Abstract

Three experimental studies show that interpersonal relationships influence the expectations of negotiators at the negotiation table. That is, negotiators expect more generous negotiation offers from close others (Study 1), and when expectations are not met, negative emotions arise, resulting in negative economic and relational outcomes (Study 2). Finally, a boundary condition for the effect of interpersonal relationships on negotiation expectations is shown: perspective taking leads the parties to expect less from friends than from acquaintances (Study 3). The findings suggest that perspective taking helps negotiators reach agreement in relationships. The article concludes with implications for practice and future research directions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Business partnerships are often based on a combination of work and personal relationships. The technology firms Google, YouTube, and Yahoo all have been founded by members with close personal relationships. Close relationships facilitate the creation of successful firms and are essential for management practices (Ferris et al. 2009). However, empirical studies have shown that close relationships are not always favorable for economic transactions, such as negotiation (for a review, see McGinn 2006). The story of Bill Gates and Paul Allen, his partner at Microsoft, is a perfect example of a friendship that evolved into one of the most successful international business partnerships but did not have a happy ending. In the mid-1970s, Allen expected to receive an equal split of the company after the pair landed their first important contract (Wilgfiled and Guth 2011). However, Gates offered only 40% of the partnership. Several years later, Allen was again disappointed when his friend and colleague Bill rejected his petition to increase his Microsoft shares after Allen’s work on a successful product called SoftCard. The relationship between Paul and Bill was never the same.

Although intuition suggests that personal relationships should have a positive influence on business, the negotiation literature finds the opposite effect. That is, most studies indicate that the presence of close relationships at the negotiation table does not directly improve negotiation outcomes (Greenhalgh and Chapman 1998; Thompson and DeHarpport 1998). Friends tend to negotiate worse deals than strangers (Greenhalgh and Chapman 1998), empathy exerts negative effects on negotiation outcomes (Galinsky et al. 2008), and negotiators in close relationships are more willing to settle for suboptimal agreements than in relationships with strangers (Curhan et al. 2008; Fry et al. 1983). In the aforementioned example, Allen had high expectations of the benefits he would receive in negotiation, while Gates refused to concede to these expectations. The expectancy violation resulted in Allen’s disappointment and, in turn, damaged the business relationship.

Expectations play a major role in negotiation perceptions and outcomes. For example, expected future interactions lead parties to lower their aspirations, while expecting the other party to be friendlier and use problem-solving strategies (Patton and Balakrishnan 2010). Expectations of a competitive opponent generate higher aspirations and a distributive strategy (Tinsley et al. 2002), and negotiators who focus on expectations obtain higher outcomes but are less satisfied than negotiators who focus on their reservation prices (Galinsky et al. 2002). Therefore, a primary factor behind unsuccessful business negotiation is the expectations of the parties in the relationship. Moreover, emotions can play an important role when offers fail to meet these expectations. That is, disappointment with closer others at the negotiation table can damage the business relationship. What situations facilitate economic exchange between parties in a relationship? This study addresses one of the boundary conditions for the effect of close relationships on expectations—namely, perspective taking.

Negotiating in close relationships generates two distinct motives that compete from the moment parties prepare for the negotiation: on the one hand, negotiators want to maintain the relationship, while on the other hand, they want to reach a good outcome for themselves (Kurtzberg and Medvec 1999). Therefore, in this study we focus on expectations of the other party’s behavior at the negotiation table before the interaction. We argue that expectations, emotions, and perspective taking influence the effect of close relationships before the negotiation. Prior research fails to propose boundary conditions that lead to favorable relationships for the parties. We argue that expectations are reversed in close relationships when one party takes the perspective of the other party.

2 Relationships at the Negotiation Table

Human nature is intensely social and shaped by relationships. Humans need to be embedded in healthy relationships and share bonds with family members, romantic partners, friends, and fellow group members (Baumeister and Leary 1995). The concept of a “relationship” represents two people whose behavior is interdependent (Kelley et al. 1983).

The negotiation field has largely focused on economic outcomes (Bazerman et al. 2000a, b; Bazerman and Neale 1992), and only a few studies have focused on examining the benefits of future interaction (Ben-Yoav and Pruitt 1984; Heide and Miner 1992; Mannix 1994; Pruitt and Carnevale 1993; Sinaceur et al. 2015). Moreover, an emergent body of research has focused on the importance of social psychological outcomes, such as relational capital among negotiating parties (Curhan et al. 2006; Gelfand et al. 2006). Relational capital is similar to the construct of social capital, which refers to the accumulation of goodwill among a social network of relational ties (Adler and Kwon 2002; Granovetter 1985). Relational capital typically entails mutual liking, trust, and high quality of a dyadic relationship as opposed to a network of relationships with many individuals (Clercq and Sapienza 2006; Gelfand et al. 2006).

While close relationships perform better at decision-making and motor tasks (Shah and Jehn 1993), reduce costs and bring additional benefits to negotiation where trust is critical such as risky transactions (DiMaggio and Louch 1998), most studies suggest that the presence of close relationships has a negative effect on negotiation outcomes. A study of dating couples, for example, shows that they are more willing to settle for suboptimal negotiation agreements than strangers (Fry et al. 1983). That study shows that couples’ concerns about the future of the relationship reduced bargaining aspirations, which in turn reduced their use of bargaining tactics that enable detection of better joint outcomes. The expectation of future reciprocity leads negotiators to be more willing to make concessions (Mannix et al. 1995). In a U.S. context, Greenhalgh and Chapman (1998) observe that contracts are often given to friends, even in the face of better economic returns from giving the contract to a stranger with a better bid. Olekalns and Smith (2007) proposed that negotiators attempt to create a scenario where trades are fair and opportunistic exploitation is discouraged in order to maintain a positive relationship. The need to belong, a personality characteristic, made negotiators more stressed and more willing to sacrifice value in integrative negotiations (O’Connor and Arnold 2011).

Relational contexts are situations in which individuals hold a cognitive representation of themselves as being fundamentally interdependent or interconnected with other individuals, a construct psychologists refer to as “relational self-construal” (Cross and Madson 1997; Kashima et al. 1995). Highly relational contexts can lead to a phenomenon called “relational accommodation,” in which negotiators sacrifice joint economic outcomes, in deference to the pursuit of relational goals and/or the adherence to relational norms (Curhan et al. 2008).

