Abstract

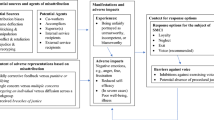

This paper examines the interactive effects of apology source (i.e., whether an apology is given by a chief executive officer or employee) and apology components (i.e., acknowledgment, remorse, and compensation) on forgiveness. Results revealed a significant source by component interaction. A remorseful employee apology was more successful than a remorseful CEO apology because consumers felt more empathy for the employee. Furthermore, a compensatory CEO apology was more effective than a compensatory employee apology because CEOs could significantly affect consumer perceptions of justice. No significant differences were found between apology source and the apology component of acknowledging violated rules and norms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

It seems to be a time of both transgression and transparency. Companies are engaging in dubious behaviors, and such violations are rising to the fore. In response to these transgressions, firms are issuing innumerable apologies that they hope will repair consumer relationships and protect corporate reputations (Lazare 2005). Even the President of the United States has resorted to a handwritten apology for his implied disparagement of an art history course (Brooks 2014). For the most part, apology is in the firm’s best interest. Research suggests that apologies can often be beneficial (e.g., Basford et al. 2014; Darby and Schlenker 1982; Eaton et al. 2006; Exline and Baumeister 2000; Tucker et al. 2006). For example, apologies are associated with increases in purchasing behavior (Liao 2007) and positive word-of-mouth intentions (Lyon and Cameron 2004). However, such salutary effects do not automatically ensue. More recent research suggests that apologies can have harmful results, especially if not done well (e.g., DeCremer et al. 2010; Zechmeister et al. 2004). For example, Risen and Gilovich (2007) found that apologizers offering a coerced apology were rated as less likable than apologizers offering a spontaneous apology.

With these findings in mind, apology research has shifted from answering the question of “Are apologies effective?” to the more difficult question of “What are the moderators of the apology-outcome relationship?” In other words, what variables make an apology more likely to elicit forgiveness and other positive outcomes? This growing literature has identified several moderators, including severity of the transgression (Boon and Sulsky 1997; Girard and Mullet 1997), characteristics of the offended party (e.g., Enright et al. 1989; Park and Enright 1997), and timing of the apology (Frantz and Bennigson 2005). This list of potential moderators is, of course, not exhaustive. In fact, we believe a very important moderator requires further examination. This moderator is “source of apology,” or the person who is apologizing. The purpose of this study is to examine the role of source as a potential moderator of the apology–forgiveness relationship in a business context. For the current investigation, we use McCullough et al.’s (2013) definition of forgiveness: a “set of motivational changes whereby an individual becomes (a) less motivated to retaliate against an aggressor; (b) less motivated to maintain estrangement from an aggressor; and (c) more motivated by good will for the aggressor” (p. 12).

In this research, we contribute to the literature in two ways: First, we show the impact of apology source (i.e., CEO or employee) on forgiveness. Second, we examine the interaction among certain apology components (i.e., verbal statements included in an apology) and source in the prediction of forgiveness.

We organize the paper as follows: We first discuss the role apology source may play in the effectiveness of apologies. We next review the literature on apology components that may interact with source in predicting apology effectiveness. Then, we discuss our methodology and present our data. Finally, we discuss theoretical implications and provide recommendations for managers.

The Source of an Apology

Employees often make mistakes that their employers address in public forums. For example, when an employee at AT&T posted an offensive photo on 9/11, CEO Randall Stephenson issued a personal apology on the company’s consumer blog (Taube 2013). In another 9/11 episode, Starbucks employees charged first responders for bottled water, prompting a public apology by CEO Orin Smith (Associated Press 2001). In other cases, the employees themselves will apologize. For example, when MIT admissions officers erroneously emailed prospective students that they were admitted to the institute, Chris Peterson, an admissions counselor, was the one to apologize (Peterson 2014). Yet there are scant data on which is the optimal strategy. To date, no research examines whether a CEO should apologize for behavior caused by an employee or whether the employee should offer the apology. Were employees to apologize for their own errant behavior, what consequences might ensue? Would their statement have more import than one from the CEO?

