Abstract

Researchers have suggested that asexuality, which has been conceptualized traditionally as a persistent lack of sexual attraction to others, may be more common among individuals with autism spectrum disorder than in the neurotypical population. However, no studies to date have considered how these individuals understand and conceptualize their sexual identity. The aim of this study was to provide a more nuanced understanding of asexuality among individuals with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (HF-ASD) than has been done in the past. Individuals with ASD, 21–72 years old (M = 34.04 years, SD = 10.53), were recruited from online communities that serve adults with ASD and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to complete an online survey of sexual and gender identity. Overall, 17 (5.1%) participants who met study criteria (N = 332) self-identified as asexual. However, 9 of the 17 people identifying as asexual expressed at least some sexual attraction to others. In addition, based on open-ended responses, some participants linked their asexual identity more with a lack of desire or perceived skill to engage in interpersonal relations than a lack of sexual attraction. Results suggest that researchers should be cautious in attributing higher rates of asexuality among individuals with ASD than in the general population to a narrow explanation and that both researchers and professionals working with individuals with ASD should consider multiple questions or approaches to accurately assess sexual identity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since 2004, there has been a surge of research interest in human asexuality, often defined broadly as a lack of sexual attraction towards anyone (Asexuality Visibility and Education Network; AVEN; www.asexuality.org; Bogaert, 2004; Brotto & Yule, 2017). However, this definition has evolved with growing recognition that there are variations in how asexual individuals experience relationships, attraction, and arousal (Van Houdenhove et al., 2017). The term, asexual umbrella, or “Ace,” includes asexuality plus identities similar to asexuality (i.e., demisexuality or gray-A) that represent varied types or levels of attraction depending on context. Although individuals who identify as asexual usually consider lack of attraction in their identity, some asexuals may also report a persistent lack of sexual desire (Brotto et al., 2015) or qualitatively describe a lack of sexual desire in at least some situations (e.g., when interacting with health care providers) (Gupta, 2017). For the purposes of this study, we adopted earlier definitions of asexuality, namely lack of sexual attraction, while acknowledging the possibility of more nuanced conceptualizations.

Given the lack of a singular definition, estimates of the population prevalence of asexuality vary across studies (Brotto & Milani, 2020). Large-scale national probability studies of residents in the UK have shown that approximately 0.4% (Aicken et al., 2013; Bogaert, 2013; Greaves et al., 2017) to 1% (Bogaert, 2004, 2013; Poston & Baumle, 2010) of adults self-identify as asexual. Other prevalence estimates appear higher, with up to 3.3% of women and 1.5% of men from a Finnish sample reporting not experiencing sexual attraction within the past year (Höglund et al., 2014).

Despite varied prevalence of asexuality in the general population, some researchers have suggested a link between asexuality and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (George & Stokes, 2018; Gilmour et al., 2012), which is characterized by impairments in social interaction and communication as well as by limited and stereotyped patterns of behaviors, interests, and activities (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). As outlined below, the link between ASD and asexuality is interesting for both clinical and theoretical reasons. However, investigation of such a link is hampered by limited understanding of the experiences of individuals with ASD who identify as asexual. Therefore, our goal was to provide a more nuanced understanding of asexual identity among individuals with ASD.

Asexuality Among Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Brotto et al. (2010) conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 self-identified asexuals and found that participants described conversations on the AVEN discussion board in which several online community members discussed a possible link between ASD and asexuality. Furthermore, consistent with characteristics of both asexuality and ASD, Yule et al. (2013) found that asexual-identifying individuals were more likely to report difficulties in interpersonal relationships as well as symptoms of social withdrawal.

Although there is some preliminary support for a putative relationship between ASD and asexuality among samples of individuals with high-functioning ASD (HF-ASD), findings have been mixed. For example, in a study of 54 women with ASD, participants were asked a question about their sexual preference, with response options: males, females, either or neither (Ingudomnukul et al., 2007). Compared to a neurotypical group of 185 women, the women with ASD were significantly more likely to indicate a sexual preference for neither gender (0% vs. 17%, respectively). The authors acknowledged that the reasons behind this disparity were unclear and that it is possible participants’ understanding of the term “asexuality” differed from the definition adopted by AVEN, and instead captured lack of sexual activity. The authors proposed that although the higher prevalence of asexuality among individuals with ASD may reflect their lack of sexual attraction, it also may reflect social challenges that impinge upon their having sexual interactions.

Another study of 82 mostly female community-dwelling persons with ASD used the Sell Scale of Sexual Orientation (Sell, 1996) to measure sexual orientation as a continuous construct; the mean level of “asexuality” was significantly higher among the ASD group compared to a control group of 282 individuals from the general population who did not have ASD (Gilmour et al., 2012; see George & Stokes, 2018 for similar results). In another study, Bejerot and Eriksson (2014) found that one of 25 males and one of 22 females with ASD (approximately 4%), versus none (0%) of the neurotypical males and females, reported not being sexually attracted to men or women. It is still unclear based on these findings whether the rates of identified asexuality among those with ASD are higher than populations of non-ASD persons.

