Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine if adolescents’ reports of warm and harsh parenting practices by their mothers and fathers varied as a function of demographic, youth and their mothers or mother figures’ individual and family characteristics. Data are from 707 community-dwelling adolescents (mean age = 14, SD = 1.4) and their mothers or mother figures in Santiago, Chile. Having a warmer relationship with both parents was inversely associated with the adolescents’ age and positively associated with adolescents’ family involvement and parental monitoring. Both mothers’ and fathers’ harsh parenting were positively associated with adolescent externalizing behaviors and being male and inversely associated with youth autonomy and family involvement. These findings suggest that net of adolescent developmental emancipation and adolescent behavioral problems, positive relationships with parents, especially fathers, may be nurtured through parental monitoring and creation of an interactive family environment, and can help to foster positive developmental outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A good portion of the research examining parent–child relationships has relied on samples in the United States (U.S.) and European countries. Although some research suggests similarities in discipline techniques and children’s behavior outcomes across countries (Gershoff et al. 2010), further research is needed to examine whether broader aspects of parent–child relationships also differ across international samples. Multiple factors including culture and country demographics can affect family systems including family structure and the nature of parent–child relationships in childhood and adolescence. To enhance our understanding of parent–child relationships in adolescence in an international context, we conducted a study to examine if adolescents’ reports of the quality of their relationship with their parents would vary as a function of demographics, and of the adolescents and mothers or mother figures’ characteristics, using a community sample of adolescents and their families in Santiago, Chile.

To put this study in context, in Chile 67 % of children aged 10–14 and 60 % of adolescents aged 15–19 live with both parents while 22 % of children live in a family headed by a single parent (Herrera 2008). Children in Chile are likely to live with their extended family. Almost two-thirds of Chilean households in 2006 had one or more extended family member living together (i.e., grandparents, cousins, uncles, aunts) (Pallisgaard 2007).

The study draws from the theory of Parental Acceptance and Rejection. This theory, commonly abbreviated as PART (Rohner and Britner 2002; Rohner et al. 2005), suggests that parental behavior will have an important effect on child behavior problems such as child aggression or anxiety and depression. Experiences of parental rejection manifested as harsh parenting behaviors are suggested to lead to undesirable increases in child problem behaviors. For example, harsh parenting practices, generally defined by the amount of parental expressed anger, low levels of praise of a child, high levels of parental disapproval, inconsistent parental behavior, and negative emotions have been linked with child behavior problems across cultures, including externalizing and internalizing problems and noncompliance (Brannigan et al. 2002; Gershoff et al. 2010; Scaramella and Leve 2004). In contrast, experiences of parental acceptance, manifested in parental warmth are suggested to be associated with amelioration of these problematic behaviors (Rohner and Veneziano 2001; Skopp et al. 2007; Veneziano 2003).

While numerous other studies of parenting indicate that the parent–child relationship has clear implications for cognitive and academic outcomes and socio-emotional adjustment (Bradley et al. 2001), examination of factors that may be associated with the parent–child relationship itself has been less common, especially among adolescents. According to Denissen et al. (2009), individual characteristics of the parents and adolescents are associated with the quality of the parent–child relationship. In a study by Dietz et al. (2008), children with depression, for instance, reported having more negative relationships with their parents than a control group. Parents of anxious or withdrawn children were also more likely to have negative beliefs towards their children (Laskey and Cartwright-Hatton 2009). In the same study, parents who believed their children had high levels of internalizing behaviors were more likely to report using high amounts of harsh or punitive discipline techniques (Laskey and Cartwright-Hatton 2009).

According to the coercion model, the relationship between childhood behavioral problems and parenting practices may be at least partly bidirectional (Patterson et al. 1992; Reid et al. 2002) suggesting that youth behaviors not only result from, but also to some degree elicit, particular parenting behaviors. For example, Neppl et al. (2009) found that adolescents’ externalizing behaviors predict harsh parenting with Burke et al. (2008) finding stronger influences from child behaviors to parenting practices than vice versa. Thus, although PART has received extensive cross-cultural support (Rohner et al. 2005), much less attention has been devoted to identifying predictors of the parent–child relationship.

