Abstract

There is growing regulatory pressure on firms worldwide to address the under-representation of women in senior positions. Regulators have taken a variety of approaches to the issue. We investigate a jurisdiction that has issued recommendations and disclosure requirements, rather than implementing quotas. Much of the rhetoric surrounding gender diversity centres on whether diversity has a financial impact. In this paper we take an aggregate (market-level) approach and compare the performance of portfolios of firms with gender diverse boards to those without. We also investigate whether having multiple women on the board is linked to performance, and if there is a within-industry effect. Overall, we do not find evidence of an association between diversity and performance. We find some weak evidence of a negative correlation between having multiple women on the board and performance, but that in some industries diversity is positively correlated with performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Board gender diversity has become a widely debated corporate governance topic over the last decade. Indeed, as reported below, some capital market regulators have moved to impose gender quotas on boards; whereas others have taken a more “best practice” approach and provided recommendations and/or disclosure requirements on firms with respect to their gender diversity profiles. We categorise these approaches to corporate governance and board composition as either “mandated” or “self-regulation”. At the core of the regulatory debate is the nature of the value to be created from diverse boards and the practical pressure it imposes on firms to respond to these corporate governance initiatives.

Individual firms may face the cost of changing their board composition, or at least the cost of defending (disclosing) current practices. Academic literature from a variety of disciplines argues that an initiative such as board diversity is not solely an economic concern, but a matter that also may appeal to various social factors, recognising that firms participate not just in capital markets but in society as a whole (Hafsi and Turgut 2013). However, the intriguing proposition that motivates the narrow focus in this study is the explicit statement from the Australian market operator that improving gender diversity enhances company performance—as an economic construct:

Research has shown that increased gender diversity on boards is associated with better financial performance, and that improved workforce participation at all levels positively impacts on the economy. (ASX 2010)Footnote 1

Market operators, such as securities exchanges, routinely issue best practice corporate governance guidelines. In recent years, market operators and law makers have begun to try to address the clear under-representation of women in the upper echelons of the corporate world. Particularly, for example, in Australia and the UK, the market operators recommend that listed companies disclose and explain their chosen diversity policy and self-assessed performance (ASX 2010; FRC 2012)Footnote 2: a self-regulated approach. An increased regulatory focus on board gender diversity and improving the overall diversity of corporate boards indicates that policy makers consider diversity at the board level important. However, a natural question that arises from the regulatory intervention is whether there is any measurable economic result.

The aim of this study is to investigate the economic impact of board gender diversity initiatives promulgated by securities market operators, in a self-regulated environment. Prior literature on the economic impact of diversity tends to focus on individual firm effects. This study extends the literature by taking an overall or aggregate view of financial performance in the capital markets. Specifically, we construct portfolios of firms with gender diverse boards and compare their returns over time to portfolios of firms with all-male boards. Our innovation is that we take a portfolio, or aggregate approach to measuring impact, not just a firm-level approach.

Taking a portfolio approach also provides a substantial econometric improvement over firm-level (panel) analysis. Corporate governance research is plagued by endogeneity, including issues caused by omitted variables, heterogeneity among samples and reverse causality. Forming portfolios means that firm-specific characteristics are averaged out, eliminating both the heterogeneity issue and also reducing the omitted variables problem—which arises because firm-specific characteristics (independent variables) impact firm-level outcomes (dependent variables). Further, presumably the market regulator is interested in the impact of regulation on overall market outcomes, and not on specific firms. Using portfolios also has the advantage of more accurately reflecting how the new regulation will impact the overall market on average, rather than the impact on specific firms.

The Australian capital market setting is ideal for this study as we are able to investigate the transition of a market from purely voluntary board composition decisions, through to more recent times in which the gender diversity recommendation has been incorporated into best practice guidelines. Although this became formal in 2010, there had been considerable interest in and leakage of the proposed regulation prior to this. The self-regulatory approach in Australia is relevant to other market jurisdictions, for example, the UK that has adopted a disclosure approach, as well as those markets that remain unregulated on board gender diversity, such as in North America. The alternative approach is to mandate quotas, and this approach has been taken in European countries such as France, Finland, Italy, Spain, Norway and the Netherlands. There has been considerable research interest in these markets as to the economic benefits brought about by legislative mandate (Torchia et al. 2011; Ahern and Dittmar 2012). The regulatory position can be a “moving target” of course: if the persuasiveness of the guidelines does not affect real change in Australian corporate boards, the Australian Discrimination Commissioner has signalled a move to mandatory quotas in 2015 (AHRC 2010).Footnote 3

The descriptive statistics show the transition: in the years of voluntary adoption of board diversity (between 2004 and 2010), the percentage of sample companies with a diverse board hovered between 36 and 42 %. In the year after self-regulation (2011), 52 % of the sample companies reported a diverse board. One of the peak industry bodies, the Australian Institute of Company Directors (AICD 2012), reports that it is only since 2010 that women have been recruited to boards in relatively larger numbers.Footnote 4 This move to self-regulation provides an ideal opportunity to investigate questions of director diversity. Until the start of this decade, there have been insufficient observations to perform research using statistical techniques. For this reason, we classify diversity as boards with one female director, as opposed to none. Further discrimination is difficult given the data, but nevertheless we believe this analysis is extremely topical and timely.

