Abstract

This work examines what role children play in the re-partnering process in five European countries (Norway, France, Germany, Romania, and the Russian Federation) by addressing the following research questions: (1) To what extent do men and women differ in their re-partnering chances?; (2) Can gender differences in re-partnering be explained by the presence of children?; (3) How do the custodial arrangements and the child’s age affect the re-partnering chances of men and women? We use the partnership and parenthood histories of the participants in the first wave of the Generations and Gender Survey (United Nations, Generations and Gender Programme: Survey Instruments. United Nations, New York/Geneva, 2005) to examine the transition to moving in with a new partner following the dissolution of the first marital union, separately for men and women. The story that emerges is one of similarities in the effects rather than differences. In most countries, men are more likely to re-partner than women. This gender difference can be attributed to the presence of children as our analyses show that childless men and women do not differ in their probability to re-partner. Mothers with resident children are less likely to re-partner than non-mothers and a similar though often non-significant effect of resident children is observed for fathers. In most countries we find that as the child ages, the chances to enter a new union increase. In sum, our study indicates that children are an important factor in re-partnering and a contributor to the documented gender gap in re-partnering, and this holds throughout distinct institutional and cultural settings.

Résumé

Cet article étudie le rôle joué par les enfants dans la formation d’une nouvelle union dans cinq pays européens (Norvège, France, Allemagne, Roumanie et la Fédération de Russie) en tentant de répondre aux questions de recherche suivantes (1) dans quelle mesure les probabilités des hommes et des femmes de former une nouvelle union diffèrent-elles ? (2) la présence d’enfants peut-elle expliquer les différences de genre dans ce domaine ? (3) Les dispositions relatives à la garde de l’enfant et l’âge de l’enfant ont-ils un impact sur les probabilités d’une nouvelle union pour les hommes et pour les femmes ? Les histoires des unions et les histoires parentales des participants à la première vague des enquêtes Générations et Genre (GGS, Nations Unies ?, 2005) ont été utilisées pour étudier la transition vers une nouvelle union après la dissolution du premier mariage pour les hommes et pour les femmes séparément. Les résultats montrent des effets semblables plutôt que divergents. Dans la plupart des pays, les hommes ont des probabilités de former une nouvelle union plus élevées que les femmes. Cette différence de genre peut être attribuée à la présence d’enfants car nos analyses montrent que les probabilités d’une nouvelle union des hommes et des femmes sans enfant sont similaires. Les mères dont les enfants vivent avec elles sont moins susceptibles de former une nouvelle union que les femmes sans enfant, un effet semblable quoique non significatif étant observé pour les pères vivant avec leurs enfants. Dans la plupart des pays, plus l’enfant est âgé et plus les chances de former une nouvelle union augmentent. En résumé, notre étude montre que les enfants jouent un rôle important dans la transition vers une nouvelle union et qu’ils contribuent aux différences de genre, déjà connues, dans la formation d’une nouvelle union, ceci quels que soient les contextes culturels et institutionnels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The steady rise in divorce rates across Western countries has made researchers progressively more interested in understanding the possible subsequent transition to a new marital or cohabiting union. In this work, we focus on what role children might play in the re-partnering process in five European countries (Norway, France, Germany, Romania, and the Russian Federation) by addressing the following research questions: (1) To what extent do men and women differ in their re-partnering chances?; (2) Can gender differences in re-partnering be explained by the presence of children?; and (3) How do the custodial arrangements and the child’s age affect the re-partnering chances of men and women?

The entrance into a new partnership following a marital dissolution is important because of its potential to counteract some of the documented negative effects which divorce can have. For example, though divorced men and women generally report lower adjustment than their married counterparts (for an overview, see Amato 2010), the presence of a new romantic partner has been shown to be positively correlated with adult well-being (e.g., Wang and Amato 2000). Furthermore, divorce has been found to result in a substantial decline in income for women in particular (Ongaro et al. 2009; Poortman 2000) which however, can be offset by a remarriage (Dewilde and Uunk 2008; see Sweeney 2010). Empirical evidence suggests that the majority of divorcees re-partner (for an overview, see Coleman et al. 2000; Sweeney 2010) with a probably stronger preference for cohabitation over remarriage (Wu and Schimmele 2005). Yet, this likelihood to re-partner and the time between divorce and new partnership can vary greatly between individuals (Coleman et al. 2000). For example, women have consistently been shown to fare worse off than men on the re-partnering market, with lower overall re-partnering chances and longer time between separation and next union (e.g., Coleman et al. 2000; de Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Meggiolaro and Ongaro 2008; Poortman 2007; Skew et al. 2009; Wu and Schimmele 2005). In fact, it has even been noted that “gender is the most crucial determinant in the re-partnering process” (Wu and Schimmele 2005, p. 27) and a number of factors have been suggested as contributing this gender gap (e.g., women benefiting less from partnerships than men and earlier relationship history; Skew et al. 2009).

Earlier work has also shown that the presence of children can complicate the process of re-partnering with divorced parents being less likely to form a (marital or cohabiting) relationship than divorcees without children (e.g., Bumpass et al. 1990; Koo et al. 1984; Teachman and Heckert 1985). However, children have been shown to affect women’s and men’s chances to re-partner somewhat differently (e.g., Coleman et al. 2000; de Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Meggiolaro and Ongaro 2008; Poortman 2007; Wu and Schimmele 2005). Previous work has generally demonstrated that mothers are less likely to re-partner than non-mothers. The effects have been shown to vary somewhat according to the number and ages of the children with for example, having younger children resulting in even lower likelihood to re-partner (De Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Koo et al. 1984; Lampard and Peggs 1999; Meggiolaro and Ongaro 2008; Poortman 2007; Sweeney 2002; Wu and Schimmele 2005).

The findings with respect to men’s chances are less clear. Work from the United States has shown that men’s chances to form a new union are not affected by the presence of resident children and are even increased by having non-resident children (Stewart et al. 2003). Empirical work in Canada has also shown that young children improve men’s chances to enter a cohabiting union (Wu and Schimmele 2005). Some European studies have also shown that co-resident children increase men’s chances of forming a union with a non-parent (Bernhardt and Goldscheider 2002) whereas others have not found this positive effect of children on men’s re-partnering chances (e.g., De Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Poortman 2007). In light of these mixed findings, it has been noted that it is important to also consider that the process of re-partnering can depend on the macro-level context in which it occurs (Meggiolaro and Ongaro 2008; Mills 2004).