Individuals with an orientation involving high concern with relationships coupled with low self-concern are more willing to give up value and make more concessions in integrative and distributive negotiation, due to a greater concern for relationships that results in a low reservation price (the minimum they are willing to accept in their negotiations) and lower value claiming (Amanatullah et al. 2008). Behavioral evidence from ultimatum bargaining games also suggests that perceptions of social closeness facilitate generosity, such that more generous offers are extended to others perceived as close (Jones and Rachlin 2006).

The literature on close relationships in negotiation suggests that the parties are willing to sacrifice value. They focus on the other party, rather than on themselves, however, it is not clear from the literature whether negotiators in close relationships expect the other party to sacrifice value as well. The effects of relationships have been analyzed prior to the negotiation. Researchers have examined personality factors (e.g. need to belong), and have shown the direct effects of relationships on the outcomes (Greenhalgh and Greenhalgh 1993). Therefore, we do not know how negotiators process the relational information before the interaction. For that reason, we focus on the moment before the negotiation when individuals construct the situation and create expectations. Consistent with the relational accommodation effect, we predict that in close relationships negotiators will expect their counterparts to have less extreme aspirations than in distant relationships. We posit that in close relationships, parties are concerned about the relationship and, as the literature indicates, will be more willing to sacrifice value themselves. Thus, we focus on the expectations of the other party’s behavior by exploring whether the primary negotiator anticipates the sacrificed value of the other party.

The rationale is that in close relationships, people not only are more likely to provide value to close others (Clark and Mills 1979, 1993) but also want their partners to care about their needs. An important part of maintaining relationships is showing that the parties are motivated to care for each other, and in return, they want their partners to similarly support and care for them (Lemay et al. 2007). Halpern (1994, 1996, 1997), for example, interpreted the effect of relationships on participants’ generosity in economic transactions and found that buyers offer more to friends than to strangers and sellers request less from friends than from strangers. We predict that these same buyers and sellers may expect the same level of generosity from their closer ones in return.

We therefore predict that negotiators will expect their close counterparts to be willing to sacrifice value by having less extreme aspirations.

Hypothesis 1

Negotiators will expect more favorable offers for themselves the closer the relationship with the counterpart.

An alternative explanation for the parties’ expectations is social motivation. Social motivation is an individual difference about the preferred distribution between one’s own and others’ outcomes (Messick and McClintock 1968). A meta-analysis indicates that negotiators with a prosocial motive are less contentious, use more problem solving strategies and reach higher outcomes compared to egoistically motivated negotiators (De Dreu et al. 2000). As participants vary in the extent to which they prefer asymmetric or egalitarian outcomes we measured this variable to rule out this alternative explanation for our expectation measure.

Study 1

2.1 Participants and Design

Data came from 137 undergraduate psychology students at a major university in Spain. The experiment was part of a classroom exercise. The sample consisted of 84 (62%) women and 52 (38%) men, with an average age of 22.67 years (SD = 5.60). All participants received course credit for taking part in the study.

2.2 Procedure

For this study, we used a scenario-based design. Participants arrived at the lab in groups of 25–35 people and were asked to sign the attendance list to avoid their participation in future studies. Next, participants were randomly assigned to different computers. All instructions were shown on the computer screen. Participants were informed that all information provided would be anonymous and treated as confidential.

First, participants were asked to write the names of three types of people in their lives (their best friend, a friend, and an acquaintance) and to assign one closeness rating to each relationship. Then, participants were presented a total of nine scenarios and were asked to choose among three options representing combinations of outcomes for themselves and an (anonymous) other.

Next, they were told that they would complete an exercise in which they would play the role of a person negotiating the purchase of a used car. All participants received the role of the buyer of a used car. Participants were also informed they had identified a similar car whose selling price was €2500 (Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement—BATNA). In the best friend condition, for example, participants read the following:

We would like you to read the following scenario and play the role of a person negotiating the purchase of a used car. You need a car and you are interested in buying. You already have an alternative car that you like and could buy for 2500 EUR.

Next, before introducing the manipulation, we asked participants the maximum price they would pay for the car. Later, participants were informed they would be randomly assigned to negotiate with one of these relationships (best friend, friend, or acquaintance). In the best friend condition, participants read the following:

While you are walking home you run into {{name of best friend}}, who is trying to sell a used car. The used car {{name of best friend}} is selling is indeed the same type of used car you are trying to buy.

2.2.1 Independent Variables

Social value orientation was measured before the negotiation and used it as a post hoc independent variable. We introduced the nine-item social value orientation scale (Van Lange et al. 1997) before presenting the negotiation scenario. Participants chose among three options representing combinations of outcomes for themselves and an (anonymous) other in a series of decomposed games. Outcomes were represented by points, and we instructed the participants to imagine that the points were valuable for both parties. An example of these nine items is the choice among Option A (520 points for the self and 520 points for another party) Option B (520 point for the self and 120 points for the other party), and Option C (580 points for the self and 320 points for the other party). Each option represents a particular orientation. In this example, pro-socials, competitors, and individualists would select Option A, B, and C, respectively. Participants who did not have a minimum of six of one type of response were considered unclassifiable participants and therefore were not counted in the analyses. As a result, a total of 26 participants were considered unclassifiable participants.

Second, the type of relationship was manipulated. Participants read a scenario in which they run into the randomly assigned counterpart (best friend, friend or acquaintance). The scenario reported that this person was also trying to sell his or her used car and that the used car was exactly the same model and year as the car the participant was interested in buying. It is important to take note that this is a between subject design where none of the participants negotiated with the assigned person. Indeed, participants were just asked to answer a set of different questions.

2.2.2 Dependent measures

First, to assess closeness, before introducing the manipulation, we asked participants to rate how close they perceived the three of their relationships to be, on a seven-point scale, anchored by 1 (the most distant) and 7 (the closest). They assigned one closeness rating to each relationship. Second, to assess the price limit, before introducing the manipulation, we asked participants the maximum price they would pay for the car. We used limits as a control variable in all our analyses. Finally, to measure expected price, we asked participants what the expected asking price for the car would be depending on their relationship with the car owner. Depending on the condition, the owner could be the best friend, friend, or acquaintance.