In terms of our results, we find no compelling evidence of a clear performance differential between firms with and without female directors. However, we suggest that there are plausible circumstances in which a firm that is larger, more established and in a particular industry may “trade up” to diversity as a business proposition, but not necessarily for clear-cut quantifiable economic reasons.

Accordingly, we see the contribution of the research as focussing on a particular aspect of the regulatory debate: to measure the extent of the economic benefit, if any, to the market of the regulatory initiative. That the results do not show superior portfolio returns for diverse boards is still informative to the regulatory debate and the academic challenge to identify and measure the benefits and enhancements brought about by board diversity.

This paper proceeds as follows. The background and literature is reviewed and contextualised in the next section and data described in section three. We present the methodology in the fourth section. Results and analysis are presented in the fifth section, and the final section concludes with insights to the regulatory impetus.

Background and Literature

Regulatory Background

On 30 June 2010 the primary Australian market operator, the Australian Securities Exchange, announced the latest changes to its Corporate Governance principles (ASX 2010) recommending:Footnote 5

- 1.

Companies should establish a policy concerning diversity and disclose the policy or a summary of that policy. The policy should include requirements for the board to establish measurable objectives for achieving gender diversity (and) for the board to assess annually both the objectives and progress in achieving them.

- 2.

Companies should disclose in each annual report the measurable objectives for achieving gender diversity set by the board in accordance with the diversity policy and progress towards achieving them.

- 3.

Companies should disclose in each annual report the proportion of women employees in the whole organisation, women in senior executive positions and women on the board.

As an example, Table 1 demonstrates how a large diversified firm listed on the ASX, Wesfarmers Ltd., has complied with the these three aspects of recommended disclosure. In its 2012 annual report, the company reported its performance across measurable objectives (to foster an inclusive culture; improve talent management; enhance recruitment policies and ensure pay equity) and numerical data on women employees, managers and directors.Footnote 6

The problem this corporate governance recommendation seeks to address is the under-representation of women in corporate management—particularly at the senior, board, level. Australia is by no means alone in seeking to address the lack of female representation; indeed, other countries have implemented far more onerous requirements, for example:

-

France—women must hold 20 % of board positions by 2014, and 40 % by 2017.

-

Italy—women must comprise 33 % of board positions by 2015. Non-compliance will result in a fine of €1 million.

-

Finland—companies have been required to have at least one woman on the board since July 2010.

As previously noted, the ASX’s stated motivation for implementing change to the corporate governance principles explicitly quotes enhanced company performance. This claim by the ASX is puzzling because a positive association between gender diversity and performance has not been convincingly established in the available academic literature. The alternative explanations are that firms will appoint women directors for other reasons—for example, the firm is already performing well and there is external pressure for diverse boards (Farrell and Hersch 2005); or that “women may be being preferentially placed in leadership roles that are associated with an increased risk of negative consequence” (Ryan and Haslam 2005, p. 83). Commentary from other disciplines argues a strong case for moral or social legitimacy—firms choose gender diverse boards for a variety of reasons and the “business case” is not solely an economic imperative (Carter et al. 2010; Fairfax 2011), but offers a signal of the firm’s commitment to its reputation and image to all stakeholders (consumers, employees, etc.), not just investors (Burke 1997; Broome and Krawiec 2008). Below, we summarise the academic literature on the impact of gender diversity on firm performance and similar types of constructs.

Influence of Female Directors on Firm Performance

Most corporate governance research into gender diversity that involves financial or market measures takes an agency theory approach (Terjesen et al. 2009). According to agency theory, the board of directors is the primary monitoring mechanism to curb management’s tendency to behave in a self-interested manner and not in the best interest of shareholders (Hart 1995). Much research investigates the optimum size, composition and characteristics of the board, but it is accepted that firms with dispersed ownership (as typically featured in market listed firms) should have boards that comprise a majority of independent directors. Certainly, despite any choices that firms may make on optimal board composition (Hermalin and Weisbach 2003), many corporate governance codes now make a specific recommendation on board independence composition.

