Abstract

Background

Evidence exists on the association between vitamin D deficiency and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD).

Aims

To investigate whether vitamin D level is associated with disease activity and quality of life in IBD patients.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted on known adult IBD patients referred to an outpatient clinic of gastroenterology in Isfahan city, Iran. Disease activity was evaluated using the Simplified Crohn’s Disease Activity Index and Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index. Quality of life was assessed with the Short-Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire. Serum 25[OH]D was measured using the radioimmunoassay method. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency were defined as concentration of <50 and 50–75 nmol/L, respectively.

Results

Studied subjects were 85 ulcerative colitis and 48 Crohn’s disease patients (54.1 % females) with mean age of 42.0 ± 14.0 years. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency were present in 52 (39.0 %) and 24 (18.0 %) patients, respectively. Thirty patients (22.5 %) had active disease who, compared with patients in remission, had more frequent low vitamin D levels (80 vs. 50.4 %, P = 0.005). Quality of life was not different between patients with low and those with normal vitamin D levels (P = 0.693). In the logistic regression model, low vitamin D was independently associated with active disease status, OR (95 % CI) = 5.959 (1.695–20.952).

Conclusions

We found an association between vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency and disease activity in IBD patients. Prospective cohorts and clinical trials are required to clarify the role of vitamin D deficiency and its treatment in clinical course of IBD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract with a chronic and relapsing course requiring lifelong treatment [1]. Prevalence of UC and CD is reported from 7.6 to 246 and from 3.6 to 214 cases per 100,000 populations, respectively [1]. The epidemiology of IBD in Iran is not well understood, but the reported epidemiology and clinical characteristics seem to be more or less the same as in other Asian populations with the rising incidence and prevalence [2]. The etiology of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) is not completely understood, but suggested to be due to inappropriate inflammatory reactions in response to the intestinal flora and antigens in a genetically susceptible host [1].

Known genetic variations, however, cannot completely explain geographic differences in the incidence of IBD, suggesting a role for environmental factors in the pathophysiology of the disease. Environmental factors discussed in IBD are pointed out as smoking, medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, stress and psychological factors such as depression, nutritional factors, and even air pollution [3]. Another environmental factor discussed in the pathophysiology of IBD is vitamin D deficiency [4]. Vitamin D is known from the past as a major regulator of calcium and phosphorus metabolism and a key factor in bone health. However, recent studies have provided new insights on the role of vitamin D in other physiological processes. In particular, there is evidence that vitamin D plays a role in immune regulation [5] and cancer [6]. Also, findings of the recent studies support the role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis, clinical course, and also the potential treatment of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis [7], systemic lupus erythematous [8], and IBD [9]. Furthermore, due to the role of vitamin D deficiency in the risk of gastrointestinal cancers, it is likely that vitamin D deficiency is involved in the increased risk of malignancies seen in IBD patients [10].

Multiple pathways link vitamin D status with the risk of development and clinical course of IBD. Vitamin D regulates epithelial cell integrity [11], and its deficiency leads to intestinal barrier dysfunction, mucosal damage, and susceptibility to infectious agents [12, 13]. Also, it affects the mucosal and systemic immune system activities, generally with regulatory and anti-inflammatory properties [14]. There is also evidence on the role of vitamin D on the gut microbiome, which is implicated in the pathogenesis and clinical course of IBD [11]. Accordingly, it is possible that vitamin D affects the severity of inflammation and disease course in IBD patients [9]. However, limited studies are conducted on the relationship between vitamin D and disease activity in IBD, and the results have been inconsistent [9]. According to the lack of data, especially in our society, we aimed to determine the association of vitamin D with disease activity and quality of life in IBD patients in the Isfahan city, Iran.

Methods

Patients and Settings

This cross-sectional study was conducted on known IBD patients referring to a single outpatient clinic of gastroenterology in Isfahan city (Iran) between January and December 2014. Adult patients with confirmed diagnosis of IBD (UC and CD) based on endoscopic and pathologic studies were consecutively evaluated. Those with history of gastrointestinal surgery were not included in the study. We estimated vitamin D deficiency to be present in about 50 % of our patients based on previous reports [15]. Active disease status was estimated in about 25 % of the patients based on a pilot study in the clinic. The study sample size was then calculated as 115 using the G*Power software (version 3, Universität Düsseldorf, Germany) with estimating type I error and study power as 0.5 and 0.8, respectively, and expecting 10 % missing data.