In this study, we investigate if and how the presence of children (including their post-separation residence and age) affects men’s and women’s chances to re-partner after the separation from their first marital partner. In doing so, we contribute to the understanding of what role children might play in the previously documented gender gap in re-partnering. In line with earlier works (e.g., Lampard and Peggs 1999; Skew et al. 2009; Stewart et al. 2003) we propose that an important explanation for this gender gap is in fact, the presence of children. We add to this literature by providing an impression to what extent this child effect is universal across five European countries which are rather distinct in their institutional and cultural contexts (Norway, France, Germany, Romania, and the Russian Federation). We use recently collected data from the Generations and Gender Survey (GGS; United Nations 2005). The GGS data are unique in that they contain cross-comparative partner and parenthood history data for a number of (primarily) European countries. We replicate earlier work on the effect of children on re-partnering and build upon it by using comparable data and analyses across the five countries. Furthermore, we are able to address in further detail the issue of how children’s residence and ages can affect not only women’s chances to re-partner (which has been the focus of many of the earlier works) but also men’s likelihood to establish a new union after separation.

2 Why Can Children Affect Re-partnering?

To understand why children might be an important element in the re-partnering process, we need to consider three important factors which affect people’s initiation of a new union: need, attractiveness, and opportunity (Becker 1993; de Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Goldscheider and Waite 1986; Oppenheimer 1988). On the one hand, people with children might have a higher need and thus, incentive to re-partner after experiencing a divorce than divorcees without dependent children. As previously mentioned, women’s economic situation in particular is adversely affected by the dissolution of a marital union (Ongaro et al. 2009; Poortman 2000) which can be especially problematic for those with dependent children. This need is likely highest when the children are young and/or reside at home and thus, limit the ability to participate fully in the labor market. This need argument is probably not as applicable to men as divorce tends not have the same repercussions for their economic situation as for women (Poortman 2000). In other words, according to this argument, women with children should be more likely to re-partner after separation than women without children. Yet, as previously elaborated, research does not necessarily support this expectation (Coleman et al. 2000). It is also important to consider that both men and women with children might be less interested in entering a second union because their desire to be a parent has already been met in the first union (Meggiolaro and Ongaro 2008).

Another way in which children might affect one’s re-partnering chances is by a decrease in the person’s attractiveness to potential new partners. The presence of children from a previous union means that the new partner will have to make an investment in a relationship with non-biological offspring and to potentially act as a stepparent, a role which has been found to be at times problematic (Stewart et al. 2003). This consideration might be particularly strong in the case of resident children though it might be less challenging if the child is young when the new partner enters the household (for an overview of stepparent–child relations, see Cherlin and Furstenberg 1994). Here, it is also important to note that children might affect men’s and women’s attractiveness to potential partners differently. Studies on mate-selection preferences have shown that women are consistently more willing than men to form a union with someone who has children (South 1991). This can be interpreted as a so-called “good-father effect” where a man’s attractiveness to potential partners is increased by his involvement in the lives of his children. Such parental commitment on part of the man is essentially testifying to his willingness to provide for his offspring. However, the same probably does not apply to women because their involvement in child-rearing (signaled by for example, full-time child residence with the mother) is seen as highly normative and is thus, not necessarily additionally “rewarded” on the remarriage market. On the other hand, lack of maternal engagement in her children’s lives (signaled by for example, the children’s full-time residence with the father) might be particularly censured on the re-partnering market.

Finally, children might affect the probability of re-partnering because of the constraints that they put on the opportunities to meet a new partner. Due to heightened caring obligations, young and resident children in particular are likely to reduce the time and energy that custodial parents can spend on leisure activities and on socializing with potential new partners (Koo et al. 1984). Additionally, children can actively oppose their parents’ dating and possible re-partnering (Koo et al. 1984). It is also important to note here that though children have been shown to impact both men’s and women’s social networks, these effects tend to be gender specific; whereas fathers mostly temporarily increase the kin composition of their social network after the birth of a child, for women, having children results in a reduction in the size of the social network and the volume of contacts, at least until the children reach school age (Munch et al. 1997). The restricted opportunities to meet and mate might be especially strong when the children restrict the labor force participation (e.g., because they are too young or there are no alternative childcare options), as work has been shown to be the most important place to meet new partners in the remarriage market (De Graaf and Kalmijn 2003).

In line with the arguments outlined above, in this paper we re-examine the effects of children on re-partnering for men and women. Firstly, we investigate if and to what extent women have lower chances of re-partnering after marital separation. In line with earlier empirical findings (e.g., Coleman et al. 2000; de Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Meggiolaro and Ongaro 2008; Poortman 2007; Skew et al. 2009; Wu and Schimmele 2005), we expect to find a lower likelihood of re-partnering for women compared to men. Secondly, we consider what role children play in creating the gender gap on the re-partnering market. To do so we examine the transition to moving in with a new partner only for the non-parents. If children are indeed the main contributor to the gender disparities in re-partnering, we expect to find that gender does not play a significant role in predicting childless people’s transition to next union.

Subsequently, we examine the possible child effect in detail. First, we examine how the effect of children on re-partnering differs between women and men. In line with previous work in the European context (e.g., De Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Poortman 2007), we expect to find a negative effect of parenthood on re-partnering for both men and women (with stronger effects for women). Subsequently, we make a distinction between coresident children, (only) non-resident children, and never having had any children. In other words, we examine if there is a certain parenthood effect on re-partnering for men and women or whether it is children’s residence that affects the chances of forming a new union. We expect that it is a coresidence issue: persons with coresident children will have a comparatively low likelihood of forming a new union as their opportunities to socialize with potential new partners are likely most restricted and their attractiveness to potential new partners might be particularly low because of the presence of a child in the home. As men’s attractiveness on the remarriage market may be less or even positively affected by coresident children, we expect to find a weaker negative effect of coresident children for men. We hypothesize that having (only) non-resident children positively affects men’s re-partnering chances (due to weak restrictions to re-partner and the “good-father effect”), whereas for women the effect of non-resident children may (due to the weak restrictions to re-partner and counteracting arguments on attractiveness) be absent.

Finally, we examine how the age of the youngest child affects re-partnering. Here, we make a distinction between the effect of age while the child is still highly dependent on his or her parents (i.e., before the age of 18) and after this transition. In our work, reaching the age of majority can also be seen as a proxy for leaving the parental home and thus, reducing whatever restrictions a resident child might put on the parent’s re-partnering chances. The general expectation is that the more dependent the child is (i.e., younger and before the age of 18), the less attractive the parents are to potential new partners and the fewer chances they have to meet such partners. Therefore, we expect to see a positive effect of the child’s age on the chances of re-partnering. However, once the child reaches the age of majority, we expect to no longer see a significant effect of age because of the increase in autonomy and thus, decrease in parental responsibilities.

