Abstract

This study estimated the direct and indirect contributions of mentorship and institutional support (IS) to academic staff's research productivity (RP) at a public university in Cross River State. Two mediator variables—collaboration and institutional culture (IC), were introduced to determine their roles in the nexus between the predictors and the criterion variables. The quantitative research method was adopted following the correlational research design. “Career Empowerment and Research Productivity Questionnaire (CERPQ)” was used for data collection after validation by experts and reliability test. Three hundred twenty-seven copies of the CERPQ were administered, but 303 were retrieved. Mediation-based analysis was performed using structural equation modelling following the research questions and hypotheses. Amongst others, findings revealed that mentorship had a non-significant negative contribution to the RP of academic staff; mentorship only promoted RP among academic staff when it was followed by positive IC and collaboration. IS had a non-significant positive contribution to the RP of academic staff. The joint mediation of collaboration and IC was significant in the nexus between mentorship and RP and between IS and RP of academic staff in the public university. Collaboration was the most important factor directly associated with the RP of academic staff and also partially mediated the contributions of other variables (such as mentorship and IS) to the RP of academic staff. The results of this study can be useful for universities seeking to enhance the research productivity of their academic staff. The study highlights the importance of considering multiple factors that may influence research productivity and suggests that institutions should prioritise fostering a supportive and collaborative environment for academic staff to maximise their research productivity. The study can also inform the development of mentorship programmes and the creation of institutional policies that support and promote research productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Publication output is critical to academic staff and institutions in general. It is generally known that peer-reviewed publications are the primary unit by which faculties and educational programmes are judged. It enables academic staff to share insight, demonstrate scholarship, recognise creative thinking, and develop a reputation and expertise in a discipline. Publication output partly determines local and international recognition and respect for academic staff and institutions. Universities now also use the number of publications to an individual's credit to measure competency (Owan & Owan, 2021). Publication output is very significant in the lives of academic staff; hence, their promotions are almost entirely dependent on it (Bassey et al., 2007). The heavy reliance on publications as the basis for research assessment has put immense pressure on academic staff to publish or perish (Glick, 2016; Lambovska & Todorova, 2021). The phrase “publish or perish” is a harsh reality for those who teach at universities (Rawat & Meena, 2014). Thus, researchers are considered productive by the number of research papers published.

Many researchers define research productivity (RP) by equating it with the “quantity” of published works academics have accumulated, or what is commonly termed “publication counts” (Akbaritabar et al., 2018; Butler, 2003). Similarly, a researcher is considered productive based on the number of books or articles translated from a foreign to a local/native language, the number of written reports for consultancy work, and the number of research involvement or creative works developed (Bai, 2010; Eam, 2015). Several other scholars (e.g. Agarwal et al., 2016; Carpenter et al., 2014; Okon et al., 2022) have considered the quality aspect of academics' RP by using bibliometric methods (such as citation counts, citation rates, h-index and others) to determine the scholarly impact of a specific author or publication.

Citation index and h-index measure RP by precisely capturing the average number of times a scholar's published works and the research works published by a university, country, region or continent are cited internationally (Kpolovie & Dorgu, 2019; Owan & Owan, 2021). The two indices demonstrate how much each faculty member contributes to the totality of human knowledge and reveal those whose research has distinctly stood out by being frequently picked up and built upon by other scholars. Today, scholars' reputations and research excellence are determined based on the extent to which their h-index and citation counts exceed those of other scholars in the same discipline. Therefore, the more the number of scholars with an unprecedented h-index and citation counts in a university, the more prestigious the institution is publicly perceived (Kpolovie, 2014) and the higher the research income it attracts. Going by these, we can say that the productivity of academic staff is currently a “game of numbers”. It is a game of numbers because everything revolves around metrics that are not without limitations.

The drawbacks to using metrics (such as citations, impact factors of journals, altmetrics and h-index) for research assessment include bias towards older work, English-language journals, discipline-specific variations, self-citation bias, lack of context, and bias towards quantity over quality. Scholars have discovered that citations and h-index can be influenced by publication venue and language biases (Cheek et al., 2006; Owan & Owan, 2021; Urlings et al., 2021). For example, researchers in fields that publish in high-impact factor journals or in English may receive more citations, making it difficult to compare researchers from different disciplines or countries accurately. Additionally, metrics do not consider the quality or relevance of the citations received (Ding et al., 2020; Dinis-Oliveira, 2019). A researcher can receive many citations for low-quality or irrelevant work, which can skew h-index, journal impact factors and other metrics. Furthermore, both citation counts and the h-index can be manipulated through self-citation, citation cartel, and other unethical practices, which can artificially inflate their scores (Loan et al., 2022; Oravec, 2019; van Bevern et al., 2020).

To address the weaknesses associated with research metrics for assessment, some scholars have advocated that for a researcher to be considered productive, he must possess a solid research orientation upon starting a career in the university, have the highest terminal degree, and demonstrate early publication habits (Horta et al., 2016; Kpolovie & Onoshagbegbe, 2017; Ndege et al., 2011). He must also maintain a record of previous publication activity, communication with colleagues, subscriptions to many journals, and sufficient time allocation for research (Finkelstein in Oyeyemi et al., 2019). Other factors contributing to researchers' productivity include affiliation to a university or research institution, assigning ample time for faculty to conduct research and using an assertive participatory management approach (Bland et al., 2005). Based on the measures of RP, preliminary assessments of the research productivity indicators of most academic staff in Nigeria tend to give a weak impression of their reputation. While it is possible to see many scholars elsewhere with h-indexes higher than 300, some scholars in Cross River State are still struggling to reach an h-index of 5.

Again, most academic staff have yet to win a grant even after attaining professorial status. Some junior and senior academic staff often struggle to publish in highly rated peer-reviewed journals, especially those published by well-respected publishers. Even though RP is an important requirement for research assessment, there has been a low turn-up of lecturers participating in writing and publishing research works, especially in Nigerian universities. This trend is also often observed during appraisal for promotion, where some academics are denied promotion for not meeting the minimum publication requirements expected. Again, the extent to which many scholars rely on what may be termed the “abeg put my name” syndrome in climbing their career trajectory is high (Abimbola et al., 2021; Owan & Owan, 2021).

“Abeg put my name”, a phrase in pidgin English, which translates to “please add my name”, refers to a situation or system where lazy academics/individuals plead with their hardworking or productive colleagues to enlist or include them as coauthors in research papers they did not make any intellectual contribution to their creation. It is commonly associated with academics seeking to avoid perishing due to their inability or unwillingness to publish (Owan & Asuquo, 2022). Consequently, many early career academics and junior faculty members tend to be seen without the zeal to engage in active research initiatives due to their perceived reliance on other scholars for subsistence. This affects their research capacity in initiating a research idea, collecting and analysing data and preparing research reports for publication. This trend also reduces the number of scholars in universities who can carry out independent research, especially if more seasoned scholars retire from the system.

Previous studies have revealed various factors affecting the RP of academics or explained why academics do not write for publication. These include the overall non-satisfaction levels of academic staff with the job (Friday & Okeke, 2020; Jameel & Ahmad, 2020; Lambovska & Todorova, 2021), socialisation of faculty staff members in a research climate (Nguyen, 2022) and university mission vis-à-vis academic research (Ghabban et al., 2019). Other factors are supervision and institutional prestige (Shen & Jiang, 2021), demographic variables (age, gender, experience, academic rank) (Anyaogu & Iyabo, 2014; Farooqi et al., 2019; Hedjazi & Behravan, 2011; Okonedo et al., 2015; Susarla et al., 2015), time allocation (Barber et al., 2021; Milem et al., 2000), teaching load (Maharjan et al., 2022; Nur-tegin et al., 2020), research competency (Prado, 2019), and interest/autonomous motivation in doing research (Masinde & Coetzee, 2021; Stupnisky et al., 2022). Furthermore, institutional factors that affect RP include poor working environment (Adetayo et al., 2023; Li & Zhang, 2022; Vuong et al., 2019), extra administrative duties, institutional support (Uwizeye et al., 2022), institutional culture and inadequate mentoring (Okon et al., 2022), among others.

