Abstract

Methamphetamine (meth) use is a recurring public health challenge in the U.S. In 2016, approximately 1.6 million Americans reported using meth. Meth use is associated with a number of adverse outcomes, including those associated with users’ sexual health. In particular, meth use is linked to an increased risk for sexually transmitted infections and unplanned pregnancies. While studies have examined associations between substance use of various types—including meth use, and shame and guilt—few studies have examined relationships among substance use, sexual risk behaviors, and shame and guilt. No qualitative studies, to our knowledge, have studied all three of these phenomena in a sample of meth users. The present qualitative study explored the sexual risk behaviors and associated feelings of shame and guilt in relation to meth use. It draws from anonymous letters and stories (N = 202) posted to an online discussion forum by meth users and their family members. A grounded theory analysis of these narratives identified four primary themes pertaining to meth use and sexual behaviors: (1) feeling heightened sexual arousal and stimulation on meth, (2) experiencing sexual dissatisfaction on meth, (3) responding to sexual arousal and dissatisfaction, and (4) feeling ashamed and/or guilty. Ultimately, the present findings indicate that feelings of shame and guilt may arise more from the consequences of sexual risk behaviors stemming from meth use rather than meth use itself. The emotional toll of meth-induced sexual risk behaviors, particularly shame and guilt over the loss of meaningful relationships and self-respect due to multiple sexual partners, may provide an important opportunity for interventionists.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Methamphetamine (meth) use is a persistent public health challenge in the U.S. Approximately 1.6 million Americans used meth in the past year—with nearly 775,000 people reporting meth use within the past 30 days (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2017). According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of positive urine test results for meth has increased sixfold, from 1.43% in 2013 to 8.39% in 2019 (Twillman et al., 2020). Meth is a potent stimulant that produces high levels of euphoria and can be administered through inhalation, smoking, injection, or ingestion (Dolatshahi, Farhoudian, Falahatdoost, Tavakoli, & Rezaie Dogahe, 2016). Meth use is associated with many adverse physical, mental, and social outcomes, including depression, anxiety, insomnia, aggressive behavior, domestic violence, stroke, and convulsions (Abdul-Khabir, Hall, Swanson, & Shoptaw, 2014; Iritani, Hallfors, & Bauer, 2007; McKetin et al., 2018; Springer, Peters, Shegog, White, & Kelder, 2007).

Meth acts on the central nervous system by increasing levels of dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain; it produces subjective experiences of intense pleasure and increases libido (Borders et al., 2013; Saw, Saw, Chan, Cho, & Jimba, 2018). It is also associated with the loss of inhibitory control over compulsive sexual behavior, which lowers users’ judgment during high-risk sexual activity (Dolatshahi et al., 2016). Other recreational substances like ecstasy, alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, cocaine, and opiates can also have both short-term and long-term effects on sexual function (Smith, 2007; Zaazaa, Bella, & Shamloul, 2013). Prior research has identified sexual health risks associated with meth use, including the higher likelihood of contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (Borders et al., 2013; Saw et al., 2018; Springer et al., 2007; Yen, 2004) and unplanned pregnancies (Zapata, Hillis, Marchbanks, Curtis, & Lowry, 2008). A growing body of research suggests that such adverse outcomes are linked to the unique ways that meth affects users’ sexual inclinations, behaviors, and experiences.

Studies indicate that meth use leads to increased sexual drive (Farhoudian, Dolatshahi, Falahatdoost, Tavakoli, & Farhadi, 2016; Liu, Wang, Chu, & Chen, 2013; Saw et al., 2018; Springer et al., 2007; Watt, Kimani, Skinner, & Meade, 2016; Yen, 2004), including the desire for multiple sexual partners (Dolatshahi et al., 2016; Farhoudian et al., 2016; Safi et al., 2016) and a greater willingness to engage in unprotected sex (Springer et al., 2007; Zapata et al., 2008). Several studies observing associations between meth use and increased sexual longevity also note that meth users engage in high-risk “sexual marathons” that are often accompanied by polydrug use (Dolatshahi et al., 2016; Farhoudian et al., 2016; Fisher, Reynolds, Ware, & Napper, 2011; Halkitis, Palamar, & Mukherjee, 2007; Safi et al., 2016). Furthermore, while much of the research pertaining to meth use and sexual risk has focused on opposite-sex partners, studies report similar risk factors among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (Garofalo, Mustanski, McKirnan, Herrick, & Donenberg, 2007; Halkitis, Levy, Moreira, & Ferrusi, 2014; Lion, Watt, Wechsberg, & Meade, 2017; Liu et al., 2013; Rawson et al., 2008; Semple, Zians, Strathdee, & Patterson, 2009).

To date, there is limited scholarship pertaining to the potential links among substance use, sexual risk behaviors, and shame and guilt. While there is some evidence that college-aged women (as compared to men) were more likely to regret sexual behaviors after using meth, alcohol, and other drugs (Iritani et al., 2007; Orchowski, Mastroleo, & Borsari, 2012), much of the current literature associates shame and guilt, which elicits regret, with substance use alone (Lickel, Kushlev, Savalei, Matta, & Schmader, 2014). More specifically, existing quantitative studies have reported higher shame (a maladaptive characteristic) to be positively related to substance use and higher guilt (an adaptive characteristic) inversely related to substance use (Dearing, Stuewig, & Tangney, 2005; Hequembourg & Dearing, 2013; Meehan, O’Connor, Berry, Weiss, & Acampora, 1996; O’Connor, Berry, Inaba, Weiss, & Morrison, 1994; Treeby & Bruno, 2012). Guilt proneness was also found to inversely moderate sexual risk behavior among incarcerated men exhibiting symptoms of high alcohol dependence (Stuewig, Tangney, Mashek, Forkner, & Dearing, 2009). Shame has been positively associated with compulsive sexual behaviors (CSB) among men in treatment for substance use disorders with low dispositional mindfulness; however, no relationship between shame and CSB was found for men with mean or high levels of dispositional mindfulness (Brem, Shorey, Anderson, & Stuart, 2017), which may help reduce the likelihood of relapse among addicted men with co-occurring CSB (see Shorey, Elmquist, Gawrysiak, Anderson, & Stuart, 2016).