In our review of the literature, only one study has specifically examined source effects on apology effectiveness. Bisel and Messersmith (2012) asked participants to rate to what extent they would forgive a friend, supervisor, or retail store if the delinquent party owed the participant $500 for 90 days. Results revealed a pre-apology difference in that participants were less willing to forgive the retail store over the other sources. However, post apology, there were no significant differences in forgiveness. Thus, Bisel and Messersmith suggest “communicating apologies can be similarly effective in increasing feelings of forgiveness in work settings as compared to interpersonal contexts” (p. 434). In this particular study, participants in all three conditions read identical apologies. Yet this approach is not situationally realistic since apologies tend to differ in the verbal components they contain, especially when these apologies emanate from multiple sources. Thus, we believe that Bisel and Messersmith may not have found differences because they failed to test interactions among components and sources. It might be that certain verbal components prove more effective when used by certain sources. Thus, the purpose of the current study is to examine interactions among components and sources in predicting various positive outcomes. Below, we describe the apology components.

The Apology Components

Research on apology verbal statements has typically grouped apology components into three overarching rubrics: an acknowledgment of violated rules and norms, an expression of remorse, and an offer of compensation (Hill 2013).

Acknowledgment of Violated Rules and Norms

The literature indicates transgressor apologies are often successful if they include an admission of wrongdoing (e.g., Scher and Darley 1997). By acknowledging violation of rules or norms, transgressors publicly proclaim their lapse and assume responsibility for the deviant pattern they exhibited. Through self-sourcing causation of the errant behavior, they project a sense of personal awareness. This inclination toward internal attribution not only validates victims’ sense of mistreatment, but it also suggests that the transgressor’s candid and transparent statement might forestall recurrent behavior. By assuming responsibility for the present, wrongdoers can assure offended parties that further infractions are unlikely.

Remorse

Remorse is an expression of guilt for wrongful action (Boyd 2011). Having sensed the perspective of the offended party, transgressors can verbally declare their sense of shame even as they emotionally display guilt for precipitating the aggrievement. For example, an apologizer might say, “I understand that you are upset and I feel terrible.” Such combinations of a cognitive and affective approach have shown efficacy in eliciting forgiveness (Schmitt et al. 2004).

Compensation

Finally, compensation refers to redressing a wrong. Here transgressors engage in a demonstrable act to offset the damaging deed. For example, a service provider may offer dissatisfied customers a refund. While such a gesture cannot negate the original misstep, it can mollify public reaction to it. Monetary compensation is the obvious form of tangible redress, but efforts to restore respect and reputation for the victim can also confer a sense of restorative equilibrium. Several studies have confirmed the effectiveness of compensation in an apology (Conlon and Murray 1996; Scher and Darley 1997; Schmitt et al. 2004). For example, in addressing product complaints, Conlon and Murray (1996) concluded that compensation was associated with customer satisfaction.

Why Do the Components Work?

Although research has demonstrated the success of each component, we believe the components’ efficacy may interact with the source of the apology. In forming our hypotheses, we first discuss the mechanisms by which each apology component might work.

Acknowledgment Affects Attributions

We propose that acknowledgment of violated rules and norms will produce forgiveness because it can enhance victims’ positive perceptions of the transgressor. By admitting wrongdoing, violators may convey the message that they are not miscreants presiding over malevolent firms; any misdeed was an anomalous event. As a result, when doers acknowledge errant behavior and recognize their moral fallibility, they often override the offended party's tendency to make trait attributions (Weiner et al. 1991). Furthermore, if the offended party believes that the transgressor is fundamentally good and is unlikely to repeat the transgression, then the offended party will be inclined to forgive the transgressor.

