Abstract

In 2011 6.4 million children in the United States ages four to 17 years had a diagnosis of Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Quantitative studies have indicated that parenting stress for parents of children diagnosed with ADHD is high. This meta-synthesis compiled and analyzed a systematic review of the qualitative studies of parents’ lived experience of having a child with ADHD. Searches in online scholarly databases yielded an initial 1217 hits, which were narrowed down to seventy-three studies that met the criteria. A “meta-ethnography” framework was used for the synthesis. One major finding involved the emotional burden of caring for a child with ADHD. Parents struggled with a variety of intense and painful emotions as they attempted to manage family routines. Disciplining children only worked in a limited way and took constant effort throughout the day. The challenges of parenting spilled into other areas of the parents’ lives, such as their health, psychological, marital, and occupational functioning. Implications for practitioners are discussed, including the need to validate parental stress and the difficulty of applying behavioral management strategies with their children, the need for increased support of partner relationships, and the need to connect parents with support to prevent poorer outcomes for the child.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is characterized by a persistent pattern (6 months or more) of inattention and/or hyperactivity and impulsive behavior that is more frequent and severe than what is typically observed in others at a comparable developmental level (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Children with ADHD show a lack of self-control and ability to sustain direction. They are distractible, do not often finish what they start, and are irritable and impatient, often interrupting and pestering others. In 2011 6.4 million children in the United States ages 4–17 years had a diagnosis of ADHD (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). The rate of diagnosis is 11 %, and has increased throughout even recent years—from 7.8 % in 2003 to 9.5 % in 2007 and to 11.0 % in 2011. This involves an increase of 3 % per year since 1997. Boys are more likely to be diagnosed than girls (13.2 vs. 5.6 %) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015).

Pervasive child problems in the way of daily negative interactions and behavioral management difficulties demand considerable parental resources (Coghill et al., 2008). These demands often result in failure, fatigue, demoralization, isolation, strained marital relationships, and neglect or overindulgence of siblings (Whalen & Henker, 1999). A recent systematic review of 22 published and 22 unpublished studies indicated that parenting stress, while greater for parents with children with ADHD compared to “normal” control, was not different from parents of other clinically referred children (Theule, Wiener, Tannock, & Jenkins, 2013). Stress did not differ substantially between mothers and fathers, but the presence of maternal depression, severe ADHD, and conduct problems in children worsened stress, as did having a male child.

In addition to this meta-analysis about parenting stress, a meta-synthesis was also conducted on parenting decisions about treating their children with ADHD medication (Ahmed, McCaffery, & Aslani, 2013). Eleven studies involving 335 parents of children were located, and four major themes emerged: confronting the diagnosis, external influences, apprehension regarding therapy, and experience with the healthcare system. Confronting the diagnosis involved coming to terms with the diagnosis itself, often after a period of denial and skepticism about the validity of the disorder, especially considering sensationalized media reports and the brief nature of the initial evaluation that led to a diagnosis. Parental disagreement about these matters was common at this point, and family and friends opinions—both for and against—weighed in. The school system had an influence on decision-making with parents feeling some pressure from teachers to put their child on medication due to children’s poor academic and behavioral performance at school. Parents were worried about side effects of medication, the potential for addiction, side effects, the cost of medication, and whether there would be long-term consequences from medication use. For some parents, the noticeably positive impact of medication on children’s behavior outweighed these issues, but other parents’ discontinued their children’s medication because of them. The availability of support and information from the healthcare system, which often parents found sketchy, was another influence on treatment decisions. Many parents wanted to exhaust other treatment options first—usually behavioral management programs and natural remedies—before they decided to use medication.

Ahmed et al.’s (2013) meta-synthesis was limited by including only published studies and a focus on treatment decisions. The purpose of this meta-synthesis is to do a comprehensive review of both the published and unpublished studies and to consider the totality of parents’ lived experience, not just their choice of whether to medicate their children. This manuscript reports on the aspect of the findings that have to do with the impact of the experience on the parents themselves.