Although the factors mentioned above have been identified as important predictors of RP, few studies in developing nations have investigated their potency among academics. Undeniably, knowledge derived from a given context may be extended and used in another. However, care must be exercised to ensure that both contexts are culturally, economically, socially and politically similar. Given that most studies on RP are foreign to Africa, particularly Nigeria, there is a need for further studies in Africa to be conducted. This will address the current population gap in the literature and promote the applicability of research results for problem-solving. Based on this argument, the present study was conceived to determine whether mentorship and institutional support (IS) can contribute to the RP of academic staff and to determine whether collaboration and institutional culture (IC) can mediate the relationship.

1.1 Mentorship

Mentoring affords the transfer of skills that protégés can apply in diverse professional circumstances. It promotes productive knowledge, clarity of goals and roles, career growth, job satisfaction and success, salary increases and promotions (Okurame & Balogun in Undiyaundeye & Basake, 2017). Previous studies on mentorship and research productivity (RP) reveal a significant positive correlation between the two variables (Abugre & Kpinpuo, 2017; Arkaifie & Owusu-Acheampong, 2019). This result implies that improvement in the mentorship practices within an institution is connected to increased productivity. However, these studies did not explain the role that other extraneous or confounding variables play in the nexus between the two variables. Many variables often co-occur, and if some are considered over others, it could skew the results, leading to misleading conclusions. The present study bridged this gap by introducing two suspected confounding variables — IC and collaboration to the relationship between mentorship and RP.

Another study by Carmel and Paul (2015) indicated that mentees were positively impacted by opportunities related to career advancement, expanded thinking, scholarly confidence, facilitation of a collaborative culture, and the importance of goal setting in academia. However, the study did not consider institutional variables' role in the established mentor–mentee relationship. This leaves us wondering whether to count on mentorship as a factor accounting for most of a researcher's productivity. The present study addressed this gap by enlisting other variables, such as institutional culture, support and collaboration, to determine a series of interconnections among them. Research conducted by Arkaifie and Owusu-Acheampong (2019) revealed that mentoring programmes positively affected mentees' work and personal lives. The cited study's focus was on mentoring programmes at the institutional level. In contrast, the present study sought to determine the contribution of mentorship at the personal level among senior faculty in enriching or otherwise the productivity of mentees (who, in most cases, are junior academics).

In educational psychology, Okon et al. (2022) recently found important linkages between two mentorship practices (cloning and apprenticeship) and the RP of early career researchers in South–South Nigeria. However, Chitsamatanga et al. (2018) discovered that mentoring is theoretically in universities but practically surrounded by grey areas. These grey areas include a general lack of interest and knowledge, academic perceptions of mentoring and networking in universities, and a shortage of role models. These issues promoted disintegration, inaccessibility and egoism within universities. Similarly, a study identified a problem associated with mentorship in universities by revealing that it is useful most often to the senior partner in the union (Okurame in Undiyaundeye & Basake, 2017). However, it remains unclear whether such benefit by the mentor occurs in the short or long term. It is also essential to understand when mentees will likely benefit from the relationship, as documented by Okurame. Thus, further research is still needed in this area for verification and comparative purposes.

1.2 Institutional support

Institutional support (IS) refers to active organisational encouragement through policies, regulations, and monetary/non-monetary assistance offered to employees that propel them to perform their responsibilities effectively. Any organisation, including higher learning institutions, that want to earn employees' commitment must be ready to give adequate support (Owan et al., 2022). IS in higher education can be offered through conference sponsorship, research grant provisions, publication, and technical and pedagogical support (Al-Enazi, 2016). It has been proven empirically by Salau et al. (2018) that meaningful work and growth opportunities are predictive factors for maximising productivity in institutions. However, the study was not explicitly focused on workers' research productivity (RP), and the institutions studied were non-academic. Therefore, a study on IS and academic staff RP is necessary among academic staff populations since they are among the mainstream producers of knowledge.

Research conducted by Henry et al. (2020) revealed that age cohort, the highest qualification, cluster and track emphasis are variables that significantly determine the RP of academic staff. The cited study concluded that personal, environmental and behavioural factors influence RP among academic staff. Nevertheless, none of the enlisted variables was considered concerning other confounding variables that could mediate the association. Another study concluded that even though organisational factors are significant antecedents of university academic staff RP, some of its elements (such as technological progress and possession of computer skills) were more significant antecedents than others (Hiire et al., 2020). This implies that to boost the RP of the academic staff, university managers need to place proportionate emphasis on these factors if they are to create an enabling research environment in their institutions. Some earlier studies revealed that organisational factors and funding could positively influence RP in universities and colleges (Kyaligonza et al., 2015; Musiige & Maassen, 2015).

This scenario was not significantly different from what Oyekan (2014) reported in his study that resource situation factors such as physical, human and material resources have significant positive relationships with RP among academics. A recent study showed that institutional factors (availability of research funding, level of institutional networking, and the degree of research collaborations) and individual factors (personal motivation, academic qualifications, and research self-efficacy) are associated with RP in tertiary institutions in Africa (Uwizeye et al., 2022). Furthermore, Falola et al. (2020) showed that research, pedagogical and technical support are predictors of faculty responsiveness to quality research production, knowledge sharing, and administrative efficiency. This suggests that increased support to academics from their institutions might be associated with increased productivity from research engagements. Since several meaningful connections have been established in the literature on IS and RP, the factors that can mediate the link between IS and RP remain to be seen. None of the previous works has used the mediation approach to determine the roles played by confounding variables in the relationship between IS and RP. It is essential to understand all the variables contributing to a researcher's productivity and their various roles amid other predictors. This study attempts to understand the conditions that certain IS variables are likely to contribute (significantly) or otherwise to the RP of academic staff through the mediation of collaboration and institutional culture (IC).

Understanding the factors that mediate the link between IS and research productivity (RP) can provide valuable insights for academic institutions and policymakers. By identifying the specific ways in which IS affects RP, institutions can better allocate resources and create policies that support the research efforts of their faculty. Also, the use of mediation analysis in the study is a unique and important approach. This study’s use of this method can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between these variables. Collaboration is a key aspect of many research projects, and understanding how IS affects collaboration can provide insight into how institutions can support the research efforts of their faculty. Similarly, IC can shape the overall research environment of an institution and understanding how it affects RP can provide insight into how institutions can create a supportive culture for research.

1.3 Collaboration

The advancement of scientific knowledge demands that researchers be equipped with the appropriate competencies, beginning from learning about the problem under study (which permits the individual to carry out original and relevant studies), up to the necessary competencies in methodologies and reporting the findings for publication. A single scientist does not possess all the necessary competencies to achieve scientific advancement in an era characterised by complex problems that transcend one discipline for effective solutions (Abramo et al., 2017). Collaborating with research teams across the affected disciplines is a good and practical strategy to overcome such problems. This is possible since collaboration would involve scientists with complementary skills and abilities. Moreover, collaboration facilitates the generation and selection of original ideas due to the synergies obtained from scientists with complementary backgrounds or even from different disciplines (Abramo et al., 2017; Rigby & Edler, 2005). Multiple authors' involvement also permits more efficient use of time. It limits the need to resort to external advisors, for example, for third-party checking of research processes and outcomes (Barnett et al. cited in Abramo et al., 2017).