2.3 Results

2.3.1 Manipulation Checks

To verify participants’ understanding of the task, we developed several questions addressing the closeness with their best friend, friend, or acquaintance. We then asked them to identify who made the offer. In total, 112 participants were able to identify the relationship randomly assigned to the negotiation. A total of 22 participants were excluded from the analysis because they failed to identify the manipulation. The remaining 3 excluded participants did not answer all of the questions presented.

2.3.2 Closeness by Relationship

We tested how close participants perceived their counterpart. The results of a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed that participants perceived their best friends closer (\(M = 6.58\), \(\hbox {SD} = .60\)) than their friends (\(M = 5.44\), \(\hbox {SD} = 1.30\)) and acquaintances (\(M = 3.50\), \(\hbox {SD} = 1.54\)), \(F(2, 111) = 62.864\), \(p < .001\), \(\upeta ^{2} = .536\)). Planned comparisons showed significant differences between best friends and friends (\(p < .001\)), best friends and acquaintances (\(p < .001\)), and friends and acquaintances (\(p < .001\)).

2.3.3 Effects of Types of Relationships on Expectations

We tested whether participants expected to receive more favorable offers from their closer relationships. Our first analysis confirmed Hypothesis 1. A one-way ANOVA showed that negotiators expected to receive more favorable offers from closer friends. Participants expected to receive lower selling prices from best friends (\(M = 2060.53\), \(\hbox {SD} = 589.91\)) and friends (\(M = 2141.67\), \(\hbox {SD} = 476.52\)) than from acquaintances (\(M = 2557.57\), \(\hbox {SD} = 671.78\)), \(F(2, 111) = 9.245, p < .001, \upeta ^{2} = .146\)).

Planned comparisons showed significant differences between best friends and acquaintances (p = .001) and friends and acquaintances (\(p < .01\)). We found no significant differences between the best friend and friend conditions. We checked for effects of gender on expected price and found that these were not significant (\(p = .437\)). Figure 1 illustrates the effects.

2.3.4 Relationships, Social Value Orientation, and Expectations

There is extensive literature on social motivation and the impact of pro-social motives on parties’ tendencies to cooperate as well as the effects of pro-social motives on parties’ expectations. To test the influence of social motivation on expectations, as mentioned previously, we showed the participants the nine-item social value orientation scale (Van Lange et al. 1997) before presenting the negotiation scenario. According to our results, social value orientation did not predict expectations in Study 1, and social value orientation was not a moderator between relationships and expectations. Thus, the interaction between relationships and social value orientation did not predict expectations.

In Study 1, not only did participants perceive their best friends and friends as closer than their acquaintances, but they also expected more generous offers from them. Our first study suggests that close relationships are positively related to expectations, therefore the closer the relationship, the more likely it is that the expectations cannot be met.

Our next studies focus on two aspects: expectancy violation and its consequences, and a boundary condition for the effect of relationships on expectations. Specifically, our next study explores the negative emotions that arise when expectations are not met and the influence of these emotions on the evaluation and acceptance of negotiation offers. Since no significant differences between the best friends and friends conditions were found in this first study, in coming studies we focus on the differences between best friends and acquaintances.

3 Experienced Emotions

Emotions are a central part in relationship development and evaluation (Reis and Collins 2004). Emotions in relationships may arise from comparing one’s own expectations with the other party’s offer; therefore, we focus on the experienced emotion as a result of expectancy violation. Moreover, we argue that emotions can damage perceptions of the relationship when expectations are not met. The emotion-in-relationships model predicts that people hold strong expectancies of the partner that, when violated, generate the experience of negative emotion because interdependencies usually carry implications for the individual’s welfare (Berscheid and Ammazzalorso 2001). Specifically, close relationships lead parties to expect more from one another, setting the parties up for negative emotional responses if these expectations are not met (Barry and Oliver 1996). Negative emotions such as anger and disappointment are automatic default responses to disconfirmed expectancies (Frijda 1986; Mandler 1975). Unexpected negative events caused by external circumstances lead not only to disappointment but also to anger when another person is responsible for the disappointing situation (Zeelenberg and Pieters 1999; Zeelenberg et al. 2000). Negotiation literature suggests that negotiators express anger to generate concessions from others (Allred 1999; Barry 1999; Van Kleef et al. 2004). Specifically, anger directed at the offer and disappointment directed at the person, result in effective value claiming (Lelieveld et al. 2011). Sadness can also increase the negotiator’s ability to claim value (Sinaceur et al. 2015).

Violation of interpersonal expectations results in emotional reactions (Burgoon 1993), specifically anger (Lewis et al. 1990). Experienced emotions will also influence the evaluation of the offers and the decision to accept them or not. Evidence from ultimatum games suggests that anger increases the likelihood of an offer being rejected compared with sadness (Forgas and Tan 2013; Srivastava et al. 2009). The violation of expectations may lead to unfairness perceptions and rejection of offers that are objectively better than alternatives (Bazerman et al. 2000a, b; Pillutla and Murnighan 1996).

Hypothesis 2

Expectancy violation in negotiation will generate negative emotions, which in turn will negatively influence the evaluation of negotiation offers.

Hypothesis 3

Negative emotions and evaluation of negotiation offers will mediate the relationship between expectancy violation and offer acceptance.

Study 2

We designed Study 2 to better understand the effects of expectancy violation in negotiation. Considering that our previous results did not show significant differences between the best friend and friend conditions, we did not include the friend condition in this study but rather focused on best friends and acquaintances.

3.1 Participants and Design

Data came from 84 undergraduate psychology students at a major university in Spain. The experiment was part of a classroom exercise. The sample consisted of 13 (16%) women and 71 (84%) men, with an average age of 24.78 years (SD = 4.16). All participants received course credit for taking part in the study.

3.2 Procedure

For Study 2, we used the same procedure as in Study 1. In the pre-negotiation phase participants were asked to write the names of two types of people in their lives: their best friend, and an acquaintance. Then, participants were told that they would engage in a negotiation in which they would play the role of a person negotiating the purchase of a used car. All participants received the role of the buyer of a used car. Participants were also informed they had identified a similar car whose selling price was €2500 (BATNA). For example, in the acquaintance condition, participants read the following:

We would like you to read the following scenario and play the role of a person negotiating the purchase of a used car. You need a car and you are interested in buying. You already have an alternative car that you like and could buy for 2500 EUR.