Methodology

Inclusion Criteria and Search

The inclusion criteria for studies was that they were qualitative studies on the experience of parents raising a child diagnosed with ADHD. The child had to be under 18. Studies were excluded if they involved medical or social service providers and did not report results separately for parents. Only studies in English were included, unless a translation was available. The search was pre-planned, and there were no initial date parameters put on the search which ended April 2015. A graduate level research assistant was trained on the search process by the principal investigator and a reference librarian, who constructed the search strings. The following databases relevant to the topic were searched: Academic Search Complete, AMED, Child Development and Adolescent Studies, CINAHL, Family Studies Abstracts, Social Work Abstracts, Social Sciences Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, Health Source, Master FILE Premier, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, SocINDEX, Psychinfo, PubMed, and Dissertations and Theses Global. Search terms were as follows: (“personal reflection” OR “personal experience” OR “lived experience” OR phenomenology* OR qualitative) AND (mother* OR father* OR caregiver* OR parent* OR family*) AND (“attention deficit hyperactivity disorder” OR “attention deficit disorder” OR “ADHD”). The total number of “hits” on the search terms for all the databases was 1217.

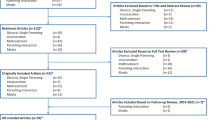

Meade and Richardson (1997) developed a three-step process for study selection, which allows for narrowing the results of the search based first on title alone, then the abstract, and lastly the entire text if needed. After his review, the graduate level research assistant identified 348 studies that appeared to fit the criteria. One hundred and eighty-nine were found to be duplicates. After reviewing the abstracts, the principal investigator believed 159 to fit the criteria, and the full text of the studies was obtained. Three graduate level research assistants, along with the principal investigator, screened the full text of the studies, and narrowed them to 80 (see Fig. 1). Please contact the first author for more details on the search.

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data from the primary studies were extracted from the results section of the studies. The data was analyzed for themes within the broad framework of Aguirre and Bolton’s (2014) conceptualization that each study’s themes become woven as “part of a web of knowledge about the topic where a synergy among the studies creates a new, deeper and broader understanding” (p. 283). More specifically, the methodological framework provided by Noblit and Hare (1988), which they call “meta-ethnography” was used for the synthesis, following an inductive method. Noblit and Hare (1988) suggest making lists and tables of the important phrases, metaphors, and other key findings from each study, and then making comparisons of the main ideas to determine overlap and commonality. Noblit and Hare (1988) discuss the importance of communicating the synthesis through tables listing themes and providing supporting quotes from the original studies.

Results

Eighty studies, involving 86 reports, fit the inclusion criteria for parental experiences with children diagnosed with ADHD. The majority of parents who participated were married mothers, although fathers were at times the focus of studies (Singh, 2003) and single parents only (Hancock, 2003). The majority of studies were conducted in the U.S., with other developed countries being represented (U.K., Australia, Ireland, Norway), with both published and unpublished studies represented. Most of the studies involved individual interviews. See Table 1 for more details on studies. This manuscript describes the overall theme of the impact on parents themselves of taking care of a child with ADHD.

Parents struggled with the emotional burden of caring for a child with ADHD and managing the hyperactive, impulsive, and inattentive behaviors, which were detailed in all studies, including lack of focus, forgetfulness, inability to listen and complete tasks, poor grades, tantrums, aggression, risk-taking, poor social relationships and running off. Parents talked about the constant mess, and the chaos and conflict that besieged their home life (Kendall, 1998). As a result of this struggle, parents spoke of a myriad of intense, negative emotions (see Table 2.).

Caregiving was experienced as a “24-h a day” undertaking (Hallberg, Klingberg, Reichenberg, & Moller, 2008). As one mother of a seven year old said, “‘To be a teacher, mother, minder, carer, everything and 24 h round the clock it’s just an exhausting experience’” (McIntyre & Hennessy, 2012, p. 72). In D. Taylor (1999), one parent echoed, “‘a constant struggle always, always with her, every single day’” (p. 22), and another said, “‘You feel like you are constantly on them all the time, nag–nag-nag. That can be sometimes a terrible feeling’” (D. Taylor, 1999, p. 23). Typical family routines proved to be a daily challenge (Canfield, 2000; Howard, 1993; Moen, Hall-Lord, & Hedelin, 2014; Segal, 1998; Segal & Frank, 1998; M. Taylor, Houghton, & Durkin, 2008; Wong & Goh, 2014). As one mother reported, “…It is very hard for my son to follow the daily routine, such as abiding by the daily rules and finishing his work at hand” (Lin, Huang, & Hung, 2009, p. 1679). Certain times of the day presented particular difficulty. One parent stated,

Nighttime is, is bad because my son doesn’t have a high sleep requirement. He, if he doesn’t have his nighttime meds, he doesn’t go to bed until mid-night, one, two, three, four o’clock in the morning. He doesn’t sleep without nighttime meds. Um, bedtime is the hardest because it’s hard for them to calm down (Firmim & Phillips, 2009, p. 1165).