In addition to the dearth of quantitative research focusing on substance use, sexual risk behaviors, and shame and guilt, the absence of qualitative studies involving these three phenomena leaves a substantial gap in our understanding of how substance use accompanied by sexual risk behaviors affect substance users emotionally. The known influence of meth on sexual risk behaviors makes such a study all the more critical for this subpopulation of substance users. The present qualitative study addresses the need for such research by examining the experiences of meth users, focusing on their sexual risk behaviors and feelings regarding the consequences of those behaviors. More specifically, the present study explores these previously overlooked connections by analyzing anonymous narratives posted to an online discussion forum by meth users and their family members. Research suggests data obtained from online self-help groups have the potential to provide unique insights, because the anonymity of the platform may encourage users to share their true stories and to resist dominant narratives for drug use and sexual behavior (Alexander, Obong’o, Chavan, Dillon, & Kedia, 2018; Barratt, Allen, & Lenton, 2014; Obong’o, Alexander, Chavan, Dillon, & Kedia, 2017; Schmidt, Dillon, Jackson, Pirkey, & Kedia, 2019). Analyses of interview-based qualitative studies have often ignored the ways participants’ responses are obligated to researchers’ questions and the performative aspects of the interviewing process (Gough, 2016; Schmidt et al., 2019). There is a need for qualitative research that examines sensitive health topics like meth use and risky sexual behaviors in naturalistic and anonymized settings—i.e., with peers in an online support forum, where researchers are not present (Gough, 2016; Schmidt et al., 2019).

Method

Sample

The present study examined publicly available data from the “Letters and Stories” section of KCI: The Anti-Meth Site (http://www.kci.org/meth_info/meth_letters.htm). The purpose and intent of this website is to discourage meth use, promote the message that meth addiction is a disease, and demonstrate that recovery is possible. The site administrator uploads letters and stories obtained from individuals, friends, families, and colleagues on a monthly basis. We extracted and analyzed all 202 stories published between January 2009 and December 2013. Since the letters and stories on the KCI: The Anti-Meth Site are freely accessible to the public and used for educational and support purposes, no informed consent was obtained (Eysenbach & Till, 2001; Flicker, Haans, & Skinner, 2004). The study was exempted by the Institutional Review Board at the primary author’s home institution.

Data Analysis

We reformatted all the letters and stories in the study sample as transcripts and uploaded them into a web-based software application, Dedoose, used for analyzing qualitative data (Dedoose 5.0.11, SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC, Los Angeles, CA). Grounded theory methods were used to perform initial, focused, and theoretical coding to analyze the data (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser, 2005). To ensure analytic rigor, three of the co-authors read through all of the transcripts independently and performed initial coding inductively, line by line. The three co-authors then reviewed the coding reports and agreed upon the overall fit of extracted subthemes. Upon further review of the coding reports and subthemes, the co-authors agreed to categorize them under four major themes relevant to meth use and sexual risk behaviors, visually represented in the grounded theory model (Fig. 1).

Results

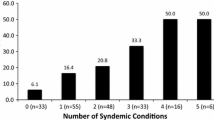

The four themes relevant to meth use and sexual risk behaviors were: (1) feeling heightened sexual arousal and stimulation on meth, (2) experiencing sexual dissatisfaction on meth, (3) responding to sexual arousal and dissatisfaction, and (4) feeling ashamed and/or guilty (Table 1).

Feeling Heightened Sexual Arousal and Stimulation on Meth

Participants’ narratives indicated that they experienced increased sexual desires and prolonged arousal while on meth; as one person narrated, “…I find that I get very sexually aroused when I am tweaking.” This meth-induced heightened arousal appeared far more intense than participants’ natural sexual desires:

We had always had great sex but this made it even better, Bob never was much on talking to me or opening up so, when he was on Meth, we had some of our best times together talking (at first).

Accompanying their enhanced arousal, some participants described dramatic increases in sensitivity to touching their genitals, which dramatically increased their physical pleasure during intercourse. Participants emphasized the extraordinariness of sex on meth, the ability to engage in sex for much longer periods, and initially, feelings of increased intimacy with their long-term partner or spouse:

We had intense sex and even more intense conversation; so intense, that talking was almost like having sex.

Participants described feeling like sex “gods,” due to their increased libido, stamina, and self-perceived sex appeal:

Yeah, I felt great at first…[I] had unbelievable sex for hours, smoked copious amounts of cigarettes, drank tons of alcohol and not get totally drunk…I was Superwoman in every way!

