Abstract

Purpose

This study aims to look at the distribution of different subtypes of stage I–III breast cancer in Māori and Pacific versus non-Māori/Pacific women, and to examine cancer outcomes by ethnicity within these different subtypes.

Method

This study included 9,015 women diagnosed with stage I–III breast cancer between June 2000 and May 2013, recorded in the combined Waikato and Auckland Breast Cancer Registers, who had complete data on ER, PR and HER2 status. Five ER/PR/HER2 subtypes were defined. Kaplan–Meier method and Cox proportional hazards model were used to examine ethnic disparities in breast cancer-specific survival.

Results

Of the 9,015 women, 891 were Māori, 548 were Pacific and 7,576 others. Both Māori and Pacific women were less likely to have triple negative breast cancer compared to others (8.6, 8.9 vs. 13.0%). Pacific women were more than twice as likely to have ER−, PR− and HER2+ cancer than Māori and others (14.2 vs. 6.0%, 6.7%). After adjustment for age, year of diagnosis, stage, grade and treatment, the hazard ratios of breast cancer-specific mortality for Māori and Pacific women with ER+, PR+ and HER2− were 1.52 (95% CI 1.06–2.18) and 1.55 (95% CI 1.04–2.31) compared to others, respectively. Māori women with HER2+ cancer were twice more likely to die of their cancer than others.

Conclusions

Outcomes for Māori and Pacific women could be improved by better treatment regimens especially for those with HER2+ breast cancer and for women with ER+, PR+ and HER2− breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Biomarkers, including oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), are important prognostic and predictive indicators for breast cancer. In New Zealand, ER and PR status have been routinely measured for the last 25 years. The measurement of HER2 status became increasingly common from the first part of this century and has been routine since 2006. Women with breast cancers that are both ER and PR positive (+) have a better prognosis than those with ER and PR negative (−) disease, while women with HER2+ cancers have a worse prognosis than those with HER2− disease [1]. A US study showed that women with ER+, PR+ and HER2− breast cancer were half as likely to die of breast cancer as those with ER−, PR− and HER2+ cancers [2]. This large study also demonstrated that women with triple negative (ER−, PR− and HER2−) breast cancer had the worst prognosis after adjustment for cancer stage [2]. This is consistent with the results in other studies [3,4,5].

Patients can receive personalised treatments based on the results of these biomarkers [6,7,8]. Women with hormone receptor-positive (ER+ and/or PR+) breast cancers are recommended to receive endocrine therapy and women with HER2+ breast cancer may benefit from chemotherapy and trastuzumab [9,10,11,12]. Trastuzumab was first funded in New Zealand for use in early stage HER2+ breast cancer in July 2007 [10].

There are great variations in the prevalence of breast cancer subtypes by ethnicity [12]. African American, Hispanic Whites, and Asian/Pacific Islanders were shown to be more likely to have HER2+ breast cancer than Non-Hispanic Whites in the US [12, 13]. African Americans were twice as likely to have triple negative breast cancer as Non-Hispanic Whites [12]. Within the same breast cancer subtype, there are ethnic disparities in survival. Asian/Pacific Islanders had a better breast cancer-specific survival in most subtypes than non-Hispanic Whites, except in the ER+, PR− and HER2+ subtype [13].

New Zealand has a population of 4.7 million, with 15% Māori and 7% Pacific people [14]. Māori is the indigenous population in New Zealand [15], while Pacific people [16] are a heterogeneous group with a long history of migration to NZ from an array of island nations, including but not limited to Fiji, Samoa, Tonga and Cook islands. In a previous study, Māori and Pacific women were shown to be more likely to be diagnosed with HER2+ breast cancer than others (22%, 27 vs. 16%, p value < 0.05) [17]. Māori women were significantly more likely to have hormone receptor-positive cancers than others, but Pacific women were less likely [17]. There have been limited studies investigating the ethnic differences in subtypes in New Zealand [18, 19]. It is well recognised that there are differences in the treatment of Māori and Pacific women with breast cancer and that they have poorer survival [17,18,19,20,21,22]. This study aims to look at the distribution of different subtypes of stage I-III breast cancer in Māori and Pacific versus non-Māori/Pacific, and to examine the treatment and outcomes by ethnicity within different subtypes.

