Abstract

This study provides an attributional perspective to the ethical leadership literature by examining the role of attributed altruistic motives and perceptions of organizational politics in a moderated mediation model. Path analytic tests from two field studies were used for analyses. The results support our hypotheses that attributed altruistic motives would mediate the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and affective organizational commitment. Moreover, the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and attributed altruistic motives was stronger when perceptions of organizational politics were high but weaker when these perceptions were low. The study concludes with a discussion of future research implications as well as managerial implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although discussion of the ethical dimension of leadership can be traced back to Barnard (1938), Burns (1978), Avolio et al. (1999), and Bass and Steidlmeier (1999), ethical leadership is relatively new as an independent construct with two pillars: a moral person and a moral manager. Brown et al. (2005) defined ethical leadership as the “demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to employees through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (p. 120). This definition suggests that ethical leadership, as normative appropriate conduct, can be observed across multiple types of organizations, cultures, and industries. To be seen as ethical leaders, supervisors use social power in a manner that combines the role of a moral person and a moral manager. A moral person conceives of ethical leadership as characterized by moral traits, right behaviors, and principled decision-making, whereas a moral manager transfers these ethical characteristics to subordinates by using role modeling, rewards and discipline, and communication (Treviño et al. 2000).

Evidence of the beneficial effects of ethical leadership is abundant, including enhanced employee performance, voice, citizenship behavior, moral judgment, organizational commitment, and job satisfaction (e.g., Kacmar et al. 2011; Mayer et al. 2012; Neubert et al. 2009; Piccolo et al. 2010; Steinbauer et al. 2014). However, researchers have only started to examine the cognitive-effect processes of how and why these effects take place. As the behavioral component of ethical leadership involves role modeling and contingent rewards, social learning theory (Bandura 1986) has been the conventional framework to study how ethical leadership influences subordinates (e.g., Brown et al. 2005; Kacmar et al. 2013; Taylor & Pattie 2014). Within the framework of social learning theory, ethical leadership influences employee attitudes and behaviors by means of role modeling, so learning by vicarious experience is the mechanism that carries the effects of ethical leadership on to individual outcomes. Supervisors who display ethical leadership influence subordinate outcomes as the subordinates observe ethical leadership behaviors and their consequences in the organization. According to Wood and Bandura (1989), two elements are required for role modeling to be effective: model attractiveness (i.e., how credible and legitimate ethical leaders are) and behavior attractiveness (i.e., whether ethical behaviors are prosocial and lead to positive consequences). A perspective which is critical to this inquiry by Brown et al. (2005) proposes that for leaders to be perceived as attractive role models in this framework, their behaviors must suggest altruistic motives. However, social learning theory does not make clear what can influence subordinates’ attributions about their supervisors’ motives and further, how these attributions influence their attitudes and behaviors.

By contrast, attribution theory (Heider 1958; Kelley 1972a, b; Kelley & Michela 1980) explains how attributions of motives are made and how they influence attitudes and behaviors. The attributional perspective of leadership is based on the premise that subordinates have an innate desire to understand the causes of observed leadership, and that these causes, in turn, affect how subordinates react to leadership practices (Dasborough & Ashkanasy 2002; Kelley & Michela 1980; Martinko 1995; Martinko & Gardner 1987; Martinko et al. 2007). Therefore, attribution theory offers a complementary perspective to the social learning framework of ethical leadership by explaining how subordinates draw conclusions regarding whether or not their supervisors’ ethical leadership behaviors are altruistic in motive. This perspective also describes how the attributed motives behind ethical leadership influence subordinates’ attitudes and behaviors. As such, the purpose of this study is to extend the ethical leadership literature by proposing an attributional process that helps explain the influence of ethical leadership on subordinate outcomes. Further, we will examine perceptions of organizational politics (POPs; Ferris & Kacmar 1992) as a situational factor that influences subordinate attributions of ethical leadership behaviors. Kelley and his associates posited that individuals have certain expectations for behaviors in a particular situation and that these expectations may influence individuals’ dispositional or situational attributions of the observed behaviors (Kelley & Michela 1980). As a measure of organizational contexts, POPs are defined as felt illegitimate and self-serving behaviors engaged in with the intention to pursue individual agendas without regard to their effect on organizational goals/interests (Ferris & Kacmar 1992). POPs may influence subordinates’ attributions of observed ethical leadership from supervisors. Thus, our model depicts how observations of ethical leadership and organizational politics jointly produce informational cues that influence subordinate attributions, which in turn influence their affective outcomes directed toward organizations.

Our model examines subordinates’ attribution of supervisor motives (Allen & Rush 1998; Dasborough & Ashkanasy 2002) as the mediating mechanism and their perceptions of organizational politics as the moderator in order to enhance the predictive validity of perceived ethical leadership. We focus on one important outcome: affective organizational commitment. Affective organizational commitment refers to subordinates’ emotional attachment to, identification with, and involvement with organizations (Allen & Meyer 1996). This outcome was selected as an appropriate criterion variable in the current study for three reasons. First, affective commitment is theoretically anticipated to be related to the process of ethical leadership, POPs, and altruistic attributions articulated here (Brown & Treviño 2006). Second, affective commitment is argued to be theoretically unique to the other forms of commitment in that it is more influenced by leadership behavior and attribution (Bono & Judge 2003) and thus appropriate for this study. Third, empirical tests indicate that affective commitment is a robust predictor of important organizational outcomes such as turnover (Griffeth et al. 2000; Meyer et al. 2002) and performance above and beyond other forms of commitment (Becker & Kernan 2003; Riketta 2002).

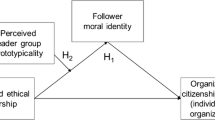

The development of our model makes two important contributions to the ethical leadership literature. First, our study responds to scholars’ call for more use of attribution theory in organizational science by offering an attributional perspective of how ethical leadership influences subordinates (Harvey et al. 2014a, b; Martinko et al. 2011a, b). Specifically, it presents the attributional process as the mediating mechanism through which perceived ethical leadership relates to its outcomes among subordinates. There has been growing recognition that employee attributions are likely to play a critical role in the leadership process (e.g., Dasborough & Ashkanasy 2002; Martinko et al. 2007; Martinko & Gardner 1987; Lord & Emrich 2001; Martinko 1995), and therefore, our research supplements the social learning framework of ethical leadership in the current ethical leadership literature. Second, it integrates attributional principles (Kelley & Michela 1980) to the leadership attribution process to explain how organizational context (i.e., politics) influences subordinates’ attributions of ethical leadership. This integration corresponds to the call for more research on the interplay between attribution and contextual factors in organizations and culture that may affect leadership processes (e.g., Avolio et al. 2009; Dasborough & Ashkanasy 2002) (Fig. 1).

Theory and Hypothesis Development

Attribution Theory as a Supplemental Perspective of Perceived Ethical Leadership

The Mediating Attribution Process

Attribution theory has been useful for understanding how individuals make causal explanations of perceived behaviors. Central to the theory is the human need to construct causal explanations for observed behaviors in order to make sense of and control the environment (Heider 1958). According to this theory, individuals try to identify the possible reasons for observed behaviors by collecting information which might explain these behaviors. These attributions enable these individuals to understand others’ behaviors and to determine how they would act toward these observed behaviors. Leadership literature, for instance, has documented the importance of supervisors’ causal attributions of subordinate behaviors for the effectiveness of leading (e.g., Allen & Rush 1998; Dienesch & Liden 1986; Green & Mitchell 1979; Mitchell & Wood 1980). Given the codependent supervisor–subordinate relationship, subordinates are also motivated to search for causal explanations of supervisors’ behaviors in the leading process (Dasborough & Ashkanasy 2002; Kelley & Michela 1980). Indeed, prior research has demonstrated that leadership effectiveness can be significantly affected by subordinates’ attribution of their supervisors’ motives for enacting certain behaviors (e.g., Bass & Steidlmeier 1999; Martinko & Gardner 1987; Sue-Chan et al. 2011). For example, Sue-Chan et al. (2011) found that supervisors whose leadership behaviors were believed to have a sincere organizational focus rather than a manipulative self-serving focus tend to influence subordinates more.