Aside from youth characteristics, research further indicates that family and caregiver characteristics are also important to parenting practices. Several seminal studies point to the relationship between economic disadvantage and parenting practices (Conger et al. 1992; McLoyd 1998; Bradley and Corwyn 2002) with further research linking parent depression to lower levels of nurturant and involved parenting and higher levels of harsh and controlling parenting (Conger et al. 2002; Cummings et al. 2005; Lovejoy et al. 2000).

Drawing from research pointing to the importance of both adolescent and parent characteristics to parenting behaviors, this study examined the relationship between youth age, sex, externalizing and internalizing behaviors and the warm or harsh parenting practices of their mothers and fathers. Based on previous research (Dietz et al. 2008; Burke et al. 2008), it was anticipated that internalizing and externalizing behaviors would be associated with harsher parenting by mothers and fathers. This study also examined the association between family SES and financial stress on parenting behaviors. Based on previous research, it was anticipated that lower SES, higher levels of financial stress, and greater caregiver depression would be associated with more harsh and less warm parenting. Adding to previous research, this study further explored potential associations between parental control, parental monitoring, family involvement and religiosity on mothers’ and fathers’ warm and harsh parenting practices.

Method

Sample

The sample consisted of 707 community-dwelling adolescents and their mothers or mother figures who participated in a study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and conducted in Santiago, Chile. The entire sample consists of 1,040 adolescents and 902 primary caregivers (mostly mothers or mother figure/female caregiver but also some fathers and other adults who brought the youth to the study). Since data based on adult reports were used in this study, and because most caregivers are mothers or mother figures, for the purpose of the present study the analytic sample consisted of the 707 youth whose mothers or mother figures also participated in the study and for whom no data were missing on the variables included in this study. No significant differences in the participants’ age, gender, and family socioeconomic status existed between the analysis (N = 707) and study samples (N = 1,040).

Procedures

Adolescents and their primary caregivers were interviewed in Spanish, and were interviewed separately in private rooms by Chilean psychologists trained in the administration of questionnaires. The questionnaires were administered at [information deleted for review]. The interviews lasted approximately 2 hours. Adolescents were interviewed about their relationship with their mother and father, family involvement, parental control and autonomy, parental monitoring, and their emotions and behavior and substance use. Primary caregivers were interviewed about depressive symptoms, religiosity, substance use, and financial stressors. Some of the questions were derived from well-established instruments already in use in Chile while others were derived from English language instruments. English language instruments were translated and back translated, reviewed and modified by the research teams in the U.S. and Chile. All instruments were pilot tested to ensure language and conceptual equivalency prior to commencing the study. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of both the U.S. and Chilean collaborating institutions.

Measures

Dependent Variables

The study’s dependent variables were the adolescents’ reports of their mothers’ and fathers’ warm and harsh parenting practices toward the adolescents. We used instruments developed for the U.S. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of early Child Care and Youth Development (Conger and Ge 1999; NICHD 2008). Adolescents were asked to answer questions about their mother’s parenting behaviors first and then about that of their father’s.

Mother’s and Father’s Warm Parenting Behavior

Warm parent behavior towards the adolescent was assessed using nine questions. Sample items included “How often does your _____ (father/mother) let you know he/she really cares about you?” and “Listens carefully to your point of view?”. Response categories were: 1 = Never, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Often, and 4 = Always. Higher scores indicated a warmer parenting behavior. Cronbach’s alpha (Cronbach’s α) for the warm parenting scale for mother was 0.91 and for father was 0.90.

Mother’s and Father’s Harsh Parenting Behavior

The construct of harsh parenting practices was assessed based on the sum of eight questions that described harsh parenting practices. Examples of such items were “How often does your ______ (father/mother) get angry at you?”, “Boss you around a lot”, “insult or swear at you?” Response categories also ranged from 1 = Never to 4 = Always as in the measure of warm parent-adolescent relationship described in the previous paragraph. Higher scores indicated harsher parenting practices towards the adolescent. Cronbach’s α for the harsh parenting scale for mother was 0.79 and for father was 0.80.

Independent Variables

The study’s independent variables consisted of demographic characteristics, youth variables (youth reports of their externalizing and internalizing behaviors, and of their family involvement, parental control/adolescent autonomy, and parental monitoring), and mothers or mother figures’ variables (mothers’ reports of their depression symptoms, religiosity, and financial stress).

