Abstract

Empowerment is a higher order multilevel framework used to evaluate individuals, groups, organizations, and communities as they engage in the practice and execution of the participatory process. The cognitive component of psychological empowerment (PE) has been examined through the Cognitive Empowerment Scale (CES); however, this scale has yet to be specifically tested to assess differences between African American/Black and Hispanic/Latinx urban youth. This study tested the factor structure of the CES using Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) through AMOS Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Software among a sample of African American/Black and Hispanic/Latinx urban youth (N =383). Analyses also assessed the association intrapersonal PE and psychological sense of community (SOC) had with CE. Results support the multidimensionality of the CES as a measure of cognitive PE, with no significant differences noted between groups. Findings also contribute to the field of social work and encourage the promotion of youth-work that enables these young people to foster a critical read of their social world in order to build a path toward engaging in social change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Youth movements over the last decade have highlighted that young people are not passive recipients of change, but are active agents of change that contest, resist, and rework social conditions (Christens, Byrd, Peterson, & Lardier, 2018; Ginwright, 2015; Kirshner, 2015). More poignantly, youth of color are actively engaged in significant social movements throughout the United States, whether we consider the #BlackLivesMatter movement or DREAM teams. These radical socio-political projects provide evidence that youth are willing to work toward change that impacts their well-being, health, and status as a citizen. Moreover, youth of color are willing to challenge power, reject the existing order, and join collectively to redirect social conditions, policies, and beliefs (Kwon, 2013). While more recently drawing a critical eye to youth, and specifically youth of color, research has glanced over the empowerment of these young people (Christens et al., 2018; Kwon, 2013; Lardier Jr., 2019). Further, these studies have not fully examined the ways in which to effectively understand and measure their perceived ability to recognize power and enact change on issues that impact the collective wellbeing of their group and community (Christens et al., 2018; Kwon, 2013; Lardier Jr., 2019).

Empowerment Theory and Psychological Empowerment

Empowerment has been designated as a higher order multilevel framework to understand and evaluate individuals, groups, organizations, and communities as they engage in the practice of participatory change (Rappaport, 1987; Rappaport, Rappaport, Swift, & Hess, 1984). Empowerment has been defined as an interdependent process at the individual (psychological), organizational, and community-levels that focuses on how individuals (and groups) obtain resources, gain control, and critically assess their environmental circumstances that impact their lives (Speer & Hughey, 1995; Zimmerman, 2000). The nomological understanding of empowerment processes also indicates that it is complex and takes different forms, for different people, groups, and communities (Zimmerman, 2000). However, there is still limited understanding of empowerment and empowerment-related constructs within and among varying social contexts and groups (Lardier Jr., Reid, & Garcia‐Reid, 2018a; Peterson, 2014).

The psychological empowerment (PE) component of empowerment has received the most attention in empowerment theory and research (Lardier Jr et al., 2018a; Peterson, 2014). Conceptualized as a psychosocial variable imbedded within relational processes (Christens, 2012; Peterson, 2014), PE is theorized to include intrapersonal, interactional, and behavioral components (Zimmerman, 2000). The intrapersonal or emotional component of PE includes perceptions of socio-political control and self-efficacy, particularly in the sociopolitical sphere (Zimmerman, 1995, 2000). The interactional or cognitive component of PE involves a critical understanding of one’s social environment and has been largely theorized through community organizing and community members understanding the source, nature, and instruments of social power (Zimmerman, 1995, 2000). Last, the behavioral component of PE has been defined through participating and coping behaviors that focus broadly on social and community change (Zimmerman, 1995, 2000).

The intrapersonal component of PE has received the most attention, however, the interactional or cognitive component of PE needs further consideration among social, political, economic minority groups, particularly youth of color (Lardier Jr., 2018, 2019; Lardier Jr et al., 2018a; Peterson, 2014). Those studies that have examined the cognitive component of PE have done so through the Cognitive Empowerment Scale (CES), which examines the source, nature, and instruments of social power (Christens, Collura, & Tahir, 2013; Peterson, Hamme Peterson, & Speer, 2002; Rodrigues, Menezes, & Ferreira, 2018; Speer & Peterson, 2000; Speer, Peterson, Christens, & Reid, 2019). Cognitive PE has been examined as a process of empowerment (Christens et al., 2013; Rodrigues et al., 2018) and in relation to critical consciousness (Christens et al., 2013). Minimal research has studied cognitive PE as an outcome and more importantly, limited scholarship has examined the factor structure of the CES among youth (Lardier Jr., 2019; Rodrigues et al., 2018). Furthermore, limited research has studied whether the factor structure of the current iteration of the CES measures similarly among African American/Black and Hispanic/Latinx youth (Lardier Jr et al., 2018a).

Cognitive PE is defined as critical awareness or a critical understanding of the sociopolitical system that allows individuals to act strategically and effectively within them (Perkins & Zimmerman, 1995; Zimmerman, 1995). A critical understanding of the social system may lead an individual to be more effective, strategic, and take critical action (Speer, 2000; Speer & Peterson, 2000). Through this critical awareness, individuals can engage in social change within their contexts. Scholars have outlined three dimensions within the cognitive PE construct:

-

(1)

knowledge of the source of power, which is defined as the understanding that social and systemic change occurs among the collective action, rather than individual action (Speer & Hughey, 1995);

-

(2)

the nature of power, is characterized as that knowledge that raises awareness of power differentials (Gutiérrez, 1995) and the how social power operates within the socio political realm (Speer, 2000; Speer & Peterson, 2000). This knowledge raises awareness and readiness to deal with conflict as part of the community change processes (Speer, 2000);

-

(3)

the instruments of social power involves the understanding the three instruments through which power is exercised: (i) the ability to reward and punish, (ii) gatekeeping and agenda-setting capabilities, and (iii) the ability to shape ideology (Speer, 2000; Speer & Peterson, 2000).

Those studies that have tested the factor structure of the cognitive PE scale have supported that this measure is a multidimensional scale: (1) knowledge of the source of social power; (2) knowledge of the nature of social power; and (3) knowledge of the instruments of social power (Eisman et al., 2016; Rodrigues et al., 2018; Speer, 2000). Furthermore, cognitive PE has been associated with critical consciousness (Christens et al., 2018; Speer et al., 2019; Watts, Diemer, & Voight, 2011; Watts & Hipolito-Delgado, 2015).

