Abstract

In this paper, we discuss the theoretical and methodological issues in exploring identity and agency within a narrative of choosing mathematics. Taking as our starting point Bakhtin’s emphasis on the dialogic space between interlocutors, we explore how an awareness of the addressivity and otherness of utterances, and of the role of genre and heteroglossia in self-authoring, can be used in the analysis of an interview to gain insight into one student’s narrative of choosing mathematics despite the fear that it held for her. We consider how our own research preoccupations with the role of gender and family discourses in learners’ relationships with mathematics played a part in the interview, and how the interviewee’s appropriation of, and resistance to, these and other genres can be understood as an assertion of agency within her particular narrative of choice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Choosing mathematics

Who chooses mathematics, why they choose it and the value of such a choice are major preoccupations for many researchers. Often, this is driven by social justice concerns involved in choosing, or not choosing, mathematics: gender, social class and ethnicity are major predictors of participation, if not achievement (Atweh, Graven, Secada, & Valero, 2011; Forgasz & Rivera, 2012). For example, Mendick analyses the under-participation of girls and women in terms of mathematics as a masculine space requiring identity work for those who do choose it (Mendick, 2005a, b, 2006). Walls (2009) makes a similar point regarding the need for women and girls to take on a different persona in mathematics. Social class and ethnicity are addressed by Noyes (2007), Cooper (2001) and Zevenbergen (2001), focusing on cultural capital and habitus as barriers to participation. Others frame the issues in terms of the undervaluing of local funds of knowledge by dominant school structures (de Abreu & Cline, 2007; Winter, Salway, Yee, & Hughes, 2004) and indeed by students themselves who draw on the socially structuring factors of gender, class and ethnicity in expressing an identity in which mathematics is “not for them” as in the case of African Americans, for example (Martin, 2007).

However, while this work recognises the cross-cutting effects of these major social structures in choosing to study mathematics, it frequently underplays the nature of the interview itself as more than merely a source of data on the operation of discourses in mathematical identity. In this paper, we draw attention to the interview as part of the ongoing process of identification, where close analysis of the dialogic space between interviewee and interviewer reveals an ongoing joint narrative in which interlocutors draw on past, present and future meanings to express and enact agency in an account of choice. Identity is thus emergent in the interview itself and can be seen in terms of the joint orchestration of the multiple voices at play. The interview is a site of assertion of the self and, indeed, can involve resistance to a particular explanation, as in Mendick’s (2006) account of an interviewee’s response to the suggestion that gender underpins her choice of school subjects:

Claudia … is reading herself through the neoliberal fiction of the autonomous self. This compels her to resist connecting being female to lacking power and to disadvantage within her own life. Instead, she attaches these to generalized others and to the impersonal realm of reports, statistics and theories. (pp. 99–100)

Interview accounts of choosing mathematics need to be understood as part of an ongoing emergent self, co-constructions of a narrative of choice between interviewer and interviewee (Solomon, 2012). This is also suggested in Black and Williams’ (2013) analysis of one student’s account of her choice of being an engineer in contradiction to other demands on her (being a good Muslim woman); they argue that individual agency is engendered through conscious reflection on such contradictions: “the adult can, in the right circumstances, come to see these selves and contradictions, and through semiotic action (i.e. discourse with others and self-reflection), come to have some degree of control over them” (p. 11). In this paper, we analyse a narrative of choosing mathematics with a focus on exploring and extending our conception of agency. Specifically, we focus on the role of genre in the dialogue as a central resource for both interviewer and interviewee in their co-construction of the narrative, drawing on Bakhtin’s theorising of self-authoring to develop an interpretation of agency in terms of rejection and appropriation of available genres. Focusing first on Bakhtin’s emphasis on dialogism, heteroglossia and addressivity, our discussion considers how these concepts enable us to offer an analysis which captures the complexity of engagement with mathematics as a (far from neutral) subject which plays a central part in the ongoing storying of self. Having introduced the central Bakhtinian concepts that we have drawn on in our analysis, we demonstrate their application in analysis of a conversation between the first author and a student teacher of mathematics, focusing first on her use of genre in an authoring of self in conflict and second on the role of genre in the conversation itself as a dialogic space. Finally, the paper discusses the analysis process itself and its illustration of the interviewee’s emergent identity in dialogic relation to the interviewer, as a departure from standard analyses of students’ participation in mathematics. Highlighting the orchestration of genres in the dialogue enables us to see multiple strands of the interviewee’s authoring of self in an account of choice. We argue that our approach shifts the focus away from structural and fixing binaries, providing a more detailed analysis of choice which captures an emergent and ongoing identity in her authoring self.

2 Conceptualising the authoring self

In previous work on identity, choice and mathematics (Braathe, 2010; Braathe & Ongstad, 2001; Solomon, 2012), we have drawn on Bakhtin’s genre theory in order to capture the multi-voicedness and dialogicality of narratives of self. Following van Enk’s (2009) observations on the usefulness of Bakhtin’s concept of genre in an interview analysis which addresses issues of power and the representation of others’ voices, we have reflected further on the nature of the interview itself as the site of storying. Frequently, interview data is analysed with a major focus on the interviewee, but Bakhtin’s dialogism draws attention to the storying of self as a process of addressing and answering, in which the interview can be seen as part of an ongoing narrative in which interlocutors draw on past, present and future meanings in a heteroglossic, multivoiced space of communication. In the following discussion, we explore how dialogism provides tools which enable an analysis of the storying of self, in terms of the appropriation of particular genres—“typical forms of utterance”—alongside resistance to those which are appropriated and offered by the interlocutor.

