Abstract

Shareholder activism has become a force for good in the extant corporate governance literature. In this article, we present a case study of Nigeria to show how shareholder activism, as a corporate governance mechanism, can constitute a space for unhealthy politics and turbulent politicking, which is a reflection of the country’s brand of politics. As a result, we point out some translational challenges, and suggest more caution, in the diffusion of corporate governance practices across different institutional environments. We contribute to the literature on corporate governance in Africa, whilst creating an understanding of the political embeddedness of shareholder activism in different institutional contexts—i.e. a step closer to a political theorising of shareholder activism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

To what extent is local shareholder activism a reflection of a country’s brand of politics? Shareholder activism has continued to grow with the globalisation of markets, as a force for good (Becht et al. 2009). It mainly operates on the premise that shareholders, as activist owners, can check managerial opportunistic tendencies and, thus, promote effective corporate governance (Black 1992; Gillan and Starks 1998, 2000; Rubach and Sebora 2009). The last two decades has been particularly remarkable in this regard, with activist shareholders pressurising the management of poorly performing firms in their portfolios for improved performance and enhanced shareholder value (Gillan and Starks 2000). Despite the positive perception of shareholder activism, it is still controversial in many ways. Becht et al. (2009), for instance, argued that whilst it can resolve the monitoring and incentive problems associated with widely held firms, in order to improve their performance (Black 1992), it can also constitute a disruptive, opportunistic, and ineffective mechanism employed by fund managers and other investors for personal benefits. This further suggests that shareholder activism is capable of constituting a space for struggles and contestations of interests—i.e. a space for politics and politicking—which is characteristic of most political projects.

Unsurprisingly, the Anglo-Saxon construction of markets, upon which most of the shareholder activism literature is based on, is fundamentally predicated on the neo-liberal conception of democratic politics and its antecedent institutional arrangements, wherein agents are free and have the rights to exercise and exert their property rights within legitimate institutional boundaries. Particularly, shareholder activism, as an important characteristic of these financial markets, is also underpinned by the same neo-liberal ideology. Moreover, the extant literature on shareholder activism appears to take this understanding of shareholder activism within legitimate neo-liberal institutional boundaries for granted; to the extent that very little is known about the possible influences of a country’s political stage of democracy on the practice of corporate democracy, in general, and shareholder activism, in particular. However, some recent developments in the broad literatures on governance and institutions suggest that corporate governance is a function of specific institutional configurations (Aguilera and Jackson 2003; Aguilera 2005), which calls for a good understanding of the politics of corporate control (Thompson and Davis 1997), as well as an encompassing understanding of the political environment in which markets and corporate governance mechanisms are enacted (Roe 1994, 2003; Bainbridge 1995; Gourevitch and Shinn 2005; Wärneryd 2005; Coglianese 2007; Belloc and Pagano 2009), to make sense of shareholder activism in different institutional contexts.

In this article, we are more concerned with the political environment or political culture of a nation state rather than the administration of democracy, given that the term ‘democracy’ connotes different meanings in different parts of the world and should not be used to imply a ‘clean/corrupt-free’ political environment. Indeed, our study provides insights into how a ‘dirty/corrupt-ridden’ political environment combined with the lack of effective (regulatory) institutions can create a context where shareholder activism can have a deleterious effect on business. Our aim, therefore, in this article, is to explore the possible link between shareholder activism in Nigeria and the political culture of the country.

However, the choice of Nigeria is not arbitrary. The recent and current developments in the country have added an energetic momentum to the corporate governance and shareholder activism debates. These include the 2003 Code of Corporate Governance in Nigeria (hereinafter referred to as the SEC Code); the 2006 mandatory Code of Corporate Governance for Nigerian Banks post consolidation (hereinafter referred to as the CBN Code); and most importantly the 2007 Code of Conduct for Shareholder Associations in Nigeria (hereinafter referred to as the SEC Code for shareholders). Specifically, Nigeria has witnessed a significant increase in the number and activities of shareholder associations in the past 5 years, and as a result, shareholders are becoming increasingly aware of their rights and responsibilities. In addition, the peculiarities of Nigeria’s turbulent political history and political uncertainties provide a rich outlook to show how an evolving corporate governance mechanism (in this case, shareholder activism) thrives amidst the broader political environment of a country. Whilst this enables us to understand the relationship between shareholder activism and the state of democracy/political culture of a nation state, it also allows us to explore how the practice of shareholder activism in the country reflects (or do not reflect) the characteristics of the Nigerian political culture.

As a result, we aim to make a bilateral theoretical contribution. First, our findings augment the literature on corporate governance in Africa, which suffers from a comparative dearth. This dearth of literature is further felt in relation to the link between corporate governance practices and the political culture of sub-Saharan African countries. Second, we attempt to contribute to the literature on the institutional configuration of corporate governance, by presenting evidence from a ‘developing country’ to explore the link between national political culture and the expression of shareholder activism. In this vein, whilst the rising unlimited potential for expanding the shareholder activism literature in developing countries (Sarkar and Sarkar 2000; Amao and Amaeshi 2008) can be positively perceived, it has become necessary to examine the surrounding institutionalised political environments of these countries, and particularly their effects.

We therefore examine these fundamental concerns and focus on the politics of shareholder activism as a control mechanism for corporate governance and accountability in Nigeria. We take into account the relevant institutional arrangements—mainly the political culture—and explore how these constrain the necessity and practice of shareholder activism in Nigeria. This article proceeds as follows. We first present a review of the relevant literature and thereafter examine the Nigerian political climate. These provide a background for our subsequent exploration of the state of corporate governance in Nigeria. We then outline our research agenda and methodology, discuss our findings and present our conclusions.

Shareholder Activism: A Literature Review, Theoretical Development and Research Agenda

Discussions on corporate governance are often closely linked to the problem created by the separation of a firm’s ownership from its control. Jensen and Meckling (1976) posit that the incentives of managers to maximise shareholder value are proportional to the fraction of the firm’s shares they personally hold (Bradley et al. 2000). Corporate governance can therefore be defined as the ‘legal and practical system for the exercise of power and control in the conduct of the business of a corporation, including in particular the relationships amongst the shareholders, the management, the board of directors and its committees, and other constituencies’ (Grienenberger 1995, p. 875). Corporate governance thus embodies the tussles between managers of public companies and their owners, over the productive level of shareholder involvement in corporate policy and administration (Schacht 1995). Some of these tussles are sometimes expressed through shareholder activism.

Shareholder activism can, therefore, be described as a corporate governance (managerial/board) accountability mechanism. It consists of the activities undertaken by shareholders in connection with the contestations between managers of public companies and their owners (Schacht 1995). It further entails the act of monitoring and attempting to effect changes in the organisational control structure of firms by shareholders (Smith 1996). Shareholder activism, thus, refers to a range of actions taken by the shareholder(s) to influence management and the board; these actions are normally categorised as either an exit (selling shares) or voice (letter writing, meetings with management and the board, forming shareholder associations, asking questions at shareholder meetings and the use of voting rights) (Becht et al. 2009). Most commonly, a shareholder activist can be described as an investor who tries to change the status quo through ‘voice’ without resulting into a change in a firm’s control (Gillan and Starks 1998).

