Abstract

Exposure to a natural disaster can have a myriad of significant and adverse psychological consequences. Children have been identified as a particularly vulnerable population being uniquely susceptible to post-disaster psychological morbidity, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Without effective intervention, the impact of natural disasters on children’s developmental trajectory can be detrimental, however, research is yet to find evidence to definitively establish the comparative efficacy or unequivocal superiority of any specific psychological intervention. A scoping review was undertaken according to the Preferred Reporting Items extension for Scoping Reviews Guidelines (PRISMA-ScR), to evaluate the current research regarding psychological interventions for children (below 18 years of age) experiencing PTSD after exposure to natural disasters, a single incident trauma. Fifteen studies involving 1337 children were included in the review. Overall, psychological interventions, irrespective of type, were associated with statistically significant and sustained reductions in PTSD symptomatology across all symptom clusters. However, whilst evidence supported the general efficacy of psychological interventions in this population, the majority of studies were considered retrospective field research designed in response to the urgent need for clinical service in the aftermath of a natural disaster. Consequently, studies were largely limited by environmental and resource constraints and marked by methodological flaws resulting in diverse and highly heterogeneous data. As such, definitive conclusions regarding the treatment efficacy of specific psychological interventions, and furthermore their ameliorative contributions constituting the necessary mechanisms of change remains largely speculative. As natural disasters can have a catastrophic impact on human lives, establishing levels of evidence for the efficacy of different psychological interventions for children represents a global public health priority.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

It has been estimated that over the next decade, more than 175 million children per year will be affected by natural disasters directly attributed to climate change (Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, 2014). The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines a natural disaster as “an act of nature of such magnitude as to create a catastrophic situation in which day-to-day patterns of life are suddenly disrupted and people are plunged into helplessness and suffering and, as a result, need food, clothing, shelter, medical care and other necessities of life, and protection against unfavourable environmental factors and conditions” (WHO, 1971, p. 14). Each year more than 225 million people are victims of natural disasters worldwide (Lopes et al., 2014). Population growth, economic development, climate change, political instability, eco-system decline, and rapid urbanisation continue to accentuate risk (Bonanno et al., 2010) resulting in a pattern of exponential growth in frequency and severity of natural disasters being predicted (Codreanu et al., 2014; Thomas & López, 2015). As natural disasters can have a catastrophic impact on human lives, they constitute a significant global humanitarian concern of the twenty-first century.

Natural Disasters

Natural disasters are often experienced by communities as large-scale, unpredictable, and potentially traumatic events. Some disasters are centralised to a local community within a well-defined geographical region, whilst others are dispersed and have a broader area of impact (Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council [NHMRC], 2020). Natural disasters can severely disrupt the functioning of a society, cause widespread human, material, economic, and/or environmental losses, whilst causing damage that often exceeds the capacity of the affected community to cope using its own resources (United Nation International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, 2009). The impact of natural disasters on human beings depends on a range of variables including the context in which the disaster occurs (i.e., the magnitude, scale, and intensity of the event), proximal exposure during the disaster itself, and distal exposure to secondary adversities (Bonanno et al., 2010).

Communities affected by disasters often face multiple and diverse challenges. The initial destruction of the physical, biological and/or social environment evident in the immediate aftermath of a disaster can have significant impacts on the acute welfare needs of a population. Such impacts include risks to physical safety/threat to life, loss and bereavement, reduced hygiene, exposure to communicable disease, drinking water supply shortages, interrupted food supplies, displacement and relocation (Brown et al., 2017; NHMRC, 2020). Disasters also generate substantial rebuilding costs and can have long-term social, health and economic consequences. Secondary stressors can endure for years after the disaster itself, including economic resource loss (loss of infrastructure, employment/productivity and income), indirect deaths (related to malnutrition, disease and displacement), interrupted education and mental health issues (Bonanno et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2017).

Psychological Sequelae of Natural Disasters

Research has found that exposure to a natural disaster can have a series of significant and adverse behavioural and psychological consequences. Systematic reviews and longitudinal studies of victims of natural disasters have consistently demonstrated the long-term impact of disaster exposure on individuals’ health and mental well-being. Specifically, evidence indicates a high risk of severe and persistent psychological impairment in survivors of natural disasters (Fergusson et al., 2014; Kar, 2009; Newman et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2013). The far-reaching impact of natural disasters engender a range of psychological sequelae and high exposure to disaster adversity has been identified as a risk factor for mental health disorders (Fergusson et al., 2014).

Psychological Vulnerability in Children

Although a significant portion of the population exposed to a disaster will only experience transient psychological distress, children are uniquely susceptible to post-disaster psychological morbidity (Brown et al., 2017; Fergusson et al., 2014; Newman et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013). Research has found that young victims of natural disasters are at a greater risk of developing psychopathology compared to other populations. Additionally, a high level of psychological distress may not only be prevalent but also persist for many years after disaster exposure in this population (Brown et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2013).

Children have been identified as a particularly vulnerable population with respect to their capacity to prepare for and respond to the impacts of a natural disaster (Codreanu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013). A child’s perception of safety and security is largely impacted by their parents/caregivers’ adaptive functioning. Natural disasters are unique in that they have the capacity to affect the functioning of the entire family system in which the child exists (NHMRC, 2020). The emotional well-being of caregivers in the aftermath of a disaster can impact their availability and emotional responsiveness, influence a child’s appraisal and interpretation of the event, and affect the way in which a child responds, adapts and copes with the trauma (Dorsey et al., 2017; NHMRC, 2020). Disruption to family routine and instability in the mental/physical health of parents/caregivers is often evident in the aftermath of disasters and can have detrimental and lasting impacts on children’s mental health (Codreanu et al., 2014; Freeman et al., 2015).

Research has also found that children have a more limited understanding of their surrounding world, possess fewer coping skills, and often have fewer opportunities to engage in post-disaster community recovery activities compared to other members of the community (Bokszczanin, 2007; Freeman et al., 2015). This is important given that engagement in community recovery activities have been found to facilitate coping by assisting in the emotional processing of the disaster, and by promoting feelings of control. Secondary disaster stressors including separation from family members, insufficient food and water supplies, inadequate hygiene, destruction of homes/displacement, financial hardship, reduced social support, family dysfunction, increased levels of community and interpersonal conflict, and interruption to education, all further contribute to the psychological burden experienced by child victims of natural disasters (Bonanno et al., 2010; Brown et al., 2017; NHMRC, 2020.

In cases where a child’s psychological distress following exposure to a traumatic event persists and significantly interferes with their psychosocial functioning, their response exceeds the parameters that constitute a “normal” trauma reaction and can be indicative of psychopathology (NHMRC, 2020).

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Literature suggests that a significant portion of children will develop psychological impairment after exposure to a potentially traumatic event such as a natural disaster, including depression, anxiety disorders and/or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Brown et al., 2017; Fergusson et al., 2014; Pfefferbaum et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2013). Children are at a greater risk of developing PTSD symptoms due to a wide range of vulnerability factors that make them less resilient and emotionally equipped to process and cope with the traumatic event. As such, PTSD is the most common psychiatric disorder found in children who have experienced a natural disaster and is associated with a high personal, and community health burden (Brown et al., 2017; Pfefferbaum et al., 2019).

