Abstract

Children’s responses to peer victimization are associated with whether the victimization continues, and its impact on adjustment. Yet little longitudinal research has examined the factors influencing children’s responses to peer victimization. In a sample of 140 late elementary school children (n = 140, Mean age = 10 years, 2 months, 55% female, 60% Caucasian), the role of social, emotional, and cognitive factors on children’s responses to peer victimization over time were examined. Broadly, children’s emotional reactivity and peer victimization experiences predicted changes in the ways participants thought about peer victimization over time, and children’s sense of control, attitudes toward the use of aggression, and problem solving predicted changes in participants’ coping responses over the course of the school year.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bullying involves repeated aggressive acts directed at targets who do nothing to instigate the attacks and are at disadvantages in the interactions (Olweus 1978, 2001). The targets of bullies are at risk for a host of adjustment difficulties (e.g., Kochenderfer and Ladd 1996; Kochenderfer-Ladd and Wardrop 2001; Olweus 1978; Roland 2002), but peer victimization does not affect all youth equally. Children’s responses to peer victimization are associated with whether the victimization continues (Kochenderfer and Ladd 1997; Smith et al. 2004) and its impact on adjustment (Kochenderfer-Ladd 2004; Kochenderfer-Ladd and Skinner 2002). Thus, many school-based interventions include components promoting what are thought to be positive responses (e.g., Orpinas and Horne 2006). Yet little longitudinal research has examined the factors influencing children’s responses to peer victimization. Drawing from transactional coping and social-information processing models, this study examined emotional, contextual, and cognitive factors hypothesized to predict changes in children’s responses to peer victimization over time.

Responding to Stress and Peer Victimization

Stressors include events appraised as taxing, dangerous, or exceeding one’s resources (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Stressors represent important risk factors for adjustment difficulties in youth (Cicchetti and Toth 1991, 1997; Haggerty et al. 1994; Mash and Barkley 1996), but stressors do not affect all youth equally. Some youth are better able to respond to stressors and minimize their negative impact. Children’s responses to stressors, however, depend on a myriad of factors specific to the individual, the situation, and the stressor (Compas et al. 1988, 2001; Eisenberg et al. 1997; Griffith et al. 2000; Lazarus 1999; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Reid et al. 1995). Thus, there is a need to determine the factors that influence children’s responses to specific stressors to guide intervention efforts.

Peer victimization is one of the more salient social stressors youth face, as peer victimization is both common and distressing, leading to loneliness, depressive symptoms, and in extreme cases suicidal ideation and acts (Kochenderfer and Ladd 1996; Kochenderfer-Ladd and Wardrop 2001; Nansel et al. 2001; Olweus 1978; Roland 2002). Children’s responses to victimization, however, influence both the duration of the victimization and its impact (Kochenderfer and Ladd 1997; Kochenderfer-Ladd and Skinner 2002; Smith et al. 2004). Thus, the factors that influence the ways youth respond to victimization are important targets for intervention efforts, particularly during late elementary school, as this is the period of development when peer victimization stabilizes with highly victimized youth maintaining their victim status year after year (e.g., Perry et al. 2001).

Consequently, many school-based interventions include components encouraging youth to seek the assistance of others and to avoid situations where victimization is likely to occur (i.e. avoidant actions). Interventions also discourage internalizing and externalizing responses to victimization, as these responses are thought to lead to increased victimization over time (e.g., DeRosier and Marcus 2005; Orpinas and Horne 2006). Whereas externalizing responses focus coping efforts on expressing anger or seeking revenge, internalizing responses focus coping efforts on managing or expressing distress related to worry, sadness, or guilt (Causey and Dubow 1992). Unfortunately, little longitudinal research has identified the factors that influence the ways in which children respond to victimization, and a better understanding of the factors that influence children’s responses to victimization can be used to guide intervention efforts designed to empower the targets of victimization to respond more effectively.

Factors Influencing Responses to Peer Victimization

Two of the more prominent models applied to understanding children’s behaviors in social situations, particularly stressful situations such as peer victimization and conflict, include transactional coping models and social information processing (SIP) models. Transactional models of coping assert that coping responses are heavily influenced by the appraisal of stressors (Lazarus 1999; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Broadly, the process of appraisal involves considering the implications of the current situation on one’s well being. When a situation is considered challenging, there is a greater sense of control in that situation, but when the situation is considered threatening, there is less of a sense of control (Lazarus 1999). When responding to peer victimization, higher appraised control (challenge appraisal) has been associated with more assertive and externalizing responses to victimization (Hunter et al. 2006), and ambiguity in the appraised threat and challenge of victimization experiences is linked to thinking more about the situation (i.e., problem solving) and support seeking (Hunter and Boyle 2004).

Though the terminology differs somewhat, SIP models also assert that appraisals of stressful social situations influence behaviors. SIP models, however, also assert that additional aspects of information processing play important roles in how people behave in social situations. Though the details of the various SIP models vary, the models broadly assert that biases in the social cues to which children attend, in the interpretation of what these cues mean, and in the consideration of potential responses all increase the risk of problematic behaviors (Crick and Dodge 1994; Huesmann 1998). For instance, the less time children spend problem solving, as evidenced by the number of cues they encode (Dodge et al. 2003; Dodge and Newman 1981) and the less time spent considering potential responses (Shure and Spivack 1980), the more likely youth are to engage in aggressive responses to peer conflict.

It is also particularly important to examine the cognitive factors highlighted by transactional coping and SIP models during middle childhood and early adolescence, as attitudes toward the use of aggression, tendency to attribute hostile intent to the actions of peers, and the acceptability of goals accepting retaliation are rapidly developing during this time (e.g., Aber et al. 1996; Rogers and Tisak 1996). Children’s cognitive abilities are also developing, allowing children the capabilities to consider more information and generate more responses to stressors involving social conflict. Thus, late, middle childhood and early adolescence is likely a time when children’s cognitions regarding their responses to social conflict are particularly malleable to social-cognitive interventions (Thornton et al. 2002).

