Abstract

This study examines the correlations of adolescents’ self-esteem, loneliness and depression with their internet use behaviors with a sample of 665 adolescents from seven secondary schools in Hong Kong. The results suggest that frequent online gaming is more strongly correlated to internet addiction and such correlation is higher than other predictors of internet addiction in online behaviors including social interactions or viewing of pornographic materials. Male adolescents tend to spend more time on online gaming than female counterparts. In terms of the effect of internet addiction on adolescents’ psychological well-being, self-esteem is negatively correlated with internet addiction, whereas depression and loneliness are positively correlated with internet addiction. Comparatively, depression had stronger correlation with internet addiction than loneliness or self-esteem. A standardized definition and assessment tool for identifying internet addiction appears to be an unmet need. Findings from this study provide insights for social workers and teachers on designing preventive programs for adolescents susceptible to internet addiction, as well as emotional disturbance arising from internet addiction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The internet has become a community where we engage in social interactions, information exchange and entertainment. Internet access is now available at a wide variety of places, such as homes, schools, public areas and internet cafes; thus, adolescents are a particularly vulnerable group. Despite the benefits of the internet, one outstanding risk is the development of internet dependence. Studies have revealed an increasing trend; adolescents’ use of the internet may create negative problems related to internet risk and psychological dysfunction (Leung & Lee, 2012a; Livingstone & Helsper, 2007; Murali & Geonrge, 2007). Recent review on problematic internet use (PIU) has suggested its profound impact on wellbeing, interpersonal relationships and daily functioning among adolescents (Anderson, Steen, & Stavropoulos, 2017).

When the term “internet addiction” (IA) first emerged in the late 1990s, Young (1998a, p. 237) defined it as “an impulse-control disorder that does not involve an intoxicant.” Young (2015) further developed a diagnostic questionnaire for IA by adopting the criterion for pathological gambling in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV (DSM-IV) issued by the American Psychiatric Association, attracting the interest of the global research community in investigations on the effects of IA (Yellowlees & Marks, 2007). These studies have alerted the public to the potential seriousness of IA. Recent research on internet addiction or problematic internet use over the past two decades suggested increasing concerns of internet use and its potential negative impact on children and adolescents (Young, 2017).

This paper examined how adolescents’ psychological well-being is related to their internet use behaviors. In particular, this study focused on self-esteem, loneliness and depression as potential factors of psychological well-being that affect adolescents’ internet use. The internet use behaviors investigated here include most common internet activities, time spent on the internet and the settings in which it is used most frequently. In other words, this paper indicated the antecedents of internet over-use rather than its effects. Adolescents’ states of well-being that may lead to excessive internet use should be identified and highlighted. Key findings of this research are discussed with practical and policy implications. Finally, recommendations for future research are provided.

Literature Review

Due to advanced technology in mobile devices and wireless broadband services, the internet has become more accessible, affordable and informative than ever before. The internet is a community where we experience social interaction, information exchange and entertainment. Internet access is now available at different places such as homes, schools, public areas and internet cafes, making adolescents the most vulnerable group (Ferraro, Caci, D’Amico, & Blasi, 2007). Studies have revealed an increasing trend of adolescents’ internet use in Hong Kong (Breakthrough, 2010) as well as the problematic issues surrounding internet use (Leung & Lee, 2012a, b; Livingstone & Helsper, 2007; Murali & Geonrge, 2007), including the risk of psychological dysfunction (Ceyhan & Ceyhan, 2008).

Previous studies have identified self-esteem, loneliness and depression as factors of psychological well-being that may be correlated with levels of motivation to use the internet in specific ways (excluding external forces, such as routine work and study) and IA. For example, levels of self-esteem are lower in people with an online gaming dependency than those in non-dependent individuals (Schmit, Chauchard, Chabrol, & Sejourne, 2011). Internet usage on social networking sites such as Facebook has become increasingly common in daily life. Social workers are confronted with new challenges regarding cyber youth work (Chan & Holosko, 2016a; Cheung, 2016; Leung et al., 2017). The positive feedback gained from peers when using social networking sites can enhance adolescents’ self-esteem and well-being (Wang, Jackson, Zhang, & Su, 2012). Positive feedback reflects a greater motivation for adolescents to use the internet when they would desire to improve their self-esteem (Israelashvili, Kim, & Bukobza, 2012).