PTSD refers to the development of characteristic symptoms that emerge following exposure to a traumatic event and involve a persisting triad of symptoms including re-experiencing the trauma, avoidance of associated stimuli, and increased levels of arousal and hypervigilance (i.e., sense of current threat; Haselgruber et al., 2020; WHO, 2013). PTSD is a debilitating disorder with considerable public health ramifications and is associated with significant distress, psychiatric morbidity and functional impairment (Pfefferbaum et al., 2019; Tang et al., 2017). Untreated, chronic PTSD can have detrimental effects on a child’s social, affective and cognitive development and can impact their quality of life, education and future health outcomes (NHMRC, 2020; Trickey et al., 2012). Furthermore, chronic PTSD increases the risk for developing substance abuse problems, psychiatric comorbidity and long-term psychiatric impairments in adulthood, posing a significant threat to a young person’s developmental trajectory (Hiller et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2013).

Psychological Interventions for Paediatric PTSD

Trauma-focused psychological interventions are currently recommended as the first-line approach for childhood PTSD (Cohen et al., 2010; Australian Government NHMRC, 2020; Australian Psychological Society [APS], 2018; International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies [ISTSS] Guidelines Committee, 2019; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE], 2018; WHO, 2013). According to the recent NHMRC Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (2020), Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (TF-CBT; for the child alone or the child and caregiver) is the recommended treatment choice for children and adolescents with the diagnosis of, or who are at risk of developing clinically relevant posttraumatic stress symptoms. TF-CBT typically utilises psychoeducation, affect regulation skills, cognitive restructuring and exposure strategies to help individuals emotionally process a traumatic event, and modify the maladaptive behaviours (e.g., avoidance) and cognitions (e.g., faulty thinking patterns) that maintain their distress (NHMRC, 2020). Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) has been recommended for situations in which TF-CBT is not feasible. EMDR utilises bilateral stimulation (dual attention, e.g., right/left eye movement, tactile stimulation) to facilitate the adaptive processing of traumatic memories and overwhelming emotions, to reduce distress associated with a traumatic event (NHMRC, 2020).

Treatment Efficacy

The efficacy of evidence-based treatments for PTSD following natural disasters in adults has been well documented in systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Lopes et al., 2014). In comparison, the current body of literature evaluating psychological interventions specifically for children suffering from PTSD is much smaller, especially treatment for paediatric PTSD following single‐incident trauma (Adler-Nevo & Manassis, 2005; Giannopoulou et al., 2006; NICE, 2018). Although obstacles associated with initiating and conducting research in the disaster environment have limited the literature, studies have found preliminary support for the efficacy of psychological interventions for the treatment of PTSD in children exposed to a range of traumas, including natural disasters (Brown et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2014; Pfefferbaum et al., 2019).

A meta-analytic review conducted by Newman et al. (2014) assessed the existing research on psychological interventions for PTSD amongst child and adolescent survivors of natural and man-made disasters. Results suggested that disaster interventions were effective in alleviating PTSD symptoms, more so than a non-treatment alternative. Similarly, a Cochrane meta-analysis by Gillies et al. (2013) found evidence supporting the efficacy of psychological interventions for the treatment of PTSD in children exposed to a range of traumas including natural disasters (Brown et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2014; Pfefferbaum et al., 2019). In line with the current treatment guidelines for paediatric PTSD, TF-CBT was determined to be the most empirically supported psychological intervention (Gillies et al., 2013). Due to the limited number of RCTs, however, the review concluded that there was still insufficient research to understand the long-term efficacy of TF-CBT in this population or to conclusively establish whether any one psychological intervention was more efficacious than another (Gillies et al., 2013).

More recently, a meta-analysis and systematic review by Brown et al. (2017) reviewed the psychosocial interventions for child and adolescent survivors of natural and man-made disasters and found that psychological treatments for PTSD contributed to significant reductions in symptom severity and were more effective than natural recovery (spontaneous remission). However, no significant differences in treatment efficacy between treatment methods were found. The study concluded that all structured treatment approaches which focused on trauma symptoms (CBT, EDMR, Narrative Exposure Therapy for Children [KIDNET]) were effective in reducing the effects of trauma exposure in children. These authors also reiterated the need to focus on different types of disaster (specifically natural disasters vs. man-made disasters).

Research is yet to find sufficient evidence to definitively establish the comparative efficacy or unequivocal superiority of any specific psychological intervention. Consequently, the most effective evidence-based intervention for children following the trauma of a natural disaster remains unclear (Brown et al., 2017; Kline et al., 2018; Newman et al., 2014).

Rationale

Children exposed to the trauma of a natural disaster are a particularly vulnerable population. Research has demonstrated that without decisive and effective psychological intervention, the effects of natural disasters on children’s development may be serious and enduring (Brown et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013). Although there are numerous epidemiological studies and meta-analyses exploring the psychopathology and treatment efficacy of children exposed to a range of traumatic experiences (with recent studies focusing specifically on natural and man-made disasters), to the best of our knowledge, no study has summarized the research relating to natural disasters only. Similarly, whilst numerous interventions for children experiencing PTSD have been delivered and evaluated, it remains unclear which interventions are most effective, for whom, and under what conditions (e.g., Brown et al., 2017; Gillies et al., 2013). Considering the increasing prevalence of natural disasters and the high rates of psychopathological problems in young survivors, the lack of clarity and synthesis of research to guide effective evidence-based child disaster mental health interventions represents a significant gap in current literature and is a major public health concern (Brown et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2014; Taylor & Chemtob, 2004; Wang et al., 2013).

Considering the high risk of persisting psychological impairment in survivors of disasters and the significant public health impact, research guiding the implementation of effective evidence-based treatments for children exposed to natural disasters is paramount (Brown et al., 2017).

Objectives

The purpose of this scoping review is to foster a greater understanding of the existing knowledge of psychological interventions for children (under 18 years of age) experiencing PTSD after exposure to a natural disaster. As this area is yet to be comprehensively reviewed, a scoping review was selected as the most effective strategy to analyse the complex heterogeneous body of research. Furthermore, as a result of the unpredictable nature of natural disasters and the urgent need for immediate psychological support, methodological flaws are inherent in the majority of the research. Scoping reviews provide an overview of existing evidence regardless of quality and offer an avenue to map the current knowledge in a manner which reflects the reality of the current body of literature.

This review will differ from existing evidence syntheses as it will specifically focus on childhood PTSD (below 18 years of age) occurring in the context of exposure to a natural disaster (typically regarded as a single incident traumatic event despite the ongoing nature of sequelae), as opposed to the majority of research in the field which has incorporated a diverse range of natural and man-made traumas amongst the studies examined (Brown et al., 2017; Newman et al., 2014; Pfefferbaum et al., 2019). Specifically, this review aims to evaluate the current evidence-based/body of research, highlight gaps in existing knowledge, clarify key concepts and report on the types of evidence that address and inform practice in the field, guide future research and contribute to improving the consistency and efficacy of disaster interventions for children.

Method

A scoping review of the literature was undertaken according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews Guidelines (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018). Searches were conducted across four electronic psychological and medical databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, and CINAHL). The search strategies were drafted and refined in conjunction with an experienced librarian from The University of Queensland. Variants of keywords that fit within five clusters of search strings and combined with the “AND” function were used to conduct the search:

(I) age group/population (children; below 18 years of age), (II) natural disasters (“an act of such magnitude as to create a catastrophic situation in which the day-to-day patterns of life are suddenly disrupted…”; WHO, 1971), (III) PTSD, (IV) interventions (psychological interventions targeted to address symptoms of PTSD), (V) treatment efficacy (treatment outcomes). The final search strategy can be found in Appendix 1, Table 1.