Unsurprisingly, participants began to rely on meth to retain newly achieved levels of sexual performance and stimulation. This reliance frustrated and exhausted some participants’ non-meth using partners:

He would love to smoke the hell out of it and have sex alllllllllllll night long. Same thing every night. It got old…Slowly I would leave him to himself…

Conversely, some participants’ non-meth-using partners became dissatisfied, due to meth’s inhibitive effects on sexual performance:

I was attracted to him but now it is waning. He has trouble keeping an erection. Sex life is fizzling…I know it is only going to get worse as he will of course DEPEND on it more for sexual satisfaction.

Experiencing Sexual Dissatisfaction on Meth

Likewise, participants also experienced sexual dissatisfaction: Increased arousal and stimulation came at the expense of sexual gratification. As one participant explained:

There was no sense of satisfaction or relief. Just the powerful urge to begin again.

As participants relied increasingly on pornography and masturbation in response to their heightened sexual drive, their intimacy with long-term partners or spouses was negatively impacted:

My mind gets so twisted about sexual fantasies that my beautiful wife of 10 years doesn’t even exist during intercourse. …I think about sex constantly. And sex is a good thing. Unfortunately for me dope has made it a constant demon in my life.

Heightened arousal appeared to create an insatiable desire for longer and more varied forms of sexual stimulation. Furthermore, the fleetingness of sexual gratification at orgasm, as well as the difficulty some male participants experienced achieving an erection, appeared to reinforce the desire for further sexual stimulation. Consequently, heightened arousal appeared to generate a cycle of stimulation and frustration resistant to participants’ preexisting means for achieving sexual gratification. This led some participants to view themselves as both a drug addict and a sex addict:

My addiction to meth is a steppingstone to my sexual addiction. I’m sure we’ve all had some wild sexual experiences on the shit, but that’s all I think about from the moment I take that first hit, until I realize 30 h later that masturbating is all I get, not the threesomes on the porno, or swapping wives with my ‘friend.’

Other participants reported exhaustion from weekend meth and sex binges, which left them too tired to engage in sex during the week, contradicting their self-perceived “god-like” sexual prowess while using meth. One participant stated, for example:

We don’t have sex during the week when we are not high, we don’t have the stamina to do anything, or the motivation to push ourselves further.

Participants’ need for more varied forms and sources of sexual stimulation—to address their heightened arousal and sexual dysfunctions—appeared to engender dissatisfaction in sex with current partners or with preexisting sexual habits.

Responding to Sexual Arousal and Dissatisfaction

Participants appeared to respond to both heightened arousal and sexual dissatisfaction by extending the duration of sexual events with their main partner, inviting new partners to join in their sexual encounters with their main partner, and/or separately engaging in sex with new partners with or without their main partner’s consent or knowledge.

Engaging in sex with new partners, however, emerged as the most common response to heightened arousal and sexual dysfunctions among participants. Furthermore, sex with new partners emerged as a dominant response among participants for dealing with heightened arousal and sexual dysfunctions:

That was late afternoon next thing you know we were up all night, we made love over and over then he was asking me if I wanted to invite his friend in. I agreed…

He has always been very sexual and always kept our personal lives just between us. Of course, we had our sexual fantasies. However, the last 4-6 weeks we were together he involved some of our friends or at least tried too. We both were excited, but I was a little apprehensive, but drunk.

Participants varied in how they managed their responses. For some participants, responses appeared to be premeditated and carefully maintained:

I started having multiple affairs, completely lying to each girl that I was completely faithful to that one.

For other participants, responses appeared to be spontaneous and out of character:

One night in a meth-wind I cheated on my adoring husband. Prior to meth we were inseparable.

A common description across participant accounts, however, was the irresistible urge to engage in sex with multiple partners, whether participants portrayed their sexual activity as a deliberate response or as a lack of control driven by a powerful addiction to both sex and meth:

I lied, cheated and abused the person I loved the most and had no control whatsoever over my actions and at the same time was blinded by its evil.

Many participants attempted to maintain their marriages or long-term relationships while engaging in multiple “affairs.” Some participants’ loved ones believed they had lost interest in sex, only to discover their interest had migrated to other partners, including strangers:

We have had sex twice in 2 years. I just learned he has been screwing various women while traveling about the country for his job. He also would hook up with women he met on the internet.

Consequently, spouses and long-term partners varied in their awareness of participants’ increased sexual activities and sexual dissatisfaction or knowledge that such feelings and behaviors were tied to meth use. While some participants progressed through intense sexual experiences with their long-term partners, who appeared well aware of meth’s role, to sex with new partners, other participants maintained secrecy as a further means of hiding their meth addiction.

For those who were not in committed relationships, heightened arousal also led to sex with multiple partners. As with participants in committed relationships, unattached participants seemed dissatisfied in sex with a regular partner due to intense arousal and the consequent need for longer and more varied sexual stimulation—all seemingly in pursuit of sexual gratification that could be achieved either fleetingly or not at all. As one participant shared:

Me and my friends used to make speedballs, it was so intense. I used to have sex with all these guys, guys I would’ve never slept with sober.

Few participants seemed concerned about the consequences of engaging in unprotected sex, even when it occurred with acquaintances and strangers. As one narrative suggested, despite acknowledging the potential health risks, some participants were still willing to forgo using condoms:

Unsafe sex and meth go hand in hand. I am afraid that I may have contracted HIV, and intend to be tested. Many gay men will prefer to have unprotected sex, and under the influence of drugs, you sometimes allow it to happen even though you know better.