3 Can the Effect of Children on Re-partnering Be Modified by Country Characteristics?

Though the question of how children can affect the transition to a second union has been addressed before, the majority of that research focuses on women and on the North American context (Bernhardt and Goldscheider 2002). Yet, an argument can be made that the needs, attractiveness, and opportunities of parents might be modified by the cultural and institutional contexts in which they are embedded. Therefore, in our work, we explore to what extent the effect of children on men’s and women’s chances to re-partner is similar in different contexts. We focus on five countries: Norway, France, Germany, Romania, and the Russian Federation. These are chosen because they vary in the risk of poverty for single parents with dependent children (thus, affecting the financial need to re-partner), in the degree to which divorce is common in the country (which can affect the attractiveness of divorced parents), and in the extent to which they provide caring support to parents with young children (e.g., public day care) and the attitudes towards using these services (which can affect the opportunities to meet new partners). Though we outline these variations in the subsequent section, we do not aim to present an exhaustive exploration of the child related policies and practices in each country. Rather, this overview is meant to help contextualize the re-partnering process.

An institutional factor to consider is the generosity of social transfers. According to data presented by Eurostat (2012), the risk of poverty in 2007 (operationalized as having income after social transfers which is below the poverty threshold) for single people living with at least one dependent child was highest in Romania, followed by Germany, Norway, and France. As for Russian Federation, though no comparative work is available, previous findings indicate that single-parent households in the Russian Federation are more likely to be persistently poor than other types of families (Lokshin and Popkin 1999). Furthermore, publications by the International Monetary Fund note that benefits in the Russian Federation are low, with family allowance covering an average of 12 % of the subsistence minimum for children (Sederlof 2000). In other words, if it is in fact the financial need which drives the re-partnering process, we should see that divorcees with children are most likely to re-partner in Romania and the Russian Federation, followed by Germany, Norway, and finally, France.

Another, more cultural factor to consider is how common and accepted divorce is in the country. The argument here is that in countries with particularly low divorce rates, divorced parents are even less attractive on the remarriage market because of the possible stigma associated with divorce. Therefore, people in these marriage markets likely tend to search for partners who closely resemble never-married individuals (i.e., with few ties to their previous marriage; Meggiolaro and Ongaro 2008). The net divorce rates (number of divorces per 1,000 married women) for the 1990–2000 period indicate that divorce is least common in Romania (5.57), followed by Germany (6.41), France (9.19), Norway (11.80) and finally the Russian Federation (17.95; Kalmijn 2007). In light of these differences, we would to expect that divorced parents are least attractive to potential new partners and least likely to remarry in Romania, followed by Germany, France, Norway, and finally the Russian Federation.

The final country level factor which we consider here is the country’s childcare system, a factor that is both institutionally and culturally determined. Our reasoning is that in countries with high childcare provisions, divorced parents (and especially those with resident children) will have more opportunities to re-partner both via higher labor market participation and by having more leisure time to meet potential partners. The existing provisions in France and Norway aim at almost full coverage of the needs for formal childcare for children over the age of three, with some difficulties to meet the demand for care of younger children (European Commission 2009). Though these countries are similar with respect to the availability of formal childcare, the (cultural) attitudes towards using these services differ somewhat. Qualitative work shows that the attitudes towards institutionalized childcare in France, including for 3- to 4-month-old babies, are rather favorable (European Commission 2009). In Norway, however, the “informal norms imply that ‘good parents’ do not fully use the hours of the contracted services” for very young children (European Commission 2009, p. 54) and according to public statements from the Norwegian Children’s Ombudsman, “children should not spend too many hours in day care” (European Commission 2009, p. 52). For Germany, the inability to meet the demand for childcare is higher with some reports stating that, “the insufficient provision of formal childcare obstructs participation in the labor market” (European Commission 2009, p. 40). Furthermore, there is less uniformity in German attitudes towards using childcare, with the majority of parents becoming interested in public services only once the child turns 2 years old (European Commission 2009). In Romania, both the level of coverage and the quality of the provided services are found to be rather low (European Commission 2009). This is also reflected in the finding that the average enrolment rate of children under the age of three in formal childcare is lower in Romania than in Germany (OECD 2012a). It is, however, important to note here that the use of informal childcare arrangements in Romania is among the highest in Europe (OECD 2012b) thus, possibly compensating for the lack of formal childcare facilities. For the Russian Federation, the situation changed dramatically after the 1991 transition. Whereas in the 1980s about 70 % of children between the ages of one and six were registered in public (and heavily state subsidized) childcare facilities, that proportion dropped by more than 50 % by the mid-1990s due to the sudden increase in costs (Rieck 2006). Unfortunately, studies on childcare attitudes are not available for Romania and the Russian Federation. In summary, the childcare system appears to be of highest quality and availability in France and Norway, followed by Germany, Romania, and the Russian Federation. In relation to our arguments, that would mean that parents’ opportunities to engage in the re-partnering market and to re-partner are likely least restricted in France and Norway, followed by Germany, Romania, and the Russian Federation (hereafter and in the tables, referred to in the abbreviated form, Russia).

As can be seen from this short overview, some characteristics within a country might work to facilitate the re-partnering process, whereas others might impede it (an outline of the different effects can be found in Table 1). Therefore, the comparative goal of this paper is framed as largely explorative. Yet, one could anticipate (based on our overview in Table 1) that parents will be least likely to re-partner in Romania (due to the low divorce rates and restricted formal child-care options) and most likely, in Norway (where we see high divorce rates and higher quality child-care facilities) and the Russian Federation (high divorce rates and high risk of poverty). In our work, we also control for several important re-partnering differentials: duration of the marital union, current age, and the respondent’s educational level (as proxy for socioeconomic status). Previous work has already shown that these can have gender-specific effects on the likelihood to re-partner (e.g., Wu and Schimmele 2005). We also introduced a control for the historical time in which the respondents separated from their divorce partners (i.e., separation cohort). Evidence (based on Dutch data) suggests that there are gender-specific historical trends in the likelihood to re-partner, with women “catching up” to men in their re-partnering chances (De Graaf and Kalmijn 2003).

