Abstract

The aim of the case study was the evaluation of the effect of Animal-assisted education (AAE) within the two children (Tobias and Emily) diagnosed with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). AAE took part in a private primary school during one school year. AAE was practiced with a dog. The severity of ADHD symptoms was evaluated by the teacher using The Conners Scale: Teacher Questionnaire (Conners in American Journal of Psychiatry 126: 884–888, 1969) before and after AAE. Results of the teacher’s rating, and teacher’s and experimenter’s observation showed the beneficial effect of participation of a dog in the classroom. A decrease in the severity of ADHD symptoms, as well as the improvement in concentration, communication with teachers, and co-operation with their peers in the classroom, was observed. Based on the study results, using a dog as a part of AAE within children with ADHD appears to be a beneficial activity, and an alternative treatment method to eliminate the ADHD symptoms. However, further researches are needed to support our findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The primary treatment approach for children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is medication (Danielson et al. 2018; Leuzinger-Bohleber, 2010) that can show the short-term behavior improvement in terms of attention and hyperactivity (Duric, Assmus, Gundersen, & Elgen, 2012). However, there is a lack of research on the long-term effects of medication (Susan & Myers, 2008). Medication treatment has not confirmed positive long-term effects on academic outcomes (Langberg & Becker, 2012), cognition (Swanson, Baler, & Volkow, 2011), social relationships (Mrug, Molina, Hoza, Gerdes, Hinshaw, Hechtman, & Arnold, 2012), or functional impairment and adaptive behaviors (Epstein, Langberg, Lichtenstein, Altaye, Brinkman, House, & Stark, 2011) in children with ADHD (for review see Schuck, Emmerson, Fine, & Lakes, 2015). For this reason, many parents and teachers are looking for some alternative methods to manage ADHD symptoms in their children (Susan & Myers, 2008).

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder with a worldwide prevalence among children characterized by chronic symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity (DSM–V; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Affected children display excessive psychomotor activity and they cannot focus on a particular activity for a prolonged period. Children are characteristically impaired by deficits in executive functions, including attention, working memory (Schuck, Emmerson, Fine, & Lakes, 2015), and inhibitory control (Martínez, Prada, Satler, Tavares, & Tomaz, 2016). ADHD negatively impacts academic performance (Mautone, Lefler, & Power, 2011), social skills (teacher report), and problem behaviors (teacher and parent report) (O’Haire, McKenzie, McCune, & Slaughter, 2014). Children with ADHD negatively affects the responding to social cues, collaborating behavior, empathizing, and exhibit a self-oriented focus in the interaction with other children (Wilkes-Gillan, Bundy, Cordier, Lincoln, & Chen, 2016). Obviously, dealing with these difficulties may pose a problem after entering the school, not only for children, but also for their parents, teachers, and peers.

Animal-assisted therapy (AAT) is a structured, goal-oriented therapy that intentionally uses the involvement of animals in health, education, and social programs. AATs are often a complement or adjunct to other therapies, sometimes also stand-alone intervention (Schuck, Johnson, Abdullah, Stehli, Fine, & Lakes, 2018). Animals have been perceived as enabling a safe and trusting relationship between the child and the animal and offering many therapeutic benefits (Balluerka, Muela, Amiano, & Caldentey, 2014). AAT studies in child population reported reduced aggressiveness and hyperactivity (Garcia-Gomez et al., 2014), and improvements in social functioning (e.g., sensory seeking, inattention-distractibility) (Bass, Duchowny, & Llabre, 2009), adaptive functioning (Gabriels et al., 2012), irritability, hyperactivity, social cognition, and communication (Gabriels et al., 2015), interpersonal relations and social inclusion (Garcia-Gomez et al., 2014), and in attitudes towards learning (Beetz, 2013). Although most of the reviewed evidence is based on samples other than the ADHD population, the positive effect of AAT was also reported in many core symptoms of ADHD (Busch, Tucha, Talarovicova, Fuermaier, Lewis-Evans, & Tucha, 2016).