Critical Consciousness: A Conceptually Related Construct of Cognitive Psychological Empowerment

Cognitive PE and critical consciousness share some conceptual overlap (Christens et al., 2018). Critical consciousness, more specifically, is theorized as a multicomponent construct with both cognitive and emotional or intrapersonal PE (Watts et al., 2011). Several studies have discussed the cognitive processes of critical consciousness and that through critical social analyses, a component of cognitive PE, individuals can define, expand, and refine sociopolitical points (Christens et al., 2018; Diemer, Rapa, Park, & Perry, 2017; Hope & Jagers, 2014). Critical social analyses concerns engaging in a deeper understanding between marginalization and sociopolitical circumstances (Watts & Hipolito-Delgado, 2015), with identity and membership with an oppressed social group further augmenting this awareness (Watts et al., 2011). Recently, Christens et al. (2018) identified while examining the association between cognitive and intrapersonal PE that youth of color who were more critical and hopeful, experienced not only greater mental well-being, but engaged in more civic activities, had a greater sense of community, and had more of a social justice orientation. Despite the conceptual overlap between critical consciousness and cognitive PE, the former tends to be more substantively focused on social power dynamics, whereas the latter concerns the cognitive dimension.

As a conceptually-related construct, measures of critical consciousness tailored to youth have been examined through aspects of sociopolitical awareness and the ability to engage in social change as a means to promote equity and justice (Diemer & Rapa, 2016; Diemer et al., 2017). Studies have shown that there is an underlying association of critical consciousness within empowerment constructs (Christens et al., 2018; Christens, Winn, & Duke, 2016). Critical consciousness was originally conceptualized and developed as a pedagogical method to foster Brazilian peasants’ ability to: (1) read the economic, political, historical, and social forces that contribute to inequitable social conditions; and (2) become empowered to change these conditions (Freire, 1968[2014]). Critical consciousness consists of three dimensions: (1) Critical reflection, which is defined as the ability to critically read social conditions; (2) sociopolitical efficacy, which is defined as those feelings of efficacy to effect change; and (3) critical action defined as actual participation in these efforts in the educational, political, and community domains (Godfrey & Grayman, 2014). Previous research has operationalized these components of critical consciousness as they pertain to the community and societal domains (Diemer, McWhirter, Ozer, & Rapa, 2015; Diemer & Rapa, 2016; Diemer et al., 2017; Diemer, Rapa, Voight, & McWhirter, 2016; Godfrey & Wolf, 2016; Gutiérrez, 1989; Halman, Baker, & Ng, 2017; Thomas et al., 2014; Watts et al., 2011).

Critical consciousness is an important component of youth and adolescent development, particularly among those youth of color in oppressed social positions (Christens et al., 2016; Diemer & Rapa, 2016; Watts & Hipolito-Delgado, 2015). Among youth, critical consciousness has been associated with positive developmental outcomes such as academic achievement among minority youth (Kwon, 2013; Ramos-Zayas, 2003), political engagement and advocacy among low-income youth (Diemer & Li, 2011), and with agency and action to resist stereotypes, challenge inequities, and persevere in school among Latinx youth (Chirstens et al., 2016). Diemer et al. (2014) specifically argued that to challenge institutional oppression and the effects of such injustices, it is essential for individuals to engage in participatory activities to create positive social change; thus, enhancing levels of empowerment.

Several measures have been examined to assess critical consciousnesses. There are, however, a limited number of measures that specifically examine critical consciousness among youth. For example, McWhirter and McWhirter (2016) developed and validated the Measure of Adolescent Critical Consciousness (MACC) among a sample of Latino/a adolescents. This measure showed a relationship between two dimensions of critical consciousness—i.e., Critical Agency and Critical Behavior. The study found that both dimensions were associated significantly with educational outcomes for Latino students (McWhirter & McWhirter, 2016). Thomas et al. (2014) developed and validated The Critical Consciousness Inventory (CCI) among a diverse sample of students from a predominantly White post-secondary institution and a Historically Black College/University. Most recently, Diemer et al. (2017) developed and validated the Critical Consciousness Scale (CCS) among a sample of diverse sample of individuals who were predominantly African American/Black (63%) or biracial/multiracial (24.6%). These authors’ findings converge with previous research suggesting that critical consciousness is composed of two components—i.e., Critical Agency and Critical Behavior. Taken together, these scales were rigorously validated and demonstrated strong psychometric properties. As Diemer et al. (2017) stated, critical consciousness, and their more recent validation of the CCS, have the “potential to unite and advance the fragmented conceptualization and indirect measurement of CC” (p. 476).

Measuring Cognitive Empowerment among Youth

There are few studies that have examined measures of cognitive PE and critical consciousness among youth. Research among youth on cognitive PE supports the multidimensionality of the CES among youth samples (Eisman et al., 2016; Miguel, Ornelas, & Maroco, 2015; Rodrigues et al., 2018; Speer et al., 2019). For instance, Miguel et al. (2015) described cognitive PE as being more efficient in measuring power and understanding the mechanisms of how power is distributed and executed, while PE was better reflected in intrapersonal (or emotional) empowerment measures. Elsewhere, Eisman et al. (2016) found evidence of discriminant validity for the three components of PE—e.g., intrapersonal or emotional, interactional or cognitive, and behavioral PE—and evidence of the multidimensionality of PE. Rodrigues, Menezes, and Ferreira (2018) also tested and validated the higher-order multidimensionality of PE, particularly the cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and relational components of PE, among Portuguese youth. These authors identified that all 12 first-order constructs—i.e., dimensions that encompass cognitive, emotional, behavior, and relational components of PE—captured a different aspect of second-order constructs (i.e., cognitive, emotional, behavior, and relational components of PE) and represent a single higher-order PE construct. This study provided important evidence for the multidimensionality of PE. Regarding cognitive PE specifically, Rodrigues et al. (2018) showed that cognitive PE is indeed measured through three dimensions. Most recently, Speer et al. (2019) tested the factor structure of an adapted CES among youth of color. These authors identified that this measure of CE did indeed encompass three larger dimensions of CE (Speer et al., 2019); however, they did not assess if there were differences between groups among their sample of youth of color, nor test the association this measure has with other measures within the larger PE construct (e.g., intrapersonal PE measured through the sociopolitical control scale). This study addresses these specific limitations.