There is a dearth of empirical studies on collaboration and research productivity (RP). However, one related study by Alaa and Ahmad (2020) indicated that funds, collaboration, ICT and job satisfaction positively impacted RP. It was further revealed that funding has the highest impact on RP. This study implies that the management of universities should pay greater attention to research funding opportunities, reward collaboration among researchers, promote ICT integration and improve job satisfaction to boost the RP of the academic staff. However, there is a lack of empirical literature on the topic. Nevertheless, the current study builds on the findings of Alaa and Ahmad (2020) by using collaboration as a mediator variable between mentorship, IS, and RP. This approach can provide a more comprehensive understanding of how collaboration affects RP and identify specific ways collaboration can boost RP. Additionally, the study can provide valuable insights for university management. For instance, Alaa and Ahmad (2020) indicated that funding has the highest impact on RP; however, this study aims to investigate how other variables, such as mentorship and IS, can also boost RP through collaboration. By understanding how these variables interact, university management can better allocate resources and create policies that support the research efforts of their faculty.

1.4 Institutional culture

Several studies have investigated the organisational factors that significantly relate to the research productivity of university academics, and they have all emerged with diverse and, at times, contradictory findings (e.g. Kyaligonza, 2015; Mugimu et al., 2013; Musiige & Maassen, 2015; Oyekan, 2014). For instance, Bland et al. (2005) tested the ability of the individual, institutional and leadership variables to influence faculty research productivity using data from the University of Minnesota Medical School. Regression results revealed that faculty productivity was influenced more by institutional than personal characteristics. Hadjinicola and Soteriou (2006), on the other hand, investigated factors that promote the research productivity of researchers in US Business schools. Their findings revealed that the availability of a research centre, funding from external sources for research purposes and better library facilities are factors associated with increased RP in U.S. Business schools. In another study, Hedjazi and Behravan (2011) discovered that institutional characteristics, such as a network of communication with colleagues, facilities, corporate management, and transparent research objectives, were significant predictors of the agricultural faculty members' research productivity. Also, Kyaligonza (2015) also revealed that institutional factors had a moderate effect on the research productivity of the academic staff in the universities studied.

In another development, Ayesha et al. (2021) found that different institutional elements such as research procedure of departments, job and compensation, assets and helping materials have a low, however, positive correlation with research profitability among teaching personnel. Furthermore, Jaime (2020) established that every unit increase in holding high-performance expectations and providing intellectual stimulation could produce a 0.36 and 0.67 growth in faculty members' research efficiency. Factors such as “nature of school leadership”, “modelling behaviour”, “providing individual support”, and “strengthening school culture” likewise contributed to faculty members' research production but not to a significant level.

Based on a literature review, there is a lack of consistency in the findings of previous studies on the relationship between institutional culture (IC) and the research productivity of academics. Some studies have found that IC significantly impacted RP, while others found that personal characteristics had a greater influence. Thus, there is a lack of consensus among previous studies. Furthermore, research on the specific role of IC as a mediator in the relationship between mentorship and RP and also between IS and RP is lacking. Additionally, a lack of studies specifically focused on public universities in Nigeria makes the current study important to fill this gap in the literature. Furthermore, studies also found that different institutional variables such as research procedures of departments, compensation, assets and useful materials have a low yet positive correlation with research productivity (Ayesha et al., 2021), highlighting the need for further research in this area.

1.5 Theoretical framework

This study was grounded in the Social Learning Theory (Bandura, 1977). According to the Social Learning Theory (SLT), people can learn by observing and imitating the behaviour of others. This theory suggests that individuals can learn through direct experiences, environmental influences, and observing the behaviour of others (Bandura, 1986). The theory also highlights the importance of cognitive, behavioural, and environmental factors in shaping behaviour (Bandura, 1999). The theory is based on the following assumptions: (1) people can learn new behaviours and attitudes through observation and imitation of others; (2) learning can occur through direct experiences and environmental influences; (3) cognitive, behavioural, and environmental factors interact to influence behaviour; and (4) people can learn by watching and then rehearsing behaviours, thoughts, and emotions (Bandura, 1977; 1997; 2004; Bandura et al., 1999).

The SLT is relevant to the current study in several ways. First, the theory suggests that individuals can learn and adopt new behaviours and attitudes through observing and imitating others. This can be applied to the mentorship relationship, where the protégé can observe and imitate the behaviour of their mentor, learning from their experience and expertise. In turn, the mentor can model the importance of institutional support and collaboration in their research, helping the protégé understand the role these factors play in their research productivity. Thus, the mentor's behaviour can serve as a model for the protégé to develop new skills, attitudes, and behaviours relevant to their research. Second, the SLT highlights the role that environmental factors can play in shaping behaviour. In this context, the institutional environment can shape the mentorship experience and the protégé's research productivity. A supportive institutional environment that provides resources and opportunities for collaboration can foster the development of new behaviours and attitudes, leading to increased research productivity. On the other hand, an unsupportive institutional environment can hinder the protégé's ability to learn and grow, limiting their research productivity.

Third, the SLT emphasises the interplay between cognitive, behavioural, and environmental factors in shaping behaviour. This means that the protégé's beliefs and attitudes about institutional support and collaboration can impact the effectiveness of the mentorship experience. For example, a protégé with a negative view of institutional support may be less likely to take advantage of resources and opportunities provided by their institution. In contrast, a protégé with a positive view of institutional support may be more likely to seek out and utilise these resources actively. By understanding cognitive factors' role in shaping behaviour, researchers can design mentorship programmes that effectively leverage these mechanisms to promote research productivity.

In summary, the Social Learning theory can be relevant to this study by treating institutional support and collaboration as mediating variables linking mentorship and institutional support to research productivity by highlighting the role that observation and imitation, environmental factors, and cognitive factors can play in shaping behaviour. This means that the protégé's thoughts, attitudes, and beliefs about themselves and their work as a researcher can impact the effectiveness of the mentorship experience. For example, a protégé who has low self-efficacy may be less likely to take risks and try new things, whereas a protégé who has high self-efficacy may be more likely to take advantage of the opportunities provided by their mentor. By understanding these mechanisms, researchers can design mentorship programmes that effectively promote research productivity by leveraging institutional support and collaboration.

1.6 Research questions

Based on the review of related studies and the gaps identified, the current study was particularly designed to provide answers to questions such as:

-

1.

How much do collaboration and institutional culture jointly and partially mediate the relationship between mentorship and the research productivity of academic staff?

-

2.

How much do collaboration and institutional culture jointly and partially mediate the nexus between institutional support and the research productivity of academic staff?

1.7 Hypotheses

-

1.

The indirect effect of mentorship on the research productivity of academic staff, with collaboration and institutional culture as joint and partial mediators, is not significantly different from zero.

-

2.

The indirect effect of institutional support on the research productivity of academic staff, with collaboration and institutional culture as joint and partial mediators, is not significantly different from zero.

2 Methods

2.1 Research framework and design

This study adopted the quantitative research method, following the correlational design. The quantitative research framework was considered due to the variables' nature and how they were measured. The correlational research design was explicitly adopted because it was in the interest of the researchers to test for several relationships among the predictors, mediators and endogenous variables. Furthermore, “the data used to test mediation analysis are usually correlational, and such data are limited in their capacity to yield clear conclusions regarding causality” (Iacobucci, 2008; p.4).

