Abstract

Changes in the adolescent brain underlie the development of executive functions (EFs) after the onset of puberty; however, adolescents that engage in deliberate self-harm (DSH) have impaired EFs in the areas of inhibition, emotion regulation, shifting, and interpersonal functioning. On the other hand, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) has been shown to be effective in treating adolescents with DSH. Moreover, the DBT skills of mindfulness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, and “walking the middle path” are suited to treat these adolescents with impaired EFs. This single group pre-post study examined changes in adolescents’ EFs who were enrolled in DBT. Ninety-three adolescents from a 16-week DBT program for DSH were administered the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Self Report (BRIEF-SR) at pre-treatment and post-treatment. Adolescents improved from the elevated to non-clinical range on the Emotional Control, Shifting, and Monitor scales in addition to the Global Executive Composite of the BRIEF-SR. Significant effects for funding type on shifting, interpersonal functioning, and overall EF were observed while a significant effect for previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations was observed for emotion regulation. DBT appears to be effective for improving the EFs of adolescents with DSH and for specific subgroups of this population. Knowledge of these adolescents’ profile of EFs will assist clinicians in determining the type and level of intervention with DBT in order to shape positive behaviors during this important period of brain development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Deliberate Self-Harm (DSH) and Its Course in Adolescence

Deliberate self-harm (DSH) is the deliberate, non-fatal, intentional destruction of one’s own body tissue and is not socially sanctioned or acceptable. This umbrella term also encompasses the term non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), which is characterized by self-harming behaviors that occur without suicidal intent. In terms of diagnostics, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) has included NSSI in the “Conditions for Further Study” section with the core features comprising purposeful engagement in repetitive and shallow painful damage to one’s body tissue without suicidal intent on five or more occasions throughout the last year. For the purposes of this study, the term deliberate self-harm will be used in order to include self-damaging behaviors to body tissue regardless of intent. DSH represents a significant public health concern among adolescents as approximately 13–45% of adolescents in community samples report a history of DSH (Choate, 2012), while among psychiatric populations the rates of DSH have been shown to be two to four times greater when comparing adolescents (40–80%) (Kerr, Muehlenkamp, & Turner, 2010) to adults (21%) (Briere & Gill, 1998). Research suggests that DSH most commonly occurs between the ages of 12 and 14 (Cipriano, Cella, & Cotrufo, 2017) with an increase in these behaviors during this period of adolescence and later decline in young adulthood (Plener, Schumacher, Munz, & Groschwitz, 2015).

How is DSH Measured?

DSH is typically assessed through behavioral measures in the form of a questionnaire and/or standardized interview. Commonly used scales include the Functional Assessment of Self-Mutilation (FASM), Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire (SHBQ), Self-Injury Questionnaire Treatment Related (SIQTR), Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI), Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI), Inventory of Statements About Self-Injury (ISAS), Self-Harm Information Form (SHIF), and Self-Harm Inventory (SHI). In general, these tools assess for specific methods of self-harm along with the frequency and recency of these damaging behaviors and can include various factors such as age of onset, lifetime presence, and duration depending on the measure (Latimer, Meade, & Tennant, 2013).

Comorbidities Associated with DSH in Adolescence

Estimates for comorbid psychiatric conditions in self-harming adolescents include major depression (2.2–96.2%), other mood disorders (13–62%), anxiety disorders (42.9–82.7%), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (16.9–24.1%), eating disorders (7.8–31%), alcohol use disorder/dependence (4.2–43.7%), drug use disorder/dependence (13.0–45.2%), substance use disorder/dependence (2.6–27.6%), oppositional defiant disorder (10.9%), conduct disorder (10.5–13.0%), other behavioral disorders (6.9–68.8%), and borderline personality disorder (20.5–72.5%) (Hawton et al., 2015).

Risk Factors for DSH in Adolescence

Multiple risk factors for DSH in adolescents have been identified and include perfectionistic personality traits, low self-esteem, impulsivity, poor emotional expressivity, non-heterosexual orientation, poor distress tolerance, social withdrawnness, invalidating environments during childhood, family and/or friend history of self-harm, and dysfunctional family systems (Lauw, How, & Loh, 2015). Psychiatric disorders, history of childhood trauma, poor parental attachment (Cipriano et al., 2017), prior psychiatric hospitalizations (Lloyd-Richardson, Perrine, Dieker, & Kelley, 2007), and female gender (Kokkevi, Rotsika, Arapaki, & Richardson, 2012; Plener et al., 2015) are also associated with DSH in adolescents. Other risk factors for adolescent self-harm include substance use, low socioeconomic status, and not living with both parents in the home (Kokkevi et al., 2012). Moreover, additional research suggests that children with public or no insurance have decreased access to mental health services (Burnett-Zeigler & Lyons, 2010). Proposed models for the functions of DSH in adolescents include but are not limited to affect-regulation, attempts to avoid suicide, anti-dissociation, self-punishment, sensation-seeking, affirming interpersonal boundaries, and communicating needs and wants to others (Lauw et al., 2015).

Brain Development in Adolescence and Executive Functions (EFs)

Adolescence coincides with the fine-tuning of neural networks involving the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the brain (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006) and the expansion of executive functions (EFs) or higher-level processes that are involved in the regulation of cognitions, emotions, and adaptive social behaviors (Lalonde, Henry, Germain, Nolin, & Beauchamp, 2013). With regards to gray matter (GM), the adolescent brain undergoes the process of synaptic pruning in PFC regions where frequently used connections are strengthened and infrequently used connections are eliminated (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006) and these changes have been linked to improved emotion regulation skills (Vijayakumar et al., 2014) as well as intellectual ability (Shaw et al., 2006). The linear development of white matter (WM) involving the PFC during adolescence has been associated with improved EFs such as inhibition (Seghete, Herting, & Nagel, 2013), shifting (Seghete et al., 2013), and interpersonal functioning (De Pisapia et al., 2014). Changes in the activation levels of PFC networks have also been linked to greater mastery of EFs such as inhibition (Marsh et al., 2006; Rubia et al., 2006; Tamm, Menon, & Reiss, 2002), emotion regulation (McRae et al., 2011; Pitskel, Bolling, Kaiser, Crowley, & Pelphrey, 2011), interpersonal functioning (Masten et al., 2009; Moor et al., 2012), and shifting (Ezekiel, Bosma, & Morton, 2013; Morton, Bosma, & Ansari, 2009; Rubia et al., 2006). As a result, these changes in WM, GM, and activation levels reflect the dynamic growth of EFs during adolescence.

