Abstract

Iron supplementation during pregnancy is crucial for the health of the mother and the child. This study investigates the prevalence and determinants of zero consumption of Iron and Folic Acid (IFA) tablets among pregnant women in India. We use the National Family Health Survey (NFHS 2019–21) survey data to study the spatial patterns and further apply multilevel multivariate logistic regression to identify factors associated with zero IFA tablet consumption. We find that 15.7% women (15–49 years) did not consume any IFA tablet during her last pregnancy. The spatial analysis showed clusters of zero IFA consumption, with hotspot districts in northern, central, eastern, and north-eastern states of India. The factors significantly associated with zero consumption of IFA during pregnancy includes unintended pregnancies (OR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.16, 1.28), not receiving nutritional supplementation from ICDS (OR = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.44, 1.55), no visits for ANC (OR = 2.97, 95% CI: 2.84, 3.11), no counselling on health and nutrition (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.29, 1.39). Women with no media exposure, those from lower wealth quintiles and those belonging to the Other Backward Class (OBC), of the Muslim faith, and with lower education levels were also more likely to have zero IFA consumption. The analysis pinpoints areas where immediate intervention can enhance the uptake of IFA (Iron and Folic Acid) tablets during pregnancy. In conclusion, we suggest a need to focus on raising awareness through platforms such as antenatal care and family planning counselling, ICDS (Integrated Child Development Services), and community-wide actions on socio-cultural factors to improve IFA tablet consumption among pregnant women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Enhanced nutritional support and supplementation during pregnancy is necessary to ensure improved health outcomes of the mother and her newborn. During pregnancy, the iron stored in the body substantially deplete because of increased red blood cell volume and iron transfer to the fetus. Maternal blood loss and lochia discharge during childbirth further reduced the iron content (Bothwell, 2000). Iron deficiency during pregnancy is associated with adverse outcomes, such as maternal illness, low birth weight, prematurity, and intrauterine growth restriction (Dewey & Oaks, 2017; Georgieff, 2020). Addressing these adverse birth outcomes is a global imperative, as underscored by the Every Newborn Action plan initiated jointly by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations (WHO, 2019). WHO currently recommends daily oral iron and folic acid supplementation (IFAS) comprising 30–60 mg of elemental iron and 400 mg of folic acid during pregnancy to prevent maternal anemia, preterm birth, and infants being born small for their gestational age (WHO, 2016).

Globally, anemia prevalence among pregnant women is estimated at 38%, reaching 48% in South Asia (Stevens et al., 2022). Approximately 50% of pregnancy-related anemia cases are deemed responsive to iron supplementation (WHO, 2016). In India, anemia affected 56% of pregnant women aged 15–49 years in 2021 (IIPS & ICIF, 2019–21). Consequently, Indian pregnant women are advised to take 60 mg of iron supplementation daily from the second trimester or minimum at least 180 days during pregnancy, (MoHFW, Government of India, 2018), whicb is also aligning with WHO guidelines (WHO, 2016). This recommendation is consistent with the guidance from the World Health Organization on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience, which suggests that all pregnant women, regardless of their hemoglobin levels, should receive iron supplementation (WHO, 2016).

Previous studies conducted in India have established that the presence of anemia during delivery elevates the risk of stillbirth, neonatal mortality, and low birth weight infants (Ahankari et al., 2017; Hidayat et al., 2016; Kumari et al., 2019). Additionally, maternal anemia has been associated with 13.2% and 14.9% of maternal deaths and obstetric complications, respectively (Gevariya et al., 2015; Puri et al., 2011; Yadav et al., 2013). In 1972, India initiated the National Nutritional Anemia Prophylaxis Program (NNAPP) to combat anemia among its target population (Vijayaraghavan et al., 1990). Over the years, India has introduced several significant initiatives, including the National Nutritional Anemia Control Programme (NNACP) in 1991, the National Iron Plus Initiative (NIPI) in 2013, and the the Anemia Mukt Bharat (AMB) strategy in 2018. The AMB initiative is integral to the Prime Minister's Overarching Scheme for Holistic Nutrition in India (POSHAN) Abhiyaan (Ahmad et al., 2023). The coverage of iron folic acid supplementation among pregnant Indian women aged 15–49 years has improved over three decades, increasing from 50.5% in 1992–93 to 87.6% in 2021. However, only 44.1% of women consume IFA tablet for 100 days or more and 26% for 180 days in 2021 (IIPS & ICF, 2021).