Shareholder activism is not a homogenous practice, but comes in various guises. It is driven by different actors and interests, and has different impacts on target firms. The literature on comparative shareholder activism shows that there are wide-ranging rationales for shareholder activism in different countries. It is therefore important to study shareholder activism in the light of the peculiarities of each country. For instance, in the case of India, Sarkar and Sarkar (2000) present shareholder activism as a valued mechanism for corporate governance. They provide evidence on the role and importance of large shareholders in monitoring firm value. However, their results contained mixed evidence. They found results to suggest that whilst significant block-holdings by directors increase firm value, the impacts of institutional investors as activists are unclear.

The findings of Sarkar and Sarkar (2000) can be compared to the work of Hendry et al. (2007) who used interview data to explore the shareholder activism practice of UK institutional investors. Contrary to a large number of studies on shareholder activism, which mainly assume that it is always born out of the desire to maximise shareholders’ wealth, they found evidence of alternative motivations relating to ideas of responsible ownership. This suggests that recognising the motivations behind shareholder activism is imperative to a clearer understanding of its impacts. This will necessitate a thorough account of the institutional rationalisations which underlie the ideology, necessity, structure, practice and eventual impacts of shareholder activism. It is thus important that corporate governance discussions reflect a broader perspective of institutional domains (Aoki 2001), and the literature is responding to this insight (see, for example, Aguilera and Jackson 2003; Aguilera 2005; Lubatkin et al. 2007). We suggest that institutional accounts shed necessary illumination into the evolving institutionalised corporate governance and shareholder activism systems in developing countries, and in particular Nigeria.

The rise of shareholder activism as an important corporate governance mechanism is becoming pervasively documented across many nations. For example, whilst the literature remains dominated by notable works in developed countries, such as in the United States (Thompson and Davis 1997; Gillan and Starks 2007), the United Kingdom (Becht et al. 2009; Crespi and Renneboog 2010), the Netherlands (Choi and Cho 2003), Japan (Seki 2005) and Australia (Anderson et al. 2007), some seminal discourses of the subject have also been generated in emerging economies such as in India (Sarkar and Sarkar 2000). Despite increasing noteworthy works (e.g. Yakasai 2001; Abdel and Shahira 2002; Ahunwan 2002; Rossouw 2005; Okike 2007; West 2009; Adegbite and Nakajima 2011; Adegbite 2012), the deep lacuna in literature on corporate governance and shareholder activism in sub-Saharan Africa is very apparent. This has motivated the current research around the question: to what extent does shareholder activism in Nigeria mirror the country’s brand of politics?

Institutional Context and Empirical Background

This section is mainly to contextualise our study. We first discuss the dominant political culture of Nigeria, and then the legal framework of shareholder activism in Nigeria.

Nigeria, Politics, Political Structure and Culture

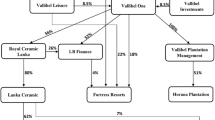

Apart from the massive irregularities which plague political elections in Nigeria, the political structure and culture reflects the country’s legendary corruption. During decades of military rule, corruption thrived and became the Nigerian ‘way of life’. Since Nigeria has traditionally lacked the institutional capacity to address political corruption, the venom has become endemic. The pervasiveness of corruption in Nigeria is corroborated by independent corruption indexes. For example, Transparency International (2010), an anti-corruption non-governmental organisation, ranks Nigeria 134 (same as Zimbabwe and Bangladesh) out of 178 countries in its 2010 corruption perception index. The 178th on the list, being the most perceived corrupt country. Denmark is ranked first on the list. The United Kingdom and the United States of America were ranked 20th and 22nd, respectively. The country ranking of the Transparency International Index is further appreciated through the World Bank Anti-Corruption and Governance Index. The World Bank index is based on six broad measures of good governance: (1) voice and accountability, (2) political stability, (3) government effectiveness, (4) regulatory quality, (5) rule of law and (6) control of corruption (Kaufmann et al. 2008). The graphs in Fig. 1 represent a comparative view of Nigeria, Denmark and the United Kingdom on the World Bank index. It is upon this background that we explore the implications of the corrupt and greed driven Nigerian politics and political culture for business conduct, corporate governance and shareholder activism in particular.

Corporate Governance, Shareholder Activism and the Nigerian Regulatory Environment

Nigeria inherited the British corporate governance system (Okike 2007). The history of corporate governance in Nigeria stretches to the colonial times (Ahunwan 2002), when the Nigerian private sector was dominated by British companies after the British interests (Frynas et al. 2000). Following political independence in 1960, a key economic liberation/development strategy immediately pursued by the Nigerian government was to foster domestic ownership and control of the Nigerian private sector (Akpotaire 2005). The primary statute empowering shareholders in Nigeria to intervene in a company’s affairs is the Company and Allied Matters Act (CAMA) 1990 (as amended). To further enhance the powers of shareholders in the corporate decision-making process, the SEC Code was introduced in 2003. One of the core focuses of the code is shareholders’ rights and responsibilities. For example, the code expressly provides that the company or the board should not discourage shareholder activism whether by institutional shareholders or by organised shareholders’ groups. The code envisages that the general meeting should be a forum for shareholder participation in the governance of the company. The code also provides that a director representing the interests of minority shareholders should occupy a seat on the board. The code further provides for more regular briefings of shareholders, going beyond the half year and yearly reports.

These are efforts by the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to promote shareholder activism and the rights of minority shareholders in the Nigerian corporate governance system (Okike 2007). As a result, the trend in developed economies, which enabled the rise of block voting through shareholder associations as a response to domination by majority shareholders, is gradually evolving in the Nigerian context facilitated by private initiatives and government’s encouragement (Amao and Amaeshi 2008). The Independent Shareholders’ Association of Nigeria (ISAN), the Nigerian Shareholders’ Solidarity Association (NSSA), the Association for the Advancement of the Rights of Nigerian Shareholders (AARNS) are amongst other shareholders’ associations who have evolved in recent times to promote shareholder activism in Nigeria. Despite the nascent and fledging rise of shareholder activism in Nigeria, our interest in this article, however, is to understand and characterise the nature of this emergent phenomenon in Nigeria; and its relationship with the country’s brand of politics.

Research Design, Methodology and Analysis

Research Strategy

This research is part of a larger research project which examined the determinants of good corporate governance in Nigeria (Adegbite 2010). Given the evolutionary state of shareholder activism in Nigeria, and the nature of the research question/study’s objectives, the study adopted a mix of the following qualitative research methods: in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, direct observations and case studies, in order to (1) offer a better understanding of the subject matter (Flick 1992) as they relied on understanding processes, behaviours, and conditions, and (2) determine causal relationships through methods rather than by establishing counterfactuals (Wang 2006). This was very important to provide necessary insights into shareholder activism in Nigeria’s turbulent polity, whilst aiming ‘to describe, decode, translate or otherwise come to terms with the meaning, not the frequency, of certain more or less naturally occurring phenomena in the social world’ (Van Maanen 1979, p. 520). Data were sourced from participants, which included notable corporate governance professionals in academia, in practice and in the Nigerian polity, thus providing data which consist of detailed descriptions of events, situations and interactions between research subjects, in ways which further provided depth and detail (Patton 1980).