One of the various settings where animals can be involved, include animal-assisted education (AAE), to convey or simplify the teaching in a daily school setting. Although children with ADHD may be more excitable, and react to a dog differently than typically developing children (Busch et al., 2016). Several studies showed AAT as encouraging the calming and de-arousing effects in children suffering from ADHD (Busch et al., 2016), and greater reductions in the parent-rated severity of ADHD symptoms (Schuck et al., 2015). AAE has been used to improve co-operation, social functioning (O’Haire, 2013), and social relationships in the classroom (Beetz, Uvnäs-Moberg, Julius, & Kotrschal, 2012; Tissen, Hergovich, & Spiel, 2007). AAE also has great potential to make learning more arresting (Swartz, Le Roux, & Swart, 2015). Especially dogs have been observed to improve attitudes regarding school and to learning (Beetz, 2013), reduce aggression, and increase empathy (Tissen et al., 2007), positively stimulate social cohesion in children (Kotrschal & Ortbauer, 2003).

In general, AAE was found to reduce aggression (Tissen et al., 2007), increase concentration skills (Wohlfarth, Mutschler, Beetz, Kreuser, & Korsten-Reck, 2013), improve speech abilities (Baars & Wolf, 2011; Gee, Harris, & Johnson, 2007) and social skills (Esteves & Stokes, 2008; Funahashi, Gruebler, Aoki, Kadone, & Suzuki, 2014; Murry & Allen, 2012; Tissen et al., 2007). The overall calming effect of the presence of a dog (Hoffmann et al., 2009; Lange, Cox, Bernert, & Jenkins, 2007; Prothmann et al. 2005) was also reported. In ADHD, interacting with animals can reduce hyperactivity and physical arousal, poor social interactions, impulsive class disruptions (Busch et al., 2016), increase the attention to a teacher (Kotrschal & Ortbauer, 2003), reduce anger, and improve coping skills (Kelly & Cozzolino, 2015). AAT allows students with ADHD to develop relationships and attachments without judgment with peers, or teachers (Hart et al., 2017; Horowitz, 2010). However, only a few studies are evaluating the effect of AAE across students with ADHD symptoms in the classroom (Schuck, Emmerson, Fine, & Lakes, 2013).

In general, in the student population, animal-assisted interactions (AAI) seem to improve the hyperactivity (Garcia-Gomez et al., 2014; Gabriels et al., 2015), learning abilities, or social relationships and functioning in the classroom (Beetz et al., 2012; O’Haire, 2013; Tissen et al., 2007). These domains are affected also in children with ADHD, in whom the AAT may be an alternative (separate or adjunct) treatment to manage or reduce ADHD symptoms (Susan & Myers, 2008). To remediate this knowledge gap, we observed the interaction of a therapy dog and children with ADHD in the school environment, and its influence on the integrating of ADHD children into the classroom collective. We hypothesized that concretely AAE may positively influence the integrating of children in a classroom collective, and in building relationships with their peers. To get deeper and more exact information about this topic, we chose a case study design.

Methods

Participants

The participants of AAE were two children (a boy and a girl) diagnosed with ADHD studying at a private primary school in the Czech Republic. More details about participants are reported in the results. Also, the teacher of both respondents participated in the study, especially to evaluate the participants´ classroom, group, and authority behavior. Informed consent was signed by both participants´ caregivers. The approval of the study was also obtained from the school management where the study was conducted.

Procedure

Animal-assisted education in our study was implemented in a private primary school practicing a child-specific approach-actively integrating students with special needs into a standard collective of classmates. A dog (White Swiss Shepherd) participated in both, inside and outside classroom lessons, during one school year. The dog attended the lessons of three school subjects: Dramatic Education, Physical Training, and the Czech language (subjects were chosen based on the willingness of the teacher to let the dog participate in the lessons). Each lesson lasted 45 min, once a week. Due to the special needs of participants, lesson activities alternated, and lessons were divided into shorter periods of time. During every lesson, participants were encouraged to be independent in their activities, to co-operate as part of the collective of classmates, and to perform their varying tasks with the involvement of the dog using diverse tools such as a leash, a muzzle, a harness, etc. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were following the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration, and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All applicable international, national, and/or institutional guidelines for the care and participation of animals were followed.