Demographic Variables

Demographic variables consisted of adolescents’ self-reported sex and age, the mother’s report of their family’s socioeconomic status and of her marital status (married vs. not married). Because only 576 mothers or mother figures reported their age, we include information on mother’s age in the table that provides descriptive information about the sample but not in the regression analyses due to the large number of missing data on this variable. The socioeconomic status (SES) scale is a composite score based on the linear combination of the mother’s completed years of education, father’s completed years of education, maximum level of combined occupational prestige between mother and father, and family income. SES was standardized so that it has a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1.

Youth Variables

Adolescents’ Emotional and Behavioral Problems

The Child Behavior Checklist Youth Self-Report (CBCL-YSR) was used to collect data pertaining to the adolescents’ behaviors and emotions (Achenbach and Rescorla 2001). This instrument consists of 112 questions that asked participants to describe their behavior during the preceding 6 months. Response options are: 2 = Very true or often true, 1 = Somewhat or sometimes true, 0 = Not true. Examples of items are “I argue a lot”, “I cry a lot”, “I physically attack people”, and “I have a speech problem”. The YSR permits the construction of the following scales by summing the adolescents’ answers to the corresponding items: Externalizing (Cronbach’s α = 0.85) and Internalizing (Cronbach’s α = 0.84) behaviors, with higher scores representing more problems on that construct.

Family Involvement

Adolescents were asked to evaluate family involvement in their lives by answering five items (Riley et al. 1998a, b). The stem question was as follows “Thinking about your family, about how many days in the past 4 weeks did your parents or other adults in your family…” This was followed by items such as “Spend time with you doing something fun”, “Eat meals with you”, and “Talk with you or listen to your opinions and ideas”. Response categories were: 1 = No days, 2 = 1 to 3 days, 3 = 4 to 6 days, 4 = 7 to 14 days, and 5 = 15 to 28 days. A composite score was created by adding the responses of the five questions. A higher score represented more family involvement (Cronbach’s α = 0.72).

Parental Control/Adolescent Autonomy

Adolescents were asked eight questions to assess how decisions were made in their family (NICHD 2008; Brody et al. 1994; Eccles et al. 1991). Adolescents were first told the following: “This next set of questions is about how decisions are made in your family. In your family, how do you make most of the decisions about the following topics?” Examples of questions are “How late you can stay up on a school night”, “Which friends you can spend time with”, “Which after-school activities you take part in”, and “What you do with your money.”. The response categories were scored using the following 5-point scale: 1 = “My parent(s) decide”, 2 = “My parents decide after discussing it with me”, 3 = “We decide together”, 4 = “I decide after discussing it with my parents”, and 5 = “I decide all by myself.” A composite score was created by adding the responses to the eight questions. A higher score represented greater autonomy and less parental control (Cronbach’s α = 0.70).

Parental Monitoring

To evaluate parental monitoring of adolescents, participants were asked ten questions (NICHD 2008). Sample questions included “If your mom/dad or guardian are not at home, how often do you leave a note for them about where you are going?”, “Are there kids your mom/dad or guardians don’t allow you to hang out with?”, and “How often, before you go out, do you tell your mom/dad or guardian when you will be back?”. Response categories were: 1 = All of the time, 2 = Most times, 3 = Sometimes, 4 = Hardly ever, 5 = Never. After reverse scoring the corresponding items, a composite score was created by adding the responses to the 10 questions with higher scores representing more parental monitoring (Cronbach’s α = 0.67).

Mother/Mother Figure Variables

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were measured by asking mothers or mother figures questions from the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale. The CES-D is a validated 20-item questionnaire that assesses the duration and frequency of depressive symptoms based on respondents’ self-reported feelings during a previous week (Radloff 1977). This scale is appropriate for use with nonclinical samples. This measure includes 16 items with negative valence. Sample items include “I felt sad” “I had crying spells”, and “I felt lonely”. The scale also included 4 items with positive valence. Sample items include “I feel happy” “I enjoyed life”, and “I felt that I was just as good as other people”. Response categories were: 0 = Rarely or none of the time (<1 day), 1 = Some or a little of the time (1–2 days), 2 = Occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3–4 days), 3 = Most or all of the time (5–7 days). The four items with positive valence were reverse coded so that higher scores indicated a greater level of depressive symptomatology (Cronbach’s α = .93).