Thus, in the context of ethical leadership, supervisors’ motives and intentions can be critical to how their ethical leadership behaviors are perceived. As mentioned earlier, the social learning framework suggests that ethical leadership influences subordinates through role modeling (Brown et al. 2005). For role modeling to be successful, both the models (i.e., supervisors) and their behaviors must be attractive: the models must be perceived as credible and legitimate, and the behaviors must be prosocial and lead to positive consequences (Wood & Bandura 1989). If the models or their behaviors are not considered credible, legitimate, or prosocial, the role modeling process will not be effective, if it takes place at all. However, considering the pervasiveness of cynicism (Johnson 2005) and the possibility that supervisors with enough political skill or self-presentation capacity project a positive self-image by engaging in desired leadership behaviors (Gardner & Cleavenger 1998; Harvey et al. 2014a, b; Sosik et al. 2002), subordinates may attribute supervisors’ ethical leadership behaviors to self-serving impression management strategies and be suspicious of their real motives (Bass & Steidlmeier 1999; Harvey et al. 2006). Hence, the missing link in the social learning framework is the way by which subordinates determine whether or not their supervisors’ ethical leadership is attractive and driven by altruistic motives, and how these conclusions impact their attitudes and behaviors.

Altruistic motives indicate a sincere organizational focus. Elements of altruistic motives typically include personal values, the desire to benefit others, commitment, and loyalty to the organization (Allen & Rush 1998). To date, research examining altruistic motives in organizational contexts has mostly focused on subordinates’ extra-role behaviors. Prior studies have found that when subordinates’ extra-role behaviors are labeled with altruistic or prosocial motives by raters, they are more likely to receive better evaluations and personal outcomes (e.g., Allen & Rush 1998; Eastman 1994; Whiting et al. 2012). However, an attributional perspective of ethical leadership has not been explicitly examined in prior research. As suggested by Batson & Shaw (1991), subordinates should be able to identify the altruistic motives behind supervisor behaviors based upon their frequent interactions with their supervisor across situations. When subordinates attribute their supervisor’s ethical leadership behaviors to altruistic motives, they should be less likely to hold cynical attitudes toward the supervisor’s ethical pronouncements and acknowledge the authenticity of ethical leadership, which ultimately lead to an optimal influence of ethical leadership on subordinates (Brown et al. 2005; Zhu et al. 2004).

In the current study, we argue that ethical leadership can be associated with subordinates’ attribution of altruistic motives (Brown et al. 2005; Cha & Edmondson 2006; Dasborough & Ashkanasy 2002). As Resick and associates (2006) suggest, ethical leadership is characterized by altruism, which refers to engaging in actions with the intention of helping others without expecting external rewards. In addition, because ethical leaders care about their reputation among subordinates (Treviño et al. 2000), they should be aware that subordinates make inferences based upon their actions. As such, in addition to being a moral person, an ethical leader engages in ethical conduct that is consistent and visible to subordinates. He or she communicates regularly and persuasively with subordinates about ethical standards, principles, and values, and uses a reward system consistently to encourage professional behaviors. The consistency of the supervisor’s ethical conduct provides a foundation to facilitate altruistic attributions of ethical leadership behaviors (Brown et al. 2005). Although we believe that perceived ethical leadership is related to attributed altruistic motives, we also realize that these constructs are conceptually distinct from each other. One reason is that perceived ethical leadership focuses on subordinates’ observation of their leader’s actions, whereas attributed altruistic motives focus on the causal explanations of these observed leader behaviors (Dasborough & Ashkanasy 2002). In addition, Brown and Treviño (2006) suggest that altruism is not a function of ethical leadership any more than of any other leadership styles and that altruism can be found in authentic leadership, spiritual leadership, and transformational leadership when these leadership styles display behaviors such as concern for others. This is also in line with Ferris et al. (1995) notion that attributions of leader motives can be a product of a particular leadership style and have a strong influence on subordinates’ interpretation of this leadership style. Based on this reasoning, we view perceived ethical leadership and attributed altruistic motive as two conceptually distinct constructs. As such, we propose.

Hypothesis 1

Perceived ethical leadership will be positively related to attributed altruistic motives.

Further, we aim to establish a positive relationship between attributed altruistic motives and affective organizational commitment. As attribution theory (Kelley 1973) suggests, positive affective outcomes are more likely when observed behaviors are attributed to altruistic motives.

Affective organizational commitment refers to employees’ relative strength of identification with and involvement in a particular organization (Allen & Meyer 1990, 1996). Strengthening affective organizational commitment has been widely recognized as one effective way to address the challenges of weakened employee attachments to organizations in today’s changing workforce environment, which is characterized by enhanced mobility, autonomy, and independence (Cascio 2003; Grant et al. 2008). Meta-analysis studies have demonstrated that commitment is positively correlated with multiple types of employee performance and job satisfaction while negatively related to absenteeism and turnover (Cohen 1993; Griffeth et al. 2000; Jaramillo et al. 2005; Meyer et al. 2002; Podsakoff et al. 2007; Riketta 2002). In light of these benefits of affective organizational commitment, it is theoretically and practically important to understand how ethical leadership and attributed altruistic motives underlying such a leadership style may foster it.

Specifically, we argue that subordinates’ attribution of supervisor motives is related to affective organizational commitment, which forms as subordinates align their attitudes with these attributions during interactions with their supervisors, who are always considered to be representatives of the organization (Eisenberger et al. 2010). As suggested by many scholars, the nature of employee relationships with supervisors in the organization is often the primary mechanism through which employees experience the employment relationship (e.g., Kinicki & Vecchio 1994; Pearce 2001; Rousseau 2004). Thus, subordinates are expected to relate to an organization through the particular relationships that exist between subordinates and supervisors. In other words, subordinates’ affective organizational commitment can develop after interactions with their supervisor. Attributed altruistic motives are other directed, meaning that supervisors’ display of ethical leadership is based on personal values and directed toward the good of their subordinates, the organization, and/or other stakeholders (Allen & Rush 1998). The attribution of altruistic motives, therefore, facilitates the sense-making process and enhances the conclusion that supervisors displaying ethical leadership are concerned about employee needs and perspectives. Such social cues typically engender positive effect toward organization given the favorableness of their exchange relationship with supervisor (Brockner 2002; Eisenberger et al. 2004; Lamertz 2002). Thus, we hypothesize that.

Hypothesis 2

Attributed altruistic motives will be positively related to subordinates’ affective organizational commitment.

