Abstract

Textbooks currently include many elaborations that describe, illustrate, and explain main ideas, increasing the length of these textbook chapters. The current study investigated if the cost in additional reading time that these elaborations impose is outweighed by benefits to memory for main ideas. Given that elaborations in textbooks sometimes fail to produce memory benefits, the current study also investigated if the reason is that less time is spent reading main ideas sentences in elaborated versus unelaborated texts. In two experiments, participants read a textbook passage with just the main ideas or with these main ideas and elaborations. Two days later, participants completed tests of their memory for the main ideas. Conceptually replicating previous research, elaborations did not provide a memory benefit commensurate with the time cost they imposed. Results also indicated that the lack of benefit is at least partially attributable to less time spent reading main ideas for the elaborated versus unelaborated text. To further investigate why students spent less time on main idea sentences, Experiment 2 provided evidence that this difference may be due to difficulty discriminating main ideas from elaborations while reading. In sum, textbook elaborations may impair memory for main ideas due to less time spent on these main ideas despite the large overall time cost imposed; thus elaborated texts can be less effective than unelaborated texts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Textbook chapters are typically lengthy. Only a small proportion of chapter content includes main ideas, which are presumably the targets of learning. In contrast, a large proportion of chapter content includes elaborations. Elaborations included in textbooks involve details that are meant to describe, illustrate, or explain main ideas. Including these elaborations necessarily increases text length, and longer texts will presumably require more time for students to read. Given that students have limited time to devote to learning, an interesting and important question arises: Do students benefit from spending some of this time reading the elaborations included in textbooks (for brevity hereafter we refer to elaborations that are included in textbooks as textbook elaborations)? Prior research fails to address this question definitively. Therefore, the current study further investigated the costs and benefits of textbook elaborations. Importantly, the current research also extended beyond previous research to investigate why textbook elaborations sometimes fail to enhance learning.

As the question above suggests, both costs and benefits are relevant to our evaluation of textbook elaborations. Concerning the potential benefits of textbook elaborations, the learning outcome of interest here is students’ memory for the main ideas. Concerning the costs of textbook elaborations, the outcome of interest is the amount of time students spend reading the version of a text with versus without the textbook elaborations. Time cost is an important outcome because students have limited time to devote to learning, and they often have a lot of materials to learn. If students spend more time reading but achieve the same level of learning of the main ideas with both versions, then reading the elaborated version is not an effective use of their limited time. Instead, students could devote the additional time that they would spend reading the elaborated version to learning other materials (for further discussion of this cost/benefit approach, see Daley and Rawson 2019; Zamary and Rawson 2018). Although both time costs and memory benefits are arguably important outcomes for evaluating the effectiveness of textbook elaborations, research examining either outcome is surprisingly limited. The purpose of the current research was to further examine time costs and memory benefits and to test a hypothesis for why textbook elaborations sometimes fail to benefit memory for main ideas.

Research on the Effects of Elaborations in Expository Text

Because textbooks commonly include elaborations, one might expect them to have a robust effect on memory for main ideas. Consistent with this possibility, Freeman (1985) notes that elaborations may provide additional retrieval routes that readers can use to recall the main ideas. Elaborations may provide these additional routes if the student connects these elaborations to the main ideas while reading the text. During subsequent retrieval, the student can then use these elaborations to access the main ideas. Based on these considerations, memory for main ideas in textbook passages will be greater with versus without elaborations. However, the weight of empirical evidence does not support this possibility.

Although a number of studies have examined the effects of elaborations in learning fact lists (e.g., Di Vesta and Finke 1985; Pressley et al. 1987; Stein et al. 1984; Stein et al. 1978), we focus our review of the research examining memory benefits to studies involving expository texts because this is the genre included in most textbooks. Few studies to date have investigated whether elaborations in expository text benefit memory for main ideas (Allwood et al. 1982; Daley and Rawson 2019; Dal Martello 1984; Freeman 1985; Mohr et al. 1984; Palmere et al. 1983; Phifer et al. 1983; Reder and Anderson 1980). Some of these studies demonstrated greater memory for main ideas following study of elaborated versus unelaborated texts (Dal Martello 1984; Freeman 1985; Mohr et al. 1984; Palmere et al. 1983; Phifer et al. 1983). In contrast, other studies showed either the reverse pattern of results or similar memory performance following both versions (Allwood et al. 1982; Daley and Rawson 2019; Reder and Anderson 1980). Overall, these studies do not provide consistent support for the expectation that textbook elaborations enhance memory for main ideas.

Importantly, conclusions about the effects of textbook elaborations are limited both by the scarcity of research and by some methodological limitations in much of this work (for details, see Daley and Rawson 2019). In brief, in some of these studies, the wording of the main ideas was not held constant across the elaborated and unelaborated versions of the text. Additionally, most of these studies involved initial reading and testing in a single session. Immediate testing limits prescriptive conclusions based on these studies, given that longer delays between study and test are more typical in educational settings. Furthermore, in all but one of the prior studies, the amount of reading time was determined by the experimenter. In contrast, students in authentic educational contexts would typically pace their own reading of a textbook passage. The memory benefits of textbook elaborations with self-paced study are thus unclear.

Experimenter pacing is particularly problematic for current purposes because it prohibits the estimation of time costs. In the only study that used a self-paced procedure (Daley and Rawson 2019), participants read text passages from psychology textbooks. These texts either contained the main ideas alone or contained those main ideas along with elaborations originally included in the textbook. Importantly, students self-paced their reading to afford estimation of the time cost imposed by the textbook elaborations. Two days later, participants completed tests of their learning of the main ideas. The primary outcomes of interest were time spent reading the text and cued recall of the main ideas. Time spent reading was greater for the elaborated text versus the unelaborated text (d = 1.00), whereas cued recall performance was similar for both versions (d = − .08). Based on these results, including textbook elaborations with the main ideas appears to be an inefficient way for students to learn main ideas. However, the outcomes of one study are insufficient for making prescriptive conclusions. Accordingly, one important purpose of the current research was to conceptually replicate this study with different textbook materials. In particular, the prior study involved two textbook passages that both involved an enumeration structure listing various facts and concepts. Enumeration structures are only one of the several text structures that scientific textbooks commonly employ (Cook and Mayer 1988). We thus designed the current study to generalize the key findings to an expository text with a different structure, by using a text with a sequence structure (i.e., a text that describes the connected set of steps involved in a process or system).

Reduced Attention Hypothesis

In addition to awaiting replication of previous work, clear prescriptive conclusions also await a better understanding of why textbook elaborations sometimes fail to enhance student memory for the main ideas. As noted above, the intuitive expectation that textbook elaborations enhance learning of main ideas seems reasonable. However, initial evidence suggests that textbook elaborations may fail to enhance memory for main ideas. Why might this counterintuitive finding occur? We propose the reduced attention hypothesis, which states that the textbook elaborations fail to enhance learning because they decrease the amount of time students spend reading the main ideas. This reduced attention may result for several reasons. For instance, students may find the textbook elaborations interesting and thus spend time reading these textbook elaborations at the expense of the main ideas. Students may also have difficulty identifying the main ideas when they are presented along with the textbook elaborations in a single passage. Regardless of why the textbook elaborations might have this effect, less time spent on the main ideas implies fewer attentional resources spent on encoding those main ideas. This reduction in attention may cancel out any of the positive benefits the textbook elaborations might have on memory for the main ideas, or even outweigh any benefits to yield lower memory for the main ideas.

