Abstract

Adolescence has received particular attention given its unique risk factors, which contribute to the onset and progression of problem behaviour and its development with varying levels of seriousness. Although much adolescent problem behaviour is exploratory, a screening tool is required to identify early problem behaviour, to enable the use of preventive strategies to prevent more serious or persistent behaviour. The problem behaviour frequency scale developed by Farrell et al. (2000) was adapted and validated for this purpose. Method: A sample of Spanish adolescents was obtained comprising 508 subjects, made up of two groups: 318 in the study group (62.7%) and 189 in the comparison group (37.3%). The sample was made up of 62.9% males and 37.1% females, aged between 12 and 18. Various structural models were evaluated and the evidence for reliability, structural validity, sensitivity and specificity was calculated. A cut-off point was established for diagnosis, and differences between case and control groups were identified. Result: The bifactor model obtained the best fit, affirming the hypothesis on unidimensionality of PBFS and supporting the concept of problem behaviour syndrome. Discussion: Results suggest that PBFS is a reliable and valid instrument for identifying problem behaviour

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Social Work has acquired conceptual approaches and theoretical models that have directed the professional intervention of the social worker in order to effectively address the plurality of social problems and demands that make up this scope of action (Botija, 2014). The preventive approach in Social Work has generated a range of opportunities, initiatives and challenges in the social intervention process that have focused on avoiding the emergence of social problems or needs. In addition, it has provided new keys for the interpretation of the social context that improves decision-making and the generation of resources and development of specific policies. Preventive intervention with adolescents seeks to modify future conditions through education and promotion.

Adolescence is a natural stage of life that occurs between childhood and adult independence. Its onset at the beginning of puberty is characterized by biological and environmental changes that will continue throughout the period of adolescence (Blakemore, Burnett & Dahl 2010). There are profound alterations in hormonal levels during this period, with the resulting cognitive and physical changes, impulses, emotional control, motivations, decision-making and social life (Gil-Fenoy, García-García, Carmona-Samper & Ortega-Campos, 2018; Prensky, 2001; Steinberg, 2008). In recent decades, adolescence has changed rapidly, and it has become a longer stage of life. Puberty now begins at a younger age and it takes longer to reach mature social roles (Maes & Lievens, 2003).

Scientific literature recognizes the basic key task of adolescence as the construction of self-identity, distinct from the adults who have previously acted as the basic reference point until that time (Erikson, 1968). There is a general concern from adults with regard to the adolescent identity (Linders, 2016), which is perceived as fragile and vulnerable to the broader social environment: popular culture and the rise of information and communication technologies (Prensky, 2001; 2014). This concern comes about because:

-

Firstly, adolescents develop their own lifestyles in which they acquire new tastes (regarding clothing and the music they listen to, or their choices of new friends), new habits (spending time with electronic devices), and a reluctance to inform their parents or guardians of where they are going or what they are doing (Danesi, 2003).

-

Secondly, Socio-Cognitive processes, health strategies, and normative and maladaptive patterns are learned during adolescence (Maes & Lievens, 2003). These are all important aspects because they shape the individual’s life pathways.

-

Thirdly, the challenges that each generation of adolescents faces and the way in which they negotiate this stage of their lives will have a powerful effect on their future and on the economic and social prospects of their countries (Sawyer et al., 2012).

-

Lastly, there is strong evidence that risk-taking is higher among adolescents than at other stages of life (Arnett, 1992; 2000; Steinberg, 2008; Duell et al., 2018). This risk-taking may contribute to the development of socially acceptable and constructive behaviour or to the onset and progression of problem behaviour (Duell & Steinberg, 2018).