2.1 Otherness, addressivity and voice

Bakhtin’s project of dialogism is described by one of his major commentators as “a pragmatically oriented theory of knowledge…one of several modern epistemologies that seek to grasp human behaviour through the use humans make of language” (Holquist, 2002, p. 15). It has particular relevance for mathematics education, since it provides us with a means of conceptualising communicative relations in ways which can help us to understand how individuals identify as “mathematical” or not, in terms of linguistic reference points which are shared with others. The role of others in providing the terms in which we “see” ourselves is a central starting point of dialogism, highlighting an important aspect of self which underpins our analysis: our sense of self is always based on, or defined by, “otherness”, and it remains multiple in this sense—it is never synthesised into one:

In dialogism, the very capacity to have consciousness is based on otherness. This otherness is not merely a dialectical alienation on its way to a sublation that will endow it with a unifying identity in higher consciousness. On the contrary: in dialogism consciousness is otherness. (Holquist, 2002, p. 18)

The equation of otherness with consciousness is evident in Bakhtin’s use of voice. As Wertsch (1993, p. 52) points out, for Bakhtin, “meaning comes into existence only when two or more voices come into contact”. Thus, the concept of addressivity is fundamental in the authoring of self:

An essential (constitutive) marker of the utterance is its quality of being directed to someone, its addressivity. … the utterance has both an author … and an addressee. This addressee can be an immediate participant-interlocutor in an everyday dialogue…. And it can also be an indefinite, unconcretized other.... Both the composition and, particularly, the style of the utterance depend on those to whom the utterance is addressed, how the speaker (or writer) senses and imagines his addressees, and the force of their effect on the utterance. (Bakhtin, 1986, p. 95)

This feature of uttering means that we never purely own the words we speak, because “the word in language is half someone else’s”—“it exists in other people’s mouths, in other people’s concrete contexts, serving other people’s intentions: it is from there that one must take the word, and make it one’s own” (Bakhtin, 1981, pp. 293–294). So in speaking, we expropriate the word to form a “hybrid construction”, “an utterance that belongs, by its grammatical [syntactic] and compositional markers, to a single speaker, but that actually contains mixed within it two utterances, two speech manners, two styles, two ‘languages’, two semantic and axiological belief systems” (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 304). Thus, otherness permeates the whole of our being and uttering and brings tensions with it as we struggle to expropriate the other’s words:

And not all words for just anyone submit equally easily to this appropriation, to this seizure and transformation into private property: many words stubbornly resist, others remain alien, sound foreign in the mouth of the one who appropriated them and who now speaks them; they cannot be assimilated into his context and fall out of it; it is as if they put themselves in quotation marks against the will of the speaker. Language is not a neutral medium that passes freely and easily into the private property of the speaker’s intentions; it is populated—overpopulated—with the intentions of others. Expropriating it, forcing it to submit to one’s own intentions and accents, is a difficult and complicated process. (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 294)

This “complicated process” is central to our account; it enables us to capture the relationship between identity, agency and the self. In what follows, we draw further on Bakhtin’s theory to understand how the process of identifying is one of authoring the self within the dialogic space of communication. In expropriating or appropriating the words of others, we necessarily enact agency, and it is in this sense that agency and identity, and self and other, are closely intertwined in a way which is crucial in the emerging narrative of the interview.

2.2 Genre, self-authoring and heteroglossia

The words we use are thus rooted in their use by others. As such, utterances are produced and interpreted in relation to the genres which provide the context of understanding and indeed the addressee’s imagined/anticipated response:

[W]e embrace, understand, and sense the speaker’s speech plan or speech will, which determines the entire utterance, its length and boundaries. We imagine to ourselves what the speaker wishes to say. And we also use this speech plan, this speech will (as we understand it), to measure the finalization of the utterance. (1986, p. 77)

The basis of such understanding lies in the underpinning socially acquired genres which “predetermine” the types of sentences we use and the links between them (1986, p. 81). For Bakhtin, genres are “not a form of language, but a typical form of utterance: as such the genre also includes a certain typical kind of expression that inheres in it” (1986, p. 87). Broadly speaking genres can be defined as kinds of communication:

Genres correspond to typical situations of speech communication, typical themes, and, consequently, also to particular contacts between the meanings of words and actual concrete reality under typical circumstances. (1986, p. 87)

So, in answering and addressing others, we must draw on the genres that are available to us, the typical speech forms with which we describe the world and our action in it with reference to particular themes. But the necessity of drawing on pre-existing cultural resources does not mean that we are inevitably determined by them. In making others’ words our own, choosing language, we exercise agency. Building on Bakhtin’s work in order to theorise human agency and escape from structural determination, Holland, Lachicotte, Skinner, and Cain (1998) suggest that we author the self through the appropriation of genres in an ongoing process of addressivity, and it is here that agency lies, in the choices that we make in the never-ending storying of self:

Bakhtin’s concepts allow us to put words to an alternative vision, organized around the conflictual, continuing dialogic of an inner speech where active identities are ever forming. […] [S]entient beings always exist in a state of being ‘addressed’ and in the process of ‘answering’. People coexist, always in mutual orientation moving to action…. (p. 169)

It is this requirement for choice, and continuous action, which almost forces agency, as Bakhtin notes:

Consciousness finds itself inevitably facing the necessity of having to choose a language. With each literary-verbal performance, consciousness must actively orient itself amidst heteroglossia, it must move in and occupy a position for itself within it, it chooses, in other words, a ‘language’. (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 295)

