Abstract

Promoting prosocial behavior among adolescents protects them against problematic outcomes and ensures their positive development. This study aimed to examine (1) the association between adolescents’ representation of acceptance-rejection from multiple attachment figures (father, mother, best friend, and teacher) and prosocial behavior toward multiple targets (stranger, friends, and family) and (2) the mediating role of sense of authenticity in these relationships. The sample comprised 784 adolescents (56% boys), aged 12–15 years (M = 13.98 years, SD = .83). Data were collected online by a research company using six self-report measures. The structural equation model suggested that paternal acceptance-rejection was significantly directly associated with prosocial acts toward three targets and maternal acceptance-rejection was indirectly associated with prosocial acts toward a stranger. Moreover, best friend and teacher acceptance-rejection was related to prosocial acts toward family and friends, and friends respectively. Sense of authenticity mediated the association between maternal and best friend acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior toward strangers. The findings reveal that the benefits of providing acceptance or love in a relationship are reciprocal and offer personal benefits and increased welfare of others.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Promoting prosocial behavior among youth is an important goal for parents, educators, societies, and nations. In recent times, prosocial behavior, often defined as a voluntary act aimed at benefiting another, has gained increased attention among researchers (Eisenberg et al., 2006). Emerging literature argues that prosocial behavior protects individuals against a myriad of adverse outcomes including aggression (Eisenberg et al., 2006), substance abuse (Carlo et al., 2014), and internalizing problems (Flouri & Sarmadi, 2016). Moreover, it is also associated with positive youth development including academic success (DeVries et al., 2018), higher self-regulation (Memmott-Elison et al., 2020), higher self-esteem (Fu et al., 2017), and sympathy (Carlo et al., 2015).

The Multidimensional Nature of Prosocial Behavior

Although the construct of prosocial behavior has previously been considered as unidimensional, recent research emphasizes the multidimensional features of prosocial acts (Padilla-Walker & Carlo, 2014). For example, the multidimensional nature is highlighted depending on (a) types of prosocial behavior (Dunfield, 2014), (b) intentions to help others (Carlo et al., 2010), and (c) the target towards whom the act is intended (Padilla-Walker & Carlo, 2014; Padilla-Walker et al., 2015a). The present investigation is focused on Padilla-Walker et al., (2015a) research, which delineated the recipient-oriented multidimensional nature of prosocial behavior. They highlighted the multidimensionality of prosocial behavior depending on the closeness of the relationship with the recipient (e.g., family, friends, and strangers). To illustrate, a previous study showed that adolescents demonstrated a higher frequency of prosocial actions toward close friends than toward strangers and family members that may denote prosocial act is not uniformly performed toward different recipients (Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011). Prosocial behavior was previously considered as unidimensional because the majority of previous studies were predominantly focused on children, rather than adolescents (Padilla-Walker & Carlo, 2014). However, as adolescents have enhanced cognitive abilities that enable engagement in abstract reasoning, they have an increased understanding of self and morals; thus, they are more likely to take responsibility and engage in benevolent acts differently, both at home as well as in the external context, compared to children. Despite the importance given to studying adolescents’ prosocial behaviors and its antecedents, few studies have explored the predictors of adolescents’ prosocial behavior, mostly focusing on parental factors. However, relationships with non-parental attachment figures (friend, teacher) were also found to be potential predictors of youth’s benevolent actions (Eisenberg et al., 2015). Furthermore, findings about these predictors have focused on either parental or non-parental predictors of adolescents’ general prosocial behavior, while overlooking the perspective of those who were recipients of this behavior. Thus, the recipient’s perspective contributes to a cohesive understanding of the nature of prosocial behavior in adolescence. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate, simultaneously, the role of acceptance-rejection from multiple attachment figures (parental and non-parental) on adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward strangers, friends, and family.

To our knowledge, evidence on the differential role of parental and non-parental factors on different target-oriented prosocial behaviors of adolescents is not only inconclusive but also based on findings from Western countries. However, socialization practices, interpersonal relationships, and prosocial behaviors are found to be greatly influenced by culture (Brittian & Humphries, 2015; Eisenberg et al., 2015). Japan is characterized by traditional child-rearing values and parenting practices that develop a sense of interdependency, harmony, and prosocial behavior in children. Moreover, Japanese society features distinctive child development processes compared to those of Western countries (Hosokawa & Katsura, 2019). The present study is exclusively focused on Japanese adolescents to provide cross-cultural evidence as well as a comprehensive understanding of the target-oriented prosocial behaviors of adolescents. These findings will contribute to the development of interventions for adolescents, enabling them to achieve optimal psychological functioning and social competence.

Predictors of Prosocial Behavior

In exploring the predictors of benevolent acts toward multiple targets, relational and dispositional approaches have been applied to explain individuals’ actions (Eisenberg et al., 2006; Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011; Padilla-Walker et al., 2016, 2018). Furthermore, both approaches can be considered concurrently to effectively explain prosocial behavior variations while considering the recipient’s perspective.

Interpersonal Acceptance-Rejection and Prosocial Behavior: A Relational Approach

The relational approach explains prosocial behavior by considering the relationship between the benefactor and recipient (Lewis, 2014; Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011; Padilla-Walker, et al., 2015b). This approach recognizes that adolescents are more likely to support somebody they know or with whom they are in a relationship with (i.e., friends, family) than an unknown person (Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011). Previous studies (Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011; Padilla-Walker et al., 2016) showed that positive relationships with attachment figures encouraged prosocial behavior as individuals want to maintain these relationships. Thus, positive relationships (i.e., warmth, acceptance) with significant others not only promote prosocial behavior to maintain or improve the relationship between recipient and benefactor, but also play a role in increasing individuals’ inner motivation and potentialities to perceive the external environment positively and act benevolently (Rohner, 2019).

This study is based on the interpersonal acceptance-rejection theory (IPARTheory), an evidence-based theory that explains the antecedents, correlates, and consequences of interpersonal acceptance-rejection throughout the lifespan (Rohner, 2019; Rohner & Lansford, 2017). This theory asserts that interpersonal relationships with attachment figures (mother, father, friend, and teacher) are attributed to an emotional tie of positive responses that lies someplace along the warmth/love continuum (Rohner, 2019). One end of this continuum is marked by the interpersonal acceptance (i.e., experienced by the presence of care, appreciation, support, nurturance, or simply love) and the other end is marked by the interpersonal rejection (i.e., experienced by the absence of the above-mentioned feelings and acts along with a verity of physically and mentally painful behaviors and negative feelings [Rohner, 2019]). According to IPARTheory, individuals experience neither acceptance nor rejection in any absolute sense. Instead, they experience more or less love by their attachment figures (Rohner, 2019). Previous studies in different populations and cultures have empirically supported the finding that perceived acceptance-rejection from attachment figures is not only related to individuals’ psychological adjustment and mental well-being, but also promoted social competence and prosocial behavior (Putnick et al., 2018; Rohner, 2019).

Investigation on how maternal and paternal acceptance-rejection uniquely influence prosocial acts toward a distinct recipient is still in the nascent stage. However, past literature highlighted the significant influence of parents on the enactment of prosocial behavior by children (Eisenberg et al., 2015) and adolescents, but focused mostly on mother–child relations (Luengo Kanacri et al., 2020; Padilla-Walker et al., 2015a, 2015b). Therefore, the role of fathers on their children’s prosocial development remains relatively unexplored. IPARTheory posits that acceptance-rejection from both parents is an important foundation for children’s adjustment and subsequent development (Rohner, 2019). To illustrate, a longitudinal study based on this theory asserted that parental acceptance-rejection (in terms of warmth/affection, hostility/aggression, neglect/indifference, and undifferentiated rejection) was associated with children’s later general prosocial behavior (Putnick et al., 2018). Through displays of warm, sensitive, and nurturing parenting, parents modeled prosocial behavior for their children, which were subsequently internalized and expressed by children toward family members and others (Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011; Padilla-Walker et al., 2018). This further illustrates that parent–child relationships are cyclical, particularly in adolescence, when parent–child regular dealings become more egalitarian and mutual; if parents are supportive and warm in their responses to requests from children, similar cooperative (i.e., prosocial) responses and affection towards parents would be expressed by children (Eisenberg et al., 2015; Padilla-Walker et al., 2016).