Data Collection

Access

Part of the data collection process included a 2 month field work in Nigeria between May and July, 2008. From the outset and throughout the data collection process, 112 key contributors to the corporate governance debate, ranging from the academia, through practice to the regulators in Nigeria were identified and were contacted via e-mails, telephone calls, and in person, outlining the research agenda. The authors are affiliate members of the Society for Corporate Governance in Nigeria and maintain close working relationships with relevant stakeholders in the Nigerian corporate governance system. This helped to alleviate some of the challenges relating to access to data and respondents. Snow-balling technique, as well as third party informants such as academic colleagues who have useful industry links also proved very helpful to gain access to these high-calibre respondent(s) (see also, Amaeshi et al. 2006) until data saturation was reached.

Interviews

Detailed information, which contained questions and issues primary to the study, were sent to potential respondents in order to facilitate their preparation. Lynn et al. (1998) noted that this is a good practice when conducting interviews, as it helps to reduce the amount of efforts required contacting sample members and gaining cooperation. The interview guide (see Appendix) are in line with previous studies (see for example, Filatotchev et al. 2007; Hendry et al. 2007), and were pre-tested to ensure their validity and reliability. The participants were promised confidentiality to encourage uninhibited responses. Therefore, numerical codes (from D1 to D42) have been used to anonymise their identities. This is also the case with responses from focus group respondents. The use of numerical codes further indicates the spread of responses across the entire respondents. Wide-ranging questions were asked in order to gain a variety of responses drawn from real life business and personal experiences free from fear or bias. Sewell (2008) argued that this is a very efficient technique which does not only reduces bias, but also helps to compare the responses of different respondents. The average duration of interviews was 60 min.

Respondents were mainly high profile individuals, including present and former CEOs, Chairmen, board directors, renowned academics, corporate governance consultants, as well as senior officials of the relevant regulatory agencies. Notably these are key stakeholders in the Nigerian corporate governance system. Given their positions, this research benefited from their insider views of the politics of shareholder activism in Nigeria (see also Filatotchev et al. 2007; Aguilera et al. 2008; Hendry et al. 2006, 2007). In order to bring further elements of objectivity and subsequent reliability, a number of Nigerians, but international contributors to the corporate governance debate, were also interviewed. In total, there were 26 in-depth interviews, all face-to-face and tape-recorded. The interviews were subsequently transcribed and analysed.

Focus Groups

The use of focus groups enabled further discussions on shareholder activism in Nigeria and gave additional insights into the overall picture (see also Filatotchev et al. 2007; Aguilera et al. 2008) and the inherent challenges in the country. In order to increase the efficiency of the focus groups and to allow members to expressly discuss the topics of interest without actual or perceived intimidation, the size of the groups were kept small (see Ewings et al. 2008). Certain degrees of overall representation were achieved with participants drawn from different backgrounds and functions, so as to harness a mix of different perspectives. Two separate focus group discussions were held; one had 9 members and the other had 11, totalling 20 respondents. Discussions were also tape-recorded and each of them took an average of 90 min.

The total number of respondents for the interviews and focus group discussions is 42, representing a response rate of 37.5% of the original 112 key contacts. With a 95% confidence level, these figures result in a sample error rate of 12.01%. Tables 1 and 2 consecutively show that a reasonable spread was reached in terms of the professional/disciplinary backgrounds and the institutional expertise/capacities of the experts.

Direct Observations

Furthermore, direct observations were made in order to complement and validate some of the data collected through interviews and focus group discussions. The annual general meetings (AGMs) of two listed corporations were attended and observed. The authors were not granted permissions to tape-record proceedings. Significant note taking of proceedings and interactions, however, constituted helpful alternatives. Attending these AGMs allowed for more access into the complex political relationships, which inform shareholder activism in Nigeria. Indeed this technique gave in-depth insights into ‘what research subjects do, not what they say’ (Wells and Lo Sciuto 1966). Furthermore, direct observation offered a very fast and focused investigation, in such a way that the researcher is watching rather than taking part and become immersed in the entire context (William 2006).

Follow-Up Enquiries Through Case Studies

In addition, the responses from the other research methods were further interrogated by looking deeper into the specific situations and contexts. Two of the major sources of information were documents and archival records. Documents included memoranda, corporate agendas, media reports, and regulatory administrative documents which relate to the governance of listed corporations in Nigeria. Archival records included past companies’ annual reports and accounts, AGM minutes, chairmen’s statements, past regulatory records, amongst others. This further facilitated the triangulation of evidence across different sources in order to understand the politics of shareholder activism in Nigeria.

Data Analysis

The overall research methodology compensated for the weaknesses inherent in individual methods and allowed for a judicious access to key corporate governance experts in Nigeria, with sufficient ‘capacity mix’, which enriched the research data. The data collection techniques employed in this study were to allow for a rich pictorial representation of how the complex Nigerian polity interacts with shareholder activism in the country. Throughout the data collection process, the authors remained flexible and ensured adequate methodological self-consciousness to avoid potential bias in data collection and interpretation. The authors specifically ensured that their functions as researchers and the administrators of the data collection process did not interfere nor affect the data collected, thus minimising negative obtrusiveness and ensuring conceptual flexibility (Glaser and Strauss 1967) and as a result, enhancing both the data-gathering and eventual credibility (Harrington 2002).

Since the overall methodology employed ensured that relevant stakeholders of corporate Nigeria were taken into account, the concerns from all parties became evident. There was a very high degree of agreement amongst respondents’ comments across the various professional/disciplinary backgrounds as well as the different institutional expertises. This facilitated subsequent filtering and collation of results. The interview/focus group guide enabled respondents to broadly discuss issues which led to in-depth comments, beyond the ‘confines’ of the questions asked, thus constituting a rich data on the research topic. It also allowed the identification of specific issues confronting shareholder activism in Nigeria, as well as the means to address them. The principal data analysis technique which was employed used qualitative information based on comparisons and inferences from both secondary and primary data. The data collated helped to identify key themes to explore, and provided the basis for fruitful analysis which gave useful conclusions aimed at advancing tentative propositions, rather than drawing generalised inferences (Child 2002).

The data collection techniques employed generated well over 1,000 pages of texts. These texts were qualitatively analysed. The data analysis was in two phases. The first phase was a pilot, which constituted some familiarisation and random sense making of the data by the authors. This preliminary interpretation of the data suggested some patterns around the nature of shareholder activism in Nigeria as it relates to the national political context. The authors then developed a coding scheme around these emergent themes. The data were analysed with Nvivo 8—a qualitative data analysis software.

Findings

Our data analysis generated, amongst others, two main interrelated themes. We first present our findings on the political analysis of corporate governance, before narrowing down to the practice and politics of shareholder activism in Nigeria.