4 Data and Measures

In order to address our research questions, we use data from the GGS (United Nations 2005). A detailed description of the survey’s design, scope, and aims can be found in Vikat et al. (2007). The GGS is designed as a panel study of nationally representative samples of men and women, between the ages of 18 and 79, in each of the participating developed (mainly) European countries. In this paper, we focus on the first of the three planned data collections which was conducted in 2005 in France, Germany, and Romania, 2004 in Russia, and in 2007/2008 in Norway. This first wave includes retrospective information on the fertility and partnership histories of the participants collected during structured face-to-face interviews in the respondents’ homes. The original sample sizes for the five countries are displayed in Table 2. More information about the data collection and characteristics of the national samples can be found in the 2005 publication of the United Nations.

As previously noted, these five countries provide an interesting variation in context which was our main motivation for selecting them for these analyses. However, an additional reason to focus on these five countries rather than on all European countries present in the GGS was the fact that in most of the other countries, the respondents were not asked about their children’s place of residence following the dissolution of the marital union (e.g., Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands). We also found that though other European countries included the question on child residence, the sample of respondents at risk for re-partnering was too small to allow any meaningful comparisons to be made between parents and non-parents (e.g., there were only 368 participants at risk for re-partnering in Austria of which only 127 (38 men) were not parents). In light of our substantive, as well as, these methodological considerations, we proceeded with our focus on Norway, France, Germany, Romania, and Russia.

The data collection on previous partnerships was restricted to unions where the partners either lived together for a minimum of 3 months or were married (Vikat et al. 2007). We select respondents who reported that they were married and subsequently, separated from that marital partner (n = 2,322 for Norway or 15.6 % of the original sample, n = 1,341 for France or 13.3 % of the original sample, n = 1,111 for Germany or 11.1 % of the original sample, n = 943 for Romania or 7.9 % of the original sample size, and n = 2,365 for Russia or 21.0 % of the original sample). In this work, we focus on re-partnering after the dissolution of a marital union in particular. Though clear evidence exists that cohabitation is quite common in countries such as Norway and France, studies have also shown that great diversity exists among European countries not only in the incidence of cohabitation (e.g., Kiernan 2001) but also in its institutionalization and meaning for adult well-being (e.g., Soons and Kalmijn 2009). Therefore, as a way to keep the samples at risk for re-partnering somewhat more comparable across the five countries, we focus on re-partnering after the dissolution of a marriage rather than cohabitation. Though the participants could report multiple marital unions, we focus on the first which ended in separation and on the self-reported timing of the separation from the ex-partner (the month and year).

In our work, the dependent event of interest is the self-reported month and year when the respondent started living together with a new partner after the separation. As mentioned earlier, the partners had to live together for at least 3 months for the union to be recorded. It is important to note here that we do not make a distinction between the co-residential unions which were also marriages and those that were not. In other words, for some of the respondents these partnerships were cohabitations (i.e., non-marital co-residential union), for others, they had transitioned to marriages, whereas for some, they were dissolved by the time of the interview. We exclude all respondents for whom the time between separation and moving in with a new partner was 9 months or less. As one of our primary interests here is how the re-partnering process might be affected by the presence of children, we want to focus on participants who do in fact spent some time on the “re-partnering market”. Therefore, we want to avoid the cases where the dissolution of the previous union is in fact, precipitated by the presence of a new romantic partner. An additionally performed check demonstrated that the vast majority of the re-partnerings which happened within the first year after separation took place within the first 6 months (62.9 % for Norway, 72.9 % for France, 56.2 % for Germany, 61.3 % for Romania, and 69.7 % for Russia). Yet, we opted for the nine-month cut-off as a way to ensure the birth of any child conceived during the previous union. In summary, in our work, the respondents become “at risk” for re-partnering once 9 months have passed since their separation. Additionally, we exclude the respondents who could not remember the timing of the separation from their ex-partner, when they began living together with the new partner, or had an improbable age at time of marriage to/separation from the ex-partner (e.g., one participant in Germany who was 10 years old at time of first marriage). As we do not focus on the legal standing of the second union (i.e., cohabitations vs. marriages), we also chose not to focus on the legal dissolution of the first union (i.e., we focus on the month and year of separation from ex-partner and do not consider the possible subsequent official divorce date).

For each of the reported partnerships, the respondents were also asked if they had any children with the ex-partner (answer categories, yes/no). If they did, they were then asked with whom these shared children stayed after the separation. The respondents could choose between nine options for children’s residence (e.g., 1 = “with me”, 2 = “with my ex-partner”, 3 = “with both of us on a time-shared basis”, 4 = “with relatives”). Due to the small ns in some categories, we construct a new variable where 0 = “no children from ex-partner”, 1 = “children stay with respondent”, 2 = “children stay with ex-partner”, 3 = “joint custody”, and 4 = “other”.

In addition to this information about the children from the ex-partner, we also have information about the birthdates of all biological children of the respondent. Based on these and the timing of the separation from the ex-partner, we calculate the age of the youngest child at the time of separation.

In our analyses, we control for the marriage duration of the union, which ended in divorce. This is calculated based on the self-reported timing of the marriage (or start of co-residence if the year of marriage was unavailable) and the timing of the separation. We also account for the current (time-varying) age of the respondents as a way to control for possible age effects on the likelihood to re-partner. Furthermore, we control for the respondents’ educational level by calculating their highest achieved educational rank with respect to the education level of the rest of the participants in that country. In other words, each respondent is assigned a proportional score recording the fraction of people in the sample at or below his/her highest educational level. In the cases when we perform analyses split by gender, we control for the respondent’s educational rank with respect to the rest of the males or females in the sample (i.e., gender specific educational rank). Finally, we control for the respondent’s separation cohort. This variable is constructed by subtracting the earliest year of separation within the sample from the respondent’s own year of separation and dividing the product by 10. In other words, the persons who separated longest ago have a value of 0 and a one unit increase on this continuous variable presents a 10-year more recent separation. The final samples are: 2,012 for Norway (57.7 % female), 1,121 for France (61.3 % female), 904 for Germany (60.0 % female), 796 for Romania (55.3 % female), and 1,930 for Russia (72.1 % female). As can be seen, women are overrepresented in all five samples.