Another parent in the same study described difficulties with the morning routine, “‘And no matter how early we start, how early they get up, they still end up running out the door. So that’s always a battle. So that’s how we start our days, just about every day, it drives me insane’” (Firmim & Phillips, 2009, p 1163). A single mother, speaking about mornings, said, “’He’s constantly making the whole family late…and we’re always mad at him’” (Hancock, 2003, p. 90).

Other people found the hours after school very hard as one participant described: “’Homework, homework here is ‘Lord help us.’ …You spend all day at school and then trying to do homework, and then they get distracted, they get frustrated, the anger mounts’” (Firmim & Phillips, 2009, p. 1165). Another parent described trying to do routine errands after school:

Nothing is easy and I’m not only talking about school work, I’m talking about if I need to run an errand after school. If I haven’t prepped him for it in advance there can be a meltdown and lot of times, you can’t do it. Or, if you do it, you pay the consequences of whiny, pain-in-the-ass crying. So I have to think very carefully about what needs to be done when they come home from school, so I can give them time to adjust to what we have to do. Sometimes that doesn’t even work… I always have to be thinking. I always have to be planning… I have to do even more of that than most mothers. So it’s difficult (Roosa, 2003, p. 197).

As Moen, Hall-Lord, and Hedelin (2011) summarized participants’ responses about how normal routines became disrupted:

The child with ADHD was described as getting stuck in a rut without being receptive to attempts to correct his or her behavior. Consequently, a normal everyday situation might be turned upside down; hence, joy and expectations the family anticipated were transformed into a sense of failure. As one father explained, “We were going to find a Christmas tree before Christmas. He sat bickering with his brother in the back seat. We were looking forward to having a nice trip, as you often do before Christmas. He had a massive temper tantrum, a bit extreme, I thought—bad language, behaviour etc.; he just wouldn’t calm down, so the trip was completely ruined” (pp. 447–449).

A subtheme that emerged under the impact on caregivers involved their parenting. Normal behavioral discipline techniques (reinforcing and rewarding positive behaviors and ignoring or punishing undesirable behaviors) only worked in a limited way with these children (Bussing, Koro-Ljungberg, Williamson, Gary, & Garvan, 2006; DuCharme, 1996; Segal, 1994). As one participant said, “‘There is no easy way to discipline an ADHD child’” (Bull & Whelan, 2006, p. 671), and others in D. Taylor (1999) stated, “‘It’s very frustrating to figure out how to discipline this kid’” (p. 21) and “‘We’ve tried a lot of different behavior programs’” (p. 21). The difficulty with behavioral strategies was echoed in Kendall (1998):

I get exhausted trying to figure it all out. I know that rewards are supposed to work, but after awhile you run out of rewards and you run out of interest in providing them, especially when it seems it never goes anywhere except just doing the day-to-day stuff one has to do to survive. I mean, do I give him rewards for getting up in the morning, and getting dressed on time and getting to school on time and doing his homework and this and that? (p. 847).

The challenges of parenting spilled into other areas of the parents’ lives. This stress involved threats to health (Bull & Whelan, 2006; Hallberg et al., 2008), and psychological, marital, and social well-being (Peters & Jackson, 2009). In multiple studies, parents changed or quit their jobs to better manage their child’s behaviors (e.g., Hallberg, et al., 2008; Ho, Chien, & Wang, 2011; Moen et al., 2011).

Parents said their children’s relentless misbehavior negatively affected their marital relationships (Bullard, 1996; Cawley, 2004; Dennis, Davis, Johnson, Brooks, & Humbl, 2008; Hallberg et al., 2008; Hammerman, 2000; Ho et al., 2011; Howard, 1993; Kilcarr, 1996; Lin et al., 2009; Moen et al., 2011; Okafor, 2006; Roosa, 2003; Squire, 1993): “‘My marriage nearly split up along the way,’” (Bull & Whelan, 2006, p. 672). This happened for various reasons.