As to how women directors can positively influence firm performance under the expectations of agency theory, for example, whether female directors are “better” monitors, is a matter of much conjecture in the literature. Using agency theory as the perspective, gender should not matter to board tasks (Nielsen and Huse 2010). The arguments can at most be indirect. Adams and Ferreira (2009, p. 292) suggest that “because they [female directors] do not belong to the ‘old boys club’, female directors could more closely correspond to the concept of the independent director emphasized in theory.” Other studies focus on decision-making tasks and suggest that female directors facilitate communication in decision-making (Bilimoria 2000) or are more risk averse in business decisions (Srinidhi et al. 2011). However, as Carter et al. (2003) point out, these differences may also mitigate effective monitoring if the “diverse” incumbents are marginalised on the board. As the literature we rely on is ambivalent in its expressed prior expectations, we do not hold a strong prior expectation. Rather, the question as to gender diversity and financial impact is motivated by the regulatory stance. More direct prior evidence on gender diversity and financial performance, predominantly based on firm-level analysis, is presented below.

Relation Between Gender Diversity and Firm Performance

Evidence of a direct association between a firm’s financial performance and its board’s diversity profile remains elusive. As Adams and Ferreira (2009, p. 305) assert: “The literature on diversity also has ambiguous predictions for the effect of diversity on performance.”

A number of recent studiesFootnote 7 that have investigated the question empirically have not found consistent results. Carter et al. (2010) do not find a significant relation between firm performance (Tobin’s Q and ROA) and diverse boards, using a sample of U.S. firms from the S&P 500 index for the period 1998–2002. Conversely, Carter et al. (2003), using a similar sample (Fortune 1000 firms in 1997), find a positive relation between performance (Tobin’s Q) and diverse boards.Footnote 8 In a broader sample (S&P 1500, 1996–2003), Adams and Ferreira (2009) find some evidence of a negative relation between gender diversity and company performance, measured as both the ratio of the firm’s market-to-book value (as a proxy for Tobin’s Q) and ROA.

The studies to date using Australian data are highly constrained by sample size. Bonn (2004) found a positive relation between diversity and market-to-book ratio in a sample drawn from top companies in 1999. In a sample of firms with diverse boards in 2000–2001, diversity was associated with a higher Tobin’s Q (Nguyen and Faff 2007). Wang and Clift (2009) discuss an absence of any statistically significant association between returns and the percentage of women on boards, with diversity data for only 1 year (2003) for the top 500 listed companies, and using ROA, ROE and shareholder return as performance measures.Footnote 9

We note that all these studies were undertaken prior to the ASX’s diversity disclosure requirements and therefore have extremely few firms with women directors. The change in regulation and consequent increase in female director participation justifies a re-examination of the Australian market. Adams et al. (2011) examine director appointments and find that the stock market reacts more favourably to the appointment of women directors than men directors.

We take a slightly different approach from that used by the current literature. Rather than examining diversity at the firm level, we examine the aggregate returns generated by portfolios of firms with diverse boards and compare these both to non-diverse boards (all- male boards), as well as boards with varying degrees of diversity (one woman director on the board, or more than one woman director), and within industry. Taking a higher level, aggregate, approach is appropriate because we are particularly interested in the market regulator’s (high-level) perspective. Essentially, we are investigating whether there is an association between gender diversity and overall market outcomes, not just on specific firm outcomes.

Degrees of Gender Diversity

A gender diverse board has been simply defined as a board with at least one female director (Adams and Ferreira 2009; Campbell and Mınguez-Vera 2008), as this is the easiest proxy to apply, especially given the lack of data (number of firms with women directors) available. However, there is a second-order research question: how diverse does a diverse board have to be for there to be an economic impact? This has been referred to as “critical mass” (Broome et al. 2011), meaning that if there are enough women on a particular board, women are no longer different from other board members: the critical mass of the women directors no longer makes them “outsiders”. When applied to corporate boards, prior research suggests that the critical mass for women directors on a board is three or more (Konrad et al. 2008; Torchia et al. 2011). Note, however, that the latter study was conducted in Norway where there has been a female director quota in place since 2005, hence enough variation in board composition data are available to discriminate this measure. In our study, due to the very low level of female board participation in Australia, such variation in board composition is not observable. We therefore choose to discriminate portfolios as either no women directors, or at least one female director (diversity); then, if there is diversity, whether there is one female director or more than one female director.

Board Diversity and Other Firm-Level Economic Enhancement

A “business case” for diversity can be approached by investigating other associations, typically at the firm level. Studies in accounting examine financial outcomes such as earnings quality (Krishnan and Parsons 2008), earnings management (Srinidhi et al. 2011) and analyst forecast accuracy (Gul et al. 2011) as a function of diverse boards and/or management. There are studies examining more direct economic impact such as board diversity and cost of capital (Gul et al. 2009). Finally, some research focuses on gender diversity effectiveness on board performance, in the sense of board oversight and monitoring (Hillman et al. 2008; Adams and Ferreira 2009).