As such, the model in this study is focused on subordinates’ attributed altruistic motives of perceived ethical leadership and their attitudinal responses to these attributed motives. The model asserts that subordinates’ attribution of ethical leadership to altruistic motives may serve as a pathway linking ethical leadership and subordinates’ affective organizational commitment. In other words, when subordinates attribute ethical leadership to altruistic motives, they should respond more positively to such motives. However, extant research suggests that ethical leadership has a direct effect on subordinates’ affective commitment (e.g., Trevino 1998; Treviño et al. 2000; Brown & Treviño 2006; Treviño et al. 2003). Researchers have also noted that there are other pathways that link ethical leadership to affective commitment (Hansen et al. 2013; Neubert et al. 2009; Neubert et al. 2013). Based on this line of reasoning and our discussion in the previous sections, we expect.

Hypothesis 3

Attributed altruistic motives will partially mediate the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and affective organizational commitment.

The Moderating Attribution Principles

Subordinates’ attributions of a particular leadership style can be subjective in nature and impacted by situational influences (Lord & Smith 1983). For instance, as suggested by attribution theory (Kelley 1972a, b; Kelley & Michela 1980), individuals approach most attributional problems with beliefs about the causes involved. These beliefs are associated with expectations about the consensus behaviors in a given situation (i.e., how most people would act in the same circumstance). Observed behaviors that meet these expectations tend to be attributed to the situations, whereas observed behaviors that depart from these expectations tend to be attributed to the actors. Two attributional principles are generally used to address this notion: the augmentation principle and discounting principle. The augmentation principle (Kelley 1972a; Kelley & Michela 1980) operates when individuals attribute the observed behaviors to the actors because these behaviors are not in accordance with situational cues. That is, behaviors that “go against the grain” are perceived as more revealing of personal attributes such as altruistic motives. In contrast, the discounting principle (Kelley 1972a; Kelley & Michela 1980) takes effect when individuals attribute the observed behaviors to the situation when these behaviors conform to the situational norms. In other words, the expected behaviors are discounted as an indication of the actors’ personal attributes because they may plausibly be caused by situational pressures.

We argue in the current study that both discounting and augmentation principles may be at play in determining how ethical leadership influences affective organizational commitment through an attribution mechanism. In other words, subordinates’ attribution of altruistic motives toward supervisors’ ethical leadership behaviors can be a product of a situationally bound attributional process. The degree to which subordinates attribute ethical leadership behaviors to altruistic motives is determined by the interaction between situational factors and the subordinates’ attributional process. One situational factor that is of particular interest to this study is organizational politics, which emits strong cues against ethical leadership behaviors. As Morgan (2006, p. 150) describes it, political organizations encourage individuals to advance specific interests through forms of “wheeling and dealing.” The impact of politics on individuals, however, is filtered through individuals’ perceptions of organizational politics (POPs), described as individuals’ perceptions of the existence of pervasive political activities of others, such as building subgroups, hiding information, and backstabbing (e.g., Chang et al. 2009; Kacmar et al. 2013; Rosen & Hochwarter 2014). Thus POPs, as perceptual evaluations regarding the politics of daily organizational life, have been indicators of the degree to which politics are pervasive in an organization (Harris et al. 2007).

In the attributional process, subordinates tend to identify the most plausible cause of ethical leadership behaviors. Attributions are often made about whether their supervisors are personally responsible for ethical leadership behaviors or situational factors beyond the control of the supervisors are causally related to ethical leadership behaviors (Green & Mitchell 1979; Kelley 1972a; Kelley 1973). As noted above, subordinates’ attributional process can be governed by the augmentation principle and the discounting principle. Specifically, according to the augmentation principle (Kelley 1972b; Kelley & Michela 1980), in a highly political environment, supervisors’ altruistic motives would be the salient cause of ethical leadership, because in environments where favoritism is likely to prevail, the cues for ethical leadership are likely to be weak if not negative, and consensus behaviors (i.e., how most people would act in the same circumstance) are less likely to be ethical leadership. As Pilkonis’ (1977) experiments suggest, subordinates would be more likely to attribute ethical leadership behaviors to altruistic motives when ethical leadership is not part of the consensus behaviors or contradicts the subordinates’ expectations of the consensus behaviors in a political environment. Therefore, when POPs are high, the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and attribution of altruistic motives becomes stronger because subordinates tend to attribute ethical leadership behaviors to the supervisor’s altruistic motives. In other words, when subordinates observe their supervisors engaging in ethical leadership in a political environment where ethical practices are not typically expected or encouraged, they should have the most positive attributions about their supervisors (i.e., highest attributed altruistic motives) because these supervisors are seen as authentic and going against the grain; however, when subordinates do not perceive ethical leadership, they will have the least positive attributions about their supervisors (i.e., lowest attributed altruistic motives).

However, in environments that are not overrun by politics, normative behaviors such as ethical leadership are likely to be part of consensus behaviors. When supervisors’ behaviors are conformant to situational norms, these behaviors are more reflective of situational demands rather than the supervisors’ altruistic motives. This is the effect of the discounting principle (Kelley 1972b; Kelley & Michela 1980), which suggests that a less political environment discounts ethical leadership behaviors as indicators of supervisors’ personal attributes and makes situational norms the salient cause. Therefore, when POPs are low, the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and attribution of altruistic motives becomes weaker. In other words, with less politics, ethical leadership would be perceived as part of consensus behaviors for the supervisors (Pilkonis 1977). When subordinates witness ethical leadership, they should tend to attribute it to the situational norm rather than to the supervisor’s altruistic motives. Thus, in a less political environment, subordinates may perceive supervisors’ engagement in ethical leadership as a response to contextual demands and attribute the behaviors to the less political environment and not necessarily their supervisors’ altruistic motives. Therefore,

Hypothesis 4

POPs will moderate the strength of the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and attributed altruistic motives such that the relationship will be stronger when POPs are high rather than low.

Integration of the previous arguments leads to a moderated indirect-effect model in which attributed altruistic motives mediate the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and affective organizational commitment, and this mediation effect is stronger when organizational politics are pervasive. As such, we propose.

Hypothesis 5

POPs will moderate the strength of the mediated relationship between perceived ethical leadership and affective organizational commitment via attributed altruistic motives, such that the mediated relationship will be stronger when POPs are high rather than low.

Methods

Samples & Procedures

Data in Sample 1 and Sample 2 were taken from a larger leadership study conducted in China. A Chinese context was determined to be an appropriate test of the hypothesized model for the following reasons. First, the importance of ethical leadership is deeply rooted in Confucian culture, which still influences current Chinese society (Chen & Farh 2009). Researchers have found empirical evidence that ethical leadership leads to many positive employee outcomes in current Chinese organizations such as job performance, psychological empowerment, and creative behaviors (e.g., Li et al. 2012; Liu et al. 2013; Tu & Lu 2013). Second, Chinese organizations as a whole include a stronger collectivistic culture than firms based in the United States (Chen & Farh 2009). Thus, perception of politics is influenced by culture, and individuals going against normative collective behaviors will be more salient to the observing subordinates, creating an environment to better test such relationships. If the sample was highly individualistic, managers taking action contrary to normative behavior would be less salient as it would be anticipated to be more common. Data in both samples were collected at two points in time to reduce effects of common method and source bias. A time 1 survey provided independent variables and a survey at time 2, administered 4 weeks later, provided the dependent variable. Surveys were assigned random numbers when participants took survey 1, and those IDs were given to each respondent in order to match the data over Time 1 and Time 2. Sample 1 was designed to maximize external validity by a heterogeneous sample of employees, whereas sample 2 was designed to maximize internal validity by focusing on a single firm.