Before introducing the manipulation, we asked participants the maximum price they would pay for the car. Next, participants received information that they would negotiate with either a best friend or an acquaintance depending on the condition. In the acquaintance condition, participants read the following:

While you are walking home you run into {{name of acquaintance}}, who is trying to sell a used car. The used car {{name of acquaintance}} is selling is indeed the same type of used car you are trying to buy.

Then, participants were asked what the expected asking price for the car would. After giving us their expectations, participants randomly received offers of €1000, €2000, or €3000. Finally, negative emotions, offer evaluation and acceptance of offers were measured.

3.2.1 Independent Variables

First, type of relationship was manipulated. Participants read a scenario in which they run into one of the following people (depending on the experimental condition): (1) their best friend or (2) an acquaintance. The scenario indicated that this person was trying to sell his or her used car and that the used car was exactly the same model and year as the car the participant was interested in buying.

Second, we computed expectancy violation post hoc by comparing the expectations and the offer participants received. Participants randomly received offers of €1000, €2000, or €3000. We operationalized expectancy violation as the distance between expectations and offers. We computed it as the value of the expectation minus the offer, such that positive values of expectancy violation represent expectations satisfied by a lower selling offer and negative values represent expectations violated by a higher selling offer.

3.2.2 Dependent Measures

To assess the price limit, before introducing the relationship manipulation, we asked participants how much they were willing to pay for the car. We used limits as a control variable in all our analyses. To measure expected price, we asked participants what price they expected to receive from the owner.

To measure negative emotions, we asked participants how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the following statements (seven-point scale): (1) “The asking price made me feel angry,” (2) “The asking price made me feel sad,” and (3) “I was disappointed with the asking price” (\(\upalpha = .90\)). Regarding the evaluation of the offer, we asked how good or bad the offer (also asking price) they received from the owner of the car was. The participants indicated whether they strongly agreed or disagreed with the following statements (seven-point scale): (1) “The asking price seems appropriate to me,” (2) “The asking price seems suitable to me,” and (3) “The asking price seems right to me” (\(\upalpha = .96\)). Finally, to measure acceptance of offers, participants were asked whether or not they would accept the assigned offer: (1) “Yes, I would accept this offer” and (2) “No, I would not accept this offer”.

3.3 Results

3.3.1 Manipulation Checks

To verify the participants’ understanding of the task, we asked them to identify who made the offer. In total, 80 participants were able to identify the relationship randomly assigned to the negotiation. Therefore, we excluded from the analysis four participants because they failed to identify the manipulation.

3.3.2 Effects of Types of Relationships on Expectations

We tested whether participants expected to receive more favorable offers from their close relationships. A one-way ANOVA showed that participants expected to receive lower selling prices from their best friends (\(M = 1822.73, \hbox {SD }= 557.35\)) than from acquaintances (\(M = 2116.67, \hbox { SD } = 777.82\)), \(F(2,80) = 5.51\), \(p = .022\), \(\upeta ^{2} = .067\). These results provide support for Hypothesis 1. We checked for effects of gender on expected price and found that these were not significant (\(p= .144\)). Figure 2 illustrates the effects.

3.3.3 Expectancy Violations, Negative Emotions, and Evaluation of Negotiation Offers

Hypothesis 2 predicted that emotions would mediate the relationship between expectancy violation and evaluation of negotiation offers. To test this hypothesis, we used the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013), model 4 (bootstrapping method, 5000 samples). Mediation tests in Study 2 show a significant direct effect of expectancy violation on the evaluation of the offers (\(\upbeta = 1.070\), t(80) = 6.52, \(p <.001, 95\% \,\hbox {CI}\,\,[.743, 1.396]\)) and an indirect effect of expectancy violation on the evaluation of the offers mediated by negative emotions (\(\upbeta =.359, 95\% \,\hbox {CI}\,\,[.119, .670]\)). Thus, Hypothesis 2 is confirmed. Expectancy violations negatively influence the evaluation of negotiation offers. Figure 3 illustrates the effects.

3.3.4 Acceptance of the Offers

Hypothesis 3 predicted that negative emotions and the evaluation of the offers would mediate the effect between expectancy violation and the acceptance of the offers. To test this hypothesis, we used the PROCESS macro (Hayes 2013), model 6 (bootstrapping method, 5000 samples). Sequential mediation tests showed a significant indirect effect of expectancy violations on the acceptance of the offers mediated by negative emotions and the evaluation of the offers (\(\upbeta =.286, 95\% \,\hbox {CI}\,\,[.036, .815]\)). No direct effects were found. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is confirmed. Figure 4 illustrates the effects.

In sum, when close relationships were present at the table, we expected close relationships to have higher expectations of the counterpart’s behavior. High expectations result in expectancy violations, which in turn negatively influence the evaluation and acceptance of the negotiation offers. In Study 3, we identify a boundary condition for this general effect of increased expectations in close relationships.

4 Perspective Taking

Perspective taking may help reduce expectations by making the other party’s contributions more salient. Perspective taking is the cognitive capacity to consider the world from the viewpoint of others (Davis 1983). Taking the perspective of others is a key component of successful conflict resolution (Paese and Yonker 2001) because it increases the probability of helping parties in need (Batson 1994). In negotiations, perspective taking helps the parties overcome cognitive biases, such as anchoring (Galinsky and Mussweiler 2001) or the fixed-pie perception (Galinsky et al. 2008; Moran and Ritov 2007; Thompson 1995). Considering the other party’s contributions helps negotiators process information that he or she would otherwise naturally disregard, thus reducing the self-serving allocation of resources (Savitsky et al. 2005). Specifically, taking the other party’s perspective is particularly important for people in close relationships, as they have a history of exchanges with that particular person. Since people in close relationships are likely to contribute more than acquaintances to a particular relationship, taking the other’s perspective in close relationships might make the other parties contributions to the relationship salient and reduce the negotiator’s expectations. Meanwhile, taking an acquaintance perspective might make the other contributions to the relationship salient increasing the negotiator’s expectations.