Recent investigations showed that parents sometimes exhibit influential roles in adolescents’ display of prosocial behavior toward other targets (strangers & friends) (Padilla-Walker et al., 2016, 2018). For example, maternal warmth and connectedness significantly influenced prosocial behaviors toward strangers, whereas paternal warmth determined prosocial behavior toward friends (Padilla-Walker et al., 2018). Further, Padilla-Walker et al. (2016) showed that paternal (not maternal) hostility was negatively linked to adolescents’ benevolent acts toward family, friends, and strangers. However, further studies are warranted to test the consistency of these differential findings for mothers and fathers.

When children reach the adolescent developmental stage, friends and peers become unique socializers and act as salient predictors of adolescents’ psychological and behavioral outcomes. In other words, being loved, liked, and supported by their best friend offers a sense of relatedness that satisfies their need for a positive response (i.e., acceptance) (Rohner, 2019), which most likely encourages prosocial behavior (Padilla-Walker et al., 2018). Laible (2007) claimed that peer attachment played a unique role in adolescents’ helpfulness behavior, even after controlling for the effect of parental attachment. Furthermore, the relational approach suggests that connectedness with friends reinforces helpfulness behaviors toward friends (Padilla-Walker et al., 2015b, 2018). Indeed, helpfulness behavior demonstrated toward friends is often a marker of faithfulness, concern, and mutual obligation between friends to maintain the relationship (Padilla-Walker et al., 2015b). However, there is a lack of studies on the relationship between attachment with best friends and prosocial enactment, considering multiple recipients of helpfulness behavior.

It is not surprising that the relationships of children with teachers play a crucial role in children’s social conduct (Eisenberg et al., 2015; Rohner, 2010). IPARTheory posits that children’s perceptions of the acceptance-rejection behaviors from teachers affect their adjustment and behavior similar to their perceived parental acceptance-rejection (Rohner, 2010, 2019). A growing number of researches demonstrated a positive association between teachers’ warmth and children’s prosocial behavior (Hendrickx et al., 2017; Luckner & Pianta, 2011). Furthermore, it was found that conflicted teacher-student relationships were associated with decreased prosocial behavior (Hendrickx et al., 2017). Therefore, positive relationships with teachers influence the development of helpfulness behavior; however, the majority of previous investigations have been conducted in early childhood settings (Eisenberg et al., 2015); thus, further studies are needed to examine the association between teacher acceptance-rejection and adolescents’ prosocial outcomes considering different targets.

Dispositional Approach: Sense of Authenticity as a Mediator

In exploring the motivators of prosocial behavior, the dispositional approach suggests that some kind of prosocial act is primarily a function of individual factors (e.g., how one sees and understands himself/herself) (Eisenberg et al., 2006, 2015; Fu et al., 2017) rather than the direct influence of a social circle. IPARTheory’s personality sub-theory predicts that perceived acceptance-rejection from significant others plays a prominent role in determining personality dispositions (such as self-acceptance, self-esteem, and self-adequacy) (Rohner, 2019; Rohner & Lansford, 2017). Previous studies support the notion that self-awareness, self-regulation, and self-esteem of an individual are important motivators of helpfulness behavior and act as mediators between relational factors and prosocial acts (Eisenberg et al., 2006; Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011; Padilla-Walker et al., 2015a, 2015b). It is likely that same socialization practices and relationships with significant others may foster dispositional traits (i.e., self-esteem, and self-regulation) that in turn can foster a certain type of prosocial behavior (Eisenberg et al., 2006; Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011).

During adolescence, emotional and cognitive maturation in self-understanding allows an increased understanding of one’s own true self (i.e., sense of authenticity) (Ito & Kodama, 2005; Thomaes et al., 2017), thus facilitating the search for authenticity (Thomaes et al., 2017). In this study, the sense of authenticity was considered as a mediator between interpersonal acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior in adolescents, as it is assumed that satisfaction of positive responses from attachment figures (i.e., perceived acceptance) facilitates the development of authenticity (Thomaes et al., 2017) and prosocial behavior among adolescents (Putnick et al., 2018). This is because, as assumed by Eisenberg et al. (2006), individuals who feel self-adequate about themselves might be able to give attention to others’ needs and desires because their own needs are being met and they are truly satisfied with themselves. Moreover, Plasencia (2014) experimentally showed that increased authenticity about self is related to an increase in prosocial behaviors among adults. To our knowledge, no such empirical evidence is available that shows how adolescents’ sense of authenticity is associated with prosocial behaviors.

Notably, in this study, Ito and Kodama’s (2005) sense of authenticity scale was used. Influenced by the Harter’s (2002) concept of authenticity and Kernis’s (2003) theoretical conceptualization of optimal self-esteem, Ito and Kodama (2005) delineated the subjective aspect of authenticity as sense of authenticity—one’s sense of being true to oneself. Researchers have claimed that individuals with more subjective authenticity tend to consider both their own and others’ needs while engaging in pro-relationships (Baker et al., 2017); however, research examining how sense of authenticity benefits relationship functioning with others is limited. Zhang et al. (2019) emphasized that subjective authenticity is the persuasive core of individuals’ morals and helpfulness behavior. Moreover, Fabes et al. (1999) considered prosocial behavior as an important form of moral behavior. A positive association between subjective authenticity and helpfulness behavior in the workplace is evident in a previous study (e.g., Zhang et al., 2019).

Sense of authenticity is regarded as the foundational aspect of optimal self-esteem that is characterized by the qualities associated with secure, stable, genuine, and true self-esteem (Kernis, 2003; Kernis & Goldman, 2006). Previous studies showed a significant association between self-esteem and helpfulness behavior in adolescents (Fu et al., 2017). Moreover, Leary and MacDonald (2003) claimed that self-esteem was a cause of prosocial behavior rather than vice versa. Fu et al. (2017) found that self-esteem was significantly associated with prosocial behavior toward strangers but not toward friends and family. The present study was interest in determining the relationship between sense of authenticity and prosocial behavior toward different targets. Prosocial behaviors toward strangers do not have direct reciprocal benefits, as is the case with prosocial behavior toward friends and family. Thus, it is assumed that sense of authenticity provides individuals with a depth of inner resources to act spontaneously according to internal true states while not being motivated by extrinsic benefits (e.g., appreciations) or purposes (e.g., intentions for improvement of existing interpersonal relationships). However, how this mechanism works for target-specific prosocial acts was not empirically evident in the literature, and this study aimed to address such issue.

The Cultural Context in Japan

Japanese society is characterized by high homogeneity and low diversity in terms of race and ethnicity as well as a combination of “old world traditions” and “modern industrialization” (Kabuto, 2021). Cultural variation has not been incorporated because of limits on offers of citizenship for foreign residents and the narrowing the gap between the rich and poor in educational plans (Gordon, 2016; Sugimura, 2020). From a cross-cultural research perspective, researchers are interested in studying Japanese society because it can be compared to Western countries in terms of its industrialization, affluent economy, education, and employment. However, it clings to traditional values and socialization practices, which are distinct from Western cultures (Hosokawa & Katsura, 2019; Yamada, 2004). To illustrate, amae-based symbiotic harmony [dependency on another’s benevolence and mutual trust in each other; originally described (by Doi (1971))] in interpersonal relationships characterizes harmonious Japanese culture, including parent–child relationship (Azuma, 1986; Behrens, 2004; Doi, 1971). Japanese culture and family system prioritize cooperation, mutual trust, and support (Nisbett, 2003; Oyseman et al., 2002), which facilitate the development and nurturance of prosocial behavior among children.