Inadequate coverage of iron and folic acid (IFA) intake among pregnant women is influenced by a range of factors. These include infrequent antenatal care (ANC) visits, lower levels of maternal education, belonging to lower wealth quintiles, occupying lower social positions, lack of participation from spouse during antenatal visits, higher birth order, insufficient comprehensive counseling from healthcare providers, unintended pregnancies, and limited exposure to media. These factors have all been associated with reduced odds of pregnant women fully utilizing ANC services, as evidenced by various studies (Ghanekar et al., 2002; Kumar et al., 2019; Varghese et al., 2019). Since IFA consumption is one of the component of effective antenatal care, these are some of the potential barriers and challenges that may discourage pregnant women from adhering to the recommended IFA supplementation. These factors shed light on the circumstances and characteristics associated with lower IFA tablet consumption, helping to identify barriers and challenges that may be discouraging adherence among pregnant women. Recognizing the importance of effective antenatal IFA supplementation, it is imperative to address these challenges. Achieving the expected benefits for maternal and child health hinges on enhancing the coverage and quality of these services, as emphasized in recent research (Billah et al., 2022).

Moreover, the compliance with Iron and Folic Acid (IFA) tablet consumption varies across different states in India. Recognizing these regional disparities is essential to tailor public health interventions effectively and efficiently. By understanding which areas have lower coverage of the IFA, program attention can be directed to where they are most needed. Previous research primarily concentrated on evaluating the effective coverage and determinants of IFA usage in India. Iron and folic acid (IFA) supplementation coverage among pregnant women also is a core process indicator of the Global Nutrition Monitoring Framework (WHO, 2017). However, the coverage of level of the antenatal iron supplementation provides information about the quality and coverage of perinatal medical services. Around 1 in 7 (16%) pregnant women did not taking any (zero) antenatal iron supplementation during their pregnancy in India, which is significant value for lower effective coverage of antenatal iron and folic acid. Therefore, it is essential to identify the patterning and factors of consumption of the zero dose of iron and folic acid supplementation or non-use of the IFA tablet during pregnancy. However, there has been a gap in understanding the specific spatial distribution and high-risk areas for non-compliance with IFA tablet consumption. This study aims to address this gap and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the issue. By identifying high-risk areas and specific factors associated with consumption of zero dose of IFA tablets, public health interventions can be more precisely targeted. This study attempts to analyze the spatial distribution of iron folic acid among pregnant women and enables the identification of high-risk areas, facilitating targeted interventions to optimize resource utilization. Furthermore, addressing various determinants of iron supplementation among pregnant women is crucial for reducing the burden of anemia and enhancing the quality of care provided to expectant mothers.

Data and methods

This study used the National Family Health Survey 2019–21 (NFHS-5) data, which represents the fifth iteration in the NFHS series. NFHS-5 is a comprehensive nationally representative household survey providing a rich dataset on fertility, infant and child mortality, maternal and child health, as well as various nutrition and health services, along with family welfare indicators. These data are stratified by demographic and socioeconomic characteristics at both national, and state (Union Territories, UT) levels. The NFHS-5 survey was carried out in two distinct phases: the first phase took place from June 2019, to January 2020, covering 17 states and 5 Union Territories, while the second phase occurred around November 2020 to April 2021, encompassing 11 states and 3 Union Territories. Overall, NFHS-5 gathered information from 636,699 households, 724,115 women (15–49 years), and 101,839 men (15–54 years). For the purpose of this study, the analysis focused on a sample of 174,947 women (15–49 years) who had given birth in the five years preceding the date of interview in the NFHS-5 survey. We obtained NFHS-2019–21 data for analysis from the publicly accessible DHS Program website: https://dhsprogram.com/.

Variable of the study

The information about consumption of IFA was obtained from woman who had a live birth within five years preceding the survey, by asking the following questions in the survey: “During this pregnancy, were you given or did you buy any iron-folic acid tablets?” and “During the whole pregnancy, for how many days did you take the tablets?” A mother was categorized as zero consumption of IFA tablets if she did not take any IFA tablets during her last pregnancy. Consumption of IFA tablets was treated as a binary outcome (zero IFA = 1 or ever took IFA = 0 in pregnancy) in all analyses.

The independent variables in this study includes women age at birth (15–19 years, 20–29 years and 30 + years), unintended pregnancy (yes and no), received nutrition supplementation from ICDS (yes and no), ANC visits at least one (yes and no), media exposure in a week which is a composition of three variables i.e. reading newspaper/magazine, listening to radio and watching television in a week (yes and no), counseling on health and nutrition (yes and no), place of residence (urban and rural), wealth quintile (richest, rich, middle, poor and poorest), social groups (others, other backward class, schedule tribe and schedule caste), religion (Hindu, Muslims, Christian and others) and women education in years (> 12 years, 9–12 years, 5–8 years, < 5 years, no schooling).

Statistical analysis

The statistical and geospatial analyses were performed using Stata 16.0 SE, Arc GIS 10.8 and Geoda. The analysis involved calculating weighted estimates for sociodemographic and outcome indicators. We implemented the survey design effect to reduce the error estimation due to sampling stages and the sampling method, while estimating the percentages.