Study eligibility was assessed by one reviewer who systematically screened titles, abstracts and relevant full texts according to specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. To be included in the review, journal articles needed to be published in English between 1980 (date in which PTSD was first formally considered a diagnosis by the American Psychiatric Association and included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-III; American Psychiatric Association, 1980) and April 2021 (date final search was conducted). Studies included quantitative, qualitative, mixed-method studies, systematic reviews and meta-analyses to account for the diversity of methods currently used to measure PTSD symptomology and treatment efficacy within the specified population. In order to be eligible for inclusion, studies were required to meet the following criteria:

-

Demonstrate the implementation of a psychological intervention

-

Administered to a child population (below 18 years of age)

-

Participants experiencing/experienced PTSD symptoms following their exposure to a natural disaster (single incident trauma)

-

Include a formal measure of PTSD administered pre- and post-intervention to XXmonitor treatment efficacy

Studies were excluded if they:

-

Were published prior to 1980

-

Were published in a language other than English

-

Included participants/population above 18 years of age

-

Did not include a formal measure of PTSD symptoms

-

Did not include a follow-up measure of PTSD post-treatment

-

Included other or multiple forms of disasters (e.g., accidents, inter-personal violence, or man-made disasters such as terrorism or war)

Due to the highly limited body of literature, there were no specifications made on the treatment modality; administration modality (e.g., group or individual); administering practitioner (e.g., psychiatrist or trained teacher); or the timeframe within which treatment was administered post-disaster. There were also no restrictions imposed on the diagnostic tools used to measure PTSD symptomatology and/or treatment outcomes, as long as they were applied consistently for the duration of the study.

The final search results were exported into Endnote and then uploaded to the Covidence Systematic Review Software where all duplicates were removed. Articles were systematically screened according to the specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. An informal critical appraisal of the validity of the analytical methods and methodological quality of individual sources of evidence was conducted. The data-charting form was developed by the primary reviewer to determine which variables to extract. Data were extracted based on key conceptual categories identified including:

-

Article Characteristics (e.g., country of origin, study design)

-

Population Demographics (e.g., age, type of trauma exposure/natural disaster)

-

Intervention Characteristics (e.g., group or individual, timing of intervention post-disaster, follow-up duration post-intervention, duration of intervention, providers’ qualification/training, PTSD diagnostic and outcome measures)

-

Intervention Efficacy

The data extracted from the included papers are presented in tabular and narrative formats which aimed to systematically map and examine the current psychological interventions used to treat PTSD symptomology in trauma affected children (see Appendices 2 and 3 for Data Extraction Tables 2 and 3).

Results

A total of 194 studies were imported for screening to the Covidence Systematic Review Software. Eighty-eight duplicates were removed. The titles and abstracts of 106 studies were screened and 47 studies were excluded. The full texts of 59 studies were assessed for eligibility, and 44 studies were excluded as they did not meet inclusion criteria. A total of 15 studies were identified for final inclusion. A PRISMA flow diagram detailing the steps of the study review process and reasons for exclusion is provided in Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009)

A descriptive summary of the key characteristics and main findings from the reviewed studies are explored below.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

The vast majority of the included studies were considered retrospective field research conducted as a clinical response to the urgent need for psychological assistance in the aftermath of a natural disaster. The psychological interventions were considered clinical service activities with the primary purpose being to provide effective relief to as many children as possible, within the constraints of limited resources. Consequently, the studies did not always meet the traditional criteria for controlled experimental research and consisted of demographically homogenous populations predominantly determined by circumstance and need. The majority of the studies employed a quasi-experimental research design. These consisted of a combination of quasi-randomised controlled trials, quasi-control series designs, non-equivalent control group pre-test post-test quasi-experimental designs, quasi-experimental one group pre-test post-test design, and basic time-series quasi-experimental designs.

Of the 15 studies included in this paper, four did not clearly state whether participants met criteria for a probable PTSD diagnosis (Adúriz et al., 2011; Pityaratstian et al., 2007; Vijayakumar et al., 2006; and Goenjian et al., 2005). The study conducted by Goenjian et al., (2005) was a follow-up of participants from another included study (Goenjian et al., 1997) where it is clearly noted that criteria for a probable PTSD diagnosis were met. Two of the remaining three studies presented pre-treatment results that clearly indicate that means for all participants were above the clinical cut-off on the measure used in their study for a probable PTSD diagnosis. One study however (Pityaratstian et al., 2007) had a sample where participants were split according to whether they scored above or below the cut-off for a probable PTSD diagnosis. Fortunately, post-treatment results for participants scoring above and below the cut-off at pre-treatment were clearly differentiated and this manuscript reports only on the participants from this study who scored above the clinical cut-off for a probable PTSD diagnosis. In relation to the PTSD diagnosis, the 15 studies used the DSM-III-R, DSM-IV or DSM-IV-TR criteria.

Of the 15 studies reviewed, only seven reported having a control group (Berger & Gelkopf, 2009; Chemtob et al., 2002a; Chen et al., 2014; Goenjian et al., 1997, 2005; Pityaratstian et al., 2015; Vijayakumar et al., 2006). Two reported the use of non-equivalent control groups (Chemtob et al., 2002b; Eksi & Braun, 2009), and six did not report utilising a control group in their study design due to ethical and/or environmental limitations (Adúriz et al., 2011; Catani et al., 2009; Fernandez, 2007; Giannopoulou et al., 2006; Pityaratstian et al., 2007; Taylor & Weems, 2011).

In terms of geographical scope, studies were published in 10 different countries across four continents. Fifty-three percent were published in Asia (China, India, Thailand, Sri Lanka), 20% in Europe (Italy, Turkey, Greece), 20% in North America (USA), and 7% in South America (Argentina). Amongst the included studies, 60% were conducted in countries considered to be “developing” (World Trade Organization, 2020).

Across all 15 studies reviewed only four natural disaster events were studied, with 40% reviewing the impact of exposure to an earthquake; 33%, a tsunami; 20% a hurricane; and 7% floods.

Overall, there is a limited quantity of published literature which explores the treatment of PTSD in children after exposure to natural disasters. However, there was evidence of a notable increase in publications over the past two decades with 93% of studies published between 2000 and 2020 and only 7% published prior to 2000. Roughly 26% of papers were published in the past decade (2010–2020). Only 7% were published in the 5 years prior to the current review.

Characteristics of Population

Overall, 1337 children (M = 11.4 years, range 6–17 years, 40% male) were included in the studies described in this review. Eighty percent of the children were recruited from local schools situated within communities affected by the natural disaster, 7% were recruited from refugee camps, 7% from the local village and 7% were referred from Child Mental Health Services.

Characteristics of Psychological Interventions

A diverse range of psychological based interventions were administered in the reviewed studies. When assessing the characteristics of these interventions it is necessary to understand the context in which they were delivered. Treatment selection, implementation, and capacity appeared to be largely determined by environmental constraints including the multiplicity of hardships facing both victims and staff working within the disaster zones, lack of available mental health personnel, and limited clinical resources. Most studies focused on group differences as a means to measure change, as the circumstance of mass trauma involving large populations often exceeded the possibility for individual treatment. The majority of the studies explicitly described treatment procedures as ‘crisis interventions’ and were designed for the provision of clinical service rather than experimental research, resulting in diverse and highly heterogenous data.

The degree to which the treatments utilised were considered evidence-based psychological interventions (i.e. psychological interventions considered best practice for the treatment of paediatric PTSD according to: Cohen et al., 2010; APS, 2018; International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies [ISTSS] Guidelines Committee, 2019; NHMRC, 2020; NICE, 2018; WHO, 2013) varied according to the content of the treatment (i.e., theoretical underpinning, psychometric validity and reliability of diagnostic tools/measures utilised), treatment fidelity (i.e., the degree to which the treatment protocol was implemented as intended), resource and environmental constraints (i.e., the degree to which the treatment was limited by access to trained professionals, language/ translated materials, relocating displaced children, etc.). Although many of the studies reported employing interventions considered best practice such as TF-CBT and EMDR, the degree to which they were implemented in a scientifically rigorous manner that reflected the evidence-based treatment approach differed significantly across studies, was at times difficult to ascertain, and was heavily influenced by external factors.