Methods

Data sources

This study included 9,015 women diagnosed with stage I-III breast cancer between June 2000 and May 2013, recorded in the combined Waikato and Auckland Breast Cancer Registers, who had complete data on their ER, PR and HER2 status [23]. 2,783 stage I–III breast cancer cases with incomplete information on ER, PR, and HER2 were excluded. The registers’ data includes patient characteristics (age and ethnicity), tumour information (diagnosis date, cancer stage and grade) and information on treatment (surgery, endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, trastuzumab and radiation therapy). Information on comorbidities was obtained by reviewing linked data from the National Minimum dataset (NMDS) and characterising patients as having no comorbidities (C0), one comorbidity (C1) or 2 or more (C2+) using the C3 comorbidity index [24, 25].

The three biomarkers ER, PR and HER2 were designated as being either positive or negative. In this study, HER2+ was defined as FISH amplified or IHC 3+. There are eight possible groups defined by ER, PR and HER2 status. There is a small group (1%, 112) of women with breast cancer that is ER− but PR+. These women are usually treated with hormone therapy that is the same as women with ER+, PR+ cancer. We categorised women into five groups based on the clinical advice and practice in our region. The grouping is similar to published literature [26,27,28,29,30].

-

Group 1(ER+, PR+, and HER2−): 5,331 women

-

Group 2 (Mixed ER/PR, HER2−):

ER+, PR−, and HER2−: 1,037 women

ER−, PR+, and HER2−: 88 women

-

Group 3 (HER2+ not overexpressing):

ER+, PR+, and HER2+: 573 women

ER+, PR−, and HER2+: 261 women

ER−, PR+, and HER2+: 24 women

-

Group 4 (HER2+ overexpressing):

ER−, PR−, and HER2+: 589 women

-

Group 5 (Triple negative):

ER−, PR−, and HER2−: 1,112 women

Statistical analyses

Cancer characteristics and treatments by ethnicity within the five subtypes were explored, and differences were examined by Chi-Square tests. Logistic regression models were used to estimate the odds ratios of receiving endocrine therapy, chemotherapy and trastuzumab by ethnicity within the five subtypes after adjustment for age, year of diagnosis, cancer stage, grade and C3 score [24, 25].

Mortality data for this study was derived from the National Mortality Collection and linked via the National Health Index (NHI) number to the register data. The NHI number is a unique identifier for people who use health and disability services in New Zealand. For cancer-specific survival analyses, patients who died from other causes were censored on their date of death, and patients without mortality information were considered to be censored on the last updated date for Mortality Collection which was 31 December 2014. The Kaplan Meier method was used to examine ethnic disparities in breast cancer-specific survival within the five subtypes. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the hazard ratio of dying of breast cancer for Māori and Pacific women compared to others in the five subtypes after adjustment for age, year of diagnosis, stage, grade and treatments. All data analyses were performed in IBM SPSS statistics 23 (New York, United States).

Ethical approval for the study was granted through the Northern A Health and Disability Ethics Committee (reference: 12/NTA/42/AM01).

Results

Of the 9,015 women, 891 were Māori, 548 were Pacific, and 7576 were others including European and Asian (Table 1). Both Māori and Pacific women were less likely to have triple negative breast cancer compared to others (8.6% and 8.9 vs. 13.0%). Pacific women were more than twice as likely to have HER2+ overexpressing (Group 4) cancer than Māori and other women (14.2 vs. 6.7% and 6.0%), but were less than half as likely to have mixed ER/PR, HER2 (Group 2) breast cancer than Māori and others (5.5 vs. 11.2% and 13.1%). Māori and Pacific women were more likely to have stage III breast cancer than others in the five subtypes, except for Māori women with mixed ER/PR, HER2− cancer (Group 2). Among women with ER+, PR+ and HER2− breast cancer, Pacific women were significantly more likely to have grade 3 disease than others (21.5 vs. 12.4%). However, only 67.4% of Pacific women with triple negative breast cancer (Group 5) had grade 3 cancer compared to 80.6% of others.