Loneliness and depression, negative psychological well-being conditions, have been identified as distal antecedents to IA (Davis, 2001). According to Kim, Larose, and Peng (2009), adolescents who were lonely tended to develop strong IA behaviors that led to increased loneliness. Moreover, depression is a major cause of IA in adolescents (Ha et al., 2007). According to a recent study in Taiwan, the presence of more depressive symptoms, a greater expectation of positive outcomes from internet use, a greater internet usage time, a lower refusal self-efficacy of internet use, higher impulsivity, lower satisfaction with academic performance, and an insecure attachment style were all positively correlated with IA (Lin, Ko, & Wu, 2011).

Furthermore, the ways in which adolescents most frequently use the internet have been found to have important consequences related to psychological well-being (Chen, 2012; Gordon, Juang, & Syed, 2007; Gross, Juvonen, & Gable, 2002). Internet activities may be classified into different purposes, such as social interactions, entertainment, information exchange and online shopping. Online chatting and online gaming were previously shown to be more crucial in determining IA than other internet activities (Chou, Condron, & Belland, 2005); furthermore, entertainment usage was more likely to result in psychological problems than social usage (Kim et al., 2009). Based on the results from another study in Korea, college students who use smartphones for bonding and sharing a sense of support are likely to show higher levels of self-esteem and lower levels of loneliness and depression (Park & Lee, 2012). The use of facebook has been shown to have a positive effect on young users’ abilities to fulfill enduring human psychosocial needs for permanent relationships, in which larger networks and estimated audiences predicted higher levels of life satisfaction and perceived social support (Manago, Taylor, & Greenfield, 2012).

Gender differences have been observed in the behavioral patterns and addictive behaviors of internet use (Bukstein, Glancy, & Kaminer, 1992). For example, gender differences were reported in the correlation between psychological well-being and internet use (Hetzel-Riggin & Pritchard, 2011), as females show a stronger correlation between social use and loneliness than males. On the other hand, males display a stronger correlation between leisure use and loneliness than females (Amichai-Hamburger & Ben-Artzi, 2003). More specifically, an older age, lower self-esteem and lower life satisfaction have been associated with a more severe online gaming addiction in males (Ko, Yen, Chen, Chen, & Yen, 2005). Significant differences have been observed regarding IA between gender and type of school attended (Poli & Agrimi, 2012).

Recently, studies on adolescents’ IA in Hong Kong have emerged. Most of these studies have focused on the prevalence and negative impacts of IA on adolescents. Shek and his research team found certain aspects of online activities, such as playing games online and replacing outdoor activities with online games, were more likely to lead to IAs (Shek, Tang, & Lo, 2008). Chang and Law (2008) evaluated Young’s internet Addiction Test (IAT) and found that the degree of IA was highly correlated with different types of internet activity, such as higher IA scores for cyber relationships and online gambling. Another study revealed an association between negative health effects, such as skipping meals and sleeping late, and heavy internet use (Kim et al., 2009). Cheung and Wong (2011) explored the relationship between the effect of IA and mental health problems in adolescents and found that internet addicts tended to have insomnia and depression. In a longitudinal study on the prevalence of IA among early adolescents, Shek and Yu (2011) showed that 26.7% of the participants met the criterion for IA using Young’s IAT. Leung and Lee (2012a) found that adolescent internet addicts in Hong Kong tended to be male, from low-income families, and not confident in internet literacy. They also found that leisure-oriented internet activities, especially for social networking sites (SNS) and online games, were much more addictive than were other internet activities such as email communication or webpage browsing. The higher the perceived social-structural literacy, the better their academic performance would be. They also investigated the influences of information literacy, IA and parenting styles on internet risks (Leung & Lee, 2012b). Gender differences have been reported regarding receiving unpleasant treatment such as harassment and the disclosure of personal or private information by others on the internet. In addition, stricter rules and more involvement and mediation by parents are linked to a lower likelihood of children and adolescents becoming victims of internet risk behaviors.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Secondary school students were the target population in this study. A balanced distribution of genders was used during data collection. A list of secondary schools from the Education Bureau (EDB), excluding international schools, was formulated. Five hundred twenty-four secondary schools were included on the list. Letters were sent to all schools by email to invite them to participate in the study. A self-administered questionnaire was used to collect data. The scope of the questionnaire covered six parts. Different measurement scales were adopted for the first to fourth parts, including the self-esteem scale, loneliness scale, depression scale and IAT. The fifth part examined habits of internet use (HIU), and the last part collected demographic information (Table 1).