In this study, we utilized Pearson's chi-square test and associated p-values to examine the the association between two categorical variables. The Pearson’s chi-square test and p-values determines whether there is a significant association or dependence between outcome variable and exposure variables. Multilevel multivariate logistic regression was used to analyze the factors associated with zero consumption of IFA tablets because of the hierarchical nature of the data set. The multivariate multilevel logistic regression is estimated to show the association at four levels (level 1: individual; level 2: primary sampling unit (PSU or cluster); level 3: district; level 4: state) with 95 percent of confidence interval (CI) and p-value. Before multilevel logistic regression, we checked multi-collinearity between predictors, we used a generalized variance inflation factor, which usually should not exceed five; none of the predictors had a factor greater than three, which indicate that there is no issues of multi-collinearity. The hierarchical model of the survey justified the application of multilevel modelling in this study (Rasbash et al., 2000).

where \({\pi }_{icds}\) is the probability of zero IFA a binary outcome variable i in the cluster j, district k, and state level l (\({\pi }_{ijkl}\)= 1 denotes success or the occurrence of the event, while \({\pi }_{ijkl}\)= 0 denotes failure or lack of occurrence of the event). The parameter \({\beta }_{0}\) is the intercept (mean) of the zero consumption of IFA among pregnant women and \({\beta }_{1}\) represents the effects of the explanatory variables. The random intercepts regression model is based on the assumption that, whilst the intercept or average outcome for individuals with a given set of characteristics varies between higher-level units, the relationship between the dependent and independent variables is consistent across all contexts. Random-effects parameters, \({\alpha }_{jkl}\) is the effect of cluster, \({v}_{kl}\) is the effect of district and \({u}_{l}\) is the effect of states level are the random effect or residuals error term. The residual follow the assumption of independent and normal distribution with zero means and constant variances. The model estimates the variance at different levels: \({\alpha }_{jkl}\) ∼ N (0,\({\sigma }_{j}^{2}\)) is within district, between cluster variance; \({v}_{kl}\) ∼ N (0, \({\sigma }_{k}^{2}\)) is within states, between-district variance and \({u}_{l}\)∼ N (0,\({\sigma }_{l}^{2}\)) represents between-state variance.

The overarching goal of multilevel models is to partition the variance in the outcome across hierarchical data levels. The Variance Partition Coefficient (VPC) is a statistical measure used to assess the proportion of variation in an outcome variable attributed to different factors or sources of variation. It is beneficial in hierarchical or mixed-effects models with multiple levels of nested data. The VPC is a straightforward measure, calculated as the ratio of the variance at a specific geographical level to the combined variance across all levels (Goldstein et al., 2002). This ratio quantifies the portion of variance in the outcome attributed to variations between hierarchical structures. The value of the variance of the underlying individual-level variable, according to the logistic distribution, is π2/3 or 3.29.

The VPC is calculated using the following formula:

where, \({\sigma }_{j}^{2}\) is the community level or cluster variance, \({\sigma }_{k}^{2}\) is the district-level variance and \({\sigma }_{l}^{2}\) is the state level variance.

Spatial analysis

In this study, we employed descriptive maps generated through ArcGIS, which were subsequently exported to GeoDa for spatial analysis. To facilitate our analysis, we employed a first-order contiguity matrix as a weight. Spatial autocorrelation was conducted to investigate whether the distribution of zero consumption of IFA (Iron and Folic Acid) tablets exhibited a random pattern or not. Spatial autocorrelation, quantified by Moran's I, is akin to a Pearson correlation coefficient that assesses the relationship between a variable and its neighboring values within a geographic context. Moran's I is a spatial statistic used to gauge the presence of spatial autocorrelation in an entire dataset, yielding a single output value. The Moran's I value ranges from -1 to 1, with negative values indicating negative spatial autocorrelation and positive values indicating positive spatial autocorrelation (Anselin, 2005). Positive autocorrelation suggests that areas with similar characteristics are clustered closely in space, whereas negative spatial autocorrelation suggests that closely located areas exhibit dissimilar characteristics. A value of Moran's I close to 0 implies the absence of spatial autocorrelation. Additionally, we employed a univariate Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) analysis, which measures the correlation of values within the neighborhood surrounding a specific spatial location. This approach helps identify and quantify the extent of spatial clustering within our data.

Result

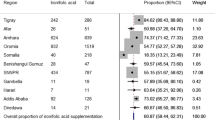

The overall prevalence of zero consumption of IFA among pregnant women in India stands at 15.7% (Fig. 1). The states/UTs with the highest prevalence of zero consumption of IFA among pregnant women are Nagaland (38%), followed by Meghalaya (32%), Bihar (30%), Jammu & Kashmir (30%), Ladakh (29%), and Arunachal Pradesh (27%). Conversely, the states with the lowest prevalence of zero consumption of IFA among pregnant women are Tamil Nadu (2%), followed by Puducherry (4%), Odisha (6%), and West Bengal (6%).

