Abstract

This aim of this study is to examine predictors of specific motivations for engaging in cutting behavior among a community sample of sexual minority youth. The study involved secondary analysis of data collected by a community-based organization serving lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth and their allies. Descriptive and logistic regression analyses were conducted using a final sample of 131 sexual minority youth ages 13–24. Analyses indicate that cutting occurs at high rates among sexual minority youth and that certain demographic characteristics, psychosocial variables, and mental health issues significantly predict endorsement of particular motivations for cutting among youth in this sample. Implications for social work assessment and intervention with sexual minority youth are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Non-suicidal self-injurious (NSSI) behavior among youth and young adults, such as cutting, hitting or burning oneself without suicidal intent, has started to receive increased attention from research and practitioner communities (Whitlock 2010). This may be due to an increasing prevalence of these behaviors among young people (Klonsky et al. 2003; Whitlock et al. 2006). While recent research has expanded our understanding of the prevalence, risk factors, and forms of NSSI among youth, little is known about youths’ motivations for engaging in NSSI (Laye-Gindhu and Schonert-Reichl 2005). Moreover, research on NSSI behaviors among sexual minority youth—those who identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBT)—has been largely absent from the literature (Alexander and Clare 2004; Walls et al. 2010b).

In this study, we examine predictors of different motivations of one specific form of NSSI—cutting behavior—among a sample of sexual minority youth who report having engaged in the behavior in the previous year. Specifically, we investigate the relationship between demographic characteristics and experiences known to be associated with risk for cutting and perceived motivation for cutting among sexual minority youth. This study contributes to the literature in that it focuses on an under-served population of youth and integrates knowledge about risk and protective factors to predict motivations for cutting. By examining which demographic and psychosocial characteristics predict different motivations for the behavior, our hope is to begin to outline a profile to aid practitioners in tailoring their harm reduction interventions with these young people to address the underlying motivations for the behavior. In this way, we hope to begin to build a bridge between risk and protective factors, motivations, and intervention strategies for cutting among sexual minority youth.

Literature Review

Prevalence

An estimated one to four percent of the general population has engaged in NSSI (Briere and Gil 1998; Klonsky et al. 2003). Rates are highest among adolescents and young adults, ranging from between 12 and 21% (Favazza 1996; Favazza et al. 1989; Ross and Heath 2002; Whitlock et al. 2006), with estimates of NSSI among college students being as high as 25% (Klonsky and Olino 2008).

Results regarding differences in prevalence of NSSI among males and females have been mixed. Some studies have found that females are more likely to self-injure (e.g., Robinson and Duffy 1989; Smith et al. 1998), while others have found no significant gender differences (Garrison et al. 1993; Gratz et al. 2002; Tyler et al. 2003). However, research suggests that males and females may differ in regards to the form and function of self-harming (Laye-Gindhu and Schonert-Reichl 2005; Tyler et al. 2003), which may, in part, explain the mixed results found regarding prevalence and gender. Little is known about NSSI among transgender individuals of any age (for an exception, see Walls et al. 2010b). Racial/ethnic difference in self-harming behavior have not been thoroughly studied (Prinstein 2008), however existing results suggest that there are not significant differences (Klonsky and Olino 2008).

Risk Factors

Particular mental health issues such as borderline personality disorder (Linehan 1993), negative affect (Armey and Crowther 2008; Klonsky and Olino 2008; Nock and Mendes 2008), and depression and anxiety (Andover et al. 2005; Klonsky et al. 2003; Whitlock et al. 2006) are associated with increased risk for NSSI behaviors. A history of physical or sexual abuse also increases the risk of engaging in NSSI (Himber 1994; Weierich and Nock 2008), as does a lack of social support and feelings of loneliness (Wichstrøm 2009).

Though NSSI is distinct from suicidal thoughts and behaviors, the two are inter-related. NSSI has been associated with a history of suicide attempts (Brown et al. 2002; Stanley et al. 1992) and engaging in self-harm is considered to be a risk factor for suicidality (Comtois 2002; Glenn and Klonsky 2009; Whitlock and Knox 2007). Some conceptualize NSSI existing on a self-harm continuum with suicide at the far extreme (Brausch and Gutierrez 2009).

Function

Recent research has begun to explore the function of self-harming behavior. Across the literature, the terms function, motivation, and reasons for engaging in self-harm are typically used interchangeably to understand the “whys” of NSSI (see for example Klonsky 2007; Laye-Gindhu and Schonert-Reichl 2005; Nock and Prinstein 2004). For clarity, we will use the term motivation in this paper to refer to the reasons youth offer to explain why they cut.

The motivation most commonly associated with NSSI is emotional regulation (Klonsky 2007). People who endorse this motivation use self-harm as a way to manage negative cognitions about the self (Chapman et al. 2006), avoid or minimize negative feelings (Favazza and Conterio 1988; Nock and Prinstein 2005), generate positive feelings or remove feelings of numbness (Nock and Prinstein 2005), particularly around interpersonal stressors such as conflicts in relationships or traumatic experiences (Crowe 1997; Levenkron 1998; Simeon and Favazza 2001; Tantam and Whittaker 1992). Others have suggested that NSSI may be motivated by a desire to self-punish or to cope with feelings of self-loathing (Klonsky 2007). NSSI may also serve as a mechanism for translating emotional pain into physical pain, which can be understood as a means of communication, self-medication, or both (Figueroa 1988). Paradoxically, NSSI may serve a protective function in helping people cope and thus preventing suicide attempts (Connors 2000; Klonsky 2007). Empirical evidence indicates that a person may endorse multiple motivations for self-harm and that the motivation(s) may even differ for each instance of self-harm (Klonsky 2007).

Scholars emphasize the importance of examining motivation for self-harm due to its potential utility in guiding therapeutic intervention. Klonsky (2007) suggests that an understanding of function may allow practitioners to classify sub-populations of people who engage in self-harm. Furthermore, a functional lens may help practitioners formulate more effective treatment plans that adjust the type and level of treatment based on the clients’ perceived motivation (Klonsky 2007).