Sample 1 consisted of part-time MBA students from a university in Central China. These part-time MBA students were full-time employees from various organizations and only had classes on weekends. The voluntary nature of the study was stressed, and confidentiality was assured. A research assistant distributed 200 questionnaires at Time 1 and Time 2 and collected the surveys after they were completed. A total of 189 matched and usable surveys were gathered. All participants in this sample were Chinese citizens and 58.7 % were male, with an average age of 33.2, ranging from 22 to 55. Average tenure with their respective organizations was 5.8 years, and average tenure with their current supervisor was 2.9 years. For position level, 1.1 % of the respondents were from high-level management teams, 60.3 % were from middle-level management teams, and 38.6 % were non-management employees. For organization type, a majority of the respondents (71.5 %) were from public or state-owned companies, and only 18 % were from private or foreign-invested companies.

In Sample 2, two separate self-report questionnaires were administered to 220 employees in four different manufacturing departments at an auto-maker in Northern China. Letters were attached to the surveys, written by the director of the agency, requesting employees’ participation. Both the employer and employees were assured anonymity. At both Time 1 and Time 2, each employee was given about 30 min to fill out the survey during a lunch break. One of our researchers collected the surveys immediately after they were completed. A total of 199 matched and usable surveys were gathered. All participants in our sample were Chinese citizens and 78.9 % were male, with an average age of 25, ranging from 20 to 37, and 74.9 % had associate degrees or above. Tenure with their organizations ranged from 1 to 8 years with a mean of 2 years, and tenure with their current supervisor ranged from 0.5 to 5 years with a mean of 1.8 years. For position level, almost all of the respondents (99 %) were entry-level employees.

Measures

As all measures used in this study were originally composed in English, they were first translated into Chinese, then back translated to English by a panel of bilingual experts, following the translation and back translation procedures advocated by Brislin (1980). Any resulting discrepancies were discussed and resolved. All measures employed a 5-point Likert-type scale, anchored at 1 for “strongly disagree” and 5 for “strongly agree.”

Perceived ethical leadership was measured using a 10-item scale developed by Brown et al. (2005) to measure perceived ethical behaviors of one’s supervisor. Sample items were “My supervisor conducts his or her personal life in an ethical manner” and “My supervisor disciplines employees who violate ethical standards.” Cronbach’s alphas in the two samples were 0.80 for Sample 1 and 0.91 for Sample 2. While ethical leadership was developed in the United States, normative ethical behavior exists across cultures, and no items in the ethical leadership scale were inconsistent with ethical Chinese values. Further, previous research has demonstrated the ethical leadership scale applied in China (e.g., Liu et al. 2013; Tu & Lu 2013; Walumbwa et al. 2011).

Attributed altruistic motives were measured with a 6-item scale developed by Allen and Rush (1998). We used the scale to measures participants’ general perception of motives toward supervisor’s behaviors. In the survey, items for attributed altruistic motives were placed immediately after the items used to measure supervisor behaviors, following the instruction “Please indicate the extent to which you think that each of the following items may be the motive of a supervisor’s actions when he/she exhibits such leadership behaviors in the above section.” Sample items are “due to personal values of right or wrong” and “due to involvement in his/her work.” Cronbach’s alpha was 0.79 for Sample 1 and 0.79 for Sample 2.

Perceptions of organizational politics (POPs) were measured with a 6-item scale developed by Kacmar and Ferris (1991). This scale measured the degree of politics that an employee felt in his/her working environment. Sample items were “Favoritism not merit gets people ahead” and “Employees build themselves up by tearing others down.” The reliability estimates for this scale were 0.87 for Sample 1 and 0.85 for Sample 2.

Affective organizational commitment was measured with a 6-item scale taken from Allen and Meyer (1996). This construct is an appropriate criterion for this study due to its breadth in management research. Specifically, affective commitment is not just a positive attitude to develop in organizations. Example items for this instrument are “I feel emotionally attached to this organization” and “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career with this organization.” The use of this scale has been validated in the Chinese context (Chen & Francesco 2003; Hui et al. 2004). The Cronbach’s alphas for this scale were 0.83 for Sample 1 and 0.75 for Sample 2.

Analysis

Before hypothesis testing, structural equation modeling (SEM) using LISREL 8.7 with maximum likelihood estimation was conducted to test discriminant validity. The original four-factor measurement model, in which the correlations were estimated, was compared with a series of models in which each had the correlation of one pair of constructs constrained to be 1.00. The normal theory weighted least squares Chi square index, the comparative fit index (CFI), the normed fit index (NFI), the incremental fit index (IFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used to assess the model fit, and the differences in Chi squares were used to compare models (Bollen 1989; Joreskog and Sorbom 1999).

By following Edwards and Lambert’s (2007) approach (see Tepper et al. 2008), the moderated mediation model in the current study was analyzed combining moderated regression procedures with mediation testing in a path analytic framework (MacKinnon et al. 2002; Shrout & Bolger 2002). More specially, this framework addressed problems with Baron and Kenny’s (1986) causal steps approach and allowed us to test the hypothesized models against alternative, nested models.

Results

Descriptive statistics, correlations, and reliability coefficient for the variables of interest are presented in Table 1 (for Sample 1) and Table 2 (for Sample 2). In Sample 1, the fit statistics for the four-factor measurement model are acceptable (χ2/df = 2.40, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.89, NFI = 0.88, IFI = 0.89, RMSEA = 0.09). In Sample 2, the data fit the four-factor measurement model very well (χ2/df = 2.18, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.95, NFI = 0.90, IFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.07). Kline (2005) recommends evaluating the χ2 result in relation to the degrees of freedom (df), and a χ2:df value of less than 3:1 suggests good model fit. In order to ensure discriminant validity of the ethical leadership instrument and the altruistic motive items, we conducted a Chi square difference test of significance between the anticipated model (two factors: ethical leadership and altruistic motive) and a combined single-factor model with both ethical leadership and altruistic motives items loading on a single factor. Results from both samples suggest the model fit significantly better with a two-factor model over a single-factor model (Sample 1: ΔX 2 = 57, Δdf = 1, p < 0.001 and Sample 2: ΔX 2 = 64, Δdf = 1, p < 0.001). Overall, this test provides support that ethical leadership and altruistic motive were not collinear but distinct factors for participants in these samples. In addition to performing CFA, we also looked more closely at the perceived ethical leadership and attributed altruistic motives items. Because we observed the perceived ethical leadership item “my supervisor has the best interests in mind” may reflect subordinates’ attributed altruistic motives, we removed this item from the original perceived ethical leadership scale. However, removal of the item did not produce a substantive difference in the results. As such, we retained the complete ethical leadership scale for this study.

Two models were tested in our study: (1) the hypothesized first-stage moderated mediation model in which POPs moderated the indirect effect of perceived ethical leadership on affective commitment and (2) the mediation model in which the moderation of the indirect effect was not specified. Using Edwards and Lambert’s (2007) approach, we began by estimating two regression equations. First, the effects of perceived ethical leadership (EL), POPs, and their interaction variable (EL × POPs) on attributed altruistic motive were estimated. The second equation estimated the direct effects of perceived ethical leadership and attributed altruistic motive (with POPs included) on affective commitment. The total effect of ethical leadership on affective commitment, which consisted of a direct effect and an indirect effect that varied over POPs, was also captured. According to Tepper et al.’s (2008) suggestion, due to the non-normal distribution of the interaction, bootstrapped estimates with 10,000 samples were used to construct bias-corrected confidence intervals for all significance tests reported in this study.