Measurements

The Conners Scale: Teacher Questionnaire (Conners, 1969) was used to measure teacher’s perception of classroom behavior, group behavior, and authority behavior. The teacher rating scale was developed and comprised of 39 items or symptoms, rated on a 4-point Likert scale (“0–3”, where “0” indicates the absence of the problem, and “3” indicates the most significant assessment (0: not at all, 1: minor extent, 2: considerable extent, 3: very significant extent). Factor analysis (Conners, 1969) found five orthogonal factors of the scale: Conduct Problem, Inattentive/Passive Behavior, Tension/ Anxiety, Hyperactivity, and Sociability. Items of the scale are differed in three subscales: classroom behavior, group behavior, and authority behavior. Higher total score of the scale and subscales indicates more severe symptoms of ADHD. This evaluation was carried out before the start of the implementation of AAE, as well as after the school year during which the dog was present in lessons.

Listed exercises were chosen specifically to help to remediate baseline issues identified with the two children, and were created as alternatives based on the school education program. They were designed to integrate as a follow-up unit throughout the school year in each of the three subject lessons (drama, physical training, and language) each week The interaction with the dog involved several possible procedures, which were set up and then alternated to avoid weakened attention of the presented children. All teachers and parents agreed with suggested interactions, and activities practiced as a part of the teaching process. The following activities were practiced in the study:

-

1.

Exercises to relax the hand/develop fine motor skills The participant was assigned the role of a keeper and instructed to wiping the dog with a towel, combing, petting, or calculating and distributing dry kibbles (as rewards) into small piles. The participant could also give a treat with their dominant hand to the dog and to pet the animal as a reward for having managed each individual section of the work.

-

2.

Exercises to develop spatial (left to right) orientation in terms of the plane field The child watches the dog roam freely around the classroom. First, after giving the Stop command, the dog stands still and the child is asked to describe where the dog is now, applying spatial abilities. Second, after giving the Sit command, the child is asked to draw all the dog’s locations. Subsequently, the pictures of the dog’s locations are assigned by spatial abilities by the child in the co-operation with the handler. Third, the child is tasked to leash the dog and walk through a route devised by classmates (e.g. go right, go behind the desk, sit down next to the blackboard, etc.), to increase the interactions of all classmates.

-

3.

Exercise to improve the child’s drawing and presentation skills The child is assigned a task to draw a dog-associated experience and, subsequently, comment on the artwork in front of the classmates.

-

4.

Exercise focus on reading comprehension The “Diary of white paw” was read along with all the classmates. The participants were asked to say what the class read about after a short section of reading was completed. During the reading, the participant responded to the questions found in the text.

Results

Results of the First Case Study

The first participant was a 7 years old boy, we will call him Tobias. From his anamnesis, he grows up in a well-functioning family with no history of mental health or developmental concerns. Intellectual skills within the intermediate zone (IQ = 85–115) was reported, with dysorthography (a specific dysgraphic disorder of spelling which accompanies dyslexia by a direct consequence of the phonological disorder), difficulties in attention, and family relations. Postponement of school attendance was recommended, but not implemented.

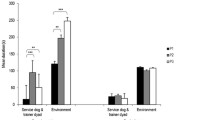

The results of the Conners Scale: Teacher Questionnaire was used to evaluate the severity of ADHD. A higher total score of the subscales indicates more severe symptoms of ADHD. In the classroom behavior subscale, Tobias´s achieved 31 points at the beginning of the school year. At the end of the school year, the score was reduced to 9 points (see Table 1). In the group behavior section, Tobias´s score at the beginning of the school year was 17 points, and at the end of the school year, it was 4 points (see Table 2). In the last part of the Connors scale focused on authority behavior, the boy’s initial score was 8 points and at the end of the school year, the score equaled three points (see Table 3). The overall total score decreased from 56 to 16. The decreasing scores indicate decreased severity of symptoms.