Overall, there are a number of limitations to previous studies. First, the two studies using the Sell Scale of Sexual Orientation did not provide data on how many of the individuals with ASD in their sample identified as asexual. As such, the meaning of the higher average ratings of asexuality among the ASD group is uncertain. Second, two of the four studies did not include men. Third, none included a validated measure of asexuality among individuals with HF-ASD. Yet, individuals with ASD often have idiosyncratic or literal interpretations of language and engage in black and white thinking (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Chouinard & Cummine, 2016; Lo et al., 2017; Pexman et al., 2011). Thus, it is possible that some individuals with HF-ASD, when asked to indicate their sexual identity, endorse “asexual” because they interpret this term as meaning something other than a lack of sexual attraction to men or women. Furthermore, it is possible that some individuals with HF-ASD who report no sexual attraction or preference for men or women do not self-identity as asexual. For example, some individuals with HF-ASD may understand the term “asexual” in the way it has been used to (erroneously) stereotype individuals with disabilities, including individuals with HF-ASD, as non-sexual and uninterested in engaging in sexual activity (Caruso et al., 1997; Gougeon, 2010; Koller, 2000). Alternatively, they may have drawn conclusions about sexual attraction to others based on their (lack of) sexual experience. Any of these idiosyncratic interpretations would have implications for how asexuality is assessed and operationally defined and in estimating prevalence of asexuality among individuals with HF-ASD.

Fourth, these studies did not assess the extent to which individuals with HF-ASD also identify as aromantic. Between two-thirds and three-quarters of asexuals report experiences of romantic attraction and wish to be in a romantic relationship, perceiving that there are non-sexual benefits of partnership for themselves. The other one-quarter to one-third identify as “aromantic” and are not interested in being in a romantic relationship (Ginoza et al., 2014; Zheng & Su, 2018). Furthermore, 27% have had sexual intercourse with at least one partner, despite a lack of attraction (Brotto et al., 2010). Byers et al. (2013) found that 79% of their sample of single individuals with HF-ASD had not engaged in sexual activity with a partner in the previous month (lifetime sexual experience was not assessed). Given social deficits associated with ASD (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), it may be that aromanticism and sexual inexperience are more prevalent among individuals with ASD compared to neurotypical individuals, particularly among people who identify as asexual. That is, asexual individuals with ASD may lack sexual attraction, romantic attraction, and sexual experience.

The proposed link between ASD and asexuality is, in part, based on the fact that both appear to have strong biological underpinnings (Bogaert, 2017; Brotto & Yule, 2017; Zafeiriou et al., 2013). In terms of the causes of asexuality, a recent comprehensive review of the literature on asexuality (Brotto & Yule, 2017) concluded that asexuality is most likely to have biological underpinnings given evidence that biomarkers associated with sexual orientation in non-heterosexual groups, compared to heterosexual individuals (Blanchard, 2008; Blanchard & Bogaert, 1996; Lalumière et al., 2000), are also more prevalent among asexual individuals (Yule et al., 2014, 2017). Although evidence for the biological basis of asexuality is largely indirect, asexuals’ common claim that they “had always felt that way” (Brotto et al., 2010; Carrigan, 2011; Scherrer, 2008; Van Houdenhove et al., 2015) supports the biological basis argument (although this still does not rule out early environmental influences on the experience of asexuality). It has also been argued that asexuality is likely best classified as a unique sexual orientation (Brotto & Yule, 2017) or as an identity and community (Scherrer & Pfeffer, 2017).

The question of the extent to which individuals with HF-ASD identify as asexual is interesting for both theoretical and clinical reasons. Theoretically, there has been interest in a possible third-variable explanation associated with both ASD and minority sexual orientation expressions such as antenatal testosterone exposure or common genetic influences (Dewinter et al., 2017), although there has yet to be any empirical test of this possibility. Finding a high proportion of asexuality in ASD samples would provide support for the theoretical biological link, particularly if individuals report a lack of attraction or identify as asexual. On the other hand, it is important to hold open the possibility of no association as Chasin (2017) noted, “…asexuality and autism may and/or may not be phenomenologically related” (p. 631). For example, the social deficits associated with ASD and idiosyncratic interpretations of “asexuality” as an identity may account for high rates of asexuality in ASD samples. It is also possible that lifelong sexual inexperience may increase the likelihood of identifying one’s asexuality.

The Current Study

The goal of this study was to provide a more nuanced understanding of asexuality among individuals with HF-ASD by examining asexuality in a large sample of individuals living in the community using a multidimensional approach. We assessed both sexual attraction and self-definition as well as romantic attraction and sexual experience. In addition, to determine whether individuals with HF-ASD have idiosyncratic interpretations of asexuality, we asked participants who endorsed an asexual identity to indicate, using an open-ended format, what being asexual means to them, and why asexuality best describes their identity. We posed the following research question: What percentage of individuals with HF-ASD identify as asexual, report lack of sexual attraction, lack of romantic attraction, and lifetime sexual inexperience (RQ1)? To what extent do asexual identity, lack of sexual attraction, lack of romantic attraction, and lifetime inexperience co-occur among individuals with HF-ASD (RQ2)? Consistent with recommendations by Woodbury-Smith et al. (2005) to identify individuals with substantial ASD symptoms, only participants who scored above the cutoff score (26 or greater) for ASD on the Autism Spectrum Quotient (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001) were included. Because many adults with HF-ASD are not identified as having ASD during childhood and have not sought a formal diagnosis as an adult, due perhaps to the substantial cost of such an assessment (Barnhill, 2007; Stoddard et al., 2017), we included individuals who had or had not received a professional diagnosis. Indeed, diagnosis of ASD has traditionally focused on youth and only recently have professionals become more inclusive in diagnosing older individuals who are highly verbal and intelligent.