Figure 2 illustrates spatial percentage distribution of zero consumption of IFA among pregnant women on a district level in India. The percentage of zero consumption of IFA among pregnant women was less than 1% in Tiruppur district (0%) of Tamil Nadu and highest in Kiphire district (51.1%) of Nagaland India. Districts in southern India exhibit low percentage (< 10%) of zero tablet consumption of IFA among pregnant women. In contrast, districts in eastern and central India show percentage ranging from > 10% to 20%. Districts in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jammu & Kashmir, and northeastern India have prevalence rates exceeding 30% for zero consumption of IFA among pregnant women.

Univariate LISA map for zero IFA tablet consumption among pregnant women is presented in Fig. 3. The Moran's I value, quantified at 0.59 for zero IFA tablet consumption among pregnant women, signifies a notable degree of spatial autocorrelation within the Indian districts. High-High clustering indicates district with high zero consumption of IFA tablets shares boundaries with similar value of zero consumption of IFA tablets. Low-Low indicates that district with low consumption of zero IFA tablets share boundaries with low zero IFA tablet consumption coverage. High-low and Low–High indicate the spatial outliers, these spatial outliers indicate that district with high zero consumption of IFA tablets share boundaries with low zero consumption and vice-versa. The high-high clusters are mostly concentrated in the districts of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and North Eastern states of Assam and Arunachal Pradesh. We also find a high-high clustering in the northern state of Jammu and Kashmir. While the Low-Low district clusters are concentrated in the districts in southern Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka and also in West Bengal, Jharkhand and Orissa.

Table 1 presents data on the prevalence of zero consumption of Iron and Folic Acid (IFA) among pregnant women in India, organized by various socio-demographic characteristics. The prevalence of zero IFA tablet consumption among pregnant women increases with age of the women. Education level had a substantial impact on IFA tablet consumption, with a notable contrast between women who had more than 12 years of education (10.4%) and women with no schooling (24.8%). When considering social group, the prevalence of zero IFA tablet consumption was 16.2% for those belonging to the Other Backward Class (OBC) and 16.3% for the Scheduled Caste. Examining the socio-economic factor of wealth quintile, it was evident that more women from poorest wealth quintile had zero IFA consumption (20.6%) than those from highest wealth quintile (11.6%). Among women who did not desire pregnancy or childbirth, the prevalence of zero IFA tablet consumption during pregnancy was notably high at 21.6%. Furthermore, 23.6% of women not consume a single IFA tablets when they did not receive nutrition supplementation from anganwadi during pregnancy. A significant difference was observed in zero IFA tablet consumption between women who attended Antenatal Care (ANC) visits and those who did not. Specifically, 38.3% of women who did not attend ANC failed to consume even a single IFA tablet, whereas the figure was significantly lower at 13.9% for women who did attend ANC visits. Additionally, among women who had no media exposure at least once a week, the prevalence of zero IFA consumption stood at 19.9%. Those women who did not receive health and nutrition counseling displayed a 22.2% prevalence of zero IFA tablet consumption.

The odds ratio of zero IFA consumption are derived based on a multilevel multivariate logistic regression (Table 2). Women from poorest families were 33% more likely to have zero consumption of the IFA tablets (OR = 1.33, 95% CI: 1.24, 1.43) than those from the highest wealth quintile. Among women had no schooling were 77% more likely to have zero consumption of IFA tablets as compare with women who had more than 12 years education (OR = 1.77, 95% CI: 1.66, 1.88). Those women belonging from the Muslim religion were 8% more likely to have zero consumption of IFA tablets (OR = 1.08, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.13) as compare with women from Hindu religion. Women who expressed no desire for pregnancy or childbirth were 21% more likely to exhibit zero consumption of IFA tablets (Odds Ratio [OR] 1.21, 95% CI: 1.16 to 1.28). Pregnant women who did not receive nutritional supplementation from Anganwadi during their pregnancy were 50% more likely to experience zero IFA tablet consumption (OR = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.44, 1.55). Non-attendance at Antenatal Care (ANC) visits was associated with an almost threefold increase in the odds of zero IFA tablet consumption (OR = 2.97, 95% CI: 2.84, 3.11). Pregnant women who had no media exposure at least once a week were 12% more likely to have zero consumption of IFA tablets (OR = 1.12, 95% CI: 1.09, 1.16). Lack of access to health and nutrition counseling was linked to a 34% increase in the likelihood of zero IFA tablet consumption (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.29, 1.39).

The multilevel distribution of the Variance Partition Coefficients (VPCs) of the zero consumption of iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets among pregnant women is also reported in Table 2. Outcomes reflected that 5% of the variation in zero consumption of iron and folic acid (IFA) tablets among pregnant women is explained by state level variations, 3% is associated with districts and 15% with PSU level variations.