Impaired EFs in Adolescents with DSH

Adolescents with DSH have impaired EFs in the areas of inhibition (Madge et al., 2011), emotion regulation (Mikolajczak, Petrides, & Hurry, 2009), set-shifting (Paris, Zelkowitz, Guzder, Joseph, & Feldman, 1999), problem-solving after switching from a stressful situation (Nock & Mendes, 2008), and interpersonal functioning (You, Leung, & Fu, 2012). Neuroimaging studies have also identified adolescents with borderline personality disorder, a condition not only characterized by DSH and suicidal behaviors, but also by impulsivity, emotion dysregulation, and impaired interpersonal functioning, as having altered brain development in terms of WM (Maier-Hein et al., 2014; New et al., 2013) and GM (Brunner et al., 2010; Richter et al., 2014) in PFC regions that are important for the maturation of EFs.

DBT for Adolescents with DSH and Rationale for Improving EFs

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an extension of cognitive behavioral therapy that was originally developed by Marsha Linehan in order to treat suicidal patients that met criteria for borderline personality disorder (Linehan et al., 2006). This treatment specifically targets suicidality and self-harming behaviors as well therapy interfering behaviors that disrupt treatment (Linehan et al., 2006). Of note, dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents is a promising intervention for pediatric populations that engage in self-harm. In examining clinical effectiveness studies, Sunseri (2004) demonstrated that DBT was effective in reducing early terminations due to suicidality and number of psychiatric inpatient stays due to self-harming behaviors for adolescents in residential care over the course of 29 months after the intervention was implemented.

In another effectiveness study, James et al. (2008) implemented DBT exclusively with a community sample of adolescent females with DSH and demonstrated that this intervention was not only effective for reducing depression and episodes of self-harm but also for improving general functioning. Moreover, these gains were maintained at their 8-month follow-up assessment. Likewise, Fleischhaker et al. (2011) demonstrated that adolescents in DBT had significant and stable reductions in suicidality and self-harming behaviors over the course of one year. Similarly, James, Winmill, Anderson, and Alfoadari (2011) observed significant declines in depression, hopelessness, and self-harm with an adolescent community sample after a year of treatment with DBT.

In terms of comparison studies, Katz, Cox, Gunasekara, and Miller (2004) demonstrated that DBT and treatment as usual interventions were both effective in reducing self-harming behaviors and depressive symptoms at the one-year follow up for adolescent inpatients and that DBT significantly reduced their behavioral incidents during their psychiatric stay. Moreover, McDonell et al. (2010) also conducted a pilot study with adolescent inpatients and found that individuals who were exposed to DBT had significant reductions in self-harming behaviors across 12-months of hospitalization when compared to historical controls. Lastly, Mehlum et al. (2014) demonstrated in a randomized control trial study that DBT was superior to enhanced usual care in reducing self-harming behaviors over the course of a 15-week period.

First Hypothesis for Study

DBT appears to be an effective intervention that has been successfully utilized in the inpatient, residential, and outpatient setting with adolescents who engage in DSH. However, no DBT studies to our knowledge have examined changes in EF for adolescents with DSH who are enrolled in this treatment. Moreover, the core DBT skills of mindfulness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, and “walking the middle path” are ideally suited to treat their areas of EF impairment and help shape the developing adolescent brain. As such, the goal of this study was to investigate changes in EF for adolescents with DSH that were enrolled in DBT. The first hypothesis was that there will be a significant reduction in the level of executive dysfunction for adolescents’ when examining their pre-treatment and post-treatment scores on the Inhibit scale, Emotional Control scale, Monitor scale, Shift scale, and the Global Executive Composite (GEC) of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function—Self Report (BRIEF-SR).

Second Hypothesis for Study

The second hypothesis was that gender, age, ethnicity, funding type, and previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations will be predictive of EF pre- post-change scores on the Emotional Control scale, Monitor scale, Shift scale, and GEC of the BRIEF-SR. Huizinga and Smidts (2011) found age and gender differences in EFs on the Dutch Version of the BRIEF Parent Report Form as younger children and males tended to exhibit more behavior problems than older children and females. In terms of ethnicity, findings on prevalence rates of DSH have been mixed (Gratz, 2001; Guertin, Lloyd-Richardson, Spirito, Donaldson, & Boergers, 2001; Nock & Mendes, 2008; Zetterqvist, Lundh, Dahlstrom, & Svedin, 2013) which may be indicative of differential EF outcomes. Regarding at-risk youth, James et al. (2015) examined DBT outcomes for adolescents with DSH based on funding type (insurance versus grant-funded) and found improvements in clinical functioning irrespective of funding source. On the other hand, research has demonstrated that low socioeconomic status and not living with both parents in the home are associated with increased risk for adolescent self-harm (Kokkevi et al., 2012). Moreover, children with public or no insurance have decreased access to mental health services (Burnett-Zeigler & Lyons, 2010) yet prior psychiatric hospitalizations (Lloyd-Richardson et al., 2007) are associated with DSH in adolescents. Given that funding type and previous psychiatric hospitalizations may serve as markers for low socioeconomic status, these factors also were considered in the analysis because research suggests that there is an adverse relationship between lower status and neurocognitive functioning for the maturing brain, particularly for EF (Hackman & Farah, 2009). Taken together, gender, age, ethnicity, funding type, and previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations may all potentially impact EF outcomes and were included as variables of interest.

