Abstract

Research on groups in organizations has regularly identified the presence of favoritism toward members of one’s ingroup. Identity with a social group helps understand this bias, yet the mechanisms that may undermine the process have not been well documented. This study investigates the effect that not adhering to group expectations has on the positive bias otherwise awarded ingroup members, thus extending the literature on social identity theory and intragroup dynamics. Given that ingroup members, as compared to outgroup members, are expected to reciprocate loyalty and trust, this study examines what happens to the bias for the ingroup member that does not adhere to group expectations. Results from an intergroup negotiation experiment support the hypotheses that breaching group norms minimizes the ingroup bias effect. More importantly, results revealed a reversal of the ingroup bias, whereby ingroup members who did not uphold group expectations were evaluated more negatively than outgroup members.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Effectively functioning groups help organizations accomplish important tasks and achieve high levels of performance. That explains the increased prevalence of teams found within organizations. Thus, understanding what contributes to effective cohesive groups is critically important. A preference for ingroup (as opposed to outgroup) members is a well-established phenomenon in social psychology, and provides some evidence for why and how groups function effectively. According to social identity theory (SIT) (Tajfel 1978), individuals identify with the group to which they belong and as a result develop an ingroup bias. This paper examines whether this bias for ingroup members is negatively affected by aspects of the situation; specifically, how non-adherence to group norms can diminish the bias. Positive perceptions shared among members within a group, relative to perceptions of those in outgroups, are suggested to positively influence citizenship behaviors (Abid et al. 2015), positive attributions (Turner 1985), trust (Navarro-Carrillo et al. 2018), cooperation (Simpson 2006), liking (Hogg 2001), team performance (Hoegl et al. 2004; Mathieu et al. 2015), cohesiveness and friendship (Hogg and Hains 1998). To date however, research has not thoroughly examined how ingroup member behavior influences that bias. The purpose of this study is to fill this gap in the literature by examining a factor that will influence the ingroup bias phenomenon. Integrating social identity theory with social exchange theory and unmet expectations, this paper suggests one explanation for why groups may not always feel a bias toward their fellow ingroup members. Specifically, I propose that failing to adhere to group expectations affects the bias—that would otherwise be awarded to the breacher—will be minimized or possibly even cease to exist.

When individuals’ expectations are not upheld, it influences their behavior and attitudes expressed toward those who failed to meet them. Research has shown that individuals develop expectations about how others involved in a social exchange should act and the norms they should follow Fishbein and Ajzen (1975). Fishbein and Ajzen described this phenomenon as one by which social networks develop subjective norms and values that influence how members in a social context are expected to act and react. Several streams of research build on this idea that normalization of roles are created within groups (Asch 1951), examining various aspects of the role that conformity behaviors play in groups (Ackermann and de Vreede 2011; Coultas and van Leeuwen 2015). Extending the literature on normalization and group expectations, research on unmet expectations suggests that when group norms and values are not upheld by one member in a social exchange, the other member will be less satisfied with and less committed to the violator, as well as more likely to leave the relationship (Lam et al. 2003; Major et al. 1995). Social exchange theory (SET) (Blau 1964) helps to explain this prediction by suggesting that individuals evaluate the benefits of a social relationship as compared to alternative ones. When an individual does not reciprocate the expectations held by another, or simply treats him or her negatively, the benefits of that relationship may not outweigh the costs. Expectations that emerge within interpersonal relationships depend on the context of the relationship, and the norms and values that have been developed as a guide for social exchange (Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly 2003). Group association creates an expectation that trust is shared among group members, which leads to more group collaboration (Cheng and Macaulay 2014). However, there are certainly times when members of groups do not adhere to established behavioral expectations (Priesemuth and Taylor 2016). This paper examines the role behavioral expectations in a social exchange have on social identification with members of one’s igroup and the effect that failing to adhere to the expectations of a group can have on ingroup bias and evaluations of group members.

According to social identity theory, in the context of intergroup conflict, one’s attitude toward ingroup members should remain positive relative to their attitude toward outgroup members, leading them to favor the ingroup (Jackson 2002). Conversely, one’s attitude toward outgroup members should remain negative relative to their attitude toward ingroup members (Pondy 1968). I argue in this paper however, that this relationship relies on the assumption that ingroup members meet the expectations of the group by following the group’s behavioral norms. The goal of this paper is to examine how ingroup/outgroup comparisons are influenced by unmet expectations in a social exchange. Specifically, it argues that violating a fellow ingroup member’s expectations decreases the positive evaluation they receive, and the bias they are given in comparison to the outgroup. Integrating social identity theory with literature on social exchange and unmet expectations, relationships between them are hypothesized. A laboratory experiment is used to test the proposed relationships. Results from this study enhance our understanding of group processes and provide important practical implications.

2 Theoretical Background

Social identity theory helps to explain various intra- and inter-group dynamics. According to the theory, identification with a social group is an important part of one’s self-concept, and a process that guides social behavior (Tajfel and Turner 1985). This behavior results from affective evaluations of individuals both in one’s social group and those not included in that group. Typically, this is evidenced by positive behavior directed toward members of one’s ingroup and less favorable behavior exhibited toward outgroup members. However, little research has examined behavioral factors likely to impact those evaluations. This paper argues that how members of a social group behave will impact the interpersonal evaluations of those members. Drawing from social exchange theory, the current study proposes that identification with members of a social group depends on members’ adherence to group expectations. This section begins with a review of social identity theory and focuses on how it has been found to explain intragroup behavior. Social exchange theory and literature on unmet expectations are then discussed to help develop predictions about how group member behavior will affect the attitudes of others in the group.