Discussion

The findings of this analysis provides a valuable insight into the prevalence and socio-demographic factors associated with zero consumption of Iron and Folic Acid (IFA) tablets among pregnant women in India. The bivariate results of this analysis reveal that the prevalence of zero consumption of Iron and Folic Acid (IFA) tablets was more noticeable in several specific subgroups. This included women aged 30 years and older, those who did not utilize ANC services or Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) facilities (indicating they did not receive health and nutrition counseling during pregnancy). Furthermore, a higher proportion of zero IFA tablet consumption was observed among women with no exposure to media, those from the low-income background, individuals belonging to the Other Backward Class (OBC), women of the Muslim faith, and those with lower levels of education.

The analysis revealed that women who did not express a desire for pregnancy or childbirth were significantly associated with zero consumption of IFA tablets. Previous research has explored the link between unintended pregnancies and adherence to antenatal health practices. A study conducted in Ethiopia discovered that women with unwanted pregnancies were significantly less likely to take iron and other vitamin supplements (Seifu et al., 2020). There are studies from Turkey found that women with unplanned pregnancies were less inclined to use vitamins, such as folic acid tablets (Erol et al., 2010; Özkan & Mete, 2010). Conversely, a study in India revealed that unintended pregnancies were associated with reduced odds of comprehensive antenatal care, which includes IFA tablet consumption (Kumar et al., 2019). Recognizing and addressing women's family planning needs and intentions are vital for promoting healthier pregnancies and enhancing compliance with IFA tablets.

Pregnant women who did not access Antenatal Care (ANC) services and were not beneficiaries of ICDS health and nutrition interventions had a higher proportion of zero IFA tablet consumption in India, and this association was statistically significant. The outcomes of this study is consistent with study conducted by Nisar et al. (2014) in Pakistan, in which the findings stated that among pregnant women those were not using ANC services the frequency of and odds for nonuse of antenatal iron folic acid was high. The results of this study align with a prior investigation that identified inadequate utilization of antenatal care services as the primary factor associated with increased odds of non-use of iron folic acid among pregnant women in Indonesia (Titaley & Dibley, 2015). In the present study, the absence of counseling and the lack of ANC services were found to be significantly linked to low IFA consumption, a finding consistent with previous research (Wendt et al., 2015; Siekmans et al., 2018; Gebremichael & Welesamuel, 2020; Mekonen & Alemu, 2021).

Women who had no media exposure at least once a week were 12% more likely to have zero consumption of IFA tablets. This result is in line with previous studies done in Indonesia (Titaley & Dibley, 2015). Evidence from various regions around the world indicates that women who lack exposure to mass media are more likely to have a poor acceptance of iron folic acid during pregnancy compared to women who have better access to media (Agegnehu et al., 2021; Asmamaw et al., 2022; Chourasia et al., 2017; Warvadekar et al., 2018; Wiradnyani et al., 2016). Media, including television, radio, and digital platforms, can serve as powerful tools for disseminating health-related information. This finding underscores the potential of media campaigns in increasing awareness and knowledge regarding the importance of consuming IFA tablets during pregnancy.

The findings also revealed significant associations between socio-economic factors and zero IFA tablet consumption. Women from the poorest families and had no education at all were more likely to have zero consumption of IFA tablets compared to economically better-off households and women those had more than 12 years education. Earlier studies by Nisar et al. (2014) and Titaley and Dibley (2015) have likewise discovered similar results, indicating that women in the lowest household wealth index group with no education had a greater likelihood of not utilizing antenatal IFA supplements during their pregnancies. Furthermore, additional research has steadily shown that both lower wealth status and lower levels of education were associated with inadequate intake of iron folic acid among pregnant women (Boti et al., 2018; Debi et al., 2020; Tamirat et al., 2022). This disparity underscores the need for targeted interventions that address social norms to access. It is observed in this study that women from the Scheduled Tribe households were less likely to have zero consumption of IFA tablets compared to women from other social groups. One possible description may be that as NFHS-2019–21 report showed the utilization of the ICDS services like supplementary food, health check-ups and health and nutrition education during pregnancy through anganwadi centres (AWCs), registration for pregnancy were high among Scheduled tribe than other social groups (IIPS & ICF, 2021). One state specific study from Madhya Pradesh found that the largest share of the Scheduled Tribe women in AWWs was 44% and they more likely to spend time on home visits, that may be increases the access of the iron and folic acid tablets during pregnancy (Jain et al., 2020). However, women belonging to the Muslim religion were 8% more likely to have zero consumption compared to women from the Hindu religion, suggesting the influence of cultural and religious factors. Previous studies from India, have shown that women who belongs to lower social groups and Muslim religions are less likely to adhere recommended dose of iron supplements (Chourasia et al., 2017). Social norms theories explains how these characters of social status influences the consumption behaviours (Rimal et al., 2021).