In this context of adult concern for adolescents and the dangers that they face, and in which adolescents focus their attention on social stimuli in the full flush of cognitive and affective development (Steinberg, 2008), some of them will develop problem behaviour that is highly predictive of later anti-social behaviour (Shaykhi, Ghayour-Minaie & Toumbourou, 2018). Problem behaviour can be understood as the outcome of complex interactions between risk and protective factors (Prinzie & Dekovic, 2008; Prinzie, Hoeve & Stams, 2008), which have impacts depending on their influence across the individual, family and community ecological domains (Zimmerman, 2013; Hawkins, Catalano & Arthur, 2002; Hawkins, Catalano & Miller, 1992). Risk factors are prospective predictors of the probability of an individual or group being involved in adverse outcomes. Their presence contributes to the onset and progression of various forms of behaviour that, with various levels of risk, tend to coexist (Jessor, 1991). This coexistence has found repeated support in literature, in the form of studies linking behaviour (such as drug use) with criminal or violent conduct (Reynolds, Collado-Rodriguez, MacPherson & Lejuez, 2013; Farrell et al., 2000; Farrell, Sullivan, Goncy & Le, 2015; Farrell, Thompson, Mehari, Sullivan & Goncy, 2018; Jessor, 1991, 2014; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Corchado, 2012). These links have an underlying structure that brings together “a set of behaviors believed to have a common cause or basis” (English & English, 1958), which can be explained using a single factor that Donovan and Jessor (1985) described as problem behaviour syndrome.

Problem behaviour arises and progresses in a pattern of multiple origin. It can be assessed based on frequency and seriousness and shapes the adolescent’s developmental trajectory (Corchado, 2012). The higher the quantity of problem behaviours displayed by the adolescent, the greater the concern as to their wellbeing and the higher the risk of morbidity or mortality. Farrell, Kung, White & Valois (2000) designed PBFS to research the structure of adolescent problem behaviour using a self-reporting measurement tool. The results of their study show support for the notion of a general syndrome of problem behaviour (Farrell, et al, 2000).

Aims and Hypothesis

The aim of this study is to convert the problem behaviour frequency scale (PBFS) developed by Farrell et al. (2000) into a brief tool that is capable of identifying adolescents exhibiting problem behaviour.

PBFS was selected since, although there are scales that evaluate the risks arising from specific behaviours such as violence, sexual conduct or substance use (Wångby-Lundh, Klingstedt, Bergman & Ferrer-Wreder, 2018), scales to assess problem behaviour as an organized range of inter-related behaviours (Jessor, 1991; Donovan & Jessor, 1985) were not found. The scale conforms to Jessor’s theory of problem behaviour (2014), by which, it is a challenge to appropriately identify risk within an adolescent ecology in which young people learn new patterns of behaviour and simultaneously experience them (Jessor 1991). Detecting cases of risk will help to prevent transitions to more serious behaviour or the development of persistent problem behaviors (Bolland, 2003). Choosing this scale has made it possible to evaluate the structure of problem behaviour through the analysis of competing models.

The general aim was to validate the PBFS developed by Farrell et al. (2000) among Spanish adolescents who had exhibited this kind of problem behaviour. The hypothesis on unidimensionality of PBFS was tested for this purpose.

Method

Participants

A sample was obtained comprising 508 subjects, made up of two groups: 318 in the study group (62.7%) and 189 in the comparison group (37.3%). The sample was made up of 62.9% males and 37.1% females, with an average age of 16 (SD = 2.86; minimum 12 and maximum 18). The higher percentage of male participants is due to their greater presence among the population from which the selected groups were taken, which hinders the classification of results based on subject sex (INE, 2017; DGPNSG, 2018).

The study group is made up of minors who showed risky behaviors and was subdivided into three subgroups depending on the risk situation and the characteristics of the individuals:

(1) adolescents placed in care centres as a result of a situation of neglect, generally due to abuse or negligence suffered in their family environment and tending to generate problem behaviour (González, Fernández & Secades, 2004), (n = 189, 37.2%); (2) adolescents subject to court orders in closed centres (n = 104, 20.5%); and (3) adolescents undergoing treatment for drug abuse in public and private centres (n = 25, 4.9%).