McIntyre and Hennessy (2012) described that children’s need for constant attention meant that children disrupted any time parents had together. As one of the study’s participants described, “‘From a very young age if myself and [husband] were sitting down to relax he would climb in between us, if you’re having a hug he’d climb in between us, if [husband] put his arm around me he’d climb in between us … every time we were having a conversation we were interrupted’” (p. 72). Second, mothers often became the primary disciplinarians, again for various reasons. One primary reason was that fathers did not know how to manage the child’s unruly behaviors (Chavarela, 2009; Funes de Hernandez, 2005). A mother described, “‘My husband is very impatient when he deals with my son. He often beats him while taking care of him. Thus, I can’t let my husband help me to take care of my son’” (Lin et al., 2009, p. 1690). Another participant in Lin et al. (2009) lamented that this lead to lack of support: “‘My son doesn’t like to stay with his father because he always ignores him or shouts at him…You see, no one can give me a hand, not even my husband…’” (Lin et al., 2009, p. 1698). Because of the effort and finessing involved to manage these children and some times cultural reasons (Latino) Oquendo, 2013; Chavarela, 2009) mothers preferred to handle discipline alone, wanting husbands to only offer support and back-up only as needed (Bull & Whelan, 2006). Another reason men weren’t as involved with their children was because of their own undiagnosed ADHD (Roosa, 2003; Singh, 2003). They were therefore unable to provide the patience, organization, and structure that such a child demands.

Discussion and Applications to Practice

When results of the qualitative studies on the lived experience of parents with children diagnosed with ADHD were synthesized, it became apparent parents were under considerable stress trying to manage their children’s behavior. The extreme frustration, tension, and exhaustion were clear. Parental descriptions of their experiences deepened the findings from the quantitative literature that speak to the amount of stress that parents with ADHD are under (Theule et al., 2013). It appears that parents with children diagnosed with ADHD work very hard to manage their children, and, according to this meta-synthesize may not feel rewarded for their efforts. Instead, they experience a toll on their lives in terms of their partner relationships and occupational functioning. They feel ineffective in their parenting roles, both in their own self-concept as parents and in the eyes of society. This theme of extreme parental stress was not found in Ahmed et al.’s (2013) meta-synthesis, likely because theirs centered on treatment decisions. Additionally, the current meta-synthesis involved almost twice as many studies and included the unpublished (dissertations) literature, as well as published studies.

An implication for social workers is to educate parents on typical reactions they may have and to validate and normalize their concerns. Burden may be reduced through validation of parenting efforts and providing psychoeducation, normalizing typical experiences, such as the feelings of ineffectiveness as a parent. Additionally, providing support and helping parents connect with support—family and friends and/or support groups or other formal services—is key for a parent’s own mental health, health, and partner relationships.

Parenting states are also important because they can influence child outcomes. Maternal depression predicts a worse treatment outcome (Owens et al., 2003). Conversely, low parental expressed emotion (criticism and negativity toward the child) may moderate the genetic effect associated with ADHD (Sonuga-Burke et al., (2008). Maternal warmth may protect against ADHD becoming severe or from conduct disorder developing. However, maternal warmth can be difficult to achieve, given the negative affective states that parents expressed in the qualitative research. Self-care strategies and respite should be a part of work with parents to prevent or ameliorate any possible negative consequences to themselves, as well as their children. Depression screening for parents, and particularly mothers, could be a routine part of services when children are identified as having ADHD in outpatient mental health agencies, school settings, and physician and psychiatrists’ office. Appropriate referrals for further evaluation and treatment may be required for depression or other mental health problems that may have been influenced by raising a child with ADHD. Tending to maternal mental health may provide important benefits to both parents and their children.

Given the finding that the marital relationship was often under strain, social workers should center on working with parents together to help unify maternal and paternal parenting efforts and to help the couple feel supported. Partner counseling may be required in some cases given the fact that marriages are at risk when parenting children with ADHD.

There was very little uniformity about the way parents coped, and coping did not emerge as a theme. Parent worn down by caregiving may be unable to spontaneously identify strengths or ways they have to manage their situation. Practitioners can approach such parents from a strengths-based angle, pointing out personal and environmental resources they are activating to cope and bolstering these. They can also ask strengths-based questions around coping (Bertolino & O’Hanlon, 2002): “This sounds very difficult. How are you managing? What do you tell yourself? How are others there for you? What personal qualities do you have that see you through? How do you find meaning in this?”

The treatment outcome literature for ADHD centers on behavioral parent training, (e.g., Pelham & Fabiano, 2008). The qualitative literature goes beyond the findings of these studies to glean the difficulties parents have with behavioral management and its limits with children with ADHD. Parents talked about how structured they had to be in their approach to parenting, which seemed to cause some parents feel that it sapped the joy out of family life. Social workers need to understand parents when they complain that some behavioral techniques “don’t work.” Rather than being seen as a sign of resistance and blaming the parents for their children’s behavior, the practitioner should recognize that although behavioral strategies are important for containing the child’s behavior and structuring the home environment, such techniques might have limited impact on these children, leaving parents feeling demoralized in their parenting efforts. While parents will need support to be effective at using behavioral management techniques, intervention should also focus on self-care strategies so that parents can de-escalate from the difficulty myriad emotions they may feel. Any research involving parent training should assess the domain of parent well-being in outcomes studied.