Results based on the observation before the AAE, Tobias showed no difficulties in social contact-making, but a state of constant psychomotor restlessness while examination—mostly in the beginning of the activity, and attention bound by secondary stimuli. The specified task was always completed despite such stimuli. Reading skills were at the appropriate level; it was observed a clear separation of words, reading form restrained syllabification, fragmentary understanding, reproducing the content in points, but these skills seemed to be still developing. Writing showed a graphomotor weakening. The grip of writing was within a standard, the arm was less relaxed, and excessive pressure on the pencil was observed. Increased fatigue while writing, was manifested by head holding extremely low over the pad, or even putting the head on the desk. Crossed laterality was found. The predominance of the right hand has already settled, leading eye left. Right-left orientation was managed on his own body; orientation in-plane field and space were problematic. The level of visual perception was within the standard. In the area of auditory perception, auditory synthesis (assembling words from phones) appeared to be weakened- long words and consonant aggregations made difficulties.

Prior to the therapy, the boy had difficulties maintaining any activity. He was very explosive and quarreling, and the schoolmates refused to let him be part of their group. He was sometimes cheeky also toward the teacher. According to Conners Scale: Teacher Questionnaire, teacher reported that Tobias demanded instant satisfaction, was restless and sensitive to criticism. He seemed to be easily influenced by others and needed someone to supervise him. He irritated other children or intervened in their affairs. In relation to authority figures, he did not show any greater difficulties.

After completing the school year with AAE, the teacher observed an overall improvement of behavior and more pro-active participation in the activities of the collective of classmates. In the context of evaluation using the scale of attitudes toward authority figures, his ratings improved in all items. Tobias enjoyed the interaction with a dog, and their interaction could be considered a beneficial option for ADHD therapy. As soon as the door of the classroom was opened, Tobias ran towards the dog, not taking into account of the handler, until getting an assignment from the handler. He enjoyed coming up with joint activities and the dog became his best partner throughout the lessons in terms of motivation, rectification, and understanding. All the activities described above, elaborated into specific tasks with the dog as recommended, were completed by Tobias with a great portion of willingness and enthusiasm. Moreover, the presence of the dog had a positive impact in terms of Tobias´ motor skills, spatial orientation, encouraging in promoting drawing skills, and reading comprehension.

Results of the Second Case Study

The second participant was a 6 years old girl, we will call her Emily. From her anamnesis, she grew up in a functioning family, but she was adopted several years ago by the new family and the adaptation went without any problems. At the time of the study, Emily reported that she feels safe at home, and she called her new parents as mom and dad, although she remembered the former family.

Results of The Conners Scale: The Teacher Questionnaire showed Emily´s initial score of 31 points in the classroom behavior subscale. At the end of the school year, the score was reduced to 10 points (see Table 1). In the group behavior subscale, Emily´s score changed during the school year from 15 to 4 points (see Table 2). In the authority behavior, the initial score was 18 points, and at the end of the school year, the score was reduced to two points (see Table 3). The overall total score decreased from 64 to 16. Also, in this case, the decreasing scores indicate decreased severity of symptoms.

Emily is a girl with a mild mental disability determined by a medical examination and with also attention and activity disorders, lack of concentration, poor vocabulary, low self-confidence, shyness, and feelings of being emotionally unfulfilled. It is necessary to follow the rules of working with child with central nervous system impairment and respect psycho-hygienic principles. At any opportunity, she loved snuggling up to an adult towards whom she built trust very quickly. She also needed the personal contact and proximity of an adult in performing the tasks assigned. Social skills were of a particularly good level and the girl was very friendly. However, the symptom revealing a lack of attention was the slow pace at which she completed her work. During the lessons, she needed a small space for relaxation in the form of physical activity, to switch locations and body positions. Also, a constant motivation, encouraging her self-confidence, and rewarding the successes were needed. She has an individual education plan.