NSSI Among Sexual Minority Youth

Though there is a growing body of research on suicidality among sexual minority youth, little is known about self-harming behaviors where suicide is not the intended outcome. Extant research indicates that sexual minority youth report higher rates of NSSI as compared to general adolescent populations. In two different studies involving community samples of sexual minority youth and young adults (between the ages of 13 and 22), most of whom access community-based support services or attend social events sponsored by an LGBT organization, between 42% and 47% of the samples had engaged in cutting behavior in the previous year (Walls et al. 2007, 2010b). In a representative sample of 9th to 12th graders in Massachusetts, Almeida et al. (2009) found that, while only 14.3% of sexual minority females engaged in cutting, 41.7% of sexual minority males did, suggesting a gendered difference in prevalence among sexual minority youth.

Results regarding differential risk for self-injurious behaviors based on sexual orientation or gender identity have been equivocal. Skegg et al. (2003) study of 942 twenty-six year-olds in New Zealand found that participants who reported same-sex attraction were more likely than those attracted only to people of the opposite sex to self-harm. Same-sex attracted males were at significantly higher risk for self-harm than were women with same-sex attraction (Skegg et al. 2003). Similarly, Almeida et al. (2009) found significantly higher rates of self-harm behaviors among sexual minority 9th—12th graders than among their heterosexual counterparts. However, Whitlock and Knox (2007) found that gay- and lesbian-identified college students were not at higher risk for self-injurious or suicidal behaviors (combined) than heterosexual students, but that bisexual and questioning students were. Because their study combined suicidal behaviors with NSSI behaviors, it is difficult to discern whether the results are confounded because of the lack of differentiation between the two behaviors. Another study on cutting behavior among a community sample of sexual minority youth found that lesbian and bisexual female youth were more likely to cut than gay and bisexual male youth, but that transgender youth were at the highest risk for cutting behavior (Walls et al. 2010b).

The risk of engaging in NSSI is not constant across all groups of sexual minority youth, but varied based on various psychosocial characteristics. Homeless sexual minority youth appear to be particularly vulnerable to the behavior (Walls et al. 2007, 2010b), as do those who experience physical abuse and/or bullying at school or in their home (Walls et al. 2010b). As with general youth and adult populations (Whitlock et al. 2006), depression and persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness as well as suicidality are correlated with increased risk (Walls et al. 2010b). Likewise having a social network with increased prevalence of suicidality among friends appears to be related to higher levels of risk for engaging in the behavior (Walls et al. 2010b). In terms of protective factors, knowing a safe adult is associated with a decreased risk of engaging in cutting (Walls et al. 2010b). Though these studies are limited to a focus on cutting as one form of NSSI and samples primarily from one geographic area, they provide initial insight to potential risk and protective factors among this population of youth.

One interesting risk for engaging in NSSI among sexual minority youth and young adults is the finding by Walls et al. (2010b) that those who were more open about their sexual orientation were at increased risk for engaging in cutting. At first, this finding may seem to be counterintuitive as openness about sexual orientation is most commonly associated with better integration of one’s sexual identity and improved mental health outcomes (Alexander and Clare 2004; Bybee et al. 2009). However, research suggests that sexual minorities who come out earlier often experience more negative reactions from their environments including greater levels of invalidation, bullying and harassment (Pilkington and D’Augelli 1995). Given the documented linkage between victimization and increased likelihood of self-harming behavior (Almeida et al. 2009; Rivers 2000), Walls et al. (2010b) suggest that more openness and younger ages of disclosure of sexual orientation may be correlated with increased risks of NSSI because of the increased levels of rejection and microaggressions experienced by these youth, at a time when peer acceptance is critically important developmentally.

Few studies have directly examined sexual minorities’ motivations for engaging in self-harm. Alexander and Clare (2004) and Scourfield et al. (2008) found that self-hatred, internalized oppression, and self-punishment were motivations for NSSI among LGBT youth and adults. Likewise, Babiker and Arnold (1997, see also Favazza 1996) identify low self-esteem and self-loathing as motivators. This may be particularly salient among sexual minority youth due to living in climates hostile to their sexual or gender identities. Individuals who experience their environment as invalidating based on marginalized social identities may be more prone to developing self-injurious behaviors (Alexander and Clare 2004) and therefore engaging in self-harm as a way of coping with discrimination and rejection. For example, Almeida et al. (2009) found that sexual minority youth who perceived themselves as having been a target of discrimination were at an elevated risk for self-harming behaviors. This lends support to this assertion that one motivation for engaging in NSSI may be underlying feelings of self-loathing arising from experiences of such invalidating environments. It is also important to emphasize that sexual minority youth likely endorse multiple motivations for engaging in self-harm over time and that the relationship between sexual orientation and self-harm is complex (Scourfield et al. 2008).

Research Questions

A review of the literature indicates that certain demographic and psychosocial characteristics are associated with increased risk of engaging in cutting behavior among general and sexual minority youth samples. However, less is known about motivations for engaging in cutting behavior, particularly among sexual minority youth. In order to contribute to knowledge about cutting among sexual minority youth, we endeavor to explore the relationships between risk and protective factors and motivation. Our analysis is based upon the following research questions:

-

(1)

Which motivations for cutting are most commonly endorsed among sexual minority youth? Do youth report single or multiple motivations for cutting?

-

(2)

Can certain demographic characteristics or experiences associated with risk for cutting predict specific motivations for cutting among a convenience sample of sexual minority youth?

We expect that, similar to the general population, emotion regulation will be a predominant motivation for cutting among sexual minority youth. Given the emerging understanding of the relationship between internalized oppression and cutting, we also expect that self-hatred will be a commonly endorsed motivation. Additionally, we anticipate that most youth in the sample will endorse multiple motivations for cutting. Given the paucity of research on the relationship between risk/protective factors and motivation, we did not develop a priori hypotheses about which characteristics might predict specific motivations. Rather, we approach the regression analysis as exploratory in nature.