Both transactional models of coping and SIP models also assert that people’s individual characteristics (e.g., sex, prior experiences with similar stressors, emotional reactivity, attitudes) and contextual factors (e.g., prior experiences with peer victimization and the availability of social support) play important roles in children’s responses to stressors. Regarding an individual’s characteristics, emotional arousal is closely intertwined with coping efforts as most stressors are emotionally distressing (Eisenberg et al. 1997; Skinner and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007), and emotional reactions to stressors are thought to influence both the speed at which people form appraisals (Lazarus 1999), and when severe, short circuiting the processing of social information (Crick and Dodge 1994). The negative emotions resulting from peer victimization have been directly linked to children’s responses to victimization (Bollmer et al. 2006; Champion and Clay 2007; Hunter and Borg 2006; Hunter et al. 2006; Kochenderfer-Ladd 2004). Fear, for example, is linked with more support seeking and engagement in fewer externalizing responses (Hunter et al. 2006; Kochenderfer-Ladd 2004). More consistent with SIP models, emotional arousal is thought to influence behaviors by disrupting SIP, leading youth to process fewer social cues and consider fewer potential responses in stressful social interactions (Lemerise and Arsenio 2000). Emotions such as fear might also reduce children’s sense of control and influence their attitudes by making them less supporting of using aggressive behaviors. Thus, it is necessary to consider emotions and cognitions when examining the factors that influence children’s coping responses. In the one cross-sectional study to examine the roles of both appraisal and negative emotions, challenge appraisals and negative emotion increased the likelihood of seeking help (Hunter et al. 2004).

Cross-sectional research also suggests a history of peer victimization decreases children’s sense of control and increases attitudes accepting of the use of aggression (Dill et al. 2004; Vernberg et al. 1999; Hunter and Boyle 2002). Whereas appraised control relates to children’s responses to victimization (Hunter et al. 2006), aggression supporting attitudes also probably increase the likelihood of externalizing responses and decrease the likelihood of internalizing, avoidance, and support seeking. Extant longitudinal research, however, has focused on the impact of emotions, social experiences, or cognitions without considering the joint role of these factors (e.g., Kochenderfer-Ladd 2004).

Additionally, the social context in which peer victimization occurs influences children’s responses to victimization, the frequency of the victimization, and the consequences of the victimization. Peer rejection and having no friends, for instance, increase the risk of victimization over time, and having just one non-victimized friend minimizes the influence of other risk factors for victimization such as, small physical size in males (see Perry et al. 2001; Smith et al. 2001 for review). Social support also likely exerts direct influences on children’s responses to peer victimization by increasing the likelihood of seeking the assistance of others because the support is available, and it might influence the ways children think about responding to victimization by increasing children’s appraised control when responding to victimization and providing more responses to consider. Although peers have been shown to influence children’s antisocial and prosocial behaviors more generally (e.g., Barry, and Wentzel 2006; Snyder 2003), the author is unaware of any research examining how the availability of peer support influences children’s responses to peer victimization more specifically.

Previous research supports the assertion that gender is an important factor to consider when examining children’s responses to victimization. Whereas, females tend to engage in more internalizing and support seeking, males engage in more externalizing responses (e.g., Causey and Dubow 1992; Olafsen and Viemerö 2000; Salmivalli et al. 1996). Male and female children also evidence different SIP patterns, aggressive attitudes, and their sense of control (Crick 1995; Crick et al. 2002; Delveaux and Daniels 2000; Hunter and Boyle 2002; Perry et al. 1989). For instance, females are more likely to view support seeking as a positive response to victimization (Hunter et al. 2004; Newman et al. 2001) and less likely to endorse the goal of retaliation (Champion and Clay 2007). Males and females also tend to have different emotional reactions to victimization, with female youth tending to experience more self-pity following victimization and less severe emotional reactions in moderately distressing instances of peer victimization, than do males (e.g., Borg 1998; Champion and Clay 2007). Because of these gender differences gender must also be considered when examining influences on children’s responses to victimization.

Though transactional coping and SIP models do not preclude an individual’s characteristics and contextual factors from directly influencing his or her responses to stressors, these models assert cognitive factors are more proximal to behaving and responding in social situations than an individual’s characteristics and contextual factors (e.g., Crick and Dodge 1994; Huesmann 1998; Lemerise and Arsenio 2000). Thus, cognitions such as appraised control and on-line information processing should add to the prediction of children’s coping responses, even when controlling for sex and fear reactivity and contextual factors such as previous peer victimization experiences and the availability of peer support.

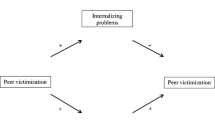

The aim of the current study was to examine factors theorized by transactional coping and SIP models to influence children’s responses to peer victimization over time with the goal of informing intervention efforts. The study advances past research by examining how cognitive, emotional, and contextual factors relate to children’s responses to peer victimization in a multi-informant, longitudinal study. Though previous research has examined how cognitive, emotional, and contextual factors relate to coping response, much of this research was cross-sectional and failed to consider the joint influence of factors from all of these domains. Longitudinal research is needed to determine how these factors influence changes in children’s coping responses over time. Broadly, it was hypothesized that children’s sex, cognitions, emotions, and peer interactions would relate to how they responded to peer victimization at the beginning of the school year. Additionally, children’s sex, fear reactivity, peer victimization experiences, and the availability of peer support at the beginning of the school year are expected to influence changes in cognitions (i.e., appraised control, aggression supporting beliefs, and problem solving) over the course of the school year. Given the prominence of cognitions in transactional coping and SIP models, aggression supporting attitudes, appraised control, and problem solving efforts are expected to add to the prediction of participants’ responses to victimization over time, even when controlling for sex, fear reactivity, prior victimization experiences, peer support and participants’ initial coping tendencies.

Methods

Participants

The sample was composed of 5th and 6th grade students from a school serving a lower income (i.e., nearly 50% of students receive free or reduced lunches due to low family income; Louisiana Department of Education 2005), rural area in the southeastern United States (eligible population = 206). At Time 1, data were obtained from 154 students and their teachers (75% of eligible population), and 140 of these participants at Time 2. These 140 participants (55% female, 45% male; Mean age = 10 years, 2 months) comprise the analysis sample for the project. Attrition analyses revealed no differences between the analysis and attrition samples. The analysis sample is predominantly Caucasian (60%), with 17% self-identifying as African American, 17% as multiple ethnicities, and 6% as Hispanic/Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, or Native American, which is representative of the population from which it was drawn.