So, to take us back to the research interview, Bakhtin’s analysis of speech, genre and the authoring of the self brings a new lens to its analysis, enabling us to “witness” the emergence of identity through the enactment of agency in the interview as interlocutors choose their language and appropriate and resist the circulating genres of the dialogue:

But the utterance is related not only to preceding, but also to subsequent links in the chain of speech communion. […] But from the very beginning, the utterance is constructed while taking into account possible responsive reactions, for whose sake, in essence, it is actually created. As we know, the role of the others for whom the utterance is constructed is extremely great. […] From the very beginning, the speaker expects a response from them, an active responsive understanding. The entire utterance is constructed, as it were, in anticipation of encountering this response. (Bakhtin, 1986, p. 94)

It is this process which we focus on here, in order to explore the enactment of agency in one person’s ongoing narrative of choosing mathematics. It is not only being addressed, receiving others’ words, but also the act of responding, which is already necessarily addressed, that inform our world through others. Dialogism makes it clear that what we call identities remain dependent upon social relations and material conditions. If these relations and material conditions change, they must be “answered”, and old “answers” about who one is may be undone. This at the same time gives room for agency as expressed in a continually forming and re-forming narrative of self underpinned by the appropriation of genre for meaning-making, imbued with the goals and intentions of others.

3 Understanding choice through the lens of genre

We focus in this paper on one student’s—we will call her Hedvig—account of her relation to mathematics through her years at school and education so far, constructed in conversation with the first author, HJ, who is also one of her tutors on the masters program in mathematics education which she attends. Inspired by the gender focus of a teaching session led by the second author, and the class discussion which followed, we asked class members if they would be willing to be interviewed to follow up our interest in gender and choosing mathematics. Five female students volunteered, and the resulting unstructured interviews focused on their experiences with mathematics so far during their education. As a particularly rich account of choosing mathematics despite the fear that it held for her, we selected Hedvig’s interview for close analysis here. Clearly, the context of the interview raises issues of power and position since HJ was Hedvig’s tutor. Aware of these issues, HJ was sensitised to their potential impact on the dynamics of the interview, but since this potential cannot necessarily be reduced, our analysis takes it into full account and, as we shall show, forefronting their relationship in our analysis of the dialogic space enables us to explore to the full the way in which Hedvig’s identity emerges in the interview.

Hedvig herself is in her first year of masters study, combining it with her fourth and final year of teacher education. At bachelors level, she has specialised in mathematics, giving her the background for her masters in mathematics education. She is from a small community outside a medium-sized Norwegian city, having spent her primary school years at the local school and moving to the nearby city for her lower and upper secondary school years (grades 8 to 13, ages 13 to 19). The upper secondary school system in Norway involves choosing one of two pathways, general or vocational, but social democratic reforms in 1994 introduced more academic approaches into the vocational pathways in order to enable more students to access university study. Such vocational pathways combine theoretical and vocational subjects, some compulsory and some elective, with elective subjects which are frequently different from those in general upper secondary schools. Hedvig chose an aesthetic study pathway called “drawing, shape and colour”, entering a vocationally oriented upper secondary school but with access to study at the university. At this school, students could elect to take academic subjects which were the same as those offered in general upper secondary schools, including the most academic mathematics courses, giving students access to high status university studies such as medicine and engineering. In general these courses are chosen by few students, particularly students on vocational pathways. We mention this here because Hedvig chose such a specialist mathematics course. We will comment on this fact below in our analysis of the conversation.

The interview was conducted in Norwegian and audio-recorded, then transcribed in Norwegian and initially translated into English by the first author, HJ. This process alone alerted us to many issues regarding the dialogic nature of the interview process and the role of addressivity, as HJ struggled to capture the richness of the conversation in translation. In addition to the difficulties of capturing intonation and timing, as pauses and variations of tempi, in written text, the translation process underlined how much interpretation is involved in any analysis. We recognised the need for co-listening to the recording and for extensive discussion about “meanings” as we worked on the basis of the first author’s initial translation towards a translation which was as close as possible to what we would agree on as the most “correct” (in the sense of being “true” to HJ’s understanding of Hedvig’s meaning, rather than literally correct) transcribed translation. This protracted process demonstrated for us how complex the interview situation is from a communicative perspective, as we noticed the presence of multiple genres and were challenged all the time to notice and consider HJ’s own role in the conversation and the dialogic space created between him and Hedvig. These considerations have led us to make a series of decisions in how we present the data in this paper, choosing at times to privilege the original Norwegian over the English translation which appears in the majority of the analysis. We have used three basic strategies: (1) for the most part, we present the data in translation without interruption; but (2) we have also presented some individual Norwegian words and phrases in square brackets where we wanted to show word-sharing or repetition during the dialogue, or significant lexical choices (particular metaphors, for example), or in order to make our translation transparent in trying to capture subtle differences (for instance between “scared” and “afraid”); and, (3) on occasion, we have presented the whole speech in Norwegian, with an English translation in a footnote where passages were particularly difficult to translate. In this latter type of presentation, we present significant word choices in individual word English translations in square brackets.

