Abstract

Multinational companies (MNCs) frequently adopt corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities that are aimed at providing ‘public goods’ and influencing the government in policymaking. Such political CSR (PCSR) activities have been determined to increase MNCs’ socio-political legitimacy and to be useful in building relationships with the state and other key external stakeholders. Although research on MNCs’ PCSR within the context of emerging economies is gaining momentum, only a limited number of studies have examined the firm-level variables that affect the extent to which MNCs’ subsidiaries in emerging economies pursue PCSR. Using insights from resource dependence theory, institutional theory, and the social capital literature, we argue that MNCs’ subsidiaries that are critically dependent on local resources, have greater ties to managers of related businesses and to policymakers, and that those that are interdependent on the MNCs’ headquarters and other foreign subsidiaries, are more likely to be involved in PCSR. We obtain support for our hypotheses using a sample of 105 subsidiaries of foreign firms that operate in India. Our findings enhance our understanding of the factors that determine MNCs’ political CSR in emerging economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In emerging economies, corporate social responsibility (CSR) primarily refers to the continuing commitment by organizations to behave ethically and to contribute to economic development. Multinational corporations (MNCs) are known to adopt CSR activities that increase their role in governance at a host country level and on a global scale (Detomasi 2007, 2008). By leveraging their CSR activities, MNCs are also known to engage in ‘self-regulation’ in host countries where existing governance mechanisms have failed or have been found to be inefficiently enforced (King and Lenox 2000; Maxwell et al. 2000). In this context, MNCs’ philanthropic donations and sponsoring activities within host countries are often used as a means of gaining access to political elites (Fooks et al. 2011), bridging governance gaps (Gond et al. 2011), and improving their local reputation and credibility (Rao 1994). Scholars have emphasized that such use of CSR for gaining political leverage can ultimately reduce the risk of unfavorable regulation (McDaniel and Malone 2012; Tesler and Malone 2008) and improve the overall business climate (Dorfman et al. 2012). Collectively, such CSR activities are often referred to as Political CSR (PCSR) activities because their underlying goal is to influence public policymaking processes and to become involved in rule making (Scherer and Palazzo 2007, 2011).

The need to integrate CSR activities into the public policy arena is greater for MNCs that operate within the context of emerging economies because, in these economies, MNCs’ subsidiaries are faced with a variety of stakeholder issues, such as changing governmental policies, societal attitudes, legal rulings, community actions, and media reports, which all have complex and unpredictable influences on their operations (Luo 2001; Peng and Luo 2000). Simultaneously, these economies are characterized by institutional frameworks that often do not enable MNCs to effectively communicate their CSR programs to external stakeholders (Rettab et al. 2009). Furthermore, legitimate mechanisms for business-government interaction are often absent, requiring firms to develop informal ties (Li et al. 2008b; Li et al. 2008a; Sheng et al. 2011) or to create and exploit family or other social relationships as a means of connecting with external stakeholders and influencing policymaking (Dieleman and Boddewyn 2012). However, the exploitation of ties and social relationships in emerging economies is increasingly being linked to corruption (Luo 2006). For instance, in India, the recent ‘2G scandal’ in the telecommunications sector indicated that the allocation of telecom spectrum licenses was made based on the assurances of firms that had built good relationships with the telecommunications minister. In this context, the Telenor Group, a major Norwegian telecom firm, suffered huge losses after the Supreme Court of India canceled the 22 licenses obtained by Telenor’s Indian partner, Unitech (Economist 2012). By contrast, in the consumer goods sector, the British firm Unilever’s Indian subsidiary Hindustan Lever Limited adopted the strategy of collaborating with non-traditional partners, such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), local suppliers, customers and distributors, and participating in the process of local economic development (London and Hart 2004). By strategically aligning its CSR strategy with the local government’s development initiatives, Unilever was able to generate more than $1 billion from the low-income markets in India alone (Ellison et al. 2002). Thus, we suggest that, while on one hand, the use of ties and relationships as a means of influencing policymaking in emerging economies has been found to be detrimental to MNCs’ financial performance in the long term (Li et al. 2008a); on the other hand, the use of PCSR activities has been found to increase their legitimacy and reputation and has also enabled MNCs to gain specific governmental subsidies and incentives vital for their operations, as evident in recent research (e.g., Zhao 2012).

Although studies have confirmed the implications of PCSR strategies for external relationship building and legitimacy gaining, we suggest that limited attention has been paid to the firm-level determinants of MNCs’ PCSR strategies. Studies on the determinants of PCSR in an international context have primarily focused on identifying the ‘institutional voids’ or governance gaps that lead MNCs to adopt such activities (Detomasi 2007, 2008; Scherer and Palazzo 2007, 2011). In these studies, PCSR is understood to be driven by inadequate market-supporting institutions in host countries, which leads to an increased role of MNCs in leveraging their CSR activities in the policymaking arena (Rettab et al. 2009; Sun et al 2010) or to a minimization of political interventions in MNCs’ operations (Detomasi 2008). With regard to firm-level determinants, scholars have suggested that larger MNCs with greater resources (both human and capital) are more likely to adopt CSR activities in general, including PCSR (McWilliams and Siegel 2001; Udayasankar 2008). Firms that are globally integrated may also be more likely to use PCSR to achieve their global governance initiatives (Scherer and Palazzo 2007, 2011). Scholars have also examined the role of firms’ ‘external dependence’ conditions (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978) in their CSR-type political activities. Greater dependence on external stakeholders has been argued to increase firms’ collaborations with NGOs and environmental groups to gain public votes on policy issues (Hillman and Hitt 1999). Studies have also found that the MNCs operating in highly regulated industries— such as pharmaceuticals—utilities and ‘sin’ sectors—such as tobacco, alcohol, and gambling—are more likely to align their CSR and political activities (Boddewyn 2007; Hillman and Wan 2005; Palazzo and Richter 2005; Sadrieh and Annavarjula 2005). For instance, tobacco industry-specific research shows that PCSR may be used when firms face increased regulatory risks or declining political authority (Fooks et al 2013) or when governments set new agendas related to public health (McDaniel and Malone 2009, 2012; Tesler and Malone 2008; Yang and Malone 2008).

Despite these insights, we suggest that most prior empirical research on the firm-level determinants of PCSR has focused on the context of developed countries and has thus ignored several factors that may be further explained by studying the context of emerging economies. These economies demand specific attention due to increased resource specialization that has created dependencies for MNCs (Meyer et al 2009) and due to recent institutional developments that increasingly render non-CSR political activities detrimental to performance in these countries (Li et al. 2008b). Due to its general assumption that organizations depend on resources held by actors in their external environment (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978), we suggest that it is important to account for both resource dependence and the institutional factors that affect firms’ interactions with external stakeholders. Various authors suggest that, to date, resource dependence theory has been under-exploited as a theoretical basis in studies on corporate political action and have therefore called for its greater use in this area (Dieleman and Boddewyn 2012; Hillman et al 2009). Thus, our study aims to seek answers to the two research questions.

-

1.

What are the firm-level determinants of MNCs’ PCSR in emerging economies?

-

2.

How does the MNC’s criticality of locally available resources, the subsidiary’s international interdependence on the MNC’s network of international operations, and the subsidiary’s local ties to managers of related business and policymakers influence its PCSR activities?