5 Analytical Approach

We use discrete-time event-history analysis (Yamaguchi 1991) to examine gender differences in re-partnering after marital dissolution and the effect of children on re-partnering chances. Discrete-time models are a good approximation of continuous time models if the time intervals are not too large. For this work, we use years as intervals. Duration dependency was accounted for by introducing four interval dummies (for more information on the specific intervals, see Table 3). This approach is chosen as most flexible and because it does not require us to make assumptions about the shape of the hazard.

We estimate five models, of which three are estimated separately for men and women. All models are estimated with a logistic regression for the probability to start living together with a new partner in a given month, conditional on still being single the month before. To perform these analyses, we construct a person-month file that contains records for each individual for each month, starting with the tenth month after the separation and ending with the month in which the person started living with a new partner or, in case the person remained single the entire time, the month of interview. We corrected for the fact that the observations were not independent within unions by using the vce(cluster) option in Stata. We include the respondent’s current age (i.e., time-varying), educational rank, separation cohort, and duration of marriage. For all analyses, we display the estimated coefficients (and standard errors in parentheses) in the relevant tables. Our interpretation of the findings should always be understood in terms of marginal change, i.e., a change in the variable in question when all other covariates are kept constant.

6 Results

Table 2 provides detailed information about the characteristics of our five national samples. As can be seen in that table, in all countries over a third of the participants (over 40–45 %) lived with a new partner after their separation. The mean duration between separation and moving in with a new partner was similar for the five countries (the shortest was reported in France, M = 4.57 years, SD = 4.78 and the longest—in Germany, M = 5.03, SD = 5.60; difference not statistically significant). For all five countries, the vast majority of the respondents had children with their partner at the time of the marital separation (from 74.4 % in Romania to 85.4 % in Norway). It is important to note that these numbers include both children below and above the age of 18. With respect to the children’s residence after the marital separation, Table 2 shows that in all five countries, it was predominantly the female respondents who identified that the children stayed with them after the separation (the lowest prevalence of female respondents in the “the child stayed with the respondent” category was in Romania where 78.5 % of the respondents in this group were female).

We now turn our attention to the five event history models which we estimated. In Model 1, we focused on the effect of gender on the probability to re-partner (findings displayed in Table 3). Model 2 was identical to Model 1 but was estimated only for the respondents without children from the ex-partner (findings displayed in Table 4). If the effect of gender disappeared in this second analysis, we could deduce that children were the main contributor to the gender gap in re-partnering. As Table 3 shows and in line with previous empirical findings, women were significantly less likely to re-partner after a separation in all five countries. The largest gender gap was observed in Russia where the odds of moving in with someone were 42.2 % (calculated as (exp(b) − 1) * 100)) lower for women than for men. The smallest gender gap was observed in Germany where the chances were 22.9 % lower for women than for men. However, as can be seen in Table 4, when we performed the same analysis only for respondents without children from the ex-partner, we found that in almost all countries women no longer had lower chances to re-partner than men. The only exception was Norway where the gap decreased but women still had 36.1 % (as compared to the initial 39.9 %) lower chances than men to start living with a new partner after separation. The results from this second analysis suggest that in most countries, children are indeed an important contributor to the gender gap in re-partnering. In other words, despite institutional and cultural variation, we find the striking similarities across a number of European countries. In Norway, however, having children plays a smaller role in the previously documented gender gap. In the subsequent models, we investigate this child effect further.

In Model 3 we assessed the effect of having children on the chances to re-partner, separately for the two genders, ignoring for the moment where the children live. As can be seen in Table 5, having children decreased women’s chances to re-partner in almost all countries. The one exception was Germany where the effect of motherhood was negative but not significant (p = 0.11). An additional check (results available upon request) demonstrated that when we included the participants with less than 9 months between separation and moving in with a new partner, the effect of having children was significant and negative for German women but not for German men. This might imply that the effect of children on the chances of re-partnering is more time-specific in Germany than in the rest of the countries. We did not investigate this issue further as we had few cases where the re-partnering happened within 9 months of separation (44 men and 69 women).

For the other four countries, the differences between mothers’ and non-mothers’ likelihood to re-partner ranged from 19.6 % lower odds for mothers in Norway to 41.6 % lower odds for mothers in Romania. An additionally performed check indicated that the differences between the countries were not significant. For the men in most countries, the effects of children were also negative but not significant. In Norway, however, children decreased both women’s and men’s (by 22.5 %) chances to re-partner compared to respondents without children from their ex-partner. In sum, these findings are in line with the research literature that reports clear negative effects of parenthood for women and less clear, often absent effects for men (e.g., De Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Meggiolaro and Ongaro 2008; Poortman 2007). An additionally performed check demonstrated that the children effect on re-partnering differed significantly between men and women only in France (p < 0.10).

In Table 5, we can also see the effects that the control variables had on men’s and women’s likelihood to re-partner. As men’s educational rank increased, so did their chance to re-partner in Norway and France. However, women’s educational rank had no effect anywhere. In all countries, as the respondents aged, their chances to re-partner decreased significantly. For all countries, the effect of current age was stronger for women than for men and this difference between the genders was significant (p < 0.05). This finding indicated stronger age discrimination for women which can pose an additional challenge on the re-partnering market, next to the effect of children.

In Norway, we found evidence that women’s chances to re-partner have been improving in the past few decades. There, a 10-year more recent separation was associated with 13.5 % higher chances to re-partner for women. This effect was not found for the men which suggests that Norwegian women have been narrowing the gender gap in re-partnering chances. In Romania, however, we saw that the separation cohort had a negative effect on men’s chances to start living with a new partner, decreasing it by 15.3 %. The observed differences in the cohort effect between men and women were not significant for neither of the countries. Finally, marriage duration had a significant and positive effect on the likelihood to start living with a new partner for Norwegian and German men, as well as, for Russian women.

In Model 4 (Table 6) we focused on how children’s residence can affect the likelihood to re-partner, separately for men and women. Due to the fact that in some countries the n was too small for some of the residential categories, the categories with fewer than 40 cases for the specific country were dropped from the analysis. The only country for which we had enough cases in each residential category for both men and women was Norway. For the rest of the countries, we had sufficient cases to estimate the effect of having resident children both for men and women. For the other residential arrangements, we only estimated the effect if there were more than 40 cases in the category.

As can be seen in Table 6, women’s chances to re-partner were significantly and negatively affected by having a resident child in Norway, France, Romania, and Russia, whereas in Germany, the effect was still negative but not significant. This effect ranged from 44.4 % lower chances to re-partner for women with resident children compared to childless women in Romania to 19.8 % lower chances in Norway. Men’s chances to re-partner were affected in a similar fashion (fathers with resident children had lower chances to re-partner than non-fathers) yet the effect was only significant in Russia.