When CEO apologies acknowledge that a transgression has violated rules and norms, we propose that they will be more successful than employee declarations. As the face and titular head of the firm, the CEO can convince the public that the transgression was an isolated event and that the rest of the firm does not condone this behavior. Thus, the majority of the firm is “good” and would never engage in dubious deeds. This acknowledgment prods public perception toward a situational rather than a dispositional attribution (e.g., this is a bad firm). A situational attribution suggests that the atypical transgression will not recur and thus allows the emergence of forgiveness. Thus, we hypothesize that

H1

An acknowledging CEO apology will elicit more forgiveness than an acknowledging employee apology.

H2

For acknowledging apologies, consumer attributions (i.e., situational or dispositional) will mediate the relationship between apology source (i.e., CEO or employee) and forgiveness.

Remorse Induces Empathy

An apology may activate an empathic response from the apology recipients toward the apologizer (Baumeister et al. 1994). Empathy is, in part, a “shared emotional response between an observer and a stimulus person” (Feshbach 1975) and may be more likely to occur if the apologizer is expressing remorse or other strong emotions that evoke recipient recognition and response. Recipients may exhibit their empathy for the apologizer in several ways, including response with affective feelings. For example, the recipient may feel and subsequently express sympathy for the apologizer (Fehr et al. 2010).

Empathy is associated with prosocial behavior. Thus, if the apology recipient expresses empathy for the apologizer, the recipient may proceed to engage in prosocial behavior. Such prosocial behavior may include forgiveness and a reduced motivation for retaliation (Batson 1990, 1991; Baumeister et al. 1994; Eisenberg and Miller 1987).

Rather than embedding remorse in a CEO apology, we believe that it may prove more effective when included in an employee apology. An empathic response is more likely to be targeted toward an ingroup member (e.g., Brown et al. 2006). That is, offended parties are more likely to feel empathy and to show sympathy for those they believe are similar to themselves. In this case, the apologizing employee may be considered part of an “ingroup” cohort more than the CEO who occupies a rarified niche in the minds of many organizational observers. Thus, we hypothesize that

H3

A remorseful employee apology will elicit more forgiveness than a remorseful CEO apology.

H4

For remorseful apologies, consumer empathy for the apologizer will mediate the relationship between apology source (i.e., CEO or employee) and forgiveness.

Compensation Restores Justice

Equity theory states that transgressions create relationship inequality because negative outcomes are more frequent or intense for the offended party than the transgressor (Walster et al. 1973). For forgiveness to occur, equality and justice must be restored. Offended parties’ perceptions of justice vary along three dimensions: distributive, procedural, and interactional. Distributive justice comprises exchange outcomes (Adams 1965; Homans 1961). Procedural justice involves the process in which decisions are made and the ease of conflict resolution (Lind and Tyler 1988). Finally, interactional justice involves information exchange and the communication of outcomes (Bies and Moag 1986). The literature has shown that compensation strategies can produce perceptions of justice (Smith et al. 1999). We believe apology source may influence how effective the compensation strategies are on justice. Specifically, we believe compensatory CEO apologies will elicit stronger perceptions of distributive and interactional justice than compensatory employee apologies will. Because a CEO offer of apology can call upon powerful and pervasive reparative behaviors, it will more likely satisfy consumers’ sense of distributive justice than will an employee offer of compensation. Furthermore, when an apology comes from a CEO, offended parties may believe that the entire company is aware of the transgression and cares about those affected. If the apology comes only from an employee, then the circumscribed context may cause the offended party to feel ignored or underappreciated, thereby constraining any sense of interactional justice. Because a CEO offer of apology will elicit stronger perceptions of equity and justice, it will likely be more impactful than an employee offer of compensation. Thus, we hypothesize that

H5

A compensatory CEO apology will elicit more forgiveness than a compensatory employee apology.

H6

For compensatory apologies, consumer perceptions of justice will mediate the relationship between apology source (i.e., CEO or employee) and forgiveness.