We focus on India as our research context because, first, several scholars have emphasized the role of CSR in India as one of the important mechanisms for engaging in policy discussions with external stakeholders, labor unions and government agencies (Gautam and Singh 2010), promoting development in areas of interest to policymakers (Shrivastava and Venkateswaran 2000), avoiding negative perceptions of corporate actions by the media and other environmental groups (Nambiar and Chitty 2014), and improving overall public relations (Dhanesh 2012). Recently, the Indian government mandated that all companies must spend 2 % of their net profit on social development, and this requirement is expected to increase the estimated annual CSR spending from £0.6 billion to £1.8 billion (Guardian 2014). Thus, we suggest that there is a relatively greater involvement of firms in undertaking PCSR activities in India compared to in other emerging economies. Second, although India is classified as an emerging economy that attracts high levels of foreign direct investment, several resources critical to MNCs still remain under government control (UNCTAD 2014). However, MNCs’ subsidiaries in India have been found to perform better by exploiting local capabilities and expertise, compared to by transferring resources and capabilities from their global network of operations (Anand and Delios 1996; Björkman and Budhwar 2007). MNCs operating in India are also known to create and exploit their managerial and family ties to other related businesses and to policymakers to manage their external dependencies and to improve their financial performance (Upadhya 2004). Thus, India provides a very good setting to conduct this research given that we expect a high level of variability with regard to both MNCs’ involvement in PCSR and the factors that, we argue, affect MNCs’ involvement in PCSR.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: we start with a brief review of the literature on political CSR, resource dependence, and institutional theory to subsequently develop hypotheses linking the criticality of local resources, international interdependence, and managerial ties to foreign firms’ PCSR activities in emerging economies. We then explain the data basis and measures used in our study before presenting the findings. This section is followed by the discussion of our findings and a conclusion that highlights the contributions to research and worthwhile areas for future research.

Literature Review

Political Motivations of MNCs’ CSR Activities

Scholars of CSR have been examining the ‘political’ connotations of MNCs’ CSR activities for an extended period of time. For example, the corporate citizenship literature examines the ‘citizenship behavior’ of firms and its implications in situations of government failure (Matten and Crane 2005). It is argued that when firms assume public responsibilities, they can gain access to multiple stakeholders. The ‘extended corporate citizenship’ concept further suggests that firm-level CSR strategies should be developed to address public problems in the absence of either effective governmental infrastructure or processes, enabling organizations to gain legitimacy (Valente and Crane 2010). However, much of the empirical research on corporate citizenship has been based on local firms’ activities in their domestic market. The need to engage in citizenship activities is further important for firms in an international context where greater ‘liabilities of foreignness’ (Kostova and Zaheer 1999) increase the costs of conducting business and demand greater legitimacy building (Strike et al 2006). In this context, scholars have suggested that, while operating internationally, there is an increasing need for MNCs to engage in CSR activities that are aligned with the interests of local government agencies, local environmental organizations, and international organizations that affect business regulation and policy (Drahos and Braithwaite 2001). Simultaneously, MNCs that operate in a global context pose an increasing need to become important political actors by leveraging their CSR practices and to participate in global governance (Palazzo and Scherer 2006, 2008; Scherer and Palazzo 2007, 2011). CSR activities that involve collaborations with global NGOs (such as Greenpeace) and global governance actors (such as the United Nations Global Compact and the International Standards Organization) have enabled MNCs to share best practices and address global issues, such as reducing carbon emissions for the fight against climate change and to develop and implement global codes of conduct and product quality standards (Baur and Schmitz 2012; Richter 2011).

Linkages Between CSR and CPA

Second, there has been a growing interest in examining the explicit linkages between CSR and corporate political activity (CPA) (Hond et al 2013; Rehbein and Schuler 2013). Although CPA has been predominantly separated from CSR in past research, implicit links have pre-existed, such as in the concepts of ‘constituency building’ (Hillman and Hitt 1999), ‘business diplomacy’ (Saner et al 2000), and ‘public affairs management’ (Baysinger and Woodman 1982; Berg and Holtbrügge 2001; Griffin and Dunn 2004; Meznar and Nigh 1995). In this context, firms have been known to undertake collaborations with NGOs, provide press conferences on their position on specific social issues, sponsor employees’ education and healthcare, undertake advocacy advertising in the media and mobilize grassroots programs. Scholars have suggested that greater alignment between CSR and CPA has led to improved stakeholder relations for MNCs (Waddock and Smith 2000) and has increased the scope of developing ties with political allies (Wang and Qian 2011). Within this context, empirical studies, although limited to the tobacco industry, have provided evidence of firms’ provision of philanthropic donations to engage in strategic relationship building with external stakeholders, such as labor unions and minority groups (McDaniel and Malone 2009; Yang and Malone 2008), and to neutralize opposition to their products (Fooks et al. 2013). Such firms have also engaged in constructive dialogs with external constituents that reduced unfavorable opposition to their operations (Fooks et al. 2013; Fooks and Gilmore 2013). Despite the valuable insights provided by these studies, we suggest that, to date, scholars have not examined the firm-level determinants of PCSR at MNCs’ subsidiary levels, particularly within the context of emerging economies.

Hypotheses Development

We combine insights from three bodies of literature to explain how firm-level determinants affect the extent to which firms engage in PCSR activities.

Resource Criticality and MNC Subsidiaries’ PCSR in Emerging Economies

Resource dependence theory (RDT) emphasizes that organizations depend on resources from their environment, which consists of the society in general, other businesses, interest groups, and the government (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). External stakeholders appear powerful to firms because they can constrain firms’ access to critical resources and subsequently affect their survival (Galaskiewicz 1985; Malatesta and Smith 2011). RDT provides several mechanisms to reduce external dependence on critical resources. These include diversification, interlocking directorates, collective action, and individual political action (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). We suggest that PCSR may also be an important mechanism for reducing external dependence on critical resources, particularly within the context of emerging economies, for the following reasons.

First, within the context of emerging economies, various scholars have emphasized the criticality of local resources (such as low-cost labor and natural resources, networks and relationships with local businesses, and local reputation) to MNCs operating in these markets (Meyer et al. 2009; Peng and Luo 2000; Peng et al. 2008). Furthermore, in emerging economies (compared to in developed countries), MNCs’ continued access to these resources is more likely to be controlled by various external stakeholders, including regulatory and environmental agencies, business groups, and non-governmental organizations (Hoskisson et al. 2000). External resource access is also a greater source of uncertainty for MNCs operating in the context of emerging economies due to the relatively weaker institutional frameworks or institutional voids in emerging economies (Meyer et al. 2009; Peng et al. 2008; Rettab et al. 2009). PCSR activities embedded in activities such as the formation of coalitions with environmental and social groups, public relations advertising in the media on social issues, and the mobilization of grassroots programs increase the scope of ‘discursive processes’ between firms and their societal stakeholders (Rasche and Esser 2006) and allow MNCs to gather the interests of local communities and environmental stakeholders (Scherer and Palazzo 2007). Through such processes, MNCs in emerging economies can extend their corporate citizenship to support external stakeholders (including the government) in shaping the lives of communities that may be affected by MNCs’ access to resources (Arora et al. 2012). Thus, using PCSR, MNCs can better manage stakeholders’ perceptions with regard to MNCs’ resource access and effectively communicate their CSR activities to a variety of external stakeholders, including the government (Rettab et al. 2009). Engaging in PCSR may eventually increase external stakeholders’ trust in MNCs and enhance their local reputation, while allowing them to gaining access to important resources.

Second, although larger MNCs with greater bargaining power are likely able to buffer the uncertainty of access to local resources in emerging economies and to have greater scope accessing local resources, over time, MNCs’ resources in emerging economies may become a source of ‘obsolescing bargain’ (Dauvergne and Lister 2010; Meznar and Nigh 1995). This development will eventually reduce MNCs’ bargaining power vis-à-vis external stakeholders in emerging economies and will require MNCs to align their activities with the interests of external stakeholders (Boddewyn and Doh 2011). A greater cohesion between MNCs and external stakeholders in emerging economies, reflected in the adoption of PCSR, allows MNCs to ‘neutralize’ the effects of such declining political capital (Fooks et al. 2013; Sykes and Matza 1957). By adopting CSR activities that are better synchronized with the interests of political stakeholders, for instance, by exploiting government policy arrangements with regard to social and economic development, MNCs in emerging economies can enhance their political legitimacy (Zhao 2012).