Feeling Ashamed and/or Guilty

While providing an outlet for heightened sexual arousal and a means to respond to dissatisfaction with a current partner or manner of sexual activity, sex with multiple partners led participants to more profound dissatisfaction with their lives and themselves. In particular, participants experienced guilt over ruining their meaningful intimate relationships. Sex outside the marriage or long-term relationship was common among participants; some reported deep remorse over the pain they caused loved ones:

I ripped apart the people I loved. I lied. I cheated. Lost the one man who truly loved me to this dope…

…and to this day my worst guilt of all: a cheater. I had never had an affair with anyone or on anyone ever that is what broke up my own family, but this too I did.

Also salient was participants’ guilt over their role in domestic violence, citing meth-induced paranoia and “cheating” as instigators. One participant and her partner both used meth, which seemed to create a particularly vicious cycle of sex and violence, including potential self-harm:

My husband and I was like most of you. We fought and have never put our hands on each other in 10 years ‘til we smoked the devil. Sex was all he thought about and the paranoia for me and the “other” woman he was cheating on me [which] caused me to put a loaded handgun to my head.

Another participant felt heartbroken over a physical fight with her mother, which resulted in the participants’ arrest:

I [ended] up spending overnight in jail a couple months later for a physical and completely heartbreaking altercation with my mother.

Sex with multiple partners appeared to lead to shame over loss of self-respect and self-worth:

I would end up in a hotel room having sex with my friend and his friends, now this is not like me at all. I have always had respect for myself and have NEVER engaged in this sort of activity. I had lost my self-respect by letting myself become a sexual object.

Still other participants were consumed with guilt over consequences accumulated over the course of their addiction:

I went on a 10 year run…In those 10 years I f**ked over, cheated, lied, hurt, stole, ignored responsibility, abandoned, lost my dignity, lost the trust of others, scammed, schemed, lost my wife, my boys, my home, my job, and my god, I ended up in jail not once but twice.

Other participants were consumed with shame over consequences of their addiction, focusing their concerns on what they thought of themselves and what they feared others would think of them:

My body, my personality, and my relationships all changed. I was no longer the sunny outgoing and faithful wife everyone knew…

I turned into everything parents warn they’re children about. Sleeping with people to have a place to stay, staying up until it couldn’t keep me up, losing all my friends, except the new ones who just loved me.

Still other participants evidenced a mix of shame and guilt in their recollections, referring to damage caused to their self-image and the pain it caused loved ones:

I felt like crap after I slept with them. My life was falling apart, and it was killing my mother.

Discussion

This study explored experiences of sexual risk behaviors arising from meth use and participants’ perceptions regarding those behaviors, particularly their feelings of shame and guilt. The present findings suggest that meth use leads to heightened arousal and stimulation that may result in sexual risk behaviors, particularly sex with multiple partners, including acquaintances and strangers. Some participants first experimented with their spouse or long-term partner, became dissatisfied and/or experienced sexual dysfunction, and then turned to sex with multiple partners. Intense arousal accompanied by fleeting or no sexual gratification appeared to drive participants to seek more stimulation in the form of additional partners, varied sexual experiences (e.g., sex with multiple partners at once, sex with strangers, and same-sex partners), and longer sexual events. These risk behaviors, in turn, led to guilt, as evidenced by participants’ remorse over lost relationships and pain caused to others, as well as shame, experienced as damaged self-worth. Some participants reflected on accumulated shame and guilt built up over years of meth use, while others lamented how quickly they lost everything. Participants described their feelings of shame and guilt as consequences of their risky sexual behaviors, which they attributed to their meth use. Our participants’ attribution of shame and guilt to sexual behavior induced by substance use, as opposed to substance use alone, distinguishes our results from prior studies linking low-guilt and/or high-shame proneness to substance use (Bradshaw, 2005; Dearing et al., 2005; Fossum & Mason, 1989; Meehan et al., 1996; O’Connor et al., 1994; Tangney & Dearing, 2003; Tangney, Mashek, & Stuewig, 2007a, Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek, 2007b; Wiechelt, 2007) (Fig. 1).

Despite ongoing sexual contact with acquaintances and strangers, as well as occasional concurrent exposure to multiple partners, participants’ enjoyment of heightened stimulation and response to sexual dissatisfaction and dysfunction (i.e., by seeking greater stimulation) may have inhibited safe sexual practices. Participants also described frustration with erectile dysfunction, mentioning Viagra as one response. Furthermore, while only a small number of participants in this study mentioned condom use, prior studies have observed inhibited use of condoms among heterosexual men and women and gay men (Corsi & Booth, 2008; Halkitis, Mukherjee, & Palamar, 2009; Hittner, 2016; Rawstorne, Digiusto, Worth, & Zablotska, 2007). Additionally, although participants were aware of the connection between their meth use and risky sexual behaviors, most did not explicitly state or infer awareness of health risks associated with those behaviors, which indicates either a lack of sexual health risk awareness, a higher prioritization of other severe consequences of their actions (e.g., loss of an important relationship and/or self-respect), or both. Feelings of shame and guilt arising from non-health-related consequences may eclipse participants’ concerns regarding their health status and that of their sexual partners.