Measurement Tools

Chinese Self-esteem Scale (C-SES)

Self-esteem was measured using the ten items of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1965). The assessment of self-esteem using the RSES, a self-report questionnaire, during adolescence is reliable and valid (Bos, Huijding, Muris, Vogel, & Biesheuvel, 2010; Butler & Gasson, 2005). This scale has been used worldwide and has been translated into different languages. The Chinese version used in this study was based on a study assessing the validity and reliability of the Chinese RSES by Leung and Wong (2005), which reported a 0.757 Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. The authors suggested revising some of the wording in the Chinese version reported by Tsang (1997) that is commonly applied in Hong Kong due to an unsatisfactory Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (0.686). The C-SES in this study achieved a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.849.

Chinese Loneliness Scale (C-LS)

The revised UCLA (University of California, Los Angeles) loneliness scale (UCLA Loneliness Scale version 3), a self-report questionnaire, is used to measure college students’ loneliness levels. The scale has adequate psychometric properties, has been extensively validated, and shows high internal consistency, with an alpha coefficient of 0.94 (Russell, 1996). A recent study on the relationship between psychological well-being and internet use adopted Russell’s UCLA Loneliness Scale and achieved high internal consistency, with an alpha coefficient of 0.84 (Kim et al., 2009). The higher the score obtained on the scale, the higher the degree of loneliness. The Chinese version of the questionnaire used in this study was based on a relevant study on loneliness determining internet usage preference (n = 311), which attained a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.88 (Huang, 2007). The C-LS in this study achieved a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.902.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)

Randoff’s (1977) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that was developed to identify depression symptoms or psychological distress in the general population. It was designed to gauge the major components of depression, including a depressed mood, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, feelings of helplessness and worthlessness, psychomotor retardation, loss of appetite, and sleep disorders. This scale has been subjected to numerous validation exercises (Cheung & Bagley, 1998; Corcoran & Fischer, 1987; Radloff & Locke, 1986). The Chinese version of the questionnaire used in this study was based on the study by Cheung and Bagley (1998) and has proven to be a valid, reliable and acceptable tool in predicting suicidal attempts and thoughts. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients ranged between 0.820 and 0.834. The total score ranges from 0 to 60, and a higher score indicates more depressive symptoms. A score of 16 or higher has been used as the cutoff point in many studies to indicate a high level of depression (Radloff, 1977; Shaver & Brennan, 1991). The CES-D in this study achieved a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.907.

Chinese internet Addiction Scale (CIAS)

Young’s IAT (Young, 1998b) and the CIAS (Chen, Weng, Su, Wu, & Yang, 2003) are the most common scales for screening and diagnosing problematic internet use. Previous studies in Hong Kong mainly adopted Young’s IAT as a screening assessment for IA based on the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of pathological gambling. However, the CIAS is a reliable and popular scale for assessing internet use problems in Chinese populations; studies from Taiwan and Mainland China have provided supporting evidence showing that this scale is reliable for revealing the core symptoms of and problems related to IA (Ko, Yen, Chen, Yeh, & Yen, 2009). This study chose the CIAS as the measurement tool to assess adolescents’ IA in Hong Kong because it specifically targets Chinese populations.

This 26-item CIAS (Chen et al., 2003) utilizes a four-point Likert scale to assess five dimensions of problematic internet use. The dimensions include compulsive use, withdrawal, tolerance, interpersonal relationships, health and time management. The internal reliability of the CIAS ranges from 0.79 to 0.93. The higher the score attained, the greater the severity of IA. A total score of 64 was the cutoff point used to classify IA. The CIAS in this study achieved a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.948.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 18.0 was used for statistical analysis in this study. SPSS was used to conduct reliability tests for the instruments and the results of the three scales. Furthermore, correlation analyses and partial correlation analyses were performed to examine the hypotheses. Finally, multiple linear regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of IA and patterns of internet usage.

Result

Respondents Demographics

A total of 665 respondents from seven secondary schools, ranging from Form 1 to Form 6 (equivalent to grade 7 to grade 12 in US), completed the survey and their responses were included in the current analysis. Additional detailed background information for the samples is presented in Table 2.

Hours Spent on the Internet

The mean number of hours spent on the internet was 3.85 per day. Young (2007) suggests that using the internet for 38 h or more each week may result in IA. In this study, 22.7% of respondents reached this threshold.

Analysis of the Correlations Between Adolescents’ Psychological Well-Being Conditions (PWC) and Habits of Internet Use (HIU)

Pearson’s correlation analyses were performed to analyze the relationships between adolescents’ psychological well-being and their internet usage. Based on the results of Pearson’s r analysis, adolescents’ degree of depression was significantly correlated with their use of the internet for social interaction usage (SIU) (r = .097, p < .05) and looking for pornography on the internet, i.e., entertainment usage, pornography (EU2) (r = .174, p < .01), implying that the higher the degree of depression, the more frequent the SIU and EU2. Furthermore, adolescents’ degree of loneliness was also significantly correlated with looking for pornography on the internet (EU2) (r = .087, p < .05), suggesting that the higher the degree of loneliness, the more frequent the EU2.