Conclusion

This study synthesized the literature involving qualitative study of parent experiences with a child diagnosed with ADHD. The challenges parents face are poignantly made clear from this review. Rather than blame for being ineffective at their role, such parents need validation, support and education.

References

Aguirre, R. T., & Bolton, K. W. (2014). Qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis in social work research: Uncharted territory. Journal of Social Work, 14, 279–294.

Ahmed, R., Mccaffery, K., & Aslani, P. (2013). Factors influencing parental decision making about stimulant treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 23, 163–178.

American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: Author.

Bertolino, B., & O'Hanlon, W. H. (2002). Collaborative, competency-based counseling and therapy. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2015). Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Data and statistics. http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html.

Coghill, D., Soutullo, C., d’Aubuisson, C., Preuss, U., Lindback, T., Silverberg, M., & Buitelaar, J. (2008). Impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on the patient and family: Results from a European survey. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 2, 31.

Firmim, M., & Phillips, A. (2009). A qualitative study of families and children possessing diagnoses of ADHD. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 1155–1174. doi:10.1177/0192513X09333709.

Kendall, J. (1998). Outlasting disruption: The process of reinvestment in families with ADHD children. Qualitative Health Research, 8, 839–857.

Meade, M. O., & Richardson, W. S. (1997). Selecting and appraising studies for a systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine, 127, 531–537.

Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Owens, E. B., Hinshaw, S. P., Kraemer, H. C., Arnold, L. E., Abikoff, H. B., Cantwell, D. P., … Hoza, B. (2003). Which treatment for whom for ADHD? Moderators of treatment response in the MTA. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 540–552

Pelham, W. E., Jr., & Fabiano, G. A. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 184–214.

Sonuga-Burke, E. J., Lasky-Su, J., Neale, B. M., Oades, R., Chen, W., Franke, B., et al. (2008). Does parental expressed emotion moderate genetic effects in ADHD? An exploration using a genome wide association scan. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics, 147B, 1359–1368

Squire, M. D. (1993). The impact of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children on family members and family functioning (Order No. 9400829). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/ 9400829?accountid = 14780.

Taylor, D. (1999). Impact of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on parents and children: What are the lived experiences of a parent with a child with ADHD? (Order No. 1394492). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/304851012?accountid=14780.

Theule, J., Wiener, J., Tannock, R., & Jenkins, J. M. (2013). Parenting stress in families of children with ADHD: A meta-analysis. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 21, 3–17.

Whalen, C., & Henker, B. (1999). The child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in family contexts. In H. Quay & A. Hogan (Eds.), Handbook of disruptive behavior disorders (pp. 139–155). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

References in Systematic Review

Ahmed, R., Aslani, P., Boarst, R., & Yong, C. W. (2014). Do parents of children with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) receive adequate information about the disease and its treatments? A qualitative study. Patient Preference and Adherence Dove Press Journal, 8, 661–669.

Alazzam, M., & Daack-Hirsch, S. (2011). Arab immigrant Muslim mothers’ perceptions of children’s attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 185, 23–34.

Arcia, E., & Fernandez, M. C. (1998). Cuban mothers’ schemas of adhd: Development, characteristics, and help seeking behavior. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 7, 333–352.

Bennett, J. A. (2007). (Dis)ordering motherhood: Experiences of mothering a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Order No. U185374). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (301638456). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/301638456?accountid=14780

Brinkman, W., Sherman, S., Zmitrovich, A., Visscher, M., Crosby, L., Phelan, K., & Donovan, E. (2009). Parental angst making and revisiting decisions about treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics, 124, 580–589.

Brunton, C. G., McVittie, C., Ellison, M., & Willock, J. (2014). Negotiating parental accountability in the face of uncertainty for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Qualitative Health Research, 24, 242–253.

Bull, C., & Wheelan, T. (2006). Parental schemata in the management of children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Qualitative Health Research, 16, 664–678. doi:10.1177/1049732305285512.

Bullard, J. A. (1996). Parent perceptions of the effect of ADHD child behavior on the family: The impact and coping strategies (Order No. 9717369). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304274502). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304274502?accountid=14780

Bussing, R., Koro-Ljungberg, M. E., Williamson, P., Gary, F. A., & Garvin, C. W. (2006). What “Dr. Mom” ordered: A community-based exploratory study of parental self-care responses to children’s ADHD symptoms. Social Science and Medicine, 63, 871.