The State of Corporate Governance in Nigeria: An Institutionalised Political Analysis

Corruption has traditionally been at the centre of governance issues in Nigeria and this appears to have permeated the corporate sector as well. For instance, Nigeria has had a history of a considerable number of high profile and often inconceivable frauds which have been perpetrated by managers and directors of listed corporations. For example, in the early 1990s, the country’s financial sector experienced a major turbulence which resulted in the collapse of several financial institutions, and led to the erosion of investors’ confidence, thus leading to shareholder distrust (ROSC 2004). Whilst the Nigerian banking industry is the most regulated sector on the capital market (in comparison with other sectors such as manufacturing and telecommunications) and can arguably be described as having the most robust corporate governance structure in the country, several corrupt practices and dealings have been perpetrated by managers and directors of listed banks (see Yakasai 2001). The ongoing banking crisis in the country has also been largely attributed to significant corporate governance failures. For example, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has recently dismissed the chief executive officers (CEOs) and executive directors of eight major Nigerian Banks, for bad corporate governance and fraud. Following a preceding CBN audit of banks, they were found to have serious liquidity problems due to several millions of US dollars of unpaid and un-serviced loans by debtors including top business moguls and politicians, as well as other issues bothering on capital adequacy, corporate governance and corruption (Punch 2010). This indicates a corrupt interplay between politicians and corporate management resulting into bad corporate governance practices and fraud. Other recent examples of corporate governance failures include the Cadbury Nigeria accounting scandal of 2007 and the Halliburton scandal in Nigeria of 2008.

Most respondents reported that there is widespread corruption in Nigeria following several political turbulences, coupled with massive institutional shortcomings. Specifically, post-independent Nigerians have lived predominantly within a political environment characterised by military/tyrannical dictatorship, incessant political turbulence and violence, political assassinations and elections marked by massive vote rigging. Post-colonial regime, the government traditionally held significant shareholdings in major areas of the economy. This allowed politicians/political office holders to use government-owned companies to fuel political agendas directly or indirectly via fronts. Respondents unanimously agree that the private sector is gradually becoming the epitome of corruption in Nigeria, given the close relation between the business elites and the political class. This close proximity is often expressed through majority shareholding, which allows politicians to nominate board members and management, and thus influence organisations to suit their political interests; and in other situations use their political powers to the benefits of organisations. Buttressing the prevalence of this connivance between the business and political elites, a former CEO and chairman of a large Nigerian corporation (D3) expressly commented:

Following victory at the polls, politicians upon assuming offices, see themselves as dispensers of favours to individuals, groups or companies who have supported their parties. These supporters get more ‘favours’, ranging from government contracts, fast-tracking of trade licences, whilst denying other qualified individuals or companies, especially if they are perceived as oppositions.

Similarly, another Chairman of a large listed Nigerian corporation (D18) said:

Here, people regard political appointments as ‘licences to become rich’; corporations, especially multinationals, bidding for government’s contracts are left with no choice but to play by the rules of politicians.

Furthermore, given the nature of partisan politics in Nigeria, politicians continuously seek financial support from corporations, which further facilitates public–private corrupt deals. This is heightened by the political culture of corruption and bribery, ethnic tensions and rivalries, poor functioning markets and lack of adequate infrastructure (Ahunwan 2002). It could be reasonably argued that the Nigerian polity strives amidst corruption and very weak legal institutions. It is within this climate that business conduct and corporate governance practices are developing. Particularly, political affiliations matter greatly with regards to how companies secure their businesses and remain competitive (Sun News 2008). To further illustrate this link between politics and the pursuit of corporate interests, the CEO of one of the leading Nigerian breweries was not too long ago allegedly relieved of his duties, when he was caught up in the political lobbying (including the use of corporate resources) that wanted to change the country’s constitution to allow the former President, Mr. Olusegun Obasanjo, for a third term in office (Sahara Reporters 2010).

The Nigerian polity feeds on the premise of deep and complex corruption. In Nigeria, our findings suggest that businesses triumph and remain highly competitive with significant political will and support. It has thus become common for corrupt politicians and ex-office holders to become elected as board members. A focus group participant, who is a non-executive director (D36) of a major Nigerian financial institution, simply puts it as this:

You cannot thrive as a corporation in this country if you do not have a strong politician on your board.

Effective corporate governance is further impeded as they often bring their entrenched public corrupt practices into the private sector. As such, the political embeddedness of the corporate governance system in Nigeria has resulted into a public–private corrupt collaboration. The challenges of corporate governance in Nigeria are, therefore, manifestations of a larger problem of the Nigerian society, which is characterised by political instability, bad leadership, firmly embedded in corruption. Directors’ misconducts and corrupt practices are often at the centre of corporate governance problems in Nigeria, especially in the banking industry. Part of directors’ excesses include lack of disclosure of interests in loans, offices or properties rented/leased or sold to the bank and services provided by own companies to the bank (Vanguard 2007). In Nigeria, corporate governance practices and partisan political considerations intermingle resulting into board and senior-managerial appointments based on political affinities, ethnic loyalties and/or religious faith as opposed to considerations of efficiencies and capabilities (Yerokun 1992; Akanki 1994).

In this regard, ethical standards are often compromised. A good example is the recent conviction of Siemens for bribing a number of senior government officials in Nigeria in order to win telecommunication contracts. However, findings from this study suggest that politically motivated corporate corruption takes different shapes and forms. Unlike Siemens, which seemingly bribed government officials directly, multinationals often pay bribes via ‘consultants’ who negotiate the deal and secure the business/contract. Consultants therefore act as a medium through which the bribe gets to the corrupt government official(s). Whilst commenting on the issue, an academic (and corporate governance consultant) respondent (D24) stated in an interview that:

The case of Siemens is an exception; they were not just smart enough, they wanted to do the bribery themselves, so they got caught.

One can deduce from the preceding analysis of our data that corporate governance in Nigeria mirrors the country’s broader polity which is characterised by endemic corruption. Particularly, as we proceed to show, the findings of this study further suggest that this unhealthy relationship between politics and corporate governance equally finds an expression in the shareholder activism practice in Nigeria.

Shareholder Activism in Nigeria: Practice and Politics

Whilst shareholder activism in Nigeria is still in its developmental stage, the findings of this study suggest an already rapidly evolving institutional misconception and misuse of the term. In particular, it has been noted that shareholder associations sometimes ‘flex their muscles’ to frustrate legitimate operations and the smooth running of the company (Okara 2003). Findings from this study indeed suggest that activist shareholders are gradually being conceived as irritations or terror to normality in corporate organisation and management. The manners through which shareholders’ associations carry out their activisms reflect similar degree of bullying and corruption inherent in the Nigerian political culture. For example, there have been several cases of massive and unwarranted disruptions to AGMs proceedings, perpetrated by executive members of shareholders’ associations. Commenting on this, an interview respondent (D15), who is an executive member of a shareholder association in Nigeria, said:

Some of our members conduct their activities in ways which dent our image and impede our achievements. They go around threatening corporate management with massive AGM disruptions, which normally attracts negative publicity.