For instance, Coca-Cola is critically dependent on access to ground water in its local environments and is thus affected by any regulation that restricts its use of water (Taylor 2000). In 2004, local officials in the Indian state of Kerala asked for the closure of one of Coca-Cola’s bottling plants because it reduced the quantity of water available to local farmers. Although the High Court of Kerala overturned the decision of local officials (Hills and Welford 2005), in due course, Coca-Cola seems to have adopted a PCSR approach in India, reflected in its establishment of the ‘Anandana’—a foundation that focuses on water sustainability issues in India (Coca-Cola 2012). This action also enables it to manage on-going issues over its access to ground water in India. Therefore, we suggest that, when local resources in emerging economies are critical to MNCs, uncertainty over access to these critical resources can be reduced through the use of PCSR.

Hypothesis 1

The likelihood of MNCs’ subsidiaries to adopt PCSR in emerging economies increases with the extent to which local resources are critical to the subsidiaries.

International Interdependence and MNC Subsidiaries’ PCSR in Emerging Economies

International interdependence has been defined as the extent to which the outcomes of a foreign subsidiary are influenced by the actions of another unit (subsidiary or headquarters) of the MNC operating in a different country (O’Donnell 2000). A subsidiary’s international interdependence is likely to stem from an MNC’s strategy of global integration versus local responsiveness (Bartlett and Ghoshal 2002; O’Donnell 2000; Roth and Morrison 1990). Scholars have suggested that MNCs that focus on global integration derive their international competitiveness from resources and capabilities developed at subsidiary levels and the effective transfer of these resources and capabilities across the MNC’s network of international operations (Meyer and Su 2014; Subramaniam and Watson 2006). Thus, among globally integrated MNCs, country-level subsidiaries often provide vital inputs to other foreign subsidiaries or to the headquarters. Such increased interdependence among international subsidiaries impacts a focal subsidiary’s external dependence on a host country’s local resources (O’Donnell 2000; Subramaniam and Watson 2006) and has been known to affect the governmental affairs activities of subsidiaries (Blumentritt and Rehbein 2008). We suggest that this will consequently affect the extent to which subsidiaries will participate in PCSR activities in emerging economies for the following reasons.

First, scholars have suggested that, in general, when MNCs are exposed to higher levels of interdependence, there is the risk that problems encountered by one subsidiary may have a ‘domino effect’ and can cause serious problems for the MNC as a whole (Hillman and Wan 2005). For this reason, at higher levels of interdependence, subsidiaries have greater pressure to secure host country resources that may be critical for the effective functioning of the MNC as a whole. This pressure (and risk) may be higher for subsidiaries that operate within the specific context of emerging economies because, in these economies, the resources and capabilities that MNCs can tap into for their successful global functioning are available at a lower cost; however, due to institutional idiosyncrasies in these economies, access to these resources may be constrained by a variety of social and political stakeholders (Meyer and Su 2014). Engaging in PCSR enables foreign subsidiaries to increase their legitimacy in emerging economies and allows them to gain access to critical resources controlled by stakeholders. Thus, by adopting PCSR, highly interdependent subsidiaries may reduce the risk that the MNCs’ global operations will be affected due to a lack of access to such vital resources in emerging economies (Boddewyn and Doh 2011). Subsequently, subsidiaries with greater degrees of international interdependence will pursue PCSR to a greater extent.

Second, subsidiaries that are highly interdependent on other foreign subsidiaries or the MNC headquarters are likely to have more complex organizational structures than subsidiaries that are less interdependent (O’Donnell 2000). To reduce this complexity, highly interdependent subsidiaries are expected to maintain a higher level of ‘internal legitimacy,’ defined as the acceptance and approval of a subsidiary’s actions by other subsidiaries and by the parent firm or MNC headquarters (Kostova and Zaheer 1999). Therefore, highly interdependent subsidiaries are likely to be characterized by a greater ethnocentricity of organizational values and norms (O’Donnell 2000). In emerging economies, due to the absence of legitimate mechanisms and frameworks for business-government interaction, mechanisms such as creating and managing direct relationships with state officials may increase an MNC’s ‘external legitimacy’ within the host country. However, such activities may be linked to corruption and may have adverse effects on MNCs’ global reputation and values, ultimately having a negative effect on the subsidiary’s internal legitimacy within the MNC as a whole (Li et al. 2008a). Alternatively, due to their relatively ethical nature, PCSR activities may be more desirable to protect their organizational values and norms at higher levels of interdependence among an MNC’s subunits.

For instance, technology firms such as IBM, Cisco, and Microsoft critically depend on skilled workers available at a lower cost in India to develop their products and services for a global market. Additionally, they also depend on their global reputation and must therefore engage ethically with external stakeholders in India. Therefore, these companies collaborate with a variety of development agencies such as the Centre for Development of Advanced Computing (CDAC) and provide education and training on advanced technologies, which helps ensure a sustained supply of specialized skilled labor (Aggarwal 2008), indicating the use of PCSR. Accordingly, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2

The likelihood of MNCs’ subsidiaries to adopt PCSR activities in emerging economies increases with the extent to which the focal subsidiary (within the emerging economy) is interdependent on the MNC’s headquarters and other foreign subsidiaries.

Managerial Ties and MNC Subsidiaries’ PCSR in Emerging Economies

First, according to institutional theory, firms that operate in international markets need to conform to the ‘rules of the game’ (North 1996) to gain legitimacy and reduce their ‘liabilities of foreignness’ (Kostova and Zaheer 1999). According to the strategic approach to seeking legitimization, firms need to ‘adopt managerial perspectives instrumentally to manipulate and deploy evocative symbols in order to garner societal support’ (Suchman 1995, p. 572). An important instrument of seeking legitimacy in emerging economies has been the development of managerial ties not only with political stakeholders but also with related businesses such as suppliers, key customers, marketing collaborators, and technological collaborators (Li et al. 2008b; Luo 2001; Peng and Luo 2000; Sheng et al. 2011). Managerial ties increase the scope for MNCs’ subsidiaries to continuously interact informally with policymakers and local communities, which they can use to share each other’s best practices and learning experiences, particularly on issues such as compliance to licenses, software piracy, or use of child labor (Bennett 1995, 1998; Boddewyn 2007).

Second, combining institutional theory with the notions of social capital (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998), we suggest that, in emerging markets, engaging in PCSR activities requires MNCs to embed deeply within the complex governance of these countries’ structures, which consist of government actors, businesses with high bargaining power, and other social and environmental groups. Managerial ties facilitate such embedding and enable MNCs to understand ‘situational’ needs (Berg and Holtbrügge 2001) and to initiate specific CSR programs. More specifically, managerial ties with policymakers also help MNCs’ subsidiaries to gain information on state-backed CSR programs and meet the state’s need in areas of policy priority (Zhao 2012), and such information may not be available locally in emerging markets (Dubini and Aldrich 1991). Therefore, we suggest that MNCs’ subsidiaries that cultivate stronger ties with local managers are better able to initiate PCSR programs that may be used to either influence future public policy or gain from existing government schemes in emerging economies, as already found in some recent research (e.g., Zhao 2012). Overall, we suggest the following:

Hypothesis 3

The likelihood of MNCs’ subsidiaries to adopt PCSR activities in emerging economies increases with the extent to which the subsidiaries have developed local managerial ties in these economies.