Measurements

All patients were visited by a single experienced gastroenterologist. Data on demographic and disease characteristics were obtained, physical examination was done, and height and weight were measured with single calibrated scales. Disease activity was measured using the Simplified Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (SCDAI) for CD [16] and Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (SCCAI) for UC [17]. The SCDAI is a simplified version of the CDAI used for measuring disease activity in CD patients, which contains items on the number of liquid/soft stools, severity of abdominal pain, and general wellbeing. A total score of >150 is indicative of active disease status in this scale [16]. The SCCAI is used to measure disease activity in UC patients and contains items on day and night bowel frequency, urgency for defecation, bloody stool, and general well-being. The total score ranges from 0 to 16 with scores of 6 and above indicating active disease state [17]. Serologic markers of inflammation including C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and blood leukocyte counts were also recorded from patients’ laboratory files.

Patients completed the short-form version of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ-9) which is used for the assessment of quality of life (QOL) in IBD patients. It contains nine items with 7-point Likert type scales and evaluates bowel and systemic symptoms and social and emotional functions. The total score ranges from 1 to 63 with higher scores indicating more impaired QOL [18]. A validated Persian version of the questionnaire with acceptable psychometric characteristics was used in this study [19].

To evaluate vitamin D status, serum level of 25[OH]D was measured using the radioimmunoassay method in a single clinical laboratory (VIDAS® 25 OH Vitamin D Total, BIOMÉRIEUX SA, France). Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency were defined as serum 25[OH]D concentration of <50 and 50–75 nmol/L, respectively, based on the US Endocrine Society guideline [20].

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or number (valid percent). Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of qualitative nominal variables. Normal distribution of the quantitative data was checked with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Then, independent sample t test or Mann–Whitney U test was applied for comparison of quantitative data. Correlations between variables were checked with the Spearman’s rho test. Also, logistic regression analysis was performed to test the association between vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency and active disease status while controlling for possible confounding factors. The 95 % confidence interval (CI) is reported where relevant. Two-sided P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

A total of 149 patients were evaluated over the study period from which 16 patients were excluded: Five underwent gastrointestinal surgery, four had indeterminate colitis, four had incomplete data, and three refused to participate. Therefore, 133 patients were included into the study providing a power of 0.88 based on the post hoc power analysis. Included subjects were 85 UC and 48 CD patients (54.1 % females) with mean age of 42.0 ± 14.0 years and disease duration of 5.6 ± 4.2 years. Demographic data and disease characteristics of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

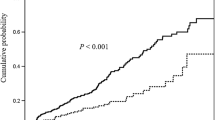

Thirty patients (22.5 %) had active disease, and 103 patients (77.4 %) were in remission. Compared with patients in remission, those with active disease had more frequent abnormal fecal leukocyte (43.3 vs. 6.7 % with ≥2 L/hpf, P < 0.001), lower serum 25[OH]D level (60.4 ± 48.9 vs. 81.7 ± 51.8 nmol/L, P = 0.046), and more frequent vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency (80 vs. 50.4 %, P = 0.005). Patients with active disease were visited more frequently between winter and spring, while those who were in remission were visited more frequently in summer and autumn (P = 0.021). Also, quality of life score was higher (i.e., more impaired) in those with active disease (P < 0.001), Table 2.

Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency were present in 52 (39.0 %) and 24 (18.0 %) patients, respectively. Fifty seven patients (42.8 %) had normal serum 25[OH]D levels. Compared to patients with normal serum 25[OH]D level, those with low vitamin D levels were younger (39.4 ± 13.9 vs. 45.3 ± 15.4 years, P = 0.022) and had higher BMI (24.0 ± 4.1 vs. 21.8 ± 3.5, P = 0.001) and more frequent abnormal fecal leukocyte (22.3 vs. 5.2 % with ≥2 L/hpf, P = 0.006). About 31 % of the patients were consuming vitamin D supplements containing between 200 and 400 IU of vitamin D3 in almost all cases and with no association with vitamin D status (P = 0.704). No significant association was found between season of visit and vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency (P = 0.431). Also, there was no significant difference between patients with low and normal vitamin D levels regarding quality of life score (P = 0.693), Table 3.

The Spearman’s rho test found no linear correlation between serum 25[OH]D level and disease activity indices (r = −0.175 and −0.216, P > 0.05). In a logistic regression model controlling for age, BMI, and season of assessment (winter–spring vs. summer–autumn), vitamin D deficiency/insufficiency was significantly associated with active disease status, OR (95 % CI) = 5.959 (1.695–20.952), P = 0.005 (Nagelkerke R Square = 0.184).