Table 3 (for Sample 1) and Table 4 (for Sample 2) show the regression results for the effects of ethical leadership, POPs, and the interaction variable (EL × POPs) on attributed altruistic motive and affective commitment. Omnibus model testing was conducted in this study. Specifically, we compared the hypothesized first-stage moderated mediation model to a mediation model that does not specify moderation of the indirect effect. Then we computed generalized R 2 values for the target model and the comparison model and compared them using the Q statistic (Pedhauzer 1982). In Sample 1, for the Hypothesized Model, \(R_{\text{G}}^{2}\) was 0.83; for the Mediation Model, \(R_{\text{G}}^{2}\) was 0.81. In Sample 2, for the Hypothesized Model, \(R_{\text{G}}^{2}\) was 0.65; for the Mediation Model, \(R_{\text{G}}^{2}\) was 0.64. The generalized R 2 values for each model may be compared with a Q statistic. For Sample 1, Q1 was 0.89. Similarly, for Sample 2, Q2 was 0.97. The Q statistic had an upper bound of 1 (which means the two models did not differ). We tested the significance of Q using the W statistic, which is Chi square distributed with the degrees of freedom. The more restricted model (the Hypothesized Model) was compared to the less restricted model (the Mediation Model). In Sample 1, comparisons among the two models suggested that the generalized variance explained by the Hypothesized Model (\(R_{\text{G}}^{2}\) = 0.83) was different from the variance explained by the Mediation Model (\(R_{\text{G}}^{2}\) = 0.81; Q = 0.89, W = 21.531, d = 1, p < 0.01). In Sample 2, comparisons among the two models suggested that the generalized variance explained by the Hypothesized Model (\(R_{\text{G}}^{2}\) = 0.65) was different from the variance explained by the Mediation Model (\(R_{\text{G}}^{2}\) = 0.64; Q = 0.97, W = 6.24, d = 1, p < 0.05). Hence, the predictive power of the moderated mediation model was superior to that of the mediation model in both samples.

We then examined the path estimates associated with the hypotheses. The direct, indirect, and total effects of ethical leadership on affective commitment at lower and higher levels of POPs are reported in Table 5 (for Sample 1) and Table 6 (for Sample 2). For Sample 1, as shown in Table 3 and Table 5, ethical leadership was positively related to attributed altruistic motives (b = 0.83, p < 0.01), supporting hypothesis 1. Attributed altruistic motives was also positively related to affective commitment (b = 0.28, p < 0.01), supporting hypothesis 2. Ethical leadership was positively related to affective commitment (b = 0.69, p < 0.01). When attributed altruistic motive was introduced, there was still a significant ethical leadership-affective commitment relationship, which supports hypothesis 3 and suggests that attributed altruistic motive only served as a partial mediator. The relationship between ethical leadership and attributed altruistic motive became stronger (p = 1.20, p < 0.01) when POPs were high. The difference between high POPs and low POPs was significant (p = 0.75, p < 0.01), supporting hypothesis 4. POPs also moderated the strength of the mediated relationship between ethical leadership and affective commitment via attributed altruistic motive, such that the mediated relationship became stronger when POPs was high (p = 0.33, p < 0.01) rather than low (p = 0.12, p < 0.01), with a significant difference (p = 0.21, p < 0.01). Therefore, hypothesis 5 was supported.

For Sample 2, as shown in Tables 4 and 6, ethical leadership was related to attributed altruistic motive (b = 0.54, p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis 1. Attributed altruistic motive was positively related to affective commitment (b = 0.17, p < 0.1), supporting hypothesis 2. Ethical leadership was positively related to affective commitment (b = 0.39, p < 0.001). When attributed altruistic motive was introduced, there was also a significant ethical leadership-affective commitment relationship, which supported hypothesis 3. Furthermore, the relationship between ethical leadership and perceived altruistic motive became stronger (p = 0.72, p < 0.01) when POPs were high. The difference between high POPs and low POPs was significant (p = 0.36, p < 0.05). Thus, hypothesis 4 was supported. POPs also moderated the strength of the mediated relationship between ethical leadership and affective commitment via attributed altruistic motive, such that the mediated relationship became stronger when POPs was high (p = 0.12, p < 0.05) rather than low (p = 0.06, p < 0.05), with a significant difference (p = 0.06, p < 0.05). Thus, hypothesis 5 was supported. Therefore, all the hypotheses were supported in both samples.

Figures 2 and 3 show the plots of the moderating effects of POPs on the relationship between ethical leadership and attributed altruistic motive. Before we interpreted the plots, we conducted a series of simple slope tests that examined whether the slopes of the lines in the plots (see Figs. 2, 3) were significant; that is, we tested if the independent variable (ethical leadership) was significantly related to the mediator (attributed altruistic motive) on the two levels (high vs. low) of POPs in each sample. A simple slope test (Aiken & West 1991) determines if the slope of a line differs from zero with a t-statistic. If the t test is significant, then the slope is significantly different from zero and vice versa. Results of our simple slope tests indicated that all four lines in the plots had a slope that significantly differed from zero. In Sample 1, ethical leadership was significantly related to attributed altruistic motive when POPs were high (b = 0.84, t = 11.50, p < 0.001) and low (b = 0.36, t = 4.68, p < 0.001). The same was true for Sample 2, with b = 0.84, t = 13.86, p < 0.001 for high POPs and b = 0.50, t = 6.23, p < 0.001 for low POPs.

It should be noted that when we examined the slopes, we noticed subtle differences between the two plots. Therefore, we conducted a few independent-sample t tests on all four variables in our model. These t tests compared the sample means on each variable, and the tests indicated that the two samples were significantly different on that variable. As the test results suggested, the two samples were not different in ethical leadership or in attributed altruistic motive, but they were different in POPs and affective commitment. In other words, the subtle between-sample differences were not attributable to the subjects from the two samples but may be explained by the different levels of POPs between the two samples. This result is in fact, expected, because subjects in Sample 1 did not work for the same employer, whereas subjects in Sample 2 all worked for the same company in the same location. It is reasonable, then, that the subjects from the two samples, on average, should have different perceptions of organizational politics.

Discussion

In Brown and Treviño’s (2006) review of ethical leadership, they proposed (Proposition 16) that ethical leadership would be positively related to employee’s organizational commitment. However, since then very few studies have tested mechanisms related to how and why this relationship exists or further, the contextual boundary conditions of the relationship (see Neubert et al. 2009, 2013 and Hansen et al. 2013 for possible exceptions). To supplement and enrich the research on the understanding of ethical leadership processes, we added an attributional perspective to the social learning framework of ethical leadership by developing and testing a model examining how and under what circumstances perceived ethical leadership is associated with employee affective commitment. The two studies provide convergent evidence for our claim that attributed altruistic motive partially mediates the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and affective organizational commitment. More importantly, we found that subordinates’ perceptions of organizational politics (POPs) moderated the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and attributed altruistic motives in such a manner that when POPs were high, subordinates were more likely to attribute ethical leadership to altruistic motives. The results indicate that compared with subordinates who perceived the environment as less political, subordinates who perceived the environment as more political had the most positive attribution and the highest level of affective organizational commitment when they saw their supervisor’s display of ethical leadership, and these subordinates had the least positive attribution and the lowest level of affective commitment when they found their supervisors to be less ethical. This finding is consistent with Kelley and associate’s (1972a, b, 1973) attribution principles.