Participants’ experiences of shame and guilt appeared to derive from their thoughts and feelings regarding the consequences of their sexual risk behaviors. Given participants’ awareness that their sexual risk behaviors had stemmed from their meth use, future quantitative studies should consider the potential roles of sexual risk behaviors as moderators or mediators of the relationship between meth use and shame and guilt. Interestingly, in the few instances participants implicated meth use in their feelings of shame and guilt, it was to blame meth use for the risky sexual behaviors that led to the consequences over which they felt ashamed and guilty. The emotional toll of the consequences stemming from meth-induced sexual risk behaviors, particularly shame and guilt associated with loss of meaningful relationships and self-respect over multiple-partner sex history, may provide an opportunity for meth use recovery intervention, as indicated by our results and prior research (Potter-Efron, 2002; Wiechelt, 2007).While research is limited in this area, other studies have shown that women and some men regretted their participation in sexual activities while under the influence of meth (Bourne, Reid, Hickson, Torres-Rueda, & Weatherburn, 2015; Iritani et al., 2007), further supporting others’ findings that shame and guilt are important factors in substance addiction and addiction recovery (Dearing et al., 2005; Gueta, 2013; Potter-Efron, 2002).

The findings of this study are also consistent with self-conscious emotions theory (Lewis, 1971), which posits that people’s feelings of shame focus attention on themselves and others’ opinions of them, while feelings of guilt focus attention on their behaviors and the associated consequences—i.e., damaged relationships or harm caused to others (Lewis, 1971; Tangney et al., 2007b). Among participants in the present study, shame appeared to derive from the supplanting of a once proud identity with that of feeling like a lesser person (e.g., a liar or cheater), while guilt appeared to derive from circumspection about behaviors and empathy for those hurt. Many participants appeared to experience a mixture of shame and guilt.

Individuals experiencing shame may feel powerless, whereas individuals experiencing guilt may feel motivated to change their behaviors as a means to seek forgiveness or otherwise cease actions they deem unacceptable by moral standards (Tangney, Stuewig, & Hafez, 2011, 2014; Tangney et al., 2007a, 2007b). To break the shame/avoidance cycle of substance abuse (Wiechelt, 2007), prior research advocates for interventions designed to convert shame into shame-free guilt (Tangney et al., 2011; Wiechelt, 2007) or to convert avoidance of assessing one’s behaviors into approaches to addressing one’s behaviors. Guilt, specifically shame-free guilt, is associated with adaptive behaviors (Lickel et al., 2014; Tangney et al., 2011), while shame is associated with avoidance behaviors—i.e., minimization, anger, and blaming others (Lickel et al., 2014; Nathanson, 1994; Tangney et al., 2007a, 2007b).

Programs or services intent on changing criminal and risky behaviors through shame and guilt intervention should avoid inducing shame that focuses on negative consequences of behaviors affecting others (i.e., family, friends, community), foster empathy for those adversely affected by the behaviors, encourage feelings of behavior-focused guilt while directing participants away from self-loathing, and actively involve clients in developing constructive solutions to the damage caused by their behaviors (Tangney et al., 2011). Importantly, a person’s sense of self, which can be damaged by shame, must be improved in order to impact recovery (Hill & Leeming, 2014). While interventions designed to address shame and guilt vary in approach (see, for example, Balcom, Call, & Pearlman, 2000; Braithwaite, 1989; Brown, Hernandez, & Villarreal, 2011; Gilbert, 2010; Greenberg, 2011; Loeffler, Prelog, Prabha Unnithan, & Pogrebin, 2010; Milestone, 1993), their common goal is to mitigate shame and its inhibiting effect on behavior change. To date, there exists little empirical validation of such interventions (Tangney et al., 2011; Wiechelt, 2007) and few interventions have been developed specifically to address shame and guilt in the context of substance abuse recovery (Bradshaw, 2005; Cook, 1991; Fossum & Mason, 1989; Potter-Efron, 2002) or alcohol abuse recovery (see Garland, Schwarz, Kelly, Whitt, & Howard, 2012). However, some promise for reducing shame among substance users with co-occurring CSB has been found in studies of the moderating role of dispositional mindfulness in the associations between CSB and shame (Brem et al., 2017; Shorey et al., 2016). Further research on the roles of shame and guilt in substance abuse and substance abuse recovery is needed to inform interventions specific to meth use and co-occurring sexual risk behaviors.

Limitations

As this study demonstrated, online platforms are an innovative approach for collecting qualitative data on meth use and high-risk sexual behavior, allowing people to anonymously and freely share their histories of meth use and sexual behavior without fear of legal ramifications or stigma. This approach does have, however, some notable limitations. The online support group does not provide any information regarding participant characteristics, i.e., race, gender, socioeconomic status, or country of residence. Limited information from Alexa (http://www.alexa.com) reported that most of the site visitors lived in the U.S. or Australia (73.2% and 12.7%, respectively), countries where meth is commonly used (Degenhardt & Hall, 2012). Since the U.S. and Australia are Western countries with majority Caucasian populations, letters published to the website may represent the experiences of predominantly Western Caucasian users, limiting the transferability of the results. The absence of participant characteristics prevented the assignment of case classification attributes, which in turn prevented subgroup comparisons between or across themes. The use of secondary data as opposed to primary data collection, e.g., an interview conducted using an interview guide, prevented probing on questions of interest, consistent collection of data on topics of interest, theoretical sampling on emergent themes, and subsequent member checking. The lack of in-person interviewing prevented us from using probing questions to further investigate participants’ feelings of shame, guilt, or dissatisfaction.

Alternatively, the absence of an interviewer might have helped participants feel less worried about being judged when expressing their shame and guilt. Researchers have also observed difficulties identifying clients experiencing shame and guilt in clinical environments, as shame may be masked by anger, and guilt may be obscured by other symptoms (Tangney, Wagner, Fletcher, & Gramzow, 1992). The use of writing as a reflective exercise and the resultant narratives shared provide data challenging to capture even in counseling, aiding the emergence of these complex constructs and their nuanced properties in our analyses. Furthermore, we used the context—or surrounding data—from which participant quotes were drawn to avoid guessing at participants’ feelings, which helped address the limitation posed by our lack of opportunity to ask participants how they felt.