It is important to note that the Confucian ideology has greatly influenced Japanese society by emphasizing the development of morality and social skills among the youth. Parents with Confucian ideals are more likely to believe that children need to nurture morals and helpfulness qualities, which will safeguard them against the corrupting impact of modern civilization (Holloway & Nagase, 2014). Additionally, Japanese parents also encourage their children to be persistent, kind, empathetic, obedient, and polite (Holloway, 2010; Holloway & Nagase, 2014). To develop social skills, Japanese parents utilize unique strategies for socializing their children. For example, parents tend to avoid direct conflict with children; instead, they draw their children’s attention to the consequences of misconduct and often stimulate the sense of empathy by referring to the affective outcomes of conduct on another person (Holloway & Nagase, 2014). Further, individualistic and collectivistic values coexist in the socialization of Japanese children. To develop autonomy and self-reliance, Japanese mothers encourage their children to formulate their own choices and opinions (Yamada, 2004). These actions may facilitate the development of sense of authenticity among Japanese children. However, the influence of Japanese fathers on adolescents’ outcomes is rarely examined empirically.

Japanese families maintain different views of parental roles and ideologies compared with families from Western cultures. Traditionally, both parents’ equal participation in family issues was considered unnecessary in Japanese society (Kelsky, 2001). In addition, Japanese children and adolescents were emotionally closer to their mothers than to their fathers, compared to American children (Huang et al., 1996). However, the Japanese family system is undergoing significant transitions in recent times (Kabuto, 2021). Previously, Japanese fathers were hard-working breadwinners, while being legal, moral, and social authority figures, whereas Japanese mothers were expected to be the primary caregivers (Yasumoto, 2010). Moreover, fathers were less involved in child rearing activities and maintained a superior position in the hierarchy among other family members (Uji et al., 2014). In current times, Japanese mothers and fathers are redefining their roles and responsibilities. Uji et al. (2014) reported that fathers are no longer assuming the traditional role of the detached disciplinarian; they are now perceived as more permissive and less authoritarian. As women are now participating in the labor force, they are making decisions about marriage and childbearing. Researchers argue that ideologies within Japanese families are changing due to globalization, acceptance of modern western ideas, reformation of governmental policies, and gender roles (Takahashi, 2013). These changes could possibly influence socialization practices within Japanese families, while affecting children’s social and psychological development.

In Japan, schools are important sites for the development of educational and social skills in adolescents. Education is compulsory from elementary until junior high school. The education system in Japan is mainly teacher-centered (Fukuzawa, 1994) and adolescents spend long durations in school during this period (Ministry of Health, Labour, & Welfare of Japan, 2009). Therefore, their emotional and psychological functioning mostly depends on their relationship with teachers and peers (Aktar et al., 2020; Mizuta, 2017). Due to the lack of time, Japanese adolescents tend to develop friendships with students from their school or class. They are expected to study hard, develop friendships, and help others in school (i.e., getting along with peers in class) (Hatano et al., 2019). Thus, Japanese society features distinct interpersonal relationships at home and in school, transitions in the family system and in parental roles, women’s economic empowerment through participation in the labor force, and paternal involvement in family issues; this study is uniquely focused on adolescents in Japan who might be affected by these issues.

The Current Study

This study is the first in Japan to investigate whether adolescents’ target-oriented prosocial behaviors are differentially influenced by perceived acceptance-rejection from multiple attachment figures (parental & non-parental) and dispositional correlates (sense of authenticity).

The current study had two main aims to provide an integrative understanding of the role of different parental and non- parental associates on target-oriented prosocial behavior. First, this study is the first to have investigated the simultaneous association between perceived acceptance-rejection (derived from IPARTheory) from multiple attachment figures (mother, father, best friend, & teacher) and prosocial behavior toward family, friends, and strangers. As mentioned earlier, existing studies between parent–child relations and prosocial behaviors were mostly focused on the mother–child relationship. Therefore, following Padilla-Walker et al.’s (2018) recommendation for further studies on the role of father-child relations, this study aimed to add incremental findings related to paternal acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior toward targets. Thus, by assessing the effects of both maternal and paternal acceptance-rejection simultaneously, it would be possible to identify whether parental acceptance-rejection had a differential role on target oriented prosocial acts of adolescents. This study also might provide a clear demonstration of how perceived best friend and teacher acceptance-rejection is related to adolescents’ prosocial enactment toward friends, family, and strangers. Second, whether sense of authenticity mediated the relationships between acceptance-rejection from attachment figures (mother, father, best friend, and teacher) and prosocial acts toward multiple targets were further investigated. To investigate the direct effect of acceptance-rejection from parents, best friends, and teachers as well as the indirect effect of perceived acceptance-rejection (from aforementioned attachment figures) through sense of authenticity (i.e., mediating effect of sense of authenticity) on prosocial acts toward multiple targets, a structural equation model was tested. In this study, interpersonal acceptance-rejection was considered as existing on a continuum, according to the IPARTheory, rather than as a separate dimension.

Firstly, based on the relational approach (Eisenberg et al., 2006; Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011) and existing literature (e.g., Padilla-Walker et al., 2016, 2018) of prosocial behavior, we expected that paternal and maternal acceptance-rejection would be negatively and directly associated with prosocial behavior toward family. It is also important to mention that few recent studies demonstrated that parent–child relationships promoted prosocial behavior toward other targets (see Padilla-Walker et al., 2018) as well. Therefore, we considered the possibility of testing the direct paths from parents to friends and strangers based on the suggestions of the correlational analyses. Secondly, we expected that perceived best friend acceptance would be positively and directly associated with helpfulness behavior toward friends (see Padilla-Walker, et al., 2015b). Further, since this study is the first to investigate the relationship between teacher acceptance-rejection and target-oriented prosocial behavior, there was no prior expectation about the relationship between these two variables. Additionally, we considered the possibility of testing the direct paths from best friend acceptance to strangers and family as well as the direct paths from teacher to all three targets of prosocial behavior based on suggestions from the correlational analyses. Based on the postulates of personality sub-theory of IPARTheory (Rohner & Lansford, 2017), we expected that perceived interpersonal acceptance-rejection (mother, father, best friend, and teacher) would be related to sense of authenticity, and that sense of authenticity in adolescents, in turn, (based on the dispositional approach of prosocial behavior [Eisenberg et al., 2006, 2015; Leary & MacDonald, 2003] and based on past studies [Fu et al., 2017]) would be related to prosocial behavior toward strangers. In other words, sense of authenticity would mediate the relationship between interpersonal acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior toward strangers. As this study is the first to examine the mediating role of sense of authenticity in the relationship between interpersonal acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior, we also intended to explore whether these pathways co-existed for helpfulness behavior toward friends and family.

Specifically, for investigation, the following three major hypotheses are highlighted from the above demonstration.

-

1.

Perceived paternal and maternal acceptance-rejection would be negatively and directly associated with prosocial behavior toward family.

-

2.

Perceived best friend acceptance would be positively and directly associated with helpfulness behavior toward friends.

-

3.

Sense of authenticity would mediate the relationship between interpersonal (mother, father, best friend, and teacher) acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior toward strangers.

Since this is the first study to investigate the effects of interpersonal acceptance-rejection from multiple attachment figures and sense of authenticity on adolescents’ target- oriented prosocial acts in Japan, incrementally other paths (as mentioned above) would be tested, based on the findings of correlational analyses.