Method

Participants

Rainbow Alley, a program of the GLBT Community Center of Colorado (The Center), provides support, advocacy, education, social events, and youth leadership opportunities to LGBT youth and their allies ages 13–21, utilizing a youth empowerment model that strives to involve youth in decision-making at all levels of the program. Beginning in 2006, the program conducted an annual web-based survey of youth as part of its programmatic evaluation process. Youth involved with Rainbow Alley were invited to participate in the survey, with staff emphasizing that participation was voluntary and would not impact eligibility for services. Additional survey participants were recruited at social events and community-based programs. The link to the survey was also displayed on The Center’s website to allow youth who were not directly connected to the program to participate in the survey.

Rainbow Alley serves a diverse group of young people within and outside of the Denver metro area, making it difficult to generalize about the service recipients. Although the Center is located in Denver, Colorado, Rainbow Alley serves youth from urban, suburban, and bedroom communities. Based on data gathered in past Rainbow Alley surveys, an estimated 44–56% of youth participants are female, 38–51% are male, and 4–6% identify as transgender or genderqueer (Walls et al. 2007, 2008, 2010a, b). The race/ethnicity of youth who have participated in recent surveys indicate that between 39 and 74% are White, 7–28% are biracial/multiracial, 6–20% are Latino/a, 5–10% are Black/African American and fewer than 5% are Asian American or Native American (Walls et al. 2007, 2008, 2010a, b). Approximately 38.5% of youth participants in one survey year had been homeless in the past 12 months (Walls et al. 2010b). Although the psychosocial characteristics of sexual minority youth who completed the on-line survey may not correlate directly with those of youth who receive services at Rainbow Alley, these data provide some indication of the demographics of the organization’s typical service recipients.

All participants completed an electronic consent form before beginning the survey and data were compiled anonymously with no link to identifying information. Though it was possible that a participant may have completed the survey more than once, this was not an anticipated outcome due to survey length and lack of incentives. Secondary data analyses reported here were approved by the institutional review board of the University of Denver.

The sample consisted of 349 participants who identified as sexual minority youth and were in the age range of the study. Of those, 15 (4.5%) were dropped as they failed to answer the variable of interest, How many times during the last 12 months did you cut yourself on purpose? leaving a sample size of 334. As the analyses are focused on reasons for cutting behavior rather than on risk or likelihood of cutting, only those LGBT youth who reported engaging in the behavior (n = 131) were retained in the final sample. Missing data were assessed for demographic and independent variables of interest. Only 6.1% of cases were missing data on any of the variables used for the analysis. Multiple imputation by chained equations (van Buuren et al. 1999) was used to address issues of missing data.

Measures

In addition to demographic variables, other potential predictors that have been identified in the literature that were available in the dataset were included in analyses. The majority of the measures utilized in the survey were adapted from the National Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2011) and have been used by Rainbow Alley to track demographic, behavior, and service usage trends since 2004.

Participants were asked numerous demographic questions, including age, gender identity, and race/ethnicity. Gender identity response options included female, male, male-to-female transgender, female-to-male transgender, gender variant/genderqueer, or other. Gender identity was coded dichotomously, including female, transgender, and gender variant/genderqueer youth in one category and males as the reference group.Footnote 1 Participants identified their race/ethnicity as American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian/Asian American, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino/a, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, White, bi/multi-racial, or other.Footnote 2

In order to assess motivations for cutting behavior, participants were asked the following question: Thinking about when you cut yourself, which of the following explain why you cut yourself (check all that apply). The response options for motivations for cutting behavior were developed based on the literature in this area and included I felt lonely, I needed stimulation, I hated myself, Cutting made me feel something, and Cutting gave me an emotional release. Participants were encouraged to select all reasons that applied to them and responses were measured dichotomously to indicate whether someone endorsed cutting for that reason or not. Participants were also given the option to select other and provide a qualitative response indicating an alternative explanation for their cutting behavior. The qualitative responses were analyzed and the majority were recoded into existing categories, with the remainder categorized as cutting is pleasurable (n = 7) or as other (n = 3), though the sample sizes for these responses were too small to be included as dependent variables in the current analysis.

Three questions were analyzed regarding depressive symptoms and suicide risk. First, participants were asked whether they experienced persistent sadness or hopelessness in the previous 12 months using a dichotomous response option (yes/no). A second question inquired about the number of times that a participant had attempted suicide within the previous 12 months, with responses ranging from 0 times to 6 or more times. This question was re-coded dichotomously to indicate whether or not a participant had recently attempted suicide rather than measuring the number of times they attempted. A third question asked about the number of a participants’ friends who had attempted suicide, with response options ranging from 1 = none of my friends have attempted suicide to 6 = most of my friends have attempted suicide.

Participants were asked whether they had been harassed at or near school in the past year (or during their last year at school if they no longer were enrolled) because of their actual or perceived sexual orientation and/or gender identity. The responses were measured dichotomously to indicate the absence or presence of LGBT-related harassment. Another question asked about the presence of a safe adult (e.g., teacher, counselor, social worker, etc.) at school with whom participants could talk about their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Once again youths’ responses were measured dichotomously to indicate the presence or absence of a safe adult. Finally, participants were asked to indicate the degree to which they are open to others about their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Response options ranged from 1 = very open to 5 = not open at all. For ease of interpretation, responses were reverse coded so that higher numbers represent greater levels of openness.