We do not know if the purveyors of KCI: The Anti-Meth Site rejected any letters, particularly letters from site users with little or no intention of engaging in recovery. Therefore, participants’ accounts of meth use, sexual risk behavior, and feelings of shame and guilt cannot be attributed to either recovery-seekers or non-recovery-seekers, or both, but only to those website users whose letters were published. Furthermore, the website is dedicated to promoting meth addiction recovery, which may have influenced some participants to write what they believed other users would find acceptable or even laudable. While we cannot determine the veracity or authenticity of the online narratives about meth use and risky sexual behavior, most online narratives describe sexual behavior consistent with our observations (Dolatshahi et al., 2016; Liu & Chai, 2020; Mburu et al., 2017; Reback, Larkins, & Shoptaw, 2004; Safi et al., 2016).

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this study is the first to identify shame and guilt regarding the consequences of sexual risk behaviors—in response to heightened sexual arousal and stimulation on meth—as an opportunity to intervene in both meth use and sexual health risk behavior. With few exceptions, participants’ main concerns, and most profound sources of shame and guilt, were non-health-related (e.g., loss of a relationship or self-respect). Addressing shame and guilt among meth users, therefore, may be useful in motivating sexual risk behavior change and substance abuse cessation, where direct appeals to health may have been unsuccessful. This study also identified a lack of sexual health risk concern, either due to lack of health risk awareness or the aforementioned shame and guilt over significant personal losses, or both. Further research is needed to understand the roles of shame and guilt in meth use and meth use recovery as well as the potential of shame and guilt interventions to reduce or prevent sexual health risk behaviors among those in meth use recovery.

References

Abdul-Khabir, W., Hall, T., Swanson, A.-N., & Shoptaw, S. (2014). Intimate partner violence and reproductive health among methamphetamine-using women in Los Angeles: A qualitative pilot study. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 46(4), 310–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2014.934978.

Alexander, A. C., Obong’o, C. O., Chavan, P. P., Dillon, P. J., & Kedia, S. K. (2018). Addicted to the ‘life of methamphetamine’: Perceived barriers to sustained methamphetamine recovery. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 25(3), 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2017.1282423.

Balcom, D., Call, E., & Pearlman, D. N. (2000). Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing treatment of internalized shame. Traumatology, 6(2), 69–83.

Barratt, M. J., Allen, M., & Lenton, S. (2014). “PMA sounds fun”: Negotiating drug discourses online. Substance Use and Misuse, 49(8), 987–998.

Borders, T. F., Stewart, K. E., Wright, P. B., Leukefeld, C., Falck, R. S., Carlson, R. G., & Booth, B. M. (2013). Risky sex in rural America: Longitudinal changes in a community-based cohort of methamphetamine and cocaine users. American Journal on Addictions, 22(6), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12028.x.

Bourne, A., Reid, D., Hickson, F., Torres-Rueda, S., & Weatherburn, P. (2015). Illicit drug use in sexual settings (‘chemsex’) and HIV/STI transmission risk behaviour among gay men in South London: Findings from a qualitative study. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 91(8), 564–568. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2015-052052.

Bradshaw, J. (2005). Healing the shame that binds you. Deerfield Beach, FL: Health Communications Inc.

Braithwaite, J. (1989). Crime, shame and reintegration. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Brem, M. J., Shorey, R. C., Anderson, S., & Stuart, G. L. (2017). Dispositional mindfulness, shame, and compulsive sexual behaviors among men in residential treatment for substance use disorders. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1552–1558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0723-0.

Brown, B., Hernandez, V. R., & Villarreal, Y. (2011). Connections: A 12-session psychoeducational shame resilience curriculum. In R. L. Dearing & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Shame in the therapy hour (Vol. 2011, pp. 355–371). Worcester, MA: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12326-015.

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Newcastle upon Tyne, England: Sage.

Cook, D. R. (1991). Shame, attachment, and addictions: Implications for family therapists. Contemporary Family Therapy, 13(5), 405–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00890495.

Corsi, K. F., & Booth, R. E. (2008). HIV sex risk behaviors among heterosexual methamphetamine users: Literature review from 2000 to present. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 1(3), 292–296.

Dearing, R. L., Stuewig, J., & Tangney, J. P. (2005). On the importance of distinguishing shame from guilt: Relations to problematic alcohol and drug use. Addictive Behaviors, 30(7), 1392–1404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.002.

Degenhardt, L., & Hall, W. (2012). Extent of illicit drug use and dependence, and their contribution to the global burden of disease. The Lancet, 379(9810), 55–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61138-0.

Dolatshahi, B., Farhoudian, A., Falahatdoost, M., Tavakoli, M., & Rezaie Dogahe, E. (2016). A qualitative study of the relationship between methamphetamine abuse and sexual dysfunction in male substance abusers. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors and Addiction, 5. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijhrba.29640.

Eysenbach, G., & Till, J. E. (2001). Ethical issues in qualitative research on internet communities. British Medical Journal, 323(7321), 1103–1105.

Farhoudian, A., Dolatshahi, B., Falahatdoost, M., Tavakoli, M., & Farhadi, M. H. (2016). A qualitative study on methamphetamine-related sexual high-risk behaviors in an Iranian context. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.5812/ijhrba.31910.