2.1 Social Identity Theory and Ingroup Bias

This section defines social identity theory and breaks it down by describing the purpose it serves, the biases it creates, and corresponding consequences of those biases. Research on social identity theory describes a longstanding phenomenon that has been studied in a number of different organizational settings. Social identity refers to the tendency for individuals to classify themselves into social categories as a result of perceived membership with various groups (Tajfel and Turner 1985). According to Tajfel and Turner, categorization of self and others into groups serves two purposes. First, it provides a system of enabling one to identify with or define oneself with a certain social category. This identification is important to affirming one’s self-concept, and encourages a sense of belonging. Second, it allows one to assign others into categories, which enables an individual to make attributions about outgroup members. Categorizing self and others into groups leads an individual to make comparisons between themselves and those whose membership does not coincide with their own. This social comparison leads individuals to analyze the characterizations of their ingroup against those of a comparison outgroup, resulting in a bias toward ingroup members. While the resulting benefits of receiving ingroup bias has been studied extensively, the conditions under which bias awarded to ingroup members may become eroded have not been investigated. Therefore, social identity literatures would be theoretically reinforced by examining such factors. One of the goals of the current research is to examine whether certain actions by ingroup members stress the strength of ingroup favoritism.

Membership in a social group also makes the differences of an outgroup salient; a polarization leading to partiality toward one’s ingroup (Festinger 1954). Ingroup bias results from this favoritism as preferential attitudes develop toward individuals classified as ingroup members. Tajfel (1978) described ingroup bias as being the result of an individual’s desire to evaluate themselves positively, which he suggests transfers to positive judgments of fellow ingroup members. Numerous studies have examined this phenomenon in the context of the minimal group paradigm, where it has been documented that even being randomly assigned to a group creates this ingroup favoritism (Tajfel 1970; Turner et al. 1987). These studies have shown that bias toward members of one’s ingroup does not require a priori group distinctions, but rather can develop very quickly when individuals are arbitrarily placed in distinct groups.

When social identity theory is applied to different intergroup settings, favoring one’s ingroup is not the only potential outcome. Since ingroup bias is derived from an ingroup/outgroup comparison, an opportunity for possible discrimination exists and has been found to result in negative consequences for the outgroup (Hunter et al. 2011). As described next, discrimination against the outgroup is not a necessary component of SIT, but has been found to be present in a number of different settings particularly when intergroup competition or conflict is present (Balliet et al. 2014; Mohrman et al. 1995).

Conflict research has examined the determinants of intergroup bias, focusing on the influence of conflict in amplifying favorable perceptions of ingroup members and negative perceptions of those in the outgroup (Jackson 2002). For example, Jackson found that perceived conflict moderates the relationship between group categorization and intergroup bias—measured as relative differences in evaluations of ingroup and outgroup members. Social classification and developing intergroup bias rely on comparative judgments made about group association. Though research shows that no authentic differences need be present, bias in favor of an ingroup and against an outgroup should be more dramatic when group differences are more salient (Sugiura et al. 2017). Intergroup dynamics such as interdependence and conflict provide situations where group differences become more salient. Bias for an ingroup is reflected in a number of ways and greatly influences affect and behavior toward ingroup members (Smith and Mackie 2016; Turner 1985). Some researchers believe that positive affect and liking of the ingroup in and of itself indicates negative affect and dislike of the outgroup (Tajfel and Turner 1979; Turner et al. 1987). Others however, believe that these two are independent of each other, and that positive affect toward ingroup members does not necessarily mean negative affect toward members of the outgroup (Brewer 1999). Research that argues for the latter, believes it is the presence of conflict that necessitates what Brewer (1999, p. 17) refers to as “outgroup hate.” Since the current study looks at the dynamics of ingroup bias in the context of a negotiation, it is fair to assume a bias toward members of one’s ingroup as well as a negative or at least neutral evaluation of the outgroup.

Research on SIT has identified a number of positive consequences associated with ingroup bias including knowledge sharing (Argote et al. 2000) increased trust, intragroup cohesion, cooperation, positive evaluations of (Gee and McGarty 2013; Turner 1984), support for, and increased loyalty, pride, and commitment to the ingroup (Goldman and Hogg 2016). Social identity also engenders the adoption of group values, norms, and behaviors of one’s group, creating an expectation of values and behaviors to which members adhere (Hennessy and West 1999; Turner 1984). However, implications of non-adherence to these expectations have not been empirically examined. As a result of increased cohesion and loyalty to the group, members have been found to associate with and experience both the successes and failures of the group (Brown 1986; Turner 1981). Experiencing failures and sticking with a group in times of failure describes commitment to an ingroup and leads to more preferential attitudes and stronger favorable evaluations of one’s ingroup member. This also increases a member’s partiality toward their ingroup and escalates even further the expectation that others reciprocate the group’s values (Brewer 2007). Due to the heightened expectation of reciprocity, violating that expectation should have a negative impact on the level of ingroup members’ commitment to and liking of the violator.

2.2 Social Exchange Theory and Unmet Expectations

This section begins with an explanation of how group expectations and norms are developed within social settings. Next, a brief description of the function these expectations have and why they are important is provided. Then, implications of breaching these expectations and norms are discussed. Finally, an argument is presented that integrates social identity theory with social exchange theory and unmet expectations, providing a foundation for the proposed effect it can have on ingroup bias.

Individuals all have expectations of what should and will occur in a social exchange. For example, when a door is opened for someone it is expected that the gesture be acknowledged by “thank you” from the recipient. Though that is not a foolish expectation, it is also not always the response that is received. Yet, working in groups of other people tends to guide individuals expectations to converge with the group’s (Staggs et al. 2018). Therefore, when expectations about social exchanges are not met (sometimes called psychological contract breach), it influences the attitudes and behaviors expressed toward the individual that failed to meet the expectation (Rousseau 1990).