Although the reduced attention hypothesis awaits direct evaluation, indirect evidence consistent with this hypothesis stems from additional analyses we conducted on the data from Daley and Rawson (2019, Experiment 2). For each participant, we computed the total time spent reading a text across initial reading and rereading. We then divided their total reading time by the length of the text that they read to compute overall average time spent per word. Students spent approximately half the time per word while reading the elaborated versus unelaborated version (M = 0.4 versus 1.1 s per word). Lower average time per word for the elaborated versus unelaborated version is consistent with the reduced attention hypothesis, which predicts lower reading time for main ideas in the text with versus without textbook elaborations. Of course, students reading the textbook passages with elaborations in this study could have strategically allocated more time to main ideas and skimmed the elaborations, resulting in less time per word on average but not necessarily less time on main ideas in particular. This previous study does not afford a direct examination of whether reading time for main ideas in particular was lower for the elaborated versus unelaborated text, due to the way in which the text was presented. In this prior study, each screen displayed a paragraph of the text containing both main ideas and elaborations, and reading time was recorded for the entire paragraph. To isolate reading times for main idea sentences, the current study displayed the text one sentence at a time.

Overview of Current Research

In two experiments, participants read a textbook passage with ten main ideas. In the first session, participants read the text either with just the main ideas or with the main ideas and the elaborations. The text was presented either one paragraph at a time (Experiment 1) or one sentence at a time (Experiments 1 and 2). Reading was self-paced to assess the overall time spent reading each version of the text. Two days later, participants completed recall and short answer tests of memory for the main ideas. For both experiments, we preregistered the hypotheses, procedures, and data analysis plans on the Open Science Framework (osf.io/kr92q).

To revisit, we designed the current study to accomplish two goals: (1) conceptual replication to examine further the costs and benefits of textbook elaborations, and (2) novel extension to investigate a theoretical account for why textbook elaborations sometimes fail to enhance learning. Concerning our first goal, the relevant outcomes were overall time spent reading and memory for the main ideas. Based on the outcomes of Daley and Rawson (2019), we expected that overall reading time would be greater for the elaborated versus unelaborated version of the text. We also expected that performance on the memory tests would be similar for the elaborated versus unelaborated version. Concerning our second goal, the relevant outcome was the time spent reading the main idea sentences. The reduced attention hypothesis predicts less time spent on main idea sentences for the elaborated versus unelaborated version of the text. To foreshadow, the results of Experiment 1 confirmed this prediction. Experiment 2 replicated this result and further investigated why students spend less time reading the main idea sentences in the elaborated versus unelaborated version. Specifically, Experiment 2 evaluated the hypothesis that students have difficulty identifying the main ideas when a text also contains elaborations.

Experiment 1

Experiment 1 aimed to conceptually replicate Daley and Rawson (2019) and to evaluate the reduced attention hypothesis. Based on these aims, we randomly assigned participants to one of the four groups based on a factorial combination of two variables, text version (elaborated versus unelaborated) and presentation (sentence versus paragraph). The paragraph presentation groups provide a conceptual replication of Daley and Rawson’s (2019) procedure. The sentence presentation groups extend beyond the prior study to provide a measure of time spent on the main idea sentences in particular, to evaluate the reduced attention hypothesis. Experiment 1 also included a fifth control group that provided estimates of the functional floor and ceiling for our memory measures (described further below). The purpose of the control group was to rule out the possibility that the similar performance we originally anticipated for the elaborated and unelaborated text groups reflected functional ceiling or floor effects (cf. Daley and Rawson 2019).

Method

Participants and Design

Participants included 169 undergraduate students at Kent State University (81% female 79% white, 15% black, 3% Asian, 5% first nations, 1% native Hawaiian, 4% Hispanic or Latino); 44% were first-year college students (M years in college = 2.0, SE = 0.1) and 27% were psychology majors. Participants were 19.6 years old on average (SE = 0.1, range = 18–31). We recruited all participants from the Psychology Department participant pool, and they received course credit. Data from 15 participants were excluded from analyses due to failure to return for Session 2 (n = 13), a computer malfunction (n = 1), and non-compliance (i.e., they spent less than 1 s on one or more pages of the text; n = 1). The final sample included 154 participants. For the sentence presentation groups, the final sample sizes were 49 for the unelaborated group and 44 for the elaborated group. For the paragraph presentation groups, they were 19 for the unelaborated group and 20 for the elaborated group. The control group included 22 participants. Our targeted sample sizes were 51 in each of the sentence presentation groups and 21 in each of the paragraph presentation groups and the control group. We determined targeted sample sizes based on a priori power analyses using G*Power software (Faul et al. 2007). Details regarding these power analyses are included in our pre-registration on Open Science Framework. In brief, we targeted smaller sample sizes in the conceptual replication groups (i.e., paragraph groups) and the control group due to large effect sizes for overall reading time in previous work. Specifically, for the paragraph groups, we ran an a priori power analysis to detect a large effect based on prior work (d = .8) with power set at .80 and alpha = .05 for a one-tailed between subjects t test. Additionally, the sample size of 21 participants in the control condition affords sufficient power to detect medium effects (d ≥ .58), based on a sensitivity analysis using G*Power for one-tailed, independent samples t test with an alpha level of .05 and .80 power. In contrast, we targeted larger sample sizes in the sentence presentation groups to detect a medium effect due to the lack of previous work examining differences in time spent reading main idea sentences. Specifically, we ran an a priori power analysis to detect a medium effect (d = .5) with power set at .80 and an alpha = .05 for a one-tailed between subjects t test.

Materials

The current study included an unelaborated and elaborated version of a text on the process of hearing. Both versions of the text included ten main ideas. We define the main ideas for this topic as information that is important for describing the process of hearing. To identify the important information, we examined the overlap in content describing the process of hearing across ten undergraduate-level psychology textbooks (Carlson 2008; Franzoi 2002; Kalat 2004; King 2008; Lahey 2009; Lilienfeld et al. 2009; Myers 2010; Schacter et al. 2009; Wade and Tavris 2004; Wolfe et al. 2008). The main ideas we selected were included in at least eight of the ten textbooks (M = 9.5 out of the 10 textbooks on average). For instance, the main idea sentence describing the first step in the process of hearing stated, “A sound wave passes into the outer ear, also known as the pinna.” We then organized the remaining content in these textbooks by main idea. Across the ten textbooks, we found at least three sentences related to each of the main ideas. As a result, we selected three elaboration sentences for each of the main ideas (for consistency in support across the main ideas), for a total of 30 textbook elaborations. In contrast to the main ideas, the majority of these sentences were contained in only one text. For instance, one of the elaborations stated, “The ossicles were named for their appearance and fit together into a lever.” The full material set can be obtained from the first author upon request.

After selecting this information, we created two versions of a text on the process of hearing. Neither version included images, figures, nor citations. The first sentence for both versions of the text was an introductory sentence. After that sentence, the unelaborated version of the text contained ten sentences conveying each of the ten main ideas we selected. The elaborated version of the text contained these ten sentences and 30 sentences conveying each of the selected elaborations. Each main idea sentence was followed by the three elaboration sentences corresponding to that main idea. All 40 sentences were extracted from the original textbook materials, with some minor editing of wording for clarity and flow. The elaborated version of the text was 837 words, and the unelaborated version was 192 words. The text involves copyrighted material and thus is not included here, but all material can be obtained from the first author upon request.