Type of Intervention

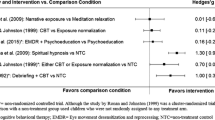

Of the 15 studies reviewed, five described their interventions as based on TF-CBT (Chen et al., 2014; Giannopoulou et al., 2006; Pityaratstian et al., 2007, 2015; Taylor & Weems, 2011) with another describing their treatment as a combination of TF-CBT and Psychopharmacology (Eksi & Braun, 2009). Three described employing EMDR (Adúriz et al., 2011; Chemtob et al., 2002a; Fernandez, 2007), two described utilising Trauma and Grief-Focused Psychotherapy (Goenjian et al., 1997, 2005), one described following KIDNET (Catani et al., 2009), and three did not report following a specific treatment or theoretical framework and instead described using a combination of empirically and non-empirically based strategies including; ‘culturally targeted group interventions’, ‘emotion identification’, ‘meditative practices’, ‘art techniques’ and ‘counselling’ (Berger & Gelkopf, 2009; Chemtob et al., 2002b; Vijayakumar et al., 2006). The distribution of psychological interventions (as described in the studies) is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Of these interventions, some of the studies described employing manualised evidence-based treatment programmes such as; the short-term group TF-CBT intervention adapted from the manual ‘Children and Disaster: Teaching Recovery Techniques’ (Chen et al., 2014; Smith et al., 1999), and the ‘EMDR Standard Protocol’ (Adúriz et al., 2011; Fernandez, 2007; Shapiro & Forrest, 2001). Some interventions reported employing evidence-based treatment strategies implemented via a novel programme, e.g., the TF-CBT based ‘StArT Treatment Manual for Hurricane Exposed Youth’ (Taylor & Weems, 2011), whilst others described semi-structured programmes based on a combination of evidence-based and non-evidence-based treatment strategies such as the ‘ERASE Stress Sri Lanka’ programme (ES-SL; Berger & Gelkopf, 2009). Only one study explicitly stated that the intervention used was not adequately validated and tested (Vijayakumar et al., 2006).

Treatment Modality

In terms of treatment modality, seven of the 15 studies reported employing a group style intervention (Adúriz et al., 2011; Berger & Gelkopf, 2009; Chen et al., 2014; Giannopoulou et al., 2006; Pityaratstian et al., 2007, 2015; Vijayakumar et al., 2006), five reported utilising individual interventions (Catani et al., 2009; Chemtob et al., 2002a; Eksi & Braun, 2009; Fernandez, 2007; Taylor & Weems, 2011), and three studies reported using a combination of individual and group interventions (Chemtob et al., 2002b; Goenjian et al., 1997, 2005). Only one study compared group and individual treatment and found no statistically significant differences in treatment efficacy. However, results from this study indicated that children receiving the group treatment were significantly more likely to complete treatment than those receiving individual treatment (Chemtob et al., 2002b).

Providers’ Level of Training

A wide range of individuals with varying levels of training and experience assisted in conducting the interventions. Considering the context of natural disasters and the urgent need for intervention, resources and access to trained professionals were often limited, resulting in a reliance on volunteers and members of the community. Geographical and cultural diversity also contributed to the high levels of variability evident in those facilitating the interventions. Upon review of the included studies, it was observed that there was often a degree of ambiguity in language used to describe the level of training and expertise of these individuals. This was likely the result of the diverse terminology used to describe the professionals, and a lack of specificity regarding their professional credentials. For instance, the following terms were used to describe the facilitators of the interventions: ‘Mental Health Care professionals’, ‘Clinicians’, ‘Psychiatric Outreach Programme Staff’, ‘Psychologists’, ‘Psychiatrists’, ‘School Counsellors’, ‘Clinical Social Worker’, ‘Masters level graduate students’, ‘doctoral-level graduate students’, ‘Doctoral Level Clinicians’, ‘Volunteers’, ‘local counsellors’ or ‘Teachers’.

In some studies, the level of expertise/training was regulated to a degree. For instance, Fernandez (2007, p. 67) described providers as “clinicians [who] belonged to the National EMDR Association”, whilst Eksi and Braun (2009, p. 386) reported that “certified child-adolescent psychiatrists” were employed. Other studies were less clear with respect to the qualifications or experience of the facilitators but provided information outlining the training and/or supervision undertaken (e.g., “therapists received 3 days of training regarding post-disaster trauma psychology and a day and a half of didactic training specific to the treatment manual”; Chemtob et al., 2002b). However, in the majority of studies neither the qualifications nor prior training (training in the intervention specifically or in the field more broadly) of the individuals administering the interventions were made explicit.

Duration of Treatment

Similarly, treatment duration was also highly diverse and largely impacted by participant and resource accessibility. For instance, in the study by Catani et al. (2009), the entire coast of Sri Lanka’s North East had been destroyed significantly impacting transportation and communication, and participants had been recruited, and treatment conducted in two provisional refugee camps. As such, treatment duration was limited to six sessions to ensure that the intervention could be completed before the children were relocated to permanent shelters. Consistent with current research, school-based interventions (conducted in a school environment) were found to be a natural and effective means to overcome common treatment barriers (e.g., access, stigma, transportation, etc.) and provided an effective environment to accomplish mass screening, treatment and monitoring of a large population of children over a longer duration of time (Jaycox et al., 2010; NHMRC, 2020; Rolfsnes & Idsoe, 2011).

Treatment duration ranged from brief intensive interventions (i.e., conducted over 2/3 days; Adúriz et al., 2011; Pityaratstian et al., 2007, 2015), to short-term interventions (i.e., with one or multiple sessions conducted on a weekly basis for a month or less; Catani et al., 2009; Chemtob et al., 2002a, 2002b; Goenjian et al., 1997, 2005), and longer-term interventions (i.e., implemented over more than one month; Berger & Gelkopf, 2009; Chen et al., 2014; Eksi & Braun, 2009; Fernandez, 2007; Giannopoulou et al., 2006; Taylor & Weems, 2011; Vijayakumar et al., 2006). Notably, there were no studies which specifically compared the difference in efficacy of different treatment lengths; however, analyses of results did not demonstrate any obvious differences in treatment efficacy based on intervention duration.

Commencement of Treatment Post-Disaster

Of the 15 studies, six reported they had commenced treatment between 1 and- 3 months post-disaster (Adúriz et al., 2011; Catani et al., 2009; Eksi & Braun, 2009; Fernandez, 2007; Giannopoulou et al., 2006; Pityaratstian et al., 2007), another four reported commencing treatment within 18 months post-disaster (Berger & Gelkopf, 2009; Goenjian et al., 1997, 2005; Vijayakumar et al., 2006).

and five studies reported commencing treatment more than 2 years after the disaster had occurred (Chemtob et al., 2002a, 2002b; Chen et al., 2014; Pityaratstian et al., 2015; Taylor & Weems, 2011). All of the interventions exceeded the one-month mark, thus allowing symptoms that would remit with Acute Stress Disorder to resolve prior to treatment. There was no clear, high-quality evidence relating to the timing of the intervention in relationship to intervention efficacy. Interventions were found to be efficacious across a wide range of commencement times, and significant reductions in PTSD symptoms were evident irrespective of when the treatment was administered post-disaster.