Social exchange theory (SET) provides a conceptualization of how individuals evaluate relationships with others. It suggests that individuals calculate a cost–benefit analysis of a social exchange to determine whether a personal relationship is worth continuing (Homans 1958). When the perceived benefits of a relationship outweigh the potential costs, continued personal relationships are likely desired (Blau 1964). Conversely, if the costs of maintaining the relationship exceed the expected benefits, individuals are likely to lack motivation to continue the relationship (Blau 1964). Under this situation, individuals are likely to seek an alternative social relationship, if an alternative appears to produce higher value.

Several important potential benefits factor into the evaluation of a social exchange including affective or emotional comforts such as satisfaction and psychological well-being (Bordia et al. 2010; Coyle-Shapiro et al. 2004) as well as organizational outcomes such as general job performance and organizational citizenship behavior (Rupp and Cropanzano 2002). Conversely, negative affective feelings are associated with relationship costs (Coyle-Shapiro et al. 2004). One determinant of such affective responses is the degree to which behavioral expectations are upheld (Conway and Briner 2002).

Unmet expectations occur when there is a discrepancy between what an individual expects to encounter and how an encounter is actually experienced (Porter and Steers 1973). The degree to which unmet expectations influence outcomes of a relationship depends on the importance of the anticipated behavior (Restubog et al. 2013; Taris et al. 2006). Social identity theory helps to explain why adherence to group norms is so important. A main explanation of SIT is that social membership helps individuals develop positive self-evaluations and identities. Taris et al. (2006) found that outcomes described by social identity theory are determined to be important to an individual, and thus the expectations developed by one’s social category or group should also be strong.

Research on unmet expectations has shown that when an organization fails to meet the expectations of an employee, it influences their attitudes and emotions about the situation and subsequently has been found to be associated with a number of negative outcomes (Zhao et al. 2007). Employees whose expectations are not met respond with lower levels job satisfaction (Major et al. 1995), perceptions of fairness (Rosen et al. 2009), trust (Robinson 1996) and less identification (Ashforth and Saks 2000). Experiencing unmet expectations has also been found to predict lower levels of organizational commitment, decreased mood, increased organizational deviance and higher turnover intentions (Major et al. 1995; Restubog et al. 2013; Zhao et al. 2007). Individuals also apply expectations of a social exchange to the outcomes of interpersonal relationships, such that when one party does not fulfill the expectations of the other, the disappointed party is likely to invest much less into that relationship in the future (Taris et al. 2006; Vannier and O’Sullivan 2017) and be less concerned about distributive justice (Sondak et al. 1999). Taris and colleagues used equity theory to argue that when others break what they refer to as a psychological contract, the other is likely to perceive the relationship as inequitable, and will consequently devote less time and energy to it. Applied in selection settings, research has found that realistic job previews and adherence to them enhance trust in an organization as well as voluntary turnover (Earnest et al. 2011).

Many of the expectations individuals embrace come from norms that are developed by society (Buttle and Bok 1996). Subjective norms are created by the shared values of a group and determine what behaviors are appropriate within a social context. A commonly held norm studied in social psychology, which holds true in many settings, is that individuals are expected to reciprocate the behaviors and actions demonstrated by others (Cialdini 1984). So, when a member of a group acts in a way that is cooperative, agreeable, and trusting, it is expected that other members of the group reciprocate such actions. When a group member fails to reciprocate those behaviors, it has implications for the trust afforded to that individual (Adobor 2006; Robinson 1996). Applying unmet expectations to a group setting, I argue that failing to meet expectations will influence ingroup bias, such that it will be significantly decreased or even erased for the non-conforming member.

Kelman (1961) makes the claim that as a result of identifying with a social group, individuals desire to emulate the actions and acquire the qualities of others. This creates homogeneity of attitudes and values, as members “attempt to be like or actually to be the other person” (Kelman 1961, p 63). The expectations developed from such social identification phenomenon provide support for this paper’s first two hypotheses. Being that ingroup bias increases one’s commitment to the group, there should be an expectation for this loyalty to be reciprocated by other members of the group. Since individuals in a group are expected to cooperate, be loyal, support each other, share values, and act like others in the group, if these expectations are violated, that individual would likely not receive the same positive evaluation as those ingroup members who do uphold them. In the context of an intergroup negotiation, ingroup members that demonstrate behavior that is incongruent with group expectations will not be perceived as positively as those who meet the cooperation and loyalty expectations of ingroup members.

H1

Attitudes about ingroup members who violate group expectations will be lower than attitudes about ingroup members who adhere to those expectations.

As suggested by Brewer (1999, 2007), ingroup favoritism does not necessarily result in discrimination against the outgroup. The presence of conflict makes the ingroup/outgroup comparison more salient, leading an individual to have more positive and negative affect toward the ingroup and outgroup respectively (Balliet et al. 2014). However, since many negotiation situations may have low levels of conflict, it is fair to assume that positive ingroup evaluations will generally be stronger than negative outgroup evaluations (Yamagishi and Mifune 2009). Additionally, in a negotiation there is no expectation that the outgroup will cooperate and agree with the ingroup, but instead opposite behaviors are likely expected. This creates a situation where ingroup members should receive a positive intergroup bias, whereby they are evaluated more favorably relative to members of the outgroup. However, if an ingroup member does not reciprocate the loyalty, support, and other qualities expected of him, I predict that the intergroup bias they receive will be significantly lower than that received by ingroup members who do express such behaviors.

H2

Attitudes about ingroup members—as compared to outgroup members—will be more negative when ingroup members violate group expectations, than if they adhere to them.