These subdivisions attempt to study factors that are associated with belonging to different risk groups, interpreting the differences as a reflection of some critical aspect or as associated factors of risk behaviour. The members of the comparison group were selected based on similarity to the other groups, applying a strategy similar to the case–control design in epidemiological studies. The inclusion criteria in the comparison group were age, sex and cohabitation with family of origin (n = 190, 37.4%).

The adolescents of the comparison group did not present problems derived from risky behavior. For this purpose, participants with the necessary profile were selected in secondary schools, training and employment centers in the same community of origin of the cases (see Table 1). An informed consent form describing the terms of the research to the guardians or parents of the minors was available. In the case of minors under guardianship, consent was granted by the responsible entity.

Design

A transversal comparative non-experimental study was carried out. This design corresponds to the associative strategy (Ato, López-García & Benavente, 2013) to explore the comparison of the groups of participants that are evaluated at a given time, examining the differences between them. Comparative studies are essentially non-experimental studies.

Procedure

The individuals in the study group were contacted through collaboration agreements between Complutense University of Madrid and each of the institutions with responsibility for the care and custody of the participants. Those with responsibility for each entity determined the total number of subjects selected from each group. The survey was applied collectively in all cases, with the presence of the researcher. Group size ranged between 5 and 25 depending on the centre, except in the group of minors undergoing treatment for drug use, where the survey was applied individually. The researcher provided the instructions, answering questions that arose in relation to the application of the survey. An informative letter was produced describing the terms of the research, which included the obtaining of informed consent from the minors’ parents or guardians. In the case of minors in care, the responsible entity gave the consent.

Measurement Variables and Instruments

The sociodemographic variables were sex, age and membership of relevant group of interest. The PBFS was initially developed by Farrell, Kung, White & Valois (2000). PBFS was constructed with 26 items (see Table 2) divided into four subscales:

Six items evaluate behaviour in terms of consumption of gateway drugs: tobacco, fermented and distilled alcoholic drinks, and marijuana (Wall, et al., 2018). The classic theory of Kandel (1975) remains valid, although the evolutionary pattern of drug use is not immutable (Mayet, Legleye, Falissard & Chau, 2012). The beginning of drug use is not constant across all contexts and cultures, and sequential changes are related more to the age at which use begins and to a greater degree of exposure to the substance than to the development of dependence. Cannabis is the most commonly used illegal drug in the majority of cases, preceded by the consumption of alcohol and tobacco (Wall et al., 2018).

The seven items for physical aggression were based on the National Youth Risk Behaviour Survey developed by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Kolbe, Kann & Collins, 1993). This survey has been conducted every 2 years since 1991 (Kann et al., 2018).

Seven items were also included in the scale to study non-physical aggression. Some of these were based on observations made of school students and in focus groups studying interpersonal problems (Farrell et al., 2000), while others such as “spread a rumour” and “excluded someone” were inspired by the relational aggression scale developed by Crick & Grotpeter (1995). This scale is commonly used to evaluate behaviour involving exclusion or manipulation that takes place in the context of peer relationships (Aizpitarte, Atherton & Robins, 2017).

The final six items refer to behaviour such as school absenteeism, theft, insults and vandalism, and were based on the attitude toward deviance scale (Jessor & Jessor, 1977, 2014).

The adolescents were asked to state how frequently they had engaged in each behaviour during the previous 30 days. The responses were based on a six-point Likert-type scale: 1 (never), 2 (1–2 times), 3 (3–5 times), 4 (6–9 times), 5 (10–19 times) and 6 (20 or more times).

An inverse or back translation was performed to maintain conceptual equivalence between the original version, produced in English, and the Spanish-language version.

Data Analysis

Missing values were imputed with the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm, introducing adolescents’ sex, age and type of centre in addition to the variables from the scale.

The factorial structure of the models presented by Farrell et al. (2000) was reviewed. To examine unidimensionality of PBFS, a bifactor analysis was carried out that showed how the problem behaviour manifested via a general factor that explains a large portion of variance (Rodríguez, Reise & Haviland, 2016).