Canfield, S. K. (2000). The lonely journey: Parental decision-making regarding stimulant therapy for ADHD (Order No. 9989350). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304661030). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304661030?accountid=14780

Cawley, P. P. (2004). The parent’s experience of raising a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Order No. 3142068). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305072457). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/305072457?accountid=14780

Charach, A., Skyba, A., Cook, L., & Antle, B. J. (2006). Using stimulant medication for children with ADHD: What do parents say? A brief report. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 15(2), 75–83.

Charach, A., Yeung, E., Volpe, T., Goodale, T., & dosReis, S. (2014). Exploring stimulant treatment in ADHD: Narratives of young adolescents and their parents. BMC Psychiatry, 14, 110.

Chavarela, S. (2009). Cultural differences in the experience of the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of ADHD in a son: Interviews with three Mexican and three Caucasian American mothers (Order No. 3377439). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305174662). Retrieved from Ho, C., http://search.proquest.com/docview/305174662?accountid=14780

Clarke, J., & Lang, L. (2012). Mothers whose children have ADD/ADHD discuss their children’s medication use: An investigation of blogs. Social Work in Healthcare, 51, 402–416. doi:10.1080/00981389.2012.660567.

Davis, C. C., Claudius, M., Palinkas, L. A., Wong, J. B., & Leslie, L. K. (2012). Putting families in the center: Family perspectives on decision making and ADHD and implications for ADHD care. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16, 675–684.

Coletti, D., Pappadopulos, E., Katsiotas, N., Berest, A., Jensen, P., & Kafantaris, V. (2012). Parent perspectives on the decision to initiate medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 22, 226–237.

Cormier, E. (2012). How parents make decisions to use medication to treat their child’s ADHD: A grounded theory study. Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association, 18, 345–356.

Cronin, A. F. (1995). The influence of attention deficit disorder on mother’s perception of family stress: Or, “lady, why can’t you control your child?” (Order No. 9607357). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304202251). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304202251?accountid=14780

Cronin, A. (2004). Mothering a child with hidden impairments. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy: Official Publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association, 58, 83–92.

Dennis, T., Davis, M., Johnson, U., Brooks, H., & Humbi, A. (2008). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Parents’ and professionals’ perceptions. Community Practitioner: The Journal of the Community Practitioners’ & Health Visitors’ Association, 81, 24.

DosReis, S., Barksdale, C. L., Sherman, A., Maloney, K., & Charach, A. (2010). Stigmatizing experiences of parents of children with a new diagnosis of ADHD. Psychiatric Services, 61(8), 811–816.

DosReis, S., Mychailyszyn, M., Myers, M., & Riley, A. (2007). Coming to terms with ADHD: How urban African-American families come to seek care for their children. Psychiatric Services, 58(5), 636–641.

DosReis, S., Mychailyszyn, M. P., Evans-Lacko, S. E., Beltran, A., Riley, A. W., & Myers, M. A. (2009). The meaning of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication and parents' initiation and continuity of treatment for their child. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology, 19, 377–383.

DuCharme, S. (1996). Parents’ perceptions of raising a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Order No. 9706149). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304314626). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304314626?accountid=14780

Egbert, M. A. (1996). Description of the mothers’ perceptions of parenting children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Order No. 1381177). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304312266). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304312266?accountid=14780

Funes de Hernandez, A. M. N. (2005). The everyday world of mothers of children with ADHD: Diverse voices of contemporary mothers (Order No. 1429256). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305367314). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/305367314?accountid=14780

Gerdes, A. C., Lawton, K. E., Haack, L. M., & Schneider, B. W. (2014). Latino parental help seeking for childhood ADHD. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 41, 503–513.

Goodwillie, G. (2014). Protective vigilance: A parental strategy in caring for a child diagnosed with ADHD. Journal of Family Therapy, 36, 255–267.

Hallberg, U., Klingberg, G., Reichenberg, K., & Moller, A. (2008). Living at the edge of one’s capability: Experiences of parents of teenage daughters. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 3, 52–58.

Hammerman, A. R. (2000). The effects of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder children on mothers and fathers: A qualitative study (Order No. 9961167). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304618017). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304618017?accountid=14780

Hancock, D. F. (2003). The lived experience of single mothers with sons with ADHD (Order No. MQ83789). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305251486). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/305251486?accountid=14780

Hansen, D. L., & Hansen, E. H. (2006). Caught in a Balancing Act: Parents dilemma’s regarding their ADHD child’s treatment with stimulant medication. Qualitative Health Research, 16, 1267–1285.