This study examines a business case for the market regulator—what does the capital market gain from increased gender diversity on corporate boards? The aim of our paper is to determine whether there is, in fact, any association between financial performance and gender diversity, by taking a market-level perspective. Specifically we look at whether having women on a company’s board is correlated with any performance advantage or disadvantage. Of course, it could well be that the regulatory imperative is not about economic performance but another outcome—for example, social legitimacy (companies need to conform to society’s rules, norms, etc.).

Data

Our initial sample comprises all firms listed on the S&P/ASX 300 which broadly represents the largest 300 listed Australian companies. Each month, we extract the constituent list of S&P/ASX 300 firms from Datastream—this allows us to track additions and deletions to the index over our sample period. We extract returns, book-to-market and market values of all stocks listed on the S&P/ASX 300 from Datastream.

We obtain data on companies’ board members from the Boardroom database from Connect4. We verify the Connect4 start and end dates of female board members by checking company announcements on the ASX website.Footnote 10 We match our S&P/ASX 300 list of firms against the available board member information from Connect4, which gives us a final sample of 577 firms over our sample period. As Connect4 data are only available from 2004 onwards, our sample period is January 2004 to September 2011. We use the return on the S&P/ASX 300 as a proxy for the return on the market and extract these data from Datastream. The risk-free rate is proxied by the 90-day bank accepted bill rate from the Reserve Bank of Australia.Footnote 11

Methodology

Portfolio Formation

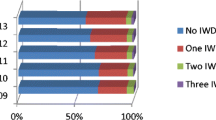

As mentioned above, we investigate the economic impact of gender diversity in a number of ways. We begin by splitting our sample into two groups: firms with all-male boards and firms with at least one woman on their board. We form portfolios of these two groups, as represented in Fig. 1. We also form a difference portfolio (the long/short portfolio), which is long in the firms with women and short in the firms with only men on the board. This is to allow us to clearly determine whether there is a difference in the performance of firms with gender diverse boards and those without. We form both value-weighted and equally weighted portfolios. As already mentioned, we choose to take a portfolio approach because we are interested in the market-level impact of gender diversity. However, forming portfolios also has the added advantage of diversifying firm-specific risk and improving the precision of estimates from regression analysis.

We next investigate whether having more than one woman is associated with differential performance. We consequently split our female portfolio in two depending

upon whether there is one woman or more than one woman on the board, also represented in Fig. 1.Footnote 12 We again compare our portfolio of one woman (more than one woman) to the portfolio of only men by forming a difference portfolio. We also compare whether there is a difference in the returns of the two female portfolios, i.e., we create a difference portfolio between the one-woman and more-than-one-woman portfolios.

Finally, prior research (for example, Brammer et al. 2007) has identified that women may be more value-relevant in some industries than others.Footnote 13 We investigate this proposition by forming portfolios comparing firms with only men on the boards to firms that have at least one female board member within industry using the ten Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB) industry classifications.

Empirical Framework

Our aim is to determine whether gender diversity is associated with financial performance. We use a number of widely accepted performance models to address this question. First, we use a one-factor model as follows:

where \( R_{{{\text{p}},t}} \), \( R_{{{\text{m}},t}} \) and \( R_{{{\text{f}},t}} \) are the returns on portfolio p, the market portfolio and the risk-free asset in month t, respectively.

A significantly positive (negative) alpha on our long/short portfolios will indicate that gender diversity is correlated with an increase (decrease) in risk-adjusted performance.

It is possible firms that choose to have women on their boards may differ from those that do not in terms of their size, book-to-market ratios and momentum exposures. Specifically, larger firms may be more likely to hire women as they may face external pressure to behave in a socially acceptable way (Farrell and Hersch 2005), and have the resources to do so. As these factors have been shown to impact returns, it is important that we control for them when investigating our portfolios. Consequently, we also perform the analysis using a four-factor model:

where \( R_{{\rm p,t}} \), \( R_{{\rm m,t}} \) and \( R_{{\rm f,t}} \) are as above and SMBt, HMLt and UMDt are the monthly return on the mimicking size, book-to-market and momentum factors.

We form size (SMB), book-to-market (HML) and momentum (UMD) factors in line with Fama and French (1993) and Carhart (1997). However, due to differences in the Australian and U.S. tax systems, portfolios are formed in December of year t − 1, rather than in June, and held for 12 months (see also Gharghori et al. 2009). Each December, stocks are ranked on their market value and classified as small or big depending upon whether their market value is smaller or larger than the median market value. Independently, stocks are ranked on their book-to-market ratio and classified as either value, growth or neutral, with breakpoints at the 30th and 70th percentile. Stocks with negative book values are deleted. SMB is then calculated as the value-weighted average return on the small portfolios (small value, small neutral and small growth) minus the value-weighted average return of the big portfolios (big value, big neutral and big growth). Similarly, HML is the average return of the high book-to-market portfolios (big high and small high) minus the average return of the low book-to-market portfolios (big low and small low). UMD is formed in a similar way. At the end of December of year t − 1, stocks are ranked on their prior 1-year return and classified as up or down, using the 30th and 70th percentile breakpoints. We use the same size classifications as before. UMD is calculated as the average return of the up portfolios (small up and big up) minus the average return of the down portfolios (small down and big down).