2.2 Variables of the study

We considered five specific variables in this study—mentorship, institutional support, collaboration, institutional culture and research productivity. Mentorship and institutional support are the predictors of the study; collaboration and institutional culture are the mediators; the research productivity of academic staff is the criterion variable. Following are the operational definitions of these variables.

Mentorship is operationally defined as the guidance and support provided by more experienced or senior researchers to less experienced or junior researchers. This guidance and support can take various forms, such as providing advice on research projects, offering feedback on drafts of papers, introducing mentees to potential collaborators or funding sources, and providing advice on navigating the academic job market. The goal of mentorship is to help mentees develop the skills and knowledge needed to become successful and productive researchers in their own right.

Institutional support (IS) is operationally defined as the resources, policies, and practices that academic institutions provide to support the research activities of their faculty and staff. It includes variables like access to research funding, research facilities, and specialised equipment, as well as support services like research administration, library resources, and IT support. It can include academic freedom and protection for researchers, policies that promote work-life balance, and opportunities for professional development.

Collaboration is defined as the process of working together with other researchers in the same or different field of studies in the same department/institution or other institutions to conduct research, analyse data, and publish findings. Collaboration can be a key driver of research productivity because it allows researchers to pool their expertise, share resources, and benefit from their collaborators' diverse perspectives and skill sets.

Institutional culture (IC) refers to the shared values, norms, and beliefs that shape the attitudes and behaviours of individuals within different academic institutions. It includes the mission and vision, values and priorities, as well as the expectations and incentives placed on faculty and staff in academic institutions. IC can profoundly impact research productivity because it can shape the attitudes and behaviours of researchers in ways that either support or hinder their ability to conduct high-quality research. For example, a positive IC that values and encourages research productivity can foster an environment in which researchers feel supported, motivated, and empowered to conduct their work effectively and vice versa.

Research productivity (RP) refers to the ability of researchers to conduct high-quality research and produce a significant volume of scholarly output. More specifically, RP includes publishing papers in reputable journals, presenting research at conferences, securing grants and funding, number of undergraduate and postgraduate research supervised, and current h-index and citation counts in recognised databases. Research productivity can be influenced by various factors—the availability of resources and support, the level of mentorship and guidance provided, the opportunities for collaboration, and the overall culture of the institution.

2.3 Study participants

The population of this study comprised 327 academic staff from the rank of Lecturer II to Professor at the University of Cross River State (UNICROSS). This eligibility criterion was set to this range to consider the views of both seasoned and early career researchers. Besides, to reach the rank of lecturer II, staff must have earned their doctorate degrees and are fully prepared for research engagements. It is generally believed that many individuals can start research engagement after obtaining a doctoral degree. However, the actual engagement in research can vary from person to person and field to field. Hence, the decision to focus on this population was to avoid potential bias or skewing of the data obtained. The population distribution of the study is presented in Table 1. Considering the manageable number of elements in the population (see Table 1), the census approach was adopted to study the entire population. Thus, the participants of this study are 327 academic staff.

2.4 Instrument and measures

The instrument used for data collection was the “Career Empowerment and Research Productivity Questionnaire (CERPQ)”. The tool was designed by the researchers and structured into six sections. Section 1 elicited respondents' biodata such as age, gender, rank and years of work experience. Sections 2 to 6 are designed with six items each to assess mentorship practices, IS practices, collaboration, IC, and RP. Two sample items for mentorship are: My mentor provides me with useful guidance on all my research projects; My mentor helps me to identify new research opportunities in my field. Two sample items for IS are: my university provides adequate financial resources to attend international conferences; my university easily provides researchers with access to the resources they need to conduct their research (such as research facilities, equipment, or support services). Two sample items for collaboration are: I have worked with researchers from other departments within my university on different research engagements; I find it difficult working with researchers from fields that are completely different from mine. Sample items for IC include: my university encourages academic staff to take risks in pursuing new ideas in their research; my university recognises the hardworking/productive academic staff through annual awards. Two sample items for RP are: last year I published more than ten journal articles in Scopus-indexed journals; I have secured over one research grants/external funding in the past three years. All the items in Sects. 2 to 6 of the CERPQ were developed using information from a related literature review. A four-point Likert scale was used to organise all the items in Sects. 2 to 6 of the CERPQ. The response options ranged from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree.

2.5 Validity and reliability

The researchers adopted the quantitative approach to content validity to determine how the items pooled in the questionnaire were rich, relevant, and precise items in measuring targeted constructs. A group of six independent assessors (three research experts and three educational management experts) at the University of Calabar were consulted. Experts in these two fields were used because we considered the fields to be the most closely related to the study's variables. The experts' ratings were used to compute the Item Content Validity Index (I-CVI) and Scale Content Validity Index (S-CVI) of the instrument (see Table 2). The researchers followed the experts' comments on unclear and irrelevant items in developing the second draft of the instrument. The second draft copy of the instrument was subjected to a focus group discussion (FGD) involving ten senior university lecturers from the University of Calabar who were not part of the study's targeted respondents. Qualitative discussions were held regarding the suitability of each item to the targeted domain, the adequacy of the items measuring each variable and possible omissions. Information from the FGD was used to develop the instrument's final draft. The final draft of the instrument was trial tested on 30 lecturers at the University of Calabar (who were neither part of the study's population nor the FGD) to determine the degree of its internal consistency. Cronbach's Alpha approach was adopted for the reliability test, with the result of the analysis presented in Table 2.

2.6 Data collection and analysis procedures

Primary data were collected for this study by administering copies of the questionnaire. Per national and institutional regulations, ethical clearance is not required for survey-based studies (Federal Ministry of Health, 2007). This is because even though the study involved human subjects, no physical, emotional or social risk was associated with participation. However, before collecting data, respondents were assured that the data solicited would be treated aggregately and used purely for academic reasons. All respondents participated voluntarily in the exercise after clear explanations of the study's objectives were also provided. At the end of the exercise, the researchers gathered data from 303 respondents with the support of three research assistants. Twenty-four targeted respondents could not be reached for one reason, leading to an attrition rate of 7.4%.

Nevertheless, the participation rate of 92.6% was considered high enough to proceed with data analysis. For data analysis, all responses were scored, considering differences in the wording of the items. Data were coded into a spreadsheet package according to the variables. According to the recommended Safe Harbour principles of studies involving human subjects, all respondents' biodata were de-identified. Structural equation modelling and Bootstrapping techniques were employed to perform the mediation analysis to answer the research questions and test the study's hypotheses. The analysis was aided using JASP, Hayes’ PROCESS Macro, and AMOS Graphic software.

2.7 Model specification

The SEM for the mediation models of this study is specified as:

where C = Collaboration, IC = Institutional culture, RP = Research Productivity, M = Mentorship, IS = Institutional support, β0 = Intercept, βM, βC, βIC, and βIS = partial contribution of mentorship, collaboration, IC, and IS while controlling for the effect of other variables εc, εIc, and εRP = error terms of the outcome variables such as collaboration, IC, and RP.