Follow-Up Intervals Post-Intervention

Whilst it was a criterion for inclusion of this review that all studies provided pre- and post-outcome measures, many of the studies also provided longer-term follow-up measures that offered information regarding the sustained reduction of symptoms and maintenance of treatment effects over time. Once again, the duration of follow-up intervals post-intervention ranged greatly and were significantly impacted by external factors beyond the authors’ control. For instance, the study conducted by Catani et al. (2009) was designed with the inclusion of a one-year post-treatment follow-up. However, this was unable to be completed due to the increasing violence and political insecurity in the area at the time.

Of the 15 studies, five reported conducting follow-up assessments within 3 months of completion of the intervention (Adúriz et al., 2011; Berger & Gelkopf, 2009; Chen et al., 2014; Pityaratstian et al., 2007, 2015). A further five reported conducting follow-up assessments between 6 months and one-year post-treatment (Catani et al., 2009; Chemtob et al., 2002a, 2002b; Fernandez, 2007; Vijayakumar et al., 2006). Only four of the initial 15 reviewed studies reported providing longer-term follow-up outcome measures occurring at 18 months or longer, post-treatment (Eksi & Braun, 2009; Giannopoulou et al., 2006; Goenjian et al., 1997, 2005). One study did not complete any follow-up after the post-treatment outcome measure (Taylor & Weems, 2011). A large portion of the research was established within the initial acute phase in the aftermath of the disaster and primarily focused on immediate symptom reduction using relatively short-term outcome measures. Considering the potential chronicity of PTSD, longitudinal assessments are critical in understanding the long-term efficacy and sustained impacts of psychological interventions (Kline et al., 2018; Wolmer et al., 2005).

Diagnostic and Outcome Measures

Of the 15 studies evaluated, seven relied solely on self-report questionnaires administered to the children (Adúriz et al., 2011; Berger & Gelkopf, 2009; Chen et al., 2014; Goenjian et al., 1997, 2005; Pityaratstian et al., 2007; Vijayakumar et al., 2006). Three performed diagnostic interviews with the children (Catani et al., 2009; Eksi & Braun, 2009; Fernandez, 2007). Three used a combination of self-report questionnaires and diagnostic interviews administered to the children (Chemtob et al., 2002a, 2002b; Pityaratstian et al., 2015). Only two studies employed multi-informant and multi-method approach, utilising diagnostic interviews and self-report questionnaires administered to the children and parents (Giannopoulou et al., 2006; Taylor & Weems, 2011), despite current research emphasising the importance of utilising a multi-method, multi-informant approach in the evaluation of paediatric PTSD (Grant et al., 2020; NHMRC, 2020). The majority of studies relied heavily on self-report by the children and did not integrate collateral information from family members to inform diagnoses.

The most common measures consisted of brief self-report style questionnaires such as the Child’s Reaction to Traumatic Events Scale (CRTES; Jones, 1996), the Children’s Revised Impact of Events Scale (CRIES; Smith et al., 2003), the Childhood Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (CPTSD-RI; Pynoos et al., 1987), and the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV (UCLA-PTSD-RI, child version; Steinberg et al., 2013). Other common measures employed required administration and interpretation by a trained professional and included the Structured Clinical Interview used to ascertain a DSM-IV TR PTSD diagnoses (SCID-1; Werner, 2001) and the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale child/adolescent version (CAPS-CA; Pynoos et al., 2015).

Although the majority of diagnostic/outcome measures utilised were psychometrically validated, accessibility was limited by language, cultural appropriateness, and educational requirements. Whilst the majority of measures selected maintained high levels of validity and reliability when translated, this was not consistent and posed a significant limitation in measuring PTSD symptomatology and monitoring treatment efficacy. For example, in the study by Eksi and Braun (2009), the adult version of the CAPS diagnostic interview was administered as the child version had not been standardised in Turkish at the time. Similarly, in the study by Pityaratstian et al. (2007) the researchers encountered issues when implementing the CRIES as it had not been validated in Thai. There are limited cost-effective and psychometrically valid screening and diagnostic tools available for the identification of PTSD in a child population (Hawkins & Radcliffe, 2005). This is evident in the lack of consistency and standardisation of measures utilised in the current literature.

Intervention Efficacy

Despite 13 of the 15 reviewed studies finding significant reductions in PTSD symptomology following a psychological intervention, the diversity of the populations (cultural background, sample size, ages, presence of comorbid mental health disorders, level of trauma exposure) intervention designs, diagnostic measurement tools and characteristics of their application (duration, frequency, format), prevents direct quantitative comparison across studies. As such, it is not possible to determine whether a particular treatment was more effective than another treatment. The complex heterogenous nature of the results depicted in the reviewed studies do not lend themselves to precise quantitative comparison; however, key themes and patterns were evident.

Characteristics of Outcome Measurement

Effective interventions were operationalised as those that produced a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms. Where a control group was utilised, efficacy was ascertained when individuals who received treatment, demonstrated statistically significant reductions in PTSD symptomatology (on a psychometrically validated PTSD symptom outcome measure) when compared to those who had not received treatment (control group/waitlist). In the studies that did not report the use of a control group, meaningful symptom reduction was indicated by a statistically significant decrease in mean scores on psychometrically validated measures of PTSD, evident when comparing pre- and post-treatment scores on PTSD symptom outcome measures (Adúriz et al., 2011; Giannopoulou et al., 2006; Pityaratstian et al., 2007; Taylor & Weems, 2011). Treatment efficacy was also established by comparing the proportion of participants who met the DSM-IV criteria for PTSD pre- and post-treatment (Fernandez, 2007) or by comparing the degree of PTSD symptomatology experienced by individuals in a treatment group (as indicated by a psychometric outcome measure) against a hypothetical rate of expected natural recovery. Treatment was considered effective when the recovery rates in the treatment groups exceeded the expected rates of natural recovery, suggesting that overall, treatment was more effective than the non-treatment alternative (Catani et al., 2009; Fernandez, 2007).

Type of Intervention and Treatment Efficacy

Overall, five of the six studies which reported incorporating a TF-CBT based treatment approach were associated with statistically significant reductions of PTSD symptoms (Chen et al., 2014; Giannopoulou et al., 2006; Pityaratstian et al., 2007, 2015; Taylor & Weems, 2011). These improvements were consistently sustained over time, and treatment was found to be more effective in alleviating PTSD symptoms compared to no treatment. Eksi and Braun (2009) reportedly used a combination of TF-CBT and psychopharmacological treatment and did not find statistically significant differences in PTSD symptoms between the treatment and control group. However, this discrepancy was hypothesised to be the result of methodological issues rather than the type of intervention.

All three of the studies which reported using an EMDR treatment approach found statistically significant and sustained improvements in PTSD symptoms (Adúriz et al., 2011; Chemtob et al., 2002a; Fernandez, 2007). EMDR was also associated with reductions in the number of children who met the diagnostic criteria for PTSD.

Two studies reported basing their intervention on trauma/grief-focused psychotherapy, and both found treatment to be effective in alleviating PTSD symptoms (Goenjian et al., 1997, 2005). Specifically, treatment was associated with significant reductions in symptom severity.

Catani et al. (2009) compared KIDNET and Meditation-Relaxation protocol (MED-RELAX). Significant reductions in PTSD symptoms were evident in both treatment conditions with recovery rates in both conditions exceeding the expected rates of natural recovery. No significant differences in treatment efficacy were observed between treatment conditions.

Three studies did not report utilising a singular treatment or theoretical framework. Chemtob et al. (2002b) used a novel school-based, manualised disaster recovery programme. Similarly, Berger and Gelkopf (2009) trialled a semi-structured classroom-based programme consisting of psychoeducation, cognitive behavioural skills, meditative practices, bio-energetic exercises art therapy and narrative techniques. Both studies found significant reductions in self-reported PTSD symptom severity in children who received treatment compared to children in the control group/waitlist. Vijayakumar et al. (2006) employed a novel culturally targeted group intervention treatment protocol; however, treatment was not associated with significant reduction in PTSD symptoms.