For women with ER+, PR+ and HER2− (Group 1) breast cancer, Māori and Pacific women received more endocrine therapy and chemotherapy (Table 2). After adjustment for age, year of diagnosis, cancer stage, grade and C3 score (Table 3), there was no difference in treatment between Māori and others, but Pacific women were less likely to receive chemotherapy (odds ratio 0.51, 95% CI 0.35–0.75) than others. Among women with triple negative or HER2+ disease, Pacific women were again less likely to be treated with chemotherapy (Table 3). After adjustment for other factors (age, year of diagnosis, cancer stage, grade and C3 score), Māori women with HER2+ breast cancer were half as likely to receive trastuzumab than others, and Pacific women with HER2+ breast cancer were only 20% as likely to receive chemotherapy and trastuzumab than others.

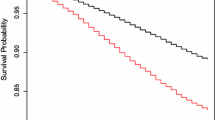

Kaplan–Meier method showed small but significant differences in breast cancer-specific survival for women with ER+, PR+, and HER2− cancer (Group 1) and women with HER2+ overexpressing cancer (Group 4) by ethnic group (Fig. 1). The respective 5-year breast cancer-specific survival for Māori, Pacific and others with ER+, PR+, and HER2− cancer was 94.2, 93.1 and 96.5% (p value for Log-rank test < 0.001). In women with HER2+ overexpressing breast cancer (Group 4), the 5-year breast cancer-specific survival (Fig. 2) was worst for Māori (57.8%), followed by Pacific (66.4%) compared with others (78.5%) (p value < 0.001). No significant ethnic differences in breast cancer-specific survival were found in women with mixed ER/PR, HER2− (Group 2), HER2+ not overexpressing (Group 3) or triple negative cancer (Group 5).

After adjustment for age, year of diagnosis, stage, grade and treatment (specified in Table 4), hazard ratios of breast cancer-specific mortality for Māori and Pacific women with ER+, PR+ and HER2− cancer (Group 1) were 1.52 (95% CI 1.06–2.18) and 1.55 (95% CI 1.04–2.31) compared to others. Survival differences between Pacific women and others with HER2+ breast cancer were not significant after adjustment for other factors. However, Māori women with HER2+ breast cancer (Group 3 and 4) were twice more likely to die of their cancer than others.

Discussion

Breast cancer survival inequities between ethnic groups of women in New Zealand are large and of great concern. There is an increasing understanding that cancer survival inequities result from multiple, often small, but cumulative inequities which occur along the cancer treatment pathway [31]. Previous New Zealand studies have looked at the impact of commonly measured biomarkers (ER/PR and HER2) individually instead of different biomarker combinations [18, 19, 32]. This study has highlighted the differences in recognised biomarker combinations in Māori and Pacific women.

Pacific women were less likely to be diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer (Group 5) but were more likely to be diagnosed with HER2+ overexpressing cancer (Group 4) compared to others (8.9 vs. 13.0%, and 14.2 vs. 6.0%). A US study demonstrated consistent results but with a smaller difference: 10.6% of Pacific Islanders and 11.3% of Whites having triple negative breast cancer, 10.6% of Pacific Islanders and 5.6% of Whites having ER−, PR− and HER2+ breast cancer [33]. Māori were as likely to have triple negative breast cancer as Pacific women, and were as likely to have ER−, PR− and HER2+ breast cancer as others.

Differences in subtype distribution by ethnic group may be related to the genetic factors, environment, diet, obesity and hormone exposure including oral contraceptive use and hormone replacement therapy [34,35,36,37,38]. Triple negative subtype breast cancer is associated with specific DNA methylation profile [37], which may explain the ethnic difference in having triple negative subtype breast cancer. Another reason may be the difference in number of pregnancies a woman has had. Māori and Pacific women in New Zealand tend to have more pregnancies than others [39]. A Norway study indicated that increasing parity was inversely associated with triple negative cancer (Group 5), though the result was not significant (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.41–1.21) [34]. The risk of having HER2+ overexpressing cancer (Group 4) was found to increase with increasing waist size before menopause, and increased in association with metabolic syndrome in postmenopausal women [35]. The 2015/16 New Zealand Health Survey shown that 47% of Māori adults and 67% of Pacific adults were obese,[40] which may have contributed to the higher risk of having HER2+ overexpressing cancer (Group 4).

Our previous study showed that the probability of receiving trastuzumab decreased with age and comorbidities score, and increased with cancer stage and grade [41]. In this analysis, we found the discrepancy by ethnicity after adjustment for these variables (Table 3). It is worrying that the adjusted HR for Māori women with HER2+ disease is double that of others. The disparity in the use of an effective and expensive treatment in Māori women with HER2+ disease linked to evidence of substantially poor outcomes is of concern and requires further research.