The spatial analysis revealed that there is a spatial distribution of zero consumption of iron folic acid among pregnant women across the country. This distribution was confirmed by significant positive spatial autocorrelation identified by the Moran's I statistic and significant local clusters identified by LISA. This indicates the presence of spatial variations in the prevalence of zero consumption of iron folic acid. The areas with significant hotspots, where zero consumption of iron folic acid is more prevalent, were found in the northern, central, eastern, and north-eastern regions of India. On the other hand, low-low clusters, indicating lower prevalence, were mainly concentrated in the southern states of the country. This clustering of zero consumption of iron folic acid can be attributed to various factors such as low utilization of Antenatal Care (ANC), adherence to social norms, geographical location, limited access to healthcare services, inadequate counselling and health knowledge, high levels of illiteracy among women, and issues related to women's autonomy. These factors are in line with findings from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) reports from 2019–2021. There can be additional supply side factors affecting the IFA coverage in these hotspot districts and should be explored in further research on this subject.

While this study provides valuable insights, there are limitations to consider. The data are based on self-reporting in their last pregnancy, which could be up to five years prior to the survey, and is thus not free from recall bias. Since it is based on cross-sectional data there is no causal inference. Additionally, other unmeasured factors, such as cultural beliefs and access to healthcare infrastructure, maternal knowledge about the importance of iron/folic acid supplements, the adverse effects experienced by mothers when taking the supplements, or the influence of other family members in encouraging mothers to take the supplements and also supply side factors like distribution of IFA, may influence IFA tablet consumption. Nevertheless, this research contributes to the understanding of the factors influencing IFA tablet intake among pregnant women in India and highlights the need for targeted interventions to improve maternal and child health outcomes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the prevalence and risk factors associated with zero consumption of Iron and Folic Acid (IFA) tablets among pregnant women in India across various socio-demographic characteristics. The bivariate analysis highlights the higher prevalence of zero IFA tablet consumption in specific subgroups, including women aged 30 years and older, those who did not utilize Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) facilities, women with no media exposure, those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, individuals belonging to the Other Backward Class (OBC), women of the Muslim faith, and those with lower levels of education. Notably, unintended pregnancies, not receiving of nutritional supplementation from ICDS, infrequent Antenatal Care (ANC) visits, absence of media exposure, and insufficient health and nutrition counselling were all significant factors associated with zero IFA tablet consumption. Socio-economic factors, such as wealth quintile and education level, also played a crucial role, with women from the poorest families and those with no education being more likely to have zero consumption of IFA tablets. This study have explored the spatial disparities and confirm the presence of spatial heterogeneity to the zero consumption of Iron folic acid at district level in India. Addressing these challenges and disparities in IFA tablet consumption among pregnant women is essential for improving maternal and child health outcomes in India. In India, the ongoing program is focused on monitoring the distribution of iron and folic acid supplements to pregnant women through ANC/ANM/ASHA as part of the Anemia Mukat Bharat initiative. Our study recommends adopting a monthly DOTS based strategy for encouraging practice of IFA consumption. This can also enhance the reach of IFA tablets by ensuring that pregnant women take their first IFA tablet during their initial visit at the ANC point (place), when they first register for pregnancy under the supervision of ANC/ANM/ASHA or during their first interaction with healthcare personnel. Further research is also necessary to understand the underlying reasons behind these associations and to develop effective, context-specific interventions.

References

Agegnehu, C. D., Tesema, G. A., Teshale, A. B., Alem, A. Z., Yeshaw, Y., Kebede, S. A., & Liyew, A. M. (2021). Spatial distribution and determinants of iron supplementation among pregnant women in Ethiopia: A spatial and multilevel analysis. Archives of Public Health, 79(1), 1–14.

Ahankari, A. S., Myles, P. R., Dixit, J. V., Tata, L. J., & Fogarty, A. W. (2017). Risk factors for maternal anaemia and low birth weight in pregnant women living in rural India: A prospective cohort study. Public Health, 151, 63–73.

Ahmad, K., Singh, J., Singh, R. A., Saxena, A., Varghese, M., Ghosh, S., ... & Patel, N. (2023). Public health supply chain for iron and folic acid supplementation in India: Status, bottlenecks and an agenda for corrective action under Anemia Mukt Bharat strategy. Plos one, 18(2), e0279827.

Anselin, L. (2005). Exploring spatial data with GeoDaTM: A workbook. Center for Spatially Integrated Social Science, 1963, 157.

Asmamaw, D. B., Debebe Negash, W., Bitew, D. A., & Belachew, T. B. (2022). Poor adherence to iron-folic acid supplementation and associated factors among pregnant women who had at least four antenatal care in Ethiopia. A community-based cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Nutrition, 9, 1023046.

Billah, S. M., Raynes-Greenow, C., Ali, N. B., Karim, F., Lotus, S. U., Azad, R., & El Arifeen, S. (2022). Iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnancy: Findings from the baseline assessment of a maternal nutrition service programme in Bangladesh. Nutrients, 14(15), 3114.