Prior to the beginning of AAE, Emily showed a considerable lack of concentration and self-confidence, timidity, emotional unfulfillment as evidenced by being too shy and afraid to engage in any activity without support of someone she trusts. She likes to snuggle on any occasion for an adult she trusts very soon. Attention is combined with a slow work pace. For Emily, communication is preferred to the success of school work. She needs personal contact, closeness of an adult in performing assigned tasks. Constant motivation is needed. There must be a moment of relaxation in the lesson. Whenever she engaged in a classroom activity, she needed someone, class aid or teacher, to keep her motivated and support her all the time. Due to the Conners Scale, she exhibited problems particularly in the following listed items concerning an independent activity: restlessness, inattention, difficulties concentrating, sensitivity to criticism, unhappy/sad affect, and lability of mood. Regarding the working activities in the group, the most problematic was that she was shy, submissive, frightened, and too distressed to ask for advice. After yearlong AAE, the score of the Conners Scale was reduced (see Tables 1, 2 and 3).

During the AAE, Emily approached the dog before addressing the handler, and the dog became a partner in her every activity. In all the activities were performed in co-operation with the dog. Emily made fewer mistakes in terms of spatial orientation. She made a great effort while drawing pictures linked to the dog’s life and was willing to present her pictures to her classmates without any assistance. The teacher observed significant changes in activity aiming at the development of reading comprehension as well. Emily had clearly shifted her need for physical contact from teachers towards the dog. The dog became for Emily a remarkably close partner which accepted “her and her manifestations of emotional affection without any restriction”, as stated by the teacher. She also mentions, that through the above-described activities, she was losing her anxiety and fear. Moreover, Emily´s pace of work increased, because she wanted to share her results of the efforts with the dog before it will leave the classroom.

Discussion

The present case study showed a positive role in dog-assisted activities in a classroom with a child suffering from ADHD. Both children participating in the study, Tobias (7 years) and Emily (6 years), were diagnosed with ADHD. The severity of their ADHD symptoms rated by their teacher remarkably decreased after one school year. Symptoms were divided into three areas, classroom behavior, group behavior, and authority behavior rated at the beginning and at the end of the school year. Both participants achieved a lower score in all subscales and total scores at the end of the study. The observation of the experimenter and teacher also confirmed the positive effect of the dog in the classroom. Based on these results, we certainly believe that a therapy dog may have a beneficial impact on social behavior in school within the children with ADHD.

The baseline data provided by the teacher about the first participant, Tobias, declared some learning and behavioral difficulties at the beginning of the study. After completing the school year with AAE, the teacher observed an overall improvement of his behavior. This effect was also observed in a study of Schuck et al. (2018) where it was found that the presence of an animal in the classroom could have an improvement in self-confidence, self-esteem, and academic competences. Tobias showed more pro-active participation in classroom activities, and worked with more willingness and enthusiasm. These results were similar to another study (Gee, Griffin, & McCardle, 2017) which concluded that animal-assisted interventions could have a positive impact on children in the classroom. Improving in Tobias´ motor skills, spatial orientation, encouraging in promoting drawing skills, and reading comprehension was also observed. Machová et al. (2018) also reported that the dog could be involved in AAE and help children with special education needs. In this article, the main mentioned factor was the motivation element which was achieved by the presence of the dog in the classroom. The teacher reported more proactive behavior and better collaboration with Tobias.

The second participant, Emily, showed difficulties in attention, lack of concentration, and low self-confidence at the beginning of the study. She was shy and afraid to engage in any classroom activity. After yearlong AAE, comparing the pre and post-evaluation observed by the teacher, Emily looked less anxious, was increased cooperative behavior with classmates, and her pace of work increased. These effects reported also Chitic, Rusu, & Szamoskozi (2012) and Gee et al. (2017), mentioning an increase of social interactions, and reporting an improvement in children´s social skills and prosocial behavior (Schuck et al., 2015).