Since negative attitudes toward the outgroup are not expected to be as strong as positive attitudes for the ingroup, I expect the impact of breaching group norms to be harshly detrimental to the ingroup member in relation to the outgroup comparison (Restubog et al. 2013). Additionally, because the ingroup member is expected to conform to group norms, while the outgroup member is not, it is conceivable that the previous bias for the ingroup member will actually become negative with regards to the comparison outgroup. Ingroup members are expected to cooperate and be agreeable; thus, failure to do so may result in feelings of betrayal on the part of the member being wronged (Sutton and Griffin 2004). However, non-agreement, uncooperativeness, and even misrepresentation are likely expected from the outgroup member in a negotiation (Tenbrunsel 1998). Moreover, as mentioned earlier, many negotiations have relatively low levels of conflict and thus should not create as much outgroup hate. Taken in conjunction, I propose that ingroup members who fail to meet the expectations of the group will be evaluated more negatively than members of the outgroup.

H3

Ingroup members who violate group expectations will be evaluated more negatively than members of the outgroup (Fig. 1).

3 Methods

3.1 Participants

A total of 66 undergraduate business management students from a large university participated in this study. Students enrolled in an upper-level management course were asked to participate in the intergroup negotiation experiment. Participants took part in a negotiation called the Twin Lakes Mining Company, adapted from Lewicki et al. (2003). The negotiation involved three integrative issues between town officials and a mining company. Just under half of the participants received a monetary compensation equal to half the value negotiated by their group. The remainder of participants volunteered for the study without any incentive. No significant differences were found between the two samples.

3.2 Design

Subjects were randomly assigned to either the treatment or a control group representing the mining company. Each observation group consisted of a one subject and a confederate recruited from the management department’s graduate school. This method of using a two-person group consisting of one subject provided control over the experiment, which helps to isolate the effects under investigation. In the treatment group, halfway through the negotiation, the confederate began to act counter to group expectations and to concede on issues in ways that were inconsistent with what was discussed and agreed upon by the subject and confederate in pre-negotiation discussions. In the control group, the confederate remained in agreement with the subject, sticking to the group’s strategy throughout the negotiation. After being randomly assigned to a condition, all subjects were given instructions and a payoff matrix of the negotiation items and were allowed 10 min to discuss a negotiation strategy with their group member. Participants were allowed 30 min to negotiate an agreement on each of the three issues. After the negotiation experiment, each participant completed a questionnaire to measure subjects’ evaluations of their ingroup member as well as the outgroup.

3.3 Measures

3.3.1 Ingroup Agreement

This dichotomous independent variable measured the manipulation of whether or not one’s ingroup member continued to uphold behavior expectations and to persist in the group’s agreed upon strategy. This variable was dummy-coded 1 = deviation from expectation and 0 = agreement. In order to avoid mono-method bias, this variable indicates which of the two conditions the subject was assigned. A manipulation check that asked participants to indicate whether their ingroup member adhered to the team’s negotiation plan also indicated that the treatment was successful.

3.3.2 Outgroup Evaluation

This dependent variable measures subjects’ attitude about the outgroup, so a comparison can be made between out- and ingroup evaluations. To measure outgroup evaluation, nine items from Jackson’s (2000) 7-point Likert scale of intergroup bias were used to create a variable that isolates attitudes about outgroup members (α = .86).

3.3.3 Ingroup Evaluation

To compare subjects’ attitude about ingroup members (ingroup bias) in the control group to that of the manipulation group, this dependent variable was measured with nine items from Jackson’s (2000) intergroup bias scale that were used to create a variable describing attitudes about one’s ingroup member (α = .85).

3.3.4 Intergroup Bias

Jackson’s (2000) eighteen-item measure of intergroup bias was adapted and used to measure attitude toward one’s ingroup member relative to attitude toward the outgroup. This measure calculates the difference score between two nine-item factors, representing attitudes toward ingroup members (α = .85) and outgroup members (α = .86) respectively. These items measured the participants’ evaluation of their ingroup member and the outgroup in regards to trust, cooperation, liking, honesty, intelligence, sensitivity, responsibleness, creativity and rudeness. The items were each measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

4 Results

Table 1 reports the means, standard deviations, and correlations among variables in the study. Initial analysis examined whether one’s attitude toward their ingroup member decreases when that individual did not meet the cooperation and loyalty expected of them. An analysis of variance was conducted to test the mean difference in ingroup evaluation between the manipulation and control groups.

Hypothesis 1 predicted that participant’s attitude toward members of their ingroup would be lower in the manipulation condition (violation of expectation) than in the control group. A test of participant’s ingroup evaluation, shown in Table 2, revealed a significantly lower ingroup evaluation value in the manipulation condition, than in the control group [F(1, 64) = 30.924, p < .01], providing support for hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that the difference in ingroup evaluation found above, would not just be reflected in lower levels of evaluation for both parties. Instead, a significantly lower intergroup bias score, which reflects lower ingroup bias relative to the outgroup, was predicted. Analysis of variance, displayed in Table 3, revealed a significant difference in intergroup bias scores for the two conditions [F(1, 64) = 28.432, p < .01]. Thus, strong support was found for hypothesis 2.

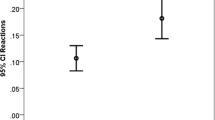

Hypothesis 3 predicted that evaluations of ingroup members who fail to uphold group expectations would be lower than evaluations of the outgroup. This hypothesis was tested by splitting the sample and analyzing just the manipulation group. A negative mean (µ = − 0.296) intergroup bias score provides initial indication of preference for the outgroup. A one-tailed t test was conducted to examine whether this negative intergroup bias is significant. Analysis revealed a significant negative intergroup bias for ingroup members who violated group expectations (t = − 1.849, p < .05). These results, which are depicted in Fig. 2, suggest that not only does one like an ingroup member who fails to carry out group expectations less than one who upholds them, but also actually favors the outgroup above them.