Results and Analysis

As a useful snapshot of the gender diversity profile of the boards of firms listed on the Australian capital market, Table 2 presents descriptive statistics. Over the 8-year duration of the sample representing the S&P/ASX 300, there was an average of 287 firms (max 294; min 282). Panel A shows that the percentage of the sample with at least one female director fluctuates between 36 and 46 % and peaks in the last year, 2011, at 52 %.

We are also interested in whether diversity can be differentiated beyond a point of one female director, and the data show that firms with two female directors fluctuate around 10 % of the sample (except for 2011 where the level is 17 %). The sample thins considerably beyond more than two female directors.

In Panel B we report the raw returns on our initial portfolios of all-male boards, boards with at least one woman, and the market factors. The table shows that on an equally weighted basis, the female portfolio underperforms, but the means of the value-weighted returns are similar. However, neither of these differences is statistically significant: the p values on the paired t tests between means (and Wilcoxon text between medians) are all above 0.30 for both the equally weighted and the value-weighted portfolios.

Panel C shows the industry breakdown of the sample. It is clear from the panel that boards with at least one female director are concentrated in particular industries. The majority of firms in consumer services, financials and telecommunications have at least one woman on their boards. However, firms in basic materials are clearly dominated by all-male boards. It must be noted that some industries, particularly telecommunications, utilities, and technology comprise very few firms. These small sample sizes need to be considered when we interpret results from portfolios formed within these industries.

Table 3 presents regression results from portfolios of firms with all-male boards compared to firms with at least one female board member. We are mainly interested in the long/short portfolio results because these indicate whether there are significant differences between the portfolios. The alphas on the long/short portfolios are insignificant, meaning there is in fact no correlation between having women on a firm’s board and returns. This result is upheld regardless of whether we use the one- or four-factor model or whether we value-weight or equally weight the portfolios.

The long/short portfolios’ coefficients on the market factor are significantly negative, which suggests that firms that hire women tend to be of lower risk. We could perhaps argue that perhaps the types of firms that hire women are older, more established firms. In terms of loadings onto the four factors, we see a significant negative loading on the SMB factor for the long/short portfolios. This indicates it is larger firms that tend to have women on their boards. Perhaps this is to be expected: larger firms are more likely to face external scrutiny and therefore feel pressurised to take socially acceptable actions. Further, these firms are likely to have the resources to do so. The HML factor is significantly positive in the value-weighted portfolios. This demonstrates that firms with women on boards tend to be “value” firms. We could argue that value firms are more established firms that again may be expected to be able to afford diversity. Coefficients on UMD are insignificant: having women on boards does not appear to be related to prior stock performance.Footnote 14

Does Having Many Women Matter?

In Table 4 we divide our female portfolio into firms with one woman versus those with more than one woman on the board. In terms of differences between all-male boards and boards with women, we again do not find any significant alphas: there is no difference in the performance of boards that have or do not have women. However, we are interested in whether there is a relationship between having one or more than one woman on the board and returns. We find weak evidence in our four-factor value-weighted results that firms with more than one woman have lower returns than firms with one woman on the board. However, we note that this finding is only significant at the 10 % level and is not consistent across all our tests. Our other long/short portfolios do not display a significant difference in the returns of firms with one versus more than one woman on the board.

Firms with more than one woman on the board are larger and tend to have more of a value tilt than firms with only one woman on the board. This may again indicate that firms that are more established are able to appoint more women to their boards than other firms. The betas on the two portfolios are not significantly different.Footnote 15

Does Industry Matter?

We investigate whether there is a correlation between gender diverse boards and returns across different industries because prior research has identified that having female board members is more valuable in some industries than in others (see Brammer et al. 2007). Results are in Table 5. For brevity, we present only results from the four-factor model using value-weighted portfolios.Footnote 16

Focusing on the long/short portfolios, we see weakly significantly positive alphas on basic materials and consumer goods. It seems that in these two industries having at least one woman on the board is associated with higher returns.Footnote 17 However, for all eight other industries, we do not find any correlation between having gender diverse boards and returns: all the other alphas on the long/short portfolios are insignificant.