The presented case study states that AAE was beneficial for both children with ADHD. The participation of a dog in the classroom seems to decrease the severity of various difficulties caused by ADHD symptomatology. Presented findings are not generalizable but they could support additional research in the area of AAE in children diagnosed with ADHD, or children presenting ADHD symptomatic behaviors, which is much needed.

Our results are limited with the absence of a control group or a greater number of observed children. We involved a dog for AAE, so we cannot conclude the general positive effect of any animal. We cannot also exclude the possibility of a positive influence on other factors. However, AAE in both participants was based on their special education needs and focused on the longitudinal observational data (one school year) in the school environment. We believe that this case study will be beneficial for more specialists interacting with children with any disabilities or special educational needs. The ability to focus on learning is one of the most critical domains in children diagnosed with ADHD. This case study demonstrates the possibility to improve this area involving AAE with a dog because his presence can provide emotional support and a trusted companion to the child and that can help remove fears of failure. Moreover, participants completed the school tasks with more enthusiasm and their learning abilities were improved. The implementation of the dog into the educational process seemed to make the classroom environment more pleasant and friendly. The dog appeared to be a form of support or a friend for the children. Maybe, a dog could be a reason to lose the fear of the school and to look forward to school.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates that involving a dog as part of AAE within children with ADHD appears to be a beneficial activity. Children with ADHD exhibited the improvement in concentration, communication with teachers, and co-operation with their classmates after 1 year of AAE with a dog. The teacher and experimenter also observed social and communicational improvements, and remarkably decreased severity of the ADHD symptoms in the classroom, group and authority behavior. We conclude that the AAE in both participants had a positive effect, and we strongly recommend the participation of a dog in AAE to eliminate the ADHD symptoms. However, further research is needed to support our findings. More research and deeper knowledge in this area should be helpful in ADHD therapy.

Change history

02 July 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00737-6

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Baars, S., & Wolf, F. (2011). TiergestützteTherapiebeiKognitions-und Sprachstörungen. Nervenheilkunde, 30(12), 961–966.

Balluerka, N., Muela, A., Amiano, N., & Caldentey, M. A. (2014). Influence of animal-assisted therapy (AAT) on the attachment representations of youth in residential care. Children and Youth Services Review, 42, 103–109.

Bass, M. M., Duchowny, C. A., & Llabre, M. M. (2009). The effect of therapeutic horseback riding on social functioning in children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(9), 1261–1267.

Beetz, A. (2013). Socio-emotional correlates of a schooldog-teacher-team in the classroom. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 886.

Beetz, A., Uvnäs-Moberg, K., Julius, H., & Kotrschal, K. (2012). Psychosocial and psychophysiological effects of human-animal interactions: The possible role of oxytocin. Frontiers in Psychology, 2012(3), 234.

Busch, C., Tucha, L., Talarovicova, A., Fuermaier, A. B. M., Lewis-Evans, B., & Tucha, O. (2016). Animal-assisted interventions for children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychological Reports, 118(1), 292–331.

Chitic, V., Rusu, A. S., & Szamoskozi, S. (2012). The effects of animal assisted therapy on communication and social skills: A meta-analysis. Transylvanian Journal of Psychology, 1, 2–13.

Conners, C. K. (1969). A teacher rating scale for use in drug studies with children. American Journal of Psychiatry, 126(6), 884–888.

Danielson, M., Bitsko, R., Ghandour, R., Holbrook, J., Kogan, M., & Blumberg, S. (2018). Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents 2016. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47, 199–212.

Duric, N., Assmus, J., Gundersen, D., & Elgen, I. (2012). Neurofeedback for the treatment of children and adolescents with ADHD: A randomized and controlled clinical trial using parental reports. BMC Psychiatry, 12, 107.

Epstein, J. N., Langberg, J. M., Lichtenstein, P. K., Altaye, M., Brinkman, W. B., House, K., & Stark, L. J. (2010). Attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder outcomes for children treated in community-based pediatric settings. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 164(2), 160.

Esteves, S. W., & Stokes, T. (2008). Social effects of a dog’s presence on children with disabilities. Anthrozoös, 21(1), 5–15.