Method

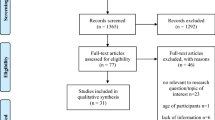

Participants

Participants were 561 individuals, aged 21–72 years (Mage = 34.04 years, SD = 10.53) from North America who were recruited from sources that serve adults with ASD (e.g., community organizations, online communities, support groups) (n = 214) and from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (M-TurkR) (n = 347) to complete a survey on sexual and gender identity among individuals with ASD. From the original sample, 229 participants were dropped: 116 because they scored below 26 on the AQ (16 recruited from community organizations and 100 recruited from M-Turk) although they did have substantial ASD symptoms (MASD score = 21.10, SD = 3.67) and 113 (53 recruited from community organizations and 60 recruited from M-TurkR) because of evidence of inadequate, random, or invalid responses or duplicate IP addresses in the sample. The majority of the selected sample (N = 332) identified as Caucasian (85.8%), and the remainder identified as African American (4.5%), South or South East Asian (2.7%), Hispanic (3.0%), Aboriginal (0.3%), or other (3.6%). Regarding gender, participants identified as male (38.1%), female (52.3%), genderqueer (2.4%), transsexual male (1.5%), transsexual female (1.5%), unlabeled/no gender/genderless/agender (2.4%), bigender (0.3%), and other (1.5%). In terms of highest educational level, 1.2% reported less than high school, 23.9% graduated from high school, 26.1% received some post-secondary education, 30.9% earned an undergraduate degree, and 17.9% earned a post-university degree. Nearly half of participants (47.4%) reported being employed full time, 24.2% reported part-time employment, and the rest (28.4%) indicated no employment. Participants reported being married or cohabitating with a partner (38.9%), dating one partner exclusively (13.9%), dating non-exclusively (5.4%), or not dating (41.9%). Participants reported predominately (80.0%) receiving an ASD diagnosis from a medical professional (e.g., psychiatrist, neurologist, physician) or psychologist.

Measures

The Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ; Baron-Cohen et al., 2001) is a 50-item self-report questionnaire assessing autistic traits in adults with average intelligence. It consists of 10 items in each of five domains: (1) social skills, (2) attention to detail, (3) communication, (4) imagination, and (5) attention switching. Responses are provided on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4) and then dichotomized to indicate presence or absence of a particular symptom. Responses were summed to yield possible scores ranging from 0 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology. There is considerable research supporting the validity of the AQ as a screening tool for ASD. For example, Woodbury-Smith et al. (2005) reported good discriminative validity and good screening properties for the AQ using a screening cutoff of 26. At this cutoff score, 83% of patients diagnosed with ASD were correctly classified based on their AQ score (sensitivity was 0.95, specificity 0.52, and positive predictive value of 0.84). Similarly, Sonié et al. (2013) found that the AQ differentiated adolescents with HF-ASD from neurotypical adolescents and adolescents with psychiatric disorders with 0.89 sensitivity and 0.98 specificity. Other researchers have also provided evidence for the reliability and validity of the AQ (Armstrong & Iarocci, 2013; Hoekstra et al., 2008; Lepage et al., 2009). The AQ had good internal consistency in the current study (α = 0.84).

Participants were asked a total of 10 items that reflected self-identity, level of sexual and romantic attraction, and sexual history. One item asked participants to indicate the identity that best fit from the following categories: heterosexual, lesbian, bisexual, homosexual, gay, queer, asexual, unlabeled, unsure, or other. Individuals who reported an asexual sexual identity were asked an open-ended, follow-up question to express what being asexual meant to them and why asexuality best described their identity. Participants were also asked to indicate their level of sexual attraction to both men and women on two separate questions and their level of romantic attraction to men and women on two additional items. Responses to all four attraction items were rated on scales ranging from no attraction to men/women (1) to extremely attracted to men/women (7). These items were used to create two index variables: any sexual attraction to men and/or women (no/yes) and any romantic attraction to men and/or women (no/yes). Participants were asked with how many different partners they had ever engaged in sexual activity that involved the genitals (i.e., genital fondling, oral sex, vaginal sex, anal sex).

Asexuality was further assessed with the Asexuality Identification Scale (AIS; Yule et al., 2014, 2015), which consists of 12 items (e.g., “I lack interest in sexual activity”) rated on a 5-point scale ranging from completely true (1) to completely false (5). A summed total score was created, ranging from 12 to 60. As recommended by Yule et al. (2014), a cutoff score of 40/60 was used to identify individuals who likely experience a lack of sexual attraction and can be considered asexual. Indeed, Yule et al. (2015) reported in their sample that 93% of self-identified asexuals scored at or above 40 (i.e., sensitivity) and that 95% of sexual participants scored less than 40 (i.e., specificity). This scale is psychometrically sound (e.g., convergent validity, discriminant validity) and has been shown to distinguish self-identified asexual individuals from sexual individuals (Yule et al., 2014, 2015, 2017). Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was 0.93.

Procedure

Participants with autism spectrum disorder (i.e., high-functioning autism, Asperger’s disorder, or pervasive development disorder) who were 21 years or older were recruited to complete an online survey on sexuality among adults with high-functioning ASD. Assessments took place at participants’ convenience on their own computing device. Participants from community samples did not receive any financial inducement and participants who were recruited from M-Turk residing in the USA or Canada were compensated $2 for their time. All study procedures were approved by authors’ institutional ethics review boards.