Method

Sample

Participants were selected from a de-identified dataset of adolescents who attended an intensive outpatient program for adolescent DSH at a major university treatment facility in Southern California. Information on clinical outcomes from this single group pre-post study was compiled into that dataset for quality assurance analysis. Referral sources for the program included behavioral health departments, private practices, and self-referrals. Adolescents between the ages of 12–18 were admitted to the program if they endorsed symptoms of emotion dysregulation, behavioral problems, and a current or recent history of DSH (within the last year) during the clinical intake interview. Parents of adolescents also had to be willing to participate in DBT as well. Additionally, adolescents either had private insurance or were grant-funded in order to provide DBT services to patients with public insurance or patients who would have qualified for public insurance based on family income level.

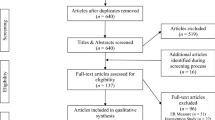

One hundred and sixty-three adolescents were selected from the larger database of 260 participants based on if they were no longer attending the program as of December 31, 2014 and graduated from the program. Graduates were defined as adolescents who completed at least 30 or more sessions and/or were deemed clinically appropriate to be successfully discharged from the program. Of these remaining adolescents, this archival study reported on 93 individuals who completed the BRIEF-SR at pre-treatment and at post-treatment (see Fig. 1). However, there were no significant differences for gender, age, ethnicity, funding type, previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations, or treatment days (p > .05) between the current participants and the remaining 70 adolescents who graduated but did not complete the BRIEF-SR at pre-treatment and/or post-treatment (see Table 1).

For our study, there was no standardized measure of self-harm that was used to assess frequency, severity, or types of DSH at that point in time, as the program’s initial focus in the beginning stages was to successfully employ DBT and examine clinical changes in other areas which included outcomes for EF. Nonetheless, based on clinical assessment from the providers, frequency of self-harm typically ranged from at least once per week to multiples times per day with the duration of self-injury being variable as well. In terms of types of self-harm, the behaviors were varied and encompassed many of those reported in the DSH literature. The most common self-harming behaviors included cutting with razors, fingernail scratching, erasers burns, burning oneself with salt and ice, scolding oneself with hot water, shocking oneself, hitting oneself, and punching walls. Moreover, the after effects of these behaviors existed on a spectrum ranging from non-lethal (e.g., superficial cuts to skin from fingernail scratching) to potentially lethal (e.g., self-injury from knives that required an ER visit and medical treatment such as stapling of the wounds). Regarding psychiatric comorbidities, 95% of the adolescents had a primary diagnosis of major depression.

Self-Report Measure of Executive Functioning

To our knowledge no DBT studies to date have utilized the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function—Self Report (BRIEF-SR) as an outcome measure, which makes our study novel in that regard. This measure was selected to be a part of a quality assurance outcome analysis for the DBT program at the clinical facility and was completed at pre-treatment and post-treatment by adolescents. This face-valid measure provides a self-report of adolescents’ own perception of their EFs in their daily environment (Guy, Isquith, & Gioia, 2004). The BRIEF-SR was intended to measure EFs for children and adolescents 11–18 years of age that can read at a 5th grade reading level or higher (Guy et al., 2004). The 80-item, face-valid measure has a composite score, two indices, and eight non-overlapping clinical scales, which are used to measure various aspects of EFs (Guy et al., 2004). In addition, there are Inconsistency and Negativity scales, which serve as the validity measures (Guy et al., 2004).

The eight clinical scales measure inhibition, shifting, emotional control, monitoring, working memory, planning and organizing, organization of materials, and task completion (Guy et al., 2004). The Inhibit Scale “assesses inhibitory control (i.e., the ability to inhibit, resist, or not act on impulse) and ability to stop one’s own behavior,” while the Shift scale “assesses the ability to move freely from one situation, activity, or aspect of a problem to another, as the circumstances demand” (Guy et al., 2004). The Emotional Control Scale “addresses the manifestation of EFs within the emotional realm and assesses an adolescent’s ability to modulate emotional responses” (Guy et al., 2004). The Monitor Scale “measures a personal self-monitoring function—the extent to which the adolescent keeps track of the effect that his or her behavior has on others,” while the Working Memory Scale “measures the capacity to actively hold information in mind for the purpose of completing a task or generating a response” (Guy et al., 2004). The Plan/Organize Scale “assesses the adolescent’s ability to manage current and future-oriented task demands within a situational context” (Guy et al., 2004). On the other hand, the Organization of Materials Scale “assesses organization in the adolescent’s everyday environment with respect to orderliness of work, play, and storage spaces,” while the Task Completion Scale “assesses the adolescent’s ability to finish or complete tasks appropriately and/or in a timely manner” (Guy et al., 2004).

The two indices are comprised of the Behavioral Regulation Index and Metacognition Index. The Behavioral Regulation Index measures an adolescent’s “ability to maintain appropriate regulatory control of his or her behavior and emotional responses” (Guy et al., 2004). This index consists of the Inhibit, Shift, Emotional Control, and Monitor Scales. The Metacognition Index “assesses the ability to systematically solve problems via planning and organization while sustaining these task completion efforts in active working memory” (Guy et al., 2004). This index consists of the Working Memory, Plan/Organize, Organization of Materials, and Task Completion Scales.

Lastly, the Global Executive Composite (GEC) is the overall executive dysfunction summary score derived from the Behavioral Regulation and Metacognition Indices, which is used to measure the behavioral and cognitive aspects of EFs (Guy et al., 2004). The BRIEF-SR is based on a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 where scores at or above 65 are considered clinically significant and are indicative of difficulties in a particular domain of EF. Scores ranging from 60 to 64 are considered as falling in the elevated range, while scores of 59 or lower are considered as falling in the average range. Overall, the BRIEF-SR shows moderate to high internal consistency (α = .72 to .96) across its scales (Guy et al., 2004). For our study, the Inhibit (α = .87), Emotional Control (α = .86), Monitor (α = .73), and Shift (α = .82), scales along with the Global Executive Composite (α = .96) were used to measure executive dysfunction (Guy et al., 2004).