5 General Discussion

Positive bias awarded to ingroup members as a result of social categorization appears to be dependent on the context and whether ingroup members adhere to the behavioral expectations developed by a group. Research on SIT has found that categorizing oneself as an ingroup member helps develop one’s self-concept and identity (Gardner and Garr-Schultz 2017), and leads to preferential treatment for others perceived to share characteristics of a group. The presence of an outgroup also facilitates a preferential judgment of the ingroup, and sometimes a dislike for members of the outgroup (Jackson 2002). The present study extends our understanding of SIT, providing a situation under which the bias established in existing literature is challenged. Specifically, the expression of favoritism that is understood to exist among ingroup members is significantly diminished when an ingroup member fails to adhere to the behavioral norms adopted by that group.

These results contribute to social identity theory research, by suggesting that adherence to the norms and expectations of a group may be necessary in order to benefit from ingroup bias. Data from this negotiation experiment show that when expectations in a social exchange are breached, the ingroup bias phenomenon does not endure. The literature on SIT has focused primarily on discovering the reasons why ingroups form (Thomas et al. 2016), explaining why group membership influences individual favoritism (Iacoviello and Spears 2018), the benefits awarded to ingroup members (Whitham 2017), and even processes involved in overcoming pitfalls of favoritism (Saygı et al. 2015; Wagner et al. 2017). While the literature on SIT has a longstanding prominence in social psychology, our understanding of the conditions under which common SIT findings do not persist is lacking. The results of the current study aid our understanding by pointing toward one mechanism that removes ingroup favoritism. Non-adherence to group expectations simultaneously decreased ingroup bias and even reversed the relative attitudes for ingroup and outgroup members. That conclusion also contributes to literature on social exchange theory and unmet expectations, demonstrating outcomes of non-conformity to group expectations and social norms. Behavioral expectations and norms significantly affect organizational and group behavior, and can help individuals to adapt to organizational goals in a way that attributes to performance (Shah and Jehn 1993). This paper links social exchange literatures and social identity theory by proposing and testing the relationship between norm adherence and ingroup bias. According to the current results, when ingroup members fail to uphold expectations developed by the group, the individual who violates them will be evaluated as low as or even more negatively than the outgroup.

5.1 Practical Implications

These findings are also very practical for managers. Because trends in the utilization of teams to carry out tasks continue to grow, so to should our understanding of group dynamics. A primary responsibility for managers is to ensure that their work groups are effectively realizing the benefits for which they were formed. The results from this study submit that team supervisors pay close attention to the social norms that form within a team and the enactment of those behavioral expectations. Specifically, managers should make sure norms and expectations developed by work groups are acknowledged and upheld by all employees.

A central advantage of creating a team is that its members tend to develop favorable evaluations of each other, which tends to produce positive results. Identification with ingroup members is positively related to trust that develops within a group (McKnight et al. 1998) and also directly impacts group creativity (Paulus and Yang 2000) and performance (van Knippenberg et al. 2004). The importance of trust in a functional team is practically and empirically significant (Colquitt et al. 2007). Because groups depend on members to share information with each other, work cooperatively, represent one another, and be willing to help others in need, the maintenance of trust within a group is compulsory. In addition to preserving those functions, trust has also been found to significantly impact group performance (Dirks and Ferrin 2001). This experiment provides evidence that breaking from behavioral expectations greatly diminishes ingroup bias and therefore identification. The impact that would have on intragroup trust could weaken the bonds that develop in work teams and have detrimental effects on group functioning and performance.

In addition to helping to develop trust and strong group performance, bias resulting from ingroup membership positively impacts employee motivation (Baumeister and Leary 1995) and citizenship behavior (Van Der Vegt and Bunderson 2005). Many employees are motivated by a need for affiliated relationships with co-workers. Groups who share cooperative relationships set the stage for member learning and increased time spent on a task, as well as performance and motivation (Klein and Pridemore 1992). Those benefits were amplified for individuals who score higher on need for affiliation. However, even with workers with lower need for affiliation, the social support provided by cooperative ingroup membership has been found to increase organizational identification (Wiesenfeld et al. 2001). In order to avoid decreases in employee motivation and identification, organizational leaders should try to encourage cooperation and social support, which should include supporting social norms.

It should also be noted that these expectations fall outside the obligatory behaviors outlined by group member roles. Since employees are usually aware of the required conducts of their position, non-adherence is understood to result in penalty, and is therefore voluntary. However, social norms are less easily specified and detailed, providing increased opportunity for involuntarily breaching expectations (Krupka et al. 2016). And while those nonconforming behaviors may not be accompanied by regulatory penalty, results from this study suggest that it will in fact be penalized. This suggests that managers pay close attention to the social norms that develop within workgroups, and that they share these sometimes ambiguous expectations with all members of the group. This is especially true for new employees who have not helped shape expected norms; managers should make no assumptions that they will simply learn the nuances of group expectations while on the job. Another complication of this recommendation is that managers are not always aware of the social norms of the teams they oversee. Newly appointed managers, or managers who do not continuously interact with group members are not likely to know or understand the behavioral expectations groups form. If this results from lack of time, then a new manager would benefit by attempting to learn such norms. If however it results because of direct contact with a group or because group members choose not to share these expectations, manager responses are less straightforward. However, since non-adherence to group norms is so vital to group performance it is recommended that new managers and employees get involved with an experienced employee or mentor so social expectations can be disseminated to all group members. As organizational units are increasingly using virtual teams and other technologies that impact group interactions, we can be sure that behavioral norms related to those technologies are also evolving. While the nuances of the potential affect of technology on unmet expectations was not tested in the current study, there is evidence that norms develop specifically about technologies, and that technology use changes some other organizational norms not directly related to the technologies (Haines et al. 2014). Thus, managers and group leaders should pay special attention to how technology norms develop and how they are shared among group members.