In women with ER+, PR+ and HER2− (Group 1) breast cancer, Māori and Pacific women had worse breast cancer-specific survival than others, although in the three ethnic groups overall breast cancer-specific survival is very good. Women with ER+, PR+ and HER2− breast cancer are mainly treated with endocrine therapy. While in this study Māori and Pacific women with ER+ breast cancer are just as likely to receive endocrine therapy, in a previous study we noted poorer adherence to endocrine therapy in Māori women compared to others, and this was shown to be associated with worse breast cancer outcome [9].

The strengths of this study include that this study is based on the Waikato and Auckland population-based Breast Cancer Registers that collect good quality data on all breast cancer patients [23]. We have comprehensive data on patient characteristics, patient treatment as well as outcomes. One weakness is that in earlier years not all women had their biomarkers tested, especially HER2 status. Consequently, there may be differences in the distribution of subtypes (e.g. by age and stage) in earlier years in this study. Also there may be some differences in treatment over time with increasing use of trastuzumab and changes of the regimens of chemotherapy. However, in the Cox proportional hazard models we have adjusted age, year of diagnosis, stage, grade and treatment.

Conclusion

This study does give us some indications that outcomes for Māori and Pacific women could be improved by better uptake of treatment, especially for those with HER2+ breast cancer. There are also differences in outcomes for Māori and Pacific women with ER+, PR+ and HER2− cancer. When treatment is increasingly targeted to patient characteristics including hormonal status, it is important to ensure treatment is equally delivered to high need Māori and Pacific women.

References

Seneviratne SA, Campbell ID, Scott N, Lawrenson RA, Shirley R, Elwood JM (2015) Risk factors associated with mortality from breast cancer in Waikato, New Zealand: a case-control study. Public Health 129(5):549–554. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2015.02.008

Parise CA, Caggiano V (2014) Breast cancer survival defined by the er/pr/her2 subtypes and a surrogate classification according to tumor grade and immunohistochemical biomarkers. J Cancer Epidemiol. doi:10.1155/2014/469251

Li X, Yang J, Peng L, Sahin AA, Huo L, Ward KC, O’Regan R, Torres MA, Meisel JL (2017) Triple-negative breast cancer has worse overall survival and cause-specific survival than non-triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 161(2):279–287. doi:10.1007/s10549-016-4059-6

Haffty BG, Yang Q, Reiss M, Kearney T, Higgins SA, Weidhaas J, Harris L, Hait W, Toppmeyer D (2006) Locoregional relapse and distant metastasis in conservatively managed triple negative early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 24(36):5652–5657. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5664

Onitilo AA, Engel JM, Greenlee RT, Mukesh BN (2009) Breast cancer subtypes based on ER/PR and Her2 expression: comparison of clinicopathologic features and survival. Clin Med Res 7(1–2):4–13. doi:10.3121/cmr.2009.825

Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart M, Thürlimann B, Senn HJ, Albain KS, André F, Bergh J, Bonnefoi H, Bretel-Morales D, Burstein H, Cardoso F, Castiglione-Gertsch M, Coates AS, Colleoni M, Costa A, Curigliano G, Davidson NE, Leo AD, Ejlertsen B, Forbes JF, Gelber RD, Gnant M, Goldhirsch A, Goodwin P, Goss PE, Harris JR, Hayes DF, Hudis CA, Ingle JN, Jassem J, Jiang Z, Karlsson P, Loibl S, Morrow M, Namer M, Osborne CK, Partridge AH, Penault-Llorca F, Perou CM, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Pritchard KI, Rutgers EJT, Sedlmayer F, Semiglazov V, Shao ZM, Smith I, Thürlimann B, Toi M, Tutt A, Untch M, Viale G, Watanabe T, Wilcken N, Winer EP, Wood WC (2013) Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the st gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast Cancer 2013. Ann Oncol 24(9):2206–2223. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdt303

Carey LA, Dees EC, Sawyer L, Gatti L, Moore DT, Collichio F, Ollila DW, Sartor CI, Graham ML, Perou CM (2007) The triple negative paradox: primary tumor chemosensitivity of breast cancer subtypes. Clin Cancer Res 13(8):2329–2334. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1109

Slamon D, Eiermann W, Robert N, Pienkowski T, Martin M, Press M (2011) Breast Cancer International Research Group. Adjuvant trastuzumab in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 365