Partly as a result of our reflections on the interview and its analysis, we decided to show the first draft of the paper to Hedvig and, 4 weeks later, HJ talked to her again. Their conversation was audio recorded and transcribed and translated into English by HJ. The theme for the conversation was to have Hedvig comment on our story (about her story) as it was presented in the paper. This additional interview enabled some further reflections on our analysis and contributed to the central argument of this paper regarding the dialogic space as a site for agency. In what follows, we first present the unfolding of Hedvig’s story in terms of its construction in the dialogic space which she and HJ inhabit. We focus on addressivity in their talk, with particular attention to their introduction and appropriation of genre themes in the rhythm of their talk as Hedvig tells the story of her engagement with mathematics and HJ questions her about the strangeness of her choice to study it despite her fear. We show that Hedvig sometimes resists HJ’s introduction of a new idea or genre, explicitly on occasion, and that HJ for his part sometimes appropriates genres which she introduces. Subsequently, we focus more on the role of genre in their talk; holding on to Bakhtin’s emphasis on the self as a representation of ourselves to ourselves from the vantage point of others, we argue that Hedvig’s agency, and consequently her emergent identity, is enacted through her use of genre (as opposed to being evidenced by it), including her resistance to the genres which are drawn on and proposed by HJ.

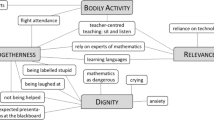

4 Self-authoring—a representation of self as mathematics student

Hedvig’s story is one of the inner struggle between a liking for mathematics which she has “always” had and a fear of mathematics which grew in later years of school. In her story, she uses particular words—fear, angst, fight, struggle [frykt, angst, kamp, kjemping]—to convey her emotions about mathematics and also her actions around combating fear. Note that she uses the word “angst”, which carries the same strong meaning of anxiety and apprehension for both Norwegian and English speakers, as far as we can ascertain. Obviously, in re-telling her story (and choosing her name), we are appropriating another genre.

4.1 The beginning—“I became very afraid of math…”

Hedvig tells HJ that in her early years “math was fun”, but “when I started lower secondary school… I became very afraid of math …”. In what follows, Hedvig and HJ co-construct a story about Hedvig’s fear of mathematics as not actually rational given her marks, elaborating on a theme of fear which Hedvig introduces. In the unfolding discussion, HJ frequently requests clarification in his questioning, repeating Hedvig’s words relating to fear but also extending their application to the idea of mathematics as risky, in order to account for her lack of rationality:

H: I became very afraid [redd] of math …

HJ: Yes .. But did you feel that you got bad grades then or something like that, or was it ..

H: No, I didn’t.... I got the same .... I got really good grades usually … but but … so I didn’t get bad grades .. but

HJ: So it wasn’t that which scared [skremte] you in a way ..

H: No, but I was so afraid [så redd for] I wouldn’t make it … I felt like I wasn’t good enough so …

HJ: Yes .. yeah .. but you got good grades through ..

H: Yes

HJ: But, if you were to say anything more about mathematics [at school] that caused that … or was it just the math .. that there was something risky [usikkert] about it ..

H: Yes .. yes I think so .. also, I had the same feeling [følelsen] at upper secondary .. uh yeah .. I also had good grades … or it [the feeling] started, well, … at the end … I was very very nervous [nervøs] so the grades started to go down.

Towards the end of this extract, Hedvig “corrects” herself about the grades—i.e. she clarifies that her fear was not based on her grades—a contradiction which HJ had pointed out earlier as he argued with her and implied that her good grades made her fear unnecessary. What genre is Hedvig invoking here? She introduces the words “afraid” and “nervous”. It seems that she is appropriating ideas from a genre of mathematics as inherently fearful (see for example Early, 1992). HJ responds to this genre as he probes to understand, and he introduces the idea of uncertainty and risk. At the end of this extract, we see that Hedvig appropriates this idea as she claims that her nervousness made her grades go down, expanding on the link as she introduces a new rationale for her fear, assessment:

HJ: What do you think made you nervous?

H: I think it was mostly in connection with the assessment [vurderingen].

4.2 A complication

And now, a twist in the story: Hedvig volunteers that she chose more mathematics than she needed to—as we note above, advanced courses were available at her school, and she opted to take the most academic course in mathematics in the second year of upper secondary school—something which surprises HJ because he expects her to have stopped as soon as she could, at the end of the first year:

HJ: At upper secondary then … how much math did you do in upper secondary … did you only have the compulsory course in first grade?

H: I also had math in the second grade but I chose it as an elective course

HJ: Hm

H: I took twice as much math in second grade .. ..

HJ: You chose more math than you really needed in the second grade?

H: Yes

In response to this contradiction in Hedvig’s story, HJ queries again, verifying that she must have been interested in mathematics (in spite of her fear):

HJ: That must show interest

H: Yes, but I was interested … I liked it but I was so afraid [så redd].

Here, Hedvig picks up and appropriates HJ’s introduction of the idea of interest, extending its use in their storying of her apparently contradictory behaviour to supply a forceful contrast between her interest and her accompanying fear.

4.3 A resolution and a hero emerges

The complication in the story that is raised by Hedvig appears to demand a resolution, and she offers this now with a new emerging self-authoring in which she draws on battle motifs and an account of inner struggle with herself and an embodied disposition to do the mathematics that was somehow “in her”. Here, we present the whole of what she says in the original Norwegian, since the complexity of the ideas and the implicit references to both mathematics and the fear within her make it difficult to translate:

H: Det var hele tida den kjempinga [battle] at jeg hadde på en måte lyst til det var hele tida det som lå i meg [in me] jeg hadde på en måte så lyst til å … å klare det .. å komme ut av det for at jeg kjente at lå veldig sånn i meg liksomFootnote 1

Later, she talks about barriers, and the context of the conversation so far suggests that these are internal to her. HJ’s questions lead her to clarify that fear creates a barrier:

H: … I had these barriers [sperrene] all the time

HJ: It was sort of a double

H: Yes

HJ: Both happiness [glede] and a little anxious [litt angstfylt]

H: Yes, fear [frykt], I think

She continues the theme of a battle within, rejecting (not for the first time) HJ’s offered opening for an explanation for her anxiety in terms of her past experience of schooling. Instead, she once again asserts her agency in the discussion by introducing and drawing on a genre of inner struggle, employing again the metaphor of struggle in battle, as she goes on to talk about her experience of studying the compulsory component of mathematics in her teacher education at the university. She explains to HJ that she feared mathematics when she started her studies but, nevertheless, she persisted in her attraction to the subject, fighting what she now describes as angsten [the angst, a thing/object, with the definite article as distinct from indefinite ‘angst’]:

HJ: But do I understand you in the sense that there is nothing in .. in your schooling either in primary or secondary where mathematics ….