Method

Participants

Data were collected across Japan using an online research company and obtained data from 841 Japanese adolescents who responded correctly to the three random attention check items (see the procedure for details). Fifty seven participants were excluded (46 participants withdrew consent, 11 participants responded in untrustworthy ways, i.e., they selected the same response option both in positively and negatively stated items). The final sample comprised 784 adolescents (56% boys, 44% girls), aged 12–15 years (Mage = 13.98 years, SD = 0.83). Their educational level varied from first to third grade in junior high school. Adolescents who lived with both biological parents in intact families were included in the study. About 40%, 21%, and 16% of the participants lived in the Kanto (eastern Japan), Kansai (west-central Japan), and Chubu (central Japan) metropolitan regions, respectively. The remaining 23% participants lived in the Hokkaido, Tohuku, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Kyushu regions that were, compared to the aforementioned areas, rural areas. The socio-economic background information of participants was not collected since it is not a custom in Japan to collect such background information from adolescents (Sugimura et al., 2009). However, the registrants (parents of target participants; see procedure for details) had to provided information regarding the educational level and annual family income while opening an account with a research company. According to the research company, the registrants’ education level and annual family income were approximately normally distributed. For example, about 2.46% and 6.26% of parents had junior high school level and graduate level education, respectively; however, the majority (45.84% and 45.44%) of parents had high school level education, and undergraduate level education, respectively. Similarly, with regard to registrants’ annual household income, 3.72% of parents’ household income was less than JPY 2 million, about 11.92% of parents’ income was between 2 million JPY and less than 4 million JPY, and about 22.31% of parents’ income was between 4 million JPY and less than 6 million JPY. Further, 20.55% of parents’ income was between 6 million JPY and less than 8 million JPY, 14.08% of parents’ income was between 8 million JPY and less than 10 million JPY, 9.94% of parents’ income was between 10 million JPY and less than 16 million JPY, and only 1.62% of parents’ income was 16 million JPY or more. Furthermore, about 15.85% parents’ income level was unknown. The average annual income of a Japanese household is approximately 5.52 million JPY (Ministry of Health, Labour, & Welfare of Japan, 2019). Therefore, the highest proportion of registrants belonged to average-income families.

Procedure

Prior to the commencement of data collection, ethical approval was granted from the authors’ affiliated graduate school. Data were collected online employing a major online research company in Japan (NTT Com Online Marketing Solutions Co. Ltd: (https://www.nttcoms.com/), which generally works with government agencies, and academic institutions (e.g., Igarashi, 2019). This company strictly maintains confidentiality of data including personal information according to Japanese law and their company policies. It uses encrypted communication to secure the distribution of data to customers and to protect personal information of respondents. In addition, it has acquired a “privacy mark” from the Japan Institution for Promotion of Digital Economy and Society (JIPDEC) for ensuring confidentiality and protecting the personal information of respondents.

For the present study, an order (by payment) for online data collection was placed with the company following the ethical standards of the authors’ affiliated graduate school and the policies of the research company. The data were used only for this study. The company was requested to provide data of at least 700 adolescents who had passed the three attention check items (“Please skip this item and move on”, “To show that you are reading this sentence carefully, please select the option almost never true”, “If you are reading the sentence carefully, please select the option rarely true”) to assure integrity of data. These items were embedded within the blocks of main items of the survey questionnaires. Identifiable personal information was not requested by the research company.

As minors were not permitted to be registrants of the research company, the survey targets were the adolescent’s (aged 12–15 years or junior high school students) parents who were registrants of the research company (they are called company monitors). Initially, the company advertised the link of the survey online for parents. Before starting the survey, they received an explanatory note detailing the confidentiality processes of the study. Parents were informed that the data would be strictly confidential and only used for scientific analyses; moreover, information would be combined during analyses, without identifying a specific individual. Furthermore, they were informed that the data file would be stored in a password protected memory device, which was only used for this study. It would be strictly stored in a locked box in a secure place and data would be abandoned after the period specified by the research company’s policies and the ethical standards of the authors’ affiliated graduate school. After presenting the explanatory notes to the parents, a detailed consent form was presented on the webpage, where they could provide informed consent for their children’s participation. After providing consent, parents received a link to the online survey and were requested to forward it to their children. Later, the children who accessed the link before recruitment received information about the study along with the ethical details. Only participants who provided consent participated in the study. Finally, participants were thanked for their participation. Moreover, the research company added 40 reward points, which was equivalent to JPY 40 (approximately USD 0.40) to the registrant’s research company account. These points were exchangeable for money (through bank transfer) or an electronic gift card (e.g., amazon gift card).

Measures

Participants answered to the six self-reported questionnaires ([1 and 2] the Japanese Shortened Version of the Child Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire for mothers and fathers, respectively [Child PARQ-J-SF: Mother and Father], [3] the Japanese Shortened Version of the Teacher Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire [Child TARQ-J-SF], [4] the Best Friend Acceptance Scale [BEFAS], [5] the Sense of Authenticity Scale [SOAS], and [6] the Prosocial Behavior Scale [PBS]) along with a personal information form that elicited demographic information (e.g., age, sex, and grade in school).

Japanese Shortened Version of the Child Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire for Mother and Father (Child PARQ-J-SF: Mother and Father)

The shortened Japanese version of the Child PARQ-J-SF (Aktar et al., 2021), which was constructed from Child PARQ, short-form (Rohner, 2005a) of the IPARTheory was used to measure children’s current feelings about maternal and paternal acceptance-rejection behavior. Both the parent versions were applied and each consisted of 18 items. The two versions were alike, except that one assessed children’s perception of their mother’s behavior toward them while the other assessed children’s representation about their father’s behavior toward them. Both tools were subdivided into four subscales: (1) hostility/aggression (e.g., My mother [father] says many unkind things to me) (four items), (2) indifference/neglect (e.g., My mother [father] is too busy to answer my questions) (four items), (3) undifferentiated rejection (e.g., My mother [father] seems to dislike me) (four items), and (4) warmth/ affection (e.g., My mother [father] makes me feel wanted and needed) (six items). The warmth/ affection scale was reverse scored to indicate coldness as proposed by Rohner, 2005a. Items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale with responses ranging from (1) almost never true to (4) almost always true. The sum of the four subscales constituted a measure of global perceived maternal and paternal acceptance-rejection. The Japanese shortened version of Child PARQ for both mothers and fathers had satisfactory reliability (Cronbach’s alpha for both the mother and father versions was .93), adequate construct validity (as IPARTheory proposed four-factor structure with adequate factor loadings [.72–.93], model fit in mother version: WLSMV χ2(129) = 502.50, p < .001; comparative fit index [CFI] = .976; the standard root mean square with residual [SRMR] indices = .035; the root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .069, 90% confidence interval [CI] [.063–.076]), and a four-factor structure with adequate factor loadings [.69–.95]. The scale also demonstrated model fit in father version: WLSMVχ2(129) = 552.46, p < .001; CFI = .977; SRMR = .039; RMSEA = .074, 90% CI [.068–0.08]) and predictive validity with the World Health Organization’s five-item Well-being Index (mother version: β = −.24, p < .001; father version: β = −.21, p < .001) and Sense of Authenticity Scale (mother version: β = −.12, p < .05; father version: β = −.27, p < .001 [Aktar et al., 2021]).

Japanese Shortened Version of the Teacher Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (Child TARQ-J-SF)

The shortened Japanese Child TARQ-J-SF (Aktar et al., in press) consisted of 18 items and was developed from Child TARQ (Rohner, 2005b) of the IPARTheory. Child TARQ-J-SF was applied to determine children’s current representations of acceptance-rejection behavior of their teacher. They were instructed to think about the teacher with whom they felt most attached at school while completing the items. Similar to the Child PARQ-J-SF, it also consists of four subscales: hostility/aggression (4 items), indifference/neglect (4 items), undifferentiated rejection (4 items), and warmth/affection (which was reverse scored to measure coldness/lack of affection as proposed by Rohner, 2005b). Items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale with responses ranging from (1) almost never true to (4) almost always true. Higher scores on the Child TARQ-J-SF represented individuals’ perception of increasing rejection, whereas lower scores indicated increasing acceptance. The Japanese shortened version of the Child TARQ-SF had satisfactory reliability (Cronbach’s alpha was .93) as well as construct (as IPARTheory proposed four-factor structure with adequate factor loadings [.78–.94], model fit WLSMVχ2(129) = 532.75, p < .001; CFI = .97; SRMR = .041; RMSEA = .072, CI 90% [.066–.078]) and convergent validity (concurrent validity with the World Health Organization’s five-item Well-being Index [r = −.35, p < .01]; Aktar et al., in press).