Procedure

In both sessions, participants sat at individual stations and a computer presented all tasks and instructions. In the first session, participants in the control group completed the final tests without reading either version of the text to provide a measure of the functional floor for performance on these tests. After completing these tests, they were dismissed. Participants in the experimental groups were told that they would be asked to learn information from a textbook and that they would be tested on the material in the following session. Next, they read their assigned version of the text. For the paragraph presentation groups, each screen displayed one paragraph of information. The unelaborated version of each text was broken up into three screens and the elaborated version into six screens. For the sentence presentation groups, each screen displayed one sentence of information (11 screens for the unelaborated version and 41 screens for the elaborated version). At any point, participants could press a button to go forward to the next screen or another button to go back to the previous screen. On the last screen of the text, they also had the option to start over from the beginning. At the end of the text, a textbox required participants to verify that they were completely done reading the text before moving on to the next task. In all groups, reading time on each screen was self-paced. The computer recorded the amount of time spent reading each screen of the text.

After reading the text, participants made a series of ratings. First, participants rated, “How difficult did you find this text on a scale of 1–100? (1 = very easy and 100 = very difficult).” Then, participants rated, “If this text was assigned reading for a class you were taking, how likely is it that you would actually read the text? (1 = very unlikely and 100 = very likely).” Finally, participants rated, “How interesting did you find this text on a scale of 1–100? (1 = very uninteresting and 100 = very interesting).” After completing these ratings, participants made a global learning judgment for the text. Participants indicated, “How much will you remember about the process of hearing on the tests two days from now? (1 = none of the information that was in the text and 100 = all of the information that was in the text).”

Participants returned 2 days later to complete the final tests. All tests were self-paced. First, participants took a recall test of memory that asked them to explain the process of hearing in as much detail as possible. They typed their response into an entry box. If the student failed to type anything into the entry box, a pop-up appeared that stated “Please try your best to enter a response. If you can’t remember anything, type ‘I don’t know’.” Participants could only move onto the next test after typing something into the entry box. Next, they completed 13 short-answer questions that further tapped memory for the main ideas. For the full set of short-answer questions see Appendix A. A pop-up prompted participants to type in a response if the entry box was left empty. After the short answer test, they completed eight multiple-choice questions tapping comprehension of the main ideas. Each multiple-choice question included four alternatives. For both the short answer and multiple-choice tests, questions were presented one at a time in a fixed, random order to all participants. All three tests were closed-book for those in the experimental groups. In contrast, participants in the control group completed all three tests in an open-book format during the second session. For these open-book tests, participants received a printed copy of the text. They had access to this text throughout all of the tests and were encouraged to refer to the text material to help them answer questions correctly. They were randomly assigned to receive the unelaborated (n = 10) or elaborated (n = 12) version of the text during these open-book final tests. After the final tests, all participants were asked a yes/no question about whether they had learned about the process of hearing in a prior course. Additionally, they were asked, “How much did you know about the process of hearing prior to this experiment (1 = I knew nothing and 100 = I knew everything).” Finally, all participants completed demographic information.

Scoring

For recall scoring, we parsed each of the ten main idea sentences into idea units, resulting in a total of 25 idea units. For instance, the main idea sentence noted above included two main idea units, “sound waves passes into the outer ear/pinna” and “outer ear known as pinna.” The 25 idea units parsed from the main idea sentences were counted as equally important and unweighted because each idea unit corresponded to a separate target idea. Trained raters scored the percentage of idea units recalled by each participant. Raters scored both verbatim recall and close paraphrases as correct.

For short answer scoring, all questions could be answered in one word or a small number of words. Thus, for most questions, trained raters scored each response as either fully correct or incorrect based on the scoring key. For the three questions with answers containing two idea units, partial credit was also available (i.e., responses with one of two idea units received half a point). Although the text contained 10 main ideas, some of the main ideas afforded more than one question, resulting in a total of 13 short answer questions. Results remained the same when we equally weighted scores for the main ideas versus average results across the 13 questions. Thus, we present the results averaged across the 13 questions below.

For both recall and short answer scoring, two raters scored sets of responses from 20 to 40 participants to check interrater reliability (rs > .97). Given the high interrater reliability, one rater scored the rest of the responses for each test. Thus, all responses for all participants in the current experiment and Experiment 2 were scored for analysis. Additionally, given that the same research assistants scored the data in each experiment using the same scoring key, we only examined inter-rater reliability in the first experiment. Additionally, internal reliability for the short answer test was high (α = .88).

For the multiple-choice comprehension test, we excluded trials in which a participant responded in less than 1 s from analyses (based on the length of the questions, participants could not reasonably read the question and select a response in less than 1 s). Internal reliability for the comprehension test was low (α = .36).

Results and Discussion

For all t tests, we computed Cohen’s d using pooled standard deviations. For outcomes involving reading time (i.e., overall reading time and reading time for main idea sentences), we recorded the number of seconds each participant spent reading each page of the text or each sentence. For each participant, we calculated overall reading time for the entire text as the total for all pages or sentences, including initial reading and any rereading. We also calculated mean time spent reading the main idea sentences for those in the sentence groups, including initial reading and any rereading. We excluded outliers from analyses below. We identified outliers in two phases. First, for each participant, we excluded any trial with a reading time that was three standard deviations or more from that participant’s mean trial reading time. Based on this criterion, we excluded less than 2% of trials. Second, within each group, we excluded data for any participant that had a mean reading time that was three standard deviations or more from that group’s mean reading time. As a result, we excluded three participants from analyses of total reading time and two participants from analyses of main idea sentence reading time.

Preliminary Results

We first examined self-reported prior exposure to the process of hearing. The proportion of people indicating that they had learned about the process of hearing in a prior class were as follows: unelaborated-paragraph (26%), elaborated-paragraph (30%), unelaborated-sentence (39%), elaborated-sentence (14%), and control (62%). Binary logistic regression was run to predict reported prior learning based on group, with the control group used as the reference group. Learning about the process of hearing in a previous course was coded as 1 and not learning was coded as 0. The overall model was significant, χ2 (4) = 16.67, p = .002. The control group was more likely to report having previously learned about hearing than those in the unelaborated-paragraph group (Wald X2 = 4.85, p = .028), the elaborated-paragraph group (Wald X2 = 4.04, p = .045), and the elaborated-sentence group (Wald X2 = 13.43, p < .001). The greater proportion of students self-reporting prior exposure in the control group potentially reflected a source monitoring error, given that they had been exposed to the target content during the open book test. However, groups did not differ in their ratings of how much they knew about the process of hearing prior to the experiment, F(4, 149) = 1.23, p = .302, MSE = 479.42, ηp2 = .03.