Religiosity

Mothers or mother figures were asked how often in the past year they had attended religious services, not counting weddings, baptisms, bar/bat mitzvahs, funerals or similar religious ceremonies with response categories being as follows: 1 = Never, 2 = a few times a month, 3 = about once a month, 4 = 2–3 times a month, 5 = once a week, and 6 = more than once a week). They were also asked if they currently are involved in any religious youth groups (an organized group of young people that meets regularly for social time together and to learn more about their religious faith) with response categories 1 = No, and 2 = Yes. They were also asked four questions that assessed their intrinsic religiosity. These questions were: How important or unimportant is religious faith in how you live your daily life?, How important or unimportant is religious faith in helping you make major life decisions?, How often do you pray by yourself alone? with response categories being as follows: 1 = Never, 2 = a few times a month, 3 = about once a week, 4 = a few times a week, 5 = about once a day, and 6 = more than once a day. Finally, they were asked if they ever had a religious experience that was very moving and powerful with a Yes = 2, No = 1 response category. A composite score was created by adding the answers to all six questions with higher scores representing greater religiosity (Cronbach’s α = 0.68).

Financial Stress

Mothers or mother figures were asked if in the past 12 months they had experienced any one of the following four types of financial stressors: Job instability of head of household, absence of head of household, important debts, economic stress (significant or habitual) each with dummy-coded response categories (No = 1, Yes = 2). A composite score was created by adding the answers to the four questions with higher scores representing more financial stress (Cronbach’s α = 0.70).

Analyses

Multiple regression analyses were used to analyze the data using a block approach. First, we examined the associations of each dependent variable—warm parenting of mothers and fathers and harsh parenting of mothers and fathers—with the demographic characteristics of youth. Second, youth characteristics were added to the models. Subsequently, the final models consisted of the same analyses but with the addition of the mothers/mother figures characteristics. All analyses were conducted with STATA 11.1 (StataCorp 2010).

Results

The average age of the 707 adolescents was 14 years (SD = 1.4) and the percent of girls was 48 %. The average age of the 707 mothers or mother figures was 40.4 years (SD = 6.2) and 75 % were married (Table 1).

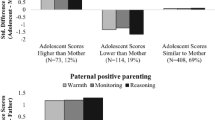

Warm Parenting by Mothers and Fathers

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, results of the analyses that only included the demographic variables as predictors (Model 1 - Demographics columns) indicated that youth age was inversely associated with their reports of warm parenting practices by their mothers and fathers (p < 0.001). The family’s SES was positively associated with youth reporting more warm parenting by their mothers (p < 0.05) but not their fathers (p > 0.05) and youth whose mothers were married reported more warm parenting practices by their fathers (p < 0.05) but not by their mothers (p > 0.05). When youth variables were added to the analyses (Model 2 – Youth variables and demographics), youth externalizing and internalizing behaviors were not associated with reports of warm parenting practices by their mothers and fathers (p > 0.05). However, youth reports of parental monitoring and family involvement were positively associated with youth reporting more warm parenting practices by their mothers and fathers (p < 0.001). In Model 2, the inverse association of the youth age with warm parenting practices by their mothers and fathers remained significant but the association of mother’s marital status with reports of warm parenting practices by the youth fathers became non-significant (p > 0.05). The results of the final model (Full model – Youth and mother variables and demographics), indicated that the addition of the mother/mother figure variables did not contribute to understanding warm parenting practices by mothers and fathers. None of the mother/mother figure variables were significantly associated with the youth reports of warm parenting practices by their mothers and fathers. Therefore, in the full model, the addition of these variables did not change the results of Model 2.