Best Friend Acceptance Scale (BEFAS)

The modified version of the acceptance from friends’ scale (Seki & Horii, 2019) was used to measure perceived relations with individuals’ “best friend”. We modified the expression of items from “my friends” to “my best friend”. A sample item from the Best Friend Acceptance Scale (BEFAS) included “My best friend says nice things about me”. The top highly loaded 14 items (item loadings of approximately ≥ .70, which denoted a good indicator of a factor (Beavers et al., 2013; Minkov & Hofstede, 2012) were selected for inclusion in the final survey items. The top highly loaded items were selected to maintain the maximum limit for the number of items for online data collection from children. Participants were requested to respond to the items on a 4-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (always true). A total score was calculated by summing the scores of all items.

Sense of Authenticity Scale (SOAS)

The 7-item Sense of Authenticity Scale was used (SOAS; Ito & Kodama, 2005) to measure the general subjective sense of being true to oneself, (i.e., the subjective internal state of an authentic person). A sample item from this scale included “I am who I am at all the times”. Participants were asked to respond on a 5-point Likert scale with responses ranging from 1 (disagree) to 5 (agree). A total score was calculated by summing the scores of all seven items. Past studies applied this scale to adolescents and demonstrated good reliability (Cronbach’s alpha was .88 [Suzuki & Ogawa, 2008]) and factorial validity for adolescent samples (Suzuki & Ogawa, 2008).

Prosocial Behavior Scale (PBS)

The Prosocial Behavior Scale (PBS (Murakami et al., 2016)) identified the target- oriented prosocial behaviors of children and adolescents. This scale had 18 items and consisted of three sub-scales: prosocial behavior toward family (e.g., “I carried a little heavy luggage that my family had”), friends (“When my friend did not understand a lesson, I tried to help him/her to understand”), and strangers (e.g., “When I was in a queue, I gave my place to a stranger”). Participants were requested to report how much they performed these acts on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = never to 4 = always). Sum of the scores of the respective scales constituted the total score of prosocial behavior toward family, friends, and strangers separately. This scale had sufficient internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .78 to .79 for three targets; Murakami et al., 2016) and satisfactory factorial and convergent validity (Murakami et al., 2016).

Data Analyses

Descriptive statistics were calculated and intercorrelations of all variables were performed as preliminary analyses to inform the models. Prior to model analysis, the multicollinearity between all observed predictor variables were also checked, and they were within the recommended ranges (Field, 2013) for variance inflation factor (< 10) and tolerance (> 0.2). To test the main study’s hypotheses and to test other additional paths (mentioned in the introduction), structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized using Mplus version 8.4. Model analyses were performed in two steps: first, measurement models of the mother and father Child PARQ-J-SF (tested together), Child TARQ-J-SF, and BEFAS were fitted to the model. If model fit was not acceptable as per the criteria (stated in the next paragraph), additional paths were adopted based on the theory and modification indices. Second, to investigate relationships among the latent constructs of interpersonal (mother, father, best friend, and teacher) acceptance-rejection, adolescents’ sense of authenticity, and target-oriented prosocial behavior the structural models were tested. These models enabled testing of the direct effects of perceived acceptance-rejection from multiple attachment figures on three target-oriented prosocial behaviors (Hypotheses 1 and 2) as well as the indirect effects of perceived acceptance-rejection from multiple attachment figures on target-oriented prosocial behaviors through sense of authenticity. Therefore, it also enabled the examination of the mediation hypothesis (Hypothesis 3). The basic model was specified based on the hypotheses and the findings of correlational analyses. Furthermore, after testing the basic model, all non-significant paths were trimmed, the fit of the trimmed (or parsimonious) model was tested and compared, and the best fitting model was selected according to corrected Δχ2 test (Satorra & Bentler, 2010) and the Akaike information criterion (AIC) values.

Models were estimated by employing the robust maximum likelihood estimation, which provided a robust Satorra-Bentler χ2. As χ2 is sensitive to sample size, the model fit was assessed using CFI, RMSEA with 90% CI, and SRMR indices. The overall fit of the model was considered acceptable when CFI ≥ .90, SRMR ≤ .08, and RMSEA ≤ .10 (Hair et al., 2014; Weston & Gore, 2006). To test mediation effects, the bootstrap method with 2000 samples was employed and the mediation was considered significant when the upper and lower 95% CI did not include zero.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

No missing data was found in the dataset (n = 784) of the present study. Table 1 depicts sample descriptive statistics and intercorrelations between variables. As stated earlier, acceptance-rejection was measured on a continuum, where higher scores in Child PARQ-J-SF (mother version & father version) and Child TARQ-J-SF indicated more rejection, whereas higher scores in the PBS and BEFAS indicated more prosocial behavior and perceived acceptance, respectively. Correlation analyses showed that significant and negative relations emerged between perceived maternal, paternal, and teacher acceptance-rejection and all three-target oriented prosocial behaviors. Likewise, significant and negative relations emerged between perceived maternal, paternal, and teacher acceptance-rejection as well as sense of authenticity. Furthermore, best friend acceptance was significantly and positively related to all three-target oriented prosocial behaviors as well as sense of authenticity. Sense of authenticity was significantly and positively related to the prosocial behaviors of adolescents toward three targets. In conclusions, perceived interpersonal (maternal, paternal, best friend, teacher) acceptance-rejection were significantly intercorrelated with prosocial behavior toward all three targets and sense of authenticity in adolescents.

Measurement Models

Before testing the measurement models, item-parcels were created as indicators of latent constructs for Child PARQ-J-SF, Child TARQ-J-SF, and BEFAS following Little et al. (2002), to lower measurement errors and enhance psychometric properties of the variables. Item-parcels for the Child PARQ-J-SF and Child TARQ-J-SF were composed of the individual four subscales that these measures consisted of. For the BEFAS, the parceling was conducted with an intention to obtain at least four item-parcels loading onto a latent factor, as recommended by Kline (2011), for adequate model identification. Item parcels for the BEFAS represented an average of individual items within each parcel.

Child PARQ-J-SF

A measurement model for the Child PARQ-J-SF was modeled with four subscales (coldness/lack of affection, hostility/aggression, indifference/neglect, and undifferentiated rejection) of mother version and four subscales (coldness/lack of affection, hostility/aggression, indifference/neglect, and undifferentiated rejection) of father version loading onto a single maternal acceptance-rejection factor and a single paternal acceptance-rejection factor, respectively. A correlation was tested between these two factors, accounting for common views of parents within families. As there were medium to large correlations (.49–.60) between matching sub-scales of the mother and father version of Child PARQ-J-SF, residual covariances were added between matching sub-scales after taking into consideration scale-specific shared variance. This model showed acceptable fit, χ2(15) = 56.72, p < .001, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .06, 90% CI = [.044, .08], SRMR = .02. All subscales of the mother and father version loaded significantly on their latent factors (maternal acceptance-rejection and paternal acceptance-rejection). Standardized loadings on the maternal acceptance-rejection factor and paternal acceptance-rejection factor ranged from .61–.94 to .64–.95, respectively. The correlation between these two factors of Child PARQ-J-SF was .66, p < .001.