In any case, it is usually best to proactively deal with things that may lead to group dysfunction. Thus, in order to benefit from the potential efficiencies of using teams, managers should reinforce behaviors that are both congruent and/or incongruent with group expectations. Specifically, by recognizing or rewarding behavior that is consistent with group norms, a manager can increase the likelihood of that behavior continuing; and by punishing or reprimanding behavior that is inconsistent with group norms, that behavior is more likely to be discontinued. Additionally, in order to encourage cohesiveness, all members should be transparent about group norms and advocate that all adhere to them.

5.2 Limitations

The above study is not without limitations. It is necessary to note that the use of an undergraduate sample should be considered when generalizing results to work teams within organizations. However, numerous studies have used undergraduate samples to examine phenomena and consequences regarding social identity theory (Bartunek et al. 1975; Eggins et al. 2002; Hogg and Hains 1998), supporting this sample as dependable.

While the control offered by the study’s design has its benefits, it also creates a drawback needing mentioned. A shorter period experiment, such as that used here, relies on a minimal group paradigm, and thus results in effects of a fairly loose ingroup. By merely working on a common task, subjects likely form bonds that are weaker than those of many coworker teams that develop over a longer duration. The strength of those bonds and the accompanying trust may not decline as quickly as subjects taking part in an experiment. Thus, it would be interesting to see how the behavioral expectations and social norms of long-standing ingroups are impacted by non-adherence to those norms. That said, these results are still very applicable for young groups, groups with new members, as well as the increasing number of groups comprised of temporary workers. Additionally, research has found that ingroup favoritism results even when groups are especially “minimal” (Turner 1975).

Another limitation of the study is that demographic variables such as gender and culture were not used as controls. Since the main objective of the study was to test whether the universal phenomenon of ingroup bias is contingent upon acting in accordance with norms, the possible affect of demographic characteristics was not examined. However, future research should examine whether the findings here would vary depending on different demographic combinations.

6 Conclusion

The goal here was to examine how individual behavior in an intergroup negotiation influences the phenomenon of social identity and ingroup bias. Specifically, the focus of this study was to investigate the importance of remaining loyal and acting in accordance with group expectations as well as to examine a consequence for violating group norms. This study demonstrates that failure to uphold group expectations erodes the bias normally awarded to ingroup members. Social identity theory describes one’s tendency to show favoritism to those categorized as being in one’s ingroup. This paper concludes that this favoritism does not persist when fellow ingroup members do not adhere to norms developed by the group. Results suggest that the positive bias traditionally awarded to members of an ingroup, diminishes when group expectations are violated. When individuals who are expected to remain cooperative and loyal, display contrary actions, they receive lower evaluations than those who uphold them. Interestingly, those who fail to uphold group expectations receive no preferential treatment above members of the outgroup, who are expected to be uncooperative and disloyal. This contradiction to the commonly supported ingroup bias, suggests that there are situations in which the phenomenon is reversed.

References

Abid HR, Gulzar A, Hussain W (2015) The impact of servant leadership on organizational citizenship behaviors with the mediating role of trust and moderating role of group cohesiveness; a study of public sector of Pakistan. Int J Acad Res Bus Soc Sci 5(3):234

Ackermann F, de Vreede GJ (2011) Special issue on ‘dvances in designing group decision and negotiation processes. Group Decis Negot 20(3):271

Adobor H (2006) The role of personal relationships in inter-firm alliances: benefits, dysfunctions, and some suggestions. Bus Horiz 49(6):473–486

Argote L, Ingram P, Levine JM, Moreland RL (2000) Knowledge transfer in organizations: learning from the experience of others. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 82:1–8

Asch SE (1951) Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In: Guetzkow H (ed) Groups, leadership, and men. Sage, San Francisco, pp 222-236

Ashforth BE, Saks AM (2000) Personal control in organizations: a longitudinal investigation with newcomers. Hum Relat 53(3):311–339

Balliet D, Wu J, De Dreu CK (2014) Ingroup favoritism in cooperation: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull 140(6):1556

Bartunek JM, Benton AA, Keys CB (1975) Third party intervention and the bargaining behavior of group representatives. J Conflict Resolut 19(3):532–557

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1995) The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 117(3):497–529

Blau PM (1964) Exchange and power in social life. Wiley, New York

Bordia S, Hobman EV, Restubog SLD, Bordia P (2010) Advisor-student relationship in business education project collaborations: a psychological contract perspective. J Appl Soc Psychol 40(9):2360–2386

Brewer MB (1999) The psychology of prejudice: ingroup love or outgroup hate? J Soc Issues 55(3):429–444

Brewer MB (2007) The importance of being we: human nature and intergroup relations. Am Psychol 62(8):728–738

Brown RW (1986) Social psychology, 2nd edn. Free Press, New York

Buttle F, Bok B (1996) Hotel marketing strategy and the theory of reasoned action. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 8(3):5–10

Cheng X, Macaulay L (2014) Exploring individual trust factors in computer mediated group collaboration: a case study approach. Group Decis Negot 23(3):533–560

Cialdini RB (1984) Influence: the psychology of persuasion. Quill, New York

Colquitt JA, Scott BA, LePine JA (2007) Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: a meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. J Appl Psychol 92(4):909