The internal consistency of PBFS was determined by calculating the Cronbach’s alpha and ordinal coefficient alpha (Zumbo, Gadermann & Zeisser, 2007).

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were used to establish the cut-off point for the interpretation of the scores obtained and to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of the general factor and of the three specific factors.

To find the existence of significant differences among the average scores for each scale item and the problem behaviour and comparison groups, a T-test was performed and the eta-squared (η2) index was calculated to measure effect size.

These analyses were carried out using the following sofware: the IBM SPSS v.25 programme for the descriptive data analysis, calculation of Cronbach’s alpha, analysis of the ROC curve and T-test and effect size; MPlus v.7 for confirmatory factorial analyses and to determine the unidimensionality of PBFS; and the Excel application to calculate the ordinal coefficient alpha and fit indices for the bifactor model (Domínguez-Lara, 2012, Domínguez-Lara & Rodríguez, 2017).

Results

Factor Analysis

The factorial structure of the models proposed by Farrell et al. (2000) was reviewed, with similar results obtained. Four models were tested (see Table 3). The single-factor model did not provide adequate fit indices. The three- and four-factor models produced the same acceptable fit indices. The change in \(\chi 2\) between them showed the superiority of the four-factor model, but the high correlation between the factors of physical and non-physical aggression (r = 0.95) showed that all aggression items formed part of the same underlying construct, and as in the study performed by Farrell et al. (2000), the choice of the three-factor model was affirmed.

The fourth model, made up of three first-order factors supporting one general second-order factor labelled problem behaviour, was equivalent to the three-factor model.

Dimensionality of PBFS

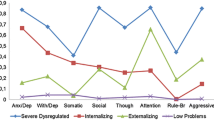

To evaluate the unidimensionality of PBFS, a bifactor model was proposed as an alternative to the unidimensional, correlated and second-order representations used by Farrell et al. (2000). The bifactor model (Fig. 1) is a latent structure where each element is loaded into a general factor that measures a single latent trait: problem behaviour. Three orthogonal group factors are also specified, controlling variance due to these additional factors.

Table 4 shows saturations and R2 for each element under the unidimensional solution.

New indices were obtained deriving from the fit of a bifactor model, with a general factor and three factors independent from one another and from the general factor. These indices provide a favourable view on the unidimensionality of PBFS (Table 5). The HH.FG of the problem behaviour general factor evaluates the reliability of the construct. If this index reaches values of ≥ 0.70, this shows that the latent variable is perfectly defined by its indicators and will be stable across all studies (Rodriguez, Reise & Haviland, 2016). The high value obtained for the ωH coefficient permits a global explanation of the scores for the scale (Reise, 2012), with 86% of total variance explained by a single construct. The particular risk domains of drug use and violence can be considered robust factors along with the general factor, due to the scores attained in the HH.S1 and HH.S3 indices. Adequate values were obtained for the delinquency factor (see Table 5).

The chi-squared difference test showed that the bifactor model is a statistically significant improvement in comparison with the second-order model (see Table 3).

Reliability of PBFS

The values show high reliability across all scales in all cases. Higher values are obtained for the ordinal estimations (see Table 6).

Sensitivity and Specificity

The estimated value of the under-curve area for PBFS was 86% (ABC = 0.86; p ≤ 0.00), meaning the scale is adequate to distinguish cases of problem behaviour from those that do not involve this kind of behaviour (see Fig. 2). The practical use of the scale requires the choosing of an appropriate cut-off point that represents the best balance between sensitivity and specificity of each of the scores. The cut-off point offering the best balance in this respect is that corresponding to the score 49 (sensitivity = 0.84; specificity = 0.79).

The values for the subscales were:

-

Drugs: the value of the under-curve area was 79% (ABC = 0.79; p ≤ 0.00) and the cut-off point corresponded to the score 13 (sensitivity = 0.87; specificity = 0.71).

-

Delinquency: 74% (ABC = 0.74; p ≤ 0.00), with the cut-off point at score 8 (sensitivity = 0.73; specificity = 0.67).