Statistical and Descriptive Analyses

Exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the prevalence of various responses in terms of reported sexuality, lifetime frequency of sexual partners, and romantic and sexual attraction. Content analysis (Krippendorf, 2003; Merriam, 2009) was conducted on the open-ended question about defining asexuality. Initial codes were developed in collaboration between two authors (S. R., E. S. B.) who had independently examined the respondent sample. All the interviews were organized into broad codes, including no sexual attraction, no romantic attraction, no sexual behavior, and a best fit of asexuality, with each code representing a salient theme in the responses. There was complete reliability in coding for 13 of the 17 respondents. The responses of the four remaining respondents required multiple codes, and there was disagreement about one of these codes. These were resolved by consensus.

Results

Sexual Identity

We first examined the percent of participants who identified as asexual, reported lack of sexual attraction, lack of romantic attraction, and sexual inexperience (RQ1). Just over half of participants (56.8%) identified as heterosexual with the remainder identifying with a range of sexual minority identities, including 17 (5.1%) individuals who identified as asexual (2 male, 11 female, 1 genderqueer, 3 agender). On the AIS, 62 (19.2%) respondents met the cutoff (AIS score ≥ 40/60) and could be considered asexual (Yule et al., 2014). Of note, only 19 individuals (8 whom identified as asexual) reported “completely false” to the first item on the AIS (“I experience sexual attraction towards other people”). In terms of attraction, 15 (4.5%) individuals of the overall sample reported no sexual attraction to men or women and 7 (2.1%) individuals reported no romantic attraction to men or women. In terms of lifetime sexual partners, 36 individuals (10.8%) reported having had no sexual partners. In total, only 4 individuals (1 male, 3 female) endorsed all five of the aforementioned criteria.

The concordance of the various markers of asexuality (RQ2) is shown in Table 1. There was substantial overlap but not concordance between sexual attraction and romantic attraction for both individuals who identified as asexual (73.7%), \({\chi }^{2}\)(1, N = 17) = 7.97, p = 0.005, and individuals who reported an identity other than asexual (97.7%), \({\chi }^{2}\)(1, N = 312) = 20.93, p < 0.001. Of the 17 people who identified as asexual, 8 (47.1%) individuals reported no sexual attraction to anyone of binary sex (male, female), and 5 (29.4%) individuals reported no sexual or romantic attraction to anyone of binary sex. In contrast, almost all the individuals who did not identify as asexual reported some sexual (97.8%) or romantic (99.4%) attraction. The majority of the 17 participants who reported being asexual (82.4%) scored at or above the cutoff of 40 on the AIS, compared to only 15.7% of individuals who did not identify as asexual, \({\chi }^{2}\)(1, N = 323) = 46.15, p < 0.001.

In terms of lifetime sexual partners, individuals who did and did not identify as asexual did not differ significantly (Mdn = 3, M = 16.47, SD = 25.79 and Mdn = 4, M = 8.78, SD = 18.15, respectively), Mann–Whitney U = 2572, z = − 0.167, p = 0.87. The responses to the open-ended question by the 17 individuals who identified as asexual are shown in Table 2. (One individual did not give a response.) The most common response to the question about why asexuality best described their identity was that the participant had no sexual attraction to others (n = 9). As an example, a 22-year-old man noted simply, “I don’t care or desire any type of relationship with another person. I have no sexual desire or attraction.” Another person stated, “I have no sexual feelings for anyone at all. I do not get ‘crushes’ on people and do not feel aroused looking at any people.” However, one woman reported a lack of romantic attraction or interests to the point of the interview as defining her asexuality: “Being asexual means that although I do experience sexual interest at times (and have engaged in sexual activity), typically a relationship with a close female friend (we remained non-romantic friends and still do to this day), and have no desire to date.” Furthermore, three individuals described the asexual label as fitting them because they do not engage in sexual behavior, as exemplified by one person: “I am not interested in sexual relations with other people. I find it too overwhelming.” Finally, some individuals indicated that asexual identification represented the best fit to their identity, with little or no regard to their level of sexual attraction to others. For example, a 34-year-old woman stated, “I wasn’t entirely comfortable checking the asexual box and considered checking unlabeled or unsure…I’d use to represent a part of my identity, but I suspect my sexual identity would be described by others as asexual if known.” This person, similar to some others in the study, noted the complexity of sexual identity, and she, in particular, distinguished her perspective from how others might label her.

Discussion

To provide a more nuanced understanding of asexuality among individuals with HF-ASD than has been done in past research, we assessed not only self-report sexual identity but also sexual attraction, romantic attraction, and sexual experience. We also asked individuals who identified as asexual to explain their reasons for doing so. Overall, there was substantial variability and lack of consistency among individuals’ overall ratings of sexual attraction, romantic attraction, self-report asexuality, and open-ended descriptions of their reported asexual identity. The finding that only four individuals endorsed all five criteria used to define asexuality is consistent with past studies showing marked variability in how asexuality is defined by asexual persons (as reviewed by Brotto & Milani, in press) and extends this finding to individuals with ASD.

Conceptualizing Asexuality

In terms of self-identity, we found that 5.1% of our sample of individuals with ASD self-identified as asexual. Although this prevalence is higher than the prevalence rate of strict definitions of asexuality based on large population-based studies (approximately 1%; Bogaert, 2004, 2013; Poston & Baumle, 2010), it was not much higher than other reports of asexuality prevalence with small samples or when looser definitions are used. As examples, Bejerot and Eriksson (2014) found that 4% of a small sample of persons with ASD endorsed a lack of sexual attraction, and Poston and Baumle (2010) noted that 3.9% of individuals broadly responded “something else” in identifying their sexuality, which the authors surmised “would be the response for self-identified asexuals” (p. 520). Overall, with strict definitions of asexuality such as complete lack of sexual attraction, our study suggests that individuals with ASD are more likely to self-identify as asexual than neurotypical persons.