Seneviratne S, Campbell I, Scott N, Kuper-Hommel M, Kim B, Pillai A, Lawrenson R (2015) Adherence to adjuvant endocrine therapy: is it a factor for ethnic differences in breast cancer outcomes in New Zealand? Breast 24(1):62–67. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2014.11.011

Metcalfe S, Evans J, Priest G (2007) PHARMAC funding of 9-week concurrent trastuzumab (Herceptin) for HER2-positive early breast cancer. N Z Med J 120:(1256)

New Zealand Herald (2008) National would fund year of Herceptin. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10524525

Chen L, Li CI (2015) Racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by hormone receptor and HER2 status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 24(11):1666–1672. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.epi-15-0293

Parise C, Caggiano V (2016) Breast cancer mortality among Asian-American women in California: variation according to ethnicity and tumor subtype. J Breast Cancer 19(2):112–121. doi:10.4048/jbc.2016.19.2.112

National Population Estimates: At 30 June 2016 (2016) http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/NationalPopulationEstimates_HOTPAt30Jun16.aspx

Ministry of Health (2015) Tatau Kahukura: Māori health statistics. http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/populations/maori-health/tatau-kahukura-maori-health-statistics/nga-mana-hauora-tutohu-health-status-indicators/cancer

Earle D (1995) Pacific Islands peoples in Aotearoa/New Zealand: existing and emerging paradigms. Wellington

Campbell I, Scott N, Seneviratne S, Kollias J, Walters D, Taylor C, Roder D (2015) Breast cancer characteristics and survival differences between Maori, Pacific and other New zealand women included in the quality audit program of breast surgeons of Australia and New Zealand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 16(6):2465–2472. doi:10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.6.2465

Davey V, Robinson B, Dijkstra B, Harris G (2012) The Christchurch Breast Cancer Patient Register: the first year. N Z Med J 125(1360):37–47

Seneviratne S, Lawrenson R, Scott N, Kim B, Shirley R, Campbell I (2015) Breast cancer biology and ethnic disparities in breast cancer mortality in New Zealand: a cohort study. PLoS ONE 10 (4). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123523

Lawrenson R, Seneviratne S, Scott N, Peni T, Brown C, Campbell I (2016) Breast cancer inequities between Maori and non-Maori women in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Eur J Cancer Care 25(2):225–230. doi:10.1111/ecc.12473

Seneviratne S, Campbell I, Scott N, Coles C, Lawrenson R (2015) Treatment delay for Māori women with breast cancer in New Zealand. Ethn Health 20(2):178–193. doi:10.1080/13557858.2014.895976

Seneviratne S, Scott N, Lawrenson R, Campbell I (2015) Ethnic, socio-demographic and socio-economic differences in surgical treatment of breast cancer in New Zealand. ANZ J Surg. doi:10.1111/ans.13011

Seneviratne S, Campbell I, Scott N, Shirley R, Peni T, Lawrenson R (2014) Accuracy and completeness of the New Zealand Cancer Registry for staging of invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol 38(5):638–644. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2014.06.008

Tin ST, Elwood JM, Lawrenson R, Campbell I, Harvey V, Seneviratne S (2016) Differences in breast cancer survival between public and private care in New Zealand: which factors contribute? PLoS ONE. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0153206

Sarfati D, Gurney J, Stanley J, Salmond C, Crampton P, Dennett E, Koea J, Pearce N (2014) Cancer-specific administrative data-based comorbidity indices provided valid alternative to Charlson and National Cancer Institute Indices. J Clin Epidemiol 67(5):586–595. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.11.012

Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Thürlimann B, Senn HJ (2011) Strategies for subtypes-dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2011. Ann Oncol 22(8):1736–1747. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr304

Arvold ND, Taghian AG, Niemierko A, Abi Raad RF, Sreedhara M, Nguyen PL, Bellon JR, Wong JS, Smith BL, Harris JR (2011) Age, breast cancer subtype approximation, and local recurrence after breast-conserving therapy. J Clin Oncol 29(29):3885–3891. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.36.1105