Treatment Protocol

The program is an intensive outpatient treatment for adolescent males and females that engage in DSH. The program utilizes a modified version of DBT developed Miller, Rathus, Linehan, Wetzler, and Leigh (1997). In this 16-week model, an adolescent skills training group, parent skills training group, multifamily skills training group, and individual therapy sessions for each adolescent are a part of the comprehensive DBT treatment. During this program, the core DBT skills of mindfulness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, and “walking the middle path” are taught and reinforced. In the weekly adolescent group, patients develop these skills and other strategies in order to reduce and ultimately stop self-harming patterns of behavior. The other goal of this group is to help adolescents more effectively regulate their emotions in order for them to better tolerate and manage emotional pain and distress.

In the weekly multifamily skills group, adolescents and parents learn the DBT skills together, which allows for parents to develop their skills as an effective coach for their child while also learning strategies for improving family communication. The weekly parent skills training group is focused on helping caregivers develop skills to cope with their possible emotional difficulties, frustration, and guilt associated with parenting adolescents with DSH. More specifically, parents learn about DBT skills and family roles, which in turn provides them with tools and strategies to help prevent negative residual emotional and physical effects from DSH behaviors. In addition, adolescents also meet with their DBT therapist weekly in order to assess their individual progress in the program and to solve their problems. A team of clinicians who mostly received intensive training through Marsha Linehan’s DBT training institute provided the treatment. This interdisciplinary team was comprised of licensed professionals including a board certified psychiatrist, psychologist, marriage and family therapists, and clinical social workers. Pre-licensed staff and trainees included individuals in the fields of psychology, social work, marriage and family therapy as well as professional counseling. They obtained training through weekly supervision with the intensively trained licensed providers and on an as needed basis.

As previously mentioned, the DBT program was a modified version of Miller’s model. This was due to the limited resources and demands of the treatment facility. As a result, telephone consultations could not be provided to adolescents and parents. This is important to note because in the same way parents learn to coach their children and remind them of the DBT skills in order to manage their emotions, the consultations also serve to reinforce these skills for both adolescents and parents.

Another modification was that adolescents were not required to enter the DBT program at the mindfulness module. This again was due to the nature of the outpatient facility and the referral process where the focus is on helping the adolescents receive treatment as opposed to a more research-focused institution where there is a heightened emphasis on research design. In addition, there were supplemental adolescent and parent support groups structured from other adolescent programs at the site. The adolescent group included music and art therapy, while the parent group was educational with regards to discussing the concepts of DBT and parenting issues. With regard to the BRIEF-SR, this questionnaire was filled out by adolescents at pre-treatment and at post-treatment at the end of 16 weeks and was scored by doctoral graduate psychology students.

Analysis of the Data

Paired t-test analyses were performed to examine changes in EF dysfunction from pre-treatment to post-treatment for the Inhibit scale, Emotional Control scale, Monitor scale, Shift scale, and GEC. The Bonferroni correction method was used to correct for multiple t-tests with a new alpha criterion of .01. In terms of demographic factors, a preliminary bivariate correlational analysis was performed with gender, age, ethnicity, previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations, and funding type with the Inhibit scale, Emotional Control scale, Shift scale, Monitor scale, and the GEC. Assumptions for normality were met and there was also no multicollinearity among predictors. The significant correlations were then used to build four linear regression models with these factors as predictors of EF change scores. From a clinical perspective, this approach was used to explore the profile of adolescents who changed over the course of DBT on a practical level in order to inform our treatment. For the correlational and regression analyses, ethnicity was collapsed into two categories (Caucasian and other ethnicity groups combined) due to small cell sizes in non-white ethnicity groups.

Results

Paired T-Test Analyses

There was a statistically significant improvement in scores from the elevated range to the non-clinical range for the Emotional Control scale from pre-treatment (M = 63.86, SD = 12.37) to post-treatment (M = 55.67, SD = 12.47), 95% CI [5.76, 10.63], t (92) = 6.69, p < .01, d = .69, Shift scale from pre-treatment (M = 61.54, SD = 13.76) to post-treatment (M = 54.23, SD = 13.55), 95% CI [4.54, 10.09], t (92) = 5.24, p < .01, d = .54, Monitor scale from pre-treatment (M = 60.08, SD = 13.44) to post-treatment (M = 51.35, SD = 12.16), 95% CI [5.69, 11.75], t (92) = 5.71, p < .01, d = .59, and GEC from pre-treatment (M = 64.25, SD = 15.47) to post-treatment (M = 55.40, SD = 14.95), 95% CI [5.92, 11.78], t (92) = 6.01, p < .01, d = 62. Although there was a statistically significant reduction on the Inhibit scale from pre-treatment (M = 57.89, SD = 14.00) to post-treatment (M = 52.72, SD = 11.99), 95% CI [2.60, 7.75], t (92) = 3.99, p < .01, d = .41, adolescents’ scores were already in the non-clinical range entering treatment (see Table 2).

Linear Regression Analyses

There was a significant correlation between previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations and the Emotional Control Scale (r = − .23, p < .05) as the first regression model utilized these variables. The results indicated that approximately 5.0% of the proportion of variance on the Emotional Control scale change scores was accounted for by previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations and this proportion was significant [R2 = .05, adjusted R2 = .04, F(1, 91) = 5.03, p < .05]. On average, adolescents with no previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations had a pre-post change score that was 5.66 points higher than adolescents with one or more previous psychiatric hospitalizations on the Emotional Control scale (b = − 5.66, 95% CI [− 10.67, − .65], β = − .23, t(91) = − 2.24, p < .05). Adolescents without a previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations experienced a greater magnitude of change over the course of DBT treatment when compared to adolescents with a previous history of hospitalizations in regards to their emotion regulation.