The long/short portfolios’ coefficients on the size factor are uniformly negative, albeit not always significant.Footnote 18 This again highlights the fact that the larger firms appoint women to their boards. Long/short portfolios’ loadings onto the other factors (market, book-to-market and momentum) are not as homogenous, with some positive and some negative.Footnote 19

Caution needs to be exercised when interpreting some of the industry results, however. A number of the industries comprise very few firms, and dividing firms further into those with and without women board members can drastically reduce the number of firms in each portfolio. This is particularly true of technology and telecommunications, where there are some months with no observations in either the female or the all-male portfolio. Results from basic materials, financials, industrials and consumer services are robust, however, as these portfolios comprise at least ten firms in any given month.Footnote 20

Robustness Tests

In our main analysis, we form portfolios of firms with and without women, as we believe this methodology best demonstrates whether gender diversity provides higher returns at the aggregate (market) level—as suggested by the market regulator. This approach is perhaps unusual in the corporate governance literature and therefore for robustness we also perform the analysis in a panel setting.Footnote 21 In this case, we need firm-specific variables which are only available on an annual basis.

We perform the analysis in two ways. First, we follow Ahern and Dittmar (2012) and regress industry-adjusted Tobin’s Q against the proportion of women on the board as the only independent variable, as well as time and period fixed effects. We also investigate return on assets as the dependent variable. Results (not displayed, available upon request) show that in each case, the coefficient on the proportion of women is insignificant.

We next perform an analysis similar to Adams and Ferreira (2009) and regress the log of Tobin’s Q against: proportion of women, board size, log revenue and the proportion of non-executive directors. We follow those authors and perform the regression in three ways: OLS, firm fixed effects and then use an Arellano and Bond (1991) dynamic panel model (i.e. including a lag of log Tobin’s Q). Our results (not displayed, available upon request) are similar to Adams and Ferreira (2009): the coefficient on the proportion of women variable is insignificantly positive using OLS, but significantly negative using firm fixed effects and using a dynamic panel model. As discussed in Adams and Ferreira (2009), these disparities in results highlight the necessity of correct model specification that allows for potential endogeneity. We also use return on assets as the dependent variable and in this case the coefficient on the proportion of women is insignificant in all specifications.

We conclude, then, that our robustness tests overall uphold our main results: we do not find a relation between having one or more women on the board and performance.

Discussion and Conclusion

The global regulatory interest in board gender diversity as a corporate governance best practice guideline has escalated over the last few years. Regulatory interest can manifest as mandatory board quotas (for example, Norway), to recommend and disclose regimes (for example, Australia and the UK) to regulators who lag global practice (for example, Canada and the U.S. which are as yet to address the issue). This provides a range of environments for researchers to study whether there is an association between diversity initiatives and firm value or outcomes. Most of the market-based research referred to herein emanates from either the mandatory environment (Norway) or the unregulated environment (U.S.). There is literature from other disciplines that uses other evidence, such as surveys and interviews, to examine the firm-level impacts of diverse boards.

This study is set in the Australian market because it has recently introduced a “soft” regulatory approach—a recommendation that listed firms establish a gender diversity policy and disclose their performance and achievements against their adopted policy. Hence, the environment is not mandatory, but creates strong external pressure to conform. Second, rather perplexingly, the Australian market operator has motivated its stance by claiming the “business case”—that diversity is linked to performance. However, despite several studies investigating this problem, a conclusive link between firm performance and gender diversity has not been established.

We use a different methodology from prior literature and take a portfolio approach to the question. This aggregate approach more appropriately reflects the high-level view relevant to the regulator. One shortcoming of our study is one common to many studies reported herein—the extremely small proportion of women on Australian boards and, consequently, the low number of firms with female board members available. We have been able to ameliorate this constraint to some extent by using a portfolio approach. However, to investigate the degree of diversity, we are only able to discriminate between diversity meaning one female director, compared to diversity being more than one female director. The descriptive data show that the percentage of boards with two female directors is around 10 % for most of our sample period, but beyond that point (three or more women) the sample thins considerably. This constraint may weaken our ability to detect whether gender diversity truly has a financial impact (it could be that larger numbers of female directors on boards are necessary for real “change”), but perhaps demonstrates why the market regulator has chosen to intervene in this area.

There are several industry reports that narrate the raw data on board composition in the Australian capital market. We are able to confirm that the percentage of diverse boards (at least one female director) in the top 300 firms fluctuates around 36–46 % and peaks in 2011 (the first year after the corporate governance regulation) at 52 %. As expected, there are industry clusters, but the industry clusters may be hard to predict.Footnote 22 We find the majority of diverse boards in the top 300 firms are in the consumer services, financials and telecommunications industries.

Overall, we do not find a strong business case for gender diversity on boards. Regardless of whether we use a one- or four-factor model, we find no difference in the performance of gender diverse and all-male board portfolios. However, we find weak evidence (significant in one of our models only) that more than one woman on a board is associated with lower returns. The absence of strong return results is informative to the market operator; it confirms that it is difficult to find evidence of an economic argument for diversity using market data.

However, the study also contributes in terms of empirical evidence to support other value-relevant propositions about diverse boards: we find larger firms with lower risk tend to have diverse boards, and it is the very large firms that are able to have more than one female director. This suggests that firms that are established can “afford” diverse boards. Further, there is weak evidence that having at least one female director is correlated with higher returns for the basic materials and consumer goods industries.