Analysis

Our initial analysis involved examination of the descriptive statistics, including analysis of which motivations were most frequently endorsed by youth in the sample and whether youth tended to endorse singular or multiple motivations. Next, we conducted five logistic regression models to predict the likelihood of engaging in cutting behavior for each of the motivations outlined above. The eight predictor variables included in the models were described above (age, gender identity, LGBT-related harassment at school, presence of a safe adult at school, sad/hopeless feelings, suicide attempt, friends’ suicide attempts, and level of openness).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Slightly more than half (53.4%, N = 70) of the participants identified as female, while 32.8% (n = 43) identified as male, and 13.8% (n = 18) identified as transgender, gender variant, or genderqueer. Participants’ ages ranged from 13 to 24, with a mean age of 17.12 (SD = 2.17). The majority (67.2%, n = 88) of participants were White, while the next largest racial/ethnic group represented was bi/multi-racial (15.3%, n = 20), followed by Latino/a (10.7%, n = 14) and American Indian (2.3%, n = 3). The remaining 4.7% of the participants self-identified as Asian, African American or “other” race. Among youth in the sample, nearly a quarter (23.7%, n = 31) had engaged in cutting once in the past 12 months. Slightly fewer (22.9%, n = 30) had cut between 2 and 3 times, 12.2% (n = 16) had cut 4 or 5 times, and 41.2% (n = 54) had cut 6 or more times in the past year.

Independent Variables

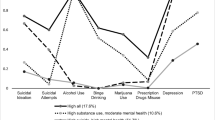

Two-thirds of participants (66.4%, n = 87) reported having been harassed at school in the past year due to sexual orientation and/or gender identity. More than half (59.5%, n = 78) indicated that they had a safe adult at school. A considerable majority of youth (81.7%, n = 107) reported feeling so sad or hopeless for at least two weeks in a row in the previous year that it interfered with their usual activities. More than a third of the participants (38.9%, n = 51) had attempted suicide at least once in the previous 12 months. Only 12.2% (n = 16) reported that none of their friends had ever attempted suicide. The largest group, 45.8% (n = 60) reported that a few of their friends attempted suicide, while 25.2% (n = 33) said that some friends had attempted suicide, and 12.2% (n = 16) said a lot of their friends attempted suicide. Six people (4.6%) said most of their friends had attempted suicide. Nearly half (49.6%, n = 65) described themselves as very open about their sexual orientation and/or gender identity, 30.5% (n = 40) as somewhat open, 11.5% (n = 15) as slightly open, 6.1% (n = 8) hardly open at all, and 2.3% (n = 3) not at all open.

Dependent Variables

Nearly three-fourths of participants (72.5%, n = 95) reported that they engaged in cutting behavior in order to experience an emotional release, making this the most cited motivation for cutting among youth in the sample. Just over half (51.9%, n = 68) of participants reported that they cut in order to feel something. Fewer than half (48.9%, n = 64) reported hating themselves as a motivation for cutting. Similarly, 47.3% (n = 62) of youth in the sample reported feeling lonely as a motivation for their cutting behavior. Nearly a third (31.3%, n = 41) reported needing stimulation as a motivation for cutting. Only 5.3% (n = 7) of responses indicated they cut to experience pleasure (qualitative responses). Considering the quantitative and qualitative responses to motivations for cutting combined, 31 (23.7%) participants endorsed one motivation, 32 (24.4%) endorsed two motivations, 30 (22.9%) endorsed three motivations, 22 (16.8%) selected four motivations, and 13 (9.9%) endorsed five or more motivations. Three participants (2.3%) did not indicate any specific motivation for their cutting behavior.

Due to the large proportion of youth who endorsed multiple motivations for cutting, we examined the correlations between each of the dependent variables. Because the variables are dichotomous phi coefficients were used. The results are shown in Table 1. Four weak to moderate bivariate correlations were significant among the following motivations for cutting: (1) loneliness and self-hatred (φ = .419, p < .01); (2) loneliness and feel something (φ = .209, p < .05); (3) stimulation and feel something (φ = .254, p < .01); and (4) emotional release and feel something (φ = .263, p < .01). Such associations were anticipated given the similarities between constructs and existing literature that suggests multiple motivations are common.

Inferential Statistics

Model 1 included the eight independent variables predicting the likelihood of endorsing emotional release as a motivation for cutting. Of the variables examined, gender identity was the only significant predictor in this model. Female, transgender, and gender variant/genderqueer youth were nearly four times as likely as males to report cutting in order to experience an emotional release (OR = 3.95, p < .01).

Model 2 incorporated the independent variables to predict cutting as a motivation to “feel something”. Those who had attempted suicide in the past 12 months were 2.32 times more likely to report cutting in order to feel something than those who had not attempted suicide in the past 12 months (p < .05). Age (OR = .84, p < .10), gender identity (OR = 2.15, p < .10), and experiencing harassment based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity (OR = 2.19, p < .10), were marginally significant in this model. These results suggest that younger adolescents, female and transgender/genderqueer youth, and those who were harassed at school were more likely to endorse this motivation for cutting, though these results must be interpreted with caution as they only reach a marginal level of significance.

Model 3 predicted self-hatred as a motivation for cutting behavior. Only one predictor, feeling sad or hopeless, was significant in this model. Those who felt sad and hopeless for two or more weeks in a row during the past 12 months were 6.49 times more likely than those who did not feel sad or hopeless to endorse self-hatred as a motivation for cutting (p < .01).

Model 4 predicted the likelihood of endorsing loneliness as a motivation for cutting behavior. Three independent variables, friends’ suicide attempts, sad/hopeless feelings, and knowing a safe adult were significant predictors. With every increase in category of the number of friends who have attempted suicide, youth were .36 times less likely to report loneliness as a motivation (p < .05). Those who reported persistent sadness and hopelessness were 5.1 times more likely than those who did not report these feelings to be motivated by loneliness (p < .05). Additionally, those who reported knowing a safe adult at school were approximately half as likely than those who could not identify a safe adult to cut because they felt lonely (OR = .46, p = .05). Level of openness about sexual orientation/gender identity was marginally significant; for every unit increase in openness, youth were 1.5 times more likely to report loneliness as a motivation for cutting (p < .10). As mentioned above, the marginal significance of this relationship should be viewed cautiously.