Discussion

We aimed to evaluate the association of vitamin D status with disease activity and quality of life in IBD patients. More than half of our patients had vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency. Previous studies reported various frequencies of low vitamin D levels in IBD patients ranged from 16 to 95 % [9]. Differences between studies’ results may be attributed to different patients’ characteristics (e.g., demographic, disease activity, nutritional status), environmental factors, as well as different cutoffs for defining low vitamin D levels. We found an independent association between low vitamin D level and active disease status, but not quality of life, in IBD patients. There was, however, no linear correlation between serum 25[OH]D concentration and scores of disease activity. Also, no association was found between vitamin D status and serum markers of inflammation (ESR, CRP, and blood leukocytes) in our study. There was only an association between low vitamin D level and presence of fecal leukocytes, a marker of intestinal inflammation. These results may, in part, be related to the suboptimal ability of the current clinical activity indices [21] as well as serum inflammatory markers [22] for the assessment of disease activity in IBD patients. In contrast, fecal markers of inflammation such as calprotectin are better able to evaluate disease activity in these patients [23, 24]. Also, the effects of vitamin D on IBD activity may not be evident by systemic inflammatory markers. This subject was investigated by Garg et al. [25] who reported an inverse correlation of serum 25[OH]D level with fecal calprotectin, but not with systemic inflammatory markers, in IBD patients. In another study, Raftery and colleagues found an association between 25[OH]D level and fecal calprotectin in CD patients, particularly among those in clinical remission. However, no association was found between vitamin D level and disease activity score or CRP in this study [26]. Accordingly, a more comprehensive evaluation of inflammatory markers, both intestinal and systemic, is required in future studies to better investigate the role of vitamin D in IBD activity.

Genetic studies have shown an association between vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and the incidence of IBD [27]. This association is also found in our population, Iran [28]. However, few cohorts directly have evaluated the association of low vitamin D level and risk of IBD. In this regard, a 22-year cohort showed a 6 % reduction in the relative risk of CD with each 1 ng/mL increase in the level of vitamin D. Also, every 100 IU/day increase in vitamin D intake was associated with a 10 % reduction in the relative risk of UC [29]. There is still lack of cohorts evaluating direct risk of IBD with vitamin D deficiency, and more studies are required in this regard. Epidemiological evidence also supports the role of vitamin D in the pathogenesis of IBD. For example, the north–south gradient of the incidence of IBD follows the gradient of ultraviolet exposure and thus vitamin D levels [30–32]. Such variation in ultraviolet exposure is also found associated with hospitalization rate and duration as well as need for surgery in IBD patients [33]. Although we found active disease status being more frequently visited during winter–spring than summer–autumn, there was no significant association between vitamin D level and season of assessment. It may be due to small sample size of the study with limited number of patients being evaluated in each season. Also, it is possible that factors other than vitamin D deficiency (e.g., infections) play a role in the seasonal changes of disease activity in IBD patients [34]. Considering the lack of data on this subject and multiple influencing factors, further studies with larger sample of patients are required before a clear conclusion could be met.

Besides the association between vitamin D system deficiencies and the risk of developing IBD, studies also have evaluated the role of this system in clinical course of the disease. A number of cross-sectional studies have reported an association between vitamin D deficiency and increased clinical activity in UC [35] and CD patients [36, 37]. Similar to our results, Blanck et al. [35] found active disease status two times more frequent in vitamin D deficient UC patients than in those with normal vitamin D levels. Jorgensen et al. [36] found inverse association between serum 25[OH]D and disease activity in CD patients. Such association was also evident if active disease was defined by the CRP. In other study by Ham et al. [37], serum vitamin D level was associated with clinical activity index but not with CRP. In contrast, there are a number of cross-sectional studies that found no association between serum 25[OH]D level and IBD disease activity, particularly in children [38–40]. Differences between the studies may be related to differences in patients’ characteristics and/or methods of measurements. While a cause-and-effect relationship may not be definitely concluded from cross-sectional designs, cohort studies, albeit limited ones, also have found a role for vitamin D in clinical course of IBD. Ananthakrishnan et al. in a series of cohorts have shown that vitamin D deficiency is associated with increasing need for surgery and hospitalization in IBD patients. Furthermore, the risk of surgery was reduced in patients who have been successfully treated by vitamin D [41]. These investigators also found association of vitamin D deficiency with increased risk of colorectal cancer in IBD patients [10]. These findings are of important clinical implications and needed to be confirmed by further large prospective studies.