-

Violence: 78% (ABC = 0.78; p ≤ 0.00), with the cut-off point at score 22 (sensitivity = 0.77; specificity = 0.67).

Capacity of the PBFS to Distinguish Between Groups

Table 7 shows the results obtained. The most important items for describing problem behaviour form part of the two robust factors: drug use (smoked cigarettes, drank beer, drank spirits and used marijuana); and violence (put someone down, picked on someone and insulted someone’s family). The T-test shows significant differences across all items except for ‘excluded someone’, ‘picked on someone’ and ‘cheated on a test’. The scores obtained for the η2 indices also show a large effect across all items except for ‘excluded someone’ and ‘cheated on a test’, with a medium effect, and ‘picked on someone’, with a small effect.

Discussion

The results have shown that PBFS replicates the factorial structure found by Farrell et al. (2000), although the advantages of the bifactor model over the second-order model (Chen, West & Sousa, 2006; Chen, Bai, Lee & Jing, 2015; Chen & Zhang, 2018) have permitted a direct exploration of the unidimensionality of the PBFS, examining the extent to which the elements reflect an objective common trait or a unitary construct (Reise, Moore & Haviland, 2010; Reise, Kim, Mansolf & Widaman, 2016), and have provided support for the notion of problem behaviour syndrome in adolescence (Farrell et al, 2000). PBFS is a brief measure with adequate reliability, validity, sensitivity and specificity indices and has shown to be appropriate for its use among the adolescent population, offering highly relevant information on the evaluated subject and identifying well-differentiated profiles that distinguish appropriately between subjects with proven problem behaviour and those who formed part of the comparison group.

Educating and supporting adolescents with regard to the difficulties that they may face in completing the tasks inherent to this stage of development requires the availability of a quick and simple screening instrument, which can be applied by the professionals working in the contexts where adolescent life takes place. PBFS can be easily administered as a self-reporting measure at educational centres, school guidance centres, community and health centres and other social services agencies. In this regard, PBFS is an analytical strategy that examines adolescent behaviour as a whole (Borodovsky, Krueger, Agrawal, & Grucza, 2019), and an important resource with implications for prevention and intervention, as it identifies at-risk adolescents in a rapid and precise manner and can therefore facilitate actions aimed at promoting pro-social behaviour and healthy lifestyles (Catalano, Berglund, Ryan, Lonczak, & Hawkins, 2004).

Prevention as a discipline has transformed the treatment model that continues to be the most widely used approach in the world to deal with behaviour problems (Patel et al., 2007). Evidence-based prevention generates effective and profitable programming formulas through the development of programs and the generation (provision) of appropriate resources (Stone, Becker, Huber & Catalano, 2012).

Implications for Social Work Practice and Policy

Social Work must propose an approach that includes more prevention and early intervention strategies, incorporating a preventive and sustainable effect into protection systems that strengthens adolescents’ ability to react to life risks (Jones & Truell, 2012).

Guaranteeing access to social resources and progress and improvement in the adolescents’ assets (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005) will reduce the personal, family and social costs that would otherwise arise. By avoiding the negative aspects of risk-related pathways, one can promote the proper development of the adolescent into a healthy adult, improve relationships with the significant people in their environment (family members, peers and teachers) (Díaz-Aguado, Martínez-Arias & Ordóñez, 2013), and safeguard their right to protection and prevention as responsible members of the society in which they participate and are therefore holders of rights and duties (Spanish Law 26/2015, July 28).

Early life intervention may be warranted for favorable lifelong health (Akasaki, Ploubidis, Dodgeon, & Bonell, 2019). Social Work must carry out more research in the prevention field in order to respond to the need to improve the procedures and tools to detect risk behaviour in the adolescent population, but this should not be an excuse for the development of social policies and prevention.