Theoretical Contributions

Our study makes important contributions to the ethical leadership literature in two ways. First, we advance the literature by introducing an attributional perspective of how ethical leadership influences subordinate attitude. Unveiling underlying mediating mechanisms is an important way to advance a field of study as it creates the understanding of how and why relationships in organizations exist. Although to some extent social learning theory has been used to address the question of “how” ethical leadership influences subordinate outcomes (Brown et al. 2005; Kacmar et al. 2013; Taylor & Pattie 2014; Walumbwa et al. 2011), we contribute to the literature by suggesting that subordinates manage their interactions with ethical supervisors based on their attributions of the supervisors’ behaviors and configure these attributions into a definition of the situation that directs their attitudes (e.g., affective commitment). Scholars have emphasized that subordinate attributions matter in leader-member interactions (Dasborough & Ashkanasy 2002; Martinko et al. 2011, b; Lord & Emrich 2001; Martinko 1995). We respond to their view by empirically demonstrating attributions of motives as the mediating mechanism that relates perceived ethical leadership to its outcomes among employees. Our findings suggest that, similar to other leadership styles, ethical leadership operates via cognitive processes. Before subordinates respond to their supervisors’ display of ethical leadership with certain attitudes, they discern if the supervisors are acting sincerely for the benefits of the organization, the employees, and/or other stakeholders or acting manipulatively to achieve egocentric personal goals. Attributed altruistic motives of ethical leadership fostered subordinates’ affective organizational commitment. Therefore, an attributional perspective of ethical leadership supplements the social learning framework and helps us to better understand the complex influence mechanisms through which ethical leadership impacts subordinate outcomes.

Second, by integrating Kelley’s (1972a, b, 1973) attribution principles (i.e., augmentation principle and discounting principle) with perceptions of organizational politics (POPs) in the attribution process, our study addresses the important question of “when” ethical leadership matters more, thus contributing to the ethical leadership literature by identifying an organizational context (i.e., politics) as an important factor affecting employees’ attributions of ethical leadership. This integration corresponds to Dasborough and Ashkanasy’s (2002) call for more research on the interplay between attribution and contextual factors. Subordinates’ perceptions of a particular leadership style are subjective in nature and may be distorted by individual biases and environmental influences (e.g., Martinko et al. 2011; Martinko et al. 2012; Yukl et al. 2013). Our study demonstrates that POPs moderated how employees would react to ethical leaders in terms of attributions. Specifically, political environments amplified the relationship between ethical leadership and attributed altruistic motive as the augmentation principle predicted, whereas less political environments suppressed this relationship as the discounting principle postulated (Kelley 1972a, b). Thus, employees were more likely to attribute ethical leadership to an altruistic motive in a political environment because they considered the ethical leadership behaviors they had observed to be authentic and made a dispositional attribution. In contrast, employees tended to perceive ethical leadership as a response to organizational pressures in a less political environment and made a contextual attribution.

Managerial Implications

The results of this study produce meaningful implications for managerial practices. First, our study suggests that managers who enact ethical leadership behaviors would have stronger commitment from subordinates than those who do not, and can therefore improve employee retention. As today’s jobs become more flexible in both time and space, and more importantly, new generations grow more active in managing their careers (Briscoe & Finkelstein 2009), younger workers may be more committed to their careers than to any specific organization (Hughes et al. 2014; King & Bu 2005). On the other hand, evidence also suggests that development of affective organizational commitment is crucial for overall organizational productivity (Jaramillo et al. 2005; Meyer et al. 2002). As such, managers who enact ethical leadership behaviors can be a solution to this conundrum. Second, our results suggest that managers who display ethical leadership should pay attention to how their behaviors are perceived and attributed. For managers who have adopted ethical leadership as their style, it may be beneficial to keep in mind that attributions of leader motives matter to ethical leadership effectiveness. Our findings are consistent with Brown’s (2007) and Dasborough and Ashkanasy (2002) proposition that managers rely on others to accomplish tasks, and therefore, it is important for managers to understand how subordinates evaluate and feel about their ethical leadership. Third, our results suggest that managers should maintain ethical behaviors even when strong external pressures (i.e., politics) and incentives exist to act unethically. Their innate desires to behave with integrity can be observed and attributed to altruistic motives by the employees. In other words, employees in a political environment value managers’ behaviors that “go against the grain” (i.e., ethical leadership) and attribute these behaviors to altruistic motives. Lastly, our study also supports the idea that organizations should create a culture of ethics that reinforces good behaviors at all levels.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

Our study has strengths that should be highlighted. One is the fact that we collected data for the independent variables at Time 1 and the dependent variable at Time 2 to help control common method variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Moreover, two samples from a particular company and from part-time MBA students with diverse backgrounds enhance the generalizability of our results. Another strength lies in the use of Edwards and Lambert’s (2007) approach, which allows us to test the mediating and moderating effects of the variables in the model at the same time. Results from this analysis technique provide better evidence for how these variables are associated with each other in the workplace.

In contrast, there are also limitations to this study that stimulate further research. First, both of the samples used in the current study were collected from China. Some studies suggest that under the umbrella of paternalistic leadership (e.g., Wu et al. 2012), ethical or moral leadership that emphasizes supervisors as ethical role models has been demonstrated to be related to employee empowerment, organizational commitment, and prosocial behaviors in China (Li et al. 2012; Pellegrini & Scandura 2008). For example, Hui et al. (2004) suggest that one’s relationship with a supervisor takes on critical importance to Chinese employees and may anchor the relationship with the organization and one’s emotional attitude toward it. Our study therefore joins the main stream of ethical leadership studies in China and adds insight into the operating mechanisms of ethical leadership in Chinese organizations. However, we acknowledge that it is still an open question whether the results are limited to Chinese contexts or can be generalized to other cultures regardless of different backgrounds and environments. Resick et al. (2006) suggest that characteristics of ethical leadership such as integrity, altruism, and collective motivation are universal across cultures. Moreover, in their 2011 study, Resick and his associates found the convergence of the importance of leader character, consideration and respect for others, and collective orientation as fundamental components of ethical leadership in both Western and Eastern societies. We thus suggest that if our hypotheses about ethical leadership gain support from a Chinese sample, the results could be extended to other cultures. Future research that employs longitudinal data from Western countries may be used to compare the results.

Second, we only included affective organizational commitment as the outcome. We have addressed the importance of affective organizational commitment in today’s organizations and the conceptual link between ethical leadership, altruistic motives, and affective commitment. Future researchers should include other outcome variables in the model and see how attribution may influence more attitudes and behaviors. For example, as the business environment becomes much more dynamic and knowledge-based, employee voice and creativity have been found to be beneficial for organizational effectiveness. It would be interesting to examine how ethical leadership influences employees’ speaking up and creativity behaviors in a political environment.

Third, our study is focused on the positive side of ethical leadership. Less is known about the negative side. In other words, we seem to know less of the impact of unethical leadership on employees. For instance, Kacmar et al. (2013) found that perceptions of unethical leadership lead employees to see their organizations as more political, making them less helpful and promotable to their supervisors. It may be worthwhile for future researchers to investigate the effects of unethical leadership, the mediating mechanisms by which these effects take place, and the boundary conditions that can alter the direction or magnitude of these effects.

Finally, our particular study was specifically designed to be quantitative in nature, using existing validated measures. To extend our proposed model even further, a longitudinal and qualitative design could address ethical leadership more fully. For example, studying ethical leadership from an ethnographic point of view could be enlightening through the collection of a rich source of data. To study ethical leadership in a broader social context, differentiating between the moral orders inside and outside of the organization would also be an informative pursuit.