Drolet et al. (1998) examine the role of perspective taking in negotiation in relationships and suggest that perspective taking leads the parties to make more generous offers in positive relationships and more competitive offers in negative relationships. However, their participants were neither asked to consider the other party’s contributions nor were they asked to focus on the expectations of the other party’s behavior. Previous studies (Ross and Sicoly 1979) suggested that individuals may overestimate their own contributions simply because they are likely to be aware of, notice and remember their own actions and efforts more than those of other contributors. Moreover, the accessibility of one’s own efforts is partially responsible for exaggerated claims of contributions (Epley et al. 2006).

If perspective taking helps the parties reduce their own aspirations, consistent with these findings we argue that considering the other party’s contributions will also moderate the expectations. Moreover, we suggest that the effects of perspective taking will vary across relationships. For example, perspective taking between strangers increases egoism and the resources allocated to oneself (Epley et al. 2006). We predict, however, that when negotiating among close friends, recalling the contributions of these friends to the relationship (perspective taking) will decrease expectations. Our rationale is that taking the perspective of a more distant relationship will generate reactive egoism, consistent with the study of Epley et al. (2006) . However, taking the perspective of a close friend will result in generosity, as his or her contributions to the relationships are greater. Therefore, we argue that when negotiating in close relationships, taking our friend’s perspective and expressly considering his or her contributions will lead to generosity. That is, thinking about the other party and valuing the rewards of the relationship will decrease expectations from others who are close. More specifically, participants would expect less favorable offers when taking their friend’s perspective. Therefore, participants taking the perspective of their friends will expect to pay more for the car they want to buy.

Hypothesis 4a

In negotiation, taking the other party’s perspective will decrease expectations from partners in close relationships.

Meanwhile, based on the previous assumptions, we argue that when negotiating in close relationships, considering our own contributions will lead to selfishness. That is, thinking about myself and valuing my contributions to the relationship will increase expectations from others who are close. Then, participants would expect more favorable offers from the closer ones when taking the self’s perspective. As a result, participants taking the self’s perspective will expect to pay less for the car they want to buy.

Hypothesis 4b

In negotiation, taking the self’s perspective will increase expectations from partners in close relationships.

Our general prediction is that negotiation in close relationships results in higher expectations of the counterpart’s behavior. Negotiators expect more favorable offers from closer relationships. The paradox is that good offers may be negatively evaluated from close relationships when they do not satisfy expectations, consequently resulting in negative emotions. Our proposition is that one of the factors causing suboptimal agreements when negotiating in close relationships is the expectations of the counterpart’s behavior. We test perspective taking as a boundary condition that can help manage negotiations in relationships by reducing the expectations of close others.

Study 3

We designed this study to measure how participants’ perspectives may influence expectations at the negotiation table. As Studies 1 and 2 showed, participants had higher expectations of their close friends, expecting to receive better selling offers from them. This new study manipulates perspective taking to potentially reverse the effect of the expectations.

4.1 Participants and Design

Data came from students enrolled in an introductory psychology class. All 115 participants were undergraduate students working toward a Degree in Labor Relations and Human Resources at a major university in Spain. The sample consisted of 75 (65%) women and 40 (35%) men, with an average age of 24.58 years (\(\hbox {SD} = 12.81\)). All participants received course credit for taking part in the study. Study 3 was a scenario-based study with a 2 (relationships: best friend and acquaintance) \(\times \) 3 (perspective: other’s perspective, self-perspective, and control) factorial design. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the six possible conditions.

4.2 Procedure

For this study, we used a similar procedure to the one used in Studies 1 and 2. Again, participants were asked to write the names of two types of people in their lives: their best friend, and an acquaintance in the pre-negotiation phase. Next, participants were randomly assigned to one of the six conditions and perspective taking was manipulated. For example, in the best friend-other’s perspective condition participants read the following:

Please, describe all the things {{name of best friend}} has done for you in the past.

Next, participants were told that they would engage in a negotiation in which they would play the role of a person negotiating the purchase of a used car. All participants received the role of the buyer of a used car. Participants were also informed they had identified a similar car whose selling price was €2500 (BATNA). Participants read the following:

We would like you to read the following scenario and play the role of a person negotiating the purchase of a used car. You need a car and you are interested in buying. You already have an alternative car that you like and could buy for 2500 EUR.

Next, before relationship was manipulated, we asked participants the maximum price they would pay for the car. Later, depending on the condition, participants received information that they would negotiate with either a best friend or an acquaintance. In the best friend condition, for example, participants read the following:

While you are walking home you run into {{name of best friend}}, who is trying to sell a used car. The used car {{name of best friend}} is selling is indeed the same type of used car you are trying to buy.

Lastly, participants were asked the expected selling price for the car.

4.2.1 Independent Variables

First, to manipulate perspective taking, the participants were asked to recall and describe a situation depending on the condition. With the main goal of making participants value the rewards of the relationship, one story version asked them to describe all the things the other party (either their best friend or their acquaintance) had done for them; we did this to induce a focus on the other’s perspective. The next version asked participants to describe all the things they had done for the other party (either their best friend or their acquaintance), with the aim of making them value the cost of the relationship; we did this to induce a focus on the self-perspective. The last version asked them to give their opinions about the metro construction in the city as a control condition.

Second, to manipulate type of relationship, consistent with the previous studies, participants read a negotiation scenario in which they run into either (1) their best friend or (2) an acquaintance, depending on the experimental condition.

Third, to evaluate offers, participants received a prompt that informed them that they had decided to ask the assigned person the sales price for the used car. In Study 3, all participants received the same offer (€2000).

4.2.2 Dependent Variables

We asked participants what the expected price for the car would be depending on their relationship with the car owner. Depending on the condition, the owner was either the best friend or an acquaintance.

4.3 Results

4.3.1 Manipulation Checks

With the main goal to verify the participants’ understanding of the task, we asked them to identify who made the offer. In total, 97 participants were able to identify the relationship randomly assigned to the negotiation. Therefore, we excluded from the analysis 18 participants because they failed to identify the manipulation.

Next, we asked participants to identify the scenario described before the negotiation, with the main goal of verifying participants’ understanding of the perspective. Participants were able to select the scenario in which they had to describe all the things the other party had done for them (other’s perspective focus), the scenario in which they had to describe all the things they had done for the other party (self-perspective focus), or the scenario in which they had to give their opinion about the metro construction in the city (control condition). Seven participants failed to identify the scenario and were excluded from the analysis.