Procedures

The project consisted of two data collection waves: Time 1 at the beginning of the school year and Time 2 at the end of the school year. Parental consent was obtained for student participants before the start of the study, and teacher consent was obtained for teachers willing to participate (i.e., 9 out of 10 teachers). Student assent was collected prior to the questionnaire administration at each data collection time point. At Time 1, students reported on their fear reactivity, aggressive supporting attitudes, their sense of control, problem solving efforts, peer victimization experiences, peer support, and responses to peer victimization. Homeroom teachers also reported on their students’ peer victimization experiences, because these teachers spent the majority of the school day with their students. At Time 2, students again reported on their aggressive supporting attitudes, appraised control, problem solving, sense of control, and responses to peer victimization. The questionnaires were read aloud to groups of approximately 25 participants, taking approximately 45 minutes to complete at each assessment. To limit the impact of group administration on responding, a small font size was used and participants were spaced far enough apart to make it difficult to read others’ responses. Participants also utilized cover sheets while completing their surveys. All procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the university overseeing the research.

Measures

Peer Victimization

To adequately sample the broad range of victimization experiences youth face, 10 self-report items measuring victimization were selected from a variety of victimization measures including the Social Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ: Crick and Bigbee 1998; Crick and Grotpeter 1996; Paquette and Underwood 1999), the Olweus Bullying Questionnaire (Olweus 2001), and the victimization version of the Direct and Indirect Aggression Scales (DIAS; Osterman et al. 1994). These are all widely used measures of peer victimization that have demonstrated adequate reliability (e.g., α < .80) and validity (e.g., correlating with related variables such as lower peer support) with samples similar to the youth participating in the current investigation (Bijttebier and Vertommen 1998; Crick and Bigbee 1998; Crick and Grotpeter 1996; Cullerton-Sen and Crick 2005; Osterman et al. 1994; Phelps 2001). In order to measure how often participants were the targets of victimization and not just friendly teasing, a definition of bullying was presented prior to completing the victimization items. The definition explained that bullying involves repeated aggressive acts where the target is at a disadvantage that makes it difficult for the target to defend him or herself (Olweus 2001). A short list of bullying examples including direct, indirect, verbal, nonverbal and physical forms of bullying was then provided. The stem, “How often do classmates bully you by…” preceded each item.

Of the ten items selected, three items tapped physical victimization (e.g., being hit, pushed, kicked); two items tapped social or relational forms of victimization (i.e., being left out and the target of mean facial expressions); three items measured verbal victimization (i.e., called mean names and threatened physical harm or social exclusion), and two items measured indirect verbal victimization (i.e., being the target of lies or mean stories). Participants responded to each item on a Likert scale, ranging from 0 = “Never” to 4 = “Always.” Given the victimization items were selected from a series of established measures, a principal component analysis was conducted, and it supported the inclusion of these items in a single scale, with all items loading on a single factor (eigenvalue = 5.349; factor loading above .60). Because recent research also supports conceptualizing victimization by overall severity, rather than by specific types of victimization, in late childhood and adolescence (Nylund et al. 2007), victimization scores were calculated by taking the mean of scores on all ten items, similar to established procedures (Boxer et al. 2003; Kochenderfer-Ladd 2004). The internal reliability of the scale was high, α = .90.

Teachers also completed six items indicating the frequency at which participating students were the targets of physical, social/relational, and verbal forms of victimization. Prior to completing the scale, teachers were presented with the same definition of bullying and each item was preceded by a stem inquiring, “How often classmates bully the student by…” Teachers responded to each item on a Likert scale, ranging from 0 = “Never” to 4 = “Always.” Given the scale was created for the current investigation, a principal component analysis was conducted on the items, and all items loaded on a single factor (eigenvalue = 4.78; all loadings above .60). Internal reliability was also high, α = .90. The scale score was created by calculating the mean of the items composing the scale.

To create a general indicator of peer victimization, the means of the self-report and teacher-report victimization scales were standardized (z-scores), and the standardized means were then summed. Informants’ scores were combined because the use of multiple informants provides a more complete, reliable, and valid assessment (Kamphaus and Frick 2002; Morris et al. 2005). This is particularly true when the pattern of associations between reports by different informants and other variables are consistent, which was the case in the current study. Additionally, participants scoring higher on both reports likely experience more extreme victimization than participants rated highly by only one informant. The internal reliability estimate for the combined scale was also high, α = .86. The distributions for the composite victimization scales at Times 1 and 2 were positively skewed. A log transformation resulted in a better approximation of normality (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001).

Responses to Peer Victimization

As indicators of participants’ behavioral responses to peer victimization, youth completed selected subscales from the Self-Report Coping Measure (SRCM; Causey and Dubow 1992) and the How I Coped Under Pressure Scales (HICUPS; Program for Prevention Research [PPR] 1999) at Times 1 and 2. Both are widely used measures of children’s coping responses to specific stressors that have demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in samples similar to the current sample (Andreou 2001; Bijttebier and Vertommen 1998; Causey and Dubow 1992; Phelps 2001; PPR 1999). Internal reliability estimates for the SRCM subscales have ranged between α = .68–.84, and the scales were significantly correlated with peer reports of coping efforts (Causey and Dubow 1992). In order to measure participants’ responses to peer victimization, items were preceded with the stem, “When bullied.” Participants responded to each item on a Likert scale ranging from 0 = “Never” to 4 = “Always.”

Student participants completed items from the support seeking, externalizing, and internalizing subscales of the SRCM. For the current investigation, participants completed six items from the support seeking subscale, and these six items were divided into two subscales: seeking peer support and seeking adult support. The seeking peer support subscale included three items (α = .70 at Time 1 and α = .79 at Time 2) measuring how often youth responded to peer victimization by seeking help, assistance, or advice from their peers. The seeking adult support subscale included three items indicating how often they sought the support of adult family members and teachers (α = .78 at Time 1 and α = .73 at Time 2). The four item externalizing coping subscale of the SRCM measured how often youth responded by venting negative emotions such as getting mad and throwing or hitting things. One item was added to the externalizing subscale measuring how often youth “fight back” when bullied (α = .70 at Time 1 and α = .67 at Time 2). The internalized coping subscale (7 items; α = .80 at Time 1 and α = .83 at Time 2) measured participants’ efforts to manage the distress resulting from victimization (e.g., becoming so upset that one cannot talk to anyone or crying).