Analysis of the Correlations Between Adolescents’ HIU and IA

According to the results of Pearson’s r analysis, IA was significantly associated with adolescents’ HIU, including SIU (r = .108, p < .01), online gaming (r = .311, p < .01) and looking for pornography (r = .208, p < .01), suggesting that frequent engagement in the above HIU result in a greater extent of IA (Table 3).

Analysis of the Correlations Between Adolescents’ PWC and IA

Based on the results of Pearson’s r analysis, IA was significantly associated with adolescents’ degree of self-esteem (r = − .207, p < .01), loneliness (r = .191, p < .01) and depression (r = .318, p < .01), which implies that a higher degree of self-esteem correlates with a lower extent of IA; similarly, a higher degree of depression or loneliness correlates with a greater extent of IA.

Analysis of the Correlations Between Age and HIU

A Pearson’s r analysis was conducted to investigate the correlations between age groups, HIU and IA. Before performing the analysis, four different age groups were constructed to generate dummy variables. Only adolescents aged 15 to 17 years were significantly correlated with the frequency of using the internet for SIU (r = .116, p < .01) (Table 4).

Predictors of IA and Patterns of Internet Usage

Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of IA and patterns of internet usage. Four multiple linear regression models were examined.

Model 1: IA Regressed on HIU and PWC

Online gaming significantly predicted IA scores, β = .299, t(608) = 7.904, p < .001. Looking for pornography also significantly predicted IA scores, β = .203, t(608) = 5.392, p < .001. Thus, online gaming and looking for pornography explained a significant proportion of the variance in IA scores, R2 = .142, F(3, 608) = 33.527, p < .001 (Table 5). In addition, depression significantly predicted IA scores, β = .338, t(584) = 5.828, p < .001.

Model 2: SIU Regressed on DB, Self-Esteem Scale (SE), Depression (DEP) Scale and Loneliness (LN) Scale

Ages of 15–17 years significantly predicted SIU, β = .141, t(642) = 3.606, p < .001. The female gender also significantly predicted SIU, β = .144, t(642) = 3.695, p < .001. These demographic variables explained a significant proportion of the variance in SIU, R2 = .040, F(4, 642) = 6.621, p < .001 (Table 5). Adolescents’ levels of self-esteem and depression predicted SIU, β = .128, t(588) = 2.296, p < .05; and β = .084, t(588) = 4.470, p < .001, respectively. In addition, adolescents’ loneliness levels predicted SIU, β = − .133, t(588) = − 2.473, p < .05. Thus, the PWC listed above explained a significant proportion of the variance in SIU, R2 = .034, F(3, 588) = .899, p < .001 (Table 5).

Model 3: “Online Gaming” (EU1) Regressed on DB, SE, DEP and LN

In this model, only the male gender significantly predicted a tendency to play online games (EU1), β = .306, t(647) = 8.145, p < .001 (Table 5). Thus, the male gender explained a significant proportion of the variance in EU1, R2 = .082, F(4, 647) = 16.670, p < .001.

Model 4: “Looking for Pornography” (EU2) Regressed on DB, SE, DEP and LN

Among the DBs, only the male gender significantly predicted EU2, β = .132, t(638) = 3.374, p < .01. This variable explained a significant proportion of the variance in EU2, R2 = .029, F(4, 638) = 4.728, p < .01 (Table 5). Regarding the PWC, only DEP significantly predicted EU2, β = .239, t(584) = 4.025, p < .001. DEP explained a significant proportion of the variance in EU2, R2 = .037, F(5, 584) = 7.429, p < .001 (Table 5). Thus, the male gender and DEP explained a significant proportion of the variance in EU2, R2 = .071, F(7, 578) = 6.265, p < .001 (Table 5).

Discussion

Association between Age, Gender, and PWC

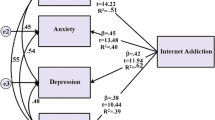

Adolescents aged 15–17 years and female adolescents tended to use the internet for social interactions more frequently than their male counterparts. However, the mean difference in the amount of time females and males spent on online gaming and looking for pornography was more substantial. Male adolescents tended to use the internet more frequently for online gaming and looking for pornography than females. In terms of PWC, adolescents’ levels of depression had a weak, positive correlation with the frequency of SIU. On the other hand, depression and loneliness were positively related to more frequent use of the internet to looking for pornography (Fig. 1).