Using the published cutoff score of 40 on the Asexual Identification Scale, a much larger percentage (19.2%) were labeled as asexual. The AIS was developed to provide a more objective method of establishing one’s asexuality identity using cutoff scores. Based on sensitivity and specificity classification rates reported by Yule et al. (2015), we would expect that approximately 1 of 17 individuals identifying as asexual and 15 of 306 individuals not identifying as asexual in the current study would be incorrectly classified. However, because the AIS has not been validated among persons with HF-ASD and given that 15.7% of individuals with HF-ASD who did not identify as asexual scored above the cutoff on the AIS, our findings suggest that use of the AIS alone to signal asexuality in individuals with ASD may not be aligned completely with their own identities. Alternatively, perhaps individuals with ASD are more likely to (accurately) identify as asexual when given the opportunity through multi-item measures. Overall, although the AIS provides useful information, it alone without an individual’s self-report of asexuality, it should not be used to identify asexuality.

Although early definitions considered asexuality to be a lack of sexual attraction to anyone (Bogaert, 2004; Brotto & Yule, 2017), this definition has evolved over time to recognize that asexuals may experience their sexual attractions in diverse ways (Van Houdenhove et al., 2017). For the purposes of this study, we adopted the original definition of asexuality and found that 4.5% of our sample of individuals with HF-ASD endorsed no sexual attraction. Our findings suggest that the rates of asexuality determined by assessing identity and attraction are similar. However, these two estimates do not represent the same individuals. If dual criteria of self-definition of asexuality and no reported sexual attraction are used, the prevalence of asexuality in our sample dropped to 2.4%. Alternatively, more than half (52.9%) the HF-ASD individuals who identified as asexual reported some degree of sexual attraction to men or women compared to 97.4% of HF-ASD who did not identify as asexual; the high rates of asexuals reporting some sexual attraction in our sample deserves consideration. It is possible that a subgroup of asexuals may identify more closely with other Ace umbrella identities (van Anders, 2015), such as demisexuality, defined as a person who does not experience sexual attraction until they are in a romantic relationship. There are virtually no empirical data available on the experiences of demisexuals and whether demisexuality might be more likely among those with HF-ASD. On the other hand, it may be that individuals in our sample were identifying as asexual based on parameters unrelated to their lack of sexual attraction. The responses to the free-response questions offer some nuance to this possibility.

We found that the most common explanation provided for why this subsample of 17 individuals identified as asexual was that they had no sexual attraction to others. This is entirely consistent with generally accepted definitions of asexuality as representing a lack of sexual attraction. Smaller numbers of participants (n = 3) indicated that they chose the asexual label because they were not engaged in sexual activity; all three identified as having some level of sexual attraction. Not engaging in sexual activity has long been accepted by the asexuality community as a valid reason for identifying as asexual, although it is also possible there may be other reasons for lack of sexual activity other than one’s asexuality (e.g., chosen celibacy, relationship conflict, experience of sensory dysregulation or idiosyncratic sensory responses). Labeling oneself as asexual solely based on sexual activity and, regardless of one’s level of sexual (non)attraction, is problematic because people may be not engaging in sexual activity for any variety of reasons independent of their asexuality (or sexual orientation more generally). Although lack of sexual attraction and lack of sexual activity may both be present for some asexuals, scholars have also recognized that these can be entirely independent constructs (Chasin, 2017; Rothblum et al., 2020). As an example, two of the participants who identified as asexual reported having more than 40 lifetime sexual partners.

Expressions of romantic attraction varied in our sample, which is not surprising given research showing a wide range of romantic orientations among asexually identified persons, from fully romantic identified to completely aromantic (i.e., not desiring or wanting a romantic, non-sexual relationship) (Ginoza et al., 2014; Strunz et al., 2017; Zheng & Su, 2018). For example, one recent large study of romanticism among asexuals found that 74% of participants who identified as asexual also reported a romantic attraction and, among them, their romantic attractions were expressed in diverse ways (Antonsen et al., 2020). One participant reported endorsing the asexual label only because of her lack of romantic attraction or interest; others included lack of romantic attraction in addition to providing other reasons for their adopting an asexual identity; and still others did not refer to romantic attraction at all. The proportion of asexuals in the general population who identify as aromantic ranges between one quarter and one-third (Antonsen et al., 2020; Ginoza et al., 2014; Zheng & Su, 2018). In our sample, just under one-third (29.4%) of those who identified as asexual also identified as lacking romantic attraction, compared to less than 1% of the HF-ASD sample who identified as sexual. Given that the prevalence of aromantic asexuals in our HF-ASD sample was similar to published data on the prevalence of aromanticism, we did not find evidence for higher rates of aromantic asexuals among persons with HF-ASD.