Harborne, A., Wolpert, M., & Clare, L. (2004). Making sense of ADHD: A battle for understanding? Parents’ views of their children being diagnosed with ADHD. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 9, 327–339.

Hatton, D., Kendall, J. K., & Perry, C. E. (2000). Latino parent’s accounts of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 3, 300–306. doi:10.1177/1043659605278938.

Himmel, D. R. (2013). Parents perceptions of raising male children with ADHD (Order No. 3603732). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1471911674). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1471911674?accountid=14780

Ho, C., Chien, W., & Wang, L. (2011). Parent’s perception of care-giving to a child with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: An exploratory study. Contemporary Nurse., 40, 41–56.

Howard, B. G. (1993). Parental perception of the impact on the marital and family functioning of the attention deficit disorder child: A qualitative study (Order No. 9417390). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304089569). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304089569?accountid=14780

Jackson, D., & Peters, K. (2008). Use of drug therapy in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): Maternal views and experiences. Journal of clinical nursing, 17, 2725–2732.

Kay, R. (2007). Parental decision making in the administration of stimulant medication for their latency age children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Order No. 3301292). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304712597). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304712597?accountid=14780

Kilcarr, P. J. (1996). A self-selected qualitative study examining the relationship between a father and his son who has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Order No. 9707629). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304314500). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304314500?accountid=14780

Klasen, H. (2000). A name, what’s in a name? The medicalization of hyperactivity, revisited. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 7, 334–344.

Klasen, H., & Goodman, R. (2000). Parents and GPs at cross-purposes over hyperactivity: A qualitative study of possible barriers to treatment. British Journal of General Practice, 50, 199–202.

Lai, K., & Ma, J. (2014). Family engagement in children with mental health needs in a Chinese context: A dream or reality? Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 23, 173–189. doi:10.1080/15313204.2013.838815.

Larson, J., Yoon, Y., Stewart, M., & Dosreis, S. (2011). Influence of caregivers’ experiences on service use among children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric Services, 62, 734–739.

Leslie, L., Plemmons, D., Monn, A., & Palinkas, L. (2007). Investigating ADHD treatment trajectories: Listening to families’ stories about medication use. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP, 28, 179–188. doi:10.1097/DBP.0b013e3180324d9a.

Lewis-Morton, R., Dallos, R., McClelland, L., & Clempson, R. (2014). “There is something not quite right with Brad…”: The ways in which families construct ADHD before receiving a diagnosis. Contemporary Family Therapy, 36, 260–280.

Lin, M. J., Huang, X. Y., & Hung, B. J. (2009). The experiences of primary caregivers raising school-aged children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18, 1693–1702.

Litt, J. (2004). Women’s carework in low-income households: The special case of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Gender and Society, 18, 625–644.

Martinez, L. (2015). Puerto rican mothers of children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder factors that impact the treatment seeking process (Order No. 3687504). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1669495242). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/1669495242?accountid=14780

McIntyre, R., & Hennessy, E. (2012). ‘He’s just enthusiastic. Is that such a bad thing?’ experiences of parents of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Emotional & Behavioral Difficulties, 17, 65–82.

Mills, I. (2011). Understanding parent decision making for treatment of ADHD. School Social Work Journal, 36, 41–60.

Moen, O., Hall-Lord, M., & Hedelin, B. (2011). Contending and adapting everyday: Norwegian parents’ lived experience of having a child with ADHD. Journal of Family Nursing, 17, 441–462. doi:10.1177/1074840711423924.

Moen, O., Hall-Lord, M., & Hedelin, B. (2014). Living in a family with a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A phenomenographic study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23, 3166–3176.

Morse, E. (2002). Caretakers of children with ADHD: Issues and experiences (Order No. 3061992). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305457445). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/305457445?accountid=14780

Mychailyszyn, M., DosReis, S., Myers, M., Mcdaniel, S. H., & Campell, T. L. (2008). African American caretakers’ views of ADHD and use of outpatient mental health care services for children. Families, Systems, & Health, 26, 447–458.

Neophytou, K., & Webber, R. (2005). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The family and social context. Australian Social Work, 58, 313–325.

Okafor, M. N. (2006). Narrating realities of latino mothers of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD] using ecological and cultural approach (Order No. 3244585). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (305321453). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/305321453?accountid=14780

Oquendo, S. A. (2013). A qualitative study of parenting styles of mothers within latino families raising sons with ADHD (Order No. 3612241). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (1506155007). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1506155007?accountid=14780

Parker, R. B. (1994). The meaning of the experience of parenting a child with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Order No. 1358453). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (230771897). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/230771897?accountid=14780

Perry, C. E., Hatton, D., & Kendall, J. (2005). Latino parents’ accounts of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 16, 312–321.