Fisher, D. G., Reynolds, G. L., Ware, M. R., & Napper, L. E. (2011). Methamphetamine and Viagra use: Relationship to sexual risk behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(2), 273–279. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9495-5.

Flicker, S., Haans, D., & Skinner, H. (2004). Ethical dilemmas in research on internet communities. Qualitative Health Research, 14(1), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303259842.

Fossum, M. A., & Mason, M. J. (1989). Facing shame: Families in recovery. New York: WW Norton & Company.

Garland, E. L., Schwarz, N. R., Kelly, A., Whitt, A., & Howard, M. O. (2012). Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for alcohol dependence: Therapeutic mechanisms and intervention acceptability. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 12(3), 242–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/1533256X.2012.702638.

Garofalo, R., Mustanski, B. S., McKirnan, D. J., Herrick, A., & Donenberg, G. R. (2007). Methamphetamine and young men who have sex with men: Patterns, correlates and consequences of use. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 161(6), 591–596. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.6.591.

Gilbert, P. (2010). Compassion focused therapy: Distinctive features. London: Routledge.

Glaser, B. G. (2005). The grounded theory perspective III: Theoretical coding. London: Sociology Press.

Gough, B. (2016). Men’s depression talk online: A qualitative analysis of accountability and authenticity in help-seeking and support formulations. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 17(2), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039456.

Greenberg, L. S. (2011). Theories of psychotherapy: Emotion-focused therapy. Worcester, MA: American Psychological Association.

Gueta, K. (2013). Self-forgiveness in the recovery of Israeli drug-addicted mothers: A qualitative exploration. Journal of Drug Issues, 43(4), 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042613491097.

Halkitis, P. N., Levy, M. D., Moreira, A. D., & Ferrusi, C. N. (2014). Crystal methamphetamine use and HIV transmission among gay and bisexual men. Current Addiction Reports, 1(3), 206–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-014-0023-x.

Halkitis, P. N., Mukherjee, P. P., & Palamar, J. J. (2009). Longitudinal modeling of methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors in gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 13(4), 783–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9432-y.

Halkitis, P. N., Palamar, J. J., & Mukherjee, P. P. (2007). Poly-club-drug use among gay and bisexual men: A longitudinal analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 89(2), 153–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.028.

Hequembourg, A. L., & Dearing, R. L. (2013). Exploring shame, guilt, and risky substance use among sexual minority men and women. Journal of Homosexuality, 60(4), 615–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2013.760365.

Hill, J. V., & Leeming, D. (2014). Reconstructing ‘the alcoholic’: Recovering from alcohol addiction and the stigma this entails. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 12(6), 759–771.

Hittner, J. B. (2016). Meta-analysis of the association between methamphetamine use and high-risk sexual behavior among heterosexuals. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000162.

Iritani, B. J., Hallfors, D. D., & Bauer, D. J. (2007). Crystal methamphetamine use among young adults in the USA. Addiction, 102(7), 1102–1113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01847.x.

Lewis, H. B. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

Lickel, B., Kushlev, K., Savalei, V., Matta, S., & Schmader, T. (2014). Shame and the motivation to change the self. Emotion, 14(6), 1049–1061. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038235.

Lion, R. R., Watt, M. H., Wechsberg, W. M., & Meade, C. S. (2017). Gender and sex trading among active methamphetamine users in Cape Town, South Africa. Substance Use and Misuse, 52(6), 773–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826084.2016.1264964.

Liu, L., & Chai, X. (2020). Pleasure and risk: A qualitative study of sexual behaviors among Chinese methamphetamine users. Journal of Sex Research, 57, 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1493083.

Liu, D., Wang, Z., Chu, T., & Chen, S. (2013). Gender difference in the characteristics of and high-risk behaviours among non-injecting heterosexual methamphetamine users in Qingdao, Shandong province, China. BMC Public Health, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-30.

Loeffler, C. H., Prelog, A. J., Prabha Unnithan, N., & Pogrebin, M. R. (2010). Evaluating shame transformation in group treatment of domestic violence offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 54(4), 517–536.

Mburu, G., Ngin, C., Tuot, S., Chhoun, P., Pal, K., & Yi, S. (2017). Patterns of HIV testing, drug use, and sexual behaviors in people who use drugs: Findings from a community-based outreach program in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13722-017-0094-9.

McKetin, R., Lubman, D. I., Baker, A., Dawe, S., Ross, J., Mattick, R. P., & Degenhardt, L. (2018). The relationship between methamphetamine use and heterosexual behaviour: Evidence from a prospective longitudinal study: Methamphetamine use and sexual behaviour. Addiction, 113(7), 1276–1285. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14181.

Meehan, W., O’Connor, L. E., Berry, J. W., Weiss, J., & Acampora, A. (1996). Guilt, shame, and depression in clients in recovery from addiction. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 28(2), 125–134.

Milestone, S. F. (1993). Implications of affect theory for the practice of cognitive therapy. Psychiatric Annals, 23(10), 577–583.

Nathanson, D. L. (1994). Shame and pride: Affect, sex, and the birth of the self. New York: WW Norton & Company.

O’Connor, L. E., Berry, J. W., Inaba, D., Weiss, J., & Morrison, A. (1994). Shame, guilt, and depression in men and women in recovery from addiction. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 11(6), 503–510.

Obong’o, C. O., Alexander, A. C., Chavan, P. P., Dillon, P. J., & Kedia, S. K. (2017). Choosing to live or die: Online narratives of recovering from methamphetamine abuse. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 49(1), 52–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2016.1262085.