H: No I think in a way that … ehm … (shy laughter) it probably sounds strange but I think … I thought really [synes egentlig] that it was fun [gøy], because it is me that in a way has chosen to continue and at the same time I got in a way this [den derre]—you could call it …. the angst [angsten] so …

HJ: Hmmmm

H: And really really struggled [sleit veldig veldig mye] with that .. and especially connected to … performance [prestasjon da]… evaluation [vurdering].. and in a way I chose that I did not want to have it [the angst] this way any more [jeg ikke ville ha det sånn lengre da] so therefore I chose just to go on … I worked very, very hard with math [jeg jobba veldig veldig mye med matte] ..

HJ: Hmm

H: And then it [the angst] decreased a bit in a way and I liked [likte] that very much and continued ..

HJ: Maybe a small victory [liten seier] ..

H: (Again shy laughter) Yes maybe ..

In her assertion of refusal to suffer the fear—“I chose that I did not want to have it [the angst] this way any more…. I worked very, very hard with math….”—and in her earlier reference to barriers within, Hedvig can be read as appropriating a therapeutic genre of resistance to inner struggle to address HJ. She thus expresses agency in her self-authoring in terms of her narrative of an ultimately successful struggle between inner selves, and the multiple voices of those selves.

Continuing in the same genre of inner struggle, Hedvig talks more about her battle with the bad feelings inside her which made her feel she was unable to do mathematics at the same time that it was part of her; she tells HJ how she worked hard (literally, with lots of fight), but then introduces a hero in the shape of one of her university tutors who showed her the way to see struggling to understand mathematics as normal and even necessary:

H: It was then [at university] it happened … it was then I chose math … or the first year then .. then I felt … I have had 2 years with math .. but the first year I was really conscious [så kjente jeg veldig på det] of it … the bad feelings about math [det vonde med matte], yes … that I did not feel good enough and yes … and maybe not smart enough or yes … so then I worked lots and fought hard [jobba jeg masse kjempa mye] and then I met Terje then ..

HJ: Yes

H: It was he who really inspired me ..

H: Yes because in a way he made it so harmless [så ufarlig] and .. I like [liker] to work with math, I did think it was fun … yes I liked it so in a way he made it so harmless [ufarliggjorde det] and made it ok [greit]… that it was ok [greit] not to understand at once and that in a way it was very important that you had to go through these processes [i.e. not understanding] in a way.

Here, and to some extent in the previous extract, where she refers to performance and testing, Hedvig can be seen as appropriating the didaktikalFootnote 2 genres of becoming a mathematics teacher (see also Braathe, 2011). Mathematics teacher education combines mathematics for teaching and pedagogical theory related to teaching of mathematics. What is important for our analysis here is that, in Norway, mathematics as a compulsory subject in teacher education has developed a particular pedagogically focused form: since all students will eventually teach mathematics to primary school children, one of the main objectives has been to work towards developing ‘positive feelings’ towards mathematics in student teachers. As she engages with this particular didaktikal genre of positivity in the face of not understanding, appropriating the words and intentions of pedagogic theories, and hybridising these with her previous experiences, Hedvig can be read as choosing a language as she draws on the various genres which have become available in the discussion. Here, she explains her ongoing engagement with mathematics in the face of her struggle with ‘the angst’, by choosing to describe Terje as a person who made a major difference to her, resisting HJ’s offered explanations, as we elaborate next.

5 Choosing and resisting genres in the dialogic space: a site of agency

We should now apprise the reader that this study was undertaken against the background of our previous research in discourses about mathematics and, in particular, the idea that mathematics is discursively ‘masculine’, a subject which lacks a discursive space for girls and women. Now, we move to a wider focus on the dialogicality of the conversation, taking into account our own standpoint and HJ’s in particular. Looking more closely in this way, we note that although we were working from the standpoint of mathematics as masculine, on the basis of earlier work (e.g. Solomon, 2012), and although this influenced HJ in his responses, constituting part of the genre on which he drew, Hedvig was—like Mendick’s (2006) Claudia—somewhat reluctant to co-construct her story with respect to gender. In this section, we comment further on the conversation as an arena in which Hedvig not only tells a story of her own agency but asserts it in her choice of language and genre in addressing HJ.

Central to Hedvig’s story is the contradiction between her reporting of fear and angst, and her actions in taking more, and more difficult, mathematics courses than she needed to. As we have already seen, HJ is drawn into this story and co-constructs with Hedvig the bricolage of the contradiction and its explanation. However, he also offers from time to time various explanations for Hedvig’s fear, drawing on research genres of gender positioning, classroom processes and family backgrounds. The first instance of this is his introduction of a focus on gender, when he raises the issue of how many girls were in her elective academic mathematics class at school (thus implying that this could be a problem). Hedvig supplies the information that there were only two, herself and a friend (however, noting that she had forgotten this contrast in fact—“it was a majority boys… I had really forgotten”), but as the following extract shows, she resists a “gender story”:

H: ….. we could have chosen (laughs) .. makeup or hair styling or something similar, but we didn’t, we chose mathematics … no I think we both had an interest in math, she also liked math..