Child TARQ-J-SF

The measurement model of Child TARQ-J-SF was tested with four subscales (coldness/lack of affection, hostility/aggression, indifference/neglect, and undifferentiated rejection) loading onto a single latent factor (teacher acceptance-rejection). This model did not fit the data, χ2(2) = 16.87, p < .001, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .10, 90% CI = [.06, .14], SRMR = .02. Modification indices indicated that teacher coldness/lack of affection and indifference/neglect shared supplementary variance that could not be explained by the latent teacher acceptance-rejection factor. As these two sub-scales may share similar indicators (i.e., emotionally cold teachers may be viewed as indifferent), so a residual covariance between coldness and indifference was added to the model. This model demonstrated good fit, χ2(1) = 2.78, p = .10, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI = [.00, .1], SRMR = .01. All four subscales loaded significantly onto the latent factor and the standardized loadings ranged from .50 to .95.

BEFAS

The measurement model for the BEFAS had five item-parcels loading onto a single latent factor (best friend acceptance). Parcels 1–4 delineated an average of three items per parcel while parcel 5 represented an average of two items. Item parcel 1 consisted of items 1–3, item parcel 2 consisted of items 4–6, item parcel 3 consisted of items 7–9, item parcel 4 consisted of items 10–12, and item parcel 5 consisted of items 13 and 14. This model showed good fit, χ2(5) = 15.38, p < .01, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .05, 90% CI = [.02, .08], SRMR = .01. Each item parcel significantly loaded onto the latent factor and the standardized loadings ranged from .85 to .93.

Structural Models

Considering the hypotheses and findings from the correlation analyses, a basic model was specified. More specifically, adolescents’ feelings of acceptance-rejection from attachment figures (mother, father, teacher, and best friend) and sense of authenticity were assumed to be related to their prosocial behaviors toward strangers, friends, and family in the basic model. The results of the SEM analysis exhibited a good fit for the basic model (see Table 2). As the basic model was also built considering significant correlations between variables in addition to the main hypotheses, the non-significant paths were pruned (to create a parsimonious model), and the model fit was assessed; this model also showed good fit (see Table 2).

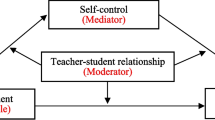

From Table 2 it is apparent that the parsimonious model significantly reduced in fit in terms of χ2 and AIC values (smaller is better). The basic model was considered as the best fitting one (see Fig. 1), which has been explained in details below.

Direct and Indirect Effects of Perceived Acceptance-Rejection from Mother, Father, Teacher, and Best Friend on Prosocial Behavior Toward Strangers, Friends, and Family as Mediated by Sense of Authenticity. Standardized coefficients are presented. Solid lines indicate significant paths. Gray lines denote non-significant paths. Excluded from the figure for parsimony are endogenous error correlations. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Parental Acceptance-Rejection and Prosocial Behavior

Hypothesis 1

Perceived paternal and maternal acceptance-rejection would be negatively and directly associated with prosocial behavior toward family.

Figure 1 depicts that perceived paternal acceptance-rejection significantly directly predicted adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward family. The findings suggested that increased paternal acceptance was associated with increased prosocial acts toward family in adolescents and increased perceived rejection from fathers might be responsible for reduced prosocial enactment in adolescents. Contrary to our expectation, maternal acceptance-rejection did not directly predict prosocial acts toward family (β = −.08, p = .15). Therefore, the findings of the SEM analysis partially supported Hypothesis 1.

As mentioned earlier, based on the findings from the correlational analyses, the direct paths from paternal and maternal acceptance-rejection to prosocial behavior toward friends and strangers were also tested (see Fig. 1). The SEM analysis showed that only paternal acceptance-rejection was directly and negatively associated with adolescents’ prosocial acts toward friends and strangers, whereas maternal acceptance-rejection was not directly associated with prosocial behavior toward friends (β = −.02, p = .66) and strangers (β = .03, p = .53).

As the findings indicated that paternal acceptance-rejection was significantly and directly related to prosocial behavior toward all three targets, further analyses were performed (by constraining the paths to be equal across the three targets) to investigate the strength of the association between paternal acceptance-rejection and all three targets. Analyses suggested that the model fit did not reduce when the paths from paternal acceptance-rejection to prosocial acts toward three targets were constrained to be equal, thus indicating that the strength of relationships between paternal acceptance-rejection and prosocial acts toward all three targets did not significantly vary.

Best Friend Acceptance and Prosocial Behavior

Hypothesis 2

Perceived best friend acceptance would be positively and directly associated with helpfulness behavior toward friends.

As seen in Fig. 1, the SEM analysis reflected that adolescents’ representations of acceptance from their best friend significantly directly and positively predicted prosocial behavior toward friends, indicating that increased acceptance from adolescent’s best friend is directly associated with increased prosocial acts toward friends. This finding supported Hypothesis 2.

Furthermore, the additionally tested direct paths (based on the findings from correlational analysis) from best friend acceptance to adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward family and strangers depicted that perceived acceptance from adolescent’s best friend significantly and positively predicted prosocial behavior toward friends and family (see Fig. 1), but not toward strangers (β = .02, p = .72).

The analysis yielded significant direct associations between best friend acceptance and prosocial behavior toward friends and family; therefore, further analyses were performed (by constraining the paths to be equal across these two targets) to investigate the strength of the association between best friend acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior toward friends and family. The model fit declined (Δχ2(1) = 20.79, p < .001) when the path from best friend acceptance to prosocial acts toward friends were constrained to be equal to the path from best friend acceptance to prosocial acts toward family. This finding suggested that perceived best friend acceptance was more strongly related to prosocial acts toward friends than that toward family.

Teacher Acceptance-Rejection and Prosocial Behavior

As mentioned in the introduction, the direct paths from teacher acceptance-rejection to adolescents’ prosocial acts toward family, friends, and strangers were tested. The SEM analysis indicated that, perceived teacher acceptance-rejection significantly and directly predicted only prosocial behavior toward friends, but not toward family (β = −.02, p = .71) or strangers (β = .07, p = .11) (see Fig. 1).

Although not shown in Fig. 1, the endogenous error correlations were significant (prosocial behavior toward strangers and friends r = .46, p < .001; strangers and family r = .53, p < .001; family and friends r = .50, p < .001).

The Mediating Role of Sense of Authenticity

Hypothesis 3

Sense of authenticity would mediate the relationship between interpersonal (mother, father, best friend, and teacher) acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior toward strangers.

Figure 1 further shows that maternal (not paternal: β = −.09, p = .10) acceptance-rejection and best friend acceptance (not teacher: β = −.08, p = .076) was independently associated with adolescents’ sense of authenticity. In turn, sense of authenticity in adolescents was associated with prosocial behavior toward strangers (β = .12, p < .01). As mentioned earlier, the co-existence of these paths for prosocial behavior toward friends and family was tested additionally. The analysis indicated that sense of authenticity was not associated with friends (β = .07, p = .12) and family (β = .04, p = .37).

Table 3 demonstrates the indirect effect of acceptance-rejection from attachment figures through sense of authenticity on prosocial behaviors. The analyses found that the indirect effect of maternal acceptance-rejection on prosocial behavior toward strangers was significant (however, with small effect). In addition, the indirect effect of best friend acceptance on prosocial behavior toward strangers was also significant (however, with small effect).