There is a need to assess the cognitive PE scale as a distinct measure within PE and the broader nomological network of empowerment among a sample of youth (Christens et al., 2018; Lardier, Garcia-Reid, & Reid, 2019b; Lardier Jr., Barrios, Garcia‐Reid, & Reid, 2019c; Speer et al., 2019). Moreover, studies have alluded that differences may be present in the measurement of cognitive PE among various racial-ethnic groups, particularly those minority groups (e.g., African American/Black and Hispanic/Latinx youth) that have experienced social oppression and inequality (Christens et al., 2018; Peterson et al., 2002). Furthermore, whether we consider Black Racial Identity theory (Sellers, Chavous, & Cooke, 1998), Critical Race Theory, or Intersectionality Theory (Cerezo, McWhirter, Peña, Valdez, & Bustos, 2014; Collins, 2002; Hill-Collins & Bilge, 2016), it is reasonable to conclude that individuals with minority and intersecting social identities are likely to be more critically aware of power and social inequalities. Therefore, additional research is needed to examine for potential variations in the factor-structure of the CES among youth of color, particularly Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx youth, who have lived experiences that intersect with social disempowerment and oppression.

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to build upon the measurement and conceptualization of the CES among a sample of U.S. urban youth of color. The CES has yet to be tested to assess differences between African American/Black and Hispanic/Latinx urban youth. Additional research is needed to further examine the CES among adolescents of color in the U.S. To address these needs, we tested the factor structure of the CES among a sample of urban youth of color using Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Further, multigroup CFAs were conducted on the CES between African American/Black and Hispanic/Latinx youth to assess variation in the factor loadings between groups. Using a regression-based approach, we then examined the second-order three-factor model of the CES on intrapersonal PE and psychological SOC, as conceptually related variables.

Methods

Study Context

Nearly 80% of the residents in the target community identified as either Hispanic/Latina(o) (54%) or African American/Black (25%), and 33% of the residents were foreign born citizens (United States Census Bureau, 2017). Furthermore, 30% of the residents lived below the poverty line, with an average income of $33,964 (United States Census Bureau, 2017). In addition, as of 2016, this school district had a graduation rate of between 70% and 80%, with nearly 20% of students leaving school without graduating. Of those students who graduated high school and attended college, approximately 9.8% graduated from college. This is near equal to the college graduate rate among students of color across the United States (U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights, 2016).

Sample and Design

Data were collected in 2013 as part of a CSAP (Center for Substance Abuse Prevention) Minority AIDS Initiative (MAI) grant program. These data were gathered from a northeastern United States under-resourced urban school district. The data gathered helped to inform environmental strategies and prevention-intervention protocols within the target community and school system.

A convenience sample of 383 students were recruited through the target city’s largest high school’s physical education and health classes in grades 9 through 12 within the largest high school in the focal community. This high school was chosen because it was the largest in the school district and due to school choice, was deemed representative of the broader youth population who lived throughout the city, opposed to one section or quadrant. Power analyses were and indicated that minimum student sample size for regression-based approaches was based on a significant difference of .5, power .75, and a small effect size of .5 was 380 students (Faul, Erdfelder, Lang, & Buchner, 2007). In compliance with university Institutional Review Board (IRB) and state laws requiring active parental consent, and student assent, those students who returned both parental consent and student assent were eligible to complete the questionnaire over a 1-h time period (36.5% response rate). This response is low for school-based surveying; however, this outcome must be considered with laws from the focal state, which require active parent consent. Studies indicate that while active parental consent is important, it may in-fact influence the overall consent procedures and reduce the response rate of students (Nulty, 2008).

Students ranged from grades 9 through 12, with 29.2% in 9th grade, 45.7% in 10th grade, 6% in 11th grade, and 19.1% in 12th grade. Most students identified as Hispanic/Latina(o) (75%), with the next largest demographic group identifying as Black/African American (24.3%). A nearly equal proportion of students identified as male (46.9%) and female (53.1%), with 50.6% (n = 193) between 13 and 15 years of age and 49.4% (n = 190) between 16 to 18 years of age. Most of the youth received free or reduced lunch (75%), an indicator for low socioeconomic status (Harwell & LeBeau, 2010).

Measurement

See Table 1 for measurement descriptive statistics and correlation matrix.

Cognitive Empowerment

Speer and Peterson (2000) developed the interactional empowerment or the CES. Through principal components factor analyses, Speer and Peterson (2000) confirmed that the measure for CE encompassed three subscales: power through relationships (Cronbach’s α = .72; M =18.47, SD =3.83), nature of problem/political functioning (Cronbach’s α = .78; M =16.69, SD =4.24), and shaping ideologies (Cronbach’s α = .77; M =14.44, SD = 2.77). Rodrigues et al. (2018) tested the factor structure of the entire PE construct among 861 Portuguese youth. These authors similarly found that the overall CE scale: Cronbach’s α = .81; M =18.47, SD =3.83) encompassed the same three broad sub-scales of power through relationships (Cronbach’s α = .78), nature of problem/political functioning (Cronbach’s α = .76) and shaping ideologies (Cronbach’s α = .87). Most recently, Speer et al. (2019) adapted a measure of CES to be used among youth. Using CFA, these authors found that this adapted CES (Cronbach’s α = .88; M =3.79, SD =.68) for youth encompassed three broad subscales and was associated with the construct of social justice, as a conceptually related variable. For the current study, the four-item measure of power through relationships (Cronbach’s α = .81; M =3.99, SD = .85), the four-item measure of nature of power/political functioning (Cronbach’s α = .73; M =3.67, SD = .83), and the six-item measure of shaping ideologies (Cronbach’s α = .81; M =3.62, SD = .77) were combined (Cronbach’s α = .89; M =3.75, SD = .68). Participants responded using a five-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5).

Conceptually Related Variables

Intrapersonal PE

Intrapersonal PE was measured using an abbreviated 8-item scale, referred to as the Abbreviated Sociopolitical Control Scale for Youth (SPCS-Y) (Lardier Jr et al., 2018a; Peterson et al., 2006; Peterson, Peterson, Agre, Christens, & Morton, 2011). The scale encompasses two subscales. The first subscale was a four-item measure that assessed leadership (sample item: I am a leader in groups. I can usually organize people to get things done) (Cronbach α = .81, M =3.80, SD =.73). The second subscale used four-items and assessed policy control (sample item: There are plenty of ways for people like me to have a say in what our government does) (Cronbach α = .85, M = 3.58, SD =.70). Responses were recorded using a five-item Likert scale, ranging from definitely cannot, strongly disagree (1) to definitely can do it, strongly agree (5). Both scales were combined to reflect a single PE item (Cronbach α = .88, M = 3.30, SD =.61).