3 Results

3.1 Research question 1

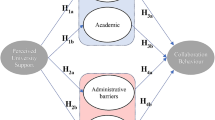

Structural equation modelling (SEM) was performed to determine how much collaboration and institutional culture (IC) jointly and partially mediate the relationship between mentorship and the research productivity (RP) of academic staff in public universities. Figure 1 shows that mentorship, collaboration and IC jointly accounted for 34.6% of the total variance in the RP of academic staff, with 64.4% of the unaccounted portion of the variance due to other factors not enlisted in the model. The model also showed that 35.3% of the variance in collaboration among staff is due to mentorship. Therefore, 64.7% of the unexplained variance is attributable to other predictor variables outside the model. Furthermore, Fig. 1 shows that mentorship contributes 3.4% to the development of IC, with an unexplained variance of 96.6% due to other factors not included in the model.

Relatively, mentorship positively predicted collaboration among staff (B = 0.591, β = 0.594, t = 12.842, SE = 0.046, p < 0.001) and IC (B = 0.179, β = 0.186, t = 3.283, SE = 0.055, p < 0.001) to a significant extent in the public university. This implies that a 1% increase in mentorship is associated with a 0.6 and 0.2% change in collaboration and IC, among other things being equal. However, Fig. 1 revealed that mentorship had a negative but insignificant contribution to the RP of academic staff in the public university (B = − 0.009, β = − 0.016, t = − 0.278, SE = 0.028, p > 0.05). Similarly, there was an insignificant positive contribution of IC to the RP of academic staff (B = 0.002, β = 0.003, t = 0.059, SE = 0.028, p > 0.05). Furthermore, Fig. 1 also showed a significant positive contribution of collaboration to the RP of academic staff (B = 0.339, β = 0.597, t = 10.326, SE = 0.033, p < 0.05). The result suggested that a 1% increase in collaboration among staff is associated with 0.6% improvement in their RP, assuming other things are held constant.

Regarding the mediation, Fig. 1 shows that mentorship has a total effect of β = 0.339 on academic staff RP. Out of this effect, β = − 0.016 is direct and β = 0.356 is indirect—the indirect effect results from the joint mediation of IC and collaboration. Therefore, collaboration and IC jointly mediate the nexus between mentorship and the RP of academic staff at the public university.

3.2 Research question 2

Mediation SEM was performed to examine the extent to which collaboration and institutional culture (IC) jointly and partially mediate the nexus between institutional support (IS) and research productivity (RP) among academic staff. Figure 2 shows that IS, collaboration and IC are jointly accountable for 35.5% of the overall variance in the RP of academic staff. Thus, 64.5% of the unexplained variance is attributable to other extraneous factors in the model. It is also shown that IS accounted for 3.6 and 2.5% of the variance in collaboration and IC, respectively. By implication, 96.4 and 97.5% of the unexplained variance in collaboration and IC are attributable to other factors not included in the model.

Partially, Fig. 2 shows that IS significantly contributed to collaboration (B = 0.194, β = 0.190, t = 3.367, SE = 0.058, p < 0.01) and IC (B = 0.155, β = 0.157, t = 2.756, SE = 0.056, p < 0.001), respectively. This result suggests that, other things being equal, a 1% improvement in the IS provided to academic staff is tied to 0.20 and 0.16% improvements in their collaboration practices and IC, respectively. However, Fig. 2 shows that IS has a positive but insignificant contribution to the RP of academic staff (B = 0.050, β = 0.087, t = 1.826, SE = 0.028, p > 0.05). Figure 2 also shows that IC negatively and insignificantly predicted the RP of academic staff (B = − 0.004, β = − 0.007, t = − 0.140, SE = 0.027, p > 0.05). Nevertheless, Fig. 2 further proved that collaboration has a significant positive contribution to the RP of academic staff (B = 0.326, β = 0.573, t = 12.180, SE = 0.027, p < 0.01).

In terms of the mediation, results showed that IS had a total effect of β = 0.195 on the RP of academic staff. However, the total effect was proven to be a product of β = 0.087 (direct effect) and β = 0.108 (indirect effect). The indirect effect of IS on the RP of academic staff is due to the mediation of IC and collaboration. Therefore, collaboration and IC mediate the nexus between IS and the RP of academic staff.

3.3 Hypothesis 1

The first hypothesis was tested at the 95% confidence interval and 0.05 alpha level. Table 3 confirmed that mentorship has a non-significant negative direct contribution to academic staff's research productivity (RP). Using the bootstrapping technique to explain the significance of the indirect effect, we used the lower and upper bounds of the bootstrapped confidence interval. The rule is that the value of the indirect effect must fall between the lower and upper bounds (i.e. it must fall within the range of BootLLCI and BootULCI) to be greater than zero.

The last part of Table 3 shows that the indirect effect (β = 0.200) of mentorship on the RP of academic staff, with collaboration and institutional culture (IC) as joint mediators, falls within the range of 0.142 and 0.268. This implies that the indirect effect of mentorship on the RP of academic staff, with collaboration and IC as mediators, is significantly different from zero. Based on this evidence, the null hypothesis was disregarded, and the alternative hypothesis was adopted. Therefore, collaboration and IC are significant joint mediators of the nexus between mentorship and the RP of academic staff. When we controlled for the effect of IC, it was discovered that collaboration partially mediated the relationship between mentorship and research productivity of academic staff to a significant extent (β = 0.200 > 0.143, but < 0.268). Therefore, the mediation of collaboration on the relationship between mentorship and the RP of academic staff after discounting for IC is significantly different from 0. On the contrary, IC did not significantly mediate the relationship between mentorship and the RP of academics when we controlled for the effect of collaboration. Therefore, the mediation of IC on the relationship between mentorship and the RP of academic staff after discounting for collaboration is not significantly different from 0.

From Table 3, the following linear equations were fitted:

3.4 Hypothesis 2

For the second hypothesis, Table 4 shows that academic staff's research productivity (RP) received a total indirect effect of β = 0.063 from the joint mediation of institutional culture (IC) and collaboration. The joint mediation of collaboration and IC was significantly different from zero. Consequently, the null hypothesis was discarded, whereas the alternative hypothesis was upheld. This indicated that although the provision of institutional support (IS) alone is not a decisive factor in boosting the research productivity of academic staff significantly (β = 0.050, SE = 0.028, t = 1.83, p > 0.05), accompanying it with effective collaboration and IC uplifts the RP of academic staff significantly. When we controlled for the effect of IC, the result showed that collaboration had a significant partial mediation on the nexus between IS and the RP of academic staff. This implies that the indirect effect of IS on the RP of academic staff, with collaboration as the mediator, is significantly different from zero. On the other hand, IC did not significantly mediate the nexus between IS and the RP of academic staff after controlling for the effect of collaboration; thus, its partial mediation is not significantly different from zero.

The following linear equations were fitted using the result in Table 4:

4 Discussion

This study used a structural equation mediation modelling to analyse a series relationships between mentorship, institutional support (IS), collaboration, institutional culture (IC) and research productivity (RP) among academic staff in a Nigerian public university. This study established that mentorship had a negative but non-significant contribution to the research productivity of academic staff. However, mentorship only promoted research productivity among academic staff when it was followed by IC and collaboration. One possible implication of this finding is that mentorship programmes alone may not adequately support academic staff in their research endeavours. Instead, a supportive and collaborative IC may be key to promoting research productivity among academic staff. For example, an IC that values and encourages collaboration, open communication, and sharing resources and expertise may be more conducive to research productivity than a more hierarchical or competitive culture. Therefore, universities should focus on providing mentorship and fostering an IC that promotes collaboration and support among academic staff. Another implication of this finding is that mentorship programmes in public universities may not be well-designed or implemented to support academic staff in their research endeavours effectively. For example, the mentorship may not align well with the mentees' research interests or may not support their needs. This corroborates the finding of Chitsamatanga et al. (2018) that mentoring is important in universities theoretically, but the practical concept appears to be surrounded by grey areas. The result further agrees with Okurame, cited in Undiyaundeye and Basake (2017), who found that mentoring relationships were more helpful to the mentor than the mentees. However, the result disagrees with the evidence of other studies which established a positive relationship between mentorship and the research productivity of academic staff in public universities (Abugre & Kpinpuo, 2017; Arkaifie & Owusu-Acheampong, 2019; Carmel & Paul, 2015; Okon et al., 2022). The disagreements in the results are attributable to contextual variations and suggest the possibility of further research on mentorship and research productivity among academic staff in universities.