As another respondent (D6), an active shareholder activist puts it ‘Aggressive bullying is our weapon’ whilst another activist (D13) noted, in a focus group session, that ‘Some executive members of shareholders’ associations see their positions as an opportunity to enrich themselves, which is typical of Nigerian politicians’.

There is no doubt that the setting up of shareholder associations was encouraged due to the need to coordinate several small, passive and dispersed shareholders; however, the intended activism has been hijacked by individuals whose aims are to reap personal benefits, which is the principal tenet of the broader political culture of the country. In the quest of achieving this, several senior executives of shareholders associations bully corporate management through threats of AGM disruptions and negative media propaganda. Given that shareholders’ associations have become constitutionally empowered to challenge managerial and board excesses, they constitute a great threat to the status quo of traditionally unchecked corporate corruption and governance malfunction, if their powers are applied positively. However, this was not found to be the case. The shareholder associations were rather perceived to be ineffective. According to a non-executive director of a major Nigerian financial institution (D41)

Shareholders associations are not very effective because all their executives want is money. Once you give them some money, they shut up and things continue as usual.

From our study, we found that a corrupt collaboration of engagement between activist/bully shareholders and board/managers has subsequently evolved dynamically to undermine prospects of genuine activism. Indeed, the way dividends are distributed within the corrupt context of shareholder activism in Nigeria constitutes an abuse of what should have been a powerful institutional check on managerial and board behaviour. As such, whilst Okike (2007) as well as Amao and Amaeshi (2008) have documented a huge increase in shareholder activism in Nigeria, more recent evidence suggests that shareholder activism has taken a negative turn in the country. For example, executive members of shareholders’ associations now maintain close and personal relationships with the executives of the firms they are meant to check. This impedes their activism and further enables them to participate in several executive corrupt behaviours, at the detriment of the shareholders they represent. Indeed, several shareholders’ associations have sprung up in recent times and have become powerful lobbying groups that needed to be appeased by management of companies. Our findings suggest that appeasements can occur in several forms—including shares and allotments in public offerings as well as several personal favours, such as funding their organisations and sponsoring their events. As such, AGMs are largely stage-managed. In this regard, a senior official of the Nigerian SEC (D16) said:

We have been attending AGMs where directors are elected or re-elected. Such proceedings are just formalities. Even the so called shareholder associations that attend such meetings are easily compromised by the board and management of these companies.

It must be noted that regulatory agencies have legal provisions to attend AGMs as observers only, with no right(s) to interfere on deliberations. As a senior official of the CAC (D11) also puts it in a focus group session:

Some AGMs are so predetermined that you notice from the onset that this is a doctored proceeding.

In the same vein, a former CEO and Chairman of a listed corporation said (D40):

I acknowledge that management and boards do hijack the independence and activism of shareholder associations, by giving them financial incentives/bribes. It got to a point that a president of one of the shareholder associations became a director on a company which was really bad.

Shareholder activism in Nigeria presents a platform where self-serving individuals can potentially capture rent, at the expense of the corporation. As a result, the extent to which shareholder activism, in itself, can constitute an ‘unwanted problem’ deserves more investigation. In sum, it is possible to posit that corporate governance and shareholder activism in Nigeria are bogus across all sectors of the economy, including the highly regulated banking industry. Currently, shareholder associations seem to go over their activities by becoming post-event/ex-post commentators, displaying false activism when the damage has already been done, such as when companies’ poor performance results are made public, or board corruption exposed, for example by foreign media.

Discussions

Theory

Our findings, in the main, suggest that shareholder activism in Nigeria mirrors the dominant political culture of the country. This finding further brings to the fore the institutional influences on corporate governance in general (Aguilera and Jackson 2003). No doubt, agency theory embodies a different worldview and continues to remain a starting point for building any governance framework (Lubatkin et al. 2007). Indeed whilst its assumptions may be considered restrictive in cross-national application, they nevertheless remain absolutely valid and worthy precursors for conventional orientations towards corporate governance. Clearly, our findings do not disregard the applicability of the highly novel agency theoretical construction of the corporate governance phenomenon. However, they show that whilst economists like Shleifer and Vishny (1997) have considered the model to be a supra-national lens for evaluating all corporate governance issues, this principal/agent model is based on a number of assumptions which may undermine the complexity (Lubatkin et al. 2007) and multi-facet character of the corporate governance phenomenon and consequentially the subject of shareholder activism. Notably, it engenders an under-socialised and under-politicised view of principals and agents, particularly in developing countries and specifically as we have seen in our Nigerian case. In this regard, the institutional account of corporate governance offers a helpful complementary lens to the agency theory of corporate governance.

The political system, as a vibrant institutional force, has been pivotal to the study of institutional effects on corporate governance. In an attempt to move the debate on the institutional determinants of corporate governance forward, we have focused on the particular influence of a key institution—political system and culture—on a key corporate governance and accountability mechanism—shareholder activism. Our findings suggest that national political cultures influence shareholder activism in the private sector. More specifically, our findings have shown the extent to which shareholder activism does mirror the broader political climate of a nation state. Our study adds insights, from a case of a developing country, to the increasing scholarly attentions (Roe 1994, 2003; Coglianese 2007; Belloc and Pagano 2009) being paid to the political determinants of corporate governance.

Again, whilst our study forges a necessary discourse of the particular influence of a country’s political culture on shareholder activism, it encourages further scholarly works in the line of building a political theory of shareholder activism. Therefore, in enriching scholarly discourse in the area of governance and opportunism in the modern corporation, we bring insights from a Nigerian case to add to the increasing scholarly recognition (Aoki 2001; Aguilera and Jackson 2003; Aguilera 2005; Lubatkin et al. 2007; Judge et al. 2008) with regards to the institutional ‘embeddedness’ of countries’ corporate governance systems and key players. This ‘institutionalist’ approach is particularly needed in explaining corporate governance in developing countries, which are characterised by lesser economic development, weakly enforced regulatory infrastructures, as well as public and private corruption.

Following on, the dominant peculiarities of the African business enterprise, particularly the political environment, which is characterised by endemic corruption, creates an avenue to look at corporate governance reforms and regulatory mechanism, less from ‘a one size fits all’ approach. As a result, we advocate more caution in transferring and enacting uniform corporate governance practices across different institutional environments due to the challenge of translating into practice a management system developed in one context in another. Our findings further present the benefits of exploring how corporate governance practices, which appear to be driven by the developed economies, are modified and enacted in different institutional contexts—particularly in developing countries. In other words, the diffusion of a particular model of corporate governance across the globe may suffer from some translational challenges, as one can suggest in the Nigerian context, in relation to an aspect of corporate governance—shareholder activism, which is entangled in corruption. Foreign systems of corporate governance reflect their history, assumptions and value systems (Charkham 1994) which should not be transplanted, but rather, countries should identify the various ways in which the universal principles of good corporate governance can be applied in such a way that it pinpoints and corrects the weaknesses in each country’s particular system and practices (Okike 2007). Attempts aimed at theorising corporate governance mechanisms across the world must therefore account for country-specific challenges, albeit within an umbrella of accepted tenets of responsible corporate behaviour.