Psychological Sense of Community (SOC)

Psychological sense of community (SOC) was measured using eight-items (sample items: I feel like a member of this neighborhood.) from the Brief Sense of Community Scale (BSCS), which was based on the theoretical conjectures of McMillan and Chavis (1986) and the empirical work of Peterson, Speer, and McMillan (2008). The BSCS was designed to assess four-dimensions of SOC: needs fulfillment (NF), group membership (MB), influence (IN), and emotional connection (EC). Youth participants responded on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Through confirmatory factor analysis among a sample of youth, Lardier, Reid, & Garcia-Reid (2018b) illustrated and confirmed the BSCS (overall scale: Cronbach’s α = .85, Mean [M] = 3.08, Standard Deviation [SD] = .89) as a four-factor structure that examined NF (M = 3.11, SD = 1.04), .80 for MB (M = 3.13, SD = 1.08), .71 IN (M = 2.99, SD = 1.04), and .70 for EC (M = 3.07, SD = 1.08). For the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for the overall BSCS was .88 (M = 3.18, SD = .80). Alphas for each of the subscales were as follows: .75 for NF (M = 3.15, SD = 1.04), .80 for MB (M = 3.13, SD = 1.10), .75 IN (M = 3.01, SD = 1.04), and .73 for EC (M = 3.10, SD = 1.18).

Analytic Approach

Before main analyses, missing data were examined. Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) Test was used to assess the level and type of missingness (Little & Rubin, 2014). Little’s MCAR test revealed that the Chi square result was significant (χ2 = [df = 23] 43.23, p. = .006), and that these data were most likely not missing completely at random (MCAR). Although numerous missing data techniques are available (McGinniss & Harel, 2016), missing data for this study were handled using maximum likelihood (ML) through AMOS SEM software.

Following ML estimations of imputation, multigroup CFAs were conducted using IBM SPSS Amos (v. 25) software (Arbuckle, 2013) to assess the validity of the CES as a second-order, three-factor structure: power through relationships, nature of problem/political functioning, and shaping ideologies. Reflective models (scale) were fit, which specifies that the relationships emanate from a cognitive PE construct and are directed toward observed measures, suggesting that variation in the CES leads to variation in the three-factor structure, which leads to variations in the cognitive PE measures (Peterson et al., 2017). Multigroup CFAs were conducted on the CES between Hispanic/Latina(o) and African American/Black youth. Three models were examined:

Model 1 examined the three-factor model of cognitive PE and multigroup analyses were used to assess variation in responses between Hispanic/Latina(o) and African American/Black youth.

Model 2 tested the second-order three-factor model of cognitive PE was tested and multigroup analyses were used to assess variation in responses between Hispanic/Latina(o) and African American/Black youth.

Model 3 tested a structural equation regression analysis of the second-order three-factor model of cognitive PE on intrapersonal PE and psychological SOC, as conceptually related variable, between Hispanic/Latinx and African American/Black youth.

To assess model fit for the CFA models several fit indices were used. Chi square (χ2) was used as the primary indicator of model fit; however, because χ2 alone may be a too stringent indicator of goodness-of-fit, additional indices that are considered robust, were also examined. These include: Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (West, Taylor, & Wei, 2012). A non-significant χ2 value indicates acceptable model, higher values that are great than .95 on the GFI, AGFI, CFI, and TLI, and smaller RMSEA values that are less than .90 are desirable (Browne & Cudeck, 1992; West et al., 2012). Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) were also used to assess the better fitting model between model tests. For BIC, differences larger than 10.00 provide evidence in support of the lower BIC value (West et al., 2012). Regarding AIC, the solution closest to the saturated AIC value is considered as providing a better fit to the data (West et al., 2012).

Multigroup analyses were conducted using an unconstrained-constrained approach. First, an unconstrained model was run, which allowed parameters to vary freely. This analysis was followed by a fully constrained model, where parameters were constrained to be equivalent across groups (i.e., Hispanic/Latinx and African American/Black youth) (Hoyle, 2012). The unconstrained and constrained models were then compared using Chi square difference (χ 2diff ) testing to examine the presence of moderation in the overall models (Gaskin, 2012). Next, path specific moderation was conducted. Path moderation was significant if the Chi square result fell within the confidence interval (CI) range produced by the χ2 difference test.

Gender and age were also examined for variation with the CES, due to previous research suggesting that variation is likely present based on age and gender (Brian D Christens et al., 2018; Lardier Jr., 2019; Lardier Jr et al., 2018a; Rodrigues et al., 2018). Results indicated no significant difference between gender groups (χ2[44] = 59.25, p = .15) and age (F [6, 375] = .83, p = .55). No additional covariates were included.

Results

Table 2 displays the mode-fit statistics for the overall CES as a three-factor (model 1) and second-order model (model 2). The unconstrained model (χ2 = 103.64 (90), p = .15; CFI = .99; GFI = .96; AGFI = .95; RMSEA = .02 [95% CI = .01, .03], AIC = 287.64 [364]; BIC = 319.28; Bollen Stine Bootstrap p > .50) demonstrated good overall model-fit. Next, a constrained model was test, which demonstrated less than reasonable fit to the sample data (χ2 = 162.61 [110], p < .001; CFI = .96; GFI = .93; AGFI = .89; RMSEA = .02 [95% CI = .00, .05], AIC = 278.98 [364]; BIC = 301.35; Bollen Stine Bootstrap p > .50). Results from the multigroup analysis and Chi square difference (χ 2diff ) test indicated that moderation was not present at the model-level (Δχ2 = 14.47 (10), p = .15 [95% CI = 106–110.26]) or that this model was invariant. Based on these results, the unconstrained model was retained for further analyses.

The unconstrained three-factor model (model 1) provided overall good model-fit. All standardized factor loadings for this three-factor model were .55 to .79 at p < .001 for Hispanic/Latinx youth, and .50 to .90 at p < .001 for African American/Black youth. While this three-factor model displayed overall good-fit to the sample data, results indicated that model 2 had a better fit to the sample data. Model 2, the second multigroup CFA model, showed better model-fit, when compared to model 1.