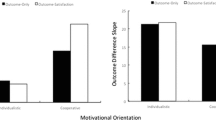

4.3.2 Effects of Types of Relationships and Perspective Taking on Expectations

We tested whether perspective taking had an influence on the negotiators’ expectations across different relationships. For this purpose, we performed a two-way interaction analysis with perspective taking as the independent variable and expectations as the dependent variable, moderated by types of relationships. We performed a moderation analysis with a multi-categorical independent variable (here, perspective taking) with three levels, following Hayes and Preacher’s (2014) recommendations. Because we expected negotiators to think about their contributions to the relationship by default, we built two contrast codes, one comparing the other’s perspective with the self-perspective and the control condition (d1) and one comparing the self-perspective with the control condition (d2). We were especially interested in the results from the d1 contrast code. Moderation analysis on expectations revealed a significant two-way interaction between perspective taking and type of relationship (\(\upbeta = 376.92, t(89) = 2.25, p < .05,95\% \,\hbox {CI}\,\, [43.784, 710.056]\)). Thus, Hypotheses 4a and 4b were confirmed. Consistent with Study 1 and Study 2, in the self-perspective and control conditions, participants had higher expectations in close relationships, expecting to receive more favorable offers (lower selling prices) from their best friends (\(M = 2073.56\), \(\hbox {SD} = 637.45\)) than from acquaintances (\(M = 2431.57\), \(\hbox {SD} = 724.60\)). However, this effect was reversed in the other’s perspective condition, in which participants had lower expectations in close relationships, expecting to receive less favorable offers (higher selling prices) from their best friends (\(M = 2546.03\), \(\hbox {SD} = 912.40\)) than from acquaintances (\(M = 2150.19\), \(\hbox {SD} = 713.68\)). Figure 5 illustrates the effects.

5 Discussion and Conclusions

Across three studies, we explored the effects of types of relationships on negotiators’ behaviors. Our studies provide empirical support for the effect of relationships on expectations. People want their partners to care about their needs in closer relationships, expecting more generous offers from them. Moreover, our studies show that when expectations are violated, the emotions influence the evaluation of negotiation offers. Finally, we analyzed the mechanism for the effects of types of relationships on negotiators’ behavior and found that when negotiators focus on the other party (rather than themselves), their expectations are reversed—they expect less from their best friends than from acquaintances.

Our studies provide insights into effects of types of relationships at the negotiation table, and it is among the first studies to provide a causal mechanism for these effects. We present emotions and perspective taking as the main processes behind these effects in negotiation. Our contribution to theory is twofold. First, we extend the theoretical predictions of perceived partner responsiveness (Lemay et al. 2007) to the study of relationships in negotiation. Second, we suggest that the perspective-taking framework (Davis 1983) is a key mechanism for explaining how negotiators moderate their expectations and how they can reverse the negative effects of types of relationships at the negotiation table. Finally, we contribute to the few studies showing that relationships can have a positive effect in negotiation. For example, Curhan et al. (2010) showed that across repeated interactions subjective value in one negotiation can increase objective value in a subsequent negotiation. Similarly, Eggins et al. (2002) showed that when people interact with other ingroup members or within a group they benefit from this interaction in a subsequent negotiation. This effect is mediated by the development of a superordinate identity. Our study, on the other hand, shows that negotiating within closer relationships can be beneficial if the other party takes perspective.

In addition, this research has practical implications for the impact of the type of relationship on negotiation and for the impact of perspective taking on the rejection of close relationships’ offers in particular. We found consistent results, showing that when close relationships are present at the negotiation table, negotiators have higher expectations about their counterpart’s behavior. We also show that high expectations result in expectancy violation, which in turn negatively influences the evaluation of the negotiation offers, leading to the rejection of offers that were better than the alternatives. Our data shows that one of the factors that cause suboptimal agreements when negotiating in close relationships is the comparison between expectations and offers. For example, in our second study, offers of €1000 (60% cheaper than buyers’ BATNA) confirmed expectations in all of the cases, offers of €3000 (20% more expensive than buyers’ BATNA) violated expectations in most cases. Meanwhile, offers of €2000 (20% cheaper than buyers’ BATNA) generated more expectation violations in close relationships.

Perspective taking can help reduce expectations when negotiating with closer relationships, however it may also increase expectations when negotiating with acquaintances. Our results show that when participants take perspective from the other party, they expected their best friends to make less favorable (higher) offers. Meanwhile, when participants take perspective from their acquaintances, they expected them to make more favorable (lower) offers. Therefore, when negotiators take the perspective of the other party in a close relationship, this reduces the high expectations from his or her side, and the evaluation of suboptimal offers documented here might be minimized or eliminated. According to Epley et al. (2006), this effect would occur, only when taking the perspective of friends. As these authors note, the key mechanisms underlying the consequences of perspective taking are the thoughts negotiators consider when they put themselves in the place of the other person.

Future studies could address for example the effects of perspective taking on relationships and specifically on why expectations seem to increase when participants take the perspective of the other party in the acquaintance condition. Other possible research avenues are testing the effects of types of relationships on integrative and distributive strategy at the negotiation table, or exploring the conditions that facilitate emotional regulation when negotiating in relationships. Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of our studies. A first limitation pertains to common method variance, as all studies were scenario based, cross-sectional and not longitudinal. The small sample of some of our studies and the high number of participants rejected after failing to pass the manipulation checks may constitute a second limitation. Thus, further research should use a larger sample with a higher participation to further validate and extend our results. We also acknowledge that our studies are experimental with restricted ecological validity based on student samples. A higher participation of the general population will be recommended in future studies. As a way forward, future studies could also replicate these studies with a working population sample. One more limitation is that none of our students included items to identify the financial stability of participants. Our data does not indicate how big of a burden the €2500 BATNA would be for participant and, therefore, the maximum price to pay for the car could be significantly different from case to case. Future studies could either include items to identify the financial stability of participants or focus primarily on offset percentages rather than absolute values. Finally, these studies focus on the expectations at the negotiation table without addressing face-to-face strategies. The implementation of longitudinal studies could also provide evidence of the reciprocity dynamics occurring in negotiations within relationships.