Our findings suggest that in a non-mandated environment, evidence of a link between diverse boards and financial returns is elusive. A diverse board may be one corporate governance mechanism that a firm can “trade up” to for a range of complex societal reasons or stakeholder expectations, but neither firms nor the regulator should expect diversity to be associated with increased stock returns. Of course, this study has cited a selection of studies from a variety of disciplines and it may well be that gender diversity is not solely a “business case” but a “buy-in” for a range of reasons. The nature of these alternative motivations for gender diverse boards is an interesting empirical question that we leave to future research. Given the potential suite of non-financial motives, we would predict that the absence of market evidence would not preclude a move to a more mandated approach to the appointment of women to corporate boards.

Notes

Australian Securities Exchange (2010), Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations with 2010 amendments. Available at http://www.asxgroup.com.au/media/PDFs/cg_principles_recommendations_with_2010_amendments.pdf. Accessed 16 November 2012.

Ibid; Financial Reporting Council (2012), The UK Corporate Governance Code. Available at http://www.frc.org.uk/getattachment/a7f0aa3a-57dd-4341-b3e8-ffa99899e154/UK-Corporate-Governance-Code-September-2012.aspx. Accessed 19 November 2012.

Australian Human Rights Commission (2010) Gender Equality Blueprint 2010. Available at http://www.humanrights.gov.au/sex_discrimination/publication/blueprint/. Accessed 16 November 2012.

The AICD reports that in 2007 and 2008, the new appointments to boards who were female comprised 8% of appointments. In 2009, 5%, 2010, 25%, 2011, 28% and in 2012 it was 24%. The sample population reported by the AICD comprises the S&P/ASX 200 (top 200 listed Australian companies). Our sample comprises the S&P/ASX 300 (see http://www.companydirectors.com.au/Director-Resource-Centre/Governance-and-Director-Issues/Board-Diversity/Statistics. Accessed 14 March 2013).

Australian Securities Exchange (2010), op cit.

http://ir.wesfarmers.com.au/phoenix.zhtml?c=144042&p=irol-reportsannual. Accessed 19 November 2012.

Although the studies are recent, the datasets are from the prior decade.

Note both of these studies measure diversity as gender and ethnicity.

The authors define ROE as the ratio of profit after interest and tax to book value of equity, whereas shareholder return is the ASX realised rate of return adjusted for dividends and splits.

http://www.asx.com.au/asx/statistics/announcements.do. Accessed 13 December 2012.

http://www.rba.gov.au/statistics/tables/index.html#interest_rates. Accessed 12 June 2012.

Panel A of Table 2 clearly demonstrates that it is not possible to disaggregate further on the number of women, since the vast majority of boards have only one or two women.

Note that Brammer et al. (2007) study is based on a UK sample.

For robustness we also investigate the period prior to the ASX recommendations. As discussions about this recommendation were already occurring in early 2009, we investigate the sample prior to 2008. We rerun all regressions using the sample period January 2004 to December 2008. Results (not displayed, available upon request) are qualitatively identical. Alphas on the long/short portfolios are insignificant and firms that have women on their boards are larger, value firms but do not load onto momentum.

We rerun the analysis using the period January 2004 to December 2008. Alphas on the long/short portfolios are uniformly insignificant. We do not find the size effect in the value-weighted long/short portfolio but still find a significant value effect.

Other results available upon request.

The alphas on the long/short consumer goods portfolios are significantly positive across all models although the alpha on basic materials is not significant in other specifications. The equally weighted alphas on consumer services (telecommunications) are significantly negative (positive) across the equally weighted portfolios. However, given that this result is not upheld in the value-weighted models, this may be attributable to some poorly (over-) performing small firms in that sector.

Coefficients on the size factors are similarly predominantly negative on the equally weighted portfolios.

Results for the January 2004 to December 2008 are similar with most industries having insignificant alphas on the long/short portfolios. However, we do find outperformance in financials and healthcare and underperformance in industrials. Coefficients on SMB are negative in the majority of the cases.

Both the all-male and the female consumer goods portfolios have a minimum of four firms in a particular month.

We thank an anonymous referee for this suggestion.

Adams et al. (2011) use government data from the Equal Opportunity for Women in the Workplace Agency to predict that high participation rates in the workforce may affect diversity, so that finance has a high workplace participation, whereas the natural resources sector is male-dominated.

References

Adams, R., & Ferreira, D. (2009). Women in the boardroom and their impact on governance and performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 94(2), 291–309.

Adams, R., Gray, S., & Nowland, J. (2011). Does gender matter in the boardroom? Evidence from the market reaction to mandatory new director announcements. Working Paper, University of Queensland.

Ahern, K., & Dittmar, A. (2012). The changing of the boards: The impact on firm valuation of mandated female board representation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127(1), 137–197.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

Australian Institute of Company Directors. (2012). Appointments to ASX200 Boards.