HJ: Mm

H: That was why we chose it, that was why we chose it … she was very clever, very kind and sweet girl

HJ: This I think is exciting because what you said a minute ago .. no I am getting curious

H: Yes

HJ: Does it mean then that the other girls in that class, that they chose maybe other subjects as for example makeup and hairstyling ..

H: I remember it because I thought it was a bit tempting also to choose for me but … we chose math

HJ: Mm but more of the others chose makeup or … very feminine subjects…… Did this create any difference between you in second grade, I mean those that were in your class?

H: Not really because we were taken out of that class

HJ: Mm

H: And we didn’t see the others

Note here that Hedvig does not pick up HJ’s suggestion about difference between herself and the other girls and, on the contrary, she explains that she had also been tempted to take these more feminine elective subjects which were more the norm in the aesthetic pathway. But having offered this idea, she rejects it in favour of a re-emphasis (“That was why we chose it, that was why we chose it”) on interest, enacting agency in this repetition of the rejection of HJ’s offer. But then she says something more, unbidden, about their relationship with the other girls:

H: No I didn’t feel … we became a bit invisible I think … not noticed in relation to this

HJ: Did you became less important in the class than those who chose makeup and hairstyling ..

H: (laughs) When you ask that way … yes … I actually think that we were not noticed … yes because yes ..

HJ: Would you say that you had less status choosing mathematics compared to choosing the typical feminine …

H: I think it is difficult to answer that, I don’t know

HJ: If you think about it …

H: I think … yes maybe one could say that it had less status, but I think most in a way didn’t … eh … even think about it at all … we were a bit invisible in a way

HJ: But were you invisible because you were rather quiet and undemanding girls …. or … what I am thinking is … who made you … what made you invisible

H: No we were, well, a bit quiet then, quiet, nice, conscientious girls

HJ: Unlike the other girls … not necessarily but

H: Yes maybe a bit

It is difficult to interpret Hedvig’s description of her invisibility here, or its generic origins, although we might speculate that she is drawing on what she knows of research in gender and mathematicsFootnote 3 (see Rodd and Bartholomew 2006). She rejects elements of HJ’s proffered explanations but reluctantly (it seems) accepts others in the end by taking up his words and their implied intentions.

Although Hedvig goes some way towards HJ’s construction of a gender story in relation to her experience of doing mathematics, she persists in her account of ‘the mathematics in her’ as the reason for her choice, even though it causes her angst. Appropriating her introduction of a genre of embodied disposition, HJ attempts to explore the role of mathematics itself in her choice but she is unable, or reluctant, to elaborate, apparently moving in the direction of rejecting the therapeutic genre she has invoked earlier on:

HJ: So then math became in a way … why did the math in this way become what you wanted to bring you out of this sense of low self-esteem?

H: Why I chose that

HJ: What is it about mathematics … could it have been a different subject?

H: No. I .. It’s as simple as I just like math .. I like to work with math .. there is really no deeper reason than that … I like it

Later, she returns to note the pressure she experienced in doing mathematics, but again says that she is unable to explain where the pressure comes from:

H: Ja jeg vil nok helst legge [under pressure] det på meg selv ja jeg gjør nok det … men jeg vet ikke helt faktorer for hvorfor det [angsten, kjempinga] ble sånnFootnote 4

At this point in the discussion, then, Hedvig tells a strong story about herself as acting rationally towards the use of mathematics, and she gives a rather dispassionate account of her invisibility among the other girls. She seems after all to have been very conscious of her choice but is reluctant to speculate about what she calls ‘deeper reasons’. One interpretation of this is that she is now drawing on a new genre of neoliberal individualism, again like Claudia in Mendick (2006), rejecting for the time being at least HJ’s proffered acceptance of the therapeutic genre. Thus, we see Hedvig’s agency as enacted through her appropriation and orchestration of the heteroglossia arising from potentially conflicting genres, but also her resistance to others, as she addresses and answers HJ in a manner which is all the more noteworthy in the context of HJ’s position as her tutor in her present master studies in mathematics education.

We also entered this research with ideas about family narratives as potential sources of voices from the past, and this again brought HJ to seek for explanations in her 'others’ that could have played a part in Hedvig’s struggle with mathematics and her contradictory act of choosing academic mathematics. He raises this idea early in the conversation, but she does not immediately incorporate a family narrative into her story at that moment:

HJ: What kind of relation would you say your parents have towards mathematics?

H: Eh .. not especially good maybe .. no .. no my grandmother was good at math .. but my parents I think … didn’t have … no not any specially bad either .. no I did most math alone .. eh ..yes ..

HJ: Was it because you did not need any help or …. that you felt that they were not able to help you or ..

H: (A shy laughter) No no … I don’t remember … eh … no I don’t know …

In this mixed response, Hedvig is again reluctant to take up HJ’s suggestions, although she offers a contrast between her parents and her grandmother. Much later, she offers more information about her family, and she elaborates on this background, returning to her overall story of ‘the mathematics in her’ and her use of the genre of (inherited) embodied disposition as she talks about other family members:

H: I have basically always been told that ‘mathematics is not for you’ [ligger ikke for deg]

HJ: Mm

H: ‘You are not good’ [Du er ikke flink] or .. Maybe it comes a bit from my mum there and .. ehm.. because .. eh .. It’s .. because it was a little odd because I met an old woman, my grandmother’s sister, in the summer because she was 80 .. and I said that I had gone on with math and then she thought it was very strange because there was absolutely no [mathematics] in anyone in our family [(matematikk) lå jo absolutt ikke til noen i vår familie] .. very strange [rart] so it is perhaps that I’ve always heard it [‘mathematics is not for you’] and then I kind of figured out pretty early on that I like math

HJ: Yes

H: Also, I have perhaps been a little stubborn [sta] and just carried on

HJ: Mm

H: In spite of what I’ve felt, what I felt when….