Although the majority of the studies found treatment to be associated with reductions in PTSD symptoms, most studies also indicated that children remained ‘symptomatic’ post-treatment. However, there was no consistency in when and how this was defined and measured. For instance, Adúriz et al. (2011) reported that 23% of children demonstrated clinical levels of PTSD 3 months post-treatment, whereas Fernandez (2007) evaluated the percentage of children who still met the PTSD criteria at one-year post treatment. Comparatively, Goenjian et al. (1997) provided less detail, only indicating that some children still experienced moderate levels of PTSD symptoms 18 months post-treatment.

Key Findings

Overall, psychological interventions were associated with significant reductions in PTSD symptoms across all symptom clusters, irrespective of the treatment type modality or training/qualification of the provider. Psychological interventions were found to contribute to significant reductions in psychological distress, self-reported trauma symptoms and psychosocial dysfunction. Critically, treatment was found to facilitate the adaptive processing of traumatic experiences (Fernandez, 2007). After receiving treatment, many of the children demonstrated positive cognitive, behavioural and emotional changes (Adúriz et al., 2011), utilised versatile coping resources (Fernandez, 2007), displayed more adaptive perspectives and beliefs of the traumatic event, a detachment from the past, and a greater focus on the present and future (Adúriz et al., 2011). Children displayed an increased tolerance of re-experiencing phenomena and reduced physiological and psychological reactivity to traumatic reminders (Goenjian et al., 2005). Treatment was also consistently associated with improvements in psychosocial functioning and quality of life (Catani et al., 2009; Giannopoulou et al., 2006). Other patterns of results that emerged included the increased vulnerability to posttraumatic stress reactions in younger children (Adúriz et al., 2011; Chemtob et al., 2002b), and amongst the female sex (Adúriz et al., 2011; Chemtob et al., 2002b; Goenjian et al., 2005). Although converging evidence indicated that being female was a risk factor for developing higher levels PTSD symptomatology, the research did not find any difference in treatment efficacy, suggesting that both genders respond equally to treatment (Adúriz et al., 2011; Goenjian et al., 2005). Despite significant improvements in PTSD symptoms after psychological intervention, in the majority of studies, treatment did not result in the complete remission of PTSD and many children remained symptomatic at post-treatment follow-up assessments.

Discussion

This scoping review was conducted to foster a greater understanding of the existing knowledge of psychological interventions for children experiencing PTSD after exposure to a natural disaster. The review aimed to map and evaluate the current evidence-based, highlight gaps in the existing literature, guide future research, and contribute to improving the consistency and future efficacy of disaster interventions for children. One hundred and six studies were screened for eligibility, and a total of 15 studies involving 1337 children (below 18 years of age) were included in the review.

Summary of Current Evidence-Based and Key Findings

Overall, psychological interventions, irrespective of type, were associated with statistically significant and sustained reductions in PTSD symptomatology across all symptom clusters. Treatment was found to facilitate the adaptive processing of traumatic experiences (Fernandez, 2007) and reduce physiological and psychological reactivity to trauma reminders (Goenjian et al., 2005). Interventions were also associated with significant reductions in children’s self-reported psychological distress and were found to improve psychosocial functioning and quality of life (Catani et al., 2009; Giannopoulou et al., 2006). Unfortunately, due to the highly heterogenous nature of the sample populations (cultural background, sample size, age, presence of comorbid and/or pre-existing mental health disorders, level of trauma exposure), intervention designs, diagnostic measurement tools, and characteristics of treatment application (i.e., modality, duration, providers’ level of training), direct comparisons between intervention type and treatment efficacy were not feasible. As such, definitive conclusions regarding the status of the current evidence base with respect to treatment efficacy for specific psychological interventions remain unclear.

In terms of treatment modality, there was no clear, high-quality evidence comparing individual and group treatment in relation to intervention efficacy. However, results indicated that children receiving the group treatment were significantly more likely to complete treatment than those receiving individual treatment (Chemtob et al., 2002b). Similarly, there was no clear, high-quality evidence relating to the timing of the intervention nor the duration of treatment, in relationship to intervention efficacy.

There was considerable variability in the level of expertise of the individuals facilitating the psychological interventions. Diverse terminology, geographical and cultural diversity, and a reliance on community volunteers resulted in high levels of ambiguity regarding the qualifications, prior training (training in the intervention specifically, or in the field more broadly), and experience of the individuals administering the interventions. As such, no specific conclusions can be drawn with respect to the influence of provider training on treatment efficacy. Considering that adequate training and supervision are key components of effective psychological interventions and necessary to assure fidelity and adherence in treatment delivery (Newman et al., 2014), the lack of provider training specificity hinders current research.

With respect to treatment location, services delivered in schools were found to be the most effective environment to accomplish mass screening, treatment, and monitoring of a large population of children. Whilst there were no studies which specifically evaluated treatment location as a component of treatment efficacy, findings were largely consistent with research and current Australian guidelines that support school-based interventions as the first-line response (Jaycox et al., 2010; NHMRC, 2020; Rolfsnes & Idsoe, 2011). Schools represent a (mostly) accessible, convenient and affordable venue for providing mental health services to children. They can offer continuity and stability of treatment, provide peer support, and represent a natural and effective location to overcome common treatment barriers (e.g., access, stigma, transportation, etc.; Newman et al., 2014; NHMRC, 2020). However, it is important to note that school-based interventions exclude children who are denied access to an education or children who are unable to attend school in person for medical and/or other reasons. Ensuring that unequal opportunities for education are not a barrier to accessing treatment is imperative for the provision of equitable mental health care.

Although psychological interventions were found to be more effective than any non-treatment alternative in alleviating symptoms, psychological interventions did not result in the complete remission of PTSD in all participants; many children remained symptomatic at post-treatment follow-up assessments. In line with past research, the current body of literature provides insufficient evidence to definitively establish the comparative efficacy or unequivocal superiority of any specific psychological intervention for the treatment of childhood PTSD in the context of a natural disaster (Brown et al., 2017; Kline et al., 2018; Newman et al., 2014).

Critical Evaluation of the Current Body of Literature

The majority of the studies were considered retrospective field research designed and implemented in response to the urgent need for psychological support in the aftermath of a natural disaster. Consequently, treatment selection, implementation, and capacity were largely determined by environmental and resource constraints and marked by methodological flaws. Whilst it is acknowledged that many of the limitations discussed below were largely the result of the unique contextual factors associated with conducting research in a disaster zone, a critical evaluation of the literature is essential for understanding the current evidence base, identifying areas for improvement, and informing future intervention development.

Methodological Design

A common methodological issue observed was the complete absence of, or non-equivalent, control group. Considering that the majority of research was conducted during the acute phase following a natural disaster, the population was determined by the circumstances of an emergency situation, and resources were used to help the greatest number of victims. Ethically children required treatment on an equitable basis and, consequently, many studies were unable to exclude a group of children from receiving treatment. This resulted in a consistent pattern of studies that did not include control groups in their design. In some studies, a partial control group was utilised; however, these commonly comprised children who were considered less symptomatic than the treatment group and thus were not equivalent. The absence of control groups limited the degree to which the studies could determine causal relationships and ascertain if, and to what extent, the observed changes were attributable to the psychological intervention. It also restricted the capacity for experiments to control for external processes influencing outcomes, occurring independent of treatment, leaving the data vulnerable to confounding variables such as familial support, community response, secondary disaster stressors and natural recovery. This methodological design also resulted in a recurrent lack of comparison between child survivors and unaffected children of a similar context, limiting the generalisability of the results.