Orchowski, L. M., Mastroleo, N. R., & Borsari, B. (2012). Correlates of alcohol-related regretted sex among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(4), 782–790. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027840.

Potter-Efron, R. (2002). Shame, guilt, and alcoholism: Treatment issues in clinical practice (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Haworth Press.

Rawson, R. A., Gonzales, R., Pearce, V., Ang, A., Marinelli-Casey, P., & Brummer, J. (2008). Methamphetamine dependence and human immunodeficiency virus risk behavior. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 35(3), 279–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2007.11.003.

Rawstorne, P., Digiusto, E., Worth, H., & Zablotska, I. (2007). Associations between crystal methamphetamine use and potentially unsafe sexual activity among gay men in Australia. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36(5), 646–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9206-z.

Reback, C. J., Larkins, S., & Shoptaw, S. (2004). Changes in the meaning of sexual risk behaviors among gay and bisexual male methamphetamine abusers before and after drug treatment. AIDS and Behavior, 8(1), 87–98.

Safi, M. H., Younesi, S. J., Dadkhah, A., Farhoudian, A., Fallahi-Khoshknab, M., & Azkhosh, M. (2016). The role of sexual behaviors in the relapse process in Iranian methamphetamine users: A qualitative study. Addiction & Health, 8(4), 242–251.

Saw, Y. M., Saw, T. N., Chan, N., Cho, S. M., & Jimba, M. (2018). Gender-specific differences in high-risk sexual behaviors among methamphetamine users in Myanmar-China border city, Muse, Myanmar: Who is at risk? BMC Public Health, 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5113-6.

Schmidt, M., Dillon, P. J., Jackson, B. M., Pirkey, P., & Kedia, S. K. (2019). “Gave me a line of ice and I got hooked”: Exploring narratives of initiating methamphetamine use. Public Health Nursing, 36(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12568.

Semple, S. J., Zians, J., Strathdee, S. A., & Patterson, T. L. (2009). Sexual marathons and methamphetamine use among HIV-positive men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(4), 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9292-y.

Shorey, R. C., Elmquist, J., Gawrysiak, M. J., Anderson, S., & Stuart, G. L. (2016). The relationship between mindfulness and compulsive sexual behavior in a sample of men in treatment for substance use disorders. Mindfulness, 7(4), 866–873. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0525-9.

Smith, S. (2007). Drugs that cause sexual dysfunction. Psychiatry, 6(3), 111–114.

Springer, A. E., Peters, R. J., Shegog, R., White, D. L., & Kelder, S. H. (2007). Methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors in US high school students: Findings from a national risk behavior survey. Prevention Science, 8(2), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-007-0065-6.

Stuewig, J., Tangney, J. P., Mashek, D., Forkner, P., & Dearing, R. (2009). The moral emotions, alcohol dependence, and HIV risk behavior in an incarcerated sample. Substance Use and Misuse, 44(4), 449–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080802421274.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2017). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2016 National Survey on Drug Use and Health | CBHSQ. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/key-substance-use-and-mental-health-indicators-united-states-results-2016-national-survey.

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2003). Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford Press.

Tangney, J. P., Mashek, D., & Stuewig, J. (2007a). Working at the social–clinical–community–criminology interface: The George Mason University Inmate Study. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(1), 1–21.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Hafez, L. (2011). Shame, guilt, and remorse: Implications for offender populations. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 22(5), 706–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2011.617541.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Martinez, A. G. (2014). Two faces of shame: the roles of shame and guilt in predicting recidivism. Psychological Science, 25(3), 799–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613508790.

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007b). Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 345–372. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145.

Tangney, J. P., Wagner, P., Fletcher, C., & Gramzow, R. (1992). Shamed into anger? The relations of shame and guilt to anger and self-reported aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(4), 669–675.

Treeby, M., & Bruno, R. (2012). Shame and guilt-proneness: Divergent implications for problematic alcohol use and drinking to cope with anxiety and depression symptomatology. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(5), 613–617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.05.011.

Twillman, R. K., Dawson, E., LaRue, L., Guevara, M. G., Whitley, P., & Huskey, A. (2020). Evaluation of trends of near-real-time urine drug test results for methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, and fentanyl. JAMA Network Open, 3(1), e1918514. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18514.

Watt, M. H., Kimani, S. M., Skinner, D., & Meade, C. S. (2016). “Nothing is free”: A qualitative study of sex trading among methamphetamine users in Cape Town, South Africa. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(4), 923–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0418-8.

Wiechelt, S. A. (2007). The specter of shame in substance misuse. Substance Use and Misuse, 42(2–3), 399–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/10826080601142196.

Yen, C.-F. (2004). Relationship between methamphetamine use and risky sexual behavior in adolescents. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences, 20(4), 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1607-551X(09)70101-9.

Zaazaa, A., Bella, A. J., & Shamloul, R. (2013). Drug addiction and sexual dysfunction. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America, 42(3), 585–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2013.06.003.

Zapata, L. B., Hillis, S. D., Marchbanks, P. A., Curtis, K. M., & Lowry, R. (2008). Methamphetamine use is independently associated with recent risky sexual behaviors and adolescent pregnancy. Journal of School Health, 78(12), 641–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00360.x.

Funding

This study was not funded by any external funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ahuja, N., Schmidt, M., Dillon, P.J. et al. Online Narratives of Methamphetamine Use and Risky Sexual Behavior: Can Shame-Free Guilt Aid in Recovery?. Arch Sex Behav 50, 323–332 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01777-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-020-01777-w