This study established that mentorship significantly affected collaboration and IC in public universities. This is an important finding because it highlights the value of mentorship in fostering a positive and productive working environment within universities. One implication of this finding is that universities should place a greater emphasis on mentorship programmes. By providing mentorship opportunities for students and faculty, universities can promote collaboration and synergy among their members. This can lead to a more cohesive and effective institution, with better outcomes for students and faculty. Another implication of this finding is that universities should make an effort to ensure that mentorship programmes are inclusive and accessible to all members of the university community. This can be achieved through targeted recruitment efforts and mentorship opportunities for underrepresented groups such as women and minorities.

This study further found that mentorship indirectly affected the research productivity of academic staff, with collaboration and IC acting as joint mediators. This finding is explainable since it suggests that providing mentorship opportunities for faculty can promote collaboration and a positive IC, which can, in turn, lead to increased research productivity. Specifically, the study found that when the effect of IC was controlled for, collaboration partially mediated the relationship between mentorship and the research productivity of academic staff. This is an important finding because it suggests that collaboration plays a significant role in the relationship between mentorship and research productivity. This finding implies that universities should prioritise collaboration as a key component of their mentorship programmes for academic staff. By promoting collaboration among mentees and mentors, universities can increase the effectiveness of mentorship for research productivity. Therefore, universities should create a positive IC that supports collaboration and mentorship. This can be achieved by promoting open communication, trust and mutual respect among academic staff. This corroborates the finding of Alaa and Ahmad (2020) that collaboration has the highest positive and significant impact on research productivity. Similarly, other scholars have also shown that collaboration synergises original ideas from scientists with complementary backgrounds or even from different disciplines (Rigby & Edler, 2005; Katz & Martin in Abramo, D'Angelo & Murgia, 2017).

The study found that when controlling for the effect of collaboration, IC did not significantly mediate the relationship between mentorship and the research productivity of academic staff. This finding is critical because it suggests that IC may not play as significant a role in the relationship between mentorship and research productivity as previously thought. Therefore, universities should focus on promoting collaboration and mentorship as key factors in increasing the research productivity of academic staff rather than solely focusing on creating a positive IC. By providing mentorship opportunities and promoting collaboration, universities can increase the research productivity of academic staff without necessarily having to change the overall culture of the institution. The finding does not mean that IC is unimportant; it could mean that its impact on research productivity is less direct than collaboration and mentorship. Therefore, universities should continue to promote a positive IC, as it can positively impact academic staff's overall well-being and satisfaction. After all, Hedjazi and Behravan (2011) found that institutional characteristics, such as a network of communication with colleagues, facilities, corporate management, and transparent research objectives, significantly predict faculty members' research productivity.

The second aspect of the study documented that IS has a positive but insignificant contribution to the research productivity of academic staff in public universities. This finding suggests that while IS is beneficial for the research productivity of academic staff, it may not be the most critical factor in determining their productivity levels. This could imply that universities should not solely focus on increasing IS to improve research productivity among academic staff. Instead, they should also consider other factors that may be more influential, such as the availability of funding, resources, and opportunities for collaboration. This aligns with Hadjinicola and Soteriou's (2006) finding that the presence of a research centre, funding from external sources and better library facilities increased the research productivity and the quality of the articles published by the professors. This result does not support the study of Salau et al. (2018), which identified meaningful work and growth opportunities as predictive factors for maximising productivity in the sampled institutions.

The joint mediation of collaboration and IC was proven to be significant in the nexus between IS and the research productivity of academic staff. The findings indicate that while IS alone may not significantly impact research productivity, the presence of both collaboration and a positive IC can serve as mediating factors, leading to increased research productivity. This suggests that universities should place a greater emphasis on fostering collaboration among their academic staff. This can be achieved through various initiatives such as funding opportunities for collaborative research projects, providing resources for interdisciplinary research, and encouraging staff to attend workshops and conferences that promote networking and collaboration. This finding supports the position of some earlier advocating for collaborative ties among scholars for complementary benefits (Abramo et al., 2017; Rigby & Edler, 2005).

The findings of this study discovered, when controlling for the effect of IC, that collaboration has a significant partial mediation effect on this relationship. This implies that IS may lead to increased research productivity, but the level of collaboration among staff largely mediates this effect. This finding is not surprising because the involvement of different researchers in a project has been found to permit more efficient use of time and limits the need to resort to external advisors (Barnett et al. cited in Abramo et al., 2017). On the other hand, IC did not significantly mediate this relationship after controlling for the effect of collaboration. This suggests that while IC may play a role in shaping the research productivity of academic staff, it may not be as important as collaboration in this regard. These findings suggest that universities focus on fostering a culture of collaboration among academic staff to maximise the impact of IS on research productivity. This could be achieved through team-based research projects, interdisciplinary, transdisciplinary or multidisciplinary collaborations and regular workshops to encourage collaboration. Furthermore, institutions could recognise the importance of collaboration in driving research productivity and allocate resources accordingly. This could include funding collaborative research projects, supporting interdisciplinary teams and creating opportunities for staff to share their research findings and ideas.

4.1 Limitations and implications of the study

Like every other study, this study has some limitations that must be considered when interpreting the results. First, the study was conducted in a single public university in Cross River State, Nigeria, and the results may not be generalisable to other universities or countries. Therefore, scholars in other contexts may consider replicating this study to determine the degree of consistency in results to promote generalisations. Second, the study relied on self-reported data from academic staff, which may be subject to biases and inaccuracies. Therefore, future studies may consider using qualitative or mixed methods approaches to enrich the results of this study with further information explaining the series of relationships established in the study. Thirdly, the study was conducted over a relatively short period. Further longitudinal research is needed to examine the long-term effects of mentorship, institutional support, collaboration, and institutional culture on research productivity. The study did not control for other potential factors that may influence research productivity, such as personal characteristics of the researchers (such as age, gender, rank, and experience), funding, equipment, and infrastructure, which may have an impact on the results.

Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights into the relationships between mentorship, institutional support, collaboration, institutional culture, and research productivity of academic staff in a university setting. The results of this study can be useful for other universities seeking to enhance the research productivity of their academic staff. The study highlights the importance of considering multiple factors that may influence research productivity and suggests that institutions should prioritise fostering a supportive and collaborative environment for academic staff to maximise their research productivity. The study can also inform the development of mentorship programmes and the creation of institutional policies that support and promote research productivity.

The results of this study have the potential to inform and guide the development of mentorship programmes and the creation of institutional policies in other universities and contexts. The findings that mentorship alone is insufficient to promote research productivity and that a supportive and collaborative environment is important for enhancing the impact of mentorship can serve as a starting point for universities to reflect on their current practices and policies. Additionally, the results highlighting the importance of collaboration and institutional culture in predicting research productivity can be used to inform the development of strategies for fostering collaboration and creating a positive institutional culture. For example, universities can use the results of this study to assess their current level of collaboration among academic staff and identify potential barriers to collaboration that need to be addressed. They can also use the results to evaluate their current institutional culture and determine if changes need to be made to promote a positive and supportive environment for academic staff. Furthermore, the results of this study can serve as a starting point for further research in other universities and contexts. This study only examined a single university in Nigeria, and future research could replicate the study in other universities and countries to test the generalizability of the results and gain a deeper understanding of the relationships between mentorship, institutional support, collaboration, institutional culture, and research productivity.