Correlations between all variables. Positive values indicate a positive correlation with the female gender whereas negative values indicate a correlation with the male gender. HIU habits of internet use, DB demographic background, PWC psychological well-being conditions, IA internet addiction, SIU social interaction usage, EU1 entertainment usage 1—online gaming, EU2 entertainment usage 2—looking for pornography, SE self-esteem, DEP depression, LN loneliness

IA is associated with HIU and PWC

In general, 22% of adolescents had spent 38 h or more per week on the internet, reaching the threshold of an IA (Table 1), based on Young’s (2007) definition. SIU for the purpose for making friends and communicating with others through SNS, forums and chatrooms has become a common practice. Among the three HIU studied here, adolescents in our sample spent more time on SIU than online gaming or looking for pornography (Table 1). Social interaction (r = .108, p < .01) was positively correlated with IA. However, the effect of social interaction on IA was still weak compared with that of online gaming (r = .311, p < .01) and looking for pornography (r = .208, p < .01). This finding was also supported by the regression analysis, showing that 14.2% of the variance explained by online gaming and looking for pornography predicted IA.

In terms of PWC, self-esteem was negatively correlated with IA, whereas depression and loneliness were positively correlated with IA. Comparatively, depression had stronger effect on IA than loneliness or self-esteem. According to the results of the regression analysis, 10.1% of the variance explained by depression predicted IA (Table 6). These findings are consistent with previous studies, in which depression was a major cause of IA in adolescents (Ha et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2011).

Based on the results of this study, frequent online gaming was more likely to be associated with IA than were social interactions or looking for pornography, consistent with the results from a previous study (Chou et al., 2005). Moreover, male adolescents tended to spend more time on online gaming than females, suggesting that increased effort should be spent on preventing male students from becoming addicted to this type of internet activity. According to previous studies, entertainment usage of the internet is more likely to result in psychological problems than social usage (Kim et al., 2009). However, psychological conditions, such as loneliness, depression and self-esteem, were not significantly correlated to online gaming in this study. Thus, more information is needed to understand the reasons underlying the frequent involvement in online gaming. The most direct entry point may be to listen to students’ stories and interpreting their context at the beginning stages of addiction. After establishing positive relationship with students, social workers should further assess students’ needs underlying their addictive behaviors.

In terms of looking for pornography on the internet, little information about its relationship with PWC is available in the current literature. In this study, depression and loneliness were positively correlated with EU2. Although the effect was not strong, this finding may provide insights for social workers who are designing an intervention plan related to pornography. Furthermore, these results may help fill the knowledge gap, service gap (micro practice) and policy gap (macro practice) in preventing and tackling adolescents’ IAs.

Knowledge Implications

The emergence of IA in adolescents has become an issue that parents, teachers and social workers must be prepared to confront. For many adolescents, IA has evolved into a potentially debilitating practice that may be harmful to their healthy development. For example, more than half of adolescents reflected that they have been told more than once that they spend too much time online (56.4%), felt restless and irritable when the internet was disconnected or unavailable (58.9%), stayed online for longer periods of time than intended (50.3%) and felt that surfing the internet had negatively affected their physical health (50.6%). However, a consensus on diagnostic criteria to assess IA has not yet been reached. The prevalence of IA in different countries is currently measured using by different assessment tools. Young’s IAT and Chen’s CIAS are the most common tools used for screening and diagnosing problematic internet use. The former is widely used by Western researchers and in Hong Kong, whereas the latter is mainly used by the rest of Chinese society such as Mainland China and Taiwan. Because these tools use different cutoff values for classifying IA, an explanation of the phenomenon and measurements of improvements may be difficult when comparing the results from other countries. Therefore, a standardized definition and assessment tool to identify IA is an unmet need. Comprehensive schemes for effective prevention and management for adolescents with IA are necessary. However, studies evaluating related topics are very limited. Social workers and clinicians must adopt models from other countries. However, those models have not been validated in the locality. Evidence-based preventive and interventional measures in the field should be developed in future studies.

This study adopted a quantitative approach to examine how PWC influence adolescents’ internet usage and IA. Depression, loneliness and self-esteem were correlated with IA, but the effect was weak to moderate. Additional qualitative data, such as in-depth interviews or case studies, are urgently needed to explore the reasons for adolescents’ IAs and how these factors are linked to psychological conditions to supplement the inadequacy of quantitative methods.