Method

Participants

One-hundred-six participants (77 females, 29 males) were recruited using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk program. They were told the purpose of the study was to investigate “Opinions about Apologies.” Participant age ranged from 18 to 61 with a mean age of 29.13 (SD = 9.94). Participants received remuneration for completing the survey.

Materials and Procedure

After consenting to partake in the study, participants were prompted with a vignette that read as follows:

Imagine yourself in the following situation: It is summertime and you have just returned home from work. You are about to start cooking dinner when your electricity goes out. The outage lasts for 3 hours. Consequently, you have missed your favorite TV program, were forced to eat in the dark, and were unable to complete the work you had brought home that is due the next day. When your power finally returns, you learn the outage was caused by a maintenance engineer controlling electricity demand at a regional center. His favorite sports team was playing and he was distracted by the game on TV. As a result your home lost power from 7 to 10 pm.

After reading the background information, participants were randomly assigned to one of six apology conditions. Three of the apology conditions contained apologies given by the CEO, while the remaining three conditions contained apologies given by the offending employee. Within the CEO and employee apology conditions, one condition contained an apology in which the apologizer acknowledges having violated rules and norms, one contained a remorseful apology, and the final condition contained an apologizer offer of compensation (see Appendix for examples). Thus, we used a 2 × 3 factorial design.

After reading the apology, participants reported to what extent they would forgive the transgressing company. As mentioned earlier, we used McCullough et al.’s (2013) definition of forgiveness. Under this definition, forgiveness is a change in motivation where forgivers become more willing to approach, and less likely to avoid, the transgressor. We adopted items from the transgression-related interpersonal motivation inventory (TRIM; McCullough et al. 1998) and the Enright forgiveness inventory (EFI; Subkoviak et al. 1992) and modified them so they would fit our corporate context. Our final items included to what extent the participants would (1) forgive the company, (2) trust the company, (3) talk positively about the company to others (i.e., positive word-of-mouth intentions), and (4) feel satisfied with the company. We used a scale that ranged from 1 (very unlikely) to 5 (very likely). The scale was reliable with a Cronbach’s alpha of .85 so we combined all items to create one dependent variable.

To understand why differences may occur, we also asked participants to report to what extent they believed the transgression was due to circumstances beyond the company’s control (i.e., attributions). To measure empathy we asked participants to what extent they felt sympathy for the employee (i.e., we measured the affective response of empathy), and finally to measure justice we asked to what extent they felt the company had made up for what had happened.

Results and Discussion

To begin, a two-way ANOVA was conducted that examined the effect of source (i.e., CEO or employee) and apology component (i.e., acknowledgment, remorse, and compensation) on forgiveness. Results are presented in Table 1. As the table shows, there were no main effects for either source or component. However, there was a significant interaction, F (2, 104) = 5.14, p < .05.

To decompose the two-way interaction, we compared our apology sources by component. For this analysis, an ANOVA was conducted to compare the CEO and employee (1) acknowledgment apologies, (2) remorseful apologies, and (3) compensation apologies. Results revealed that remorseful apologies are best done by employees F (1, 30) = 13.93, p < .01. Participants reported higher levels of forgiveness when the employee (M = 3.13) was the source of the apology as opposed to the CEO (M = 2.45). This finding supported H3. In addition, participants preferred the CEO compensation condition (M = 2.96) to the employee compensation condition (M = 2.47), evident by increased reports of forgiveness, F (1, 30) = 2.94, p < .10. This finding supports H5. Finally, sources did not differ significantly for acknowledging apologies, F (1, 30) = .912, p = .35. When comparing the CEO (M = 2.88) and employee conditions (M = 2.59), an acknowledging apology did not result in more forgiveness. Thus, we failed to find support for H1.