A modified version of the avoidant actions subscale from the HICUPS (PPR 1999) was also utilized (6 items; α = .73 at Time 1 and α = .85 at Time 2). The subscale measured how often youth tried to stay away from situations in which they were likely to be the target of peer victimization, and was modified by adding two items asking how often participants avoided individuals contributing to the stressor (e.g., the bullies). Due to the revisions made to the original scale, a principal component analysis was conducted and indicated that all items loaded on a single factor at both Times 1 (eigenvalue = 2.422) and 2 (eigenvalue = 3.165) with all factor loadings above .50. Coping response subscales scores were created by calculating the mean of each participant’s responses on the items composing the subscales.

After creating scores for each coping response subscale, proportion scores were calculated by dividing the mean of each subscale score by the sum of all coping subscales. This procedure is done with other coping measures (Connor-Smith et al. 2000), and it addresses two major limitations with using raw coping scores. First, this controls for base rate differences in overall responding, as youth experiencing more frequent victimization have more opportunities to respond (Phelps 2001). Second, the use of proportioned coping scores acknowledges that youth respond to peer victimization in multiple ways, providing a better estimate of participants’ responding styles while also considering the tendency to use other responses (Newman et al. 2001).

Fear Reactivity

At Time 1, student participants completed the fear subscale of the Early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire short form (EATQ: Capaldi and Rothbart 1992; Ellis and Rothbart 2001; Spinrad et al. 2006). The EATQ is a widely used measure tapping temperament and regulatory abilities of young adolescents, which has demonstrated internal reliability estimates of α = .64–.68 (Capaldi and Rothbart 1992; Terranova et al. 2008). The fear subscale consists of six items measuring unpleasant affect related to the anticipation of distress in dangerous or emotionally arousing situations. Items include being scared of getting into trouble and when entering a dark room. The fear scale demonstrated adequate internal reliability in the current study, α = .68. All items have a Likert response format, ranging from 0 = “Almost Always Untrue” to 4 = “Almost Always True.”

Legitimacy of Aggression

At both Times 1 and 2, student participants completed five items measuring their attitudes toward the legitimacy of using aggression in peer interactions. On a Likert response format (i.e., 0 = “Never” and 4 = “Always”), items asked participants to rate how often they felt it was funny when others were called names; how often the targets of bullies deserved to be picked on; and how often it is okay to fight, make fun of others, and cheer when others are fighting. These items were selected from an established measure of children’s and early adolescents’ attitudes toward aggression (Vernberg et al. 1999). The original scale demonstrated adequate internal reliability (α = .88) and was related in expected directions with aggressive behaviors (Vernberg et al. 1999). Given only selected items were used in the current study, a principal component analysis was conducted and revealed that all items loaded on a single factor at both Times 1 and 2, with an eigenvalue of 2.409 at Time 1 and 2.618 at Time 2. All items loaded above .30 at Time 1, with all but one loading above .60, and at Time 2 all loadings were above .60. Internal reliability estimates for the subscale were α = .71 at Time 1 and α = .77 at Time 2, with a test–retest reliability of r = .50, p < .001 for the subscale.

Sense of Control

As has been done in prior research (e.g., Hunter and Boyle 2002, 2004; Hunter et al. 2006), a single item was used to tap student participants’ sense of control when responding to peer victimization at both Times 1 and 2 (i.e., “When bullied, how often do you think there are things you can do to make the situation better?”) Participants responded to the item using a Likert response format, ranging from 0 = “Never” to 4 = “Always.”

Problem Solving

At Times 1 and 2, student participants completed three items adapted for the current study from the problem solving subscale of the SRCM (α = .84, Causey and Dubow 1992). The items were adapted by adding the stem, “When bullied,” to each item and having participants respond to items on a Likert response format, ranging from 0 = “Never” to 4 = “Always.” The selected items focused on aspects of SIP (i.e., interpretation of cues, generation of potential responses, and evaluation of these responses) relevant to the ways youth respond in social interactions (Crick and Dodge 1994). The items incorporated in the subscale created for the current study included items inquiring how often participants tried to understand why this happened to me, tried to think of different ways to solve the situation, and going over in your mind all the things they could say or do. Given that only selected items were utilized from an established scale, a principal component analysis was conducted and indicated the items formed a single factor, with eigenvalues of 1.633 and 1.698 at Times 1 and 2, respectively. Each item had factor loadings of .69 or above, with internal reliability estimates of α = .58 at Time 1 and α = .62 at Time 2, and a test–retest correlation of r = .36, p < .001.

Peer Support

As an indicator of the social support participants receive from their peers, student participants completed the five item receipt of prosocial behaviors subscale of the Social Experiences Questionnaire (Crick and Bigbee 1998; Crick and Grotpeter 1996) at Times 1 and 2. Using a five option Likert scale (0 = “Never” to 4 = “Always”), the receipt of prosocial behaviors subscale measures how often participants’ peers do nice things for them, try to cheer them up when they are sad, and generally provide assistance when they are in trouble. The receipt of prosocial behaviors subscale has been widely used in populations similar to the current sample, with internal reliability estimates ranging from α = .77 to .90 and receipt of prosocial behaviors being negative related to peer victimization (e.g., Crick and Bigbee 1998; Crick and Grotpeter 1996). Internal reliability estimates were also high, α = .83 at Times 1 and 2, in the current study.

Results

Factors Associated with Responses to Victimization at Time 1

T-tests were conducted to examine sex differences in coping responses at the beginning of the school year. As expected, males engaged in more externalizing responses than females (t = 3.23, p < .01), with externalizing responses accounting for 21% of males response as compared to only 12% of females responses. Unexpectedly however, no other sex differences in coping responses emerged. Table 1 lists the correlations among study variables at Time 1. Although participants’ tendencies to seek support from peers and adults were significantly correlated (r = .24, p < .01), the size of this correlation was not large, and seeking support from peers and from adults were differentially related to peer support. Youth who experienced less victimization were more likely to avoid situations where bullying might occur and to seek assistance from adults. Youth who experienced more victimization were more likely to engage in externalizing and internalizing responses. As hypothesized, social, emotional, and cognitive factors were generally related to coping responses, but no single factor related to all forms of coping.