Limitations and Implications

The findings need to be considered in light of certain limitations. First, although we had a relatively large sample size, only a small number of individuals identified as asexual. Research with even larger samples of individuals with HF-ASD is needed to provide key information about asexual identity in this population. Second, the use of responses to open-ended questions to investigate participants’ reasons for selecting asexual as their identity provided only limited information about their reasons. Interview studies would provide the opportunity to probe these reasons in greater depth, as well as to enquire specifically about the role of sexual attraction, romantic attraction, sexual or romantic desire, sexual activity, and perceived social scripts and expectations around sexual and romantic activity in determining their identity. Relatedly, the Ace experiences of gray asexuality and demisexuality were not offered as sexual identity options, so it is unclear how those individuals would have classified themselves. Based on our open-ended responses, we found one individual who likely would have identified as gray asexual. Although we adopted a rather strict definition of asexuality, it is well recognized within the Ace community that there are different definitions of asexuality that vary in the degree of sexual attraction. As such, future studies of asexuality among those with HF-ASD should be more inclusive in their definitions of asexuality and allow individuals to write in identities not listed to allow individuals to self-identify in the way that fit best for them. Third, given we recruited participants for a study on sexuality and ASD, some individuals with HF-ASD who did not experience sexual attraction or had not engaged in sexual activity may have assumed they were not eligible for the study. Moreover, given we did not recruit a comparison group of neurotypical individuals, we were not able to examine sexuality characteristics among people with ASD relative to those in neurotypical populations. Taken together, broadly focused studies in which individuals with HF-ASD and neurotypical individuals are recruited should include a comprehensive and nuanced assessment of sexual identities. Finally, similar to most previous research with neurotypical populations, the current study was based on self-report at one point in time. Although this provided important information about asexuality in individuals with HF-ASD, it would be useful to determine how these reported facets of asexuality covary with physiological arousal assessed through psychophysiological measurement (see Bogaert, 2017). Research also is needed that examines the development and stability of all the dimensions of asexuality over the lifespan (Cranney, 2017; Levine, 2017). Such longitudinal research would shed light on the roles of biological and environmental factors as well as stable versus situational factors to asexuality.

In spite of the limitations, the findings have implications for how asexuality is assessed in future research studies with samples of persons with HF-ASD (and possibly in the general population, although this remains to be investigated). The finding that use of the AIS resulted in nearly 20% of the sample being labeled as asexual, yet self-identification labeled only 5.1% as asexual suggests that the reliance on the AIS alone may be inappropriate for identifying persons with HF-ASD as asexual. The finding that more than half our sample who identified as asexual reported some level of sexual attraction and, conversely, that 2.3% of individuals who reported no sexual attraction did not identify as asexual, suggests that there may be considerable diversity in the expressions of asexual attraction—both in the asexual and in the allosexual HF-ASD community. Overall, we advocate for the use of self-identification of asexuality along with empowering individuals to choose from varying definitions of asexuality that pertain to lack of sexual attraction, lack of sexual desire, and lack of sexual activity—given that all have featured in the qualitative reports of asexual persons (Gupta, 2017). Furthermore, given the potential idiosyncratic interpretations of questions related to identity and attraction among individuals with HF-ASD, our results suggest that researchers should be cautious in attributing the higher rates of asexuality typically found among HF-ASD individuals to a biological third variable such as antenatal testosterone exposure or common genetic influences (Dewinter et al., 2017). Considering that our sample may be functioning particularly well, based on relatively high education and employment among the ASD population (Baldwin et al., 2014; Seaman & Cannella-Malone, 2016), interpretations of questions may be even more varied among individuals whose language abilities and understanding are impacted.

The results also have implications for clinical practice and sex education. Clinicians or sexual health educators working with HF-ASD persons should not rely on a single metric of asexuality, whether it be the AIS or self-reported sexual or romantic attraction or sexual activity. Moreover, clinicians should offer culturally competent care and strive to provide psychoeducation and interpret in ordinary ways (i.e., normalize) the range of asexual identities as well as discuss the extent to which various labels capture individuals’ experiences and identities (Flanagan & Peters, 2020; Gupta, 2017). Given that asexuality is usually not accompanied by significant distress over one’s lack of sexual attraction or desire (Brotto et al., 2015), treatment recommendations must adapt to a person’s wish for such treatment, in light of whether they are experiencing distress and the source of that distress. For asexual-identified individuals whose distress comes from not meeting social expectations regarding attraction or sexual activity, treatment may involve psychoeducation to normalize asexuality. For asexual-identified individuals whose distress comes from a lack of personally desired sexual activity, clinicians should consider that the individual is actually using “asexuality” to describe a desire disorder and that this self-definition may be impeding opportunities for intervention. Finally, because there is some evidence of increased likelihood of previous sexual trauma among individuals identifying as asexual (Parent & Ferriter, 2018), it is important that professionals involved in assessment and intervention consider this possibility.

We also advocate for a sensitive and comprehensive psychosexual evaluation among persons with HF-ASD to determine the range, intensity, and frequency associated with their sexual attractions, behaviors, and romantic attractions. In addition, because some individuals with ASD experience sensory dysregulations (Barnett & Maticka-Tyndale, 2015; George & Stokes, 2018), it is important to determine whether individuals with HF-ASD experience sensory-related asexuality and whether they are distressed. In their qualitative study with individuals with HF-ASD, Barnett and Maticka-Tyndale (2015) found that many of their participants reported that some of the sensations they experienced during sexual activity were unpleasant (i.e., experienced hypersensitivity) or that they were not consciously aware of physical sensations including arousal during sexual activity (i.e., experienced hyposensitivity). If so, individuals with ASD may need help identifying ways to express their sexuality that are experienced as pleasant, such as through solitary sexual activities or by altering partnered sexual activities to heighten or lessen physical sensations (e.g., having the partner wear silk gloves) (Byers et al., 2013). Symptoms associated with ASD, including impairments in social interaction and communication, repetitive and stereotyped behaviors, and sensory issues, may weaken the strong links typically found between sexual attraction, romantic attraction, and sexual behavior in neurotypical populations. Overall, it is important to consider such symptoms of ASD and more broadly investigate the conceptualization of sexual identity among individuals with ASD relative to neurotypical populations.