Harsh Parenting by Mothers and Fathers

As shown in Tables 4 and 5, results of the analyses that only included the demographic variables as predictors (Model 1 - Demographics columns) indicated that age was positively associated with the youth reports of harsh parenting practices by their mothers and fathers (p < 0.01). Female adolescents reported less harsh parenting practices by their fathers than boys and youth whose mothers are married reported more harsh parenting practices by their fathers/father figures (p < 0.001). When youth variables were added to the analyses (Model 2 – Youth variables and demographics), externalizing behaviors were positively associated with youth reports of harsh parenting practices by their mothers and fathers and the variables parental control (higher scores representing more youth autonomy) and family involvement were inversely associated with harsh parenting practices by their mothers and fathers. In this model, the association of age, sex, and marital status with harsh parenting practices remained significant as observed in Model 1. The results of the final model (Full model – Youth and mother variables and demographics), indicated that the addition of the mother/mother figure variables did not contribute to explaining variation in harsh parenting practices by mothers and fathers. None of these variables were significant. Consequently, the inclusion of these variables did not change the associations observed in Model 2.

Discussion

Using a sample of Chilean adolescents, the findings of this study suggest that adolescents consider their relationship with both mothers and fathers to be less warm and more harsh as they age. This perception of increasing levels of parental harshness may be related to increasing autonomy and responsibility among adolescents. Indeed, research suggests that as adolescents move into emerging adulthood, a period of development between adolescence and young adulthood, they tend to experience a shift in roles and experiences. For instance, the adolescent might move from a role as a dependent in the family to an individual with greater responsibility (Tanner and Arnett 2009). As adolescents develop, both socially and physically, relationships between adolescents and their families might change, and adolescents might perceive these changes as harsh. One of the implications of this research is that the relationships between adolescents and their caregivers can change across the life course. These are relationships that social workers, particularly social workers that have ongoing or long-term relationships with families, may want to pay closer attention to.

Findings of this study also suggest that although there were no gender differences in adolescent male and female perceptions of warm parenting by their mothers and fathers, female adolescents reported less harsh parenting by their fathers (there were no gender differences in their reports of harsh parenting by their mothers). This finding may reflect a gender bias in parenting practices in Chile, and thus one might potentially conceive of targeted interventions to help reduce the levels of harsh parenting towards adolescent males. Alternatively, as they age, male adolescents may be more likely to perceive parenting as more harsh, perhaps reflecting gender specific changes in the roles or responsibilities that were discussed in the previous paragraph. Further research is needed to better understand the processes that underly gender differences in the harsh parenting of fathers and of male adolescents, particularly in the context of Chilean families.

Interestingly, adolescents reported more harsh parenting practices by their fathers if their mother or mother figure was married, but the mother or mother figure’s marital status was not associated with the youth reports of harsh parenting practices by their mothers. It may be that in families where the parents are married the father is more involved in parenting and family life overall leading to this perception of higher levels of paternal harshness. Alternatively, fathers who are separated from adolescents’ mothers and therefore likely to see their children less often, may engage in more lenient or less harsh parenting practices. It is also an interesting finding that the adolescents did not report differences in harsh parenting by their mothers or mother figures according to whether their mother or mother figures were married or not. Future research is needed to understand the experiences of Chilean women who are mothers and not married in obtaining support from their extended families and others to engage in similar levels of warm and less harsh parenting as their married counterparts. Identifying these sources of support would be key to connecting these women with the resources and support needed to improve their relationships with their children.

In this study, youth behavioral problems were not associated with warm parenting practices, but externalizing behaviors were associated with more reports of harsh parenting practices by both mothers and fathers. Consistent with previous research, it seems plausible that adolescents who exhibit more externalizing behaviors (aggressive and rule-breaking behaviors) may tend to elicit harsher parental behaviors (Burke et al. 2008; Neppl et al. 2009), although the directionality of these effects is unclear in this cross-sectional study. What is interesting from both a research and a practice perspective is that, as discussed in more detail below, factors other than the child’s own self-report of internalizing or externalizing behavior were associated changes in the level of parental harshness or parental warmth. Such a finding suggests that rather than being elicited by adolescent behavior, parental warmth or parental harshness may be part of a larger constellation, or parental style, of parenting behavior.