Conclusion

Taking an attributional perspective, this study supplements the social learning approach to ethical leadership by investigating the mediating role of attribution of intentionality (i.e., attributed altruistic motives) in the relationship between perceived ethical leadership and affective organizational commitment and the moderating role of perceptions of organizational politics in the process of attribution. We provide a more nuanced understanding of how perceived ethical leadership translates into positive outcomes such as affective organizational commitment among employees in the Chinese context. As the characteristics of ethical leadership such as right values, principled decision-making, and consideration and respect for others converge across cultures (Resick et al. 2006, 2011), the results of our study may have implications for organizations in other countries. We hope that our study will stimulate further investigation into the underlying influence mechanisms and the conditions under which ethical leadership affects employee outcomes.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1996). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: An examination of construct validity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 49(3), 252–276.

Allen, T. D., & Rush, M. C. (1998). The effects of organizational citizenship behavior on performance judgments: A field study and a laboratory experiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(2), 247–260.

Avolio, B. J., Bass, B. M., & Jung, D. I. (1999). Re-examining the components of transformational and transactional leadership using the multifactor leadership questionnaire. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 72, 441–462.

Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Weber, T. J. (2009). Leadership: Current theories, research, and future directions. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 421.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliff: PrenUce-Hall.

Barnard, C. (1938). Functions of the executive. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181–217.

Batson, C. D., & Shaw, L. L. (1991). Evidence for altruism: Toward a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry, 2(2), 107–122.

Becker, T. E., & Kernan, M. C. (2003). Matching commitment to supervisors and organizations to in-role and extra-role performance. Human Performance, 16(4), 327–348.

Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley.

Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2003). Self-concordance at work: Toward understanding the motivational effects of transformational leaders. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5), 554–571.

Briscoe, J. P., & Finkelstein, L. M. (2009). The “new career” and organizational commitment: Do boundaryless and protean attitudes make a difference? Career Development International, 14(3), 242–260.

Brislin, R. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Traindis & J. W. Berrym (Eds.), Handbook of cross cultural psychology (pp. 389–444). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Brockner, J. (2002). Making sense of procedural fairness: How high procedural fairness can reduce or heighten the influence of outcome favorability. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 58–76.

Brown, M. E. (2007). Misconceptions of ethical leadership: How to avoid potential pitfalls. Organizational Dynamics, 36(2), 140–155.

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 117–134.

Burns, J. M. (1978). Leadership. NY: Harper & Row.

Cascio, W. F. (2003). Changes in workers, work, and organizations. Handbook of psychology.

Cha, S. E., & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). When values backfire: Leadership, attribution, and disenchantment in a value-driven organization. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 57–78.

Chang, C. H., Rosen, C. C., & Levy, P. E. (2009). The relationship between perceptions of organizational politics and employee attitudes, strain, and behavior: A meta-analytic examination. Academy of Management Journal, 52(4), 779–801.

Chen, C. C., & Farh, J. L. (2009). Developments in Chinese leadership: Paternalism and its elaborations, moderations, and alternatives. In B. M. Harris (Ed.), Handbook of Chinese psychology (pp. 599–622). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chen, Z. X., & Francesco, A. M. (2003). The relationship between the three components of commitment and employee performance in China. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62(3), 490–510.

Cohen, A. (1993). Organizational commitment and turnover: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 36(5), 1140–1157.

Dasborough, M. T., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2002). Emotion and attribution of intentionality in leader-member relationships. The Leadership Quarterly, 13, 615–634.

Dienesch, R. M., & Liden, R. C. (1986). Leader-member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 618–634.

Eastman, K. K. (1994). In the eyes of the beholder: An attributional approach to ingratiation and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 37(5), 1379–1391.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12, 1–22.

Eisenberger, R., Aselage, J., Sucharski, I. L., & Jones, J. R. (2004). Perceived organizational support. In J. Coyle-Shapiro, L. Shore, S. Taylor, & L. Tetrick (Eds.), The employment relationship: Examining psychological and contextual perspectives (pp. 207–225). New York: Oxford University Press.

Eisenberger, R., Karagonlar, G., Stinglhamber, F., Neves, P., Becker, T. E., & Gonzalez-Morales, M. G. (2010). Leader-member exchange and affective organizational commitment: The contribution of supervisor’s organizational embodiment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(6), 1085–1103.

Ferris, G. R., & Kacmar, K. M. (1992). Perceptions of organizational politics. Journal of Management, 18(1), 93–116.

Ferris, G. R., Bhawuk, D. P. S., Fedor, D. F., & Judge, T. A. (1995). Organizational politics and citizenship: attributions of intentionality and construct definition. In M. J. Martinko (Ed.), Advances in attribution theory: An organizational perspective (pp. 231–252). Delray Beach: St. Lucie Press.

Gardner, W. L., & Cleavenger, D. (1998). The impression management strategies associated with transformational leadership at the world-class level a psychohistorical assessment. Management Communication Quarterly, 12(1), 3–41.

Grant, A. M., Dutton, J. E., & Rosso, B. D. (2008). Giving commitment: Employee support programs and the prosocial sensemaking process. Academy of Management Journal, 51(5), 898–918.

Green, S. G., & Mitchell, T. R. (1979). Attributional processes of leaders in leader-member interactions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 23, 429–458.

Griffeth, R. G., Hom, P. W., & Gaertner, S. (2000). A meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488.

Hansen, S. D., Alge, B. J., Brown, M. E., Jackson, C. L., & Dunford, B. B. (2013). Ethical leadership: Assessing the value of a multifoci social exchange perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(3), 435–449.

Harris, K. J., Andrews, M. C., & Kacmar, K. M. (2007). The moderating effects of justice on the relationship between organizational politics and workplace attitudes. Journal of Business and Psychology, 22(2), 135–144.

Harvey, P., Martinko, M. J., & Gardner, W. L. (2006). Promoting authentic behavior in organizations: An attributional perspective. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 12(3), 1–11.

Harvey, P., Harris, K. J., Kacmar, K. M., Buckless, A., & Pescosolido, A. T. (2014a). The impact of political skill on employees’ perceptions of ethical leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 21(1), 5–16.

Harvey, P., Madison, K., Martinko, M., Crook, T., & Crook, T. (2014b). Attribution theory in the organizational sciences: The road traveled and the path ahead. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 28, 128–146.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley.

Hughes, R., Ginnett, R., & Curphy, G. (2014). Leadership: Enhancing the lessons of experience. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Hui, C., Lee, C., & Rousseau, D. M. (2004). Employment relationships in China: Do workers relate to the organization or to people? Organization Science, 15(2), 232–240.

Jaramillo, F., Mulki, J. P., & Marshall, G. W. (2005). A meta-analysis of the relationship between organizational commitment and salesperson job performance: 25 years of research. Journal of Business Research, 58(6), 705–714.

Johnson, Craig E. (2005). Meeting the ethical challenges of leadership (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Joreskog, K. G., & Sorbom, D. (1999). Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kacmar, K. M., & Ferris, G. R. (1991). Perceptions of organizational politics scale (pops): Development and construct validation. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 51(1), 193–205.

Kacmar, K. M., Bachrach, D. G., Harris, K. J., & Zivnuska, S. (2011). Fostering good citizneship through ethical leadership: Exploring the moderating role of gender and organizational politics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 633–642.

Kacmar, K., Andrews, M., Harris, K., & Tepper, B. (2013). Ethical leadership and subordinate outcomes: The mediating role of organizational politics and the moderating role of political skill. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(1), 33–44.