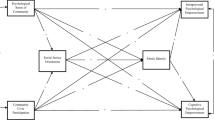

Fit statistics for the second order CES (Model 2) are also presented in Table 3. Standardized regression weights for the second-order model are presented in Fig. 1. The unconstrained model demonstrated good overall model-fit: χ2 = 93.35 (86), p = .27; CFI = .99; TLI = .99; GFI = .96; AGFI = .95; RMSEA = .01 (95% CI = .000, .03) AIC = 285.35 (364); BIC = 307.94 (406). Bollen-Stine bootstrapping results showed that the p value was greater than .05 (p =.89), indicating that the proposed model is consistent with the sample data (Walker & Smith, 2016). A constrained model was analyzed next. This model demonstrated less than reasonable fit, when compared to the unconstrained model: χ2 = 107.52 [98], p = .24; CFI = .99; GFI = .96; AGFI = .89; RMSEA = .02 [95% CI = .00, .03], AIC = 275.52 [364]; BIC = 295.28. Bollen-Stine bootstrapping results (p =.41) indicated that the proposed constrained model is consistent with the sample data. The Chi square difference (χ 2diff ) test illustrated that models were invariant, or groups were not different at model level (Δχ2 = 14.10 (12), p = .29 [95% CI = 96.10–100.03]). The unconstrained model was retained for further analyses.

See Fig. 1. All standardized factor loadings for this second-order model ranged from .70 to .89 at p < .001 for Hispanic/Latinx youth, and .77 to .88 at p < .001 for African American/Black youth. First order weights ranged from .55 to .79 for Hispanic/Latinx youth and .50 to .89 for African American/Black youth. For Hispanic/Latinx youth the model explained 55% of the variance in power through relationships, 90% of the variance in nature of power, and 70% of the variance in shaping ideologies. For the African American/Black sample of youth, the model explained 60% of the variance in power through relationships, 95% of the variance in nature of power, and 60% of the variance in shaping ideologies. Path-level moderation was conducted next to assess invariance at the path level. Results indicate no significant differences at the path-level.

The final analysis explored the association with intrapersonal PE and psychological SOC as conceptually related variables (see Fig. 2). A structural equation regression analysis of the scale was conducted. The association allows for a test of predictive validity of the cognitive PE scale among youth to scores on intrapersonal PE and psychological SOC. Results of model fit presented in Table 2, and Fig. 2 presents standardized beta weight coefficients. The cognitive PE scale among youth significantly predicted intrapersonal PE among Hispanic/Latinx (R2 = .15) and African American/Black youth (R2 = .14), as well psychological SOC among Hispanic/Latinx (R2 = .15) and African American/Black youth (R2 = .10).

Multigroup Second-order CFA of the Cognitive Empowerment Scale of Psychological Empowerment and Cognitive Empowerment predicting Intrapersonal Psychological Empowerment among Hispanic/Latina(o) and African American/Black Youth. Note Hispanic/Latina(o) outside of parentheses and African American/Black within parentheses; CE cognitive empowerment, PE psychological empowerment, NF needs fulfillment, MB membership, IN influence, EC emotional control

Discussion

Empowerment is a high order, multilevel theory that can be conceptualized differently in various groups and communities (Zimmerman, 2000). While recent scholarship has focused on further developing the nomological understanding of empowerment (e.g., Rodrigues et al., 2018), PE remains largely understudied, despite receiving the greatest attention in the empowerment literature (Peterson, 2014). While the intrapersonal component of PE has occupied a particularly important role in understanding and measuring empowerment, other dimensions of the broader PE construct have been given less attention, specifically the cognitive or interactional component of PE (Christens et al. 2013; Peterson et al. 2002).

Cognitive PE has been broadly understood as a component of PE that considers an individual’s critical awareness or a critical understanding of the sociopolitical system, which in-turn allows them to act strategically and effectively to engage in social change (Speer, 2000; Speer & Peterson, 2000). Previously, scholarship has tested the factor structure of the CES and illustrated that this measure is composed of three components—i.e., knowledge of the source of social power, knowledge of the nature of social power, and knowledge of the instruments of social power (Eisman, et al., 2016; Rodrigues et al., 2018; Speer & Peterson, 2000; Speer et al., 2019). Studies using the CES have associated cognitive PE not only with greater leadership and self-efficacy in the sociopolitical domain (i.e., measured through intrapersonal PE and the SPCS-Y; Lardier et al., 2018a), but also with greater mental well-being, civic engagement, a greater SOC, and being more social justice oriented (Christens et al., 2018). Furthermore, cognitive PE and critical consciousness share some conceptual overlap (Christens et al., 2018), with critical consciousness, more specifically, theorized as a multicomponent construct with both cognitive and emotional or intrapersonal empowerment (Watts et al., 2011).

Our findings, notably model 2, converge with previous scholarship (e.g., Speer et al., 2019), suggesting that cognitive PE is a higher order variable comprised of three subcomponents—i.e., knowledge of the source of social power, knowledge of the nature of social power, and knowledge of the instruments of social power—which in-turn load onto a single CE construct. Furthermore, preliminary evidence from this study builds on previous research of the CES among youth (see Speer et al., 2019) and indicates that there were no significant differences between Hispanic/Latinx and African American/Black youth on the three dimensions of cognitive PE loading onto a larger cognitive PE construct. This is a notable finding as it provides some evidence that the measurement of cognitive PE may diverge minimally among historically marginalized groups in the U.S., who have a similar understanding of how power is manifested and maintained and how resources are distributed, particularly when compared to White non-Hispanics (Peterson & Speer, 2000).

A cursory glance at recent social movements would illustrate that the lives and identities of individuals of color in the U.S. intersect with experiences and awareness of critical social issues (Watts et al., 2011). For example, more recent events such as the #BlackLivesMatter movements, DREAMer rallies, and the “Families Belong Together” march, the latter two highlighting detrimental federal policies put forward by the current U.S. presidential administration, are also examples of critical social issues. The critical awareness communities of color share as a result of being disempowered and oppressed by U.S. society may be considered a shared group membership and identity (Flanagan, Syvertsen, Gill, Gallay, & Cumsille, 2009; Hipolito-Delgado & Lee, 2007; Stepick & Stepick, 2002; Watts et al., 2011) that may help create and maintain one’s political self-efficacy (Christens et al., 2018) and drive individuals toward action and change (Lardier Jr et al., 2019a). These findings are, therefore, imbedded within the intersecting domains of oppression, as well as history and context that force individuals in minority social positions to have similar perceptions of power and how they understand power within their communities and social spaces. Hence, it is not necessarily surprising to show no group differences between historically oppressed and marginalized racial-ethnic groups.

Results from this study also highlight the association cognitive PE has with intrapersonal or emotional PE (measure through the abbreviated SPCS-Y) and psychological SOC, providing preliminary empirical evidence for the association between intrapersonal PE and cognitive PE, as well the association cognitive PE has with psychological SOC, as a conceptually related variable (Lardier, et al., 2019b). This finding is important because while there is a theoretical association between intrapersonal PE and cognitive PE, minimal scholarship has examined this connection among youth of color (Christens et al., 2018; Lardier et al., 2019a; Lardier Jr et al., 2019b). Taken together, findings from this study provide initial empirical support for the validity of the CES among a sample of youth of color and the empirical association between intrapersonal PE and cognitive PE.