Predicting Changes in Cognitions Over Time

To examine if social, emotional, and cognitive factors at the beginning of the school year predict changes in participants’ cognitions over the course of the school year, three hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted. One regression was conducted to predict participants’ Time 2 appraised control, a second to predict participants’ attitudes regarding the legitimacy of aggression, and a third to predict participants’ problem solving efforts. In step 1 of each regression, participant sex, Time 1 appraised control, Time 1 attitudes regarding the legitimacy of aggression, and Time 1 problem solving were entered into the regression as predictors. In Step 2 of the regressions, fear reactivity, victimization,Footnote 1 and peer support were entered into each regression as predictors. As hypothesized, peer victimization at the beginning of the school year predicted less appraised control over the course of the school year (see Table 2). When controlling for aggressive attitudes at the beginning of the school year, victimization increased participants’ sense that it is legitimate to use aggression when interacting with peers, but greater fear predicted a decreasing sense that aggressive behaviors are legitimate. Unexpectedly, when controlling for participants’ initial problem solving tendencies, none of the factors included in the current study predicted changes in participants’ problem solving efforts over time.

Predicting Changes in Responses to Victimization Over Time

To determine if peer support and participants’ cognitions predicted participants coping responses at the end of the school year, when controlling for participants’ sex, initial response tendencies, fear reactivity, and previous peer victimization experiences, a final series of hierarchical regression analyses was conducted. For each of these regressions, one type of coping (i.e., seeking peer support, seeking adult support, externalizing, internalizing, or avoidant actions) at the end of the school year was the criterion. In Step 1, participants’ sex, initial tendency to engage in this specific type of coping response, Time 1 fear reactivity, and Time 1 peer victimization experiences were entered into each equation. In Step 2, participants’ Time 2 peer support, attitudes, sense of control, and problem solving efforts were entered into the regression as predictors. The results of these regressions are summarized in Table 3.

Across all five regressions, participants’ sex failed to predict the ways youth responded to peer victimization, and participants’ response tendencies at the beginning of the school year predicted their response tendencies at the end of the school year. Whereas as sense of control and the availability of peer support increased the likelihood of seeking assistance from peers, these variables did predict seeking assistance from adults. In fact, only participants’ initial tendency to seek assistance from adults predicted their continued tendency to seek support from adults. Attitudes supporting the legitimacy of aggression predicted increasing use of externalizing responses. Somewhat unexpected however, a lower sense of control and higher levels of peer support predicted greater externalizing responses to peer victimization over time. Participants with higher levels of fear reactivity, who tended to receive less support from their peers, and tended to think more about potential responses were more likely to engage in internalizing responses over time. Lower levels of peer support also increased the likelihood of more internalizing responses over time. The only factor adding to the prediction of avoidant action responses was problem solving, with youth engaging in more problem solving being more likely to avoid situations where victimization was likely to occur.

Discussion

The longitudinal associations between cognitive, emotional, and social factors with children’s responses to peer victimization were examined in the current study with the goal of better informing intervention efforts designed to empower youth to respond more effectively to peer victimization. As predicted, children’s emotions and social experiences at the beginning of the school year were related to children’s cognitions over the course of the school year. Consistent with transactional coping and SIP models (e.g., Crick and Dodge 1994; Huesmann 1998; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Lemerise and Arsenio 2000), attitudes regarding the legitimacy of aggression, a sense of control, problem solving efforts, and peer support at the end of the school year predicted coping responses at the end of the school year, even when controlling for initial response tendencies, fear reactivity, and previous victimization experiences suggesting these cognitions and promoting social support are important issues for interventions to address.

Predicting Changes in Cognitions Over Time

Based on transactional coping and SIP models (e.g., Crick and Dodge 1994; Huesmann 1998; Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Lemerise and Arsenio 2000), it was hypothesized that children’s cognitions, emotions, and social experiences at the beginning of the school year would influence changes in their sense of control, attitudes toward aggression, and problem solving efforts. Some support for this hypothesis was obtained, with children’s fear reactivity predicting less accepting attitudes supporting the use of aggression over time. A history of frequent peer victimization also predicted a lowering sense of control when responding to victimization and more supportive attitudes toward the legitimacy of aggression over time. This replicates past cross-sectional findings that greater victimization is related to a lower sense of control (Hunter and Boyle 2002), and extends these findings in two ways. First, the longitudinal design allows for the consideration of children’s initial sense of control while examining the impact of peer victimization on this sense of control over time. Second, the current study suggests that a history of victimization also impacts other cognitive factors that likely influence children’s responses to victimization experiences (i.e., attitudes toward aggression). Unexpectedly, none of the variables included in the current study predicted changes in problem solving efforts over time.

Predicting Coping Responses Over Time

Overall, findings suggest that children’s tendencies to respond to peer victimization at the beginning of the school year predicted the ways they responded at the end of the school year. Once children’s initial response tendencies were controlled, sex, fear, and prior victimization experiences generally failed to predict coping responses over time. When considered with the cross-sectional findings from past research (e.g., Causey and Dubow 1992; Hunter et al. 2006) this suggests that although these factors likely influence the development of coping styles earlier in development, they are no longer influencing changes in coping behaviors. There was one notable exception, however. Fear reactivity predicted an increased likelihood that youth would engage in internalizing responses (i.e., crying and getting upset) over time.

It was also notable that availability of peer support predicted an increase in seeking peer support over time, but not seeking support from adults. This finding speaks to the importance of distinguishing from whom children seek support when examining factors that promote support seeking. It also extends previous cross-sectional findings which indicated emotional reactions and the frequency of victimization differentially predicted from whom youth sought help (Hunter and Borg 2006). Given support seeking is one of the few coping responses consistently found to reduce victimization (Kochenderfer and Ladd 1997; Smith et al. 2004), this finding suggests that one way to promote support seeking is to establish a peer support network. This is consistent with research findings that social support building interventions are associated with reductions in victimization (e.g., Cunningham et al. 1998; Naylor and Cowie 1999).