References

Aicken, C. R. H., Mercer, C. H., & Cassell, J. A. (2013). Who reports absence of sexual attraction in Britain? Evidence from national probability surveys. Psychology & Sexuality, 4, 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.774161

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Press.

Antonsen, A., Zdaniuk, B., Yule, M., & Brotto, L. A. (2020). Ace and Aro: Understanding differences in romantic attractions among persons identifying as asexual. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 1615–1630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01600-1

Armstrong, K., & Iarocci, G. (2013). The Austism Spectrum Quotient has convergent validity with the Social Responsiveness Scale in a high-functioning sample. Journal of Autism Development Disorders, 43, 2228–2232. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1769-z

Baldwin, S., Costley, D., & Warren, A. (2014). Employment activities and experiences of adults with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 2440–2449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2112-z

Barnett, J. P., & Maticka-Tyndale, E. (2015). Qualitative exploration of sexual experiences among adults on the autism spectrum: Implications for sex education. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 47, 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1363/47e5715

Barnhill, G. P. (2007). Outcomes in adults with Asperger syndrome. Focus on Autism & Other Developmental Disabilities, 22, 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/10883576070220020301

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31, 5–17.

Bejerot, S., & Eriksson, J. M. (2014). Sexuality and gender role in autism spectrum disorder: A case control study. PLoS ONE, 9(1), e87961. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087961

Blanchard, R. (2008). Review and theory of handedness, birth order, and homosexuality in men. Laterality, 13, 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576500701710432

Blanchard, R., & Bogaert, A. F. (1996). Homosexuality in men and number of older brothers. American Journal of Psychiatry, 153, 27–31. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.153.1.27

Bogaert, A. F. (2004). Asexuality: Prevalence and associated factors in a national probability sample. Journal of Sex Research, 41, 279–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490409552235

Bogaert, A. F. (2013). Demography of asexuality. In A. K. Baumle (Ed.), International handbook on the demography of sexuality (pp. 275–288). Springer.

Bogaert, A. F. (2017). What asexuality tells us about sexuality [Commentary]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 629–630. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0892-2

Brotto, L. A., Knudson, G., Inskip, J., Rhodes, K., & Erskine, Y. (2010). Asexuality: A mixed-methods approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 39, 599–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-008-9434-x

Brotto, L. A., & Milani, S. (in press). Asexuality: When sexual attraction is lacking. In D. P. VanderLaan & W. I. Wong (Eds.), Gender and sexuality development: Contemporary theory and research. Springer.

Brotto, L. A., & Yule, M. (2017). Asexuality: Sexual orientation, paraphilia, sexual dysfunction, or none of the above? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 619–627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0802-7

Brotto, L. A., Yule, M., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2015). Asexuality: An extreme variant of sexual desire disorder? Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12, 646–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12806

Byers, E. S., Nichols, S., & Voyer, S. (2013). Challenging stereotypes: Sexual functioning of single adults with high functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2617–2627. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1813-z

Carrigan, M. (2011). There’s more to life than sex? Difference and commonality within the asexual community. Sexualities, 14, 462–478. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460711406462

Caruso, S. M., Baum, R. B., Hopkins, D., Lauer, M., Russell, S., Meranto, E., & Stisser, K. (1997). The development of a regional association to address the sexuality needs of individuals with disabilities. Sexuality and Disability, 15, 285–291. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024725515740

Chasin, C. J. D. (2017). Considering asexuality as a sexual orientation and implications for acquired female sexual arousal/interest disorder [Commentary]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 631–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0893-1

Chouinard, B., & Cummine, J. (2016). All the world’s a stage: Evaluation of two stages of metaphor comprehension in people with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 23, 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2015.12.008

Cranney, S. (2017). Does asexuality meet the stability criterion for a sexual orientation? [Commentary]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 637–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0887-z

Dewinter, J., De Graaf, H., & Begeer, S. (2017). Sexual orientation, gender identity, and romantic relationships in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 2927–2934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3199-9

Flanagan, S. K., & Peters, H. J. (2020). Asexual-identified adults: Interactions with health-care practitioners. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 1631–1643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01670-6

George, R., & Stokes, M. A. (2018). Sexual orientation in autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research, 11, 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1892

Gilmour, L., Schalomon, P. M., & Smith, V. (2012). Sexuality in a community based sample of adults with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 313–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.06.003

Ginoza, M. K., Miller, T., & AVEN Survey Team. (2014). The 2014 AVEN community census: Preliminary findings. Retrieved February 24, 2018 from https://asexualcensus.files.wordpress.com/2014/11/2014censuspreliminaryreport.pdf

Gougeon, N. A. (2010). Sexuality and autism: A critical review of selected literature using a social-relational model of disability. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 5, 328–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2010.527237

Greaves, L. M., Barlow, F. K., Huang, Y., Stronge, S., Fraser, G., & Sibley, C. G. (2017). Asexual identity in a New Zealand national sample: Demographics, well-being, and health. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 2417–2427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0977-6

Gupta, K. (2017). What does asexuality teach us about sexual disinterest? Recommendations for health professionals based on a qualitative study with asexually identified people. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 43, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2015.1113593

Hoekstra, R. A., Bartels, M., Cath, D. C., & Boomsma, D. I. (2008). Factor structure, reliability and criterion validity of the Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ): A study in Dutch population and patient groups. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38, 1555–1566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0538-x

Höglund, J., Jern, P., Sandnabba, N. K., & Santtila, P. (2014). Finnish women and men who self-report no sexual attraction in the past 12 months: Prevalence, relationship status, and sexual behavior history. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(5), 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0240-8

Ingudomnukul, E., Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., & Knickmeyer, R. (2007). Elevated rates of testosterone-related disorders in women with autism spectrum conditions. Hormones and Behavior, 51, 597–604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ybeh.2007.02.001

Koller, R. A. (2000). Sexuality and adolescents with autism. Sexuality and Disability, 18, 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005567030442

Krippendorff, K. (2003). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage Publications.