Implications for Research and Theory

The main implication of our findings is that cognitive PE can be conceptualized and measured through three distinct dimensions among youth populations and that there is no difference, at least within this sample, between Hispanic/Latinx and African American/Black youth in the scales factor loadings. Results reinforce recent scholarship identifying the CES as encompassing three broad dimensions (e.g., Rodrigues et al., 2018); however, future researchers are advised to continually examine the CES among diverse samples of youth both in the U.S. and internationally. Additional research is also needed to assess the full nomological network of PE among youth (notable exceptions include Rodrigues et al., 2018), continue to assess measures of PE dimensions among various racial-ethnic groups, and equally important, gender differences in how these scales are developed and validated. Future studies are, therefore, advised to continue to investigate the CES and conceptually related measures among diverse groups of youth and adults.

Equally important is the need to unite and advance the fragmented conceptualization of cognitive PE with critical consciousness. Despite advances in both the measurement of cognitive PE and critical consciousness, as noted above, there has been no study to these author’s knowledge that has attempted to understand the convergence between measures of critical consciousness and the CES. Such fragmented and siloed work does little to advance the scholarship on these two concepts, as well as the shared affinity to understand the importance of how critical awareness, action, reflection, and knowledge work toward empowering individuals, but also promoting overall positive trajectories in human development.

Implications for Social Work Practice

While this study tested the structure of a measure of cognitive PE, it does highlight the importance of such measures to understand the ways in which youth of color formulate a critical understanding of their social world. Further, such measures remove a risk-based assessment of these youth and instead positions these young people as critical observers of society and with an active interest in executing social change (Lardier, 2019). This study aims to portray youth through a strengths-based lens and approach. Such a tool would assist both social workers and youth-workers, alike, to develop programs that critically engage and empower youth of color (Opara, Rivera Rodas, Lardier, Garcia-Reid, & Reid, 2019). Hence, in this study we begin to observe the “importance of youth empowerment in oppressed and marginalized spaces and the need to engage youth in a way that considers both a critical read of the ecology of youth’s daily lives and their ethnic roots and cultural backgrounds” (Lardier et al., 2019a, p. 15).

Supporting the advancement of youth of color with backgrounds that intersect with social oppression, disenfranchisement, poverty, and systemic racism to engage in critical and emancipatory ways of social change is of importance in an era of every shrinking funding and neoliberal policies that place the onus of responsibility on the youth themselves (Baldridge, 2019; Lardier, Herr, Bergeson, Garcia-Reid, & Reid, 2019c). Youth of color are often viewed as “at-risk” and in need of saving (Baldridge, 2019), opposed to savvy actors able to enact critical social change on behalf of their communities (Lardier, 2019). Researchers can use empowerment-based scales such as the one tested in this study to develop a deeper understanding of youth’s awareness of social inequality and the ways in which to encourage programing to foster critical consciousness, as well as bolster confidence in their own minority identities (Opara et al., 2019). Taking an approach that considers youth’s awareness of social injustice and power and bridging with ideas surrounding cultural humility and awareness (see Wallerstein, Duran, Oetzel & Minkler, 2017) may create a space for hope, thriving, and regaining power and justice.

Limitations

Despite the importance of findings from this study, additional research is needed to test the factor structure of the CES among diverse samples of youth and adults from varying sociocultural and contextual backgrounds. Such scholarship will push investigators and practitioners of empowerment to better understand the empowerment process among diverse groups of youth both in the U.S. and internationally. One limitation of this study is that findings are context bound to the northeastern corridor of the U.S. Due to cognitive PE and the broader PE construct taking different forms, for different people, in different contexts, it is important that the CES be examined and validated with youth located in other communities and regions across the U.S. Therefore, a single measure of cognitive PE is not appropriate and should be examined among varying populations before widespread use.

A second limitation concerns the Likert-type scale response system. While this may be a small limitation, more recent scholarship (e.g., Peterson et al., 2017) has shown that when validating the intrapersonal component of PE, a phrase completion format helped to reduce bias and improve the validity of the scale. Therefore, future research should examine both the phrase completion format and Likert-type scale response format of the CES. Using the CES alongside qualitative research, such as a mixed-method study, would give scholars a way to understand the subjective experiences and meanings that marginalized or oppressed people attach to the three dimensions measured through cognitive PE. This may help elucidate how we measure these dimensions and under what conditions cognitive PE may inform social action and change.

A third limitation concerns the response rate for the given study of 36.5%. While a lower overall response rate for survey-based research in schools, this must be considered with the state laws of the focal state, which require active parent consent. Studies indicate that while active parental consent is important, it may in-fact influence the overall consent procedures and reduce the response rate of students (Nulty, 2008). School-based research needs to consider such limitations and work with the school district to sample a larger number of students to offset any associated methodological response bias (White, Hill, & Effendi, 2004).

A final limitation concerns the measurement of Hispanic/Latinx and African American/Black identity. Within-group differences are likely present among these Hispanic/Latinx and African American/Black youth. While demographically labeled “Hispanic” and “African American” or “Black” there are significant within-group variations, based on ethnic background such as Puerto Rican or Dominican for “Hispanic” youth, and Haitian and African (with additional cultural identities within this) for “Black” youth. Generational status (e.g., newly immigrated versus third generation) is also likely to have implications in how individuals identify and in their critical awareness of power and inequality. Therefore, future studies are advised to examine these more nuanced intersections in our understanding of cognitive PE, the CES, and the broader nomological network of empowerment.

Conclusion

The aim of the current study was to test the factor structure of the CES, as well as assess for differences between Hispanic/Latinx and African American/Black racial-ethnic identity among urban youth. It is critical to develop measurement tools that capture the perceptions of cognitive PE among youth from diverse social, cultural, and contextual backgrounds. While this study found support for the multidimensionality of the CES, and its relationship with the intrapersonal component of PE, there is still a need to test this measure among youth in other socio-cultural settings, as well as examine the full nomological network of PE among youth (notable exceptions include Rodrigues et al., 2018). Empowerment has the potential to bring about positive transformational change in individuals, groups, and communities.

The continued development of empowerment measures may allow for greater inclusion of empowerment in both the developmental and prevention sciences. An empowerment approach is crucial to understand power and engage in effective social and liberating community change. Now more than ever in the U.S., researchers, clinicians and community leaders, need to understand how to empower young people to becoming change agents within their communities. However, part of this is contingent on the continued development of empowerment measures to understand the diversity of individuals, groups, organizations, and communities through future studies.