Mediation

Preacher and Hayes (2004) argue for the use of mediation analysis to assess the indirect effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable through a proposed mediator. For the current study, we were interested in whether our source effects were mediated by empathy or justice. More specifically, we were interested in (1) whether empathy mediated the relationship between source and forgiveness for remorseful apologies and (2) whether justice mediated the relationship between source and forgiveness for compensation apologies. We did not test whether attributions mediated the relationship between source and outcomes for acknowledging apologies (i.e., hypothesis 2) because we found no difference in source here. Thus, we conducted two separate mediation analyses to test these questions. To test for mediation we followed recent guidelines from the literature (Zhao et al. 2010). Specifically, we examined the statistical significance of the indirect effect of source on the outcomes via the mediator (empathy and justice) using the Preacher and Hayes (2008) bootstrapping procedure. See Table 2 for results.

For the first mediation, we tested whether empathy mediated the effect of source on forgiveness within the remorseful apology condition (H4). As compared to the CEO apology, the employee apology showed a significant and positive effect on empathy (β = .94, p < .01). Furthermore, the relationship between empathy and forgiveness was significant (β = .40, p < .01). The relationship between source and forgiveness was also significant (β = .67, p < .01). Next, we examined the indirect effect of our mediator on forgiveness. The indirect effect was significant (point estimated for indirect effect = .378; 95 % CI .122–.832). Finally, when controlling for empathy, the significant direct effect of source on forgiveness became nonsignificant. The results thus suggest full mediation for this relationship and support H4.

For our second mediation analysis, we tested whether justice mediated the effect of source on forgiveness within the compensation apology condition (H6). As compared to the employee apology, the CEO apology had a significant effect on justice (β = 1.03, p < .01). Furthermore, the relationship between justice and forgiveness was significant (β = .561, p < .01). The relationship between source and forgiveness was also marginally significant (β = .488, p < .10). Next, we examined the indirect effect of our mediator on forgiveness. The indirect effect was significant (point estimated for indirect effect = .58; 95 % CI .226–1.08). Finally, when controlling for empathy, the significant direct effect of source on forgiveness became nonsignificant. Thus, justice fully mediated the relationship between source and forgiveness, thereby providing support for H6.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine the interactive effects of apology source (i.e., CEO or employee) and apology components (i.e., acknowledgment, remorse, and compensation) on forgiveness.

Our results reveal no main effects for apology source (i.e., CEO or employee) suggesting that either source may effectively apologize to a firm’s consumers. Further, we found no main effect for apology components. It is important to note that this does not mean the components were ineffective. Rather this finding signifies that all the components equally elicit forgiveness. Our results also revealed a source × component interaction.

Decomposing our interaction, we found if a remorseful apology is to be given, then an employee should apologize rather than the CEO. Such a situation may arise if a firm does not have sufficient resources to offer compensation. Mediation analyses revealed participants felt more empathy for the remorseful employee than for the remorseful CEO; this sympathetic sentiment prompted more forgiveness. If compensation is available, then our results suggest the CEO should be the source of the apology because the CEO can elicit more robust perceptions of justice than an employee can. In general, we believe it may be best for both the CEO and the employee to apologize as they elicit different, yet important, consumer responses (i.e., empathy and justice) that result in forgiveness. Furthermore, it is important to note that although we found no source effect for acknowledgment, it is still an important component in public apologies. Without this confessional platform, the other mediators cannot come into play. Acknowledgment serves as a precursor for the efficacy of remorse and compensation.

Limitations and Future Research

The current study was conducted using a vignette that represents only one type of transgression. Some might view the situation depicted as more reflective of an operational misstep than a moral lapse. Although we believe the effects found in this study could logically be generalized to other failure types, future research should seek to replicate our results in different contexts. For example, if the transgression involves a procedural failure where a service representative is rude to a customer, then remorse may be the only response necessary.

A related question is how dramatically commission is colored by consequence. The results of the plant operator’s actions were relatively localized and self-contained. If the power plant failure had led to more financial distress, then further compensation might have been required. Were the power outage to have precipitated a vehicular accident that caused loss of life, the remorseful component would likely need accentuation. In addition, historical patterns of abuse might moderate results. If the public were judging recurrent behavior rather than a standalone event, then different apology elements might hold sway.