We next examined test performance in the control group. To revisit, performance in the control group was intended to provide estimates of the functional floor/ceiling for each measure (i.e., floor = performance on the tests in Session 1, ceiling = performance on the open-book tests in Session 2). Floor and ceiling performance was 1% and 31% for recall, 13% and 81% for short answer, and 54% and 71% for the multiple-choice test. For the recall and short answer measures, performance in the experimental groups was off the functional floor and ceiling (ts > 2.9). For the multiple-choice test, performance in the experimental groups was the same as the functional floor (54% versus 54%). Given this problem with restricted range coupled with the low level of internal reliability reported above, outcomes based on the multiple-choice test are not interpretable. For this reason, we do not discuss this measure further, and we dropped this measure from Experiment 2. Results from this measure are presented in Appendix B for completeness, but caution is warranted in interpreting these results.

Primary Results for Goal 1: Estimate the Costs and Benefits of Textbook Elaborations

As is clear from inspection of Fig. 1, textbook elaborations imposed a large time cost for overall reading time, replicating a key outcome of previous research. A 2 (version: unelaborated, elaborated) × 2 (presentation: sentence, paragraph) ANOVAFootnote 1 on overall reading time indicated only a main effect of version, with greater overall time spent reading the elaborated versus unelaborated version, F(1, 125) = 42.36, p < .001, MSE = 35,606.76, ηp2 = .25. Neither the main effect of presentation nor the interaction was significant (F = 2.46 and F < 1, respectively).

Experiment 1. Mean time spent reading the entire text, including initial reading and rereading. Paragraph = the group that read the text presented one paragraph at a time. Sentence = the group that read the text presented one sentence at a time. Unelaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included just the main ideas. Elaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included both main ideas and elaborations. Error bars reflect standard errors

Do the benefits of textbook elaborations outweigh these costs? As in prior research, the answer in the current study is no. As Fig. 2 shows, memory for main ideas was lower following the elaborated versus unelaborated version. A 2 (version: unelaborated, elaborated) × 2 (presentation: sentence, paragraph) ANOVA on recall performance indicated only a main effect of version, F(1, 128) = 11.03, MSE = 231.20, p = .001, ηp2 = − .08. Neither the main effect of presentation nor the interaction was significant (Fs < 1). Likewise, a 2 × 2 ANOVA on short answer performance indicated only a main effect of version, F(1, 128) = 8.75, MSE = 322.01, p = .004, ηp2 = − .06. Neither the main effect of presentation nor the interaction was significant (Fs < 1).

Experiment 1. Mean performance on the short answer and recall posttests. Paragraph = the group that read the text presented one paragraph at a time. Sentence = the group that read the text presented one sentence at a time. Unelaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included just the main ideas. Elaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included both main ideas and elaborations. Error bars reflect standard errors

Based on the results of previous research, we expected that performance on the memory tests would be similar for the elaborated version versus the unelaborated version of the text. Although the detrimental effect of textbook elaborations was unexpected, these results nonetheless support the same conclusion from previous research that textbook elaborations do not provide a memory benefit commensurate with the time cost they impose. Nevertheless, given the novelty of this negative effect of textbook elaborations on memory for main ideas, an important purpose of Experiment 2 was to replicate this result.

Primary Results for Goal 2: Evaluate the Reduced Attention Hypothesis

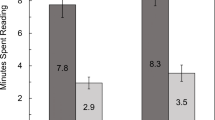

Why did textbook elaborations fail to enhance memory for the main ideas? According to the reduced attention hypothesis, this result is due to students spending less time on main ideas when reading the elaborated versus unelaborated text. To test this prediction, we computed the total time spent reading sentences that contained main ideas (combined across both initial reading and any rereading). As a reminder, we could only compute reading time for main idea sentences for those in the sentence presentation groups. As Fig. 3 shows, consistent with this hypothesis, mean reading time for sentences containing main ideas was lower for the elaborated versus unelaborated group, t(89) = 4.99, p < .001, d = − 1.06. Note, for interested readers, we further decompose main idea reading time for both experiments in Table C1 of Appendix C.

Experiment 1. Mean time spent reading the main ideas, including initial and rereading. Unelaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included just the main ideas. Elaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included both main ideas and elaborations. Error bars reflect standard errors

Secondary Outcomes

We report outcomes of secondary interest in Table 1. Regarding global judgments of learning, a 2 (presentation: sentence, paragraph) × 2 (version: unelaborated, elaborated) ANOVA revealed only a main effect of version, with lower judgments for the elaborated version versus the unelaborated version, F(1, 128) = 5.64, MSE = 476.33, p = .019, ηp2 = − .04 (other Fs < 1). Regarding self-reported difficulty, a 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed only a main effect of version; ratings of text difficulty were greater for the elaborated version versus the unelaborated version, F(1, 128) = 11.53, MSE = 528.96, p = .001, ηp2 = .08 (other Fs < 1). Regarding interest and likelihood of reading, none of the main effects or the interactions reached significance (Fs < 2.1, ps > 0.15).

Experiment 2

The first goal of Experiment 2 was to examine further the costs and benefits of textbook elaborations. Several experiments now suggest that textbook elaborations do not yield memory benefits to outweigh the time costs they impose (i.e., Experiment 1 in the current study and Experiments 1–3 from Daley and Rawson 2019). However, Experiment 1 is the first study to demonstrate a memory impairment for main ideas when these main ideas were held constant in the elaborated and unelaborated versions of the text. Experiment 2 thus included a direct replication to establish this effect further, given recent emphasis in the field on the importance of direct replication of novel outcomes (e.g., Pashler and Harris 2012; Schmidt 2009; Simons 2014). In addition to replication of the effect on memory, Experiment 2 provides an additional estimate of overall time cost that supports a more precise effect size estimate based on a meta-analytic approach to inform our overall conclusions (Braver et al. 2014).

The second goal of Experiment 2 was to evaluate the reduced attention hypothesis further. Experiment 1 provided initial empirical support for the reduced attention hypothesis by demonstrating that time spent on main idea sentences was lower for the elaborated versus unelaborated version of the text. Given that Experiment 1 is the only study that has demonstrated this result, direct replication of this novel outcome is important. To that end, the current experiment includes the elaborated and unelaborated sentence presentation groups from Experiment 1 that afford estimation of time spent on main idea sentences. For economy of design, we dropped the paragraph presentation groups that did not afford estimation of time spent on main ideas.

The reduced attention hypothesis states that less attention is spent on main ideas in elaborated texts but is agnostic about why this result occurs. Investigating plausible explanations for this result was thus the third goal of Experiment 2. One explanation for this result may be that students have difficulty identifying the main ideas while reading elaborated texts. As initial evidence for the plausibility of this explanation, we ran some exploratory analyses on the data from Experiment 1. We compared performance on the open-book tests in the control group for participants who were given the elaborated versus unelaborated version of the text to refer to during those tests. Consistent with the possibility that students have difficulty identifying main ideas in elaborated texts, performance on the open-book recall test was greater for the unelaborated (M = 46%, SE = 9) versus elaborated version (M = 19%, SE = 4), t(20) = 2.97, p = .008, d = 1.12. Likewise, performance on the open-book short answer test was greater for the unelaborated (M = 91%, SE = 3) versus elaborated version (M = 74%, SE = 6), t(20) = 2.47, p = .022, d = 1.33.