Consistent with expectations, cognitive factors generally predicted changes in children’s coping responses over the course of the school year, even when controlling for their initial response tendencies. The finding that aggression supporting beliefs predict externalizing responses is not surprising given that many of these externalizing responses involve aggressive behaviors (i.e., fighting back, yelling, hitting, etc.), and the link between aggression supporting attitudes and aggressive behaviors has been consistently demonstrated (e.g., Vernberg et al. 1999; Mushner-Eizenman et al. 2004).

The findings that a greater sense of control increased the likelihood of support seeking responses and decreased the likelihood of externalizing responses, however, are inconsistent with past findings (e.g., Hunter et al. 2006; Newman et al. 2001). This is likely due to methodological differences across studies. In the current study, participants were asked if they felt there were things they could do to deal with the bullying, and one of the these responses might have been seeking help. In other studies, perceptions of physical abilities (Newman et al. 2001) and the ease with which one can stop people from being mean (Hunter et al. 2007) were used as indicators of control. Beyond these methodological differences, it might be that other factors interact with children’s sense of control, leading some youth with a strong sense of control to respond aggressively while others avoid aggressive and externalizing responses. For instance, when a sense of control is combined with confidence in one’s physical abilities or anger, this might increase the likelihood of externalizing responses.

Alternatively, children who engage in more problem solving tended to respond with more internalizing responses and more often tried to avoid situations where they were likely to experience victimization over the course of the school year. The links between problem solving and both internalizing responses and avoidant actions might be due to rumination and worry, as intrusive thoughts about being the target of victimization likely force youth to think more about why they are being attacked by peers; how they can potentially respond; and avoiding victimization in the future. These intrusive thoughts and worry also likely influences the content of problem solving efforts, which is important as the quality of problem solving efforts becomes a more important influence on behaviors, than the amount of problem solving, as children development (Shure and Spivack 1980). Thus, future studies should consider rumination, attributions, and the content of problem solving efforts.

Limitations, Strengths, and Implications

Though the current study has several strengths and incrementally advances previous findings, there are limitations that must be considered when interpreting the findings. Given the narrow developmental range of the sample, the findings might not generalize to youth outside of this developmental range. Additionally, some of the measures used in the current study evidenced lower than expected estimates of internal reliability. Thus, future studies should seek to replicate the current findings in more diverse samples and using measures more adequately measuring the constructs of interest. Though there was an attrition rate of approximately 10%, the analysis sample did not differ substantially from participants who withdrew from the study. A single item was used to measure children’s sense of control when responding to victimization. Although single item measures of control are commonly used and have demonstrated adequate reliability and validity (e.g., Hunter and Boyle 2002, 2004; Hunter et al. 2006), a scale including multiple items likely would have more comprehensively measured participants’ sense of control.

Even with these limitations, the study has important strengths, such as the longitudinal design, the use of multiple informants, and the consideration of the joint influences of cognitive, emotional, and social factors on coping responses. When considering factors from these multiple domains, the current findings suggest that social and emotional factors predict changes in children’s cognitions over time. These cognitions then predict changes in children’s responses to victimization, which is consistent with transactional coping and SIP models of behavior.

The current findings have important implications for intervention efforts designed to empower youth to respond more effectively to peer victimization. The findings suggest interventions should target children’s attitudes toward aggression, their sense of control, and problem solving efforts when seeking to change the ways youth respond to peer victimization. Reducing children’s acceptance of aggressive behaviors as legitimate will likely reduce their use of externalizing responses, which tend to be associated with continued victimization over time (Hanish et al. 2004; Kochenderfer and Ladd 1997; Kochenderfer-Ladd 2004). Although the current findings indicate increasing appraised control would also likely increase the tendency to seek assistance from others and reduce externalizing responses, this finding has not been consistent across studies. Thus, interventions should be careful to address the potential for these negative responses when building a sense of control in children. The findings also suggest that simply encouraging youth to think more about how to respond to peer victimization might not lead to better responses, as the amount of time problem solving predicted increases in internalizing responses over time. Instead, interventions should help youth develop more constructive problem solving patterns.

Though cognitive factors directly related to the ways youth responded to victimization both concurrently and across time, the current findings suggest that interventions should consider the impact of social and emotional factors on the ways youth think about peer victimization and aggression. Continued victimization, for example, will likely undermine efforts to change the way youth think about responding and attempts to increase a sense of control in children. Additionally, children’s fear reactivity was linked to more internalizing responses over time. This is alarming, as internalizing responses are thought to lead to continued or worsening victimization over time (Perry et al. 1989; Schwartz et al. 1993). Thus, the current findings suggest that efforts to empower children to more effectively respond to peer victimization should be included into more comprehensive intervention efforts.

Notes

These analyses were also conducted using self-reports of victimization and teacher-reports of victimization separately, and the same pattern of findings were found. Thus, in the interests of brevity and clarity, the results using the combined-informant indicator of peer victimization are presented.

References

Aber, J. L., Brown, J. L., Chaundry, N., Jones, S. M., & Samples, F. (1996). The evaluation of the resolving conflict creatively program: An overview. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 12, 82–90.

Andreou, E. (2001). Bully/victim problems and their association with coping behaviour in conflictual peer interactions among school age children. Educational Psychology, 21, 59–66.

Barry, C. M., & Wentzel, K. R. (2006). Friend influence on prosocial behavior: The role of motivational factors and friendship characteristics. Developmental Psychology, 42, 153–163.

Bijttebier, P., & Vertommen, H. (1998). Coping with peer arguments in school-age children with bully/victim problems. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 68, 387–394.

Bollmer, J. M., Harris, M. J., & Milich, R. (2006). Reactions to bullying and peer victimization: Narratives, physiological arousal, and personality. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 803–828.

Borg, M. G. (1998). The emotional reactions of school bullies and their victims. Educational Psychology, 18, 433–444.

Boxer, P., Edwards-Leeper, L., Goldstein, S. E., Musher-Eizenman, D., & Dubow, E. F. (2003). Exposure to “low level” aggression in school: Associations with aggressive behavior, future expectations, and perceived safety. Violence and Victims, 18, 691–705.

Capaldi, D. M., & Rothbart, M. K. (1992). Development and validation of an early adolescent temperament measure. Journal of Early Adolescence, 12, 153–173.