Although we found impaired quality of life in patients with active disease compared to those in remission, we found no association between vitamin D deficiency and quality of life. In contrast, a retrospective study by Ulitsky et al. [15] found lack of vitamin D independently associated with increased activity and reduced quality of life in CD patients. The study by Hlavaty et al. [42] also found an association between vitamin D and quality of life in UC but not in CD patients. It must be noted that several factors, other than disease activity, may affect the quality of life of IBD patients and our results may be due to the limited number of patients with active disease. Differences between studies may also be related to different quality of life measures, and future studies are needed to use universally accepted tools in this regard.

There are few reports available from clinical trials evaluating the effect of vitamin D supplementation on clinical course of IBD. Jorgensen et al. [43] assessed the effects of vitamin D3 treatment (1200 IU/day for 12 months) on disease course in CD patients and found a reduced, albeit nonsignificant, risk of relapse (from 29 to 13 %) in these patients. In the study by Hlavaty et al. [42], IBD patients were treated with vitamin D3 (400–1000 IU/day) for 3 months. However, there was no change in quality of life or in serum concentration of vitamin D after supplementation. In our study, about one-third of the patients were consuming daily supplements which mostly contained between 200 and 400 IU vitamin D3. According to these results, a much higher dose of vitamin D is required to correct vitamin D level in those with deficiency and/or to exert beneficial effects on IBD clinical course in those with normal vitamin D level [9].

Our study has a number of limitations. First of all, the study had a cross-sectional design and a cause-and-effect relationship cannot definitely be concluded from the results. The study was conducted in a single outpatient clinic with limited number of patients presenting with active disease which limits the generalizability of the findings. Also, due to limited available resources, we were not able to check intestinal inflammation markers in all patients which could provide better data on disease activity.

In summary, we found vitamin D deficiency or insufficiency in more than half of our IBD patients. Low vitamin D level was associated with active disease status, and this association was independent from possible confounding factors. However, we found no association between vitamin D status and quality of life in IBD patients. Also, no association was found between vitamin D level and serum inflammatory markers. Prospective cohorts and clinical trials are required to clarify the role of vitamin D in clinical course of disease in IBD patients. Also, a more comprehensive evaluation of inflammatory markers, including intestinal reliable markers, is required to better investigate the role of vitamin D in IBD activity.

References

Hanauer SB. Inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:S3–S9.

Aghazadeh R, Zali MR, Bahari A, Amin K, Ghahghaie F, Firouzi F. Inflammatory bowel disease in Iran: a review of 457 cases. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;20:1691–1695.

Ananthakrishnan AN. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases: a review. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:290–298.

Lim WC, Hanauer SB, Li YC. Mechanisms of disease: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:308–315.

Mora JR, Iwata M, von Andrian UH. Vitamin effects on the immune system: vitamins A and D take centre stage. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:685–698.

Garland CF, Garland FC, Gorham ED, et al. The role of vitamin D in cancer prevention. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:252–261.

Munger KL, Zhang SM, O’Reilly E, et al. Vitamin D intake and incidence of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62:60–65.

Kamen DL, Cooper GS, Bouali H, Shaftman SR, Hollis BW, Gilkeson GS. Vitamin D deficiency in systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:114–117.

Mouli VP, Ananthakrishnan AN. Review article: vitamin D and inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:125–136.

Ananthakrishnan AN, Cheng SC, Cai T, et al. Association between reduced plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D and increased risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:821–827.

Cantorna MT, McDaniel K, Bora S, Chen J, James J. Vitamin D, immune regulation, the microbiota, and inflammatory bowel disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2014;239:1524–1530.

Kong J, Zhang Z, Musch MW, et al. Novel role of the vitamin D receptor in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G208–G216.

Assa A, Vong L, Pinnell LJ, Avitzur N, Johnson-Henry KC, Sherman PM. Vitamin D deficiency promotes epithelial barrier dysfunction and intestinal inflammation. J Infect Dis. 2014;210:1296–1305.

van Etten E, Mathieu C. Immunoregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3: basic concepts. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97:93–101.

Ulitsky A, Ananthakrishnan AN, Naik A, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: association with disease activity and quality of life. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2011;35:308–316.

Thia K, Faubion WA Jr, Loftus EV Jr, Persson T, Persson A, Sandborn WJ. Short CDAI: development and validation of a shortened and simplified Crohn’s disease activity index. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:105–111.

Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998;43:29–32.

Casellas F, Alcala MJ, Prieto L, Miro JR, Malagelada JR. Assessment of the influence of disease activity on the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease using a short questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:457–461.