We could not estimate the effect of having non-resident children for the women in any country besides Norway, where this effect was positive but not significant. Interestingly, men’s chances to re-partner were not significantly affected by having children who stayed with their ex-partners anywhere besides in Norway, where they were in fact decreased (by 24.3 %). In other words, we did not find support for the possible “good-father effect” which has been reported in some earlier studies (e.g., Stewart et al. 2003). Furthermore, we demonstrated that there was a negative effect of parenthood on men’s re-partnering chances (which held primarily when the child was resident in the man’s household). An additionally performed check demonstrated that the difference between the categories “children stayed with respondent” and “children stayed with ex-partner” was significant for Norwegian women and for Romanian and Russian men (p < .10) which might imply that the effect of parenthood (at least in these cases) was likely an issue of residence.

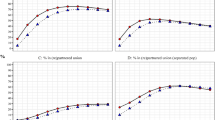

In Model 5 (Table 7), we investigated the effect of the (youngest) child’s age at separation, separately for men and women. In this analysis, three variables related to the age of the youngest child were utilized: a time-varying variable for the current age of the youngest child, a time-varying dummy denoting whether the child was 18 or older in that year (0 = younger than 18, 1 = 18 or older), and an interaction between these two variables. This approach allowed us to assess whether the effect of the youngest child’s age changed once that child reached the age of majority. As we did not have time-varying information on the child’s residence, the age of majority can also be seen as a proxy for the child leaving the parental home. As can be seen in Table 7, when the child’s age mattered, it mostly did so for the women and before the child turned 18. We see that in Norway, France, and Russia, for each year that the youngest child aged, women’s chances to re-partner increased by 5.6, 8.4, and 7.6 %, respectively, but that was only true before the child turned 18. When the youngest child turned 18, women’s chances to start living with a new partner improved substantially in all of these counties. We also see this significant bump in the re-partnering odds for Norwegian men (after which their chances continuously decrease). After this turning point, however, we see that the youngest child’s age was no longer important for the chances to re-partner (i.e., the sum of the main effect of the child’s current age and the interaction term is about zero in all three countries). For German women, we found that as the youngest child aged, their likelihood to re-partner continuously improved. We found no effect of child’s age in Romania.

7 Discussion

The main aim of this work was to re-examine the effect children can have on the chances to re-partner after a marital dissolution and to expand on previous findings by presenting comparable results for five European countries which differ substantially in their institutional and cultural contexts (Norway, France, Germany, Romania, and the Russian Federation). In addition to testing the possible parenthood effect, we also considered how the custodial arrangements and the child’s age could affect the likelihood to start living with a new partner for men and women. Several noteworthy findings emerged from our work. In the subsequent sections, we will first address the findings with respect to the effect of children on re-partnering and will then discuss the observed country differences and similarities.

Foremost, in line with our expectations and ample evidence from earlier works from Europe and North America (e.g., Coleman et al. 2000; de Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Meggiolaro and Ongaro 2008; Skew et al. 2009; Wu and Schimmele 2005), we found that women were less likely to re-partner after marital dissolution than men. Interestingly, however, our findings from the analyses for childless individuals did not provide such overwhelming evidence for the existence of a gender gap in re-partnering. We found that in all countries except Norway women without children were not less likely to re-partner than men without children. In other words, children are indeed an important contributor to the documented gender gap in re-partnering. We consider the mechanisms underlying this finding in the subsequent sections of the discussion.

Our results with respect to the possible parenthood effects on re-partnering demonstrated that mothers were almost universally less likely to move in with a new partner than non-mothers in all countries. The effect was similar for men (and German women) but their likelihood to re-partner was not significantly affected by parenthood in almost any of the countries. The one exception was Norway where the impact of parenthood was also negative and significant for men. A couple of points can be made here with respect to these findings. It has been suggested that people’s initiation of a new union can be guided by several factors—the need to re-partner, the attractiveness to potential partners, and the opportunity to meet and mate with such partners (Becker 1993; de Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Goldscheider and Waite 1986; Oppenheimer 1988). In our work, we do not find support for the positive effect which the need argument can imply. Although women’s economic situation in particular has been shown to be adversely influenced by marital dissolution (Poortman 2000), an effect possibly offset by remarriage (Dewilde and Uunk 2008), we did not find that women with children were more likely to re-partner than women without children. In fact, women with children had even lower chances to re-partner than women without children. Therefore, it is also important to note that our findings could be pointing to the fact that separated mothers already have their parenthood need satisfied and thus, might be less inclined to enter a new union.

The other important point to address here relates to the previously reported mixed findings about the effect of parenthood on men’s likelihood to re-partner. Whereas some researchers have established a positive effect of parenthood on men’s likelihood to re-partner (Bernhardt and Goldscheider 2002; Stewart et al. 2003; Wu and Schimmele 2005), others have either not found this effect or have found a negative effect (De Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Poortman 2007). Our results are in line with the latter group of researchers. In our work, we saw that men’s chances to re-partner were not increased by their fatherhood status and were even decreased by it in Norway. Although we did not directly test the mechanisms underlying the link between parenthood and re-partnering, our subsequent findings with respect to the custodial arrangements and child’s age shed some light on the factors which could account for the established negative effect.

In almost all countries, we found that coresidential children decreased women’s chances to enter a new co-residential union. The general trend was similar for men with the effect being significant in Russia. In other words, it appeared that when we considered fathers and mothers in similar custodial situations, the differences between the genders in re-partnering were not as striking as when we simply considered their parenthood status. In fact, mother’s chances to re-partner were not lower than non-mothers’ when the children stayed with the ex-partner. Here, the story was somewhat different for fathers. When the children stayed with the ex-partner, fathers had a lower likelihood to enter a new co-residential union than non-fathers.

Our interpretation of these findings can likely be found in the previously outlined “opportunities to re-partner” and “attractiveness to potential partners” arguments (Becker 1993; de Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Goldscheider and Waite 1986; Oppenheimer 1988). Coresidential children are likely to reduce the time and energy that custodial parents can spend on socializing with potential new partners (Koo et al. 1984), irrespective of the parent’s gender. Furthermore, children can affect parents’ attractiveness on the re-partnering market. On the one hand side, a coresidential child means that the new partner would have to make an investment in forging a relationship with a non-biological child which can be problematic (Stewart et al. 2003). On the other hand side, the residence of a child can also serve as a signal to potential new partners. When the child stays primarily with the ex-partner it can decrease men’s chances to re-partner because of the possible indication that the father is not truly involved in his children’s lives. Yet, this conclusion has to be treated with caution as it is based on the findings for only one country (i.e., Norway). Though we speculate about the mechanism which might underlie the documented associations, more detailed prospective data on people’s needs, preferences, and opportunities are necessary in order to assess what precisely is driving these relationships.