5 Conclusion

This study was designed to estimate the direct and indirect contributions of mentorship and institutional support (IS) to academic staff's research productivity (RP) at a public university in Cross River State, Nigeria. Two mediator variables—collaboration and institutional culture (IC), were introduced to determine their roles in the nexus between the predictors and the criterion variables. Several meaningful relationships among the variables of this study were uncovered. Based on these findings, it is generally concluded that mentorship negatively contributes to academic staff's RP. However, this effect can be mitigated by a positive IC and a strong collaborative network. This conclusion suggests that mentorship alone is insufficient to promote RP and that institutions should focus on fostering a supportive and collaborative environment for academic staff to enhance the impact of mentorship. It is also concluded that institutional support has a positive but insignificant tie to the RP of academic staff. However, when collaboration and IC are considered, the effect of IS becomes significant. This highlights the importance of considering multiple factors that may influence the research productivity of academic staff rather than focusing solely on IS. Collaboration is the most important factor that directly predicts the research productivity of university academic staff. Collaboration also plays a mediating role in the relationship between mentorship, IS and RP. This conclusion implies that institutions should prioritise fostering collaboration among academic staff to maximise their RP.

Data and material availability

The authors state that the data for this research were acquired from primary sources through a survey (administration of questionnaires). The data used or analysed for this research are accessible upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Abimbola, I. O., Tola, O., Popoola, B. G., Folorunso, J. O., Amao-Taiwo, B., Ige, O. O., Ekpe-Iko, G. N., Dike, M. C., Adebiyi, D. A., & Eze, B. U. (2021). Unethical research practices: An empirical evaluation of “abeg add my name” malady in Nigeria. Hallmark University Journal of Management and Social Sciences, 3(1), 191–204.

Abramo, G., D’Angelo, A. C., & Murgia, G. (2017). The relationship among research productivity, research collaboration, and their determinants. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 1016–1030. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.09.007

Abugre, J. B., & Kpinpuo, S. D. (2017). Determinants of academic mentoring in higher education: Evidence from a research University. Educational Process: International Journal, 6(2), 20–36. https://doi.org/10.22521/edupij.2017.62.2

Adetayo, A. J., Adeleke, O. A., & Lateef, E. B. (2023). Does the physical work environment of librarians influence research productivity? Libraries and the Academy, 23(1), 23–33.

Agarwal, A., Durairajanayagam, D., Tatagari, S., Esteves, S. C., Harlev, A., Henkel, R., Roychoudhury, S., Homa, S., Puchalt, N. G., Ramasamy, R., & Majzoub, A. (2016). Bibliometrics: Tracking research impact by selecting the appropriate metrics. Asian Journal of Andrology, 18(2), 296–309. https://doi.org/10.4103/1008-682X.171582

Akbaritabar, A., Casnici, N., & Squazzoni, F. (2018). The conundrum of research productivity: A study on sociologists in Italy. Scientometrics, 114(3), 859–882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2606-5

Alaa, S. J., & Ahmad, A. (2020). Factors impacting research productivity of academic staff at the Iraqi higher education system. International Business Education Journal, 13(1), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.37134/ibej.vol13.1.9.2020

Al-Enazi, G. T. (2016). Institutional support for academic staff to adopt virtual learning environments (VLEs) in Saudi Arabian Universities. (PhD Thesis), Durham University. http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11417/.

Anyaogu, U., & Iyabo, M. (2014). Demographic variables as correlates of lecturers’ research productivity in faculties of law in Nigerian universities. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 34(6), 7962. https://doi.org/10.14429/djlit.34.6.7962

Arkaifie, S. J., & Owusu-Acheampong, E. (2019). An assessment of mentoring programme among new lecturers at the University of Cape Coast. European Journal of Training and Development Studies, 6(4), 29–39.

Ayesha, B., Saghir, A., & Sadaf, N. (2021). Correlation of personal and institutional factors with research productivity among university teachers. Humanities & Social Sciences Reviews, 9(2), 240–246. https://doi.org/10.18510/hssr.2021.9225

Bai, L. (2010). Enhancing research productivity of TEFL academics in China. (Unpublished PhD Thesis), Queensland University of Technology. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/41732/

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1979-05015-000

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice Hall. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1985-98423-000

Bandura, A. (1997). Exercise of personal and collective efficacy in changing societies. In A. Bandura (Ed.), Self-efficacy in Changing Societies (pp. 1–45). Cambridge University Press. https://bit.ly/3WJyFUY

Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 2(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-839X.00024

Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

Bandura, A., Freeman, W. H., & Lightsey, R. V. (1999). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 2, 158–1999. https://doi.org/10.1891/0889-8391.13.2.158

Barber, B. M., Jiang, W., Morse, A., Puri, M., Tookes, H., & Werner, I. M. (2021). What explains differences in finance research productivity during the pandemic? The Journal of Finance, 76(4), 1655–1697. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.13028

Bassey, U. U., Akuegwu, B. A., Udida, L., & Udey, F. (2007). Academic staff research productivity: A study of Universities in South-South Zone of Nigeria. Educational Research and Review, 2(5), 103–108.

Bland, C. J., Center, B. A., Finstad, D. A., Risbey, K. R., & Staples, J. G. (2005). A theoretical, practical, predictive model of faculty and department research productivity. Academic Medicine, 80(3), 225–237. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200503000-00006

Butler, D. L. (2003). Explaining Australia’s increased share of ISI publications: The effects of a funding formula based on publication counts. Research Policy, 32(1), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00007-0

Carmel, R. G., & Paul, M. W. (2015). Mentoring and coaching in academia: Reflections on a mentoring/coaching relationship. Policy Futures in Education, 13(4), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210315578562

Carpenter, C. R., Cone, D. C., & Sarli, C. C. (2014). Using publication metrics to highlight academic productivity and research impact. Academic Emergency Medicine, 21(10), 1160–1172. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.12482

Cheek, J., Garnham, B., & Quan, J. (2006). What’s in a number? Issues in providing evidence of impact and quality of research(ers). Qualitative Health Research, 16(3), 423–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305285701

Chitsamatanga, B. B., Rembe, S., & Shumba, J. (2018). Mentoring for female academics in the 21st century: A case study of a South African University. International Journal of Gender and Women’s Studies, 6(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.15640/ijgws.v6n1a5

Ding, J., Liu, C., & Kandonga, G. A. (2020). Exploring the limitations of the h-index and h-type indexes in measuring the research performance of authors. Scientometrics, 122, 1303–1322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03364-1

Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. (2019). The H-index in life and health sciences: Advantages, drawbacks and challenging opportunities. Current Drug Research Reviews Formerly: Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 11(2), 82–84. https://doi.org/10.2174/258997751102191111141801

Eam, P. (2015). Factors differentiating research involvement among faculty members: A perspective from Cambodia. Excellence in Higher Education, 6(1&2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5195/EHE.2015.133

Falola, H. O., Adeniji, A. A., Adeyeye, J. O., Igbinnoba, E. E., & Atolagbe, T. O. (2020). Measuring institutional support strategies and faculty job effectiveness. Heliyon, 6, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03461

Farooqi, S. M., Shahzad, S., & Tahira, S. S. (2019). Who are more successful researchers? An analysis of university teachers’ research productivity. Global Social Sciences Review, 4(1), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.31703/gssr.2019(IV-I).46

Federal Ministry of Health (2007). National code of research ethics. Federal Ministry of Health. https://portal.abuad.edu.ng/lecturer/documents/1588255709NCHRE_Aug_07.pdf.