Gholamrezaei A, Haghdani S, Shemshaki H, Tavakoli H, Emami MH. Linguistic validation of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire-Short Form (IBDQ-9) in Iranian population. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2011;28:1850–1859.

Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:1911–1930.

Falvey JD, Hoskin T, Meijer B, et al. Disease activity assessment in IBD: clinical indices and biomarkers fail to predict endoscopic remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:824–831.

Vermeire S, Van AG, Rutgeerts P. Laboratory markers in IBD: Useful, magic, or unnecessary toys? Gut. 2006;55:426–431.

Schoepfer AM, Beglinger C, Straumann A, et al. Fecal calprotectin correlates more closely with the Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s disease (SES-CD) than CRP, blood leukocytes, and the CDAI. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:162–169.

Schoepfer AM, Beglinger C, Straumann A, et al. Fecal calprotectin more accurately reflects endoscopic activity of ulcerative colitis than the Lichtiger Index, C-reactive protein, platelets, hemoglobin, and blood leukocytes. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:332–341.

Garg M, Rosella O, Lubel JS, Gibson PR. Association of circulating vitamin D concentrations with intestinal but not systemic inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:2634–2643.

Raftery T, Merrick M, Healy M, et al. Vitamin D status is associated with intestinal inflammation as measured by fecal calprotectin in Crohn’s disease in clinical remission. Dig Dis Sci. (Epub ahead of print). doi:10.1007/s10620-015-3620-1.

Xue LN, Xu KQ, Zhang W, Wang Q, Wu J, Wang XY. Associations between vitamin D receptor polymorphisms and susceptibility to ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:54–60.

Naderi N, Farnood A, Habibi M, et al. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms in Iranian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1816–1822.

Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Higuchi LM, et al. Higher predicted vitamin D status is associated with reduced risk of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:482–489.

Logan I, Bowlus CL. The geoepidemiology of autoimmune intestinal diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:A372–A378.

Nerich V, Jantchou P, Boutron-Ruault MC, et al. Low exposure to sunlight is a risk factor for Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:940–945.

Jussila A, Virta LJ, Salomaa V, Maki J, Jula A, Farkkila MA. High and increasing prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Finland with a clear North-South difference. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e256–e262.

Limketkai BN, Bayless TM, Brant SR, Hutfless SM. Lower regional and temporal ultraviolet exposure is associated with increased rates and severity of inflammatory bowel disease hospitalisation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:508–517.

Sonnenberg A. Seasonal variation of enteric infections and inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:955–959.

Blanck S, Aberra F. Vitamin d deficiency is associated with ulcerative colitis disease activity. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1698–1702.

Jorgensen SP, Hvas CL, Agnholt J, Christensen LA, Heickendorff L, Dahlerup JF. Active Crohn’s disease is associated with low vitamin D levels. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e407–e413.

Ham M, Longhi MS, Lahiff C, Cheifetz A, Robson S, Moss AC. Vitamin D levels in adults with Crohn’s disease are responsive to disease activity and treatment. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:856–860.

El-Matary W, Sikora S, Spady D. Bone mineral density, vitamin D, and disease activity in children newly diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:825–829.

Levin AD, Wadhera V, Leach ST, et al. Vitamin D deficiency in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:830–836.

Dumitrescu G, Mihai C, Dranga M, Prelipcean CC. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and inflammatory bowel disease characteristics in Romania. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2392–2396.

Ananthakrishnan AN, Cagan A, Gainer VS, et al. Normalization of plasma 25-hydroxy vitamin D is associated with reduced risk of surgery in Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1921–1927.

Hlavaty T, Krajcovicova A, Koller T, et al. Higher vitamin D serum concentration increases health related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15787–15796.

Jorgensen SP, Agnholt J, Glerup H, et al. Clinical trial: vitamin D3 treatment in Crohn’s disease—a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:377–383.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The sponsor had no role in the study design, the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Author’s contributions were as follows: AGh and MHE participated in study conception and design. MT prepared the grant proposal. All authors participated in data collection and primary analysis. AGh performed statistical analysis. MT, AGh, and MHE participated in data analysis interpretation. MT, AGh, and LM prepared the manuscript draft. All authors studied, revised, and approved the final version of manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There is no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Torki, M., Gholamrezaei, A., Mirbagher, L. et al. Vitamin D Deficiency Associated with Disease Activity in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Dig Dis Sci 60, 3085–3091 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-015-3727-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-015-3727-4