References

Adler PS, Kwon S (2002) Social capital: prospects for a new concept. Acad Manag Rev 27(1):17–40

Allred KG (1999) Anger and retaliation: toward an understanding of impassioned conflict in organizations. Res Negot Organ 7:27–58

Amanatullah ET, Morris MW, Curhan JR (2008) Negotiators who give too much: unmitigated communion, relational anxieties, and economic costs in distributive and integrative bargaining. J Pers Soc Psychol 95(3):723–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012612

Barry B (1999) The tactical use of emotion in negotiation. Res Negot Organ 7:93–121

Barry B, Oliver RL (1996) Affect in dyadic negotiation: a model and propositions. Organ Behav Hum Decis 67(2):127–143. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1996.0069

Batson CD (1994) Prosocial motivation: Why do we help others? In: Tesser A (ed) Advanced social psychology. McGraw-Hill, Boston, pp 333–381

Baumeister RF, Leary MR (1995) The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol Bull 117(3):497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

Bazerman MH, Neale MA (1992) Negotiating rationally. Free Press, New York

Bazerman MH, Curhan JR, Moore DA (2000a) The death and rebirth of the social psychology of negotiation. Interpersonal processes. In: Fletcher GJO, Clark MS (eds) Blackwell handbook of social psychology. Blackwell, Cambridge, pp 196–228

Bazerman MH, Curhan JR, Moore DA, Valley KL (2000b) Negotiation. Annu Rev Psychol 51:279–314

Ben-Yoav O, Pruitt DG (1984) Resistance to yielding and the expectation of cooperative future interaction in negotiation. J Exp Soc Psychol 20(4):323–335

Berscheid E, Ammazzalorso H (2001) Emotional experience in close relationships. In: Fletcher GJO, Clark MS (eds) Blackwell handbook of social psychology: interpersonal processes. Blackwell, Malden, pp 308–330

Burgoon JK (1993) Interpersonal expectations, expectancy violations, and emotional communication. J Lang Soc Psychol 12(1–2):30–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X93121003

Clark MS, Mills J (1979) Interpersonal attraction in exchange and communal relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol 37:12–24. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.37.1.12

Clark MS, Mills J (1993) The difference between communal and exchange relationships: what it is and is not. Pers Soc Psychol B 19(6):684–694. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167293196003

Cross SE, Madson L (1997) Models of the self: self-construals and gender. Psychol Bull 122(1):5–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.122.1.5

Curhan JR, Elfenbein HA, Xu H (2006) What do people value when they negotiate? Mapping the domain of subjective value in negotiation. J Pers Soc Psychol 91(3):493–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.493

Curhan JR, Neale MA, Ross L, Rosencranz-Engelmann J (2008) Relational accommodation in negotiation: effects of egalitarianism and gender on economic efficiency and relational capital. Organ Behav Hum Decis 107(2):192–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.02.009

Curhan JR, Elfenbein HA, Eisenkraft N (2010) The objective value of subjective value: a multi-round negotiation study. J Appl Psychol 40(3):690–709

Davis MH (1983) Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 44(1):113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

De Clercq D, Sapienza HJ (2006) Effects of relational capital and commitment on venture capitalists’ perception of portfolio company performance. J Bus Ventur 21:326–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.04.007

De Dreu CKW, Weingart LR, Kwon S (2000) Influences of social motives in integrative negotiations: a meta-analytic review and test of two theories. J Pers Soc Psychol 78(5):889–905

DiMaggio P, Louch H (1998) Socially embedded consumer transactions: for what kinds of purchases do people most often use networks? Am Sociol Rev 63(5):619–637

Drolet A, Larrick R, Morris MW (1998) Thinking of others: how perspective taking changes negotiators’ aspirations and fairness perceptions as a function of negotiator relationships. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 20(1):22–31. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324834basp2001_3

Eggins RA, Haslam SA, Reynolds KJ (2002) Social identity and negotiation: subgroup representation and superordinate consensus. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 28(7):887–899

Epley N, Caruso E, Bazerman MH (2006) When perspective taking increases taking: reactive egoism in social interaction. J Pers Soc Psychol 91(5):872–889. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.5.872

Ferris GR, Liden RC, Munyon TP, Summers JK, Basik KJ, Buckley MR (2009) Relationships at work: toward a multidimensional conceptualization of dyadic work relationships. J Manag 35(6):1379–1403. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309344741

Forgas JP, Tan HB (2013) Mood effects on selfishness versus fairness: affective influences on social decisions in the ultimatum game. Soc Cognit 31(4):504–517. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco_2012_1006

Frijda N (1986) The emotions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Fry WR, Firestone IJ, Williams DL (1983) Negotiating process and outcome of stranger dyads and dating couples. Do lovers lose? Basic Appl Soc Psychol 4(1):1–16

Galinsky AD, Mussweiler T (2001) First offers as anchors: the role of perspective-taking and negotiator focus. J Pers Soc Psychol 81(4):657–669. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.4.657

Galinsky AD, Mussweiler T, Medvec VH (2002) Disconnecting outcomes and evaluations: the role of negotiator focus. J Pers Soc Psychol 83(5):1131–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1131

Galinsky AD, Maddux WW, Gilin D, White JB (2008) Why it pays to get inside the head of your opponent: the differential effects of perspective-taking and empathy in negotiations. Psychol Sci 19(4):378–384. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02096.x

Gelfand MJ, Major VS, Raver JL, Nishi LH, O’Brien K (2006) Negotiating relationally: the dynamics of the relational self in negotiations. Acad Manag Rev 31(2):427–451. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.20208689

Granovetter MS (1985) Economic action and social structure. Am J Sociol 91(3):481–510. https://doi.org/10.1086/228311

Greenhalgh L, Chapman DI (1993) The influence of relationships on the process and outcomes of negotiations. Cornell University, Ithaca

Greenhalgh L, Chapman DI (1998) Negotiator relationships: construct measurement and demonstration of their impact on the process and outcomes of negotiation. Group Decis Negot 7(6):465–489. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008694307035

Halpern JJ (1994) The effect of friendship on personal business transactions. J Confl Resolut 38:647–64

Halpern JJ (1996) The effect of friendship on decisions: field studies of real estate transactions. Hum Relat 49(12):1519–1547

Halpern JJ (1997) Elements of a script for friendship in transactions. J Confl Resolut 41:835–68

Hayes AF (2013) An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Guilford Press, New York