Practice and Policy

There is no doubt that true shareholder activism in the broadest sense, involving both large and small individual and institutional shareholders will promote effective corporate governance in Nigeria. Amao and Amaeshi (2008) have recently called for effective shareholder activism as a prerequisite for effective corporate governance and accountability in Nigeria. However, whilst the evolving shareholder activists are a positive development, the corrupt collaboration of shareholders’ associations and corporate executives must also be addressed by regulatory agencies and reputable corporate leaders. This is much needed particularly with the increasing cases of corporate scandals in multinational companies and joint ventures operating in Nigeria. Some visible and highly reported corporate scandals such as the Cadbury Nigeria accounting scandal of 2007, the Halliburton scandal in Nigeria of 2008, and the Siemens bribery scandal of 2009 do little to suggest that foreign majority ownership leads to better corporate governance and accountability. Nevertheless, unlike the traditional principal–agent problem highlighted in the Anglo-Saxon literature, the major agency conflict in developing countries has predominantly being between majority and minority shareholders (Ahunwan 2002).

Following concerns of the SEC over some of the abovementioned corrupt practices of shareholder associations, the SEC Code for shareholders was developed and was launched in December 2007. The code was initiated as an attempt to address observed negative practices of shareholder associations in the Nigerian capital market. Giving background to the new development at the launching of the code, the former Director-General of SEC, Musa al Faki said the code:

Reaffirms SEC’s commitment towards strengthening good corporate governance through the instrumentality of shareholders associations…It will be recalled that the commission embarked on the journey to fashion out the code on April 27, 2006 when an inter-agency committee was set up in response to the observed inadequacies on shareholder associations’ activities. Some of the identified key problems areas that constrained the effectiveness of shareholder associations include: Proliferation of shareholder associations, concerns over behaviour of some members at Annual General Meetings (AGM), intense competition towards getting on companies’ audit committees, governance problems and unclear succession arrangements and the inadequate members enlightenment on shareholders rights, privileges and responsibilities. The rest were lack of regulatory oversight and funding constraints (Sun News 2007, p. 1).

Thus, an important recommendation of the code is that the statutory audit committee of companies must elect members (i.e. non-executive directors) who are not executive members of shareholder’s associations to further reduce the answerability of the latter to the executive management. There is, however, a key institutional impediment to the Nigerian legal infrastructure for corporate governance, particularly with regards to the SEC Code, the CBN Code and the SEC Code for shareholders. This is in relation to the absence of a large pool of potentially qualified candidates with sufficient and desirable human capital to act as truly independent directors and subsequently members of audit committees. As a result, whilst the SEC Code for shareholders is indeed a very timely initiative, our study shows limited evidence to suggest that it has produced significant positive results. We, however, recognise that our study was conducted primarily between May and July 2008; there is now enough time for future studies to be able to look at the impact of the code.

We suggest that genuine shareholder activism will drive good corporate governance in developing countries such as Nigeria. Furthermore, shareholder activism can be promoted through a more informative interaction between shareholders’ associations and corporations. This will have to go beyond yearly AGMs. Increased participation by enlightened shareholder groups and reputable corporate leaders is capable of enhancing this informative interaction. This will facilitate efficient shareholder activism, given that enlightenment is crucial. Furthermore, upon being aware of their rights and responsibilities, Nigerian shareholders will also have to make a decision to be ‘active’ and act on their rights and responsibilities. This would mean taking a step beyond the attendance of AGMs but asking specific questions to ensure sufficient clarity of corporate goals and strategies, as well as scrutinising managements’ and director’s activities.

Furthermore, the Nigerian media can promote responsible shareholder activism by providing unbiased, independent and fact-based information to the investing public. Corporate watch-dogs in Nigeria such as the CAC and the SEC, as well as the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) should rise up to promote the development of a positive shareholder activism culture in Nigeria. This may raise the question as to—why these bodies are not working effectively currently. The self-reinforcing institutionalised political culture of corruption permeates through the country’s infrastructure and therefore, deeper attempts should be made to identify this as a principal cause, and subsequently addressed by a stronger (zero-tolerance for corruption) political will from the top (Federal Government). In relation, the Nigerian government needs to aggressively address public corruption and thereafter engage more strategically with the governance of corporations in ways which promote rewards for performance, dynamism, flexibility and entrepreneurship, and minimise private corruption.

Conclusion

The major thesis of this article is that institutions, and in particular, macro (political) environments influence shareholder activism. Whilst we do not suggest a very strong cause–effect relationship, we have provided some evidence to support the view that a country’s political culture influences its predominant style of shareholder activism, particularly as it relates to the developing economies of the world. We have also shown how shareholder activism can constitute an institutionalised political misuse at the firm level, within a broader national polity ridden with endemic corruption. We further showed the emergence of different institutionalised expressions of shareholder activism, which are contingent on the broader configuration and character of nation state politics. Given that the extant literature on shareholder activism appears to take the ‘positivist’ understanding of shareholder activism within legitimate neo-liberal institutional boundaries for granted, the discussions presented in this article highlight the possible influences of a country’s political stage of democracy on the practice of corporate democracy, in general, and shareholder activism, in particular.

In summary, we note that whilst the concept of ‘corporation’ is alien to the indigenous business practices of pre-colonial Nigeria (Ahunwan 2002), the political environments of developing countries offer an in-depth perspective with regards to the ‘embeddedness’ of corporate governance in a country’s polity. In this regard, managers and directors of large listed firms in Nigeria, conventionally strive to reap maximum benefits from political relationships. The result is an unethical and discouraging investment climate, which further allows politicians and their associates to significantly extend their public powers to the governance of corporations. Nevertheless, the Nigerian government continues to demonstrate commitment to the need to inculcate a culture of honesty and transparency in the public and private sector through the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission (ICPC) and the EFCC.

In today’s environment of global competition for foreign direct investments (FDI) and the globalisation of the Anglo-Saxon model of capitalism, effective and competitive corporate governance structures and mechanisms have become imperative in order for African economies to be integrated into the global market system. In relation, the practice of shareholder activism in Nigeria would have to decouple from the corrupt national polity in order to promote good corporate governance in the country. Our findings particularly create an understanding of the political ‘embeddedness’ of shareholder activism in different institutional contexts. It is further anticipated that our findings will contribute to (as well as encourage other works aiming at) the political theorisation of shareholder activism. This is particularly important to the understanding of corporate governance practices in developing economies, given their often weak political structures and corrupt-ridden political cultures.