References

Arbuckle, J. L. (2013). Amos 22 user’s guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS.

Baldridge, B. J. (2019). Reclaiming community: Race and the uncertain future of youth work: Stanford University Press. CA: Redwood.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258.

Cerezo, A., McWhirter, B. T., Peña, D., Valdez, M., & Bustos, C. (2014). Giving voice: Utilizing critical race theory to facilitate consciousness of racial identity for Latina/o college students. Journal for Social Action in Counseling & Psychology, 5(3), 1–24.

Christens, B. D. (2012). Toward relational empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 50(1–2), 114–128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-011-9483-5.

Christens, B. D., Byrd, K., Peterson, N. A., & Lardier, D. T. (2018). Critical hopefulness among urban high school students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1649–1662.

Christens, B. D., Collura, J. J., & Tahir, F. (2013). Critical hopefulness: A person-centered analysis of the intersection of cognitive and emotional empowerment. American Journal of Community Psychology, 52(1–2), 170–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9586-2.

Christens, B. D., Winn, L. T., & Duke, A. M. (2016). Empowerment and critical consciousness: A conceptual cross-fertilization. Adolescent Research Review, 1(1), 15–27.

Collins, P. H. (2002). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge.

Diemer, M. A., & Li, C. H. (2011). Critical consciousness development and political participation among marginalized youth. Child Development, 82(6), 1815–1833.

Diemer, M. A., McWhirter, E. H., Ozer, E. J., & Rapa, L. J. (2015). Advances in the conceptualization and measurement of critical consciousness. The Urban Review, 47(5), 809–823.

Diemer, M. A., & Rapa, L. J. (2016). Unraveling the complexity of critical consciousness, political efficacy, and political action among marginalized adolescents. Child Development, 87(1), 221–238.

Diemer, M. A., Rapa, L. J., Park, C. J., & Perry, J. C. (2017). Development and validation of the Critical Consciousness Scale. Youth & Society, 49(4), 461–483.

Diemer, M. A., Rapa, L. J., Voight, A. M., & McWhirter, E. H. (2016). Critical consciousness: A developmental approach to addressing marginalization and oppression. Child Development Perspectives, 10(4), 216–221.

Eisman, A. B., Zimmerman, M. A., Kruger, D., Reischl, T. M., Miller, A. L., Franzen, S. P., & Morrel-Samuels, S. (2016). Psychological empowerment among urban youth: Measurement model and associations with youth outcomes. American Journal of Community Psychology, 58(3–4), 410–421.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191.

Flanagan, C. A., Syvertsen, A. K., Gill, S., Gallay, L. S., & Cumsille, P. (2009). Ethnic awareness, prejudice, and civic commitments in four ethnic groups of American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(4), 500–518.

Freire, P. (1968[2014]). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

Gaskin, J. (2012). Chi Square difference testing. Gaskination’s StatWiki. Retrieved from http://statwiki.kolobkreations.com.

Ginwright, S. (2015). Hope and healing in urban education: How urban activists and teachers are reclaiming matters of the heart. New York: Routledge.

Godfrey, E. B., & Grayman, J. K. (2014). Teaching citizens: The role of open classroom climate in fostering critical consciousness among youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(11), 1801–1817.

Godfrey, E. B., & Wolf, S. (2016). Developing critical consciousness or justifying the system? A qualitative analysis of attributions for poverty and wealth among low-income racial/ethnic minority and immigrant women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(1), 93–103.

Gutiérrez, L. (1989). Critical consciousness and Chicano identity: An exploratory analysis. In G. Romero (Ed.), Estudios Chicanos and the politics of community (pp. 35–53). Berkeley, CA: NACS Press.

Gutiérrez, L. M. (1995). Understanding the empowerment process: Does consciousness make a difference? Social Work Research, 19(4), 229–237.

Halman, M., Baker, L., & Ng, S. (2017). Using critical consciousness to inform health professions education. Perspectives on Medical Education, 6(1), 12–20.

Harwell, M., & LeBeau, B. (2010). Student eligibility for a free lunch as an SES measure in education research. Educational Researcher, 39(2), 120–131.

Hill-Collins, P., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Malden, MA: Polity Press.

Hipolito-Delgado, C., & Lee, C. (2007). Empowerment theory for the professional school counselor: A manifesto for what really matters. Professional School Counseling, 10(4), 327–332.

Hope, E. C., & Jagers, R. J. (2014). The role of sociopolitical attitudes and civic education in the civic engagement of black youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(3), 460–470.

Hoyle, R. H. (Ed.). (2012). Handbook of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Press.

Kirshner, B. (2015). Youth activism in an era of education inequality. New York: New York University Press.

Kwon, S. A. (2013). Uncivil youth: Race, activism, and affirmative governmentality. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Lardier, D. T., Jr. (2018). An examination of ethnic identity as a mediator of the effects of community participation and neighborhood sense of community on psychological empowerment among urban youth of color. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(5), 551–566.

Lardier, D. T., Jr. (2019). Substance use among urban youth of color: Exploring the role of community-based predictors, ethnic identity, and intrapersonal psychological empowerment. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 25(1), 91.

Lardier, D. T., Jr., Barrios, V. R., Garcia-Reid, P., & Reid, R. J. (2019a). A latent class analysis of cognitive empowerment and ethnic identity: An examination of heterogeneity between profile groups on dimensions of emotional psychological empowerment and social justice orientation among urban youth of color. Journal of Community Psychology, 47, 1530–1546.

Lardier, D. T., Garcia-Reid, P., & Reid, R. J. (2019b). The examination of cognitive empowerment dimensions on intrapersonal psychological empowerment, psychological sense of community, and ethnic identity among urban youth of color. The Urban Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-019-00504-7.

Lardier, D. T., Herr, K. G., Bergeson, C., Garcia-Reid, P., & Reid, R. J. (2019c). Locating disconnected minoritized youth within urban community-based educational programs in an Era of Neoliberalism. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1680902.

Lardier, D. T., Jr., Reid, R. J., & Garcia-Reid, P. (2018a). Validation of an abbreviated Sociopolitical Control Scale for Youth among a sample of underresourced urban youth of color. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(8), 996–1009.

Lardier, D. T., Jr., Reid, R. J., & Garcia-Reid, P. (2018b). Validation of the Brief Sense of Community Scale among youth of color from an underserved urban community. Journal of community psychology, 46(8), 1062–1074.

Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (2014). Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley.

McGinniss, J., & Harel, O. (2016). Multiple imputation in three or more stages. Journal of Statistical Planning and Inference, 176, 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspi.2016.04.001.

McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6629.

McWhirter, E. H., & McWhirter, B. T. (2016). Critical consciousness and vocational development among Latina/o high school youth: Initial development and testing of a measure. Journal of Career Assessment, 24(3), 543–558.

Miguel, M. C., Ornelas, J. H., & Maroco, J. P. (2015). Defining psychological empowerment construct: Analysis of three empowerment scales. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(7), 900–919.

Nulty, D. D. (2008). The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: what can be done? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(3), 301–314.

Opara, I., Rivera Rodas, E. I., Lardier, D. T., Garcia-Reid, P., & Reid, R. J. (2019). Validation of the abbreviated Socio-Political Control Scale for Youth (SPCS-Y) Among Urban Girls of Color. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-019-00624-9.

Perkins, D. D., & Zimmerman, M. A. (1995). Empowerment theory, research, and application. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 569–579.

Peterson, N. A. (2014). Empowerment theory: Clarifying the nature of higher-order multidimensional constructs. American Journal of Community Psychology, 53(1–2), 96–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-013-9624-0.

Peterson, N. A., Hamme Peterson, C., & Speer, P. W. (2002). Cognitive empowerment of African Americans and caucasians: Differences in understandings of power, political functioning, and shaping ideology. Journal of Black Studies, 32(3), 336–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/002193470203200304.

Peterson, N. A., Lowe, J. B., Hughey, J., Reid, R. J., Zimmerman, M. A., & Speer, P. W. (2006). Measuring the intrapersonal component of psychological empowerment: Confirmatory factor analysis of the sociopolitical control scale. American Journal of Community Psychology, 38(3–4), 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-006-9070-3.

Peterson, N. A., Peterson, C. H., Agre, L., Christens, B. D., & Morton, C. M. (2011). Measuring youth empowerment: Validation of a sociopolitical control scale for youth in an urban community context. Journal of Community Psychology, 39(5), 592–605. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20456.

Peterson, N. A., Speer, P. W., & McMillan, D. W. (2008). Validation of a brief sense of community scale: Confirmation of the principal theory of sense of community. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(1), 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20217.

Peterson, N. A., Speer, P. W., Peterson, C. H., Powell, K. G., Treitler, P., & Wang, Y. (2017). Importance of auxiliary theories in research on university-community partnerships: The example of psychological sense of community. Collaborations: A Journal of Community-Based Research and Practice, 1(1), 5.

Ramos-Zayas, A. Y. (2003). National performances: The politics of class, race, and space in Puerto Rican Chicago. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Rappaport, J. (1987). Terms of empowerment/exemplars of prevention: Toward a theory for community psychology. American Journal of Community Psychology, 15, 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00919275.

Rappaport, J., Rappaport, J., Swift, C., & Hess, R. (1984). Studies in empowerment: Introduction to the issue. Studies in Empowerment: Steps Toward Understanding and Action, 3, 1.

Rodrigues, M., Menezes, I., & Ferreira, P. D. (2018). Validating the formative nature of psychological empowerment construct: Testing cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and relational empowerment components. Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1), 58–78.

Sellers, R. M., Chavous, T. M., & Cooke, D. Y. (1998). Racial ideology and racial centrality as predictors of African American college students’ academic performance. Journal of Black Psychology, 24(1), 8–27.

Speer, P. W. (2000). Intrapersonal and interactional empowerment: Implications for theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1520-6629(200001)28:1%3c51:aid-jcop6%3e3.0.co;2-6.

Speer, P. W., & Hughey, J. (1995). Community organizing: An ecological route to empowerment and power. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 729–748. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02506989.

Speer, P. W., & Peterson, N. A. (2000). Psychometric properties of an empowerment scale: Testing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral domains. Social Work Research, 24(2), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/24.2.109.

Speer, P. W., Peterson, N. A., Christens, B. D., & Reid, R. J. (2019). Youth cognitive empowerment: Development and evaluation of an instrument. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(3–4), 528–540.

Stepick, A., & Stepick, C. D. (2002). Becoming American, constructing ethnicity: Immigrant youth and civic engagement. Applied Developmental Science, 6(4), 246–257.

Thomas, A. J., Barrie, R., Brunner, J., Clawson, A., Hewitt, A., Jeremie-Brink, G., & Rowe-Johnson, M. (2014). Assessing critical consciousness in youth and young adults. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(3), 485–496.

United States Census Bureau. (2015). Quick Facts: United States. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/00,36,34.

U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights. (2016). 2013–2014 Civil rights data collection: A first look. Key data highlights on equity and opportunity gaps in our nation’s public schools. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education

Walker, D. A., & Smith, T. J. (2016). Computing robust, bootstrap-adjusted fit indices for use with nonnormal data. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, Online First. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175616671365.

Wallerstein, N., Duran, B., Oetzel, J. G., & Minkler, M. (2017). Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity. New York: Wiley.

Watts, R. J., Diemer, M. A., & Voight, A. M. (2011). Critical consciousness: Current status and future directions. In C. A. Flanagan & B. D. Christens (Eds.), New directions for child and adolescent development (pp. 43–57). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Watts, R. J., & Hipolito-Delgado, C. P. (2015). Thinking ourselves to liberation?: Advancing sociopolitical action in critical consciousness. The Urban Review, 47(5), 847–867.

West, S. G., Taylor, A. B., & Wei, W. (2012). Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 209–231). New York: Guilford Press.

White, V. M., Hill, D. J., & Effendi, Y. (2004). How does active parental consent influence the findings of drug-use surveys in schools? Evaluation Review, 28(3), 246–260.

Zimmerman, M. A. (1995). Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23(5), 581–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02506983.

Zimmerman, M. A. (2000). Empowerment theory: Psychological, organizational, and community levels of analysis. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp. 44–59). New York: Plenum Publishers.

Funding

Funding was provided by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Center for Substance Abuse Prevention (CSAP), Grant No. SP-15104.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors. Ijeoma Opara (or second co-author) received funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5T32 DA007233) training grant as a predoctoral fellow. Points of view, opinions, and conclusions in this paper do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Government.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lardier, D.T., Opara, I., Garcia-Reid, P. et al. The Cognitive Empowerment Scale: Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analysis Among Youth of Color. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 37, 179–193 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-019-00647-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-019-00647-2