As further evidence, we conducted a small pilot study in which we gave 15 participants a highlighter and a printed copy of the elaborated text and instructed them to highlight only the main ideas in the elaborated version. On average, students correctly highlighted 6.7 main ideas (hit rate: M = 67%, SE = 5). However, they also highlighted 5.3 textbook elaborations on average (false alarm rate: M = 18%, SE = 3). Although these results provide some initial evidence consistent with the possibility that students have difficulty identifying main ideas in elaborated texts, definitive conclusions await a larger sample. To that end, Experiment 2 included a group that indicated if each sentence primarily described a main idea or an elaboration during their initial reading of the elaborated text (hereafter referred to as the identification group). Also, all groups completed the identification task at the end of Session 2 to provide a measure of the functional ceiling for performance on the identification task. Although we expected students would have some facilities to identify the main ideas, we predicted that identification accuracy would be lower for Session 1 performance in the identification group versus the functional ceiling, indicating students had some difficulty identifying main ideas in elaborated texts while reading.

Although we expected that difficulty identifying main ideas would provide one plausible explanation for differences in time spent reading main ideas, difficulty per se may not fully explain this result. Another possible explanation is that students may sometimes fail to spontaneously identify main ideas while reading. If so, then instructing students to identify main ideas will increase students’ identification of main ideas. If failure to spontaneously identify main ideas underlies differences in time spent on main idea sentences, then explicitly prompting identification will result in greater time spent on main ideas sentences. Therefore, we predicted greater time spent on main ideas sentences in the identification group versus the elaborated group. If the identification instructions increase time spent on the main idea sentences as predicted, the reduced attention hypothesis predicts a corresponding increase in memory for main ideas.

Method

Participants and Design

Participants included 157 undergraduate students at Kent State University (74% female, 74% white, 20% black, 5% Asian, 6% first nations, 1% native Hawaiian, 7% Hispanic or Latino); 35% were first-year college students (M years in college = 2.2, SE = 0.1) and 38% were psychology majors. Participants were 20.2 years old on average (SE = 0.2, range = 18–31). We recruited all participants from the Psychology Department participant pool, and they received course credit. Data from 10 participants were excluded from analyses due to failure to return for Session 2 (n = 8), a computer malfunction (n = 1), and missing Session 1 data (n = 1). The final sample included 154 participants. The final sample sizes for the unelaborated, elaborated, and identification groups were 49, 48, and 50. Target sample size was determined based on a priori power analyses. Specifically, we ran an a priori power analysis to detect a medium effect (d = .5) with power set at .80 and alpha = .05 for a one-tailed between subjects t test, which yielded 51 per group.

Materials and Procedure

All materials were the same as in Experiment 1. For all groups, the text was presented one sentence at a time. For those in the identification group, during initial reading, they were asked to click on one of the two buttons to indicate if each sentence primarily described a main idea or an elaboration. When they clicked a button, the program moved onto the next screen. Participants were not given the option to go back to a previous screen during the initial reading. To align this aspect of the procedure across groups, we also removed the option to go back to a previous screen during initial reading for those in the elaborated and unelaborated groups. After reading the text the first time, in all three groups, the procedure paralleled Experiment 1. On the last screen of the text, participants were shown the navigation buttons that would permit them to reread any text screen (either by going backward and forward through prior screens or by starting over at the first screen).

As in Experiment 1, all participants returned 2 days later for final tests. The procedure in Session 2 was the same as Experiment 1 with three exceptions. First, we dropped the multiple-choice test for reasons noted in Experiment 1. Second, after completing the recall and short answer tests of memory, all three groups completed the main idea identification task that participants in the identification group had completed in the first session. Third, due to a programming error, self-reports of prior exposure to the process of hearing in a course and ratings of prior knowledge were not collected at the end of the second session.

Results and Discussion

Consistent with our pre-registered analysis plan, we report the planned comparisons that address our research questions of interest (for recommendations regarding the use of only those statistical analyses that directly answer one’s research questions, see Judd and McClelland 1989; Rosenthal and Rosnow 1985; Tabachnick and Fidell 2001; Wilkinson and APA Task Force 1999). Also consistent with our pre-registered analysis plan, we report one-tail tests for directional predictions. For all of the primary results of interest, due to our direction predictions, we report one-tail tests. For all secondary results, we report two-tailed tests. For outcomes involving reading time, we calculated time in the same way described for Experiment 1. Additionally, we excluded outliers from analyses below. We identified outliers using the same two-phase procedure. We excluded less than 2% of trials based on the first phase. Based on the second phase, we excluded two participants from analyses of total reading time and three participants from analyses of main idea sentence reading time.

Primary Results for Goal 1: Estimate the Costs and Benefits of Textbook Elaborations

As Fig. 4 shows, textbook elaborations again imposed a large total time cost. Overall, reading time was greater for the elaborated versus the unelaborated group, t(93) = 5.71, p < .001, d = 1.18.

Experiment 2. Mean time spent reading the entire text, including initial and rereading. Unelaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included just the main ideas. Elaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included both main ideas and elaborations. Identification = the group that completed the identification task during initial reading of the elaborated text. Error bars reflect standard error

Regarding possible memory benefits, as Fig. 5 shows, the results of the current experiment again provide no evidence of benefits. Instead, the results replicated the negative effect of textbook elaborations on memory for main ideas found in Experiment 1. Memory for main ideas was lower for the elaborated group versus the unelaborated group [short answer: t(95) = 2.34, p = .010, d = − 0.48; recall: t(95) = 3.16, p = .001, d = − 0.65].

Experiment 2. Mean performance on the short answer and recall posttests. Unelaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included just the main ideas. Elaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included both main ideas and elaborations. Identification = the group that completed the identification task during initial reading of the elaborated text. Error bars reflect standard error

In sum, the results of the current experiment further support the conclusion that textbook elaborations do not provide a memory benefit commensurate with the time cost they impose.

Primary Results for Goal 2: Evaluate the Reduced Attention Hypothesis

According to the reduced attention hypothesis, textbook elaborations fail to enhance memory for main ideas because students spend less time on main ideas when reading the elaborated versus unelaborated version of the text. Experiment 1 provided initial support for this hypothesis. As Fig. 6 shows, the results of the current experiment replicated this novel effect. Mean reading time for sentences containing main ideas was lower for the elaborated group versus the unelaborated group, t(93) = 5.27, p < .001, d = − 1.09.

Experiment 2. Mean time spent reading the main ideas, including initial reading and rereading. Unelaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included just the main ideas. Elaborated = the group that read the version of the text that included both main ideas and elaborations. Identification = the group that completed the identification task during initial reading of the elaborated text. Error bars reflect standard error

Primary Results for Goal 3: Investigate Why Attention Is Reduced for Elaborated Texts

Why did students spend less time on main ideas when reading the elaborated versus unelaborated text? One explanation for this result is that students have difficulty identifying main ideas embedded in the elaborated text. Relevant outcomes from the identification task are displayed in Table 2. The hit rate refers to the mean proportion of main idea sentences that students correctly selected as including main ideas. The false alarm rate refers to the mean proportion of elaboration sentences that students incorrectly selected as including main ideas. From these two measures, we computed d′ (Wickens 2002) using the log-linear approach (Hautus 1995) to adjust for extreme hit or false alarm rates (p = 1 or p = 0). Mean d′ for the identification group in Session 1 was greater than 0, t(49) = 4.29, p < .001, d = 0.61. Therefore, participants had some facility in discriminating main ideas from textbook elaborations. However, identification performance was well below the functional ceiling. The most straightforward comparison of identification performance while reading versus the functional ceiling is the within-participant comparison of performance on the identification task in the identification group in Session 1 versus Session 2. Results indicated that d′ was lower during Session 1 versus Session 2, t(49) = 2.93, p = .005, d = 0.47. Additionally, results of between-participants comparisons indicated that d′ was lower for the identification group in Session 1 versus the elaborated and unelaborated groups in Session 2, [elaborated: t(96) = 4.78, p < .001, d = 0.97; unelaborated: t(97) = 5.68, p < .001, d = 1.14]. These results are consistent with the possibility that difficulty identifying main ideas at least partly explains why students spent less time on main idea sentences when reading the elaborated versus unelaborated text. Further support for this possibility stems from the pattern of performance on the identification task completed at the end of Session 2; discrimination (d′) was somewhat lower for the elaborated group versus the unelaborated group (see Table 2) based on follow-up comparisons using the Tukey HSD correction (p = .18, d = − 0.37).