Limitations

It would be useful for future research to verify the usefulness of PBFS in evaluating the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing problem behaviour. Further work will be necessary to evaluate the extent to which the results can be generalized for other samples of adolescents, via studies that have an improved procedure for obtaining samples and extend it to other regions in Spain.

PBFS will become more effective insofar as it becomes adapted to adolescent culture, including elements relating to information technologies (Farrell, Thompson, Mehari, Sullivan & Goncy, 2018).

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to validate and adapt the PBFS developed by Farrell et al. (2000) for a sample of Spanish adolescents, in order to produce a screening instrument capable of identifying those adolescents with problem behaviour. PBFS complies with the necessary attributes that will allow the generation of confidence to ensure that the scores obtained from the domains of the scale it evaluates are reliable. PBFS will provide valuable information on the situation of minors at risk. Greater knowledge and detection of risk behaviors will make it possible to generate resources and procedures for the provision of services appropriate to the specific characteristics of this population that facilitate their promotion and development.

References

Aizpitarte, A., Atherton, O. E., & Robins, R. W. (2017). The co-development of relational aggression and disruptive behavior symptoms from late childhood through adolescence. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(5), 866–873. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617708231.

Akasaki, M., Ploubidis, G. B., Dodgeon, B., & Bonell, C. P. (2019). The clustering of risk behaviours in adolescence and health consequences in middle age. Journal of Adolescence, 77, 188–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.11.003.

Arnett, J. (1992). Reckless behavior in adolescence: A developmental perspective. Developmental Review, 12, 339–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(92)90013-R.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

Ato, M., López-García, J. J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology, 29(3), 1038–1059. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511.

Blakemore, S. J., Burnett, S., & Dahl, R. E. (2010). The role of puberty in the developing adolescent brain. Human brain mapping, 31(6), 926–933. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.21052.

Bolland, J. M. (2003). Hopelessness and risk behaviour among adolescents living in high-poverty inner-city neighbourhoods. Journal of adolescence, 26(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00136-7.

Borodovsky, J. T., Krueger, R. F., Agrawal, A., & Grucza, R. A. (2019). A decline in propensity toward risk behaviors among U.S. adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(6), 745–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.07.001.

Botija Yagüe, M. M. (2014). Eclecticismo en la intervención con adolescentes en conflicto con la ley. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 27(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_CUTS.2014.v27.n1.40178.

Catalano, R. F., Berglund, M. L., Ryan, J. A., Lonczak, H. S., & Hawkins, J. D. (2004). Positive youth development in the United States: Research findings on evaluations of positive youth development programs. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 98–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203260102.

Chen, F. F. and Zhang, Z. (2018). Bifactor Models in Psychometric Test Development. In P. Irwing, T. Booth and D. J. Hughes (Eds) The Wiley Handbook of Psychometric Testing: A Multidisciplinary Reference on Survey, Scale and Test Development. Vol 1, (pp 374–373). NJ. John Wiley Blackwell.

Chen, F. F., Bai, L., Lee, J. M., & Jing, Y. (2015). Culture and the Structure of Affect: A Bifactor Modeling Approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(5), 1801–1824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9671-3.

Chen, F. F., West, S. G., & Sousa, K. H. (2006). A comparison of bifactor and second-order models of quality of life. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 41(2), 189–225. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr4102_5.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66, 710–722.

Corchado, A.I. (2012). Conductas de riesgo en la adolescencia (Doctoral dissertation, Complutense University of Madrid).

Danesi, M. (2003). My son is an alien: A cultural portrait of today’s youth. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Delegación del Gobierno para el Plan Nacional sobre Drogas (DGPNSG), (2018). Encuesta estatal sobre uso de drogas (ESTUDES) 2016/2017. Madrid: Secretaría de Estado de Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. Retrieved from https://www.pnsd.msssi.gob.es/

Díaz-Aguado, M.J., Martínez-Arias, R., & Ordóñez, A. (2013). Prevenir la drogodependencia en adolescentes y mejorar la convivencia desde una perspectiva escolar ecológica. Revista de Educación, nº extraordinario, 338–362. https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2013-EXT-251

Dominguez-Lara, S. (2012). Propuesta para el cálculo del Alfa Ordinal y Theta de Armor. Revista de Investigación en Psicología, 15(1), 213–217.