At this juncture, it is important to point out some limitations of this study. No doubt the methodology and strategy of this research are in considerable alignment with the evolving literature on corporate governance in developing countries (Yakasai 2001; Ahunwan 2002; Okike 2007; Amao and Amaeshi 2008; Adegbite and Nakajima 2011; Adegbite 2012), where the subject is still burgeoning. In this regard, qualitative methods are well suited to capture and conceptualise the diverse configurations shaping the subject, particularly given the exploratory nature of our research. The mixed-methods strategy and the adequate mix of respondents have further contributed to adequate conceptual grounding whilst adhering to methodologically sound and accurate strategies, in order to make useful methodological (Bartunek et al. 1993) and theoretical contributions. Nonetheless future studies may employ alternative methodologies such as questionnaire surveys in order to further validate or challenge its findings.

Also, it must be noted that this is a Nigerian case study. No doubt this research addresses an important gap in literature by adding to the increasing rich resource materials for future studies on corporate governance (and shareholder activism in particular), especially in sub-Saharan Africa, and has important implications for developing countries in general. However, adequate caution must be exercised in making absolute generalisations, given the contextual dimension of the study. Although, there may appear to be striking resemblances with regards to the general state of African countries, there abound remarkable differences in their histories, economic bases, political systems and situations, laws and ethics, which impact on the conduct of business, the system of corporate governance, and the administration of shareholder activism. Nevertheless, this study offers significant analytical generalisability (Yin 2003). The findings of this study further bring to the fore the benefits of studying the corporate governance systems of less reported economies in the literature, adopting multi-theoretical lenses, given their conceptual and practical implications for a global theory and discourse on corporate governance. We hope that this article will modestly fill an important gap in literature as well as encourage further research into corporate governance developments in other African jurisdictions where the subject is even at a more ‘infant’ state.

References

Abdel, S., & Shahira, F. (2002). Corporate governance is becoming a global pursuit: What could be done in Egypt? International Journal of Finance, 14(1), 2138–2172.

Adegbite, E. ( 2010). The determinants of good corporate governance: The case of Nigeria. Doctoral thesis, Cass Business School, City University, London.

Adegbite, E. (2012). Corporate governance regulation in Nigeria. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, Forthcoming.

Adegbite, E., & Nakajima, C. (2011). Corporate governance and responsibility in Nigeria. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance, 0(0), 1–20.

Aguilera, R. V. (2005). Corporate governance and director accountability: An institutional comparative perspective. British Journal of Management, 16, S39–S53.

Aguilera, R. V., Filatotchev, I., Gospel, H., & Jackson, G. (2008). An organizational approach to comparative corporate governance: Costs, contingencies, and complementarities. Organization Science, 19(3), 475–492.

Aguilera, R. V., & Jackson, G. (2003). The cross-national diversity of corporate governance: Dimensions and determinants. Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 447–465.

Ahunwan, B. (2002). Corporate governance in Nigeria. Journal of Business Ethics, 37, 269–287.

Akanki, E. O. (1994). Company directors’ responsibility. In Ahunwan, B. (2002). Corporate governance in Nigeria. Journal of Business Ethics, 37, 269–287.

Akpotaire, V. (2005). The Nigerian indigenization laws as disincentives to foreign investments: The end of an era. Business Law Review, 3, 62–68.

Amaeshi, K. M., Adi, B. C., Ogbechie, C., & Amao, O. O. (2006). Corporate social responsibility in Nigeria: Western mimicry or indigenous influences? Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 24(Winter), 83–99.

Amao, O., & Amaeshi, K. (2008). Galvanising shareholder activism: A prerequisite for effective corporate governance and accountability in Nigeria. Journal of Business Ethics, 82(1), 119–130.

Anderson, K., Ramsay, I., Marshall, S., & Mitchell, R. (2007). Union shareholder activism in the context of declining labour law protection: Four Australian case studies. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(1), 45–56.

Aoki, M. (2001). Towards a comparative institutional analysis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Bainbridge, S. M. (1995). The politics of corporate governance. Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy, 18(3), 671–735.

Bartunek, J. M., Bobko, P., & Venkatraman, N. (1993). Toward innovation and diversity in management research methods. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1362–1373.

Becht, M., Franks, J., Mayer, C., & Rossi, S. (2009). Returns to shareholder activism: Evidence from a clinical study of the Hermes U.K. focus fund. The Review of Financial Studies, 22(8), 3093–3129.

Belloc, M., & Pagano, U. (2009). Co-evolution of politics and corporate governance. International Review of Law and Economics, 29(2), 106–114.

Black, B. S. (1992). Agents watching agents: The promise of institutional investor voice. In Becht, M., Franks, J., Mayer, C., & Rossi, S. (2009). Returns to shareholder activism: Evidence from a clinical study of the Hermes U.K. focus fund. The Review of Financial Studies, 22(8), 3093–3129.

Bradley, M., Schipani, C., Sundaram, A., & Walsh, J. (2000). The purposes and accountability of the corporation in contemporary society: Corporate governance at cross roads. Law and Contemporary Problems, 62(3), 9–86.

Charkham, J. P. (1994). Keeping good company: A study of corporate governance in five countries. In Okike, E. N. M. (2007). Corporate governance in Nigeria: The status quo. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(2), 173–193.

Child, J. (2002). A configuration analysis of international joint ventures. Organisation Studies, 23(5), 781–815.

Choi, W., & Cho, S. (2003). Shareholder activism in Korea: An analysis of PSPD’s activities. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 11(3), 349–364.

Coglianese, C. (2007). Legitimacy and corporate governance. Delaware Journal of Corporate Law, 32(1), 159–167.

Crespi, R., & Renneboog, L. (2010). Is (institutional) shareholder activism new? Evidence from UK shareholder coalitions in the pre-Cadbury era. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 18(4), 274–295.

Ewings, P., Powell, R., Barton, A., & Pritchard, C. (2008). Qualitative research methods. Plymouth: Peninsula Research and Development Support Unit.

Filatotchev, I., Jackson, G., Gospel, H., & Allcock, D. (2007). Key drivers of ‘good’ corporate governance and the appropriateness of UK policy responses. London: The Department of Trade and Industry.

Flick, U. (1992). Triangulation revisited: Strategy of validation or alternative? Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 22(2), 175–197.

Frynas, J. G., Beck, M. P., & Mellahi, K. (2000). Maintaining corporate dominance after decolonization: The “first mover advantage” of shell-BP in Nigeria. Review of African Political Economy, 27(85), 407–425.

Gillan, S. L., & Starks, L. T. (1998). A survey of shareholder activism: Motivation and empirical evidence. In Gillan, S. L. (2006). Recent developments in corporate governance: An overview. Journal of Corporate Finance, 12(3), 381–402.

Gillan, S. L., & Starks, L. T. (2000). Corporate governance proposals and shareholder activism: The role of institutional investors. Journal of Financial Economics, 57(2), 275–305.

Gillan, S. L., & Starks, L. T. (2007). The evolution of shareholder activism in the United States. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 19(1), 55–73.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. In Ratcliff, D. E. (1994). Analytic induction as a qualitative research method of analysis. The University of Georgia.