As there were significant correlations with both funding type (r = − .23, p < .05) and ethnicity (r = − .22, p < .05) on the Shift scale change scores, the second model was performed using the stepwise regression method with these demographic factors. This approach was utilized as neither of these variables was viewed as more important than the other conceptually or in the research literature for predicting shifting skills. The results demonstrated that after the effect of funding type was accounted for ethnicity did not significantly add to the model and was excluded from the analysis. Approximately 5.0% of the proportion of variance on the Shift scale change scores was accounted for by funding type and this proportion was significant [R2 = .05, adjusted R2 = .04, F(1, 91) = 5.18, p < .05]. On average, grant-funded adolescents had a pre-post change score that was 6.35 points higher than insurance-funded adolescents on the Shift scale. (b = − 6.35, 95% CI [− 11.89, − .81], β = − .23, t(91) = − 2.25, p < .05). Grant-funded adolescents experienced a greater magnitude of change over the course of DBT treatment when compared to insurance-funded adolescents in regards to their shifting skills.

In order to assess the relationship between funding type (r = − .23, p < .05) and the Monitor scale (r = − .28, p < .01) and GEC change scores, two simple linear regressions were conducted. The results showed that approximately 8.0% of the proportion of variance on the Monitor scale change scores was accounted for by funding type and this proportion was significant [R2 = .08, adjusted R2 = .07, F(1, 91) = 7.54, p < .01]. On average, grant-funded adolescents had a pre-post change score that was 8.27 points higher than insurance-funded adolescents on the Monitor Scale (b = − 8.27, 95% CI [− 14.26, − 2.29], β = − .27, t(91) = − 2.75, p < .05). Grant-funded adolescents experienced a greater magnitude of change over the course of DBT treatment when compared to insurance-funded adolescents in regards to their interpersonal functioning. Additionally, the results indicated that approximately 5.0% of the proportion of variance on the GEC change scores was accounted for by funding type and this proportion was significant [R2 = .05, adjusted R2 = .04, F(1, 91) = 4.91, p < .05]. On average, grant-funded adolescents had a pre-post change score that was 6.53 points higher than insurance-funded adolescents on the GEC (b = − 6.53, 95% CI [− 12.39, − .68], β = − .23, t(91) = − 2.22, p < .05). Grant-funded adolescents experienced a greater magnitude of change over the course of DBT treatment when compared to insurance-funded adolescents in regards to their overall executive functioning. Lastly, age and gender were not observed to have any correlations with the EF variables and were not included in the regression analyses.

Discussion

Changes in Pre-treatment and Post-treatment Functioning

The pre-treatment to post-treatment EF analysis provided a neuropsychological treatment profile for clinicians and researchers. Because the BRIEF-SR has not been researched with this population to our knowledge, this analysis provided a subjective view of changes in EFs that are used in these adolescents’ everyday environment. The next step in research is to add a control group and/or comparison therapy group with random assignment and then determine the relative contribution of each DBT skill (mindfulness, emotion regulation, distress tolerance, interpersonal effectiveness, and walking the middle path) to each specific EF. This will help clarify the direct role of each DBT skill in the course of treatment. After these relationships have been established, additional scales and composites on the BRIEF-SR such as Working Memory, Plan/Organize, Organization of Materials, Task Completion, Metacognition Index, and the Behavioral Regulation Index, should be included to determine if and how DBT skills help improve these areas of EFs.

With respect to our current study, adolescents with DSH entering DBT endorsed more EF dysfunction on the BRIEF-SR that was largely more severe than adolescents with anorexia nervosa (Dahlgren, Lask, Landro, & Ro, 2014) as well as adolescents with traumatic brain injury (Byerley & Donders, 2013; Wilson, Donders, & Nguyen, 2011), epilepsy (Slick, Lautzenhiser, Sherman, & Eyrl, 2006), spina bifida (Zabel et al., 2011), and specific language impairment (Hughes, Turkstra, & Wulfeck, 2009). This pre-treatment profile was characterized by impairments with emotion regulation, shifting, interpersonal functioning, and overall executive functioning and with inhibition below clinical levels. Knowledge of these pre-treatment deficits is important for clinical practice because this will allow clinicians to tailor treatment to specific DBT skills. For example, emphasis should be placed on presenting the DBT skills of emotion regulation, distress tolerance, and interpersonal effectiveness throughout therapy since they directly map on to treating the specific problem areas of emotion dysregulation, shifting, and interpersonal functioning in these adolescents with DSH.

The post-treatment profile was characterized by meaningful improvements from the elevated to non-clinical range for emotion regulation, shifting, interpersonal functioning, and overall executive functioning, as there was a moderate effect size when analyzing changes in these areas. Problems with inhibition were also maintained below clinical levels and there was a small effect size for this change when examining pre-treatment to post-treatment functioning. Taken together, these improvements surpassed changes observed in adolescents with severe psychopathology such as those with anorexia nervosa enrolled in cognitive remediation therapy that also reported EF dysfunction on the BRIEF-SR (Dahlgren et al., 2014). Awareness of this trajectory will allow clinicians to better gauge what kind of changes in EFs to expect by the end of DBT. This will also allow clinicians to better inform adolescents with DSH and their parents about potential improvements in EFs and possibly instill hope and commitment among them for DBT before starting treatment. Additionally, the neuropsychological treatment profile from the BRIEF-SR should be used in future DBT outcome studies that utilize neuroimaging and other neuropsychological measures to analyze brain-behavior relationships in the context of EFs. This combined approach will provide researchers with not only a neurobiological and an objective, neuropsychological view of EFs, but also with these adolescents’ unique, self-perception of EFs in their daily lives. This will allow for a more complete viewpoint of changes. Because of the adolescent’s brain plasticity (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006) and cognitive-based interventions that have been shown to positively affect neural activation (Goldin et al., 2014; Kumari et al., 2011) and structure (Penades et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2013), this future research can assess if the self-reported changes in EFs from DBT correlate with changes in brain structure, neural activation, and with improvement on objective neuropsychological testing of EFs during this critical period of neural development.