Donovan, J. E., & Jessor, R. (1985). Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(6), 890–904. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.6.890.

Duell, N., & Steinberg, L. (2018). Positive Risk Taking in Adolescence. Child Development Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12310.

Duell, N., Steinberg, L., Icenogle, G., Chein, J., Chaudhary, N., Di Giunta, L., … & Pastorelli, C. (2018). Age patterns in risk taking across the world. Journal of youth and adolescence, 47(5), 1052–1072. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0752.

English, H. B., & English, A. C. (1958). A comprehensive dictionary of psychological and psychoanalytical terms: A guide to usage. London: Longman.

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. New York: W. W.Norton Company.

Farrell, A. D., Kung, E. M., White, K. S., & Valois, R. F. (2000). The structure of self-reported aggression, drug use, and delinquent behaviors during early adolescence. Journal of clinical Child Psychology, 29(2), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424jccp2902_13.

Farrell, A. D., Sullivan, T. N., Goncy, E. A., & Le, A.-T. (2015). Assessment of adolescents’ victimization, aggression, and problem behaviors: Evaluation of the Problem Behavior Frequency Scale. Psychological Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000225.

Farrell, A. D., Thompson, E. L., Mehari, K. R., Sullivan, T. N., & Goncy, E. A. (2018). Assessment of in-person and cyber aggression and victimization, substance use, and delinquent behavior during early adolescence. Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191118792089.

Fergus, S., & Zimmerman, M. A. (2005). Adolescent Resilience: A framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annual Review of Public Health, 26, 399–419.

Gil-Fenoy, M. J., García-García, J., Carmona-Samper, E., & Ortega-Campos, E. (2018). Conducta antisocial y funciones ejecutivas de jóvenes infractores. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 23(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2017.09.001.

González, A., Fernández, J. R., & Secades, R. (2004). Guía para la detección e intervención temprana con menores en riesgo. Gijón: Colegio de Psicólogos del Principado de Asturias.

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., & Arthur, M. W. (2002). Promoting science-based prevention in communities. Addictive Behaviors, 27, 951–976.

Hawkins, J. D., Catalano, R. F., & Miller, J. Y. (1992). Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: Implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological Bulleting, 112, 64–105.

INE. (2017). INEbase. Seguridad y Justicia Estadística de condenados: Menores. Madrid. Retrieved from: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176795&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735573206

Jessor, R. (1991). Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12, 597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/1054-139X(91)90007-K.

Jessor, R., & Jessor, S.L. (1977). Problem behavior and psychosocial development: A longitudinal study of youth. New York: Academic. https://lib.ugent.be/catalog/rug01:000002543

Jessor, R. (2014). Problem Behavior Theory: A half century of research on adolescent behavior and development. In R. M. Lerner, A. C. Petersen, R. K. Silbereisen, & J. Brooks-Gunn (Eds.), The developmental science of adolescence: History through autobiography (pp. 239–256). New York: Psychology Press.

Jones, D. N., & Truell, R. (2012). The global agenda for social work and social development: A place to link together and be effective in a globalized world. International Social Work, 55(4), 454–472.

Kandel, D. B. (1975). Stages of adolescent involvement in drug use. Science, 190, 912–914. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1188374.

Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., … & Ethier, K. A. (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance - United States, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1–114. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1.

Kolbe, L. D., Kann, L., & Collins, J. L. (1993). Overview of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. Public Health Reports, 108(Suppl. 1), 2–10.

Linders, A. (2016). Deconstructing Adolescence. In A. L. Cherry, V. Baltag, & M. E. Dillon (Eds.), International handbook on adolescent health and development. The Public Health Response. Cham: Springer.

Maes, L., & Lievens, J. (2003). Can the school make a difference? A multilevel analysis of adolescent risk and health behaviour. Social Science & Medicine, 56(3), 517–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00052-7.