Causey, D. L., & Dubow, E. F. (1992). Development of a self-report coping measure for elementary school children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 21, 47–59.

Champion, K. M., & Clay, D. L. (2007). Individual differences in responses to provocation and frequent victimization by peers. Child Psychology and Human Development, 37, 205–220.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (1991). A developmental perspectives on internalizing and externalizing disorders. In D. Cicchetti & S. L. Toth (Eds.), Internalizing and externalizing expressions of dysfunction (pp. 1–19). New York, NY: Erlbaum.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. L. (1997). Transactional ecological systems in developmental psychopathology. In S. S. Luthar, J. Burack, D. Cicchetti, & J. Weisz (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Perspectives on adjustment, risk, and disorder (pp. 314–349). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 87–127.

Compas, B. E., Malcarne, V. L., & Fondacaro, K. M. (1988). Coping with stressful events in older children and young adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 405–411.

Connor-Smith, J. K., Compas, B. E., Wadsworth, M. E., Thomsen, A. H., & Saltzman, H. (2000). Coping as a mediator of relations between reactivity to interpersonal stress, health status, and internalizing problems. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28, 347–368.

Crick, N. R. (1995). Relational aggression: The role of intent attributions, feelings of distress, and provocation type. Development and Psychopathology, 7, 313–322.

Crick, N. R., & Bigbee, M. A. (1998). Relational and overt forms of peer victimization: A multi-informant approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 337–347.

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 74–101.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1996). Children’s treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 367–380.

Crick, N. R., Grotpeter, J. K., & Bigbee, M. A. (2002). Relationally and physically aggressive children’s intent attributions and feelings of distress for relational and instrumental provocation. Child Development, 73, 1134–1142.

Cullerton-Sen, C., & Crick, N. R. (2005). Understanding the effects of physical and relational victimization: The utility of multiple perspectives in predicting social-emotional adjustment. School Psychology Review, 34, 147–160.

Cunningham, C., Cunningham, L., Martorelli, V., Tran, A., Young, J., & Zacharias, R. (1998). The effects of primary division, student mediated conflict resolution programs on playground aggression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 39, 653–662.

Delveaux, K. D., & Daniels, T. (2000). Children’s social cognitions: Physically and relationally aggressive strategies and children’s goals in peer conflict situations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 46, 672–692.

DeRosier, M. E., & Marcus, S. R. (2005). Building friendships and combating bullying: Effectiveness of S. S. GRIN at One-Year Follow-up. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 140–150.

Dill, E. J., Vernberg, E. M., Fonagy, P., Twemlow, S. W., & Gamm, B. K. (2004). Negative affect in victimized children: The roles of social withdrawal, peer rejection, and attitudes toward bullying. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 159–173.

Dodge, K. A., Lansford, J. E., Burks, V. S., Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., Fontaine, R., et al. (2003). Peer rejection and social information processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Development, 74, 374–393.

Dodge, K. A., & Newman, J. P. (1981). Biased decision making processes in aggressive boys. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 90, 375–379.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Guthrie, I. (1997). Coping with stress: The roles of emotion regulation and development. In J. N. Sandler & S. A. Wolchik (Eds.), Handbook of children’s coping with common stressors” linking theory, research, and intervention (pp. 41–70). New York: Plenum.

Ellis, L. K., & Rothbart, M. K. (2001). Revision of the early Adolescent Temperament Questionnaire. Poster presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society of Research Child Development, Minneapolis, MN.

Griffith, M. A., Dubow, E. F., & Ippolito, M. F. (2000). Developmental and cross-situational differences in adolescents’ coping strategies. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 183–204.

Haggerty, R. J., Sherrod, L. R., Garmezy, N., & Rutter, M. (Eds.). (1994). Stress, risk, and resilience in children and adolescence: Processes, mechanisms, and interventions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hanish, L. D., Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Spinrad, T. L., Ryan, P., & Schmidt, S. (2004). The expression and regulation of negative emotions: Risk factors for young children’s peer victimization. Development and Psychopathology, 16, 335–353.

Huesmann, L. R. (1998). The role of social information processing and cognitive schema in the acquisition and maintenance of habitual aggressive behavior. In R. G. Geen & E. Donnerstein (Eds.), Human aggression: Theories, research, and implications for social policy (pp. 73–109). New York: Academic Press.

Hunter, S. C., & Borg, M. G. (2006). The influence of emotional reaction on help seeking by victims of school bullying. Educational Psychology, 26, 813–826.

Hunter, S. C., & Boyle, J. M. E. (2002). Perceptions of control in the victims of school bullying: The importance of early intervention. Educational Research, 44, 323–336.

Hunter, S. C., & Boyle, J. M. E. (2004). Appraisal and coping strategy use in victims of school bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 83–107.

Hunter, S. C., Boyle, J. M. E., & Warden, D. (2004). Help seeking amongst child and adolescent victims of peer-aggression and bullying: The influence of school-stage, gender, victimization, appraisal, and emotion. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 375–390.

Hunter, S. C., Boyle, J. M. E., & Warden, D. (2006). Emotions and coping in young victims of peer aggression. In P. Buchwald (Ed.), Stress and anxiety: Applications to health, community, work place, and education. United Kingdom: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Hunter, S. C., Boyle, J. M. E., & Warden, D. (2007). Perceptions and correlates of peer-victimization and bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 797–810.

Kamphaus, R. W., & Frick, P. J. (2002). Clinical assessment of child and adolescent personality and behavior (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Kochenderfer, B., & Ladd, G. W. (1996). Peer victimization: Cause or consequence of school maladjustment? Child Development, 67, 1305–1317.

Kochenderfer, B. J., & Ladd, G. W. (1997). Victimized children’s responses to peers’ aggression: Behaviors associated with reduced versus continued victimization. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 59–73.

Kochenderfer-Ladd, B. (2004). Peer victimization: The role of emotions in adaptive and maladaptive coping. Social Development, 13, 329–349.

Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., & Skinner, K. (2002). Children’s coping strategies: Moderators of the effects of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 38, 267–278.

Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., & Wardrop, J. L. (2001). Chronic and instability of children’s peer and victimization experiences as predictors of loneliness and social satisfaction trajectories. Child Development, 72, 134–151.