Bothwell, T. H. (2000). Iron requirements in pregnancy and strategies to meet them. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 72(1), 257S-264S.

Boti, N., Bekele, T., Godana, W., Getahun, E., Gebremeskel, F., Tsegaye, B., & Oumer, B. (2018). Adherence to Iron-folate supplementation and associated factors among pastoralist’s pregnant women in Burji districts, Segen area people’s zone, Southern Ethiopia: Community-based cross-sectional study. International journal of reproductive medicine, 2018(1), 2365362.

Caniglia, E. C., Zash, R., Swanson, S. A., Smith, E., Sudfeld, C., Finkelstein, J. L., ... & Shapiro, R. L. (2022). Iron, folic acid, and multiple micronutrient supplementation strategies during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes in Botswana. The Lancet Global Health, 10(6), e850-e861.

Chourasia, A., Pandey, C. M., & Awasthi, A. (2017). Factors influencing the consumption of iron and folic acid supplementations in high focus states of India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 5(4), 180–184.

Debi, S., Basu, G., Mondal, R., Chakrabarti, S., Roy, S. K., & Ghosh, S. (2020). Compliance to iron-folic-acid supplementation and associated factors among pregnant women: A cross-sectional survey in a district of West Bengal, India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 9(7), 3613.

Dewey, K. G., & Oaks, B. M. (2017). U-shaped curve for risk associated with maternal hemoglobin, iron status, or iron supplementation. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 106(suppl_6), 1694S-1702S.

Erol, N., Durusoy, R., Ergin, I., Döner, B., & Çiçeklioğlu, M. (2010). Unintended pregnancy and prenatal care: A study from a maternity hospital in Turkey. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care, 15(4), 290–300.

Gebremichael, T. G., & Welesamuel, T. G. (2020). Adherence to iron-folic acid supplement and associated factors among antenatal care attending pregnant mothers in governmental health institutions of Adwa town, Tigray, Ethiopia: Cross-sectional study. PLoS One, 15(1), e0227090.

Georgieff, M. K. (2020). Iron deficiency in pregnancy. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 223(4), 516–524.

Gevariya, R., Oza, H., Doshi, H., & Parikh, P. (2015). Epidemiology, Risk Factors and Outcome of Complications in Obstetric and Gynecological Surgeries—A Tertiary Center Experience from Western India. Journal of US-China Medical Science, 12, 45–52.

Ghanekar, J., Kanani, S., & Patel, S. (2002). Toward better compliance with iron–folic acid supplements: Understanding the behavior of poor urban pregnant women through ethnographic decision models in Vadodara, India. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 23(1), 65–72.

Goldstein, H., Browne, W., & Rasbash, J. (2002). Partitioning variation in multilevel models. Understanding Statistics: Statistical Issues in Psychology, Education, and the Social Sciences, 1(4), 223–231.

Hidayat, Z. Z., Ajiz, E. A., & Krisnadi, S. R. (2016). Risk factors associated with preterm birth at hasan sadikin general hospital in 2015. Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 6(13), 798.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. (2021). National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), 2019–21: India. Mumbai: IIPS.

Jain, A., Walker, D. M., Avula, R., Diamond-Smith, N., Gopalakrishnan, L., Menon, P., ... & Fernald, L. C. (2020). Anganwadi worker time use in Madhya Pradesh, India: a cross-sectional study. BMC health Services Research, 20, 1–9.

Jikamo, B., & Samuel, M. (2018). Non-adherence to iron/folate supplementation and associated factors among pregnant women who attending antenatal care visit in selected Public Health Institutions at Hosanna Town, Southern Ethiopia, 2016. J Nutr Disord Ther, 8(230), 2161–509.

Kumar, G., Choudhary, T. S., Srivastava, A., Upadhyay, R. P., Taneja, S., Bahl, R., ... & Mazumder, S. (2019). Utilisation, equity and determinants of full antenatal care in India: analysis from the National Family Health Survey 4. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 19(1), 1–9.

Kumari, S., Garg, N., Kumar, A., Guru, P. K. I., Ansari, S., Anwar, S., ... & Sohail, M. (2019). Maternal and severe anaemia in delivering women is associated with risk of preterm and low birth weight: A cross sectional study from Jharkhand, India. One Health, 8, 100098.

Mekonen, E. G., & Alemu, S. A. (2021). Determinant factors of poor adherence to iron supplementation among pregnant women in Ethiopia: A large population-based study. Heliyon, 7(7), e07530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07530

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. (2018). Intensified national iron plus initiative (I-NIPI): operational guidelines for programme managers. Available online: https://anemiamuktbharat.info/wpcontent/uploads/2019/09/Anemia-Mukt-Bharat-Brochure_English.pdf Accessed 30 Oct 2023.