The SEM analysis suggested that sense of authenticity fully mediated the association between maternal acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior toward strangers as well as that between best friend acceptance and prosocial acts toward strangers, since no significant direct path was detected from maternal or best friend acceptance to prosocial acts toward strangers when controlling for the effect of sense of authenticity. Therefore, the analysis partially supported the mediation hypothesis (Hypothesis 3), yielding significant indirect effect of perceived maternal (not paternal) and best friend (not teacher) acceptance on helpfulness behavior toward strangers through sense of authenticity.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate the direct association between perceived acceptance-rejection from multiple attachment figures (mother, father, best friend, and teacher) and adolescents’ prosocial behavior towards strangers, friends, and family, and their indirect associations through sense of authenticity on prosocial behavior. Furthermore, this study investigated the mediating role of sense of authenticity in these relationships. Current findings demonstrated that the factors influencing prosocial acts toward close persons (i.e., family and friends) differed from those of prosocial behavior toward strangers; moreover, both parental and non-parental acceptance-rejections had an independent influence on target-oriented prosocial behavior. In addition, the findings found that sense of authenticity fully mediated these relationships. Overall, the findings of the present study are in line with the relational and dispositional approaches of prosocial behavior (e.g., Eisenberg et al., 2006, 2015; Fu et al., 2017; Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011; Padilla-Walker et al., 2018). The current study results are presented in relation to past literature as well as the cultural context of Japan (mentioned earlier in the introduction).

Parental Acceptance-Rejection and Prosocial Behavior

As expected, perceived paternal acceptance-rejection was significantly directly related to helpfulness toward family, which is consistent with previous literature (Padilla-Walker et al., 2016, 2018). In contrast, a direct significant path between maternal acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior toward family, friends, and strangers was not found. Previous findings also showed a mixed finding for maternal roles in this relationship. For example, few studies showed that maternal warmth or related constructs had a direct influence on family related prosocial behavior (Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011; Padilla-Walker et al., 2018), while one study found no relationship (Eisenberg et al., 2006). One study found an indirect relationship between the mother–child relationship and prosocial behavior (Barry et al., 2008). Findings may vary as a function of the informant and the type of analysis performed (Eisenberg et al., 2015; Padilla-Walker et al., 2016). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was partially supported.

Incrementally, the study findings showed that paternal (not maternal) acceptance-rejection was directly related to prosocial acts toward friends and strangers. This finding is in line with the findings of Padilla-Walker et al. (2018), that concluded paternal practices also promoted prosocial behavior toward individuals beyond family. Similar to our findings, Padilla-Walker et al. (2016) found that paternal hostility (i.e., a construct of rejection) was associated with adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward family, friends and strangers. However, maternal hostility was not related to prosocial behavior toward any target in their study. Nevertheless, unlike the current study, they considered parental warmth and hostility as separate dimensions.

The current study findings suggest that, for Japanese adolescents, paternal acceptance-rejection is not only an active socializer to those within the family, but also incrementally to those outside the family. Analyses further indicated that the role of paternal acceptance-rejection on benevolent behaviors did not vary across recipients of prosocial behaviors. This could be because for Japanese adolescents’ fathers are stronger socializers at home and for outside behavior, compared to mothers. In recent times, traditional perceptions regarding the gender roles of Japanese parents have been changing due to government policies and changing workplace conditions (Lamb, 2010). Consequently, women have entered the workforce; thus, both men and women contribute to the service of nation-building (Holloway & Nagase, 2014). Therefore, profound reformations in child rearing practices and family life are taking place, whereby fathers are becoming more involved in child rearing activities and are perceived today as nurturing within the Japanese family (Lamb, 2010). Past studies on Japanese preschoolers corroborated that paternal involvement and acceptance was significantly linked to children’s social skill and development (Kato et al., 2002). Furthermore, Rohner (2019) concluded that father acceptance sometimes might act as unique predictor of some particular outcomes. Japanese adolescents’ representations of each parental prestige and interpersonal power within the family context can be a cause of substantial difference in the effects of paternal and maternal acceptance-rejection on prosocial behavior as IPARTheory also claims that children’s perception of interpersonal power and prestige within the family context can play a moderating role between parental (paternal and maternal) acceptance-rejection and children’s psychosocial development (Rohner, 2019). Therefore, it is a matter of further study to understand the relative prestige and interpersonal power of mothers and fathers within the Japanese family to understand the differential effect of mother and father acceptance-rejection on prosocial behavior.

Best Friend Acceptance and Prosocial Behavior

While past studies have highlighted the role of peers on children prosocial behavior (Eisenberg et al., 2015) or particularly, friends’ connectedness on adolescents’ overall and friend-oriented prosocial behaviors (Padilla-Walker et al., 2015b, 2018), few studies corroborated the role of perceived acceptance from best friend on prosocial behavior toward family, strangers, and friends. This study findings suggested that acceptance from best friend significantly predicted helping behavior toward friends and family, but not toward strangers. As expected, the direct association between Japanese adolescents’ best friend acceptance and benevolent acts toward friends was consistent with a past study (Padilla-Walker et al., 2015b); therefore, Hypotheses 2 was supported.

In addition, to supporting this relational hypothesis, current findings interestingly showed that best friend acceptance was related to adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward family, thus suggesting that adolescents’ bond with friends also influences family-related prosocial behavior. However, compared to benevolent acts toward family, benevolent acts toward friends were strongly associated with best friend acceptance. Although developing close relationships with peers is a universal task in adolescence, due to cultural influence, Japanese adolescents’ qualitatively (attachment & acceptance) and quantitatively (longer time spent with peers in schools) bear a stronger association with friends and peers than adolescents from other countries (Deković et al., 2002). Moreover, as mentioned earlier, developing close relationship with peers and making a best friend is considered an important indicator of interpersonal identity development in the Japanese context (Hatano et al., 2019). This strong association with a close friend may uniquely facilitate sharing of family-related issues and modeling of helpfulness behaviors beyond the friends. Similarly, a longitudinal study found that during adolescence the influence of friends becomes equally important as parents and friendship strongly affect parent–child interaction and mutual conduct (De Goede et al., 2009). However, future research should aim to investigate the association between friend attachment and prosocial behavior toward different targets, without being limited to helpful acts toward friends.

Teacher Acceptance-Rejection and Prosocial Behavior

As mentioned earlier, existing studies on teacher-student relation supported the notion that studies wherein positive relationships with teachers were found to facilitate students’ prosocial behavior were mostly based on children (Luckner & Pianta, 2011). For the first time, this study examined the role of teacher acceptance-rejection on adolescents’ target-oriented prosocial enactment; the results showed a direct link between teacher acceptance-rejection and prosocial behavior towards friends only. Similarly, the conclusions of several past studies corroborate our finding (Hendrickx et al., 2017; Luckner & Pianta, 2011) and these studies suggested that teachers’ warmth and emotional support promoted peer liking and prosocial behavior toward peers, whereas lack of affection and less support from teachers induced peer disliking and reduced prosocial behavior toward peers. Furthermore, it has been claimed that teachers invisibly guide peer relations (Farmer et al., 2011) and that children perceive their peers or friends (a subset of peers; Santrock, 2014) in the same way as teachers do (Hendrickx et al., 2017). Japanese adolescents are quite attached to their teachers, and actively internalize their teachers’ deeds (Bear et al., 2016; Toyama-Bialke, 2004). Aktar et al. (2020) showed that teacher acceptance-rejection also determined peer relationships among Japanese junior high school students. Moreover, teachers in Japanese schools adopted various strategies to reinforce prosocial behavior among children (Stevenson, 1991). In addition, Japanese adolescents most commonly chose close friends from schools. For example, about 94% junior high school students selected their best friends from school, rather than from outside of school (Cabinet Office, 2010). Thus, it should be considered that teachers are also active socializers for Japanese adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward friends; however, further studies are needed to verify this finding.