Another explanation for why students spent less time on main idea sentences is that students may sometimes fail to spontaneously identify main ideas while reading. If so, time spent on main idea sentences would be greater for those who were prompted to identify the main ideas during reading versus those who were not. In contrast to this prediction, as Fig. 6 shows, time spent on main ideas sentences was similar for the identification group and the elaborated group, t(94) = 0.47, p = .320, d = 0.10. Given the similar time spent on main idea sentences, the reduced attention hypothesis would predict that memory for main ideas would be similar. Consistent with this expectation, memory was similar for the identification group and the elaborated group [short answer: t(96) = 0.30, p = .383, d = 0.06; recall: t(96) = 0.02, p = .494, d = 0.00]. In sum, results from the current study do not provide support for the possibility that a lack of spontaneous identification underlies differences in time spent on main idea sentences.

Secondary Outcomes

We report outcomes of secondary interest in Table 1. Based on a one-way ANOVA, groups differed in their global judgments of learning, F(2, 144) = 5.38, MSE = 432.02, p = .006, ηp2 = .07. Post-hoc t tests using the Tukey HSD correction revealed greater judgments for the unelaborated group versus the elaborated group (p = .013, d = 0.57) and the identification group (p = .015, d = 0.58). These greater judgments of learning for the unelaborated versus elaborated version of the text suggest that participants had some metacognitive awareness of the benefits of unelaborated texts. This finding is interesting to note given that students often lack metacognitive awareness of the effects of other factors that affect learning (Dunlosky and Lipko 2007). However, the extent to which this awareness reflects accurate monitoring during learning versus beliefs regarding the effectiveness of elaborations is unclear. Regarding difficulty, groups differed marginally in their reported difficulty, F(2, 144) = 2.96, MSE = 559.89, p = .055, ηp2 = .04. Post-hoc t tests using the Tukey HSD correction revealed marginally greater difficulty for the identification group versus the unelaborated group (p = .059, d = 0.46). Regarding students’ self-reported interest, groups differed in self-reported interest, F(2, 144) = 3.31, MSE = 689.34, p = .039, ηp2 = .04. Post-hoc t tests using the Tukey HSD correction revealed greater reported interest for the identification versus elaborated group (p = .047, d = 0.49). Regarding likelihood of reading, no differences emerged between groups (F = 0.74, p = .478).

Path Models for Experiments 1–2

Both experiments provided evidence for the reduced attention hypothesis, which states that textbook elaborations fail to enhance memory because students spend less time on main ideas when reading the elaborated versus unelaborated version of a text. However, these results do not directly address whether differences in time spent on main idea sentences relate to memory performance for the elaborated and unelaborated version of the text, consistent with the reduced attention hypothesis. To evaluate this hypothesis further, we conducted path models to estimate the extent to which differences in time spent on main idea sentences account for the group differences in memory performance for the elaborated and unelaborated version of the text. We conducted these models using the PROCESS macro for SPSS. For these models, we report unstandardized coefficients (cf. Baguley 2009; Hayes 2017).

For each experiment, we conducted simple path models in which we tested the indirect effect of version (i.e., elaborated or unelaborated) on each of our measures of memory (i.e., short answer and recall). Table 3 presents the results of these four models. Consistent with primary outcomes reported above, reading time for main idea sentences was lower for the elaborated versus unelaborated version of the text (Table 3, column a). Importantly, consistent with the reduced attention hypothesis, lower time spent on main ideas sentences was associated with lower memory (Table 3, column b). For each model, the indirect effect of text version on memory for main ideas through time spent on main idea sentences was estimated using a 95% bias-corrected confidence interval using 5000 bootstrap samples. This indirect effect estimates the extent to which memory performance for the elaborated and unelaborated groups can be attributed to time spent on main ideas for the elaborated text. The confidence interval around the effect size estimate of the indirect effect did not contain 0 for any model (see Table 3, column ab). Across the four models, the indirect path accounted for 46–77% of the total effect of text version on memory for main ideas. This pattern of results suggests that the group differences in memory performance for the elaborated and unelaborated version of the text can at least partly be attributed to differences in time spent on the main idea sentences, providing additional support for the reduced attention hypothesis.

General Discussion

Given the prevalence of elaborations in textbooks, research investigating the effects of these elaborations is surprisingly limited. Only one prior study has directly examined both the costs and benefits of textbook elaborations (Daley and Rawson 2019). The current study aimed to conceptually replicate this study and further estimate the costs and benefits of textbook elaborations. Additionally, the current study investigated why textbook elaborations sometimes fail to afford memory benefits. To explain this counterintuitive finding, we tested the reduced attention hypothesis, which states that textbook elaborations fail to enhance learning because they decrease the amount of time students spend reading the main ideas.

To base our overall conclusions on the most stable estimates of effect sizes available from the current set of studies, we conducted internal meta-analyses (Braver et al. 2014) across the two experiments for the primary outcomes of interest (see Table 4). These combined estimates support several overall conclusions about the effects of textbook elaborations. Concerning costs and benefits, textbook elaborations impose a large time cost (pooled d = 1.23, 95% CI = 0.98, 1.49) but do not afford benefits to memory for main ideas (short answer: pooled d = − 0.55, 95% CI = − 0.79, − 0.31; recall: pooled d = − 0.67, 95% CI = − 0.91, − 0.43). Concerning why textbook elaborations fail to benefit memory, textbook elaborations produced a large reduction in time spent on main ideas, confirming the key prediction of the reduced attention hypothesis (pooled d = − 1.16, 95% CI = − 1.44, − 0.89).

Costs and Benefits of Textbook Elaborations

Taken together, these results sharply contrast the intuitive assumption that textbook elaborations are robust learning tools, which presumably underlies their widespread use in textbooks. Instead, the current research demonstrated several negative effects of textbook elaborations. Textbook elaborations imposed a considerable cost in overall time spent reading the text, reduced the amount of time spent reading main ideas, and impaired memory for main ideas. These results are consistent with conclusions from the one relevant prior study (Daley and Rawson 2019) that textbook elaborations impose a large time cost that is not offset by benefits to learning.