A final avenue for future research is to examine the power of apology source when a myriad of employees transgresses. We focused on a singular employee, but in many cases, numerous employees are transgressing because an insidious practice has become engrained within the local culture. If only one of the transgressing employees is acting as the apologetic representative of a group, then this sole spokesperson may be unable to exculpate multiple agents. Researchers should test this possibility to better prepare firms for crisis management.

In conclusion, our research contributes empirically to the existing research on apology. The results of our experiment revealed that (1) there are no main effects for apology source, (2) there is a significant interaction between apology source and apology components in predicting forgiveness, and (3) empathy and justice can help to explain why these interactive effects may occur. With our findings, practitioners can now be more aware of apology nuances and thus better poised to induce ethical clarity within their firms.

References

Adams, J. S. (1965). Inequity in social exchange. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 2, 267–299.

Associated Press. (2001). Starbucks apologizes for charging rescuers for water. USA Today. Retrieved March 31, 2014, from http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2001/09/25/starbucks.htm.

Basford, T. E., Offermann, L. R., & Behrend, T. S. (2014). Please accept my sincerest apologies: Examining follower reactions to leader apology. Journal of Business Ethics, 119(1), 99–117.

Batson, C. D. (1990). How social an animal? The human capacity for caring. American Psychologist, 45(3), 336–346. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.3.336.

Batson, C. (1991). The altruism question: Toward a social-psychological answer. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115(2), 243–267. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.243.

Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. S. (1986). Interactional justice: Communication criteria of fairness. Research on Negotiation in Organizations, 1(1), 43–55.

Bisel, R. S., & Messersmith, A. S. (2012). Organizational and supervisory apology effectiveness apology giving in work settings. Business Communication Quarterly, 75(4), 425–448.

Boon, S. D., & Sulsky, L. M. (1997). Attributions of blame and forgiveness in romantic relationships: A policy-capturing study. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 12, 19–44.

Boyd, D. P. (2011). Art and artifice in public apologies. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(3), 299–309.

Brooks, K. (2014). President Obama sends handwritten apology to art history professor. The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 31, 2014 from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/02/18/obama-art-history_n_4809007.html.

Brown, L. M., Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (2006). Affective reactions to pictures of ingroup and outgroup members. Biological Psychology, 71(3), 303–311.

Conlon, D. E., & Murray, N. M. (1996). Customer perceptions of corporate responses to product complaints: The role of explanations. Academy of Management Journal, 39(4), 1040–1056. doi:10.2307/256723.

Darby, B. W., & Schlenker, B. R. (1982). Children’s reactions to apologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43(4), 742–753. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.43.4.742.

DeCremer, D., van Dijk, E., & Pillutla, M. M. (2010). Explaining unfair offers in ultimatum games and their effects on trust: An experimental approach. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20(1), 107–126.

Eaton, J., Struthers, C., & Santelli, A. G. (2006). The mediating role of perceptual validation in the repentance–forgiveness process. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(10), 1389–1401. doi:10.1177/0146167206291005.

Eisenberg, N., & Miller, P. A. (1987). The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 101(1), 91–119. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.91.

Enright, R. D., Santos, M. J., & Al-Mabuk, R. (1989). The adolescent as forgiver. Journal of Adolescence, 12(1), 95–110.

Exline, J.J., & Baumeister, R.F. (2000). Expressing forgiveness and repentance. Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice, 133–155.

Fehr, R., Gelfand, M. J., & Nag, M. (2010). The road to forgiveness: A meta-analytic synthesis of its situational and dispositional correlates. Psychological Bulletin, 136(5), 894.

Feshbach, N. D. (1975). Empathy in children: Some theoretical and empirical considerations. The Counseling Psychologist, 5(2), 25–30. doi:10.1177/001100007500500207.