A lack of uniformity across studies with respect to the type of psychological intervention, diagnostic and outcome measurement tools, treatment modality, length, timing, setting and providers’ level of training was highly prevalent in the current literature and limited direct comparisons between research. The heterogeneity of sampling approaches, characteristics and sizes, coupled with the diverse personal characteristics of the children participating in the studies’ further limits cross-study comparison. The reliance on cluster or convenience sampling methods resulted in ethnically, culturally and religiously homogenous samples, which did not provide a consistently representative sample reflective of the broader population, further limiting the external validity and generalisability of the findings.

Pre-existing Psychopathology

Many of the studies did not account for, nor measure, pre-existing and/or comorbid mental health conditions, despite research demonstrating high levels of psychiatric comorbidity in children experiencing PTSD (Marthoenis et al., 2019). As such, ascertaining the extent to which the observed psychopathology (PTSD) was the result of the disaster-related trauma (exposure to the natural disaster) and, furthermore, determining the degree to which the changes in symptomatology were attributable to the treatment intervention was limited, raising concerns with respect to construct validity and attribution biases. As comorbidities have the potential to exacerbate PTSD, interfere with treatment and influence the trajectory of recovery, an understanding of co-occurring psychopathology is critical (Jaycox et al., 2010; NHMRC, 2020).

Past-Trauma Exposure

Similarly, a large majority of the literature did not collect information regarding prior traumatic experiences and thus, did not consider the compounding and cumulative nature of multiple traumas on propensity to develop greater PTSD morbidity (Cicero et al., 2011). Past exposure to traumatic events has been associated with an increased vulnerability to new traumatic events, it has also been associated with facilitating resilience and acting as a protective factor for future events. The assessment of historical trauma exposure is essential for the effective evaluation and treatment of PTSD, however, is frequently excluded from the current research (Jaycox et al., 2010; NHMRC, 2020).

Secondary Stressors and Enduring Adversity

In the same notion, ongoing adversity and secondary stressors may also affect a child’s recovery pattern. A diagnosis of PTSD references symptoms commencing immediately after or in response to the cessation of a trauma. However, in many post-disaster situations, although the critical incident (natural disaster) may have occurred months prior, the consequences of the event extend into the ensuing months, in which children can be exposed to unremitting post-disaster stressors and adversities including inadequate food and shelter, impoverish environments, financial hardships, unemployment, mass displacement and grief and loss. In turn, children may experience prolonged periods of stress and ongoing threats that can, in some cases, be characterised as one continuous traumatic event, making it difficult to ascertain the parameters of the trauma. This raises questions regarding the ability to establish conclusive PTSD diagnoses and validly establish treatment efficacy in post-disaster environments.

Diagnostic and Outcome Measures

A lack of consistency and standardisation in diagnostic and outcome measures used for paediatric PTSD is a highly prevalent issue in the current literature. Inconsistent diagnostic tools limit opportunities for direct comparison of results across research from multiple disasters. Furthermore, despite current research emphasising the importance of a multi-method, multi-informant approach, brief self-report style questionnaires remain the dominant method used in the evaluation of PTSD in children and adolescents (Grant et al., 2020; NHMRC, 2020). This over-reliance on single-informant self-report measures produces subjective data, largely influenced by the child’s introspective ability, and is subject to response biases. Furthermore, an understanding of the child’s home context is critical in identifying influences external to the administered treatment that may play a central role in the child’s recovery. Single-informant self-report methods limit opportunities for obtaining collateral information regarding the children’s home life, social support and caregiver response. As such, research is potentially overlooking critical factors (risk or protective) that may impact a child’s functioning, trauma reaction, development of PTSD and response to treatment (Cicero et al., 2011).

The assessment of childhood PTSD is impeded by the limited number of cost-effective and psychometrically valid screening and diagnostic tools available (Hawkins & Radcliffe, 2005; NHMRC, 2020). Consequently, the tools utilised are often revisions of adult measures that are used to assess children of large age-ranges (e.g., the Child PTSD Reaction Index is used to assess children 6–18 years of age). As these measures lack age-sensitivity they fail to account for the developmental differences and unique clinical presentations of PTSD evident in different stages of childhood, raising concerns for the validity of the assessment and the reliability of comparisons between children of different age ranges (NHMRC, 2020). Of the measures employed, many were developed and validated in western countries and consequently required translation and/or cultural adaptation. Furthermore, a certain level of educational proficiency is required by many of the measures (for both the administrators of the assessments and of the children being assessed) to ensure children were able to understand and respond to the questions appropriately. As such, accessibility to diagnostic tools and outcome measures appear limited by language, culture, and educational prerequisites.

Gaps in Existing Literature and Recommendations for Future Research

Considering the high risk of severe and persistent psychological impairment in survivors of natural disasters and the unique susceptibly of children to post-disaster psychological morbidity (Brown et al., 2017; Fergusson et al., 2014; Newman et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013), the extremely limited quantity of research on psychological interventions for children experiencing PTSD after exposure to natural disasters represents a significant gap in the evidence-based.

The limited number of studies, vast diversity in terminology, heterogeneity in research methodology and inconsistent measurement tools make it difficult to perform reliable comparisons or synthesise the research. Specifically, the field is lacking longitudinal research and randomised controlled effectiveness trials. There is currently an insufficient quantity of methodologically high-quality data or evidence to definitively establish whether different interventions differ in efficacy and ascertain which components of treatment are responsible for alleviating PTSD symptoms in this population. Furthermore, the optimal duration of treatment, timing of treatment post-disaster, setting for intervention delivery and influence of pre-existing conditions and/or traumas on treatment efficacy remains unknown.

Ultimately, more high-quality research with specific attention to methodological design is needed to compare independent psychological interventions, determine efficacy and untangle confounding variables to advance the field. Future studies should endeavour to dismantle the current psychological interventions to identify the common mechanisms shared across effective treatments with the aim of isolating and distilling which components are the necessary curative factors.

Strengths and Limitations of Review

This review adhered to the current guidelines for conducting scoping reviews by closely following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews Guidelines (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018). A comprehensive and structured search of the literature was conducted using a combination of four electronic psychological and medical databases (PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, and CINAHL) to ensure a comprehensive search. The research evidence synthesis consisted of a rigorous, replicable and systematic aggregation of information, and a concerted effort was made in striking the balance between sensitivity (accessing all relevant articles) and specificity (ensuring the articles are relevant). In order to facilitate complete, transparent and consistent reporting of the literature, attempts were made to consistently provide clear documentation of decision-making and rationale for each stage of this review. However, several limitations have to be considered when interpreting its results.

Most notably, due to limited resources, the literature search, screening, study eligibility, and data extraction were all conducted by a single reviewer. Whilst attempts were consistently made to preserve the integrity of the review, the lack of a secondary reviewer increased the potential for selection biases, random error, human error and implicit bias potentially influencing the reliability and validity of the review. Similarly, as searches were limited to studies published in English, it is likely that relevant articles published in other languages were excluded resulting in a potential language bias. Due to the scope of this review, unpublished research (“grey literature”) was not included and potentially resulted in the exclusion of relevant sources of evidence. Furthermore, neither a critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence, nor a risk of bias assessment were conducted.