Service Implications

Casework, group work and educational programs related to IA are available in micro social work practice. Based on the findings of this study, social workers should focus their attention on students’ depressive syndrome that lead to IA. Moreover, male adolescents’ addiction to online gaming may represent an entry point and a regular service segment for social workers to prevent and tackle IA. By reviewing service directions dealing with adolescents’ IAs in some Asian regions, such as Hong Kong, most of the services mainly focus on treatment or remedial services (Cheung, 2014, 2018; Yan, Cheung, Chu, & Tsui, 2017). However, international experiences reflect some consensus that prevention is the preferred choice among the approaches used to address excessive internet use (Young & Abreu, 2011). In addition, once IA evolves into a debilitating form, it may have a high relapse rate, exacerbating the condition (Young & Abreu, 2011). Thus, prevention is more important for solving IA.

The findings of this study provide insights for social workers and teachers regarding the design of preventive programs for adolescents. For example, IA tests may be administered to students, parents and teachers to increase awareness of problematic internet use and its negative impacts. Workshops and programs that aim to increase students’ understanding and awareness of the relationship between different HIU and IA are also recommended. In social work, the use of social media has also become a new trend with young people in the cyber world (Chan, 2016; Chan & Holosko, 2016b). Information and communication technology-enhanced social work interventions might provide a good entry point for connecting with adolescents who have a tendency toward IA. Conversely, an empirical review of IA outcome studies (Liu, Liao, & Smith, 2012) suggested that a combination of family therapy or group therapy with CBT may be efficacious to treat IA, especially in the Chinese context.

Policy Implications

This study investigated the psychological well-being needs of youngsters associated with IA. A positive attitude and critical awareness of problematic internet use from not only the public but also teenagers themselves is needed. Policymakers should not only target students but also encourage the positive participation of schools and families to effectively prevent adolescents from developing an IA. Adolescents’ psychological well-being is correlated with their social environment to a large extent. The observation that depression, loneliness and a lack of self-esteem lead to IA may reflect adolescents’ dissatisfaction with the fulfillment of their needs, such as a lack of school support, lack of a sense of achievement, bad relationships with family members, etc. Thus, the development of supportive resources in different social contexts, such as school settings, will promote the primary prevention and promotion of psychosocial well-being. This process cannot be achieved without the government’s support. The government could grant funding to academic institutions to conduct research with the aim of developing a comprehensive scheme for the effective prevention and management of adolescents’ IA. Furthermore, some funding should support the development of a good practice model to help prevent and tackle IA by social service organizations or schools. Academic institutions are currently commissioned to conduct evaluations on the funded services provided by the social service organizations and schools; thus, the practice model should be able to be improved in a timely manner.

Limitations of the Study

As this study was a cross-sectional study, a causal inference cannot be made. Due to limited time and resources, the researchers collected samples using open invitations to secondary schools. The required number of effective samples should be 384 or above, with a 95% confidence level and 5% confidence interval. Even though the required sample size was fulfilled, a non-probability sampling method was still used. In other words, this is not a representative distribution of the targeted population. Upon examining the profile of the samples collected, some distributions, such as the territory-wide and gender distributions, were too widespread for statistical analysis. However, most of the study population consisted of students from junior form (S1–S3, 72.5%) because most of the schools preferred that junior forms participated in the study. In addition, a self-administered questionnaire was a more cost-effective choice than conducting face-to-face surveys. However, it is more difficult to control the quality of the data using self-administered questionnaires than it is for face-to-face surveys, since the researchers are unable to clarify the respondent’s answers or receive an explanation when confusion arises. This study may provide an important reference for future longitudinal studies.

References

Amichai-Hamburger, Y., & Ben-Artzi, E. (2003). Loneliness and internet use. Computer in Human Behavior, 19, 71–80.

Anderson, E. L., Steen, E., & Stavropoulos, V. (2017). Internet use and problematic internet use: A systematic review of longitudinal research trends in adolescence and emergent adulthood. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22, 430–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2016.1227716.

Bos, A. E. R., Huijding, J., Muris, P., Vogel, L. R. R., & Biesheuvel, J. (2010). Global, contingent and implicit self-esteem and psychopathological symptoms in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 311–316.

Breakthrough. (2010). Youth media usage 2010 (In Chinese). Retrieved July 15, 2014, from http://www.breakthrough.org.hk/ir/Research/44_Youth_media_usage/figure.pdf.

Bukstein, O. G., Glancy, L. J., & Kaminer, Y. (1992). Patterns of affective comorbidity in a clinical population of dually diagnosed adolescent substance abusers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 31, 1041–1045.

Butler, R. J., & Gasson, S. L. (2005). Self-esteem/self-concept scales for children and adolescents: A review. Child & Adolescent Mental Health, 10, 190–201.