Methodology

Data and Sample

Our data were collected through a web-based questionnaire survey of the top managers (CEOs, Managing Directors, or Country Managers) of foreign subsidiaries operating in India. We obtained the “India MNC Directory 2011–12’’ from Amelia Publications; it provided the contact information for the top managers of over 3000 firms. The directory included contacts for both (1) partly or wholly foreign-owned companies in India and (2) Indian firms that have overseas operations. The foreign-owned companies were headquartered in nine countries (the USA, the UK, Australia, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Malaysia, Sweden, and Switzerland). We decided to exclude subsidiaries in which the foreign partner held less than 25 % of the equity because, in such subsidiaries, foreign partners may have less control over the subsidiary’s decisions such as those related to CSR (Delios and Beamish 1999). We also excluded subsidiaries with incomplete contact details. This left us with a list of 1910 foreign firms, each of which, in 2011, received a link to our web-based questionnaire via email. A very large number (900) of emails could not be delivered and ‘bounced,’ indicating that only 1010 emails were successfully delivered. After email and telephone follow-ups over a three-month period, 120 responses were obtained. We excluded fifteen responses due to missing data, resulting in 105 usable responses (10.24 %). The response rate was low due to the sensitivity of the questions asked, although this rate is similar to prior research on similar topics such as public affairs and political activities (e.g., Griffin and Dunn 2004; Keillor et al. 1997; Puck et al. 2013). In addition, the survey was conducted at a time when the Anna Hazare-led anti-corruption movement had gained momentum in India (Sengupta 2012), which may have further reduced firms’ willingness to provide information on their political strategies. Table 1 shows the distribution of the MNCs in our sample by home country.

Measures

To measure MNCs’ PCSR as our dependent variable, we asked survey participants to indicate the level of importance of three activities: (1) public relations advertising in the media on specific issues related to policy; (2) mobilizing grassroots political programs (such as organizing demonstrations, signature campaigns, using social networks to organize communities, etc.); and (3) forming coalitions with other organizations not in their horizontal or sectorial trade associations (such as with environmental groups and social groups). We used a five-point Likert-type scale (α = 0.80, see appendix for items). These items closely match the activities that define firms’ PCSR (Rehbein and Schuler 2013; Scherer and Palazzo 2007), and therefore, we suggest that our measure provides a valid and reliable indicator of PCSR.

To measure resource criticality as our first independent variable, we first measured the level of importance that MNCs placed on nine resources (finance, land, up-to-date production machinery, unskilled workers, semi-skilled workers, raw materials, technological know-how, highly skilled employees, and reputation), following Srivastava et al. (2001). We then conducted a confirmatory factor analysis and found that these resources neatly fell into two categories: tangible (land, up-to-date production machinery, unskilled workers, and raw materials) and intangible (technological know-how, highly skilled employees, and reputation). We dropped two items (finance and semi-skilled workers) due to their low item-to-total correlation ratios. Thus, our overall resource criticality was measured using seven items (see appendix). We took the average of the four items related to (1) tangible resource criticality (α = .826) and (2) intangible resource criticality (α = .701) to measure the resource criticality associated with tangible and intangible resources.

To measure a subsidiary’s international interdependence, we used the constructs previously suggested by Subramaniam and Watson (2006) and O’Donnell (2000). We used four items to measure the extent to which other foreign subsidiaries and headquarters influence the outcomes of the subsidiary, using a 5-point Likert scale (α = 0.71, see appendix for items).

To measure managerial ties, we used the survey items suggested in previous studies by Sheng et al. (2011) and Peng and Luo (2000). We asked survey participants about their personal relationships with: (1) officials in various levels of government; (2) regulatory and supporting organizations, such as tax bureaus, state banks, and commercial administration bureaus; (3) supplier firms; (4) customer firms; (5) competitor firms; (6) marketing-based collaborators; and (7) technological collaborators. We then separated these into two types: (1) political ties (α = 0.88) and (2) business ties (α = 0.61), based on the connections with political decision makers and other related businesses.

We controlled for various factors that have been shown to affect MNCs’ PCSR in host countries. These included subsidiary size (McWilliams and Siegel 2001; Udayasankar 2008), measured by the number of employees; subsidiary age, measured by the number of years the subsidiary has been operating in India; industry type (Cottrill 1990), coded as a dummy for manufacturing (0) and services (1); and local ownership, measured by the percentage of assets owned by the foreign parent or partners in the Indian subsidiary. Given the importance that prior research has attributed to institutional factors in affecting firms’ choice of approach to CPA, we also controlled for the institutional distance between India and the foreign firms’ home country. In line with past research (e.g., Dikova 2009), this factor was measured using the differences in the scores for government effectiveness, political stability, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption obtained from the World Bank’s worldwide governance index.

To avoid common method bias, we used several ex ante measures during the design of our questionnaire (Chang et al. 2010). We adjusted the questionnaire items to use terms that were familiar to Indian managers to minimize ambiguity. During the questionnaire administration, we also assured the respondents of their confidentiality and anonymity and highlighted that there are no right or wrong answers. We also used two ex post approaches to check for potential common method bias. First, we used Harman’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al. 2003). We found that seven factors accounted for 68.9 % of the variance and that the highest factor accounted for 19.8 % of the total variance, which did not indicate common method bias. Second, following Lindell and Whitney (2001), we also used the partial correlation procedure, using a marker variable (managerial autonomy) that was not related to either resource dependence or PCSR and that therefore could be used to measure the extent of common method bias. This variable was not significantly associated with any of our variables, and the theoretical relationships among the variables of interest were not affected, supporting the absence of common method bias.

We also checked for a potential non-response bias by comparing the responses of “early” respondents (first 30 responses) and “late” respondents (last 30 responses) using the extrapolation test (e.g., Armstrong and Overton 1977; Keillor and Hult 2004). This method assumes that late respondents are similar to projected non-respondent and that their responses may be significantly different from those of the early respondents. We conducted pairwise comparisons between the means of early and late respondents for our dependent and independent variables (i.e., PCSR, resource criticality, subsidiary interdependence, and managerial ties). We found that (see Table 2) there were no significant differences (p > 0.1) between the responses of the early respondents and the late respondents, indicating that a non-response bias did not exist.

Results

Table 3 provides the means, standard deviations (SD), and correlations. Although there were some correlations among our independent variables (see Table 1), these were very low, and therefore, multicollinearity was not considered to be an issue. The means and SDs of the predictor variables indicate a good representation of firms with both high and low levels of resource importance, managerial ties, and international subsidiary integration.

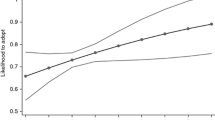

We used linear multiple regression to test our hypotheses. Table 4 shows the regression results.

Model 1 shows the baseline model with the control variables only. Of the control variables, firm size appears to have a very small but statistically significant and positive effect on firms’ PCSR (p < .01). This result indicates that large MNCs are more likely to engage in PCSR compared to smaller MNCs in India. Local ownership also appears to have a small but statistically significant and positive effect on firms’ PCSR (p < .05). This finding indicates that subsidiaries that had greater local shareholding were more likely to engage in PCSR compared to subsidiaries that had greater foreign shareholding.

In Model 2, we add the predictor variables to the baseline model. The results of model 2 (see Table 4) show a significant positive relationship (p < .01) between resource criticality and PCSR, which supports our first hypothesis. Our second hypothesis, which suggested a positive association between a subsidiary’s international interdependence and PCSR, is not supported by our data. Hypothesis 3, which suggested a positive association between managerial ties and the firms’ extent of PCSR, is partially supported. The results show that subsidiaries’ political ties have a significant (p < .05) association with PCSR; but business ties do not have a significant association with PCSR. Thus, our results provide support for two of our three hypotheses.

Discussion

Our study contributes to the emerging notion of PCSR (Detomasi 2008; Scherer and Palazzo 2007, 2011). We extend the findings of prior empirical studies on the firm-level determinants of PCSR, such as firms’ dependency on specific stakeholders (e.g., minority groups and labor unions) (McDaniel and Malone 2009; Yang and Malone 2008) and their need to re-gain political authority, shape favorable regulation, and neutralize opposition by external stakeholders (Fooks et al. 2013; Fooks and Gilmore 2013). Although these studies have examined the firm-level determinants of PCSR within the context of the tobacco industry, we extend this research by examining the firm-level determinants of PCSR across a variety of industries and in the context of an emerging economy (i.e., India). We also contribute to the findings of previous studies that have focused on firms’ need to gain legitimacy while operating in an international context (particularly in emerging economies) through their PCSR activities (Beddewela and Fairbrass 2015; Rettab et al. 2009; Zhao 2012). Although these studies have focused on the institutional context of emerging economies, such as the lack of effective communication channels and effective business-government interfaces, necessitating the adoption of PCSR, our findings reveal the influence of ‘resource dependency’ conditions that require MNCs to align their CSR activities with the interests of external stakeholders (Baur and Schmitz 2012; Boddewyn and Doh 2011; Meznar and Nigh 1995).