Hayes AF, Preacher KJ (2014) Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. Brit J Math Stat Psychol 67(3):451–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12028

Heide JB, Miner AS (1992) The shadow of the future: effects of anticipated interaction and frequency of contact on buyer–seller cooperation. Acad Manag J 35(2):265–291

Jones B, Rachlin H (2006) Social discounting. Psychol Sci 17(4):283–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01699.x

Kashima Y, Yamaguchi S, Kim U, Choi SC, Gelfand M, Yuki M (1995) Culture, gender, and self: a perspective from individualism–collectivism research. J Pers Soc Psychol 69(5):925–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.925

Kelley HH, Berscheid E, Christensen A, Harvey JH, Huston TL, Levinger G, McClintock E, Peplau LA, Peterson DR (1983) Analyzing close relationships. In: Kelley HH, Berscheid E, Christensen A, Harvey JH, Huston TL, Levinger G, McClintock E, Peplau LA, Peterson DR (eds) Close relationships. Freeman, New York, pp 20–67

Kurtzberg T, Medvec VH (1999) Can we negotiate and still be friends? Negot J 15(4):355–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1571-9979.1999.tb00733.x

Lelieveld GJ, Van Dijk E, Van Beest I, Steinel W, Van Kleef GA (2011) Disappointed in you, angry about your offer: distinct negative emotions induce concessions via different mechanisms. J Exp Soc Psychol 47:635–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.12.015

Lemay EP Jr, Clark MS, Feeney BC (2007) Projection of responsiveness to needs and the construction of satisfying communal relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol 92(5):834–853. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.5.834

Lewis M, Alessandri SM, Sullivan MW (1990) Violation of expectancy, loss of control, and anger expressions in young infants. Dev Psychol 26(5):745–751. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.26.5.745

Mandler G (1975) Mind and emotion. Wiley, New York

Mannix EA (1994) Will we meet again? Effects of power, distribution norms, and scope of future interaction in small group negotiation. Int J Confl Manag 5(4):343–368

Mannix EA, Tinsley CH, Bazerman M (1995) Negotiating over time: impediments to integrative solutions. Organ Behav Hum Decis 62:241–251

McGinn KL (2006) Relationships and negotiations in context. In: Thompson L (ed) Frontiers of social psychology: negotiation theory and research. Psychological Press, New York

Messick DM, McClintock CG (1968) Motivational bases of choice in experimental games. J Exp Soc Psychol 4(1):1–25

Moran S, Ritov I (2007) Experience in integrative negotiations: What needs to be learned? J Exp Soc Psychol 43(1):77–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2006.01.003

O’Connor KM, Arnold JA (2011) Sabotaging the deal: the way relational concerns undermine negotiations. J Exp Soc Psychol 47(6):1167–1172

Olekalns M, Smith PL (2007) Loose with the truth: predicting deception in negotiation. J Bus Ethics 76(2):225–238

Paese PW, Yonker RD (2001) Toward a better understanding of egocentric fairness judgments in negotiation. Int J Confl Manag 12(2):114–131. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022852

Patton C, Balakrishnan PV (2010) The impact of expectation of future negotiation interaction on bargaining processes and outcomes. J Bus Res 63(8):809–816. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.07.002

Pillutla MM, Murnighan JK (1996) Unfairness, anger, and spite: emotional rejections of ultimatum offers. Organ Behav Hum Decis 68(3):208–224. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1996.0100

Pruitt DG, Carnevale PJ (1993) Negotiation in social conflict. Brooks/Cole, Pacific Grove

Reis HT, Collins WA (2004) Relationships, human behavior, and psychological science. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 13(6):233–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00315.x

Ross M, Sicoly F (1979) Egocentric biases in availability and attribution. J Pers Soc Psychol 37(3):322

Savitsky K, Van Boven L, Epley N, Wight W (2005) The unpacking effect in responsibility allocations for group tasks. J Exp Soc Psychol 41:447–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2004.08.008

Shah P, Jehn KA (1993) Do friends perform better than acquaintances? The interaction of friendship, conflict, and task. Group Decis Negot 2(2):149–165. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01884769

Sinaceur M, Kopelman S, Vasiljevic D, Haag C (2015) Weep and get more: when and why sadness expression is effective in negotiations. J Appl Psychol 100(6):1847–1871

Srivastava J, Espinoza F, Fedorikhin A (2009) Coupling and decoupling of unfairness and anger in ultimatum bargaining. J Behav Decis Mak 22(5):475–489. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.631

Thompson L (1995) The impact of minimums goals and aspirations on judgments of success in negotiations. Group Decis Negot 4(6):531–524. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01409713

Thompson L, DeHarpport T (1998) Relationships, goal incompatibility, and communal orientation in negotiations. Basic Appl Soc Psychol 20(1):33–44

Tinsley CH, O’Connor KM, Sullivan BA (2002) Tough guys finish last: the perils of a distributive reputation. Organ Behav Hum Decis 88(2):621–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-5978(02)00005-5

Van Kleef GA, De Dreu CKW, Manstead AS (2004) The interpersonal effects of anger and happiness in negotiations. J Pers Soc Psychol 86(1):57–76

Van Lange PAM, Agnew CR, Harinck F, Steemers GEM (1997) From game theory to real life: how social value orientation affects willingness to sacrifice in ongoing close relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol 73(6):1330–1344. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1330

Wilgfiled N, Guth R (2011) Microsoft co-founder hits out at gates. Wall Str J. http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052748703806304576232051635476200. Accessed 30 Mar 2011

Zeelenberg M, Pieters R (1999) On serviced delivery that might have been: behavioral responses to disappointment and regret. J Serv Res 2(1):86–97

Zeelenberg M, van Dijk WW, Manstead ASR, van der Pligt J (2000) On bad decisions and disconfirmed expectancies: the psychology of regret and disappointment. Cognit Emot 14(4):521–541. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300402781

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This investigation was partially funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science (PSI 2011/29256) and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (PSI2015-64894-P).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ramirez-Fernandez, J., Ramirez-Marin, J.Y. & Munduate, L. I Expected More from You: The Influence of Close Relationships and Perspective Taking on Negotiation Offers. Group Decis Negot 27, 85–105 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-017-9548-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10726-017-9548-4