Impact of Demographic Factors

The regression analyses provided specific neuropsychological treatment profiles of pre-post EF change scores for two demographic groups. Although adolescents with DSH as a collective group improved from the elevated to non-clinical range, those without a previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations had greater change scores in emotion regulation over the course DBT. Likewise, grant-funded adolescents had greater change scores in shifting, interpersonal functioning, and overall executive functioning over the course DBT. However, these small but significant effects did not result in a great deal of variance. As a result, the next step in research is to continue to explore for factors that may better explain these relationships. Despite the relatively small proportion of variance attributed to these factors, researchers and clinicians should incorporate this demographic information from intake and screening measures before the start of DBT as lack of exposure to psychiatric services (Berghofer, Schmidl, Rudas, Steiner, & Schmitz, 2002; Morlino, Martucci, Musella, Bolzan, & de Girolamo, 1995) and disadvantaged socioeconomic background (James et al., 2015) have been associated with treatment dropout. This will allow for the identification of adolescents from these at-risk groups at the start of DBT who may excel in the development of particular EFs.

Next, a treatment plan should be formulated to determine the usage of skills, respectively. For example, adolescents without a previous history of psychiatric hospitalizations may differentially benefit from the increased usage of the DBT skill of emotion regulation. Additionally, grant-funded adolescents may differentially benefit from the increased usage of the DBT skills of distress tolerance and interpersonal effectiveness. Using this information to identify these high-risk groups may also result in improved outcomes like in other early psychological intervention programs with adolescents with borderline personality disorder (Chanen et al., 2008). From a policy perspective, these findings also highlight the importance of funding and advocacy for high-risk adolescents with DSH, as the grant-funded children in our study may not have otherwise received treatment despite these benefits in executive functioning. This is of particular importance because research suggests that lower socioeconomic status is a risk factor for poorer executive functioning with respect to the developing brain (Hackman & Farah, 2009).

Limitations

Because this was a naturalistic clinical study with program evaluation data, the design did not include random assignment or a control or comparison group. As a result, the changes in EF could be impacted by regression to the mean, nonspecific therapeutic effects, or maturation of the adolescents over the course of the 16-week DBT program. However, this type of research design is consistent with most DBT effectiveness studies with DSH adolescents when measuring pre-treatment to post-treatment changes in a clinical setting (Goldstein, Axelson, Birmaher, & Brent, 2007; James et al., 2008; James et al., 2011). Second, another limitation was the sample composition as the majority of adolescents were female which was consistent with previous DBT studies (James et al., 2011; James et al., 2015; McDonell et al., 2010; Mehlum et al., 2014; Uliaszek, Wilson, Mayberry, Cox, & Maslar, 2013). However, this may have affected power to detect differences on EF change scores with respect to gender. Additionally, the majority of the sample was comprised of Caucasian females, which may affect the potential external validity of this study for non-Caucasian, non-female adolescents with DSH.

Third, only 93 adolescents out of the 163 graduates were included in the analyses, limiting the conclusions of the study. However, demographic analyses indicated that the study sample was not significantly different from the 70 graduates who did not complete the BRIEF-SR at pre-treatment and/or post-treatment. Therefore, the findings from this study should be generalizable to those DSH adolescents as well. Fourth, the collection of secondary data due to the “real-world” clinical setting with the measurement of EFs at pre-treatment and post-treatment was also a limitation. Because of the limited resources and demands of the clinical setting for administering the BRIEF-SR, the study only focused on EF outcomes. As a result, the lack of multiple measurement points did not permit the analysis of different types of growth or changes. Another drawback for this study was the use of a single self-report measure of EF. Using more objective neuropsychological measures in combination with this subjective measure in the future would potentially provide a richer clinical profile of adolescents’ EFs during DBT.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Berghofer, G., Schmidl, F., Rudas, S., Steiner, E., & Schmitz, M. (2002). Predictors of treatment discontinuity in outpatient mental health care. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 37, 276–282.

Blakemore, S. J., & Choudhury, S. (2006). Development of the adolescent brain: Implications for executive function and social cognition. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 296–312.

Briere, J., & Gill, E. (1998). Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: Prevalence, correlates, and functions. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68, 609–620.

Brunner, R., Henze, R., Parzer, P., Kramer, J., Feigl, N., Lutz, K., … Stieltjes, B. (2010). Reduced prefrontal and orbitofrontal gray matter in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder: Is it disorder specific? Neuroimage, 49, 114–120.

Burnett-Zeigler, I., & Lyons, J. S. (2010). Caregiver factors predicting service utilization among youth participating in a school-based mental health intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 572–578.

Byerley, A. K., & Donders, J. (2013). Clinical utility of the behavior rating inventory of executive function-self-report (BRIEF-SR) in adolescents with traumatic brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 58, 412–421.

Chanen, A. M., Jackson, H. J., McCutcheon, L. K., Jovev, M., Dudgeon, P., Yuen, H. P., … McGorry, P. D. (2008). Early intervention for adolescents with borderline personality disorder using cognitive analytic therapy: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 193, 477–484.

Choate, L. H. (2012). Counseling adolescents who engage in nonsuicidal self-injury: A dialectical behavior therapy approach. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 34(1), 56–70.

Cipriano, A., Cella, S., & Cotrufo, P. (2017). Nonsuicidal self-injury: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–14.

Dahlgren, C. L., Lask, B., Landro, N. I., & Ro, O. (2014). Patient and parental self-reports of executive functioning in a sample of young female adolescents with anorexia nervosa before and after cognitive remediation therapy. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(1), 45–52.

De Pisapia, N., Serra, M., Rigo, P., Jager, J., Papinutto, N., Esposito, G., … Bornstein, M. H. (2014). Interpersonal competence in young adulthood and right laterality in white matter. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 26, 1257–1265.

Ezekiel, F., Bosma, R., & Morton, J. B. (2013). Dimensional change card sort performance associated with age-related differences in functional connectivity of lateral prefrontal cortex. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 5, 40–50.