First, we find a strong positive association between MNC subsidiaries’ resource criticality in India and their adoption of PCSR. We also find that this relationship is significant for resource criticality associated with both tangible and intangible resources. The support for Hypothesis 1 shows that, in India, MNCs that assume greater criticality of locally available resources are more likely to adopt PCSR as a means of reducing the uncertainty over access to resources that are critical for their operations. In this regard, our results extend the findings of previous studies that have indicated the use of PCSR as a means of overcoming the constraints associated with external dependence on favorable regulation for firms’ operations (Fooks et al. 2013, 2011). Our findings also support the arguments of prior studies that have suggested that PCSR enables MNCs in emerging economies to better communicate the worthiness of their actions in accessing critical local resources to a variety of external stakeholders, and the PCSR helps change external stakeholders’ perceptions of MNCs’ access to local resources (Child and Tsai 2005; Rettab et al. 2009). By highlighting the role of resource dependency on firms’ PCSR activities, we also contribute to existing studies on the political activities of firms, such as ‘constituency building’ (Hillman 2003; Hillman and Wan 2005), ‘business diplomacy’ (Saner et al. 2000), and ‘public affairs management’ (Baysinger and Woodman 1982; Berg and Holtbrügge 2001; Griffin and Dunn 2004; Meznar and Nigh 1995).

Second, our study contributes to explaining the link between a subsidiary’s international interdependence (O’Donnell 2000; Subramaniam and Watson 2006) and the adoption of PCSR. We argued that subsidiaries in emerging economies that are highly interdependent on the MNC’s headquarters and other foreign subsidiaries are more likely to adopt PCSR due to their increased levels of local resource criticality and due to the relatively ethical nature of PCSR, enabling a greater ethnocentricity of values and norms across the MNC’s global operations. However, our empirical evidence does not support our argument (i.e., Hypothesis 2). There may be several reasons for the unexpected statistical insignificance of this relationship in our findings. It has been noted that the relationship between subsidiaries’ interdependence on the MNC’s network of global operations and the political activities it adopts in individual host countries can be complex (Blumentritt 2003; Blumentritt and Nigh 2002). Scholars have suggested that a focal subsidiary’s ability to influence the host government to continually procure local resources for the MNC’s global operations depends on the MNC’s bargaining power vis-à-vis the host government (Blumentritt and Rehbein 2008; Moon 1988). Furthermore, a subsidiary’s extent of local resource criticality within a host country and its subsequent involvement in PCSR may vary depending on whether the subsidiary provides vital outputs from its operations in the focal host country (e.g., manufactured products or raw materials) or on whether it gains vital inputs to its operations from other foreign subsidiaries (e.g., strategic practices, technologies) (Mascarenhas 1984).Footnote 1 Alternatively, scholars have also suggested that, for more interdependent subsidiaries, other subsidiaries may act as alternative sources of supply, thus reducing dependence on resources within a specific host country (Casciaro and Piskorski 2005; Malatesta and Smith 2011). In this context, the levels of local resource criticality for highly interdependent subsidiaries may be lower, and therefore, they may be less likely to adopt PCSR. However, we suggest that this alternative hypothesis warrants further research.

Third, we find partial support for our argument (Hypothesis 3) regarding the role of managerial ties for the extent to which firms adopt PCSR. Based on institutional and social capital perspectives, we argued that, in emerging economies, informal managerial linkages to both local businesses (business ties) and political stakeholders (political ties) enable foreign subsidiaries to embed in the complex governance structures of these economies and to become better equipped to adopt PCSR programs that are aligned with the interests of their related businesses and political stakeholders (Rizopoulos and Sergakis 2010; Sun et al. 2010; Zhao 2012). We find a significant positive association between subsidiaries’ political ties and the extent to which they adopt PCSR; however, our empirical findings do not show a significant association between business ties and the extent to which they adopt PCSR. Thus, although our findings do not support the relationship between business ties and PCSR as expected, they further highlight the inextricability of CPA and CSR, particularly in the context of emerging economies. In this context, our findings suggest that firms’ political ties may be aligned with their CSR activities, which is similar to the findings in certain recent studies (Fooks et al. 2013).

Finally, the findings from our control variables further enhance the findings of past studies conducted in India that showed that CSR was only a consideration among the large firms in the corporate sector (Khan 1981; Khan and Atkinson 1987; Krishna 1992). Our findings show a small but significant (p < 0.1) association between firm size and PCSR, allowing us to suggest that engaging in PCSR is an expensive activity and therefore large firms with greater resources are better equipped to employ PCSR, as previously suggested (McWilliams and Siegel 2001; Udayasankar 2008). Our findings also show a strong significant association between the industry and the extent to which subsidiaries use PCSR. In this regard, our study finds that firms that belong to the ‘services’ sector are more likely to adopt PCSR than those in the ‘manufacturing’ sector. Because the services sector in India is being increasingly regulated (e.g., retail and banking and financial services), our findings extend prior insights that have highlighted the role of industry regulation on PCSR (Fooks et al. 2013; Hillman and Hitt 1999; Sadrieh and Annavarjula 2005). Our findings also show a small but significant association between local ownership and PCSR, indicating that foreign subsidiaries characterized by greater local ownership are more likely to engage in PCSR. However, we do not find evidence of a direct association between institutional distance between the subsidiary’s home country and host country (India) and the extent to which it adopts PCSR, although, based on prior research, we expected that the differences in regulatory environments increase MNCs’ adoption of PCSR as a means of overcoming their liabilities of foreignness and gaining local legitimacy (Kostova and Zaheer 1999). We suggest that this issue is an interesting question that warrants further research.

Conclusions

In our study, we investigated the firm-level determinants that influence the adoption of PCSR in emerging economies. Combining resource dependence theory (RDT), institutional theory, and social capital perspectives, we identified three factors that affect the extent to which MNCs may be likely to adopt PCSR in emerging economies. More specifically, we investigated the extent to which the criticality of local resources, subsidiaries’ international interdependence and managerial ties influence MNCs’ PCSR in these newly liberalized markets. In doing so, we contribute to the growing literature on PCSR (Detomasi 2007, 2008; Scherer and Palazzo 2007, 2011) and the integration between CSR and CPA (Hond et al. 2013; Rehbein and Schuler 2013). By investigating the political role of CSR activities, we also extend the previous research on the political activities of firms anchored in RDT (e.g., Dieleman and Boddewyn 2012; Meznar and Nigh 1995), which, to date, has focused on the distribution of bargaining power between MNCs and host governments (Eden and Molot 2002; Ramamurti 2001). Using resource dependence theory as a theoretical anchor, we also respond to the call for a better integration of the insights provided by this theory into the literature on CPA (Hillman et al. 2009). The previous research based on RDT has identified various methods for managing a firm’s external dependence on critical resources, such as diversification, interlocking directorates, collective action, and individual political action (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978, 2003). We contribute to this on-going discussion in RDT by suggesting the use of CSR as a method for managing external dependence on critical resources. We suggest that, using PCSR activities, MNCs in emerging economies will be more likely to ensure continued access to critical external resources.