Funahashi, A., Gruebler, A., Aoki, T., Kadone, H., & Suzuki, K. (2014). Brief report: The smiles of a child with autism spectrum disorder during an animal-assisted activity may facilitate social positive behaviors—Quantitative analysis with smile-detecting interface. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(3), 685–693.

Gabriels, R. L., Agnew, J. A., Holt, K. D., Shoffner, A., Zhaoxing, P., Ruzzano, S., Clayton, G. H., & Mesibov, G. (2012). Pilot study measuring the effects of therapeutic horseback riding on school-age children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 578–588.

Gabriels, R. L., Pan, Z., Dechant, B., Agnew, J. A., Brim, N., & Mesibov, G. (2015). Randomized controlled trial of therapeutic horseback riding in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(7), 541–549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2015.04.007

Garcia-Gomez, A., Risco, L. M., Rubio, J. C., Guerrero, E., & Garcia-Pena, I. M. (2014). Effects of a program of adapted therapeutic horse-riding in a group of autism spectrum disorder children. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 12(1), 107–128. https://doi.org/10.14204/ejrep.32.13115

Gee, N. R., Griffin, J. A., & McCardle, P. (2017). Human–animal interaction research in school settings: Current knowledge and future directions. Aera Open, 3(3), 2332858417724346.

Gee, N. R., Harris, S. L., & Johnson, K. L. (2007). The role of therapy dogs in speed and accuracy to complete motor skills tasks for preschool children. Anthrozoös, 20(4), 375–386.

Hart, K., Fabiano, G., Evans, S., Manos, M., Hannah, J., & Vujnovic, R. (2017). Elementary and middle school teachers’ self-reported use of positive behavioral supports for children with ADHD: A national survey. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 25(4), 246–256.

Hoffmann, A. O., Lee, A. H., Wertenauer, F., Ricken, R., Jansen, J. J., Gallinat, J., & Lang, U. E. (2009). Dog-assisted intervention significantly reduces anxiety in hospitalized patients with major depression. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 1(3), 145–148.

Horowitz, S. (2010). Animal-assisted therapy for inpatients: Tapping the unique healing power of the human–animal bond. Alternative and Complementary Therapies, 16, 339–343.

Kelly, M., & Cozzolino, C. (2015). Helping at-risk youth overcome trauma and substance abuse through animal-assisted therapy. Contemporary Justice Review, 18, 421–434.

Kotrschal, K., & Ortbauer, B. (2003). Behavioral effects of the presence of a dog in a classroom. Anthrozoös, 16(2), 147–159.

Langberg, J. M., & Becker, S. P. (2012). Does long-term medication use improve the academic outcomes of youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15, 215–233.

Lange, A. M., Cox, J. A., Bernert, D. J., & Jenkins, C. D. (2007). Is counseling going to the dogs? An exploratory study related to the inclusion of an animal in group counseling with adolescents. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 2(2), 17–31.

Leuzinger-Bohleber, M. (2010). Psychoanalytic preventions/ interventions and playing “rough-and-tumble” games: Alternatives to medical treatments of children suffering from ADHD. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 7(4), 332–338.

Machová, K., Kejdanová, P., Bajtlerová, I., Procházková, R., Svobodová, I., & Mezian, K. (2018). Canine-assisted speech therapy for children with communication impairments: A randomized controlled trial. Anthrozoos, 31(5), 587–598.

Martínez, L., Prada, E., Satler, C., Tavares, M. C., & Tomaz, C. (2016). Executive dysfunctions: The role in attention deficit hyperactivity and post-traumatic stress neuropsychiatric disorders. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1230.

Mautone, J., Lefler, E., & Power, T. (2011). Promoting family and school success for children with ADHD: Strengthening relationships while building skills. Theory into Practice, 50, 43–51.

Mrug, S., Molina, B. S. G., Hoza, B., Gerdes, A. C., Hinshaw, S. P., Hechtman, L., & Arnold, L. E. (2012). Peer rejection and friendships in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Contributions to long-term outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 1013–1026.