Lalumière, M. L., Blanchard, R., & Zucker, K. J. (2000). Sexual orientation and handedness in men and women: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 575–592. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.4.575

Lepage, J.-F., Lortie, M., Taschereau-Dumouchel, V., & Théoret, H. (2009). Validation of French-Canadian versions of the empathy quotient and autism spectrum quotient. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 41, 272–276. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016248

Levine, S. B. (2017). A little deeper, please [Commentary]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 639–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0947-z

Lo, Y.-C., Chen, Y.-J., Hsu, Y.-C., Tseng, W.-Y.I., & Gau, S.S.-F. (2017). Reduced tract integrity of the model for social communication is a neural substrate of social communication deficits in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58, 576–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12641

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

Parent, M. C., & Ferriter, K. P. (2018). The co-occurrence of asexuality and self-reported post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis and sexual trauma within the past 12 months among U.S. college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1277–1282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1171-1

Pexman, P. P., Rostad, K. R., McMorris, C. A., Climie, E. A., Stowkowy, J., & Glenwright, M. R. (2011). Processing of ironic language in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41, 1097–1112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1131-7

Poston, D. L., Jr., & Baumle, A. K. (2010). Patterns of asexuality in the United States. Demographic Research, 23, 509–530. https://doi.org/10.4054/demres.2010.23.18

Rothblum, E. D., Krueger, E. A., Kittle, K. R., & Meyer, I. H. (2020). Asexual and non-asexual respondents from a U.S. population-based study of sexual minorities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49, 757–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01485-0

Scherrer, K. S. (2008). Coming to an asexual identity: Negotiating identity, negotiating desire. Sexualities, 11, 621–641. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460708094269

Scherrer, K. S., & Pfeffer, C. A. (2017). None of the above: Toward identity and community-based understandings of (a)sexualities [Commentary]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 643–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0900-6

Seaman, R. L., & Cannella-Malone, H. I. (2016). Vocational skills interventions for adults with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 28, 479–494. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-016-9479-z

Sell, R. L. (1996). The Sell Assessment of Sexual Orientation: Background and scoring. Journal of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Identity, 1, 295–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03372244

Sonié, S., Kassai, B., Pirat, E., Bain, P., Robinson, J., Gomot, M., Manificat, S., & Manificat, S. (2013). The French version of the Autism-Spectrum Quotient in adolescents: A cross-cultural validation study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 1178–1183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1663-0

Stoddard, K. P., Burke, L., & King, R. (2017). Asperger syndrome in adulthood: A comprehensive guide for clinicians. W.W. Norton & Company.

Strunz, S., Schermuck, C., Ballerstein, S., Ahlers, C. J., Dziobek, I., & Roepke, S. (2017). Romantic relationships and relationship satisfaction among adults with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73, 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22319

van Anders, S. M. (2015). Beyond sexual orientation: Integrating gender/sex and diverse sexualities via sexual configurations theory. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 1177–1212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0490-8

Van Houdenhove, E., Enzlin, P., & Gijs, L. (2017). A positive approach toward asexuality: Some first steps, but still a long way to go [Commentary]. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 647–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0921-1

Van Houdenhove, E., Gijs, L., T’Sjoen, G., & Enzlin, P. (2015). Stories about asexuality: A qualitative study on asexual women. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 41, 262–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623x.2014.889053

Woodbury-Smith, M., Robinson, J., Wheelwright, S., & Baron-Cohen, S. (2005). Screening adults for Asperger syndrome using the AQ: A preliminary study of its diagnostic validity in clinical practice. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorders, 35, 331–335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-005-3300-7

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2013). Mental health and interpersonal functioning among asexual individuals. Psychology & Sexuality, 4, 136–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2013.774162

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2014). Sexual fantasy and masturbation among asexual individuals. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 23, 89–95. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2409

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2015). A validated measure of no sexual attraction: The Asexuality Identification Scale. Psychological Assessment, 27, 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038196

Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2017). Sexual fantasy and masturbation among asexual individuals: An in-depth exploration. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0870-8

Zafeiriou, D. I., Ververi, A., Dafoulis, V., Kalyva, E., & Vargiami, E. (2013). Autism spectrum disorders: The quest for genetic syndromes. American Journal of Medical Genetics, 162, 327–366. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.b.32152

Zheng, L., & Su, Y. (2018). Patterns of asexuality in China: Sexual activity, sexual and romantic attraction, and sexual desire. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47, 1265–1276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1158-y

Funding

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Grant No. 435-2012-0628).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in this study were approved and in accordance with the ethical standards of University of New Brunswick’s and University of British Columbia’s Institutional Review Boards for research involving human participants.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. We do not have any conflict of interest in submitting this work. We, the authors, acknowledge that disclosures are complete for ourselves as well as our co-authors, to the best of our knowledge.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ronis, S.T., Byers, E.S., Brotto, L.A. et al. Beyond the Label: Asexual Identity Among Individuals on the High-Functioning Autism Spectrum. Arch Sex Behav 50, 3831–3842 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-01969-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-01969-y