Lazarus, R. S. (1999). Stress and emotion: A new synthesis. New York: Springer.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer.

Lemerise, E. A., & Arsenio, W. F. (2000). An integrated model of emotion processes and cognition in social information processing. Child Development, 71, 107–118.

Louisiana Department of Education. (2005). Subgroup counts, indices and performance scores for Fall 2005. Retrieved November 12, 2006, from the Division of Standards, Assessment, and Accountability website: http://www.doe.state.la.us/lde/pair/2228.asp.

Mash, E. J., & Barkley, R. A. (1996). Child psychopathology. New York: Guilford Press.

Morris, A. S., Robinson, L. R., & Eisenberg, N. (2005). Applying a multimethod perspective to the study of developmental psychology. In M. Eid & E. Diener (Eds.), Handbook of multimethod measurement in psychology (pp. 371–384). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Mushner-Eizenman, D. R., Boxer, P., Danner, S., Dubow, E. F., Goldstein, S. E., & Heretick, D. M. L. (2004). Social-cognitive mediators of the relation of environmental and emotion regulation factors to children’s aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 30, 389–408.

Nansel, T. R., Overpeck, M., Pilla, R. S., Ruan, W. J., Simons-Morton, B., & Scheidt, P. (2001). Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. Journal of the American Medical Association, 285, 2094–2100.

Naylor, P., & Cowie, H. (1999). The effectiveness of peer support systems in challenging school bullying: The perspectives and experiences of teachers and pupils. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 467–479.

Newman, R. S., Murray, B., & Lussier, C. (2001). Confrontation with aggressive peers at school: Students’ reluctance to seek help from the teacher. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 398–410.

Nylund, K., Bellmore, A., Nishina, A., & Graham, S. (2007). Subtypes, severity, and structural stability of peer victimization: What does latent class analysis say? Child Development, 78, 1706–1722.

Olafsen, R. N., & Viemerö, V. (2000). Bully/victim problems and coping with stress in school among 10- to 12-year-old pupils in Aland, Finland. Aggressive Behavior, 26, 57–65.

Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the schools: Bullies and whipping boys. New York, NY: Wiley.

Olweus, D. (2001). Administration manual for the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire for students. (Available from Dan Olweus Vognstelbakken 16, N-5096 Bergen, Norway).

Orpinas, P., & Horne, A. M. (2006). Bullying prevention: Creating a positive school climate and developing social competence. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Osterman, K., Bjorkqvist, K., Lagerspetz, K. M. J., Kaukiainen, A., Heusmann, L. R., & Fraczek, A. (1994). Peer and self-estimated aggression and victimization in 8-year-old children from five ethnic groups. Aggressive Behavior, 20, 411–428.

Paquette, J. A., & Underwood, M. K. (1999). Gender differences in young adolescents’ experiences if peer victimization: Social and physical aggression. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 45, 242–266.

Perry, D. G., Hodges, E. V. E., & Egan, S. K. (2001). Determinants of chronic victimization by peers: A review and new model of family influence. In J. Juvonen & S. Grahm (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 73–104). New York: Guilford.

Perry, D. G., Perry, L. C., & Weiss, R. J. (1989). Sex differences in the consequences that children anticipate for aggression. Developmental Psychology, 25, 312–319.

Phelps, C. E. R. (2001). Children’s responses to overt and relational aggression. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 240–252.

Program for the Prevention Research. (1999). Manual for the children’s coping strategies checklist and the how I coped under pressure scale. (Available from Arizona State University, P.O. Box 876005, Tempe, AZ 85287-6005).

Reid, G. J., Dubow, E. F., & Carey, T. C. (1995). Developmental and situational differences in coping among children and adolescents with diabetes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16, 529–554.

Rogers, M. J., & Tisak, M. S. (1996). Children’s reasoning about responses to peer aggression: Victim’s and witness’s expected and prescribed behaviors. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 259–269.

Roland, E. (2002). Aggression, depression, and bullying others. Aggressive Behavior, 28, 198–206.

Salmivalli, C., Karhunen, J., & Lagerspetz, K. M. J. (1996). How do the victims respond to bullying? Aggressive Behavior, 22, 99–109.

Schwartz, D., Dodge, K. A., & Coie, J. D. (1993). The emergence of chronic victimization in boys’ play groups. Child Development, 64, 1755–1772.

Shure, M. B., & Spivack, G. (1980). Interpersonal problem-solving as a mediator of behavioral adjustment in preschool and kindergarten children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 1, 29–44.

Skinner, E. A., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 119–144.

Smith, P. K., Shu, S., & Madsen, K. (2001). Characteristics of victims of school bullying: Developmental changes in coping strategies and skills. In J. Juvonen & S. Grahm (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 332–352). New York: Guilford.

Smith, P. K., Talamelli, L., Cowie, H., Naylor, P., & Chauhan, P. (2004). Profiles of non-victims, escaped victims, continuing victims, and new victims of school bullying. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 565–581.

Snyder, J. (2003). Reinforcement and coercion mechanisms in the development of antisocial behavior: Peer relationships. In J. B. Reid, G. R. Patterson, & J. Snyder (Eds.), Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention (pp. 101–122). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Spinrad, T. L., Eisenberg, N., Cumberland, A., Fabes, R. A., Valiente, C., Shepard, S. A., et al. (2006). Relation of emotion-related regulation to children’s social competence: A longitudinal study. Emotion, 6, 498–510.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Computer-assisted research design and analysis. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Terranova, A. M., Morris, A. S., & Boxer, P. (2008). Fear reactivity and effortful control in overt and relational bullying: A six-month longitudinal study. Aggressive Behavior, 34, 104–115.

Thornton, T. N., Craft, C. A., Dahlberg, L. L., Lynch, B. S., & Baer, K. (2002). Best practices in youth violence prevention: A sourcebook for community action (Rev). Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vernberg, E. M., Jacobs, A. K., & Hershberger, S. L. (1999). Peer victimization and attitudes about violence during early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 28, 386–395.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Terranova, A.M. Factors that Influence Children’s Responses to Peer Victimization. Child Youth Care Forum 38, 253–271 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-009-9082-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-009-9082-x