Although both studies support the conclusion that textbook elaborations afford no benefit to memory for main ideas, this conclusion is based on somewhat different patterns of memory performance (i.e., similar memory performance in the prior study and a negative effect in the current study). This different pattern of memory performance may have emerged due to the different text structures involved in these studies. To revisit, the current study involved a sequence structure that described the series of connected steps involved in the process of hearing, whereas the previous work involved an enumeration structure that listed topically related but somewhat independent concepts. Linking main ideas together may be more important for the sequential structure versus an enumeration structure. If so, the textbook elaborations that were interspersed between the main ideas in the elaborated sequential text may have disrupted this linking and thus impaired memory.

Another potential difference in the texts used in these two studies is that the textbook passages used for materials in the prior study versus the current study included somewhat different kinds of elaborations. As a result, the text in the current study describing the sequential process of hearing tended to include elaborations that further described the purpose of various steps and that described features of the physical structures of the ear. The texts in the prior study describing abstract concepts tended to include elaborations that provided concrete and familiar representations of the abstract concepts. The different characteristics of these elaborations may have resulted in different effects on memory.

Consistent with this possibility, previous research examining memory for adjectives in sentence lists has found that the effect of elaborations depends on the kind of elaboration (e.g., Di Vesta and Finke 1985; Stein et al. 1978; Stein and Bransford 1979). Specifically, memory for target adjectives is greater when they are combined with elaborations that specify their unique properties versus elaborations that do not. For instance, Stein et al. (1978) found that the adjective “slow” in the base sentence “The diamond was too expensive for the slow man” was better remembered when presented with “who was fired from his job” but not “to hand down to his son.” Although this work points to the possibility that the effect of elaborations depends on the type of elaboration, the extent to which these findings involving sentence lists would generalize to connected discourse is unclear.

Although addressing this potential moderator with connected discourse is an interesting direction for future research, the current study aimed to examine the efficacy of elaborations included in textbooks. To that end, all texts contained a mixture of various types of elaborations. This mixture of elaborations is arguably a defining characteristic of authentic textbook materials (e.g., we have yet to find a textbook passage that includes one and only one type of elaboration during our material development for this in other projects involving more than 30 authentic textbook passages). Most important for current purposes, prescriptive conclusions across these authentic materials are consistent. Textbook elaborations impose a large time cost that is not outweighed by a memory benefit.

Explaining Why Textbook Elaborations Fail to Enhance Memory

The current research provides an important theoretical advance by investigating why textbook elaborations sometimes fail to enhance memory for main ideas. To revisit, the reduced attention hypothesis posits that textbook elaborations fail to enhance memory because they decrease the amount of time students spend reading the main ideas. Consistent with this hypothesis, students spent considerably less time on sentences containing main ideas when reading the elaborated versus unelaborated version in both experiments. Additionally, outcomes of path models provided converging evidence by demonstrating that a large proportion (46–77%) of the total effect of text version on memory for main ideas was explained via the indirect effect of text version through time spent on main ideas. In sum, the results of the current study support the reduced attention hypothesis.

Given the support for the reduced attention hypothesis, we examined why students spend less time on main ideas in the elaborated versus unelaborated version. In particular, Experiment 2 examined the possibility that this difference in time stems from difficulty discriminating sentences containing main ideas versus textbook elaborations. Consistent with this possibility, discrimination performance for the identification group during initial reading was lower than the functional ceiling. Additionally, as noted above, performance was somewhat lower for the elaborated versus unelaborated groups.

As noted above, consistent with the reduced attention hypothesis, a large proportion of the total effect of text version on memory for main ideas was explained via the indirect effect of text version through time spent on main ideas. Nevertheless, the remaining variance provides evidence that other factors may also contribute to the failure of textbook elaborations to benefit memory for main ideas. For instance, instead of facilitating recall, textbook elaborations may sometimes compete with recall of main ideas, leading to interference. According to theories of interference, when more than one piece of information is linked to a cue, this leads to competition when this cue is used for retrieval (Anderson and Neely 1996). The more information that is linked to a cue, the lower the probability of recalling any particular piece of information. In the current context, memory for main ideas may be lower in a text with versus without textbook elaborations because the textbook elaborations compete with the main ideas at retrieval. Therefore, an interference account predicts lower memory for the elaborated versus unelaborated text. However, an interference account would also likely predict that this effect would be more robust on recall versus short answer tests of memory. In contrast, the negative effects of textbook elaborations on recall and short answer were similar in the current experiments. Additionally, the large differences in main idea sentence reading time found in the current experiments do not clearly follow from theories of interference. Nevertheless, testing the possible contributing role of interference (and other possible mechanisms) is an interesting direction for future research.

Practical Implications

Although textbook elaborations are common, the current study provides evidence that they impose a substantial time cost that is not justified by any memory benefits. Therefore, omitting elaborations from textbooks may save students time for learning other materials without hurting their memory for the main ideas in the passage. However, a recommendation this radical would be premature at this point. Although students may benefit from reading the main ideas alone in some cases, the current study also points to conditions under which textbook elaborations may be more effective in supporting memory for main ideas. The current research shows that at least part of the reason textbook elaborations are ineffective is due to less time spent on main ideas. Further, evidence suggests that students spent less time because they have difficulty differentiating main ideas from textbook elaborations. Therefore, one way to increase the time spent reading main ideas and potentially show benefits of textbook elaborations may be to indicate which sentences contain the main ideas in texts. Another intriguing possibility follows from the greater discrimination in Session 2 following the reading of the unelaborated versus elaborated version in Session 1. These results suggest that reading an unelaborated version of the text first may help students better identify the main ideas in the elaborated chapter. If so, students who read the mid-chapter or end-of-chapter summaries often included in textbooks before reading the full chapter may have greater facility identifying main ideas. Thus, they may allocate more reading time to these main ideas, revealing the benefits of textbook elaborations.

In addition to investigating conditions under which elaborations may be more effective, recommendations to remove elaborations also await a clear understanding of how elaborations affect other important learning outcomes. To that end, the current study attempted to measure effects of textbook elaborations on comprehension. However, the comprehension results were difficult to interpret in Experiment 1 and thus this measure was dropped from Experiment 2. Nevertheless, examining effects on comprehension is an important direction for future research due to the applied relevance of this outcome. Additionally, trends from prior work indicate benefits of elaborations may be greater for comprehension versus memory (Daley and Rawson 2019).

Before closing, we briefly discuss a concern about this work that most frequently comes up in conversations with colleagues. Their concern is that the textbooks and passages we sampled may have included textbook elaborations that are “ineffective.” Indeed, our results align with this concern: the textbooks we sampled include ineffective elaborations in terms of enhancing memory for the main ideas. Did we happen to sample textbooks that include less effective elaborations than most textbooks? Inconsistent with this possibility, the lack of memory benefit found in Daley and Rawson (2019) generalized to the current experiments involving a passage from different textbooks, on a different topic, and with a different text structure. Additional work is needed to investigate if these results generalize to other textbooks and topics, but we find it implausible that the textbooks we sampled are the only textbooks that include ineffective elaborations. This possibility seems particularly improbable given that a Google search shows some of these textbooks are among the top ten for introductory psychology. Still, we hope others will join us in investigating other textbooks and topics, especially topics other than psychology. However, investigating every topic in every textbook is impossible. Instead, greater benefits may follow from understanding why elaborations in some textbooks fail to support memory. We began addressing this question in the current study and found initial support for the reduced attention hypothesis. Support for this hypothesis is a starting point for future work aimed at investigating how to increase the efficacy of textbook elaborations.