Role of Sense of Authenticity

As expected, results showed that adolescents’ representation of acceptance-rejection from attachment figures was associated with their sense of authenticity that, in turn, was related to prosocial behavior toward strangers. Findings of the study are consistent with the postulates of the personality sub-theory of IPARTheory (Rohner, 2019; Rohner & Lansford, 2017) and Thomaes et al. (2017) that suggest positive responses (i.e., acceptance) are associated with positive psychological functioning and subjective authenticity. However, such empirical evidence, particularly for parental and non-parental attachment figures was not present in past studies. The current study revealed that particularly maternal and best friend acceptance (not paternal and teacher) were significantly associated with sense of authenticity. In addition, a past study showed that college students’ recollections about maternal parenting practices were more strongly associated with their current authenticity, compared to paternal practices (Kernis & Goldman, 2006). Similarly, Li and Meier (2017) synthesized that maternal acceptance (vs. paternal) was more frequently associated with self-related outcomes (e.g., self-esteem and self-worth). Japanese mothers allow their children to make their own choices (Sugimura et al., 2009), while nurturing kindness and empathy among them (Holloway, 2010), which might be the reason for the associations among maternal acceptance-rejection, sense of authenticity, and adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward strangers. Therefore, this study finding suggests that maternal acceptance-rejection is more strongly associated with sense of authenticity than paternal acceptance-rejection.

In the case of adolescents, best friends are the people to whom they disclose their true selves, desires, and emotions. Consequently, opening up leads to increased feelings of authenticity in an individual (Thomaes et al., 2017). The current study showed that sense of authenticity among adolescents was related to prosocial acts toward strangers (but not toward friends and family). Thus, to our best knowledge, the present study pioneered in investigating the association between adolescents’ sense of authenticity and prosocial behavior. This finding further empirically supports Kernis and Goldman’s (2006) claim that subjective authenticity is not reflected in an attempt to increase self-centered inclinations, to appease others for social rewards, or to avoid punishment. Instead, positive effects of sense of authenticity go beyond the personal level and extend to benefitting others. As sense of authenticity is the foundation of optimal self-esteem, this result was also in line with Fu et al. (2017) who found that adolescents’ self-esteem was only related to prosocial behavior toward strangers.

Incrementally, the findings of the present study showed that adolescents’ sense of authenticity fully mediated the relationship (however, with small effect) between maternal and best friend acceptance (not paternal and teacher) and prosocial behavior toward strangers. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was partially supported and further studies are required to verify whether acceptance-rejection from different attachment figures differently influences adolescents’ prosocial behavior toward strangers through sense of authenticity in adolescents. Overall, the meditational role of sense of authenticity supports that dispositional factors act as mediators between relational factors and prosocial behavior, as well as predictors of prosocial behavior toward strangers substantially vary from other targets (Eisenberg et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2017; Padilla-Walker & Christensen, 2011).

Implications of the Study

This study attempted to understand the association between acceptance-rejection from parental and non-parental attachment figures and adolescents’ target-oriented prosocial behavior through their sense of authenticity in a comprehensive manner. The findings of this study have potential implications for parents, educators, researchers, and practitioners. To illustrate, the findings suggest that acceptance, or love, play a vital role in developing and fostering the true self among adolescents, which is inevitable for optimal development. Parents or school-based programs should focus on delineating clear expressions of acceptance strategies so that children do not perceive undifferentiated rejection from attachment figures. For Japanese adolescents, mothers and fathers can differently influence prosocial behavior; thus, practitioners and interventions should strongly focus on the importance of fathering, in addition to mothering, for the prosocial development of Japanese adolescents, as the findings showed that fathers could directly promote or hinder children’s helpfulness acts toward all three targets. In addition, teachers should be included in intervention programs targeted toward adolescents, as they directly influence and may invisibly facilitate prosocial behavior toward friends (a subgroup of peers of school environment).

Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

This study has a number of notable strengths. First, the findings of the study were based on a uniquely focused large sample of adolescents in Japan. Adolescents were sampled from all over Japan, which resulted in increased generalizability of the findings. The present study contributed to the literature on multidimensional prosocial behavior during adolescence by adding new evidence in a cross-cultural setting. Second, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the associations between interpersonal acceptance-rejection and target-oriented multidimensional prosocial behavior of adolescents. Relational and dispositional factors were considered in this study and the association between these factors and their influence on prosocial behavior was determined. Third, our findings further revealed that the predictors of prosocial behavior toward strangers are different from those towards friends and family. Fourth, unlike other studies, this investigation simultaneously examined the influence of acceptance-rejection from multiple attachment figures (mother, father, teacher, and best friend) on adolescents’ prosocial acts in a single study. Moreover, the influence of maternal and paternal acceptance-rejection was determined and compared. In addition, the association between teacher and best friend acceptance-rejection and adolescents’ multidimensional prosocial behavior was included for the first time in an investigation. Fifth, well-validated measures were used in this study.

The study had certain limitations. First, data were collected within a single timeframe, which could have influenced the results. Therefore, future studies should confirm these relationships by adopting a longitudinal design. Second, this study included only adolescents’ self-reported data (IPARTheory is also predominantly based on self-reported evidence). Further studies should additionally incorporate reports from multiple sources (parents, friends, and teachers) to explain the relationships and to control for common source bias. Third, this study did not examine the role of gender in these relationships; therefore, future studies should investigate gender roles. Fourth, all measures of personal relationship except for the BEFAS were based on acceptance-rejection constructs from the IPARTheory; thus, future studies should consider including a IPARTheory-based scale to measure best friend acceptance-rejection to ensure uniformity in the targeted construct. Finally, our prosocial behavior scale toward family was developed by considering family in general; thus, it was unable to measure prosocial behavior particularly toward mothers and fathers. Future investigations should specify the target of prosocial behavior toward mothers and fathers for a more effective account of this relationship.

Despite above limitations, this study provided beneficial insights into the unique role of parental and non-parental acceptance-rejection on adolescents’ multidimensional prosocial behavior. It contributes preliminary integrative findings to the IPARTheory domain as well as to existing literature related to target-oriented prosocial behavior beyond the Western world. While further verification of these findings is warranted, this study emphasized the important role of paternal acceptance-rejection for Japanese adolescents’ development. It also demonstrated that acceptance indirectly influenced prosocial behavior by fostering adolescents’ sense of authenticity, which indicated that being loved encourages adolescents in Japan to become more open, thus facilitating increased feelings of authenticity and eliciting kind behaviors. Therefore, the benefits of providing acceptance or love in a relationship are reciprocal and offer personal benefits and increased welfare of others.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/ or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

The codes generated during analyses of the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

References

Aktar, R., Sugiura, Y., & Hiraishi, K. (2020). The association between teacher acceptance and sense of authenticity as mediated by peer acceptance in Japanese adolescent boys and girls. Jurnal Psikologi Malaysia, 34(4), 97–110.

Aktar, R., Sugiura, Y., & Hiraishi, K. (2021). “They Love Me, They Love Me Not”: An IRT-based investigation of the Child Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire with a Japanese sample. Japanese Psychological Research. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpr.12346

Aktar, R., Sugiura, Y., Uddin, M., K., & Hiraishi, K. (in press). An IRT approach to assessing psychometric properties of the Japanese version Teacher Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire. Bangladesh Journal of Psychology.

Azuma, H. (1986). Why study child development in Japan? In H. Stevenson, H. Azuma, & K. Hakuta (Eds.), Child development and education in Japan (pp. 3–12). Freeman.

Baker, Z. G., Tou, R. Y. W., Bryan, J. L., & Knee, C. R. (2017). Authenticity and well-being: Exploring positivity and negativity in interactions as a mediator. Personality and Individual Differences, 113, 235–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.018

Barry, C. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Madsen, S. D., & Nelson, L. J. (2008). The impact of maternal relationship quality on emerging adults’ prosocial tendencies: Indirect effects via regulation of prosocial values. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(5), 581–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-007-9238-7

Bear, G. G., Chen, D., Mantz, L. S., Yang, C., Huang, X., & Shiomi, K. (2016). Differences in classroom removals and use of praise and rewards in American, Chinese, and Japanese schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 53, 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.10.003