Our final noteworthy finding with respect to the child effect on re-partnering concerns the significance of the child’s age. Our results indicated that as the child aged, people’s chances to move in with a new partner increased. This is in line with previous findings that it is young children that most strongly affect the parents’ re-partnering chances (Skew et al. 2009). This effect, however, was mostly true before the child reached the age of majority after which, it no longer mattered for the parents’ chances to re-partner. We interpret this as a sign that as children age, their dependence on the parents decreases and thus, parents have more opportunities to find new partners (e.g., by for example, increasing their participation in the labor market).

In our work, we were able to present more or less comparable analyses from five distinct in their institutional contexts European countries. Yet, the story which emerged was dominated primarily by similarities in the effects rather than differences. In most countries, children were an important contributor to the gender gap in re-partnering; in most cases, mothers were less likely to re-partner than non-mothers and the trend was similar but not significant for fathers (with the exception of Norway); men and women with coresidential children had lower likelihood to begin co-residing with a new partner; and as the child aged, parents were more likely to re-partner. The negative effect of children on mothers’ likelihood to re-partner appeared to be strongest in Romania (though it is important to keep in mind here, that the differences between the countries were not statistically significant). As we elaborated in the introduction, Romania is a country with particularly low divorce rates (Kalmijn 2007) which could be associated with a certain stigmatization of divorce and thus, lower attractiveness of divorced parents to potential new partners. Additionally, Romania has comparatively low quality and availability of formal childcare facilities (European Commission 2009) and as children stay primarily with the mother after the dissolution of the marital union, Romanian women might find their opportunities to socialize with new partners particularly restricted. These interpretations of our findings, however, remain speculative in nature.

The one country which was somewhat of an exception was Norway. For Norway, we found that there was still a gender gap in re-partnering even for childless persons. Also, both mothers and fathers had a lower likelihood to re-partner than non-parents. Given the egalitarian gender roles in Norway, it is especially striking that childless women are less likely to re-partner than childless men. Although preferences may play a role here, we do not think it is likely that in Norway, divorced women have a stronger preference for singlehood than divorced men. Unfortunately, we do not have the prospective information necessary to assess the participants’ preferences and how these might be shaping the effects which we see.

Despite the interesting questions which our work raises, there are certain limitations that need to be considered when presenting our findings. Foremost, as we have mentioned a number of times, though our work is based on previously outlined theoretical mechanisms (Becker 1993; Goldscheider and Waite 1986; Oppenheimer 1988), we are unable to test these assumptions directly. Much more detailed and most importantly, prospective data are needed in order to assess how certain individual considerations (e.g., preferences, needs) might be shaping people’s decisions and behaviors on the re-partnering market. Such data will also enable future researchers to evaluate whether parents’ lower likelihood of re-partnering is in fact due to restricted opportunities and reduced attractiveness on the re-partnering market or to an actual personal choice not to enter another co-residential union. Secondly, we aimed at showing how universal the effect of children on re-partnering is across different institutional contexts. Though our findings provide an impression of how similar these results are across the five countries, we do not test the effects of distinct macro-level variables. A multilevel approach, with direct macro-level indicators would, of course, be preferable yet such method requires a much higher number of countries. Another shortcoming of our work is that our conclusions about certain child residential arrangements (e.g., with ex-partner for women) were based only on the findings from Norway. For the rest of the countries, the vast majority of the children stayed with their mothers which made the use of the other residential categories difficult. It is also important to mention that we operationalized “re-partnering” as moving in with a new partner. In other words, it is entirely possible that the respondents had relationships after their first marital union which however, were not co-residential (e.g., a “living-apart-together” arrangement). Our choice was determined by the fact that the information collected with respect to the respondents’ partnership histories was limited to previous unions in which the partners co-resided for at least 3 months. This particularity of the data should be kept in mind when interpreting our findings with respect to the timing of subsequent partnerships. Finally, we would like to mention the possible interesting time-dependence of the child effect which we might have found indications of in the German sample. Though we saw that women were not less likely to re-partner than men when only the childless respondents were examined, we found a negative but insignificant effect of having children for both men and women in Germany. As we elaborated in the results section, we found the expected effect for German women when we also examined the chances of early re-partnering (i.e., within the first 9 months after separation). Though we did not have a sufficient number of cases to focus on this issue further, subsequent works should be aware of the possibility that at least in some countries, having children might decrease the chances to re-partner quickly but that effect is attenuated with time.

In our work, we did not explicitly address the issue of potential bias in our findings due to unobserved heterogeneity in the sample at risk for re-partnering. In order to assess the issue of possible individual-level unobserved heterogeneity, uncorrelated to the covariates of interest, we also estimated our models after including person-level random effects (shared frailties within respondents) and found our findings to be robust (results available on request). In other words, we found no evidence that a certain unobserved individual-level characteristic was biasing our finding with respect to the child effect, for example. However, we did not assess whether decisions about exiting a marital union as a parent and subsequently entering a new co-residential union might be jointly determined by unobserved characteristics. As has been previously noted, a challenge to determining the significance of previous events for the timing of subsequent similar or related events is the potential for selection bias (Steele et al. 2006). For example, one can speculate that it would be the parents with higher socio-economic resources that are in fact, more likely to end their first marriage. Previous works have found that especially in societies where divorce is less common, it might take higher resources to dissolve a marriage (for an overview, see Lyngstad and Jalovaara 2010). Following our line of reasoning about need, attractiveness, and opportunities, these would then also be the participants who might withhold from entering a new co-residential union as they do not have the financial need to do so. This argumentation, however, remains rather speculative. Additionally, it is interesting to note that works which have modeled the effects of previous partnership experiences on subsequent transitions have found these effects to be only slightly understated in single-process as compared to the multiprocess models (Steele et al. 2006). As our data do not provide multiple, time-varying indicators of socio-economic status or other theoretically relevant individual-level indicators, this multi-process modeling of exiting the first union (as a parent or not) and entering a new co-residential union remains a task for future research which can use our findings as a starting point.