Peters, K., & Jackson, D. (2009). Mothers’ experiences of parenting a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65, 62–71.

Rice, D. N. (1995). Psychosocial variables operating in families having a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Order No. 9538493). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (304213142). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304213142?accountid=14780

Roosa, N. E. (2003). Parenting a child with ADHD: Making meaning when the experts disagree (Order No. 3088244). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (305228284). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/305228284?accountid=14780

Seawell, M. (2010). Family narratives of ADHD: Labels promoting change (Order No. 3429115). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (760081777). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/760081777?accountid=14780

Segal, E. (1994). Mothering a child with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Learned mothering (Order No. 9612115). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304166370). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304166370?accountid=14780

Segal, E. S. (2001). Learned mothering: Raising a child with ADHD. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 18, 263–271.

Segal, R. (1998). The construction of family occupations: A study of families with children who have attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy/Revue Canadienne D’Ergothérapie, 65, 286–292.

Segal, R., & Frank, G. (1998). The Extraordinary construction of ordinary experience: Scheduling daily life in families with children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 5, 141–147.

Sikirica, V., Flood, E., Dietrich, C., Quintero, N., Harpin, J., Hodgkins, V., & Erder, K. (2015). Unmet needs associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in eight European countries as reported by caregivers and adolescents: Results from qualitative research. The Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, 8, 269–281.

Singh, I. (2000). A crutch, a tool: How mothers and fathers of boys with ADHD experience and understand the work of ritalin (Order No. 9961219). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (304624673). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304624673?accountid=14780

Singh, I. (2003). Boys will be boys: Fathers’ perspectives on ADHD symptoms, diagnosis, and drug treatment. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 11, 308–316.

Singh, I. (2004). Doing their jobs: Mothering with Ritalin in a culture of mother-blame. Social Science and Medicine, 59, 1193–1205.

Smith, A. K. (2011). Factors and symptoms contributing to parent stress in raising an ADHD child (Order No. 3518283). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (1033568055). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/1033568055?accountid=14780

Sullivan, M. D. (2007). Coping strategies of single mothers of children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Order No. MR34994). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304851012). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/304851012?accountid=14780

Taylor, M., O’Donoghue, T., & Houghton, S. (2006). To medicate or not to medicate? the decision-making process of western Australian parents following their child’s diagnosis with an attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 53, 111–128.

Taylor, M., Houghton, S., & Durkin, K. (2008). Getting children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder to school on time: Mothers’ perspectives. Journal of Family Issues, 29, 918–943.

Villegas, T. V. (2007). Experiences and challenges of parents who have children diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (Order No. 3274071). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304722540). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/304722540?accountid=14780

Wallace, N. (2005). The perceptions of mothers of sons with ADHD. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 26, 193–199.

Wilcox, C. E., Washburn, R., & Patel, V. (2007). Seeking help for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in developing countries: A study of parental explanatory models in Goa, India. Social Science and Medicine, 64, 1600–1610.

Wilder, J., Koro-Ljungberg, M., & Bussing, R. (2009). ADHD, motherhood, and intersectionality: An exploratory study. Race, Gender & Class, 16, 59–81.

Williams, M. A. (2009). Exploration of effect of diagnosis of high school girls with attention deficit disorder on their mothers and the mother-daughter relationship (Order No. 3440918). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (849715080). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/849715080?accountid=14780

Williams, N. J., Harries, M., & Williams, A. M. (2014). Gaining control: A new perspective on the parenting of children with AD/HD. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11, 277–297. doi:10.1080/14780887.2014.902524.

Williams. O. (2008). Parental explanatory models of children’s attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Order No. 3398567). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (250292152). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.proxy.library.vcu.edu/docview/250292152?accountid=14780

Wong, H., & Goh, E. (2014). Dynamics of ADHD in familial contexts: Perspectives from children and parents and implications for practitioners. Social Work in Health Care, 53, 601–616.

Yuen, A. (2008). Cross-cultural effects in children diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder on parental and caregiver stress (Order No. 3325344). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. (304382486). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/304382486?accountid=14780

Funding

This study was conducted with no grant funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Corcoran, J., Schildt, B., Hochbrueckner, R. et al. Parents of Children with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Meta-Synthesis, Part I. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 34, 281–335 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-016-0465-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-016-0465-1