Adding to previous research, findings from this study point to the importance of parental monitoring and family involvement to mothers’ and fathers’ warm and harsh parenting practices. Specifically, parental monitoring and family involvement were both positively associated with youth reporting warmer parenting practices by both mothers and fathers. Parental monitoring may improve the quality of the relationship between parents and adolescents. One might imagine that higher parental monitoring could potentially be perceived as higher levels of intrusiveness, and thus could be perceived as undesribable by adolescents. In contrast, our findings suggest that higher levels of parental monitoring are associated with improved relationships between parents and adolescents. Indeed, it is plausible that parental monitoring may lead adolescents to believe that their parents are caring and are concerned about their whereabouts and experiences. Thus, parental monitoring may create a warmer adolescent-parent relationship. This finding is consistent with prior research suggesting that fathers who exhibited high parental involvement, monitoring, and open communication, among other characteristics, had children who reported less externalizing behaviors (Amato and Gilbreth 1999; Han et al. 2012). In addition, a child’s life satisfaction has been positively correlated with father’s intrinsic support, characterized by trust, encouragement, and the discussion of problems between father and child (Young et al. 1995). Our findings suggest additional rationale for family interventions that provide parents with the skill set to increase their monitoring of their adolescents’ activities.

Findings from this study also suggest that difficulties in parent–child relationships may be ameliorated by positive and healthy family and parenting practices. Family involvement was not only positively associated with youth reporting more warmer parenting practices by their parents but also with reporting less harsh parenting practices by both parents. These findings support prior research about paternal involvement being important in an adolescent-father relationship (Veneziano 2003). When parents create a family environment in which members are invested in and accountable for each others’ daily activities they are more likely to also be warm and caring towards their children. In an involved family environment, parents may be less likely to engage in harsher discipline. This finding suggests that the degree to which families engage in family routines, share details of their everyday lives, and spend time in pleasant activities is an aspect of a family environment in which adolescents feel included, cared for and respected. This type of environment may also serve to subsequently protect adolescents against getting involved in risky behaviors. Research has shown that higher frequencies of family dinners, an aspect of family involvement, are associated with less delinquency for girls indicating that efforts to promote family involvement may be particularly important in families with adolescent females. Finally, decreased parental control/increased adolescent autonomy was associated with less youth reports of harsh parenting practices by their mothers and fathers. It is plausible that with autonomy and independence parents are less likely to engage in harsher disciplinary practices. Thus, interventions specifically targeting the construct of family involvement may prove fruitful for social workers working with families and adolescents.

In contrast to previous research, none of the mother or mother figure variables were significant when adolescent and family characteristics were taken into consideration. We expected that youth whose parents reported more depressive symptoms and financial stress would differ in their reports of their parents’ warm and harsh parenting practices because stress related to mental health and financial problems could affect parent’s relationships with their children. These findings suggest that family involvement, parental monitoring and increased adolescent autonomy may be more salient predictors of parenting behaviors than parent mental health or financial difficulty. As such, efforts to promote such positive parenting practices may be able to circumvent some of the negative effects financial and emotional stress can have on the parent–child relationship.

It may also be that the potentially negative influences of the mother or mother figures’ depressive and financial problems are ameliorated by other family characteristics not measured in this study. For example, as we indicated in the introduction, the majority of children in Chile live with their extended family. In 2006 it was estimated that two-thirds of Chilean households had one or more extended family member living together (i.e., grandparents, cousins, uncles, aunts) (Pallisgaard 2007). Further understanding the role of the extended family in these multigenerational families could help shed light into the protective influences they may have on children, especially when parents or primary caregivers suffer from mental health and financial problems.

Study Limitations

These study findings should be considered in the context of the following limitations. First, the study is based on adolescents’ reports of their parent’s warm and harsh parenting practices rather than through information from multiple sources, including observations by independent observers, leaving room for possible bias such as the adolescent over reporting or underreporting the extent to which their caregivers’ parenting practices are warm and harsh. However, we do think that independent of whether adolescents may have over or underreported, the perceptions of their parents’ behaviors are actually an important reflection of their lived experiences and as such should not be discounted. Second, the study design is cross-sectional limiting what one can say about temporal associations among the variables studied with the exception of the demographic controls. Longitudinal studies with independent observers who could independently assess the quality of the relationships between family members would serve to better understand the dynamics observed in this study. Third, because the sample was reduced due to adolescents who did not have a father present in their lives, the generalizability of the analysis for adolescents who do not live with both parents due to divorce, father abandonment, or death, is limited. Notwithstanding these limitations, strengths of this study include one of the few studies in South America that investigated parent–child relationships using a comprehensive set of constructs that distinguished warm and harsh parenting practices by mothers and fathers and that included independent reports of individual and family behaviors by adolescents and reports of behaviors by their mothers or mother figures, using a relatively large community-based international sample of adolescents.