Our findings also have a number of important managerial implications for MNCs conducting business in India. Prior research has shown that the perceptions of CSR in India have been changing from passive philanthropy (Khan and Atkinson 1987) and the use of CSR as a means of gaining short-term benefits such as tax exemptions (Narwal and Sharma 2008) to a greater understanding of its role in long-term corporate brand development and improving financial performance (Mishra and Suar 2010). Simultaneously, perceptions of corporate attempts to influence policymaking in India have also been progressing from exploiting family and other informal connections to the establishment of legitimate mechanisms for the business-government interface, such as the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) and the Associated Chambers of Commerce (Assocham) (Kochanek 1996; Mohan 2001). However, several resources crucial to MNCs that operate in India continue to remain tightly controlled by external stakeholders such as the government and its regulatory agencies (Kozhikode and Li 2012). In this context, first, our study shows that the integration of CSR and CPA can be a means of reducing the uncertainty over accessing critical external resources controlled by various stakeholders. Such integration achieved through the adoption of PCSR can also be used to safeguard critical resources such as reputation and credibility. Second, various studies have also indicated the importance of managerial ties to policymakers in India as a means of addressing institutional voids such as information asymmetries and resource access (Upadhya 2004). In this context, our findings on the positive association between MNCs’ political ties and the adoption of PCSR show that on-going interactions with external stakeholders (vs. one-off interactions when specific issues arise) enable firms to better understand the specific needs of local communities and to align their CSR programs with such needs.

There are a number of limitations to this study that open new avenues for further research on the political orientation of CSR activities in emerging economies. First, we recognize that our measure of PCSR includes a fairly small number of activities among a larger set presented more recently in the literature. For instance, Detomasi (2008) suggests that PCSR may also include MNCs’ collective action, i.e., participating in sub-national trade associations and activism. Although our measure of PCSR includes MNCs’ collaborations with governance actors at a national level, it does not account for MNCs’ involvement at a sub-national level, such as the needs of provinces with regard to economic development, which may potentially influence MNCs’ PCSR at a sub-national level. Our measures also exclude MNCs’ engagement with global governance actors such as the United Nations Global Compact, World Trade Organization, International Monetary Fund and World Bank. Future research may therefore include additional measures of PCSR that focus on sub-national and global contexts. A second limitation of this research is the relatively small sample size, which limits the statistical analysis to direct effects. Because the mechanisms that lead firms to adopt PCSR may be complex, a larger sample may have increased the possibility of accounting for potential moderating effects. For instance, a subsidiary’s international interdependence may potentially moderate the relationship between resource criticality and the involvement of firms in PCSR.Footnote 2 Our questionnaire included questions on both CSR-based and non-CSR political activities, and because asking questions on political activities is highly sensitive, the inclusion of these types of questions may have affected the sample size and response rate. Although we did not find evidence of a non-response bias, a higher response rate reduces the chances of such bias in survey research (Kanuk and Berenson 1975). In the future, questionnaire surveys may be dedicated to PCSR to have a larger sample size and a higher response rate. Third, given that prior studies have highlighted the importance of PCSR for specific industries, e.g., tobacco (Fooks et al. 2013; Tesler and Malone 2008), our classification of industries as manufacturing or services provides limited insights. Again, due to our smaller sample size, we could not account for the effects of a greater variety of industries. This issue may be a worthwhile avenue for future research to explore. Finally, due to differences in political environments across emerging economies, our empirical evidence from India limits the generalizability of the determinants that increase MNCs’ involvement in PCSR. Simultaneously, our firm-level determinants (based on resource dependence theory)—particularly resource criticality and international subsidiary dependence—can also be argued to affect PCSR in the context of industrialized countries. Therefore, some worthwhile areas for future research may be to identify the differences in the firm-level factors that affect PCSR in a number of emerging economies and also to compare the firm-level determinants of PCSR in emerging versus industrialized countries. Despite these limitations, we suggest that our study enhances our understanding of the MNCs’ PCSR in emerging economies and addresses the growing need for a greater appreciation of the intersection between CSR and CPA.

Notes

We thank one of our anonymous reviewers for noting this issue.

We thank one of our anonymous reviewers for noting this issue.

Abbreviations

- CSR:

-

Corporate social responsibility

- MNC:

-

Multinational corporation

- NGO:

-

Non-governmental organization

- PCSR:

-

Political corporate social responsibility

- RDT:

-

Resource dependence theory

References

Aggarwal, A. (2008). Emerging markets labor supply in the Indian IT industry. Communications of the ACM, 51(12), 21–23.

Anand, J., & Delios, A. (1996). Competing globally: How Japanese MNCs have matched goals and strategies in India and China. The Columbia Journal of World Business, 31(3), 50–62.

Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. (1977). Estimating nonresponse bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research, 14, 396–402.

Arora, B., Kazmi, A., & Bahar, S. (2012). Performing citizenship: An innovative model of financial services for rural poor in India. Business and Society, 51(3), 450–477.

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. (2002). Managing across borders : the transnational solution. Boston: Harvard Business School.

Baur, D., & Schmitz, H. P. (2012). Corporations and NGOs: When accountability leads to co-optation. Journal of Business Ethics, 106(1), 9–21.

Baysinger, B. D., & Woodman, R. W. (1982). Dimensions of the public affairs/government relations function in major American corporations. Strategic Management Journal, 3(1), 27–41.

Beddewela, E., & Fairbrass, J. (2015). Seeking legitimacy through CSR: Institutional pressures and corporate responses of multinationals in Sri Lanka. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2478-z.

Bennett, R. J. (1995). The logic of local business associations: An analysis of voluntary chambers of commerce. Journal of Public Policy, 15(03), 251–279.

Bennett, R. J. (1998). Explaining the membership of voluntary local business associations: The example of British Chambers of Commerce. Regional Studies, 32(6), 503–514.

Berg, N., & Holtbrügge, D. (2001). Public affairs management activities of german multinational corporations in India. Journal of Business Ethics, 30(1), 105–119.

Björkman, I., & Budhwar, P. (2007). When in Rome…?: Human resource management and the performance of foreign firms operating in India. Employee Relations, 29(6), 595–610.

Blumentritt, T. (2003). Foreign subsidiaries’ government affairs activities: The influence of managers and resources. Business and Society, 42(2), 202–233.

Blumentritt, T., & Nigh, D. (2002). The integration of subsidiary political activities in multinational corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 33(1), 57–77.

Blumentritt, T., & Rehbein, K. (2008). The political capital of foreign subsidiaries. Business & Society, 47: 242–263.

Boddewyn, J. J. (2007). The internationalization of the public-affairs function in U.S. Multinational Enterprises. Business and Society, 46(2), 136–173.

Boddewyn, J. J., & Doh, J. (2011). Global strategy and the collaboration of MNEs, NGOs, and governments for the provisioning of collective goods in emerging markets. Global Strategy Journal, 1(3–4), 345–361.

Casciaro, T., & Piskorski, M. J. (2005). Power imbalance, mutual dependence, and constraint absorption: A closer look at resource dependence theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(2), 167–199.

Chang, S.-J., van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2010). From the Editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2), 178–184.

Child, J., & Tsai, T. (2005). The dynamic between firms’ environmental strategies and institutional constraints in emerging economies: Evidence from China and Taiwan. Journal of Management Studies, 42(1), 95–125.

Coca-Cola. (2012). Anandana: Coca-Cola India Foundation. Retrieved, from 16 April, 2013 http://www.anandana.org/

Cottrill, M. T. (1990). Corporate social responsibility and the marketplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(9), 723–729.

Dauvergne, P., & Lister, J. (2010). The power of big box retail in global environmental governance: bringing commodity chains back into IR. Millennium-Journal of International Studies, 39(1), 145–160.

Delios, A., & Beamish, P. W. (1999). Ownership strategy of Japanese firms: transactional, institutional, and experience influences. Strategic Management Journal, 20(10), 915–933.

Detomasi, D. (2007). The multinational corporation and global governance: Modelling global public policy networks. Journal of Business Ethics, 71(3), 321–334.

Detomasi, D. (2008). The political roots of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(4), 807–819.

Dhanesh, G. S. (2012). Better stay single? Public relations and CSR leadership in India. Public Relations Review, 38(1), 141–143.

Dieleman, M., & Boddewyn, J. J. (2012). Using organization structure to buffer political ties in emerging markets: A case study. Organization Studies, 33(1), 71–95.

Dikova, D. (2009). Performance of foreign subsidiaries: does psychic distance matter? International Business Review, 18(1), 38–49.