Kelley, H. H. (1972a). Attribution in social interaction. In E. E. Jones, D. E. Kanouse, H. H. Kelley, R. E. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B. Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 1–26). Morristown: Central Learning Press.

Kelley, H. H. (1972b). Causal schemata and the attribution process. In E. E. Jones, D. E. Kanouse, H. H. Kelley, R. E. Nisbett, S. Valins, & B. Weiner (Eds.), Attribution: Perceiving the causes of behavior (pp. 1–26). Morristown: Central Learning Press.

Kelley, H. H. (1973). The processes of causal attribution. American Psychologist, 28, 107–128.

Kelley, H. H., & Michela, J. L. (1980). Attribution theory and research. Annual Review of Psychology, 31, 457–501.

King, R. C., & Bu, N. (2005). Perceptions of the mutual obligations between employees and employers: a comparative study of new generation IT professionals in China and the United States. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 16(1), 46–64.

Kinicki, A. J., & Vecchio, R. P. (1994). Influences on the quality of supervisor–subordinate relations: The role of time pressure, organizational commitment, and locus of control. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 15(1), 75–82.

Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Lamertz, K. (2002). The social construction of fairness: social influence and sense making in organization. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(1), 19–37.

Li, C., Wu, K., Johnson, D. E., & Wu, M. (2012). Moral leadership and psychological empowerment in China. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(1), 90–108.

Liu, J., Kwan, H. K., Fu, P. P., & Mao, Y. (2013). Ethical leadership and job performance in China: the roles of workplace friendships and traditionality. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86, 564–584.

Lord, R. G., & Emrich, C. G. (2001). Thinking outside the box by looking inside the box: Extending the cognitive revolution in leadership research. The Leadership Quarterly, 11, 551–579.

Lord, R. G., & Smith, J. E. (1983). Theoretical, information processing, and situational factors affecting attribution theory models of organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 8(1), 50–60.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7, 83–104.

Martinko, M. J. (1995). The nature and function of attribution theory within the organizational sciences. In M. J. Martinko (Ed.), Advances in attribution theory: an organizational perspective (pp. 7–14). Delray Beach: St. Lucie Press.

Martinko, M. J., & Gardner, W. L. (1987). The leader member attribution process. Academy of Management Review, 12(2), 235–249.

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., & Douglas, S. C. (2007). The role, function, and contribution of attribution theory to leadership: A review. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 561–585.

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., & Desborough, M. T. (2011a). Attribution theory in the organizational sciences: A case of unrealized potential. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 32, 144–149.

Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., Sikora, D., & Douglas, S. C. (2011b). Perceptions of abusive supervision: The role of subordinates’ attribution styles. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(4), 751–764.

Martinko, M. J., Sikora, D., & Harvey, P. (2012). The relationships between attribution styles, LMX, and perceptions of abusive supervision. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 19(4), 397–406.

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 151–171.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52.

Mitchell, T. R., & Wood, R. E. (1980). Supervisor’s responses to subordinate poor performance: A test of an attributional model. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 25(1), 123–138.

Morgan, G. (2006). Images of organization. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd.

Neubert, M. J., Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Roberts, J. A., & Chonko, L. B. (2009). The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: Evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 157–170.

Neubert, M. J., Wu, C., & Roberts, J. A. (2013). The influence of ethical leadership and regulatory focus on employee outcomes. Business Ethics Quarterly, 23(2), 269–296.

Pearce, J. L. (2001). Organization and management in the embrace of government. Malwah: Erlbaum.

Pedhauzer, E. J. (1982). Multiple regression in behavioral research: Explanation and prediction (2nd ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Pellegrini, E. K., & Scandura, T. A. (2008). Paternalistic leadership: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 34(3), 566–593.

Piccolo, R. F., Greenbaum, R., Den Hartog, D. N., & Folger, R. (2010). The relationship between ethical leadership and core job characteristics. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 259–278.

Pilkonis, P. A. (1977). The behavioral consequences of shyness. Journal of Personality, 45(4), 596–611.

Podsakoff, P., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Podsakoff, N. P., LePine, J. A., & LePine, M. A. (2007). Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: a meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 438–454.

Resick, C. J., Hanges, P. J., Dickson, M. W., & Mitchelson, J. K. (2006). A cross-cultural examination of the endorsement of ethical leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(4), 345–359.

Resick, C. J., Martin, G. S., Keating, M. A., Dickson, M. W., Kwan, H. K., & Peng, C. (2011). What ethical leadership means to me: Asian, American, and European perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 101, 435–457.

Riketta, M. (2002). Attitudinal organizational commitment and job performance: a meta-analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(3), 257–266.

Rosen, C. C., & Hochwarter, W. A. (2014). Looking back and falling further behind: The moderating role of rumination on the relationship between organizational politics and employee attitudes, well-being, and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 124(2), 177–189.

Rousseau, D. M. (2004). Psychological contracts in the workplace: Understanding the ties that motivate. Academy of Management Executive, 18(1), 120–127.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.

Sosik, J. J., Avolio, B. J., & Jung, D. I. (2002). Beneath the mask: Examining the relationship of self-presentation attributes and impression management to charismatic leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 13(3), 217–242.

Steinbauer, R., Renn, R. W., Taylor, R. R., & Njoroge, P. K. (2014). Ethical leadership and followers’ moral judgment: The role of followers’ perceived accountability and self-leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(3), 381–392.

Sue-Chan, C., Chen, Z., & Lam, W. (2011). LMX, coaching attributions, and employee performance. Group and Organization Management, 36(4), 466–498.

Taylor, S. G., & Pattie, M. W. (2014). When does ethical leadership affect workplace incivility? The moderating role of follower personality. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24(4), 595–616.

Tepper, B. J., Henle, C. A., Lambert, L. S., Giacalone, R. A., & Duffy, M. K. (2008). Abusive supervision and subordinates’ organization deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(4), 721–732.

Trevino, L. K. (1998). Ethical dimensions of international management. Personnel Psychology, 51(1), 241–244.

Treviño, L. K., Hartman, L. P., & Brown, M. (2000). Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review, 42(4), 128.

Treviño, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 56(1), 5–37.

Tu, Y., & Lu, X. (2013). How ethical leadership influence employees’ innovative work behavior: A perspective of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Business Ethics, 116, 441–455.

Walumbwa, F., Mayer, D. M., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K., & Christensen, A. L. (2011). Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader-member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115, 204–213.

Whiting, S. W., Maynes, T. D., Podsakoff, N. P., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2012). Effects of message, source, and context on evaluations of employee voice behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(1), 159–182.

Wood, R., & Bandura, A. (1989). Social Cognitive Theory of Organizational Management. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 361–384.

Wu, M., Huang, X., Li, C., & Liu, W. (2012). Perceived interactional justice and trust-in-supervisor as mediators for paternalistic leadership. Management and Organization Review, 8(1), 97–121.

Yukl, G., Mahsud, R., Hassan, S., & Prussia, G. E. (2013). An improved measure of ethical leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 20(1), 38–48.

Zhu, W., May, D. R., & Avolio, B. J. (2004). The impact of ethical leadership behavior on employee outcomes: the roles of psychological empowerment and authenticity. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 11(1), 16–26.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Wu, K., Johnson, D.E. et al. Going Against the Grain Works: An Attributional Perspective of Perceived Ethical Leadership. J Bus Ethics 141, 87–102 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2698-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2698-x