Despite the shortcomings of this work, we have now provided an impression of how important children are in the discussion of men’s and women’s likelihood to re-partner in different European countries. As we have now seen, certain effects are rather universal, across contexts and more importantly, across genders. It remains to future work to investigate not only the precise mechanisms which underlie these associations but also, how specific macro-level factors can affect the relationships which we found.

References

Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 650–666.

Becker, G. S. (1993). A treatise on the family. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Bernhardt, E., & Goldscheider, F. (2002). Children and union formation in Sweden. European Sociological Review, 18(3), 289–299.

Bumpass, L., Sweet, J., & Castro Martin, T. (1990). Changing patterns of remarriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52(3), 747–756.

Cherlin, A. J., & Furstenberg, F. F. (1994). Stepfamilies in the United States: A reconsideration. Annual Review of Sociology, 20, 359–381.

Coleman, M., Ganong, L., & Fine, M. (2000). Reinvestigating remarriage: Another decade of progress. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1288–1307.

De Graaf, P. M., & Kalmijn, M. (2003). Alternative routes in the remarriage market: Competing-risk analyses of union formation after divorce. Social Forces, 81(4), 1459–1498.

Dewilde, C., & Uunk, W. (2008). Remarriage as a way to overcome the financial consequences of divorce—A test of the economic need hypothesis for European women. European Sociological Review, 24(3), 393–407.

European Commission. (2009). The provision of childcare services: A comparative review of 30 European countries. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities

Eurostat. (2012). At-risk-of-poverty rate by poverty threshold and household type. Retrieved from http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_li03&lang=en.

Goldscheider, F. K., & Waite, L. J. (1986). Sex-differences in the entry into marriage. American Journal of Sociology, 92(1), 91–109.

Kalmijn, M. (2007). Explaining cross-national differences in marriage, cohabitation, and divorce in Europe, 1990–2000. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography, 61(3), 243–263.

Kiernan, K. (2001). The rise of cohabitation and childbearing outside marriage in Western Europe. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 15(1), 1–21.

Koo, H. P., Suchindran, C. M., & Griffith, J. D. (1984). The effects of children on divorce and re-marriage: A multivariate analysis of life table probabilities. Population studies: A Journal of Demography, 38(3), 451–471.

Lampard, R., & Peggs, K. (1999). Repartnering: The relevance of parenthood and gender to cohabitation and remarriage among the formerly married. The British Journal of Sociology, 50(3), 443–465.

Lokshin, M., & Popkin, B. M. (1999). The emerging underclass in the Russian Federation: Income dynamics, 1992–1996. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 47(4), 803–829.

Lyngstad, T. H., & Jalovaara, M. (2010). A review of the antecedents of union dissolution. Demographic Research, 23, 257–291.

Meggiolaro, S., & Ongaro, F. (2008). Repartnering after marital dissolution: Does context play a role? Demographic Research, 19, 1913–1933.

Mills, M. (2004). Stability and change: The structuration of partnership histories in Canada, the Netherlands, and the Russian Federation. European Journal of Population, 20(2), 141–175.

Munch, A., McPherson, J. M., & SmithLovin, L. (1997). Gender, children, and social contact: The effects of childrearing for men and women. American Sociological Review, 62(4), 509–520.

OECD. (2012a). Enrolment in childcare and pre-schools. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/els/family/oecdfamilydatabase.htm.

OECD. (2012b). Informal childcare arrangements. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/els/family/oecdfamilydatabase.htm.

Ongaro, F., Mazzuco, S., & Meggiolaro, S. (2009). Economic consequences of union dissolution in Italy: Findings from the European community household panel. European Journal of Population, 25(1), 45–65.

Oppenheimer, V. K. (1988). A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology, 94(3), 563–591.

Poortman, A. R. (2000). Sex differences in the economic consequences of separation: A panel study of the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 16(4), 367–383.

Poortman, A. R. (2007). The first cut is the deepest? The role of the relationship career for union formation. European Sociological Review, 23(5), 585–598.

Rieck, D. (2006). Transition to second birth—The case of Russia. MPIDR working paper WP 2006-036. Retrieved from http://www.demogr.mpg.de/papers/working/wp-2006-036.pdf.

Sederlof, H. S. A. (2000). Russia: Note on social protection. Retrieved from http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/seminar/2000/invest/pdf/sederlof.pdf.

Skew, A. J., Evans, A., & Gray, E. E. (2009). Re-partnering in Australia and the UK: The impact of children and relationship histories. 26th International Population Conference. Marrakech, Morocco. Retrieved from http://iussp2009.princeton.edu/abstracts/91901.

Soons, J. P. M., & Kalmijn, M. (2009). Is marriage more than cohabitation? Well-being differences in 30 European countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(5), 1141–1157.

South, S. J. (1991). Sociodemographic differentials in mate selection preferences. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(4), 928–940.

Steele, F., Kallis, C., & Joshi, H. (2006). The formation and outcomes of cohabiting and marital partnerships in early adulthood: The role of previous partnership experience. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 169(4), 757–779.

Stewart, S. D., Manning, W. D., & Smock, P. J. (2003). Union formation among men in the U.S.: Does having prior children matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(1), 90–104.

Sweeney, M. M. (2002). Remarriage and the nature of divorce: Does it matter which spouse chose to leave? Journal of Family Issues, 23, 410–440.

Sweeney, M. M. (2010). Remarriage and stepfamilies: Strategic sites for family scholarship in the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 667–684.

Teachman, J. D., & Heckert, A. (1985). The impact of age and children on remarriage: Further evidence. Journal of Family Issues, 6(2), 185–203.

United Nations. (2005). Generations and Gender Programme: Survey Instruments. New York/Geneva: United Nations.

Vikat, A., Spéder, Z., Beets, G., Billari, F., Buehler, C., Desesquelles, A., et al. (2007). Generations and gender survey (GGS): Towards a better understanding of relationships and processes in the life course. Demographic Research, 17, 389–440.

Wang, H., & Amato, P. R. (2000). Predictors of divorce adjustment: Stressors, resources, and definitions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(3), 655–668.

Wu, Z., & Schimmele, C. M. (2005). Repartnering after first union disruption. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(1), 27–36.

Yamaguchi, K. (1991). Event history analysis. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ivanova, K., Kalmijn, M. & Uunk, W. The Effect of Children on Men’s and Women’s Chances of Re-partnering in a European Context. Eur J Population 29, 417–444 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-013-9294-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-013-9294-5