Ceyhan, A. A., & Ceyhan, E. (2008). Loneliness, depression, and computer self-efficacy as predictors of problematic internet use. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 11, 699–701.

Chan, C. (2016). A scoping review of social media use in social work practice. Journal of Evidence-Informed Social Work, 13, 263–276.

Chan, C., & Holosko, M. J. (2016a). The utilization of social media for youth outreach engagement: A case study. Qualitative Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325016638917.

Chan, C., & Holosko, M. J. (2016b). A review of information and communication technology enhanced social work interventions. Research on Social Work Practice, 26, 88–100.

Chang, M. K., & Law, S. P. M. (2008). Factor structure for Young’s internet addiction test: A confirmatory study. Computers in Human Behavior, 24, 2597–2619.

Chen, S., Weng, L., Su, Y., Wu, H., & Yang, P. (2003). Development of a Chinese internet addiction scale and its psychometric study. Chinese Journal of Psychology, 45, 279–294. (In Chinese).

Chen, S. K. (2012). Internet use and psychological well-being among college students: A latent profile approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 2219–2226.

Cheung, C. K., & Bagley, C. (1998). Validating an American scale in Hong Kong: The Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Journal of Psychology-Worcester Massachusetts, 132, 169–186.

Cheung, J. C. S. (2014). Children and youth services from a family perspective: To be or not to be? Social Work, 59, 358–360.

Cheung, J. C. S. (2016). Confronting the challenges in using social network sites for cyber youth work. Social Work, 61, 171–173.

Cheung, J. C. S. (2018). A social worker with two watches: Synchronizing the left and right ideologies. International Social Work, 61, 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872815620259.

Cheung, L. M., & Wong, W. S. (2011). The effects of insomnia and internet addiction on depression in Hong Kong Chinese adolescents: An exploratory cross-sectional analysis. Journal of Sleep Research, 20, 311–317.

Chou, C., Condron, L., & Belland, J. C. (2005). A review of the research on internet addiction. Educational Psychology Review, 17, 363–388.

Corcoran, K. J., & Fischer, J. (1987). Measures for clinical practice: A source book. New York: Free Press.

Davis, R. A. (2001). A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 17, 187–195.

Ferraro, G., Caci, B., D’Amico, A., & Blasi, M. D. (2007). Internet addiction disorder: An Italian study. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10, 170–175.

Gordon, C. F., Juang, L. P., & Syed, M. (2007). Internet use and well-being among college students: Beyond frequency of use. Journal of College Student Development, 48, 674–688.

Gross, E. F., Juvonen, J., & Gable, S. L. (2002). Internet use and well-being in adolescence. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 75–90.

Ha, J. H., Su, Y. K., Soojeong, C. B., Sujin, B., Hyungjun, K., ... Soo, C. C. (2007). Depression and internet addiction in adolescents. Psychopathology, 40, 424–430.

Hetzel-Riggin, M. D., & Pritchard, J. R. (2011). Predicting problematic internet use in men and women: The contributions of psychological distress, coping style, and body esteem. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14, 519–525.

Huang, H. Y. (2007). Gratification-opportunities, self-esteem, loneliness in determining usage preference of BBS and Blog among mainland teenagers. [Master Thesis] Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Retrieved July 15, 2014, from http://pg.com.cuhk.edu.hk/pgp_nm/projects/2007/Hanyun%20Huang.pdf.

Israelashvili, M., Kim, T., & Bukobza, G. (2012). Adolescents’ over-use of the cyber world: Internet addiction or identity exploration? Journal of Adolescence, 35, 417–424.

Kim, J., Larose, R., & Peng, W. (2009). Loneliness as the cause and the effect of problematic internet use: The relationship between internet use and psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 12, 451–455.

Kim, J. H., Lau, C. H., Cheuk, K. K., Kan, P., Hui, H. L. C., & Griffiths, S. M. (2009). Brief report: Predictors of heavy internet use and associations with health-promoting and health risk behaviors among Hong Kong University students. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 215–220.

Ko, C. H., Yen, J. Y., Chen, C. C., Chen, S. H., & Yen, C. F. (2005). Gender difference and related factors affecting online gaming addiction among Taiwanese adolescents. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 193, 273–277.

Ko, C. H., Yen, J. Y., Chen, C. S., Yeh, Y. C., & Yen, C. F. (2009). Predictive values of psychiatric symptoms for internet addiction in adolescents: A 2-year prospective study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163, 937–943.

Leung, L., & Lee, P. S. N. (2012a). Impact of internet literacy, internet addiction, symptoms, and internet activities on academic performance. Social Science Computer Review, 30, 403–418.