Von Minckwitz G, Untch M, Blohmer JU, Costa SD, Eidtmann H, Fasching PA, Gerber B, Eiermann W, Hilfrich J, Huober J, Jackisch C, Kaufmann M, Konecny GE, Denkert C, Nekljudova V, Mehta K, Loibl S (2012) Definition and impact of pathologic complete response on prognosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in various intrinsic breast cancer subtypes. J Clin Oncol 30(15):1796–1804. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.38.8595

Kwan ML, Kushi LH, Weltzien E, Maring B, Kutner SE, Fulton RS, Lee MM, Ambrosone CB, Caan BJ (2009) Epidemiology of breast cancer subtypes in two prospective cohort studies of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. doi:10.1186/bcr2261

Huober J, Von Minckwitz G, Denkert C, Tesch H, Weiss E, Zahm DM, Belau A, Khandan F, Hauschild M, Thomssen C, Högel B, Darb-Esfahani S, Mehta K, Loibl S (2010) Effect of neoadjuvant anthracycline-taxane-based chemotherapy in different biological breast cancer phenotypes: overall results from the GeparTrio study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 124(1):133–140. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1103-9

Seneviratne S, Campbell I, Scott N, Shirley R, Peni T, Lawrenson R (2015) Ethnic differences in breast cancer survival in New Zealand: contributions of differences in screening, treatment, tumor biology, demographics and comorbidities. Cancer Causes Control 26(12):1813–1824. doi:10.1007/s10552-015-0674-5

Seneviratne S, Lawrenson R, Harvey V, Ramsaroop R, Elwood M, Scott N, Sarfati D, Campbell I (2016) Stage of breast cancer at diagnosis in New Zealand: impacts of socio-demographic factors, breast cancer screening and biology. BMC Cancer 16 (1). doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2177-5

Parise C, Caggiano V (2014) Disparities in the risk of the ER/PR/HER2 breast cancer subtypes among Asian Americans in California. Cancer Epidemiol 38(5):556–562. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2014.08.001

Ellingjord-Dale M, Vos L, Tretli S, Hofvind S, dos-Santos-Silva I, Ursin G (2017) Parity, hormones and breast cancer subtypes—results from a large nested case-control study in a national screening program. Breast Cancer Res 19(1). doi:10.1186/s13058-016-0798-x

Agresti R, Meneghini E, Baili P, Minicozzi P, Turco A, Cavallo I, Funaro F, Amash H, Berrino F, Tagliabue E, Sant M (2016) Association of adiposity, dysmetabolisms, and inflammation with aggressive breast cancer subtypes: a cross-sectional study. Breast Cancer Res Treat 157(1):179–189. doi:10.1007/s10549-016-3802-3

Cerne JZ, Ferk P, Frkovic-Grazio S, Leskosek B, Gersak K (2012) Risk factors for HR- and HER2-defined breast cancer in Slovenian postmenopausal women. Climacteric 15(1):68–74. doi:10.3109/13697137.2011.609286

Holm K, Hegardt C, Staaf J, Vallon-Christersson J, Jönsson G, Olsson H, Borg Å, Ringnér M (2010) Molecular subtypes of breast cancer are associated with characteristic DNA methylation patterns. Breast Cancer Res. doi:10.1186/bcr2590

Phipps AI, Chlebowski RT, Prentice R, McTiernan A, Wactawski-Wende J, Kuller LH, Adams-Campbell LL, Lane D, Stefanick ML, Vitolins M, Kabat GC, Rohan TE, Li CI (2011) Reproductive history and oral contraceptive use in relation to risk of triple-negative breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 103(6):470–477. doi:10.1093/jnci/djr030

Statistics New Zealand (2011) Demographic Trends: 2011. http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/population/estimates_and_projections/demographic-trends-2011/births.aspx. Accessed 11 September 2017

Ministry of Health (2016) Annual update of key results 2015/16: New Zealand Health Survey. Ministry of Health, Wellington

Lawrenson R, Lao C, Campbell I, Harvey V, Brown C, Seneviratne S, Edwards M, Elwood M, Kuper-Hommel M (2017) The use of trastuzumab in New Zealand women with breast cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. doi:10.1111/ajco.12766

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the financial support from the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Auckland and Waikato Breast Cancer Registers for providing the detailed data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lawrenson, R., Lao, C., Campbell, I. et al. Treatment and survival disparities by ethnicity in New Zealand women with stage I–III breast cancer tumour subtypes. Cancer Causes Control 28, 1417–1427 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-017-0969-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-017-0969-9