Finally, Model 5 predicted needing stimulation as a motivation for cutting. None of the predictors reached statistical significance in this model. However, persistent sad and hopeless feelings reached marginal significance. Youth who reported feeling sad and hopeless for at least 2 weeks in the previous 12 months were 3.16 times more likely to endorse cutting to experience stimulation than youth who did not report these feelings (p < .10) (Table 2).

Discussion

This exploratory study sought to examine different motivations for engaging in cutting behavior among sexual minority youth and young adults who engaged in cutting behavior in the previous 12 months. The study’s findings provide an initial understanding of how different experiences, emotional states, or identities may be associated with particular motivations for cutting in this under-studied population of youth.

Our first research question sought to explore the percentage of youth who endorsed specific motivations for cutting. Emotional release was reported as a motivation by nearly three quarters (72.5%) of youth in the sample. This finding supports our hypothesis that emotional regulation would be a commonly endorsed motivation for cutting among sexual minority youth, mirroring results from the general NSSI literature (Klonsky 2007). A slight majority of the sample (51.9%) reported that the desire to “feel something” was a motivation for cutting and 31.3% endorsed needing stimulation as a motivation for cutting. Both of these motivations can also be understood as attempts to regulate emotions by abating feelings of numbness (Nock and Prinstein 2005), providing additional support to our hypothesis. Loneliness was endorsed as a motivation for cutting by 47.3% of youth in the sample. This motivation cannot be clearly understood as emotional regulation, though it may be related to interpersonal stressors and social alienation that contribute to negative emotional states. Moreover, slightly fewer than half (48.9%) reported self-hatred as a motivation for cutting, which supports our hypothesis that this would be a commonly endorsed motivation among a sample of youth who regularly experience discrimination and rejection based on their identities. Our hypothesis that the majority of sexual minority youth would endorse multiple motivations for cutting was also confirmed by the data. This finding was not surprising, given the complexity of NSSI behaviors and sexual minority youths’ lives.

Our second research question aimed at examining whether certain factors or characteristics associated with risk for NSSI could predict particular motivations for cutting. Once again, we were not driven by a priori hypotheses. Rather, we approached this as an opportunity to explore potential relationships between risk and motivation. Given the exploratory nature of this study, marginally significant results are reported to suggest future directions in research, though the authors emphasize that caution must be used when interpreting marginally significant findings.

Gender identity was a significant predictor of emotional release as a motivation for cutting and was a marginally significant predictor of cutting in order to feel something, but did not predict differential likelihood of endorsing self-hatred, loneliness, or stimulation as motivators for cutting. Research suggests that the prevalence (Robinson and Duffy 1989; Smith et al. 1998), form, and severity of self-harming behavior, including cutting, may be different for males and females (Laye-Gindhu and Schonert-Reichl 2005; Tyler et al. 2003). Our findings suggest that gendered differences may exist for motivations for the behavior as well.

Past suicide attempts and suicidality among peer networks were also significant predictors of particular motivations for cutting. Youth who had attempted suicide in the past year were twice as likely as non-attempters to report cutting in order to feel something. This finding contradicts Nock and Prinstein’s (2005) study involving adolescent psychiatric inpatients, wherein recent suicide attempts were significantly associated with automatic negative reinforcement (e.g., to stop bad feelings), but not automatic positive reinforcement (e.g., to feel something).

Additionally, our findings suggest that, among youth who cut, youth who had more friends who had attempted suicide in the past year were less likely to report loneliness as a motivation for cutting. Research on suicide indicates that there is an aspect of social contagion; those who know people who have attempted or completed suicide appear to be more likely to attempt suicide themselves (Gould 2001; Joiner 2003). Though social contagion has not been thoroughly studied in regards to NSSI (Deliberto and Nock 2008), Heath et al. (2009) found that having friends who self-harm increases youths’ chances of engaging in NSSI and this behavior is socially reinforced among peer networks. Similarly, Walker et al. (2001) suggest that self-harm behavior may serve to increase social support within a person’s social networks. Therefore, cutters whose friends have attempted suicide may be part of a social network where self-harm is considered normative and perhaps a source of social connection, decreasing their odds of endorsing loneliness as a reason for cutting. Further research into potential social contagion effects of NSSI seems warranted.

Endorsement of persistent sadness and hopelessness significantly predicted several motivations for cutting. Youth who reported experiencing these internalizing behaviors were over six times more likely to report self-hatred and five times more likely to report loneliness as motivations for cutting as compared to non-depressed youth. The finding that depression is related to self-hatred resonates with literature on internalized oppression among sexual minorities. The internalization of anti-LGBT attitudes and beliefs is associated with depression and a range of other mental health issues among sexual minorities (DiPlacido 1998; Meyer 2003). Additionally, self-injury among sexual minorities has been associated with self-hatred and self-punishment related to discomfort with their sexual orientation or gender identity (Alexander and Clare 2004; Scourfield et al. 2008). Feelings of loneliness and isolation are common correlates of depression (Bucy 1994; Keyes and Goodman 2006; Laser and Nicotera 2011; Margolin 2001) and, as such, it is not surprising that youth who experienced persistent sadness and hopelessness were more likely to endorse loneliness as a motivation for cutting than their counterparts.

Feeling sad or hopeless was also a marginally significant predictor of cutting to achieve stimulation, with depressed youth three times more likely to report needing stimulation as motivation for cutting as compared to non-depressed youth. Considering that depression is typically characterized by loss of motivation (or enjoyment in) to engage in daily routine or even enjoyable activities, it is reasonable that cutting among youth who experience persistent sadness and hopelessness may be associated with a desire to stimulate feeling or sensation.

Knowing a safe adult at school significantly reduced the odds of endorsing loneliness as a motivation for cutting. Youth who could identity a safe adult were half as likely to endorse loneliness as a motivation for cutting as compared to those who did not know a safe adult at school. This finding suggests that sexual minority youth who have an adult ally may feel less isolated, thus decreasing feelings of loneliness. This supports earlier findings about the protective function of supportive adults in the lives of sexual minority youth (Seelman et al. 2011; Walls et al. 2010b).