Gourevitch, P., & Shinn, J. (2005). Political power and corporate control: The new global politics of corporate governance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Grienenberger, W. F. (1995). Institutional shareholders and corporate governance. In Brossman, M. E., & Cinque, J. F. (1996). Proxy voting and shareholder activism: The emerging issues. Employee Benefits Journal, 21(2), 5–15.

Harrington, B. (2002). Obtrusiveness as strategy in ethnographic research. Qualitative Sociology, 25(1), 49–61.

Hendry, J., Sanderson, P., Barker, R., & Roberts, J. (2006). Owners or traders? Conceptualizations of institutional investors and their relationship with corporate managers. Human Relations, 59, 1101–1132.

Hendry, J., Sanderson, P., Barker, R., & Roberts, J. (2007). Responsible ownership, shareholder value and the new shareholder activism. Competition and Change, 11(3), 223–240.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behaviour, agency costs and ownership structure? Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360.

Judge, W. Q., Douglas, T. J., & Kutan, A. M. (2008). Institutional antecedents of corporate governance legitimacy. Journal of Management, 34, 765–785.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. (2008). Governance matters VII: Aggregate and individual governance indicators for 1996–2007. World Bank Policy research working paper no. 4654, from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=1148386.

Lubatkin, M., Lane, P. J., Collin, S., & Very, P. (2007). An embeddedness framing of governance and opportunism: Towards a cross-nationally accommodating theory of agency. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 28, 43–58.

Lynn, P., Turner, R., & Smith, P. (1998). Assessing the effects of an advance letter for a personal interview survey. Journal of the Market Research Society, 40(3), 265–272.

Okara, K. (2003). Shareholder activism—How feasible? from http://www.geplaw.com/corp_gov.htm.

Okike, E. N. M. (2007). Corporate governance in Nigeria: The status quo. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 15(2), 173–193.

Patton, M. Q. (1980). Qualitative evaluation methods. In Das, T. H. (1983). Qualitative research in organisational behaviour. Journal of Management Studies, 20(3), 301–314.

Punch. (2010). I’m ready to return—Akingbola. Punch. Accessed November 11, 2010 from http://www.punchng.com/Articl.aspx?theartic=Art20091207694745.

Roe, M. J. (1994). Strong managers, weak owners: The political roots of American Corporate Finance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Roe, M. J. (2003). Political determinants of corporate governance: Political context, corporate impact. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ROSC. (2004). Report on the observance of standards and codes—Nigeria. Accessed November 14, 2010, from http://www.worldbank.org/ifa/rosc_aa_nga.pdf.

Rossouw, G. J. (2005). Business ethics and corporate governance in Africa. Business and Society, 44(1), 94–106.

Rubach, M. J., & Sebora, T. C. (2009). Determinants of institutional investor activism: A test of the Ryan-Schneider Model (2002). Journal of Managerial Issues, 21(2), 245–261.

Sahara Reporters. (2010). The Nigerian disaster called Obasanjo. Sahara Reporters. Accessed November 11, 2010, from http://www.saharareporters.com/report/nigerian-disaster-called-obasanjo-0.

Sarkar, J., & Sarkar, S. (2000). Large shareholder activism in corporate governance in developing countries: Evidence from India. International Review of Finance, 1(3), 161–194.

Schacht, K. N. (1995). Institutional investors and shareholder activism: Dealing with demanding shareholders. Directorship, 21(5), 8–12.

Seki, T. (2005). Legal reform and shareholder activism by institutional investors in Japan. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 13(3), 377–385.

Sewell, M. (2008). The use of qualitative interviews in evaluation. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783.

Smith, M. P. (1996). Shareholder activism by institutional investors: Evidence from CalPERS. Journal of Finance, 51(1), 227–252.

Sun News. (2007). Behave yourselves at AGMs, SEC Warns Shareholders’ Associations. Daily Sun. Accessed November 14, 2010 from http://www.sunnewsonline.com/webpages/news/businessnews/2007/dec/18/business-18-12-2007-003.htm.

Sun News. (2008). Festus Odimegwu and the third term Booze. Accessed November 14, 2010, from http://www.sunnewsonline.com/webpages/columnists/flipside/2006/flipside-march-29-2006.htm.

Thompson, T., & Davis, G. (1997). The politics of corporate control and the future of shareholder activism in the United States. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 5(3), 152–159.

Transparency International. (2010). Corruption perceptions index 2010 results. Transparency International. Accessed June 4, 2011, from http://www.transparency.org/policy_research/surveys_indices/cpi/2010/results.

Van Maanen, J. (1979). Reclaiming qualitative methods for organisational research: A preface. In Das, T. H. (1983). Qualitative research in organisational behaviour. Journal of Management Studies, 20(3), 301–314.

Vanguard, N. (2007). How Nigeria lost 75 banks to poor corporate governance. Accessed November 14, 2010, from http://allafrica.com/stories/200711190560.html.

Wang, Y. (2006). Methodologies for impact evaluation: Quantitative vs qualitative methods. Paper presented the conference for evaluating the impact of projects and programmes, Beijing, China, April 10–14.

Wärneryd, K. (2005). Special issue on the politics of corporate governance: Introduction. Economics of Governance, 6(2), 91–92.

Wells, W. D., & Lo Sciuto, L. A. (1966). Direct observation of purchasing behaviour. Journal of Marketing Research, 3(3), 227–233.

West, A. (2009). The ethics of corporate governance: A (South) African perspective. International Journal of Law and Management, 51(1), 10–16.

William, M. K. (2006). Social research methods. Trochim, UK.

Yakasai, G. A. (2001). Corporate governance in a third world country with particular reference to Nigeria. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 9(3), 239–240.

Yerokun, O. (1992). The changing investment climate through law and policy in Nigeria. In Ahunwan, B. (2002). Corporate governance in Nigeria. Journal of Business Ethics, 37, 269–287.

Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Professor Richard Slack and the anonymous reviewers who provided useful feedback on earlier versions of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article majorly constitutes a part in Adegbite, E. (2010). The determinants of good corporate governance: The case of Nigeria. Doctoral thesis, Cass Business school, City University, London.

Appendix: Experts’ Interviews and Focus Groups ‘Guide/Areas for Discussions’

Appendix: Experts’ Interviews and Focus Groups ‘Guide/Areas for Discussions’

-

1.

How would you describe the Nigerian polity?

-

2.

How important is the Political environment in terms of promoting ‘good corporate governance’ in Nigeria?

-

3.

How do you regard the efficiency of the Federal Government in promoting/ensuring good corporate governance regulation in Nigeria?

-

4.

How do you regard the role/policies of the Federal Government in corporate governance, in terms of its effects on corporate independence and flexibility?

-

5.

How effective is shareholder activism in promoting good corporate governance in Nigeria?

-

6.

What are the problems facing effective shareholder activism in Nigeria. How can they be solved?

-

7.

How does the political environment affect shareholder activism in Nigeria?

-

8.

To what extent does the shareholder activism practice in Nigeria mirrors the country’s brand of politics?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adegbite, E., Amaeshi, K. & Amao, O. The Politics of Shareholder Activism in Nigeria. J Bus Ethics 105, 389–402 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0974-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0974-y