Murry, F. R., & Allen, M. T. (2012). Positive behavioral impact of reptile-assisted support on the internalizing and externalizing behaviors of female children with emotional disturbance. Anthrozoös, 25(4), 415–425.

O’Haire, M. E. (2013). Animal-assisted intervention for autism spectrum disorder: A systematic literature review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(7), 1606–1622.

O’Haire, M. E., McKenzie, S. J., McCune, S., & Slaughter, V. (2014). Effects of classroom animal-assisted activities on social functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 20, 162–168.

Prothmann, A., Albrecht, K., Dietrich, S., Hornfeck, U., Stieber, S., & Ettrich, C. (2005). Analysis of child—Dog play behavior in child psychiatry. Anthrozoös, 18(1), 43–58.

Schuck, S. E. B., Emmerson, N. A., Fine, A. H., & Lakes, K. D. (2013). Canine-assisted therapy for children with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19(2), 125–137.

Schuck, S. E. B., Emmerson, N. A., Fine, A. H., & Lakes, K. D. (2015). Canine-assisted therapy for children with ADHD: Preliminary findings from the positive assertive cooperative kids study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 19(2), 125–137.

Schuck, S. E. B., Johnson, H. L., Abdullah, M. M., Stehli, A., Fine, A. H., & Lakes, K. D. (2018). The role of animal assisted intervention on improving self-esteem in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 6, 00300.

Susan, D., & Myers, M. (2008). Parental attitudes and involvement in psychopharmacological treatment for ADHD: A conceptual model. International Review of Psychiatry, 20, 135–141.

Swanson, J. M., Baler, R. D., & Volkow, N. D. (2011). Understanding the effects of stimulant medications on cognition in individuals with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A decade of progress. Neuropsychopharmacology, 36, 207–226.

Swartz, L., Le Roux, M., & Swart, E. (2015). Die effekvan’ntroeteldier-ondersteundeleesprogram op woordherkenningsvaardighede van graad 3-kinders: Navorsings-en oorsigartikel. TydskrifvirGeesteswetenskappe, 55(2), 289–303.

Tissen, I., Hergovich, A., & Spiel, C. (2007). School-based social training with and without dogs: Evaluation of their effectiveness. Anthrozoös, 20(4), 365–373.

Wilkes-Gillan, S., Bundy, A., Cordier, R., Lincoln, M., & Chen, Y. W. (2016). A randomized controlled trial of a play-based intervention to improve the social play skills of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). PLoS ONE, 11(8), e0160558.

Wohlfarth, R., Mutschler, B., Beetz, A., Kreuser, F., & Korsten-Reck, U. (2013). Dogs motivate obese children for physical activity: Key elements of a motivational theory of animal-assisted interventions. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 796.

Acknowledgements

This study is a result of the research project Nr. LO1611 with a financial support from the MEYS under the NPU I program. This study was also supported by the Research centre of Charles University, programme Progress = C4 = 8D. Q 06/LF1 = 20. Thanks to Ing. Petra Eretová for the help with manuscript preparation.

Funding

The authors have no funding to report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

In accordance with Springer policy and ethical obligation as researchers, we report that we have no financial and/or business interests that may be affected by the research reported in the enclosed paper.

Research Involving Human and Animal Rights

In our study, an animal is included and the work with it has been authorized and based on the determination of the Ethical Board of the Czech University of Life sciences. This provision is not an attempt and all animal welfare have been followed. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Czech University of Life Sciences Prague

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from parents on behalf of the children enrolled in the study and all children were asked about their preference for the potential presence of the dog during the therapeutic sessions before the enrollment. Both the school management and parents agreed to involve the dog in the class. The dog was involved in teaching in previous years and attended regularly. In this particular year, two students were selected for whom the effect of the dog‘s presence was described and the parents agreed to publish the results.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Juríčková, V., Bozděchová, A., Machová, K. et al. Effect of Animal Assisted Education with a Dog Within Children with ADHD in the Classroom: A Case Study. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 37, 677–684 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00716-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00716-x