Frantz, C., & Bennigson, C. (2005). Better late than early: The influence of timing on apology effectiveness. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41(2), 201–207. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2004.07.007.

Girard, M., & Mullet, E. (1997). Forgiveness in adolescents, young, middle-aged, and older adults. Journal of Adult Development, 4(4), 209–220.

Hill, K. M. (2013). When are apologies effective? An investigation of the components that increase an apology’s efficacy (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved March 31, 2014 from http://iris.lib.neu.edu/psych_diss/29/.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Lazare, A. (2005). On apology. Oxford: Oxford University Press Inc.

Liao, H. (2007). Do it right this time: The role of employee service recovery performance in customer-perceived justice and customer loyalty after service failures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 475–489. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.475.

Lind, E.A., & Tyler, T.R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. Springer.

Lyon, L., & Cameron, G. T. (2004). A relational approach examining the interplay of prior reputation and immediate response to a crisis. Journal of Public Relations Research, 16(3), 213–241. doi:10.1207/s1532754xjprr1603_1.

McCullough, M. E., Kurzban, R., & Tabak, B. A. (2013). Cognitive systems for revenge and forgiveness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(1), 1–15.

McCullough, M. E., Rachal, K. C., Sandage, S. J., Worthington, E. L, Jr, Brown, S. W., & Hight, T. L. (1998). Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships: II. Theoretical elaboration and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(6), 1586.

Park, Y. O., & Enright, R. D. (1997). The development of forgiveness in the context of adolescent friendship conflict in Korea. Journal of Adolescence, 20(4), 393–402.

Peterson, C. (2014). About that email. MIT Admissions Blog. Retrieved March 31, 2014 from http://mitadmissions.org/blogs/entry/about-that-email.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. doi:10.3758/BF03206553.

Preacher, K.J., & Hayes, A.F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior research methods, 40(3), 879–891.

Risen, J. L., & Gilovich, T. (2007). Target and observer differences in the acceptance of questionable apologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 418.

Scher, S. J., & Darley, J. M. (1997). How effective are the things people say to apologize? Effects of the realization of the apology speech act. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 26(1), 127–140.

Schmitt, M., Gollwitzer, M., Förster, N., & Montada, L. (2004). Effects of objective and subjective account components on forgiving. The Journal of Social Psychology, 144(5), 465–485. doi:10.3200/SOCP.144.5.465-486.

Smith, A. K., Bolton, R. N., & Wagner, J. (1999). A model of customer satisfaction with service encounters involving failure and recovery. Journal of Marketing Research, 36, 356–372.

Subkoviak, M.J., Enright, R.D., & Wu, C.R. (1992, October). Current developments related to measuring forgiveness. In Annual meeting of the Mid-Western Educational Research Association. Chicago.

Taube, A. (2013, September). AT&T CEO apologizes for yesterday’s 9/11 tweet. Business Insider. Retrieved March 31, 2014 from http://www.businessinsider.com/att-ceo-911-tweet-apology-2013-9.

Tucker, S., Turner, N., Barling, J., Reid, E. M., & Elving, C. (2006). Apologies and transformational leadership. Journal of Business Ethics, 63(2), 195–207.

Walster, E., Berscheid, E., & Walster, G. W. (1973). New directions in equity research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25(2), 151–176.

Weiner, B., Graham, S., Peter, O., & Zmuidinas, M. (1991). Public confession and forgiveness. Journal of Personality, 59(2), 281–312. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1991.tb00777.x.

Zechmeister, J. S., Garcia, S., Romero, C., & Vas, S. N. (2004). Don’t apologize unless you mean it: A laboratory investigation of forgiveness and retaliation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(4), 532–564. doi:10.1521/jscp.23.4.532.40309.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hill, K.M., Boyd, D.P. Who Should Apologize When an Employee Transgresses? Source Effects on Apology Effectiveness. J Bus Ethics 130, 163–170 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2205-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2205-9