Conclusion

In conclusion, relatively few studies have attempted to use individual and family factors to assess the quality of a parent–child relationship, especially the father-adolescent relationship. Instead, the focus has generally been towards using quality of parent–child relationships to explain adolescent behaviors. These findings with an international sample suggest that despite developmental emancipation and mental health problems adolescents may experience, family involvement, parenting monitoring and parental autonomy-granting promote positive parent–child relationships for both mothers and fathers.

Traditionally, due to gender expectations, mothers have been perceived as caring and compassionate and spending the most time with children. However, this study highlights the importance of studying fathers as well, particularly due to gender differences observed in adolescents’ perception of fathers’ harsh parenting. Results from this study further suggest that positive parent–child relationships may be facilitated not just by monitoring where adolescents are but also through having close relationships with them and by creating a family environment in which members of the family interact positively with each other. In order to facilitate such relationships, social workers must understand the contexts in which these families live.

References

Achenbach, T. M. & Rescorla, L. A. Child Behavior Checklist. Youth Self-Report for Ages 11–18 (YSR 11–18). (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles. Burlington: Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families.

Amato, P. R., & Gilbreth, J. G. (1999). Nonresident fathers and children’s well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 61, 557–573.

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioecommic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 371–399.

Bradley, R. H., Corwyn, R. F., Burchinal, M., McAdoo, H. P., & Coll, C. G. (2001). The home environments of children in the United States part II: Relations with behavioral development through age thirteen. Child Development, 72, 1868–1886.

Brannigan, A., Gemmell, W., Pevalin, D. J., & Wade, T. J. (2002). Self-control and social control in childhood misconduct and aggression: The role of family structure, hyperactivity, and hostile parenting. Canadian Journal of Criminology, 44(2), 119–142.

Brody, G. H., Moore, K., & Glei, D. (1994). Family processes during adolescence as predictors of parent-young adult attitude similarity. A 6-year longitudinal analysis. Family Relations, 43, 369–373.

Burke, J. D., Pardini, D. A., & Loeber, R. (2008). Reciprocal relationships between parenting behavior and disruptive psychopathology from childhood through adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36, 679–692.

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Elder, G. H., Lorenz, F. O., Simons, R. L., & Whitbeck, L. B. (1992). A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development, 63, 526–541.

Conger, R. D., & Ge, X. (1999). Conflict and cohesion in parent-adolescent relations: Changes in emotional expression from early to mid-adolescence. In M. J. Cox & J. Brooks-Gunn (Eds.), Conflict and cohesion in families: Causes and consequences (pp. 185–206). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y. M., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African-American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38, 179–193.

Cummings, E. M., Keller, P. S., & Davies, P. T. (2005). Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: Exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 479–489.

Denissen, J. J. A., Van Aken, M. A. G., & Dubas, J. S. (2009). It takes two to tango: How parents’ and adolescents’ personalities link to the quality of their mutual relationship. Developmental Psychology, 45, 928–941.

Dietz, L. J., Birmaher, B., Williamson, D. E., Silk, J. S., Dahl, R. E., Axelson, D. A., et al. (2008). Mother-child interactions in depressed children and children at high risk and low risk for future depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 574–582.

Eccles, J., Buchanan, C. M., Flanagan, C., Fuligni, A., Midgley, C., & Yee, D. (1991). Autonomy versus control during early adolescence. Journal of Social Issues, 47, 53–68.

Gershoff, E. T., Grogan-Kaylor, A., Lansford, J. E., Chang, L., Zelli, A., & Deater-Deckard, K. (2010). Parent discipline practices in an international sample: Associations with child behaviors and moderation by perceived normativeness. Child Development, 81, 487–502.