Leung, L., & Lee, P. S. N. (2012b). The influence of information literacy, internet addiction and parenting styles on internet risks. New Media and Society, 14, 117–136.

Leung, S. O., & Wong, P. M. (2005). Validity and reliability of Chinese Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Macau: University of Macau.

Leung, Z. C., Wong, S. S., Lit, S. W., Chan, C., Cheung, F., & Wong, P. L. (2017). Cyber youth work in Hong Kong: Specific and yet the same. International Social Work, 60, 1286–1300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872815603784.

Lin, M. P., Ko, H. C., & Wu, Y. W. (2011). Prevalence and psychosocial risk factors associated with internet addiction in a nationally representative sample of college students in Taiwan. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14, 741–746.

Liu, C., Liao, M., & Smith, D. C. (2012). An empirical review of internet addiction outcome studies in china. Research on Social Work Practice, 22, 282–292.

Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. J. (2007). Taking risks when communicating on the internet: The role of offline social-psychological factors in young people’s vulnerability to online risks. Information, Communication and Society, 10, 619–644.

Manago, A. M., Taylor, T., & Greenfield, P. M. (2012). Me and my 400 friends: The anatomy of college students’ facebook network, their communication patterns, and well-being. Developmental Psychology, 48, 369–380.

Murali, V., & Geonrge, S. (2007). Lost online: An overview of internet addiction. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13, 24–30.

Park, N., & Lee, H. J. (2012). Social implications of smartphone use: Korean college students’ smartphone use and psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 15, 491–497.

Poli, R., & Agrimi, E. (2012). Internet addiction disorder: Prevalence in an Italian student population. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 66, 55–59.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Radloff, L. S., & Locke, B. Z. (1986). The community mental health assessment survey and the CES-D scale. In M. Weissman, J. Myers & C. Ross (Eds.), Community surveys (pp. 66–79). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Russell, D. W. (1996). UCLA loneliness scale: Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66, 20–40.

Schmit, S., Chauchard, E., Chabrol, H., & Sejourne, N. (2011). Evaluation of the characteristics of addiction to online video games among adolescents and young adults. Encephale-Revue de Psychiatrie Clinique Biologique et Therapeutique, 37, 217–223.

Shaver, P. R., & Brennan, K. A. (1991). Measure of depression and loneliness. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measurement of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 195–290). New York: Academic Press.

Shek, D. T. L., Tang, V. M. Y., & Lo, C. Y. (2008). Internet addiction in Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong: Assessment, profiles, and psychosocial correlates. The Scientific World Journal, 8, 776–787.

Shek, D. T. L., & Yu, L. (2011). Internet addiction phenomenon in early adolescents in Hong Kong. The Scientific World Journal, 2012, 1–9.

Tsang, S. K. M. (1997). Parenting and self-esteem of senior primary school students in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Boys & Girls’ Club Association of Hong Kong.

Wang, J. L., Jackson, L. A., Zhang, D. L., & Su, Z. Q. (2012). The relationship among the big five personality factors, self-esteem, narcissism, and sensation-seeking to Chinese University students’ uses of social networking sites (SNSs). Computers in Human Behavior, 28, 2313–2319.

Yan, M. C., Cheung, J. C. S., Chu, W. C. K., & Tsui, M. S. (2017). Examining the neoliberal discourse of accountability: The case of Hong Kong’s social service sector. International Social Work, 60, 976–989. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872815594229.

Yellowlees, P. M., & Marks, S. (2007). Problematic internet use or internet addiction? Computers in Human Behavior, 23, 1447–1453.

Young, K. S. (1998a). Internet addiction: The emergence of a new clinical disorder. Cyberpsychology and Behavior, 1, 237–244.

Young, K. S. (1998b). Caught in the net. New York: Wiley.

Young, K. S. (2007). Treatment outcomes with internet addicts. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 10, 671–679.

Young, K. S. (2015). The evolution of internet addiction disorder. In C. Montag & M. Reuter (Eds.), Internet addiction, studies in neuroscience, psychology, and behavioral economics (pp. 3–17). New York: Springer.

Young, K. S. (2017). The evolution of internet addiction. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 229–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.05.016.

Young, K. S., & Abreu, C. N. (Eds.). (2011). Internet addiction: A handbook and guide to evaluation and treatment. Hoboken: Wiley.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheung, J.CS., Chan, K.HW., Lui, YW. et al. Psychological Well-Being and Adolescents’ Internet Addiction: A School-Based Cross-Sectional Study in Hong Kong. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 35, 477–487 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0543-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0543-7