Here, Hedvig’s self-authoring builds on her earlier observation that she did most of her mathematics alone, and she once again draws on a narrative genre of persistence and/or resistance which is now blended with a suggestion of individualism, this time in the face of voices from the past which might have discouraged her. But these voices did not play a conspicuous part in her story, and to some extent we were struck by their absence from the story that Hedvig told, which we have described above. So again, we see agency here both in Hedvig’s story itself, but also in the telling of it to HJ.

6 Revisiting and reasserting agency

To complete our analysis of the dialogic space as a site of agency, we turn to HJ’s discussion with Hedvig 4 weeks later, after she had read a first draft of this paper, up to this point. Pursuing our theme of recognising HJ’s standpoint, we return here to what appeared to us to be the crux of her story, that is, Terje’s role in taking away her fear of mathematics. As we have noted above, Hedvig portrays Terje as someone who made mathematics ‘harmless’ [ufarlig]. HJ, however, wanted to return to the theme of the central objective of teacher education and the potential impact this might have had on Hedvig’s contradictory relationship with mathematics. He refers to the earlier discussion in the paper where we have suggested that Hedvig is appropriating didaktical genres and that this is one of the voices in her story, following through his idea that mathematics is different at the university and so would have changed her history:

HJ: The next thing we do is to argue that you are using didaktical genres to explain why Terje changed your views on mathematics …. since you met him in the context of teacher education.

H: Yes

HJ: That [didaktical genres] becomes one of many voices … can I say that?

H: Yes, yes … he turned it to something positive for me … so for sure … but again it’s difficult for me to point to something …

HJ: But would you say that the fact that you started here and had mathematics in your teacher education that … would you say that the mathematics you met here was different … that that to some extent changed your history about mathematics?

H: The mathematics as such is the same I would say but … I will say again that it was Terje as a person … that … maybe I didn’t feel as stupid with him or ..

Here, we see Hedvig rejecting once again the idea that it is the university approach which has contributed to the change in her feelings about mathematics. The mathematics for her is ‘the same’ and she is forceful in returning to the importance of Terje as a person. This is reinforced later when HJ asks her about the other staff, suggesting that they might have been equally important:

HJ: mm … but I hear you saying that it’s really Terje as a person who is the one that … so do you think I should underline that more in what we are writing … because it looks like I’m putting him as a person in the background somewhat … because you have experienced other teachers here as well ..

H: Mm ..

HJ: and you didn’t experience them in the same way as you did Terje

H: no I did not (laughter) .. no I didn’t ..

Following her emphatic rejection of this idea, Hedvig re-tells the story of Terje as someone who enabled her to win the battle against her own fear, demonstrating the sustained nature not only of this central element of her narrative but also of her agentic appropriation of genres in the space of the interview:

HJ: You are very clear in stating that ‘he made it so harmless …’

H: Yes he was just … Terje was very organised and calm and patient [veldig strukturert og rolig og tålmodig]…

HJ: mm ..

H: … and … it was simply safe [trygt], it was safety [trygghet] …

7 Conclusion: identity and agency within narratives of choosing mathematics

Bakhtin’s dialogism entails that we represent ourselves to ourselves from the vantage point (the words) of others and that those representations are significant to our experience of ourselves: as we have noted, consciousness is otherness. This emphasis on the self as inextricably related to others underlines how unlikely it is that one’s identities are ever fixed or completed. Dialogism makes it clear that what we call identities remain embedded in social relations and material conditions. If these relations and material conditions change, they demand new ‘answers’, and old ‘answers’ about who one is may be undone. But the essential addressivity of our lives also makes it clear that there is a room for agency, and the avoidance of total determination by structuring discourses through the continual appropriation and orchestration of the cultural resources that are available to us. Thus, agency is underpinned by the appropriation of genre for meaning-making, imbued with the intentions of others but also available to remoulding to ‘one’s own intentions and accents’ (Bakhtin, 1981, p. 294).

Our use of dialogism in the analysis of Hedvig’s story of choosing mathematics has enabled us to open up an exploration of choice which avoids a reliance on structural and structuring discourses which appear to fix the individual in time. This is not to say that such discourses are not powerful, but that a recognition of how individual agency is enacted through the appropriation of cultural resources—here, the genres drawn on in the narrative of the self—enables us in the interview to see more clearly how individuals orchestrate the multiple strands of an account of choice. The tools of analysis which Bakhtin provides thus enable an understanding of how choice is expressed, and they also underline the emergent nature of identity in discussion, as part of an ever-becoming self—we might say that, in Black and Williams (2013) terms, we have uncovered the semiotic action within Hedvig’s reflections in concert with HJ as she explores and orders the contradictions of her choosing mathematics.

