analyzing educational careers. American Sociological Review, 65(5), 754–772.

Breen, R., Luijkx, R., Muller, W., & Pollak, R. (2010). Long-term trends in educational inequality in Europe: Class inequalities and gender differences. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 31–48.

Breen, R., Luijkx, R., Müller, W., & Pollak, R. (2009). Nonpersistent inequality in educational attainment: Evidence from eight European countries. American Journal of Sociology, 144(5), 1475–1521.

Bukodi, E., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (2013). Decomposing ‘Social Origins’: The effects of parents’ class, status, and education on the educational attainment of their children. European Sociological Review, 29(5), 1024–1039.

Cameron, S. V., & Heckman, J. J. (1998). Life cycle schooling and dynamic selection bias: Models and evidence for five cohorts of American males. The Journal of Political Economy, 106(2), 262–333.

Checchi, D., & Flabbi, L. (2007). Intergenerational mobility and schooling decisions in Germany and Italy: The impact of secondary school tracks. IZA DP No. 2876, Bonn.

Davies, S., & Guppy, N. (1997). Fields of study, college selectivity, and student inequalities in higher education. Social Forces, 75(4), 1417–1438.

Davies, P., Mangan, J., Hughes, A., & Slack, K. (2013). Labour market motivation and undergraduates’ choice of degree subject. British Educational Research Journal, 39(2), 361–382.

Delaney, L., Harmon, C., & Redmond, C. (2011). Parental education, grade attainment and earnings expectations among university students. Economics of Education Review, 30, 1136–1152.

Erikson, R. (1984). Social class of men, women and families. Sociology, 18(4), 500–514.

Goyette, K. A., & Mullen, A. L. (2006). Who studies the arts and sciences? Social background and the choice and consequences of undergraduate field of study. The Journal of Higher Education, 77(3), 497–538.

Lucas, S. R. (2001). Effectively maintained inequality: Education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. American Journal of Sociology, 106(6), 1642–1690.

Mare, R. D. (1980). Social background and school continuation decisions. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 75(370), 295–305.

Mare, R. D. (1981). Change and stability in educational stratification. American Sociological Review, 46(1), 72–87.

Mare, R. D. (2011). Introduction to symposium on unmeasured heterogeneity in school transition models. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 29(3), 239–245.

Marzadro, S., & Schizzerotto, A. (2014). More stability than change. The effects of social origins on inequalities of educational opportunities across three Italian birth cohorts. Scuola Democratica, II, 2, 343–364.

Müller, W. (2005). Education and youth integration into European labour markets. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 45(5–6), 461–485.

Panichella, N., & Triventi, M. (2014). Social inequalities in the choice of secondary school. Long-term trends during educational expansion and reforms in Italy. European Societies, 16(5), 666–693.

Pisati, M. (2002). La partecipazione al sistema scolastico. In A. Schizzerotto (Ed.), Vite ineguali. Disuguaglianze e corsi di vita nell’Italia contemporanea (pp. 141–186). Bologna: Il Mulino.

Reay, D., Davies, J., David, M., & Ball, S. J. (2001). Choices of degree or degrees of choice? Class, race and the higher education choice process. Sociology, 35(4), 855–874.

Reimer, D., Noelke, C., & Kucel, A. (2008). Labor market effects of field of study in comparative perspective. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 49(4–5), 233–256.

Reisel, L. (2011). Two paths to inequality in educational outcomes: Family background and educational selection in the United States and Norway. Sociology of Education, 84(4), 261–280.

Schizzerotto, A., & Barone, C. (2006). Sociologia dell’Istruzione. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Shavit, Y., Arum, R., & Gamoran, A. (Eds.). (2007). Stratification in higher education. A comparative study. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Shavit, Y., & Blossfeld, H.-P. (Eds.). (1993). Persistent inequality. Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Triventi, M. (2013). Stratification in higher education and its relationship with social inequality. Evidence from a recent cohort of European graduates. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 489–502.

Zarifa, D. (2012). Choosing fields in an expansionary era: Comparing two cohorts of baccalaureate degree-holders in the United States and Canada. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(3), 328–351.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Antonio Schizzerotto, Dalit Contini, Camilla Borgna, Giulia Assirelli, Elisa Forestan and Giampiero Passaretta for their useful suggestions and comments on a previous version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vergolini, L., Vlach, E. Family background and educational path of Italian graduates. High Educ 73, 245–259 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0011-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0011-2