Mayet, A., Legleye, S., Falissard, B., & Chau, N. (2012). Cannabis use stages as predictors of subsequent initiation with other illicit drugs among French adolescents: Use of a multi-state model. Addictive behaviors, 37(2), 160–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.012.

Patel, V., Araya, R., Chatterjee, S., Chisholm, D., Cohen, A., De Silva, M., … & Van Ommeren, M. (2007). Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet, 370(9591), 991–1005. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital game bases learning. New York: McGrawHill.

Prinzie, P., Hoeve, M. & Stams, G.J.J.M. (2008). Family processes parent and child personality characteristics. In R. Loeber. H. M. Koot. N. W. Slot. P. H. Van der Laan. & M. Hoeve (eds.) Tomorrow’s criminals: The development of child delinquency and effective interventions (pp. 91–102). Hampshire. England: Ashgate.

Prinzie, P., & Dekoviç, M. (2008). Continuity and change of childhood personality characteristics through the lens of teachers. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.002.

Reise, S. P., Moore, T. M., & Haviland, M. G. (2010). Bifactor models and rotations: Exploring the extent to which multidimensional data yield univocal scale scores. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(6), 544–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.496477.

Reise, S. P. (2012). The rediscovery of bifactor measurement models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 47(5), 667–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2012.715555.

Reise, S. P., Kim, D. S., Mansolf, M., & Widaman, K. F. (2016). Is the bifactor model a better model or is it just better at modeling implausible responses? Application of iteratively reweighted least squares to the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Multivariate behavioral research, 51(6), 818–838.

Reynolds, E. K., Collado-Rodriguez, A., MacPherson, L., & Lejuez, C. (2013). Impulsivity, disinhibition, and risk taking in addiction. Principles of Addiction (pp. 203–212). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-398336-7.00021-8

Rodriguez, A., Reise, S. P., & Haviland, M. G. (2016). Evaluating bifactor models: Calculating and interpreting statistical indices. Psychological methods, 21(2), 137. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702616657069.

Sawyer, S. M., Afifi, R. A., Bearinger, L. H., Blakemore, S. J., Dick, B., Ezeh, A. C., & Patton, G. C. (2012). Adolescence: A foundation for future health. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1630–1640. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60072-5.

Shaykhi, F., Ghayour-Minaie, M., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2018). Impact of the Resilient Families intervention on adolescent antisocial behavior: 14-month follow-up within a randomized trial. Children and Youth Services Review, 93, 484–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.08.021.

Steinberg, L. (2008). A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review, 28, 78–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002.

Stone, A. L., Becker, L. G., Huber, A. M., & Catalano, R. F. (2012). Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addictive behaviors, 37(7), 747–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.02.014.

Thiel-Stern, S. (2014). From the dance hall to Facebooksst: Teen girls, mass media, and moral panic in the United States, 1905–2010. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Zimmerman, M. A. (2013). Resiliency theory A strengths-based approach to research and practice for adolescent health. Health Education & Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198113493782.

Zumbo, B. D., Gadermann, A. M., & Zeisser, C. (2007). Ordinal versions of coefficients alpha and theta for Likert rating scales. Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods. https://doi.org/10.22237/jmasm/1177992180.

Wall, M., Cheslack-Postava, K., Hu, M. C., Feng, T., Griesler, P., & Kandel, D. B. (2018). Nonmedical prescription opioids and pathways of drug involvement in the US: Generational differences. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 182, 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.10.013.

Wångby-Lundh, M., Klingstedt, M. L., Bergman, L. B., & Ferrer-Wreder, L. (2018). Swedish adolescent girls in special residential treatment: A person-oriented approach to the identification of problem syndromes. Nordic Psychology, 70(1), 17–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2017.1323663.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corchado, A.I., Martínez-Arias, R. Screening of Problem Behavior Syndrome in Adolescents. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 39, 107–117 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00699-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00699-9