Conclusion

With more than 175 million children per year expected to be affected by natural disasters (Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters, 2014) establishing the most effective evidence-based psychological intervention for children should be a global public health priority. This review demonstrates the high risk of persisting psychological impairment in young survivors of natural disasters and highlights the current gaps in existing literature regarding the development, research and implementation of psychological interventions. Whilst evidence supports the general efficacy of psychological interventions in this population, which specific elements of treatment constitute the necessary mechanisms of change remain largely speculative. Ultimately, we have a global responsibility to combine resources and develop effective, accessible, culturally appropriate and equitable psychological interventions to alleviate the psychological burden experienced by child victims of natural disasters.

The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition (The Universal Declaration of Human Right, Article 25.1, World Health Organization, 1948).

Data Availability

Access to Covidence Systematic Review software was provided by the University of Queensland.

References

Adler-Nevo, G., & Manassis, K. (2005). Psychosocial treatment of pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: The neglected field of single-incident trauma. Depression and Anxiety, 22(4), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20123

Adúriz, M. E., Bluthgen, C., & Knopfler, C. (2011). Helping child flood victims using group EMDR intervention in Argentina: Treatment outcome and gender differences. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 1(S), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1037/2157-3883.1.S.58

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-III). American Psychiatric Press.

Australian Psychological Society. (2018). Evidence-based psychological interventions in the treatment of mental disorders: A review of the literature. Australian Psychological Association.

Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council. (2020). Australian Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Acute Stress Disorder, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex PTSD; Children and Adolescents. https://www.phoenixaustralia.org/australian-guidelines-for-ptsd/

Berger, R., & Gelkopf, M. (2009). School-based intervention for the treatment of tsunami-related distress in children: A quasi-randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(6), 364–371. https://doi.org/10.1159/000235976

Bokszczanin, A. (2007). PTSD symptoms in children and adolescents 28 months after a flood: Age and gender differences. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(3), 347–351. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20220

Bonanno, G. A., Brewin, C. R., Kaniasty, K., & Greca, A. M. L. (2010). Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 11(1), 1–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100610387086

Brown, R., Witt, A., Fegert, J., Keller, F., Rassenhofer, M., & Plener, P. (2017). Psychosocial interventions for children and adolescents after man-made and natural disasters: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 47(11), 1893–1905. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717000496

Catani, C., Mahendran, K., Ruf, M., Schauer, E., Elbert, T., & Neuner, F. (2009). Treating children traumatized by war and Tsunami: A comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in North-East Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry, 9, Article 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-9-22

Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. (2014). The human cost of natural disasters, a global perspective. http://repo.floodalliance.net/jspui/bitstream/44111/1165/1/The%20Human%20Cost%20Of%20Natural%20Disasters%20A%20global%20perspective.pdf

Chemtob, C. M., Nakashima, J., & Carlson, J. G. (2002a). Brief treatment for elementary school children with disaster-related posttraumatic stress disorder: A field study. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(1), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.1131

Chemtob, C. M., Nakashima, J. P., & Hamada, R. S. (2002b). Psychosocial intervention for post-disaster trauma symptoms in elementary school children: A controlled community field study. Archives of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 156(3), 211–216. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.156.3.211

Chen, Y., Shen, W. W., Gao, K., Lam, C. S., Chang, W. C., & Deng, H. (2014). Effectiveness RCT of a CBT intervention for youths who lost parents in the Sichuan, China, earthquake. Psychiatric Services, 65(2), 259–262. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201200470

Cicero, S. D., Nooner, K., & Silva, R. (2011). Vulnerability and resilience in childhood trauma and PTSD. Post-Traumatic Syndromes in Childhood and Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470669280

Codreanu, T., Celenza, A., & Jacobs, I. (2014). Does disaster education of teenagers translate into better survival knowledge, knowledge of skills, and adaptive behavioral change? A systematic literature review. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 29(6), 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X14001083

Cohen, J. A., Bukstein, O., Walter, H., Benson, R. S., Chrisman, A., Farchione, T. R., Hamilton, J., Keable, H., Kinlan, J., Schoettle, U., Siegel, M., Stock, S. (2010). Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(4), 414–430. https://doi-org.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/10.1097/00004583-201004000-00021

Covidence Systematic Review Software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. www.covidence.org

Dorsey, S., McLaughlin, K. A., Kerns, S. E. U., Harrison, J. P., Lambert, H. K., Briggs, E. C., Revillion Cox, J., & Amaya-Jackson, L. (2017). Evidence base update for psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(3), 303–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2016.1220309

Eksi, A., & Braun, K. L. (2009). Over-time changes in PTSD and depression among children surviving the 1999 Istanbul earthquake. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 18(6), 384–391. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-009-0745-9

Fergusson, D. M., Horwood, L. J., Boden, J. M., & Mulder, R. T. (2014). Impact of a major disaster on the mental health of a well-studied cohort. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(9), 1025–1031. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.652

Fernandez, I. (2007). EMDR as treatment of post-traumatic reactions: A field study on child victims of an earthquake. Educational and Child Psychology, 24(1), 65–72.

Freeman, C., Nairn, K., & Gollop, M. (2015). Disaster impact and recovery: What children and young people can tell us. KōTuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 10(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2015.1066400

Giannopoulou, I., Dikaiakou, A., & Yule, W. (2006). Cognitive-behavioural group intervention for PTSD symptoms in children following the Athens 1999 earthquake: A pilot study. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 11(4), 543–553. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104506067876

Gillies, D., Taylor, F., Gray, C., O’Brien, L., & D’Abrew, N. (2013). Psychological therapies for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents (Review). Evidence-Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal, 8(3), 1004–1116. https://doi.org/10.1002/ebch.1916

Goenjian, A. K., Karayan, I., Pynoos, R. S., Minassian, D., Najarian, L. M., Steinberg, A. M., & Fairbanks, L. A. (1997). Outcome of psychotherapy among early adolescents after trauma. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(4), 536–542. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.154.4.536

Goenjian, A. K., Walling, D., Steinberg, A. M., Karayan, I., Najarian, L. M., & Pynoos, R. (2005). A prospective study of posttraumatic stress and depressive reactions among treated and untreated adolescents 5 years after a catastrophic disaster. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(12), 2302–2308. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2302

Grant, B. R., O’Loughlin, K., Holbrook, H. M., Althoff, R. R., Kearney, C., Perepletchikova, F., Grasso, D. J., Hudziak, J. J., & Kaufman, J. (2020). A multi-method and multi-informant approach to assessing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in children. International Review of Psychiatry, 32(3), 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2019.1697212

Haselgruber, A., Sölva, K., & Lueger-Schuster, B. (2020). Symptom structure of ICD-11 Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) in trauma-exposed foster children: Examining the International Trauma Questionnaire – Child and Adolescent Version (ITQ-CA). European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1818974. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1818974

Hawkins, S. S., & Radcliffe, J. (2005). Current measures of PTSD for children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 31(4), 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsj039

Hiller, R. M., Meiser-Stedman, R., Fearon, P., Lobo, S., McKinnon, A., Fraser, A., & Halligan, S. L. (2016). Research Review: Changes in the prevalence and symptom severity of child post-traumatic stress disorder in the year following trauma—a meta-analytic study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(8), 884–898. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12566

International Society of Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) Guidelines Committee. (2019). New ISTSS Prevention and Treatment Guidelines (2019). Retrieved from http://www.istss.org/treating-trauma/new-istss-prevention-and-treatment-guidelines.aspx

Jaycox, L. H., Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., Walker, D. W., Langley, A. K., Gegenheimer, K. L., Scott, M., & Schonlau, M. (2010). Children’s mental health care following Hurricane Katrina: A field trial of trauma-focused psychotherapies. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(2), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20518

Jones, R. T. (1996). Child’s reaction to traumatic events scale (CRTES): Assessing traumatic experiences in children. In Assessing psychological trauma & PTSD (pp. 291–298). American Psychological Association.