Conway N, Briner RB (2002) A daily diary study of affective response to psychological contract breach and exceeded promises. J Organ Behav 23(3):287–302

Coultas JC, van Leeuwen EJ (2015) Conformity: definitions, types, and evolutionary grounding. In: Zeigler-Hill V, Welling L, Shackelford T (eds) Evolutionary perspectives on social psychology. Springer, Cham, pp 189–202

Coyle-Shapiro JAM, Shore LM, Taylor MS, Tetrick LE (2004) The employment relationship: examining psychological and contextual perspectives. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Dirks KT, Ferrin DL (2001) The role of trust in organizational settings. Organ Sci 12(4):450–467

Earnest DR, Allen DG, Landis RS (2011) Mechanisms linking realistic job previews with turnover: a meta-analytic path analysis. Pers Psychol 64(4):865–897

Eggins RA, Haslam SA, Reynolds KJ (2002) Social identity and negotiation: subgroup representation and superordinate consensus. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 28(7):887–889

Festinger L (1954) A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat 7(2):117–140

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley, Reading

Gardner WL, Garr-Schultz A (2017) Understanding our groups, understanding ourselves: the importance of collective identity clarity and collective coherence to the self. In: Lodi-Smith J, DeMarree K (eds) Self-concept clarity. Springer, Cham, pp 125–143

Gee A, McGarty C (2013) Aspirations for a cooperative community and support for mental health advocacy: a shared orientation through opinion-based group membership. J Appl Soc Psychol 43(S2):426–441

Goldman L, Hogg MA (2016) Going to extremes for one’s group: the role of prototypicality and group acceptance. J Appl Soc Psychol 46(9):544–553

Haines R, Hough J, Cao L, Haines D (2014) Anonymity in computer-mediated communication: more contrarian ideas with less influence. Group Decis Negot 23(4):765–786

Hennessy J, West MA (1999) Intergroup behavior in organizations: a field test of social identity theory. Small Group Res 30(3):361–382

Hoegl M, Weinkauf K, Gemuenden HG (2004) Interteam coordination, project commitment, and teamwork in multiteam R&D projects: a longitudinal study. Organ Sci 15(1):38–55

Hogg MA (2001) A social identity theory of leadership. Personal Soc Psychol Rev 5(3):184–200

Hogg MA, Hains SC (1998) Friendship and group identification: a new look at the role of cohesiveness in groupthink. Eur J Soc Psychol 28(3):323–341

Homans GC (1958) Social behavior as exchange. Am J Sociol 63(6):597–606

Hunter JA, Banks M, O’Brien K, Kafka S, Hayhurst G, Jephson D, Jorgensen B, Stringer M (2011) Intergroup discrimination involving negative outcomes and self-esteem. J Appl Soc Psychol 41(5):1145–1174

Iacoviello V, Spears R (2018) “I know you expect me to favor my ingroup”: reviving Tajfel’s original hypothesis on the generic norm explanation of ingroup favoritism. J Exp Soc Psychol 76:88–99

Jackson JW (2000) How variations in social structure affect different types of intergroup bias and different dimensions of social identity in a multi-intergroup setting. Group Process Intergroup Relat 2(2):145–173

Jackson JW (2002) Intergroup attitudes as a function of different dimensions of group identification and perceived intergroup conflict. Self Identity 1(1):11-33

Johnson JL, O’Leary-Kelly AM (2003) The effects of psychological contract breach and organizational cynicism: not all social exchange violations are created equal. J Organ Behav 24(5):627–647

Kelman HC (1961) Processes of opinion change. Public Opin Q 25(1):57–78

Klein JD, Pridemore DR (1992) Effects of cooperative learning and need for affiliation on performance, time on task, and satisfaction. Educ Technol Res Dev 40(4):39–48

Krupka EL, Leider S, Jiang M (2016) A meeting of the minds: informal agreements and social norms. Manag Sci 63(6):1708–1729

Lam T, Pine R, Baum T (2003) Subjective norms: effects on job satisfaction. Ann Tour Res 30(1):160–177

Lewicki R, Saunders DM, Minton JW, Barry B (2003) Negotiation: readings, exercises, and cases. Irwin/McGraw-Hill, Boston

Major D, Kozlowski S, Chao G, Gardner P (1995) A longitudinal investigation of newcomer expectations, early socialization outcomes, and the moderating effects of role development factors. J Appl Psychol 80(3):419–431

Mathieu JE, Kukenberger MR, D’innocenzo L, Reilly G (2015) Modeling reciprocal team cohesion–performance relationships, as impacted by shared leadership and members’ competence. J Appl Psychol 100(3):713

McKnight DH, Cummings LL, Chervany NL (1998) Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships. Acad Manag Rev 23(3):473–490

Mohrman SA, Cohen SG, Mohrman AM (1995) Designing team-based organizations: new forms for knowledge work. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Navarro-Carrillo G, Valor-Segura I, Moya M (2018) Do you trust strangers, close acquaintances, and members of your ingroup? Differences in trust based on social class in Spain. Soc Indic Res 135(2):585–597

Paulus PB, Yang H-C (2000) Idea generation in groups: a basis for creativity in organizations. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 82(1):76–87

Pondy LR (1968) Organisational conflict: concepts and models. Adm Sci Q 12:296–320

Porter L, Steers R (1973) Organizational, work and personal factors in employee turnover and absenteeism. Psychol Bull 80(2):151–176

Priesemuth M, Taylor RM (2016) The more I want, the less I have left to give: the moderating role of psychological entitlement on the relationship between psychological contract violation, depressive mood states, and citizenship behavior. J Organ Behav 37(7):967–982