Fleischhaker, C., Böhme, R., Sixt, B., Brück, C., Schneider, C., & Schulz, E. (2011). Dialectical behavioral therapy for adolescents (DBT-A): A clinical trial for patients with suicidal and self-injurious behavior and borderline symptoms with a one-year follow-up. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 5(3), 1–10.

Goldin, P. R., Ziv, M., Jazaieri, H., Weeks, J., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2014). Impact of cognitive behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder on the neural bases of emotional reactivity to and regulation of social evaluation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 62, 97–106.

Goldstein, T. R., Axelson, D. A., Birmaher, B., & Brent, D. A. (2007). Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with bipolar disorder: A 1-year open trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 820–830.

Gratz, K. L. (2001). Measurement of deliberate self harm. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23, 253–263.

Guertin, T., Lloyd-Richardson, E., Spirito, A., Donaldson, D., & Boergers, J. (2001). Self-mutilative behavior in adolescents who attempt suicide by overdose. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 1062–1069.

Guy, S. C., Isquith, P. K., & Gioia, G. A. (2004). Behavior rating inventory of executive function–self-report version. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Hackman, D. A., & Farah, M. J. (2009). Socioeconomic status and the developing brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13, 65–73.

Hawton, K., Witt, K. G., Salisbury, T. L., Arensman, E., Gunnell, D., Townsend, E., … Hazell, P., (2015). Interventions for self-harm in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12), 1–89.

Hughes, D., Turkstra, L., & Wulfeck, B. (2009). Parent and self-ratings of executive function in adolescents with specific language impairment. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 44, 901–916.

Huizinga, M., & Smidts, D. P. (2011). Age-related changes in executive function: A normative study with the Dutch version of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF). Child Neuropsychology, 17, 51–66.

James, A. C., Taylor, A., Winmill, L., & Alfoadari, K. (2008). A preliminary community study of dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) with adolescent females demonstrating persistent, deliberate self-harm (DSH). Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13, 148–152.

James, A. C., Winmill, L., Anderson, C., & Alfoadari, K. (2011). A preliminary study of an extension of a community dialectic behaviour therapy (DBT) programme to adolescents in the looked after care system. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 16, 9–13.

James, S., Freeman, K. R., Mayo, D., Riggs, M. L., Morgan, J. P., Schaepper, M. A., & Montgomery, S. B. (2015). Does insurance matter? Implementing dialectical behavior therapy with two groups of youth engaged in deliberate self-harm. Adminstration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42, 449–461.

Katz, L. Y., Cox, B. J., Gunasekara, S., & Miller, A. L. (2004). Feasibility of dialectical behavior therapy for suicidal adolescent inpatients. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 276–282.

Kerr, P. L., Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Turner, J. M. (2010). Nonsuicidal self-injury: A review of current research for family medicine and primary care physicians. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 23, 240–259.

Kokkevi, A., Rotsika, V., Arapaki, A., & Richardson, C. (2012). Adolescents’ self-reported suicide attempts, self-harm thoughts and their correlates across 17 European countries. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 381–389.

Kumari, V., Fannon, D., Peters, E. R., Ffytche, D. H., Sumich, A. L., Prekumar, P., … Kuipers, E. (2011). Neural changes following cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis: A longitudinal study. Brain, 134, 2396–2407.

Lalonde, G., Henry, M., Germain, A., Nolin, P., & Beauchamp, M. H. (2013). Assessment of executive function in adolescence: A comparison of traditional and virtual reality tools. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 219(1), 76–82.

Latimer, S., Meade, T., & Tennant, A. (2013). Measuring engagement in deliberate self-harm behaviours: Psychometric evaluation of six scales. BioMed Central Psychiatry, 13(4), 1–11.

Lauw, M., How, C. H., & Loh, C. (2015). Deliberate self-harm in adolescents. Singapore Medical Journal, 56, 306–309.

Linehan, M. M., Comtois, K. A., Murray, A. M., Brown, M. Z., Gallop, R. J., Heard, H. L., … Lindenboim, N. (2006). Two-year randomized controlled trial and follow-up of dialectical behavior therapy vs therapy by experts for suicidal behaviors and borderline personality disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 757–766.

Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., Perrine, N., Dieker, L., & Kelley, M. L. (2007). Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 37, 1183–1192.

Madge, N., Hawton, K., McMahon, E. M., Corcoran, P., De Leo, D., de Wilde, E. J., … Arensman, E. (2011). Psychological characteristics, stressful life events and deliberate self-harm: Findings from the Child & Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20, 499–508.

Maier-Hein, K. H., Brunner, R., Lutz, K., Henze, R., Parzer, P., Feigl, N., … Stieltjes, B. (2014). Disorder-specific white matter alterations in adolescent borderline personality disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 75, 81–88.

Marsh, R., Zhu, H., Schultz, R. T., Quackenbush, G., Royal, J., Skudlarski, P., & Peterson, B. S. (2006). A developmental fMRI study of self-regulatory control. Human Brain Mapping, 27, 848–863.

Masten, C. L., Eisenberger, N. I., Borofsky, L. A., Pfeifer, J. H., McNealy, K., Mazziotta, J. C., & Dapretto, M. (2009). Neural correlates of social exclusion during adolescence: Understanding the distress of peer rejection. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 4, 143–157.

McDonell, M. G., Tarantino, J., Dubose, A. P., Matestic, P., Steinmetz, K., Galbreath, H., & McClellan, J. M. (2010). A pilot evaluation of dialectical behavioural therapy in adolescent long-term inpatient care. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 15, 193–196.

McRae, K., Gross, J., Weber, J., Robertson, E., Sokol-Hessner, P., Ray, R., … Ochsner, K. N. (2011). The development of emotion regulation: An fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal in children, adolescents and young adults. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 7, 11–22.