Conclusions

Assigned reading of textbooks is common across most levels of education, and elaborations are one of the most common textbook features. Given their prevalence in educational texts, surprisingly, limited research has examined the costs and benefits of textbook elaborations. The current study further establishes the costs and benefits of textbook elaborations, indicating that textbook elaborations impose a substantial time cost on students but yield no benefit to memory for main ideas. The current study also supports the hypothesized role of less time spent on main ideas, which in turn is due to difficulty discriminating main ideas from elaborations. The negative impact of textbook elaborations is particularly concerning given the widespread use of elaborations in textbooks and highlights the need for future work pinpointing the conditions under which textbook elaborations may be effective. The current study not only provides a theoretical, methodological, and empirical foundation for further research, it also highlights the importance of investigating the presumed but largely undocumented effects of elaborations in textbooks.

Notes

Note the minor deviation here from our pre-registered analysis plan that involved separate t-tests for each presentation format for consistency between analysis of this measure and the measures of memory.

References

Allwood, C. M., Wikstrom, T., & Reder, L. (1982). The effect of format and structure of text material on recallability. Poetics, 11(2), 145–153.

Anderson, M. C., & Neely, J. H. (1996). Interference and inhibition in memory retrieval. In E. L. Bjork & R. A. Bjork (Eds.), Memory (pp. 237–313). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Baguley, T. (2009). Standardized or simple effect size: what should be reported? British Journal of Psychology, 100(3), 603–617.

Braver, S. L., Thoemmes, F. J., & Rosenthal, R. (2014). Continuously cumulating meta-analysis and replicability. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(3), 333–342.

Carlson, N. R. (2008). Foundations of physiological psychology. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Cook, L. K., & Mayer, R. E. (1988). Teaching readers about the structure of scientific text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(4), 448–456.

Dal Martello, M. F. (1984). The effect of illustrative details on the recall of main points in simple fictional and factual texts. Discourse Processes, 7(4), 483–492.

Daley, N., & Rawson, K. A. (2019). Elaborations in expository text impose a substantial time cost but do not enhance learning. Educational Psychology Review, 31(1), 197–222.

Di Vesta, F. J., & Finke, F. M. (1985). Metacognition, elaboration, and knowledge acquisition: implications for instructional design. Educational Communication and Technology Journal, 33(4), 285–293.

Dunlosky, J., & Lipko, A. R. (2007). Metacomprehension: a brief history and how to improve its accuracy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(4), 228–232.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2007). Statistical power analyses using G*power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160.

Franzoi, S. (2002). Psychology: a journey of discovery. Cincinnati, OH: Atomic Dog Publishing.

Freeman, R. H. (1985). Recall of Central Facts from Text. Paper presented at the 35th Annual Meeting of the National Reading Conference; Dec. 3-7; San Diego, CA.

Hautus, M. J. (1995). Corrections for extreme proportions and their biasing effects on estimated values of d′. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 27(1), 46–51.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guliford Publications.

Judd, C. M., & McClelland, G. H. (1989). Data analysis: a model-comparison approach. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Kalat, J. W. (2004). Biological psychology (8th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

King, L. A. (2008). The science of psychology: an appreciative view. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Lahey, B. B. (2009). Psychology: an introduction (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Higher Education.

Lilienfeld, L., Namy, & Woolf. (2009). Psychology: From inquiry to understanding. Virginia: Pearson Education.

Mohr, P., Glover, J. A., & Ronning, R. R. (1984). The effect of related and unrelated details on the recall of major ideas in prose. Journal of Reading Behavior, 2, 97–108.

Myers, D. G. (2010). Psychology (9th ed.). New York, NY: Worth Publishers.

Palmere, M., Benton, S. L., Glover, J. A., & Ronning, R. R. (1983). Elaboration and recall of main ideas in prose. Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(6), 898–907.

Pashler, H., & Harris, C. R. (2012). Is the replicability crisis overblown? Three arguments examined. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7(6), 531–536.

Phifer, A. J., McNickle, B., Ronning, R. R., & Glover, J. A. (1983). The effect of details on the recall of major ideas in text. Journal of Reading Behavior, 1, 19–30.

Pressley, M., McDaniel, M. A., Turnure, J. E., Wood, E., & Ahmad, M. (1987). Generation and precision of elaboration: effects on intentional and incidental learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 13(2), 291.

Reder, L. M., & Anderson, J. R. (1980). A comparison of texts and their summaries: memorial consequences. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 19(2), 121–134.

Rosenthal, R., & Rosnow, R. L. (1985). Contrast analysis: focused comparisons in the analysis of variance. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., & Wegner, D. M. (2009). Psychology. New York, NY: Worth Publishers.

Schmidt, S. (2009). Shall we really do it again? The powerful concept of replication is neglected in the social sciences. Review of General Psychology, 13(2), 90–100.

Simons, D. J. (2014). The value of direct replication. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(1), 76–80.

Stein, B. S., & Bransford, J. D. (1979). Constraints on effective elaboration: effects of precision and subject generation. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 18(6), 769–777.

Stein, B. S., Morris, C. D., & Bransford, J. D. (1978). Constraints on effective elaboration. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 17(6), 707–714.

Stein, B. S., Littlefield, J., Bransford, J. D., & Persampieri, M. (1984). Elaboration and knowledge acquisition. Memory & Cognition, 12(5), 522–529.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Wade, C., & Tavris, C. (2004). Psychology (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

Wickens, T. D. (2002). Elementary signal detection theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wilkinson, L., & Task Force on Statistical Inference. (1999). Statistical methods in psychology journals: guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist, 54(8), 594–604.

Wolfe, J. M., Kluender, K. R., Levi, D. M., Bartoshuk, L. M., Herz, R. S., Klatzky, R. L., & Merfeld, D. M. (2008). Sensation and perception (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Sinauer Associates.

Zamary, A., & Rawson, K. A. (2018). Which technique is most effective for learning declarative concepts—provided examples, generated examples, or both? Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 275–301.

Funding

The research reported here was supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) Graduate Research Fellowship to Nola Daley and by James S. McDonnell Foundation twenty-first Century Science Initiative in Bridging Brain, Mind, and Behavior Collaborative Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Short-answer memory test used in Experiments 1–2

1. Sound waves first enter through what part of the ear?

2. After entering the outer ear, what do sound waves travel through next?

3. After traveling through the auditory canal, sound waves strike what part of the ear?

4. The tympanic membrane does what in response to sound waves?

5. Vibrations from the tympanic membrane are then passed along what parts of the ear?

6. What parts of the ear are located in the middle ear?

7. What role do the ossicles play in hearing?

8. When vibrations reach the last of the ossicles, what does that bone do?

9. Movement of the oval window does what?

10. The movement of fluid in the Cochlea displaces what?

11. What do hair cells do in response to displacement?

12. After hair cells initiate a signal, the signal travels along what pathway?

13. Where does the auditory nerve send the signals initiated by the hair cells?

Performance on the multiple-choice test in Experiment 1

Decomposing time spend on main ideas in each experiment

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Daley, N., Rawson, K.A. Effects of Elaborations Included in Textbooks: Large Time Cost, Reduced Attention, and Lower Memory for Main Ideas. Educ Psychol Rev 33, 1165–1189 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09553-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09553-x