The degree to which youth were open about their sexual orientation and/or gender identity was a marginally significant predictor of cutting due to loneliness. Youth who were more open were more likely to report loneliness as a motivation for cutting. Sexual minority youth who are more open about their identity may be more vulnerable to social isolation, thus negatively impacting their mental health. This may be particularly true for sexual minority youth who are developing their identities within particularly hostile or invalidating social contexts.

Age was a marginally significant predictor of cutting in order to feel something, with younger participants being more likely than their older peers to endorse this motivation. Additionally, youth who had been harassed at/near school based on their actual or perceived sexual orientation were more likely than those who had not been harassed to cut in order to feel something (though this relationship was only marginally significant). Considering that sexual minority youth may shut down emotionally in response to experiencing harassment or fear of being harassed at school, this finding seems logical. Therefore, the function of cutting among these youth may be to stimulate feeling or avoid the emotional numbness that can result from coping with harassment.

It is noteworthy that experiencing harassment based on sexual orientation and/or gender identity was only a marginally significant predictor of one motivation for cutting: cutting in order to feel something. This result is surprising, given that numerous studies have identified a relationship between harassment, mental health, and coping among sexual minority youth (D’Augelli 2002; D’Augelli et al. 2002; Elze 2002). It is possible that harassment was not a strong predictor in this study due to the focus on motivations for cutting, rather than risk for cutting. Previous research indicates that harassment increases risk for cutting among sexual minority youth (e.g., Walls et al. 2010b), yet the current study indicates that, among youth who cut, harassment does not significantly predict endorsement of various motivations for doing so. A similar logic may explain why knowing a safe adult was only a significant predictor in one model (cutting due to loneliness), despite the known protective functions of this construct. While knowing a safe or supportive adult may reduce the risk of cutting and other risk behaviors among LGBT youth (Eisenberg and Resnick 2006; Murdock and Bolch 2005; Walls et al. 2010b), the current findings indicate that it may not play a large role in predicting various motivations for cutting.

Limitations

The results must be carefully considered within the context of the limitations of this study and its methodology. First, this study involved a convenience sample of sexual minority youth, which limits the generalizability of the results. The majority of the youth in this study described themselves as very open or somewhat open about their sexual orientation or gender identity and had received services at a sexual minority youth program. As such, the findings may not characterize the experiences of youth who are less open about their identities or who cannot or do not access LGBT-specific social service organizations. Additionally, the study participants were predominantly White and cisgender (non-transgender), which limits the generalizability of the findings to sexual minority youth of color and transgender, gender variant and genderqueer youth. Due to small cell sizes, we also lacked sufficient power to examine race/ethnicity as a predictor of motivations for cutting behavior or other within-group racial/ethnic differences among youth in the sample. Because the study relies on secondary data analysis, we had to rely on measures that may not have fully captured the complexity of some of the more multidimensional concepts, a limitation that is inherent in most studies that utilize existing data. Reliance on retrospective self-reports is a further limitation of this study and may compromise the reliability of the responses provided by participants. Given the proportion of endorsement/non-endorsement of some of the various motivations for engaging in cutting behavior combined with the number of independent variables we examine, our findings would be strengthened if our sample size of sexual minority youth who engage in cutting were larger. Thus our findings, as we suggest above, are exploratory in nature into an area of research where little has been conducted. In lieu of these various limitations, further research is clearly warranted to examine the robustness of our findings.

Implications for Practice

Overall, the prevalence and frequency of cutting among youth in this sample emphasizes the importance of routine screening for cutting and other forms of NSSI among sexual minority youth. Furthermore, this study supports previous findings that cutting is associated with, but distinct from, suicidal behavior (Glenn and Klonsky 2009; Stanley et al. 1992). The majority (61%) of cutters in this sample reported they had not attempted suicide in the past year. This distinction is critical for helping professionals who are mandated to report imminent threats to self and others. Although some youth who cut have a history of suicide attempts, cutting is not necessarily an indication that a youth is considering or attempting suicide. In fact, research indicates that engaging in NSSI may serve a protective function in helping people cope and thus preventing suicide attempts (Connors 2000; Klonsky 2007). Social workers are encouraged to seek out training and consultation specific to cutting and other forms of NSSI and to ensure that policies and interventions reflect the distinction between NSSI and suicidal behavior. The practitioner will need to be thoughtful about the relationship between the behavior and the motivation for the behavior.

The findings also suggest that interventions aimed at reducing cutting behavior among sexual minority youth may need to target the specific motivation(s) for cutting. For example, a youth who reports cutting due to self-hatred may benefit from interventions that focus on enhancing positive sexual orientation/gender identity development and countering internalized homo/transphobia. Since nearly three out of four youth in this study reported more than one motivation for cutting, practitioners should be prepared to conduct assessment and intervention strategies that identify and address multiple motivations.

The logistic regression analysis conducted in this study provides some evidence that sexual minority youth who have particular experiences, emotional states, or identities may be more likely to cut for particular motivations. Careful assessment of youth’s social identities, peer network, level of emotional distress, history of suicidal attempts, level of outness, and access to support may assist social workers in identifying youth who cut or who are at-risk of cutting and preventing the onset of cutting behaviors among sexual minority youth. Because of the stigma associated with cutting and other NSSI behavior, building rapport and trust with sexual minority youth is critical to create a relationship where the youth feel comfortable disclosing such behavior.

This study also underscores the protective function of support from adult allies with whom sexual minority youth can talk about their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Social workers can play a significant role in providing this support to youth as well as engaging in education and advocacy efforts with schools, families, religious institutions, neighborhood organizations, and other institutions to create more inclusive and welcoming environments for sexual minority youth. Sexual minority youth need culturally competent social workers who can support them in navigating the challenges of adolescence and who will act as allies in challenging oppressive behaviors and systems.