Friday, J. E., & Okeke, I. E. (2020). Relationship between job satisfaction and research productivity of librarians in public university libraries in South-South Nigeria. UNIZIK Journal of Research in Library and Information Science, 5(1), 101–120.

Ghabban, F., Selamat, A., Ibrahim, R., Krejcar, O., Maresova, P., & Herrera-Viedma, E. (2019). The influence of personal and organisational factors on researchers’ attitudes towards sustainable research productivity in Saudi universities. Sustainability, 11(17), 4804. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11174804

Glick, M. (2016). Publish and perish. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 147(6), 385–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adaj.2016.04.002

Hadjinicola, G. C., & Soteriou, A. C. (2006). Factors affecting research productivity of production and operations management groups: An empirical study. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Decision Sciences, 2006, 096542. https://doi.org/10.1155/JAMDS/2006/96542

Hedjazi, Y., & Behravan, J. (2011). Study of factors influencing research productivity of agriculture faculty members in Iran. Higher Education, 62(5), 635–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9410-6

Henry, C., Nor, A. M. G., Hamid, U. M. A., & Ahmad, N. B. (2020). Factors contributing towards research productivity in higher education. International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education, 9(1), 203–211. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v9i1.20420

Hiire, G. B., Oonyu, J., Kyaligonza, R., & Onen, D. (2020). Organisational factors as antecedents of university academic staff research productivity. Journal of Education and Practice, 11(18), 94–103.

Horta, H., Cattaneo, M., & Meoli, M. (2016). PhD funding as a determinant of PhD and career research performance. Studies in Higher Education, 43, 542–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1185406

Iacobucci, D. (2008). Introduction to mediation. In Mediation analysis (pp. 2–10). SAGE Publications, Inc., https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984966.n1.

Jaime, P. P. (2020). Transformational behaviour of department heads and ICT integration: Their impact on the research productivity of faculty members. International Journal of Advanced Trends in Computer Science and Engineering, 9(1.2), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.30534/ijatcse/2020/1491.22020

Jameel, A. S., & Ahmad, A. R. (2020). Factors impacting research productivity of academic staff at the Iraqi higher education system. International Business Education Journal, 13(1), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.37134/ibej.vol13.1.9.2020

Kpolovie, P. J. (2014). Quality assurance in the Nigerian educational system: Matters arising. Academia Education, 6(4), 1–87.

Kpolovie, P. J., & Dorgu, I. E. (2019). Comparison of faculty’s research productivity (h-index and citation index) in Africa. European Journal of Computer Science and Information Technology, 7(6), 57–100.

Kpolovie, P. J., Onoshagbegbe, E., & S. (2017). Research productivity: h-index and i10-index of academics in Nigerian universities. International Journal of Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methods, 2, 62–123.

Kyaligonza, R. (2015). An investigative study of research productivity of the academic staff in public universities in Uganda. Direct Research Journal of Social Science and Educational Studies, 2(4), 60–68.

Kyaligonza, R., Kimoga, J., & Nabayego, C. (2015). Funding of academic staff’s research in public universities in Uganda: Challenges and opportunities. Makerere Journal of Higher Education, 7(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.4314/majohe.v7i2.10

Lambovska, M., & Todorova, D. (2021). ‘Publish and flourish’ instead of ‘publish or perish’: A motivation model for top-quality publications. Journal of Language and Education, 7(1), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.17323/jle.2021.11522

Li, Y., & Zhang, L. J. (2022). Influence of mentorship and the working environment on English as a foreign language teachers’ research productivity: The mediation role of research motivation and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 3383. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.906932

Loan, F. A., Nasreen, N., & Bashir, B. (2022). Do authors play fair or manipulate Google Scholar h-index? Library Hi Tech, 40(3), 676–684. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-04-2021-0141

Maharjan, M. P., Stoermer, S., & Froese, F. J. (2022). Research productivity of self-initiated expatriate academics: Influences of job demands, resources and cross-cultural adjustment. European Management Review, 19(2), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12470

Masinde, M., & Coetzee, J. (2021). Modelling research productivity of university researchers using research incentives to crowd-in motivation. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPPM-12-2020-0669

Milem, J. F., Berger, J. B., & Dey, E. L. (2000). Faculty time allocation: A study of change over twenty years. The Journal of Higher Education, 71(4), 454–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2000.11778845

Mugimu, C. B., Nakabugo, M. G., & Katunguka, E. R. (2013). Developing capacity for research and teaching in higher education: A case of Makerere University. World Journal of Education, 3(6), 33–45. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v3n6p33

Musiige, G., & Maassen, P. (2015). Faculty perceptions of the factors that influence research productivity at Makerere University. African Minds Higher Education Dynamics Series, 1, 109–127. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.824663

Ndege, T. M., Migosi, J. A., & Onsongo, J. (2011). Determinants of research productivity among academics in Kenya. International Journal of Education, Economics and Development, 2, 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEED.2011.042406

Nguyen, P. V. (2022). Influence of institutional characteristics on academic staff’s research productivity: The case of a Vietnamese research-oriented higher education institution. Vietnam Journal of Education, 6(3), 196–208. https://doi.org/10.52296/vje.2022.202

Nur-tegin, K., Venugopalan, S., & Young, J. (2020). Teaching load and other determinants of research output among university faculty. The American Economist, 65(2), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0569434520930702

Okon, A. E., Owan, V. J., & Owan, M. V. (2022). Mentorship practices and research productivity among early-career educational psychologists in universities. Educational Process International Journal, 11(1), 105–126. https://doi.org/10.22521/edupij.2022.111.7

Okonedo, S., Popoola, S. O., Emmanuel, S. O., & Bamigboye, O. B. (2015). Correlational analysis of demographic factors, self-concept and research productivity of librarians in public universities in South-West, Nigeria. International Journal of Library Science, 4(3), 43–52.

Oravec, J. A. (2019). The" dark side" of academics? Emerging issues in the gaming and manipulation of metrics in higher education. The Review of Higher Education, 42(3), 859–877. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2019.0022

Owan, V. J., & Asuquo, M. E. (2022). “Publish or perish,” “publish and perish”: The Nigerian experience. In J. A. Undie, J. B. Babalola, B. A. Bello, & I. N. Nwankwo (Eds.), Management of higher educational systems (pp. 986–994). University of Calabar Press. https://bit.ly/3TEHEDu

Owan, V. J., & Owan, M. V. (2021). Complications connected to using the impact factor of journals for the assessment of researchers in higher education. Mediterranean Journal of Social & Behavioral Research, 5(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.30935/mjosbr/10805

Owan, V. J., Odigwe, F. N., Okon, A. E., Duruamaku-Dim, J. U., Ubi, I. O., Emanghe, E. E., Owan, M. V., & Bassey, B. A. (2022). Contributions of placement, retraining and motivation to teachers’ job commitment: Structural equation modelling of the linkages. Heliyon, 8(4), e09334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09334

Oyekan, O. A. (2014). Resource situation as determinants of academic staff productivity in Nigerian Universities. European Journal of Globalization and Development Research, 9(1), 545–551.