Han, Y., Grogan-Kaylor, A., Delva, J., & Castillo, M. (2012). The role of peers and parents in predicting alcohol consumption among Chilean youth. International Journal of Child and Adolescent Health, 5(1), 53–64.

Herrera, S. (2008). Parentelidad y educación de los hijos. In M. Alam (Ed.), Encuestra Nacional Bicentenario Universidad Católica – Adimark: Una Mirada al Alma de Chile (pp. 9–19). Alemeda: Pontifica Universidad Católica de Chile.

Laskey, B. J., & Cartwright-Hatton, S. (2009). Parental discipline behaviours and beliefs about their child: associations with child internalizing and mediation relationships. Child Care Health and Development, 35, 717–727.

Lovejoy, M. C., Graczyk, P. A., O’Hare, E., & Neuman, G. (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20, 561–592.

McLoyd, V. C. (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist, 53, 185–204.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of early Child Care and Youth Development. Phase IV Instrument Documentation (2008). https://secc.rti.org/Phase4InstrumentDoc.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2009.

Neppl, T. K., Conger, R. D., Scaramella, L. V., & Ontai, L. L. (2009). Intergenerational continuity in parenting behavior: mediating pathways and child effects. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1241–1256.

Pallisgaard, A. (2007). Single person households double in chile. http://www.santiagotimes.cl/santiagotimes/index.php/2007100111833/news/cultural-news/single-person-households-double-in-chile.html. Accessed 11 Aug 2009.

Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Dishion, T. J. (1992). Antisocial boys. Eugene: Castilia.

Radloff, L. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Reid, J. B., Patterson, G. R., & Snyder, J. (2002). Antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: A developmental analysis and model for intervention. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Riley, A. W., Forrest, C. B., Starfield, B., Green, B., Kang, M., & Ensminger, M. E. (1998a). Reliability and validity of the adolescent health profile-types. Medical Care, 36, 1237–1248.

Riley, A. W., Green, B. F., Forrest, C. B., Starfield, B., Kang, M., & Ensminger, M. E. (1998b). A taxonomy of adolescent health: development of the adolescent health profile-types. Medical Care, 36, 1228–1236.

Rohner, R. P., & Britner, P. A. (2002). Worldwide mental health correlates of parental acceptance-rejection: Review of cross-cultural and intracultural evidence. Cross-Cultural Research, 36, 16–47.

Rohner, R. P., Khaleque, A., & Cournoyer, D. E. (2005). Parental-acceptance-rejection: Theory, methods, cross-cultural evidence, and implications. ETHOS, 33, 299–334.

Rohner, R. P., & Veneziano, R. A. (2001). The importance of father love: History and contemporary evidence. Review of General Psychology, 5, 382–405.

Scaramella, L. V., & Leve, L. D. (2004). Clarifying parent-child reciprocities during early childhood: The early childhood coercion model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 7, 89–107.

Skopp, N. A., McDonald, R., Jouriles, E. N., & Rosenfield, D. (2007). Partner aggression and children’s externalizing problems: Maternal and partner warmth as protective factors. Journal of Family Psychology, 21(3), 459–467.

StataCorp. (2010). STATA - data analysis and statistical software. College Station.

Tanner, J. L., & Arnett, J. J. (2009). The emergence of ‘emerging adulthood’: The new life stage between adolescence and young adulthood. In A. Furlong (Ed.), Handbook of youth and young adulthood: New perspectives and agendas (pp. 39–45). London: Routledge.

Veneziano, R. A. (2003). The importance of paternal warmth. Cross-Cultural Research, 37(3), 265–281.

Young, M. H., Miller, B. C., Norton, M. C., & Hill, E. J. (1995). The effect of parental supportive behaviors on life satisfaction of adolescent offspring. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57(3), 813–822.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to particularly thank the adolescents and their families for their participation in this study. We are also thankful to the project staff at the Instituto de Nutrición y Tecnología de los Alimentos (INTA), Universidad de Chile for their dedication to the project. This study was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (R01-DA021181) and received support from the Vivian A. and James L. Curtis School of Social Work Research and Training Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ho, M., Sanchez, N., Maurizi, L.K. et al. Examining the Quality of Adolescent–Parent Relationships Among Chilean Families. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 30, 197–215 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-012-0289-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-012-0289-6