Nisar, Y. B., Dibley, M. J., & Mir, A. M. (2014). Factors associated with non-use of antenatal iron and folic acid supplements among Pakistani women: A cross sectional household survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 14(1), 1–12.

Özkan, İA., & Mete, S. (2010). Pregnancy planning and antenatal health behaviour: Findings from one maternity unit in Turkey. Midwifery, 26(3), 338–347.

Puri, A., Yadav, I., & Jain, N. (2011). Maternal mortality in an urban tertiary care hospital of north India. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology of India, 61, 280–285.

Rasbash, J., Browne, W., Goldstein, H., Yang, M., Plewis, I., Healy, M., Woodhouse, G., Draper, D., Langford, I., & Lewis, T. (2000). A User's Guide to MLwiN (2nd Eds). Institute of Education, University of London. https://www.bristol.ac.uk/cmm/media/software/mlwin/downloads/manuals/3-00/manual-print.pdf

Rimal, R. N., Yilma, H., Sedlander, E., Mohanty, S., Patro, L., Pant, I., ... & Behera, S. (2021). Iron and folic acid consumption and changing social norms: cluster randomized field trial, Odisha, India. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 99(11), 773.

Seifu, C. N., Whiting, S. J., & Hailemariam, T. G. (2020). Better-educated, older, or unmarried pregnant women comply less with iron–folic acid supplementation in southern Ethiopia. Journal of Dietary Supplements, 17(4), 442–453.

Siekmans, K., Roche, M., Kung’u, J. K., Desrochers, R. E., & De-Regil, L. M. (2018). Barriers and enablers for iron folic acid (IFA) supplementation in pregnant women. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 14, e12532.

Stevens, G. A., Paciorek, C. J., Flores-Urrutia, M. C., Borghi, E., Namaste, S., Wirth, J. P., ... & Rogers, L. M. (2022). National, regional, and global estimates of anaemia by severity in women and children for 2000–19: a pooled analysis of population-representative data. The Lancet Global Health, 10(5), e627-e639.

Tamirat, K. S., Kebede, F. B., Gonete, T. Z., Tessema, G. A., & Tessema, Z. T. (2022). Geographical variations and determinants of iron and folic acid supplementation during pregnancy in Ethiopia: Analysis of 2019 mini demographic and health survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 22(1), 127.

Titaley, C. R., & Dibley, M. J. (2015). Factors associated with not using antenatal iron/folic acid supplements in Indonesia: The 2002/2003 and 2007 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 24(1), 162–176.

Varghese, J. S., Swaminathan, S., Kurpad, A. V., & Thomas, T. (2019). Demand and supply factors of iron-folic acid supplementation and its association with anaemia in North Indian pregnant women. PLoS ONE, 14(1), e0210634.

Vijayaraghavan, K., Brahmam, G. N. V., Nair, K. M., Akbar, D., & Pralhad Rao, N. (1990). Evaluation of national nutritional anemia prophylaxis programme. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics, 57, 183–190.

Warvadekar, K., Reddy, J., Sharma, S., Dearden, K. A., & Raut, M. K. (2018). Socio-demographic and economic determinants of adherence to iron intake among pregnant women in selected low and lower middle income countries in Asia: Insights from a cross-country analyses of global demographic and health surveys. Intl J Comm Med Public Health, 5(4), 1552–1569.

Wendt, A., Stephenson, R., Young, M., Webb-Girard, A., Hogue, C., Ramakrishnan, U., & Martorell, R. (2015). Individual and facility-level determinants of iron and folic acid receipt and adequate consumption among pregnant women in rural Bihar, India. Plos One, 10(3), e0120404.

WHO (2019). Every newborn: an action plan to end preventable deaths. https://www.who.int/initiatives/every-newborn-action-planAccessed 21 Oct 2021.

Wiradnyani, L. A. A., Khusun, H., Achadi, E. L., Ocviyanti, D., & Shankar, A. H. (2016). Role of family support and women’s knowledge on pregnancy-related risks in adherence to maternal iron–folic acid supplementation in Indonesia. Public Health Nutrition, 19(15), 2818–2828.

World Health Organization. (2016). WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. In WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience (pp. 152-152).

World Health Organization. (2017). Global nutrition monitoring framework: Operational guidance for tracking progress in meeting targets for 2025.

Yadav, K., Namdeo, A., & Bhargava, M. (2013). A retrospective and prospective study of maternal mortality in a rural tertiary care hospital of Central India. Indian Journal of Community Health, 25(1), 16–21.

Funding

There is no funding for preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Consent for publication

All authors consent to participate and publication of the article.

Ethical approval

No ethical approval required.

Conflict of interest

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Verma, A., Banerjee, A., Gaur, A.K. et al. Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Zero Consumption of Iron and Folic Acid (IFA) among Pregnant Women in India: Evidence from National Family Health Survey, 2019–21. GeoJournal 89, 217 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-024-11151-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-024-11151-1