Finally, these results demonstrate the need for social workers to understand NSSI among sexual minority youth within a context of homophobia and transphobia. It is essential that helping professionals reject an approach that blames youth for the negative consequences of living in a social environment that invalidates, pathologizes, and victimizes sexual minorities. Instead, social workers should engage with youth and their communities to name and challenge the root causes of many of the psychosocial difficulties that these youth face.

Notes

Analyses indicated that there were no statistically significant differences between females, transgender youth, and gender variant/genderqueer youth on the variables of interest.

There were no significant differences between youth of color (as a group) and White youth in any of the models. However, when comparing various racial groups separately to Whites, bi/multi-racial youth were 5 times less likely than White youth to cut for emotional release (OR = .20, p < .01). Given the likelihood that this result is not robust due to the small number of participants who self-identified as bi/multi-racial, race/ethnicity variables were not included in the final analysis.

References

Alexander, N., & Clare, L. (2004). You still feel different: The experience and meaning of women’s self-injury in the context of a lesbian or bisexual identity. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 14(2), 70–84. doi:10.1002/casp.764.

Almeida, J., Johnson, R. M., Corliss, H. L., Molnar, B. E., & Azrael, D. (2009). Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(7), 1001–1014. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9.

Andover, M. S., Pepper, C. M., Ryabchenko, K. A., Orrico, E. G., & Gibb, B. E. (2005). Self-mutilation and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and borderline personality disorder. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 35, 581–591.

Armey, M. F., & Crowther, J. H. (2008). A comparison of linear versus non-linear models of aversive self-awareness, dissociation, and non-suicidal self-injury among young adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 9–14.

Babiker, G., & Arnold, L. (1997). The language of injury: Comprehending self-mutilation. Leicester, UK: The British Psychological Society.

Brausch, A. M., & Gutierrez, P. M. (2009). Differences in non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(3), 233–242. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9482-0.

Briere, J., & Gil, E. (1998). Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: Prevalence, correlates, and functions. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68, 609–620.

Brown, M. B., Comtois, K. A., & Linehan, M. M. (2002). Reasons for suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury in women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 111, 198–202.

Bucy, J. E. (1994). Internalizing affective disorders. In R. J. Simeonsson (Ed.), Risk, resilience & prevention: Promoting the well-being of all children (pp. 219–238). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

Bybee, J. A., Sullivan, E. L., Zielonka, E., & Moes, E. (2009). Are gay men in worse mental health than heterosexual men? The role of age, shame and guilt, and coming-out. Journal of Adult Development, 16, 144–154. doi:10.1007/s10804-009-9059-x.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011). 2004 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/yrbss.

Chapman, A. L., Gratz, K. L., & Brown, M. Z. (2006). Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: The experiential avoidance model. Behavior Research and Therapy, 44, 371–394.

Comtois, K. A. (2002). A review of interventions to reduce the prevalence of parasuicide. Psychiatric Services, 53(9), 1138–1144. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.9.1138.

Connors, R. E. (2000). Self-injury: Psychotherapy with people who engage in self-inflicted violence. Northvale, NJ: Aronson.

Crowe, M. (1997). Deliberate self-harm. In D. Bhugra & A. Monro (Eds.), Troublesome disguises: Underdiagnosing psychiatric symptoms (pp. 206–225). London: Routledge.

D’Augelli, A. R. (2002). Mental health problems among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths ages 14 to 21. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 7(3), 433–456.

D’Augelli, A. R., Pilkington, N. W., & Hershberger, S. L. (2002). Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly, 17(2), 148–167. doi:10.1521/scpq.17.2.148.20854.

Deliberto, T., & Nock, M. (2008). An exploratory study of correlates, onset, and offset of non-suicidal self-injury. Archives of Suicide Research, 12(3), 219–231. doi:10.1080/13811110802101096.

DiPlacido, J. (1998). Minority stress among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: A consequence of heterosexism, homophobia, and stigmatization. In G. M. Herek (Ed.), Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals (pp. 138–159). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Eisenberg, M. E., & Resnick, M. D. (2006). Suicidality among gay, lesbian and bisexual youth: The role of protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 662–668.

Elze, D. E. (2002). Risk factors for internalizing and externalizing problems among gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents. Social Work Research, 26(2), 89–99.

Favazza, A. R. (1996). Bodies under siege: Self-mutilation and body modification in culture and psychiatry (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Favazza, A. R., & Conterio, K. (1988). The plight of chronic self-mutilators. Community Mental Health Journal, 24, 22–30.

Favazza, A. R., DeRosear, L., & Conterio, K. (1989). Self-mutilation and eating disorders. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 19, 352–361.

Figueroa, M. D. (1988). A dynamic taxonomy of self-destructive behavior. Psychotherapy: Theory/Research/Practice/Training, 25, 280–287.

Garrison, C. Z., McKeown, R. E., Valois, R. F., & Vincent, M. L. (1993). Aggression, substance use, and suicidal behaviors in high school students. American Journal of Public Health, 83, 179–184.

Glenn, C., & Klonsky, E. (2009). Social context during non-suicidal self-injury indicates suicide risk. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(1), 25–29. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.08.020.

Gould, M. S. (2001). Suicide and the media. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 932, 200–221.

Gratz, K. L., Conrad, S. D., & Roemer, L. (2002). Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 72, 128–140.

Heath, N. L., Ross, S., Toste, J. R., Charlebois, A., & Nedecheva, T. (2009). Retrospective analysis of social factors and nonsuicidal self-injury among young adults. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement, 41(3), 180–186. doi:10.1037/a0015732.

Himber, J. (1994). Blood rituals: Self-cutting in female psychiatric patients. Psychotherapy, 31, 620–631.

Joiner, T. (2003). Contagion of suicidal symptoms as a function of assortative relating and shared relationship stress in college roommates. Journal of Adolescence, 26, 495–504. doi:10.1016/S0140-1971(02)00133-1.