Our analysis here has some implications on how we may understand choice and participation in mathematics and their interpretation in the interview. As we have shown, the conversation between HJ and Hedvig includes a number of twists and turns, in which the addressivity of their talk is not merely a question of clarification of Hedvig’s prior choices but is productive of her emergent self, in which she is choosing genres, not just mathematics. In her own story, and in her commentary on our stories, we hear Hedvig’s assertion of ‘I’ as she positions herself clearly in relation to HJ by both rejecting and accepting the explanations and genres that he offers. She answers his offerings by invoking multiple genres—psychological, therapeutic, didaktic, gender positioning and embodied characteristics—in her self-authoring and in her assertion of agency. According to our co-stories with Hedvig, Terje made it possible for her to address her fear and to author herself as a mathematical person. But the problem remains, as do the ambivalences in her choice of mathematics and, we argue, she will appropriate these and other genres as she continues to position herself by answering and addressing others in her ongoing becoming. Choice is complex, a bricolage of stories of the self and others. In contrast to many accounts of choosing in mathematics, our focus on agency as choice of genre shows how the expression of a mathematical identity is never fixed or complete; as long as individuals may encounter and appropriate new cultural resources, the possibility of giving another account of themselves in relation to mathematics remains.

Notes

H: It was always the battle [kjempinga], that I had in a way wanted to do it [i.e. math] … it [the mathematics] was always in me, I always wanted to do it… to make it…. To get it [the fear] out of me because it [the mathematics] was in me in a way….

We use this spelling of didaktical to denote a meaning of the word which is different to its understanding in British English. This spelling indicates the German/Nordic usage which emphasises the holistic study of education including its ideological underpinnings.

It is appropriate to say here that the subject of gender and mathematics had recently been discussed in the master in mathematics education class.

H: Yes I put myself under pressure [by doing mathematics], I do that … but I don’t know the reasons for why it [the angst, struggle] became this way.

References

Atweh, B., Graven, M., Secada, W., & Valero, P. (Eds.). (2011). Mapping equity and quality in mathematics education. Dordrecht: Springer.

Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays by M.M. Bakhtin. (C. Emerson & M. Holquist, Trans.). Austin: University of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1986). Speech genres and other late essays. (V. W. McGee, Trans.). Austin: University of Texas Press.

Black, L., & Williams, J. (2013). Contradiction and conflict between ‘leading identities’: Becoming an engineer versus becoming a ‘good Muslim’ woman. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 84(1), 1–14.

Braathe, H. J. (2010). Communicative positionings as identifications in mathematics teacher education. In V. Durand-Guerrier, S. Soury-Lavergne, & F. Arzarello (Eds.), Proceedings of CERME 6. Proceedings of the Sixth Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education (pp. 925–933). Lyon, France: Institut National de Recherche Pedagogique.

Braathe, H. J. (2011). Negotiating mathematics teacher identities. Paper presented at the Mathematics and Contemporary Theory Conference, Manchester, UK. Retrieved from http://www.esri.mmu.ac.uk/mect/papers-list.php

Braathe, H. J., & Ongstad, S. (2001). Egalitarianism meets ideologies of mathematics education—instances from Norwegian curricula and classrooms. Zentralblatt fur Didaktik der Matematik, 33(5), 1–11.

Cooper, B. (2001). Social class and “real-life” mathematics assessments. In P. Gates (Ed.), Issues in mathematics teaching (pp. 245–258). London: Routledge.

de Abreu, G., & Cline, T. (2007). Social valorization of mathematical practices: The implications for learners in multicultural schools. In N. S. Nasir & P. Cobb (Eds.), Improving access to mathematics: Diversity and equity in the classroom (pp. 118–131). New York: Teachers College Press.

Early, R. E. (1992). The alchemy of mathematical experience: A psychoanalysis of student writings. For the Learning of Mathematics, 12(1), 15–20.

Forgasz, H., & Rivera, F. (Eds.). (2012). Towards equity in mathematics education: Gender, culture, and diversity. New York: Springer.

Holland, D., Lachicotte, W., Jr., Skinner, D., & Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Holquist, M. (2002). Dialogism: Bakhtin and his world (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Martin, D. (2007). Mathematics learning and participation in the African American context: The co-construction of identity in two intersecting realms of experience. In N. S. Nasir & P. Cobb (Eds.), Improving access to mathematics: Diversity and equity in the classroom (pp. 146–158). New York: Teachers College Press.

Mendick, H. (2005a). A beautiful myth? The gendering of being/doing “good at maths”. Gender and Education, 17(2), 203–219.

Mendick, H. (2005b). Mathematical stories: Why do more boys than girls choose to study mathematics at AS-level in England? British Journal of Sociology of Education, 26(2), 225–241.

Mendick, H. (2006). Masculinities in mathematics. Berkshire: Open University Press.

Noyes, A. (2007). Mathematical marginalisation and meritocracy: Inequity in an English classroom. The Montana Mathematics Enthusiast, Monograph, 1, 35–48.

Rodd, M., & Bartholomew, H. (2006). Invisible and special: Young women’s experiences as undergraduate mathematics students. Gender and Education, 18(1), 35–50.

Solomon, Y. (2012). Finding a voice? Narrating the female self in mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 80(1–2), 171–183.

van Enk, A. A. J. (2009). The shaping effects of the conversational interview: An examination using Bakhtin’s theory of genre. Qualitative Inquiry, 15(7), 1265–1286.

Walls, F. (2009). Mathematical subjects: Children talk about their mathematics lives. Dordrecht: Springer.

Wertsch, J. V. (1993). Voices of the mind. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Winter, J., Salway, L., Yee, W. C., & Hughes, M. (2004). Linking home and school mathematics: The home school knowledge exchange project. Research in Mathematics Education, 6(1), 59–75.

Zevenbergen, R. (2001). Language, social class and underachievement in mathematics. In P. Gates (Ed.), Issues in mathematics teaching. London: Routledge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Braathe, H.J., Solomon, Y. Choosing mathematics: the narrative of the self as a site of agency. Educ Stud Math 89, 151–166 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-014-9585-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-014-9585-8