Restubog SLD, Zagenczyk TJ, Bordia P, Tang RL (2013) When employees behave badly: the roles of contract importance and workplace familism in predicting negative reactions to psychological contract breach. J Appl Soc Psychol 43(3):673–686

Robinson SL (1996) Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Adm Sci Q 41:574–599

Rosen CC, Chang C-H, Johnson RE, Levy PE (2009) Perceptions of the organizational context and psychological contract breach: assessing competing perspectives. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 108(2):202–217

Rousseau D (1990) Assessing organizational culture: the case for multiple methods. In: Stirred B (ed) Organizational climate and culture. Sage, San Francisco, pp 97–107

Rupp DE, Cropanzano R (2002) The mediating effects of social exchange relationships in predicting workplace outcomes from multifoci organizational justice. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 89(1):925–946

Saygı Ö, Greer LL, Van Kleef GA, De Dreu CK (2015) Bounded benefits of representative cooperativeness in intergroup negotiations. Group Decis Negot 24(6):993–1014

Shah PP, Jehn KA (1993) Do friends perform better than acquaintances? The interaction of friendship, conflict, and task. Group Decis Negot 2(2):149–165

Simpson B (2006) Social identity and cooperation in social dilemmas. Ration Soc 18(4):443–470

Smith ER, Mackie DM (2016) Group-level emotions. Curr Opin Psychol 11:15–19

Sondak H, Neale MA, Pinkley RL (1999) Relationship, contribution, and resource constraints: determinants of distributive justice in individual preferences and negotiated agreements. Group Decis Negot 8(6):489–510

Staggs SM, Bonito JA, Ervin JN (2018) Measuring and evaluating convergence processes across a series of group discussions. Group Decis Negot. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-018-9560-3

Sugiura H, Mifune N, Tsuboi S, Yokota K (2017) Gender differences in intergroup conflict: the effect of outgroup threat priming on social dominance orientation. Personal Individ Differ 104:262–265

Sutton G, Griffin MA (2004) Integrating expectations, experience, and psychological contract violations: a longitudinal study of new professionals. J Occup Organ Psychol 77(4):493–514

Tajfel H (1970) Aspects of national and ethnic loyalty. Soc Sci Inf 9(3):119–144

Tajfel H (1978) The achievement of group differentiation. In: Tajfel H (ed) Differentiation between social groups: studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations. Academic Press, London, pp 77–98

Tajfel H, Turner JC (1979) An integrative theory of intergroup conflict relations. In: Austin WG, Worchel S (eds) The social psychology of intergroup relations. Brooks/Cole, Monterey, pp 33–47

Tajfel H, Turner JC (1985) The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG (eds) Psychology of intergroup relations, 2nd edn. Nelson-Hall, Chicago, pp 7–24

Taris TW, Feij JA, Capel S (2006) Great expectations—and what comes of it: the effects of unmet expectations on work motivation and outcomes among newcomers. Int J Sel Assess 14(3):256–268

Tenbrunsel AE (1998) Misrepresentation and expectations of misrepresentation in an ethical dilemma: the role of incentives and temptation. Acad Manag J 41(3):330–339

Thomas EF, McGarty C, Mavor K (2016) Group interactions as the crucible of social identity formation: a glimpse at the foundations of social identities for collective action. Group Process Intergroup Relat 19(2):137-151

Turner JC (1975) Social comparison and social identity: some prospects for intergroup behaviour. Eur J Soc Psychol 5(1):1–34

Turner JC (1981) The experimental social psychology of intergroup behavior. In: Turner JC, Giles H (eds) Intergroup behavior. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 66–101

Turner JC (1984) Social identification and psychological group formation. In: Tajifel H (ed) The social dimension: European developments in social psychology, vol 2. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 518–538

Turner JC (1985) Social categorization and self-concept: a social cognitive theory of group behavior. In: Lawler EJ (ed) Advances in group processes, vol 2. JAI Press, Greenwich, pp 77–122

Turner JC, Hogg MA, Oakes PJ, Reicher SD, Wetherell MS (1987) Rediscovering the social group: a self-categorization theory. Basil Blackwell

Van Der Vegt GS, Bunderson JS (2005) Learning and performance in multidisciplinary teams: the importance of collective team identification. Acad Manag J 48(3):532–547

van Knippenberg D, De Dreu CKW, Homan AC (2004) Work group diversity and group performance: an integrative model and research agenda. J Appl Psychol 89(6):1008–1022

Vannier SA, O’Sullivan LF (2017) Great expectations: examining unmet romantic expectations and dating relationship outcomes using an investment model framework. J Soc Pers Relatsh 34(2):235-257

Wagner JP, Grigg N, Mann R, Mohammad M (2017) High task interdependence: job rotation and other approaches for overcoming ingroup favoritism. J Manuf Technol Manag 28(4):485–505

Whitham MM (2017) Paying it forward and getting it back: the benefits of shared social identity in generalized exchange. Sociol Perspect 61(1):81–98

Wiesenfeld BM, Raghuram S, Garud R (2001) Organizational identification among virtual workers: the role of need for affiliation and perceived work-based social support. J Manag 27(2):213–229

Yamagishi T, Mifune N (2009) Social exchange and solidarity: ingroup love or outgroup hate? Evolut Hum Behav 30(4):229–237

Zhao H, Wayne SJ, Glibkowski BC, Bravo J (2007) The impact of psychological contract breach on work-related outcomes: a meta-analysis. Pers Psychol 60(3):647–680

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dunne, T.C. Friend or Foe? A Reversal of Ingroup Bias. Group Decis Negot 27, 593–610 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-018-9576-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-018-9576-8