Keyes, C., & Goodman, S. (2006). Women and depression. New York: Cambridge.

Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinical Psychology Review, 27, 226–239.

Klonsky, E. D., & Olino, T. M. (2008). Identifying clinically distinct subgroups of self-injurers among young adults: A latent class analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 22–27.

Klonsky, E. D., Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2003). Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1501–1508.

Laser, J., & Nicotera, N. (2011). Working with adolescents: A practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford.

Laye-Gindhu, A., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2005). Nonsuicidal self-harm among community adolescents: Understanding the ‘whats’ and ‘whys’ of self-harm. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(5), 447–457. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-7262-z.

Levenkron, S. (1998). Cutting: Understanding and overcoming self mutilation. New York: Norton.

Linehan, M. M. (1993). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford.

Margolin, S. (2001). Do social support and activity involvement reduce isolated youths’ internalized difficulties? Doctoral dissertation. Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses database.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

Murdock, T. B., & Bolch, M. B. (2005). Risk and protective factors for poor school adjustment in lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) high school youth. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 159–172.

Nock, M. K., & Mendes, W. B. (2008). Physiological arousal, distress tolerance, and social problem-solving deficits among adolescent self-injurers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 28–38.

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(5), 885–890. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885.

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2005). Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 140–146. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.140.

Pilkington, N. W., & D’Augelli, A. R. (1995). Victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth in community settings. Journal of Community Psychology, 23(1), 34–56. doi:10.1002/1520-6629(199501)23:1<34:AID-JCOP2290230105>3.0.CO;2-N.

Prinstein, M. J. (2008). Introduction to the special section on suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury: A review of unique challenges and important directions for self-injury science. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(1), 1–8. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.1.

Rivers, I. (2000). Social exclusion, absenteeism, and sexual minority youth. Support for Learning, 15, 13.

Robinson, A., & Duffy, J. (1989). A comparison of self-injury and self-poisoning from the Regional Poisoning Treatment Centre, Edinburgh. Acta Psychiatr Scand, 80, 272–279.

Ross, S., & Heath, N. (2002). A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 67–77.

Scourfield, J., Roen, K., & McDermott, L. (2008). Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender young people’s experiences of distress: Resilience, ambivalence and self-destructive behaviour. Health & Social Care in the Community, 16(3), 329–336.

Seelman, K. L., Walls, N. E., Hazel, C., & Wisneski, H. (2011). Student school engagement among sexual minority students: Understanding the contributors to predicting academic outcomes. Journal of Social Service Research. doi:10.1080/01488376.2011.583829.

Simeon, D., & Favazza, A. R. (2001). Self-injurious behaviors: Phenomenology and assessment. In D. Simeon & E. Hollander (Eds.), Self-injurious behaviors: Assessment and treatment (pp. 1–28). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Skegg, K., Nada-Raja, S., Dickson, N., Paul, C., & Williams, S. (2003). Sexual orientation and self-harm in men and women. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(3), 541.

Smith, G., Cox, D., & Saradjian, J. (1998). Women and self-harm: Understanding, coping, and healing from self-mutilation. London: The Women’s Press.

Stanley, B., Winchel, R., Molcho, A., Simeon, D., & Stanley, M. (1992). Suicide and the self-harm continuum: Phenomenological and biochemical evidence. International Review of Psychiatry, 4, 149–155.

Tantam, D., & Whittaker, J. (1992). Personality disorder and self-wounding. British Journal of Psychiatry, 161, 451–464.

Tyler, K. A., Whitbeck, L. B., Hoyt, D. R., & Johnson, K. D. (2003). Self-mutilation and homeless youth: The role of family abuse, street experiences, and mental disorders. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 13(4), 457–474. doi:10.1046/j.1532-7795.2003.01304003.x.

van Buuren, S., Boshuizen, H. C., & Knook, D. L. (1999). Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 18, 681–694.

Walker, R. L., Joiner, T. E., Jr., & Rudd, M. D. (2001). The course of post-crisis suicidal symptoms: How and for whom is suicide “cathartic”? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 31, 144–152. doi:10.1521/suli.31.2.144.21514.

Walls, N. E., Freedenthal, S., & Wisneski, H. (2008). Suicidal ideation and attempts among sexual minority youth receiving social services. Social Work, 53, 21–29.

Walls, N. E., Hancock, P., & Wisneski, H. (2007). Differentiating the social service needs of homeless sexual minority youth from those of non-homeless sexual minority youth. Journal of Children & Poverty, 13, 177–205.

Walls, N. E., Kane, S. B., & Wisneski, H. (2010a). Gay-straight alliances and school experiences of sexual minority youth. Youth & Society, 41, 307–332.

Walls, N. E., Laser, J., Nickels, S., & Wisneski, H. (2010b). Correlates of cutting behavior among sexual minority youth. Social Work Research, 34, 213–226.

Weierich, M. R., & Nock, M. K. (2008). Posttraumatic stress symptoms mediate the relation between childhood sexual abuse and nonsuicidal self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 39–44.

Whitlock, J. (2010). Self-injurious behavior in adolescents. PLoS Medicine, 7(5), 1–4. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000240.

Whitlock, J., Eckenrode, J., & Silverman, D. (2006). Self-injurious behaviors in a college population. Pediatrics, 117, 1939–1948.

Whitlock, J., & Knox, K. L. (2007). The relationship between self-injurious behavior and suicide in a young adult population. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 161, 634–640.

Wichstrøm, L. (2009). Predictors of non-suicidal self-injury versus attempted suicide: Similar or different? Archives of Suicide Research, 13(2), 105–122. doi:10.1080/13811110902834992.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nickels, S.J., Walls, N.E., Laser, J.A. et al. Differences in Motivations of Cutting Behavior Among Sexual Minority Youth. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 29, 41–59 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-011-0245-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-011-0245-x