Bilimoria, D. (2000). Building the business case for women corporate directors. In R. J. Burke & M. C. Mattis (Eds.), Women on corporate boards of directors: International challenges and opportunities (pp. 25–40). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Bonn, I. (2004). Board structure and firm performance: Evidence from Australia. Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Academy of Management, 10(1), 14–24.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Pavelin, S. (2007). Gender and ethnic diversity among UK corporate boards. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(2), 393–403.

Broome, L. L., Conley, J. M., & Krawiec, K. D. (2011). Does critical mass matter? Views from the boardroom. Working Paper, University of North Carolina.

Broome, L. L., & Krawiec, K. D. (2008). Signaling through board diversity: Is anyone listening? University of Cincinnati Law Review, 77(1), 446–447.

Burke, R. (1997). Women on corporate boards of directors: A needed resource. Journal of Business Ethics, 16(9), 909–915.

Campbell, K., & Mınguez-Vera, A. (2008). Gender diversity in the boardroom and firm financial performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(3), 435–451.

Carhart, M. M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. Journal of Finance, 52(1), 57–82.

Carter, D., D’Souza, F., Simkins, B., & Simpson, W. (2010). The gender and ethnic diversity of US boards and board committees and firm financial performance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 18(5), 396–414.

Carter, D., Simkins, B., & Simpson, W. G. (2003). Corporate governance, board diversity, and firm value. Financial Review, 38(1), 33–53.

Fairfax, L. (2011). Board diversity revisited: New rationale, same old story? North Carolina Law Review, 89(1), 855–886.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33(1), 3–56.

Farrell, K. A., & Hersch, P. L. (2005). Additions to corporate boards: The effect of gender. Journal of Corporate Finance, 11(1–2), 85–106.

Gharghori, P., Lee, R., & Veeraraghavan, M. (2009). Anomalies and stock returns: Australian evidence. Accounting and Finance, 49(3), 555–576.

Gul, F. A., Chung-ki, M., & Srinidhi, B. (2009). Gender diversity on U.S. corporate boards and cost of capital. Working Paper, Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Gul, F. A., Hutchinson, M., & Lai, K. (2011). Gender diversity and properties of analyst earnings forecasts. Working Paper, Monash University.

Hafsi, T., & Turgut, G. (2013). Boardroom diversity and its effect on social performance: Conceptualization and empirical evidence. Journal of Business Ethics, 112(2), 463–479.

Hart, O. (1995). Corporate governance: Some theory and implications. The Economic Journal, 105, 678–689.

Hermalin, B. E., & Weisbach, M. S. (2003). Boards of directors as an endogenously determined institution: A survey of the economic literature. FRBNY Economic Policy Review, 9(1), 7–26.

Hillman, A. J., Nicholson, G. J., & Shropshire, C. (2008). Directors’ multiple identities, identification, and board monitoring and resource provision. Organization Science, 19(3), 441–456.

Konrad, A. M., Kramer, V. W., & Erkut, S. (2008). Critical mass: The impact of three or more women on corporate boards. Organizational Dynamics, 37(2), 145–164.

Krishnan, G. V., & Parsons, L. M. (2008). Getting to the bottom line: An exploration of gender and earnings quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(1–2), 65–76.

Nguyen, H., & Faff, R. (2007). Impact of board size and board diversity on firm value: Australian evidence. Corporate Ownership and Control, 4(2), 24–32.

Nielsen, S., & Huse, M. (2010). The contribution of women on boards of directors: Going beyond the surface. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 18(2), 136–148.

Ryan, M., & Haslam, S. A. (2005). The glass cliff: Evidence that women are over-represented in precarious leadership positions. British Journal of Management, 16(2), 81–90.

Srinidhi, B., Gul, F. A., & Tsui, J. (2011). Female directors and earnings quality. Contemporary Accounting Research, 28(5), 1610–1644.

Terjesen, S., Sealy, R., & Singh, V. (2009). Women directors and corporate boards: A review and research agenda. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(3), 320–337.

Torchia, M., Calabro, A., & Huse, M. (2011). Women directors on corporate boards: From tokenism to critical mass. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(2), 299–317.

Wang, Y., & Clift, B. (2009). Is there a “business case” for board diversity. Pacific Accounting Review, 21(2), 88–103.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Nowland, Emma Schultz, Tom Smith, Garry Twite and workshop participants at the Australian National University for helpful comments. We also thank Chen Cheng and Theingi Oo for research assistance. We thank Susan McCreery for proofreading the manuscript. We acknowledge the Accounting and Finance Association of Australia and New Zealand for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chapple, L., Humphrey, J.E. Does Board Gender Diversity Have a Financial Impact? Evidence Using Stock Portfolio Performance. J Bus Ethics 122, 709–723 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1785-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1785-0