Mehlum, L., Tormoen, A. J., Ramberg, M., Haga, E., Diep, L. M., Laberg, S., … Groholt, B. (2014). Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: A randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 53, 1082–1091.

Mikolajczak, M., Petrides, K., & Hurry, J. (2009). Adolescents choosing self-harm as an emotion regulation strategy: The protective role of trait emotional intelligence. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 48, 181–193.

Miller, A. L., Rathus, J. H., Linehan, M. M., Wetzler, S., & Leigh, E. (1997). Dialectical behavior therapy adapted for suicidal adolescents. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 3, 78.

Moor, B. G., Guroglu, B., Op de Macks, Z. A., Rombouts, S. A., Van der Molen, M. W., & Crone, E. A. (2012). Social exclusion and punishment of excluders: Neural correlates and developmental trajectories. Neuroimage, 59, 708–717.

Morlino, M., Martucci, G., Musella, V., Bolzan, M., & de Girolamo, G. (1995). Patients dropping out of treatment in Italy. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 92(1), 1–6.

Morton, J. B., Bosma, R., & Ansari, D. (2009). Age-related changes in brain activation associated with dimensional shifts of attention: An fMRI study. Neuroimage, 46, 249–256.

New, A. S., Carpenter, D. M., Perez-Rodriguez, M. M., Ripoll, L. H., Avedon, J., Patil, U., … Goodman, M. (2013). Developmental differences in diffusion tensor imaging parameters in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47, 1101–1109.

Nock, M. K., & Mendes, W. B. (2008). Physiological arousal, distress tolerance, and social problem—solving deficits among adolescent self-injurers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 28–38.

Paris, J., Zelkowitz, P., Guzder, J., Joseph, S., & Feldman, R. (1999). Neuropsychological factors associated with borderline pathology in children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 770–774.

Penades, R., Pujol, N., Catalan, R., Massana, G., Rametti, G., Garcia-Rizo, C., … Junque, C. (2013). Brain effects of cognitive remediation therapy in schizophrenia: A structural and functional neuroimaging study. Biological Psychiatry, 73, 1015–1023.

Pitskel, N. B., Bolling, D. Z., Kaiser, M. D., Crowley, M. J., & Pelphrey, K. A. (2011). How grossed out are you? The neural bases of emotion regulation from childhood to adolescence. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 1, 324–337.

Plener, P. L., Schumacher, T. S., Munz, L. M., & Groschwitz, R. C. (2015). The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: A systematic review of the literature. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 2(2), 1–11.

Richter, J., Brunner, R., Parzer, P., Resch, F., Stieltjes, B., & Henze, R. (2014). Reduced cortical and subcortical volumes in female adolescents with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 221, 179–186.

Rubia, K., Smith, A. B., Woolley, J., Nosarti, C., Heyman, I., Taylor, E., & Brammer, M. (2006). Progressive increase of frontostriatal brain activation from childhood to adulthood during event-related tasks of cognitive control. Human Brain Mapping, 27, 973–993.

Seghete, K. L., Herting, M. M., & Nagel, B. J. (2013). White matter microstructure correlates of inhibition and task-switching in adolescents. Brain Research, 1527, 15–28.

Shaw, P., Greenstein, D., Lerch, J., Clasen, L., Lenroot, R., Gogtay, N., … Giedd, J. (2006). Intellectual ability and cortical development in children and adolescents. Nature, 440, 676–679.

Slick, D. J., Lautzenhiser, A., Sherman, E. M., & Eyrl, K. (2006). Frequency of scale elevations and factor structure of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) in children and adolescents with intractable epilepsy. Child Neuropsychology, 12, 181–189.

Sunseri, P. A. (2004). Preliminary outcomes on the use of dialectical behavior therapy to reduce hospitalization among adolescents in residential care. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 21(4), 59–76.

Tamm, L., Menon, V., & Reiss, A. L. (2002). Maturation of brain function associated with response inhibition. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 1231–1237.

Uliaszek, A. A., Wilson, S., Mayberry, M., Cox, K., & Maslar, M. (2013). A Pilot intervention of multifamily dialectical behavior group therapy in a treatment-seeking adolescent population: Effects on teens and their family members. The Family Journal, 22, 206–215.

Vijayakumar, N., Whittle, S., Yucel, M., Dennison, M., Simmons, J., & Allen, N. B. (2014). Thinning of the lateral prefrontal cortex during adolescence predicts emotion regulation in females. Social Cognitive Affective Neuroscience, 9, 1845–1854.

Wang, T., Huang, X., Huang, P., Li, D., Lv, F., Zhang, Y., … Xie, P. (2013). Early-stage psychotherapy produces elevated frontal white matter integrity in adult major depressive disorder. PLoS ONE. 8(4), e63081.

Wilson, K. R., Donders, J., & Nguyen, L. (2011). Self and parent ratings of executive functioning after adolescent traumatic brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 56, 100–106.

You, J., Leung, F., & Fu, K. (2012). Exploring the reciprocal relations between nonsuicidal self-injury, negative emotions and relationship problems in Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal cross-lag study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40, 829–836.

Zabel, T. A., Jacobson, L. A., Zachik, C., Levey, E., Kinsman, S., & Mahone, E. M. (2011). Parent- and self-ratings of executive functions in adolescents and young adults with spina bifida. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 25, 926–941.

Zetterqvist, M., Lundh, L. G., Dahlstrom, O., & Svedin, C. G. (2013). Prevalence and function of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a community sample of adolescents, using suggested DSM-5 criteria for a potential NSSI disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41, 759–773.

Funding

This study was funded in part by NIMH Grant K01 MH077732-01A1 (PI: S. James) and UniHealth Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

The university’s Institutional Review Board approved analysis of the de-identified data that had been collected and maintained as part of quality assurance. All patients signed a treatment consent that included a statement that their de-identified information may be used for research.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, A., Freeman, K., Montgomery, S. et al. Executive Functioning Outcomes Among Adolescents Receiving Dialectical Behavior Therapy. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 36, 495–506 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0578-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0578-9