Dorfman, L., Cheyne, A., Friedman, L. C., Wadud, A., & Gottlieb, M. (2012). Soda and tobacco industry corporate social responsibility campaigns: how do they compare? PLoS Medicine, 9(6), e1001241.

Drahos, P., & Braithwaite, J. (2001). The globalisation of regulation. Journal of Political Philosophy, 9(1), 103–128.

Dubini, P., & Aldrich, H. E. (1991). Personal and extended networks are central to the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 6(5), 305–313.

Economist, T. (2012). India’s telecoms scandal: Can you prepone my 2G spot? Retrieved, from 17 April, 2013 http://www.economist.com/node/21546827

Eden, L., & Molot, M. A. (2002). Insiders, outsiders and host country bargains. Journal of International Management, 8(4), 359–388.

Ellison, B., Moller, D., & Rodriguez, M. (2002). Hindustan Lever re-invents the wheel. IESE, University of Navarra: Barcelona (unpublished).

Fooks, G. J., & Gilmore, A. B. (2013). Corporate philanthropy, political influence, and health policy. PLoS One, 8(11), e80864.

Fooks, G. J., Gilmore, A., Collin, J., Holden, C., & Lee, K. (2013). The limits of corporate social responsibility: Techniques of neutralization, stakeholder management and political CSR. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(2), 283–299.

Fooks, G. J., Gilmore, A. B., Smith, K. E., Collin, J., Holden, C., & Lee, K. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and access to policy élites: an analysis of tobacco industry documents. PLoS Medicine, 8(8), e1001076.

Galaskiewicz, J. (1985). Interorganizational relations. Annual Review of Sociology, 11, 281–304.

Gautam, R., & Singh, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility practices in India: a study of top 500 companies. Global Business and Management Research: An International Journal, 2(1), 41–56.

Gond, J.-P., Kang, N., & Moon, J. (2011). The government of self-regulation: On the comparative dynamics of corporate social responsibility. Economy and Society, 40(4), 640–671.

Griffin, J. J., & Dunn, P. (2004). Corporate public affairs: Commitment, resources, and structure. Business and Society, 43(2), 196–220.

Hillman, A. J. (2003). Determinants of political strategies in U.S. multinationals. Business and Society, 42(4), 455–484.

Hillman, A. J., & Hitt, M. A. (1999). Corporate political strategy formulation: A model of approach, participation, and strategy decisions. The Academy of Management Review, 24(4), 825–842.

Hillman, A. J., & Wan, W. P. (2005). The determinants of MNE subsidiaries’ political strategies: evidence of institutional duality. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(3), 322–340.

Hillman, A. J., Withers, M. C., & Collins, B. J. (2009). Resource dependence theory: A review. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1404–1427.

Hills, J., & Welford, R. (2005). Coca-Cola and water in India. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 12(3), 168–177.

Hond, F., Rehbein, K., Bakker, F. G., & Lankveld, H. K. V. (2013). Playing on two chessboards: Reputation effects between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate political activity (CPA). Journal of Management Studies, (In Press). doi: 10.1111/joms.12063

Hoskisson, R. E., Eden, L., Lau, C. M., & Wight, M. (2000). Strategy in emerging economies. The Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 249–267.

Kanuk, L., & Berenson, C. (1975). Mail surveys and response rates: A literature review. Journal of Marketing Research, 12(4), 440–453.

Keillor, B. D., Boller, G. W., & Ferrell, O. C. (1997). Firm-level political behavior in the global marketplace. Journal of Business Research, 40(2), 113–126.

Keillor, B. D., & Hult, G. (2004). Predictors of firm-level political behavior in the global business environment: an investigation of specific activities employed by US firms. International Business Review, 13(3), 309–329.

Khan, A. F. (1981). Managerial responses to social responsibility challenge. Indian Management, 20(9), 13–19.

Khan, A. F., & Atkinson, A. (1987). Managerial attitudes to social responsibility: A comparative study in India and Britain. Journal of Business Ethics, 6(6), 419–432.

King, A. A., & Lenox, M. J. (2000). Industry self-regulation without sanctions: the chemical industry’s responsible care program. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 698–716.

Kochanek, S. A. (1996). Liberalisation and business lobbying in India. Journal of Commonwealth & Comparative Politics, 34(3), 155–173.

Kostova, T., & Zaheer, S. (1999). Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 64–81.

Kozhikode, R. K., & Li, J. (2012). Political pluralism, public policies, and organizational choices: Banking branch expansion in India, 1948–2003. Academy of Management Journal, 55(2), 339–359.

Krishna, C. G. (1992). Corporate social responsibility in India. New Delhi: Mittal Publications.

Li, J. J., Poppo, L., & Zhou, K. Z. (2008a). Do managerial ties in China always produce value? Competition, uncertainty, and domestic vs. foreign firms. Strategic Management Journal, 29(4), 383–400.

Li, J. J., Zhou, K. Z., & Shao, A. T. (2008b). Competitive position, managerial ties, and profitability of foreign firms in China: An interactive perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(2), 339–352.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121.

London, T., & Hart, S. L. (2004). Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: beyond the transnational model. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(5), 350–370.

Luo, Y. (2001). Toward a cooperative view of MNC-host government relations: Building blocks and performance implications. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(3), 401–419.

Luo, Y. (2006). Political behavior, social responsibility, and perceived corruption: a structuration perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 747–766.

Malatesta, D., & Smith, C. R. (2011). Resource dependence, alternative supply sources, and the design of formal contracts. Public Administration Review, 71(4), 608–617.

Mascarenhas, B. (1984). The coordination of manufacturing interdependence in multinational companies. Journal of International Business Studies, 15(3), 91–106.

Matten, D., & Crane, A. (2005). Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. The Academy of Management Review, 30(1), 166.

Maxwell, J. W., Lyon, T. P., & Hackett, S. C. (2000). Self-regulation and social welfare: The political economy of corporate environmentalism*. The Journal of Law and Economics, 43(2), 583–618.

McDaniel, P. A., & Malone, R. E. (2009). Creating the “desired mindset”: Philip Morris’s efforts to improve its corporate image among women. Women and Health, 49(5), 441–474.

McDaniel, P. A., & Malone, R. E. (2012). British American Tobacco’s partnership with Earthwatch Europe and its implications for public health. Global Public Health, 7(1), 14–28.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117–127.

Meyer, K. E., Estrin, S., Bhaumik, S. K., & Peng, M. W. (2009). Institutions, resources, and entry strategies in emerging economies. Strategic Management Journal, 30(1), 61–80.

Meyer, K. E., & Su, Y.-S. (2014). Integration and responsiveness in subsidiaries in emerging economies. Journal of World Business (In Press). doi: 10.1016/j.jwb.2014.04.001

Meznar, M. B., & Nigh, D. (1995). Buffer or Bridge? Environmental and organizational determinants of public affairs activities in American firms. Academy of Management Journal, 38(4), 975–996.

Mishra, S., & Suar, D. (2010). Does corporate social responsibility influence firm performance of Indian companies? Journal of Business Ethics, 95(4), 571–601.

Mohan, A. (2001). Corporate citizenship. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 2001(2), 107–117.

Moon, C.-I. (1988). Complex interdependence and transnational lobbying: South Korea in the United States. International Studies Quarterly, 32(1), 67–89.

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242–266.

Nambiar, P., & Chitty, N. (2014). Meaning making by managers: Corporate discourse on environment and sustainability in India. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(3), 493–511.

Narwal, M., & Sharma, T. (2008). Perceptions of corporate social responsibility in India: An empirical study. Journal of Knowledge Globalization, 1(1), 5.

North, D. C. (1996). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University press.

O’Donnell, S. W. (2000). Managing foreign subsidiaries: agents of headquarters, or an interdependent network? Strategic Management Journal, 21(5), 525–548.

Palazzo, G., & Richter, U. (2005). CSR business as usual? The case of the tobacco industry. Journal of Business Ethics, 61(4), 387–401.

Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. (2006). Corporate legitimacy as deliberation: A communicative framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 66(1), 71–88.

Palazzo, G., & Scherer, A. G. (2008). Corporate social responsibility, democracy, and the politicization of the corporation. Academy of Management Review, 33(3), 773–775.

Peng, M. W., & Luo, Y. (2000). Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 486–501.

Peng, M. W., Wang, D. Y. L., & Jiang, Y. (2008). An institution-based view of international business strategy: a focus on emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(5), 920–936.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The external control of organizations : a resource dependence perspective. Stanford: Stanford Business Books.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (2003). The external control of organizations : a resource dependence perspective. Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books.

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., & Lee, J.-Y. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Puck, J. F., Rogers, H., & Mohr, A. T. (2013). Flying under the radar: Foreign firm visibility and the efficacy of political strategies in emerging economies. International Business Review, 22(6), 1021–1033.

Ramamurti, R. (2001). The obsolescing ‘Bargaining Model’? MNC-host developing country relations revisited. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(1), 23–39.

Rao, H. (1994). The social construction of reputation: certification contests, legitimation, and the survival of organizations in the American automobile industry: 1895–1912. Strategic Management Journal, 15(S1), 29–44.

Rasche, A., & Esser, D. (2006). From stakeholder management to stakeholder accountability. Journal of Business Ethics, 65(3), 251–267.

Rehbein, K., & Schuler, D. (2013). Linking corporate community programs and political strategies: A resource-based view. Business & Society (In Press). doi: 10.1177/0007650313478024.

Rettab, B., Brik, A., & Mellahi, K. (2009). A study of management perceptions of the impact of corporate social responsibility on organisational performance in emerging economies: The case of Dubai. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(3), 371–390.

Richter, U. H. (2011). Drivers of change: A multiple-case study on the process of institutionalization of corporate responsibility among three multinational companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2), 261–279.

Rizopoulos, Y. A., & Sergakis, D. E. (2010). MNEs and policy networks: Institutional embeddedness and strategic choice. Journal of World Business, 45(3), 250–256.

Roth, K., & Morrison, A. J. (1990). An empirical analysis of the integration-responsiveness framework in global industries. Journal of International Business Studies, 21(4), 541–564.

Sadrieh, F., & Annavarjula, M. (2005). Firm-specific determinants of corporate lobbying participation and intensity. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(1), 179–202.

Saner, R., Yiu, L., & Søndergaard, M. (2000). Business diplomacy management: A core competency for global companies. Academy of Management Executive, 14(1), 80–92.

Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2007). Toward a political conception of corporate responsibility: Business and society seen from a habermasian perspective. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1096–1120.

Scherer, A. G., & Palazzo, G. (2011). The new political role of business in a globalized world: A review of a new perspective on CSR and its implications for the firm, governance, and democracy. Journal of Management Studies, 48(4), 899–931.

Sengupta, M. (2012). Anna hazare and the idea of Gandhi. The Journal of Asian Studies, 71(03), 593–601. doi:10.1017/S0021911812000617.

Sheng, S., Zhou, K. Z., & Li, J. J. (2011). The effects of business and political ties on firm performance: Evidence from China. Journal of Marketing, 75(1), 1–15.

Shrivastava, H., & Venkateswaran, S. X. (2000). The business of social responsibility: The why, what, and how of corporate social responsibility in India. New Delhi: Books for Change.

Srivastava, R. K., Fahey, L., & Christensen, H. K. (2001). The resource-based view and marketing: The role of market-based assets in gaining competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 27(6), 777–802.

Strike, V. M., Gao, J., & Bansal, P. (2006). Being good while being bad: social responsibility and the international diversification of US firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6), 850–862.

Subramaniam, M., & Watson, S. (2006). How interdependence affects subsidiary performance. Journal of Business Research, 59(8), 916–924.

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571–610.

Sun, P., Mellahi, K., & Thun, E. (2010). The dynamic value of MNE political embeddedness: The case of the Chinese automobile industry. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(7), 1161–1182.

Sykes, G. M., & Matza, D. (1957). Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American Sociological Review, 22(6), 664–670.

Taylor, M. (2000). Cultural variance as a challenge to global public relations: A case study of the Coca-Cola scare in Europe. Public Relations Review, 26(3), 277–293.

Tesler, L. E., & Malone, R. E. (2008). Corporate philanthropy, lobbying, and public health policy. American Journal of Public Health, 98(12), 2123.

Udayasankar, K. (2008). Corporate social responsibility and firm size. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(2), 167–175.

UNCTAD. (2014). Investing in the SDGs: An action plan world investment report 2014 (Vol. 2014). Geneva: UNCTAD.

Upadhya, C. (2004). A new transnational capitalist class? Capital flows, business networks and entrepreneurs in the Indian software industry. Economic and Political Weekly, 39(48), 5141–5151.

Valente, M., & Crane, A. (2010). Public responsibility and private enterprise in developing countries. California Management Review, 52(3), 52.

Waddock, S., & Smith, N. (2000). Relationships: The real challenge of corporate global citizenship. Business and Society Review, 105(1), 47.

Wang, H., & Qian, C. (2011). Corporate philanthropy and corporate financial performance: The roles of stakeholder response and political access. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1159–1181.

Yang, J. S., & Malone, R. E. (2008). Working to shape what society’s expectations of us should be: Philip Morris’ societal alignment strategy. Tobacco Control, 17(6), 391–398.

Zhao, M. (2012). CSR-based political legitimacy strategy: Managing the state by doing good in China and Russia. Journal of Business Ethics, 111(4), 439–460.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Survey Items

Appendix: Survey Items

PCSR (Hillman 2003; Hillman and Wan 2005) (α = .80)

About specific activities used by your organization to deal with the Indian government

How important have the following activities been for you to deal with government officials in this country over the past year? (1: not at all important, up to 5: very important)

-

1.

Public relations advertising in the media on specific issues related to policy

-

2.

Mobilizing grassroots political programs (such as organizing demonstrations, signature campaigns, using social networks to organize communities, etc.)

-

3.

Forming coalitions with other organizations not in your sectoral trade associations (such as environmental groups and social groups)

Resource Criticality (Srivastava et al. 2001)

About the importance of various resources available in India to your organization.

How important are the following for the day-to-day operations of your business? (1: not at all important, up to 5: very important).

Tangible (α = .826)

-

1.

Land (e.g., for construction or agri-businesses)

-

2.

Up-to-date production machinery/equipment

-

3.

Unskilled workers (low-cost, minimum wage labor)

-

4.

Raw materials (natural resources)

Intangible (α = .701)

-

1.

Specifically owned patented technology/technological know-how

-

2.

Highly skilled employees (engineers, scientists, doctors, accountants, consultants, etc.)

-

3.

Reputation of your company (e.g., product brand names or company name)

International Interdependence (O’Donnell 2000; Subramaniam and Watson 2006) (α = .71)

About the interdependence of your organization with headquarters and other foreign subsidiaries

To what extent do you disagree/agree with the following statements (1: strongly disagree, up to 5: strongly agree)

-

1.

The activities of headquarters influence our outcomes.

-

2.

Our activities influence the outcomes of headquarters.

-

3.

The activities of other foreign subsidiaries influence our outcomes.

-

4.

Our activities influence the outcomes of other foreign subsidiaries.

Managerial Ties (Peng and Luo 2000; Sheng et al. 2011)

About your organization’s managerial connections

To what extent do you disagree/agree with the following statements? (1: strongly disagree, up to 5: strongly agree)

We have maintained good personal relationships with:

Political Ties (α = .88)

-

1.

Officials at various levels of government

-

2.

Regulatory and supporting organizations such as tax bureaus, state banks, and commercial administration bureaus

Business Ties (α = .61)

-

1.

Supplier firms in India

-

2.

Customer firms in India

-

3.

Competitor firms in India

-

4.

Marketing-based collaborators in India (e.g., distributors, advertisers, etc.)

-

5.